Abstract

Possible interactions between different intracellular Ca2+ release channels were studied in isolated rat gastric myocytes using agonist-evoked Ca2+ signals. Spontaneous, local Ca2+ transients were observed in fluo-4-loaded cells with linescan confocal imaging. These were blocked by ryanodine (100 μm) but not by the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) blocker, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (100 μm), identifying them as Ca2+ sparks. Caffeine (10 mm) and carbachol (10 μm) initiated Ca2+ release at sites which co-localized with each other and with any Ca2+ spark sites. In fura-2-loaded cells extracellular 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate and intracellular heparin (5 mg ml−1) both inhibited the global cytoplasmic [Ca2+] transient evoked by carbachol, confirming that it was IP3R-dependent. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate and heparin also increased the response to caffeine. This probably reflected an increased Ca2+ store content since 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate more than doubled the amplitude of transients evoked by ionomycin. Ryanodine completely abolished carbachol and caffeine responses but only reduced ionomycin transients by 30 %, suggesting that blockade of carbachol transients by ryanodine was not simply due to store depletion. Double labelling of IP3Rs and RyRs demonstrated extensive overlap in their distribution. These results suggest that carbachol stimulates Ca2+ release through co-operation between IP3Rs and RyRs, and implicate IP3Rs in the regulation of Ca2+ store content.

Muscle contraction is one of many cell functions regulated by cytoplasmic [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]c). Physiological agonists often stimulate release of stored Ca2+ by opening channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). These openings generate both local and global Ca2+ signals (Berridge, 1997; Cancela et al. 2000). It is well established that Ca2+ release may occur through a variety of SR channel types, of which those activated by the second messenger inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3Rs) and those sensitive to ryanodine (RyRs) have been longest studied. Investigations in smooth muscle suggest that agonist-induced IP3 production releases Ca2+ from a sub-compartment of the ryanodine-sensitive store (Itoh et al. 1992; Baro & Eisner, 1995; Flynn et al. 2001). This raises the question of whether the release events themselves are independent of one another, or interact in generating the [Ca2+]c responses seen. We have investigated this in rat gastric smooth muscle using carbachol, which stimulates Ca2+ release through IP3 production (Kobayashi et al. 1989; Berridge, 1993), and caffeine, which promotes activation of RyRs (Rousseau & Meissner, 1989). The Ca2+ release mechanisms involved have been characterized both spatially and pharmacologically, and the results obtained suggest that activation of IP3Rs by carbachol triggers the opening of RyRs. This supports the conclusion that co-operation between different SR channels can shape agonist-evoked Ca2+ signals, as previously reported for smooth muscle (Boittin et al. 1999; Gordienko, et al. 1999) and pancreatic acinar cells (Cancela et al. 2000). In addition, we present direct evidence that the Ca2+ store content in smooth muscle can be regulated by tonic IP3R activity. Some such release mechanism is required if the ability of the sarcoplasmic reticulum to act as a ‘buffer-barrier mechanism’ is to be maintained in the face of ongoing Ca2+ influx, since this would otherwise be expected to overload the store and limit further Ca2+ uptake (van Breemen et al. 1995; White & McGeown, 2000a).

Methods

Cell isolation and [Ca2+] measurement

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were anaesthetized with CO2 and killed by cervical dislocation, as approved under UK Home Office regulations. The antral region of the stomach was dissected out and myocytes were isolated enzymatically (White & McGeown, 2000a). Cells were loaded with the appropriate Ca2+ indicator by pre-incubation with the acetoxy-methyl (AM) ester (Molecular Probes) for 20 min at 37 °C, followed by a 20 min wash in dye-free solution, again at 37 °C. They were placed in an organ bath on an inverted microscope (Eclipse TE300 from Nikon (UK) with a × 60 oil immersion objective, NA1.4) and superfused with physiological solutions at 37 °C. Global [Ca2+]c was measured using fura-2 (loaded using 5 μm fura-2 AM; Molecular Probes) and a microfluorimeter (Photon Technology International Inc., Lawrenceville, NJ, US), as previously described in detail (White & McGeown, 2000a). Local changes in cytoplasmic [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]c) were imaged using fluo-4 (loaded using 10 μm fluo-4 AM, Molecular Probes) and a confocal scanning laser microscope (MR-A1, Bio-Rad) in linescan mode with an acquisition rate of 500 lines per second. The theoretical lateral image resolution (Rlat) was calculated to be approximately 0.2 μm using the equation Rlat = 0.61λ/NA, where λ is the peak emission wavelength and NA is the numerical aperture of the objective. Confocally imaged cells were treated with wortmannin (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent movement (Burdyga & Wray, 1998). Fluo-4 was excited at 488 nm and emitted light was filtered with a 530–560 nm bandpass filter. Data acquisition was controlled using Timecourse software (Bio-Rad). Images were analysed using Lasersharp (Bio-Rad) and further processed using Scion Image graphical software (shareware; Scion Corporation, USA). Fluorescence images (F) have usually been normalized to the resting fluorescence (F0) in control images recorded at the beginning of the experiment.

For experiments which required intracellular application of heparin, cells were voltage clamped using the whole-cell patch clamp technique, as described previously (White & McGeown, 2000a).

Receptor labelling

Myocytes were fixed and permeabilized using methanol and acetone at −18 °C. After washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cells were incubated for 24 h at 4 °C with polyclonal anti-IP3R antibody (1:100 dilution; Calbiochem UK). The secondary antibody was green-fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:100 dilution; Molecular Probes) applied for 1 h at room temperature. RyRs were then labelled by incubating the same cells for a further hour (room temperature) in 1 μm orange-fluorescent-labelled ryanodine (BODIPY TR-X ryanodine, Molecular Probes; see Gordienko et al. 2001). Double labelled cells were imaged sequentially using 488 nm excitation and a 530/560 nm bandpass emission filter for the green IP3R label, followed by 514 nm excitation with a 600 nm longpass emission filter for the orange RyR label. Control experiments on single labelled cells demonstrated that the two signals were adequately separated using these wavelengths.

Solutions and drugs

The bath solution had the following composition (mm): NaCl 125, KCl 5.36, glucose 10, sucrose 2.9, NaHCO3 4.17, KH2PO4 0.44, Na2HPO4 0.33, MgCl2 0.5, CaCl2 1.8, MgSO4 0.4, Hepes 10, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. In Ca2+-free solutions MgCl2 was substituted for CaCl2 and EGTA (5 mm) was included. CaCl2 was raised to 3 mm for linescan experiments. The whole-cell pipette solution was composed of (mm): KCl 53, potassium gluconate 80, MgCl2 1.0, Na2ATP 1.0, NaGTP 0.1, phosphocreatine 2.5, EGTA 0.5, Hepes 10, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. Ionomycin was initially dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), and ryanodine in 50 % ethanol, to give 10−2m stock solutions. DMSO and ethanol alone had no effects at the concentrations used (0.001-0.05 % v/v). All drugs were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich with the exception of Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent probes (Molecular Probes).

Analysis and statistics

Data have been summarized as the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Differences between means were accepted as statistically significant at the 95 % significance level, as assessed using Student's paired t test.

Results

Visualization of spontaneous and evoked Ca2+ release

Spontaneous Ca2+ release events were seen in cells loaded with fluo-4 and imaged confocally in linescan mode. Although these were seen in physiological [Ca2+]o, they were routinely observed with external [Ca2+] raised to 3 mm (Fig. 1, spatio-temporal characteristics summarized in Table 1). It seemed likely that these were Ca2+ sparks which are believed to reflect localized release through clusters of ryanodine receptors (Nelson et al. 1995; Gordienko et al. 1998; Jaggar et al. 2000; Kirber et al. 2001). This was confirmed by the observation that spontaneous release was blocked by ryanodine (100 μm, Fig. 1A; similar responses seen in five cells). The increase in background fluorescence in the presence of ryanodine suggests an increase in mean cytoplasmic [Ca2+]c, and this was confirmed in experiments in which fura-2 was used to estimate global [Ca2+]c (see Fig. 5 below). In contrast with ryanodine however, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (100 μm), a cell permeant and reversible inhibitor of IP3R opening (Maruyama et al. 1997), failed to block spark activity in four cells (Fig. 1B). This was consistent with our conclusion that these spontaneous Ca2+ transients were dependent on RyR rather than IP3R activity.

Figure 1. Spontaneous Ca2+ release events in a fluo-4-loaded myocyte.

Fluo-4 fluorescence was recorded from the scanline indicated on the cell outline to the right of the top panel and normalized to initial, control fluorescence levels (F/F0, see colour code). Distance is plotted vertically and time horizontally. A, images from a cell showing spontaneous, localized Ca2+ transients were seen in 3 mm external [Ca2+] (upper panel). These were completely blocked following 2 min exposure to ryanodine (100 μm, lower panel). B, images from a different cell showing spontaneous Ca2+ transient activity under control conditions (3 mm external Ca2+, upper panel) and in the presence of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (100 μm for 2 min, lower panel).

Table 1.

Characteristics of spontaneous Ca2+ release events

| Amplitude (Δ F/F0) | FWHM (μm) | FTHM (ms) | Rise time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.70 ± 0.08 | 2.20 ± 0.11 | 43.0 ± 2.2 | 20.0 ± 1.3 |

Localized spontaneous [Ca2+]i transients were observed in cells loaded with fluo-4 and exposed to 3 mM external Ca2+ using confocal microscopy in linescan mode. Mean values (±s.e.m.) are given for peak amplitude (ΔF/F0), spread (full width at half maximal amplitude; FWHM), duration (full time from half maximal amplitude; FWHM), duration (full time from half maximum to half maximum; FTHM) and rise time to peak for 45 events recorded from 6 cells.

Figure 5. Effects of ryanodine on store release by carbachol and caffeine.

Evoked [Ca2+]c responses in a fura-2-loaded myocyte before and during application of ryanodine (100 μm).

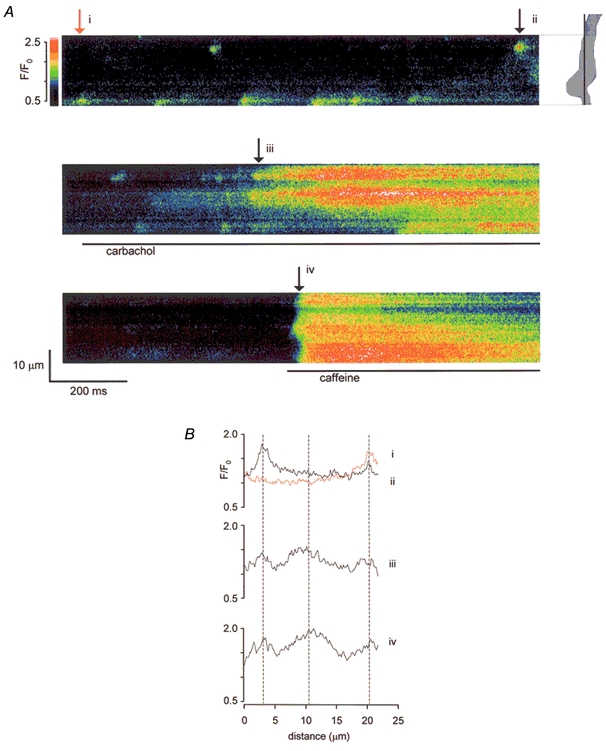

When carbachol (10 μm in zero Ca2+ solution) was applied to cells, the resulting increase in [Ca2+]c was initiated from distinct sites. These coincided with any regions of spontaneous spark activity, although additional release sites were also recruited (Fig. 2A). When caffeine (10 mm in zero Ca2+ solution) was added in turn to the same cell, it always initiated release from the same sites as carbachol, although the response was more rapid. Plots of fluorescence intensity against distance along the scanline at selected time points illustrate clearly that the release sites first activated by carbachol and caffeine were located close to each other and to Ca2+ spark sites (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained in five cells tested.

Figure 2. Comparison of Ca2+ spark sites with carbachol and caffeine-sensitive release sites in a single myocyte.

A, normalized fluo-4 fluorescence (F/F0, see colour code) was recorded from the scanline indicated on the cell outline. Spontaneous Ca2+ sparks were seen (top panel). Applications of carbachol (10 μm in zero Ca2+, middle panel) and caffeine (10 mm in zero Ca2+, bottom panel) were separated by a wash period (100 s) to allow store refilling. B, F/F0 plotted against distance along the scanline at four time points (i-iv in A). Early responses to carbachol (middle graph) and caffeine (bottom graph) correspond closely in position. Peripheral peaks also correspond to the Ca2+ spark sites (top graph).

Pharmacology of carbachol- and caffeine-evoked responses

The observation that carbachol and caffeine initiated Ca2+ release at the same sites within the cell suggested that IP3-activated Ca2+ signals may be amplified by RyR-mediated release. We tested this pharmacologically using fura-2 and microfluorimetry to quantitatively assess changes in [Ca2+]c. Application of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (100 μm) decreased basal [Ca2+]c from 120 ± 19 nm under control conditions to 63 ± 11 nm in the presence of the drug (P < 0.05, n = 7). The global [Ca2+]c response to carbachol was also completely blocked, as demonstrated by a trace from one such experiment (Fig. 3). In seven cells, carbachol produced a mean rise of 70 ± 14 nm under control conditions, but there was always a small decrease in [Ca2+]c when carbachol was applied in the presence of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, reflecting the switch to a zero Ca2+ solution during drug application. Caffeine responses, on the other hand, were increased from 80 ± 18 nm under control conditions to 142 ± 32 nm in the presence of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (P < 0.005, n = 7). The slowly developing [Ca2+]c transient seen after washout of carbachol in the example shown was observed in six out of seven cells tested and a similar rise was also seen after caffeine washout in four of these cells. Such washout responses were never seen when agonists were applied in normal Ca2+ solutions, suggesting that they required exposure to external Ca2+ after store depletion in Ca2+-free conditions.

Figure 3. Effects of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate on store release by carbachol and caffeine.

2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2APB, 100 μm) inhibited the global [Ca2+]c response to carbachol (cch, 10 μm in zero Ca2+) but enhanced the caffeine (caff, 10 mm in zero Ca2+) response in a myocyte loaded with fura-2.

Similar results were obtained when heparin was used as a competitive IP3R blocker (Ehrlich et al. 1994). Since heparin is cell impermeant, it was allowed to diffuse into the cell from the patch-pipette solution (5 mg ml−1) under voltage-clamp conditions at a holding potential of −60 mV. Control responses to carbachol or caffeine were recorded immediately after rupture of the cell membrane under the patch electrode, i.e. before there was time for appreciable dialysis of heparin (Fig. 4). The agonists were then re-applied three times at approximately 100 s intervals. After 5 min, the carbachol response was reduced to 21 ± 6 % of control (P < 0.01, n = 5, Fig. 4A). When an identical protocol was used but heparin was omitted from the pipette solution, carbachol responses were unaffected, the mean transient size being 115 ± 9 % of the initial response after 5 min (n.s., n = 6, data not shown). In a further series of cells, dialysis with heparin increased the caffeine response to 177 ± 25 % of control after 5 min (P < 0.05, n = 7, Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Effects of heparin on store release by carbachol and caffeine.

Heparin was dialysed into fura-2-loaded myocytes from a patch electrode (5 mg ml−1 in pipette solution). Cells were exposed to either carbachol (cch, 10 μm, record A) or caffeine (caff, 10 mm, record B) immediately after rupture of the membrane subjacent to the patch pipette and at approximately 100 s intervals thereafter. C, summary of the mean amplitude (± s.e.m.) of carbachol- (○) and caffeine (•)-dependent transients, normalized to the initial evoked transient in each case. The [Ca2+]c response evoked by carbachol was inhibited within 5 min while the response to caffeine increased in amplitude with time after membrane rupture.

In contrast with 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate and heparin, ryanodine (100 μm) proved equally effective in blocking responses to both caffeine and carbachol as shown in a typical record from a single cell (Fig. 5). Under control conditions, the average peak [Ca2+]c increase in response to caffeine was 98 ± 39 nm, while carbachol produced a mean increase of 99 ± 35 nm (n = 5). During superfusion with ryanodine, however, neither agonist produced any increase in [Ca2+]c in the five cells tested. The decrease in [Ca2+]c seen in each case simply reflected omission of Ca2+ from the caffeine- and carbachol-containing solutions (Fig. 5). Ryanodine also increased basal [Ca2+]c from 111 ± 19 nm under control conditions to 179 ± 18 nm (P < 0.001, n = 5), an effect which we have previously described and explained on the basis of a ryanodine-sensitive superficial buffer-barrier mechanism (White & McGeown, 2000a; White & McGeown, 2000b).

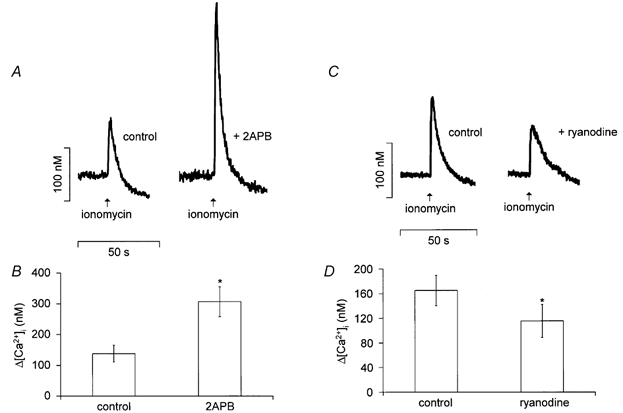

Further experiments were carried out to assess possible changes in the Ca2+ store content under relevant experimental conditions by applying ionomycin (25 μm) in zero Ca2+ solution to release these stores. The mean amplitude of the ionomycin-evoked Ca2+ transients was increased from 138 ± 27 nm in control conditions to 306 ± 48 nm in the presence of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (Fig. 6B; P < 0.005, n = 6). This again suggests that Ca2+ store loading is significantly increased in the presence of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate. Ryanodine reduced but did not abolish ionomycin-evoked transients, with a decrease in average amplitude from a control value of 165 ± 25 nm to 115 ± 27 nm in the presence of the drug (Fig. 6D; P < 0.02, n = 9). A 30 % reduction in store content seems unlikely to account adequately for the consistent and complete blockade of carbachol responses seen (Fig. 5).

Figure 6. Effects of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate and ryanodine on store content as assessed by ionomycin-evoked release.

A, the [Ca2+]c transient evoked from a fura-2-loaded myocyte by ionomycin (25 μm in zero Ca2+) was increased in the presence of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2ABP, 100 μm). B, bar chart summarizing the mean amplitude (± s.e.m.) of the ionomycin-dependent transient in six cells under control conditions and in the presence of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (* P < 0.005). C, ionomycin-evoked [Ca2+] transients in a myocyte before (control) and during superfusion with ryanodine (100 μm). D, summary data from nine cells exposed to the protocol illustrated in C (* P < 0.02).

Visualization of Ca2+ release channels

The results so far suggest that carbachol initiates ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release in gastric myocytes but that it does so via an IP3R-dependent mechanism. This implies that there may be co-operative interaction between IP3Rs and RyRs under these conditions. Such interaction would seem to require proximity and so the distributions of RyRs and IP3Rs were investigated. Individual cells were doubly labelled for both receptor types using fluorescent markers whose emission spectra allowed them to be separately imaged with the confocal microscope (Fig. 7). The image shown is representative of four other cells and demonstrates extensive overlap in the distributions of the two types of release channels.

Figure 7. Distribution of Ca2+ release channels.

Distribution of IP3Rs and RyRs in a single x,y plane from a gastric myocyte double labelled with polyclonal anti-IP3R antibody (green) and fluorescently labelled ryanodine (orange).

Discussion

Stimulation of Ca2+ release via RyRs by carbachol

Several lines of evidence lead us to believe that caffeine and carbachol ultimately activated the same release channels in gastric myocytes. Firstly, both agonists initiated release from the same sites in each cell tested and these sites coincided with any spontaneous Ca2+ release sites seen (Fig. 2). This suggests either that caffeine and carbachol stimulate release via the same channels or that release from RyRs and IP3Rs is indistinguishable at this level of spatial resolution. We favour the former explanation, with the observed release resulting from the opening of RyRs. Although caffeine is well known to activate RyRs directly (Rousseau & Meissner, 1989), we know of no evidence that it can activate IP3Rs; indeed it has been shown to inhibit them in vascular smooth muscle (Hirose et al.1993). The failure of IP3R inhibitors to block the caffeine responses also suggested that they were RyR-dependent (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Thus, visualizing the Ca2+ released by caffeine provides a map of RyR openings, the spatial distribution of which was indistinguishable from carbachol-evoked Ca2+ release (Fig. 2B). The spontaneous, localized Ca2+ transients were also inhibited by ryanodine but not by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (Fig. 1), indicating that these are Ca2+ sparks resulting from the opening of RyRs. Sparks have been described in both vascular and visceral smooth muscle (Nelson et al. 1995; Mironneau et al. 1996; Arnaudeau et al. 1997; Gordienko et al. 1998; Jaggar et al. 2000; Kirber et al. 2001), although spontaneous release via IP3Rs has also been reported (Bayguinov et al. 2000; Boittin et al. 2000). In the current study, as in a previous investigation of ileal myocytes (Gordienko et al. 1999), the response to carbachol included increased activity at Ca2+ spark sites (Fig. 2A), i.e. carbachol stimulated RyR opening.

Spontaneous, carbachol- and caffeine-evoked events were all inhibited by ryanodine, which was used at a high concentration in an attempt to lock RyRs closed (Rousseau et al. 1987). Interpreting these results as evidence for the involvement of RyRs in each case may be criticized on the basis that ryanodine may inhibit IP3-dependent responses indirectly by depleting a common SR store (Flynn et al. 2001). This is unlikely to account for the complete blockade of carbachol transients in the current experiments, however, since store content, as assessed using ionomycin in zero Ca2+ solution, was only reduced by approximately 30 % (Fig. 4C). It cannot be argued that this small reduction represents total depletion of the releasable store since we have previously demonstrated that ionomycin responses are completely inhibited following application of 10 mm caffeine in this cell type, indicating that caffeine and ionomycin release functionally similar stores, although by different mechanisms (White & McGeown, 2000b). It is also unlikely that carbachol blockade was secondary to the relatively small elevation of [Ca2+]c caused by ryanodine (Fig. 5) since Ca2+-dependent inhibition of IP3Rs has generally been reported when [Ca2+]c exceeds 300 nm (reviewed in Taylor, 1998). We believe, therefore, that 100 μm ryanodine directly inhibited both caffeine and carbachol responses by blocking RyRs. Taken together with the spatial correlations in the linescan data already discussed, this is consistent with the view that the carbachol-evoked Ca2+ responses seen were mediated by activation of RyRs in gastric myocytes. It should be remembered, however, that Ca2+ stores are probably organized differently in different smooth muscles. Recently reported studies on vascular tissue exemplify this well since agonist-dependent [Ca2+]c transients believed to be mediated via IP3 were completely inhibited by ryanodine in smooth muscle from renal, but not pulmonary, arteries (Janiak et al. 2001).

Carbachol responses required activation of IP3Rs

Postulating that carbachol responses are mediated by RyRs in rat gastric muscle begs the question whether IP3 plays any role at all in this response. A recent study on murine colonic myocytes found that acetylcholine raised basal [Ca2+]c by an IP3-independent mechanism and inhibited localized Ca2+ transients (Bayguinov et al. 2001). We found, however, that carbachol transients were selectively and completely inhibited by drugs which block IP3Rs (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4), leading us to conclude that IP3R activation was a necessary step in their initiation. Obviously, this hinges on the assumption that the drugs used produced the effects seen by inhibiting IP3Rs. This seems likely since the other reported actions of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate cannot easily explain our results. For example, this agent has been shown to inhibit Ca2+ uptake and to stimulate non-specific leak from the SR in smooth muscle cells (Missiaen et al. 2001). At concentrations > 10 μm it has also been reported to inhibit Ca2+-release activated Ca2+ influx in lymphocytes by an IP3R-independent mechanism (Prakriya & Lewis, 2001). Such actions might produce a non-specific inhibition of Ca2+ release through store depletion but this would be expected to diminish, rather than enhance, responses to caffeine and ionomycin. Heparin also has a range of actions which might affect Ca2+ handling (Taylor & Broad, 1998) but, of these, only inhibition of Ca2+ release via IP3Rs is shared with 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate. The inhibition of carbachol responses by both agents is, therefore, strong evidence for IP3R involvement.

Co-operation between IP3Rs and RyRs

If carbachol releases Ca2+ via RyRs through an IP3R-dependent mechanism then it seems reasonable to propose that co-operation between the two channels underpins this response in rat gastric myocytes. The cellular distribution of IP3Rs and RyRs suggests that extensive interaction is structurally feasible (Fig. 7). Production of IP3 and IP3R activation prior to RyR opening may also explain the relatively slow response to muscarinic stimulation, in which increased localized Ca2+ release activity clearly preceded a more global [Ca2+]c rise (Fig. 2A). Despite this difference in time course, however, caffeine and carbachol produce spatially similar patterns of Ca2+ depletion in the SR of this cell type when these are visualized directly using confocal microscopy and a low affinity Ca2+-indicator (White & McGeown, 2002). This is consistent with release mechanisms which ultimately depend on the same SR Ca2+.

A carbachol-induced increase in Ca2+ spark activity was first reported in ileal myocytes and this led to the suggestion that the relevant signalling pathway involves cross-talk between IP3Rs and RyRs (Gordienko et al. 1999). Functional studies using specific antibodies as inhibitors of SR channel activity suggest that Ca2+ release in response to IP3 production is at least partly RyR-dependent in vascular and duodenal myocytes (Boittin et al. 1999), although the fact that similar findings were not observed in ureteric myocytes again emphasizes that there may be considerable tissue differences in the level of receptor interaction (Boittin et al. 2000). Co-operation between different types of release channel may, nevertheless, be important in a range of cell types, e.g. it is believed to play a role in shaping [Ca2+]c responses in pancreatic acinar cells (Cancela et al. 2000). Possible mechanisms for such interaction include amplification of subresolution, IP3R-dependent Ca2+ signals by Ca2+-induced activation of adjacent RyRs or molecular coupling between receptors so that changes in IP3R conformation directly affect local RyRs. Establishing the significance of receptor co-operation and understanding how such co-operation comes about must be added to the list of goals in Ca2+-signalling research.

Role of IP3Rs in controlling Ca2+ store content

One unforeseen outcome of this study was the observation that inhibition of IP3Rs increased the filling of the Ca2+ store, as indicated by the increased amplitudes of the caffeine and ionomycin responses. The ionomycin results are important since release in this case does not depend on endogenous channels and so the enhanced response is unlikely to be explained by any direct effect of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate on RyRs. These findings lead us to speculate that a background Ca2+ leak via IP3Rs may limit SR content in smooth muscle, as previously proposed on theoretical grounds (van Breemen et al. 1995). This implies that Ca2+ release can occur via IP3Rs quite independently of RyR activation in rat gastric myocytes, even though such release does not seem to contribute to the observed [Ca2+]c rise in response to carbachol. The resolution and [Ca2+]c sensitivity limits for confocal microscopy probably explain our failure to detect obvious IP3R activity in linescan images (Fig. 1A). Similar negative results have been reported in other smooth muscle studies in which the pharmacology suggested that IP3Rs were indeed being activated (Janiak et al. 2001). The absence of observable local transients during IP3R activation might be explained by a diffuse, rather than a clustered distribution of receptors, by release into subresolution microdomains, perhaps adjacent to the plasma membrane or mitochondria, or by release pathways which bypass the cell cytoplasm altogether. We cannot distinguish between these in the current experiments. The possibility that tonic and agonist-evoked Ca2+ release may involve different IP3R subpopulations also deserves further study (Thrower et al. 2001).

Conclusions

Co-localization of carbachol-induced Ca2+ release with RyR release events, taken together with the effects of specific release antagonists, supports the hypothesis that agonist-induced, IP3-dependent [Ca2+]c responses depend on co-operation between different SR Ca2+ channels in gastric myocytes. It remains to be determined whether this interaction involves physical coupling between receptors or Ca2+-dependent activation of RyRs following IP3R-mediated release into a cytoplasmic microdomain (Rizzuto et al. 1993; Berridge, 1997).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a University of Bonn Medical Center grant ‘BONFOR’ (H.B.), the German-Israel collaborative research program of the MOS and the BMBF (H.B.), a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG EL 122/7) and the Center of Molecular Medicine Cologne/Zentrum für Molekularbiologische Medizin Köln (BMBF 01 KS 9502 to T.S.). We are grateful to Professor Klaus Rajewsky and Drs Werner Müller and Ralph Kühn for their helpful gifts of reagents. We thank Professor M. Taniguchi for the pCre-pac vector. We thank, Dr Xio-hua Chen and Dr George Miljanich for their support, Dr Wolfgang Nastainczyk (Universität des Saarlandes, Homburg) for the synthesis of peptides and antibodies, and Professor Y. Yaari for a critical revision of the manuscript.

D. Sochivko and A. Pereverzev contributed equally to this work.

References

- Arnaudeau S, Boittin FX, MacreZ N, Lavie JL, Mironneau C, Mironneau J. L-type and Ca2+ release channel-dependent hierarchical Ca2+ signalling in rat portal vein myocytes. Cell Calcium. 1997;22:399–411. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baro I, Eisner DA. Factors controlling changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration produced by noradrenaline in rat mesenteric-artery smooth-muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 1995;482:247–258. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayguinov O, Hagen B, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Sanders KM. Intracellular calcium events activated by ATP in murine colonic myocytes. American Journal of Physiology – Cell Physiology. 2000;279:C126–135. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.1.C126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayguinov O, Hagen B, Sanders KM. Muscarinic stimulation increases basal Ca2+ and inhibits spontaneous Ca2+ transients in murine colonic myocytes. American Journal of Physiology – Cell Physiology. 2001;280:C689–700. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.3.C689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Elementary and global aspects of calcium signalling. Journal of Physiology. 1997;499:2901–2306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boittin FX, Coussin F, Morel J-L, Halet G, MacreZ N, Mironneau J. Ca2+ signals mediated by Ins(1,4,5)P3-gated channels in rat ureteric myocytes. Biochemical Journal. 2000;349:323–332. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boittin FX, MacreZ N, Halet G, Mironneau J. Norepinephrine-induced Ca2+ waves depend on InsP3 and ryanodine receptor activation in vascular myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:C139–151. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.1.C139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdyga TV, Wray S. The effect of inhibition of myosin light chain kinase by Wortmannin on intracellular [Ca2+], electrical activity and force in phasic smooth muscle. Pflügers Archiv. 1998;436:801–803. doi: 10.1007/s004240050705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancela JM, Gerasimenko OV, Gerasimenko JV, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH. Two different but converging messenger pathways to intracellular Ca2+ release: the roles of nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate, cyclic ADP-ribose and inositol trisphosphate. EMBO Journal. 2000;19:2549–2557. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich BE, Kaftan E, Bezprozvannaya S, Bezprozvanny I. The pharmacology of intracellular Ca2+-release channels. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1994;15:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn ER, Bradley KN, Muir TC, Mccarron JG. Functionally separate intracellular Ca2+ stores in smooth muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:36411–36418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordienko DV, Bolton TB, Cannell MB. Variability in spontaneous subcellular calcium release in guinea-pig ileum smooth muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:707–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.707bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordienko DV, Greenwood IA, Bolton TB. Direct visualization of sarcoplasmic reticulum regions discharging Ca2+ sparks in vascular myocytes. Cell Calcium. 2001;29:13–28. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordienko DV, Zholos AV, Bolton TB. Membrane ion channels as physiological targets for local Ca2+ signaling. Journal of Microscopy. 1999;196:305–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1999.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Iino M, Endo M. Caffeine inhibits Ca2+-mediated potentiation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate induced Ca2+ release in permeabilized vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochemical Biophysical Research Communications. 1993;194:726–732. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Kajikuri J, Kuriyama H. Characteristic features of noradrenaline-induced Ca2+ mobilization and tension in arterial smooth muscle of the rabbit. Journal of Physiology. 1992;457:297–314. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH, Porter VA, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Calcium sparks in smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology – Cell Physiology. 2000;278:C235–256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiak R, Wilson SM, Montague S, Hume JR. Heterogeneity of calcium stores and elementary release events in canine pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology – Cell Physiology. 2001;280:C22–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.1.C22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirber MT, Etter EF, Bellve KA, LifshitZ LM, Tuft RA, Fay FS, Walsh JV, Fogarty KE. Relationship of Ca2+ sparks to STOCs studied with 2D and 3D imaging in feline oesophageal smooth muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 2001;531:315–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0315i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Kitazawa T, Somlyo AV, Somlyo AP. Cytosolic heparin inhibits muscarinic and alpha-adrenergic Ca2+ release in smooth muscle. Physiological role of inositol 1, 4,5-trisphosphate in pharmacomechanical coupling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:17997–18004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Kanaji T, Nakade S, Kanno T, Mikoshiba K. 2APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, a membrane-penetrable modulator of Ins(1,4,5)P3-induced Ca2+ release. Journal of Biochemistry. 1997;122:498–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironneau J, Arnaudeau S, MacreZ-Lepretre N, Boittin FX. Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves activate different Ca2+-dependent ion channels in single myocytes from rat portal vein. Cell Calcium. 1996;20:153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(96)90104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L, Callewaert G, De Smedt H, Parys JB. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate affects the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor, the intracellular Ca2+ pump and the non-specific Ca2+ leak from the non-mitochondrial Ca2+ stores in permeabilized A7r5 cells. Cell Calcium. 2001;29:111–116. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Lederer WJ. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science. 1995;270:633–637. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Potentiation and inhibition of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels by 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB) occurs independently of IP3 receptors. Journal of Physiology. 2001;536:3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R, Brini M, Murgia M, Pozzan T. Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria. Science. 1993;262:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.8235595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau E, Meissner G. Single cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channel: activation by caffeine. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:H328–333. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.2.H328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau E, Smith JS, Meissner G. Ryanodine modifies conductance and gating behavior of single Ca2+ release channels. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:C364–368. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.3.C364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CW. Inositol trisphosphate receptors: Ca2+-modulate intracellular Ca2+ channels. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998;1436:19–33. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CW, Broad LM. Pharmacological analysis of intracellular Ca2+ signalling: problems and pitfalls. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1998;19:370–375. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrower EC, Hagar RE, Ehrlich BE. Regulation of Ins(1,4,5)P-3 receptor isoforms by endogenous modulators. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2001;22:580–586. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01809-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Breemen C, Chen Q, Laher I. Superficial buffer barrier function of smooth muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1995;16:98–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88990-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C, McGeown JG. Ca2+ uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum decreases the amplitude of depolarization-dependent [Ca2+]i transients in rat gastric myocytes. Pflügers Archiv. 2000a;440:488–495. doi: 10.1007/s004240000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C, McGeown JG. Regulation of basal intracellular calcium concentration by the sarcoplasmic reticulum in myocytes from the rat gastric antrum. Journal of Physiology. 2000b;529:395–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C, McGeown JG. Imaging of changes in sarcoplasmic reticulum [Ca2+] using Oregon Green BAP TA 5N and confocal scanning laser microscopy. Cell Calcium. 2002;31:151–159. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2001.0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]