Abstract

Cell growth arrest and apoptosis are two best-known biological functions of tumor-suppressor p53. However, genetic evidence indicates that not only is p21 the major mediator of G1 arrest, but also it can prevent apoptosis with an unknown mechanism. Here, we report the discovery of a p53 target gene dubbed killin, which lies in close proximity to pten on human chromosome 10 and encodes a 20-kDa nuclear protein. We show that Killin is not only necessary but also sufficient for p53-induced apoptosis. Genetic and biochemical analysis demonstrates that Killin is a high-affinity DNA-binding protein, which potently inhibits eukaryotic DNA synthesis in vitro and appears to trigger S phase arrest before apoptosis in vivo. The DNA-binding domain essential for DNA synthesis inhibition was mapped to within 42 amino acid residues near the N terminus of Killin. These results support Killin as a missing link between p53 activation and S phase checkpoint control designed to eliminate replicating precancerous cells, should they escape G1 blockade mediated by p21.

Keywords: differential display, pten

p53 is the most frequently mutated, disrupted, and/or allelically lost tumor suppressor gene in human cancer, and it has been a focal point for intensive cancer research (1–3). Functionally, p53 works as a sequence-dependent transcription factor, which, upon activation by genotoxic stresses such as DNA damages, regulates the expression of a set of target genes involved in cell growth control and apoptosis (4–7). In contrast to a large number of p53 target genes implicated in cell apoptosis, activation of cell cycle arrest at G1 by p53 results predominantly from the induction of p21 (8–10), whereas p21 and GADD45 and 14-3-3 proteins were also shown to be involved in G2-M arrest (11). Among the known p53 target genes implicated in apoptosis, a family of Bcl-2 related genes, such as bax, puma, and noxa, are best characterized and thought to work through a mitochondria-dependent death pathway (12).

Through a genetic approach using somatic gene knockout strategy, it was shown that cellular choice between growth arrest and death upon p53 activation appears to depend on at least two factors. For cell types that undergo p53-mediated G1 arrest, elimination of p21 sensitizes cells to die (13, 14). In such cases, p21 clearly plays a protective role in apoptosis. In cell types prone to apoptosis upon p53 activation, transacting death-inducing factors are dominant over p21-mediated protection (13, 14). In the case of p21-mediated G1 arrest, which protects cells from p53-induced apoptosis, one possible explanation could be that the apoptosis-initiating event(s) require cells to enter S phase. Supporting evidence for such S phase-coupled apoptosis includes findings that forced S phase entry by unrestricted E2F activity can trigger the activation of caspases and apoptosis (15, 16). Conceivably, DNA damage can happen to cells at any phase during the cell cycle. The induction of either p21 in cells at G1, or p21 GADD45, and 14-3-3 at G2/M phase by p53, will lead to growth arrest at the respective cell-cycle phases. However, little is known about p53-mediated checkpoint control during S phase, where cells would run the highest risk of incorporating mutations after sustained DNA damage. It is logical that apoptosis would be the best choice for eliminating these cells.

In this study, we describe the identification of a p53 target gene, killin, which encodes a small nuclear DNA-binding protein with a high affinity to both double- and single-stranded DNA. We show that Killin is not only necessary but also sufficient for mediating p53-induced apoptosis. Genetic and biochemical analysis reveals that the DNA-binding domain of Killin resides within 42 amino acid residues near the N terminus of the protein, which can inhibit DNA synthesis in vitro and S phase arrest coupled to apoptosis in vivo. Thus, Killin represents a p53 target gene directly involved in S phase checkpoint control-coupled apoptosis. Our finding also helps explain the apparent paradox of p21 being both a growth and death inhibitor, because G1 arrest triggered by p21 can prevent cells from S phase entry, thereby escaping the fate of death through S phase checkpoint control mediated by Killin.

Results

High-Throughput Fluorescent Differential Display (FDD) Screening for p53 Target Genes.

In an attempt to systematically identify p53 target genes involved in S phase checkpoint control, we used the comprehensive FDD screening strategy that we pioneered (7, 17–20). We chose two cell types in which p53 mutations have been clearly linked to human cancer, the p53-null human lung carcinoma cell line H1299 (21) and the DLD-1 colon cancer cell line (5). Both cell lines contained tetracycline-regulated expression of the wild-type p53 tumor suppressor gene and underwent apoptosis within 24–48 h after tetracycline withdrawal (5, 21, 22). RNA and protein samples were isolated, and the induction of p53 and subsequent cell apoptosis was confirmed (Fig. 1). After DNase I treatment to remove any residual chromosomal DNA, four total RNA samples from 9- and 12-h time points without and with the induction of p53 were reverse-transcribed and processed for comprehensive FDD analysis. After screening through 192 combinations of DD primers, >12 candidate p53 target genes were identified [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6 and SI Table 1]. This represented ≈40% coverage of all of genes expressed in a cell based on a recent theoretical model of DD (20). DNA sequence analysis revealed that four of them, G20, G54, G63, and G116, corresponded to the wild-type p53 transgene itself (SI Text and SI Table 1). Among these were also several known bona fide p53 target genes, including the human homolog of mdm-2 (found twice, A10 and G10) and p21 (A21), whereas the rest of the candidate p53 target genes, including G101 (killin), NDRG1 (22), CYFIP2 (23), and Tis11D (24), were either novel genes or novel p53 targets. Our findings of p53 induction, and other major known p53 target genes, several times by FDD demonstrated excellent gene coverage and accuracy of our FDD platform, because the method is nonbiased and does not require prior knowledge of gene sequences detected (20).

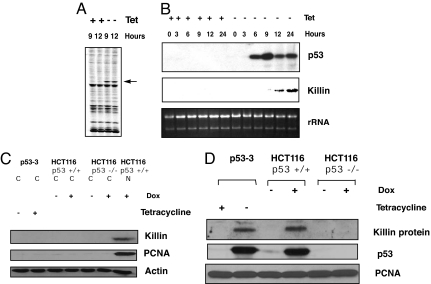

Fig. 1.

Identification and confirmation of killin (G101) as a p53 target gene. (A) Identification of killin by FDD. The p53–3 cell line was either uninduced (+tet) or induced (−tet) for wild-type p53 for the time points indicated. p53-dependent expression of killin was detected by FDD with a G-anchored primer and arbitrary primer HAP-101 (indicated by arrow). (B) Northern blot confirmation. killin cDNA was recovered from the FDD gel, cloned, and used as a probe for Northern blot confirmation of its induction by p53, which was verified by Western blot analysis. rRNA was shown as a loading control. (C) Western blot analysis of Killin as nuclear protein inducted by p53. Fifty micrograms of each protein extract (C, cytoplasmic; n, nuclear) were loaded. (D) Western blot analysis of Killin induction by either extrogenous (removal of Tet) or endogenous p53 activation (1 μM doxorubicin treatment for 24 h), as indicated. Each sample (100 μg of nuclear protein extract) was separated on a 15% SDS/PAGE and detected with the antibodies as indicated. PCNA served as a loading control.

Identification of Killin as a p53 Target Gene Encoding a Nuclear Protein.

The identification of killin as a p53 target gene by FDD and its confirmation by Northern blot analysis using the cDNA fragment recovered from FDD are shown in Fig. 1 A and B. The induction of the 4-kb killin mRNA after tetracycline withdrawal was evident at 9 h, slightly after the induction of p53, as expected. DNA sequence analysis of the 542-bp killin cDNA recovered from FDD revealed that killin is a novel gene that is normally expressed at a low level detectable only in kidney and lung (data not shown). Using the killin FDD cDNA as a probe, a 4.1-kb full-length cDNA for the gene was isolated from a human kidney cDNA library. After complete sequencing, the cDNA (GenBank accession no. EU552090) was shown to encode a small 20-kDa basic protein of 178 aa with an apparent pI of 11.3. Given its alkaline pI and the existence of two putative nuclear localization domains, we thought Killin might be a nuclear protein. Bioinformatic analysis of Killin indicated the protein did not share homology with known proteins from any species, except that two putative nuclear localization domains were noted. Importantly, Western blot analysis further confirmed that Killin was induced not only by ectopic p53 expression but also by activation of endogenous p53 in response to genotoxic stress, such as doxorubicin treatment (22), and Killin protein was indeed localized in the cell nucleus (Fig. 1 C and D).

Killin Is Localized Near the pTEN Tumor-Suppressor Gene Locus, Which Contains a Divergent Promoter Driving p53-Dependent Transcription of Killin.

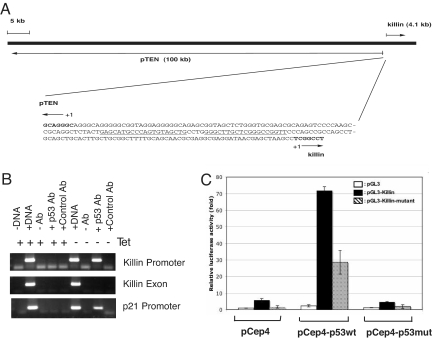

DNA sequencing and genomic database search revealed that killin is localized in close proximity to the pten tumor-suppressor gene on human chromosome 10 (Fig. 2A). In fact, the intergenic region separating the two genes (based on transcriptional start sites) is only 194 bp in length and contains a divergent promoter with a high-consensus p53-binding site (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, pTEN was previously shown to be modulated by p53 as well, although, unlike killin, the basal level of PTEN expression appears to be constitutive (25). To determine whether killin is a direct p53 target gene, we performed both ChIP and dual luciferase reporter assays using a 140-bp intergenic region containing the conserved p53-binding site (Fig. 2 B and C). The killin promoter not only was shown to bind to p53 but also conferred ≈70-fold increase in wild-type p53-dependent luciferase activity, whereas an expression vector encoding a DNA-binding mutant p53 (R248W) failed to activate the promoter. Moreover, mutations within the conserved p53-binding site in the killin promoter great decreased the p53-dependent promoter strength (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results confirm that killin is a direct transcriptional target of p53.

Fig. 2.

Killin is localized in close proximity to the pTEN tumor-suppressor gene and is transcriptionally activated by p53. (A) Chromosomal locus of killin. The 194-bp intergenic region separating killin and pTEN contains a divergent promoter with a p53 consensus-binding site (underlined). Note killin is encoded by a single exon of 4.1 kb, whereas pTEN is encoded by multiple exons and introns spanning >100 kb. (B) ChIP assay showing that p53 binds to the 140-bp killin promoter. The p21 promoter and killin exon were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. (C) luciferase reporter assays showing that the 140-bp killin promoter sequence containing the conserved p53-binding site (pGL3-Killin) conferred a dramatic p53-dependent transcription activation, whereas mutations at the key p53 consensus bases within the Killin promoter (pGL3-Killin-mutant) greatly decreased the p53 effect. Cotransfected vectors expressing either wild-type (pCep4-p53wt) or a DNA-binding mutant of p53 (R248W) (pCep4-p53mut), and the vector control (pCep4), were as indicated.

Confirmation That Killin Is Localized in Cell Nucleus.

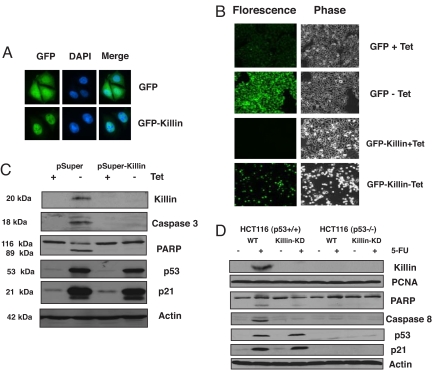

To shed light on the biological function of Killin, we first tried to confirm its subcellular localization determined by biochemical methods. To this end, a GFP-Killin in-frame fusion protein was constructed. After stable transfection into the DLD-1 colon cancer cell line with a Tet repressor, the induction of either GFP alone or GFP-Killin within 16 h after removal of tetracycline was visualized under a fluorescence microscope. In contrast to GFP alone, which was expressed throughout the cells, GFP-Killin was exclusively nuclear in localization, as shown by DAPI costaining of the nuclei (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Killin is localized in the cell nucleus and is both necessary and sufficient for p53-mediated apoptosis (A) DLD-1 cell lines stably expressing either inducible GFP or GFP-Killin was visualized by fluorescence microscopy after 16 h of induction (−tet). Note that GFP-Killin is localized exclusively in the nucleus, whereas GFP is expressed throughout the cells. DAPI was used to stain cell nuclei. (B) Inducible GFP-Killin expression causes massive cell apoptosis and detachment within 72 h. Inducible GFP alone served as a negative control. (C) RNAi knockdown of killin expression blocks extrogenous p53-induced Caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage. p53–3 cells stably transfected with either pSuper vector alone or pSuper-Killin were either noninduced (+tet) or induced (−tet) for p53 for 24 h. The induction of p53 and p21 was confirmed by Western blot analysis with β-actin as a control for equal sample loading. RNAi knockdown of killin expression led not only to diminished p53-dependent nuclear Killin protein expression but also to inhibition of Caspase-3 activation and cleavage of PARP as analyzed by Western blot. RNAi knockdown of killin expression had little effect on p53 induction and its effect on p21 expression. (D) RNAi knockdown of killin expression blocks endogenous p53-induced caspase-8 activation and PARP cleavage. HCT116 cells with or without endogenous p53 were infected with pSuperRetro-killin RNAi expression vector (Killin-KD). Cells stably selected for RNAi expression were treated or mock-treated with 5-FU (50 μg/ml) and 50 μg of either nuclear protein (for Killin and PCNA) or cytoplasmic protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot with corresponding antibodies, as indicated.

Killin Is both Necessary and Sufficient for p53-Mediated Apoptosis.

To determine whether Killin is sufficient for triggering cell growth arrest and apoptosis, we then analyzed the effect of the inducible expression of GFP-Killin over time in DLD-1 colon cancer cells. Based on measurements of cell proliferation, fluorescent microscopy, and FACS analysis, GFP-Killin was shown to cause rapid cell growth arrest within 24 h after tetracycline removal, whereas GFP alone had little effect (SI Fig. 7A). Interestingly, unlike p53-mediated growth arrest, which occurs primarily at G1 via p21 (21), FACS analysis indicated there was little decrease in S phase DNA content or increase in either G1 or G2 DNA content during the first 48 h of cell growth arrest after the induction of Killin (SI Fig. 7B). This rather surprising finding suggests that Killin may function as an inhibitor of DNA replication and causes S phase arrest. However, massive apoptosis was observed by FACS analysis and fluorescence microscopy 2–3 days after tetracycline removal and induction of GFP-Killin (Fig. 3B and SI Fig. 7B). This finding suggests that Killin-induced growth arrest is coupled to cell death, in contrast to G1 arrest mediated by p21, which prevents cells from undergoing apoptosis.

To determine whether Killin is necessary for p53-mediated apoptosis, we used RNAi technology to selectively knock down killin mRNA expression in the H1299 cell line containing an inducible wild-type p53 gene, which was used for initial FDD screening. Compared with cells stably transfected with the pSUPER control RNAi vector, cells stably transfected with pSUPER-Killin showed not only diminished Killin protein expression but also marked blockade of p53-mediated apoptosis manifested by dramatic inhibition of both caspase 3 activation and caspase-dependent PARP cleavage, and by FACS analysis of cell cycle profiles (Fig. 3C and SI Fig. 8). Moreover, blocking killin expression had little effect on p53-induced p21 expression, which led to mainly G1 arrest of the cells, as expected. Similar results were also observed for cell apoptosis mediated by the activation of the endogenous p53 via 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment to HCT116 cells (Fig. 3D), except caspase 8, instead of caspase 3, was activated.

Killin Is a High-Affinity DNA-Binding Protein.

To further biochemically and functionally characterize Killin, different experimental approaches were taken to verify this prediction. First, we tried to bacterially express and purify 6XHIS-tagged Killin. It turned out that the induction of the recombinant fusion protein by isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) caused immediate growth arrest of the bacteria hosts within 30 min when the expressed protein was barely detectable by Western blot analysis using a HIS-tag monoclonal antibody. In addition to extremely low-level expression before cells stopped growing, bacterially expressed Killin appeared to adopt a unique conformation (e.g., association with other molecules such as DNA), which prevents it from being able to bind to the Ni-NTA column, making its purification in native form literally impossible. The extremely toxic effect of low-level Killin expression in bacteria appeared to concur with our prediction that it is a general DNA synthesis inhibitor, given that bacteria have naked DNA. To overcome the difficulty in expression and purifying Killin protein, full-length Killin with predicted 20-kDa molecular mass was produced by in vitro transcription and translation and was shown to be able to bind to both single- and double-stranded DNA templates (SI Fig. 9).

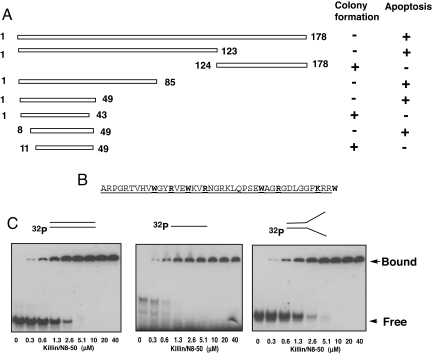

To further confirm and better define the functional domain of Killin for DNA binding, we then turned to a genetic approach by taking advantage of the toxicity of Killin expression in Escherichia coli. We hypothesized that the toxicity of Killin in mammalian cells and bacteria is functionally related and might have something to do with its ability to bind DNA and inhibit DNA replication. To test this hypothesis, we first truncated the coding region of Killin into two parts at a unique Eco47III restriction site and showed that the N-terminal 123 amino acids were sufficient to retain toxicity to E. coli, whereas the plasmid expressing the C-terminal 124- to 178-aa residues was able to transform E. coli into colonies in the absence of transcriptional repression (Fig. 4A). To speed up the genetic screen for the functional domain of Killin, we then randomly mutagenized the plasmid encoding the full-length N-terminal HIS-tagged Killin using an alkylating agent, ethylmethanesulfonate (EMS). Compared with the nonmutagenized vector, the mutagenesis allowed colony formation after transformation into a wild-type LacI host. DNA sequencing analysis revealed that the loss-of-function mutations of killin fell into five groups, and they were premature nonsense mutations either at codons 18, 24, 33, and 37 or with a deletion of a tandem-repeat sequence within the promoter region of the pQE32 bacterial expression vector. The concentration of the loss-of-function mutations near the N terminus of Killin suggested that its functional domain is smaller than initially anticipated. Further-refined deletional mutagenesis was then conducted by PCR from both the N and C termini of Killin, and the results allowed us to unambiguously pinpoint the minimal sequence from 8- to 49-aa residues, which were essential for Killin's toxicity in bacteria (Fig. 4B). The same Killin deletion mutants fused to GFP were also tested for their ability to cause apoptosis (nuclear condensation) in H1299 cells (Fig. 4A). The results were consistent with those seen with toxicity assays in bacteria. It is interesting to note that the minimum essential region of Killin contained multiple WXXR or KXXW motifs and is rich in basic amino acids (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Killin is a high-affinity DNA-binding protein. (A) Bacterial genetic screen and serial deletion analysis of the functional domain of Killin. pQE32 bacterial expression vectors encoding either the full-length N-terminal His-tagged Killin (1–178 aa) or truncated Killin, as indicated, were transformed into either XL-1 blue (lac Iq with repression) or GH1 (wild-type lac I without repression) competent cells and selected with ampicillin in the absence of IPTG. Killin deletions that retained the ability to kill E. coli were scored for their ability to inhibit colony formation in GH1 cells. The same Killin deletion mutants fused to GFP were also transfected into H1299 cells and tested for their ability to cause apoptosis (nuclear condensation) within 36 h. (B) Amino acid sequence of Killin/N8–50 peptide with the minimum 8- to 49-aa residues underlined. (C) In vitro DNA-binding kinetics of Killin/N8–50 peptide. 32-P end-labeled double-stranded, single-stranded, and artificial replication fork DNA templates of 32–35 bases or base pairs in length were each incubated with increasing concentration of Killin/N8–50 peptide, as indicated. The reactions were resolved on a 6% TBE PAGE gel.

To overcome the difficulty in high-level expression of Killin because of its toxicity, we chemically synthesized a peptide of 42 amino acid residues in length corresponding to N8–50 of Killin (Fig. 4B, hereunder designated as Killin/N8–50). In vitro kinetic binding studies using 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide probes demonstrated that the Killin/N8–50 peptide was able to bind to double-stranded DNA and an artificial replication fork with an apparent Kd of 1–2 μM, whereas the affinity to the single-stranded DNA template appeared to be slightly higher with an apparent Kd of 0.5 μM (SI Fig. 10). This important finding provides a biochemical basis for Killin function.

Killin Inhibits DNA Synthesis in Vitro and in Vivo.

To determine whether Killin/N8–50 peptide binding to DNA has any consequences in DNA replication, we used the commonly used in vitro eukaryotic DNA replication assays originally described by Li and Kelly (26). This assay uses a soluble cell-free system derived from a mammalian cell nuclear extract that is capable of replicating exogenous plasmid DNA molecules containing the simian virus 40 (SV40) origin of replication. Replication in the system depends completely on the addition of the SV40 large T antigen. Using this assay, we showed that the Killin/N8–50 peptide could greatly inhibit DNA replication (Fig. 5A). The requirement of a higher concentration of Killin/N8–50 peptide for the inhibition of DNA replication than that seen in the in vitro DNA-binding assays was most likely because of the high concentration of chromosomal DNA present in the nuclear extracts used as a source of the SV40 large T antigen. Such chromosomal DNA would conceivably compete against the plasmid template for Killin peptide binding, thus competitively inhibiting plasmid DNA replication. This prediction was consistent with results obtained by decreasing the amount of nuclear extract used for the assay (data not shown).

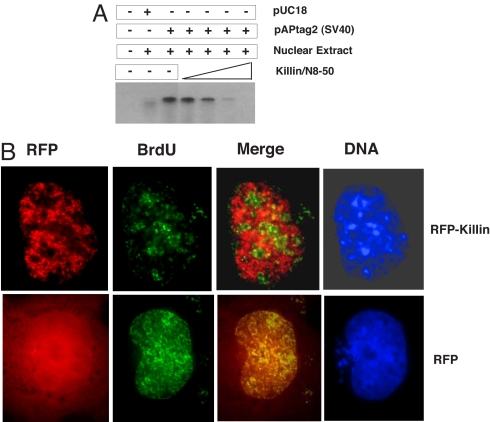

Fig. 5.

RFP-Killin inhibits DNA replication in vitro and in vivo. (A) Killin/N8–50 peptide inhibits DNA synthesis in vitro. Nuclear extract of HEK293T cells (expressing the SV40 T antigen) was incubated with either control vector pUC18 and pAPtag2 (SV40 Ori) in the absence and presence of an increasing amount of the Killin/N8–50 peptide (0.1, 0.5, 5, and 10 μM). (B) The RFP-Killin in-frame fusion protein (Upper) or RFP control (Lower) expression vectors were transiently transfected into Cos-E5 cells by using FUGEN-6. Twenty-four hours after transfection, S phase cells undergoing DNA replication were visualized after 30-min pulse label with BrdU followed by FITC-labeled anti-BrdU antibody staining (in green), under a Zeiss fluorescent microscope (×40). For cells in which the RFP-Killin (red) and BrdU signals (green) colocalized, the bulk of DNA replication foci (origins of replication) were missing in the area where the RFP-Killin foci reside. The overlay of fluorescent signals from BrdU labeling with RFP-Killin (Merge) always exhibit a mutually exclusive pattern, in contrast to control cells transfected with RFP alone. DAPI was used to stain DNA (nuclei). Results shown were representative of multiple cells from at least two independent experiments.

To pinpoint whether Killin directly blocks DNA replication in vivo, we then designed the following elegant experiment. Because any S phase cells among a cell population in culture can be marked by pulse labeling with BrdU, which can be visualized by a FITC-labeled monoclonal antibody, we asked whether we could see any S phase cells expressing RFP-Killin. To do so, we transiently transfected an RFP-Killin expression vector into Cos-E5 cells that have large nuclei and are nontransformed. Sixteen hours after transfection, cells were pulse-labeled with BrdU for 30 min to mark S phase cells. After immunostaining of BrdU (in green), we noticed that few of the RFP-Killin cells had BrdU signals, as predicted, in contrast to RFP-transfected control cells (SI Fig. 11). However, this finding suggested only that a majority of RFP-Killin-expressing cells could not enter S phase, rather than that they were arrested at S phase. Interestingly, we were also able to find a few rare cells that had both BrdU incorporation and RFP-Killin expression in the same nuclei (Fig. 5B; SI Fig. 11). When BrdU-labeled DNA replication foci (in green) were overlaid with that of RFP-Killin (in red) in the same cell, an amazing picture emerged: BrdU and RFP-Killin showed an essentially mutually exclusive nuclear pattern, with a majority of replication foci appearing blocked by RFP-Killin when compared with RFP control. The beads-on-string nuclear appearance of RFP-Killin is consistent with Killin being a high-affinity DNA-binding protein with a preference for ssDNA. We believed these were rare S phase cells expressing a rate-limiting amount of Killin when BrdU was added, so there was not enough RFP-Killin to block all replication foci. However, in reality, even if one replication becomes blocked (e.g., by endogenous Killin induced by p53 activation), which could be much harder to visualize, the cell may still not be able to complete S phase. Similar results were obtained in H1299 cells (data not shown). This crucial piece of evidence strongly supports that Killin directly blocks DNA replication in vivo.

Discussion

In this study, we described the identification of a p53 target gene we dubbed killin (for its ability to kill animal cells and bacteria) and showed its direct involvement in p53-mediated cell growth arrest coupled with cell apoptosis. Compelling evidence from cell biological, genetic, and biochemical analysis of the gene suggests the following possible mechanism of action for Killin in mediating tumor-suppressor p53 functions. Upon induction by p53 during S phase, Killin functions in the cell nucleus as a DNA synthesis inhibitor via its high affinity to both double- and single-stranded DNA (e.g., at the replication forks) and thereby causes S phase arrest, which in turn triggers subsequent cell apoptosis. Thus, Killin-mediated checkpoint control at S phase would complement that at G1 mediated by p21 and G2-M phase by p21, GADD45, and 14-3-3 and provides a foolproof mechanism for p53 in preventing precancerous cells from replicating their DNA content. Therefore, Killin represents a p53 target gene that is directly and functionally involved in S phase checkpoint control, which is coupled to apoptosis, in contrast to p21-mediated G1 arrest, which is antiapoptotic. The unique function of Killin in coupling S phase arrest with apoptosis may also help explain why p21-mediated G1 arrest can be antiapoptotic. Conceivably, prevention of cells from S phase entry by p21 would spare cells from Killin-mediated inhibition of DNA synthesis. It is predicted that p21-deficient cells will be very sensitive to Killin-induced apoptosis and to p53 activation, which may now be experimentally tested. Without stalled replication forks caused by Killin, apoptosis may be avoided. The high affinity of Killin to both double- and single-stranded DNA could also be reconciled with the beads-on-string distribution pattern of RFP-Killin in S phase nuclei. Future efforts are needed to determine how Killin-mediated DNA replication arrest triggers the activation of caspase and apoptosis. We have evidence that this may involve activation of components of the DNA damage response network, such as Chk1 and Chk2, which are known substrates of ATM and ATR (SI Text and SI Fig. 12).

On close inspection of the minimal 41-aa Killin peptide sequence essential for DNA binding in vitro and killing of bacteria in vivo, we noted multiple WXXR and KXXW motifs (Fig. 4B). Although a theoretical protein-folding prediction could not provide the definitive secondary structure of the Killin/N8–50 peptide, conceivably these regular motifs would bring R, K, and W residues along the same surface for DNA binding should the peptide fold into binary α helices that are connected by the single proline residue within the peptide sequence. The binary DNA-binding fingers could allow Killin to bind to more than one DNA template, causing it to tangle up, which may explain why the DNA-Killin/N8–50 peptide complex had dramatically retarded mobility on the gel. Conceivably, tryptophan (W) may interact with purine or pyrimidine bases, whereas basic amino acid residues arginine (R) and lysine (K) may interact with phosphates in the DNA. The tight binding of Killin to DNA may prevent DNA synthesis machinery from accessing or moving along the template, thus leading to inhibition of DNA synthesis and S phase arrest. Future structural-functional studies by NMR and sited-directed mutagenesis should help verify or refine our prediction. The short Killin peptide (41–42 aa) and its potent activity in DNA binding, inhibition of eukaryotic DNA synthesis, and ability to trigger apoptosis also make it a good candidate as a peptide drug for cancer treatment.

The extremely close proximity of killin and pten is also of great interest, because it would make killin a candidate tumor-suppressor gene. pten was originally identified as a candidate tumor suppressor by positional cloning from the chromosome 10q23 region, which is frequently deleted in a variety of human tumors (27, 28). Although pTEN is encoded by multiple exons spanning >100 kb, killin resides in a single exon of only 4.1 kb with a <200-bp intergenic region. In fact, 50% of the human glioma cell lines with which pTen deletions were initially mapped had deletions beyond the killin locus (28). The genomic DNA probe commercially available for FISH analysis of pten deletion or loss of heterozygosity spans the killin locus (29), suggesting that many previously reported pten deletions in human cancers may also have killin deleted. The extremely short 194-bp intergenic region connecting the two genes contains a divergent promoter that appears to be p53-responsive for both pten (25) and killin, with the latter shown here to be completely p53-dependent. One logical prediction for a major p53 target gene, such as killin, would be that such a gene could be a tumor suppressor on its own. This is supported by the nonoverlapping mutation spectra in human tumors for p53 and the pten region (30). Future mutational analysis in cancer and genetic studies in animal models may help further define the role of Killin in tumor suppression.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Cell Transfection, RNA Isolation, FDD, Northern Blot Analysis, and cDNA Library Screening.

Inducible p53 cell lines were cultured as described (5, 21). The Cos-E5 cell line was obtained from GenHunter. Cell transfection, FDD screening, and Northern blot analysis were carried out essentially as described (22). A 4.1-kb full-length killin cDNA was isolated from a human kidney cDNA library (Stratagene) by using the killin FDD cDNA probe and completely sequenced.

Antibodies and Western Blots.

Antibodies used for this study were: p53 (Oncogene), p21 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), actin (Sigma), PARP, caspase 8 and 3 (Cell Signaling), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (Dako), and BrdU (Molecular Probes). The poyclonal Killin antibody was generated by Covance by using the C terminus of Killin (amino acids 124–178) fused to GST (pGEX4T-1) as an antigen. Subcellular fractionation of cytoplasmic vs. nuclear proteins was carried out by using the standard protocol with Nonidet P-40 lysis (for cytoplasmic proteins) followed by high salt extraction (for nuclear proteins).

RNA Interference.

RNAi sequence targeting killin, 5′-GGATACACGGGCCACAGTC-3′ (positions 153–171), was selected. Primers used were: GATCCCCGGATACACGGGCCACAGTCTTCAAGAGAGACTGTGGCCCGTGTATCCTTTTTGGAAA and reverse primer AGCTTTTCCAAAAAGGATACACGGGCCACAGTCTCTCTTGAAGACTGTGGCCCGTGTATCCGGG. The annealed RNAi template was cloned into BglII and HindIII sites of pSUPER or pSuperRetro (31) and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

FACS Analysis, Immunoblotting, and Fluorescent Microscopy.

FACS analysis and immunoblotting, including sources of antibodies, were essentially as described (22). For Western blot analysis of endogenous Killin, nuclear extracts were used. Fluorescent microscopy was carried out by using a Zeiss 200M inverted fluorescence microscope (Zeiss). Captured images were analyzed by using Openlab software (Improvision).

In Vitro DNA Binding and SV40 DNA Replication Assays.

For peptide binding, 42 amino acids of Killin/N8–50 peptide (5,007 kDa) were synthesized by Sigma–Genosys. For the in vitro DNA-binding assay, three primers (32–35 bases in length) with arbitrary sequences (LL: 5′-TTTGCACGTCGGATCCGACCCAGACTACGGAGGCC-3′, RLM: 5′-GGCCTCCGTAGTCTGGGTCGGATCCGACGTGC-3′, and RL: 5′-CCGGAGGCATCAGACGGTCGGATCCGACGTGC-3′) were designed. After annealing, probes for the artificial replication fork (LL and RL) or double-stranded DNA template (LL and RLM) were end-labeled with α32P-dATP (Perkin–Elmer) by using Klenow (New England Biolabs). A single-stranded oligonucleotide (LL) was end-labeled with α-32P-dATP (Perkin–Elmer) by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). The labeled probes (200,000 cpm each) were mixed with an increasing amount of Killin/N8–50 peptide in the presence of 20 mM Tris·Cl (pH 8.4), 25 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 100 μg/ml of BSA. The reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel with 1× TBE buffer. After drying the gel onto Whatman no. 1 filter paper, the DNA–protein complexes were visualized by autoradiography. For binding kinetics, bands from the DNA–peptide complex were excised, and the radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting. The SV40 origin of replication-dependent in vitro DNA replication was carried out essentially as described (26).

Random Mutagenesis, Deletion Analysis, and Genetic Screen of Killin.

Mutagenesis experiments were performed by using EMS (Sigma) (32). Ampicillin-resistant colonies were obtained, and plasmids containing loss-of-function mutations were sequenced. For deletion analysis, PCR was performed to amplify different regions of Killin. The PCR products were cloned as BglII fragments into the BamHI site of the pQE32 expression vector (Qiagen). The expression vectors were transformed into both GH1 (without repression) and XL-1 blue under transcription repression to score for toxicity.

Visualization of RFP-Killin and BrdU in S Phase Cells.

The entire coding region of Killin was PCR amplified with primer B1: 5′-CGCGGATCCGATCGCCCGGGGCCAGGCTCC-3′ and B2: 5′-CGCGGATCCTCAGTCCTTTGGCTTGCTCTT-3′, and subcloned into pDsRed- ExpC1 (Clontech) to generate pRFP-Killin. RFP-Killin- or RFP-expressing vectors were transiently transfected into Cos-E5 cells for 24 h before S phase cells were pulsed labeled with 10 mM BrdU (Sigma) for 30 min and visualized as described (33). See SI Text for additional materials and methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank J. Yu and B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore) for providing DLD1 (TetR) and DLD-1 with an inducible wild-type p53, X. B. Chen and C. Prives (Columbia University, New York) for H1299 cells with an inducible wild-type p53, and R. Agami (Netherlands Cancer Center, Amsterdam) for pSUPER. We also acknowledge M. K. Cha for assistance with the FDD screenings, M. Cardoso for S phase cell imaging, and R. Jackson and A. Pardee for critical proofreading of the manuscript. This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants CA76969 (to P.L.) and CA105024 (to P.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705410105/DC1.

References

- 1.Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vousden K-H, Prives C. p53 and prognosis: New inisights and further complexity. Cell. 2005;120:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Deiry WS. Regulation of p53 downstream genes. Semin Cancer Biol. 1998;8:345–357. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Rago C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Identification and classification of p53-regulated genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:14517–14522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vousden KH, Lu X. Live or let die: The cell's response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang P, Pardee AB. Analyzing differential gene expression in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3:869–876. doi: 10.1038/nrc1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dulic V, Kaufmann WK, Wilson SJ, Tlsty TD, Lees E, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Reed SI. p53-dependent inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase activities in human fibroblasts during radiation-induced G1 arrest. Cell. 1994;76:1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Deiry WS, Harper J-W, O'Connor P-M, Velculescu VE, Canman C-E, Jackman J, Pietenpol J-A, Burrell M, Hill D-E, Wang Y, Wiman K-G, Kastan M-B, Kohn K-W, Elledge J, Kinzler K-W, Vogelstein B. WAF1/CIP1 is induced in p53-mediated G1 arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1169–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng C, Zhang P, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Leder P. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell. 1995;82:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor WR, Stark GR. Regulation of the G2/M transition by p53. Oncogene. 2001;20:1803–1815. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu J, Zhang L. The transcriptional targets of p53 in apoptosis control. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polyak K, Waldman T, He TC, Kinzler K-W, Vogelstein B. Genetic determinants of p53-induced apoptosis and growth arrest. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1945–1952. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.15.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu J, Wang Z, Kinzler K-W, Vogelstein B, Zhang L. PUMA mediates the apoptotic response to p53 in colorectal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1931–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2627984100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nahle Z, Polakoff J, Davuluri R-V, McCurrach M-E, Jacobson M-D, Narita M, Zhang M-Q, Lazebnik Y, Bar-Sagi D, Lowe S-W. Direct coupling of the cell cycle and cell death machinery by E2F. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:859–864. doi: 10.1038/ncb868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottifredi V, Prives C. The S phase checkpoint: When the crowd meets at the fork. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang P, Pardee A-B. Differential display of eukaryotic mRNA by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Science. 1992;257:967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1354393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho Y, Meade J, Walden J, Guo Z, Chen X, Liang P. Multicolor flourescent differential display. BioTechniques. 2001;30:562–572. doi: 10.2144/01303rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang P. A decade of display. Biotechniques. 2002;33:338–346. doi: 10.2144/02332rv01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang S, Liang P. Global analysis of gene expression by differential display, a mathematical model. Mol Biotechnol. 2004;3:197–208. doi: 10.1385/MB:27:3:197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Ko LJ, Jayaraman L, Prives C. p53 levels, functional domains, and DNA damage determine the extent of the apoptotic response of tumor cells. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2438–2451. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein S, Thomas E-K, Herzog B, Westfall M-D, Rocheleau J-V, Jackson R, Wang M, Liang P. NDRG1 is necessary for p53-dependent apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48930–48940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson RS, 2nd, Cho YJ, Stein S, Liang P. CYFIP2, a direct p53 target, is leptomycin-B sensitive. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:95–103. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.1.3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson R-S, Cho Y-J, Liang P. TIS11D is a candidate pro-apoptotic p53 target gene. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2889–2893. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.24.3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stambolic V, MacPherson D, Sas D, Lin Y, Snow B, Jang Y, Benchimol S, Mak T-W. Regulation of PTEN transcription by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;8:317–325. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J-J, Kelly T-J. Simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6973–6977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.6973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanina K, Bose S, Wang S-I, Puc J, Miliaresis C, Rodgers L, McCombie R, Bigner S-H, Giovanella B-C, Ittmann M, Tycko B, Hibshoosh H, Wigler M-H, Parsons R. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steck PA, Pershouse M-A, Jasser S-A, Yung W-K, Lin H, Ligon A-H, Langford L-A, Baumgard M-L, Hattier T, Davis T, Frye C, Hu R, Swedlund B, Teng D-H, Tavtigian S-V. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat Genet. 1997;15:356–362. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshimoto M, Cutz J-C, Nuin P-A, Joshua A-M, Bayani J, Evans A-J, Zielenska M, Squire J-A. Interphase FISH analysis of PTEN in histologic sections shows genomic deletions in 68% of primary prostate cancer and 23% of high-grade prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasias. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;169:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurose K, Gilley K, Matsumoto S, Watson PH, Zhou XP, Eng C. Frequent somatic mutations in PTEN and TP53 are mutually exclusive in the stroma of breast carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2002;32:355–357. doi: 10.1038/ng1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller JH. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press; 1992. Mutagenesis with EMS; pp. 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Easwaran H, Leonhardt H, Cardoso M. Cell cycle markers for live cell analyses. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:e53–e55. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.3.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.