Abstract

Spinally administered muscarinic receptor agonists or acetylcholinesterase inhibitors can produce effective pain relief. However, the analgesic mechanisms and the site of actions of cholinergic agents in the spinal cord are not fully understood. In this study, we investigated the mechanisms underlying cholinergic presynaptic regulation of glutamate release onto spinal dorsal horn neurons. The role of spinal GABAB receptors in the antinociceptive action of muscarine was also determined. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed on visualized dorsal horn neurons in the lamina II in the spinal cord slice preparation of rats. The miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) and miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) were recorded in the presence of tetrodotoxin. The evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) were obtained by electrical stimulation of the dorsal root entry zone or the attached dorsal root. Nociception in rats was measured using a radiant heat stimulus and the effect of intrathecal administration of drugs tested. Acetylcholine (10–100 μM) reduced the amplitude of monosynaptic eEPSCs in a concentration-dependent manner. Acetylcholine also significantly decreased the frequency of non-NMDA receptor-mediated mEPSCs, which was antagonized by atropine but not mecamylamine. The frequency of GABAA receptor-mediated mIPSCs was significantly increased by acetylcholine and this excitatory effect was abolished by atropine. Existence of presynaptic M2 muscarinic receptors in the spinal dorsal horn was further demonstrated by immunocytochemistry staining and dorsal rhizotomy. CGP55845, a GABAB receptor antagonist, significantly attenuated the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on the frequency of mEPSCs and the amplitude of monosynaptic eEPSCs in lamina II neurons. Furthermore, the antinociceptive action produced by intrathecal muscarine was significantly reduced by CGP55845 pretreatment in rats. Therefore, data from this integrated study provide new information that acetylcholine inhibits the glutamatergic synaptic input to lamina II neurons through presynaptic muscarinic receptors. Inhibition of glutamate release onto lamina II neurons by presynaptic muscarinic and GABAB heteroreceptors in the spinal cord probably contributes to the antinociceptive action of cholinergic agents.

The spinal cholinergic system and muscarinic receptors are important for the regulation of different physiological functions, including nociception. Intrathecal administration of cholinergic muscarinic agonists or acetylcholinesterase inhibitors produces analgesia in both animals and humans (Iwamoto & Marion, 1993; Naguib & Yaksh, 1994; Hood et al. 1997). The precise mechanisms of spinal muscarinic analgesia remain poorly understood. Immunocytochemistry and autoradiography studies have shown that muscarinic receptors in the spinal dorsal horn are concentrated in the superficial laminae of the spinal cord (Hoglund & Baghdoyan, 1997; Yung & Lo, 1997). However, the existence of presynaptic muscarinic receptors and their functional role in modulating synaptic transmission in spinal dorsal horn neurons are not clear. Molecular cloning studies have revealed the existence of five distinct muscarinic receptor subtypes, which are all G protein-coupled receptors (Hulme et al. 1990; Wess, 1996). Importantly, the M2 subtype is the predominant muscarinic receptor in the spinal cord dorsal horn (Hoglund & Baghdoyan, 1997; Yung & Lo, 1997). Recent studies performed in muscarinic receptor knockout mice provide further evidence that the M2 muscarinic receptors play an essential role in cholinergic analgesia (Gomeza et al. 1999).

The neurons in the superficial dorsal horn, especially the lamina II (substantia gelatinosa), receive and process both excitatory and inhibitory inputs from primary afferent nerves, interneurons and nerve terminals projected from neurons in the supraspinal nuclei (De Biasi & Rustioni, 1988; Lekan & Carlton, 1995). Glutamate is a major excitatory neurotransmitter in the spinal cord (De Biasi & Rustioni, 1988; Yoshimura & Jessell, 1990). Inhibition of spinal glutamate release is an important analgesic mechanism of opioids (Kohno et al. 1999). It remains unclear whether presynaptic muscarinic receptors can alter spinal glutamate release. Furthermore, the GABAB receptor and its mRNA have been localized in the spinal cord dorsal horn (Price et al. 1984; Towers et al. 2000). Activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors decreases glutamate release from primary afferent terminals in the spinal cord (Iyadomi et al. 2000). It has been shown that activation of muscarinic receptors increases GABA release in the spinal dorsal horn (Baba et al. 1998). Since endogenously released GABA in the spinal cord can preferentially activate presynaptic GABAB receptors (Chery & De Koninck, 2000), it is possible that increased GABA release following activation of muscarinic receptors may attenuate spinal glutamate release indirectly through presynaptic GABAB receptors. In the present study, we performed a series of experiments to investigate the mechanisms of cholinergic regulation of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs to spinal lamina II neurons. The functional significance of spinal GABAB receptors in muscarinic analgesia was also studied.

METHODS

All the surgical preparations and experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Penn State University College of Medicine.

Electrophysiological recordings

Sprague-Dawley rats (5–7 weeks old; Harlan Industries, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were used for the in vitro slice studies. Rats were anaesthetized with 2 % halothane in O2 and the lumbar segment of the spinal cord was rapidly removed through a limited laminectomy, after which the rats were killed by inhalation of 5 % halothane. The segment of lumbar spinal cord was immediately placed in an ice-cold sucrose artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) presaturated with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2. The sucrose aCSF contained (mm): sucrose, 234; KCl, 3.6; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.5; NaH2PO4, 1.2; glucose, 12.0; and NaHCO3, 25.0. The tissue was then placed in a shallow groove formed in a gelatin block and glued on the stage of a vibratome (Technical Product International, St Louis, MO, USA). Transverse spinal cord slices (350 μm) were cut in the ice-cold sucrose aCSF and then preincubated in Krebs solution oxygenated with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2 at 36 °C for at least 1 h before they were transferred to the recording chamber. The Krebs solution contained (mm): NaCl, 117.0; KCl, 3.6; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.5; NaH2PO4, 1.2; glucose, 11.0; and NaHCO3, 25.0. Recordings of postsynaptic currents were performed using the whole-cell voltage-clamp method, as we described previously (Pan et al. 2002). The lamina II has a distinct translucent appearance and can easily be distinguished under the microscope. In this study, special efforts were made to record neurons in the outer zone of lamina II since this region mainly receives the IB4-positive C-fibre afferent input (Woodbury et al. 2000). We have observed that the distance between the outer layer of lamina II and the dorsal edge of the white matter is 130–150 μm in spinal cord slices of 5- to 7-week-old rats (Pan et al. 2002). The neurons located in the dorsal one-third of lamina II in the spinal slice were identified under a fixed stage microscope (BX50WI, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with differential interference contrast/infrared illumination. The electrode for the whole-cell recordings was triple pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries with a puller (P-97, Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA, USA). The impedance of the pipette was 5–10 MΩ when filled with internal solution containing (mm): potassium gluconate, 135.0; KCl, 5; MgCl2, 2.0; CaCl2, 0.5; Hepes, 5.0; EGTA, 5.0; ATP-Mg, 5.0; Na-GTP, 0.5; and guanosine 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphate) (GDP-β-S), 1; adjusted to pH 7.2–7.4 with 1 m KOH (290–320 mmol l−1). GDP-β-S was added to the internal solution to block the possible postsynaptic effect mediated by cholinergic agonists through G proteins (Baba et al. 1998). The slice was placed in a recording chamber and perfused with Krebs solution at 5.0 ml min−1 maintained at 36 °C by an in-line solution heater and a temperature controller.

Recordings of postsynaptic currents began 5 min later, after whole-cell access was established and the current reached a steady state. The input resistance was monitored and the recording was abandoned if it changed more than 15 % (Li & Pan, 2001; Pan et al. 2002). Signals were recorded using an amplifier (Axopatch 200B, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) at a holding potential of -70 mV, filtered at 1–2 kHz, digitized at 10 kHz, and stored into a Pentium computer with pCLAMP 8.0 (Axon Instruments). All miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) were recorded in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM), bicuculline (10 μM), and strychnine (2 μM). The evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs) were induced by electrical stimulation (0.3 ms, 0.2–0.5 mA and 0.2 Hz) of the dorsal root entry zone or the attached dorsal root through a stimulating electrode connected to a stimulator. Recordings of eEPSCs were similar to mEPSCs except that TTX was not used. Monosynaptic EPSCs were identified based on the constant latency of eEPSCs and the absence of conduction failure of eEPSC in response to a 20 Hz electrical stimulation (Okamoto et al. 2001). We did not determine the conduction velocity of afferents responsible for eliciting eEPSCs in this study since the retained spinal dorsal root was very short in our slice preparation. Based on previous studies using similar techniques, the stimulation intensity used in this study probably stimulated both Aδ- and C-fibre afferents (Okamoto et al. 2001). In some experiments, GABAergic miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) of lamina II neurons were recorded in the presence of TTX (1 μM), CNQX (20 μM) and strychnine (2 μM) at a holding potential of -70 mV (Kohno et al. 1999; Iyadomi et al. 2000). The internal pipette solution for the mIPSCs recording contained (mm): KCl, 140.0; MgCl2, 1.0; CaCl2, 1.0; Hepes, 10.0; ATP-Mg, 5.0; GDP-β-S, 1; and Na-GTP, 0.5 (pH adjusted to 7.2–7.4 with 1 m KOH).

Immunocytochemistry

It has been shown that M2 is the predominant muscarinic subtype producing analgesia in the spinal cord (Hoglund & Baghdoyan, 1997; Yung & Lo, 1997). To determine whether the spinal M2 immunoreactivity is of primary afferent origin, dorsal rhizotomies were performed to deplete the spinal cord of primary afferent terminals. Unilateral dorsal rhizotomies were performed on spinal dorsal roots from L1 to L6 in 8- to 10-week-old rats anaesthetized with 50 mg kg−1 sodium pentobarbitone i.p. Sham operations were performed by exposing the spinal cord without severing the dorsal roots. Postoperatively, the rats were inspected daily for motor activity, signs of infection, and food and water intake, to assess their health condition. In another group of rats, to determine whether M2 receptors are located on the terminals of capsaicin-sensitive primary afferent fibres, resiniferatoxin (RTX, 300 μg kg−1), a neurotoxin for small diameter primary afferents, was injected intraperitoneally to deplete capsaicin-sensitive C-fibre afferents (Ossipov et al. 1999). Five days after surgery or RTX treatment, the rats were anaesthetized with 50 mg kg−1 pentabarbitone i.p. and perfused transcardially with 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by10 % sucrose in 0.1 m PBS. The lumbar spinal segment was removed, sectioned (25 μm) and processed for immunocytochemistry. Briefly, sections were pretreated with 0.2 % H2O2 in PBS to remove the endogenous peroxidase activity. Following incubation with normal goat serum for 60 min to mask nonspecific absorption sites, sections were incubated for 48 h at 4 °C with primary antimuscarinic M2 receptor antisera (1 μg ml−1, a rabbit polyclonal antibody). The M2-specific antibody is raised against the putative third intracellular loop region of M2 receptors and has been characterized for subtype specificity previously (Levey et al. 1995). After rinsing, the sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (1:50, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 60 min at room temperature and overnight at 4 °C. The sections then were transferred to 0.0125 % 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride solution containing 0.0015 % H2O2, mounted on gelatin-coated slides, dried, dehydrated and coverslipped. The immunostaining on the sections was examined under a microscope and the areas of interest were photographed using a digital camera. Control sections for M2 immunostaining were obtained by omission of the primary antibody in the reaction sequence. Sections were imaged using a charge-coupled device camera (Optronics, Goleta, CA, USA) attached to a microscope (BX50, Olympus), and digitized using a computer. The optical density of the immunoreactivity of M2 receptors in the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn was measured by a computer-based imaging analysis program (AIS, Imaging Research Inc., St Catharines, ON, Canada). Measurements were taken from 15–20 coronal sections of the lumbar spinal cord from each animal.

Behavioural assessment of nociception

Four days before testing, adult rats were anaesthetized with 2 % halothane in O2 and implanted with intrathecal catheters for administration of drugs, with the catheter tip positioned at the lumbar spinal level. To determine the sensitivity to noxious heat, rats were placed within Plexiglass enclosures on a transparent glass surface maintained at 30 °C and allowed to acclimate for 30 min. A thermal testing apparatus consisting of a heat-emitting projector lamp and an electronic timer was used (Chen & Pan, 2001). The device was activated after placing the lamp directly beneath the planter surface of the hindpaw. The paw withdrawal latency in response to the radiant heat was recorded by a digital timer. The withdrawal latencies for the left and right paws were averaged and the mean value was used to indicate the sensitivity to noxious heat stimulation. The apparatus was adjusted at the beginning of the study in six rats so that the baseline paw withdrawal latency was approximately 10 s (Chen & Pan, 2001). This setting (i.e. the light beam intensity) was then kept unchanged for the rest of the study. A cut-off of 30 s was used to prevent potential tissue damage. Motor function was evaluated by the placing/stepping reflex and the righting reflex (Chen et al. 2000). The former was evoked by drawing the dorsum of either hindpaw across the edge of the table. The latter was assessed by placing the rat horizontally with its back on the table, which normally gives rise to an immediate, coordinated twisting of the body to an upright position. Changes in motor function were scored as follows: 0, normal; 1, slight deficit; 2, moderate deficit; and 3, severe deficit. Rats were killed with an overdose of sodium pentabarbitone (200 mg kg−1i.p.).

Data analysis

Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. The mEPSCs and mIPSCs were analysed off-line with a peak detection program (MiniAnalysis, Synaptosoft Inc., Leonia, NJ, USA). The cumulative probability of the amplitude and inter-event interval of mEPSCs and mIPSCs were compared by the Komogorov-Smirnov test, which estimates the probability that two cumulative distributions are similar. Analyses of the effects of drugs on the amplitude of eEPSCs were performed using Clampfit (Axon Instruments). The antinociceptive effect of muscarine was determined by repeat measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test. The effects of drugs on mEPSCs and mIPSCs were determined by the Wilcoxon signed rank test or nonparametric ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis or Friedman) test with Dunn's post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of acetylcholine on glutamate release evoked from primary afferents

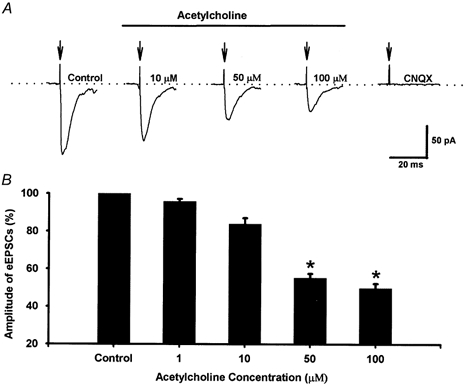

To determine the effect of acetylcholine on glutamate release from afferent terminals to lamina II neurons, the effect of acetylcholine on identified monosynaptic eEPSCs was first studied. The eEPSC was considered to be monosynaptic if the latency was constant following electrical stimulation (Fig. 1A). In identified monosynaptic eEPSCs, neither conduction failure nor an increase in latency occurred when stimulation frequency was increased to 20 Hz, although the amplitude of eEPSCs was markedly attenuated (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the latency of polysynaptic eEPSCs was increased and conduction failure was present when the stimulation frequency was increased to 20 Hz (Fig. 1B). When the recordings were made in the outer zone of lamina II, we observed that more than 70 % of the eEPSCs were monosynaptic. We only tested the effect of acetylcholine on identified monosynaptic EPSCs evoked by stimulation of the dorsal root or dorsal root entry zone. Acetylcholine (10–100 μM) reduced the peak amplitude of monosynaptic eEPSCs in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2). Acetylcholine at 100 μM produced a maximal inhibitory effect on eEPSCs by 51.9 ± 2.4 % of control values in 13 lamina II neurons. The eEPSCs were completely abolished by 20 μM CNQX, a non-NMDA receptor antagonist (Fig. 2), indicating that eEPSCs were mediated by glutamate non-NMDA receptors.

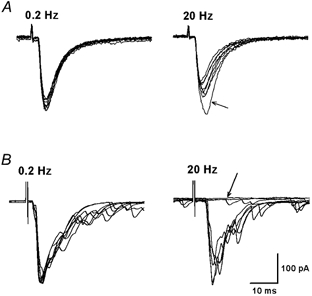

Figure 1. Identification of mono- and polysynaptic EPSCs in lamina II neurons evoked by electrical stimulation of the dorsal root entry zone in spinal cord slices.

A, representative recordings showing monosynaptic eEPSCs in a lamina II neuron elicited at 0.2 and 20 Hz (0.3 ms, 0.4 mA). Note the constant latency and lack of conduction failure when stimulated at 0.2 and 20 Hz. The peak amplitude was reduced after the first eEPSC (indicated by an arrow) during stimulation at 20 Hz. B, polysynaptic eEPSCs in a different lamina II neuron in response to stimulation at 0.2 and 20 Hz (0.3 ms, 0.3 mA). Note the presence of polysynaptic components at 0.2 and 20 Hz. When stimulated at 20 Hz, the latency of eEPSCs was increased and conduction failure was revealed (indicated by an arrow). In each panel, 10 consecutive eEPSCs traces were superimposed.

Figure 2. A concentration-dependent effect of acetylcholine on the amplitude of eEPSCs in lamina II neurons.

A, original recordings of eEPSCs of a lamina II neuron during control conditions and with application of different concentrations of acetylcholine. These traces are averages of 8 consecutive responses. The stimulus artifacts are indicated by the arrows. B, summary data showing the effect of acetylcholine on the peak amplitude of eEPSCs in 14 lamina II neurons. *P < 0.05 compared to the control (Friedman ANOVA test with Dunn's post hoc test).

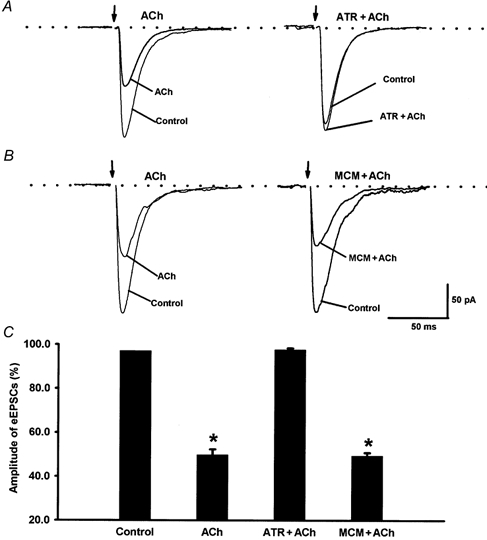

To investigate which type of cholinergic receptor was responsible for the action of acetylcholine on eEPSCs, a muscarinic receptor antagonist, atropine, and a nicotinic receptor antagonist, mecamylamine, were used. In the presence of 10 μM atropine, 100 μM acetylcholine failed to decrease the amplitude of monosynaptic eEPSCs in seven lamina II neurons (Fig. 3). However, 10 μM mecamylamine had no effect on acetylcholine-induced reduction in the peak amplitude of eEPSCs in six separate lamina II neurons (Fig. 3). These data suggest that acetylcholine probably inhibits glutamate release from primary afferent terminals through activation of spinal muscarinic receptors.

Figure 3. Effect of mecamylamine and atropine on acetylcholine-induced inhibition of eEPSCs in lamina II neurons.

A, application of a muscarinic receptor antagonist, atropine (10 μM, ATR) blocked the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine (100 μM, ACh) on the amplitude of eEPSCs in 1 lamina II neuron. B, a nicotinic receptor antagonist, mecamylamine (10 μM, MCM) did not affect acetylcholine-induced inhibition of eEPSCs in 1 neuron. C, summary data showing the effect of acetylcholine and atropine or mecamylamine on the peak amplitude of eEPSCs in 7 lamina II neurons. *P < 0.05 compared to the control (Friedman ANOVA test with Dunn's post hoc test).

Role of presynaptic muscarinic receptors in acetylcholine-induced inhibition of glutamate release

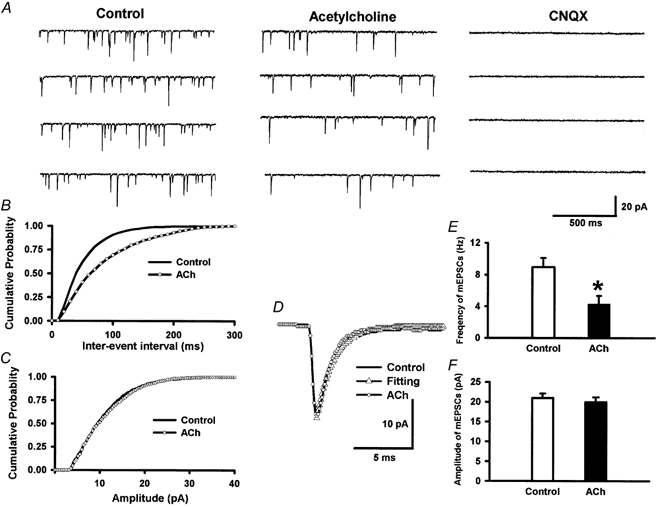

To determine the role of presynaptic muscarinic receptors in the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on glutamate release, mEPSCs, which reflect glutamate quantal release, were recorded from lamina II neurons. The effect of 100 μM acetylcholine on the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs was studied in 14 lamina II neurons (Fig. 4). Acetylcholine significantly decreased the frequency of mEPSCs from 8.96 ± 1.13 to 4.32 ± 0.99 Hz (P < 0.05, Fig. 4) without affecting the amplitude (20.12 ± 1.29 vs. 19.38 ± 1.27 pA) or the decay time constant (1.83 ± 0.14 vs. 1.96 ± 0.15 ms) of mEPSCs. The cumulative probability analysis of mEPSCs before and during acetylcholine application also revealed that the distribution pattern of the inter-event interval shifted towards the right in response to acetylcholine, while the distribution pattern of the amplitude was not significantly altered (Fig. 4). The mEPSCs of lamina II neurons were abolished by CNQX (Fig. 4), indicating that mEPSCs are mediated by glutamate release. Furthermore, atropine (10 μM, n = 7), but not mecamylamine (10 μM, n = 9), abolished the effect of 100 μM acetylcholine on the frequency of mEPSCs (Fig. 5). Atropine or mecamylamine alone had no effect on the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs. These data strongly suggest that presynaptic muscarinic receptors, located on the glutamatergic and/or GABAergic terminals (see below), are involved in the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on glutamate release onto lamina II neurons.

Figure 4. The inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on mEPSCs in lamina II neurons.

A, raw tracings during control conditions, application of acetylcholine (100 μM) and application of CNQX (20 μM). Note that CNQX completely eliminated mEPSCs. B and C, cumulative plot analysis of mEPSCs of the same neuron showing the distribution of the inter-event interval (B) and amplitude (C) during control conditions and acetylcholine application. Acetylcholine increased the inter-event interval of mEPSCs (P < 0.05, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) without changing the distribution of the amplitude. D, superimposed averages of 200 consecutive mEPSCs obtained during control conditions and acetylcholine application. The decay time constant of mEPSCs during control and acetylcholine perfusion was identical, being 1.91 ms. E and F, summary data showing the effect of acetylcholine on the frequency (E) and the amplitude (F) of mEPSCs of 14 lamina II neurons. Data presented as means ± s.e.m.*P < 0.05 compared to the control (Wilcoxon signed rank test).

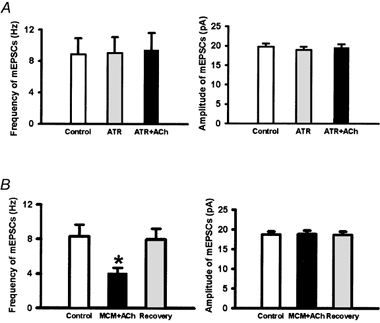

Figure 5. Effect of atropine and mecamylamine on the inhibitory effect of 100 μM acetylcholine on mEPSCs of lamina II neurons.

A, summary data showing the effect of acetylcholine and atropine (10 μM) on the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs of 7 lamina II neurons. B, summary data showing the effect of acetylcholine and mecamylamine (10 μM) on the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs of 9 lamina II neurons. Data presented as means ± s.e.m.*P < 0.05 compared to the control (Wilcoxon signed rank test).

Presynaptic location of muscarinic M2 receptors in spinal cord dorsal horn

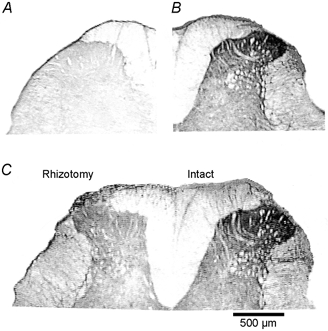

The immunoreactivity of M2 receptors was mainly concentrated in the neuropil of the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn (Fig. 6). Unilateral dorsal rhizotomy caused a dramatic reduction in the immunoreactivity of muscarinic M2 receptors ipsilateral to dorsal rhizotomy in five rats (Fig. 6C). Compared to the intact side, the density of immunoreactivity of M2 receptors in laminae I-III was reduced by 54.2 ± 8.2 % (n = 5 rats). In another five rats treated with RTX, the immunoreactivity of M2 receptors in the dorsal spinal cord also was reduced (by 47.2 ± 9.3 %). These data provide direct evidence that muscarinic M2 receptors are located, at least in part, on the primary afferent terminals in the spinal cord.

Figure 6. Light microscopic view (×200) of M2 immunoreactivity in the spinal cord dorsal horn.

A, a control dorsal spinal cord section (no primary antibody control). B, M2 immunoreactivity was present in the spinal dorsal horn with a high density in the superficial laminae in a sham-operated rat. C, unilateral dorsal rhizotomy (left side) caused a dramatic reduction in M2 receptor immunoreactivity in the superficial laminae of the lumbar spinal cord compared to the intact side.

Role of GABAB receptors in inhibition of glutamate release by acetylcholine

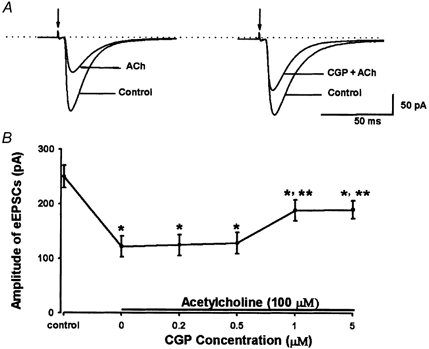

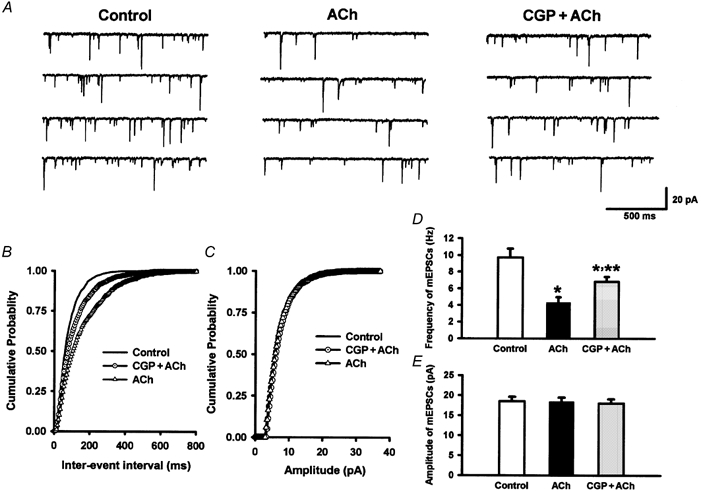

Acetylcholine (100 μM) significantly increased the frequency, but not the amplitude, of GABAergic mIPSCs in six lamina II neurons (Fig. 7). The effect of acetylcholine on mIPSCs was eliminated by atropine (n = 6, Fig. 7). Since the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen reduces glutamate release through a presynaptic mechanism in the spinal cord (Iyadomi et al. 2000), it is possible that acetylcholine may induce GABA release, which, in turn, inhibits glutamate release through presynaptic GABAB receptors. To determine whether GABAB receptors are involved in the cholinergic inhibition of spinal glutamate release, CGP55845, a GABAB receptor antagonist, was used. CGP55845 was selected for this study largely because it is a very specific GABAB antagonist, which has been used in previous studies examining the role of GABAB receptors in the spinal cord (Cui et al. 1998; Riley et al. 2001). Compared to the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on the peak amplitude of monosynaptic eEPSCs (51.6 ± 2.2 %), the effect of acetylcholine on eEPSCs was significantly reversed by 1 μM CGP55845 (24.6 ± 0.5 %, P < 0.05, Fig. 8) in eight lamina II neurons. We found that CGP55845, at 0.2–0.5 μM, did not alter the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on the peak amplitude of monosynaptic eEPSCs (Fig. 8B). When the concentration of CGP55845 was increased to 5 μM, it produced an inhibitory effect similar to what was observed with 1 μM CGP55845 (n = 8, Fig. 8). To investigate further the involvement of presynaptic GABAB receptors in acetylcholine-induced inhibition of glutamate release, the effect of acetylcholine on mEPSCs was examined before and after 1 μM CGP55845 in an additional ten lamina II neurons. The inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on the frequency of mEPSCs (from 9.7 ± 1.1 to 4.3 ± 0.7 Hz, n = 10, P < 0.05) was significantly attenuated by 1 μM CGP55845 (6.8 ± 0.6 Hz, Fig. 9). These data suggest that presynaptic GABAB receptors mediate, in part, the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on glutamate release onto spinal lamina II neurons.

Figure 7. Effect of acetylcholine on GABA-mediated mIPSCs of lamina II neurons.

A, raw tracings during control conditions and application of acetylcholine (100 μM, ACh) in a lamina II neuron. B and D, summary data showing the effect of acetylcholine on the frequency (B) and the amplitude (D) of mIPSCs of 6 lamina II neurons. C and E, atropine (10 μM, ATR) blocked the effect of acetylcholine on mIPSCs in 6 lamina II neurons. The mIPSCs were recorded in the presence of TTX (1 μM), CNQX (20 μM) and strychnine (2 μM). Data presented as means ± s.e.m.*P < 0.05 compared to the control (Wilcoxon signed rank test).

Figure 8. Effect of CGP55845 on the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on eEPSCs in lamina II neurons.

A, original tracings showing attenuation of 100 μM acetylcholine-induced inhibition of eEPSCs by 1 μM CGP55845 in 1 neuron. B, summary data showing the effect of acetylcholine (100 μM) alone and CGP55845 (0.2–5 μM, CGP) plus acetylcholine on the peak amplitude of eEPSCs in 8 lamina II neurons. *P < 0.05 compared to the control; **P < 0.05 compared to acetylcholine alone (Friedman ANOVA test with Dunn's post hoc test).

Figure 9. Effect of CGP55845 on acetylcholine-induced inhibitory effect on mEPSCs in lamina II neurons.

A, original recordings showing mEPSCs during control conditions, application of acetylcholine (100 μM, ACh) and application of CGP55845 (1 μM, CGP) plus acetylcholine in 1 lamina II neuron. B and C, cumulative probability plot showing the distribution of the inter-event interval (B) and amplitude (C) of this neuron during control conditions, application of acetylcholine and application of CGP55845 plus acetylcholine. D and E, summary data showing the modulation by CGP55845 of the effect of acetylcholine on the frequency (D) and amplitude (E) of mEPSCs in 10 lamina II neurons. *P < 0.05 compared to the control; **P < 0.05 compared to acetylcholine alone (Friedman ANOVA test with Dunn's post hoc test).

Role of GABAB receptors in spinal muscarinic analgesia

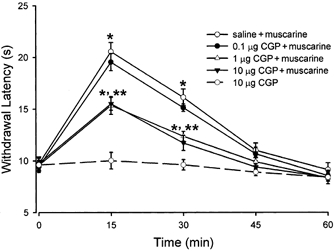

To determine the functional significance of spinal GABAB receptors in muscarinic analgesia, adult rats were treated with intrathecal 0.1 (n = 7), 1 (n = 7) or 10 μg (n = 8) CGP55845 or saline (n = 7) followed after 15 min by 8 μg muscarine. The paw withdrawal latency was determined every 15 min for 1 h after muscarine injection. The doses of muscarine and CGP55845 were selected based on previous studies (Iwamoto & Marion, 1993; Cui et al. 1998; Riley et al. 2001). Drugs for intrathecal injections were dissolved in normal saline and administered in a volume of 5 μl followed by a 10 μl flush with saline. The paw withdrawal latency increased significantly 15 min after intrathecal muscarine injection and this effect lasted for 40–50 min (Fig. 10). Intrathecal 0.1 μg CGP55845 had no significant effect on the antinociceptive action of muscarine. Compared to the vehicle-treated group, pretreatment with CGP55845, at doses of 1 and 10 μg, significantly attenuated the antinociceptive effect of muscarine (Fig. 10). Intrathecal 10 μg CGP55845 alone had no effect on the paw withdrawal latency (Fig. 10). The motor function, evaluated by the placing/stepping reflex and the righting reflex, was not affected by CGP55845 and muscarine. These data indicate that GABAB receptors play an important role in the antinociceptive effect of muscarinic agonists in the spinal cord.

Figure 10. Effect of intrathecal CGP55845 (0.1, 1 and 10 μg, n = 7–8) or saline (n = 7) on the antinociceptive action of intrathecal injection of muscarine (8 μg) in rats.

The nociceptive threshold was determined by the withdrawal response of the hindpaw to a noxious heat stimulus. Data presented as means ± s.e.m.*P < 0.05 compared to the baseline control (time 0); **P < 0.05 compared to the saline-treated group.

Discussion

The cellular mechanisms of cholinergic analgesia in the spinal cord were investigated using several approaches in the present study. The electrophysiology and immunocytochemistry data consistently suggest that acetylcholine is likely to inhibit glutamate release from central terminals of primary afferents through presynaptic muscarinic receptors in the spinal cord. Furthermore, we found that the spinal GABAB receptors play an important role in the inhibitory effect of muscarinic agents on glutamate release and nociception. Therefore, this integrated study provides novel information about the mechanisms of cholinergic modulation of nociception in the spinal cord.

Intrinsic cholinergic innervation has been demonstrated in the spinal cord. For example, neurons and nerve terminals expressing choline acetyltransferase and acetylcholinesterase (enzymes for acetylcholine synthesis and degradation) are located in the spinal cord dorsal horn (Ribeiro-da-Silva & Cuello, 1990; Wetts & Vaughn, 1994). The analgesic effect of intrathecal cholinomimetics is mediated by muscarinic receptors because the analgesic effect of muscarinic agonists and neostigmine was blocked by muscarinic antagonists (Iwamoto & Marion, 1993; Naguib & Yaksh, 1994). Glutamate released from primary afferents is a major excitatory neurotransmitter, which conveys nociceptive information to neurons in the superficial laminae (Yoshimura & Jessell, 1990; Lekan & Carlton, 1995). Because both eEPSCs and mEPSCs recorded from lamina II neurons were completely blocked by CNQX, the EPSCs recorded from this study are mediated by activation of glutamate non-NMDA receptors. There are at least three sources of glutamate release from the presynaptic nerve terminals in the spinal cord. Activation of the central terminals of primary afferents can cause glutamate release (Yoshimura & Jessell, 1990; Yoshimura & Nishi, 1993; Pan et al. 2002). Glutamate is also a neurotransmitter of the descending inhibitory system and spinal interneurons (Headley & Grillner, 1990). We observed that acetylcholine inhibited the amplitude of eEPSCs elicited by stimulation of primary afferents in a dose-dependent manner, and the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on eEPSCs was blocked by atropine but not mecamylamine. Furthermore, acetylcholine significantly decreased the frequency of mEPSCs without affecting the amplitude and kinetics (decay time constant) of mEPSCs of lamina II neurons and this effect was also abolished by atropine. It is generally well accepted that neuromodulator-induced changes in the frequency of mEPSCs indicate a presynaptic locus of action, whereas changes in the amplitude and kinetics of mEPSCs are believed to reflect a postsynaptic site of action (Redman, 1990). Collectively, these results strongly suggest that inhibition of glutamate release to spinal lamina II neurons by acetylcholine is through muscarinic receptors possibly located on primary afferent terminals or interneurons. We were unable to study the role of muscarinic subtype receptors further because highly specific subtype agonists and antagonists for muscarinic receptors are still not available at the present time. The functional involvement of muscarinic subtype receptors in the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on glutamate release remains to be delineated. Since the present study is mainly focused on the isolated presynaptic effect of acetylcholine in regulation of glutamatergic and GABAergic inputs to lamina II neurons, GDP-β-S was included in the electrode internal solution to block the possible postsynaptic effect mediated by cholinergic agonists through G proteins. However, it should be recognized that the postsynaptic muscarinic receptors may also be important for the analgesic effect produced by intrathecal cholinergic agents (Iwamoto & Marion, 1993; Naguib & Yaksh, 1994). It remains to be determined whether activation of muscarinic receptors produces analgesia by inhibition of glutamate release in the spinal cord. The relative importance of pre- and postsynaptic muscarinic receptors in spinal cholinergic analgesia is beyond the scope of the present study and needs to be investigated in future studies.

Previous studies have suggested that M2 is the predominant muscarinic subtype producing analgesia in the spinal cord (Hoglund & Baghdoyan, 1997; Yung & Lo, 1997). In spinal cord tissues from mice deficient in muscarinic subtype receptors, it has been found that M2 is the major subtype receptor that can be detected in the spinal dorsal horn using specific antibodies against muscarinic subtype receptors (A. I. Levey, unpublished observations). Using M2 gene knockout mice, it has been shown that the M2 muscarinic receptor subtype plays a key role in mediating the analgesic action of cholinergic agents (Gomeza et al. 1999). The immunocytochemistry data obtained from the present study provide direct evidence that the M2 receptors exist on the central terminals of primary afferents, because dorsal rhizotomy and RTX treatment markedly reduced M2 immunoreactivity in the dorsal horn. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that the mRNA and protein for M2 subtype receptors are expressed in the dorsal root ganglia neurons (Haberberger et al. 1999; Tata et al. 1999). Thus, these findings are consistent with the electrophysiological data that muscarinic receptors probably mediate the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on glutamate release from primary afferent terminals.

GABAB receptors are densely located in the superficial laminae where nociceptive afferent fibres terminate (Price et al. 1984). The distribution of spinal GABAB receptors correlates well with the location of glutamic acid decarboxylase, where GABA terminals synapse presynaptically with primary afferent terminals and with dendrites of cell bodies within the dorsal horn (Todd & Lochhead, 1990; Waldvogel et al. 1990). Also, primary afferent fibre degeneration by neonatal capsaicin injection decreases GABAB receptor density by 50 %, suggesting that at least this proportion of GABAB receptors in the dorsal spinal cord is presynaptic in origin (Price et al. 1984). It has been shown that GABAB receptors display a greater affinity for GABAB than do GABAA receptors (Yoon & Rothman, 1991; Isaacson et al. 1993). GABA released from synaptic terminals can preferentially activate GABAB receptors in dorsal horn neurons (Chery & De Koninck, 2000). Furthermore, activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors with baclofen inhibits glutamate release onto lamina II neurons (Iyadomi et al. 2000). Thus, presynaptic GABAB receptors may be involved indirectly in muscarinic modulation of glutamate release in the spinal cord. In the present study, we found that acetylcholine significantly increased the frequency but not the amplitude of GABAergic mIPSCs of lamina II neurons, and this was abolished by atropine. Thus, acetylcholine can increase GABA release onto lamina II neurons through presynaptic muscarinic receptors.

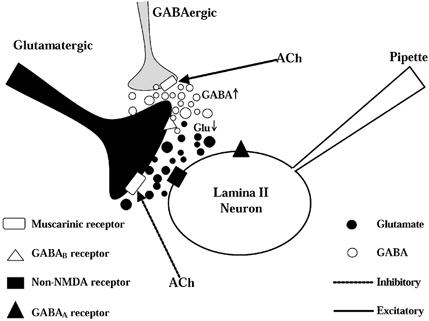

Since the excitatory glutamatergic terminals interdigitate with the inhibitory GABAergic terminals in lamina II, it is likely that the released GABA could spill over sufficiently to activate presynaptic GABAB receptors on the neighbouring glutamatergic terminals to inhibit glutamate release. This possibility is supported by the observation that the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on the amplitude of eEPSCs and the frequency of mEPSCs was significantly attenuated by a specific GABAB receptor antagonist, CGP55845 (Riley et al. 2001). Thus, the present data suggest an additional mechanism by which muscarinic agents inhibit the glutamatergic synaptic input to lamina II neurons through presynaptic GABAB receptors (Fig. 11). Since higher concentrations of CGP55845 did not fully reverse the inhibitory effect of acetylcholine on the amplitude of eEPSCs, it suggests that blocking all GABAB receptors is insufficient to abolish all of the muscarinic effect on glutamate release. To further substantiate the functional significance of spinal GABAB receptors in muscarinic analgesia, the behaviour study was conducted in conscious rats. We observed that pretreatment with CGP55845, but not its vehicle, significantly attenuated the antinociceptive effect produced by intrathecal muscarine. These results clearly indicate that activation of GABAB receptors contributes significantly to the antinociceptive action of spinal muscarinic agonists.

Figure 11. Simplified scheme showing the direct and indirect inhibitory effects of acetylcholine on glutamate release onto lamina II neurons.

Lamina II neurons receive both glutamatergic excitatory and GABAergic inhibitory inputs. Acetylcholine can inhibit glutamate release through presynaptic muscarinic receptors located on the glutamatergic terminals. Also, acetylcholine can activate muscarinic receptors on the GABAergic terminals to evoke synaptic GABA release. Increased GABA can spill over to the neighbouring glutamatergic terminals, which inhibits glutamate release through GABAB receptors located on the glutamatergic nerve terminals. Glu: glutamate.

In summary, this study provides substantial new evidence that presynaptic muscarinic heteroreceptors located on the central terminals of primary afferents and interneurons probably mediate cholinergic inhibition of glutamate release onto lamina II neurons. Cholinergic inhibition of glutamate release is at least partly mediated by GABA release and activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors in the spinal cord. Therefore, presynaptic inhibition of the glutamatergic synaptic input to dorsal horn neurons by muscarinic and GABAB heteroreceptors may constitute one important mechanism by which muscarinic agents produce antinociception in the spinal cord.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Pamela Myers for her secretarial assistance. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants GM64830, HL04199 and NS41178 to H.-L. Pan. H.-L. Pan was a recipient of an Independent Scientist Award supported by the National Institutes of Health during the course of this study.

References

- Baba H, Kohno T, Okamoto M, Goldstein PA, Shimoji K, Yoshimura M. Muscarinic facilitation of GABA release in substantia gelatinosa of the rat spinal dorsal horn. Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:83–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.083br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S-R, Eisenach JC, McCaslin PP, Pan H-L. Synergistic effect between intrathecal non-NMDA antagonist and gabapentin on allodynia induced by spinal nerve ligation in rats. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:500–506. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SR, Pan HL. Spinal endogenous acetylcholine contributes to the analgesic effect of systemic morphine in rats. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:525–530. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200108000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chery N, De Koninck Y. GABAB receptors are the first target of released GABA at lamina I inhibitory synapses in the adult rat spinal cord. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;84:1006–1011. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.2.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui JG, Meyerson BA, Sollevi A, Linderoth B. Effect of spinal cord stimulation on tactile hypersensitivity in mononeuropathic rats is potentiated by simultaneous GABAB and adenosine receptor activation. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;247:183–186. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Biasi S, Rustioni A. Glutamate and substance P coexist in primary afferent terminals in the superficial laminae of spinal cord. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1988;85:7820–7824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomeza J, Shannon H, Kostenis E, Felder C, Zhang L, Brodkin J, Grinberg A, Sheng H, Wess J. Pronounced pharmacologic deficits in M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:1692–1697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberberger R, Henrich M, Couraud JY, Kummer W. Muscarinic M2-receptors in rat thoracic dorsal root ganglia. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;266:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headley PM, Grillner S. Excitatory amino acids and synaptic transmission: the evidence for a physiological function. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1990;11:205–211. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90116-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglund AU, Baghdoyan HA. M2, M3 and M4, but not M1, muscarinic receptor subtypes are present in rat spinal cord. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1997;281:470–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood DD, Mallak KA, James RL, Tuttle R, Eisenach JC. Enhancement of analgesia from systemic opioid in humans by spinal cholinesterase inhibition. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1997;282:86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme EC, Birdsall NJ, Buckley NJ. Muscarinic receptor subtypes. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1990;30:633–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.30.040190.003221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Solis JM, Nicoll RA. Local and diffuse synaptic actions of GABA in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1993;10:165–175. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90308-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto ET, Marion L. Characterization of the antinociception produced by intrathecally administered muscarinic agonists in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1993;266:329–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyadomi M, Iyadomi I, Kumamoto E, Tomokuni K, Yoshimura M. Presynaptic inhibition by baclofen of miniature EPSCs and IPSCs in substantia gelatinosa neurons of the adult rat spinal dorsal horn. Pain. 2000;85:385–393. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno T, Kumamoto E, Higashi H, Shimoji K, Yoshimura M. Actions of opioids on excitatory and inhibitory transmission in substantia gelatinosa of adult rat spinal cord. Journal of Physiology. 1999;518:803–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0803p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekan HA, Carlton SM. Glutamatergic and GABAergic input to rat spinothalamic tract cells in the superficial dorsal horn. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1995;361:417–428. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Edmunds SM, Koliatsos V, Wiley RG, Heilman CJ. Expression of m1-m4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor proteins in rat hippocampus and regulation by cholinergic innervation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:4077–4092. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-04077.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D-P, Pan H-L. Potentiation of glutamatergic synaptic input to supraoptic neurons by presynaptic nicotinic receptors. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;281:R1105–1113. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.4.R1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib M, Yaksh TL. Antinociceptive effects of spinal cholinesterase inhibition and isobolographic analysis of the interaction with mu and alpha2 receptor systems. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:1338–1348. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199406000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Baba H, Goldstein PA, Higashi H, Shimoji K, Yoshimura M. Functional reorganization of sensory pathways in the rat spinal dorsal horn following peripheral nerve injury. Journal of Physiology. 2001;532:241–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0241g.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossipov MH, Bian D, Malan TP, Jr, Lai J, Porreca F. Lack of involvement of capsaicin-sensitive primary afferents in nerve-ligation injury induced tactile allodynia in rats. Pain. 1999;79:127–133. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y-Z, Li D-P, Pan H-L. Inhibition of glutamatergic synaptic input to spinal lamina IIo neurons by presynaptic alpha2-adrenergic receptors. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2002;87:1938–1947. doi: 10.1152/jn.00575.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GW, Wilkin GP, Turnbull MJ, Bowery NG. Are baclofen-sensitive GABAB receptors present on primary afferent terminals of the spinal cord? Nature. 1984;307:71–74. doi: 10.1038/307071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-da-Silva A, Cuello AC. Choline acetyltransferase-immunoreactive profiles are presynaptic to primary sensory fibers in the rat superficial dorsal horn. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;295:370–384. doi: 10.1002/cne.902950303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley RC, Trafton JA, Chi SI, Basbaum AI. Presynaptic regulation of spinal cord tachykinin signaling via GABAB but not GABAA receptor activation. Neuroscience. 2001;103:725–737. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tata AM, Vilaro MT, Agrati C, Biagioni S, Mengod G, Augusti-Tocco G. Expression of muscarinic m2 receptor mRNA in dorsal root ganglia of neonatal rat. Brain Research. 1999;824:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd AJ, Lochhead V. GABA-like immunoreactivity in type I glomeruli of rat substantia gelatinosa. Brain Research. 1990;514:171–174. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90454-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towers S, Princivalle A, Billinton A, Edmunds M, Bettler B, Urban L, Castro-Lopes J, Bowery NG. GABAB receptor protein and mRNA distribution in rat spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12:3201–3210. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldvogel HJ, Faull RL, Jansen KL, Dragunow M, Richards JG, Mohler H, Streit P. GABA, GABA receptors and benzodiazepine receptors in the human spinal cord: an autoradiographic and immunohistochemical study at the light and electron microscopic levels. Neuroscience. 1990;39:361–385. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J. Molecular biology of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Critical Reviews in Neurobiology. 1996;10:69–99. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetts R, Vaughn JE. Choline acetyltransferase and NADPH diaphorase are co-expressed in rat spinal cord neurons. Neuroscience. 1994;63:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodbury CJ, Ritter AM, Koerber HR. On the problem of lamination in the superficial dorsal horn of mammals: a reappraisal of the substantia gelatinosa in postnatal life. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2000;417:88–102. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000131)417:1<88::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon KW, Rothman SM. The modulation of rat hippocampal synaptic conductances by baclofen and γ-aminobutyric acid. Journal of Physiology. 1991;442:377–390. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Jessell T. Amino acid-mediated EPSPs at primary afferent synapses with substantia gelatinosa neurones in the rat spinal cord. Journal of Physiology. 1990;430:315–335. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Nishi S. Blind patch-clamp recordings from substantia gelatinosa neurons in adult rat spinal cord slices: pharmacological properties of synaptic currents. Neuroscience. 1993;53:519–526. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung KK, Lo YL. Immunocytochemical localization of muscarinic m2 receptor in the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;229:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00426-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]