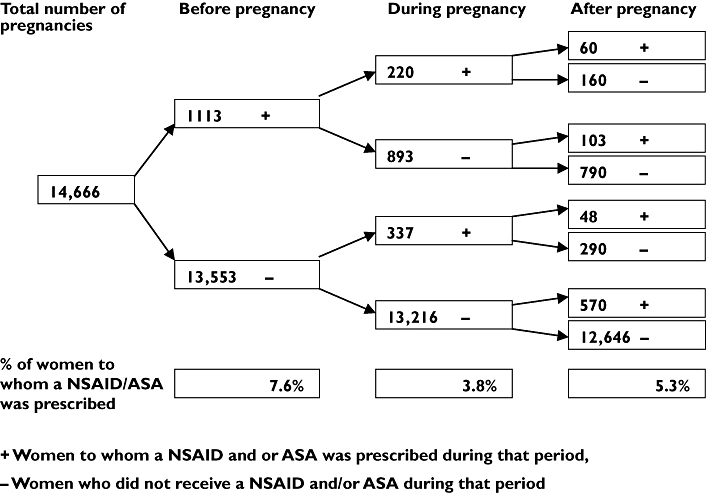

In 2005, a warning based on epidemiological studies describing associations between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) use in early pregnancy and risks of miscarriages, cardiac malformations and gastroschisis [1], was given by European registration authorities (e.g. the Dutch). NSAIDs and ASA should not be used during the first trimesters of pregnancy except when this is strictly indicated. We describe to what extent NSAIDs and ASA were prescribed during pregnancy in the Netherlands before this warning. We performed our study by using pharmacy dispensing data from IADB.nl (population-based database) in Northern and Eastern Netherlands. This database comprises all prescription drugs, excluding drugs dispensed during hospitalizations and over the counter (OTC)-drugs. Date of birth and gender of each patient are available and all patients have an unique anonymous identifier. The pregnancy-IADB.nl (1995–2004) was extracted from the main IADB.nl-database. Children were selected by date of birth and by using an address code the mother of this child was identified. With this method, which is described in detail by Schirm et al.[2], approximately 65% of the children could be linked to their mother and validation showed 99% correctness. Only live-born children are registered in this database. Gestational age is calculated for every mother by subtracting 273 days (three trimesters of 91 days, approximately 9 months) from day of birth of the child. This period will be considered as gestation and is per definition 273 days. Prevalence, calculated before, during and after pregnancy, is based on exposure rate. Exposure rate is defined as the number of pregnancies in which, in theory, a women has availability to a drug or class of drugs, i.e. those who received a prescription in one trimester which was extended into the next, are counted for both trimesters in which they had access to the drug. We identified 14 666 pregnancies from which we had information of a defined time window of 3 months before gestation till 3 months after delivery. NSAIDs (ATC-code: M01A) and/or ASA (ATC-code: N02BA) were prescribed during this defined time window to 2020 women (13.8%). In 7.6% (1113/14 666) of the pregnancies these drugs were prescribed before conception, in 3.8% (557/14 666) during gestation and in 5.3% (781/14 666) after pregnancy (Figure 1). Ninety-six % of the women received NSAIDs (mainly diclofenac, ibuprofen and naproxen), less than 5.5% received ASA and approximately 1.5% received both drugs. Average age at time of delivery of women receiving NSAIDs and/or ASA (29.74 years, range 16–49) did not differ from those not receiving these drugs (29.91 years, P = 0.077 (Student's t-test).

Figure 1.

Number of pregnancies in which a NSAID and/or ASA was prescribed before, during and after pregnancy

In the majority of the pregnancies (75.6%, 421/557) NSAIDs and/or ASA were prescribed during the first trimester, resulting in an overall first trimester exposure of 2.9%. International studies from Canada [3], Denmark [4] and Sweden [5], reporting on first trimester NSAID use/prescribing showed comparable results: 2.9%, 3% and 3.4%, respectively. Third trimester prescribing of NSAIDs and/or ASA was low (0.6%, n = 94) which was to be expected due to guidelines stating not to prescribe these drugs during the third trimester. Part of the first trimester exposure will be due to unawareness of pregnancy by the women. By using a standardized gestational age to determine drug prescribing, misclassification especially in the first trimester of pregnancy will be introduced, leading to overestimation of actual use. On the other hand, our data lack information about OTC-use which will lead to underestimate of actual use. Unpublished data of EUROCAT-registration Northern-Netherlands showed that NSAID exposure in pregnancy was due to 60% on prescription and 35% OTC. We do realize these data represent prescribing of NSAIDs and/or ASA before the warning from European authorities. However, we strongly recommend that prescribing physicians need to be careful in prescribingthese drugs to women of fertile age, especially when use of these drugs during pregnancy increases risks of miscarriages and birth defects. Whether this warning will result in less prescribing of NSAIDs and/or ASA, especially during the first trimester, has to be examined in future research, national as well as international.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank EUROCAT-registration Northern-Netherlands for their data.

References

- 1.Wording of the SPC of ASA and NSAIDs (April 2004). [14 2 2006]. http://www.cbg-meb.nl/nl/docs/nieuws/art-asa-nsaid-spc-pregnancy.pdf.

- 2.Schirm E, Tobi H, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Identifying parents in pharmacy data: a tool for the continuous monitoring of drug exposure to unborn children. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:737–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2002.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ofori B, Oraichi D, Blais L, Rey E, Berard A. Risk of congenital anomalies in pregnant users of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a nested case-control study. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2006;77:268–79. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olesen C, Steffensen FH, Nielsen GL, de Jong-van den Berg Olsen J, Sorensen HT. Drug use in first pregnancy and lactation: a population-based survey among Danish women. The EUROMAP Group. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;55:139–44. doi: 10.1007/s002280050608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ericson A, Kallen BA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in early pregnancy. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15:371–5. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(01)00137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]