Abstract

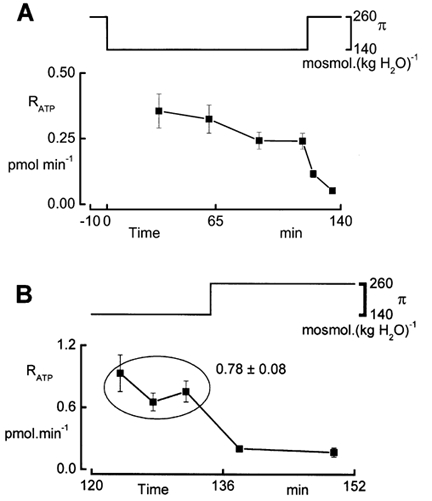

In renal A6 epithelia, an acute hypotonic shock evokes a transient increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) through a mechanism that is sensitive to the P2 receptor antagonist suramin, applied to the basolateral border only. This finding has been further characterized by examining ATP release across the basolateral membrane with luciferin-luciferase (LL) luminescence. Polarized epithelial monolayers, cultured on permeable supports were mounted in an Ussing-type chamber. We developed a LL pulse protocol to determine the rate of ATP release (RATP) in the basolateral compartment. Therefore, the perfusion at the basolateral border was repetitively interrupted during brief periods (90 s) to measure RATP as the slope of the initial rise in ATP content detected by LL luminescence. Under isosmotic conditions, 1 μl of A6 cells released ATP at a rate of 66 ± 8 fmol min−1. A sudden reduction of the basolateral osmolality from 260 to 140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 elevated RATP rapidly to a peak value of 1.89 ± 0.11 pmol min−1 () followed by a plateau phase reaching 0.51 ± 0.07 pmol min−1 (). Both and values increased with the degree of dilution. The magnitude of remained constant as long as the hyposmolality was maintained. Similarly, a steady ATP release of 0.78 ± 0.08 pmol min−1 was recorded after gradual dilution of the basolateral osmolality to 140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1. This RATP value, induced in the absence of cell swelling, is comparable to . Therefore, the steady ATP release is unrelated to membrane stretching, but possibly caused by the reduction of intracellular ionic strength during cell volume regulation. Independent determinations of dose-response curves for peak [Ca2+]i increase in response to exogenous ATP and basolateral hyposmolality demonstrated that the exogenous ATP concentration, required to mimic the osmotic reduction, was linearly correlated with . The link between the ATP release and the fast [Ca2+]i transient was also demonstrated by the depression of both phenomena by Cl− removal from the basolateral perfusate. The data are consistent with the notion that during hypotonicity, basolateral ATP release activates purinergic receptors, which underlies the suramin-sensitive rise of [Ca2+]i during the hyposmotic shock.

Virtually all cell types appear to possess mechanisms that enable the release of their main intracellular energy source, i.e. ATP. In many instances, excreted ATP has a signalling function in auto- or paracrine feedback regulation by activating purinergic receptors of the P2 family (Burnstock & Williams, 2000). The P2 purinoceptor family consists of two major subtypes, P2X and P2Y, representing the ligand-gated cation channels (Ca2+ and Na+ permeable) and the G-protein-coupled receptors (mostly linked to the activation of phospholipase C), respectively. Some receptor subtypes even react better to ADP that appears after ATP degradation by membrane-bound ecto-ATPases. Interestingly, activation of both receptor subtypes can result in a change of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). The present study was undertaken to investigate whether ATP release is correlated with the transient elevation of [Ca2+]i observed in response to hypotonicity.

Release of ATP has been demonstrated in response to osmotic, mechanical and neurohormonal stimuli. In particular, several groups have extensively examined ATP release in response to a sudden dilution of medium osmolality (Taylor et al. 1998; Van der Wijk et al. 1999; Kimura et al. 2000; Mitchell, 2001; Romanello et al. 2001). Moreover, it has been suggested that the release of ATP regulates cell volume by activation of volume-sensitive Cl− channels (Wang et al. 1996). Cell swelling occurs both in normal (metabolism, cell differentiation, transepithelial transport, osmotic adaptation) and in pathological conditions (atrophy, apoptosis, hypertrophy). Specifically, when responding to a sudden decrease in extracellular osmolality, the rapid swelling of the cells may evoke mechanical perturbation, eventually leading to cell damage, creating a pathway for ATP to appear in the perfusion solutions. Nevertheless, such a mechanism can still have physiological implications, as for instance in the release of ATP from the epithelium of the guinea pig ureter caused by distension of this organ (Knight et al. 2002), while in this study epithelial damage was ruled out by an appropriate assay.

Since ATP is highly ionized at intracellular pH, its release probably occurs through either a conductive pathway or a vesicular release mechanism. Accordingly, several anion conductive pathways have been proposed to mediate the release of ATP. For instance, it has been suggested that the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (Braunstein et al. 2001), and the related multidrug-resistance-1 protein (Roman et al. 2001) are both involved in the regulation of membrane permeability for ATP in response to cell swelling. In addition, a volume-regulated large conductive anion channel has been proposed as a possible pathway for swelling-induced ATP release (Sabirov et al. 2001). Since cell swelling inevitably induces deformation of the plasma membrane, the activation of stretch-sensitive channels has been suggested to mediate ATP release. Thus, Gd3+, a blocker of stretch-activated ion channels, has been shown to inhibit ATP release (Roman et al. 1999). However, recently Boudreault & Grygorczyk (2002) questioned the inhibitory capacity of Gd3+ on ATP release and even showed that the lanthanide activates ATP excretion. More recently, connexin hemichannels have been identified as a signalling pathway that couples ATP liberation to intracellular Ca2+ changes after mechanical stimulation of astrocytes (Stout et al. 2002).

The uncertainties concerning signal transduction and the identity of pathways underlying ATP release partially stem from a variety of methodological problems in assaying ATP release. The most commonly used and sensitive technique for assaying ATP release is based on the luminescence that follows oxidation of luciferin upon catalysis by luciferase in the presence of oxygen, Mg2+ and ATP. When using this principle, the assay is confounded by a multitude of factors including: (1) ATP release by mere mechanical stimulation, (2) effects of unstirred layers, (3) sequestration of ATP released into the microdomains of the lateral intercellular spaces (LIS), (4) lack of selective inhibitors that modulate ATP release through candidate ion channels, (5) extremely low levels of release coupled with rapid extracellular ATP hydrolysis by membrane-bound ecto-ATPases, and finally (6) consumption of ATP by the assay reaction itself. In addition, the activity of luciferase is often sensitive to properties of the perfusate such as ionic strength and agents used to block ion channels for ATP release. In an ideal approach, real time detection of ATP release would be desirable with a high temporal resolution and with minimal mechanical stimulus to the cells. However, recording of ATP content by the assay reaction can be achieved only in stop flow conditions enabling continuous exposure to luciferin and luciferase. The apparatus for the assay must support the use of polarized monolayers with independent control over perfusion at the apical and basolateral borders. This would permit identification of the polarity of ATP release and association with ion channel expression in the corresponding membrane domain.

In spite of the large number of studies that have been carried out, a number of issues regarding ATP release in response to hypotonicity remain unclear. Specifically, the question of whether ATP release parallels the [Ca2+]i rise is not well established with sufficient details. In our laboratory, the A6 epithelium is used as a model tight epithelium for the study of the activation of transepithelial transport in response to hyposmotic solutions (Jans et al. 2000). We recently described a biphasic increase in [Ca2+]i via independent activation of Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ pools and a Mg2+-sensitive non-capacitative Ca2+ entry pathway in the basolateral membrane (Jans et al. 2002). Our interest in ATP release was triggered because the first phase of the [Ca2+]i rise during hypotonic shock was selectively inhibited by the presence of suramin, a P2 receptor antagonist, in the basolateral bath (Jans et al. 2002). The objective of this study was to test the autocrine activation hypothesis through direct assessment of ATP release and by obtaining a correlation between magnitudes of ATP release and the rise in [Ca2+]i. To measure ATP release from the A6 epithelium, we applied the bioluminescence detection assay using luciferase as the reporting enzyme. We designed a setup that enabled us to obtain reliable records of the rate of basolateral ATP release. Specifically, we show that in A6 cells, basolateral ATP release underlies the rise of [Ca2+]i that occurs immediately after exposure to basolateral hypotonicity.

Methods

Cell culture

The amphibian A6 renal cell line (a kind gift of Dr J. P. Johnson, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) is derived from the distal part of the nephron of Xenopus laevis. A6 cells were grown on permeable Anopore filters (pore size 0.2 μm; Nunc Intermed, Roskilde, Denmark) in a humidified incubator maintained at 28 °C and 1 % CO2. Cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cm−2. The growth medium was renewed twice weekly and consisted of a 1:1 mixture of Leibovitz's L-15 and Ham's F-12 media, supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 3.8 mm l-glutamine, 2.6 mm NaHCO3, 95 IU ml−1 penicillin and 95 μg ml−1 streptomycin. We employed polarized monolayers cultured for 6 to 9 days.

Solutions and chemicals

Hyposmotic solutions (140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 contained (mm): 70 Na+, 2.5 K+, 1 Ca2+, 5 Hepes and 69.5 Cl− (pH + 7.4). Isosmotic solutions (260 mosmol (kg H2O)−1) were prepared by adding 65 mmNaCl and in one series of experiments by the addition of 110 mm sucrose. Solutions of different osmolalities were prepared by varying the concentration of NaCl. In certain experiments, Cl− was replaced by SO42-. Hyposmotic SO42- solutions (140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1) contained (mm): 115 Na+, 2.5 K+, 1 Ca2+, 5 Hepes and 57.25 SO42- (pH + 7.4). Isosmotic SO42- solutions were prepared by adding 110 mm sucrose. The amount of ATP release in the basolateral compartment was determined with a luciferin-luciferase kit purchased from Sigma (FL-AAM, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). The solutions that we used to probe for ATP release contained 50 μl of the luciferin-luciferase (LL) assay mixture per ml. This resulted in a final concentration for the following components (mm): 0.5 MgSO4, 0.05 EDTA, 0.005 dithiothreitol, 2.5 tricine, and 0.03 luciferin; and (in mg l−1): 3.3 luciferase, and 50 bovine serum albumin. Calibration curves were recorded with the same amount of the LL reagent (50 μl ml−1).

Intracellular Ca2+ measurements

Cells were loaded apically with a solution containing 10 μm Fura 2/AM (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and 0.2 g l−1 pluronic acid (F-127, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 120 min in the incubator. After washing off the excess dye, the monolayer was placed upside-down in an Ussing-type chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a 40× objective (Zeiss LD, Achroplan, Wetzlar, Germany). The apical and basolateral surfaces of the monolayer were perfused separately at room temperature. Fluorescence emissions to excitation at 340 and 380 nm were filtered through a band pass filter centred at 510 nm (bandwidth 6 nm) and detected by photon counting (Hamamatsu H3460-04, Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan). Emission at each of the excitation wavelengths was corrected for autofluorescence with signals from monolayers (n = 10) not exposed to Fura 2. The ratio of corrected fluorescence excited at 340 nm to that excited at 380 nm (i.e. R + I340/I380) was used to estimate [Ca2+]i (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985):

| (1) |

where Rmax and Rmin are the corrected fluorescence ratios under saturating and Ca2+-free conditions in the presence of ionomycin (5 μm), respectively. Kd, the dissociation constant of Fura 2 for Ca2+, was taken as 224 nm (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985) and Rc is the ratio of the corrected fluorescence intensities at 380 nm excitation in zero and saturating Ca2+.

Measurement of ATP release

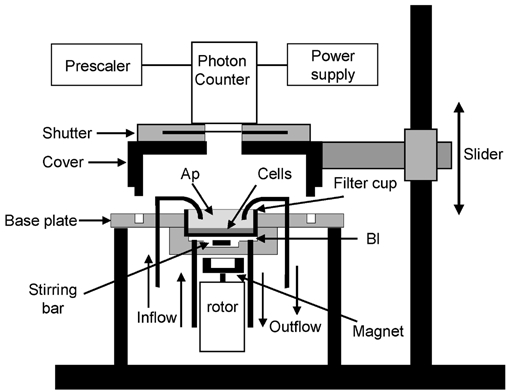

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the experimental setup for real-time recording of ATP release based on luciferin-luciferase (LL) bioluminescence. To minimize cell damage, we did not remove the filter supporting the epithelium from the filter cup. Thus, the entire filter cup containing the polarized epithelium was mounted apical side up into a container that separated the apical and basolateral compartments. The container was inserted in a light-tight compartment. The setup allows separate perfusion of both the apical and basolateral borders through black light-tight tubing at a rate of 2 and 5 ml min−1, respectively. The volumes of the apical and basolateral compartments were 2 and 1 ml, respectively. The accumulation of ATP in the basolateral solution was probed with the luciferin-luciferase assay. Photons emitted as a result of the oxidation of luciferin by luciferase in the presence of ATP were detected by a photon-counting tube (Type H3460-04, Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan) that was positioned 2 cm above the apical surface of the cells. Light impulses were discriminated, prescaled and counted with a PC-based 32-bit counter/timer board (PCI-6601, National Instruments Corporation, Austin, TX, USA). The number of impulses occurring during a 1 s time interval was monitored with custom-built software. The time course of the number of counts was graphically displayed. The number of background counts recorded in the absence of LL was 35-45 counts s−1. The dynamic range of the system extended to 232-1. Data were stored on disk and analysed off-line for determination of the rate of ATP release as discussed in Results.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the experimental setup for measuring luminescence.

The entire filter cup that supports the epithelium is mounted in a holder that separates the apical (Ap) and basolateral (Bl) compartments. Perfusions of each chamber half proceed through black light-tight tubing. The volume of the basolateral compartment was 1 ml. The diffusion of ATP into the basolateral bath through the Anopore filter was accelerated by vigorously mixing the solution with a magnetic stirring bar coupled to a rotating magnet. The volume of the solution in contact with the apical side of the epithelium was 2 ml. The photon counter tube protected by a shutter device was mounted on a support that could easily be lifted to install the filter cup with cells. Changing the perfusates was possible without interrupting photon counting.

The diffusion of ATP released through the filter matrix was accelerated by mixing the basolateral solution with a stirring bar, kept in rotation with a magnet attached to an air-driven rotor. Stirring did not cause ATP release in either isotonic or hypotonic conditions and the rotating magnet did not produce electromagnetic interferences with the photon counting system. Rotation frequency was monitored by detection of the changes in magnetic flux in a coil placed in the vicinity of the rotating magnet, giving rise to an alternating voltage displayed on a digital oscilloscope equipped with circuitry to determine the frequency of the alternating signal. Air pressure was manually adjusted to keep the rotation frequency near 1200 r.p.m. The effect of stirring on ATP washout was verified by recording ATP accumulation in the basolateral compartment after cells were suddenly destroyed by addition of Triton X-100 to the apical compartment. Paired experiments showed that stirring doubled the rate of rise of the amount of ATP in the basolateral compartment from 3.3 ± 0.7 to 7.9 ± 2.4 pmol min−1. It should be noted that in this type of experiment, the rates of ATP release depend on the concentration of ATP at the upper side of the filter. Even so, as will be discussed later, even with stirring, ATP release in the basolateral bath was noticeably delayed because of the diffusion barrier constituted by the filter.

ATP released into the perfusate was probed with the LL assay, based on the oxidative decarboxylation of luciferin (LH2) catalysed by luciferase in the presence of ATP, Mg2+ and O2 for the production of light (hυ, λmax + 560 nm) (Gomi & Kajiyama, 2001):

|

(2) |

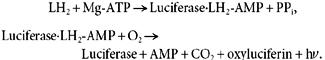

ATP release at each border could be assessed separately by adding the reagent to the appropriate compartment, while solutions lacking the reagent were at the opposite side. In this paper, we report only data concerning basolateral release of ATP. To determine the amount of ATP released by the cells, the data were related to values obtained from the calibration curves of ATP (Na+ salt) at known concentrations in the presence of 50 μl LL reagent per ml solution. The activity of luciferase was influenced by the different conditions of the protocol, such as salt concentration and chemical compounds. Therefore, calibration curves for ATP release were recorded for all experimental conditions. We recorded the calibration curves with the setup depicted in Fig. 1. To obtain a similar geometric arrangement between the photon counting tube and the test solution in the basolateral compartment, we inserted blank Anopore filters (i.e. without cells) with a coverslip glued at the edges of the filter cup. With this arrangement, emitted light had to pass through the filter as in the actual experiments and hence calibration results accounted for attenuation of the light signal by the filter. Nevertheless, the light absorbance by the filter appeared to be negligible because signals obtained with a Lucite cup having a polished bottom were comparable to those obtained with the filter cup. Figure 2 shows a typical calibration curve recorded at 140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1. The activity of luciferase was inversely proportional to the ionic strength of the solution. Table 1 summarizes the results for each of the conditions used in this study. Calibration curves were recorded in the concentration range of ATP that was found during the experiments where the ATP release elicited by the different hyposmotic shocks was studied.

Figure 2. Calibration of the ATP measurements.

Calibration was performed using the experimental setup depicted in Fig. 1. The luminescence that originated from the standard solution in the basolateral compartment was recorded with a cell free culture cup. The LL reagent was added to the ATP containing solutions at 50 μl ml−1. A, time course of the luminescence signal recorded with hyposmotic solutions (140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1). The basolateral bath was continuously perfused and flow was interrupted after 5 ml of an LL reagent-containing solution had passed the chamber. During the indicated periods, the increase in luminescence expressed as counts per second was recorded with different amounts of ATP (QATP) ranging from 0.1 to 10 pmol, corresponding to concentrations between 0.1 and 10 nm. B, linear regression of luminescence (photon counts) versus ATP amount (QATP) of the experiment depicted in A.

Table 1.

Calibration of the ATP measurements

| Solution | Osmolality mosmol (kg H2O)−1 | Counts per pmol ATP (s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Cl−1 | 260 | 568 |

| 200 | 586 | |

| 170 | 693 | |

| 155 | 708 | |

| 140 | 724 | |

| SO42− | 260 | 958 |

| 140 | 1265 |

Since the amount of released ATP is proportional to the number of cells on the filter, ATP release was expressed per μl of cells. We used the intact epithelium cultured on filters of 25.4 mm diameter. The thickness of the A6 epithelium as studied in our laboratory was 6.27 μm (Van Driessche et al. 1999). Consequently, the total volume of the epithelium cultured on the Anopore filter was approximately 3 μl. Data are reported as means ± s.e.m.

Results

ATP accumulation

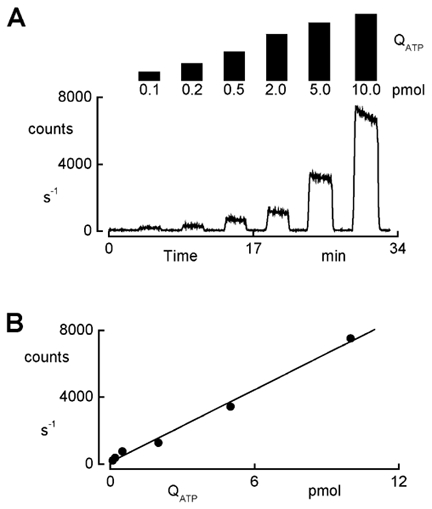

In our initial approach to assessment of ATP release into the basolateral compartment, we recorded the accumulation of ATP after interruption of the perfusion. Figure 3A illustrates a typical experiment where ATP accumulation was monitored during hypotonic conditions. Hypotonic shock was initiated by decreasing the basolateral osmolality. The apical perfusate was made hyposmotic at least 30 min in advance. We could use this procedure because the apical membrane of A6 epithelia is water impermeable, so cells do not swell because of this manoeuvre (De Smet et al. 1995). An osmotic gradient across the tissue directed from the apical to basolateral side is avoided when lowering the osmolality of the basolateral bath because such a gradient opens the paracellular pathway, thus increasing the shunt conductance. On the other hand, imposing the opposite osmotic gradient (basolateral to apical) during phases where the basolateral bath is isosmotic does not affect the shunt conductance. After a 20 min period of exposure to hyposmotic solutions, we added LL to the basolateral perfusate and allowed the accumulation of ATP by suspending the perfusion. Arresting the perfusion of the LL-containing solution resulted in a gradual increase in luminescence that showed a tendency to reach a plateau after 20 min. Thus, we restricted the observation time of the ATP accumulation to 20-30 min. The increase in luminescence is influenced by a number of factors including: (1) the rate of ATP release (RATP), (2) the rate of ATP degradation by ecto-ATPases, characterized by a rate constant , (3) the consumption of ATP as a consequence of oxidation of luciferin catalysed by luciferase (eqn (2)), and (4) the possible loss of activity of luciferase and/or luciferin. We characterized the decrease in luminescence caused by factors 3 and 4 with a rate constant, denoted as . To verify whether has a significant influence on the observed luminescence, we monitored the time course of luminescence in response to 2 pmol ATP in hyposmotic salt solutions (Fig. 3B). The response followed an exponential decline with a rate constant (+ 0.017 ± 0.006 min−1, n = 5), reflecting the progress of the oxidation reaction. Because luciferin (30 μm) and luciferase (3.3 mg l−1) are present in excess amounts, the loss of their activity is probably negligible so that reflects mostly the consumption of ATP by the reaction with LL.

Figure 3. ATP accumulation in the basolateral compartment during hypotonicity.

A, recording of ATP accumulation. Initially, the epithelium was exposed to isosmotic solutions (260 mosmol (kg H2O)−1) and osmolality was reduced to 140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 by removal of NaCl. ATP accumulation was recorded during hypotonicity after addition of the LL reagent and interruption of the perfusion. The first recording was initiated 20 min after imposing the hyposmotic challenge. Accumulation of ATP was monitored for 20 and 30 min periods during the first and subsequent LL exposures, respectively. The rate of ATP release (RATP) was determined as the slope of the initial rise in ATP content (QATP) in the chamber compartment. The rate constant of disappearance (DATP) was calculated by fitting an exponential function (eqn (4)) to the data. Mean values of RATP and DATP are listed in Table 2. B, consumption of ATP. The rate constant of ATP consumption () was determined in cell-free experiments using a Lucite cup to seal the basolateral compartment. Introducing a hyposmotic salt solution containing 2 pmol ATP and the LL reagent in the basolateral compartment rapidly increased luminescence. Subsequently the signal followed an exponential decay. The mean value of the time constant determined from five experiments was 58.0 ± 1.1 min−1. C, model calculations of ATP accumulation based on eqn (4) with RATP + 3 pmol min−1 and DATP + 0.25 min−1. RATP is the slope of the rise in QATP, and the plateau level represents the ratio between RATP and DATP.

The time course of the luminescence in Fig. 3A can be resolved into two distinct components: (1) the initial rate of rise, and (2) the plateau phase. The time course of the luminescence reflects the change of the total amount of ATP in the bath (QATP) that can be modelled as follows:

| (3) |

where RATP is the rate of release of ATP, DATP is the rate constant of disappearance of ATP, caused by consumption (, determined in Fig. 3B) and degradation (). Equation (3) also assumes that the LL reagent mixture is instantaneously introduced and mixed in the chamber. Integration of eqn (3) results in:

| (4) |

Equation (4) shows that the accumulation of ATP proceeds exponentially and reaches a plateau value RATP/DATP. According to eqn (3), the initial rate of rise equals RATP. The observed profile of the luminescence (Fig. 3A) is consistent with eqn (4) and the model calculations illustrated in Fig. 3C.

In the experiment depicted in Fig. 3A, we recorded ATP accumulation during four successive periods of 20-30 min duration where we added the LL mixture to the basolateral compartment and interrupted the perfusion. We found that the amount of ATP reached at the end of the accumulation period was quite variable. We calculated RATP from the slope of the QATP increase. The rate constant for disappearance (DATP ++), was determined by exponential curve fitting of the data in Fig. 3A. Results are listed in Table 2. The data show that RATP did not markedly change during the last three periods of ATP accumulation in the basolateral compartment. On the other hand, DATP varied noticeably, which is also reflected in the magnitude of the plateau phase (RATP/DATP). Comparison of DATP with shows that consumption of ATP proceeded at a much lower rate than degradation. This observation may indicate that the variability of DATP is probably due to the fluctuating activity of the ecto-ATPases.

Table 2.

RATP and DATP during repetitive exposures to LL

| Pulse number | Duration (min) | RATP (pmol min−1) | DATP (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | 0.508 ± 0.093 | 0.415 ± 0.060 |

| 2 | 30 | 0.219 ± 0.036 | 0.205 ± 0.022 |

| 3 | 30 | 0.291 ± 0.071 | 0.388 ± 0.108 |

| 4 | 30 | 0.225 ± 0.048 | 0.432 ± 0.122 |

Mean values (n = 5) of RATP and DATP recorded in ATP accumulation experiments depicted in Fig. 3A with successive LL pulses of 20 or 30 min duration as indicated in the second column. The first pulse was initiated 20 min after imposing hypotonicity. Time between the successive pulses was 5 min.

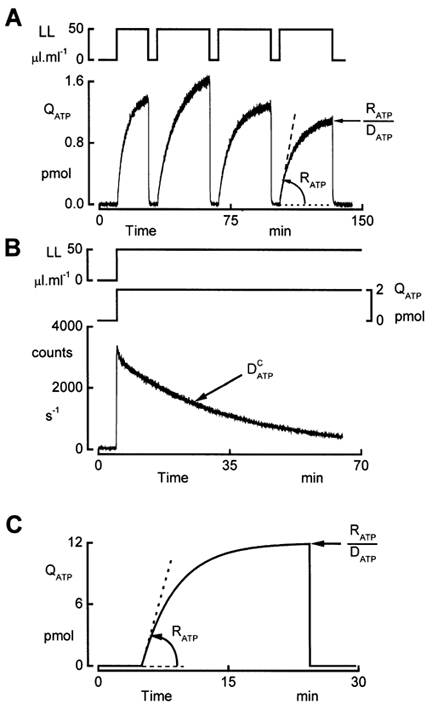

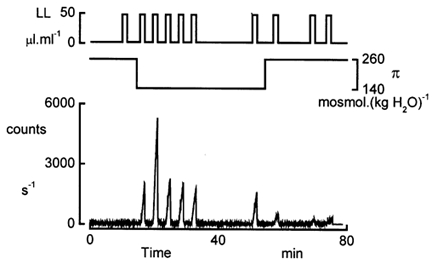

Pulse protocol

Based on the principles and observations described in the preceding section, we designed a pulse protocol to measure RATP. The continuous perfusion of the basolateral compartment (5 ml min−1) was interrupted for brief periods of 90 s (Fig. 4). At the beginning of these intervals, the solution containing the LL reagent was infused into the basolateral compartment of the chamber. The initial rate of rise of the luminescence, proportional to the ATP release, was determined by regression analysis. Following this type of protocol, we were able to assess the time course of the ATP release before, during and after application of the hyposmotic shock. In isosmotic conditions, RATP was small but could still be determined because of the high sensitivity of the system. Upon sudden reduction of the basolateral osmolality, the rate of luminescence increase during the LL pulses was much larger than in isosmotic conditions (Fig. 4). This augmentation of the luminescence was reflected in the increase of RATP that reached a peak value + 1.89 ± 0.11 pmol min−1 (n = 6). Subsequently, RATP declined slowly to a plateau level + 0.51 ± 0.07 pmol min−1. The plateau phase persisted as long as the hyposmolality was maintained. Returning to isosmotic solutions reduced RATP to a new baseline within 4-5 min. It is noteworthy that after a reduction of the osmolality by more than 100 mosmol (kg H2O)−1, RATP remained markedly above control values (Table 3). At the end of the experiment, we added Triton X-100 together with the LL reagent to the apical bath to assess the total amount of ATP in the cells. The amount of ATP was determined from the maximum of the luminescence signal that was reached a few seconds after addition of Triton X-100. Total ATP content approximated 1093 ± 89 pmol (μl cells)−1 (n = 20).

Figure 4. Pulse protocol.

Example of an experiment where the basolateral osmolality (π) was reduced to 140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1. The basolateral compartment was continuously perfused at a rate of 5 ml min−1 with isosmotic or hyposmotic solutions. The perfusion was interrupted during 90 s intervals after 5 ml of the LL-containing solutions had passed the basolateral bath. RATP was calculated from the slope of increase in luminescence and the calibration factor listed in Table 1. The sensitivity and high dynamic range of the photon counter enabled the determination of RATP in iso- as well as in hyposmotic conditions.

Table 3.

Effect of strength of osmotic stress on RATP (pmol min−1)

| Δπ(mosmol (kg H20)−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 90 | 105 | 120 | |

| 1, ISO | 0.033 ± 0.008 | 0.045 ± 0.021 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.018 ± 0.002 |

| 2, | 0.194 ± 0.090 | 0.316 ± 0.050 | 0.686 ± 0.070 | 1.887 ± 0.105 |

| 3, | 0.107 ± 0.025 | 0.206 ± 0.035 | 0.229 ± 0.041 | 0.510 ± 0.065 |

| 4, ISO-1 | 0.056 ± 0.011 | 0.093 ± 0.012 | 0.091 ± 0.013 | 0.168 ± 0.017 |

| 5, ISO-2 | 0.041 ± 0.007 | 0.054 ± 0.007 | 0.039 ± 0.005 | 0.075 ± 0.007 |

| 6, ISO-3 | 0.040 ± 0.005 | 0.043 ± 0.006 | 0.038 ± 0.010 | 0.056 ± 0.007 |

RATP values referred to 1 μl of cells were recorded during experiments as depicted in Fig. 5 while the basolateral osmolality was decreased by the value (Δπ) indicated in the first row of the table. ISO values were recorded prior to the hypotonic challenge. and values were recorded at time 6 and 37 min after initiation of the osmotic perturbation. ISO-1, ISO-2 and ISO-3 are values obtained 3.5, 15 and 19 min after restoring isosmotic conditions. The numbers refer to the recordings marked in Fig. 5.

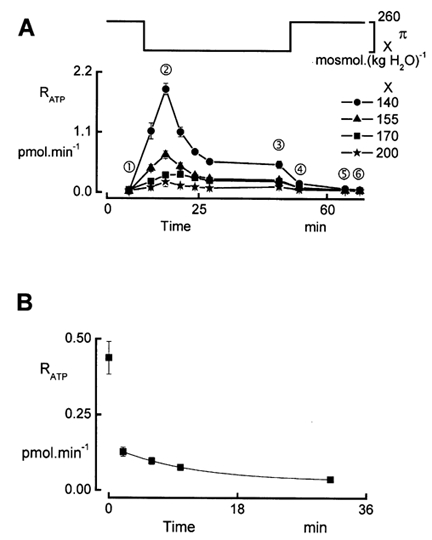

Dependence of ATP release on degree of hyposmotic perturbation

We next assessed RATP at different degrees of reduction in osmolality from 260 to 140, 155, 170 and 200 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 by varying the concentration of NaCl in the perfusate. As noted in Methods, luminescence vs. ATP concentration was calibrated in cell-free conditions for all osmotic conditions (Table 1). Figure 5 compares the time courses of ATP release for the different hyposmotic shocks. Both and varied with the strength of the hyposmotic shock (Table 3), indicating that the amount of ATP release depends on the degree of dilution. Two striking features emerge from these records: (1) the transient peak in ATP release and (2) the steady plateau level observed during the entire period of hyposmolality. The first issue may be related to the release of Ca2+ from the intracellular stores (Jans et al. 2002).

Figure 5. Time course of RATP during and after hyposmotic shocks.

A, dependence of ATP release on the size of the osmotic perturbation. Effect on RATP of reducing the osmolality (π) from 260 to 200, 170, 155 and 140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 (symbols for each concentration are shown on the right). During the entire experiment, we perfused the apical side with solutions having an osmolality equal to the osmolality of the basolateral hyposmotic solution. The osmotic perturbation was induced by NaCl removal. Probing of ATP release was performed in isosmotic conditions prior to and after the hypotonic shock, and in hyposmotic conditions at 2, 6, 10, 14, 18 and 37 min after the initiation of the hypotonic shock. Data points are means ± s.e.m. (n = 5). B, time course of the decay of RATP after restoring isosmotoc conditions. During the post-hyposmotic period we recorded RATP with an higher time resolution. An exponential function was fitted to the data recorded in isosmotic conditions (time constant 10.6 min). The area under the exponential curve amounted to 1.16 pmol.

However, it should be noted that the peak in [Ca2+]i occurred 30 s after the initiation of the hyposmotic challenge and thus preceded the peak in ATP release that was recorded 5 min later. This delay may be caused by a rather small diffusion rate of ATP through the filter matrix. We attempted to estimate the diffusion coefficient of ATP through the filter (DFIL) in experiments where we exposed the upper side of the filter to ATP and monitored its appearance in the lower compartment with luminescence. Efflux of ATP from the filter (JATP) was determined as the initial rate of rise of QATP in the lower compartment as described in the experiments above. According to Fick's first law, JATP (pmol min−1) is proportional to the ATP concentration gradient across the filter:

| (5) |

JATP was measured at Δ[ATP] + 0.25, 1 and 10 μm and by linear regression analysis we calculated DFIL + 0.0035 l min−1. This low value of DFIL will cause a significant delay in the ATP release recordings. However, it should be noted that the conditions for determination of DFIL were quite different from those when ATP is released from the cells. In experiments with cell-free filters, it is quite difficult to avoid bulk flow and solvent drag, particularly when stirring the solution. Moreover in experiments with cell-free filters, Δ[ATP] remains constant, whereas the amount of ATP in the layer adjacent to the cells is quite small and could rapidly decrease even with limited diffusion. An estimate of the time constant for ATP washout from the basolateral membrane surface can be obtained from the decay of RATP after replacing hypo- by isosmotic solutions (Fig. 5A). Figure 5B illustrates experiments where we recorded RATP with a higher time resolution. From these data, it is clear that within 2 min RATP dropped to 32 % of its value recorded at the end of the hyposmotic period. This rather rapid reduction of RATP was followed by a slow decay with a time constant of 10.6 min. The biphasic decrease of RATP suggests the involvement of two processes. It is conceivable that the first one is related to the washout of ATP near the basolateral membrane through the filter, a process that occurs relatively fast, and that the second component reflects the washout of ATP capture in the filter matrix, showing a slow time course. Within this concept, integration of the exponential function fitted to the data points collected in isosmotic conditions (Fig. 5B) shows that the amount of ATP trapped in the filter was approximately 1.16 pmol. The amount of ATP washout during the initial rapid decay is estimated at 0.4 pmol. This interpretation of the data assumes that ATP release suddenly drops to zero when switching to isosmotic conditions.

To explore the relationship between Ca2+ liberation from the intracellular stores and the peak in ATP release we investigated the changes in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) caused by (1) different degrees of hyposmolality and (2) by the application of exogenous ATP at different concentrations to the basolateral border.

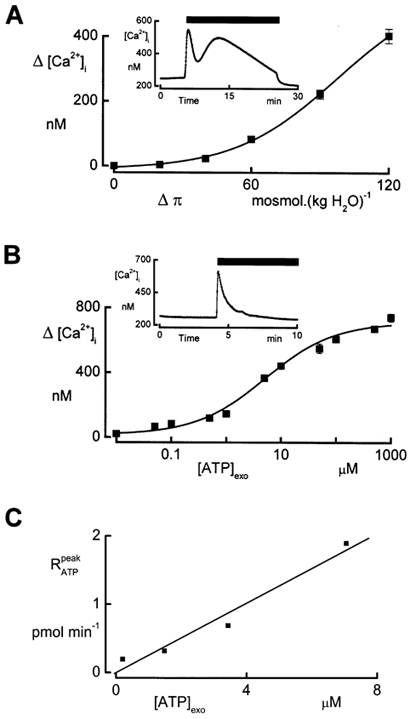

Relation between RATPpeak and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores

Previously (Jans et al. 2002), we observed that a hypotonic shock elicited a biphasic increase in [Ca2+]i. The first phase, caused by release of Ca2+ from intracellular pools, was inhibited in the presence of the P2 receptor antagonist suramin in the basolateral bath. This was indicative of an autocrine effect induced by ATP. To correlate the changes in [Ca2+]i during hypotonicity with the ATP release, we recorded the [Ca2+]i rise: (1) in response to varying degrees of hypotonicity and (2) upon exposure to increasing concentrations of exogenous ATP ([ATP]exo) in the basolateral bath. Figure 6A illustrates the effects of different strengths of hypotonicity on the peak value of the first phase of the [Ca2+]i changes (Δ[Ca2+]i). Δ[Ca2+]i increased gradually and a reduction of the osmolality (Δπ) by 120 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 elevated [Ca2+]i by 403 ± 22 nm. In our previous study (Jans et al. 2002), we reported that A6 epithelia do not show capacitative Ca2+ entry after ATP application, which impedes filling of the stores. Therefore, for each concentration of ATP we performed the [Ca2+]i measurements in response to [ATP]exo in separate experiments. Exposure to extracellular ATP caused [Ca2+]i transients that saturated at 1 mm as illustrated in Fig. 6B. From this figure we determined [ATP]exo + 7.1 μm to obtain Δ[Ca2+]i of 403 nm as recorded in response to an osmotic shock of 120 mosmol (kg H2O)−1. Comparison of the exogenous ATP concentrations with ATP release from the cell is quite tricky.

Figure 6. Changes in [Ca2+]i caused by different degrees of osmotic dilution and exogenous ATP.

A, measurement of [Ca2+]i changes caused by a sudden reduction of the osmolality (Δπ). During the entire experiment, apical osmolality was hyposmotic, i. e. equal to the osmolality of the basolateral solution during the hyposmotic shock. Peak values of [Ca2+]i (Δ[Ca2+]i) recorded during the first transient phase associated with the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores were recorded at different Δπ values. Averaged values ± s.e.m. were calculated from three experiments. The inset demonstrates the time course of [Ca2+]i during an osmotic shock of Δπ + 120 mosmol (kg H2O)−1. The solid bar indicates the duration of the osmotic shock. B, measurement of [Ca2+]i changes caused by adding ATP to the basolateral bath. Cells were incubated in isosmotic solutions and ATP was added to the basolateral perfusate. Exogenous ATP concentrations ([ATP]exo), ranging from 0.01 to 1000 μm, were tested in different tissues. The inset illustrates a typical experiment demonstrating the time course of [Ca2+]i caused by ATP stimulation. The solid bar marks the presence of ATP. Means ± s.e.m. were calculated from three experiments. C, relationship between the peak value of ATP release () during a hyposmotic shock and the exogenous concentration of ATP ([ATP]exo) needed to reach the same increase in [Ca2+]i as in response to the specified hyposmotic shock. Values of Δ[Ca2+]i at 140, 155, 170 and 200 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 were obtained from the data in (A). The values for [ATP]exo represent the exogenous concentration of ATP that was needed to obtain the same increase of [Ca2+]i as obtained during an hyposmotic shock and could be deduced by interpolation of the data in B. values were obtained from Table 3.

In A6 epithelia, most of the ATP release at the basolateral border plausibly occurs through the lateral membranes and may temporarily accumulate in the LIS. Estimation of local ATP concentration in this region ([ATP]LIS) is difficult to make and depends on the size of this compartment as well as on DFIL. We made a rough estimation of the rise in ATP concentration in the LIS during an hyposmotic shock of 120 mosmol (kg H2O)−1. Because (1) the release of Ca2+ from the stores is caused by the activation of purinergic receptors (Jans et al. 2002) and (2) the rapid increase in intracellular Ca2+ reaches its maximum 45 s after initiation of the hyposmotic shock, we assume that most of the ATP required to stimulate the purinergic receptors is liberated from the cells before [Ca2+]i reaches its peak value. We determined this amount of ATP with the assumption that it is released in the basolateral compartment during the peak phase of the RATP record in Fig. 5. The amount of ATP thus calculated by integration of the RATP levels during this peak phase after subtracting the steady state plateau values approximated 9.9 pmol. As the lateral membrane constitutes roughly 80 % of the total basolateral membrane surface, the ATP amount released in the LIS is 7.9 pmol. [ATP]LIS was calculated as 48 μm with the assumption that, as in MDCK cells, the LIS size is about 5.5 % of the cell volume (Kovbasnjuk et al. 1998) or 0.165 μl. [ATP]LIS thus calculated is probably an overestimation because it does not take into account ATP diffusion out of the LIS. This may cause part of the difference between [ATP]LIS and [ATP]exo that was required to elicit a similar rise in [Ca2+]i. However, it is important to note that we found a linear relationship between the peak in and [ATP]exo that is needed to elevate [Ca2+]i to the level recorded during the hyposmotic shock, as depicted in Fig. 6C. Considering these issues, the findings are consistent with the notion that the release of Ca2+ from intracellular Ca2+ pools is caused by an autocrine action of ATP release mediated by purinergic receptors.

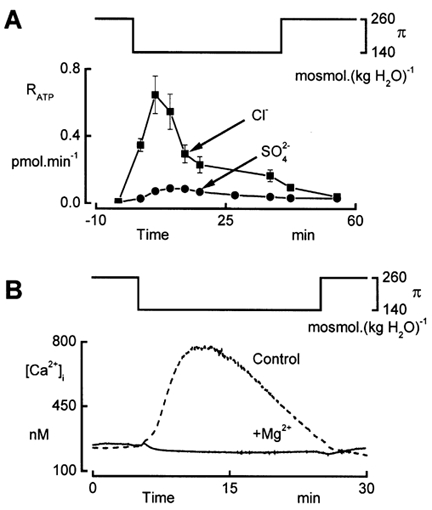

Inhibition of RATP and Δ[Ca2+]i

To further explore the relationship between and the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, we depressed ATP release and monitored Δ[Ca2+]i in parallel experiments. We found that replacing Cl− in the perfusates by SO42- markedly reduced ATP release (Fig. 7A). In these experiments, as well as in a control series with Cl−-containing solutions, we lowered the osmolality by sucrose removal. With SO42- solutions, a sudden decrease of the basolateral osmolality from 260 to 140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 merely increased RATP to a peak level of 0.088 ± 0.005 pmol min−1 as compared to + 0.647 ± 0.112 pmol min−1 in the presence of Cl−. Comparison of this value with the data obtained with NaCl removal (Table 3) shows that sucrose as such had an inhibitory effect on RATP. Nevertheless, substitution of SO42- for Cl− caused a significant reduction of RATP. Measurements of the changes in [Ca2+]i in the absence of Cl− demonstrated that the first phase of Δ[Ca2+]i in response to the hypotonic shock was completely depressed (Fig. 7B). However, the second phase, caused by Ca2+ influx, was unaffected in the experiments with SO42-. The addition of 2 mm Mg2+ to the basolateral bath suppressed this second phase of Δ[Ca2+]i.

Figure 7. Removal of extracellular Cl− depresses RATP and the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores during hypotonic shock.

Effect of SO42- for Cl−substitution in the apical and basolateral perfusates. In this series of experiments, the reduction of osmolality (π) from 260 to 140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 was performed by sucrose removal. A, time courses of RATP recorded during hypotonic shock with Cl− and SO42- solutions. Data are means of five experiments. B, intracellular Ca2+ concentration recorded in the absence (Control) and presence (+Mg2+) of 2 mm Mg2+ in the basolateral perfusate. Experiments were performed with SO42- solutions.

Chelating effects of SO42- on Ca2+ cause a reduction of the free Ca2+ concentration in Cl−-free, sulphate solutions. This reduction of extracellular Ca2+ activity may cause the depression of both ATP release and [Ca2+]i peak during the hypotonic shock in Cl−-free solutions. Therefore, we performed measurements of ATP release in Cl−-containing solutions in which the nominal Ca2+ concentration was 100 μm. A further reduction of nominal Ca2+ concentration dramatically increases transepithelial conductance (unpublished observations), which may falsify the ATP recordings because of leaks across the monolayer. As the transepithelial resistance remains very high in SO42- solutions, it is reasonable to assume that the substitution of SO42- for Cl− does not reduce Ca2+ activity to levels below those obtained with 100 μm nominal Ca2+ in Cl−-containing solutions. ATP release evoked by hypotonicity was not affected by the reduction of nominal Ca2+ concentration. Furthermore, we previously showed that complete removal of Ca2+ did not affect the first phase of the rise in [Ca2+]i during the hypotonic shock (Jans et al. 2002). Therefore, the above data clearly demonstrate that the inhibition of RATP blocks the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores.

Steady ATP release in hyposmotic conditions

The plateau phase of ATP release during exposure to hypotonic solutions (Fig. 5) shows that the release of ATP does not decrease noticeably with time. We performed additional experiments where we exposed the cells to hypotonic solutions for 120 min and recorded ATP release with the pulse protocol every 30 min (Fig. 8A). The data demonstrate that, even during this extended exposure to hypotonic conditions, RATP remained at levels clearly above basal values. Since cell volume regulation is complete within 20 min (De Smet et al. 1995), it appears that the enhanced steady ATP release is not related to an increase in cell volume. This was verified in experiments in which cells were exposed to gradual dilution such that the change in cell volume was negligible as demonstrated before (Van Driessche et al. 1997). In these experiments, we gradually decreased the osmolality from 260 to 140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 at a rate of 1 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 Subsequently, we maintained the basolateral perfusate at constant osmolality (140 mosmol (kg H2O)−1) and recorded RATP with three LL pulses. It is clear from Fig. 8B that after gradual dilution, RATP was significantly larger than isosmotic values. This observation suggests that the steady release of ATP is unrelated to cell swelling. It should be noted that exposure times to diluted solutions in the stepwise and gradual dilution experiments were comparable. It should also be pointed out that while exposing cells to hyposmotic solutions, either in a gradual or in a stepwise way, cells lose KCl (Van Driessche et al. 1997). Therefore, it is conceivable that the steady component of ATP release is related to a decrease in intracellular ionic strength.

Figure 8. Steady ATP release during long term exposure to hyposmotic conditions.

A, recording of RATP during a hyposmotic shock of 120 min duration. Every 30 min we recorded RATP with the pulse protocol as illustrated in Fig. 4 (n = 4). B, recording of RATP while cells were in hyposmotic solutions, conditions achieved by gradual reduction of the osmolality (π) at a rate of 1 mosmol (kg H2O)−1. Data points are means ± s.e.m. (n = 4).

Discussion

The present study attempts to correlate the suramin-sensitive [Ca2+]i increase during hypotonicity to swelling-induced ATP release. Cell swelling has been reported to result in ATP release in a variety of cell types (Taylor et al. 1998; Light et al. 1999; Oike et al. 2000; Mitchell, 2001). In this study, we demonstrate for the A6 renal epithelium some additional characteristics concerning ATP release: (1) hypotonicity causes a biphasic release of ATP across the basolateral membrane consisting of a transient phase, characterized by , and a steady, long term ATP increase, quantified as , (2) the transient phase occurs in parallel with cell swelling and correlates with the concentration of ATP required to elicit a comparable rise in [Ca2+]i as recorded during the hyposmotic shock and (3) the plateau phase of the ATP release is not related to cell swelling but may be caused by the decrease of intracellular ionic strength.

To measure ATP release from polarized epithelial cells, we designed a setup that enables the measurement of the rate of ATP release (RATP) by the A6 epithelium across the basolateral membrane. With the novel protocol, we could record the time course of the ATP release. The setup shown in Fig. 1 uses a photon-counting head with a broad dynamic range, enabling the detection of amounts of ATP extending from 0.1 pmol to 25 nmol with 50 μl ml−1 LL reagent mixture. An important advantage of this setup is the availability of continuous perfusion of the polarized monolayer, allowing a fast replacement of solutions at each border. Moreover, removal of the filter from the culture cup is not necessary, thus avoiding cell damage at the edges.

A direct correlation between ATP release and the suramin-sensitive increase in [Ca2+]i during hypotonicity is confounded by the time lag between the [Ca2+]i peak (which occurs at 45 s after the initiation of the hyposmotic shock) and (peak at 6 min). This is probably due to the delay of ATP diffusion into the bulk fluid. We suggest that the accumulation of ATP in the basolateral solution is hampered because of: (1) the unstirred layer effect, (2) closure of the lateral intercellular spaces (LIS) and (3) degradation of released ATP by ectonucleotidases. To minimize undetectable ATP amassment in the unstirred fluid layer contacting the cells, and to improve diffusion of released ATP through the permeable filter support, we inserted a magnetic stirrer in the basolateral solution. The turbulence in the basolateral compartment caused by the mixing was found not to enhance ATP release during isosmotic conditions. Likewise, solution flow change at the basolateral border did not activate ATP release. Furthermore, ATP release was enhanced when the osmolality of the basolateral solution was reduced. In contrast, decreasing the osmolality of the apical solution did not stimulate ATP release across the basolateral border. Although mixing enhances ATP diffusion into the basolateral compartment, entrapment of ATP in the LIS is still likely. In a previous study, we described a rapid transient closure of the LIS during cell swelling (Van Driessche et al. 1999). It is conceivable that this process severely impedes the washout of ATP near the lateral borders thereby temporarily concentrating ATP in the LIS domain. A delay in the diffusion of ATP into the basolateral compartment may decrease the amount of detectable ATP because of ATP degradation by ecto-ATPases. Since closure of the LIS takes place within 20 s of initiation of the hyposmotic shock, it is reasonable to assume that ATP accumulates to sufficiently high levels that are required for activation of purinergic receptors in the lateral membranes of the cells. On the other hand, the slow reopening of the LIS, 3 min after inducing the hyposmotic shock, may explain the delay for . The role of ATP release through the lateral membranes is supported by the fact that ATP can be released through connexin hemichannels as described in astrocytes (Stout et al. 2002). Although we have no indication for the expression of functional gap junctional hemichannels in cultured A6 epithelia, it is conceivable that ATP is released through this pathway. If hemichannels are expressed, it is reasonable to suppose that their localization is at the lateral membrane (Vanoye et al. 1999). In any case, it may be noted that the lateral membranes account for approximately 80 % of the total basolateral membrane surface area (Van Driessche et al. 1999) and therefore, it is likely that most of the release takes place into the LIS, introducing an important diffusion barrier.

In order to correlate ATP release with the dynamics of [Ca2+]i elevation in response to hyposmotic shocks, we carried out independent measurements of [Ca2+]i changes in relation to different strengths of hyposmotic shock and to increasing concentrations of exogenous ATP. The data allowed us to estimate the concentration of ATP that is required to mimic the rise of [Ca2+]i for a hyposmotic shock with a specific strength. Interestingly, we found a linear correlation between [ATP]exo and the peak values of . Therefore, these data are consistent with ATP release in response to cell swelling as mediator for the elevation of [Ca2+]i during the hyposmotic shock via purinergic receptor activation. A more direct indication that links basolateral ATP release during the hypotonic shock to the suramin-sensitive increase in [Ca2+]i comes from the experiments in Cl−-free solutions. The removal of Cl− from the perfusates suppresses both RATP and Δ[Ca2+]i during the hypotonic shock. The small RATP values that remain in Cl−-free solutions seem to be below the threshold for activating basolateral P2Y receptors. On the other hand, in the presence of Cl−, the reduced levels of RATP that are observed upon sucrose removal are still sufficient to elicit a rise in [Ca2+]i during the hypotonic shock (Jans et al. 2002).

We observed a striking difference between the RATP values recorded upon NaCl removal versus taking away sucrose. Although the Cl− concentration in the hypotonic solution was the same in both types of experiments, the values were markedly smaller during sucrose removal. This observation is consistent with the attenuated release of Ca2+ from the intracellular stores, as previously reported (Jans et al. 2002). At the moment, it is not clear whether this effect is due to a change in extracellular or intracellular Cl− concentration. Recently, a region in the CFTR extracellular domain was proposed to sense the extracellular Cl− concentration as a regulatory mechanism for ATP release through CFTR (Jiang et al. 1998). Although it is tempting to explain our observations with such a mechanism, the experiments in Cl−-free solutions point to the importance of intracellular Cl− as a regulator for ATP release. In these experiments, cells were preincubated with Cl−-free solutions up to 2 h before the experiment. Reducing the Cl−-free incubation period resulted in higher RATP values during the hypotonic shock (data not shown).

The mechanisms underlying the release of ATP in response to increases in cell volume remain poorly understood. According to a number of studies (Wang et al. 1996; Taylor et al. 1998; Light et al. 1999), ATP release is involved in the regulation of cell volume. In this view, it is conceivable that cell swelling leads to ATP release. Although we do not have a direct proof for the participation of ATP in the regulation of cell volume in A6 epithelia, the time course of RATP may suggest such a mechanism. In fact, the regulatory volume decrease correlates well with the first phase in ATP release, both reaching a peak value at 4 min after the initiation of the hyposmotic shock. In this context, we previously observed inhibition of A6 epithelial volume regulation in the presence of 0.5 mm basolateral Gd3+ (Li et al. 1998). Such high concentrations of Gd3+ have been shown to inhibit the release of ATP (Boudreault & Grygorczyk, 2002). On the other hand, to our surprise we found that the release of ATP persisted as long as the cells remained in hyposmotic conditions. Similarly, Koyama et al. (2001) showed a gradual accumulation of ATP for up to at least 30 min into the extracellular space of bovine aortic endothelial cells in response to hypotonic stress. Because A6 cells regulate cell volume within 20 min of hypotonicity, an additional autocrine role for is not readily apparent. Moreover, a steady ATP release at an elevated level comparable to is also recorded after gradual dilution of the extracellular osmolality. A6 cells do not swell during this treatment because of the continuous regulation of cell volume (Van Driessche et al. 1997). On the other hand, both conditions lead to a decrease of the intracellular ionic strength, because of the efflux of KCl. It has been reported that a reduction of the intracellular ionic strength activates the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC) (Cannon et al. 1998). Furthermore, VRAC has been suggested to mediate ATP release in aortic endothelial cells (Hisadome et al. 2002). However, whether VRAC is involved in requires further investigation. In A6 epithelia, hypotonicity results in a permanent activation of ENaC-mediated Na+ reabsorption (Jans et al. 2000). A possible explanation for the persisting outflow of ATP during hyposmotic conditions is to keep the ATP/ADP ratio low in intracellular microdomains close to KATP channels in the basolateral membrane. Their activation is required to drive K+ efflux in response to increased activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase during the hyposmotic shock.

In conclusion, the present study shows that hyposmolality causes a biphasic release of ATP from A6 epithelia. Whereas elevates dose-dependently with the increase of strength of the hyposmotic shock, probably relates to intracellular ionic strength. correlates with the suramin-sensitive phase of the [Ca2+]i rise during the hyposmotic shock (Jans et al. 2002). During diuresis, hypotonicity is a potent physiological stimulant for ATP release across the basolateral membrane of collecting duct epithelia (Taylor et al. 1998). The resulting increase in [Ca2+]i may link to the activation of apical Cl− channels, as suggested by Atia and coworkers (Atia et al. 1999) and contribute to renal Cl−secretion.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by research grants from the ‘Fonds voor wetenschappelijk onderzoek-Vlaanderen’ (G.0179.99), the Interuniversity Poles of Attraction Program-Belgian State, Prime Minister's Office-Federal Office for Scientific, Technical, and Cultural Affairs IUAP P4/23 and S. P. Srinivas is supported by NIH grant EY11107.

References

- Atia F, Zeiske W, Van Driessche W. Secretory apical Cl− channels in A6 cells: possible control by cell Ca2+ and cAMP. Pflügers Archiv. 1999;438:344–353. doi: 10.1007/s004240050919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreault F, Grygorczyk R. Cell swelling-induced ATP release and gadolinium-sensitive channels. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2002;282:C219–226. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00317.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein GM, Roman RM, Clancy JP, Kudlow BA, Taylor AL, Shylonsky VG, Jovov B, Peter K, Jilling T, Ismailov Ii, Benos, D J, Schwiebert, L M, Fitz, J G, Schwiebert EM. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator facilitates ATP release by stimulating a separate ATP release channel for autocrine control of cell volume regulation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:6621–6630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Williams M. P2 purinergic receptors: modulation of cell function and therapeutic potential. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2000;295:862–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon CL, Basavappa S, Strange K. Intracellular ionic strength regulates the volume sensitivity of a swelling-activated anion channel. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:C416–422. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet P, Simaels J, Van Driessche W. Regulatory volume decrease in a renal distal tubular cell line (A6). I. Role of K+ and Cl−. Pflügers Archiv. 1995;430:936–944. doi: 10.1007/BF01837407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomi K, Kajiyama N. Oxyluciferin, a luminescence product of firefly luciferase, is enzymatically regenerated into luciferin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:36508–36513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisadome K, Koyama T, Kimura C, Droogmans G, Ito Y, Oike M. Volume-regulated anion channels serve as an auto/paracrine nucleotide release pathway in aortic endothelial cells. Journal of General Physiology. 2002;119:511–520. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans D, De Weer P, Srinivas SP, Lariviere E, Simaels J, Van Driessche W. Mg2+-sensitive non-capacitative basolateral Ca2+ entry secondary to cell swelling in the polarized renal A6 epithelium. Journal of Physiology. 2002;541:91–101. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans D, Simaels J, Cucu D, Zeiske W, Van Driessche W. Effects of extracellular Mg2+ on transepithelial capacitance and Na+ transport in A6 cells under different osmotic conditions. Pflügers Archiv. 2000;439:504–512. doi: 10.1007/s004249900194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Mak D, Devidas S, Schwiebert EM, Bragin A, Zhang Y, Skach WR, Guggino WB, Foskett JK, Engelhardt JF. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-associated ATP release is controlled by a chloride sensor. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;143:645–657. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura C, Koyama T, Oike M, Ito Y. Hypotonic stress-induced NO production in endothelium depends on endogenous ATP. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;274:736–740. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GE, Bodin P, De Groat WC, Burnstock G. ATP is released from guinea pig ureter epithelium on distension. American Journal of Physiology - Renal Physiology. 2002;282:F281–288. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00293.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovbasnjuk O, Leader JP, Weinstein AM, Spring KR. Water does not flow across the tight junctions of MDCK cell epithelium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:6526–6530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T, Oike M, Ito Y. Involvement of Rho-kinase and tyrosine kinase in hypotonic stress-induced ATP release in bovine aortic endothelial cells. Journal of Physiology. 2001;532:759–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0759e.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, De Smet P, Jans D, Simaels J, Van Driessche W. Swelling-activated cation-selective channels in A6 epithelia are permeable to large cations. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:C358–366. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light DB, Capes TL, Gronau RT, Adler MR. Extracellular ATP stimulates volume decrease in Necturus red blood cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:C480–491. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.3.C480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CH. Release of ATP by a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line: potential for autocrine stimulation through subretinal space. Journal of Physiology. 2001;534:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oike M, Kimura C, Koyama T, Yoshikawa M, Ito Y. Hypotonic stress-induced dual Ca2+ responses in bovine aortic endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2000;279:H630–638. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman RM, Feranchak AP, Davison AK, Schwiebert EM, Fitz JG. Evidence for Gd3+ inhibition of membrane ATP permeability and purinergic signaling. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:G1222–1230. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.6.G1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman RM, Lomri N, Braunstein G, Feranchak AP, Simeoni LA, Davison AK, Mechetner E, Schwiebert EM, Fitz JG. Evidence for multidrug resistance-1 P-glycoprotein-dependent regulation of cellular ATP permeability. Journal of Membrane Biology. 2001;183:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanello M, Pani B, Bicego M, D'andrea P. Mechanically induced ATP release from human osteoblastic cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001;289:1275–1281. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabirov RZ, Dutta AK, Okada Y. Volume-dependent ATP-conductive large-conductance anion channel as a pathway for swelling-induced ATP release. Journal of General Physiology. 2001;118:251–266. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.3.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout CE, Costantin JL, Naus CC, Charles AC. Intercellular calcium signaling in astrocytes via ATP release through connexin hemichannels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:10482–10488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AL, Kudlow BA, Marrs KL, Gruenert DC, Guggino WB, Schwiebert EM. Bioluminescence detection of ATP release mechanisms in epithelia. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:C1391–1406. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.5.C1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Wijk T, De Jonge HR, Tilly BC. Osmotic cell swelling-induced ATP release mediates the activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (Erk)-1/2 but not the activation of osmo-sensitive anion channels. Biochemical Journal 343 Pt. 1999;3:579–586. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3430579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Driessche W, De Smet P, Li J, Allen S, Zizi M, Mountian I. Isovolumetric regulation in a distal nephron cell line (A6) American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C1890–1898. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.6.C1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Driessche W, De Vos R, Jans D, Simaels J, De Smet P, Raskin G. Transepithelial capacitance decrease reveals closure of lateral interspace in A6 epithelia. Pflügers Archiv. 1999;437:680–690. doi: 10.1007/s004240050832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanoye CG, Vergara LA, Reuss L. Isolated epithelial cells from amphibian urinary bladder express functional gap junctional hemichannels. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:C279–284. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.1.C279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Roman R, Lidofsky SD, Fitz JG. Autocrine signaling through ATP release represents a novel mechanism for cell volume regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:12020–12025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]