Abstract

Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) in skeletal muscle in response to small depolarisations (e.g. to -60 mV) should be the sum of release from many isolated Ca2+ release sites. Each site has one SR Ca2+ release channel activated by its associated T-tubular voltage sensor. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether it also includes neighbouring Ca2+ release channels activated by Ca-induced Ca2+ release (CICR). Ca2+ release in frog cut muscle fibres was estimated with the EGTA/phenol red method. The fraction of SR Ca content ([CaSR]) released by a 400 ms pulse to -60 mV (denoted fCa) provided a measure of the average Ca2+ permeability of the SR associated with the pulse. In control experiments, fCa was approximately constant when [CaSR] was 1500-3000 μm (plateau region) and then increased as [CaSR] decreased, reaching a peak when [CaSR] was 300-500 μm that was 4.8 times larger on average than the plateau value. With 8 mm of the fast Ca2+ buffer BAPTA in the internal solution, fCa was 5.0-5.3 times larger on average than the plateau value obtained before adding BAPTA when [CaSR] was 300-500 μm. In support of earlier results, 8 mm BAPTA did not affect Ca2+ release in the plateau region. At intermediate values of [CaSR], BAPTA resulted in a small, if any, increase in fCa, presumably by decreasing Ca inactivation of Ca2+ release. Since BAPTA never decreased fCa, the results indicate that neighbouring channels are not activated by CICR with small depolarisations when [CaSR] is 300-3000 μm.

It is now generally believed that an obligatory step of excitation-contraction coupling in fast-twitch skeletal muscle involves activation of dyhydropyridine receptors (DHPRs) by T-tubular depolarisation (Ríos & Brum, 1987; Tanabe et al. 1988). Activation of a DHPR - also termed voltage sensor - opens its associated Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor or RyR) in the apposed sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane, presumably through some type of mechanical coupling, as first proposed by Schneider & Chandler (1973). In the terminal cisternae of the SR, Ca2+ release channels are disposed in a double array in which every other channel is coupled to a voltage sensor (Block et al. 1988), suggesting that uncoupled channels might be activated by Ca (Block et al. 1988; Ríos & Pizarro, 1988). The aim of the experiments described in this article was to evaluate whether or not such a mechanism occurs in the vicinity of a Ca2+ release channel activated by its associated voltage-sensor protein.

With small depolarisations, the rate of Ca2+ release is much less than the maximum rate indicating that only a small fraction of Ca2+ release channels are activated (estimated to be less than 1 in 10 000 channels at -75 mV in Pape et al. 1995). It follows that the average distance between Ca2+ release sites should be relatively large so that it is very unlikely that a site could be influenced by Ca released from neighbouring sites. This isolation is further enhanced by the presence of 20 mm of the high-affinity Ca2+ buffer EGTA in the internal solutions in this study. A Ca2+ release site in this context is considered to be a single Ca2+ release channel activated by its associated voltage-sensor protein or by a single such voltage-activated channel, and channels in the immediate vicinity activated by Ca-induced Ca2+ release (CICR). A Ca2+ release site corresponds to the discrete, localised Ca2+ release events observed with confocal microscopy and termed Ca2+ sparks. Pape & Carrier (1998) and Schneider (1999) raised doubts about an earlier study indicating that a large fraction of Ca2+ sparks recorded at -70 mV include Ca2+ release from two to three channels (Klein et al. 1996). In his perspective, Schneider (1999) reviewed this and other studies and indicated that it had not yet been conclusively established whether or not Ca2+ sparks include neighbouring channels activated by CICR. More recently, González et al. (2000) concluded from drug-induced/modified Ca2+ sparks that six or more channels do in fact open during a Ca2+ spark. As this study was done with permeabilised fibres, however, it is unclear whether their results apply to Ca2+ sparks in polarised muscle under more physiological conditions.

In order to evaluate if CICR occurs within Ca2+ release sites, Pape & Carrier (1998) studied the effect of varying the Ca content of the SR (denoted [CaSR]) on the permeability of the SR for Ca2+ release (denoted release permeability) in response to small depolarisations (to between -70 and -60 mV). The idea of varying [CaSR] is that it should produce approximately proportional changes in the concentration of free Ca2+ in the SR, the Ca2+ flux through an open channel, and Δ[Ca2+] at a Ca binding site on or near the myoplasmic opening of the channel. They found a bell-shaped relationship between release permeability and [CaSR] when [CaSR] increased from <100 to ≈1000 μm (units referred to myoplasmic volume) with a maximum at ≈300 μm. This bell-shaped relationship indicates the presence of both CICR and Ca inactivation of Ca2+ release acting within single, isolated Ca2+ release sites.

The main experimental aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of a large concentration of the fast-acting Ca2+ buffer BAPTA on the release permeability at the peak of the release permeability vs. [CaSR] relationship. As indicated in the Discussion, this concentration should significantly reduce the release permeability at the peak if released Ca2+ activates neighbouring channels. There should be little if any detectable reduction in release permeability if the CICR mechanism involves an autoregulatory mechanism in which Ca2+ released from a channel binds to a site on the same channel thereby increasing its mean open time and/or unitary conductance.

Methods

The experimental procedures are similar to those described in Pape & Carrier (1998) and Pape et al. (2002). Briefly, cold-adapted frogs (Rana temporaria) were decapitated and double pithed by protocols approved by the Comité d’éthique de l'expérimentation animale at the Université de Sherbrooke. A cut fibre (Hille & Campbell, 1976) from semi-tendinosus or ileo fibularis muscle stretched to a sarcomere spacing of 3.5-3.9 μm was mounted in a chamber maintained at 14-16 °C. The voltage in one end pool, V1, was controlled with a voltage-clamp set-up. A holding current, Ih, maintained the resting potential at -90 mV.

Composition of the internal and external solutions

The BAPTA-free end-pool solutions contained 45 mm Cs-glutamate, 20 mm EGTA, 6.8 mm MgSO4, 5 mm Cs2-ATP, 20 mm Cs2-creatine phosphate, 5 mm Cs3-phospho(enol)pyruvate and 5 mm 3-[N-morpholino]-propanesulphonic acid (MOPS). One of the BAPTA-free internal solutions contained no Ca and the other contained 1.76 mm Ca (estimated [Ca2+] was 36 nm). One of the internal solutions with 8 mm BAPTA contained no Ca and the other contained 3.57 mm Ca (estimated [Ca2+] was also 36 nm). These solutions contained 33 mm glutamate; the concentrations of EGTA, MgSO4, Cs2-ATP, Cs2-creatine phosphate, Cs3-phospho(enol)pyruvate and MOPS were the same as those in the BAPTA-free solution. The pH of the internal solutions was adjusted to pH 7 at room temperature with CsOH. The estimated [Mg2+] was 1 mm. The central pool solution contained 110 mm TEA-gluconate, 10 mm MgSO4, 1 μm tetrodotoxin (TTX) and 10 mm MOPS adjusted to pH 7.1. It was nominally Ca free.

EGTA/phenol red method and estimation of [CaSR] in presence of BAPTA

As described in detail elsewhere (Pape et al. 1995), the total amount of Ca released from the SR into the myoplasm (denoted Δ[CaT]; the subscript T refers to total) of a fibre containing a large concentration of EGTA can be estimated from the pH change produced when Ca2+ binds to H2EGTA2- resulting in CaEGTA2- and two protons. With no other added Ca2+ buffer (e.g. BAPTA in this article), this total amount is given by:

| (1) |

where β is the buffering power of myoplasm, estimated to be 22 mm/pH unit in cut fibres. This relationship assumes that EGTA captures all of the Ca that is released. If BAPTA is present, we can still use the relationship that:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Δ[CaEGTA]max is the amount of Ca bound to EGTA in response to a depolarisation that releases essentially all of the Ca from the SR and Δ[CaBAPTA]max is the corresponding amount of Ca bound to BAPTA estimated as described in Appendix A.

Additional details concerning the specifics of measuring pHR and ΔpH are given in Pape & Carrier (1998).

Approach used to assess release permeability

This section briefly summarises the experimental estimate of fCa (the fraction of SR Ca content released by a pulse), which was introduced in Pape et al. (2002), for the case when BAPTA and EGTA are both present. The term fCa can be represented by the equation:

| (6) |

where Δ[CaT] is the total amount of Ca released by the pulse and the denominator is the Ca content of the SR before the pulse. Since only a small fraction of the SR Ca content was released by pulses to -60 mV (the only voltage in which fCa was evaluated in this study), fCa is essentially the integral of the release permeability during the pulse. The term fCa therefore provides an indication of the average extent of activation of SR Ca2+ release channels during the pulse. In the presence of BAPTA, eqn (6) is given by

| (7) |

(Δ[Ca2+] is negligible compared with Δ[CaEGTA] and Δ[CaBAPTA].) Since Δ[CaBAPTA] was not measured, fCa was estimated from the relationship:

| (8) |

where Δ[CaEGTA]before, Δ[CaEGTA]after and Δ[CaEGTA]max are the values, respectively, before and after the pulse and after all of the Ca is released from the SR. In the absence of BAPTA, the numerator is essentially Δ[CaT], associated with the pulse, and the denominator is [CaSR], before the pulse, thereby giving a direct estimate of fCa. (For simplicity, the subtraction of values before the pulse is not shown in eqn (7), though this was done during its application.)

Appendix B evaluates errors associated with the estimation of fCa from the Δ[CaEGTA] signal. The general approach was to compare fCa values estimated with eqn (8) with the true value given by eqn (7). In the latter case, Δ[CaBAPTA] was estimated as described in Appendix A. The analyses - summarised in more detail in the Results - indicate that eqn (8) gives a very good estimate of the actual value of fCa when BAPTA is present.

Electrical measurements

As described in Irving et al. (1987), an agar bridge with 3 mm KCl was placed between V1 and its associated central pool electrode at the beginning of an experiment and any potential difference was nulled. At the end of the experiment, the voltage difference was re-measured; the electrode drift was less than 1.5 mV in all experiments included in this article.

The amount of intramembranous charge moved during a pulse (Qcm) was obtained from the integral of the OFF charge movement currents obtained by subtracting off small ionic components from the Itest - Icontrol signals, as described in Hui & Chandler (1990) and Jong et al. (1995b). Parameter values tabulated in the legends include holding current (Ih), apparent fibre capacitance (Capp), capacitance of surface/T-system membranes per unit length of fibre (cm), and internal longitudinal resistance per unit length of fibre (ri). Details concerning these parameters and other aspects of the electrical measurements are described in Chandler & Hui (1990).

Statistical tests of significance

Two sets of results are considered to be significantly different if Student's two-tailed t test parameter was < 0.05.

Results

Δ[CaEGTA] signals before and after addition of BAPTA

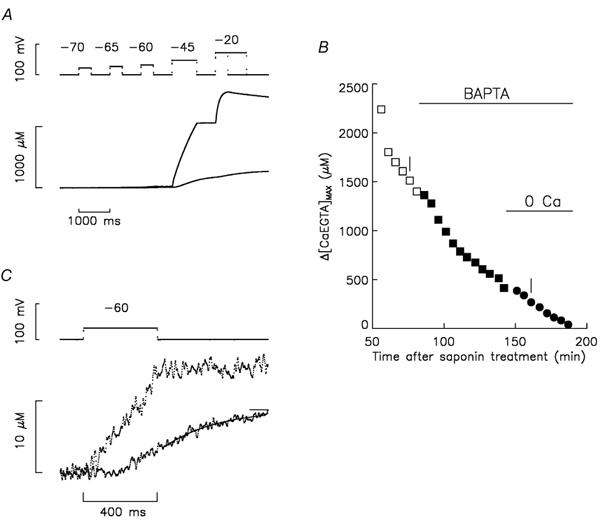

The top traces in Fig. 1A show two superimposed voltage signals obtained with stimulation protocols typical of those used in this study. The bottom pair of traces shows the corresponding Δ[CaEGTA] signals. The larger signal was obtained before adding 8 mm BAPTA to the internal solution (it corresponds to the voltage protocol with the shorter pulse to -20 mV). In the absence of BAPTA, the maximum of the Δ[CaEGTA] signal provides a direct estimate of [CaSR]R. The smaller Δ[CaEGTA] signal was obtained 77 min after the addition of BAPTA. The pulse protocol is essentially the same as that used in Pape & Carrier (1998). Briefly, the first three pulses were used to monitor the voltage steepness of Ca2+ release at small voltages. One of the purposes of the pulses to -45 and -20 mV was to monitor intramembranous charge movement (Qcm) when about 0.5-0.8 and close to all, respectively, of the charge had moved. As in the case of Pape & Carrier (1998), the voltage steepness of Ca2+ release and Qcm at -45 and -20 mV were stable during all of the experiments included in this article (three experiments were discarded due to significant changes in Qcm at -45 and/or -20 mV). Of main interest in this article are the results for the pulse to -60 mV, which always had a 400 ms duration. In about half of the experiments, the pulse to -60 mV was the first of the series; the order of the first three pulses had essentially no effect on the Δ[CaEGTA] signal associated with the pulse to -60 mV.

Figure 1. Effect of BAPTA on Δ[CaEGTA] and [CaEGTA]max vs. time of experiment.

A, the top traces show superimposed voltage signals before and 77 min after the addition of BAPTA. Given in order of application, pulses to -70, -65, -60, -45 and -20 mV had durations of 400, 400, 400, 800 and 400 (or 1200) ms, respectively. The duration of the period at -90 mV after the pulse to -60 mV was 600 ms. The bottom traces show the corresponding Δ[CaEGTA] signals. B, plots of Δ[CaEGTA]max vs. time after saponin treatment to permeabilise the fibre segments in the end pools. At 12 min, 0.8 mm phenol red was introduced into the end pools. The initial end-pool solution contained Ca and no BAPTA (□). At 84 min, the end-pool solution was exchanged for the one containing Ca and 8 mm BAPTA (▪). At 145 min, the end-pool solution was exchanged for the one containing no Ca and 8 mm BAPTA (•). The period of time between points was usually 5 min. C shows the same signals as in A for the pulse to -60 mV on an expanded scale. The interval of time between points was 1.25 ms. Fibre reference O05011. The following parameter values are for the stimulations before and after adding BAPTA, respectively, in A and C: fibre diameter, 112 and 106 μm; concentration of phenol red at the optical site, 1.34 and 2.56 mm; pHR, 6.959 and 7.064; Ih, -24 and -32 nA; Capp, 0.01184 and 0.01274 μF; cm, 0.164 and 0.173 μF cm−1; ri, 2.57 and 2.85 MΩ cm−1.

Figure 1B plots the maximum of the Δ[CaEGTA] signal (denoted Δ[CaEGTA]max) vs. time of the experiment for the two traces in Fig. 1A (indicated by vertical bars) and other stimulations from the same experiment. There was a pronounced progressive decrease in Δ[CaEGTA]max before adding BAPTA. This initial rate of decrease is greater than typically observed with nominally the same internal solution (Pape & Carrier, 1998; Pape et al. 2002), an effect attributable to a higher pHR at the optical recording site in the middle of the fibre (by 0.1-0.2 pH units in this and all of the other experiments in this study; see legends of Fig. 1 and Table 1). This unexplained higher pHR is expected to reduce the resting myoplasmic [Ca2+] set by the pH-sensitive equilibrium between Ca2+ and EGTA (Pape et al. 1995). Since the aim of this experiment was to alter [CaSR]R, the progressive decrease is actually somewhat advantageous. Following the addition of BAPTA to the internal solution, the rate of decrease of Δ[CaEGTA]max increased consistent with the expectation that BAPTA captures a large fraction of the released Ca. Following removal of Ca from the internal solution, Δ[CaEGTA]max approached zero.

Table 1.

Effect of BAPTA on fCavs. [CaSR] relationship at −6 mV

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCa at −60 mV | |||||||

| Fibre | 1500–3000 μm | 300–500 μm | (3)÷(2) | fCa,peak | [CaSR]peak (μm) | [CaSR]1/2 (μm) | |

| Control experiments with no BAPTA added | O29011 | 0.0151 | 0.0471 | 3.12 | 0.0483 | 460 | 954 |

| N01011 | 0.0149 | 0.0726 | 4.87 | 0.0806 | 318 | 840 | |

| N02011 | 0.0075 | 0.0573 | 7.64 | 0.0600 | 348 | 944 | |

| N07011 | 0.0284 | 0.1154 | 4.06 | 0.1032 | 443 | 864 | |

| D04011 | 0.0146 | 0.0535 | 3.66 | 0.0540 | 359 | 727 | |

| D07011 | 0.0639 | 0.3438 | 5.38 | 0.3441 | 368 | 969 | |

| Mean | 0.0241 | 0.1150 | 4.79 | 0.1150 | 383 | 883 | |

| s.e.m. | 0.0084 | 0.0469 | 0.66 | 0.0466 | 23 | 38 | |

| Experiments in which 8 mm BAPTA was added | O05011 | 0.0093 | 0.0293 | 3.15 | 0.0297 | 462 | 1184 |

| O10011 | 0.0059 | 0.0378 | 6.41 | 0.0408 | 300 | 859 | |

| O12011 | 0.0056 | 0.0225 | 4.02 | — | — | — | |

| O15011 | 0.0259 | 0.0975 | 3.76 | — | — | — | |

| O16011 | 0.0160 | 0.1435 | 8.97 | 0.1433 | 406 | 1104 | |

| Mean | 0.0125 | 0.0661 | 5.26 | 0.0713 | 389 | 1049 | |

| s.e.m. | 0.0038 | 0.0220 | 1.08 | 0.0362 | 48 | 98 | |

Effect of BAPTA on fCa at –60 mV. The first and second sections give results from control and BAPTA experiments, respectively. Column 1 gives the fibre reference. Column 2 gives the average values of fCa for all of the stimulations whose [CaSR] values before the pulse were in the range 1500–3000 μm. Only values before adding BAPTA are included. Column 3 gives the average values of fCa when [CaSR] was 300–500μm. Column 4 gives the ratio of the value in column 3 to that in column 2. Columns 5,6 and 7 give values of fCa,peak [CaSR]peak and [CaSR]1/2. None of the means in the BAPTA experiments is significantly different from the control value. See text for details. Four ranges are given for the following experimental parameters. The first and second ranges were from the control experiments when [CaSR] was 1500–3000 μm and 300–500 μm, respectively (from stimulations used in columns 2 and 3, respectively). The third and fourth ranges correspond to the first and second ranges, respectively, for the experiments in which BAPTA was added. Time after saponin treatment: 56–101, 116–153, 55–87, 126–226 min; fibre diameter: 97–119, 97–113, 111–143, 103–138 μm; pHR: 6.88–7.11, 6.80–7.05, 6.94–7.10, 6.85–7.10; Ih: –18 to –52, –19 to –64, –21 to –69, –23 to –68 nA; Capp: 0.00861–0.01700, 0.00847–0.001745, 0.01184–0.02089, 0.01288–0.01963 μF; ri: 1.98–3.90, 2.05–3.62, 1.90–2.66, 1.62–2.84 MΩ cm−1.

Figure 1C shows on an expanded scale the same Δ[CaEGTA] signals as in Fig. 1A associated with the pulse to -60 mV. The larger trace was obtained before adding BAPTA. It has a ramp-like appearance during the pulse and an approximately constant value after the pulse. This form is consistent with rapidly reaching a steady level of activation of SR Ca2+ release after the start of the pulse and rapidly turning off release after the pulse. As discussed previously (Pape et al. 2002), the waveform of the smaller Δ[CaEGTA] is consistent with the expected rapid buffering properties of 8 mm BAPTA. Briefly, most of the Ca2+ released during the pulse is captured by BAPTA due to its much faster ON rate for Ca binding compared with EGTA. After release is over, Δ[CaEGTA] has a slow, approximately monoexponential increase whose time constant (286 ms) is reasonably consistent with that predicted for re-distribution of Ca from BAPTA to EGTA. The re-distribution ends when equilibrium conditions of BAPTA and EGTA with [Ca2+] are reached in the myoplasm.

As noted in the Methods, the aim of these experiments was to estimate fCa, the fraction of SR Ca content released by a pulse, which is very close to the integral of release permeability during the pulse. The value of fCa was estimated from the Δ[CaEGTA] signal with eqn (8). Each of the Δ[CaEGTA] values (Δ[CaEGTA]before, Δ[CaEGTA]after and Δ[CaEGTA]max) should be equilibrium values. For example, Δ[CaEGTA]after should be estimated at the end of the re-distribution of Ca from BAPTA to EGTA after the pulse, as indicated by the fitted single-exponential function and its final constant in Fig. 1C. Because of noise, there was some variability in the exponential time constants from similar fits in other runs, which produced significant uncertainty in the estimate of Δ[CaEGTA]after. As a result, Δ[CaEGTA]after was obtained from the average of Δ[CaEGTA] during the last 100 ms of the repolarisation to -90 mV. This produces an underestimation in fCa, which is evaluated along with other errors in fCa in Appendix B and summarised later in the Results.

fCa vs. Δ[CaSR] in control experiments

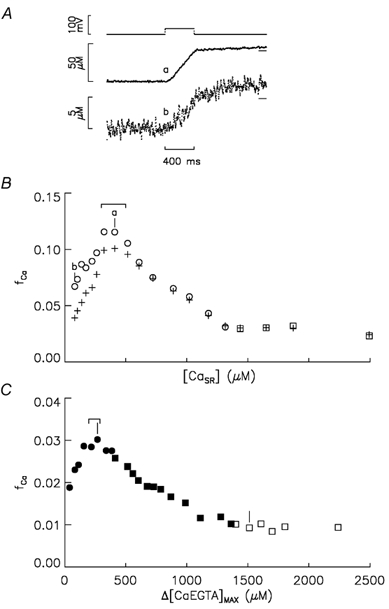

The top traces in Fig. 2A show two superimposed voltage pulses to -60 mV and the bottom traces show the corresponding Δ[CaEGTA] signals in a control experiment. Control experiments were carried out in essentially the same way as the BAPTA experiments except that BAPTA was never present. One way in which Δ[CaEGTA]after was determined for the evaluation of fCa was from the average during the 5 ms period just after the end of the pulse to -60 mV; the values with this approach are indicated by the line segments under the final levels of the Δ[CaEGTA] signals in Fig. 2A. This approach is used for the comparison with earlier release permeability vs. [CaSR] data (Pape & Carrier, 1998), since it also reflects Ca2+ release only during the pulse. (The approach described in the next paragraph includes contributions of Ca2+ release after the fibre is repolarised to -90 mV and is used for the comparison with the BAPTA experiments.) The cross symbols in Fig. 2B plot fCa vs. Δ[CaEGTA]max determined with this approach. (Δ[CaEGTA]max corresponds to the value of [CaSR] before the pulse to -60 mV since BAPTA was not present and the pulse to -60 mV was the first pulse of the stimulation protocol so that Δ[CaEGTA]before was zero.) The main features to note are: (1) an increase in fCa as [CaSR] increases from <100 to 300 μm; (2) a maximum between 300 and 500 μm; (3) a large decrease as [CaSR] increases to about 1300 μm; and (4) an approximately constant value between 1300 and 2500 μm (termed the plateau region). These features and their relative proportions are essentially the same as those of release permeability vs. [CaSR] shown in an earlier study (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6 in Pape & Carrier, 1998). The initial increase was attributed to CICR and the subsequent decrease to Ca inactivation of Ca2+ release.

Figure 2. Delayed turn-off of Ca2+ release at reduced [CaSR] and fCa vs. [CaSR] with and without BAPTA.

A, the top traces show two superimposed voltage pulses to -60 mV in an experiment in which BAPTA was not added. The bottom traces labelled a and b show the corresponding Δ[CaEGTA] signals obtained, respectively, when [CaSR] was 409 and 82 μm (see text for details). B plots fCa associated with pulses to -60 mV vs. [CaSR] from an experiment containing no BAPTA. The cross and open symbols were obtained from Δ[CaEGTA]after values determined, respectively, just after the pulse to -60 mV (lower line segments in A) and the average value 900-1000 ms after the pulse (higher line segments in A). □ and ○ were obtained, respectively, with and without Ca in the end pools. The points labelled a and b correspond to the similarly labelled traces in A. The range indicates [CaSR] values of 300-500 μm. C plots fCa associated with pulses to -60 mV vs. [CaEGTA]max from the experiment in Fig. 1 in which 8 mm BAPTA was added. As in Figs 1 and 2b, filled and open symbols were obtained with and without BAPTA, respectively, and squares and circles were obtained with and without Ca, respectively, in the end pools. The two vertical lines mark the stimulations shown in Fig. 1A and C. The range indicates points when the estimated [CaSR] was 300-500 μm. Fibre reference for panels A and B is N07011. The following parameter values are for the first and last points in B, respectively: time after saponin treatment, 60 and 153 min; fibre diameter, 97 and 97 μm; concentration of phenol red at the optical site, 0.83 and 2.10 mm; pHR, 6.885 and 6.957; Ih, -51 and -65 nA; Capp, 0.00862 and 0.00852 μF; cm, 0.111 and 0.107 μF cm−1; ri, 3.42 and 3.42 MΩ cm−1.

For the comparison with the BAPTA experiments below, Δ[CaEGTA]after was determined from the average during the last 100 ms of the OFF pulse to -90 mV. The higher line segments at the end of the Δ[CaT] traces in Fig. 2A show these values (the line is difficult to distinguish from the data in trace a). The open circles in Fig. 2B plot fCa vs. [CaSR] determined in this way. These values of fCa show the same features as the release permeability and fCa vs. [CaSR] relationships above except that the fCa does not extrapolate to approximately zero as [CaSR] approaches zero. The reason for this can be seen by comparing the Δ[CaT] signals in Fig. 2A after the end of the pulse to -60 mV. In the case of trace a, obtained near the peak of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship (point a in Fig. 2B), a relatively small amount of Ca2+ release occurred after the repolarisation to -90 mV. This indicates a sharp turn-off of Ca2+ release, which was typical for all of the control experiments when [CaSR]R was >300 μm, i.e. near the peak of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship and above. In contrast, a relatively large fraction of Ca is released after the pulse in trace b, an effect that becomes more pronounced as [CaSR] decreases below 300 μm. As seen below, this article only considers effects of BAPTA when [CaSR] is > 300 μm. In particular, one aim was to evaluate the effect of BAPTA on fCa when [CaSR] was 300-500 μm, a range that spans the peak of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship (see range indicated above the peak in Fig. 2B). The relative contribution of Ca2+ released after the pulse to -60 mV to fCa in this range of [CaSR] values is relatively small in the control experiments (≈10 %) and, as discussed in Appendix B, the contribution is also likely to be small in the BAPTA experiments.

fCa vs. Δ[CaEGTA]max and estimation of [CaSR] in BAPTA experiments

Figure 2C plots fCa at -60 mV vs. Δ[CaEGTA]max from the experiment shown in Fig. 1 in which BAPTA was added. The points labelled with vertical line segments are from the stimulations shown in Fig. 1A and C. The functional form of fCa vs. Δ[CaEGTA]max is similar to that determined in the same way in the control experiment in Fig. 2B (open symbols), including a peak at low values of Δ[CaEGTA]max. It is important to note, however, that the Δ[CaEGTA]max values on the abscissa do not correspond to [CaSR] values when BAPTA was present in the internal solution (filled symbols).

In order to compare the effects of adding BAPTA on the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship it was necessary to estimate [CaSR] in the presence of BAPTA. The procedure for this - described in Appendix A - involved estimating Δ[CaBAPTA]max from initial and final values of [CaEGTA] and adding this to the measured Δ[CaEGTA]max value to obtain [CaSR]R. This procedure used the equilibrium binding relationships of BAPTA and EGTA with Ca, both of which depend on pH due to the pH sensitivity of the KD values (the OFF rate of Ca from EGTA is pH sensitive since two protons bind to CaEGTA2- before Ca comes off; KD of BAPTA has a much weaker pH dependence). Although previous results indicated that phenol red accurately records changes in myoplasmic pH (ΔpH), the absolute value of the pH appeared to be too acidic by 0.1-0.4 pH units (0.2 on average), consistent with a corresponding shift in its pK value in myoplasm (Pape, 1990). Unless indicated, estimates of [CaSR] when BAPTA was present used pHR values that were 0.2 pH units more positive than the apparent pHR reported by phenol red. The estimation of [CaSR] also depends on [BAPTAT] at the optical recording site, which was estimated with the diffusion equation and the time after adding 8 mm BAPTA to the end pools. This estimation depends on the diffusion constant of BAPTA (DBAPTA), which is also uncertain. Based on the diffusion constants of other molecules, DBAPTA is likely to be in the range from 1.2 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 to half this value: 0.6 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 (see Appendix A). Again, unless indicated, estimates of [CaSR] were done with one value of DBAPTA - 0.9 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 - which is in the middle of the likely range of DBAPTA values.

An important aim of this study was to evaluate whether BAPTA affected fCa at the peak of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship. One way this was done was with the average of fCa values when [CaSR] was 300-500 μm, the range in which the peak occurs when BAPTA is not present. The ranges above the peaks in Fig. 2B and C indicate the points in which [CaSR] was 300-500 μm in a control and BAPTA experiment, respectively. It is important to note that the range in the BAPTA experiment also spanned the peak values of fCa.

Summary of effect of BAPTA on fCa when [CaSR] was 300-500 μm

Table 1 summarises results from all of the experiments in this study. The values at the end of the legend, including pHR and electrical properties of the fibres, indicate that fibre properties were reasonably stable during the experiments and were not significantly different between the control and BAPTA experiments. Column 2 gives average values of fCa from stimulations when [CaSR] was 1500-3000 μm, the range corresponding to the plateau region of the fCa vs. [CaSR]R relationship. Since these values were obtained under the same conditions, i.e. without BAPTA, they should not be significantly different. Although the average value for the control experiments is almost twice that for the experiments in which BAPTA was later added (0.0241 vs. 0.0125), the difference is not statistically significant. It is also noted that the discrepancy is almost entirely due to the large fCa for one of the control experiments (Fibre D07011). The large range in fCa values (≈10-fold increase from smallest to largest) is similar to the range in release permeability values at -60 mV observed previously (column 2 of Table 1 in Pape & Carrier, 1998), a result probably due to fibre-to-fibre variation in voltage activation (cf. range in properties of Qγ in Table 1 of Pape & Carrier, 2002). In summary, the set of experiments in the first section of Table 1 should represent reasonable controls for those in which BAPTA was later added despite the difference in average values in column 2, particularly since the main focus below is on relative changes in fCa.

Column 3 of Table 1 gives fCa when the estimated [CaSR] was 300-500 μm. Column 4 gives the ratio of values in column 3 to those in column 2. This is the factor by which fCa increased when [CaSR] decreased from 1500-3000 μm (column 2) to 300-500 μm (column 3). The average factor for the BAPTA experiments of 5.26 was slightly greater though not significantly different from the control value of 4.79. This indicates that BAPTA did not decrease release permeability at the peak of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship, as would be expected if neighbouring channels are recruited by CICR.

Appendix B evaluates several possible errors associated with the approach used to estimate fCa for the values in column 3 of Table 1, when [CaSR] was 300-500 μm. The analyses indicate that the errors in fCa should be relatively minor with an overall error ≤10 %. Earlier analyses indicate similar small errors at higher values of [CaSR] (>1500 μm; Pape et al. 2002). Results not shown indicate similar small errors in fCa over intermediate values of [CaSR], which is important for data presented below. Results below also indicate that uncertainty in the estimate of [CaSR] has almost no effect on the values in column 4 of Table 1, which strengthens the conclusion that BAPTA does not affect fCa when [CaSR] is 300-500 μm.

Test of reversibility of the effect of decreasing SR Ca content on fCa

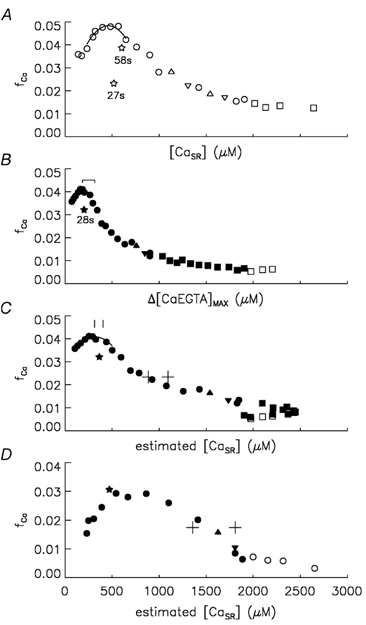

One way to decrease SR Ca content before a stimulation is to decrease the interval between stimulations from the usual 5 min resting period, which provides enough time for essentially all of the recoverable Ca to be pumped back into the SR (Pape et al. 1995). In Fig. 3, the inverted triangles, stars, and triangles, respectively, plot the results from the stimulation just before decreasing the inter-stimulus period, just after the short period, and 5 min later. In the control experiment in Fig. 3A, the lower star symbol was the first test of reversibility done just after the point when [CaSR] was 1697 μm. As indicated, the inter-stimulus period was 27 s and only a modest increase in fCa was observed. A similar result was observed in all of the other three control experiments in which a 25-30 s inter-stimulus period was used. The second test of reversibility in Fig. 3A was done with a 58 s inter-stimulus interval after the point when [CaSR] was 1306 μm. In this case, the increase in fCa was similar to that observed by the long-term decrease in [CaSR] caused by diffusion of Ca from the fibre. (For conciseness below, a correspondence between the increase in fCa with short- and long-term decreases in [CaSR] is termed short-term reversibility.) Similar short-term reversibility was observed in all of the five experiments in which an ≈1 min inter-stimulus interval produced a similar decrease in [CaSR] (from 970-1300 μm to 350-630 μm). (The five experiments include two described with Fig. 6 of Pape & Carrier, 1998, which are not included in this article.) In summary of the control experiments, short-term reversibility was always observed when the inter-stimulus interval was ≈1 min and never when the inter-stimulus interval was 25-30 s.

Figure 3. Plots of fCa vs. [CaSR] in control and BAPTA experiments and tests of reversibility.

As in Figs 1 and 2, filled and open symbols were obtained with and without BAPTA, respectively, and squares and circles were obtained with and without Ca, respectively, in the end pools. ▿, ⋆ and ▵ show points when short-term reversibility was tested, which was all done without Ca in the end pools. See text for meaning of symbols. A shows a plot of fCa vs. [CaSR] in a control experiment. Fibre reference O29011. B shows a plot of fCa vs. Δ[CaEGTA]max in an experiment in which BAPTA was added. As in Fig. 2C, the range indicates points when the estimated [CaSR] was 300-500 μm. Fibre reference O10011. C shows the same fCa data as in B except that now it is plotted vs. [CaSR], estimated as described in Appendix A. The cross symbols and vertical line segments show estimates of [CaSR]1/2 and [CaSR]peak, respectively. In each case, the highest [CaSR] value was obtained with no pH correction and with the higher value of DBAPTA (1.2 × 10−6 cm2 s−1) and the lowest [CaSR] value with 0.2 pH units added to the apparent pH recorded by phenol red and with the lowest value of DBAPTA (0.6 × 10−6 cm2 s−1). D shows fCa vs. [CaSR] in the same format as in C from an experiment in which Ca was removed relatively early from the end pools. Fibre reference O12011. See text for details.

Figure 3B indicates short-term reversibility with a 28 s inter-stimulus interval when BAPTA had been present for 67 min. Similar short-term reversibility was observed in all of the BAPTA experiments in this study, all of which used 25-30 s inter-stimulus intervals to decrease [CaSR]. A likely explanation for the lack of short-term reversibility in the control experiments with 25-30 s inter-stimulus intervals is that a maintained Ca inactivation caused by an elevated myoplasmic [Ca2+] prevents the increase in fCa. Adding BAPTA or increasing the inter-stimulus interval to ≈1 min decreased inactivation by decreasing myoplasmic [Ca2+] either by buffering Δ[Ca2+] with BAPTA or by increasing the time for pumping Ca back into the SR. This explanation might appear at odds with the conclusions of Jong et al. (1995a) and Schneider & Simon (1988) that Ca inactivation recovers with a time constant of ≈50 ms and ≤ 90 ms, respectively, following repolarisation to -90 mV under voltage-clamp conditions. However, in the experiments of Jong et al. (1995a), which also had 20 mm EGTA in the internal solution, the recovery of Ca inactivation was studied following pre-pulses that released only ≈250 μm Ca as opposed to a released minus recovered amount of Ca of ≈1000 μm when the inter-stimulus interval was ≈30 s (cf. difference between [CaSR] values for point labelled 28 s and the inverted triangle at [CaSR] = 1697 μm in Fig. 3A). As a result, the increase in resting [Ca2+] associated with the non-recovered Ca for the point labelled 28 s (estimated to be ≈60 nm) was approximately four times greater than that caused by pre-pulses in Jong et al. (1995a). The continued presence of Ca inactivation even after ≈30 s in this study is consistent with the assessment of Schneider & Simon (1988) that the ‘apparent dissociation constant for calcium-dependent inactivation’ is ‘only slightly above resting [Ca2+]’ and that recovery from Ca inactivation does not occur as long as [Ca2+] remains elevated.

In summary, results in this section support the earlier conclusion that the increase in release permeability when [CaSR] decreases from ≈1000 to ≈300 μm in the absence of BAPTA is not due to some type of long-term change associated with the length of the experiment (Pape & Carrier, 1998). The short-term reversibility in the BAPTA experiments indicates that the increase in fCa with decreasing SR Ca content is not due to a long-term change associated with exposure to BAPTA.

Effect of BAPTA on the functional form of fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship

Figure 3C plots fCa vs. [CaSR] for the experiment in Fig. 3B. This figure illustrates additional features of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship evaluated in this study, including values of fCa and [CaSR] at the peak of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship (denoted by fCa,peak and [CaSR]peak, respectively) and the value of [CaSR] when fCa was halfway between the plateau and peak levels (denoted [CaSR]1/2). The values of fCa,peak and [CaSR]peak were obtained from a quadratic function fitted to points spanning the peak of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship, as indicated by the curves in Fig. 3A and C. [CaSR]1/2 was obtained from the fit of a quadratic function or line to points spanning the mid-range of the falling phase of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship (not shown).

Form of fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship in control experiments

Columns 5-7 of Table 1 give the values of fCa,peak, [CaSR]peak and [CaSR]1/2, respectively, obtained as described in the previous section. As mentioned above, the first section of the table gives results for control experiments in which BAPTA was never added. The average values of [CaSR]peak and [CaSR]1/2 in these control experiments of 383 and 883 μm, respectively, are both significantly greater than analogous average values of 300 and 536 μm, respectively, obtained from release permeability vs. [CaSR] data from earlier experiments carried out in essentially the same way (columns 5 and 6 of Table 1 of Pape & Carrier, 1998). This difference is unexplained since fibre properties including pHR were similar. The difference is not due to the use of release permeability as opposed to fCa data, since the values of [CaSR]peak and [CaSR]1/2 are essentially the same for both types of data (not shown). The basic shape of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship, however, was not changed, including an approximately 5-fold decrease from the peak to the plateau level. It is also important to note that the control experiments in this study should provide a good reference to the experiments in which BAPTA was added since they were carried out on the same set of frogs and with internal solutions prepared with the same stock solutions. In particular, the same stock solution of caesium salts of ATP, creatine phosphate and phosphoenol pyruvate was used for all of the experiments in this study (prepared as described in Pape & Carrier, 1998).

Summary of effect of BAPTA on fCa,peak, [CaSR]peak and [CaSR]1/2

The two experiments not included in columns 5-6 of Table 1 (O12011 and O15011) had somewhat different protocols and results and are discussed below. The value of [CaSR]peak of 389 μm in the BAPTA experiment was very similar to the control value of 383 indicating that BAPTA did not affect the location of the peak of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship. This is also evident by the fact that the fCa,peak value in each experiment (column 5) is almost the same as the corresponding value of fCa when [CaSR] was 300-500 μm (column 3) in both the control and BAPTA experiments. The mean value of [CaSR]1/2 in the BAPTA experiment of 1049 μm is somewhat greater than the control value of 883 μm, though the difference is not significantly different. A higher value of [CaSR]1/2 would indicate that BAPTA somehow reduced Ca inactivation at intermediate values of [CaSR], i.e. during the falling phase of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship.

Does the set of parameters used to estimate [CaSR] significantly affect the results?

As noted above, the estimation of [CaSR] in the presence of BAPTA depends on pHR and DBAPTA, both of which are somewhat uncertain. In order to evaluate if this significantly affects the interpretation of the data above, estimates of [CaSR] were carried out with and without a 0.2 pH unit correction applied to the apparent pH indicated by phenol red and with DBAPTA values of 0.6 and 1.2 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 (see above). Values of the factor by which fCa increased when [CaSR] decreased from 1500-3000 μm to 300-500 μm (cf. values in column 3 of Table 1) ranged from 4.97 to 5.31. The values were all similar to the value of 5.26 obtained with the default set of parameters above (0.2 pH shift correction and DBAPTA value of 0.9 × 10−6 cm2 s−1) and all slightly greater than, though not significantly different from, the control value of 4.79. These results indicate that uncertainty about [CaSR] does not influence the conclusion that a large concentration of BAPTA has little if any influence on release permeability when [CaSR] is 300-500 μm.

The reason DBAPTA was not particularly important is that sufficient time had elapsed by the time [CaSR] reached 300-500 μm for [BAPTAT] at the optical site to approach equilibrium with the end-pool concentration of 8 mm, even with the lower value of DBAPTA. The minimum estimate of [BAPTAT] was 5.7 mm (Fibre ID O12011; 50 min exposure to BAPTA), which is only 13 % less than that obtained with the higher value of DBAPTA, 1.2 × 10−6 cm2 s−1. The estimated resting concentration of Ca-free BAPTA - the form available to complex Ca - ranged from 5.4 to 7.3 mm. The average value was 6.5 mm.

The mean values of fCa,peak were essentially identical (0.0712-0.0713) with all sets of parameters used to estimate [CaSR] in the BAPTA experiments. The vertical line segments in Fig. 3C indicate the range of [CaSR]peak values obtained in the experiment displayed. This range and similar ranges below are indicative of the uncertainty in the value of interest, [CaSR]peak in this case. Although the range is not wide, it does suggest that [CaSR]peak is somewhat sensitive to how [CaSR] is estimated. The mean value of [CaSR]peak in the BAPTA experiments ranged from 383 to 517 μm. Only the highest value of 517 μm (s.e.m. = 57; obtained with no pH correction and with DBAPTA = 1.2 × 10−6 cm2 s−1) was significantly different from the control value of 383 μm in column 6 of Table 1. This indicates that BAPTA may have produced a slight increase in the location of the peak of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship, though any effect would not have been very pronounced.

The cross symbols in Fig. 3C indicate the range of [CaSR]1/2 values obtained in the experiment displayed. The mean values of [CaSR]1/2 ranged from 993 μm (s.e.m. = 55; obtained with the 0.2 shift in pH and with DBAPTA = 0.6 × 10−6 cm2 s−1) to 1303 μm (s.e.m. = 104; obtained with no pH correction and with DBAPTA = 1.2 × 10−6 cm2 s−1). With the exception of the lowest value and the value of 1049 μm obtained with the default parameters, all of the mean values were significantly greater than the control value of 883 μm in column 7 of Table 1. In summary, BAPTA produced either no effect or only a modest increase in [CaSR]1/2, indicative of a possible modest increase in fCa over intermediate values of [CaSR].

Two BAPTA experiments in which Ca was removed relatively early

In the three BAPTA experiments included in columns 5-7 of Table 1, Ca was not removed from the end pools until 57-61 min after BAPTA was first added (cf. Fig. 1B). Figure 3D shows analogous results to those in Fig. 3C from an experiment in which Ca was removed from the end pools early in the experiment. (The Ca-free, BAPTA-free internal solution replaced that containing Ca 10 min before the first stimulation. After the initial measurements in this solution, the Ca-free internal solution containing BAPTA was introduced.) The functional form of the fCa vs. [CaSR] in Fig. 3D differs from that in Fig. 3C in two ways. One is that [CaSR]1/2 is greater and the other is that the peak is broader, resembling more of a plateau than a distinct peak. Similar results to those in Fig. 3D were obtained in the other experiment in which Ca was removed relatively early in the experiment. It is important to note that the apparently different results are not attributable to a difference in the experimental protocols since control experiments had essentially the same fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship whether Ca was removed early or relatively late. (This conclusion is based on the experiments described in Pape & Carrier (1998), which were carried out in the same way as the control experiments in this study except that Ca was removed early in five of the seven experiments. In all of the control experiments in this study, the end pools contained Ca until after the initial 4-5 stimulations, at which time the end-pool solution was replaced with the Ca-free and BAPTA-free internal solution.)

As in Fig. 3C, the range defined by the cross symbols in Fig. 3D indicates the uncertainty in [CaSR]1/2. The uncertainty is significantly greater in this case due to the fact that the halfway point was reached early in the experiment when BAPTA had been present for only about 15-20 min. As a result, the value of [BAPTAT] used to estimate [CaSR] was much more sensitive to whether the lower or higher value of DBAPTA was assumed. This suggests one possible explanation for the difference in the shape of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship in Fig. 3D compared with 3C, namely that [BAPTAT] and, thereby, [CaSR] were overestimated early in the experiment. Another possibility is that the protocols produced real differences in the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship perhaps related to the fact that the transition from [CaSR] values near 1500 to 500 μm would have occurred at lower BAPTA concentrations.

Because of the relatively large uncertainty in [CaSR]1/2 and [CaSR]peak and also [BAPTAT] during the transition over intermediate values of [CaSR], the two experiments in which Ca was removed early were not included in columns 5-7 of Table 1 and their results over intermediate values of [CaSR] are not discussed further. As noted above, however, BAPTA had been present for at least 50 min by the time [CaSR] had reached 300-500 μm so that [BAPTAT] should have approached its equilibrium value. As a result, inclusion of these experiments in columns 3 and 4 of Table 1 seems justified.

Discussion

As mentioned in the Introduction, Ca2+ release sites with small depolarisations should have a single Ca2+ release channel activated by its associated voltage sensor. The aim of this article was to assess whether or not they also include neighbouring channels recruited by CICR. The experimental approach was to evaluate whether release permeability (as assessed by fCa, the fraction of SR Ca content released by a pulse) is decreased by the introduction of a large concentration of the fast Ca2+ buffer BAPTA into the internal solution. One main result of this article is that the value of fCa at the peak of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship - which occurs when [CaSR] is 300-500 μm - is not influenced by the introduction of a large concentration of BAPTA in the myoplasm (cf. Fig. 3A and C; columns 3-6 of Table 1). The next section discusses the implications of this lack of an effect of BAPTA.

Distinguishing between two mechanisms of CICR when [CaSR] is 300-500 μm

As illustrated in Fig. 2B (+ symbols) and supported by other data in this study (not shown), increasing [CaSR] from 100 to 400 μm in the absence of BAPTA increases release permeability at -60 mV by > 2-fold (see also Table 1 of Pape & Carrier, 1998). This increase could have been due to one of the following two types of CICR: (1) an auto-regulatory mechanism in which Ca2+ released from a channel activated by its voltage sensor binds to a site on the same channel thereby increasing its unitary conductance or mean open time or (2) recruitment of neighbouring SR Ca2+ release channels. The following analysis argues against the second possibility by showing that a large concentration of BAPTA should produce essentially the same decrease in Δ[Ca2+] at neighbouring channels as reducing [CaSR] from 400 to 100 μm.

The solution of the diffusion equation in the presence of a diffusible Ca2+ buffer like BAPTA is very closely approximated by:

| (9) |

where φ is the flux of Ca2+ through the channel, DCa is the diffusion constant of Ca2+, r is the distance from the mouth of the open channel and λCa is a space constant related to the average distance a Ca2+ ion diffuses before it is captured by the buffer (eqn (B21) in Pape et al. 1995; also Neher, 1986; Stern, 1992). The exponential factor gives the effect of BAPTA whereas the first factor gives Δ[Ca2+] in the absence of diffusible Ca2+ buffers. (The effect of 20 mm EGTA is ignored since it should be much less than that of 8 mm BAPTA and it would unnecessarily complicate the solution.) One thing to note is that changing [CaSR] should produce an approximately proportional change in [Ca2+] in the SR and thereby the driving force for Ca2+ release, φ, and Δ[Ca2+] at any distance from the channel. With a resting, Ca-free BAPTA concentration of 6.5 mm (the average value given in the Results), the estimated value of λCa is 21.5 nm (eqn (B14) in Pape et al. (1995), assuming DCa = 3 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 and a rate constant of Ca binding to BAPTA of 1 × 108m−1 s−1; from Kits et al. 1999). If the Ca regulatory site is 30 nm away - the distance between neighbouring SR Ca2+ release channels - BAPTA should reduce Δ[Ca2+] to 0.25 (e−30/21.5) of its value in the absence of BAPTA, which should produce the equivalent effect of reducing [CaSR] from 400 to 100 μm (100/400 = 0.25). Therefore, if the > 2-fold increase in release permeability (or fCa) when [CaSR] increases from 100 μm to 400 μm is due to the activation of neighbouring channels by CICR, the addition of 8 mm BAPTA should have decreased fCa to < 0.5 of its value in the absence of BAPTA when [CaSR] was 400 μm. If the increase in release permeability when [CaSR] increases from 100 μm to 400 μm is due to an auto-regulatory mechanism caused by released Ca2+ binding to a modulatory site on the same channel, eqn (9) indicates that 8 mm BAPTA should have little if any effect. For example, if the site is within 5 nm of the pore - which could be on the same Ca2+ release channel given its large size - BAPTA would reduce Δ[Ca2+] to no more than 0.77 (e−5/19.4) of its value in the absence of BAPTA.

In summary, the finding that there was essentially no effect of BAPTA on fCa indicates that neighbouring channels are not activated by CICR within a Ca2+ release site when [CaSR] is 300-500 μm. This finding also indicates that Ca2+ released from a Ca2+ release channel activated by its associated voltage sensor somehow augments the total Ca2+ flux through the channel. In contrast to an assumption made in some modelling studies (Stern et al. 1997; Ríos & Stern, 1997), such an auto-regulatory mechanism means that a Ca2+ release channel activated by its associated voltage sensor can also be modulated by Ca2+.

Comparison with results from isolated SR Ca2+ release channels

Tripathy & Meissner (1996) studied the effect of Ca2+ flux on the open probability (Po) of SR Ca2+ release channels from mammalian muscle reconstituted in planar lipid bilayers. They found a significant increase in Po as the Ca2+ flux increased from very small values. The Po vs. Ca2+ flux relationship reached a maximum followed by a decrease as the Ca2+ flux increased further. The effects on Po were mainly due to a modulation of the mean open time of the channels, as opposed to the frequency of openings or the unitary conductance of the channel. The similarity of this bimodal dependence on Ca2+ flux to that obtained with small depolarisations (Pape & Carrier, 1998; Fig. 2B and Fig. 3A in this article) suggests that the same Ca binding sites are involved in regulating Ca2+ release in isolated SR Ca2+ release channels activated by ATP and in SR Ca2+ release activated by surface/T-system depolarisation. This similarity, therefore, suggests that the auto-regulation of a Ca2+ release channel activated by its associated voltage sensor by the Ca2+ flux through the channel probably involves modulation of the open time of the channel.

Lack of effect of BAPTA on plateau phase of fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship

Previous results indicate that 8 mm BAPTA does not influence fCa when [CaSR] is in the plateau region of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship ([CaSR] > 1000 μm). This was done by comparing the ratio of fCa at -60 mV determined 50-60 min after adding BAPTA, to the value just before adding BAPTA, with the corresponding ratio in control experiments (row 4 of Table 1 of Pape et al. 2002). The internal solutions all had the same nominal [Ca2+] in order to maintain an approximately constant [CaSR]. The increase of fCa in the BAPTA experiments of 1.54 (s.e.m. = 0.27; N = 7) was not significantly different from that in the control experiment of 1.90 (s.e.m. = 0.25; N = 5). The corresponding increase in fCa in the three experiments in this article in which Ca was not removed until 57-61 min after adding BAPTA was 2.34 (s.e.m. = 0.15; cf. Fig. 3C). This increase was not significantly different from that of the earlier BAPTA experiments, or of the earlier control experiments. Since the conditions of the BAPTA experiments in the two studies were essentially identical, the data from the two sets of experiments can be combined giving an average increase in fCa of 1.78 (s.e.m. = 0.23; N = 10), which is very similar to the control value of 1.90 above. In summary, additional results from this study support the earlier conclusion that a 50-60 min exposure to 8 mm BAPTA in the internal solution does not significantly affect release permeability at -60 mV when [CaSR] is in the plateau region of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship.

Effect of BAPTA on the falling phase of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship

Evaluation of the effects of BAPTA on the falling phase of the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship (as [CaSR] increased from 500 to > 1000 μm) indicates that BAPTA produced either no effect or a modest increase in fCa, as indicated by a possible increase in [CaSR]1/2 (column 7 of Table 1, and second to last section of Results). The possible increase in [CaSR]1/2 would be consistent with a decrease in Ca inactivation over intermediate values of [CaSR].

It is important to note that BAPTA never produced a decrease in fCa at -60 mV over the full range of [CaSR] values investigated (300-3000 μm). This indicates that neighbouring channels are not recruited by CICR in response to small depolarisations. The results do not, however, entirely rule out the possibility that neighbouring channels could be recruited at intermediate and larger values of [CaSR], but that this is prevented by their becoming inactivated before they have a chance to be activated by CICR. A modest increase in [CaSR]1/2 could be due to a decrease in this pre-inactivation.

Comparison with results at higher voltages

Recent results (Pape et al. 2002) support the hypothesis of Ríos and colleagues (Ríos & Pizarro, 1988, and subsequent work reviewed by Stern et al. 1997) that Ca2+ release at higher voltages is enhanced due to the recruitment of neighbouring channels by CICR. An explanation for why this enhancement is not seen with smaller depolarisations is that it requires a threshold above the Δ[Ca2+] produced by just one open channel but below that produced by the summation from two immediately adjacent Ca2+ release channels activated by their associated voltage sensors. Therefore, it is only seen at higher voltages when the density of voltage-activated sites is greater. This explanation requires that an isolated Ca2+ release channel activated by its associated voltage sensor does not recruit neighbouring channels by CICR. Results in this article provide support for this condition.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant MT-15034 and a grant from Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec.

APPENDIX A

Estimation of [CaSR]R and [CaSR] in the presence of BAPTA

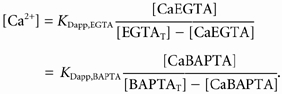

This appendix describes the estimation of Δ[CaBAPTA]max, which is used to estimate [CaSR]R with eqn (4). The approach is, for the most part, the same as that described in Appendix A of Pape et al. (2002). In both cases, [CaBAPTA] was estimated from the equilibrium binding functions:

|

(A1) |

Briefly, [CaEGTA]R and [CaBAPTA]R (the subscript R refers to resting) were evaluated from an estimate of [Ca2+]R. [CaBAPTA] after a fully depleting stimulation was obtained from eqn (A1) and the corresponding value of [CaEGTA] given by [CaEGTA]R + Δ[CaEGTA]max. Δ[CaBAPTA]max was then given by the difference between the final and resting values of [CaBAPTA].

The pH-sensitive values of KDapp,EGTA and KDapp,BAPTA in eqn (A1) were estimated, respectively, from eqn (A9) in Pape et al. (1995) and eqn (A5) in Pape et al. (2002) using pHR and pHR + ΔpH for resting and final conditions, respectively. [EGTAT] was assumed to be 20 mm, its concentration in the end-pool solutions. [BAPTAT] was estimated from the time after addition of 8 mm BAPTA to the end pools and the solution of the diffusion equation (e.g. eqn (6) on p. 47 of Maylie et al. 1987), assuming that BAPTA is not sequestered or bound to myoplasmic sites.

DBAPTA, the free diffusion constant of BAPTA (MW = 472), is expected to range from 1.2 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 to half this value, 0.6 × 10−6 cm2 s−1. The higher value was extrapolated from the free diffusion constant of the Ca indicator dye purpurate-3,3′-diacetic acid (MW = 380) measured in cut fibres of 1.31 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 (Hirota et al. 1989) and that of ATP (MW = 507) measured in skinned fibres of 1.2 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 (Kushmerick & Podolsky, 1969). Unlike most indicators, only a small fraction of purpurate-3,3′-diacetic acid is sequestered or bound to myoplasmic constituents. (The extrapolation between substances of different molecular weight assumed that the diffusion constant is proportional to MW−⅓, as predicted by the Stokes-Einstein equation.) The smaller value for DBAPTA was based on the value for Dfura-2, the free diffusion constant of fura-2 (MW = 637), of 0.54 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 estimated in cut fibres (Pape et al. 1993). Since only a relatively small fraction of fura-2 appears to be sequestered or bound to myoplasmic constituents (27 % on average; Pape et al. 1993) and since the value of Dfura-2 above took this binding into account, it is not clear why Dfura-2 was so low. Whatever the explanation for the low value of Dfura-2, it may also apply to DBAPTA since a large part of the structure of fura-2 is the same as BAPTA. In summary, the two assumed values of DBAPTA - 1.2 and 0.6 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 - cover the range in which the actual value of DBAPTA is likely to fall.

In order to assess the effect of the uncertainty in DBAPTA, one section of the Results evaluated [CaSR] with both the high and low estimates of DBAPTA. Unless indicated, however, DBAPTA was set to the mean value of 0.9 × 10−6 cm2 s−1. Calculations were not done to take into account possible binding of BAPTA to myoplasmic sites. As noted above, BAPTA's structure is the same as a large part of the structure of fura-2, and fura-2 appears to have a relatively small bound component. In addition, the measured time course of Δ[CaEGTA] about one hour after adding BAPTA was similar to that expected if the concentrations of BAPTA and EGTA were about the same as their end-pool values: 8 and 20 mm, respectively (Fig. 1D of Pape et al. 2002). Unless both BAPTA and EGTA bind to the same extent, and if the bound forms are both able to complex Ca, this latter result also suggests that binding of BAPTA to myoplasmic sites is relatively minor.

Previously, [Ca2+]R was estimated with eqn (A1) assuming that [CaEGTA]R at the optical site was the same as that in the end pools (Pape et al. 1995, 2002). The approach was different in this study since Ca was removed from the end pools midway through the experiments. The assumption about [CaEGTA]R would not be appropriate in this case since the amount of Ca at the optical recording site in the middle of the fibre should decrease relatively slowly following removal of Ca from the end pools due to diffusional delays and the action of SR Ca2+ pumps. The approach adopted in this study was influenced by the approximately linear relationship between the experimentally estimated [Ca2+]R and [CaSR]R values shown in Fig. 9 of Pape et al. (1995). Based on their results indicating that [CaSR]R was about 3000 μm when [Ca2+]R was 0.1 μm, it is assumed that

| (A2) |

Since [CaSR]R is not initially known, the following iterative procedure was employed in which estimates of [CaSR]R are fed back into eqn (A2):

[Ca2+]R was assumed to be zero for the 1st iteration or the value obtained in step 6 below

[CaEGTA]R and [CaBAPTA]R were determined from this value of [Ca2+]R with eqn (A1)

[CaEGTA] after all of the Ca was released was given by [CaEGTA]R plus the measured value of Δ[CaEGTA]max

[CaBAPTA] was obtained from this value and eqn (A1) and Δ[CaBAPTA]max was then obtained by subtracting [CaBAPTA]R

[CaSR]R was given by Δ[CaEGTA]max + Δ[CaBAPTA]max (i.e. eqn (4))

if another iteration was done, [Ca2+]R was obtained from this value of [CaSR]R and eqn (A2) and steps 1-5 were repeated.

This procedure generally required only two or three iterations to reach a stable value of [CaSR]R and five iterations were generally used. It is noted that the main effect of [Ca2+]R on Δ[CaBAPTA]max is to change the resting concentration of Ca-free BAPTA, the form that is available to complex Ca during the stimulation. The final results were fairly insensitive to how [Ca2+]R was estimated, as evidenced by very little change in the fCa vs. [CaSR] relationship when the scaling factor in eqn (A2) was increased or decreased by a factor of 2 (not shown).

Values of [CaSR] in this article generally refer to the SR Ca content before the pulse to -60 mV, which is close to but not the same as [CaSR]R if the pulse to -60 mV was preceded by pulses to -70 and -65 mV, as was the case in about half of the experiments. In this case, Δ[CaBAPTA] after the first two pulses was estimated with the same procedure except that Δ[CaEGTA] instead of Δ[CaEGTA]max was used. [CaSR] was then obtained from eqns (3) and (5). This procedure was also used in Appendix B to estimate Δ[CaBAPTA] for use in eqn (7), which was used to assess errors in fCa.

APPENDIX B

Possible errors in estimating fCa

This appendix assesses four methodological errors in the estimate of fCa associated with pulses to -60 mV when BAPTA is present. The errors are assessed for the same stimulations used for column 3 of Table 1. One error is that fCa estimated with eqn (8) (in which only the Δ[CaEGTA] is used) overestimates the actual value of fCa given by eqn (7), which includes the contributions of Δ[CaBAPTA] to Δ[CaT]. This error - applicable to the BAPTA experiments only - results in an overestimate of the actual fCa on average of only 2.5 %. (A similar value for this error was obtained in Appendix A of Pape et al. 2002 for fCa values in the plateau range of [CaSR] values: 1500-3000 μm.) The reason this error is small is that both Δ[CaBAPTA] and Δ[CaEGTA] are approximately proportional to Δ[Ca2+] so that Δ[CaEGTA] is approximately proportional to Δ[CaT], even in the presence of BAPTA.

A second error is that Ca2+ binding to BAPTA also releases protons, though much less compared with EGTA (0.2 protons per Ca bound on average vs. two for EGTA). This means that a portion of the ΔpH signal was due to Ca binding to BAPTA as opposed to EGTA. The approach for evaluating this error assumed that the measured ΔpH signal (denoted ΔpHmeasured) is given by the sum of pH changes associated with Ca binding to EGTA and BAPTA: ΔpHEGTA and ΔpHBAPTA, respectively. The first step in evaluating this error was to estimate Δ[CaBAPTA] as described in Appendix A assuming that ΔpHEGTA was ΔpHmeasured. The first estimate of ΔpHBAPTA (obtained from Δ[CaBAPTA] = -βΔpHBAPTA/0.2, which is analogous to eqn (2)) was then subtracted from ΔpHmeasured to give a new estimate of ΔpHEGTA and, thereby, Δ[CaEGTA] with eqn (2). Several iterations of the calculation of Δ[CaBAPTA] with new corrected estimates of Δ[CaEGTA] were done. The values of Δ[CaBAPTA] and Δ[CaEGTA] converged to close to their final values within two iterations. (The pH values used to calculate KDapp,EGTA and KDapp,BAPTA in eqn (A1) were based on ΔpHmeasured as opposed to ΔpHEGTA, since only the value and not the source of ΔpH was important.) The values of Δ[CaBAPTA] and Δ[CaEGTA] were then used to assess the error in fCa in eqn (8)vs.eqn (7) as before. The error reduced the overestimation of fCa in the previous paragraph from 2.5 to 2.4 % (i.e. only a 0.1 % change). The error associated with proton release from BAPTA is small because of the small effect on the ΔpH signal and because it reduced the numerator and denominator of eqn (7) by about the same factor.

A third error is that Δ[CaEGTA]after and thereby fCa was underestimated since the duration of the OFF pulses to -90 mV (600-1000 ms) was not sufficient to allow for complete redistribution of Ca from BAPTA to EGTA (cf. exponential fit and final level in Fig. 1C). The estimated average error was 12.3 % (s.e.m. = 3.4 %; N = 5). As this is an underestimation of fCa in the BAPTA experiments only, it strengthens the conclusion that BAPTA did not produce a decrease in fCa.

A fourth error in the estimation of fCa concerns the possibility that a significant amount of Ca is released after the pulse to -60 mV. As seen in the control experiment in Fig. 2A and B, the turn-off of release becomes slower as [CaSR] decreases below 300 μm resulting in a significant amount of Ca2+ release after the fibre is repolarised to -90 mV. A likely explanation for this slower turn-off is that voltage activation of Ca2+ release turns off more slowly. As indicated in Fig. 8 and Fig. 9 of Pape et al. (1998), decreasing [CaSR] slows the turn-off of Ca2+ release and intramembranous charge movement following a short pulse to -20 mV. Moreover, there was a correspondence between the time course of the turn-off of Ca2+ release and that of intramembranous charge movement. In the control experiments, extra release during the repolarisation phase produced only about a 10 % increase in fCa compared with fCa evaluated from Δ[CaEGTA] just after the end of the pulse when [CaSR] was 300-500 μm (cf. middle trace in Fig. 2A and open circles vs. cross symbols in Fig. 2B). It seems reasonable to expect that the same 10 % effect would be present in the BAPTA experiments. This is because BAPTA should have little effect on Δ[Ca2+] at a site on the voltage sensor associated with an open SR Ca2+ release channel, an assessment based on solutions of the diffusion equation (cf. Discussion of this article). If the error were the same in both the control and BAPTA experiments, the effects would have been the same on the relative increase in fCa as [CaSR] decreased from 1500-3000 μm to 300-500 μm (column 4 of Table 1). If BAPTA did slow the turn-off of Ca2+ release, it would enhance the amount of Ca2+ released after the pulse, thereby increasing fCa and masking a possible decrease of release permeability during the pulse. It is noted that such a decrease in release permeability would be in the opposite direction of the relatively large error above (the third error), estimated to produce a 12.3 % underestimation in fCa. Therefore, it seems very unlikely that this fourth error could have changed the assessment that BAPTA had little if any effect on the release permeability when [CaSR] was 300-500 μm.

In summary, errors in the estimate of fCa with BAPTA present should be relatively small.

References

- Block BA, Imagawa T, Campbell KP, Franzini-Armstrong C. Structural evidence for direct interaction between the molecular components of the transverse tubule/sarcoplasmic reticulum junction in skeletal muscle. Journal of Cell Biology. 1988;107:2587–2600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler WK, Hui CS. Membrane capacitance in frog cut twitch fibers mounted in a double Vaseline-gap chamber. Journal of Physiology. 1990;96:225–256. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González A, Kirsch WG, Shirokova N, Pizarro G, Brum G, Pessah IN, Stern MD, Cheng H, Ríos E. Involvement of multiple intracellular release channels in calcium sparks of skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2000;97:4380–4385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070056497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B, Campbell DT. An improved Vaseline gap voltage clamp for skeletal muscle fibers. Journal of General Physiology. 1976;67:265–293. doi: 10.1085/jgp.67.3.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota A, Chandler WK, Southwick PL, Waggoner AS. Calcium signals recorded from two new purpurate indicators inside frog cut twitch fibers. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;94:597–631. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.4.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui CS, Chandler WK. Intramembranous charge movement in frog cut twitch fibers mounted in a double Vaseline-gap chamber. Journal of General Physiology. 1990;96:257–297. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving M, Maylie J, Sizto NL, Chandler WK. Intrinsic optical and passive electrical properties of cut frog twitch fibers. Journal of General Physiology. 1987;89:1–40. doi: 10.1085/jgp.89.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong D-S, Pape PC, Chandler WK. Calcium inactivation of calcium release in frog cut muscle fibers that contain millimolar EGTA or fura-2. Journal of General Physiology. 1995a;106:337–388. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong D-S, Pape PC, Chandler WK. Effect of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium depletion on intramembranous charge movement in frog cut muscle fibers. Journal of General Physiology. 1995b;106:659–704. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.4.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kits KS, De Vlieger TA, Kooi BW, Mansvelder HD. Diffusion barriers limit the effect of mobile calcium buffers on exocytosis of large dense cored vesicles. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:1693–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77328-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MG, Cheng H, Santana LF, Jiang Y-H, Lederer WJ, Schneider MF. Two mechanisms of quantized calcium release in skeletal muscle. Nature. 1996;379:455–458. doi: 10.1038/379455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick MJ, Podolsky RJ. Ionic mobility in muscle cells. Science. 1969;166:1297–1298. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3910.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maylie J, Irving M, Sizto NL, Chandler WK. Comparison of arsenazo III optical signals in intact and cut frog twitch fibers. Journal of General Physiology. 1987;89:41–81. doi: 10.1085/jgp.89.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Concentration profiles of intracellular calcium in the presence of a diffusible chelator. In: Heinemann U, Klee M, Neher E, Singer W, editors. Calcium Electrogenesis and Neuronal Functioning. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1986. pp. 80–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC. pH in cut frog muscle fibers. Biophysical Journal. 1990;57:347a. [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Carrier N. Effect of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) calcium content on SR calcium release elicited by small voltage-clamp depolarizations in frog cut skeletal muscle fibers equilibrated with 20 mm EGTA. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;112:161–179. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Carrier N. Calcium release and intramembranous charge movement in frog skeletal muscle fibres with reduced (<250 μm) calcium content. Journal of Physiology. 2002;539:253–266. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Fénelon K, Carrier N. Extra activation component of calcium release in frog muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 2002;542:867–886. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Jong D-S, Chandler WK. Calcium release and its voltage dependence in frog cut muscle fibers equilibrated with 20 mm EGTA. Journal of General Physiology. 1995;106:259–336. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Jong D-S, Chandler WK. Effects of partial sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium depletion on calcium release in frog cut muscle fibers equilibrated with 20 mm EGTA. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;112:263–295. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Jong D-S, Chandler WK, Baylor SM. Effect of fura-2 on action potential-stimulated calcium release in cut twitch fibers from frog muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 1993;102:295–332. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos E, Brum G. Involvement of dihydropyridine receptors in excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Nature. 1987;325:717–720. doi: 10.1038/325717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos E, Pizarro G. Voltage sensors and calcium channels of excitation-contraction coupling. News in Physiological Sciences. 1988;3:223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos E, Stern MD. Calcium in close quarters: microdomain feedback in excitation-contraction coupling and other cell biological phenomena. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 1997;26:47–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MF. Ca2+ sparks in frog skeletal muscle: generation by one, some, or many SR Ca2+ release channels? Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:365–371. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MF, Chandler WK. Voltage dependent charge movement in skeletal muscle: a possible step in excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 1973;242:244–246. doi: 10.1038/242244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MF, Simon BJ. Inactivation of calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in frog skeletal muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1988;405:727–745. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern MD. Buffering of calcium in the vicinity of a channel pore. Cell Calcium. 1992;13:183–192. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(92)90046-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern MD, Pizarro G, Ríos E. Local control model of excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:415–440. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe T, Beam KG, Powell JA, Numa S. Restoration of excitation-contraction coupling and slow calcium current in dysgenic muscle by dihydropyridine receptor complementary DNA. Nature. 1988;336:134–139. doi: 10.1038/336134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy A, Meissner G. Sarcoplasmic reticulum lumenal Ca2+ has access to cytosolic activation and inactivation sites of skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:2600–2615. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79831-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]