Abstract

Contact patterns in populations fundamentally influence the spread of infectious diseases. Current mathematical methods for epidemiological forecasting on networks largely assume that contacts between individuals are fixed, at least for the duration of an outbreak. In reality, contact patterns may be quite fluid, with individuals frequently making and breaking social or sexual relationships. Here, we develop a mathematical approach to predicting disease transmission on dynamic networks in which each individual has a characteristic behaviour (typical contact number), but the identities of their contacts change in time. We show that dynamic contact patterns shape epidemiological dynamics in ways that cannot be adequately captured in static network models or mass-action models. Our new model interpolates smoothly between static network models and mass-action models using a mixing parameter, thereby providing a bridge between disparate classes of epidemiological models. Using epidemiological and sexual contact data from an Atlanta high school, we demonstrate the application of this method for forecasting and controlling sexually transmitted disease outbreaks.

Keywords: infectious disease, susceptible–infected–recovered, networks, concurrency, syphilis

1. Introduction

Most epidemic models incorporate a homogeneous mixing assumption, sometimes called the law of mass action (Ross 1910; Anderson & May 1991; Diekmann & Heesterbeek 2000), whereby the rate of increase in epidemic incidence is proportional to the product of the number of infectious and susceptible individuals. This assumption has been relaxed in some compartmental (van den Driessche & Watmough 2002) and metapopulation models (Lloyd & May 1996; Finkenstadt & Grenfell 1998; Grenfell et al. 2001; Watts et al. 2005), but not eliminated. The mass-action assumption is robust in the sense that it is consistent with several scenarios for the individual-to-individual transmission of disease. In particular, it is equivalent to a model in which all individuals in a population make contact at an identical rate and have identical probabilities of disease transmission to those contacts per unit of time. Although this assumption is unrealistic, it facilitates mathematical analysis and, in some cases, offers a reasonable approximation.

Populations can be quite heterogeneous with respect to susceptibility, infectiousness, contact rates or number of partners, and simple homogeneous mixing models do not allow for extreme variation in host parameters. New network-based mathematical methods capture some, but not all, aspects of population heterogeneity (Gupta et al. 1989; Andersson 1998; Callaway et al. 2000; Liljeros et al. 2001; Strogatz 2001; Newman 2002a; Newman et al. 2002). Ideally, an epidemic model would incorporate the following realities of human-to-human contacts:

A given individual has contact with only a finite number of other individuals in the population at any one time, and contacts that can result in disease transmission are usually short and repeated events.

The number and frequency of contacts between individuals can be very heterogeneous.

The numbers and identities of an individual's contacts will change as time goes by.

The first two points have been addressed previously by static network models (Eames & Keeling 2002; Newman 2002a; Meyers et al. 2005, 2006). We will focus on the third point and introduce a modelling framework that allows an individual's contacts to change in time.

Concurrent and serial contacts were first shown to be important to HIV transmission dynamics by Dietz (1988) and Watts & May (1992). In the public health literature, the number of concurrent contacts has long been understood to be important for sexually transmitted disease (STD) transmission (Ford et al. 2002; Manhart et al. 2002; Adimora et al. 2006), independently of cumulative number of contacts. Epidemics in dynamic networks have been modelled using high-dimensional pair-approximation methods (Altmann 1995, 1998; Eames & Keeling 2004) and moment closure methods on dynamic contact networks (Ferguson & Garnett 2000; Bauch 2002). Others have conducted simulation-based studies (Chick et al. 2000; Doherty et al. 2006).

Here, we introduce a low-dimensional system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to model susceptible–infected–recovered (SIR) epidemics in a simple class of dynamic network. We find this provides a useful departure point for mathematical analysis, although it does not incorporate as much detail as some other models. This model complements earlier work by providing a relatively simple framework that is less computationally demanding, easier to implement and amenable to the derivation of fundamental results. Our methods are compared with the more commonly used pair-approximation methods in the electronic supplementary material.

We use our dynamic network model to characterize the impacts of population heterogeneity and contact rates on epidemic dynamics. We further show that the model reproduces basic classes of epidemiological models, such as the standard mass-action SIR model and static network model, as the parameter that controls population mixing varies.

2. Neighbour exchange model

Human contact patterns are potentially complex, as the numbers and intensity of contacts can vary considerably across a population. Furthermore, contacts are transitory events such that the identities of one's contacts change in time. To capture such heterogeneity, we introduce the neighbour exchange (NE) model as a simple extension of a static contact network model. In this model, an individual's number of concurrent contacts remains fixed while the composition of those contacts changes at a specified rate. The model assumes that at any given time, an individual will be in contact with an individual-specific number of neighbours with whom disease transmission is possible. Each contact is temporary, lasting a variable amount of time before coming to end, at which point the neighbour is replaced by a different individual.

Let the population of interest consist of n individuals, each of which falls into one of three exclusive states: susceptible, infectious or recovered. At some time t, an individual ego will have contacts with other individuals (i.e. alters): . Only undirected contact networks will be considered such that if there exists a contact (ego, alter) there will also be a contact (alter, ego). In network terminology, a directed link, denoted (ego, alter), is called an arc. An undirected link, denoted {ego, alter}, is called an edge. The degree of a node ego is the number of edges connected to the node. The term contact will be used specifically to denote a directed arc in the network, where two arcs correspond to each undirected edge. The k-degree of a node will be the number of concurrent contacts to/from the node (table 1).

Table 1.

Notation for epidemic and network parameters.

| S | the fraction of population susceptible |

| I | the fraction of population infectious |

| R | the fraction of population recovered |

| set of susceptible nodes | |

| set of infectious nodes | |

| set of recovered nodes | |

| J | cumulative epidemic incidence (J=I+R) |

| r | transmission rate |

| μ | recovery rate |

| ρ | mixing rate |

| k ego | degree of node ego |

| p k | the fraction of nodes with degree k |

The NE model assumes that the identities of a node's neighbours will continually change, while the total number of current neighbours remains constant. This occurs through an exchange mechanism in which the destination nodes of two edges are swapped. For example, two nodes ego and ego′ with distinct contacts (ego, alter) and (ego′, alter′) may exchange contacts such that these are replaced with (ego, alter′) and (ego′, alter). There are two edges and four contacts involved in each edge swap. The fate of each edge and contact is summarized in the following pseudo-chemical equation:

| (2.1) |

In the model, any given contact (ego, alter) will be reassigned to (ego, alter′) at a constant rate ρ. Equivalently, a given edge is swapped at a rate p/2.

A node's degree never changes during an edge swap and thus the degree distribution is preserved. This property has made the random edge swap a common starting point for investigations of dynamic networks. Discrete-time versions of the rewiring process have been well studied in applications outside of epidemiology (Watts & Strogatz 1998; Maslov & Sneppen 2002; Evans & Plato 2007; Holme & Zhao 2007)

For mathematical tractability, we make a few simplifying assumptions about the epidemic process. First, for the duration of a contact, infectious individuals transmit disease to neighbours at a constant rate r. Second, infectious individuals become recovered at a constant rate μ.

We also simplify the mathematics by considering only the simplest category of heterogeneous networks—semi-random networks that are random with respect to a given degree distribution (Molloy & Reed 1995, 1998). The degree distribution will have density pk, which is the probability that a node chosen uniformly at random has k concurrent contacts.

The simultaneous epidemic and network dynamics described above collectively determine the NE model. An even more realistic model would allow the number k of concurrent contacts of a node to vary stochastically, but the current model offers a valuable first step towards understanding epidemiological processes on dynamic host networks.

(a) Dynamics

We will expand on the dynamic probability generating function (PGF) techniques first introduced in Volz (2007) to model SIR-type epidemics in static networks. These techniques are powerful and are easily extended to consider dynamic contact networks. We start with an overview of the basic model and then introduce additional terms that model the NE process.

The concurrent degree distribution pk will be generated by the PGF

| (2.2) |

The dummy variable x in this equation serves as a placeholder for dynamic variables.

Let X be the sets of contacts (arcs) where ego is in the set X. We will consider the sets of all susceptible, infected and recovered nodes, denoted , and , respectively. is then defined as the fraction of total contacts in set X. Now let XY be the set of contacts such that ego is the set X and alter is in the set Y, and be the fraction of total contacts in set XY. For example, is the fraction of all arcs in the network that connect two currently susceptible nodes (table 2).

Table 2.

Notation for network and epidemic quantities.

| set of contacts (ego, alter) s.t. ego∈X | |

| XY | set of contacts (ego, alter) s.t. ego∈X and alter∈Y |

| M X | fraction of contacts in set X |

| M XY | fraction of contacts in set XY |

| fraction of contacts from susceptibles which go to infectious nodes | |

| fraction of contacts from susceptibles which go to other susceptible nodes |

The following derivation assumes that each contact of a susceptible node has a uniform probability that , denoted , and a uniform probability that . A degree k susceptible node has an expected number contacts with infectious nodes; and, in a small time dt, an expected number of a degree k susceptible nodes' contacts will transmit disease to that node. The instantaneous hazard of infection for a degree k susceptible node is then given by

| (2.3) |

Let denote the fraction of degree k nodes remaining susceptible at time t. Equation (2.3) implies

| (2.4) |

Now let be the fraction of degree k=1 nodes in the network that remain susceptible at time t. Equation (2.4) implies that . (Henceforth, variables that are clearly dynamic, for example θ, appear without a time (t) variable.)

We use the PGF for the network degree distribution (equation (2.2)) to calculate the fraction of nodes that remain susceptible at time t.

| (2.5) |

The dynamics of θ in equation (2.5) are given by

| (2.6) |

Unfortunately, this does not form a closed system of differential equations, as equation (2.6) depends on the dynamic variable pI. From the definition of pI we have

| (2.7) |

To obtain the derivatives of and , we observe that, in time dt, nodes become infectious, resulting in modifications to the sets , and . In particular, any given arc from a newly infected individual was formerly in one of , or and is now in one of , or . The new infected are not selected uniformly at random from the susceptible population, but rather with probability proportional to the number of contacts to infectious nodes.

We pause for a few definitions. First, it is useful to break the degree of a node into three quantities: the number of contacts to currently susceptible, infected and recovered nodes. We refer to these as X-degrees, where or R, respectively. Second, imagine following a randomly chosen contact to its alter and counting all the edges emanating from that node, except for the one on which we have arrived. We call the resulting total quantity the excess degree of the node, and the resulting neighbour-specific quantities excess X-degrees of the node, where X indicates one of the three possible disease states.

We introduce the notation to represent the average excess Z-degree of nodes currently in disease state X selected by following a randomly chosen arc from the set ; in other words, the excess Z-degree of a node of type X selected with probability proportional to the number of contacts to nodes of type Y. We further define to be the average (total) excess degree of nodes currently in disease state X selected by following a randomly chosen arc from the set . For example, imagine first randomly choosing an arc from , then following that arc to its destination (susceptible) node and finally counting all of the other edges emanating from that node (ignoring the one along which we arrived). Then , and give the average number of contacts to other susceptible, infected and recovered nodes chosen in this way, respectively; gives the average total number of contacts emanating from nodes chosen in this way.

Using this notation, the equations for and are as follows (for more details, see Volz (2007))

| (2.8) |

| (2.9) |

| (2.10) |

| (2.11) |

The calculations of the are straightforward and based on the current degree distribution of susceptible nodes. The calculations are given in the electronic supplementary material and in Volz (2007) and result in the following:

| (2.12) |

| (2.13) |

Combining the equations for and yields the dynamics of pI in terms of the parameters r and μ, the PGF g(·), and the dynamic variable pS. The resulting model is given in table 3. The dynamics for pS complete the model and can be derived analogously to the equation for pI (see the electronic supplementary material for details).

Table 3.

System of equations used to model the spread of SIR epidemic in a static semi-random network.

| S=g(θ) |

(i) Dynamic contact networks

We now extend the model given in table 3 to allow NEs at a rate ρ. First consider θ. An edge swap (equation (2.1)) will affect the arrangement of edges among susceptible, infectious or recovered nodes; however, it will never directly cause a node to change its disease state. The dynamics of θ are only indirectly influenced by NE dynamics, through changes to pI, and thus equation (2.6) still holds.

NE does, however, affect the composition of contacts between susceptible and infectious nodes. We postulate that the equations for and can be expressed in the following modified forms:

| (2.14) |

and

| (2.15) |

where the functions represent the contribution of NE dynamics to the system.

NE dynamics can both decrease or increase the values of pI and pS. First, consider the decrease of pI due to NE dynamics.

At rate ρ, a given contact (ego, alter) will transform to (ego, alter′).

Given that (ego, alter)∈S, with probability .

With probability , .

Thus pI will be decreased by NE dynamics at a rate .

Similarly, pI can increase due to NE as follows:

At rate ρ, a given contact (ego, alter) will transform to (ego, alter′).

Given that , with probability 1−pI.

With probability MI, .

Thus pI is increased by NE dynamics at rate . We add the positive and negative contributions to calculate the total influence of NE on pI.

| (2.16) |

By similar reasoning, we determine .

| (2.17) |

The complete system of NE-adjusted equations is reported in table 4. The dynamic variable MI, however, appears in equation (2.17) and cannot be put in terms of the variables θ, pS and pI. Therefore, a fourth dynamical equation must be included for MI, which is listed in table 4. Fortunately, the dynamics are very straightforward. Recall that δS,I denotes the average excess degree of susceptibles chosen by following randomly selected arcs between infectious and susceptible nodes, and thus indicates the average excess degree for individuals who become infected in a small time interval dt. We add one () to obtain the average degree for such newly infected nodes. Then, recalling that MI decays at rate μ, we have

| (2.18) |

Table 4.

Deterministic NE model. (This system of equations is used to model the spread of an SIR-type epidemic in a dynamic semi-random network with stochastic exchange of neighbours at constant rate ρ.)

| S=g(θ) |

All of the results that follow will assume that a very small fraction ϵ of nodes is initially infected, and thus there is only a very small probability that two initially infected individuals contact each other. Then we anticipate the following initial conditions (Volz 2007):

| (2.19) |

| (2.20) |

| (2.21) |

(b) Convergence to a mass-action model

In the limit of large mixing rate (ρ→∞), the probability of being connected to a susceptible, infectious or recovered node is directly proportional to the number of edges emanating from nodes in each state. Referring to table 4, it is clear that pI converges instantly to MI and pS converges instantly to MS. Here, we show that as the mixing rate grows, the underlying network structure becomes irrelevant and the model converges to a mass-action model.

To see this, we replace every occurrence of the variable pI in the system of equations in table 4 with MI. Then

| (2.22) |

| (2.23) |

Neither equations (2.22) or (2.23) depend on pS, and thus together form a closed system of equations that describe the epidemic dynamics. These equations incorporate arbitrary heterogeneity in contact rates, but no longer consider an explicit contact network. When we assume that contact rates are homogeneous throughout the population, then these equations are equivalent to a simple SIR compartmental model. To illustrate, we retrieve the standard SIR dynamics by setting g(x)=x, which means that every node has exactly one concurrent contact. In such a population, the number of arcs to infectious individuals is exactly equal to the number of infectious nodes, that is, pI=I. Then, substituting into equations (2.22) and (2.23), we reproduce the standard equations

| (2.24) |

| (2.25) |

| (2.26) |

Equations (2.22) and (2.23) are potentially extremely useful, as they incorporate arbitrary heterogeneity into a system of equations no more complex than the standard compartmental SIR model.

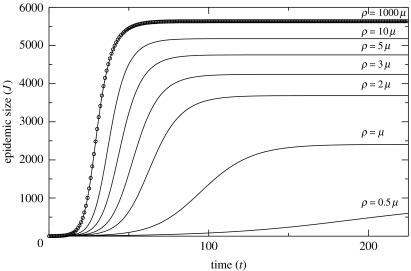

Figure 1 demonstrates the convergence of the NE model to the corresponding mass-action model for a Poisson degree distribution (r=μ=0.2, z=1.5). The circles indicate the solution to the mass-action model (equations (2.22) and (2.23)). We observe that the convergence is quite rapid as ρ is increased in the multiples of μ. This supports the common assumption that the mass-action model is a reasonable approximation for populations marked by many short-duration contacts.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of the NE model (solid lines, table 4) are compared for several values of the mixing rate (ρ) with an analogous mass-action model (circles, equations (2.22) and (2.23)). The degree distribution is Poisson (z=1.5) and r=μ=0.2.

3. Stochastic simulations

To test the NE model, we compare its predictions to stochastic simulations of an analogous epidemic process in networks. We first generate semi-random networks using the configuration model (Molloy & Reed 1995). The epidemic simulations then proceed as follows:

One node is selected uniformly at random from the population to be patient zero, the first infected individual.

Each contact has an exchange time drawn from an exponential distribution (parameter ρ). This time is added to a queue.

When a node v is infected at time t, a time of infection is drawn from an exponential distribution (parameter r) for each contact such that v is ego. The time is added to a queue.

When a node v is infected at time t, a time of recovery is drawn from an exponential distribution (parameter μ) and is assigned to v. The time is added to a queue.

When is the earliest time in the queue, an edge swap is performed, as per equation (2.1). The first edge involved in the swap corresponds to the contact a. The second edge is selected by choosing a unique element out of all edges uniformly at random. Then a new time is drawn and added to the queue.

When is the earliest time in the queue, a transmission event will occur, providing v has not recovered. Node v transmits to whatever node is occupying the position of alter at that time, causing alter to change state to if currently susceptible. If a transmission event occurs, a new time is drawn and added to the queue.

When is the earliest time in the queue, the corresponding node v enters a recovered state such that any transmission event with v=ego is removed from the queue.

This process continues until there are no more transmission events in the queue.

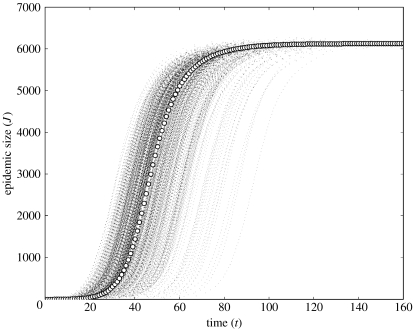

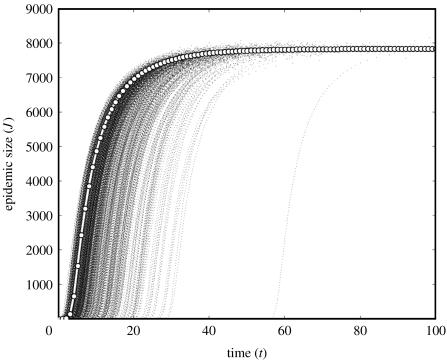

Figures 2 and 3 show a comparison of 1000 stochastic simulations to the solution of the NE–SIR equations for two concurrent degree distributions:

Poisson. , . This is generated by .

Power law with cut-off. , . This is generated by .

Figure 2.

One-thousand stochastic simulations (small dots) are compared with the predicted trajectory of a NE epidemic (large dots) in a Poisson network (z=1.5). r=0.2, μ=0.1 and ρ=0.25.

Figure 3.

One-thousand stochastic simulations (small dots) are compared with the predicted trajectory of a NE epidemic (large dots) in a power-law network (α=2.1, κ=75). r=0.2, μ=0.1 and ρ=0.20.

Figure 2 depicts epidemics on a network with a Poisson degree distribution () and parameters r=0.2, μ=0.1 and ρ=0.25. Figure 3 shows epidemics on a network with a power-law degree distribution (α=2.1, κ=75) and parameters r=0.2, μ=0.1 and . The deterministic NE model (table 4) predicts a trajectory that passes through the central-most region of the swarm of simulation trajectories and shows good agreement with the final size. There is nevertheless a great deal of variability among the simulation trajectories in terms of the onset of the expansion phase—the point in time when the epidemic increases at its maximal rate. At the onset of expansion phase, all trajectories are more or less similar, in agreement with the NE model.

In contrast to the homogeneous Poisson network, the power law gives an almost immediate expansion phase. This can be understood by noting that the hazard of infection is proportional to pI, and initially

| (3.1) |

There is a ratio of PGFs in equation (3.1)

This is approximately the ratio of the second moment to the first moment of the degree distribution, which for the power-law approaches infinity as the cut-off κ→∞. Because the ratio is very large, power-law networks have almost immediate expansion phase (Pastor-Satorras & Vespignani 2001a,b; Boguna et al. 2003; Barthélemy et al. 2005).

4. Application of the NE model to syphilis outbreak among Atlanta adolescents

We next implement the NE model using link-tracing data from a 1996 outbreak of syphilis among Atlanta adolescents. Sexual network data typically report contact time, duration of a contact and frequency of interaction. Most network models do not take into account the serial aspect of sexual contacts and instead assume that all contacts reported in a survey are constant over the duration of an epidemic or infectious period. Here, we illustrate that the dynamic SIR network model (table 4) can explicitly capture the transitory nature of sexual contact patterns. Owing to data limitations and uncertainty around syphilis infection rates, the NE model cannot describe this particular epidemic with much fidelity. Instead, this section is simply intended to demonstrate the straightforward application of the NE model to public health data.

We use public health data from an outbreak of syphilis within an adolescent community centred on an Atlanta high school (Rothenberg et al. 1998). Initially, several adolescents diagnosed with syphilis were interviewed by epidemiologists. The sexual contacts of these respondents were then traced and interviewed. In all, 34 people were interviewed and 204 contacts were traced. Each interviewee named his/her sexual contacts and listed the date of first and last interaction with each contact.

The complexity of syphilis transmission dynamics (Garnett et al. 1997) and the small size of our dataset make modelling the 1996 outbreak difficult. Thus, our analysis suffers from significant uncertainty in the estimated rates and parameters, particularly the transmission and recovery rates. We offer an additional caveat that recovery from syphilis does not provide lifelong immunity; yet our model does not allow recovered individuals to return to the susceptible state. We believe that this is appropriate in so far as the transition from the infected state back to the susceptible state occurs at a low rate relative to the spread of this particular outbreak. In practice, immunity is very long due to treatment and behavioural change, such that fast-spreading epidemics can be considered in isolation without including recovery or birth into the population (Grassly et al. 2005).

We estimate the relevant parameters using equations given in the electronic supplementary material and in Heckathorn (2002), Salganik & Heckathorn (2004) and Volz & Heckathorn (in press). In brief, a typical syphilis infection can last about a year if left untreated, and a typical infectious period will last 154 days on average (Jones 2005). A convenient estimate of the recovery rate is then . This estimate ignores many features of the pathology of syphilis for mathematical convenience, such as different probabilities of recovery at different stages of the infectious period (Garnett et al. 1997). There are diverse estimates for the transmissibility of syphilis, ranging from 9.2 to 63% per partner (Garnett et al. 1997). The estimate of 63% was selected as the most credible by the authors in Garnett et al. (1997).

Using the contact durations reported in the Atlanta study, we estimate the mixing rate of the population to be (electronic supplementary material). We then use the reported numbers of contacts to estimate , the average number of concurrent contacts for each individual in the sample. The degree distribution pk can then be estimated (electronic supplementary material, Heckathorn 2002; Salganik & Heckathorn 2004; Volz & Heckathorn in press) from the sequence , which is well fit by a power law with exponent α=−2.66. For the power-law fit, . An exponential distribution provided a worse fit to the data with . We assume the estimated degree distribution in the following analysis.

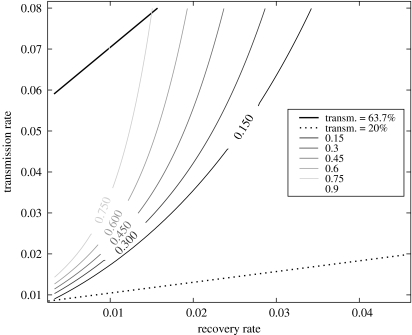

Figure 4 shows the final size of an outbreak as predicted by the NE model over a broad range transmission and recovery rates. The straight contours correspond to the ratio of r to μ that yields a transmissibility τ=0.637 and 0.20. Unfortunately, altering the transmissibility within this plausible range can yield any final size from almost 0 to 100%. From our sample, we can estimate the epidemic prevalence as 35%. We conclude that the NE model is consistent with the observed outbreak; however, this does not constitute a critical test of the suitability of the NE model to this outbreak.

Figure 4.

The final epidemic size as predicted by the NE model (table 4) is shown with respect to the transmission rate r and recovery rate μ for the Atlanta syphilis data. Contours are also provided for τ=0.637 and 0.20.

5. Discussion

Human contact patterns are characterized by heterogeneous number of transitory contacts. If contacts change at a rate that is slow relative to the rate of epidemic propagation, then static network approximations such as those based on bond percolation (Callaway et al. 2000; Newman 2002a; Meyers et al. 2005, 2006) may be appropriate. Alternatively, if contacts have very short duration relative to epidemic dynamics, then static network approximations break down and a mass-action model is more appropriate (equations (2.22) and (2.23)). In between these extremes, contacts are neither fixed nor instantaneous, and accurate epidemiological forecasting requires models that explicitly capture their dynamics, such as the NE model developed here. In fact, by changing a single parameter (the mixing rate), the NE model crosses the spectrum of models from static network to mass action.

The NE model is particularly useful for building models from link-tracing data. For many datasets, standard mass-action models do not adequately capture the finite number and extended duration of contacts, whereas static network models ignore the transitory and serial nature of contacts. Using the example of a 1996 syphilis outbreak in an adolescent population, we showed that the NE model can be easily fit to sexual contact data and then used to explore the epidemiological implications of host population structure.

In the limit of large mixing rate, the NE model becomes a simple (low-dimensional) mass-action model (equations (2.22) and (2.23)) that captures SIR dynamics in populations with arbitrary heterogeneity of contact rates. It reduces to the standard mass-action model when one assumes that all individuals have the same number of contacts. The mass-action model could potentially find wide utility in populations that are heterogeneous with respect to contact rates, infectiousness or susceptibility, specifically for modelling highly contagious diseases (such that brief contacts lead to transmission) or slow-propagating infectious diseases (such as many STDs); in either case, epidemic propagation is slow relative to the turnover in contacts.

We check our mathematical results using simulations that model continuous-time stochastic processes (both social and epidemiological) and take into account the finite size and heterogeneity of the population (§3). We wish to highlight our specific simulation techniques as an interesting alternative to the commonly used chain-binomial simulation (Daley et al. 2001).

The NE model offers a flexible starting point for analysing epidemiological processes in dynamic networks. Although we have started by analysing a simple category of dynamic random network, it should be fairly straightforward to extend the model to populations with simple spatial heterogeneity or assortative mixing by type (Newman 2003). Indeed, similar methods for static networks have recently been extended to directed networks, networks with assortativity, and affiliation structure (Newman 2002b; Meyers & Newman 2003; Meyers et al. 2006). It is probable that these, and other extensions, can be made to the NE model.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Richard Rothenberg for providing the Atlanta dataset and useful comments. L.A.M. acknowledges grant support from the James S. McDonnell Foundation.

Supplementary Material

Derivations and comparison of NE to related models

References

- Adimora A.A, Schoenbach V.J, Doherty I.A. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: sexual networks and social context. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2006;33:S39–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann M. Susceptible–infected–removed epidemic models with dynamic partnerships. J. Math. Biol. 1995;33:661–675. doi: 10.1007/BF00298647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann M. The deterministic limit of infectious disease models with dynamic partners. Math. Biosci. 1998;150:153–175. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(98)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R, May R. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1991. Infectious diseases of humans: dynamics and control. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson H. Limit theorems for a random graph epidemic model. Ann. Appl. Probab. 1998;8:1331–1349. doi: 10.1214/aoap/1028903384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barthélemy M, Barrat A, Pastor-Satorras R, Vespignani A. Dynamical patterns of epidemic outbreaks in complex heterogeneous networks. J. Theor. Biol. 2005;235:275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauch C. A versatile ODE approximation to a network model for the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. J. Math. Biol. 2002;45:375–395. doi: 10.1007/s002850200153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boguna M, Pastor-Satorras R, Vespignani A. Epidemic spreading in complex networks with degree correlations. In: Pastor-Satorras R, Rubi M, Diaz-Guilera A, editors. Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Lecture Notes in Physics. vol. 625. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2003. pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway D.S, Newman M.E.J, Strogatz S.H, Watts D.J. Network robustness and fragility: percolation on random graphs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;85:5468–5471. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.5468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chick S.E, Adams A.L, Koopman J.S. Analysis and simulation of a stochastic, discrete-individual model of STD transmission with partnership concurrency. Math. Biosci. 2000;166:45–68. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(00)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley D, Gani J, Gani J. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. Epidemic modelling: an introduction. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann O, Heesterbeek J. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2000. Mathematical epidemiology of infectious diseases. Model building, analysis and interpretation. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz K. On the transmission dynamics of HIV. Math. Biosci. 1988;90:397–414. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(88)90077-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty I.A, Shiboski S, Ellen J.M, Adimora A.A, Padian N.S. Sexual bridging socially and over time: a simulation model exploring the relative effects of mixing and concurrency on viral sexually transmitted infection transmission. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2006;33:368–373. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000194586.66409.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eames K.T.D, Keeling M.J. Modeling dynamic and network heterogeneities in the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:13 330–13 335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202244299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eames K.T.D, Keeling M.J. Monogamous networks and the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. Math. Biosci. 2004;189:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans T.S, Plato A.D.K. Exact solution for the time evolution of network rewiring models. Phys. Rev. E. 2007;75:056101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.056101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson N.M, Garnett G.P. More realistic models of sexually transmitted disease transmission dynamics: sexual partnership networks, pair models, and moment closure. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2000;27:600–609. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkenstadt B, Grenfell B. Empirical determinants of measles metapopulation dynamics in England and Wales. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1998;265:211–220. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Sohn W, Lepkowski J. American adolescents: sexual mixing patterns, bridge partners, and concurrency. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2002;29:13–19. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett G.P, Aral S.O, Hoyle D.V, Cates W, Jr, Anderson R.M. The natural history of syphilis: implications for the transmission dynamics and control of infection. Sex. Transm. Dis. 1997;24:185–200. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassly N.C, Fraser C, Garnett G.P. Host immunity and synchronized epidemics of syphilis across the United States. Nature. 2005;433:417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature03072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenfell B.T, Bjørnstad O.N, Kappey J. Travelling waves and spatial hierarchies in measles epidemics. Nature. 2001;414:716–723. doi: 10.1038/414716a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Anderson R, May R. Networks of sexual contacts: implications for the pattern of spread of HIV. AIDS. 1989;3:807–817. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198912000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn D. Respondent-driven sampling ii: deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc. Probl. 2002;49:11–34. doi: 10.1525/sp.2002.49.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holme P, Zhao J. Exploring the assortativity-clustering space of a network's degree sequence. Phys. Rev. E. 2007;75:046111. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.046111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. 2005 Analysis of a syphilis outbreak through the lens of percolation theory. Master's thesis, University of Texas-Austin.

- Liljeros F, Edling C.R, Amaral L.A, Stanley H.E, Åberg Y. The web of human sexual contacts. Nature. 2001;411:907–908. doi: 10.1038/35082140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd A.L, May R.M. Spatial heterogeneity in epidemic models. J. Theoret. Biol. 1996;179:1–11. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhart L.E, Aral S.O, Holmes K.K, Foxman B. Sex partner concurrency: measurement, prevalence, and correlates among urban 18–39-year-olds. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2002;29:133–143. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslov S, Sneppen K. Specificity and stability in topology of protein networks. Science. 2002;296:910–913. doi: 10.1126/science.1065103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers L.A, Newman M.E.J. Applying network theory to epidemics: control measures for mycoplasma pneumoniae outbreaks. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003;9:204. doi: 10.3201/eid0902.020188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers L.A, Pourbohloul B, Newman M.E.J, Skowronski D.M, Brunham R.C. Network theory and SARS: predicting outbreak diversity. J. Theor. Biol. 2005;232:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers L.A, Newman M.E.J, Pourbohloul B. Predicting epidemics on directed contact networks. J. Theor. Biol. 2006;240:400–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy M, Reed B. A critical point for random graphs with a given degree sequence. Random Struct. Algorit. 1995;6:161. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy M, Reed B. The size of the giant component of a random graph with a given degree sequence. Combin. Probab. Comput. 1998;7:295–305. doi: 10.1017/S0963548398003526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M.E.J. The spread of epidemic disease on networks. Phys. Rev. E. 2002a;66:016128. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.66.016128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M.E.J. Assortative mixing in networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002b;89:208701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.208701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M.E.J. Mixing patterns in networks. Phys. Rev. E. 2003;67:026 126. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.67.026126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M.E.J, Watts D.J, Strogatz S.H. Random graph models of social networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:2566–2572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012582999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor-Satorras R, Vespignani A. Epidemic spreading in scale-free networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001a;86:3200–3203. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor-Satorras R, Vespignani A. Epidemic dynamics and endemic states in complex networks. Phys. Rev. E. 2001b;63:066117. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.63.066117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. John Murray; London, UK: 1910. The prevention of malaria. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg R, Sterk C, Toomey K, Potterat J, Johnson D, Schrader M, Hatch S. Using social network and ethnographic tools to evaluate syphilis transmission. Sex. Transm. Dis. 1998;25:154–160. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199803000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salganik M.J, Heckathorn D.D. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 2004;34:193–240. doi: 10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strogatz S.H. Exploring complex networks. Nature. 2001;410:268–276. doi: 10.1038/35065725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Driessche P, Watmough J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 2002;180:29–48. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz E. SIR dynamics in random networks with heterogeneous connectivity. J.math. Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00285-007-0116-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz, E. & Heckathorn, D. In press. Probability based estimation theory for respondent driven sampling. J. Official Statistics.

- Watts C.H, May R.M. The influence of concurrent partnerships on the dynamics of HIV/AIDS. Math. Biosci. 1992;108:89–104. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(92)90006-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts D.J, Strogatz S.H. Collective dynamics of small-world networks. Nature. 1998;393:409–410. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts D.J, Muhamad R, Medina D.C, Dodds P.S. Multiscale, resurgent epidemics in a hierarchical metapopulation model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11 157–11 162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501226102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Derivations and comparison of NE to related models