Abstract

The responses of vanilloid receptor (VR) channels to changing membrane potential were studied in Xenopus oocytes and rat dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. In oocytes, capsaicin-evoked VR currents increased instantaneously upon a step depolarization and thereafter rose biexponentially with time constants of ≈20 and 1000 ms. Similarly, upon repolarization the current abruptly decreased, followed by a biexponential decay with time constants of ≈4 and 200 ms. Qualitatively similar effects were observed in single channel recordings of native VR channels from DRG neurons and with endogenous VR activators, including heat (43 °C), H+, anandamide and protein kinase C (PKC). The magnitude of the time-dependent current rise increased with membrane depolarization. This effect was accompanied by an increase in the relative proportion of the fast kinetic component, A1. In contrast, the time constants of the activation and deactivation processes were not strongly voltage dependent. Increasing the agonist concentration both reduced the magnitude of the current rise and increased its overall rate, without significantly altering the deactivation rate. In contrast, PKC both speeded the current rise and slowed its decay. These results suggest that voltage interacts with agonists in a synergistic manner to augment VR current and this mechanism will be enhanced under conditions of inflammation when VRs are likely to be phosphorylated.

The capsaicin or vanilloid receptor type 1 (VR1) is believed to transduce a variety of noxious stimuli into pain signalling. VR1 is a non-selective cation channel directly activated by heat, H+, anandamide and capsaicin, the pungent ingredient in hot chilli peppers (Caterina et al. 1997; Tominaga et al. 1998; Caterina & Julius, 2001). Upon encountering these noxious stimuli, VR1 channels located in sensory nerve endings open and depolarize the membrane, thereby initiating action potentials that propagate to the spinal cord and brain. However, the current-voltage properties of VR1 appear to oppose this mechanism. VR1 currents evoked by a variety of agonists, including capsaicin, protons and anandamide, exhibit pronounced outward rectification, passing ≈5- to 10-fold more current at positive compared to negative membrane potentials (Zygmunt et al. 1999; Gunthorpe et al. 2000; Premkumar & Ahern, 2000). This property would limit the activation of VRs near the cell resting potential. In contrast, VR activity would be greatly enhanced when the cell is simultaneously depolarized, for example, during action potentials. Capsaicin-sensitive neurons comprise lightly myelinated Aδ-fibres and unmyelinated c-fibres. Aδ-fibres may spike at up to 30 Hz, while c-fibre nociceptors generally have low discharge rates (< 5 Hz), but relatively broad action potentials (Zhang et al. 1997; Abdulla & Smith, 2001). However, c-fibres and capsaicin-sensitive vagal afferents can spike briefly at up to 60 Hz in response to capsaicin treatment (Coleridge et al. 1965; LaMotte et al. 1992). Thus, understanding how VRs respond to changing membrane potential is an important consideration in elucidating their physiological role. In this study we have investigated the voltage-dependent properties of native and cloned VRs activated by several types of agonists. Our results show that VRs activated by capsaicin and endogenous signalling pathways exhibit time- and voltage-dependent activation and deactivation properties. Further, the magnitude and rates of these time- and voltage-dependent responses depends on the agonist, its concentration and the phosphorylation state of VR. Some of these results have been previously published in an abstract form (Ahern et al. 2000).

Methods

Tissues were harvested using protocols approved by the Southern Illinois University Animal Use and Care Committee. To obtain embryonic dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons, pregnant rats were anaesthetized with halothane (5 %) on day 18 of gestation and killed by decapitation. Embryos were removed and decapitated. Oocytes were harvested from adult, female Xenopus laevis anaesthetized with tricaine methanesulfonate (0.5 g l−1). Frogs were humanely killed following the final collection of oocytes.

Oocyte electrophysiology

Defolliculated oocytes were injected with 30-50 ng of VR1 cRNA. Double electrode voltage clamp was performed using a Warner amplifier (OC725C, Warner Instruments Inc., Hamden, CT, USA) with 100 % DC gain. All the experiments were performed at 21-23 °C. Oocytes were placed in a Perspex chamber and continuously superfused (5-10 ml min−1) with Ca2+-free Ringer solution containing (mm): 100 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 5 Hepes, 1.5 EGTA, and titrated to pH 7.35 with ≈5 mm NaOH. For solutions < pH 6.0, Hepes was replaced with 10 mm Mes. Ca2+-free conditions were used to minimize VR1 tachyphylaxis and contamination from Ca2+-activated Cl− currents. Electrodes were filled with 3 m KCl and had resistances of 0.5-1 MΩ. The standard voltage protocol consisted of incremental 20 mV pulses of 5 s duration from a holding potential of −80 to +80 mV. Unless otherwise indicated, leak currents measured under control conditions were subtracted from agonist-induced currents.

DRG electrophysiology

Dorsal root ganglia were isolated from embryonic day (E)18 rats, triturated and cultured in Neurobasal/B-27 (Life Technologies) and 10 % fetal bovine serum on poly-d-lysine-coated glass coverslips. This procedure generated clusters of neurons interspersed among a layer of glia and fibroblasts. Cells were used after 5 days in culture. For excised outside-out patches, the bath solution contained (mm): 140 sodium gluconate, 10 NaCl, 1 or 2 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes, pH 7.3, and the pipette solution contained (mm): 140 sodium gluconate, 10 NaCl, 1 or 2 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 2 K2ATP, pH 7.3. For cell-attached recording, external sodium gluconate was replaced with potassium gluconate to eliminate membrane potential. Patches that showed activity at 0 mV indicating the presence of K+ channels were discarded. For analysis the current signal was passed through a 2.5 kHz, low-pass, eight pole Bessel filter and digitized at 5 kHz.

Data analysis

The settling time of the voltage clamp in oocytes was ≈2 ms. The rising or decaying phase of VR current was then fitted with an exponential function of the form: where A and τ are amplitudes and time constants, respectively, t is time and c is residual current. Curve fitting was performed with Origin software (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). Data are given as means ± s.e.m. and statistical significance was evaluated using Student's t test.

Chemicals

Capsaicin, anandamide, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu) were obtained from Sigma. Drugs were prepared as stock solutions in ethanol (100 mm for capsaicin and anandamide, and 2 mm for the phorbol esters) and diluted into physiological solution prior to the experiments.

Results

Voltage dependence of VR1 expressed in oocytes

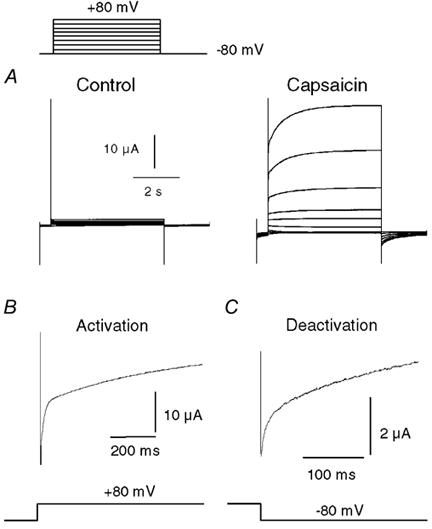

VR1 activity was studied in oocytes using a two-electrode voltage clamp technique. A Ca2+-free solution was used to minimize VR desensitization and tachyphylaxis. Under these conditions relatively stable currents were obtained during application of capsaicin (500 nm). To explore VRs for possible voltage-dependent properties, we examined the response of capsaicin-activated current to a series of 5 s depolarizing pulses from −80 to +80 mV. The voltage protocol was initiated after the current had reached a steady state (≈30-40 s of application). Figure 1A shows that the current grew substantially during the course of the 5 s pulse. Upon repolarization to −80 mV, the currents slowly relaxed as reflected by the tail currents. Figure 1B and C, respectively, shows these activation (+80 mV) and deactivation (-80 mV) processes on an expanded time scale. Upon depolarization the current jumped almost instantaneously (following the capacitive transient), and thereafter increased in two phases. Biexponential fits to this rising component in seven experiments gave time constants of 17 ± 2 and 928 ± 96 ms with the fast component comprising 34 ± 4 % of the rise. Similarly, upon repolarization the current relaxed with a biexponential time course, somewhat faster than that of activation. The mean time constants were 4 ± 2 and 232 ± 59 ms with the fast component comprising 70 ± 2 % of the fall. A more detailed analysis of kinetics is described below. These results are qualitatively similar to the results of an earlier study of VR1 expressed in HEK 293 cells (Gunthorpe et al. 2000).

Figure 1. Voltage modulation of capsaicin-activated currents in whole oocytes.

A, family of current traces showing the response of a VR1-expressing oocyte to a series of voltage steps (in 20 mV increments) from −80 to +80 mV, either in the absence or in the presence of 500 nm capsaicin. B, expanded trace from the data in A showing the rising phase of current after the voltage step to +80 mV. C, expanded trace showing the tail current recorded at −80 mV after a 5 s step to +80 mV.

Voltage-dependent properties of single VR channels in DRG neurons

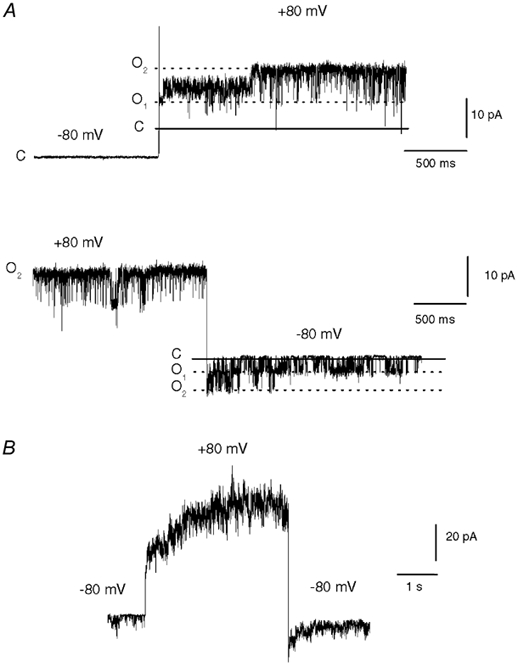

To confirm that these properties were unambiguously attributable to VRs and also found in a native system, we turned to single channel recordings from DRG neurons. The conductance and open probability of single VR channels exhibit a distinctive voltage dependence. Both of these parameters increase with depolarization and together these effects account for the rectification seen in the whole cell current (Oh et al. 1996; Premkumar et al. 2002). Because DRG neurons also express numerous voltage-gated channels that may contaminate the capsaicin current during a voltage step, we used patches that only contained VR channels based on their characteristic conductance, rectification properties and sensitivity to vanilloids. Figure 2A shows VR channel activity in a cell-attached patch (the pipette solution contained 500 nm capsaicin) containing two VR channels during voltage steps between −80 and +80 mV. The top trace shows that there was no activity at −80 mV until the step to +80 mV, where two channels opened in succession (note that one of these channels appears to initially enter a subconductance state). The bottom trace shows that the channels exhibited a very high open probability at +80 mV and this declined following the hyperpolarizing step. Figure 2B shows the effect of stepping the voltage from −80 to +80 mV in an outside patch containing four to five VR channels activated with 500 nm capsaicin. The current rose during the depolarization step and declined upon repolarization, exactly paralleling the increase seen with the cloned VR1 in whole cell currents. A biexponential fit to the rising current gave time constants of 16 and 1465 ms, very similar to the average time course found in whole oocytes. Thus, the voltage- and time-dependent properties of VR1 are also found in native receptors and are discernible at the single channel level. These data also agree with a preliminary study by Piper & Docherty (1999); these authors reported a voltage and time dependence in capsaicin-evoked currents from sensory neurons, but found that these changes proceeded with monoexponential kinetics.

Figure 2. Voltage modulation of single VR channels in DRG neurons.

A, current traces from a cell-attached patch from a DRG neuron showing the response of two VR channels to voltage steps between −80 and +80 mV. The continuous and dashed lines indicate the closed (C) and two open current levels (O1 and O2), respectively. Note that one channel initially opens to a subconductance level after the depolarization step (top trace). The pipette solution contained 500 nm capsaicin and the bath solution contained a high [K+] to eliminate the cell membrane potential. B, an outside-out patch from a DRG neuron containing four to five VR channels activated by 500 nm capsaicin during a step from −80 to +80 mV. A double exponential fit to the rising current gave time constants of 16 and 1465 ms.

Kinetics of voltage-dependent VR1 current rise in oocytes

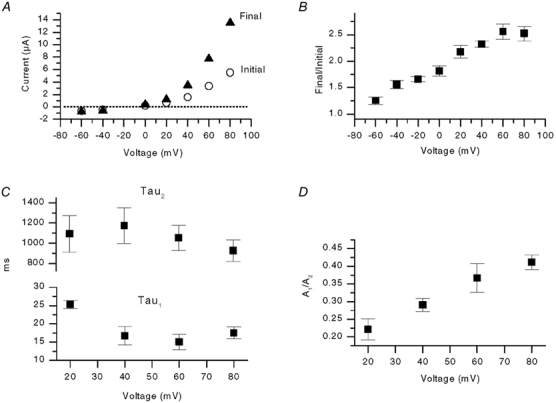

We next explored the relationship between the current rise and membrane voltage. Figure 3A shows a plot of initial current (≈2 ms, after the capacitive transient) and final current (5 s) at different holding potentials. Figure 3B summarizes the mean fractional increase (i.e. final current divided by initial current) in five oocytes. The magnitude of the current rise increased with voltage. Figure 3C and D shows the amplitudes and time constants for the biexponential fits as a function of voltage. The relative proportion of the fast component (A1) increased with depolarization, and A1 was not detectable at negative potentials. In contrast, the time constants were little affected over the same range of positive voltages.

Figure 3. Voltage dependence and kinetics of VR current rise in oocytes.

A, plot of instantaneous current and final current (5 s later) versus voltage from one experiment. B, mean normalized rise (final current/initial current) versus voltage from five oocytes activated by 500 nm capsaicin. C, plot of the time constants, τ1 and τ2, versus voltage (n = 7). The rising phase of current was fitted with a double exponential function described in the Methods. D, plot of the ratio of the amplitude of the fast component of the rising phase (A1) and the slower component (A2) versus voltage (n = 6).

Kinetics of voltage-dependent VR current deactivation

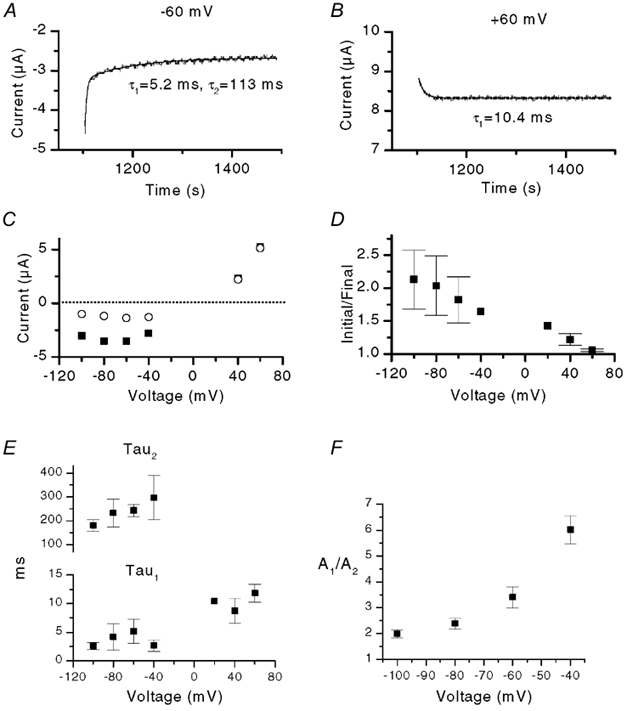

To investigate the voltage dependence of the deactivation process we used a stimulus protocol consisting of a prepulse to +80 mV followed by test pulses ranging between −100 and +60 mV. Figure 4A and B shows two such tail currents recorded at −60 and +60 mV in the presence of 500 nm capsaicin. The magnitude of the deactivation was much greater at −60 mV compared with +60 mV. Figure 4C shows a plot of the peak or initial tail current (filled squares) and the final tail current (open circles, measured at 500 ms where current had mostly decayed) at different voltages. There is a marked difference in the two curves at negative potentials, but not at positive potentials. This reflects the greater deactivation at negative potentials, or conversely, the greater potentiation of the steady state current. Figure 4D summarizes this relative potentiation (expressed as initial current divided by final current) as a function of voltage; there was an ≈2-fold increase at −100 mV and this potentiation decreased in a near linear relationship with voltage. These results illustrate an important property of VRs; at negative potentials the current is substantially enhanced after a preceding depolarization. Others and we have suggested that this property may have important implications for VR activation during spiking (Ahern et al. 2000; Gunthorpe et al. 2000).

Figure 4. Voltage dependence and kinetics of VR current deactivation in oocytes.

A and B, traces showing tail currents at −60 and +60 mV, respectively, after a 5 s pre-pulse to +80 mV. The continuous lines show double and single exponential fits, respectively, with time constants as indicated. Note that only a single exponential function is required to fit the data at +60 mV. C, the initial or peak tail current (▪) and the final current (500 ms later) (○) as a function of voltage from a single experiment. D, plot of initial/final tail current versus voltage from three oocytes. E, plot of the time constants, τ1 and τ2, versus voltage. The decaying phase of current was fitted with either a double or single exponential function as shown in A. Difference in values for τ1 between +60 mV and −100 to −40 mV were significant at P < 0.05. F, plot of the ratio of the amplitudes of the fast and slow components of the tail current (A1/A2) versus voltage (three oocytes).

We fitted exponential functions to the tail currents. At negative potentials the best fits were obtained with two exponentials; in contrast at positive potentials the currents were adequately fitted by a single exponential function (Fig. 4A, B and E). Values for τ1 were slightly greater at positive potentials, whereas there was little difference in values for both τ1 and τ2 over the voltage range −100 to −40 mV. In contrast, the relative proportion of A1 increased over this same voltage range (Fig. 4F). This mirrors the increase in A1 seen in the current activation (Fig. 3D). Thus, there is a progressive loss of the slower component of deactivation with increasing depolarization. This culminates in essentially no A2 at positive potentials.

Voltage-dependent properties of VR activated by endogenous agonists

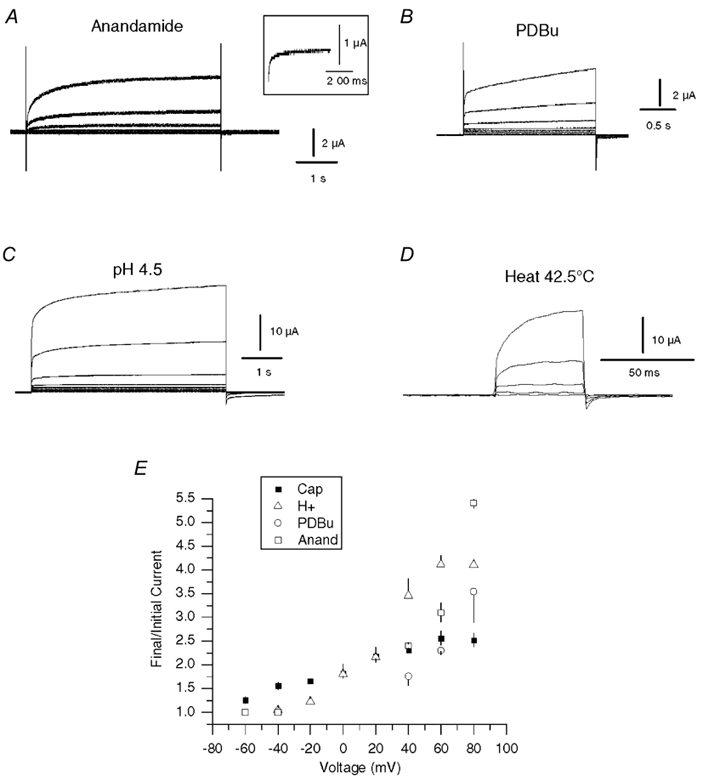

Although capsaicin is a useful tool to study VR function, it is not an endogenous ligand for the channel. The primary activators of VRs in the physiological setting are likely to be heat or elevated extracellular [H+] (Caterina & Julius, 2001). Other potential endogenous activators or signalling pathways include anandamide (Zygmunt et al. 1999; Smart et al. 2000), 5-lipoxygenase metabolites (prostanoids) (Hwang et al. 2000) and PKC-mediated phosphorylation (Premkumar & Ahern, 2000). These may be particularly important for modulating VRs located away from the periphery (e.g. central terminals of primary afferent nerves) or in non-nociceptive tissue. We therefore tested whether these endogenous agonists shared the voltage-dependent properties observed with capsaicin. Figure 5A-D shows the voltage dependence of VR1 currents in whole oocytes activated by anandamide, pH (4.5), heat (43 °C) and after PKC phosphorylation (pre-treatment with 1 μm phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate, PDBu, for 3 min). We used PDBu here rather than phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) because it has been suggested that PMA may directly activate VR1 (Chuang et al. 2001). The results with PMA and PDBu were indistinguishable, and in subsequent experiments (Fig. 7) we therefore used only PMA. The characteristic current rise and decay behaviour was seen with all of these agonists. Significantly, these results demonstrate that voltage-dependent modulation is a general property of channel activation and intrinsic to the VR channel. There were, however, notable differences between agonists in both the magnitude and the rates of the activation and deactivation processes and these are apparent in the traces shown in Fig. 5. In particular, anandamide and PKC produced comparatively small tail currents (the inset in Fig. 5A shows a tail current from a separate recording where the overall current was several times larger). In addition, the kinetics were markedly altered by heat. Best fits to the data in Fig. 5D gave values of 3 and 15 ms for the rise, and 2.5 and 37 ms for the decay. Similar values were obtained from another oocyte. Figure 5E compares the magnitude of the current rise versus voltage for capsaicin (500 nm from Fig. 2), pH (4.5), anandamide (10 μm) and following treatment with 1 μm PDBu. The current rise increased markedly with voltage and the responses to H+ and capsaicin, but not the other agonists, approached saturation at ≈+60 mV. The rises in H+-, anandamide- and PDBu-evoked currents exhibited steeper voltage dependencies and this was due to a greater maximal response at positive potentials and a decreased response at negative potentials. The steeper H+ response may reflect proton-mediated block of inward current, which is relieved by depolarization. The larger current rise with anandamide and PKC activation, both of which are relatively weak VR1 agonists, suggests that voltage can act in a synergistic manner to augment VR1 current.

Figure 5. Voltage modulation of VR1 currents activated by anandamide, H+, heat and PKC.

A-D, current traces from oocytes activated with anandamide (10 μm), PKC (pretreatment with 1 μm PDBu), H+ (pH 4.5) and heat (42.5 °C). Oocytes were depolarized with 20 mV incremental voltage steps from −80 to +80 mV, except for heat traces, which were depolarized to voltages between 0 and +80 mV, from a holding potential of −80 mV. Control traces in the absence of agonist were subtracted from the test data. For heat, traces obtained at 37 °C were subtracted from the 42.5 °C data. Tail currents with anandamide are not clearly seen. The inset in A shows expanded tail current from a separate recording with greater VR1 expression. E, the mean normalized rise (final current/initial current) versus voltage for oocytes activated with 500 nm capsaicin (n = 5), pH 4.5 (n = 4), after 1 μm PDBu (n = 4) and 10 μm anandamide (n = 3).

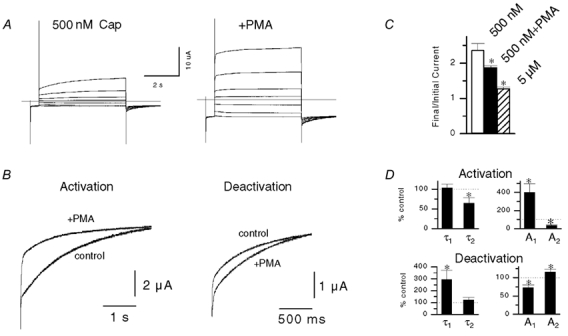

Figure 7. Regulation of voltage modulation by PKC.

A, response of an oocyte to 5 s depolarizing voltage steps (-80 to +60 mV, 20 mV steps) in the presence of 500 nm capsaicin before and after treatment with 500 nm PMA. B, normalized traces of the rising (+60 mV) and decaying components (-80 mV) before and after PMA. C, plot of relative current increase (final/initial current) during depolarization to +80 mV with 500 nm capsaicin before and after PMA treatment (n = 3, P < 0.05, paired t test). Data for 5 μm capsaicin (from Fig. 6) are shown for comparison. D, mean changes in the amplitude and time course of double exponential fits to currents at ±80 mV (n = 4 activation, n = 3 deactivation; * P < 0.05, paired t test).

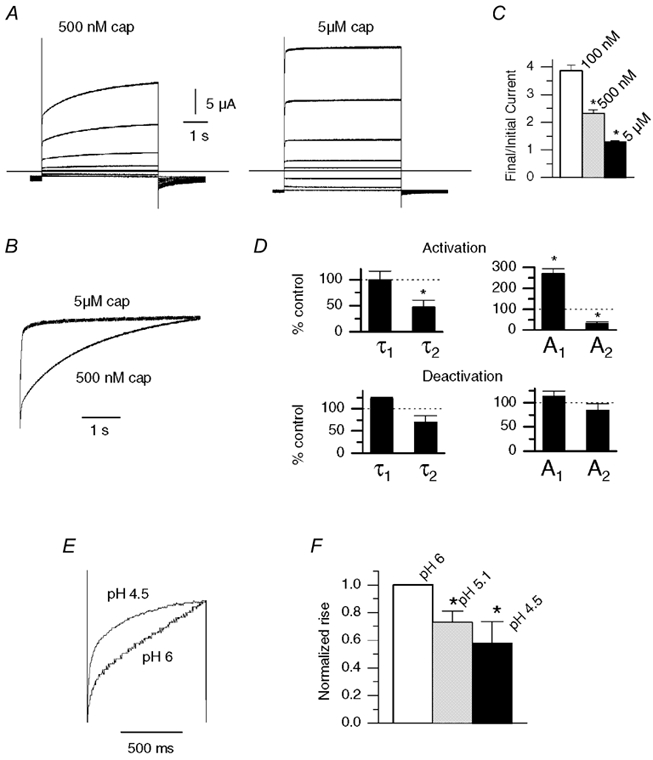

Effect of agonist concentration on voltage modulation

We next investigated whether the agonist concentration affected the voltage modulation. Figure 6A compares the response in an oocyte treated sequentially with 500 nm and 5 μm capsaicin. Scaled traces of the rising phase of current evoked at +80 mV (Fig. 6B) show that the rate of the current rise was greater with 5 μm compared with 500 nm capsaicin. In contrast, the magnitude of the rise was inversely proportional to concentration (Fig. 6C). The VR channels are more active at higher capsaicin concentrations and therefore presumably there is less scope for further activation by voltage. Similarly, the amplitude of the tail currents (the inverse of the rising currents) was greater with lower capsaicin concentrations and this can be clearly seen in Fig. 6A. Kinetic analysis of the current rise (Fig. 6D) revealed that the major effect of increased capsaicin concentration was to increase the relative proportion of the fast component (A1) without changing the time course. In addition there was a ≈2-fold increase in the rate of the slower component. The deactivation rate was also faster, but although there was a trend for a decrease in τ2 (P + 0.06) and an increase in A1 these differences were not significant.

Figure 6. Influence of capsaicin and H+ concentration on voltage modulation.

A, response of an oocyte to depolarizing voltage steps in the presence of 500 nm capsaicin and 5 μm capsaicin. B, scaled traces from data in A (+80 mV) show a faster rise with 5 μm capsaicin. C, plot of relative current increase (final/initial current) during 5 s depolarization to +80 mV with 100 nm (n = 3), 500 nm (n = 9) and 5 μm capsaicin (n = 6). Differences between all groups were significant (P < 0.01, two-sample t test) D, changes in time constants and amplitudes for double exponential fits to the current activation at +80 mV and to the current deactivation at −80 mV, after switching from 500 nm to 5 μm capsaicin (n = 4 for both groups, * P < 0.05, paired t test). E, current traces from oocytes during 1 s depolarizations to +80 mV with pH 6 and pH 4.5. F, the final/initial current (normalized to pH 6) with pH 4.5-6 (n = 4, * P < 0.05 paired t test versus pH 6).

We performed a similar set of experiment to assess the effects of [H+] on the voltage-dependent rise. Figure 6E shows scaled current traces from the rising phase of current during a voltage step to +80 mV in either pH 6 or pH 4.5 solutions. Figure 6F shows the normalized (with respect to pH 6) final/initial current with pH 6, 5.1 and 4.5. As with capsaicin, the there was less time-dependent change at higher proton concentrations. The tail current at pH 6 was too small to make meaningful comparisons in deactivation.

Effect of PKC on VR voltage modulation

The PKC pathway is implicated in inflammatory pain signalling (Malmberg et al. 1997; Cesare et al. 1999), and targeted disruption of the PKCε gene in mice results in a raised threshold for thermal hyperalgesia (Khasar et al. 1999). One substrate for PKCε is the VR1 channel (Numazaki et al. 2002). In turn, PKC-mediated phosphorylation may directly activate VR1 (Premkumar & Ahern, 2000) (as shown above in Fig. 5B), and/or increase the sensitivity of VR1 to its agonists (Premkumar & Ahern, 2000; Vellani et al. 2001; Zhou et al. 2001). Because PKC appears to play an integral role in VR1 activation, we considered the possibility that PKC may also regulate the voltage-dependent properties of VR1. Figure 7A shows capsaicin-activated currents during depolarizing steps before and after treatment with 500 nm PMA. As we have shown previously (Premkumar & Ahern, 2000), PMA treatment enhanced the magnitude of the currents. The voltage-dependent properties were also modified after PMA. There was a small but significant decrease in the magnitude of the current rise (Fig. 7C). This was much smaller than the effect of raised capsaicin concentration alone, even though 500 nm capsaicin and 5 μm capsaicin produced equivalent activation of VRs after PMA treatment. Scaled traces of the rising and falling phases (Fig. 7B) show that PMA increased the rate of the current rise, and conversely, decreased the rate of the decay. Kinetic analysis revealed that the effect on activation was due to a large increase in the relative proportion of the A1 component, and a decrease in τ2 (Fig. 7D). Conversely, the slower deactivation was due to a decrease in A1 and an increase in τ1.

Discussion

In this study we have made a detailed analysis of the response of VR channels to changing membrane voltage. Our results show that the VR1 current increases upon depolarization and that this increase is subsequently reversed upon repolarization. These processes follow biexponential kinetics. This agrees qualitatively with an earlier description of time- and voltage-dependent changes for VR1 expressed in HEK 293 cells (Gunthorpe et al. 2000). In addition, we describe the phenomenon at the single channel level and show that a similar modification occurs with the VR channel in sensory nerves and with endogenous activators, heat, H+, anandamide and PKC. The magnitude and kinetics of the voltage-induced responses were dependent on membrane potential, suggesting that the underlying mechanism is partly voltage dependent, and also dependent on the type of agonist, the agonist concentration and the phosphorylation state of the VR channel.

Voltage dependence

A significant finding of this study is that the magnitude of the time-induced modulation of VRs is enhanced at depolarized potentials. This effect was more pronounced with VRs activated by H+, anandamide and PDBu than with capsaicin. The relative amplitudes of the kinetic components of activation/deactivation were also strongly voltage sensitive. In the activation phase, the fraction of current carried by the fast component was barely detectable at negative potentials but increased with depolarization. Similarly, during deactivation there was a voltage-dependent increase in the fast component, and the slow component was undetectable at positive potentials. In contrast, the time constants of activation/deactivation with capsaicin did not differ significantly over a range of either negative or positive potentials, although there were differences between values at negative and positive potentials (for example, τ1 for deactivation was ≈3 and ≈12 ms at −100 and +60 mV, respectively). Gunthorpe et al. (2000) also reported voltage independence in the time constants over a range of negative or positive potentials. Taken together these data clearly indicate that the time-dependent process has a true voltage-dependent component, albeit a rather weak one, and different from that found in classical voltage-gated channels.

The rates of the voltage-induced action and deactivation processes described here for VR1 in oocytes are considerably slower than the responses seen in HEK 293 cells (≈7 and 50 ms for activation, 2 and 30 ms for deactivation) (Gunthorpe et al. 2000). The clamp settling time in oocytes of ≈2 ms is unlikely to account for this difference since most of the time constants were of substantially longer duration. We also found approximately similar rates of activation for native receptors in excised patches from DRG neurons. Piper & Docherty (1999) also reported comparatively slow rates for activation and deactivation (single exponential time constants of 520 ms at +40 mV and 271 ms at −100 mV, respectively) in DRG neurons. These data suggest that the voltage regulation of VR1 expressed in oocytes more closely matches the native system. The reasons for the differences between data obtained from oocytes and HEK 293 cells are unclear, but may depend on factors such as agonist concentration and VR phosphorylation state. We found that the overall rate of activation is greatly speeded under phosphorylating conditions, and with increasing agonist concentration. These effects are accompanied by an increase in the amplitude of the fast component and an increase in the rate of the slower component. In this regard it is significant that Gunthorpe et al. (2000) used a saturating concentration of capsaicin (30 μm) in their experiments. We typically used 500 nm capsaicin and found that with 5 μm capsaicin the slower component of activation was more than two times faster. In addition it is possible that the level of endogenous phosphorylation may be altered in HEK 293 cells after transient transfection. Thus, these differences may explain the faster kinetics at least with respect to the slower component.

Effects of agonist concentration and phosphorylation state

Our results show that the rate of the voltage- and time-dependent activation (but not deactivation) was affected by capsaicin and H+ concentration. Increasing the capsaicin concentration from 100 nm to 5 μm decreased the rise by ≈90 %. Importantly, this suggests that depolarization will act in a synergistic manner with agonists to augment VR current. This mechanism will be most pronounced with relatively weak agonists (i.e. agonists other than vanilloids), and thus seems optimized for the physiological stimulation of VRs.

PKC-mediated phosphorylation appears to play an important role in the regulation of VR channel activity. PKC activation by phorbol esters or G-protein-coupled receptor signalling induces a small level of VR current at room temperature, an effect that is enhanced with depolarization (see Fig. 5B), and also profoundly sensitizes the response of VRs to various agonists. VR1 is a substrate for PKCε, and mutagenesis of serines 502 and 800 abrogates the functional effects of PKC on VR1 (Numazaki et al. 2002). We found that PKC also dramatically alters the voltage- and time-dependent responses. Phosphorylation by PKC leads to a significantly faster rate of activation and a slower deactivation. As with the effect of increasing agonist concentration, the change in activation rate after PMA treatment was accompanied by a large increase in the proportion of the fast component and an increase in the rate of the slower component. In contrast, PKC produced a distinct effect on the deactivation kinetics, a substantial decrease in the rate of the fast component and a small increase in the proportion of the slower component. Thus, PKC enhances the voltage priming of VRs by simultaneously altering both activation and deactivation.

Mechanism of time- and voltage-dependent modulation

The mechanism of the voltage- and time-dependent modulation is unclear. The VR1 sequence does not contain a highly charged S4 helix, a common feature of voltage-gated channels. Thus, the voltage dependence must arise from relatively weak charge effects, within the VR1 channel itself or from interactions with closely associated molecules. Consistent with this idea, the rates of modulation are weakly voltage-dependent and strongly influenced by agonist concentration; at saturating capsaicin concentrations the time-dependent changes are mostly occluded. This is likely to reflect a structural rearrangement in the VR1 channels, but one cannot exclude the dissociation of a voltage-sensitive molecule. Indeed, some of the single channel properties, flickery openings and lower conductance at negative potentials, are consistent with a partial pore block (Fig. 2, and Premkumar et al. 2002). The greater single channel conductance and open probability at depolarized potentials may reflect voltage-dependent relief of block. A candidate pore blocker is phosphatidylinositol-4,5,-bisphoshate (PIP2). Chuang et al. (2001) have proposed that PIP2 tonically inhibits VR activity and that the hydrolysis of PIP2 to IP3 (inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate) by phospholipase C (during nerve growth factor or bradykinin signalling) relieves this inhibition, leading to channel activation and a dramatic enhancement of agonist-evoked responses. PIP2 is negatively charged and therefore its dissociation to the inner membrane and off the VR protein might be favoured at depolarized potentials. Similarly, phosphorylation of the VR and the added negative charge might also favour displacement of PIP2. This would be consistent with the faster current rise seen after PKC phosphorylation. Thus, these effects together with an intrinsic voltage sensitivity of VR1 may underlie the voltage- and time-dependent modification.

Physiological significance

The voltage-induced activation of VR and the resulting tail current will enhance Ca2+ entry at the resting membrane potential and may drive the membrane to threshold, promoting repetitive firing. In addition, activation of a non-specific current would lead to a broader plateau in the action potential around ≈0 mV, and this too would enhance Ca2+ entry. An important consideration is whether the voltage modulation of VR current is fast enough to be physiologically relevant. Under resting conditions (and at room temperature) the rate of activation is slow, being dominated by the slower ≈1000 ms component. However, after phosphorylation the overall rate of activation is considerably faster (mainly due to a large increase in the proportion of the fast time component of ≈16 ms). With heat (43 °C) the rate of the fast component is greater again (≈3 ms). It is significant in this regard that the AP duration in small-diameter, capsaicin-sensitive neurons is much greater (≈5-10 ms at half-amplitude) than in capsaicin-insensitive cells (Zhang et al. 1997; Abdulla & Smith, 2001). Thus, a single AP may induce maximum activation during heat and phosphorylating conditions. At lower temperature, a component of the deactivation (≈200 ms) is sufficiently slow to allow for an accumulation of activation during spiking. The spike rates of Aδ-fibres would certainly support this mechanism, and c-fibres can also discharge at greater than 20 Hz for brief periods (LaMotte et al. 1992). At higher temperatures this effect is not likely to come into play, and the greater rate of activation should predominate. It is significant that the kinetics of these voltage and time responses are modified by phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of VR by either PKC or PKA is likely to occur under inflammatory conditions (Lopshire & Nicol, 1998; Cesare et al. 1999; Khasar et al. 1999). Thus, voltage-induced modulation is also likely to be optimized under the same conditions and this synchronization suggests an important role for voltage and time modulation in pain signalling and hyperalgesia.

In summary, this study has characterized the voltage- and time-dependent properties of both native and cloned VR receptors with respect to agonist, agonist concentration and phosphorylation state. The results suggest that voltage serves as an intrinsic co-activator of VR channels.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Julius for the gift of VR1 cDNA.

References

- Abdulla FA, Smith PA. Axotomy- and autotomy-induced changes in the excitability of rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;85:630–643. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern GP, Kessler M, Premkumar LS. Voltage-dependence of the capsaicin receptor channel (VR1) Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 2000;26:39. [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Julius D. The vanilloid receptor: a molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare P, Dekker LV, Sardini A, Parker PJ, McNaughton PA. Specific involvement of PKC-epsilon in sensitization of the neuronal response to painful heat. Neuron. 1999;23:617–624. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang HH, Prescott ED, Kong H, Shields S, Jordt SE, Basbaum AI, Chao MV, Julius D. Bradykinin and nerve growth factor release the capsaicin receptor from PtdIns(4,5)P2-mediated inhibition. Nature. 2001;411:957–962. doi: 10.1038/35082088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC, Luck JC. Pulmonary afferent fibres of small diameter stimulated by capsaicin and by hyperinflation of the lungs. Journal of Physiology. 1965;179:248–262. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthorpe MJ, Harries MH, Prinjha RK, Davis JB, Randall A. Voltage- and time-dependent properties of the recombinant rat vanilloid receptor (rVR1) Journal of Physiology. 2000;525:747–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SW, Cho H, Kwak J, Lee SY, Kang CJ, Jung J, Cho S, Min KH, Suh YG, Kim D, Oh U. Direct activation of capsaicin receptors by products of lipoxygenases: Endogenous capsaicin-like substances. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2000;97:6155–6160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasar SG, Lin YH, Martin A, Dadgar J, McMahon T, Wang D, Hundle B, Aley KO, Isenberg W, McCarter G, Green PG, Hodge CW, Levine JD, Messing RO. A novel nociceptor signaling pathway revealed in protein kinase C epsilon mutant mice. Neuron. 1999;24:253–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80837-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMotte RH, Lundberg LE, Torebjork HE. Pain, hyperalgesia and activity in nociceptive C units in humans after intradermal injection of capsaicin. Journal of Physiology. 1992;48:749–764. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopshire JC, Nicol GD. The cAMP transduction cascade mediates the prostaglandin E2 enhancement of the capsaicin-elicited current in rat sensory neurons: whole-cell and single-channel studies. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:6081–6092. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06081.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg AB, Chen C, Tonegawa S, Basbaum AI. Preserved acute pain and reduced neuropathic pain in mice lacking PKCgamma. Science. 1997;278:279–283. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numazaki M, Tominaga T, Toyooka H, Tominaga M. Direct phosphorylation of capsaicin receptor VR1 by protein kinase Cepsilon and identification of two target serine residues. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh U, Hwang SW, Kim D. Capsaicin activates a nonselective cation channel in cultured neonatal rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:1659–1667. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01659.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper A, Docherty R. Capsaicin-activated currents in adult dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurones in culture exhibit time-dependent behaviour. Journal of Physiology. 1999;518.P:118P. [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar LS, Agarwal S, Steffen D. Single-channel properties of native and cloned rat vanilloid receptors. Journal of Physiology. 2002;545:107–117. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.016352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar LS, Ahern GP. Induction of vanilloid receptor channel activity by protein kinase C. Nature. 2000;408:985–990. doi: 10.1038/35050121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart D, Gunthorpe MJ, Jerman JC, Nasir S, Gray J, Muir AI, Chambers JK, Randall AD, Davis JB. The endogenous lipid anandamide is a full agonist at the human vanilloid receptor (hVR1) British Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;129:227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellani V, Mapplebeck S, Moriondo A, Davis JB, McNaughton PA. Protein kinase C activation potentiates gating of the vanilloid receptor VR1 by capsaicin, protons, heat and anandamide. Journal of Physiology. 2001;534:813–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JM, Donnelly DF, Song XJ, LaMotte RH. Axotomy increases the excitability of dorsal root ganglion cells with unmyelinated axons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;78:2790–2794. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zhou ZS, Zhao ZQ. PKC regulates capsaicin-induced currents of dorsal root ganglion neurons in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:601–608. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt PM, Petersson J, Andersson DA, Chuang H, Sorgard M, Di Marzo V, Julius D, Hogestatt ED. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]