Abstract

The β1a subunit, one of the auxiliary subunits of CaV1.1 channels, was expressed in COS-1 cells, purified by electroelution and electrodialysis techniques and identified by Western blot using monoclonal antibodies. The purified β1a subunit strongly interacted in vitro with the alpha interaction domain (AID) of CaV1.1 channels. The actions of the purified β1a subunit on CaV1.1 channel currents were assessed in whole cell voltage clamp experiments performed in vesicles derived from frog and mouse adult skeletal muscle plasma membranes. L-type inward currents were recorded in solutions containing Ba2+ (IBa). Values of peak IBa were doubled by the β1a subunit in frog and mouse muscle vesicles and the amplitude of the slow component of tail currents was greatly increased. The actions of the β1a subunit on CaV1.1 channel currents reached a steady state within 20 min. The β1a subunit had no effect on the time courses of activation or inactivation of IBa or shifted the current-voltage relation. Non-linear capacitive currents were recorded in solutions that contained mostly impermeant ions. Charge movement depended on voltage with average Boltzmann parameters: Qmax + 28.0 ± 6.6 nC μF−1, V + −58.0 ± 2.0 mV and k + 15.3 ± 1.1 mV (n = 24). In the presence of the β1a subunit, these parameters remained unchanged: Qmax + 29.8 ± 3.5 nC μF−1, V + −54.5 ± 2.2 mV and k + 16.4 ± 1.3 mV (n = 21). Overall, the work describes a novel preparation to explore in situ the role of the β1a subunit on the function of adult CaV1.1 channels.

In skeletal muscle, L-type, voltage-activated Ca2+ channels play an essential role in excitation-contraction coupling as the voltage sensors that link the depolarization of the transverse tubular system (T-system) to Ca2+ release by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (for reviews see Rios & Pizarro, 1991; Lamb, 1992; Huang, 1993; Melzer et al. 1995). In addition to their role as voltage sensors, muscle Ca2+ channels give rise to very slowly activated L-type Ca2+ currents (Sanchez & Stefani, 1983; for a review, see Melzer et al. 1995). Ca2+ channels of skeletal muscle are complex molecules composed of α1s, α2-δ, β1 and γ subunits. The α1s subunit (now referred to as the CaV1.1 channel, according to Ertel et al. 2000), is the channel-forming subunit (Perez-Reyes et al. 1989) that contains the voltage sensor of excitation-contraction coupling and the dihydropyridine binding sites (for reviews see Rios & Pizarro, 1991; Hofmann et al. 1994; Isom et al. 1994; Catterall, 2000). The β1a subunit is one of the auxiliary subunits of CaV1.1 channels (Isom et al. 1994) and the main isoform among the β1 subunits present in muscle (Ren & Hall, 1997). The β1a subunit has important effects on the surface expression of α1s but little information is available on its functional effects on CaV1.1 channels. In these experiments we describe, for the first time, the actions of β1a on the electrophysiological properties of CaV1.1 channels in adult tissue. We used spherical vesicles derived from skeletal muscle plasma membranes and the whole cell voltage clamp technique. This preparation allows the control of the composition of the internal medium, to which we added the β1a subunit. In addition, it enables proper control of the membrane potential without the complications due to the presence of the T-tubular system in muscle fibres (Camacho et al. 1999). We found that the β1a subunit produces major changes in the amplitude of L-type currents without any effect on charge movement. Part of this study has been published in abstract form (Rebolledo et al. 2002).

Methods

Preparation

We used spherical vesicles derived from the plasma membrane of frog and mouse skeletal muscle. Adult frogs were anaesthetized in 15 % ethanol prior to decapitation. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation, performed according to the authorized procedures of our institution. All procedures used conformed with the principles of the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. The procedure of vesicle formation by enzymatic treatment was originally described for single channel experiments by Standen et al. (1984), and was modified for ‘whole vesicle’ recordings by Camacho et al. (1996, 1999) to record muscle K+ and Ca2+ channel currents. In brief, semitendinosus muscles from Rana montezumae or extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles from mouse (BALB/c) were incubated in 120 mm KCl, buffered at pH 7.2 with 5 mmN-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N‘-2-ethanesulfonic acid (Hepes) with added collagenase (Sigma, type IA, 50 U ml−1). This enzymatic treatment does not produce major changes in the single channel behaviour of Na+ or K+ channels present in the vesicles (Standen et al. 1984) and collagenase, by itself, does not significantly affect the electrophysiological properties of dihydropyridine receptors in enzymatically dissociated skeletal muscle fibres (Szentesi et al. 1997). Vesicles formed spontaneously after a period of about 60 min at 20-22 °C and were selected with diameters ranging from 40 to 50 μm. Recordings were made at 15-17 °C.

Purification, expression and identification of the β1a subunit

COS-1 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were used for expression of the β1a subunit because of the high copy number achieved by SV40 origin-containing plasmids, such as the one used in the present study. Cells were routinely grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco), supplemented with 10 % heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). Six 100 mm dishes were used for tissue culture. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95 % air and 5 % CO2. The cells were transiently transfected with a plasmid (a gift from Dr Patricia Powers, University of Wisconsin, USA) containing the cDNA of the β1a subunit (pSG5-Mb1-A) under the control of the SV40 promoter. The plasmid also contained a T7-tag in the amino terminus region that was used to identify the β1a subunit by Western blot (see below). Transfections were performed with Lipofectamine Plus (Life Technologies, Inc.) according to the manufacturers’ protocol. The culture medium was changed 24 h after transfection and cells were harvested 48 h after transfection.

To isolate the β1a subunit, the cells were resuspended in lysis buffer containing (mm): 50 Tris-HCl, 2 EDTA, 2 EGTA at pH 7.4 and protease inhibitors (0.2 mm phenylmethysulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 100 nm aprotinin, 1 μm pepstatin A, 1 μm leupeptin and 1 mm soybean trypsin inhibitor). Cells were frozen in dry ice-acetone for 5 min and thawed at 37 °C for 5 min. This freeze-thaw protocol was carried out three times. The preparation was centrifuged at 10 080 g (12 000 r.p.m.) for 5 min and the pellet was recovered and homogenized in 1 vol. of 0.1 m potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and 2 vol. of 20 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1 mm EDTA, 20 % (v/v) glycerol, 0.2 % Nonidet P 40 (NP-40), 1 % sodium cholate and 0.15 M NaCl (20 strokes by hand using a Teflon-glass homogenizer as described elsewhere (Newman et al. 1992). The use of detergents allowed the separation of the β1a subunit from the membrane fraction (this is a standard procedure in those cases in which proteins are closely associated with membranes; for example, cytochrome P450, present in the endoplasmic reticulum, is efficiently isolated from membranes following a similar procedure, see Newman et al. 1992). The homogenate was centrifuged at 165 000 g (42 000 r.p.m.) for 60 min in a Type 51.1 rotor (Beckman). The pellet was discarded and the supernatant concentrated using a VIVASPIN 2 concentrator (Vivascience Inc., USA) according to the manufacturers’ protocol and the protein content was estimated by Lowry's method (Lowry et al. 1951).

To identify the β1a subunit, samples from the concentrate were diluted with an equal volume of 2 × sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (containing: 50 mm TrisHCl, pH 6.8, 4 % SDS, 20 % β-mercaptoethanol, 0.04 % bromophenol blue) before loading onto 10 % polyacrylamide gels. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue. The electrophoretic pattern was compared between samples from transfected and non-transfected cells and the β1a subunit was identified by its molecular mass. The identification of the β1a subunit was further confirmed by Western blot from the concentrate. Immunoblots were done following standard procedures (Lane, 1990). Protein (100 μg) was electrophoresed in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (10 % polyacrylamide) and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The blots were blocked with 5 % non-fat dried milk in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). A monoclonal antibody directed at the T7-tag (MASMTGGQQMG) amino acids (Novagen Inc., USA) was used to identify the β1a subunit. Alternatively, an antibody that recognizes the skeletal muscle DHPR β subunit as a 52 kDa band on Western blots (Upstate Inc., USA) was also used. Both were used at a 1:1000 dilution. After washing, the membrane was incubated with a rabbit anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Amersham Life Sciences, USA) as secondary antibody.

Once the identity of the β1a subunit was assessed, the corresponding band in the gels stained with Coomassie blue was cut out and purified by electroelution methods, according to Smith (1992). After the electroelution procedure, SDS was removed by electrodialysis with a buffer solution with a low SDS content (0.01 m NH4CO3, 0.02 % SDS) for 24 h. During this period the solution was exchanged several times. To further remove all traces of SDS, proteins were precipitated overnight after electrodialysis with acetone (80 %, HPLC grade) at −20 °C. The precipitate was then centrifuged at 10 080 g (12 000 r.p.m.) for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was removed. The pellet was gently washed with 100 % acetone, centrifuged again and dried under vacuum to remove the solvent. The dried protein was stored at −20 °C until used. Although we do not have the precise yield numbers, we roughly estimate that about 60 % of the β1a subunit present in the COS-1 cells could be recovered after the purification procedure. Silver staining in a polyacrylamide gel following the method described in detail by Sasse & Gallagher (1992) was done to assess whether a single or multiple bands were present after the purification procedure.

Probing the interaction of the purified β1a subunit with α1s

The fusion protein glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-AIDα1s was used to probe the integrity of purified β1a subunit. To this end, the nucleotide fragment 1251-1401 of rabbit α1s cDNA was amplified by PCR. This fragment codes the 342-392 amino acid region that contains the interaction site with the β subunit (AID) (Pragnell et al. 1994). The primers used were:

and

The amplified fragment was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and cloned into the pGEX2T vector (Pharmacia). The resulting clones were sequenced (ABI PRISM Model 310, Perkin Elmer, USA) prior to being used to transform BL21 (DE3) bacteria (Novagen, Inc., USA). A 5 ml sample of the overnight culture was added to 50 ml medium. The culture was grown until it reached an OD value of 0.6 at 600 nm and then induced with 1.5 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 4 h. The culture was centrifuged and resuspended in 5 ml NETN buffer, containing (mm): 100 NaCl, 20 Tris-HCl, 1 EDTA, 1 PMSF and 0.5 % NP-40 at pH 8.0. It was then sonicated three times for 30 s each and centrifuged at 10 080 g (12 000 r.p.m.) for 10 min. Both GST and GST-AIDα1s remained in the soluble fraction. An aliquot (500 μl) of this solution was incubated with 100 μl of Glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Pharmacia) in NETN plus 0.5 % non-fat dried milk at a temperature of 4 °C for 2 h. The sample was washed three times with NETN and resuspended in an equal volume of NETN buffer with 1 mm of the protease inhibitor PMSF and 0.02 % NaN3 added. The purification of GST and GST-AIDα1s was carried out using a high-affinity resin and checked with a polyacrylamide gel and Coomassie blue. Identical amounts of GST and GST-AIDα1s, coupled to Glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads were equilibrated in 200 μl of binding buffer containing (mm): 50 Tris-HCl, 100 NaCl, 0.1 DTT at pH 7.4. Purified β1a subunit (5 μl) was added separately to GST and GST-AIDα1s proteins and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h under continuous agitation. Then, the samples were washed five times with a buffer similar to the binding buffer, except that it contained 150 mmNaCl, and the interaction of β1a subunit with GST and GST-AIDα1s proteins was assessed on SDS-PAGE gels and Western blots using the anti-T7-tag monoclonal antibody.

Solutions

The external solution employed to record Ba2+ currents contained (mm): 30 Ba2+, 110 TEA+ and methanesulphonate (CH3SO3−) as anion. The composition of the external solution used to record charge movement was (mm): 110 TEA-CH3SO3, 10 CaCl2. In the experiments involving the Ca2+ channel agonist Bay K 8644 (Ma & Coronado, 1988) a concentration of 1 μm was used. The pipette solution contained (mm): 125 CsCH3SO3, 2 MgCl2 and 1 EGTA. The presence of Ca2+ in the extracellular solution in charge movement experiments was required to maintain the stability of our recordings. Movements of ‘on’ charge due to non-linear capacitive currents are properly recorded with these saline solutions because, as we have shown previously (Camacho et al. 1999), charge moves at potentials more negative than L-type currents. Furthermore, movement of ‘on’ charge ends within 10 ms after the onset of the depolarizing pulse, during which no significant activation of ionic currents takes place. Finally, the current density values of L-type currents recorded under these conditions are quite small. In fact, currents only became visible as an apparent increase in ‘off’ charge relative to ‘on’ charge at potentials more positive than - 30 mV when this [Ca2+]O was used (Camacho et al. 1999). Inward currents were clearly seen during depolarizing pulses when the more permeant Ba2+ ions, at a higher concentration, were used as charge carriers (Camacho et al. 1999 and this paper).

Extra- and intracellular solutions were buffered with Hepes (5 mm) at pH 7.2 and 7.1, respectively. All chemicals were obtained from either the Sigma Chemical Co. or the Aldrich Chemical Co., USA.

Electrophysiological methods

We followed the recording techniques described in detail by Camacho et al. (1996, 1999). In brief, the patch clamp technique was used in the whole cell configuration (Hamill et al. 1981). Pipettes were double-pulled from hard glass (KIMAX-51; Kimble Glass, Toledo, OH, USA) using a David Kopf (Tujunga, CA, USA) 700D vertical puller. The tips had resistances of about 2-3 MΩ.

To test the actions of the β1a subunit on CaV1.1 channel currents, we first recorded control currents from a preselected muscle vesicle with a pipette that contained the internal solution. Then this pipette was replaced by one filled with 5 μl of the same solution to which the β1a subunit was added at a concentration of 0.30-0.35 μg μl−1. Finally, the currents were again recorded from the same vesicle with a similar pulse protocol. Control experiments were done following this experimental protocol, except that a protease-pretreated β1a subunit was used. In these experiments, 50 μl of the internal solution that contained the β1a subunit were mixed with proteinase K (Merck, Germany), an enzyme with a high protease activity (≥ 40 U ml−1). The protease-treated β1a subunit was retrieved following the manufacturers’ protocol. Other control experiments involved the use of a second pipette filled with the internal solution with no β1a subunit added.

The diffusion of the β1a subunit through the pipette was estimated in separate experiments in vesicles with similar diameters, ranging from 40 to 50 μm, by measuring the diffusion of fluorescein isothiocyanate labelled-peroxidase (FITC-peroxidase, Sigma), which has a similar molecular mass to that of the β1a subunit. In addition to vesicle size, diffusion also depends on the access resistance (Pusch & Neher, 1988), therefore we used pipettes with similar access resistances to the ones used in electrophysiological experiments. Vesicles were patch clamped with pipettes containing 5 μl of FITC-peroxidase at a similar concentration to that used when the β1a subunit was tested and were illuminated with monochromatic light at a wavelength of 485 nm. Diffusion was measured as the increase in fluorescence emitted by the vesicles at a wavelength of 535 nm. To measure fluorescence, vesicles were photographed with film (Delta 3200, Ilford, UK) at different times after the formation of the seal and the emitted fluorescence was estimated as the density change under the image of the vesicle on film.

Data collection and pulse protocol

Membrane currents (Im) in response to voltage step depolarizations applied from the holding potential (Eh), were measured with an Axopatch amplifier (Model 200A, Axon Instruments, USA) and sampled by an IBM-PC/AT compatible Pentium-based microcomputer. Analog signals were digitized to a resolution of 12 bits through a LabMaster interface (TL-1 DMA interface, Axon Instruments) that also generated the command pulses. Data were analysed with a combination of pCLAMP (version 6.0, Axon Instruments) and in-house software. Im was amplified and filtered with an active four-pole, low-pass Bessel filter set at a corner frequency of no more than half the sampling frequency. To measure activation of Ba2+ currents, command pulses of 500 ms duration and variable amplitude were delivered. The interval between pulses was at least 1 s to avoid changes in channel kinetics by a previous depolarization, as described by Feldmeyer et al. (1990). The pulse sequence was bracketed by five consecutive hyperpolarizing control pulses, −20 mV from Eh that ranged between −80 and −100 mV. The currents generated during the hyperpolarizing pulses were used to calculate the linear membrane capacitance and to measure the leakage current during the experiment.

In double-pulse experiments, done to record the kinetic changes produced by a conditioning depolarization, two consecutive 500 ms depolarizing pulses to +20 mV were delivered. The interval between pulses was 100 ms, during which the membrane potential was clamped to the holding potential (-80 mV).

Facilitation experiments were done with the following pulse protocol: first, a control pulse to +10 mV was applied, then a 2 min pause was allowed for complete recovery from inactivation, after which a conditioning pulse to +60 mV was delivered. This was followed by a brief repolarization pulse to the holding potential of −90 mV, and then by a test pulse to +10 mV.

Steady-state inactivation was investigated by delivering 4000 ms prepulses to several potentials followed by 500 ms test pulses to +20 mV. The voltage dependence of inactivation of L-type currents was fitted to a function of the same form as eqn (1) but with (Vm - V) in the exponential (see below).

Charge movement was measured in polarized vesicles by delivering 100 ms pulses to preselected depolarizing potentials. We measured the area under the unsubtracted currents at the beginning of the depolarizing pulses. Camacho et al. (1999) described that the total charge is mostly linear for hyperpolarizing pulses, whereas depolarizing pulses generate an excess charge that is due to non-linear capacitive currents. Therefore, a straight line was fitted to charge moved by ‘on’ currents elicited by pulses from −180 to −110 mV from the holding potential of −100 mV. The line was extrapolated to depolarizing values to calculate the non-linear charge moved at each potential. The voltage dependence of activation of non-linear charge movement was fitted to the Boltzmann function:

| (1) |

where Qmax is the maximum value of charge, Vm is the membrane potential, V is the potential where Q + 0.5Qmax, and k is a measure of the steepness of the curve.

Unless otherwise indicated, the dialysis time for data presented with the β1a subunit was 15 min.

The fitting of numerical formulae to experimental data employed a non-linear least squares algorithm. Parameter values given in the text and in the table are expressed as means ± s.e.m. To calculate statistical significance, Student's t test was used at the level P < 0.05.

Results

Transiently transfected COS-1 cells express the β1a subunit

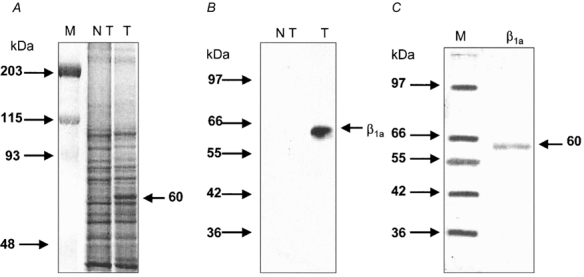

We found that the β1a subunit can be expressed in the membrane fraction of COS-1 cells using the mammalian expression vector pSG5-Mb1-A. Figure 1A illustrates a representative polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie blue that shows a distinct band of about 60 kDa. The band was present in transfected cells only. This is consistent with the reported molecular mass of 56 kDa of the β subunit of skeletal muscle (Flockerzi et al. 1986), since a slightly higher molecular mass is expected due to the presence of T7-tag amino acids. Two different antibodies, both specific for the muscle β subunit, were used to visualize the expressed protein on immunoblots. The β1a subunit was detected as a single molecular species of about 60 kDa. Figure 1B shows a representative immunoblot that illustrates the reactivity of the protein with the antibody directed at the tag amino acids in the N-terminus. Similar results were observed with the antibody directed at the β1a subunit (data not shown), thus providing further evidence that the expressed β1a subunit is an intact full length protein. Figure 1C shows a silver-stained polyacrylamide gel. Silver staining of purified β1a subunit from COS-1 cells revealed a single and distinct band with an approximate molecular mass of 60 kDa. No other bands were detected after the purification procedure with this sensitive staining method, suggesting that the purification procedure yielded an essentially free β1a subunit without contamination from other proteins. Although unlikely, the presence in the gel, in addition to the β1a subunit, of a different protein with exactly the same molecular mass cannot be entirely ruled out.

Figure 1. Identification and purification of the β1a subunit expressed in COS-1 cells.

A, Coomassie blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide (10 %) gel of concentrate prepared from non-transfected (NT) and transfected (T) cells. The arrow indicates a protein with an apparent molecular mass of 60 kDa. Notice that this band is only expressed in transfected cells. B, an immunoblot from gel-separated concentrate prepared from non-transfected (NT) and transfected (T) cells. A monoclonal antibody directed at the T7-tag was used. Notice that the antibody recognizes a band in transfected cells only. C, a silver-stained polyacrylamide gel showing the β1a subunit, purified as indicated in Methods. Markers (M) were used in panels A and C. The molecular masses of the markers (kDa) are given on the left side of each panel.

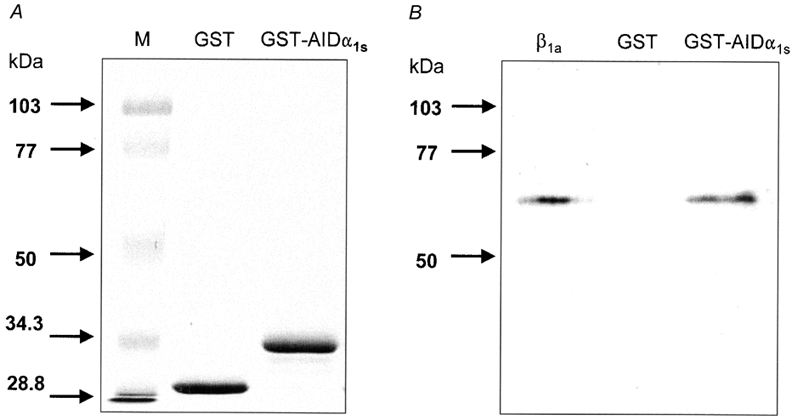

Before testing the actions of the β1a subunit on CaV1.1 channel currents, it was important to determine whether the integrity of the β1a subunit was preserved after the purification procedure. If this was indeed the case, it would be expected that the high interaction capability of the β1a subunit with α1s would have been maintained. Therefore, we examined in vitro the interaction of purified β1a subunit with the conserved motif present on all α1 subunits and essential for the binding of β subunits (AID). AID was expressed as a 50-amino-acid GST fusion protein. The GST-AID fusion protein was coupled to glutathione- Sepharose beads and used as the substrate for the binding of purified β1a subunit (see Methods). Figure 2A shows a representative polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie blue that shows a distinct band of about 26 kDa that corresponds to GST. The band that migrated more slowly was associated with GST-AID, as expected, and it corresponded to a molecular mass of 32 kDa. Figure 2B shows a representative immunoblot that illustrates binding of GST-AID protein with purified β1a subunit. The β1a subunit reacted with the antibody directed at the T7-tag amino acids in the N-terminus, consistent with the membrane extract immunoblot shown previously (Fig. 1B). GST alone did not bind any β subunits (Fig. 2B, central lane). Finally, GST-AID Sepharose beads were able to bind purified β1a subunit, indicating that this specific form of interaction was preserved.

Figure 2. AIDα1s and β1a interactions.

A, Coomassie blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel containing 10 μl GST-Sepharose beads (GST) or GST-AIDα1s fusion protein-Sepharose beads. B, immunoblots probed with a monoclonal antibody directed at the T7-tag of the β1a subunit. GST and GST-AIDα1s fusion protein were allowed to interact in vitro with purified β1a subunit prior to immunoblots. Markers (M) were used in panel A. The molecular masses (kDa) of the markers are given on the left side of the panel.

Actions of β1a on L-type currents in vesicles

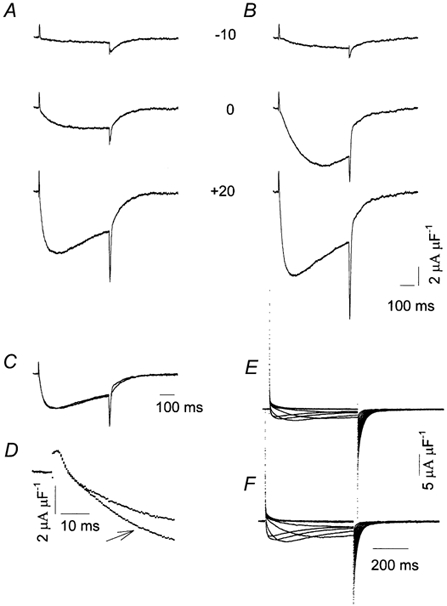

We found that the β1a subunit increased the amplitude of currents flowing through CaV1.1 channels. This is shown in the experiments illustrated in Fig. 3A-F. Figure 3A illustrates control membrane currents recorded from a frog muscle vesicle to the potentials indicated (in mV). Inward Ba2+ currents, the amplitude and time course of which depended upon the membrane depolarization level during the pulse, were recorded. Currents were not sustained but declined during the pulse by a voltage-dependent inactivation process. These currents closely resembled those we described previously as L-type, dihydropyridine-sensitive currents (Camacho et al. 1999). Figure 3B illustrates currents recorded from the same vesicle, 15 min after the pipette containing the control solution was replaced by one containing the β1a subunit. The amplitude of the currents was distinctly larger at all potentials (for example, during the pulse to +20 mV) though their time course was similar. To illustrate the fact that the β1a subunit does not produce major kinetic effects, the currents recorded at +20 mV, illustrated in Fig. 3A and B, were normalized relative to their peak amplitude during the pulse. Figure 3C shows superimposed records of the currents after the normalization procedure. It is clear that the time course of activation and inactivation of both currents was quite similar, indicating no major effects of β1a subunit on channel kinetics. This conclusion was further supported by results obtained with double-pulse experiments of the type described by Feldmeyer et al. (1990) in frog muscle fibres. We found in frog muscle vesicles that the current during a 500 ms test pulse to +20 mV activated faster when compared to the current during the conditioning pulse. The time to peak of IBa during the conditioning pulse averaged 130.8 ± 3.8 ms (n = 5) and it decreased to 98.0 ± 6.4 ms (n = 5) during the test pulse, confirming the observations of Feldmeyer et al. (1990). In the presence of the β1a subunit, the time to peak of IBa during the prepulse was 124.8 ± 6.4 ms (n = 6) and it decreased to 91.7 ± 3.4 ms (n = 6) during the test pulse. These numbers were similar to those obtained under control conditions, further confirming that the β1a subunit has negligible effects on Ca2+ channel current kinetics.

Figure 3. Macroscopic Ba2+ currents in membrane vesicles.

A, currents during voltage steps to the potentials indicated (mV) after subtraction of linear membrane current components. Eh + −80 mV. B, the effect of the β1a subunit on membrane currents recorded in the same experiment as in A. C, superimposed recordings at +20 mV from A and B; recordings were normalized to their peak amplitude. D, superimposed recordings at +20 mV from A and B. Note that recordings are shown on an expanded time scale. The arrow indicates the recording taken in the presence of the β1a subunit. E, superimposed leak-subtracted recordings from a separate experiment taken from a mouse muscle vesicle. Currents were elicited by stepping the membrane potential from −60 mV to +40 mV in 10 mV steps from Eh + −80 mV. F, same experiment as in E, in the presence of the β1a subunit.

The β1a subunit also increased the magnitude of Ca2+ channel currents in vesicles derived from mouse skeletal muscle. Figure 3E shows superimposed membrane current records under control conditions from a mammalian muscle vesicle and Fig. 3F shows the corresponding records, taken 20 min after the control pipette was replaced by one containing the β1a subunit in the same experiment. The β1a subunit increased the amplitude of mammalian L-type currents with minor changes in their time course.

Unlike the effects of β1a on Ba2+ current amplitude, charge movement remained unchanged by the addition of the β1a subunit. Charge movement can be seen in the experiment illustrated in Fig. 3A and B as brief outward deflections at the beginning of the pulses that represented non-linear outward capacitive currents or ‘on’ currents (Camacho et al. 1999). These currents preceded the inward Ba2+ currents. Immediately after the pulses, large inward non-linear currents were also recorded. As we previously described in detail (Camacho et al. 1999), two distinct components contributed to these currents: tail inward Ba2+ currents, arising from deactivation of the channels and non-linear capacitive currents. To determine whether the β1a subunit altered charge movement, we compared the time course and amplitude of ‘on’ currents before and after the application of the β1a subunit. Figure 3D illustrates superimposed traces of the membrane currents generated by a command pulse to +20 mV, from the same experiment illustrated in Fig. 3A and B but displayed on a much faster time scale. It is apparent that, while the amplitude of the inward Ba2+ current became larger when the β1a subunit was present in the patch pipette, as shown in Fig. 3A and B, ‘on’ currents were identical, indicating that this subunit had negligible effects on charge movement. This observation was confirmed by performing charge movement experiments in solutions containing mostly impermeant ions. We found that the average values of the Boltzmann parameters fitted to the experimental data were unaffected by the β1a subunit. Table 1 summarizes results from several experiments under control conditions and in the presence of the β1a subunit. In the latter case, data correspond to recordings taken 15 min after the whole cell configuration with the test pipette was achieved.

Table 1.

Actions of the β1a subnit on charge movement in vesicles

| Control* | β1a** | |

|---|---|---|

| Qmax(nC μF−1) | 28.0 ± 6.6 | 29.8 ± 3.5 |

| V (mV) | −58.0 ± 2.0 | −54.5 ± 2.2 |

| k (mV) | 15.3 ± 1.1 | 16.1 ± 1.3 |

n = 24

n = 21.

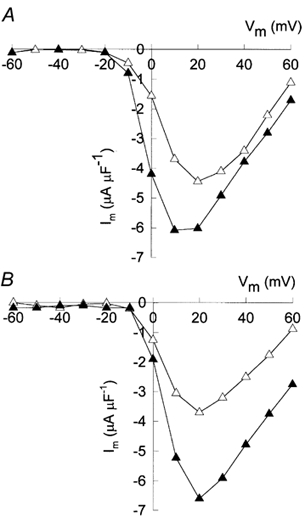

Figure 4A and B shows the current-voltage relation from the experiments illustrated in Fig. 3A-D and Fig. 3E-F, respectively. Open symbols represent values of peak currents recorded with a control solution and filled symbols, results with the β1a subunit added. In the control solution, activation of both frog (Fig. 4A) and mouse (Fig. 4B) muscle Ba2+ currents began at about −10 mV; the peak Ba2+ current was largest at a membrane potential of +20 mV; it declined for larger depolarizations and it was still inward at +60 mV, indicating a very positive reversal potential. Compared to records taken in control conditions, the current-voltage relation in the presence of the β1a subunit, both in frog and mouse muscle vesicles, was similar except for the larger values of peak currents recorded at all potentials, but no major shifts along the voltage axis were observed. To measure possible shifts, the voltage which produced the largest current was determined, as this approach produced the most consistent results. In nine experiments performed in frog muscle vesicles, IBa peaked at +13.3 ± 2.0 mV. Similarly, it peaked at +11.1 ± 2.6 mV when the β1a subunit was present in the patch pipette. In the same experiments, the value of peak IBa averaged −3.1 ± 0.4 μA μF−1 under control conditions and it increased to −5.6 ± 0.3 μA μF−1 in the presence of the β1a subunit. The ratio between peak IBa in the presence of the β1a subunit relative to its value under control conditions averaged 2.0 ± 0.3 (n = 9). In contrast, the protease-inactivated β1a subunit had no effect. The corresponding ratio of peak currents was: 1.05 ± 0.03 (n = 9). The β1a subunit also increased the amplitude of L-type currents in the presence of Bay K 8644 (1 μm), although the effects were less pronounced. In three experiments, peak IBa averaged −4.2 ± 0.2 μA μF−1 (n = 3) under control conditions and −7.1 ± 0.3 μA μF−1 (n = 3) in the presence of the β1a subunit. Similarly, the corresponding ratio of peak currents was: 1.6 ± 0.2 (n = 3). Since Bay K increases the open probability of the channels (Ma & Coronado, 1988), this finding is consistent with the possibility that the β1a subunit also increases their open probability.

Figure 4. The action of the β1a subunit on the current-voltage relation.

A, peak current values taken from the experiment illustrated in Fig. 3A (▵) and B (▴). B, the corresponding peak values from the experiment illustrated in Fig. 3E (▵) and F (▴).

In agreement with the results obtained in frog muscle vesicles, the β1a subunit greatly increased the peak current amplitude of mammalian muscle vesicles in Bay K-untreated preparations. In three experiments, peak IBa averaged −2.2 ± 0.1 μA μF−1 (n = 3) under control conditions and −4.6 ± 0.1 μA μF−1 (n = 3) in the presence of the β1a subunit. The mean value of the ratio between peak current amplitude values was: 2.2 ± 0.1 (n = 3). These results indicate that the β1a subunit doubles the amplitude of L-type currents flowing through CaV1.1 channels.

L-type currents are not sustained but decline during the depolarizing pulses by a voltage-dependent inactivation process. Double-pulse experiments were performed to assess the effect of the β1a subunit on steady state inactivation. We found that the main effect of the β1a subunit is a shift in the mid point of inactivation towards more negative potentials. In control experiments, the average Boltzmann parameters were (mV): Vm + −37.6 ± 3.2 (n = 4) and k + 9.1 ± 0.6 (n = 4). In the same experiments, the addition of the β1a subunit changed these parameters to: Vm + −53.4 ± 2.2 (n = 4) and k + 16.3 ± 2.2 (n = 4).

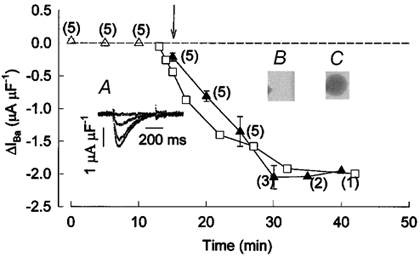

Time course of β1a action on L-type currents

To measure the time course of the effect of the β1a subunit on CaV1.1 channel current amplitude, the membrane potential of frog muscle vesicles was pulsed to +20 mV from the Eh + −80 mV at 5 min intervals, under control conditions and after the control pipette was replaced by one containing the β1a subunit. Control currents were averaged and each individual current record, under control conditions and in the presence of the β1a subunit, was subtracted from this average current in every experiment. This procedure provided an estimate of the increase in current amplitude by β1a subunit. Figure 5 summarizes results from several experiments; the plot shows mean values of the difference in peak current as a function of time. As expected, the subtracted currents under control conditions were very close to zero, indicating only minor changes in current amplitude (▵). However, when the control pipette was replaced by one containing the β1a subunit (indicated by the arrow), the amplitude of the subtracted current progressively increased until it reached a steady value 15 min after the ‘whole cell’ configuration with the test pipette was achieved (▴). Inset A shows traces from a representative experiment. To determine whether the time course of action of the β1a subunit could be accounted for by its diffusion through the tip of the pipette, we measured the increase in fluorescence emitted by vesicles containing FITC-peroxidase and found that it followed a quite similar time course, as indicated by a representative experiment in Fig. 5 (□). Inset B shows a photo image from the same experiment taken just before the formation of the gigaseal. The tip of the patch pipette can be seen on the left hand side. Inset C shows an image from the same experiment taken 29 min after the whole cell configuration was achieved. The increase in the fluorescence of the vesicle is apparent. By comparing the density of the pipette tip to that of the vesicle in two separate experiments, we estimated that at 20 min, the concentration of FITC-peroxidase was 0.65 times that of the pipette tip. A similar conclusion was reached when the kinetic equations of diffusional exchange between small cells and a patch pipette were used (Pusch & Neher, 1988). Thus, for a vesicle with a 20 μm radius, we calculated that under experimental conditions, diffusion reached 68 % of its final value at a dialysis time of 20 min. This indicated that the concentration of the β1a subunit inside the vesicles reached a value of 0.4 μg μl−1 or 5 nm in our electrophysiological experiments. Based on this estimate, we calculated that 2 × 1015 β molecules per ml were present inside the vesicles. For a vesicle with a 20 μm radius, we estimated that about 66 000 β molecules were added.

Figure 5. The time course of action of the β1a subunit.

Triangles represent peak ΔIBa values (IBa,i - IBa,a, where i is every individual current recording and a is the average of the currents recorded under control conditions in every experiment) as a function of time. Currents were recorded at +20 mV. ▵, the average values under control conditions (n = 5). ▴, the average values in the presence of the β1a subunit. Numbers beside each point indicate the number of experiments. The arrow indicates the beginning of the recordings with the pipette containing the β1a subunit. Inset A, ΔIBa recordings from a representative experiment taken at 0, 5, 10 and 15 min after breaking the patch membrane with a pipette containing the β1a subunit. Inset B, photograph taken of a vesicle previous to the recording with a patch pipette that contained FITC-peroxidase. Inset C, the same vesicle 29 min after the initiation of the ‘whole-cell’ recording. □, values of optical density (in arbitrary units) from the experiment shown in B and C.

Tail Ba2+ currents and facilitation in vesicles

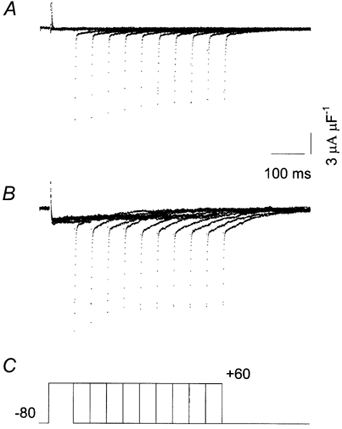

Excessive tail currents and facilitation of Ca2+ channels of mammalian myotubes have previously been described (Fleig & Penner, 1996). Excessive tail currents, albeit quite small, were also recorded in frog muscle vesicles as an increase in the amplitude of the tail currents generated after pulses of increasing duration (Camacho et al. 1999). Figure 6A shows membrane currents produced by the pulse protocol shown in panel C. Membrane currents were elicited by depolarizing pulses to +60 mV, the duration of which was progressively increased. There was a small and brief outward current at the beginning of each pulse that was similar to the ones illustrated in Fig. 3A and B. These currents were followed by a small inward Ba2+ current that inactivated, in part, during the pulses. Immediately after the depolarizing steps two distinct tail current components were observed: a fast component and a slow one, the magnitude of which increased as the pulse duration increased, confirming previous results (Camacho et al. 1999). Panel B illustrates the currents from the same experiment after the control pipette was replaced by one containing the β1a subunit. Currents were recorded from the same vesicle with a similar pulse protocol as in Fig. 6A. There was a distinct increase in the amplitude of the inward current during the pulse, consistent with the results described in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4. In addition, the amplitude of the slow tail current component was greatly increased by the β1a subunit.

Figure 6. The influence of the β1a subunit on tail currents.

A, recordings showing non-linear control currents generated with the pulse protocol shown in C. B, currents recorded with the same pulse protocol in the presence of the β1a subunit. Pulse durations were (ms): 75, 125, 175, 225, 275, 325, 375, 425, 475 and 525. Same experiment throughout.

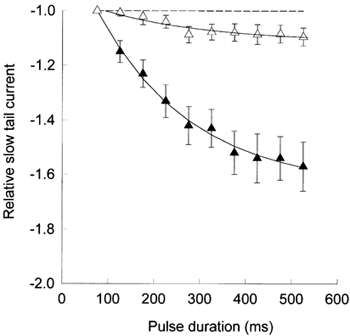

Figure 7 summarizes results from several experiments. The magnitude of the slow component, measured as the amplitude of the tail current 13 ms after the end of each depolarizing pulse, was normalized relative to its value after the 75 ms pulse, the shortest pulse duration tested. In control experiments (▵), the magnitude of the slow component was quite small, reaching an asymptotic value of about 1.1. In contrast, it increased up to 1.6 in the presence of the β1a subunit (▴).

Figure 7. The action of the β1a subunit on the slow component of tail currents.

The peak amplitude of ‘off’ currents (ordinate), relative to its value after a 75 ms pulse, as a function of pulse duration (abscissa). ▵, average values (± s.e.m., n = 31) under control conditions. ▴, average values (± s.e.m., n = 19) in the presence of the β1a subunit. The continuous lines represent the single exponential best fit, with τ= 228 ms (▵) and τ= 206 ms (▴).

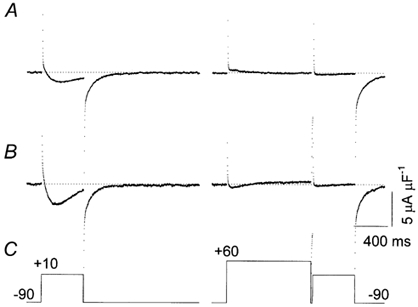

Facilitation has been observed in mammalian myotubes as an increase in current amplitude during test pulses that were preceded by a conditioning depolarization and it has been proposed that excessive tail currents and facilitation have the same origin (Fleig & Penner, 1996). It was, therefore, relevant to test whether facilitation was present in the vesicles and whether the β1a subunit had an influence on it. Figure 8 shows results from a representative facilitation experiment. The membrane potential was clamped according to the pulse protocol shown in panel C. In the absence of the β1a subunit (Fig. 8A), the control pulse produced an inward current that inactivated almost completely during the pulse. In contrast, the current during the test pulse was virtually absent, indicating that the conditioning prepulse produced a protracted inactivation state. In the presence of the β1a subunit (Fig. 8B), the amplitude of the L-type current during the control pulse increased, as shown previously (Figs 3–5), but the amplitude of the current during the test pulse was quite small, suggesting that the channels were similarly inactivated by the conditioning depolarization. Similar results were obtained in another four experiments.

Figure 8. L-type currents after a conditioning depolarization.

A, leak-subtracted control currents recorded with the pulse protocol shown in C. B, currents recorded with the same pulse protocol in the presence of the β1a subunit. Data were taken from the same experiment. The dotted lines in A and B represent the zero current level. C, the pulse protocol; the pulse to +10 mV is the test pulse. The pulse to +60 mV is a conditioning prepulse preceding the test pulse.

Discussion

A new role of the β subunit in muscle

We here describe for the first time that the auxiliary β1a subunit modulates the activity of pre-existing α1s channels of adult skeletal muscle. Modulation was seen as a rapid increase in the magnitude of L-type currents. Although the underlying mechanism of this form of regulation remains to be established, our present results suggest a direct action of the β1a subunit on α1s without involving an increase in the number of α1s molecules present in the membrane. Several lines of evidence provide support for this conclusion: firstly, we tested the effects of the β1a subunit itself on channel activity in muscle vesicles, a system devoid of internal organelles (Camacho et al. 1996) and, therefore, without all the machinery that is required for the synthesis and transport of channels to the membrane. Secondly, addition of the β1a subunit to the vesicle did not increase charge movement, as would be expected if more α1s molecules were incorporated into the membrane. Thirdly, the actions of the β1a subunit on α1s currents developed as soon as it diffused through the patch pipette, suggesting a modulatory effect of this subunit on preexisting channels. Finally, our results show that the purified β1a subunit strongly bound in vitro to the AID region of the α1s subunit.

A direct effect of β subunits on Ca2+ channel function has been difficult to establish in the past because in many cases the actions of β subunits also involve changes on trafficking of channels (Kamp et al. 1996; Josephson & Varadi, 1996; Wei et al. 2000). According to Gerster et al. (1999), these may be independent functions of the β subunit. In one example, however, functional modifications of the cardiac Ca2+ channel currents by β subunits, without changes in the number of channels, have been observed. When α1c was coexpressed in Xenopus oocytes with the cardiac β2a subunit, an increase in the magnitude of Ca2+ channel currents without changes in charge movement was observed (Neely et al. 1993), consistent with the present results in skeletal muscle. However, a significant difference between modulation of the skeletal muscle and the cardiac Ca2+ channel by their β subunits is apparent. Unlike the shift produced by β2a on α1c activation parameters (Neely et al. 1993), we observed no shifts in the current-voltage relation of skeletal muscle Ca2+ channels by the β1a subunit. This suggests that, unlike the effects of the β2a subunit on the cardiac channel, the coupling between charge and the opening of the channel pore remains unchanged when the β1a subunit interacts with the skeletal muscle CaV1.1 channel.

The dual role of the β subunit in muscle

We found no major effects of the β1a subunit on the time course of activation or inactivation of L-type currents. Early expression experiments on mammalian cell lines had shown acceleration of channel kinetics by coexpression of α1s and β1a subunits (Lacerda et al. 1991; Varadi et al. 1991). Differences in the phosphorylation level of the β1a subunit, which contains several potential phosphorylation sites (Catterall, 2000), might help to explain the discrepancies between these results and ours. However, channel kinetics in heterologous systems were abnormally slow when α1s was expressed alone. Therefore, it is possible that CaV1.1 channels are not assembled or regulated properly in cell lines, which may explain the differences from the present findings.

Previous work has shown that the β1a subunit has profound effects on the surface expression levels of the α1s subunit. Coexpression of both α1s and β1 subunits resulted in an increase in the number of dihydropyridine binding sites (Lacerda et al. 1991; Varadi et al. 1991) and in an increased amount of α1 in the membrane (Krizanova et al. 1995). In agreement with a role for the β1 subunit in the surface expression of Ca2+ channels, Gregg et al. (1996) have shown that the β1s subunit is absent in the membrane of β-null, cultured myotubes (Gregg et al. 1996). Likewise, Beurg et al. (1997, 1999) reported an increase in charge movement by expression of β1a in β-null myotubes. These results can be easily reconciled with our present findings if the β1a subunit has a dual effect on α1s channels, on the one hand, targeting α1s to the tubular membrane and, on the other, modulating channel function of pre-existing channels (this paper). In this regard, it is interesting to note that Witcher et al. (1995) described a pool of β subunits in skeletal muscle that is not tightly associated with α1 subunits and proposed that they may be shuttled to the membrane to bind with α1 subunits and modulate channel function. The suggestion that the β3 subunit directly modulates human α1c currents recorded is also consistent with our view (Yamaguchi et al. 1998). Thus, in oocytes pretreated with the V-ATPase inhibitor Bafilomycin A1, no increase in the levels of α1c were present and yet a 1.8-fold increase in current amplitude was observed, which was interpreted as an allosteric modulation of α1c subunits by β3 subunits (Yamaguchi et al. 1998).

Low-affinity α1s and β1a interactions

Among other possibilities, direct α1s-β1a interactions may play a role in the modulatory action of the β1a subunit on channel function described in the present paper. If indeed these interactions take place, our data do not provide evidence as to whether this occurs by binding to high- or to low-affinity sites on the α1s subunit. High-affinity interaction sites in the α (AID) and in β (BID) subunits of Ca2+ channels have been described (Pragnell et al. 1994; Walker & De Waard, 1998). AID is a highly conserved region in the loop between domains I and II (Pragnell et al. 1994). BID is a 30-amino-acid N-terminal region of the second conserved domain of the β subunit (De Waard et al. 1994). The BID region of β1a binds strongly to the I-II loop of α1s (Cheng et al. 2002). In addition to these high-affinity regions, low-affinity sites have been recently described (Cheng et al. 2002) and perhaps they interact with the pool of non-bound β1a subunits described by Witcher et al. (1995). This would imply that more than one β1a subunit could bind to a single α1s subunit. The association of multiple subunits with a single α1 subunit has been proposed, based on experiments in which α1c and α1E were expressed in Xenopus oocytes, and a new interaction domain in α1E was described (Tareilus et al. 1997). Alternatively, it is possible that at least some α1s subunits are not associated with β subunits. This is because a significant fraction of all dihydropyridine binding sites (and therefore α1s subunits) in muscle are not functional channels (Lamb, 1992; Schwartz et al. 1985). If the reason why some α1s subunits are not functional is because of the lack of bound β1a subunits, then our data may be explained by binding of β1a subunits to these α1s subunits. The presence of unoccupied channels would be expected if α1s-β1a interactions are reversible. Recently, the main interactions between α1c and β subunits have been shown to be reversible in vitro (Bichet et al. 2000) and in inside-out patches of membranes containing the α1c subunit (Hohaus et al. 2000).

Our data indicate that, when extrapolated in vivo, the interaction of the β1a subunit with α1s increases the Ca2+ influx during muscle activity. If this interaction is mediated by low-affinity sites, it would be expected to be more easily switched ‘on’ and ‘off’, according to the requirements of the muscle fibre for Ca2+ ions. Also, the steady-state inactivation changes of α1s currents induced by the β1a subunit may plausibly be explained by low-affinity interactions between these subunits. This type of interaction has been hypothesized to cause the shifts in steady-state inactivation of α1B currents in Xenopus oocytes observed after injection of high concentrations of β3 subunits (Canti et al. 2001). These shifts are similar to those described in the present paper.

Role of the β1a subunit on facilitation of muscle Ca2+ channels

We found that long and strong depolarizations increased the amplitude of a slow α1s tail current component. The origin of this component is presently unknown, although previous work in heart cells has shown that L-type channels are driven by long depolarizations into a slow gating mode characterized by long openings and high open probability (Pietrobon & Hess, 1990). Our experiments indicate that the β1a subunit promotes an increase in the amplitude of a slow component of tail currents that depends on the duration of the preceding depolarization. This component has been previously described in rat myoballs, where it is quite prominent (Fleig & Penner, 1995), and it has been associated with facilitation of muscle L-type channels (Fleig & Penner, 1996). Facilitation is a use-dependent regulation of channel activity that results in an increased Ca2+ influx by a preceding depolarization (Dolphin, 1996). Facilitation in rat myoballs was observed as an increase in current amplitude during a test pulse by a prepulse depolarization (Fleig & Penner, 1996). In agreement with these observations, an additional Ca2+ entry through CaV1.1 channels occurred during tetanic activity in rat myoballs (Sculptoreanu et al. 1993). Both phenomena, the slow tail current component and current facilitation during test pulses, have been proposed to depend on a common mechanism in rat myoballs (Fleig & Penner, 1996). In our experiments, no facilitation during test pulses was observed, which gives no support to this proposal. Furthermore, in the presence of the β1a subunit, CaV1.1 channel currents during the test pulse were still distinctly smaller when compared with those during the control pulse, suggesting that the slow component of tail currents and current facilitation are regulated differently by this auxiliary subunit.

Facilitation of the cardiac and the neuronal L-type channels has been observed when α1c is expressed in heterologous systems and it greatly depends on the coexpression of a β auxiliary subunit (Bourinet et al. 1994; Dai et al. 1999; Kamp et al. 2000). However, the role of the β subunit is less clear in other cases. Thus, facilitation is present even when α1 of smooth muscle is expressed alone in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (Kleppisch et al. 1994). The fact that the β1a subunit did not promote facilitation of CaV1.1 channels (this paper) may suggest that facilitation does not depend on the β1a subunit in skeletal muscle. Alternatively, it is also possible that facilitation requires phosphorylation of the β1a subunit. It has been previously shown that an increase in Ca2+ influx during repetitive activity depends on phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (Sculptoreanu et al. 1993). Finally, it is also possible that, under our experimental conditions, voltage-dependent inactivation of CaV1.1 channels overcame a relatively small facilitation that would otherwise have be seen.

Acknowledgments

The authors are most grateful to Dr Roberto Coronado for relevant discussions and to Dr Patricia Powers for the gift of β1a cDNA. We thank Ms Ascensión Hernández and Dr Juan Escamilla for their help in transfection and tissue culture experiments; Mr Alejandro Carapia and Mr Oscar Ramírez for excellent technical assistance; Mr Arturo Aldana for developing analysis programmes and Ms Susana Zamudio for excellent secretarial work. S.R. was supported by a fellowship from CONACyT. This work was supported by CONACyT grant no. 32055-N to J.S., grant no. 37356-N to M.G. and by NIH grant (DHHS) 1 R01 HL63903-01A1.

References

- Beurg M, Sukhareva M, Ahern CA, Conklin MW, Perez-Reyes E, Powers PA, Gregg RG, Coronado R. Differential regulation of skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ current and excitation-contraction coupling by the dihydropyridine receptor β1 subunit. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:1744–1756. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77336-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurg M, Sukhareva M, Strube C, Powers PA, Gregg RG, Coronado R. Recovery of Ca2+ current, charge movements, and Ca2+ transients in myotubes deficient in dihydropyridine receptor β1 subunit transfected with β1 cDNA. Biophysical Journal. 1997;73:807–818. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78113-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet D, Lecomte C, Sabatier JM, Felix R, De Waard M. Reversibility of the Ca2+ Channel α1-β subunit interaction. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;277:729–735. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E, Charnet P, Tomlinson WJ, Stea A, Snutch TP, Nargeot J. Voltage-dependent facilitation of a neuronal α1c L-type calcium channel. EMBO Journal. 1994;13:5032–5039. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho J, Carapia A, Calvo J, Garcia MC, Sanchez JA. Dihydropyridine-sensitive ion currents and charge movement in vesicles derived from frog skeletal muscle plasma membranes. Journal of Physiology. 1999;520:177–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho J, Delay M, Vazquez M, Argüelllo C, Sanchez JA. Transient outward K+ currents in vesicles derived from frog skeletal muscle plasma membranes. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:171–181. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79214-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canti C, Davies A, Berrow NS, Butcher AJ, Page KM, Dolphin AC. Evidence for two concentration-dependent processes for β-subunit effects on α1B calcium channels. Biophysical Journal. 2001;81:1439–1451. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75799-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Cao X, Sheridan DC, Coronado R. A novel α1s/β1a interaction in the DHPR of skeletal muscle relevant to excitation-contraction coupling. Biophysical Journal. 2002;82:78a. [Google Scholar]

- Dai S, Klugbauer N, Zong X, Seisenberger C, Hofmann F. The role of subunit composition on prepulse facilitation of the cardiac L-type calcium channel. FEBS Letters. 1999;442:70–74. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waard M, Pragnell M, Campbell KP. Ca2+ channel regulation by a conserved beta subunit domain. Neuron. 1994;13:495–503. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC. Facilitation of Ca2+ current in excitable cells. Trends in Neurosciences. 1996;19:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)81865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertel EA, Campbell KP, Harpold MM, Hofmann F, Mori Y, Perez-Reyes E, Schwartz A, Snutch TP, Tanabe T, Birnbaumer L, Tsien RW, Catterall WA. Nomenclature of voltage-gated calcium channels. Neuron. 2000;25:533–535. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeyer D, Melzer W, Pohl B, Zöllner P. Fast gating kinetics of the slow Ca2+ current in cut skeletal muscle fibres of the frog. Journal of Physiology. 1990;425:347–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig A, Penner R. Excessive repolarization-dependent calcium currents induced by strong depolarizations in rat skeletal myoballs. Journal of Physiology. 1995;489:41–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig A, Penner R. Silent calcium channels generate excessive tail currents and facilitation of calcium currents in rat skeletal myoballs. Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:141–153. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flockerzi V, Oeken HJ, Hofmann F, Pelzer D, Cavalie A, Trautwein W. Purified dihydropyridine-binding site from skeletal muscle t-tubules is a functional calcium channel. Nature. 1986;323:66–68. doi: 10.1038/323066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerster U, Neuhuber B, Groschner K, Striessnig J, Flucher BE. Current modulation and membrane targeting of the calcium channel αc subunit are independent functions of the β subunit. Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:353–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0353t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg RG, Messing A, Strube C, Beurg M, Moss R, Behan M, Sukhareva M, Haynes S, Powell JA, Coronado R, Powers PA. Absence of the β subunit (cchb1) of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor alters expression of the α1 subunit and eliminates excitation-contraction coupling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:13961–13966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Biel M, Flockerzi V. Molecular basis for Ca2+ channel diversity. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1994;17:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.002151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohaus A, Poteser M, Romanin C, Klugbauer N, Hofmann F, Morano I, Haase H, Groschner K. Modulation of the smooth-muscle L-type Ca2+ channel α1 subunit (α1C-b). by the β2a subunit: a peptide which inhibits binding of β to the I-II linker of a1 induces functional uncoupling. Biochemical Journal. 2000;348:657–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CLH. Functional components of the non-linear charge. In: Huang CLH, editor. Intramembrane Charge Movements in Striated Muscle. Vol. 44. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1993. pp. 96–115. [Google Scholar]

- Isom LL, De Jongh KS, Catterall W. Auxiliary subunits of voltage gated ion channels. Neuron. 1994;12:1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson IR, Varadi G. The β subunit increases Ca2+ currents and gating charge movements of human cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:1285–1293. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79685-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp TJ, Hu H, Marban E. Voltage-dependent facilitation of cardiac L-type Ca channels expressed in HEK-293 cells requires beta-subunit. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2000;278:H126–136. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp TJ, Perez-Garcia MT, Marban E. Enhancement of ionic current and charge movement by coexpression of calcium channel beta 1A subunit with alpha 1C subunit in a human embryonic kidney cell line. Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:89–96. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleppisch T, Pedersen K, Strubing C, Bosse-Doenecke E, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F, Hescheler J. Double-pulse facilitation of smooth-muscle alpha-1-subunit Ca2+ channels expressed in CHO cells. EMBO Journal. 1994;13:2502–2507. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizanova O, Varadi M, Schwarz A, Varadi G. Coexpression of skeletal muscle voltage-dependent calcium channel α1 and β cDNAs in mouse Ltk− cells increases the amount of α1 protein in the cell membrane. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1995;211:921–927. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda AE, Kim HS, Ruth P, Perez-Reyes E, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F, Birnbaumer L, Brown AM. Normalization of current kinetics by interaction between the α1 and β subunits of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channel. Nature. 1991;352:527–530. doi: 10.1038/352527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb GD. DHP receptors and excitation-contraction coupling. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1992;13:394–405. doi: 10.1007/BF01738035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane D. Immunoblotting. In: Harlow E, editor. Antibodies, A Laboratory Manual. NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1990. pp. 471–510. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Coronado R. Heterogeneity of conductance states in calcium channels of skeletal muscle. Biophysical Journal. 1988;53:387–395. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83115-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer W, Hermann-Frank A, Lüttgau HC. The role of Ca2+ ions in excitation-contraction coupling of skeletal muscle fibres. Biochemica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1241:59–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(94)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely A, Wei X, Olcese R, Bimbaumer L, Stefani E. Potentiation by the β subunit of the ratio of the ionic current to the charge movement in the cardiac calcium channel. Science. 1993;262:575–578. doi: 10.1126/science.8211185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman SL, Barwick JL, Elshourbagy NA, Guzeliam PS. Measurement of the metabolism of cytochrome P-450 in cultured hepatocytes by a quantitative and specific immunochemical method. Biochemical Journal. 1992;204:281–290. doi: 10.1042/bj2040281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E, Klim HS, Lacerda A, Horne W, Wei X, Rampe D, Campbell KP, Brown AM, Birnbaumer L. Induction of calcium currents by the expression of the α1-subunit of the dihydropyridine receptor from skeletal muscle. Nature. 1989;340:233–236. doi: 10.1038/340233a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobon D, Hess P. Novel mechanism of voltage-dependent gating in L-type calcium channels. Nature. 1990;346:651–655. doi: 10.1038/346651a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pragnell M, De Waard M, Mori Y, Tanabe T, Snutch TP, Campbell KP. Calcium channel beta-subunit binds to a conserved motif in the I-II cytoplasmic linker of the alpha 1-subunit. Nature. 1994;368:67–70. doi: 10.1038/368067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M, Neher E. Rates of diffusional exchange between small cells and a measuring patch pipette. Pflügers Archiv. 1988;411:204–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00582316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebolledo S, García R, Escamilla J, Carapia A, García MC, SÁnchez JA. Actions of β1 subunit on L-type currents of adult frog and mouse skeletal muscle. Biophysical Journal. 2002;82:575. [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Hall LM. Functional expression and characterization of skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:22393–22396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios E, Pizarro G. Voltage sensor of excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Physiological Reviews. 1991;71:849–908. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.3.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez JA, Stefani E. Kinetic properties of calcium channels of twitch muscle fibres of the frog. Journal of Physiology. 1983;337:1–17. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasse J, Gallagher SR. Detection of proteins. In: Ausubel FM, editor. Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. pp. 1029–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LM, McCleskey EW, Almers W. Dihydropyridine receptors in muscle are voltage-dependent but most are not functional calcium channels. Nature. 1985;314:747–51. doi: 10.1038/314747a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sculptoreanu A, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Voltage-dependent potentiation of L-type Ca2+ channels due to phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Nature. 1993;364:240–243. doi: 10.1038/364240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AJ. Electrophoretic separation of proteins. In: Ausubel FM, editor. Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. pp. 1023–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Standen NB, Stanfield PR, Ward TA, Wilson SW. A new preparation for recording single-channel currents from skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1984;221:455–464. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1984.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szentesi P, Jacquemond V, Kovács L, Csernoch L. Intramembrane charge movement and sarcoplasmic calcium release in enzymatically isolated mammalian skeletal muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1997;505:371–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.371bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tareilus E, Roux M, Qin N, Olcese R, Zhou J, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. A Xenopus oocyte beta subunit: evidence for a role in the assembly/expression of voltage-gated calcium channels that is separate from its role as a regulatory subunit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U S A. 1997;94:1703–1708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadi G, Lory P, Schultz D, Varadi M, Schwartz A. Acceleration of activation and inactivation by the β subunit of the skeletal muscle calcium channel. Nature. 1991;352:159–162. doi: 10.1038/352159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, De Waard M. Subunit interaction sites in voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels: role in channel function. Trends in Neurosciences. 1998;21:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Colecraft HM, Demaria CD, Peterson BZ, Zhang R, Kohout TA, Rogers TB, Yue DT. Ca2+ channel modulation by recombinant auxiliary β subunits expressed in young adult heart cells. Circulation Research. 2000;86:175–184. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witcher DR, De Waard M, Liu H, Pragnell M, Campbell KP. Association of native Ca2+ channel β subunits with the α1 subunit interaction domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:18088–18093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.18088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Hara M, Strobeck M, Fukasawa K, Schwartz A, Varadi G. Multiple modulation pathways of calcium channel activity by a β subunit. Direct evidence of β subunit participation in membrane trafficking of the α1c subunit. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:19348–19356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]