Abstract

It has been suggested that venous congestion plethysmography (VCP) substantially underestimates microvascular permeability by activation of a veni-arteriolar constrictor mechanism, even when using small (< 25 mmHg) congestion pressure steps. We studied human lower limbs of 18 young healthy volunteers to test whether the congestion pressure step size of the VCP protocol has an influence on the values of the capillary filtration capacity (CFC) and isovolumetric venous pressure (Pvi). Two different dual stage VCP pressure step protocols, with 3 and 10 mmHg steps, were used in randomised order and separated by a transient reduction in congestion pressure. Since lymph flow is known to increase after venous congestion, we also looked to see if changes in the estimated lymph flow (JvL) occur as a result of these VCP protocols. The measured CFC (median [25th; 75th percentile]) was 2.6 [2.5; 3.2] × 10−3 ml (100 ml)−1 min−1 mmHg−1 with the 3 mmHg pressure step protocol, which was not different from the value of 2.9 [2.7; 3.4] × 10−3 ml (100 ml)−1 min−1 mmHg−1 obtained with 10 mmHg pressure steps. However, when either of these step sizes was applied after a transient venous decongestion, significantly higher values of CFC, 4.0 [3.4; 4.1] × 10−3 and 3.5 [3.1; 4.5] × 10−3 ml (100 ml)−1 min−1 mmHg−1, respectively, were obtained (P < 0.05). The assessment of Pvi was also independent of the pressure protocol (10 mmHg: 8.0 [5.7; 13.2] mmHg and 3 mmHg: 15.7 [12.5; 18.5] mmHg), but when Pvi was measured after the transient deflation, significantly higher values were found with both 10 and 3 mmHg steps (24.1 [20.9; 27.3] and 30.4 [28.9; 30.9] mmHg, respectively; P < 0.01). The transient pressure reduction was associated with a rise in estimated JvL from 0.04 [0.03; 0.05] to 0.12 [0.08; 0.18] and 0.04 [0.04; 0.05] to 0.09 [0.07; 0.10] ml (100 ml)−1 min−1, respectively (P < 0.01). The first stage data from these protocols shows that the value of CFC is not influenced by the size of the cumulative venous pressure steps, providing they are of 10 mmHg or less. The data also show that JvL can be estimated with small step VCP protocols. We hypothesise that the sudden reduction in cuff pressure after venous congestion is associated with a temporary upregulation of lymph flow. As the congestion pressure is raised again, there is a modulation of the enhanced lymph flow, such that the resulting CFC slope appears greater than that obtained in the first stage of the protocol.

Venous congestion plethysmography (VCP) is a non-invasive method for assessing changes in microvascular permeability (Gamble et al. 1993; Lewis et al. 1998; Christ et al. 2000; Gamble et al. 2000a; Brown et al. 2001; Schurmann et al. 2001). With the VCP technique, congestion cuff-induced elevations of venous pressure cause an increase of limb volume, resulting from a change in both vascular volume and fluid filtration (Gamble et al. 1993). VCP enables the measurement of capillary filtration capacity (CFC), an index of microvascular permeability, and of isovolumetric venous pressure (Pvi). Pvi is the venous congestion pressure that needs to be exceeded to generate a limb volume change due to a net increase in microvascular fluid filtration (Gamble et al. 1993).

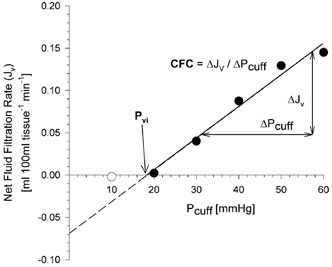

CFC and Pvi are deduced from the relationship between a series of applied cuff pressures and the resulting volume changes (Gamble et al. 1993; Fig. 1). Henriksen & Sejrsen (1977) described a mechanism of arteriolar vasoconstriction following a rapid increase in venous pressure and showed that this, so called, veni-arteriolar reflex is locally mediated. It is widely accepted that this mechanism is triggered by an elevation of venous pressure of more than 25 mmHg (Mellander et al. 1964; Michel & Moyses, 1987). By contrast, Gamble et al. (1993) showed that venous pressure can be raised to 70 mmHg without activating the veni-arteriolar vasoconstriction if small (≤ 10 mmHg) cumulative pressure steps are applied. This observation formed the basis for the measurement of CFC with a multiple, cumulative, step protocol. However, Lundvall & Länne (1989) reported 10-fold higher CFC values using VCP with a protocol of cuff pressure steps ≤ 3 mmHg. The authors explained their different findings by hypothesising that pressure steps of more than 3 mmHg trigger the veni-arteriolar reflex, thus reducing arterial inflow to the limb under investigation.

Figure 1. The relationship between the values of cuff pressure (Pcuff) and corresponding net fluid filtration rate (Jv), that were found in one study.

The regression line is based on the data obtained above the pressure at which the first Jv component was observed (filled circles only). The slope of the linear regression represents the capillary filtration capacity (CFC), the intercept with the x-axis gives the value of the isovolumetric venous pressure (Pvi).

This hypothesis contrasts markedly with observations made using the cumulative small congestion pressure steps protocol, showing that limb arterial inflow remained unchanged up to pressures as great as arterial diastolic pressure (Gamble et al. 1998). The current study addressed these varying findings of CFC values in human limbs by applying two VCP pressure step protocols with 3 and 10 mmHg steps, used in random order but separated by a transient partial decongestion to 30 mmHg.

Moreover, we used the two VCP protocols to investigate whether the CFC slope might provide an index of changes in calculated lymph flow, resulting from the elevation of venous pressure and transient partial decongestion. It has been suggested that under steady state conditions, approximately 10 % of filtered fluid is drained by the lymphatic system (Aukland & Reed, 1993). However, whilst lymph flow is decreased during venous congestion, it was found to be substantially increased following its release (Olszewski et al. 1977a); it was also increased by orthostasis (Olszewski et al. 1977b) and other conditions engendering hyperfiltration (Mullins et al. 1987; Aukland & Reed, 1993). Whilst previous VCP studies have not attempted to measure changes in lymphatic drainage, the possibility of such an assessment has been subjected to theoretical examination by Michel (1989). Michel reasoned that extrapolation of the relation between applied pressure and fluid filtration, to the venous pressure equivalent to the capillary pressure, at which net fluid flux across the microvascular barrier is zero, might give a value reflecting steady state lymph flow (JvL). We hypothesised that since a prior sequence of congestion and decongestion might have a profound influence on lymph flux, it could alter the measured values of net filtration in consecutive but contiguous protocols. We used this reasoning to see if the value of JvL changed after repeated applications of venous pressure increases and if the observed changes were influenced by the size of the applied cuff pressure steps.

METHODS

Subjects

Computer-assisted venous congestion plethysmography was used for the non-invasive assessment of fluid filtration in the calves of 18 young and healthy volunteers (six females, age: 20 to 30 years). All subjects gave verbal informed consent to the procedures, which were approved by the local ethical committee. The subjects were asked to refrain from smoking and drinking caffeine- or alcohol-containing beverages for a minimum of 4 h before the study. During the investigations, which were performed in a quiet, temperature-controlled room (23-25 °C), subjects rested supine on a bed. Legs were supported on an evacuable mattress, with calves positioned at the level of the right atrium, estimated as being one-third of the distance from the sternal angle to the surface of the supporting bench. This arrangement avoided artefacts due to movement or external pressure on the calf, and also prevented the application of additional hydrostatic pressure to the limb vessels. Subjects equilibrated, for at least 20 min before the study.

Venous congestion plethysmography

The use of VCP for the non-invasive assessment of capillary filtration capacity (CFC) and isovolumetric venous pressure (Pvi) has been described in detail elsewhere (Gamble et al. 1993). Briefly, a congestion cuff was placed around the thigh and attached to a compressor pump. Small, 3 or 10 mmHg, cumulative pressure steps were applied, each of 3–5 min duration. Signals reflecting both the pressure and volume changes were recorded continuously for subsequent off-line analysis.

Net fluid filtration was estimated using an electromechanical sensor, positioned around the calf at the site of maximum circumference (filtrass 2001, DOMED Medizintechnik GmbH, Munich, Germany). Filtrass 2001 is a novel mercury-free plethysmograph. This device is calibrated, touch-free, by an inbuilt motor, thus reducing inaccuracy due to manipulation-induced artefacts. Changes in limb circumference are detected using a passive induction transducer with an accuracy of ± 5 μm. Signals reflecting changes in pressure and circumference are sampled at 10 Hz. We recently showed the benefits of this system with respect to the conventional mercury in a Silastic gauge-based system, in terms of reproducibility and accuracy (Christ et al. 2000).

Assessment of capillary filtration capacity (CFC) and isovolumetric venous pressure (Pvi)

We used a modification of the protocol described by Gamble et al. (1993). A series of four to seven cumulative pressure steps, of either 3 or 10 mmHg were applied. Each step was maintained for 3–4 min, sufficient to differentiate between the vascular compliance and filtration components of each response (Gamble et al. 1993). Congestion cuff pressure in excess of the existing venous pressure causes a rapid volume change, attributable to vascular distension. When the pressure exceeds the transmicrovascular equilibrium pressure and the lymphatic drainage capacity, a gradual, sustained increase in limb circumference is observed. This is attributable to net fluid filtration (Jv) from the vascular bed into the interstitium. At pressures greater than Pvi, additional cuff pressure results in increases in Jv. The slope of the linear relationship between Pcuff and Jv represents the capillary filtration capacity (CFC; Gamble et al. 1993). The intercept of the regression line with the x-axis is termed isovolumetric venous pressure (Pvi), the cuff pressure that needs to be exceeded to generate a limb volume change due to fluid filtration (Fig. 1; Gamble et al. 1993).

For the purpose of analysis and the assessment of the values for CFC and Pvi, all records were blinded and analysed independently by different investigators.

Calculation of predicted lymph flow (JvL)

The isovolumetric venous pressure represents the critical pressure above which filtration rate exceeds the steady state lymphatic drainage of fluid from the tissue (Michel, 1989). We assume that the steady state lymph flow remains uninfluenced by the cumulative increases in venous pressure. We also assume that the rate of lymph flow depends on tissue fluid formation which, like the measured Jv, is also governed by Starling forces. The movement of fluid (Jv) between the vascular and interstitial compartment across the area (A) available for fluid filtration can be described by the Starling equation:

| (1) |

where Lp is the hydraulic conductance of the microvascular wall, we assume LpA = CFC (Michel, 1989). Pc and Pi are the hydrostatic pressures in the exchange vessels and the tissue, respectively, and πp and πi are plasma and interstitial colloid osmotic pressures. The other component, σ, is the osmotic reflection coefficient to plasma proteins, which should not change in the absence of an inflammatory challenge. Besides the values of Jv, Pcuff and CFC, the only other components of the Starling equation that have been measured during the course of a venous congestion protocol are Pi and πp. Christ et al. (1997a) found that Pi was −1.0 mmHg, which was not significantly influenced by the application of subdiastolic pressures. In another study, plasma colloid osmotic pressure was found to be unaltered by VCP using small cumulative pressure steps (Christ et al. 1997b). The value for πp, of 25 mmHg, was taken from studies on fit young subjects (Rayman et al. 1994). Whilst we substituted these values in our equation, all other values had to be assumed. Michel, using Starling's theory, suggested that net fluid flux through the microvascular walls would be zero at a capillary pressure of 20–22 mmHg (Michel, 1989). The value for interstitial colloid osmotic pressure, for the first pressure step increases, was assumed to be 15.7 mmHg and the reflection coefficient 0.95 (Levick & Mortimer, 1999). However, we reasoned that a rise in the rate of interstitial fluid removal, by lymphatic pump upregulation, would raise the interstitial fluid concentration in the immediate vicinity of the lymphatic drainage vessels and, therefore, effectively raise the value of interstitial oncotic pressure. Such a change would, of course, be an integral part of the mechanism of continued interstitial fluid removal. Our calculation of its altered value reflected the sum of the assumed steady state value (15.7 mmHg) and the measured increase in the value of Pvi obtained, as a result of the transient partial deflation, in the second part of the inflation protocol. We used these values, along with the values of CFC obtained in each study to estimate lymph flow before and then after a transient period of decongestion.

Study protocols

We tested the hypothesis that the rate of net fluid exchange is not influenced by the size of congestion pressure steps up to 10 mmHg.

Study I

The protocol for this study, which is illustrated in Fig. 2A, was used on 10 subjects (6 females; age: 20 to 30 years; body mass index: 22.5 [20.2; 23.9] kg m−2; mean arterial pressure: 87.5 [80.0; 92.0] mmHg; data are given as median [25th; 75th percentiles]). It comprised a series of 10 mmHg cumulative pressure steps (1stInf10), the maximum pressure being sub-diastolic, each sustained for 4 min. The congestion cuff was then deflated to a value higher than the Pvi (30 mmHg) and this pressure held until a new steady state was achieved. The congestion pressure was then increased by a series of five cumulative 3 mmHg steps up to 45 mmHg (2ndInf3). The pressure cuffs were then deflated, the protocol being complete. Following the off-line analysis, separate calculations of CFC, Pvi and JvL were performed for the two phases of the study.

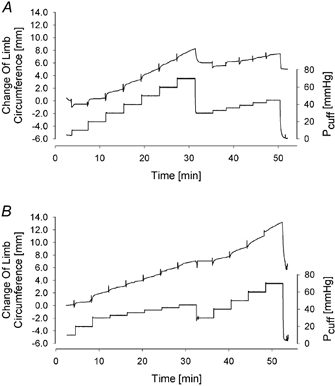

Figure 2. The different pressure protocols used in this VCP study.

The bottom trace, of these original records, depicts the pressure in the congestion cuffs (Pcuff), whereas the top trace represents the volume change. A, in the pressure protocol of Study I first a series of 10 mmHg pressure steps was applied. After intermediate reduction of Pcuff to 30 mmHg the congestion cuff was then re-inflated using cumulative pressure steps of 3 mmHg. B, in Study II the order of the pressure protocols was inverted and the 3 mmHg pressure steps were applied in the first phase of the VCP protocol.

Study II

The protocol for this study was used on eight male volunteers (age: 21 to 29 years; body mass index: 23.4 [22.6; 24.1] kg m−2; mean arterial pressure: 80.0 [73.5; 90.5] mmHg). It examined the effect of reversing the order of pressure steps described in Study I. The cuff pressure was increased to 30 mmHg by three steps of 10 mmHg thereby getting the pressure to a value greater than Pvi. A series of five cumulative 3 mmHg pressure steps (1stInf3) was applied, each of 3–4 min duration, sufficient time to get at least 1 min of steady state filtration. The cuff pressure was then reduced to 30 mmHg and, after reaching a new steady state, the pressure was increased in 10 mmHg steps (2ndInf10) to a maximum of 70 mmHg, or diastolic pressure, if this was less than 70 mmHg (see Fig. 2B). Following the off-line analysis, the values of CFC, Pvi and JvL were calculated for both phases of the study.

Statistical analysis

SigmaStat (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was use for data analysis. All data are given as median [25th; 75th percentiles]. CFC, Pvi and JvL were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test and Mann-Whitney U test. Significance was assumed when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The capillary filtration capacity was not influenced by the size of the pressure steps used in the preliminary inflation protocol. The CFC values obtained with the 10 mmHg pressure protocol (1stInf10: 2.6 [2.5; 3.2] × 10−3 ml (100 ml)−1 min−1 mmHg−1; n = 10) were not significantly different from those obtained with the 3 mmHg cumulative pressure steps (1stInf3: 2.9 [2.7; 3.4] × 10−3 ml (100 ml)−1 min−1 mmHg−1; n = 8). Similarly, after the intermediate reduction of the congestion cuff pressure to 30 mmHg, the values of CFC, measured with the 10 mmHg and 3 mmHg, were not significantly different from one another either (2ndInf10: 4.0 [3.4; 4.1] and 2ndInf3: 3.5 [3.1; 4.5] × 10−3 ml (100 ml)−1 min−1 mmHg−1; n = 8 and 10, respectively). However, whilst there were no step size-dependent differences in the values of CFC, either before or after the intermediate partial deflation, the values obtained before deflation were significantly lower than those obtained after the deflation (P < 0.05).

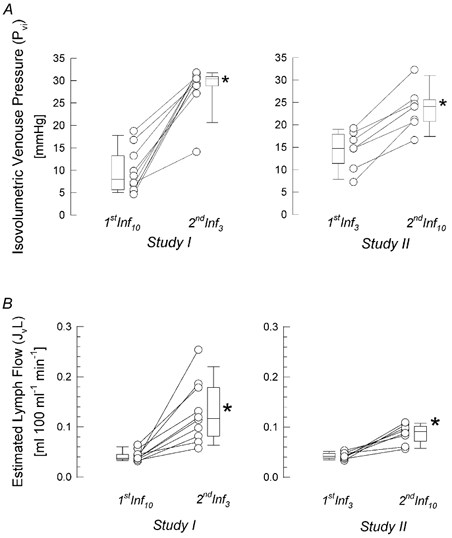

The pressure step size appeared to have no influence on measured values of the isovolumetric venous pressure either before (1stInf10: 8.0 [5.7; 13.2] mmHg; n = 10; and 1stInf3: 15.7 [12.5; 18.5] mmHg; n = 8) or after (2ndInf3: 30.4 [28.9; 30.9] mmHg; and 2ndInf10: 24.1 [20.9; 27.3] mmHg; n = 10 and 8, respectively) the transient deflation stage. In both cases, the differences were not significant. However, it is clear that the transient period of deflation did alter Pvi, for the differences in values obtained before and after the deflation were significant (P < 0.01).

Similarly, the estimated lymph flow (JvL) calculated with eqn (1) was significantly influenced by the deflation manoeuvre (see Fig. 3B). In this respect, the increase in JvL immediately after the transient partial decongestion appeared greater in response to the larger (1stInf10: 0.04 [0.03; 0.05] ml (100 ml)−1 min−1vs. 2ndInf3: 0.12 [0.08; 0.18] ml (100 ml)−1 min−1; P = 0.002) than the smaller deflation step (1stInf3: 0.04 [0.04; 0.05] ml (100 ml)−1 min−1vs. 2ndInf10: 0.09 [0.07; 0.10] ml (100 ml)−1 min−1; P = 0.008).

Figure 3. Changes of the microcirculatory parameters during different VCP protocols.

Individual as well as median [10th, 25th, 75th and 90th percentiles] values of isovolumetric venous pressure and predicted lymph flow are given. A, isovolumetric venous pressure (Pvi) obtained with the different pressure step protocols, before and after intermediate deflation (*P < 0.01; Wilcoxon signed rank test). B, predicted lymph flow (JvL) assessed subsequently with either 3 mmHg or 10 mmHg pressure steps (*P < 0.01; Wilcoxon signed rank test).

The individual and median and percentile values of Pvi and JvL are shown in Fig. 3A and B.

Discussion

We have found that, when using venous congestion plethysmography, cumulative pressure steps of both 3 and 10 mmHg give estimates of capillary filtration capacity that are not significantly different from one another. We also found that when a pressure protocol is applied, after a period of venous congestion including a transient partial cuff deflation procedure, the subsequent assessment of the rate of net fluid filtration across the microvascular bed showed that it was altered.

Influence of congestion pressure step size on the estimation of vascular permeability

In 1977, Henriksen & Sejrsen described a locally mediated reflex, which reduced arteriolar blood flow in response to the application of venous congestion pressure. Whilst we were able to repeat these observations, we were also able to show that the use of a protocol comprising small (8-10 mmHg) cumulative pressure steps did not activate this response even up to pressures in excess of the arterial diastolic pressure (Gamble et al. 1993). Hitherto, it had been widely accepted that a rapid increase of venous pressure, by more than 25 mmHg, triggered a vasoconstriction of feeding arterioles, attributable to the local rise of arteriolar resistance dependent upon local sympathetic nerves, but independent of their central connection (Henriksen & Sejrsen, 1977). However, more recent observations have questioned this interpretation (Johnson, 2002; Crandall et al. 2002).

A combined decrease in blood flow and increase in local hydrostatic pressure in the exchange vessels is associated with a local increase in plasma oncotic pressure. The increase in this Starling force will oppose fluid filtration (Rayman et al. 1994; Gamble et al. 1997). Thus, activation of the veni-arteriolar mechanism during VCP could lead to a profound underestimation of microvascular filtration capacity. However, earlier studies showed that the use of a small cumulative pressure protocol, with steps of about 10 mmHg, did not activate the veni-arteriolar vasoconstrictor mechanism (Gamble et al. 1993). It has also been shown that arteriolar resistance decreased in response to the application of small cumulative venous congestion pressure steps, thereby sustaining flow and minimising the change in local oncotic pressure, as venous pressure was increased (Gamble et al. 1998). These observations were taken as supporting evidence that sensory inputs, at the venular end of the vasculature, could influence arteriolar tone in the same microvascular network (Collins et al. 1998; Murrant & Sarelius, 2000).

In their studies Lundvall & Länne (1989) used a protocol involving separate venous congestion pressure steps ranging in size from 1.5 to 45 mmHg. They obtained values of CFC that were up to 10 times higher than the range of 2.6 to 5.6 × 10−3 ml (100 ml)−1 min−1 mmHg−1 described in the present paper, and by other studies on control adult human limbs (Gamble et al. 1993; Mahy et al. 1995; Christ et al. 1997a; Lewis et al. 1998; Christ et al. 1999; Christ et al. 2000; Gamble et al. 2000a; Brown et al. 2001; Schurmann et al. 2001). Lundvall & Länne (1989) suggested that pressure steps larger than 3 mmHg might activate the veni-arteriolar mechanism, resulting in an underestimation of microvascular fluid filtration, a suggestion that is in marked contrast to our experience. Moreover, they obtained high values of fluid filtration at congestion pressures that were probably no greater than the isovolumetric venous pressure, the pressure that needs to be exceeded to achieve any filtration at all. Whilst, to our knowledge, no group has confirmed the results given by Lundvall & Länne (1989), an explanation for these data still needs to be found.

The current studies show that a second stepwise increase in cuff pressure after a transient deflation to 30 mmHg during a venous congestion protocol results in significant increases in both CFC and Pvi, the latter change implying a marked alteration in Starling forces at the microvascular interface. Moreover, these observations indicated that the increases may also be effected by the size of the decongestion step. We propose, that these changes reflect activation of mechanisms regulating interstitial fluid homeostasis, such as upregulation of lymph flow from the tissue. Using the calculation suggested by Michel (1989) for the estimation of lymph flow, JvL, the values obtained in response to the first series of inflations in this study were similar to those described by Michel & Moyses (1987) in their studies on human limbs (Michel, 1989). The values are also within the range reported by Olszewski et al. (1977a), from studies on chronically cannulated lymphatics of the feet of normal subjects. Moreover, the marked increase in the estimated value of JvL is in keeping with the measured increases in lymph flow after venous stasis that were reported by Olszewski et al. (1977a).

We have previously shown that during the course of our cumulative pressure step protocols, the interstitial pressure remains virtually unaltered, providing the arterial diastolic pressure is not exceeded (Christ et al. 1997a). However, the continued filtration into the interstitial compartment will undoubtedly reduce the interstitial oncotic pressure, for there is consensus that, in non-inflamed tissue, the osmotic reflection coefficient of the endothelial barrier remains close to 1.0 (Aukland & Reed, 1993). Moreover, the increase in interstitial hydration will also aid the continued movement of fluid from the interstitial compartment into the initial lymphatics (Aukland & Reed, 1993).

Experimental evidence suggests that the intrinsic contractility of initial lymphatics and collectors is primarily responsible for propelling lymph downstream, with the unidirectional movement being governed by valves (Olszewski & Engeset, 1980). These workers observed a mean lymphatic systolic pressure of 38 mmHg which, in some cases, achieved values as great as 120 mmHg. In their review on interstitial lymphatic control of extracellular volume, Aukland & Reed (1993) highlighted myogenic mechanisms as being the most likely contributors to the upregulation of the frequency and force of the contraction of lymphatic smooth muscle. We hypothesise that the sudden decrease in vascular volume following the large step decrease in pressure would facilitate an acute increase in lymphatic filling, thereby upregulating the myogenic pumping mechanism. We suggest that the increase in Pvi following the deflation manoeuvre may reflect altered interstitial oncotic forces resulting from lymphatic pump upregulation.

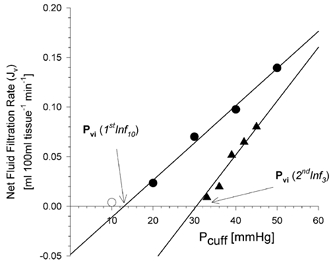

At present, little is known about the magnitude and time course of changes of lymphatic drainage during venous congestion and stasis in man. It has been suggested that a delayed, gradual increase of lymph flow is the common response to venous congestion (Szabo & Magyar, 1967; Aukland & Reed, 1993). However, a steady increase in the lymphatic drainage of the congested limb could not adequately explain the sudden change of limb swelling rate we observed after cuff deflation. Olszewski et al. (1977a) demonstrated that lymph flow from the foot was decreased by 50 %, compared to resting conditions, during the application of a venous congestion pressure of 50 mmHg on the thigh. Moreover, this manoeuvre was followed by a 2-fold increase in lymph flow for the first hour after the deflation of the congestion cuff (Olszewski et al. 1977a). Our data show an increase of lymph flow (JvL) between 125 and 415 % following the transient reduction in cuff pressure. These values are comparable to those of Olszewski et al. (1977a). In venous congestion plethysmography, it is a common observation that, following a congestion protocol, the tissue rapidly returns to its pre-study volume. Furthermore, in control studies, where two identical protocols were followed, separated by a supine resting interval of 30 min, no significant difference in values of CFC and Pvi and therefore JvL were observed (Gamble et al. 2000b). These data certainly support Olszewski's observations that the upregulation of the lymphatic drainage mechanism following the congestion phase of the protocol is short lived. In the light of our results, we hypothesise that the pressure increase following the transient period of decongestion downregulates the enhanced JvL. Figure 4 illustrates this, showing that following the transient period of decongestion to 30 mmHg, the first two pressure steps are not sufficient to trigger reversal of the upregulation mechanism, thereby giving rise to an apparently higher value of CFC when all of these data are entered into the regression calculation. By contrast, a regression slope based on the last three data points would bear a closer parallel to the first inflation (1stInf) regression slope.

Figure 4. The changes of net fluid filtration values (Jv) before (1stInf10, circles) and after (2ndInf3, triangles) the transient deflation of congestion cuffs to 30 mmHg.

After deflation of the cuff, lower net fluid filtration values were found during the second increase in cuff pressure, giving rise to higher Pvi and CFC values.

There may also be other explanations for our findings. Mahy et al. (1995) have shown that, after a cumulative pressure protocol following a deflation step of 42 mmHg, capillary and venous pressures are lower than baseline levels. The authors took this as supporting evidence that pre-capillary vasoconstriction occurs as a result of cuff deflation, thus giving rise to a reduction in blood flow and a lower capillary pressure. Whilst a transient decrease in Jv may result from these changes, this effect may only last for the initial few steps of the remaining pressure steps protocol. Nonetheless, such a change might contribute to the observed apparent increase in CFC. However, it must be stressed that the observations of Mahy et al. (1995) were made in finger nailfold capillaries, which may behave differently from the skeletal muscle microvessels. These differences were apparent in studies by Christ et al. (1997a), who observed a decrease in laser Doppler flux signals in the lower limb during their cumulative pressure increase protocol. These observations contrasted markedly with those of Gamble et al. (1998), who showed that limb blood flow to the calf was sustained during the cumulative pressure protocol. Skeletal muscle forms the bulk of tissue under observation in the present studies.

In conclusion, we have shown that CFC remains uninfluenced by venous congestion plethysmography protocols using either 3 or 10 mmHg pressure steps. Furthermore, we have found altered net fluid filtration rates after a transient deflation during a venous congestion protocol, giving rise to higher measured values of CFC, Pvi and enhanced predicted values of lymph flow (JvL). These data imply that, in the short term, measured values of fluid filtration may be influenced by preceding challenges. We believe that this explanation helps to rationalise the observations of Lundvall & Länne (1989) in the light of those from other workers (Mahy et al. 1995; Gamble et al. 2000a; Brown et al. 2001; Schurmann et al. 2001).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the student volunteers, who generously gave their time. This publication contains parts of the MD thesis of A.B.

References

- Aukland K, Reed RK. Interstitial-lymphatic mechanisms in the control of extracellular fluid volume. Physiological Reviews. 1993;73:1–78. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MD, Jeal S, Bryant J, Gamble J. Modifications of microvascular filtration capacity in human limbs by training and electrical stimulation. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 2001;173:359–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ F, Bauer A, Brugger D, Niklas M, Gartside IB, Gamble J. Description and validation of a novel liquid metal-free device for venous congestion plethysmography. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2000;89:1577–1583. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.4.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ F, Dellian M, Goetz AE, Gamble J, Messmer K. Changes in subcutaneous interstitial fluid pressure, tissue oxygenation, and skin red cell flux during venous congestion plethysmography in men. Microcirculation. 1997a;4:75–81. doi: 10.3109/10739689709148319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ F, Gamble J, Baschnegger H, Gartside IB. Relationship between venous pressure and tissue volume during venous congestion plethysmography in man. Journal of Physiology. 1997b;503:463–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.463bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ F, Gamble J, Raithel P, Steckmeier B, Messmer K. Preoperative changes in fluid filtration capacity in patients undergoing vascular surgery. Anaesthetist. 1999;48:9–18. doi: 10.1007/s001010050662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DM, McCullough WT, Ellsworth ML. Conducted vascular responses: communication across the capillary bed. Microvascular Research. 1998;56:43–53. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1998.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall CG, Shibasaki M, Yen TC. Evidence that the human cutaneous venoarteriolar response is not mediated by adrenergic mechanisms. Journal of Physiology. 2002;538:599–605. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble J, Bethell D, Day NP, Loc PP, Phu NH, Gartside IB, Farrar JF, White NJ. Age-related changes in microvascular permeability: a significant factor in the susceptibility of children to shock? Clinical Science. 2000a;98:211–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble J, Christ F, Gartside IB. Human calf precapillary resistance decreases in response to small cumulative increases in venous congestion pressure. Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:611–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.611bt.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble J, Gartside IB, Christ F. A reassessment of mercury in silastic strain gauge plethysmography for microvascular permeability assessment in man. Journal of Physiology. 1993;464:407–422. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble J, Grewal PS, Gartside IB. Vitamin C modifies the cardiovascular and microvascular responses to cigarette smoke inhalation in man. Clinical Science. 2000b;98:455–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen O, Sejrsen P. Local reflex in microcirculation in human skeletal muscle. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1977;99:19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb10347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JM. How do veins talk to arteries? Journal of Physiology. 2002;538:341. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DM, Tooke JE, Beaman M, Gamble J, Shore AC. Peripheral microvascular parameters in the nephrotic syndrome. Kidney International. 1998;54:1261–1266. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundvall J, Länne T. Much larger transcapillary hydrodynamic conductivity in skeletal muscle and skin of man than previously believed. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1989;136:7–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1989.tb08624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahy IR, Shore AC, Smith LD, Tooke JE. Disturbance of peripheral microvascular function in congestive heart failure secondary to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovascular Research. 1995;30:939–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellander S, Öberg B, Odelram H. Vascular adjustment to increased transmural pressure in cat and man with special reference to shifts in capillary fluid transfer. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1964;61:34–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1964.tb02940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel CC. Microvascular permeability, venous stasis and oedema. International Angiology. 1989;8:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel CC, Moyses C. The measurement of fluid filtration in human limbs. In: Tooke JE, Smaje LH, editors. Clinical Investigation of Microcirculation. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff; 1987. pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins RJ, Powers MR, Bell DR. Albumin and IgG in skin and skeletal muscle after plasmapheresis with saline loading. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;252:H71–79. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.1.H71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrant CL, Sarelius IH. Coupling of muscle metabolism and muscle blood flow in capillary units during contraction. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 2000;168:531–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski WL, Engeset A. Intrinsic contractility of prenodal lymph vessels and lymph flow in human leg. American Journal of Physiology. 1980;239:H775–783. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.239.6.H775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski W, Engeset A, Jaeger PM, Sokolowski J, Theodorsen L. Flow and composition of leg lymph in normal men during venous stasis, muscular activity and local hyperthermia. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1977a;99:149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb10365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski WL, Engeset A, Sokolowski J. Lymph flow and protein in the normal male leg during lying, getting up, and walking. Lymphology. 1977b;10:178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayman G, Williams SA, Gamble J, Tooke JE. A study of factors governing fluid filtration in the diabetic foot. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1994;24:830–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1994.tb02027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurmann M, Zaspel J, Gradl G, Wipfel A, Christ F. Assessment of the peripheral microcirculation using computer-assisted venous congestion plethysmography in post-traumatic complex regional pain syndrome type I. Journal of Vascular Research. 2001;38:453–461. doi: 10.1159/000051078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Magyar Z. Pressure measurements in various parts of the lymphatic system. Acta Medica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 1967;23:237–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]