Abstract

We aimed to investigate the interaction between the arterial baroreflex and muscle metaboreflexes (as reflected by alterations in the dynamic responses shown by muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA), mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR)) in humans. In nine healthy subjects (eight male, one female) who performed a sustained 1 min handgrip exercise at 50 % maximal voluntary contraction followed by forearm occlusion, a 5 s period of neck pressure (NP) (30 and 50 mmHg) or neck suction (NS)(-30 and -60 mmHg) was used to evaluate carotid baroreflex function at rest (CON) and during post-exercise muscle ischaemia (PEMI). In PEMI (as compared with CON): (a) the augmentations in MSNA and MAP elicited by 50 mmHg NP were both greater; (b) MSNA seemed to be suppressed by NS for a shorter period, (c) the decrease in MAP elicited by NS was smaller, and (d) MAP recovered to its initial level more quickly after NS. However, the HR responses to NS and NP were not different between PEMI and CON. These results suggest that during muscle metaboreflex activation, the dynamic arterial baroreflex response is modulated, as exemplified by the augmentation of the MSNA response to arterial baroreflex unloading (i.e. NP) and the reduction in the suppression of MSNA induced by baroreceptor stimulation (i.e. NS).

Exercise, particularly isometric exercise, evokes increases in arterial blood pressure and heart rate. This cardiovascular response is hypothesized to be mediated by central command (Rowell et al. 1996) as well as by feedback mechanisms via the afferent nerves (group III and IV fibres) arising from the working skeletal muscles (Mitchell & Schmidt, 1983; Mitchell, 1990; Rowell & O'Leary, 1990) and to be modulated via arterial and cardiopulmonary baroreflexes (Rowell & O'Leary, 1990; Rowell et al. 1996). It has been hypothesized that during heavy exercise, arterial baroreflexes and muscle metaboreflexes are both activated and interact to regulate the blood pressure and HR response (Scherrer et al. 1990; Sheriff et al. 1990; O'Leary, 1993; Nishiyasu et al. 1994a). However, this interaction and its consequences are not fully understood.

Sheriff et al. (1990) demonstrated that the pressor response to graded reductions in hind-limb perfusion (which activates the muscle metaboreflex) was increased by arterial baroreceptor denervation in dogs, suggesting that the arterial baroreflex opposes the pressor effect of the muscle metaboreflex. Nishiyasu et al. (1994a), on the grounds of an increase in cardiac parasympathetic tone when the muscle metaboreflex was evoked by post-exercise muscle ischaemia (PEMI), suggested that the rise in blood pressure that occurs during the muscle metaboreflex might be partly counteracted by the arterial baroreflex. Indeed, the results of previous studies (including Sheriff et al. 1990; Nishiyasu et al. 1994a) suggest that the elevation in blood pressure and enhancement of sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) seen during activation of the muscle metaboreflex are the net result of an interaction between the muscle metaboreflex and the arterial baroreflexes (Scherrer et al. 1990; Sheriff et al. 1990; O'Leary, 1993; Nishiyasu et al. 1994a).

According to Papelier et al. (1997), during PEMI in humans the carotid sinus baroreflex (CBR) showed a reduced sensitivity to loading (sensitivity being expressed as the ratio of the decrease in mean arterial pressure to the increase in carotid sinus pressure), while its sensitivity to unloading was augmented, both without any alteration in the regulation of HR. This finding suggested that the modulation of the SNA components of the CBR that occurs during the muscle metaboreflex might be qualitatively different between the loading and unloading situations. Recently, however, Fadel et al. (2001) reported that the sensitivity of the CBR-muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) relationship (which was expressed as the ratio of the change in MSNA to the change in carotid sinus pressure) was maintained during dynamic arm cycling of moderate intensity. This seemed to suggest that there is no positive or negative modulation of the CBR regulation of SNA during dynamic arm exercise (in which the muscle metaboreflex might be expected to be activated). Finally, Jian et al. (2001) - who estimated overall baroreflex sensitivity (of carotid and aortic baroreflexes together) by measuring the slope of the relationship between MSNA and diastolic blood pressure obtained using vasoactive drugs - showed that during PEMI in humans, baroreflex regulation of MSNA was enhanced even though the sensitivity of the baroreflex modulation of HR was unchanged. However, it is still not certain whether and to what extent: (a) CBR regulation of MSNA is modulated during muscle metaboreflex activation in humans, and (b) dynamic CBR responses - which could be evaluated by examining the time course of the carotid baroreflex-induced alterations in MSNA, MAP and HR - are modulated during activation of the human muscle metaboreflex.

The purpose of this study was to investigate point (b; viz. the hypothesis that dynamic arterial baroreflex responses are modulated during activation of the muscle metaboreflex) and, if so, how the modulation differs between baroreflex loading and unloading. In this study, the muscle metaboreflex was activated by occlusion of the forearm circulation after isometric handgrip exercise (Alam & Smirk, 1937; Nishiyasu et al. 1994b, 1998; Victor et al. 1988). We used the neck chamber technique to load and unload the carotid baroreceptors (by applying 5 s periods of neck suction (NS: -30 and -60 mmHg) or neck pressure (NP: 30 and 50 mmHg), respectively). To evaluate the interaction between the CBR and muscle metaboreflex dynamic responses, we compared the HR, MAP and MSNA responses to NS and NP between two situations (at rest and during PEMI).

Methods

Subjects

We studied nine healthy volunteers (eight men and one woman) with a mean age of 28 ± 2 years, a body weight of 66.5 ± 2.7 kg and a height of 174.0 ± 2.0 cm. The subjects were non-smokers and none was taking any medication. The study was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the University of Tsukuba, and each subject gave informed written consent.

Procedures

After entering the test room, each subject adopted the supine position. He or she then performed a maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) with each hand, using a handgrip dynamometer, to allow us to determine 50 % MVC. After this, the electrodes and cuff were fixed as follows. A rapidly inflatable cuff for arterial occlusion was placed on the upper arm. For MSNA recording, a microelectrode (see below) was inserted manually into the tibial nerve at the popliteal fossa (Saito et al. 1990). After identifying MSNA (see below for criteria), the neck chamber and respiratory mask were fitted. Then a rest period of at least 15 min was allowed before data collection began.

The experimental protocol is illustrated in Fig. 1. The subject was instructed to maintain a constant rate of breathing throughout the experiment, with auditory signals being supplied to assist the subject in controlling breathing frequency at 15 cycles min−1. Carotid baroreflex control of HR, MAP and MSNA was assessed by the use of 5 s periods of neck pressure (30 and 50 mmHg) and neck suction (-30 and -60 mmHg). To minimize the respiratory-related modulation of HR, MAP and MSNA, each neck chamber stimulus (neck pressure and suction) was applied during a voluntary apnoea (breath-hold) at end expiration (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. General experimental protocol (A) and procedure used for application of each neck chamber stimulus (B).

HG, handgrip; NP-NS, neck chamber stimuli (neck pressure and suction).

While the subject was at rest, each level of each neck chamber stimulus was applied. After an interval of about 3 min, the subject performed a 60 s period of isometric handgrip exercise at 50 % MVC with visual feedback of the achieved force through an oscilloscope display. Five seconds before the cessation of the static handgrip, the occlusion cuff was inflated to supersystolic pressure (> 240 mmHg). The cuff remained inflated to produce a 5-6 min period of PEMI and the neck chamber stimuli were applied again, starting more than 30 s after the cessation of exercise. Once all the required neck chamber stimuli had been applied, the cuff was deflated. The same protocol was then performed with the other arm, the order being randomized. In the course of the experiment on a given arm, two sets of neck chamber stimuli (a ‘set’ being as described below) were delivered at rest and again during PEMI.

Neck pressure or suction

A Silastic neck chamber (Sprenkle et al. 1986) was used to load and unload the carotid baroreceptors. The chamber encased the front half of the neck, an airtight seal being made between the mandible and the clavicles and sternum. One part of the chamber was connected to a blower device that could apply either suction or pressure to left and right carotid regions simultaneously. Carotid baroreceptor activity was changed as abruptly as possible by applying 5 s neck pressure (30 or 50 mmHg pressure) or 5 s neck suction (30 or 60 mmHg suction) via the neck chamber. Neck chamber pressure was measured using a pressure transducer mounted on the chamber. One ‘set’ of neck chamber stimuli consisted of four individual stimuli (two levels of NP and two of NS). Each individual stimulus lasted 5 s and the inter-stimulus interval was 30 s. The interval between sets was 30 s. Within each set, the stimuli were always presented in the order NP50, NP30, NS30 and NS60. For the first three subjects, we used a computer-operated system in which changes in chamber pressure were triggered by the first R wave occurring 3 s or more after the beginning of the breath-hold. However, we occasionally detected some electrical noise on the MSNA records when we used this system, so the subsequent experiments were carried out using a manually operated system. We obtained almost the same alterations in HR, MAP and MSNA regardless of the system used. To minimize the respiratory-related modulation of HR, MAP and MSNA, all neck chamber stimuli were delivered during breath-holding. One to two breathing cycles before the beginning of the voluntary apnoea, an investigator signalled to the subject to start breath-holding at the end of the next normal expiration (i.e. without changing the pattern of breathing until the breath-hold itself). The total duration of the voluntary apnoea was 13 s (a 3 s pre-stimulus period, a 5 s stimulus and a 5 s post-stimulus period; Fig. 1B). To assess the effect of the apnoea itself, measurements were repeated during breath-holding but with neck chamber pressure kept at ambient pressure. In each subject, four sets of stimuli (see above) were delivered and four measurements during apnoea alone were made at rest and again during PEMI.

Measurements

HR was monitored via a three-lead electrocardiogram. Beat-to-beat changes in blood pressure were assessed by finger photoplethysmography (Finapres 2300; Ohmeda, USA). The monitoring cuff was placed around the middle finger, with the forearm and hand supported so that the cuff was aligned at heart level. The subject wore a mask connected to a respiratory flowmeter (RF-H; Minato Medical Science, Japan). The analog signals representing the ECG, blood pressure waveforms and respiratory flow were continuously recorded using a FM magnetic tape data recorder (MR-30; TEAC, Japan). The data were also digitized at a sampling frequency of 200 Hz through an analog-digital converter (Maclab/8e; ADInstruments, Australia) for processing by a personal computer (Powerbook 1400C; Apple, Japan) equipped with an on-line data acquisition program. In this way, we collected HR, systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressures and MSNA continuously.

Post-ganglionic muscle sympathetic nerve discharges were recorded by the microneurographic technique. A tungsten microelectrode with a shaft diameter of 0.1 mm and an impedance of 1-5 MΩ was inserted manually by an experimenter into the tibial nerve at the popliteal fossa. After insertion, the electrode was adjusted until MSNA was being recorded. The criteria for MSNA were: spontaneous burst discharges synchronized with the heart beat and enhanced by Valsalva's manoeuvre or apnoea but showing no change in response to cutaneous touch or arousal stimuli (Delius et al. 1972; Valbo et al. 1979; Saito et al. 1990). The neurogram was fed to a differential amplifier, amplified 100 000 times through a band-pass filter (500-3000 Hz). The neurogram was full-wave rectified and integrated by a capacitance-integrated circuit with a time constant of 0.1 s. This integrated MSNA was continuously recorded on an FM magnetic tape data recorder and also digitized with a sampling frequency of 200 Hz through an analog-digital converter for storage on a personal computer (see above). MSNA data were successfully collected in seven of nine subjects and the MSNA data shown here are from those seven subjects (six male, one female).

Data analysis

In a 2-3 min rest period, during which the subjects breathed at a constant rate, MSNA bursts were identified. Then the voltage levels in the periods between bursts were averaged and this level was taken as zero. The largest burst occurring in this rest period was assigned a value of 1000. MSNA data were normalized with respect to this standard in each subject.

To assess the time course of the MSNA responses to neck chamber stimuli (dynamic MSNA response), 13 s sequences of MSNA data (3 s pre-stimulus, 5 s stimulus and 5 s post-stimulus) from four trials at each level of neck pressure or suction were ensemble averaged and, to allow the sequential changes in MSNA to be observed, the averaged MSNA data were displayed at 1 s intervals. For this analysis, the mean voltage neurogram was advanced 1.3 s to allow for the conduction delay between the spinal cord and the recording site (Delius et al. 1972; Fagins & Wallin, 1980). MSNA was found to increase slightly during breath-holding alone. To compensate for this effect, the MSNA responses recorded during four entire periods of breath-holding alone were averaged and the value so obtained was subtracted from the MSNA levels recorded before, during and after each neck chamber stimulus. Hence, the MSNA responses to the neck chamber stimuli are expressed as the change from the MSNA level recorded during breath-holding alone. MSNA bursts occurring during 5 s periods of breath-holding in the absence of any neck chamber stimulus were identified and we then calculated the burst frequency and the mean burst amplitude during each of these periods. The total MSNA activity was obtained as the product of burst frequency and mean burst amplitude for each 5 s period. The total amounts of MSNA activity in all the 5 s periods recorded during control and PEMI (four records in each situation) were averaged separately for each situation and these two calculated values were taken as the baseline MSNA values.

The 13 s records of MAP and HR obtained during four sets of NP-NS trials were averaged and integrated over 1 s periods to allow us to assess the time course of MAP and HR responses. The averaged MAP level during the 3 s pre-stimulus period and the HR at 1 s before the stimulus were taken as the baseline values. MAP and HR responses are expressed as the absolute difference from the baseline value. In addition, the peak changes in MAP and HR were averaged for each type of stimulus and taken as the peak response for each subject.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. For baseline values of HR, MAP and MSNA, and for the peak responses of HR and MAP, comparisons between the control situation and PEMI were made using Student's paired t test. Repeated-measures analysis of variance was performed to compare the time course of HR, MAP and MSNA responses between the control situation and PEMI. Fisher's post hoc test was used to assess group mean differences and also assess differences from the value obtained at 3 s prior to the application of neck chamber stimuli (i.e. 1 s after the start of breath-holding) in control and PEMI. Statistical significance was accepted at a P value of <0.05.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline values of HR, MAP and MSNA obtained in the control situation and during PEMI. During PEMI, MSNA and MAP were higher than in the control, but HR was not different.

Table 1.

Baseline values of HR, MAP and MSNA in control and PEMI situations

| Control | PEMI | |

|---|---|---|

| MSNA total activity (units (5 s)−1) | 842 ± 116 | 1219 ± 201* |

| MAP (mmHg) | 100 ± 1.7 | 114 ± 3.2* |

| HR (beats min−1) | 63 ± 3.5 | 68 ± 4.8 |

Values are means ± s.e.m. MSNA, muscle sympathetic nerve activity (n = 7); MAP, mean arterial pressure (n = 9); PEMI, postexercise muscle ischaemia.

Significant difference from control.

Evoked changes in MSNA

MSNA was increased (transiently) by NP and reduced by NS both in control and during PEMI. However, the time course and the magnitude of the responses differed between these two conditions. In original recordings of the MSNA responses shown by one subject to NP50 and NS60 in the control and during PEMI (Fig. 2), NP induced a larger increment in MSNA during PEMI than in the control. In addition, whereas in the control situation MSNA was depressed for almost the whole 5 s period of NS, during PEMI NS depressed MSNA only very transiently, with a subsequent augmentation of MSNA beginning even during the NS stimulus itself.

Figure 2. MSNA response in one subject to application of +50 mmHg neck pressure (A) and -60 mmHg neck suction (B) during control and post-exercise muscle ischaemia.

The time course of the MSNA response to NP in control and during PEMI is illustrated in Fig. 3. In both control and PEMI, the increment in MSNA evoked by 5 s of NP was very transient, with a decay occurring even while the elevated level of neck chamber pressure was being maintained. Moreover, there was, or tended to be, an undershoot after neck pressure was returned to normal. In the first 1 s of the response to NP50, MSNA was significantly greater during PEMI than in control (Fig. 3A). This was also seen, though less clearly, in the first 1 s of the MSNA response to NP30 (Fig. 3B). Since the MSNA data were advanced by 1.3 s to allow for conduction delays, the timing of this enhanced MSNA response is consistent with a reasonable baroreflex latency and therefore presumably represents a CBR-mediated effect.

Figure 3. Averaged reflex alterations in MSNA elicited by NP50 (A) and NP30 (B) in control and during PEMI.

* Significant difference from the value obtained at 3 s prior to application of neck pressure, P < 0.05. † Significant difference from control, P < 0.05.

The time course of the MSNA responses to NS (Fig. 4) reveals that both in control and during PEMI, MSNA was, or tended to be, reduced (relative to the level immediately before NS) in the first 1-2 s of the time for which NS was applied. Subsequently, the time course of the changes in MSNA differed between control and PEMI, the pattern of change during PEMI being shifted to the left (i.e. occurring earlier), especially in Fig. 4A. Indeed, MSNA was significantly higher during PEMI than in control at 2 and 3 s after the start of NS60 (Fig. 4A) and at 3 s after the start of NS30 (Fig. 4B). This leftward shift in the time course of the MSNA elevation implied that the period of NS-induced MSNA suppression may be shortened during PEMI.

Figure 4. Averaged reflex alterations in MSNA elicited by NS60 (A) and NS30 (B) in control and during PEMI.

* Significant difference from the value obtained at 3 s prior to application of neck suction, P < 0.05. † Significant difference from control, P < 0.05.

Evoked changes in MAP and HR

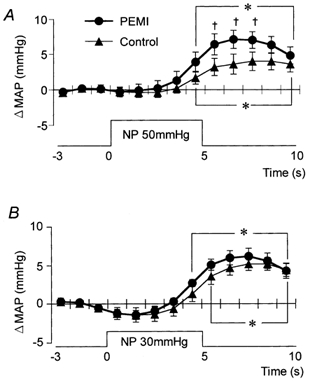

MAP and HR were increased by NP and decreased by NS under both conditions (control and PEMI). Figure 5 shows that at 6-8 s after the start of NP50 (around the time at which the peak MAP responses occurred), MAP was significantly higher during PEMI than in control (Fig. 5A). There were no significant differences between the two conditions in the time course of the MAP responses to NP30 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Averaged reflex alterations in MAP elicited by NP50 (A) and NP30 (B) in control and during PEMI.

* Significant difference from the value obtained at 3 s prior to application of neck pressure, P < 0.05. † Significant difference from control, P < 0.05.

The time course of the MAP responses to NS was significantly different between control and PEMI (Fig. 6). In the first 5 s of the MAP response to NS60 and the first 3 s of that to NS30 there were no significant differences between the two conditions. Thereafter, at 6-10 and 4-10 s after the beginning of NS60 and NS30, respectively, MAP was significantly higher during PEMI than in control (Fig. 6A and B). In addition, the peak MAP response to NS occurred 2-4 s earlier during PEMI than in control.

Figure 6. Averaged reflex alterations in MAP elicited by NS60 (A) and NS30 (B) in control and during PEMI.

* Significant difference from the value obtained at 3 s prior to application of neck suction, P < 0.05. † Significant difference from control, P < 0.05.

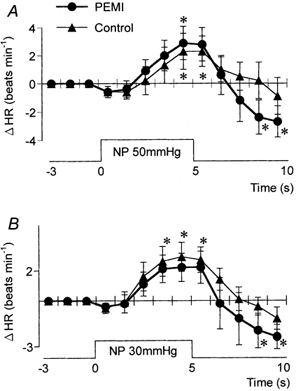

The time course of the HR responses to neck chamber stimuli (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8) was not significantly different between control and PEMI.

Figure 7. Averaged reflex alterations in HR elicited by NP50 (A) and NP30 (B) in control and during PEMI.

* Significant difference from the value obtained at 3 s prior to application of neck pressure, P < 0.05.

Figure 8. Averaged reflex alterations in HR elicited by NS60 (A) and NS30 (B) in control and during PEMI.

* Significant difference from the value obtained at 3 s prior to application of neck suction, P < 0.05.

Table 2 shows the peak MAP and HR responses to each neck chamber stimulus. The peak change in MAP induced by NP50 was significantly greater during PEMI than in control, while NS60 and NS30 each induced a significantly smaller decrease in MAP during PEMI than in control. In contrast, the peak changes in HR induced by NP and NS were not significantly different between control and PEMI.

Table 2.

Peak MAP and HR responses to neck pressure and neck suction in control and PEMI situations

| Neck pressure | Neck suction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP50 | NP30 | NS60 | NS30 | |

| ΔMAP (mmHg) | ||||

| Control | 5.8 ± 0.9 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | −10.5 ± 0.6 | −9.6 ± 1.1 |

| PEMI | 9.0 ± 1.2* | 7.0 ± 0.9 | −8.3 ± 0.9* | −5.6 ± 0.8* |

| ΔHR (beats min−1) | ||||

| Control | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 0.9 | −7.1 ± 1.7 | −3.6 ± 0.9 |

| PEMI | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 1.0 | −6.8 ± 2.0 | −4.4 ± 1.2 |

Values are means ± s.e.m.Δ MAP, change in mean arterial pressure from baseline values. Δ HR, change in heart rate from baseline values. PEMI, post-exercise muscle ischaemia.

Significant difference from control.

Discussion

The major finding made in this investigation was that the dynamic MSNA and MAP responses mediated by the carotid baroreflex, as evaluated by analysing the time course of the response to neck chamber stimuli, were modulated during the PEMI-induced activation of the muscle metaboreflex. In detail, the MSNA augmentation and MAP increment induced by carotid compression was greater during PEMI than at rest. On the other hand, the MSNA elevation that occurred during carotid stretch was shifted to the left (i.e. occurred earlier) during PEMI, suggesting that the period of MSNA suppression induced by carotid stretch may have been shortened. Moreover, MAP decrements induced by carotid stretch were smaller and shorter lasting during PEMI. Thus, our results indicate that the modulation is different between carotid baroreflex loading and unloading. Further, since the modulations did not affect the HR responses to carotid stretch or compression, it would seem to be vascular regulation that is modulated, not the control of heart rate.

In the present study, MAP and MSNA were higher during PEMI than in control (Table 1). According to previous data, the type of exercise employed in this study (1 min periods of 50 % MVC isometric handgrip exercise (HG)) decreases intramuscular pH in the exercising muscles from 7.2 to 6.5 units (Nishiyasu et al. 1994b). This is a large enough decrease in pH to stimulate the chemosensitive afferents (group III and IV fibres) and to increase sympathetic nerve activity, the so-called muscle metaboreflex (Alam & Smirk, 1937; Mitchell & Schmidt, 1983; Mitchell, 1990; Rowell & O'Leary, 1990; Nishiyasu et al. 1994a,b, 1998; Victor et al. 1988). The metabolites produced by HG exercise would be kept in the forearm by the occlusion we applied and so would persistently activate the muscle metaboreflex throughout the PEMI. In this study, MAP was ≈14 mmHg higher than the control level during PEMI, a rise that could load the arterial baroreflex (Scherrer et al. 1990; O'Leary, 1993; Nishiyasu et al. 1994a). Since the arterial baroreflex can counteract the muscle metaboreflex in animals (Sheriff et al. 1990; O'Leary, 1993) and in humans (Scherrer et al. 1990; Nishiyasu et al. 1994a) the elevated blood pressure and enhanced sympathetic nerve activity we observed during the activation of the muscle metaboreflex were presumably the net result of this interaction. However, there has previously been a lack of information about the dynamic characteristics of the arterial baroreflex during activation of the muscle metaboreflex, especially about the arterial baroreflex regulation of MSNA. In this study, we tried to remedy this situation.

The arterial baroreflex is considered to be a feedback arterial blood pressure control mechanism that responds to a change in arterial blood pressure (change in vascular distending pressure in the baroreceptor region) by modulating efferent sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve activity and thus altering systemic blood pressure in the direction opposite to the one giving rise to the input stimulus (Manica & Mark, 1983; Sagawa, 1983; Rowell & O'Leary, 1990). Use of neck suction and pressure, as in the present study, is one of the methods employed to investigate the properties of the carotid sinus baroreflex in humans (Eckberg, 1980; Manica & Mark, 1983; Potts et al. 1993; Raven et al. 1997). The carotid sinus transmural pressure is altered by the change in neck chamber pressure and both loading and unloading of the carotid baroreceptors can be produced non-invasively. The HR and blood pressure responses to these neck chamber stimuli are generally used as indices of carotid sinus baroreflex responsiveness (Eckberg, 1980; Potts et al. 1993; Potts & Raven, 1995; Raven et al. 1997). In addition, the characteristics of the MSNA responses to such stimuli have already been examined and these too are regarded as a useful index of the effectiveness of the reflex (Bath et al. 1981; Wallin & Eckberg, 1982; Eckberg & Wallin, 1987; Rea & Eckberg, 1987; Fritsch et al. 1991; Fadel et al. 2001). A disadvantage of the use of these stimuli is that because the arterial baroreflex is a closed-loop system, the alteration in arterial blood pressure induced by the stimulus to the carotid sinus baroreceptors will be immediately sensed by the extra-carotid baroreceptors (i.e. aortic baroreceptors) and/or other carotid baroreceptors, and the resulting reflex effects will tend to counteract the responses to the carotid sinus baroreflex itself (Manica & Mark, 1983; Sanders et al. 1988, 1989; Kawada et al. 2000). However, the HR and MAP responses to a 5 s neck chamber stimulus have been regarded as being only minimally affected by extra-carotid sinus baroreceptors (Potts et al. 1993; Raven et al. 1997). Therefore, we consider that the MSNA responses evoked by our neck chamber stimuli, especially in the early stages, mainly reflect regulation of MSNA by the carotid sinus baroreflex (Wallin & Eckberg, 1982; Rea & Eckberg, 1987; Fritsch et al. 1991).

The MSNA and MAP responses during PEMI to NP were greater than in the control situation. Although any HR change induced by NP might alter cardiac output and affect the blood pressure responses (Raven et al. 1997), neither the HR response nor the time course of the HR change was different between PEMI and the control. Hence, the differences in blood pressure responses between two conditions could not have been due to any difference in cardiac output secondary to different HR responses. Changes in cardiac stroke volume could also alter the cardiac output; however, previous studies have shown that there is little change in stroke volume during neck chamber stimuli (Levine et al. 1990) or during PEMI (Nishiyasu et al. 1994a). Thus, the augmented MAP response to NP seen during PEMI can be attributed to an augmentation of baroreflex-induced vasoconstriction. This idea seems to be supported by the data showing a greater MSNA response to NP during PEMI (Fig. 3). Thus, our results suggest that the interaction between the muscle metaboreflex and the carotid baroreflex leads to an augmentation of the carotid baroreflex regulation of blood pressure that occurs during NP (unloading) via an augmented carotid sinus baroreflex increase in sympathetic nerve activity.

During PEMI, the elevation in MSNA that occurred during and after NS was shifted to the left (Fig. 4), suggesting that the period of MSNA suppression induced by NS was shortened during metaboreflex activation. Moreover, the MAP decrement induced by NS was smaller and recovered more rapidly under ischaemic conditions. The initial, gradual reduction in MAP that occurred during NS may be due to an altered cardiac output secondary to HR change (Raven et al. 1997); however, the decrement in HR in this period was not different between the two conditions (PEMI and control; Fig. 8). Possibly, the initial decline in systemic blood pressure seen in Fig. 6 may rapidly have led to a reflex reversal of the suppression of MSNA via extra-carotid baroreceptors (i.e. aortic baroreceptors) and/or other carotid baroreceptors (Manica & Mark, 1983; Sanders et al. 1988, 1989; Kawada et al. 2000). In control, NS tended to suppress MSNA in spite of the falling MAP (which may have exerted an MSNA-augmenting effect). Under ischaemic conditions, carotid baroreceptors exposed to the same hypertensive stimuli (NS) suppressed MSNA only for the first 1 s (NS60) or 2 s (NS30) and, subsequently, the MSNA-suppressing effect was diminished and overcome by the MSNA-augmenting effect (which might have been strengthened by the muscle metaboreflex). This may be supported by the data indicating that the peak MSNA response to NP50 was increased nearly twofold during muscle ischaemia (Fig. 3). These results suggest that hypertensive stimuli to the CBR in humans may suppress MSNA and decrease blood pressure during PEMI, and further that the MSNA suppression time may be shortened by the interaction between the muscle metaboreflex and the carotid sinus baroreflex, resulting in a more rapid recovery in blood pressure.

Neither the time course of the HR responses to NP and NS nor the peak changes differed between control and PEMI (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8, Table 2). This unaltered baroreflex regulation of HR during PEMI is consistent with previous reports (Papelier et al. 1997; Jian et al. 2001). It has been reported that the HR responses evoked by neck chamber stimuli are predominantly mediated by carotid baroreflex control of cardiac parasympathetic activity (Eckberg, 1980). Our results therefore suggest that the interaction between the muscle metaboreflex and the arterial baroreflex does not affect the carotid baroreflex regulation of cardiac parasympathetic tone. Nishiyasu et al. (1994a) suggested that cardiac parasympathetic tone should increase during activation of the muscle metaboreflex (i.e. during PEMI) in humans. They suggested that this increase in cardiac parasympathetic tone might form part of the counteraction by the arterial baroreflex of the raised blood pressure induced by the muscle metaboreflex in humans. In view of this and similar suggestions made by others (Scherrer et al. 1990; Sheriff et al. 1990; O'Leary, 1993), we suggest that during PEMI: (a) the arterial baroreflex increases cardiac parasympathetic tone, thus counteracting the blood pressure rise caused by muscle metaboreflex activation, and (b) arterial baroreflex responsiveness (in terms of the regulation of cardiac parasympathetic activity) is maintained. These two effects would result in there being a higher cardiac parasympathetic tone during PEMI than in the control.

During PEMI, we found an augmented MSNA response in the first second after the start of NP (Fig. 3). This initial MSNA response to NP depends largely on the amplitude/area of the initial MSNA burst induced by the NP. MSNA is more commonly expressed as burst frequency (bursts per minute), burst incidence (bursts per 100 heart beats) or total activity (burst frequency × mean burst amplitude) than the burst amplitude/area (Sundlof & Wallin, 1977; Saito et al. 1990, 1993). The burst number (burst frequency or burst incidence) is regarded as a more robust measure than the burst amplitude/area because the absolute magnitude of a burst depends on its proximity to the recording electrode (Valbo et al. 1979). Expressing an increase in MSNA as the increase in total activity takes account of the increases in both burst number and burst amplitude (Sundlof & Wallin, 1977; Victor et al. 1988) and is a common way of expressing changes in MSNA. However, some reports have suggested that there are different mechanisms within the central nervous system controlling burst occurrence and burst strength (Hjemdahl et al. 1989; Sverridottir et al. 2000; Kienbaum et al. 2001). Recently, Kienbaum et al. (2001) suggested that the arterial baroreflex exerts a differential control over the occurrence and strength of MSNA bursts in humans. Their hypothetical model of this differential control system was based on the assumption that two CNS locations are involved: the strength of the burst is determined at one synapse - at which arterial baroreceptor traffic comes together with other types of afferent inputs (as well as intrinsic central nervous activity) - while at another synapse the afferent input from the arterial baroreceptors acts as a gate control and decides whether or not a burst occurs. According to their model, our results showing a greater burst response to NP during PEMI should be interpreted as follows. An increased afferent input from the muscles caused by activation of the muscle metaboreflex could augment MSNA burst strength at one synapse while the sudden change in afferent traffic from the carotid baroreceptors caused by the NP could open the gate at the other synapse, resulting in a greater MSNA burst response to NP being seen during PEMI. Further, our results suggest that the MSNA depression induced by NS may be shorter during PEMI (Fig. 4.). This may suggest that the increased afferent input from the muscles induced by activation of the muscle metaboreflex does not merely augment MSNA burst strength but alters the gate control of MSNA by the arterial baroreflex (arterial baroreflex control of burst occurrence) (Kienbaum et al. 2001). The shortened MSNA-depression time during PEMI may indicate a shorter gate-closed time. If so, a given NS stimulus, when applied during PEMI, would be inadequate to keep the gate closed (suppress MSNA) for as long as in control. Thus, our results could be said to be consistent with the above model. However, other mechanisms could be involved to explain the positive interaction between arterial baroreflex and muscle metaboreflex. This area clearly needs further study.

Limitations

Although we did not evaluate the efficiency of transmission of the NP/NS stimuli to the carotid sinus region, one report suggested complete transmission of such external stimuli (Eckberg & Sleight, 1992), whereas Ludbrook et al. (1977) reported that neck chamber pressure was not transmitted completely and that there was ‘asymmetrical’ transmission between NP and NS (86 % of NP and 64 % of NS). Recently, Querry et al. (2001) reported that the transmission of external pressure (neck chamber) to the carotid sinus was better when measured using a balloon-tipped catheter than when using a fluid-filled catheter and that the former registered transmission without a kinetic delay. As a consequence, in their study the percentage transmission of NP/NS stimuli to the carotid sinus region was higher than previously reported. Furthermore, they showed that stimulus transmission was not altered by low-intensity exercise (30 % maximal oxygen uptake) or during a Valsalva manoeuvre. Their results encouraged us to compare responses to NP/NS stimuli between control and PEMI in this study. In our subjects, we did not verify the location of the carotid sinus, which affects transmission of the external stimuli to the carotid sinus region (Querry et al. 2001). Individual differences in the location of the carotid sinus would cause differences among subjects in the responses shown by MAP, HR and MSNA to the neck chamber stimuli but should not lead to differences in responses between the two conditions (because there is little possibility of the location of the carotid sinus being greatly altered during PEMI).

In conclusion, the results obtained in this study show that dynamic carotid baroreflex-induced changes in MSNA and MAP are modulated during activation of the muscle metaboreflex. The interaction between the muscle metaboreflex and the arterial baroreflex: (a) augmented the MAP and MSNA response to NP (baroreceptor unloading), but (b) seemed to shorten the period of MSNA depression induced by NS (baroreceptor loading), while (c) making the decrease in MAP elicited by NS smaller and shorter lasting. Therefore, the modulation was different between carotid baroreflex unloading and loading. We suggest that this interaction is one of the mechanisms helping to increase blood pressure, and also maintain the elevated blood pressure, during activation of the muscle metaboreflex.

Acknowledgments

We should like sincerely to thank the volunteer subjects. We also greatly appreciate the help of Dr Robert Timms (English editing and critical comments). This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

References

- Alam M, Smirk FH. Observation in man upon a blood pressure raising reflex arising from the voluntary muscles. Journal of Physiology. 1937;89:372–383. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1937.sp003485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath E, Lindblad LE, Wallin BG. Effects of dynamic and static neck suction on muscle nerve sympathetic activity, heart rate, and blood pressure in man. Journal of Physiology. 1981;311:551–564. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delius W, Hagbarth KE, Hongell A, Wallin BG. General characteristics of sympathetic activity in human muscle nerves. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1972;84:65–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckberg DL. Nonlinearities of the human carotid baroreceptor-cardiac reflex. Circulation Research. 1980;47:208–216. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckberg DL, Sleight P. Human Baroreflexes in Health and Disease. Oxford, UK: Clarendon; 1992. pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Eckberg DL, Wallin BG. Isometric exercise modifies autonomic baroreflex responses in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1987;63:2325–2330. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.6.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel PJ, Ogoh S, Watenpaugh DE, Wasmund W, Olivencia-Yurvati A, Smith ML, Raven PB. Carotid baroreflex regulation of sympathetic nerve activity during dynamic exercise in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;280:H1383–1390. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagius J, Wallin BG. Sympathetic reflex latencies and conduction velocities in normal man. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1980;47:433–448. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(80)90098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch JM, Smith ML, Simmons D T F, Eckberg DL. Differential baroreflex modulation of human vagal and sympathetic activity. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:R635–641. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.3.R635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjemdahl P, Fagius J, Freyschuss U, Wallin BG, Daleskog M, Bohlin G, Perski A. Muscle sympathetic activity and norepinephrine release during mental challenge in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257:E654–664. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.257.5.E654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian C, Wilson TE, Shibasaki M, Hodges NA, Crandall CG. Baroreflex modulation of muscle sympathetic nerve activity during posthandgrip muscle ischemia in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2001;91:1679–1686. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada T, Masashi I, Hiroshi T, Takayuki S, Toshiaki S, Teiji T, Yusuke Y, Masaru S, Kenji S. Counteraction of aortic baroreflex to carotid sinus baroreflex in a neck suction model. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2000;89:1979–1084. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.5.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienbaum P, Karlsson T, Sverrisdottir YB, Elam M, Wallin BG. Two sites for modulation of human sympathetic activity by arterial baroreceptors? Journal of Physiology. 2001;531:861–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0861h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine BD, Pawelczyk JA, Buckey JC, Para BA, Raven PB, Blomqvist CG. The effect of carotid baroreceptor stimulation on stroke volume. Clinical Research. 1990;38:333A. [Google Scholar]

- Ludbrook J, Manica G, Ferrari A, Zanchetti A. The variable-pressure neck chamber method for studying the carotid baroreflex in man. Clinical Science and Molecular Medicine. 1977;53:165–171. doi: 10.1042/cs0530165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manica G, Mark L. Arterial baroreflexes in humans. In: Shepherd JT, Abboud FM, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 2, The Cardiovascular System, Peripheral Circulation and Organ Blood Flow. III. Bethesda, MD, USA: American Physiological Society; 1983. pp. 755–793. part 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JH. Neural control of the circulation during exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1990;22:141–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JH, Schmidt RF. Cardiovascular reflex control by afferent fibers from skeletal muscle receptors. In: Shepherd JT, Abboud FM, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 2, The Cardiovascular System, Peripheral Circulation and Organ Blood Flow. III. Bethesda, MD, USA: American Physiological Society; 1983. pp. 623–658. part 2. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyasu T, Tan N, Morimoto K, Nishiyasu M, Yamaguchi Y, Murakami N. Enhancement of parasympathetic cardiac activity during activation of muscle metaboreflex in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994a;77:2778–2783. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.6.2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyasu T, Tan N, Morimoto K, Sone R, Murakami N. Cardiovascular and humoral responses to sustained muscle metaboreflex activation in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1998;84:116–122. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyasu T, Ueno H, Nishiyasu M, Tan N, Morimoto K, Morimoto A, Deguchi T, Murakami N. Relationship between mean arterial pressure and muscle cell pH during forearm ischemia after sustained handgrip. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1994b;151:143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1994.tb09731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary DS. Autonomic mechanisms of muscle metaboreflex control of heart rate. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1993;74:1748–1754. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papelier Y, Escourrou P, Helloco F, Rowell LB. Muscle chemoreflex alters carotid sinus baroreflex response in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1997;82:577–583. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.2.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts JT, Raven PB. Effect of dynamic exercise on human carotid-cardiac baroreflex latency. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:H1208–1214. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.3.H1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts JT, Shi XR, Raven PB. Carotid baroreflex responsiveness during dynamic exercise in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;265:H1928–1938. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.6.H1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querry RG, Smith SA, Stromstand M, Ide K, Secher NH, Raven PB. Anatomical and functional characteristics of carotid sinus stimulation in humans. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2001;280:H2390–2398. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven PB, Potts JT, Shi X. Baroreflex regulation of blood pressure during dynamic exercise. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 1997;25:365–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea EF, Eckberg DL. Carotid baroreceptor-muscle sympathetic relation in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:R929–934. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.253.6.R929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, O'Leary DS. Reflex control of the circulation during exercise: chemoreflex and mechanoreflexes. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1990;69:407–418. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, O'Leary DS, Kellog DL. Integration of cardiovascular control systems in dynamic exercise. In: Rowell LB, editor. Handbook of Physiology, section 12, Exercise: Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems. Bethesda, MD, USA: American Physiological Society; 1996. pp. 1025–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Sagawa K. Baroreflex control of systemic arterial pressure and vascular beds. In: Shepherd JT, Abboud FM, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 2, The Cardiovascular System, Peripheral Circulation and Organ Blood Flow. III. Bethesda, MD, USA: American Physiological Society; 1983. pp. 453–496. part 2. [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Naito M, Mano T. Different responses in skin and muscle sympathetic nerve activity to static muscle contraction. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1990;69:2085–2090. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.6.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Tsukanaka A, Yanagihara D, Mano T. Muscle sympathetic nerve responses to graded leg cycling. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1993;75:663–667. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.2.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders JS, Ferguson DW, Mark AL. Arterial baroreflex control of sympathetic nerve activity during elevation of blood pressure in normal man: dominance of aortic baroreflexes. Circulation. 1988;77:279–288. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders JS, Mark AL, Ferguson DW. Importance of aortic baroreflex in regulation of sympathetic responses during hypotension. Evidence from direct sympathetic nerve recordings in humans. Circulation. 1989;79:83–92. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer U, Pryor SL, Bertocci LA, Victor RG. Arterial baroreflex buffering of sympathetic activation during exercise-induced elevations in arterial pressure. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1990;86:1855–1861. doi: 10.1172/JCI114916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheriff DD, O'leary DS, Scher AM, Rowell LB. Baroreflex attenuates pressor response to graded muscle ischemia in exercising dogs. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;258:H305–310. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.2.H305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenkle JM, Eckberg DL, Goble RL, Schelhorn JJ, Halliday HC. Device for rapid quantification of human carotid baroreceptor-cardiac reflex responses. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1986;60:727–732. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.2.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundlof G, Wallin BG. The variability of muscle nerve sympathetic activity in resting recumbent man. Journal of Physiology. 1977;272:383–397. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp012050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sverridottir YB, Rundqvist B, Johannsson G, Elam M. Sympathetic neural burst amplitude distribution: a more specific indicator of sympatho-excitation in human heart failure. Circulation. 2000;102:2067–2081. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valbo AB, Hagbarth KE, Torebjork HE, Wallin BG. Somatosensory proprioceptive, and sympathetic activity in human peripheral nerves. Physiological Reviews. 1979;59:919–957. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.4.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor RG, Bertocci LA, Pryor SL, Nunnally RL. Sympathetic nerve discharge is coupled to muscle cell pH during exercise in humans. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1988;82:1301–1305. doi: 10.1172/JCI113730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin BG, Eckberg DL. Sympathetic transients caused by abrupt alterations of carotid baroreceptor activity in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1982;242:H185–190. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.2.H185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]