Abstract

Melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH), a cyclic 19-amino-acid peptide, is synthesized exclusively by neurons in the lateral hypothalamic (LH) area. It is involved in a number of brain functions and recently has raised interest because of its role in energy homeostasis. MCH axons and receptors are found throughout the brain. Previous reports set the foundation for understanding the cellular actions of MCH by using non-neuronal cells transfected with the MCH receptor gene; these cells exhibited an increase in cytoplasmic calcium in response to MCH, suggesting an excitatory action for the peptide. In the study presented here, we have used whole-cell recording in 117 neurons from LH cultures and brain slices to examine the actions of MCH. MCH decreased the amplitude of voltage-dependent calcium currents in almost all tested neurons. The inhibition desensitized rapidly (18 s to half maximum at 100 nm concentration) and was dose-dependent (IC50 = 7.8 nm) when activated with a pulse from –80 mV to 0 mV. A priori activation of G-proteins with GTPγS completely eliminated the MCH-induced effect at low MCH concentrations and reduced the MCH-induced effect at high MCH concentrations. Inhibition of G-proteins with pertussis toxin (PTX) blocked the MCH-induced inhibitory effect at high MCH concentrations. Pre-pulse depolarization resulted in an attenuation of the MCH-induced inhibition of calcium currents in most neurons. These data suggest that MCH exerts an inhibitory effect on calcium currents via PTX-sensitive G-protein pathways, probably the Gi/Go pathway, in LH neurons. L-, N- and P/Q-type calcium channels were identified in LH neurons, with L- and N-type channels accounting for most of the voltage-activated current (about 40 % each); MCH attenuated each of the three types (mean 50 % depression), with the greatest inhibition found for N-type currents. In contrast to previous data on non-neuronal cells showing an MHC-evoked increase in calcium, our data suggest that the reverse occurs in LH neurons. The attenuation of calcium currents is consistent with an inhibitory action for the peptide in neurons.

The lateral hypothalamus (LH) is an important area in physiological homeostasis. In addition to its role in functions such as sensorimotor integration, sleep and arousal, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that the LH plays a crucial part in the complex network involved in the regulation of energy homeostasis (Sawchenko, 1998). One of the few neuropeptides synthesized only in the LH area is melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH), a cyclic 19-amino-acid peptide that has recently generated considerable attention due to its robust effects on feeding. Intracerebral administration of MCH has been reported to evoke feeding in rodents (Qu et al. 1996; Rossi et al. 1997). In transgenic mice that overexpress MCH in the LH area, obesity and resistance to insulin have been observed (Ludwig et al. 2001). Conversely, MCH-deficient mice have reduced body weight and are lean due to decreased feeding and an enhanced metabolism (Shimada et al. 1998). MCH mRNA expression is increased by starvation, and c-fos in MCH neurons is upregulated by starvation (Qu et al. 1996) and by leptin administration (Huang & Viale, 1999). MCH has been reported to modify memory retention (Monzon et al. 1999). MCH expression levels show sensitivity to oestrogenic steroids (Viale et al. 1999) and MCH stimulates the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone and gonadotropins in the female rat (Chiocchio et al. 2001), indicating an involvement in the reproductive axis.

MCH-immunoreactive axons have a remarkably wide distribution throughout the CNS. In addition to a high density of fibres and boutons in the LH, it has been shown that MCH-containing fibres project to the isocortex, olfactory regions, hippocampus, amygdala, septum, basal ganglia, thalamus, brainstem, cerebellum and spinal cord (Bittencourt et al. 1992). The MCH receptor, SLC-1, also has a widespread pattern of expression, correlating with the distribution of MCH axons throughout the CNS (Lembo et al. 1999; Kilduff & De Lecea, 2001; Saito et al. 2001).

Previous work with the MCH receptor expressed in non-neuronal cells transfected with the receptor gene, SLC-1, has led to the view that MCH increases cellular calcium levels, as detected with digital imaging, and increases potassium currents (Bächner et al. 1999). We have shown that in neurons, MCH exerts an inhibitory modulation of synaptic activity (Gao & van den Pol, 2001), and in contrast to work on non-neuronal cells, our preliminary data suggested that inhibition of voltage-dependent calcium currents underlies the MCH-induced actions in neurons. Voltage-dependent calcium channels are important participants in neuronal function. Voltage-dependent N- and P/Q-type calcium channels play a substantial role in action-potential-dependent transmitter release (Wheeler et al. 1994; Catterall, 1998), and L-type calcium channels may modulate the expression of transporters and channels (Carafoli et al. 1999). Peptides that modulate calcium channels are therefore in a critical position to regulate a number of dimensions of neuronal activity and function.

Despite its important role in the modulation of many neuronal systems within the brain, as revealed at both the molecular and whole-animal level, little is known about how MCH works at the cellular level. In the study presented here, we have examined the cellular actions of MCH in LH cultures and slices. We have characterized the inhibitory mechanism and signal transduction of MCH on specific voltage-dependent calcium currents with whole-cell patch recording.

METHODS

Cell culture

Hypothalamic neurone cultures were prepared from rat embryos as described in previous papers (Gao et al. 1998). Use of animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were given an overdose of Nembutal (100 mg kg−1), embryos were collected, and then the pregnant rats were given a second lethal dose of Nembutal (150 mg kg−1). Lateral hypothalami were dissected out of the brains of embryonic day (E)15-E18 embryos and cut into small pieces (≤ 1 mm3). The tissue was digested at 37 °C for 15 min in an enzyme solution (containing 20 units ml−1 papain, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1.5 mm CaCl2, and 0.2 mg ml−1l-cysteine) and triturated mechanically in culture medium to obtain dissociated cells. After washing with culture medium (containing 10 % foetal bovine serum), LH cells were plated in 35 mm culture dishes at a density of 200 000-300 000 cells per dish and maintained at 37 °C in 5 % CO2. Serum-containing medium was replaced by serum-free medium 1-2 h after plating. The serum-free culture medium contained neurobasal medium (Gibco), 5 % B27 supplement (Gibco), 0.5 mm l-glutamine, 100 units ml−1 penicillin-streptomycin, and 6 g ml−1 glucose. Neurons were fed twice a week.

Hypothalamic slice preparation

Coronal hypothalamic slices, 400 μm thick, were cut on a vibratome from the brains of postnatal day 8-10 rats. Briefly, rats were anaesthetized with Nembutal (80 mg kg−1) and then decapitated. The brains were rapidly removed and immersed in cold (4 °C) oxygenated bath solution (containing (mm): NaCl 150, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, Hepes 10 and glucose 10, pH 7.3 with NaOH). Non-hypothalamic tissue was trimmed away, and slices were cut on a vibratome, and then transferred to a recording chamber. Slices were constantly perfused with bath solution at 2 ml min−1.

Electrophysiological recording

All culture experiments were performed at room temperature in neurons between 14 and 21 days in vitro. The recording chamber was continuously perfused at a rate of 2 ml min−1 with a bath solution containing (mm): NaCl 100, TEA-Cl 40, KCl 2.5, MgCl2 2, BaCl2 5, Hepes 10, glucose 10 and TTX 1 μM, pH 7.3 with NaOH. Whole-cell voltage clamp was used to observe voltage-dependent calcium currents with an L/M EPC-7 amplifier. The patch pipette was made of borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments) with a Narishige puller (PP-83). The tip resistance of the recording pipettes was 4-6 MΩ after filling with a pipette solution containing (mm): CsCl 135, MgCl2 1, Hepes 10, BAPTA-Cs 5, Mg-ATP 2 and Na2-GTP 0.5, pH 7.3 with CsOH. After a gigaohm seal and whole-cell access was achieved, the series resistance was between 15 and 30 MΩ and partially (40-60 %) compensated by the amplifier. Both seal resistance and series resistance were monitored throughout experiments. The liquid junction potential (about -9.1 mV) was compensated before giving a voltage command. Only those recordings with an initial seal resistance higher than 0.8 GΩ and stable series resistance were used.

Activation of the voltage-dependent calcium channels was induced by a voltage step from -80 mV to 0 mV with a duration of 100 ms. The I-V relationship was tested with a series of voltage steps (from -60 mV to +50 mV at increments of 10 mV) at a holding potential of -80 mV. The test protocol was applied to the recorded neurons before, during, and after application of MCH. To observe pre-pulse depression of MCH actions, the following test protocol was used: (100 ms) after a control test pulse (from -80 mV to -10 mV) a voltage step (facilitating pulse) from -80 mV to 100 mV was applied for 150 ms. Immediately after the facilitating pulse, another test pulse (from -80 mV to -10 mV, 100 ms duration) was applied. Five concentrations of MCH (0.1, 1, 10, 100 and 1000 nm) were used to test the dose response of MCH. After each set of calcium experiments, 200 μM of the calcium channel blocker CdCl2 was applied to the recorded neurone to ensure the recording of calcium currents. This data would also be used to subtract leak current and other artefacts from the original recordings.

To identify the effect of MCH on L-, N- and P/Q-type calcium channels, the following protocol was used. First, stable recording of voltage-dependent calcium currents (named IC for control) were obtained, as described above. Then 100 nm MCH was applied to the recorded neurone for 30 s, and calcium currents in the presence of MCH were recorded (IM). Finally, calcium currents were tested after MCH washout. After calcium currents returned to baseline, a calcium-channel subtype blocker (such as nimodipine) was applied to the recorded neurone; the calcium currents were considered to be IB after no further decrease in calcium currents was observed in the presence of the calcium-channel subtype blocker. Finally, 100 nm MCH plus the blocker were applied to the recorded neurone for 30 s and washed out with bath containing the blocker. The calcium currents in the presence of MCH and the blocker were named IM+B. Data were analysed with Axograph software. Each subtype of calcium current could be calculated by subtracting IB from IC, and the subtype currents in the presence of MCH could be obtained by subtracting IM+B from IM. If the rundown of recorded currents exceeded 10 %, suggesting a non-stable recording, the whole set of data was rejected. Separate sets of experiments were run using L-, M-, and P/Q-type calcium channel blockers. After an initial wait of 10 min, recordings could last > 2 min, and rundown of calcium currents could occur. In a set of control experiments, we measured rundown to be 4.6 ± 1.7 % (n = 7) over the course of the recording. The effect of different calcium channel blockers and MCH on calcium current amplitude was compensated for this rundown.

Whole-cell recording was used to study the effects of MCH on calcium currents in slices of the LH. Whole-cell voltage clamp was used to observe voltage-dependent calcium currents. A protocol similar to that described above was used. MCH was applied to the recording chamber via bath application.

All data were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 5 kHz with an Apple Macintosh computer using AxoData 1.2.2 (Axon Instruments). Data were analysed with AxoGraph 3.5 (Axon Instruments) and plotted with Igor Pro software (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA). Curve-fitting for a dose-response relationship was performed with a macro within IgorPro3.1.

Calcium digital imaging

Synaptically active cultures of LH neurons grown on glass coverslips were loaded with fura-AM ester for 25 min, washed, and then placed into a microscope chamber with a volume of 185 μl. An Olympus IX70 microscope and a silicon-intensified target camera (Dage MTI) interfaced with Axon Imaging Workbench software and a computer-controlled filter wheel were used to acquire ratio images. Images were illuminated alternately with light at wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm. The system was calibrated with calcium standards from Molecular Probes. Details of calcium imaging can be found in our previous work (van den Pol et al. 1998).

Chemicals and drugs

MCH was obtained from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., CA, and Sigma, USA. The lyophilized peptide was reconstituted in bath solution to a concentration of 1 mm and stored at -70 °C. The stock solution was diluted 1000-fold to a working concentration of 1 μM or less just prior to use. 2-Amino-5-phosphono-pentanoic acid (AP5), 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2, 3-dione (CNQX) and bicuculline methobromide (BIC) were obtained from RBI (Research Biochemical International, USA). TTX was obtained from Alomone Laboratories (Jerusalem, Israel). PTX, ω-conotoxin GVIA, ω-conotoxin MVIIC and ω-agatoxin IVA were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

RESULTS

In earlier studies, MCH was reported to induce an intracellular calcium increase in transfected cultured non-neuronal cell lines, probably via an intracellular calcium store (Chambers et al. 1999; Lembo et al. 1999; Saito et al. 1999). In preliminary experiments in which we studied 127 LH neurons using digital calcium imaging, we did not find any intracellular calcium increase during application of 1 μM MCH. In control experiments, 30 mm KCl or 10 μM glutamate did induce a calcium increase in the same cultured neurons (data not shown). In contrast, we have found previously that MCH plays a dramatic inhibitory role in the regulation of glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic transmission in LH neurons (Gao & van den Pol, 2001). Our data suggest that the mechanism for MCH-induced inhibition is based on a reduction of voltage-dependent calcium channels. Here we address the question regarding which of the three primary types of calcium channels, L, N, or P/Q, might be involved in the MCH-mediated attenuation. Ba2+ was substituted for Ca2+ as a current carrier in our experiments. The following results are based on recording from 117 neurons.

We tested the actions of MCH in both slices and cultures of the LH with whole-cell recording. In cultures, we found that MCH caused a significant depression of voltage-dependent calcium currents. MCH induced a significant depression (range from 30 to 80 % depression at 1 μM, or less depression at smaller concentrations) in the voltage-dependent calcium current amplitude in 76 of 79 cultured LH neurons. As shown in an example of a typical response, immediately after the application of MCH (100 nm), the whole-cell calcium currents were decreased (to about 60 % of the control in the cell shown in Fig. 1). There was no significant change in the time constants of the activation and inactivation components of calcium currents in the presence of MCH; the control inactivation time constant was 693.8 ± 152.6 ms (n = 20), and in the presence of MCH it was 710.9 ± 163.1 ms (n = 20); the difference is not significant (P ≤ 0.1). The MCH-induced response desensitized and reached a steady state 15 s after the onset of MCH application. After washout of MCH, the whole-cell calcium currents rapidly returned to the pre-MCH control level. MCH from two different sources, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (98 % purity by HPLC) and Sigma (98 % purity by HPLC, peptide content 78 %) was tested and it was found that these products exerted similar effects on voltage-dependent calcium currents. MCH from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals was used in most of the following experiments.

Figure 1. Melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) depresses voltage-dependent calcium currents in cultured neurons and brain slices from the lateral hypothalamus (LH).

A, time course of MCH-induced inhibition of calcium currents in a cultured LH neurone, typical of the 76 LH neurons that responded to MCH. a, b and c, raw recordings at corresponding time points during the experiment. The concentration of MCH was 100 nm in this example. B, time course of MCH-induced inhibition of calcium current in an LH slice (n = 4). MHC (1 μM) was bath-applied to the recorded slice.

In LH slices we also found that MCH induced a decrease in calcium current amplitude. However, the time course of MCH-induced inhibition was substantially slower in slices than in cultures. Whereas cultured cells showed a peak response in about 5 s, LH slices took 20-40 s. Complete washout of the MCH effect (return to a stable, close to control level) in cultured neurons could be achieved in 5 s, whereas in slices recovery took about 45 s (nine times longer) or more, as shown in Fig. 1B. Our preliminary data from neurons in four LH slices demonstrated an MCH (1 μM)-mediated reduction in whole-cell calcium currents with a magnitude smaller than that found in cultured neurons. Calcium currents desensitize over time, and the time course in the slice was substantially greater than in the culture. To prevent complications due to desensitization and slow diffusion of the peptide into slices, for the remaining experiments that focussed on the question of the mechanistic actions of MCH on calcium channels, we used cultured LH neurons.

The MCH-induced inhibition of calcium currents as studied in cultured LH neurons desensitized rapidly, as shown in Fig. 2. To maximize activation of many receptors, we used MCH at a high concentration (1 μM) to test the desensitization. The desensitization rate was measured as the time required to reach half-maximal effect in the presence of MCH, as described elsewhere (Diversé-Pierluissi et al. 1996). From six tested neurons, we found the desensitization rate was 18.3 ± 1.6 s (n = 6).

Figure 2. Desensitization of MCH-induced inhibition of calcium currents.

Time course of desensitization of the calcium current inhibition induced by 1 μM MCH (n = 6).

MCH-induced inhibition of voltage-dependent calcium channels: dose-response

The dose-response relationship of the MCH-induced inhibitory effect on the voltage-dependent calcium channels was determined. Five concentrations (0.1, 1, 10, 100 and 1000 nm) of MCH were tested in 23 neurons. As shown in Fig. 3, the MCH-induced inhibitory effect was dose dependent; no more than two concentrations were tested per neurone, with the lower concentration always first. The lowest concentration of MCH tested was 0.1 nm, which induced a slight reduction in whole-cell calcium currents. After the application of 0.1 nm MCH, the average of calcium currents was 88.8 ± 3.0 % of control values (n = 6) i.e. the inhibition was only 11.2 ± 3.0 %. The MCH-mediated inhibition of whole-cell calcium currents intensified in parallel with increased concentrations of the peptide. At 1, 10, 100 and 1000 nm, the whole-cell calcium currents were 79.9 ± 4.3 % (n = 10), 67.1 ± 7.8 % (n = 8), 48.3 ± 8.8 % (n = 8) and 42.9 ± 4.1 % (n = 14) of control, respectively. The IC50 was between 1 and 10 nm. Using the macro provided with IgorPro, we obtained the parameters of this dose-response relationship as follows: Maximal value = 66.7, Dissociation constant (KD) = 7.86, Hill coefficient = 0.40. From the dose-response relationship curve, we determined the IC50 as 7.84 nm. Thus our data indicate that the MCH-mediated reduction in whole-cell calcium currents is dose dependent, and that neurons show a considerable sensitivity to MCH in the low nanomolar range.

Figure 3. Dose-dependence of the MCH effect.

A, raw data recorded from different neurons showing the effect of MCH at five different concentrations. B, dose-response relationship obtained from 23 neurons.

Voltage independence of MCH-induced inhibition

The I-V relationship represents the properties of certain ion channels in a range of membrane potentials. The modification of the I-V relationship of ion channels by neuroactive substances can supply important clues as to how those substances modulate ion channels. Neuromodulators (for example, neuropeptide Y and somatostatin) have been demonstrated to modulate voltage-gated calcium channels in a voltage-dependent manner. Here the hypothesis that MCH can depress voltage-gated calcium channels in a voltage-dependent manner was tested.

The I-V relationship of voltage-dependent calcium currents was tested by giving a series of voltage steps from -60 mV to +50 mV with an increment of 10 mV to the recorded neurons, which were held at -80 mV. The I-V relationship test protocol was applied to the recorded neurons before, during and after the application of MCH. As shown in Fig. 4, the maximal reduction in the whole-cell calcium currents occurred when recorded neurons were given a voltage step from the holding potential (-80 mV) to 0 mV; smaller changes were found at more negative membrane potentials (n = 8; Fig. 4C). The relative magnitude of MCH effects on calcium currents appeared to be fairly independent of voltage at membrane potentials generating robust calcium currents (between -20 and +20 mV). Thus, our data indicate that the MCH-induced depression of calcium currents was not typically voltage dependent.

Figure 4. Voltage dependence of the MCH-induced inhibition of calcium currents.

A, a, b and c represent raw data recorded before, during and after the application of MCH (1 μM), respectively. The test protocol was not designed to specifically test a T-type current. B, I-V relationship of calcium currents before (•), during (▪) and after (♦) the application of MCH (1 μM). The amplitude of current was measured at the peak of the calcium current. C, pooled data from eight neurons showing inhibition of calcium currents by MCH when recorded neurons were depolarized to each membrane potential. D, left, pre-pulse depression experiments before and during the application of MCH (1 μM); right, The attenuation of (relief from) MCH-mediated inhibition of calcium current for each of the 10 neurons tested is shown here by the 10 lines. The thick bar on the right is the mean pre-pulse attenuation for all 10 neurons.

Pre-pulse attenuation of the MCH-induced inhibition of calcium currents

Previous results have suggested that G-protein-mediated inhibition of calcium currents is reversed by a pre-pulse given prior to a test pulse (Harayama et al. 1998). In our experiment, a pre-pulse given prior to the test pulse reversed the MCH-induced inhibition in calcium currents, as shown in an example in Fig. 4D. In 6 out of 10 neurons, an attenuation greater than 10 % was found; the responses of all 10 recorded cells are shown in Fig. 4D. If the inhibition of calcium current by MCH before the pre-pulse was considered as 100 % (control), the inhibition of calcium currents by MCH after the pre-pulse was 84.7 ± 5.1 % of control (n = 10). A paired t test suggested that the attenuation of MCH-mediated inhibition of calcium currents was significant (P < 0.05, n = 10).

Involvement of G-proteins in MCH-induced inhibition

Experiments with non-neuronal cells transfected with the MCH receptor gene have suggested that the MCH receptor is coupled to G-proteins, particularly the Gi/Go protein (Lembo et al. 1999). Our previous data demonstrated that the inhibitory effect of MCH on neurotransmitter release was mediated by G-proteins (Gao & van den Pol, 2001). Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that the depressive action of MCH on voltage-dependent calcium currents may also be mediated by G-proteins. We tested this hypothesis from two different perspectives. First, we irreversibly activated G-protein with GTPγS and then tested whether MCH could induce further inhibition of calcium currents. In addition, we used a non-selective inhibitor of G-proteins, PTX, to test the effect of MCH.

G-protein pre-activation

GTPγS is a non-hydrolysable GTP analogue that irreversibly activates G-proteins. It has been demonstrated that inclusion of GTPγS in the recording pipette solution attenuates G-protein-mediated inhibition of calcium currents by other neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, including GABA (Harayama et al. 1998), neuropeptide Y (Bleakman et al. 1992) and noradrenaline (Trombley, 1992). In our experiments, 0.5 mm GTPγS was used to replace 0.5 mm GTP-Na2 in the pipette solution. Once the whole-cell configuration was established, GTPγS diffused into the recorded neurone and activated G-proteins, leading to an inhibition of voltage-dependent calcium currents within 10 min (data not shown). MCH (10 nm) in the absence of GTPγS caused a substantial decrease in calcium current (67.1 ± 7.8 % of control during MCH application, n = 8), as expected. In striking contrast, in the presence of GTPγS, little MCH-mediated depression was found (Fig. 5A); the calcium current was 93.4 ± 3.3 % of control during the application of 10 nm MCH (n = 5; P > 0.1). These data suggest that GTPγS blocks the inhibition of calcium currents induced by 10 nm MCH.

Figure 5. Pre-activation of G-proteins reduces or eliminates MCH-induced inhibition.

All experiments began 10 min after the formation of the whole-cell recording configuration to allow the complete diffusion of GTPγS (0.5 mm) from the pipettes. A, time course of a typical experiment with a low concentration (10 nm) of MCH after activation of G-proteins by GTPγS (n = 5). a, b and c are raw recordings before, during and after the application of 10 nm MCH, respectively. B, time course of a typical experiment with a high concentration of MCH (100 nm) after activation of G-proteins (n = 7). a, b and c represent the recordings before, during and after the application of MCH (100 nm), respectively. C, bar graph comparing MCH actions on calcium currents with and without GTPγS (n = 8 for 10 nm and n = 8 for 100 nm) in the recording pipette.

Figure 6. Pre-treatment with PTX blocks the MCH-evoked reduction in calcium currents.

Bar graph showing the effect of MCH (1 μM) on calcium currents in non-PTX-treated (n = 14) and PTX-treated cultures (n = 5).

We also tried a greater concentration of MCH in the presence of GTPγS. In the absence of GTPγS, 100 nm MCH depressed calcium currents to 48.3 ± 8.8 % of control levels (n = 8). In the presence of 0.5 mm GTPγS in the pipette solution, the effect of 100 nm MCH was compared. As shown in Fig. 5B, the calcium current was 87.3 ± 2.8 % of control during the application of 100 nm MCH (n = 7), a smaller magnitude of depression. The effect of MCH was significantly reduced by the GTPγS (P < 0.05).

Thus, these data based on two concentrations of MCH (10 and 100 nm) suggest that pre-activation of G-proteins blocks, to a large degree, the inhibition of calcium currents induced by MCH.

G-protein inhibitor

It has been demonstrated that PTX, a non-selective G-protein inhibitor, blocks G-protein-mediated inhibition of voltage-dependent calcium currents (Bleakman et al. 1992; Trombley, 1992; Harayama et al. 1998). Our previous results indicated that PTX blocked the MCH-mediated inhibition of synaptic transmission. To determine whether the MCH-mediated effects on calcium currents were also sensitive to PTX, we first treated LH cultures with 300 ng ml−1 PTX for 48 h, and then tested the effect of MCH on calcium currents. In neurons pre-treated with PTX, the normal MCH-mediated inhibition of calcium currents was not observed. In control cultured cells (n = 14), MCH attenuated calcium currents to 42.9 ± 4.1% of control. In contrast, MCH reduced calcium currents to 82.3 ± 6.9% of control after PTX treatment (n = 5), a statistically significant difference (P < 0.01).

The effect of MCH on L-, N-, and P/Q-type calcium channels in LH neurons

Different subtypes of voltage-dependent calcium channels make different contributions to neuronal function. For instance, L-type calcium channels are localized primarily in the soma and proximal dendrites (Ahlijanian et al. 1990; Westenbroek et al. 1990). Several lines of evidence suggest that L-type calcium channels play a crucial role in the regulation of gene transcription (Catterall, 1998). In contrast, it has been demonstrated that N- and P/Q-type channels are involved in transmitter release at the presynaptic terminals (Turner et al. 1993). N- and P/Q-type calcium currents were present at presynaptic terminals (Westenbroek et al. 1992, 1995). Fast synaptic transmission is attenuated by N- and/or P/Q-type calcium channel blockers (Hirning et al. 1988; Chen & van den Pol, 1996; Zeilhofer et al. 1996; Catterall, 1998). In the study presented here, the effect of MCH on L-, N- and P/Q-type channels was investigated.

In order to study the effects of MCH on selective calcium channels, we first needed to define the channels that were active on these neurons. The relative contribution of L-, N- and P/Q-type channels to the whole-cell calcium currents in LH neurons has not previously been examined. We used selective calcium channel blockers at concentrations similar to those used in previous reports (Randall & Tsien, 1995; Viana & Hille, 1996; Chen & van den Pol, 1998). Nimodipine (8 μM), ω-conotoxin GVIA (4 μM), or ω-conotoxin MVIIC (2 μM) plus ω-agatoxin IVA (50 nm) were used to block L-, N- and P/Q-type calcium channels, respectively. After rundown correction, in the presence of 8 μM of the L-channel blocker nimodipine, calcium currents were reduced to 63.5 ± 6.2 % of control values (n = 8), as shown in Fig. 7Aa. In the presence of 4 μM of the N-channel blocker ω-conotoxin GVIA, calcium currents were 60.6 ± 4.7 % (n = 7) of control values, as shown in Fig. 7Ab. In the presence of the P/Q-channel blockers ω-conotoxin MVIIC (2 μM) and 50 nm ω-agatoxin IVA, calcium currents were 87.0 ± 5.3 % (n = 6) of control values, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7. Relative contribution of L-, N- and P/Q-type channels to somatic calcium currents in LH neurons.

A: a, b and c show raw traces. Trace 1 shows control calcium currents. Trace 2 shows calcium currents in the presence of a blocker (8 μM nimodipine in a, 4 μM ω-conotoxin GVIA in b, and 2 μM ω-conotoxin MVIIC + 50 nm ω-agatoxin IVA in c). B, bar graph showing the percentage of each of three subtypes of calcium channels in the whole-cell calcium currents (n = 8 for L-type, n = 7 for N-type and n = 6 for P/Q-type currents).

As calcium channel subtypes may vary in their functions, MCH may influence a variety of neuronal functions through modulating different calcium channel subtypes. Therefore, the relative effect of MCH on each subtype of calcium channels was determined. Some neuropeptides may selectively modulate one type of channel over another type (Chen & van den Pol, 1998). In the study presented here, a subtraction method was used to isolate each type of calcium current and identify the effect of MCH on these calcium-current subtypes, based on the difference in MCH action in the presence or absence of a single selective calcium channel blocker (Randall & Tsien, 1995; Sidach & Mintz, 2000; Sun et al. 2001). Because the subtraction method requires stable recording conditions during the experiments, strict criteria were adopted to control for rundown and changes in access resistance, as described in Methods. A graph representing the time course of such experiments is shown in the inset in Fig. 8. An alternate approach based on blocking all calcium channel types except the one of interest is also feasible, but can be complicated by the difficulty in blocking T- and R-currents, and because multiple blockers used simultaneously may not be additive (Zeihofer et al. 1996).

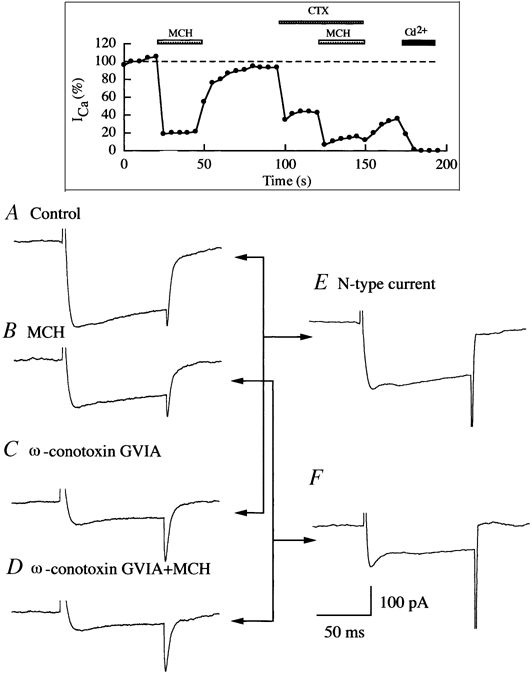

Figure 8. MCH depresses N-type calcium currents (an example).

A-D, calcium currents recorded in our experiments in control bath, MCH (100 nm), ω-conotoxin GVIA (4 μM) solution and ω-conotoxin GVIA (4 μM) plus MCH (100 nm) solution. E, N-type calcium current. This trace was obtained by subtracting trace C from trace A. F, N-type calcium current in the presence of MCH. This trace was obtained by subtracting trace D from trace B. Inset, time course of a typical experiment. Rundown of calcium currents was consistently < 10 %. After the whole set of experiments, 200 μM CdCl2 was applied to the recorded neurons to block the recorded current to ensure the recording of calcium current as described in Methods. CdCl2 completely blocked calcium currents.

An example of our analysis of calcium data is given in Fig. 8, which describes how the effect of MCH on N-type currents was determined. Using the procedure described in Methods, the calcium currents in control bath (Fig. 8A), MCH solution (Fig. 8B), ω-conotoxin GVIA solution (Fig. 8C) and ω-conotoxin plus MCH solution (Fig. 8D) were obtained. ω-conotoxin GVIA at 4 μM blocked almost all N-type currents, thus trace C in Fig. 8 represents the non-N-type component of whole-cell calcium currents. We obtained N-type calcium currents by subtracting trace C from trace A (Fig. 8E). According to the same rationale, trace B in Fig. 8 represents all components of calcium currents in the presence of MCH and trace D represents non-N-type components of calcium currents in the presence of MCH. The difference between trace B and trace D represents the contribution of N-type calcium currents in the presence of MCH (Fig. 8F). Comparing traces E and F, we obtain the percentage change in the amplitude of N-type calcium currents induced by MCH in recorded LH neurons.

Using the analysis procedure just described, the effect of MCH on L-, N- and P/Q-type calcium currents was examined. We found that in the presence of 100 nm MCH, the L-, N- and P/Q- type currents were significantly (P < 0.01) reduced to 60.1 ± 3.1 % (n = 8), 44.6 ± 5.4 % (n = 6) and 60.3 ± 4.9 % (n = 6), respectively, of their control level (Fig. 9). This represents a significant difference in the inhibitory effects of MCH on L-, N- and P/Q-type calcium channels (P < 0.05, ANOVA test). MCH evoked a greater depression of calcium currents in N-type channels (55 % decrease) than in L- or P/Q-type channels (40 % decreases) (P < 0.05, one-tailed Dunnett's test).

Figure 9. Inhibition of L-, N- and P/Q-type calcium currents by MCH.

A: a, b and c represent L-, N- and P/Q-type calcium currents, respectively, before (represented by dotted lines) and during (represented by continuous lines) application of 100 nm MCH. These traces were obtained using the procedure described in Fig. 8. B, bar graph comparing the percentage depression of L-type (n = 8), N-type (n = 6) and P/Q-type (n = 6) calcium currents to their control levels during the application of MCH.

To test the effect of MCH on the remaining calcium currents made up of R- and probably T-type currents, nimodipine (8 μM), ω-conotoxin GVIA (4 μM), and ω-conotoxin MVIIC (2 μM) plus ω-agatoxin IVA (50 nm) were applied simultaneously to block L-, N- and P/Q-type currents. A residual current of 26.6 ± 3.3 % (n = 11) of the control current remained in the presence of the blockers. When MCH (100 nm) was applied to the recorded neurons in the presence of all these blockers, the residual calcium current showed no further decrease (from 26.3 ± 3.3 % to 24.0 ± 2.9 %, statistically not significant; t test, n = 5,P > 0.5). This experiment demonstrates that about 26 % of the calcium current in made up of T- and R-type currents, and that MCH has little effect on these currents.

Taken together, these data suggest that MCH causes a significant selective depression of L-, N- and P/Q-type calcium channels in these LH neurons.

DISCUSSION

Although MCH axons and receptors are found throughout the brain and play important roles in hypothalamic function, we are aware of no previous studies on the ionic mechanisms of MCH actions in neurons. In the present study we describe the inhibitory effect of MCH on voltage-dependent calcium currents in LH neurons. MCH inhibited voltage-dependent calcium currents in a dose-dependent manner, with robust responses detected in the low-nanomolar MCH range. MCH-induced actions desensitized rapidly. Pre-treatment with GTPγS to activate G-proteins reduced or eliminated MCH-induced inhibition of calcium currents. Similarly, pre-treatment of LH neurons with PTX blocked the effect of MCH on calcium currents, indicating the occurrence of a Gi/Go protein coupling. N- and L-type calcium currents were the dominant components of whole-cell calcium currents recorded from the LH neuronal soma. MCH caused a substantial inhibition of N-type calcium currents, and also attenuated L-type and P/Q-type currents. These results indicate strikingly distinct properties from those reported in non-neuronal cells for MCH.

MCH actions in LH neurons are different from non-neuronal cells

The cellular actions of MCH were first studied in non-neuronal expression systems using cell lines such as human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells or Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with the MCH receptor, SLC-1 (Chambers et al. 1999; Lembo et al. 1999; Saito et al. 1999). These systems provided initial clues for the actions of the MCH receptor and the association between MCH receptors and intracellular signal transduction pathways. Three physiological characteristics of MCH were suggested (Saito et al. 2000). The first finding for all three reports was that MCH induced an increase in calcium, possibly by activation of the phospholipase C pathway via a Gαq/i3 protein. In contrast, in neurons we found no increase in calcium with digital imaging. Instead, based on whole-cell recording, we found that MCH evoked a very robust and consistent inhibition of calcium currents. A second finding reported for non-neuronal cells was that MCH activated a G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channel (GIRK) in Xenopus oocytes co-expressing the MCH receptor and GIRK channels (Bächner et al. 1999; Saito et al. 2000). We were unable to find an effect of MCH on voltage-dependent potassium currents (Gao & van den Pol, 2001), and in pilot data on five cells, found no MCH activation of a GIRK current; in contrast, the GABAB agonist baclofen did activate GIRK currents in control experiments. Previous work has shown that the coexpression of MCH receptors and GIRK channels was necessary in Xenopus oocytes in order to detect activation by MCH (Bächner et al. 1999). In contrast, despite the expression of MCH receptors and the presence of GIRK currents in LH cells, MCH still did not appear to activate GIRK currents, suggesting that MCH is not commonly coupled with GIRK channels here.

A third feature of MCH in non-neuronal cells was the reduction of forskolin-elevated intracellular cAMP levels via the Gi pathway (Chambers et al. 1999; Saito et al. 1999). In neurons, we found a parallel mechanism, as pre-treatment with PTX or activation of G-proteins by GTPγS blocked MCH actions. Our data suggest that MCH primarily elicits inhibitory effects via a PTX-sensitive Gi/Go pathway in LH neurons. Thus, our data in neurons parallel those obtained in non-neuronal cells in only one out of three mechanistic pathways. The possibility remains that neurons in other brain loci may display additional activities of MCH not found in the present study. However, in a pilot study in cultured neurons (n = 5) from the hippocampus, a region that has both MCH receptors and MCH-immunoreactive axons (Bittencourt et al. 1992; Saito et al. 2001), we found an MCH-induced reduction in calcium currents similar to that described here for slices and cultures of LH neurons.

MCH depresses voltage-dependent calcium currents

Voltage-dependent calcium currents serve a number of important roles in neurons, facilitating the transfer of electrical signals into biochemical signals within neurons and controlling a number of important neuronal functions. The inhibition of calcium currents by MCH possessed several properties that characterize modulation of voltage-dependent calcium currents by G-proteins, such as rapid inhibition onset, desensitization and dependence on available G-proteins. The rapid inhibition induced by MCH suggests that it occurs via a membrane-delimited pathway rather than via diffusible intracellular messengers (Hille, 1994). Desensitization of G-protein-coupled receptors has been studied in neuronal cultures; calcium channels were inhibited by opioid modulators (Nomura et al. 1994), noradrenaline (Diversé-Pierluissi et al. 1996), somatostatin (Beaumont et al. 1998), and nociceptin (Morikawa et al. 1998). To the best of our knowledge, the desensitization (desensitization rate = 18.3 s to half-maximum) observed in our MCH study was the fastest among those observed for these modulators. For comparison, the desensitization rate for noradrenaline-induced calcium-channel inhibition was about 100 s (Diversé-Pierluissi et al. 1996).

Previous data suggested that a strong depolarizing pre-pulse could relieve the voltage-dependent inhibition of N- or P/Q-type calcium currents by G-proteins (Catterall, 2000). Consistent with that view, in the present study, a pre-pulse partially reversed MCH-mediated inhibition of whole-cell calcium currents. That the pre-pulse inhibition was not complete might be due to the presence of the L-type calcium channels described here in LH cells, as previous data have suggested that this channel subtype is substantially less sensitive to voltage-dependent G-protein inhibition. Previous work with other peptides that may also activate a Gi/Go pathway has shown that they may slow activation of the N-type calcium current (Catterall, 2000). We observed this slowed activation with MCH only infrequently. This infrequency could be due to multiple second-messenger systems involved in the MCH-mediated effect in addition to the G-protein pathways in LH neurons. The other possibility is that the high access resistance (15-30 MΩ) during our recording could slow the detection of changes in calcium currents, and this could reduce the probability of observing a slowing effect of MCH on the activation of calcium currents.

Different calcium channels may play distinct roles in different neuron types within the CNS. In LH neurons, we found L-, N-, and P/Q-type calcium currents. Previous work in the hippocampus has suggested that the dominant current at the cell body is the L-type current (Elliott et al. 1995). In contrast, our data suggest that N- and L-type currents contributed similarly to LH neurons. This type of analysis is complicated by the issue of blocker concentration, with too low a concentration resulting in incomplete block of a channel, and too high a concentration potentially resulting in less-selective blockade; we used concentrations similar to those used in previous reports on selective block of specific calcium channels. Our results relating to the relative contribution of different calcium channel subtypes parallel observations in other hypothalamic neurons, for instance those of the supraoptic nucleus (Harayama et al. 1998). According to our results, MCH inhibits all three subtypes of calcium currents tested here, consistent with the actions of another receptor that also activates a Gi/Go protein, the GABAB receptor as studied in supraoptic nucleus neurons (Harayama et al. 1998). The greatest effect of MCH was on N-type currents. The inhibition of N- and P/Q-type of calcium currents via G-proteins is consistent with previous reports (Dascal, 2001). N- and P/Q-type currents have been reported to occur at axon terminals. We did not study MHC-induced inhibition of N- and P/Q-type calcium channels at nerve terminals directly; however, our data suggest that those channels are targets of MCH. This is consistent with our previous observations that MCH depresses glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic transmission (Gao & van den Pol, 2001).

The modulation of L-type calcium currents by MCH as revealed by our data is equally important. It has been reported that L-type calcium channels are modulated by G-proteins in a voltage-independent manner (Maguire et al. 1989; Sayer et al. 1992; Haws et al. 1993; Amico et al. 1995) and in a voltage-dependent manner (Keja & Kits, 1994). At depolarizations to voltages that generated robust inward calcium currents, we found the magnitude of MCH actions to be independent of voltage. L-type calcium currents may be modulated by mechanisms different from those that result in inhibition of N- and P/Q-type calcium currents (Kleuss et al. 1991; Shapiro et al. 1999; Akopian et al. 2000). Recently, an emerging body of data has suggested the possibility that the L-type calcium channel is modulated by G-proteins both indirectly and directly. First, the L-type calcium channel might form a complex with a G-protein, an adenylyl cyclase, cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) and phosphatase PP2A within neurons (Davare et al. 2001). It has been demonstrated that the activation of PKA is important for the up-regulation of L-type calcium current in neurons (Gray & Johnston, 1987; Gross et al. 1990). MCH has been reported to inhibit the increase of cAMP induced by forskolin via a Gi pathway in non-neuronal cells (Chambers et al. 1999; Saito et al. 1999). Thus, the inhibition of L-type calcium currents by MCH in LH neurons may be due to MCH-induced inhibition of cAMP accumulation. Secondly, the Gβγ subunit and calmodulin may bind directly to the α1C subunit of the L-type calcium channel. When the Gβγ subunit was coexpressed with the channel, the L-type calcium current was reduced (Ivanina et al. 2000). The macromolecular signalling complexes suggested by Davare et al. (2001) might contribute to the various G-protein-mediated effects.

There are several lines of evidence that calcium influx via L-type channels plays a crucial role in excitation-transcription coupling in neurons (Catterall, 1998). The activation of transcription of immediate-early genes by repetitive electrical activity was found to depend primarily on calcium influx via L-type channels (Murphy et al. 1991). Activation of the cAMP- and calcium-dependent transcription factor CREB required calcium influx via L-type calcium channels and NMDA receptors in hippocampal cell cultures and slices (Bading et al. 1993; Abel et al. 1997). Recently, it was found that glutamate-mediated CREB phosphorylation and c-fos gene expression was solely dependent upon L-type calcium channels in striatal neurons (Rajadhyaksha et al. 1999). Therefore, our data suggest that MCH may have immediate effects on information flow within the brain by modulating synaptic transmission, and possible long-term effects on the brain function mediated by changes in calcium-regulated gene expression in neurons.

MCH receptor and brain function

MCH receptor mRNA is found throughout the brain (Saito et al. 2001). It is not known whether this MCH mRNA is translated into protein, or how the level of message correlates with functional receptor. The effect of MCH on voltage-dependent calcium currents reported here was observed in almost all of the LH neurons tested. Whole-cell recording represents a sensitive approach to determining the existence of functional MCH receptors. Identifying functional MCH receptors will help to elucidate the targets of the MCH system and further establish the role of MCH in complex physiological functions including energy homeostasis. Recently, a second human MCH receptor, named SLT or MCH-2R, has been described (Mori et al. 2001; Hill et al. 2001; Sailer et al. 2001), and it was suggested that it is coupled to a Gq-protein pathway. The distribution of this newly identified receptor within the brain is not clear at this time due to non-congruent anatomical descriptions (Mori et al. 2001; Sailer et al. 2001). Our previous results showed that activation of a Gq pathway mediated an excitatory effect in LH slices and cultures when stimulated by hypocretin/ orexin (de Lecea et al. 1998; van den Pol et al. 1998, 2001). Therefore, the MCH-induced inhibitory effect on calcium currents in LH neurons is probably not mediated by this newly discovered second MCH receptor.

In considering the physiological actions of MCH at the cellular level, one is struck by the relative rapidity of MCH actions compared with other hypothalamic peptides. Very low nanomolar levels of MCH induce a rapid inhibition of synaptic activity and calcium currents, and these recover quickly after washout. MCH effects rapidly desensitize, a factor that would tend to limit the temporal effects of MCH. In contrast, the inhibitory actions of hypothalamic neuropeptide Y may last for 1 h after peptide washout (van den Pol et al. 1996), and another hypothalamic neuromodulator, neurotropin-3, takes several minutes to exert a maximal excitatory effect, an effect that is maintained for an extended period after washout (Gao & van den Pol, 1999). Thus, in considering MCH actions at the level of LH synaptic integration, the quick time course of MCH actions suggests that it is involved in the rapid modulation of circuitry in the LH and beyond, perhaps both at pre- and postsynaptic sites of action. If MCH cells express MCH receptors, our data would suggest that the peptide serves as a negative feedback signal, particularly as MCH axons have their highest density near the cells of origin. As the LH integrates a host of sensory information (Rolls et al. 1986) with homeostatic regulation, MCH may participate to rapidly modulate input or outflow at a considerably more precise temporal constraint than many of the other peptides acting in the LH.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association (X.B.G) and US NIH NS31573, NS10174, NS34887, and the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Abel T, Nguyen PV, Barad M, Deuel TA, Kandel ER, Bourtchouladze R. Genetic demonstration of a role for PKA in the late phase of LTP and in hippocampus-based long-term memory. Cell. 1997;88:615–626. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81904-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlijanian MK, Westenbroek RE, Catterall WA. Subunit structure and localization of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels in mammalian brain, spinal cord, and retina. Neuron. 1990;4:819–832. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akopian A, Johnson J, Gabriel R, Brecha N, Witkovsky P. Somatostatin modulates voltage-gated K+ and Ca2+ currents in rod and cone photoreceptors of the salamander retina. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:929–936. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-00929.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amico C, Marcheti C, Nobile M, Usai C. Pharmacological types of calcium channels and their modulation by baclofen in cerebellar granules. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:2839–2848. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02839.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bächner D, Kreienkamp H, Weise C, Buck F, Richter D. Identification of melanin concentrating hormone (MCH) as the natural ligand for the orphan somatostatin-like receptor 1 (SLC-1) FEBS Letters. 1999;457:522–524. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bading H, Ginty DD, Greenberg ME. Regulation of gene expression in hippocampal neurons by distinct calcium signaling pathways. Science. 1993;260:181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.8097060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont V, Hepworth MB, Luty JS, Kelly E, Henderson G. Somatostatin receptor desensitization in NG108–15 cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:33174–33183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt JC, Presse F, Arias C, Peto C, Vaughan J, Nahon J -L, Vale W, Sawchenko PE. The melanin-concentrating hormone system of the rat brain: an immuno- and hybridization histochemical characterization. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1992;319:218–245. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakman D, Harrison NL, Colmers WF, Miller RJ. Investigations into neuropeptide Y-mediated presynaptic inhibition in cultured hippocampal neurones of the rat. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;107:334–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb12747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli E, Genassani A, Guerini D. Calcium controls the transcription of its own transporters and channels in developing neurons. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1999;266:625–632. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Structure and function of neuronal Ca2+ channels and their role in neurotransmitter release. Cell Calcium. 1998;24:307–323. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers J, Ames RS, Bergsma D, Muir A, Fitzgerald LR, Hervieu G, Dytko GM, Foley JJ, Martin J, Liu WS, Park J, Ellis C, Ganguly S, Konchar S, Cluderay J, Leslie R, Wilson S, Sarau HM. Melanin-concentrating hormone is the cognate ligand for the orphan G-protein-coupled receptor SLC-1. Nature. 1999;400:261–265. doi: 10.1038/22313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, van den Pol AN. Multiple NPY receptors coexist in pre- and postsynaptic sites: inhibition of GABA release in isolated self-innervating SCN neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:7711–7724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07711.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, van den Pol AN. Presynaptic GABAB autoreceptor modulation of P/Q-type calcium channels and GABA release in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:1913–1922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01913.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiocchio SR, Gallardo MG, Louzan P, Gutnisky V, TrameANIZZ JH. Melanin-concentrating hormone stimulates the release of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone and gonadotropins in the female rat acting at both median eminence and pituitary levels. Biology of Reproduction. 2001;64:1466–1472. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.5.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascal N. Ion-channel regulation by G proteins. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;12:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00475-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davare MA, Avdonin V, Hall DD, Peden EM, Burette A, Weinberg RJ, Horne MC, Hoshi T, Hell JW. A beta2 adrenergic receptor signaling complex assembled with the Ca2+ channel Cav1. 2. Science. 2001;293:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5527.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diversé-pierluissi M, Inglese J, Stoffel RH, Lefkowitz RJ, Dunlap K. G-protein-coupled receptor kinase mediates desensitization of norepinephrine-induced Ca2+ channel inhibition. Neuron. 1996;16:579–585. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott EM, Malouf AT, Catterall WA. Role of calcium channel subtypes in calcium transients in hippocampal CA3 neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:6433–6444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06433.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XB, van den Pol AN. Neurotrophin-3 potentiates excitatory GABAergic synaptic transmission in cultured developing hypothalamic neurones of the rat. Journal of Physiology. 1999;518:81–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0081r.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XB, van den Pol AN. Melanin concentrating hormone depresses synaptic activity of glutamate and GABA neurons from rat lateral hypothalamus. Journal of Physiology. 2001;533:237–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0237b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray R, Johnston D. Noradrenaline and beta-adrenoceptor agonists increase activity of voltage-dependent calcium channels in hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1987;327:620–622. doi: 10.1038/327620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross RA, Uhler MD, MacDonald RL. The cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit selectively enhances calcium currents in rat nodose neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1990;429:483–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harayama N, Shibuya I, Tanaka K, Kabashima N, Ueta Y, Yamashita H. Inhibition of N- and P/Q-type calcium channels by postsynaptic GABAB receptor activation in rat supraoptic neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1998;509:371–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.371bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haws CM, Slesinger PA, Lansman JB. Dihydropyridine- and omega-conotoxin-sensitive Ca2+ currents in cerebellar neurons: persistent block of L-type channels by a pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:1148–1156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01148.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J, Duckworth M, Murdock P, Rennie G, Sabido-david C, Ames RS, Szekeres P, Wilson S, Bergsma DJ, Gloger IS, Levy DS, Chambers JK, Muir AI. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of MCH2, a novel human MCH receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:20125–20129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Modulation of ion-channel function by G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends in Neuroscience. 1994;17:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirning LD, Fox AP, McCleskey EW, Olivera BM, Thayer SA, Miller RJ, Tsien RW. Dominant role of N-type Ca2+ channels in evoked release of norepinephrine from sympathetic neurons. Science. 1988;239:57–61. doi: 10.1126/science.2447647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang QL, Viale A. Effects of leptin on melanin-concentrating hormone expression in the brain of lean and obese Lepob/Lepob mice. Neuroendocrinology. 1999;69:145–153. doi: 10.1159/000054413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanina T, Blumenstein Y, Shistik E, Barzilai R, Dascal N. Modulation of L-type Ca2+ channels by gbeta gamma and calmodulin via interactions with N and C termini of alpha 1C. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:39846–39854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keja JA, Kits KS. Voltage dependence of G-protein-mediated inhibition of high-voltage-activated calcium channels in rat pituitary melanotropes. Neuroscience. 1994;62:281–289. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilduff TS, De Lecea L. Mapping of the mRNAs for the hypocretin/orexin and melanin-concentrating hormone receptors: networks of overlapping peptide systems. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;435:1–5. doi: 10.1002/cne.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleuss C, Hescheler J, Ewel C, Rosenthal W, Schultz G, Wittig B. Assignment of G-protein subtypes to specific receptors inducing inhibition of calcium currents. Nature. 1991;353:43–48. doi: 10.1038/353043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembo PM, GraINIZZ E, Cao J, Hubatsch DA, Pelletier M, Hoffert C, St-Onge S, Pou C, Labrecque J, Groblewski T, O'Donnell D, Payza K, Ahmad S, Walker P. The receptor for the orexigenic peptide melanin-concentrating hormone is a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature Cell Biology. 1999;1:267–271. doi: 10.1038/12978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig DS, Tritos NA, Mastaitis JW, Kulkarni R, Kokkotou E, Elmquist J, Lowell B, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E. Melanin-concentrating hormone overexpression in transgenic mice leads to obesity and insulin resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107:379–386. doi: 10.1172/JCI10660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire G, Maple B, Lukasiewicz P, Werblin F. Gamma-aminobutyrate type B receptor modulation of L-type calcium channel current at bipolar cell terminal in the retina of the tiger salamander. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86:10144–10147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monzon ME, De Souza MM, Izquierdo LA, Izquierdo I, Barros DM, De Barioglio SR. Melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) modifies memory retention in rats. Peptides. 1999;20:1517–1519. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, Harada M, Terao Y, Sugo T, Watanabe T, Shimomura Y, Abe M, Shintani Y, Onda H, Nishimura O, Fujino M. Cloning of a novel g protein-coupled receptor, slt, a subtype of the melanin-concentrating hormone receptor. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001;283:1013–1018. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa H, Fukuda K, Mima H, Shoda T, Kato S, Mori K. Nociceptin receptor-mediated Ca2+ channel inhibition and its desensitization in NG108–15 cells. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;351:247–252. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TH, Worley PF, Baraban JM. L-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels mediate synaptic activation of immediate early genes. Neuron. 1991;7:625–635. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90375-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K, Reuveny E, Narahashi T. Opioid inhibition and desensitization of calcium channel currents in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;270:466–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu D, Ludwig DS, Grammeltpft S, Piper M, Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ, Mathes WF, Przypek J, Kanarek R, Maratos-Flier E. A role of melanin-concentrating hormone in the central regulation of feeding behavior. Nature. 1996;380:243–247. doi: 10.1038/380243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajadhyaksha A, Barczak A, Macias W, Leveque JC, Lewis SE, Konradi C. L-Type Ca(2+). channels are essential for glutamate-mediated CREB phosphorylation and c-fos gene expression in striatal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:6348–6359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06348.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall A, Tsien RW. Pharmacological dissection of multiple types of Ca2+ channel currents in rat cerebellar granule neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:2995–3012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02995.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Murzi E, Yaxley S, Thorpe SJ, Simpson SJ. Sensory-specific satiety: food-specific reduction in responsiveness of ventral forebrain neurons after feeding in the monkey. Brain Research. 1986;368:79–86. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M, Choi SJ, O'Shea D, Miyoshi T, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Melanin-concentrating hormone acutely stimulates feeding, but chronic administration has no effect on body weight. Endocrinology. 1997;138:351–355. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.1.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sailer AW, Sano H, Zeng Z, McDonald TP, Pan J, Pong SS, Feighner SD, Tan CP, Fukami T, Iwaasa H, Hreniuk DL, Morin NR, Sadowski SJ, Ito M, Ito M, Bansal A, Ky B, Figueroa DJ, Jiang Q, Austin CP, MacNeil DJ, Ishihara A, Ihara M, Kanatani A, Van Der Ploeg LH, Howard AD, Liu Q. Identification and characterization of a second melanin-concentrating hormone receptor, MCH-2R. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:7546–7569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121170598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Cheng M, Leslie FM, Civelli O. Expression of the melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) receptor mRNA in the rat brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;435:26–40. doi: 10.1002/cne.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Nothacker HP, Civelli O. Melanin-concentrating hormone receptor: an orphan receptor fits the key. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;11:299–303. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Nothacker HP, Wang Z, Lin SH, Leslie F, Civelli O. Molecular characterization of the melanin-concentrating-hormone receptor. Nature. 1999;400:265–269. doi: 10.1038/22321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawchenko PE. Toward a new neurobiology of energy balance, appetite, and obesity: the anatomists weigh in. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1998;402:435–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer RJ, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated suppression of L-type calcium current in acutely isolated neocortical neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;68:833–842. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.3.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MS, Loose MD, Hamilton SE, Nathanson NM, Gomeza J, Wess J, Hille B. Assignment of muscarinic receptor subtypes mediating G-protein modulation of Ca2+ channels by using knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:10899–10904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Tritos NA, Lowell BB, Flier LS, Maratos-Flier E. Mice lacking melanin-concentrating hormone are hypophagic and lean. Nature. 1998;396:670–674. doi: 10.1038/25341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidach SS, Mintz IM. Low-affinity blockade of neuronal N-type Ca channels by the spider toxin ω-agatoxin-IVA. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:7174–7182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07174.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q -Q, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Neuropeptide Y receptors differentially modulate G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels and high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in rat thalamic neurons. Journal of Physiology. 2001;531:67–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0067j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombley PQ. Norepinephrine inhibits calcium currents and EPSPs via a G-protein-coupled mechanism in olfactory bulb neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:3992–3998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-03992.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TJ, Adams ME, Dunlap K. Multiple Ca2+ channel types coexist to regulate synaptosomal neurotransmitter release. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:9518–9522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol AN, Gao XB, Obrietan K, Kilduff TS, Belousov AB. Presynaptic and postsynaptic actions and modulation of neuroendocrine neurons by a new hypothalamic peptide, hypocretin/orexin. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:7962–7971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07962.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol AN, Obrietan K, Chen G, Belousov AB. Neuropeptide Y-mediated long-term depression of excitatory activity in suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:5883–5895. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05883.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol AN, Patrylo PR, Ghosh PK, Gao XB. Lateral hypothalamus early developmental expression and response to hypocretin (orexin) Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;433:349–363. doi: 10.1002/cne.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viale A, Kerdelhue B, Nahon JL. 17 beta-estradiol regulation of melanin-concentrating hormone and neuropeptide-E-I contents in cynomolgus monkeys: a preliminary study. Peptides. 1999;20:553–559. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana F, Hille B. Modulation of high voltage-activated calcium channels by somatostatin in acutely isolated rat amygdaloid neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:6000–6011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06000.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenbroek RE, Ahlijanian MK, Catterall WA. Clustering of L-type Ca2+ channels at the base of major dendrites in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1990;347:281–284. doi: 10.1038/347281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenbroek RE, Hell JW, Warner C, Dubel SJ, Snutch TP, Catterall WA. Biochemical properties and subcellular distribution of an N-type calcium channel alpha 1 subunit. Neuron. 1992;9:1099–1115. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90069-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenbroek RE, Sakurai T, Elliott EM, Hell JW, Starr TV, Snutch TP, Catterall WA. Immunochemical identification and subcellular distribution of the alpha 1A subunits of brain calcium channels. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;10:6403–6418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06403.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DB, Randall A, Tsien RW. Roles of N-type and Q-type Ca2+ channels in supporting hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science. 1994;264:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.7832825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilhofer HU, Muller TH, Swandulla D. Calcium channel types contributing to excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission between individual hypothalamic neurons. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;432:248–257. doi: 10.1007/s004240050131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]