Abstract

The effects of the cholinergic muscarinic agonist carbachol (CCh) on the basal L-type calcium current, ICa,L, in ferret right ventricular (RV) myocytes were studied using whole cell patch clamp. CCh produced two major effects: (i) in all myocytes, extracellular application of CCh inhibited ICa,L in a reversible concentration-dependent manner; and (ii) in many (but not all) myocytes, upon washout CCh produced a significant transient stimulation of ICa,L (‘rebound stimulation’). Inhibitory effects could be observed at 1 × 10−10m CCh. The mean steady-state inhibitory concentration-response relationship was shallow and could be described with a single Hill equation (maximum inhibition = 34.5 %, IC50 = 4 × 10−8m, Hill coefficient n = 0.60). Steady-state inhibition (1 or 10 μM CCh) had no significant effect on ICa,L selectivity or macroscopic (i) activation characteristics, (ii) inactivation kinetics, (iii) steady-state inactivation or (iv) kinetics of recovery from inactivation. Maximal inhibition of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity (preincubation of myocytes in 1 mm l-NMMA (NG-monomethyl-l-arginine) + 1 mm l-NNA (NG-nitro-l-arginine) for 2–3 h plus inclusion of 1 mm l-NMMA + 1 mm l-NNA in the patch pipette solution) produced no significant attenuation of the CCh-mediated inhibition of ICa,L. Protocols involving (i) the nitric oxide (NO) scavenger PTIO (2-phenyl-4,4,5,5,-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide; 200 μM), (ii) imposition of a ‘cGMP clamp’ (100 μM 8-Bromo-cGMP), and (iii) inhibition of soluble guanylyl cyclase (ODQ (1H-[1,2,4,]oxadiazolo(4,3,-a)quinoxalin-1-one), 50 μM) all failed to attenuate CCh-mediated inhibition of Ica,L. While CCh consistently inhibited basal ICa,L in all RV myocytes studied, not all myocytes displayed rebound stimulation upon CCh washout. However, there was no difference between CCh-mediated inhibition of ICa,L between these two RV myocyte types, and in myocytes displaying rebound stimulation neither ODQ nor 8-Bromo-cGMP (8-Br-cGMP) altered the effect. We conclude that NO production, activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase, or changes in intracellular cGMP levels are not obligatorily involved in muscarinic-mediated modulation of basal ICa,L in ferret RV myocytes.

The systemic effects of cholinergic modulation of whole heart function have been well-characterized (Levy & Schwartz, 1994; Opie, 1998). However, there is still considerable uncertainty over the specific molecular mechanisms by which acetylcholine (ACh) and other muscarinic agonists, such as carbachol (CCh), exert their modulatory effects upon cardiac muscle ion channels (Hartzell, 1988; Campbell & Strauss, 1995; Balligand et al. 2000). Depending upon specific cardiac myocyte type, muscarinic agonists can exert one, or a combination, of the following effects: (i) inhibition of the hyperpolarization-activated non-specific cation current IF (primary pacemaking cells); (ii) activation of an inwardly-rectifying K+ current IK,ACh; and/or (iii) inhibition of the L-type Ca2+ current ICa,L (reviewed in Hartzell, 1988; Campbell & Strauss, 1995; Ackerman & Clapham, 2000; DiFranceso et al. 2000; Parker & Fedida, 2001)

In sinoatrial node and atrio-ventricular myocytes evidence has been presented indicating that cholinergic-mediated inhibition of ICa,L is obligatorily coupled to the production of nitric oxide (NO) by Type III NO synthase (eNOS), leading to increased soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) activity (Hobbs, 1997; Wedel & Garbers, 2001) and subsequent activation of a cyclic-guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-dependent regulatory cascade (Han et al. 1995, 1996, 1998b). Subsequent studies on myocytes isolated from the hearts of transgenic mice lacking eNOS led Han et al. (1998a) to conclude that cholinergic modulation of ventricular ICa,L was also obligatorily dependent upon NO production. However, two independent studies (Vandecasteele et al. 1999; Belevych & Harvey, 2000) concluded that muscarinic inhibition of ICa,L still existed in mouse ventricular myocytes lacking eNOS. These conflicting results raise questions about the ‘obligatory NO production hypothesis’. Recent results from other laboratories have also raised doubts about the involvement of NO production in cholinergic-mediated modulation of various cardiac myocyte ion channel types (e.g. Méry et al. 1996; Zacharov et al. 1996; Gallo et al. 1998; Vandecasteele et al. 1998; Gödecke et al. 2001).

In both human and ferret ventricles there is a significant expression gradient of both eNOS and sGC protein across the left ventricular (LV) wall, with both enzymes being highly expressed in LV subepicardium but markedly reduced to absent in LV subendocardium (Brahmajothi & Campbell, 1999, 2001). Hence, there may be significant differences in NO- and muscarinic-mediated mechanisms of ion channel modulation not only between pacemaking (e.g. Han et al. 1995, 1996, 1998b) versus working (e.g. Vandecasteele et al. 1999; Belevych & Harvey, 2000) cardiac myocytes but also between myocytes located in distinct anatomical regions of the ventricle. Therefore, at present the exact role of myocyte NO production in indirect cholinergic-mediated inhibition of ICa,L in different working ventricular myocyte types is unclear.

In addition to inhibition, recent studies have indicated that in some working cardiac myocyte types ICa,L can display a significant rebound stimulation upon washout of muscarinic agonists (e.g. cat atrial myocytes: Wang & Lipsius, 1995; Wang et al. 1998; mouse and guinea pig ventricular myocytes: Belevych & Harvey, 2000; Belevych et al. 2001). However, arguments both for (Wang et al. 1998) and against (Belevych & Harvey, 2000) the obligatory involvement of NO production in generation of the rebound stimulation have been presented.

To begin to address these issues in one specific working ventricular myocyte type we have analysed the effects of the cholinergic agonist carbachol (CCh) on the basal ICa,L (i.e. in the absence of any previous β-adrenergic stimulation) in ferret right ventricular (RV) myocytes. We chose to work on basal ICa,L in these myocytes for two main reasons: (i) CCh significantly inhibits basal ICa,L, thereby precluding pretreatment with β-agonists (and, hence, any potential complications associated with such treatment); and (ii) the majority of ferret RV myocytes express both eNOS and sGC proteins (Brahmajothi & Campbell, 1999, 2001). Thus, all of the putative components hypothesized to be involved in the obligatory NO production hypothesis are present within these myocytes, and muscarinic responses can be studied under simple basal conditions. We therefore specifically focused on the following question: are RV myocyte NO production, activation of sGC, and/or changes in intracellular cGMP levels obligatorily involved in muscarinic-mediated modulation of basal ICa,L?

A preliminary account of this work has appeared in abstract form (Bett & Campbell, 2001).

METHODS

Myocyte isolation

All animal protocols were conducted in accordance with NIH approved guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University at Buffalo, SUNY, USA (protocol number PGY16010N). Single myocytes were isolated exactly as previously described (Qu et al. 1993a,b; Campbell et al. 1996; Brahmajothi et al. 1999; Brahmajothi & Campbell, 1999). Briefly, male ferrets (10-16 weeks old) were injected i.p. with 35 mg kg−1 sodium pentobarbital. Upon attainment of deep stage 3 anaesthesia (monitored by foot pad reflex) the heart was removed and mounted on a Langendorff apparatus. The heart was then perfused with low [Ca2+]o enzyme solution (collagenase Type II, (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ, USA), pronase type XIV and elastase type I-A (Sigma Chemical Company, St Louis, MO, USA)). After 10-20 min of perfusion the right ventricle (middle one-third region; Brahmajothi et al. 1999) was dissected free, placed in fresh enzyme solution, and gently rocked at 37 °C to obtain single myocytes After isolation, myocytes were immediately stored (20-22 °C) in control (Na+- and Ca 2+-containing) solution (mm): 144 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 MgSO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, pH = 7.40. All measurements were conducted at 20-22 °C and within 10-12 h of myocyte isolation.

Recording conditions, solutions, and analysis

Recording techniques and equipment were exactly as previously described (Campbell et al. 1996) with the following slight exception: voltage clamp pulses were generated either using a custom-built optically isolated pulse generator (Campbell et al. 1996) or under direct personal computer control using pCLAMP 8.0 software (Axon Instruments, Inc., Union City, CA, USA).

Gigaseals were initially formed in control Na+- and Ca2+-containing solution. After obtaining the whole-cell configuration (generally by dielectric rupture of the patch using a ‘zap’ circuit of the patch clamp amplifier (Axoclamp 2-B or 200-A; Axon Instruments)) myocytes were perfused with an extracellular Na+-and K+-free ICa,L solution (in mm): 144 N-methyl-d-glucamine Cl (NMDG-Cl), 5.4 CsCl, 1 MgSO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, pH = 7.40. Patch pipettes (2-4 MΩ, heat polished; TW150F, World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL, USA) contained (mm): 120 CsCl, 20 TEA-Cl, 1 MgSO4, 5 EGTA, 5 Mg-ATP, 5 Tris-creatine phosphate, 0.2 GTP, 10 Hepes, pH = 7.40. The use of these solutions isolated ICa,L from other overlapping currents (Na+, K+, Na+-Ca2+ exchanger), and allowed recording of stable ICa,L currents with minimal rundown for typical periods of 20-60 min (Qu et al. 1993a,b; Campbell et al. 1996). We wish to emphasize that due to the relatively slow perfusion rates used in these experiments (Campbell et al. 1996; Brahmajothi et al. 1999) no definitive quantitative conclusions could be reached on the kinetics of carbachol-mediated ‘on’ and ‘off’ responses. Therefore, only steady-state results were analysed.

After initial formation of the whole-cell configuration, myocytes were voltage clamped to a holding potential (HP) = -70 mV and an approximate 10 min period was allowed to pass for adequate internal perfusion and stabilization of current gating parameters (Marty & Neher, 1983). Currents (filtered at 1-2 kHz; digitized 5-10 kHz) were recorded on video tape (NR-10 digital data recorder, Instrutech Corporation, Long Island, NY, USA) and either directly digitized on-line or subsequently digitized off-line using pCLAMP software. Details of specific voltage clamp protocols are described in the appropriate figure captions. Unless otherwise indicated, the standard holding potential was HP = -70 mV and voltage clamp pulse protocols were applied at a frequency of 0.1-0.167 Hz. ‘Leakage correction’ was not applied, i.e. all illustrated currents are ‘raw’. Analysis of kinetics and fitting to mean data points was conducted using pCLAMP, Fig.P (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK), or Origin (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA) software. In the figures all data points are presented as means ± s.e.m..

All salts and associated compounds for isolating myocytes and making extracellular and intracellular recording solutions were obtained from Sigma. l-NMMA (NG-monomethyl-l-arginine), l-NNA (NG-monomethyl-l-arginine), ODQ (1H-[1,2,4,]oxadiazolo(4,3,-a)quinoxalin-1-one), 8-Br-cGMP, and PTIO (2-phenyl-4,4,5,5,-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide) were obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). ODQ and 8-Br-cGMP were aliquoted and stored as stock solutions at -20 °C until used. Stock solutions of PTIO were dissolved in ethanol and stored at -20 °C. Previous control measurements (Qu et al. 1993a,b; Campbell et al. 1996) indicated that the concentrations of ethanol present during final dilutions of PTIO had no significant effects on ICa,L.

RESULTS

Basic observations: inhibition of basal L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L) by carbachol and transient rebound stimulation upon washout

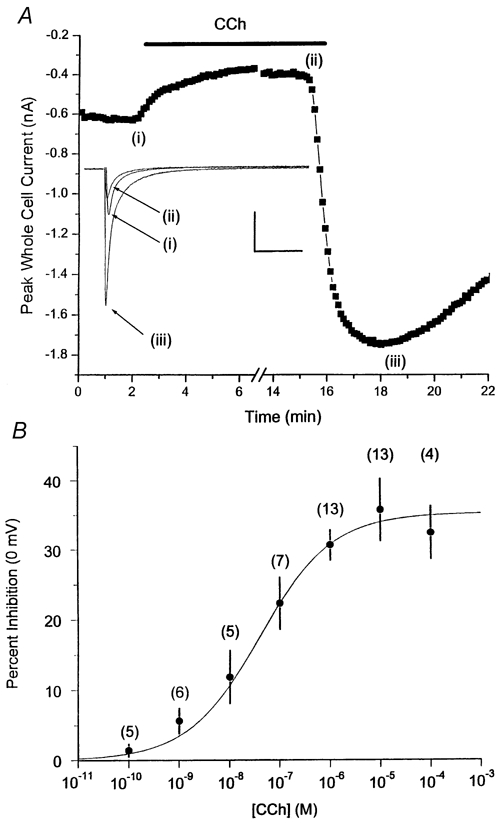

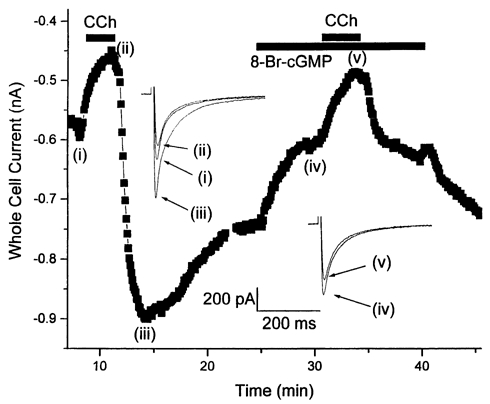

Carbachol (CCh) produced two significant effects upon basal ICa,L in ferret right ventricular (RV) myocytes. First, in all myocytes studied extracellular application of CCh (1-10 μM) inhibited ICa,L, in a reversible manner. This CCh-mediated inhibition typically reached a final steady-state level, and could be prevented by simultaneous application of 1 μM atropine (data not shown). Second, upon subsequent washout of CCh in many (but not all) myocytes there was a significant transient rebound stimulation of ICa,L followed by a slower return back to the basal level (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Effect of CCh on ICa,L recordings from RV myocytes.

A, basic observations: extracellular carbachol (CCh; 1 μM) inhibits basal ICa,L (0 mV) upon application (indicated by line) and, in many myocytes, produces rebound stimulation upon washout. Representative recordings from a single ferret right ventricular (RV) myocyte are shown. Each data point is the peak ICa,L elicited during a 500 ms voltage clamp step pulse to 0 mV from HP = -70 mV. Individual current traces for each condition are shown as indicated. Inset currents correspond to individual data points indicated by Roman numerals. Calibration bars: 500 pA, 200 ms. B, inhibitory CCh effects: concentration-response relationship. Steady-state percent inhibition of peak basal ICa,L is plotted as a function of extracellular CCh concentration. ICa,L was elicited during a 500 ms voltage clamp step pulse to 0 mV from HP = -70 mV. Each data point mean value was obtained from the indicated number of myocytes. See text for further methodological details. Mean data points were fitted to a single Hill equation with the following parameters: maximum inhibition (0 mV) = 34.5 %, IC50 = 4 × 10−8m, Hill coefficient n = 0.60.

Inhibitory CCh effects

Since the inhibition of basal ICa,L by CCh reached steady-state levels, it was possible to conduct both kinetic and steady-state analyses.

Concentration-response relationship

We first determined the concentration-response relationship for inhibition of peak ICa,L elicited at 0 mV. We did not observe any significant desensitization over the time courses of our measurements. Nonetheless, to minimize any complications due to desensitization, only two consecutive applications of CCh (the first always at a lower concentration) were applied to any one myocyte. We observed inhibitory effects beginning at 10−10m CCh, and saturating inhibition at ∼10 μM. Hence, the overall concentration-response relationship was shallow, covering an ∼100 000-fold CCh concentration range (Fig. 1B). The mean concentration- response data could be described by a single Hill equation with the following parameters: maximum ICa,L inhibition (0 mV) = 34.5 %, IC50 = 4 × 10−8m, Hill coefficient n = 0.60.

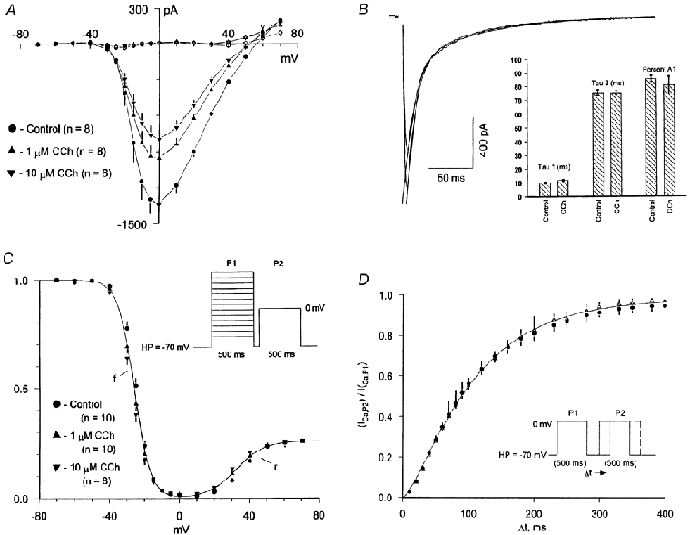

Current-voltage (ICa,L-V) relationship

The effects of CCh on the peak ICa,L-V relationship were next determined. CCh scaled down the peak ICa,L-V without producing any significant effects on activation threshold (≈-30 mV), peak current potential (0 mV), or apparent reversal potential Erev (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Effects of CCh on ICa,L macroscopic gating characteristics.

A, I-V relationship: steady-state inhibitory effects of 1 and 10 μM CCh on the basal ICa,L peak current-voltage (I-V) relationship (500 ms clamp pulses, HP = -70 mV, 0.167 Hz; filled symbols) and the net current remaining at 500 ms (open symbols). B,C, inactivation: kinetic and steady -state effects. B, effect of CCh on macroscopic inactivation kinetics of ICa,L recorded at 0 mV. Representative biexponential fits to inactivation are shown for both control and 1 μM CCh with the following parameters: control, τ1 = 9.4 ms, τ2 = 78.2 ms, ratio of initial amplitudes A1/(A1 + A2) = 0.891; 1 μM CCh, τ1 = 11.4 ms, τ2 = 78.2ms, ratio of initial amplitudes A1/(A1 + A2) = 0.832. The bar graph inset compares the mean (± s.e.m.) values of τ1, τ2, and the percent initial A1 amplitude under control conditions and after adding 1 μM CCh. C, steady-state inactivation relationship measured using a paired double pulse protocol (schematic inset; pulse protocol frequency 0.167 Hz). Individual data points are mean values of n indicated myocytes both under control conditions (circles) and after application of 1 μM (triangles) and 10 μM (inverted triangles) CCh. D, recovery kinetics. Mean recovery kinetics at HP = -70 mV were measured first under control conditions and then after application of 1 μM CCh. Paired double pulse recovery protocol is illustrated in the schematic inset, the frequency of protocol was 0.167 Hz. Individual data points are mean (± s.e.m.) values obtained from paired measurements made in n = 5 myocytes.

Inactivation: kinetic and steady-state effects

CCh had no significant effects on the macroscopic biexponential inactivation kinetics of ICa,L recorded at 0 mV (Fig. 2B). Mean values (n = 10 myocytes) were as follows: τ1: control 9.9 ± 0.6 ms, CCh 11.7 ± 0.6 ms; τ2: control, 75.3 ± 2.0 ms, CCh 75.2 ± 1.4 ms; and ratio of initial amplitudes A1/(A1 + A2): control, 0.853 ± 0.023, CCh 0.806 ± 0.066. None of these values were significantly different (paired t test, P > 0.05). To determine whether a hyperpolarizing shift in steady-state inactivation was involved, the steady-state inactivation relationship was determined first under control conditions and then after application of 1 or 10 μM CCh (paired double pulse protocol; see schematic inset in Fig. 2C). All three mean data sets could be fitted to the sum of the same two Boltzmann relationships ‘f’ + ‘r’ (parameters: f, V1/2 = -26 mV, slope factor k = -4.7 mV; r, V1/2 = +32 mV, k = 8 mV, Amax = 0.26).

Recovery

To determine whether a slowing in the kinetics of recovery from inactivation was contributing to the inhibitory effects, recovery kinetics (HP = -70 mV) were determined in the same myocyte first under control conditions and then after application of 1 μM CCh (paired double pulse protocol; see schematic inset in Fig. 2D). CCh had no effect on ICa,L recovery kinetics (control τrec,-70 mV = 91 ± 5 ms; CCh τrec,-70 mV = 93 ± 7 ms; n = 5). The overall mean recovery data for both conditions could be well-described by the same sigmoidal exponential relationship (ICa,LP2/ICa,LP1) = (1 – exp-[t/τ])n with the following parameters: τ = 92 ms, n = 1.45.

Obligatory involvement of NO in the inhibitory response?

To determine whether CCh-mediated inhibition of basal ICa,L was obligatorily dependent upon myocyte NO production, we next conducted a series of experiments designed to either (i) prevent/minimize NO production or (ii) minimize indirect NO-related effects produced through activation of sGC and subsequent increases in intracellular cGMP.

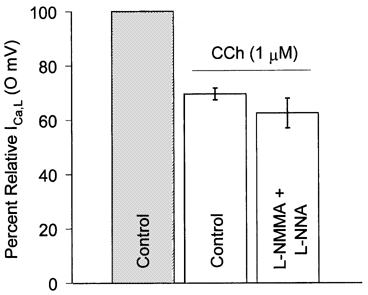

NOS inhibitors

To inhibit or minimize potential NOS activity (Brahmajothi & Campbell, 1999) myocytes were first preincubated for 2-3 h in 1 mm l-NMMA + 1 mm l-NNA, and 1 mm l-NNMA + 1 mm l-NNA was also included in both the patch pipette solution and the extracellular ICa,L recording solution. Under these putative maximally NOS-inhibited conditions, 1 μM CCh inhibited ICa,L (0 mV) by 37.6 ± 5.5 % (n = 5; Fig. 3). The fact that the mean percentage magnitude of the CCh-mediated inhibition was the same in both control ICa,L solution and in the presence of l-NMMA + l-NNA strongly argues against previous suggestions that such NOS inhibitors are acting as muscarinic receptor antagonists (e.g. Buxton et al. 1993).

Figure 3. NOS inhibition.

Mean effects of generalized NOS inhibition (1 mm l-NMMA + 1 mm l-NNA; see text for methodological details) on CCh-mediated (1 μM) inhibition of ICa,L (500 ms voltage clamp pulse to 0 mV, HP = -70 mV, 0.167 Hz). Mean (± s.e.m.) data were obtained from n = 13 myocytes (control, mean values from Fig. 2) and n = 5 myocytes (l-NMMA + l-NNA).

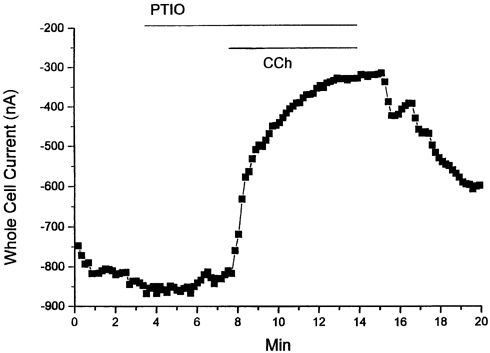

NO scavenger

In an attempt to minimize indirect NO-related effects (Campbell et al. 1996), in a parallel series of experiments we determined the effects of the NO-scavenger compound PTIO (2-phenyl-4,4,5,5,-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxy-3-oxide). PTIO stoichiometrically reacts with NO (PTIO/NO = 1, rate constant ∼104m−1 s−1) without altering NOS activity (e.g. Akaike et al. 1993). Extracellular application of PTIO (200 μM) alone either produced no effect (n = 4/7 myocytes) or resulted in a stimulation of basal ICa,L (10.9 ± 3.7 %; n = 3/7 myocytes). However, regardless of initial effects in the presence of PTIO, application of CCh (5 μM) inhibited ICa,L (0 mV) by 46.7 ± 5.4 % (n = 7; Fig. 4).

Figure 4. NO scavenger PTIO does not inhibit CCh-mediated inhibition of ICa,L.

Representative effects of PTIO (200 μM) on CCh-mediated inhibition of ICa,L (500 ms voltage clamp pulse to 0 mV, HP = -70 mV). In the continued presence of PTIO CCh (5 μM) still inhibited ICa,L.

‘cGMP-clamp’

To minimize alterations in intracellular cGMP levels a ‘cGMP-clamp’ protocol was applied. This was achieved by continual perfusion of the membrane permeant cGMP-analogue 8-Br-cGMP (100 μM). Extracellular application of 8-Br-cGMP alone resulted in a decrease in basal ICa,L elicited at 0 mV (25.7 ± 3.3 %; n = 6). However, in a series of double application experiments where 1 μM CCh was first applied and then washed out to determine control percentage inhibition, subsequent reapplication of 1 μM CCh during a simultaneous cGMP-clamp still resulted in additional inhibition of ICa,L (control CCh application, 23.9 ± 3.1 %; second CCh application during cGMP-clamp, 25.4 ± 3.8 %; n = 5; Fig. 5).

Figure 5. ‘cGMP clamp’.

Representative results from a RV myocyte first exposed to CCh (10 μM) and then 8-Br-cGMP (100 μM) + CCh (10 μM). While 8-Br-cGMP inhibited ICa,L it did not significantly alter the percentage magnitude of the CCh-mediated inhibitory response. Gaps in the data points correspond to periods during which I-V relationships were determined. Here and in Fig. 6, inset currents correspond to individual data points indicated by Roman numerals.

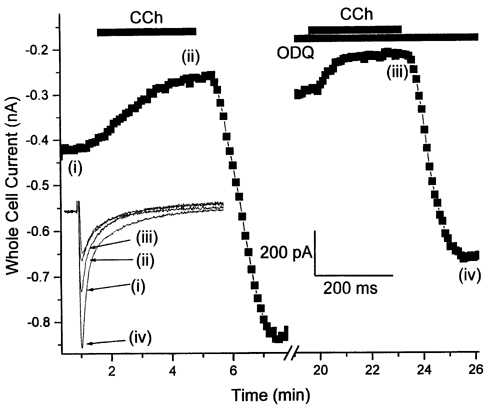

sGC inhibition

To prevent or minimize activation of sGC the effects of the putatively specific sGC inhibitor ODQ (1H-[1,2,4,]oxadiazolo(4,3,-a)quinoxalin-1-one; Garthwaite et al. 1995) were next determined. In our hands, extracellular application of 20-80 μM ODQ alone produced variable effects upon basal ICa,L, increasing it in some myocytes, decreasing it in others, and producing no effect in others. Due to this variability we have not attempted to further analyse these basal ODQ effects. However, in paired CCh application experiments (first application of 10 μM CCh to determine control inhibitory response, second application in the presence of 50 μM ODQ) ODQ failed to significantly attenuate the CCh-mediated inhibition of ICa,L (control CCh, 43.2 ± 4.2 %; CCh + ODQ, 44.3 ± 5.2 %; n = 7; Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Soluble guanylyl cyclase inhibition by ODQ.

As noted in the text, ODQ produced variable effects on basal ICa,L. However, regardless of initial effects, under steady-state conditions ODQ (50 μM) failed to attenuate the CCh-mediated inhibition of ICa,L elicited at 0 mV.

Transient stimulatory effects produced upon CCh washout (‘rebound stimulation’)

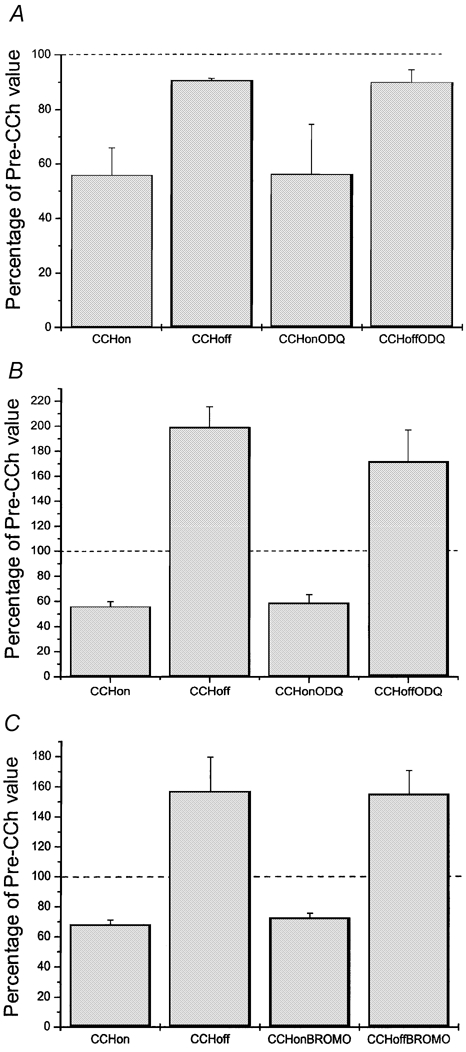

In many but not all myocytes a transient stimulation of ICa,L was observed upon CCh washout (Fig. 1A). We therefore conducted a series of experiments designed to determine (i) if there were differences in the effects of ODQ and 8-Br-cGMP among myocytes displaying prominent rebound stimulation versus those that failed to, and (ii) if NO production was obligatorily involved in the stimulatory effect. Two successive applications of CCh (10 μM) were applied, the first to determine the extent of inhibition of ICa,L (0 mV) and whether a given myocyte displayed rebound stimulation, the second to determine the effect of CCh in the presence of either ODQ or 8-Br-cGMP. Myocytes displaying rebound stimulation were grouped and analysed as ‘overshoot control’, while myocytes lacking a rebound stimulation were grouped and analysed as ‘undershoot control’.

In myocytes lacking rebound stimulation, ODQ (50 μM) failed to produce any significant effect on the CCh-mediated inhibition (Fig. 7A; details in caption). Among myocytes displaying rebound stimulation neither ODQ (Fig. 7B) nor 8-Br-cGMP (100 μM; Fig. 7C) had any significant effect on the magnitude of the CCh-mediated inhibition or subsequent rebound stimulation produced upon washout.

Figure 7. ‘Undershoot’ and ‘overshoot’ controls.

See text for methodological details. Dashed lines in all panels correspond to mean initial basal ICa,L (defined as 100 %). Mean values were obtained from paired CCh (10 μM) application experiments: first application (‘CCh on’), CCh applied alone to determine whether a given myocyte displayed or lacked rebound stimulation upon washout (‘CCh off’); second application, CCh applied after pretreatment with and in the continual presence of either ODQ, (50 μM; ‘CCh on ODQ’) or 8-Br-cGMP (100 μM; ‘CCh on BROMO’). After steady-state inhibitory effects were reached CCh was washed off in the continual presence of ODQ (‘CCh off ODQ’) or 8-Br-cGMP (‘CCh off BROMO’). A, undershoot control: mean ODQ results from myocytes lacking rebound stimulation upon washout of first CCh application. ODQ had no significant effect upon inhibition or return to the new baseline level upon washout. B and C, overshoot control. B, mean ODQ effects on myocytes displaying a prominent rebound stimulation upon washout of first CCh application. ODQ had no significant effect on either inhibition or rebound stimulation. C, mean 8-Br-cGMP effects in myocytes displaying a prominent rebound stimulation. 8-Br-cGMP had no significant effect either upon inhibition or rebound stimulation. Mean values (± s.e.m.) obtained from n = 3 (A), n = 4 (B), and n = 10 (C) myocytes.

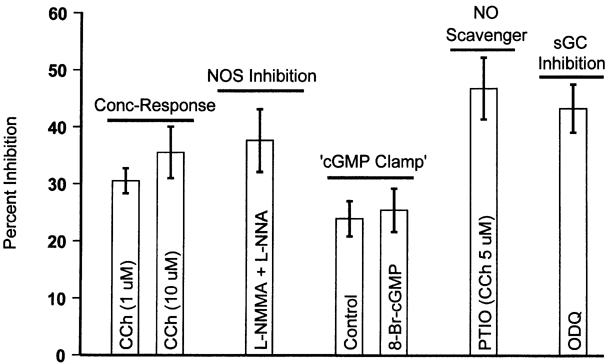

The mean results of all of experimental manoeuvres applied are summarized in Fig. 8.

Figure 8. Summary and comparison of results of experimental manoeuvres.

Mean percent inhibition of ferret basal RV myocyte ICa,L (elicited at 0 mV) by CCh under control conditions (concentration-response; Fig. 1A), putative maximal NOS inhibition (l-NNMA + l-NNA; Fig. 3), in the presence of NO scavenger (PTIO; Fig. 4), ‘cGMP clamp’ conditions (Fig. 5), and after sGC inhibition (ODQ; Fig. 6).

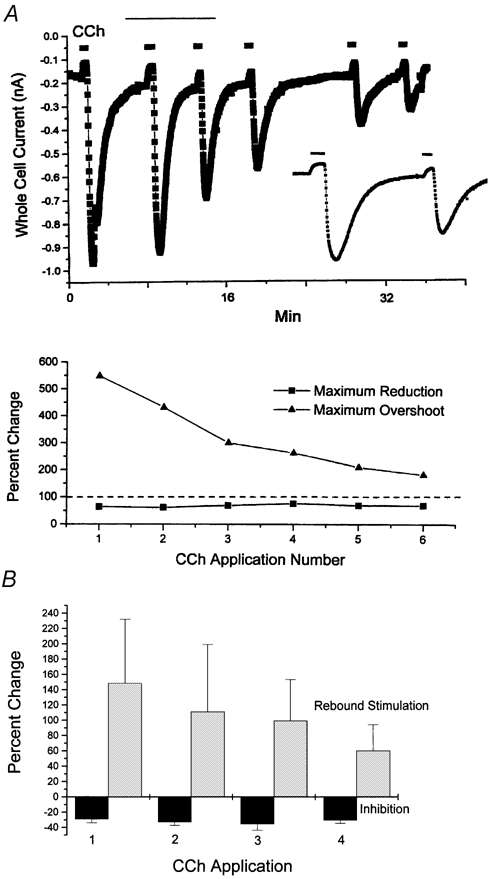

Novel observation: rebound stimulation progressively declines upon repeated CCh applications

In RV myocytes displaying rebound stimulation we frequently observed that upon repeated applications of CCh (10 μM) the degree of inhibition of ICa,L (elicited at 0 mV) remained constant while the amplitude of rebound stimulation progressively declined. An example of this behaviour is illustrated in Fig. 9A. Mean data pooled from n = 4.6 myocytes in which at least 3 successive application/wash-off cycles of CCh were applied are illustrated in Fig. 9B. For all myocytes studied under these conditions (n = 6 myocytes for 3 CCh applications, n = 4 myocytes for 4 CCh applications) mean inhibition remained essentially unchanged with repeated CCh applications (-29 ± 4.9 %, -32.8 ± 4.3 %, -35.2 ± 8.2 %, and -30.3 ± 4.1 % for CCh applications 1-4, respectively), while rebound stimulation progressively declined (+148 ± 84 %, +111 ± 88 %, +99 ± 54 %, and +60 ± 34 % for CCh applications 1-4, respectively).

Figure 9. Rebound stimulation declines with successive CCh applications while inhibition does not.

A, RV myocyte displaying rebound stimulation: representative differential responses of CCh-mediated effects on ICa,L (0 mV) elicited upon repeated CCh (10 μM) applications. The upper panel illustrates the time course of CCh-mediated inhibition and rebound stimulation during six consecutive CCh wash on/wash off cycles, while the lower panel illustrates the relative percentage change in both the inhibitory and rebound stimulatory effects. Note that both the baseline ICa,L and the magnitude of the CCh-mediated inhibition remained essentially constant, while the magnitude of the rebound stimulation progressively declined with each subsequent CCh application. For clearer illustration of these effects, the inset displays on an expanded scale the data indicated by the thin line over CCh application numbers 2 and 3. B, mean percentage inhibition and rebound stimulation produced during successive CCh application/wash-off cycles. Data pooled from n = 6 myocytes (3 CCh applications) and n = 4 myocytes (4 CCh applications). See text for further details.

DISCUSSION

Ferret right ventricular (RV) myocytes possess a cholinergic-activated ‘background’ K+ current IK,ACh (Ito et al. 1995; Boyett et al. 1988; D. L. Campbell, unpublished observations). However, under our recording conditions IK,ACh would have been eliminated. Similarly, since all kinetic measurements were conducted using pulses applied to 0 mV, and ECl was equal to -2.2 mV, the contribution of any Cl− current would have been virtually eliminated in these measurements. Finally, since CCh had no significant effect on either (i) the apparent ICa,L reversal potential (Campbell, et al. 1988) or (ii) the net current remaining at 500 ms the contribution of any type of Cl− current was minimal under our recording conditions. Our results therefore demonstrate that CCh inhibits basal ICa,L in ferret RV myocytes in a reversible, concentration-dependent manner. These inhibitory effects were manifested as a ‘scaling down’ of peak ICa,L amplitude without any effects on selectivity or macroscopic gating characteristics.

Inhibition could be observed at 10−10m CCh, suggesting that very low levels of cholinergic compounds could exert inhibitory effects upon RV myocyte function via inhibition of ICa,L. One caveat to this conclusion is the possibility that, since CCh is resistant to acetylcholine esterase, the responses we observed may be larger than those produced under physiological conditions. In addition, the relative importance of this inhibitory ICa,L pathway versus inhibition produced via muscarinic activation of IK,ACh awaits determination. Having stated these reservations, our conclusions on the lack of obligatory NO-, sGC-, and cGMP-involvement in CCh-mediated modulation of basal ICa,L in ferret RV myocytes are valid and have important physiological relevance.

One interesting feature of the concentration-response curve for CCh-mediated inhibition of basal ICa,L was its relative shallowness. Since we could observe a consistent CCh-mediated inhibition both over periods of several minutes of application and during multiple successive applications we believe that the shape of the inhibitory concentration-response curve is not reflective of a desensitization process. Whether multiple muscarinic receptor subtypes and/or multiple regulatory pathways are involved is presently unclear.

Under all of the experimental conditions which we applied (NOS inhibition, NO scavenging, cGMP clamp, sGC inhibition) CCh still inhibited basal ICa,L elicited at 0 mV to an extent similar to that observed under control conditions. While a negative result obtained from any one given pharmacological manoeuvre does not allow definitive rejection of the obligatory NO-hypothesis, the fact that all of the pharmacological manoeuvres which we applied failed to produce any significant effects on CCh-mediated inhibition of ICa,L is strong evidence against the hypothesis. We therefore conclude that muscarinic-mediated inhibition of ferret RV myocyte basal ICa, L is not obligatorily dependent upon NO production, alterations in sGC activity or changes in intracellular cGMP levels. This is in agreement with recent studies conducted on cat atrial (Wang et al. 1998) and mouse ventricular myocytes (Belevych & Harvey, 2000; Gödecke et al. 2001).

With regard to rebound stimulation, we observed two functional RV myocyte types: those displaying a prominent rebound stimulation, and those displaying little to no rebound stimulation. In both myocyte types we could find no compelling evidence in support of the obligatory NO production hypothesis. Furthermore, in myocytes displaying prominent rebound stimulation upon CCh washout, neither ODQ nor 8-Br-cGMP produced any significant effects. We therefore conclude that, while these two effects (inhibition, rebound stimulation) are clearly related through the common mechanism(s) of muscarinic receptor(s) activation, neither is obligatorily dependent upon endogenous myocyte NO production. Our conclusions are therefore in disagreement with those of Wang et al. (1998), but are in agreement with those of Belevych & Harvey (2000).

Using immunofluourescent localization (IF) we have previously demonstrated that Type III eNOS is present in the majority of ferret RV myocytes, while it is heterogeneously expressed across the wall of the left ventricle (LV), being high in LV subepicardial myocytes but low to absent in LV subendocardial myocytes (Brahmajothi & Campbell, 1999). We have now obtained additional IF data indicating that a virtually identical heterogeneous expression pattern exists in the ferret heart for NO-activated soluble guanylyl cyclase (i.e. high sGC expression in RV and LV subepicardial myocytes, low sGC expression in LV subendocardial myocytes; Brahmajothi & Campbell, 2001). Hence, there is a clear correlation between the expression of eNOS and sGC proteins among distinct anatomical regions of the ventricle. However, eNOS and sGC expression levels do not appear to simply correlate with functional CCh-mediated responses. While our results do not allow us to address the issue of NO and sGC involvement in CCh-mediated effects under β-adrenergically stimulated conditions, they do strongly indicate that there are NO-independent pathways linked to muscarinic receptor activation that can produce both inhibition and stimulation of RV ICa,L under basal conditions.

The fact that in some RV myocytes both PTIO (NO-scavenger) and ODQ (sGC inhibitor) caused a stimulation of ICa,L may indicate that endogenous eNOS activity may play a role in maintenance of basal ICa,L (e.g. Gallo et al. 1998). However, these stimulatory effects were not consistently observed. The hypothesis that eNOS activity may be modulating basal ICa,L amplitude in ferret RV myocytes therefore requires further experimentation. The fact that the inhibitory effects of CCh were somewhat greater in the presence of both PTIO and ODQ may be indicative of a modulatory role of basal NO production in these effects.

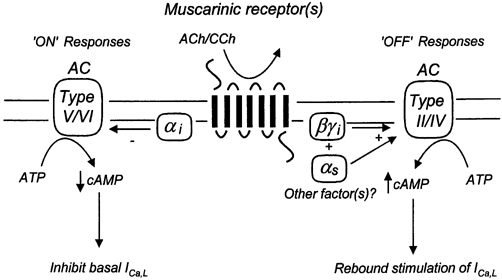

While our results indicate that NO- and sGC-activity are not obligatorily coupled to CCh-mediated effects on RV basal ICa,L, they in turn raise the obvious question: just what mechanisms are responsible? One possibility (and we wish to emphasize that at present the following model is only speculative) could be ‘cross talking’ interactions of activated G-protein subunits with multiple adenylyl cyclase (AC) isoforms (Tang & Gilman, 1991; Taussig & Gilman, 1995; Schulman & Hyman, 1999; Hanoune & Defer, 2001). For example, if either a Type V and/or Type VI AC isoform is active under basal conditions in ferret RV myocytes (Campbell et al. 1996), then CCh-mediated activation of M2-muscarinic receptors coupled to Gi would lead to release of activated αi and βγ subunits (Fig. 10). Activated αi would then inhibit basally active Type V/VI AC, thereby inhibiting basal ICa,L. Since in most cell types Gi is much more highly expressed than Gs, upon washout of CCh residually activated βγ subunits would transiently activate Type II and/or Type IV AC isoforms, thus producing a transient rebound stimulation. However, in the light of present models of G-protein interactions on AC isoforms, for this scenario to be viable an activated αs subunit would also have to be involved, i.e. both αs and βγ (released from Gi) subunits are believed to be required for activation of Type II/IV AC isoforms (Taussig & Gilman, 1995; Schulman & Hyman, 1999). The source of αs in ferret RV myocytes under basal conditions is unclear.

Figure 10. Speculation: involvement of multiple adenylyl cyclase (AC) isoforms?

One interpretative scenario for our results would be the proposal that ferret RV myocytes possess a basally active Type V and/or Type VI AC isoform which contributes to maintenance of basal ICa,L. Activation of muscarinic receptors (multiple subtypes?) coupled to inhibitory heterotrimeric Gi protein(s) would release αi and βγ subunits, leading to inhibition of Type V/VI AC activity and thus inhibition of basal ICa,L. Assuming Gi is more highly expressed than Gs, upon washout of muscarinic agents residually activated βγ subunits would transiently activate Type II and/or Type IV AC isoforms, thus producing a transient rebound stimulation. See text for further discussion.

An alternative to the above scenario would be that CCh-mediated effects under basal conditions may be independent of AC isoform activity. For example, a very recent study has indicated that cGMP can inhibit myocardial contractility in mice lacking cGMP-dependent protein kinase I (cGKI) both in the absence and presence of forskolin, an AC activator (Wegener et al. 2002). It was thus concluded that NO, cGMP, and cGKI are not obligatorily involved in CCh-mediated inhibition of murine myocardial contractility. If applicable to ferret RV myocytes, these results would argue against the ‘AC isoform scenario’ outlined above.

In RV myocytes displaying rebound stimulation we observed that upon repeated applications of CCh the degree of inhibition remained constant while the amplitude of rebound stimulation progressively declined with each successive CCh application (Fig. 9). Whether this represents a specific ‘rundown’ process of an intracellular regulatory factor(s) or some form of desensitization is unclear. Nonetheless, the fact that the two processes could be differentially modulated suggests involvement of multiple NO- and sGC-independent pathways and/or ‘crosstalk’ between regulatory pathways (Gallo et al. 1998; Belevych et al. 2001). This phenomenon may therefore provide an explanation for the discrepancy between our conclusions and those previously reached for cat atrial myocytes (Wang et al. 1995, 1998).

In conclusion, our results indicate that muscarinic modulation of basal ICa,L in ferret RV myocytes involves NO- and sGC-independent pathways and/or crosstalk between such pathways. To paraphrase Hare & Stamler (1999), in RV myocytes NO is not an obligatory mediator of muscarinic responses but is most likely to be a modulator of such responses under varying conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to D. L. Campbell from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL58913) and the American Heart Association (National Center, Established Investigator Award).

REFERENCES

- Ackerman MJ, Clapham DE. G proteins and ion channels. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside. 3. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 2000. pp. 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike T, Masaki Y, Miyamoto Y, Sato K, Kohno M, Sasamoto K, Miyazaki K, Ueda S, Maeda H. Antagonist action of imidazolineoxyl N-oxides against endothelium-derived relaxing factor/NO. through a radical reaction. Biochemistry. 1993;32:827–832. doi: 10.1021/bi00054a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balligand J-L, Feron O, Kelly RA. Role of nitric oxide in myocardial function. In: Ignarro LJ, editor. Nitric Oxide. Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 585–607. [Google Scholar]

- Belevych AE, Harvey RD. Muscarinic inhibitory and stimulatory regulation of the L-type Ca2+ current is not altered in cardiac ventricular myocytes from mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Journal of Physiology. 2000;528:279–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belevych AE, Sims C, Harvey RD. ACh-induced rebound stimulation of the L-type Ca2+ current in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes, mediated by G βγ-dependent activation of adenylyl cyclase. Journal of Physiology. 2001;536:677–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00677.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bett GCL, Campbell DL. Muscarinic modulation of the L-type calcium channel in ferret right ventricular myocytes. Biophysical Journal. 2001;80:635a. [Google Scholar]

- Boyett MR, Kirby MS, Orchard CH, Roberts A. The negative inotropic effect of acetylcholine on ferret ventricular myocardium. Journal of Physiology. 1988;404:613–635. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmajothi MV, Campbell DL. Heterogeneous basal expression of nitric oxide synthase and superoxide dismutase isoforms in mammalian heart. Implications for mechanisms governing indirect and direct nitric oxide-related effects. Circulation Research. 1999;85:575–587. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.7.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmajothi MV, Campbell DL. Heterogeneous basal expression of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC). in ferret ventricle. Biophysical Journal. 2001;80:647a. [Google Scholar]

- Brahmajothi MV, Campbell DL, Rasmusson RL, Morales MJ, Trimmer JS, Nerbonne JM, Strauss HC. Distinct transient outward potassium current (Ito) phenotypes and distribution of fast-inactivating potassium channel alpha subunits in ferret left ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:581–600. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton ILO, Cheek DJ, Eckman D, Westfal DP, Sanders KM, Keef KD. NG-nitro l-arginine methyl ester and other akyl esters of arginine are muscarinic receptor antagonists. Circulation Research. 1993;72:387–395. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DL, Giles WR, Hume JR, Noble D, Shibata EF. Reversal potential of the calcium current in bull-frog atrial myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1988;403:267–289. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DL, Stamler JS, Strauss HC. Redox modulation of L-type calcium channels in ferret ventricular myocytes. Dual mechanism regulation by nitric oxide and S-nitrosothiols. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;108:277–293. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.4.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DL, Strauss HC. Regulation of Ca2+ currents in the heart. In: Means AR, editor. Calcium Regulation and Cellular Function. New York: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 25–88. [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D, Moroni A, Baruscotti M, Accili EA. Cardiac pacemaker currents. In: Sperelakis N, Kurachi Y, Terzic A, Cohen MV, editors. Heart Physiology and Pathophysiology. 4. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 357–372. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo MP, Ghigo D, Bosta A, Alloatti G, Costamagna C, Penna C, Levy RC. Modulation of guinea-pig cardiac L-type calcium current by nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. Journal of Physiology. 1998;506:639–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.639bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite J, Southam E, Boulton CL, Nielsen EB, Schmidt K, Mayer B. Potent and selective inhibition of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase by 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3,-a]quionoxalin-1-one. Molecular Pharmacology. 1995;48:184–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gödecke A, Heinecke T, Kamkin A, Kiselva I, Strasser RH, Decking UK M, Stumpe T, Isenberg G, Schrader J. Inotropic response to β-adrenergic receptor stimulation and anti-adrenergic effect of ACh in endothelial NO-synthase-deficient mouse hearts. Journal of Physiology. 2001;532:195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0195g.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Cebidae I, Feron O, Opel DJ, Arstall MA, Zhao YY, Huang P, Fishman M, Michel T, Kelly RA. Muscarinic cholinergic modulation of cardiac myocyte ICa,L is absent in mice with targeted disruption of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998a;9:6510–6525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Kobzik L, Balligand JL, Kelly RA, Smith TW. Nitric oxide synthase (NOS3)-mediated cholinergic modulation of Ca2+ current in adult rabbit atrioventricular nodal cells. Circulation Research. 1996;78:998–1008. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.6.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Kobzik L, Stevenson D, Shimoni Y. Characteristics of nitric oxide-mediated cholinergic modulation of calcium current in rabbit sino-atrial node. Journal of Physiology. 1998b;509:741–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.741bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Shimoni Y, Giles WR. A cellular mechanism for nitric oxide-mediated cholinergic control of mammalian heart rate. Journal of General Physiology. 1995;106:45–65. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanoune J, Defer N. Regulation and role of adenylyl cyclase isoforms. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2001;41:145–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare JM, Stamler JS. NOS: modulator, not mediator of cardiac performance. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:273–274. doi: 10.1038/6486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell HC. Regulation of cardiac ion channels by catecholamines, acetylcholine and second messenger systems. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 1988;52:165–247. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(88)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs AJ. Soluble guanylate cyclase: the forgotten sibling. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1997;18:484–491. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Hosoya Y, Inanobe A, Tomoike H, Endoh M. Acetylcholine and adenosine activate the G-protein-gated muscarinic K+ channel in ferret ventricular myocytes. Naunyn-Schmiederberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1995;351:610–617. doi: 10.1007/BF00170160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy MN, Schwartz PJ. Vagal Control of the Heart: Experimental Basis and Clinical Implications. Armonk, New York: Futura Publishing Company, Inc.; 1994. p. 644. [Google Scholar]

- Marty A, Neher E. Tight-seal whole-cell recording. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single Channel Recording. 1. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Méry PF, Hove-Madsen L, Chesnais, Hartzell HC, Fischmeister R. Nitric oxide synthase does not participate in negative inotropic effect of acetylcholine in frog heart. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270:H1178–1188. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.4.H1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie LH. The Heart: Physiology, From Cell to Circulation. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. p. 637. [Google Scholar]

- Parker C, Fedida D. Cholinergic and adrenergic modulation of cardiac K+ channels. In: Archer SL, Rusch NJ, editors. Potassium Channels in Cardiovascular Biology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. pp. 387–426. [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Campbell DL, Strauss HC. Modulation of L-type Ca 2+ current by extracellular ATP in ferret isolated right ventricular myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1993a;471:295–317. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Campbell DL, Whorton AR, Strauss HC. Modulation of basal L-type Ca2+ current by adenosine in ferret isolated right ventricular myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1993b;471:269–293. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman H, Hyman SE. Intracellular signaling. In: Zigmond MJ, Bloom FE, Landis SC, Roberts JL, Squire LR, editors. Fundamental Neuroscience. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 269–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tang W-J, Gilman AG. Tissue-specific regulation of adenylyl cyclase by G-protein βγ subunits. Science. 1991;254:1500–1503. doi: 10.1126/science.1962211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taussig R, Gilman AG. Mammalian membrane-bound adenylyl cyclases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:1–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandecasteele G, Eschenhagen T, Fischmeister R. Role of the NO-cGMP pathway in the muscarinic regulation of the L-type Ca 2+ current in human atrial myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1998;506:653–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.653bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandecasteele G, Eschenhagen T, Scholz H, Stein B, Verde I, Fischmeister R. Muscarinic and beta-adrenergic regulation of heart-rate, force of contraction and calcium current is preserved in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:331–334. doi: 10.1038/6553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YG, Lipsius SL. Acetylcholine elicits a rebound stimulation of Ca2+ current mediated by pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein and cAMP-dependent protein kinase A in atrial myocytes. Circulation Research. 1995;76:634–644. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YG, Rechenmacher CE, Lipsius SL. Nitric oxide signaling mediates stimulation of L-type Ca2+ current elicited by withdrawal of acetylcholine in cat atrial myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:1130–125. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedel BJ, Garbers DL. The guanylyl cyclase family at Y2K. Annual Review of Physiology. 2001;63:215–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener JW, Nawrath H, Wolfsgruber W, Kuhbandner, Werner C, Hoffman F, Feil R. cGMP-dependent protein kinase I mediates the negative inotropic effect of cGMP in the murine myocardium. Circulation Research. 2002;90:18–20. doi: 10.1161/hh0102.103222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharov SL, Pieramici S, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR, Harvey RD. Nitric oxide synthase activity in guinea pig ventricular myocytes is not involved in muscarinic inhibition of cAMP-regulated ion channels. Circulation Research. 1996;78:925–935. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.5.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]