Abstract

The mechanisms underlying the response of airway afferent nerves to low pH were investigated in an isolated guinea-pig airway nerve preparation. Extracellular recordings were made from single jugular or nodose vagal ganglion neurons that projected their sensory fibers into the airways. The airway tissue containing the mechanically sensitive receptive fields was exposed into acidic solutions. Rapid and transient (∼3 s) administration of 1 mm citric acid to the receptive field consistently induced action potential discharge in nociceptive C-fibers (41/44) and nodose Aδ fibres (29/30) that are rapidly adapting low threshold mechanosensors (RAR-like fibres). In contrast, citric acid activated only 8/17 high threshold mechanosensitive jugular Aδ fibres. The RAR-like fibres were slightly more sensitive than C-fibres to acidic solutions (pH threshold > 6.7). The RAR-like fibres response to the ∼3 s acid treatment was not affected by a vanilloid receptor 1 (VR1) antagonist, capsazepine (10 μM), and was rapidly inactivating (action potential discharge terminated before the acid administration was completed). Gradual reduction of pH did not activate the RAR-like fibres even when the pH was reduced to ∼5.0. The C-fibres responded to the gradual reduction of pH with persistent action potential discharge that was nearly abolished by capsazepine (10 μM) and inhibited by over 70% with another VR1 antagonist iodo-resiniferatoxin (1 μM). In contrast the C-fibre response to the transient ∼3 s exposure to pH ∼5.0 was not affected by the VR1 antagonists. We conclude that activation of guinea-pig airway afferents by low pH is mediated by both slowly and rapidly inactivating mechanisms. We hypothesize that the slowly inactivating mechanism, present in C-fibres but not in RAR-like fibres, is mediated by VR1. The rapidly inactivating mechanism acts independently of VR1, has characteristics similar to acid sensing ion channels (ASICs) and is found in the airway terminals of both C-fibres and RAR-like fibres.

Airway inflammation is associated with afferent nerve activation leading to cough, changes in respiratory pattern and changes in autonomic neuronal tone. Despite their substantial importance, the mechanisms by which inflammation leads to stimulation of afferent nerves are incompletely understood. Several studies support the hypothesis that various inflammatory mediators play a role in exciting airway afferent nerves by direct stimulation, by increasing their excitability or indirectly by smooth muscle/ vasculature-mediated effects (Carr & Undem, 2001).

In addition to the release of inflammatory mediators, inflammation typically causes a decrease in extracellular pH (Häbler, 1929; Andersson et al. 1999; Hunt et al. 2000). Indeed, the pH of de-aerated exhaled airway vapor condensate is substantially lower in asthmatic subjects as compared with control subjects and this is normalized with anti-inflammatory corticosteroid therapy (Hunt et al. 2000). Hydrogen ions can activate afferent nerves by opening various ion channels including acid sensing ion channels and capsaicin receptor VR1 (Tominaga et al. 1998; Waldmann et al. 1999). Therefore, hydrogen ions may contribute to inflammation-induced changes in airway afferent nerve activity.

Another possible role for hydrogen ions in activation of airway afferent nerves is in CO2 chemosensitivity. Carbon dioxide can activate airway afferent nerves from the lungs and larynx (Coates et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1999; Sant'Ambrogio & Widdicombe, 2001), and can also increase the excitability of pulmonary C-fiber afferent fibers to other stimuli (Gu & Lee, 2002). The mechanism by which this occurs is not well understood, but the data favor the hypothesis that increases in CO2 concentration affect afferent nerve endings by forming hydrogen ions and acidifying the micro-environment around the nerve terminals within the airway wall (Coates et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1999; Gu & Lee, 2002). This may be relevant to airway reflex changes that may occur during disorders that lead to increases in PCO2 such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or obstructive sleep apnea (Berger et al. 2000).

An understanding of the airway afferent nerve response to hydrogen ions is also relevant to studies relating to pulmonary pharmacology. Inhalation challenge with low pH solutions, particularly citric acid, is a common tool used to study respiratory reflexes in humans and laboratory animals (Lowry et al. 1988; Karlsson & Fuller, 1999). In guinea-pigs, inhaled citric acid triggers several respiratory responses including bronchoconstriction and cough (Forsberg et al. 1988; Daoui et al. 1998). There seems to be agreement that in this species citric acid causes bronchoconstriction, in large part, by releasing neuropeptides from afferent bronchial C-fibres (Satoh et al. 1993; Daoui et al. 1998; Ricciardolo et al. 1999). This is consistent with the observation that citric acid activates guinea-pig airway C-fibers studied in vitro. The mechanism by which citric acid discharges action potentials in guinea-pig C-fibers is thought to be secondary to opening of the VR1 channel. Thus, activation of guinea-pig tracheal C-fibers by low pH or capsaicin is inhibited by the VR1 antagonist capsazepine (Fox et al. 1995).

Citric acid also induces cough in guinea-pigs, which is partially inhibited by capsazepine (Lalloo et al. 1995). This may be due to C-fiber activation leading to the cough reflex directly or secondarily through activation of rapidly adapting receptors (RARs) due to the vascular and bronchoconstrictor effects of the tachykinins released from activated C-fibres. (Joad et al. 1997; Widdicombe, 1998). In any event, even in the presence of large doses of capsazepine, citric acid was capable of causing cough in guinea-pigs especially when larger doses of citric acid were inhaled. Thus, citric acid may also stimulate airway afferents by mechanisms that do not involve VR1. This notion is also supported by the resistance to capsazepine of lactic acid-induced bronchoconstriction in newborn dogs (Nault et al. 1999). In this light it is noteworthy that acid sensing ion channels other than VR1 are present not only in small neurons that project unmyelinated C-fibres but also in large and medium-sized neurons projecting myelinated A class of afferent fibres (Garcia-Anoveros et al. 2001). Consistently, cough to citric acid is abolished by thermal inhibition of conduction in myelinated A class airway afferent fibres in dogs (Tatar et al. 1994).

In the present study, we investigated hydrogen ion-induced action potential discharge in afferent nerves situated in the guinea-pig trachea/bronchus in vitro. We show that low pH solutions consistently activate C-fibers and RAR-like Aδ fibres. Our data support the hypothesis that hydrogen ions can activate airway afferent nerves by VR1 dependent and independent mechanisms.

Methods

Tissue preparation

Male Hartley guinea-pigs (100-200g) were killed by exposure to CO2 followed by exsanguination. The airways with intact right-side extrinsic innervation (including nodose and jugular ganglia) were removed and placed in a dissecting dish containing Krebs bicarbonate buffer solution gassed with 95 % O2-5 % CO2 and composed of (mm): NaCl, 118; KCl, 5.4; NaH2PO4, 1.0; MgSO4, 1.2; CaCl2, 1.9; NaHCO3, 25.0; dextrose, 11.1 (pH 7.4). Indomethacin (3 μM) was added to the buffer solution at the beginning of the experiment to reduce the complications caused by prostanoid released from the airway tissue. This concentration was shown to completely block prostanoid production in our airway preparation (Undem et al. 1987). Connective tissue was trimmed away, leaving the trachea, larynx and right bronchus with intact nerves (vagus, superior laryngeal, and recurrent), including nodose and jugular ganglia. A longitudinal cut was made along the ventral surface to open the larynx, trachea and bronchus. Airways were then pinned to a Sylgard-lined Perspex chamber. The right nodose and jugular ganglia, along with the rostral-most vagus and superior laryngeal nerves, were gently pulled through a small hole into an adjacent compartment of the same chamber for recording single fibre activity. Both compartments were superfused with the Krebs bicarbonate solution. The temperature of the buffer was maintained at 35 °C with a flow rate of 6–8 ml min−1. Studies using blue dye revealed that the buffer solutions perfusing each compartment remained separate. This method has been described previously (Carr et al. 2001). The experiments were approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use committee.

Extracellular recording of action potentials

Extracellular recordings were performed by manipulating a fine aluminosilicate glass electrode near cell bodies in either the jugular or nodose ganglion. The microelectrodes were pulled using a Flaming-Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument Company, Novato, CA, USA) and filled with 3 m sodium chloride. The filled electrode was placed into an electrode holder connected directly to a headstage (A-M Systems, Everett, WA, USA). A return electrode of silver-silver chloride wire and an earthed silver-silver chloride pellet were placed in the perfusion fluid of the recording chamber and attached to the headstage. The recorded signal was amplified (A-M Systems) and filtered (low cut off, 0.3 kHz; high cut off, 1 kHz) and the resultant activity was displayed on an oscilloscope (TDS 340, Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA) and a model TA240S chart recorder (Gould, Valley View, OH, USA). The data were stored on digital tape (DTC-59ES, Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) for off-line waveform analysis on a Macintosh computer using the software program TheNerveOfIt (PHOCIS, Baltimore, MD, USA). The data were further processed using spreadsheet software (Microsoft Excel 98).

Discrimination of single fibre activity, location of receptive fields, determination of the mechanical threshold and calculation of conduction velocities

Single fibre activity was discriminated by placing a concentric electrical stimulating electrode on the recurrent laryngeal nerve, through which the majority of fibres enter the trachea (Riccio et al. 1996b).The recording electrode was placed within the ganglion and manipulated until single unit activity was detected. When electrically evoked action potentials were seen, the stimulator was switched off and the trachea and bronchi were gently probed with a von Frey filament (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA). Mechanically sensitive receptive fields were revealed when a burst of action potentials was elicited in response to von Frey filament stimulation. Mechanical thresholds were determined for each nerve ending by using von Frey filaments calibrated to give fixed amounts of force ranging from 0.078 to 2.738 mN. Beginning with the lowest force von Frey filament, nerve endings were gently probed with filaments of increasing force until a threshold mechanical sensitivity was determined. This was achieved when touching the receptive field evoked a burst of action potentials. Confirmation of threshold sensitivity was established by probing the nerve ending with the subthreshold filament. Conduction velocities were calculated by electrically stimulating the receptive field and measuring the distance travelled along the nerve pathway divided by the time between the shock artifact and the recorded action potential. Conduction velocity and amplitude of the action potential were then compared with responses elicited by electrical stimulation of either the superior laryngeal, recurrent laryngeal, or vagus nerve trunks in order to determine the trunk that supplied the fibre.

In vast majority of experiments one fibre per animal was recorded. Occasionally, the activity of two fibres projecting to the airways was recorded simultaneously.

Acidic stimuli

During the acidic challenge the tip of a pipette was inserted just beneath the surface of the superfusion solution at the site of receptive field (particular caution was made not to touch the airway surface) and 500 μl of acidic solution was applied in ≈3 s. Administration of a relatively large volume (500 μl) compared with the volume of the superfusate buffer over the receptive field (depending on the area of the receptive field, but < 100 μl in all cases) led to near-complete replacement of superfusate buffer by acidic solution at the site of application. By using this approach the potential effects of dilution and buffering were minimized and therefore the pH of the solution in contact with the airway surface at the site of application was essentially the pH of the administered acidic solution. Administration of Krebs bicarbonate solution in the described manner did not activate airway nerve terminals thereby excluding the possibility that the receptive field was excited by any subtle mechanical effect of the fluid flow.

Acidic solutions used in the present study were: citric acid 0.03-10 mm diluted in saline, hydrochloric acid diluted in saline (0.6 mm; pH 3.2), low bicarbonate buffer of the following composition (mm): NaCl, 142; KCl, 5.4; NaH2PO4, 1.0; MgSO4, 1.2; CaCl2, 1.9; NaHCO3, 1.0; dextrose, 11.1, and phosphate buffer of the following composition (mm): NaCl, 118.5; KCl, 1.7; KH2PO4, 6.6; MgSO4, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.5; dextrose, 10.0. With the exception of several experiments described separately, all acidic solutions were administered as a 500 μl volume in ≈3 s. It should be emphasized that the exact pH at the site of nerve terminal was not known and could not have been measured, because localization of nerve terminal within the airway wall is not precisely determined. However, all tissues were treated in an identical fashion allowing for the comparison of responses. In addition, the paired arrangement of experiments warrants comparison of similar stimuli.

Concentration-dependent response to citric acid

To examine the relationship between concentration of citric acid and response of afferent nerve ending, the following concentrations of citric acid were administered (mm; pH in brackets): 0.03 (5.6), 0.1 (4.0), 0.3 (3.7), 1 (3.2), and 10 (2.6) in the manner described above separated by 5 min intervals.

Role of citrate anion in the response to citric acid

To assess the role of citrate anion, response to citric acid and hydrochloric acid solutions of the same pH were compared. In these experiments citric acid and hydrochloric acid of the same pH (3.2) were applied at 5 min intervals in a random order in the manner described above. Response to 500 μl of 10 mm sodium citrate (pH = 7.3) was also tested.

Effect of capsazepine on the response to citric acid

To examine the effect of capsazepine on citric acid-induced activation, the response of the nerve ending to 1 mm citric acid was first recorded. Then, Krebs solution containing 10 μM capsazepine was superfused through the airway compartment of the recording chamber for at least 15 min. The response to 1 mm citric acid was again obtained while the receptive field was still being superfused with capsazepine-containing Krebs bicarbonate solution. Preliminary experiments have shown that airway afferents did not desensitize in response to repeated administration of citric acid (up to four applications of 10 mm citric acid with 15 min intervals).

Challenge with low bicarbonate buffer

A challenge with 500 μl volume of the low bicarbonate buffer (pH = 6.7, for composition see above) was used to assess the threshold for low pH-induced activation.

Capsaicin challenge

Capsaicin challenge was performed by adding 20 μl of 1 μM capsaicin directly over the receptive field using a transfer pipette. If no response was elicited the challenge was repeated with an increased volume of 500 μl. We found that this stimulus elicited maximal response to capsaicin.

Response to rapid vs. gradual change of pH

Preliminary experiments indicated that acid sensing mechanisms of some fibres inactivate rapidly in response to pH reduction, while other fibres showed a slowly inactivating pattern of response. Therefore, the ability of a fibre to respond to rapid short-lasting and to slow gradual change of pH was tested. In addition, potency of VR1 antagonists capsazepine and iodo-resiniferatoxin against each type of challenge was examined.

Rapid, short-lasting reduction of pH was induced by administration of 500 μl volume of phosphate buffer (for composition see above) in ≈3 s. Gradual reduction of pH was achieved with superfusion with phosphate buffer. Superfusion with phosphate buffer during a 6 min period gradually decreased the pH in the airway compartment from 7.4 to ≈5. The time course of pH reduction was determined measuring pH in the samples collected every 60 s using a pH meter (Cole-Palmer, Chicago, IL, USA). Since the manipulation required to collect samples introduced unavoidable electrical noise, this measurement could not be performed simultaneously with the recording of nerve fibre activity. However, in every experiment, the final pH was measured from the sample collected at the end of phosphate buffer superfusion. Electrical activity was recorded during the 6 min of airway compartment superfusion with phosphate buffer. The pH in the airway compartment was then normalized to 7.4 (measured in the sample) by a 15 min superfusion with Krebs bicarbonate solution. After normalization of pH the airway tissue was challenged with the 500 μl phosphate buffer (pH ≈5) in the manner described at the beginning of Methods. Then, the tissue was superfused with the Krebs bicarbonate solution containing VR1 antagonist (either capsazepine (10 μM) for 15 min or iodo-resiniferatoxin (1 μM) for 30 min) and gradual and rapid reduction of pH was repeated, this time with VR1 antagonist present in all solutions used. In three preliminary experiments we showed that the response to superfusion with phosphate buffer was reproducible.

Two structurally unrelated VR1 antagonists capsazepine (10 μM) and iodo-resiniferatoxin (1 μM) were used. Capsazepine is a well established VR1 antagonist (Urban & Dray, 1991). Iodo-resiniferatoxin, a recently characterized selective VR1 antagonist, was shown to inhibit capsaicin-induced responses both in vitro and in vivo (Wahl et al. 2001). In preliminary experiments in our guinea-pig airway nerve preparation 1 μM iodo-resiniferatoxin abolished response to 1 μM capsaicin (n = 5).

Drugs and solutions

Citric acid and trisodium citrate were purchased from Sigma Chemicals Co. (St Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in 0.9 % saline. Hydrochloric acid was diluted in 0.9 % saline, the amount of acid was adjusted to obtain pH = 3.2 while pH was simultaneously measured by a pH meter (Cole-Palmer, Chicago, IL, USA). Indomethacin (Sigma) was made up as a 30 mm stock solution in water and added to Krebs solution to a final concentration 3 μM. Capsaicin (Sigma) was made up as a 10 mm stock solution with ethanol and diluted in Krebs solution to a final concentration 1 μM. Capsazepine (Sigma) was made up as a 10 mm stock solution with dimethylsulfoxide and diluted in Krebs solution to a final concentration 10 μM. Iodo-resiniferatoxin (Tocris, Ellisville, MO, USA) was made up as 1 mm stock with dimethylsulfoxide and diluted to a final concentration 1 μM.

Data analysis

Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. and were compared using Student's paired or non-paired t test when appropriate.

Results

General characteristics

A total of 100 afferent fibres supplying the trachea and right main bronchus from 91 guinea-pigs were investigated. Of these, the cell bodies of 34 were located in the nodose ganglion and the cell bodies of 66 were situated in the jugular ganglion. The majority of the fibres showed virtually no spontaneous activity. A few fibres with irregular spontaneous discharge were not studied further. The fibres were subclassified as Aδ fibres (> 2.0 ms−1) and C-fibres (< 1.0 ms−1; Canning & Undem, 1993). Six fibres that conducted in the intermediate range (1.0-2.0 ms−1) were excluded (nodose, n = 1; jugular, n = 5). The majority of the nodose-derived fibres (30/34) supplying trachea and main bronchus conducted in the Aδ range (4.8 ± 0.4 ms−1). Jugular ganglion cells projected both Aδ fibres (17/66, conduction velocity 7.8 ± 1.3 ms−1) and C-fibres (44/66, conduction velocity 0.7 ± 0.04 ms−1). Because of our search protocol all fibres studied had mechanically sensitive receptive fields in the airway wall. These electrophysiological findings are consistent with prior studies (Riccio et al. 1996a; McAlexander et al. 1999).

Response to citric acid

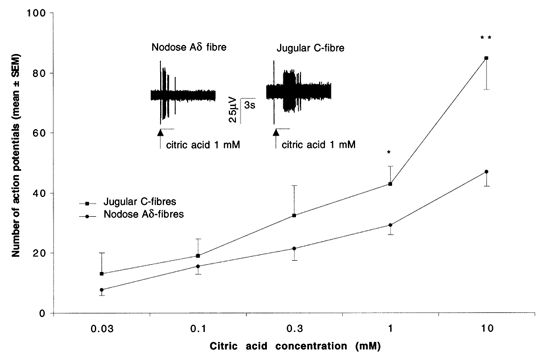

Twenty nine out of thirty nodose Aδ fibres and 41/44 jugular C-fibres responded to administration of 500 μl of citric acid (1 μM) directly over the receptive field. Similarly, 3/3 nodose C-fibres responded to citric acid. By contrast, only 8/17 jugular Aδ fibres responded to citric acid. A detailed characterization of the response to acid was carried out only on nodose Aδ and jugular C-fibres. The pattern of citric acid-induced action potential discharge differed between nodose Aδ and jugular C-fibres (Fig. 1, inset). Nodose Aδ fibres responded to the ≈3 s administration of 500 μl citric acid (1 mm) with an immediate burst of action potentials that rapidly (within a few seconds) adapted even as the citric acid was still being applied. Jugular C-fibers also responded with an immediate burst of action potentials, but the response persisted until after the citric acid application ceased.

Figure 1. Concentration-response curve of nodose Aδ fibres and jugular C-fibres to citric acid.

Citric acid was administered as 500 μl volume in ≈3 s into superfusion over the mechanically sensitive receptive field at 5 min intervals. Each point represents mean ± s.e.m. of at least 5 experiments. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.001.Inset, representative traces of a nodose Aδ fibre (left) and a jugular C-fibre (right) response to administration of 500 μl of 1 mm citric acid into superfusion over the mechanically sensitive receptive field. Vertical line preceding the burst of action potentials is an artifact caused by pipette manipulation and indicates the beginning of acid administration. Note immediate onset and shorter duration of action potential discharge in nodose Aδ fibre compared with jugular C-fibre.

Concentration-dependent response to citric acid

Both nodose Aδ fibres and jugular C-fibres responded to citric acid in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1). The number of action potentials evoked by lower concentrations of citric acid (0.03-0.3 mm) did not differ significantly between nodose Aδ and jugular C-fibres but the response of jugular C-fibres to large concentrations of citric acid (1 mm and 10 mm) was significantly larger compared with nodose Aδ fibres.

Response to low bicarbonate buffer

Whereas all nodose Aδ fibres were activated by the lowest concentration of citric acid used in dose-response experiments (0.03 mm) this was not true for jugular C-fibres suggesting that their threshold for low pH activation is higher (i.e. the pH required for activation is lower). Consistent with this notion, we found that challenge with low-bicarbonate buffer (pH = 6.7) induced at least five action potentials in all 7/7 tested nodose Aδ fibres, compared with only 2/10 tested jugular C-fibres (Fig. 2). These data illustrate that nodose airway Aδ fibres are more sensitive to decreases in pH than the population of jugular C-fibres.

Figure 2. Percentage of nodose Aδ and jugular C-fibres responding to low bicarbonate buffer, pH = 6.7.

Low bicarbonate buffer was administered as a 500 μl volume in ≈3 s into superfusion over the mechanically sensitive receptive field. Inset, representative trace of a nodose Aδ fibre response to low bicarbonate buffer. Vertical line preceding the burst of action potentials is an artifact caused by pipette manipulation and indicates the beginning of low bicarbonate buffer administration.

Role of citrate anion in the response to citric acid

Sodium citrate (10 mm) did not induce action potential discharge in any nodose Aδ (n = 3) or jugular C-fibres (n = 3) tested thereby excluding the possibility that citrate anion exerts stimulatory effects without reduction of pH. Response to citric acid and hydrochloric acid solutions of the same pH (pH = 3.2) did not significantly differ in nodose Aδ fibres (28 ± 2 vs. 29 ± 1; P > 0.1, n = 4), or in jugular C-fibres (32 ± 7 vs. 26 ± 2; P > 0.1, n = 5).

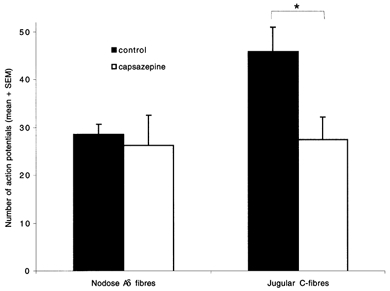

Effect of capsazepine

Capsazepine inhibits low pH-induced activation of the capsaicin receptor VR1 (Tominaga et al. 1998; Caterina et al. 2000; Smart et al. 2001). We investigated the effect of capsazepine on the citric acid-induced response of nodose Aδ and jugular C-fibres. Capsazepine (10 μM) did not affect response of nodose Aδ fibres, but significantly inhibited the response of the jugular C-fibres to 1 mm citric acid (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Effect of 10 μM capsazepine on citric acid-induced response.

Response to administration of 500 μl volume of citric acid (1 mm) into superfusate over the mechanically sensitive receptive field was recorded before and after 15 min superfusion with 10 μM capsazepine. Left, response of nodose Aδ fibres was unaffected by capsazepine (n = 5). Right, capsazepine significantly inhibited jugular C-fibres response to 1 mm citric acid (n = 9). * P < 0.05.

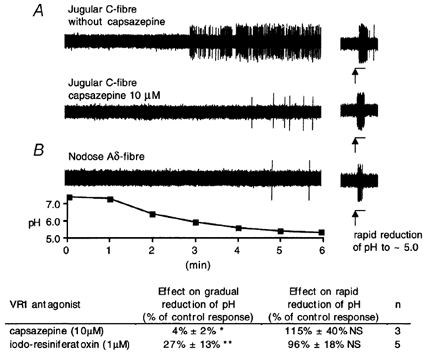

Response to rapid vs. gradual change of pH

In preliminary experiments, we increased the volumes (200-1000 μl) of citric acid (1 mm) that was administered to the receptive field at an approximately constant rate (≈200 μl s−1) at 5 min intervals. The number of action potentials increased in jugular C-fibres for each increase in volume applied (n = 2, data not shown). In contrast, the response of nodose Aδ fibres reached maximum at a volume of 600 μl and did not increase further (n = 2, data not shown). This was consistent with the observation that the response of nodose Aδ fibers to 500 μl volume of 1 mm citric acid in ≈3 s adapted before the completion of the acid administration (Fig. 1; inset). These experiments suggest the presence of rapidly inactivating mechanisms mediating the response to citric acid in nodose Aδ fibres. On the other hand, in jugular C-fibres at least portion of the response to citric acid was mediated by a slowly inactivating mechanism. In addition, a rapidly inactivating mechanism was implicated in C- fibres by the adapting nature of their response to citric acid in the presence of capsazepine (data not shown).

To address this issue further, we designed an experiment in which the pH of the buffer solution gradually declined from 7.4 to ≈5.0. Once a threshold was reached, this consistently caused a persistent action potential discharge in jugular C-fibres (Fig. 4). This non-adapting response of jugular C-fibers to gradual decrease of pH was virtually abolished by capsazepine and substantially reduced (> 70 %) by I-RTX (Fig. 4; inset table). In contrast, neither capsazepine nor I-RTX affected the response to a subsequent 3 s administration of 500 μl of phosphate buffer of the same pH ≈5.0 (Fig. 4; inset table). These results indicate that one of the mechanisms mediating response to low pH in jugular C-fibres was VR1-independent and rapidly inactivating and that the other was VR1-mediated and slowly inactivating. In contrast to the jugular C-fibers, gradual decrease of pH from 7.4 to ≈5.0 failed to induce action potential discharge in nodose Aδ fibres (n = 3, no activation in two fibres, and only a few action potentials noted in the third fibre). However, rapid reduction of pH from 7.4 to ≈5.0 excited these fibres. This finding is consistent with a rapid inactivation of an acid sensing mechanism in nodose Aδ fibres.

Figure 4. Representative traces of a jugular C-fibre (A) and a nodose Aδ fibre (B) response to gradual reduction of pH from 7.4 to ≈5 (left traces) and rapid reduction of pH from 7.4 to ≈5 (right traces) and the effect of capsazepine and iodo-resiniferatoxin on these responses.

A, superfusion with phosphate buffer gradually reduced pH at the receptive field from 7.4 to ≈5.0 (see pH trace) and induced persistent action potential discharge of jugular C-fibre (A, left upper trace). After recovery of pH to 7.4 by superfusion with Krebs solution, rapid reduction of the pH to from 7.4 to ≈5.0 by administration of 500 μl of phosphate buffer induced a short burst of action potential discharge (A, left upper trace, note change in chart speed, horizontal 3 s bars indicate phosphate buffer administration). Then, 10 μM capsazepine was added to Krebs solution and tissue was superfused for 15 min. Capsazepine prevented persistent activation of the same jugular C-fibre by subsequent gradual reduction of pH from 7.4 to ≈5.0 (A, left lower trace). In contrast, capsazepine did not affect response to rapid reduction of the pH from 7.4 to ≈5.0 after pH recovery to 7.4 (A, right lower trace). B, gradual reduction of pH from 7.4 to ≈5.0 failed to activate nodose Aδ fibre (B, left) but rapid reduction of pH from 7.4 to ≈5.0 induced burst of action potential discharge (B, right). Beneath the figure is the tabulation of results showing inhibitory effects of capsazepine (10 μM) and iodo-resiniferatoxin (1 μM) on gradual and rapid reduction of pH. Experiments with iodo-resiniferatoxin were performed in the same manner as with capsazepine except that the tissue was superfused with iodo-resiniferatoxin for 30 min. Data are shown as the percentage decrease in the number of action potentials evoked in the absence of the inhibitor. In the absence of inhibitor the C-fibres evoked an average of 192 ± 40 action potentials in response to the gradual reduction of pH, and 34 ± 8 action potentials in response to rapid reduction of pH. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, NS not significant.

Correlation between sensitivity to capsaicin and gradual change of pH

We evaluated 10 jugular C-fibres for their response to a gradual reduction of pH and for their sensitivity to capsaicin. Nine out of ten fibres responded with action potential discharge to both a gradual decrease in pH and to 1 μM capsaicin. The one jugular C-fibre not responding to gradual pH reduction was also insensitive to capsaicin.

Discussion

The data reveal that a modest decrease in extracellular pH can lead to activation of nodose ganglion derived Aδ fibres in the guinea-pig airways. The data also reveal that a decrease in pH can activate nearly all jugular ganglion derived nociceptive C-fibre afferents in the airway. By contrast only a minority of jugular ganglion derived Aδ fibres are activated by low pH solutions. The data support the hypothesis that hydrogen ions act through at least two distinct mechanisms to activate airway afferent nerves. Low pH activation of airway jugular C-fibres is mediated by both VR1-dependent and VR-1 independent mechanisms. By contrast, hydrogen ions activate nodose derived Aδ fibres only through VR1-independent mechanisms. These findings are in conflict with conclusions drawn from the study of Fox et al. (1995), where airway Aδ fibres were found to be categorically insensitive to pH changes, and no evidence of a VR1-independent mechanism was noted in C-fibres.

Previous studies from our laboratory demonstrated that the mechanosensitive and chemosensitive properties of guinea-pig airway nerve endings depend on the ganglionic origin of the supplying nerve fibre (Riccio et al. 1996a; Pedersen et al. 1998; Kajekar et al. 1999; McAlexander et al. 1999). Nerve fibres originating in the jugular ganglion conduct in both the Aδ and C range. Their airway nerve endings are slowly adapting high-threshold mechanosensors that have physiological characteristics consistent with nociceptors. In contrast, nodose ganglion neurons project Aδ fibres into the airway that are rapidly adapting, low-threshold mechanosensors. Considering their electrophysiological and mechanical properties it is reasonable to conclude that the nodose Aδ fibre nerve endings studied here are analogous to the RARs that have been characterized in vivo (Knowlton & Larrabee, 1946) so they are referred as RAR-like receptors.

Low pH excites nodose Aδ fibres by a mechanism that is not inhibited by large concentrations of the VR1 antagonist capsazepine. Although the mechanism by which acid activates these fibres cannot be determined by our results, the observations that the activation threshold occurred at an airway surface with a pH of about 6.7, and that the fibres responded to acid in a rapidly inactivating fashion, are informative. These characteristics are consistent with the speculation that certain acid sensing ion channels (ASICs) are involved. Thus far several ASICs have been characterized (ASIC1α, 1β, ASIC2a, 2b, ASIC3, and ASIC4) (Alvarez De La Rosa et al. 2002). It was shown in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons that medium to large diameter neurofilament-positive neurons express ASIC1, ASIC2 and ASIC3 (Alvarez De La Rosa et al. 2002) and we have previously documented that the RAR-like afferent fibres in the guinea-pig airway are derived from medium to large diameter, neurofilament-positive neurons in the nodose ganglia (Riccio et al. 1996a). ASIC3 (also known as DRASIC) is particularly interesting as the pH threshold for activation of the channel is between 6.5 and 7.0, and it responds to acid in a rapidly inactivating fashion (Sutherland et al. 2001). In fact, at a pH of ≈7.0 this channel may be inactivated in the absence of activation. This could explain why the nodose RAR-like fibres in the airway failed to respond to a pH of even 5.0 when the pH was decreased in a gradual fashion. However, it should be kept in mind that the response of a nerve to a drop in pH may be complex and involve more than a single ion channel (Benson et al. 2002). To determine the contribution to ASIC in acid-induced activation of airway nerve endings will require the use of currently unavailable selective inhibitors of ASICs. Many ASICs are inhibited by amiloride, but only at concentrations shown to non-specifically attenuate responses of airway afferents in our model (Carr et al. 2001).

It is unlikely that the acid-induced activation nodose Aδ fibres was an indirect effect of autacoids released in the airway wall. We demonstrated that the onset of acid-induced activation of these fibres was immediate (within 1 s). Moreover, the fibres were activated by brief administration of 500 μl of phosphate buffer but not by prolonged exposure to the same buffer (Fig. 4). It would be expected, however, that any mediator reflecting non-specific tissue damage due to hydorgen ions should be released (likely in much larger quantities) during the prolonged exposure to low pH. In addition, we have not yet found an autacoid capable of consistently activating nodose Aδ fibres in the guinea-pig airway (histamine, 5-HT, bradykinin, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, are all ineffective, Authors’ unpublished observations). It is also worth noting that even large hydrogen ion concentrations do not indiscriminately activate sensory nerves as more than half (9/17) of the jugular Aδ fibres failed to respond to the lowest pH used (pH = 2.8). Finally, the data indicate that brief exposure to hydrogen ions does not have a toxic effect on the nerve terminals in as much as the mechanical sensitivity of the afferent fibre was not affected by this treatment.

In contrast to nodose Aδ RAR-like fibres, jugular C-fibres possess both rapidly inactivating and slowly inactivating acid-sensing mechanisms. We cannot determine whether the rapidly inactivating mechanism of jugular C-fibres is the same as in nodose Aδ fibres. It is noteworthy in this regard that by contrast to the medium and large diameter neurons, small diameter neurons in rat DRG express predominantly ASIC1 (Alvarez De La Rosa et al. 2002). Lower pH-sensitivity of C-fibres is also consistent with this characteristic of ASIC1.

Several lines of evidence indicate that VR1 is responsible for the slowly inactivating portion of jugular C-fibres response to low pH. First, the response was nearly abolished by the VR1 antagonist capsazepine. Second, the response was substantially reduced (> 70 %) by the structurally different selective VR1-antagonist I-RTX. Third, unlike nodose Aδ fibres that lacked slowly inactivating responses to low pH, jugular C-fibres are consistently activated by selective VR1 agonist capsaicin (Riccio et al. 1996a). Indeed, perfect concordance of the jugular C-fibres responses to capsaicin and to gradual pH reduction in this study adds further support for the role of VR1. Interestingly VR1 gene knock-out decreased the prevalence of acid-responsive C-fibres in a mouse skin-nerve preparation (Caterina et al. 2000).

Acid could lead to activation of VR1 in airway nerves directly or indirectly through the release of an endogenous VR1 agonist. Potential endogenous VR1 agonists in the airways include anandamide and lipoxygenase products of arachidonic acid (Zygmunt et al. 1999; Hwang et al. 2000). The extent to which decreases in surface pH evokes the synthesis and release of these chemicals in the airway is unknown. Hydrogen ions may also interact directly with VR1 in airway C-fibres. When studied at physiological temperatures, whole-cell and single-channel studies have demonstrated that hydrogen ions (pH 6.4) interact directly with VR1 to induce capsazepine-sensitive sustained currents (Tominaga et al. 1998; Jerman et al. 2000). In addition, using site-directed mutational analysis of VR1 Jordt et al. (2000) revealed that protons can interact with specific sites on VR1 to directly open the channel. Therefore, the protons are capable of activating VR1 at the temperature used in our study (35 °C) without any additional stimulus. A prediction of a direct mechanism of action is that the selective VR1 antagonists I-RTX and capsazepine would inhibit acid-induced VR1 activation at the single-channel level in isolated membrane patches.

Our findings that virtually all nodose Aδ fibres responded to citric acid and that jugular C-fibres responded to rapid application of citric acid by a mechanism only marginally inhibited by capsazepine, is inconsistent with the observations of Fox et al. (1995). Using a similar isolated guinea-pig airway preparation, they found that C-fibres, but not Aδ fibres responded to hydrogen ions with action potential discharge. Moreover, they found that the acid-induced C-fibre discharge was nearly abolished by capsazepine. These observations are similar to our findings when the pH over the receptive field was gradually reduced from 7.4 to ≈5.0 (Fig. 4). In this case the Aδ fibres did not respond, probably because of rapid inactivation, and the slowly inactivating response observed in the C-fibres was nearly abolished by capsazepine. It seems likely, therefore, that the experimental design used by Fox et al. (1995) resulted in a more gradual decline in pH over the receptive field, than in our studies using administration of 500 μl volume of acidic solution in ≈3 s.

Several studies addressed the role of anion in the response to low pH, the lactate anion drawing particular interest because of its accumulation in various pathological conditions (Stahl & Longhurst, 1992; Hong et al. 1997; Pan et al. 1999). However, the observation that sodium citrate did not elicit activation of airway afferents, the finding that stimulation by 1 mm citric acid was mimicked by the hydrochloric acid of the same pH indicates that citrate anion played little role in the airway nerves response to citric acid.

Inhalation challenge with large concentrations of citric acid is commonly used to investigate the cough reflex (Tatar et al. 1997). The role of RARs in cough is well established (Widdicombe, 1998), but the role of bronchial C-fibres is still debated (Fox, 1996; Karlsson & Fuller, 1999). The vascular and/or bronchoconstrictor effects of tachykinins released upon C-fibres activation may indirectly affect RARs activity and thus contribute to cough induced by various C-fibre stimuli including citric acid (Joad et al. 1997). Our finding that solutions of low pH directly stimulate RAR-like receptors provides another mechanism by which citric acid can cause cough. However, caution should be used while interpolating results from in vitro experiments to cough studies. Paradoxically, though RAR-like receptors were more sensitive to low pH-induced activation (pH of 6.7 was sufficient to activate all RAR-like receptors tested), rapid inactivation of their response may prevent them from being activated by protons during inhalation of acidic solutions. The rate of pH change in airway mucosa during aerosol deposition would be difficult to measure, but it seems reasonable to assume that it is slower when the pH of inhaled solution is higher. As a consequence, RAR-like receptor responses to small concentrations of citric acid may be inactivated without producing sufficient signal to initiate cough. Nevertheless, the change of pH generated by large concentrations of citric acid is likely to activate RAR-like receptors directly.

In guinea-pigs, capsazepine was found to inhibit cough evoked by 0.25 but not 0.5 m citric acid (Lalloo et al. 1995) and essentially the same results were obtained using ruthenium red (Bolser et al. 1991). It was hypothesized that 0.5 m citric acid is near the top of a dose-response curve, such that the antagonism was surmounted. Our results provide another explanation for the inability of VR1 antagonists to inhibit the cough response to larger concentrations of citric acid. The larger concentration of acid may have resulted in hydrogen ions accumulating at the receptive fields at a rate sufficient for direct RAR activation. Indeed in dogs cough induced by inhalation of citric acid into the tracheobronchial region was abolished by cooling the vagus to 6 °C, a manoeuvre considered to block conduction in A class fibres that include RAR-like receptors, but not C-fibres (Tatar et al. 1994). Interestingly, in healthy humans no correlation was found between cough thresholds for citric acid and capsaicin (Wong et al. 1999), suggesting that a VR1-independent mechanism is involved.

In summary, the data indicate that both the magnitude and rate of pH change are important variables in acid-induced airway sensory nerve activation. Conditions leading to a gradual and sustained reduction in pH will probably lead to activation of only nociceptive-type fibres, whereas conditions leading to a rapid and transient drop in pH may activate both RAR-like low-threshold mechanosensors and nociceptors. These findings may have relevance to reflex changes that may occur in disorders in which airway pH decreases such as airway inflammation, sleep apnea and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The results are also pertinent to the study of reflexes induced by inhalation of acidic solutions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Ms Sonya Meeker for her outstanding technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

References

- Alvarez De La Rosa D, Zhang P, Shao D, White F, Canessa CM. Functional implications of the localization and activity of acid-sensitive channels in rat peripheral nervous system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2002;99:2326–2331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042688199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson SE, Lexmuller K, Johansson A, Ekstrom GM. Tissue and intracellular pH in normal periarticular soft tissue and during different phases of antigen induced arthritis in the rat. Journal of Rheumatology. 1999;26:2018–2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson CJ, Xie J, Wemmie JA, Price MP, Henss JM, Welsh MJ, Snyder PM. Heteromultimers of DEG/ENaC subunits form H+-gated channels in mouse sensory neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2002;99:2338–2343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032678399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger KI, Ayappa I, Sorkin IB, Norman RG, Rapoport DM, Goldring RM. CO2 homeostasis during periodic breathing in obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2000;88:257–264. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolser DC, AziZ SM, Chapman RW. Ruthenium Red decreases capsaicin and citric acid-induced cough in guinea pigs. Neuroscience Letters. 1991;126:131–133. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90536-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning BJ, Undem BJ. Evidence that distinct neural pathways mediate parasympathetic contractions and relaxations of guinea-pig trachealis. Journal of Physiology. 1993;471:25–40. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr MJ, Gover TD, Weinreich D, Undem BJ. Inhibition of mechanical activation of guinea-pig airway afferent neurons by amiloride analogues. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2001;133:1255–1262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr MJ, Undem BJ. Ion channels in airway afferent neurons. Respiration Physiology. 2001;125:83–97. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-ZeitZ KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates EL, Knuth SL, Bartlett D., Jr Laryngeal CO2 receptors: influence of systemic PCO2 and carbonic anhydrase inhibition. Respiratory Physiology. 1996;104:53–61. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(96)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoui S, Cognon C, Naline E, Emonds-Alt X, Advenier C. Involvement of tachykinin NK3 receptors in citric acid-induced cough and bronchial responses in guinea pigs. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;158:42–48. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9705052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg K, Karlsson JA, Theodorsson E, Lundberg JM, Persson CG. Cough and bronchoconstriction mediated by capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons in the guinea-pig. Pulmonary Pharmacology. 1988;1:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(88)90008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AJ. Modulation of cough and airway sensory fibres. Pulmonary Pharmacology. 1996;9:335–342. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1996.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AJ, Urban L, Barnes PJ, Dray A. Effects of capsazepine against capsaicin- and proton-evoked excitation of single airway C-fibres and vagus nerve from the guinea-pig. Neuroscience. 1995;67:741–752. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00115-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Anoveros J, Samad TA, Woolf CJ, Corey DP. Transport and localization of the DEG/ENaC ion channel BNaC1α to peripheral mechanosensory terminals of dorsal root ganglia neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:2678–2686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02678.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Lee LY. Alveolar hypercapnia augments pulmonary C-fiber responses to chemical stimulants: role of hydrogen ion. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2002;93:181–188. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00062.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HÄbler C. Über den K+- und Ca++ - Gehalt von Eiter und Exsudaten und seine Beziehungen zum Entzündungsschmerz. Klinische Wochenschrift. 1929;8:1569–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Hong JL, Kwong K, Lee LY. Stimulation of pulmonary C fibres by lactic acid in rats: contributions of H+ and lactate ions. Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:319–329. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JF, Fang K, Malik R, Snyder A, Malhotra N, Platts-Mills TA, Gaston B. Endogenous airway acidification. Implications for asthma pathophysiology. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000;161:694–699. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9911005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SW, Cho H, Kwak J, Lee SY, Kang CJ, Jung J, Cho S, Min KH, Suh YG, Kim D, Oh U. Direct activation of capsaicin receptors by products of lipoxygenases: endogenous capsaicin-like substances. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2000;97:6155–6160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerman JC, Brough SJ, Prinjha R, Harries MH, Davis JB, Smart D. Characterization using FLIPR of rat vanilloid receptor (rVR1) pharmacology. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;130:916–922. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joad JP, Kott KS, Bonham AC. Nitric oxide contributes to substance P-induced increases in lung rapidly adapting receptor activity in guinea-pigs. Journal of Physiology. 1997;503:635–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.635bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordt SE, Tominaga M, Julius D. Acid potentiation of the capsaicin receptor determined by a key extracellular site. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2000;97:8134–8139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100129497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajekar R, Proud D, Myers AC, Meeker SN, Undem BJ. Characterization of vagal afferent subtypes stimulated by bradykinin in guinea pig trachea. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1999;289:682–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson JA, Fuller RW. Pharmacological regulation of the cough reflex - from experimental models to antitussive effects in man. Pulmonary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1999;12:215–228. doi: 10.1006/pupt.1999.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton GC, Larrabee MG. A unitary analysis of pulmonary volume receptors. American Journal of Physiology. 1946;147:100–114. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1946.147.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalloo UG, Fox AJ, Belvisi MG, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Capsazepine inhibits cough induced by capsaicin and citric acid but not by hypertonic saline in guinea pigs. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1995;79:1082–1087. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.4.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry RH, Wood AM, Higenbottam TW. Effects of pH and osmolarity on aerosol-induced cough in normal volunteers. Clinical Science. 1988;74:373–376. doi: 10.1042/cs0740373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlexander MA, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Adaptation of guinea-pig vagal airway afferent neurones to mechanical stimulation. Journal of Physiology. 1999;521:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nault MA, Vincent SG, Fisher JT. Mechanisms of capsaicin- and lactic acid-induced bronchoconstriction in the newborn dog. Journal of Physiology. 1999;515:567–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.567ac.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan HL, Longhurst JC, Eisenach JC, Chen SR. Role of protons in activation of cardiac sympathetic C-fibre afferents during ischaemia in cats. Journal of Physiology. 1999;518:857–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0857p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen KE, Meeker SN, Riccio MM, Undem BJ. Selective stimulation of jugular ganglion afferent neurons in guinea pig airways by hypertonic saline. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1998;84:499–506. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardolo FL, Rado V, Fabbri LM, Sterk PJ, Di Maria GU, Geppetti P. Bronchoconstriction induced by citric acid inhalation in guinea pigs: role of tachykinins, bradykinin, and nitric oxide. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999;159:557–562. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9804022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio MM, Kummer W, Biglari B, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Interganglionic segregation of distinct vagal afferent fibre phenotypes in guinea-pig airways. Journal of Physiology. 1996a;496:521–530. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio MM, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Immunomodulation of afferent neurons in guinea-pig isolated airway. Journal of Physiology. 1996b;491:499–509. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant Ambrogio G, Widdicombe J. Reflexes from airway rapidly adapting receptors. Respiration Physiology. 2001;125:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh H, Lou YP, Lundberg JM. Inhibitory effects of capsazepine and SR 48968 on citric acid-induced bronchoconstriction in guinea-pigs. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;236:367–372. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90473-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart D, Jerman JC, Gunthorpe MJ, Brough SJ, Ranson J, Cairns W, Hayes PD, Randall AD, Davis JB. Characterisation using FLIPR of human vanilloid VR1 receptor pharmacology. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2001;417:51–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00901-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl GL, Longhurst JC. Ischemically sensitive visceral afferents: importance of H+ derived from lactic acid and hypercapnia. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:H748–753. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.3.H748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland SP, Benson CJ, Adelman JP, McCleskey EW. Acid-sensing ion channel 3 matches the acid-gated current in cardiac ischemia-sensing neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2001;98:711–716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M, Pecova R, Karcolova D. Sensitivity of the cough reflex in awake guinea pigs, rats and rabbits. Bratislava Medical Journal. 1997;98:539–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M, Sant Ambrogio G, Sant Ambrogio FB. Laryngeal and tracheobronchial cough in anesthetized dogs. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994;76:2672–2679. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.6.2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undem BJ, Pickett WC, Lichtenstein LM, Adams GK., III The effect of indomethacin on immunologic release of histamine and sulfidopeptide leukotrienes from human bronchus and lung parenchyma. American Review of Respiratory Diseases. 1987;136:1183–1187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.5.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban L, Dray A. Capsazepine, a novel capsaicin antagonist, selectively antagonises the effects of capsaicin in the mouse spinal cord in vitro. Neuroscience Letters. 1991;134:9–11. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90496-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl P, Foged C, Tullin S, Thomsen C. Iodo-resiniferatoxin, a new potent vanilloid receptor antagonist. Molecular Pharmacology. 2001;59:9–15. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Champigny G, Lingueglia E, De Weille JR, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. H(+)-gated cation channels. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;868:67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZH, Bradford A, O'Regan RG. Effects of CO2 and H+ on laryngeal receptor activity in the perfused larynx in anaesthetized cats. Journal of Physiology. 1999;519:591–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0591m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe JG. Afferent receptors in the airways and cough. Respiration Physiology. 1998;114:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(98)00076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CH, Matai R, Morice AH. Cough induced by low pH. Respiratory Medicine. 1999;93:58–61. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(99)90078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt PM, Petersson J, Andersson DA, Chuang H, Sorgard M, Di Marzo V, Julius D, Hogestatt ED. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]