Abstract

Multiple peptide resistance (MprF) virulence factors control cellular permeability to cationic antibiotics by aminoacylating inner membrane lipids. It has been shown previously that one class of MprF can use Lys-tRNALys to modify phosphatidylglycerol (PG), but the mechanism of recognition and possible role of other MprFs are unknown. Here, we used an in vitro reconstituted lipid aminoacylation system to investigate the two phylogenetically distinct MprF paralogs (MprF1 and MprF2) found in the bacterial pathogen Clostridium perfringens. Although both forms of MprF aminoacylate PG, they do so with different amino acids; MprF1 is specific for Ala-tRNAAla, and MprF2 utilizes Lys-tRNALys. This provides a mechanism by which the cell can fine tune the charge of the inner membrane by using the neutral amino acid alanine, potentially providing resistance to a broader range of antibiotics than offered by lysine modification alone. Mutation of tRNAAla and tRNALys had little effect on either MprF activity, indicating that the aminoacyl moiety is the primary determinant for aminoacyl-tRNA recognition. The lack of discrimination of the tRNA is consistent with the role of MprF as a virulence factor, because species-specific differences in tRNA sequence would not present a barrier to horizontal gene transfer. Taken together, our findings reveal how the MprF proteins provide a potent virulence mechanism by which pathogens can readily acquire resistance to chemically diverse antibiotics.

Keywords: alanine, lysine, tRNA

Accurate translation of mRNA is a central facet of gene expression. Proteins are made by pairing mRNA codons with aminoacyl-tRNA on the ribosome, resulting in the synthesis of a polypeptide whose sequence corresponds to that encoded in the respective mRNA. Aminoacylation of tRNAs is catalyzed by the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs), which match cognate amino acid:tRNA pairs from among the vast number of noncognate molecules in the cell (1). The majority of aminoacyl-tRNAs form ternary complexes with GTP and elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) (2) and are subsequently delivered to the ribosomal A site, where they are used in protein synthesis. Several aminoacyl-tRNAs are also used for cellular processes other than translation, including porphyrin biosynthesis and cell wall biosynthesis and remodeling (3–6) (reviewed in ref. 7). In some bacteria, Lys-tRNALys is used both for translation and for addition of lysine to lipids in the cytoplasmic membrane (8, 9). In Staphylococcus aureus, the multiple peptide resistance factor (MprF) (encoded by mprF) is an integral membrane protein that catalyzes transfer of the aminoacyl moiety from Lys-tRNALys to the free distal hydroxyl group of the glycerol moiety of phosphatidylglycerol (PG). Addition of lysine to PG by MprF increases the positive charge of the cytoplasmic membrane, lowering cellular permeability to cationic molecules. The MprF pathway confers S. aureus, with resistance to cationic antibacterial agents such as antibacterial peptides produced by human neutrophils (defensins) and several cationic antibiotics (aminoglycosides, betalactamines and glycopeptides) (10, 11).

Remodeling of the cytoplasmic membrane by MprF constitutes a potent virulence mechanism by which certain pathogens modulate cellular permeability during infection. Orthologs of mprF are found in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and whereas the correspondence with antibiotic resistance has been studied in S. aureus and Listeria monocytogenes, the molecular basis for substrate recognition (amino acid, tRNA, and lipid) remains largely unexplored. In particular, it is unclear how Lys-tRNALys, which normally participates in protein synthesis by tightly binding to EF-Tu, is first sequestered by MprF and then specifically used in preference to other aminoacyl-tRNA species. Some organisms encode several MprF-related proteins with different architectures, such as in most actinomycetes (e.g., mycobacteria) that contain both a freestanding protein and a version fused to a lysyl-tRNA synthetase. The divergent MprF architectures suggest that the three different C-terminal domains could lead to differences in substrate specificity, thereby allowing the transfer of different activated amino acids to membrane substrates. This echoes previous studies showing that Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Clostridium perfringens, both of which encode two distinct MprF-related proteins of unknown function, are able to form ornithyl- and alanyl-PG, in addition to lysyl-PG, by unknown mechanisms (12–14). Here we show that the two MprF homologs of C. perfringens can specifically modify lipids with different amino acids by using canonical aminoacyl-tRNAs as substrates, providing a mechanism by which RNA-dependent remodeling can fine tune membrane permeability.

Results

Molecular Phylogeny of the MprF Family.

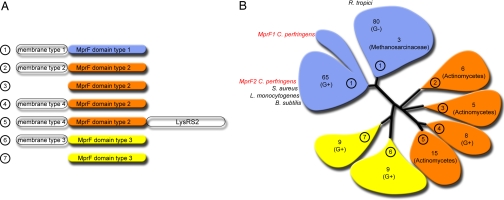

S. aureus MprF is an 840-aa protein composed of two domains, a membrane inserted hydrophobic N-terminal domain predicted to contain 13 transmembrane α-helices and a hydrophilic C-terminal domain oriented toward the cytoplasm. MprF does not share similarity with proteins of known function, and the C-terminal domain was used to search for related sequences from other organisms. A total of 117 sequences of MprF-related proteins were found in Gram-positive bacteria, distributed among 22 different genera. In Gram-negative bacteria, 80 sequences were identified spread among 34 genera. MprF is also present in three archaea from the Methanosarcinaceae. In Gram-positive bacteria, MprF is mostly found in Firmicutes (Bacilli and Clostridia but not in Mollicutes) and in Actinobacteria. In Gram-negative bacteria, MprF is present in proteobacteria but absent from the delta subgroup and is scarcely found in chloroflexi, bacteroides, cyanobacteria, and planctomycetes. Interestingly, MprF is often confined to a particular genus within an order; for example, MprF is present in two genera of gamma proteobacteria but is absent from all enteric bacteria. Three distinct C-terminal domain types were found, either as freestanding proteins or associated with four different types of N-terminal domains (Fig. 1). The largest group of C-terminal domains are all found in MprF from S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, and B. subtilis, for all of which Lys-tRNALys PG transferase activity has been described (8, 9, 15). The second largest group contains MprF sequences from both Gram-positive and negative bacteria, as exemplified by the protein LpiA, which has been shown recently to be responsible for Lys-PG synthesis in Rhizobium tropici (16). Whereas most organisms contain a single mprF gene, C. perfringens encodes MprF proteins belonging to two different subclusters within the same group (Fig. 1). To determine whether the two mprF genes of C. perfringens encode distinct activities, the lipid modification activities of the corresponding proteins were investigated in vivo and in vitro.

Fig. 1.

Architecture and phylogeny of MprF proteins. (A) Architecture of MprF-like proteins showing three types of MprF domains associated to four types of membrane domain. (B) Phylogenic analysis (i.e., the neighbor-joining method with ClustalX 1.83) of 200 MprF domains common to all members of the MprF family. In each of the phylogenetic groups, the number of sequences is indicated. The Gram type or the genus of the bacterial sequences is specified in parenthesis. The architecture of each phylogenetic group (from A) is circled. Organisms for which experimental support of MprF function exists are named, with proteins studied in this work indicated in red.

Lipid Aminoacylation by MprF1 and MprF2.

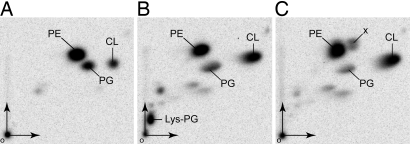

To investigate the potential aminoacyl transferase activities of MprF1 and MprF2 from C. perfringens, the corresponding genes were cloned and the proteins were produced in E. coli C41 (17). Previous studies with B. subtilis MprF have revealed that heterologous expression of the protein in E. coli, which has no MprF-type activity, leads to detectable levels of Lys-PG synthesis in vivo (18). Three strains were constructed that contained either vectors encoding MprF (C41-MprF1 and C41-MprF2) or the corresponding empty vector (C41-pet). To facilitate analysis of membrane phospholipid modifications, strains were grown in LB containing [32P]-pyrophosphate. Lipids were extracted by using the method of Bligh and Dyer (19) and analyzed by 2D TLC to reveal the pattern of E. coli lipid modification catalyzed by each MprF (Fig. 2). The three major membrane phospholipids of E. coli, phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), PG, and cardiolipin (CL), were all detected in the control strain, although additional compounds were also visible when MprF1 or MprF2 were produced (Fig. 2). A compound with the characteristic migration pattern of Lys-PG was detected when MprF2 was produced (Lys-PG; Fig. 2B) and an uncharacterized compound close to PE was visible only upon MprF1 production (Fig. 2C, x). These data indicate that C. perfringens MprF2 has canonical Lys-tRNALys PG transferase activity, whereas MprF1 is unable to make Lys-PG but, instead, synthesizes another modified phospholipid when produced in E. coli.

Fig. 2.

2D TLC analysis of [32P]phospholipids. Extracts from C41-pet (A), C41-MprF2 (B), and C41-MprF1 (C) are shown. [32P]Phospholipids were visualized by phosphorimaging. o, origin; x, unidentified spot specific to the strain C41-MprF1.

MprF1 Is Specific for Ala-tRNA.

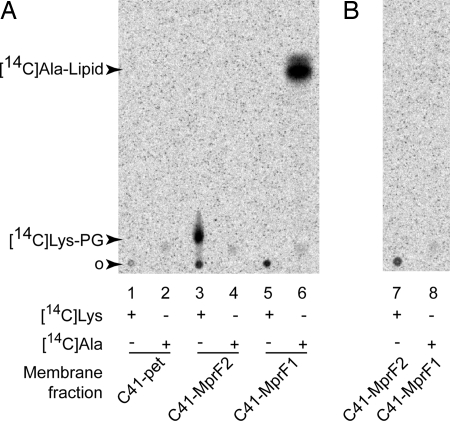

A recent reassessment of the lipid composition of C. perfringens membranes confirmed the presence of both Ala-PG and Lys-PG (14). This prompted us to investigate the ability of MprF1 and MprF2 to use Ala-tRNA and Lys-tRNA as substrates for the aminoacylation of PG. Membrane extracts from the strains C41-MprF1, C41-MprF2, and C41-pet were aminoacylated in vitro in the presence of [14C]-Ala or [14C]-Lys in reaction media containing total tRNA and an S100 extract of E. coli containing lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS) and alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AlaRS) activities. After incubation, the lipids were extracted from the reaction and analyzed by TLC (Fig. 3A). The membrane extract from the strain C41-pet was unable to attach [14C]-Ala or [14C]-Lys to lipid, whereas the preparations from C41-MprF1 and C41-MprF2 exhibited lipid aminoacylation activities specific for Ala and Lys, respectively. To confirm that the observed aminoacyl transferase activities were both tRNA dependent as with other characterized MprF proteins, lipid modification was monitored in the presence of RNase A (Fig. 3B). Addition of RNase A completely inhibited the lipid aminoacyl transferase activities of both enzymes, indicating that they are tRNA-dependent.

Fig. 3.

Lipid acylation activity in membrane fractions. Membrane fractions were incubated for 10 min at 37°C in 1× buffer A with 8 mM ATP and 0.5 mg/ml S100 extract from E. coli and in the presence (+) or absence (-) of [14C]Lys or [14C]Ala. Total tRNA (2 mg/ml) from E. coli (A) or 0.3 mg/ml RNase A (B) were added. The reaction medium was analyzed by TLC in 1D, and the [14C]aminoacyl lipids were visualized by phosphorimaging. The greater intensity of the Ala-PG species results from the higher specific activity of MprF1 in membrane fractions used here. o, origin.

MprF1 Catalyzes Ala-PG Synthesis.

To determine the phospholipid substrate of MprF1, an in vitro reconstituted minimal system was used in which alanyl-transferase activity was tested by measuring lipid acylation by [14C]-Ala by using catalytic amounts of the corresponding membrane extract in the presence of purified AlaRS and in vitro-transcribed tRNAAla from E. coli. The lipid alanylation activity of C41-MprF1 membrane extracts was compared in the presence or absence of an excess of egg yolk PG (Fig. 4). A higher level of lipid alanylation was observed when the reaction medium was supplemented with PG compared with that obtained without additional PG (Fig. 4B), consistent with similar studies in which exogenous PG is used to demonstrate lysyl-transferase activity in MprF2-type enzymes (18). It is also worth noting that the lipid extraction method used here eliminated all free [14C]-Ala (Fig. 4A) and [14C]-Lys (18), thereby allowing PG acylation by radiolabeled amino acids to be quantified by scintillation counting of extracted lipids without recourse to TLC analysis.

Fig. 4.

Lipid alanylation activity in membrane fraction of C41-MprF1. (A) The reaction was performed in 1× buffer A with a catalytic amount of membrane fraction (0.035 mg/ml), 8 mM ATP, 5 μM tRNAAla transcript, and 2 μM AlaRS and in the absence (-PG) or presence of 2 mg/ml PG (+PG). After various incubation times, lipids were extracted and analyzed by TLC and alanylated lipids were revealed by phosphorimaging. (B) Lipid alanylation levels determined by quantification of the spots obtained in A. (C) Migration of Ala-PG in a 2D TLC system. Total cold lipids from C41-MprF1 were comigrated with [14C]Ala-PG obtained from Fig. 3, lane 6. Total lipids were revealed by iodine vapors (Left) and [14C]Ala-PG by phosphorimaging (Right).

To further characterize the products of PG alanylation by MprF1, a 2D TLC system was used. An unlabeled lipid preparation from strain C41-MprF1 was co-migrated with [14C]-Ala-PG obtained previously without addition of exogenous PG (Fig. 3, lane 6). Total cold lipids from C41-MprF1 were visualized by using iodine vapors, and [14C]-Ala-PG detected by phosphorimaging. Interestingly, Ala-PG resolved into two spots: the major species superposed with PE and the minor species migrated slightly faster in the second dimension (Fig. 4C). These two species may correspond to two distinct products of the reaction, such as bis-acylation of PG or acylation of an alternate position of the PG glycerol group.

The Aminoacyl Moiety Is the Primary Determinant for Aminoacyl-tRNA Recognition by MprF.

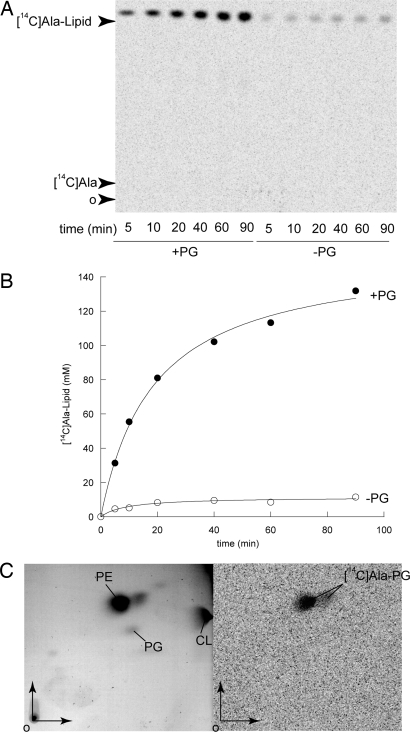

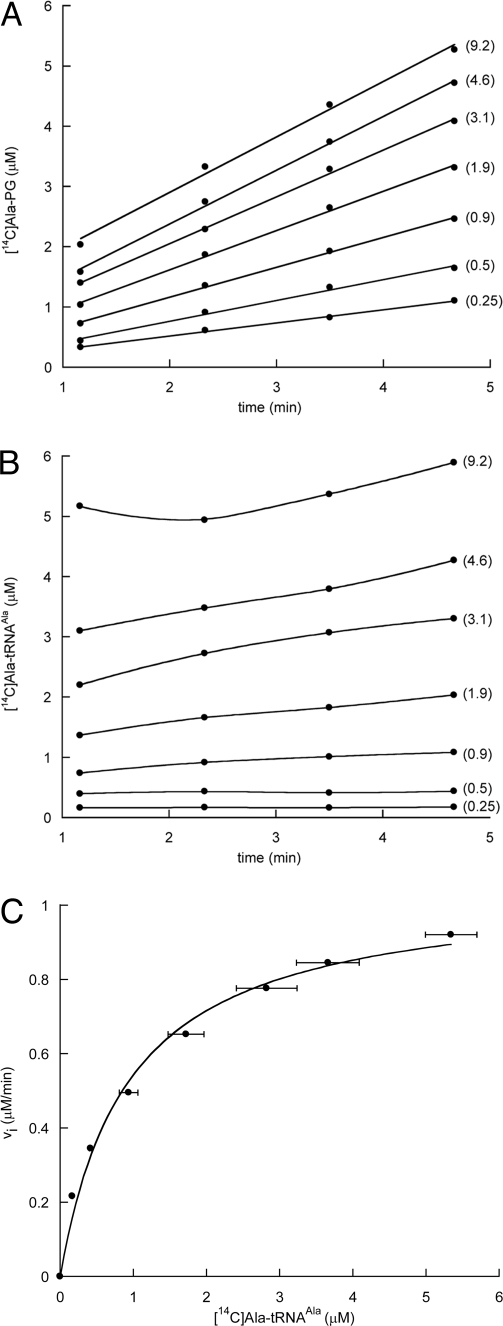

We next determined the importance of the tRNA body for recognition by C. perfringens MprF1 and MprF2. For this purpose, in vitro-transcribed tRNAAla and AlaRS from E. coli and in vitro-transcribed tRNALys and LysRS from either human or Borrelia burgdorferi were used in an in vitro aminoacyl transferase assay (18). tRNALys transcripts from other systems such as E. coli (20) and B. subtilis (21) show minimal activity in vitro and are not suitable for assays of MprF activity. To continuously monitor activity, an excess of AlaRS or LysRS was used to maintain a steady level of aminoacyl-tRNA in the reaction media, allowing the determination of the aminoacylation level of tRNA and PG simultaneously during the time course of the reaction. Steady-state kinetic parameters were determined for aminoacyl-PG formation over a range of different aminoacyl-tRNA concentrations (Fig. 5 and Table 1). tRNAAla, tRNAPro containing AlaRS recognition elements (22) and an Ala-specific mini helix [a hairpin composed of only the acceptor and T stems of tRNAAla (23)] were all efficiently recognized by MprF1. Similarly, tRNALys from B. burgdorferi and Homo sapiens, which share less than 50% identity, are also recognized equally well by MprF2 (Table 1). These findings indicate that the overall sequence of the tRNA moiety of the aminoacyl-tRNA is not a critical determinant of substrate specificity for MprF1 or MprF2. Furthermore, both the anticodon and the overall L shape of the tRNA are dispensable for recognition by MprF1 because the Ala minihelix was recognized as efficiently as tRNAAla. The nature of the sequence of the tRNA body is also not important because tRNAPro UGC and human tRNALys-3, which contains a different discriminator base (G73) than eubacterial tRNALys (A73), are efficient substrates for MprF1 and MprF2, respectively. Overall, these data indicate that the main determinant of the specificity of aminoacyl-tRNA recognition by MprF1 and MprF2 is the identity of the aminoacyl moiety of the substrate.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of PG alanylation kinetics. (A) Formation of [14C]Ala-PG. (B) Alanylation level of tRNAAla. Both alanylated species were determined simultaneously in the presence of varying amounts of tRNA (indicated in brackets). (C) Fitting of the Michaelis–Menten curve to the initial velocities (vi) plotted as a function of the determined concentration of [14C]Ala-tRNAAla.

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for aminoacyl-PG formation by MprF1 and MprF2 from C. perfringens

| tRNA | Km, μM | Vm, μM/min | Vm/Km, min−1 μM−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| MprF1 | |||

| tRNAAla (E. coli) | 0.97 ± 0.02 | 1.39 ± 0.25 | 1.42 ± 0.23 |

| tRNAPro UGC (C1G, G72C, C72U E. coli) | 1.06 ± 0.08 | 0.88 ± 0.3 | 0.83 ± 0.10 |

| Minihelix Ala (E. coli) | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 1.12 ± 0.25 |

| MprF2 | |||

| tRNALys (B. burgdorferi) | 3.15 ± 0.62 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.27 ± 0.03 |

| tRNALys3 (H. sapiens) | 4.42 ± 1.29 | 0.50 ± 0.10 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| tRNAAsp UUU (A3G, U70C, C71U, G73A E. coli) | +* |

*+, substrate for Lys-PG synthesis, but product levels were too low to allow determination of kinetic parameters.

Aminoacyl-tRNAs Bound to EF-Tu Are Kinetically Accessible to MprF.

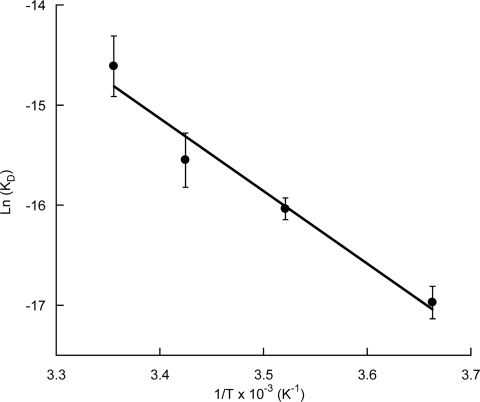

Aminoacyl-tRNAs are delivered to the ribosomal A site as ternary complexes with EF-Tu and GTP. EF-Tu is one of the most abundant proteins in bacterial cells (24) and binds aminoacyl-tRNAs with high affinity (25), raising the question as to how Ala-tRNAAla and Lys-tRNALys are directed away from translation to the MprF pathway. To investigate how effectively an aminoacyl-tRNA can “escape” the protein biosynthesis machinery, we first determined the koff for Lys-tRNALys from the ternary complex with EF-Tu·GTP and derived the corresponding dissociation constant (KD) at 4°C, as previously described (26, 27). The KD for Lys-tRNALys was 43 ± 7 nM, an affinity two orders of magnitude higher than the KM measured for MprF2 with the same substrate at 37°C. In an attempt to compare the affinities of EF-Tu and MprF2 for Lys-tRNALys under more physiological conditions, the effect of temperature on koff for the ternary complex was investigated. koff increased 10-fold upon changing the temperature from 4°C to 25°C (the practical upper limit for this particular system). koff values determined over this temperature range were used to derive the corresponding KD values, and a linear van't Hoff plot was then used to estimate KD values at higher temperatures (Fig. 6). Based on this analysis, the KD of the complex would reach 950 nM at 37°C, a value 20-fold higher than that observed at 4°C and in agreement with the 30-fold increase observed over the same temperature range for the EF-Tu· Phe-tRNAPhe interaction (28). These data suggest that EF-Tu and the MprFs would have similar affinities for aminoacyl-tRNA under physiological conditions, allowing for effective partitioning of substrate between the two corresponding pathways.

Fig. 6.

Lys-tRNALys dissociation kinetics. van't Hoff plot between 0 and 25°C of the dissociation constant (KD) for the complex EF-Tu·Lys-tRNALys.

Discussion

MprFs Can Remodel Inner Membrane Lipids with Ala and Lys.

Bacteria modulate their permeability to charged molecules through modifications that reduce the net negative charge of the membrane, such as attachment of d-Ala to teichoic acid (2), acylation of the lipopolysaccharide with positively charged molecules, biosynthesis of PE (3), and lysylation of PG (4). Lysylation of PG by MprF has been described in several organisms and has recently been implicated as a key factor in determining the virulence of methicillin resistant S. aureus, which is particularly refractory to antibiotic therapy (11). The net effect of lysylation is to make PG positively charged, thereby conferring resistance to cationic antimicrobial compounds such as defensins and increasing tolerance to acidic growth conditions. The discovery that members of the MprF family can also specifically modify PG with the neutral amino acid alanine reveals a mechanism whereby the charge of the inner membrane can be fine tuned in response to different environmental challenges. Based on comparative genomic analyses (Fig. 1), the ability to modify PG with both Ala and Lys is not universal, suggesting either that certain organisms use other pathways to neutralize the inner membrane or that Ala-PG is only required under particular physiological conditions. An understanding of how mprF1 and mprF2 expression is regulated in response to different environmental cues is now needed to better appreciate the physiological consequences of Ala and Lys modification of PG. The structural diversity of the MprF family suggests that amino acids other than Ala and Lys may also be substrates for PG modification. For example, ornithine-PG has been described in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (13), and it is possible that under certain conditions tRNALys mischarged with ornithine (29) may serve as a substrate for MprF. The possible use of still other amino acids to modify the chemical and physical properties of the inner membrane can now be explored in more detail by using the phylogenetic distribution of the various MprF subtypes as a starting point.

Relaxed RNA Specificity Facilitates Horizontal Transfer of MprF.

The potency of MprF as a virulence factor derives from its ability to sequester resources from a ubiquitous cellular process, protein synthesis, for cellular adaptation to adverse conditions. Beyond contributing to pathogenicity, another feature of many virulence factors associated with antibiotic resistance is the ease with which they can be transferred between different hosts. In the case of MprF, horizontal transfer of the corresponding activity requires insertion of a substantial portion of the protein into the host membrane and facile recognition of heterologous lipid and aminoacyl-tRNA substrates. The C. perfringens MprF1 and MprF2 activities could both be reconstituted in E. coli despite differences between the Gram-positive and Gram-negative cell envelopes and the sequences of the corresponding tRNAs. Sequence differences often present a barrier to the horizontal transfer of tRNA-dependent pathways and are believed to be a significant factor in the distribution of the known pretranslational modification pathways (e.g., ref. 30). In contrast both MprF1 and MprF2 showed relaxed specificity toward the tRNA moiety of their aminoacyl-tRNA substrates, providing a mechanistic basis for their potency as mobile virulence factors.

The Role of tRNA as an Adaptor Outside of Translation.

Several noncanonical aminoacyl-tRNAs are able to evade the translation elongation machinery and are used instead for other tRNA-dependent biosynthetic processes. This is achieved by discriminating against EF-Tu binding, as described for misacylated Asp-tRNAAsn and Glu-tRNAGln (31, 32), Met-tRNAfMet initiator species (33), and Ser/Sec-tRNASec from the selenocysteine insertion pathway (34). In all of these examples, discrimination against EF-Tu binding both frees up aminoacyl-tRNA for other cellular process and prevents miscoding errors during translation (2). It has been less clear whether other enzymes such as LF-transferase (35) and MprF use canonical aminoacyl-tRNA species in competition with EF-Tu or, instead, rely on idiosyncratic features of particular tRNAs, as described for peptidoglycan biosynthesis in Staphylococcus epidermidis (4). Our data indicate that, contrary to initial expectations, EF-Tu·GTP·aminoacyl-tRNA complexes provide a pool of aminoacyl-tRNA both for translation and other cellular processes. This expanded role for EF-Tu in metabolism is also based on its ability to protect the labile aminoacyl-ester linkage (36), thereby providing the cell with a stabilized pool of activated amino acids.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids.

The genes mprf1 and mprf2 from C. perfringens SM101 (GenBank accession numbers YP_698880 and YP_698580, respectively) were amplified by PCR by using genomic DNA from Sigma (D1760) with the primers 5′-ATATACCATGGGTTGGGATTCACTAAAAAAAAGTTATAGACATT-3′, 5′-CGCGGATCCTTATTTTTTCTCTACTCTTTCCTTTGAATTAGCTATTAATA-3′ and 5′-ATATATCCATGGTGAAGTTAAATATAAAGATAAGTGAC A A A T T A A A ATTATT-3′, 5′-ACGCGTGGATCCTTATTTAATTAAGCTTTTTAAGTTTCTT A C A ACTATACTTTC-3′, respectively. The PCR products were cloned into the vector pet33b (kanR, Novagen) by using the NcoI and BamHI restriction sites. Empty and recombinant vectors were used to transform the E. coli strain C41 (17), which also contained the plasmid pRARE2 (CamR, Novagen) encoding tRNAs for translation of rare codons to yield the strains C41-MprF1, C41-MprF2, and C41-pet. Expression of protein was carried out in an autoinduction medium, described elsewhere (18), containing 30 mg/L chloramphenicol and 50 mg/L kanamycin. E. coli His6-EF-Tu was produced and purified as described previously (37).

In Vivo Labeling of Bacterial Strains with [32P]-Pyrophosphate and Lipid Analysis.

Lipids were extracted from samples by using the method of Bligh and Dyer (19) with 120 mM potassium acetate, pH 4.5, in the aqueous phase. TLC analysis of lipids was carried out on HLF silica gel 250-micron plates (Analtech) developed in 1D or 2D by using successively the solvents chloroform:methanol:water (14:6:1, vol:vol:vol) in the first dimension and chloroform:methanol:acetic acid (13:5:2, vol:vol:vol) in the second dimension. In vivo labeling of phospholipids was performed by inoculating 2 ml of LB containing antibiotics (see above) and 5 × 106 cpm of [32P]-pyrophosphate (Perkin-Elmer) with 20 μl of an overnight culture. Protein production was induced by addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside after incubation for 4 h at 37°C with shaking, and the cells were harvested after 5 h of additional incubation at 37°C under agitation. PG and CL were identified by comigration of the radiolabeled lipids with commercially available PG (P0514; Sigma) and CL (C1649; Sigma). PE and Lys-PG were also distinguished based on staining with Ninhydrin.

Determination of Kinetic Parameters for MprF.

Membrane suspensions were prepared by differential centrifugation (18) and stored at −80°C in 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM diisopropyl fluorophosphate, 1 mM PMSF, 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 20% glycerol. The concentration of protein in membrane suspension was 15–20 mg/ml, as measured by the method of Bradford (Bio-Rad). The MprF activity in extracts was assayed in a reaction medium reconstituted sequentially in which the amount of [14C]aminoacyl-tRNA is maintained constant and the levels of aminoacyl-tRNA and aminoacyl-PG are simultaneously determined. Liposome suspensions of PG were prepared by vortexing dried PG from egg yolk (P0514; Sigma) for 10 min in 1× buffer A (100 mM HEPES–NaOH, pH 7.2, 15 mM MgCl2, 30 mM KCl). Before use in the PG acylation assay, membrane fractions were added to the PG mixture and preincubated for 15 min at 37°C to yield a solution containing 9 mg/ml PG and 0.18 or 0.48 mg/ml protein of the C41-MprF1 or C41-MprF2 membrane suspensions, respectively. Shorter preincubation times resulted in biphasic kinetic plots. Before initiation of the PG acylation reaction, various amounts of [14C]aminoacyl-tRNA were produced by incubation for 5 min at 37°C in 1× buffer A containing 45 μM [14C]Lys or [14C]Ala (GE Bioscience), 4.5 μM E. coli AlaRS or B. burgdorferi LysRS, and 12 mM ATP. The PG acylation reaction was initiated by mixing 30 μl of the preincubated tRNA aminoacylation medium with 15 μl of the membrane suspension preequilibrated in PG. At various intervals, 10 μl of the reaction mixture was added to 500 μl of chloroform:methanol:120 mM potassium acetate (pH 4.5) (4:8:3.2). Chloroform (130 μl) and 120 mM potassium acetate, pH 4.5, were subsequently added to each mixed aliquot. After a 20-s vortexing step and 5 min of centrifugation at room temperature, organic phases containing [14C]aminoacyl-PG were dried and the radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting (Fig. 5). Twenty microliters of 3 M potassium acetate, pH 4.5, was added to the aqueous phase, and [14C]aminoacyl-tRNAs were then precipitated at −80°C after the addition of 1 ml of ethanol. [14C]Aminoacyl-tRNAs were recovered by centrifugation, resuspended in 60 μl of 60 mM potassium acetate, pH 4.5, and spotted on 3-mm filter discs, washed twice in 5% TCA, and dried, and the retained radioactivity was then determined by scintillation counting (Fig. 5). The yield for [14C]aminoacyl-tRNA recovery with this technique was 60–70% when compared with the direct TCA precipitation method. Kinetic parameters for the PG acylation reaction were obtained by plotting the determined aminoacyl-tRNA concentrations versus the corresponding rate of formation of [14C]aminoacyl-PG. Data were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation by nonlinear regression by using the program Kaleidagraph 4.0 (Synergy Software).

koff Determination for the EF-Tu·Lys-tRNALys Complex.

koff values were determined by using the RNase A protection assay as previously described (26) and modified as follows. [14C]Lys-tRNALys was prepared as described (38). EF-Tu (14 μM) from E. coli was activated by incubation for 1 h at 37°C in 50 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.2, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NH4Cl2, 3 mM GTP, 10 mM phosphoenol pyruvate, 0.25 mg/ml pyruvate kinase, and 50 mM KCl. Measurement of protection by EF-Tu of [14C]Lys-tRNALys was initiated by the addition of 50 μg/ml of RNase A to a reaction medium containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NH4Cl2, 1.5 mM GTP, 5 mM phosphoenol pyruvate, 0.12 mg/ml pyruvate kinase, 25 mM KCl, 7.5 μM EF-Tu, and 1.5 μM [14C]Lys-tRNA. Kinetics were measured within 1 min at temperatures ranging from 0°C to 25°C. No detectable [14C]Lys-tRNALys was measured when EF-Tu was omitted. KD values were calculated assuming kon = 1.0 × 105 M−1 s−1 (27), and the KD at 37°C was inferred by fitting the van't Hoff equation [ln(KD) = ΔH°/RT − ΔS°/R] by linear regression to the data (Fig. 6).

Acknowledgments.

We thank B. Kraal (Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands) and K. Musier-Forsyth (Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio) for strains and plasmids. This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant 065183.

Note.

Recent studies in the laboratory of J. Moser (University of Brunswick, Brunswick, Germany) have also described alanyl-tRNA transferase activity for MprF from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (personal communication).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Ataide SF, Ibba M. Small molecules - Big players in the evolution of protein synthesis. ACS Chem Biol. 2006;1:285–297. doi: 10.1021/cb600200k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dale T, Uhlenbeck OC. Amino acid specificity in translation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petit JF, Strominger JL, Söll D. Biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan of bacterial cell walls. VII. Incorporation of serine and glycine into interpeptide bridges in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:757–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart TS, Roberts RJ, Strominger JL. Novel species of tRNA. Nature. 1971;230:36–38. doi: 10.1038/230036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villet R, et al. Idiosyncratic features in tRNAs participating in bacterial cell wall synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6870–6883. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lloyd AJ, et al. Characterization of tRNA-dependent peptide bond formation by MurM in the synthesis of Streptococcus pneumoniae peptidoglycan. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708105200. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibba M, Söll D. Aminoacyl-tRNAs: Setting the limits of the genetic code. Genes Dev. 2004;18:731–738. doi: 10.1101/gad.1187404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peschel A, et al. Staphylococcus aureus resistance to human defensins and evasion of neutrophil killing via the novel virulence factor MprF is based on modification of membrane lipids with l-lysine. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1067–1076. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.9.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thedieck K, et al. The MprF protein is required for lysinylation of phospholipids in listerial membranes and confers resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs) on Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:1325–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weidenmaier C, et al. DltABCD- and MprF-mediated cell envelope modifications of Staphylococcus aureus confer resistance to platelet microbicidal proteins and contribute to virulence in a rabbit endocarditis model. Infect Immun. 2005;73:8033–8038. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8033-8038.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman L, Alder JD, Silverman JA. Genetic changes that correlate with reduced susceptibility to daptomycin in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2137–2145. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00039-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gould RM, Thornton MP, Liepkalns V, Lennarz WJ. Participation of aminoacyl transfer RNA in aminoacyl phosphatidylglycerol synthesis. II. Specificity of alanyl phosphatidylglycerol synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:3096–3104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khuller GK, Subrahmanyam D. On the ornithinyl ester of phosphatidylglycerol of Mycobacterium 607. J Bacteriol. 1970;101:654–656. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.2.654-656.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston NC, Baker JK, Goldfine H. Phospholipids of Clostridium perfringens: A reexamination. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;233:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishibori A, et al. Phosphatidylethanolamine domains and localization of phospholipid synthases in Bacillus subtilis membranes. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2163–2174. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.6.2163-2174.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohlenkamp C, et al. The lipid lysyl-phosphatidylglycerol is present in membranes of Rhizobium tropici CIAT899 and confers increased resistance to polymyxin B under acidic growth conditions. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:1421–1430. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-11-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: Mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy H, Ibba M. Monitoring Lys-tRNALys phosphatidylglycerol transferase activity. Methods. 2008;44:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bligh E, Dyer W. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Commans S, et al. tRNA anticodon recognition and specification within subclass IIb aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:801–813. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ataide SF, Jester BC, Devine KM, Ibba M. Stationary-phase expression and aminoacylation of a transfer-RNA-like small RNA. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:742–747. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong FC, et al. Functional role of the prokaryotic proline-tRNA synthetase insertion domain in amino acid editing. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7108–7115. doi: 10.1021/bi012178j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Francklyn C, Schimmel P. Aminoacylation of RNA minihelices with alanine. Nature. 1989;337:478–481. doi: 10.1038/337478a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neidhardt FC, Bloch PL, Pedersen S, Reeh S. Chemical measurement of steady-state levels of ten aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetases in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1977;129:378–387. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.1.378-387.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asahara H, Uhlenbeck OC. Predicting the binding affinities of misacylated tRNAs for Thermus thermophilus EF-Tu.GTP. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11254–11261. doi: 10.1021/bi050204y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asahara H, Uhlenbeck OC. The tRNA specificity of Thermus thermophilus EF-Tu. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3499–3504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052028599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nazarenko IA, Harrington KM, Uhlenbeck OC. Many of the conserved nucleotides of tRNAPhe are not essential for ternary complex formation and peptide elongation. EMBO J. 1994;13:2464–2471. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vorstenbosch EL, Potapov AP, de Graaf JM, Kraal B. The effect of mutations in EF-Tu on its affinity for tRNA as measured by two novel and independent methods of general applicability. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2000;42:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(99)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levengood J, Ataide SF, Roy H, Ibba M. Divergence in noncognate amino acid recognition between class I and class II lysyl-tRNA synthetases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17707–17714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tumbula DL, Becker HD, Chang WZ, Söll D. Domain-specific recruitment of amide amino acids for protein synthesis. Nature. 2000;407:106–110. doi: 10.1038/35024120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stanzel M, Schön A, Sprinzl M. Discrimination against misacylated tRNA by chloroplast elongation factor Tu. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:435–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becker HD, Kern D. Thermus thermophilus: A link in evolution of the tRNA-dependent amino acid amidation pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12832–12837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stortchevoi A, Varshney U, RajBhandary UL. Common location of determinants in initiator transfer RNAs for initiator-elongator discrimination in bacteria and in eukaryotes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17672–17679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baron C, Böck A. The length of the aminoacyl-acceptor stem of the selenocysteine-specific tRNASec of Escherichia coli is the determinant for binding to elongation factors SELB or Tu. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20375–20379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe K, et al. Protein-based peptide-bond formation by aminoacyl-tRNA protein transferase. Nature. 2007;449:867–871. doi: 10.1038/nature06167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailly M, et al. The transamidosome: A dynamic ribonucleoprotein particle dedicated to prokaryotic tRNA-dependent asparagine biosynthesis. Mol Cell. 2007;28:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boon K, et al. Isolation and functional analysis of histidine-tagged elongation factor Tu. Eur J Biochem. 1992;210:177–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roy H, Ling J, Irnov M, Ibba M. Posttransfer editing in vitro and in vivo by the beta subunit of phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase. EMBO J. 2004;23:4639–4648. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]