Abstract

Aim

Therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors is common after myocardial infarction (MI). Given the lack of randomized trials comparing different ACE inhibitors, the association among ACE inhibitors after MI in risk for mortality and reinfarction was studied.

Methods

Patients hospitalized with first-time MI (n = 16 068) between 1995 and 2002, who survived at least 30 days after discharge and claimed at least one prescription of ACE inhibitor, were identified using nationwide administrative registries in Denmark.

Results

Adjusted Cox regression analysis demonstrated no differences in risk for all-cause mortality, but patients using captopril had higher risk of reinfarction (hazard ratio 1.18, 95% confidence interval 1.05, 1.34). However, following adjustment for differences in used dosages, all ACE inhibitors had similar clinical efficacy. Risk of all-cause mortality: trandolapril (reference) 1.00, ramipril 0.97 (0.89, 1.05), enalapril 1.04 (0.95, 1.150), captopril 0.95 (0.83, 1.08), perindopril 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) and other ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) 1.06 (0.94, 1.19). Reinfarction: trandolapril (reference) 1.00, ramipril 0.98 (0.89, 1.08), enalapril 1.04 (0.92, 1.17), captopril 1.05 (0.89, 1.25), perindopril 0.96 (0.81, 1.14) and other ACE inhibitors or ARB 0.99 (0.86, 1.14). Furthermore, the association between ARBs and clinical events was similar to ACE inhibitors (trandolapril reference): all-cause mortality 0.99 (0.84, 1.16) and recurrent MI 0.99 (0.83, 1.19).

Conclusions

Our results suggest a class effect among ACE inhibitors when used in comparable dosages. Focus on treatment at the recommended dosage is therefore most important, and not which ACE inhibitor is used.

What is already known about this subject

Treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor benefits many patients with cardiovascular disease.

ACE inhibitors are generally assumed to be equally effective, but this has never been fully verified in clinical trials.

What this study adds

Studying the association among ACE inhibitors after myocardial infarction demonstrated similarity in clinical outcome and supports a dosage–response relationship.

Therefore, for long-term benefits for patients who need treatment with an ACE inhibitor, a focus of treatment at the recommended dosage is most important and not which ACE inhibitor is used.

Keywords: ACE inhibitors, acute myocardial infarction, drug treatment, secondary prevention

Introduction

Treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor benefits many patients with cardiovascular disease. ACE inhibitors are generally assumed to be equally effective and clinically interchangeable and are often used for indications in which evidence originates from a trial with another ACE inhibitor. Nevertheless, ACE inhibitors differ in chemical structure and pharmaceutical properties, and the clinical relevance of these differences has not been explored, apart from equal efficacy in lowering blood pressure when used at an appropriate dosage. After acute myocardial infarction (MI), ACE inhibitors have shown clinical efficacy against placebo [1–6], but few studies have compared ACE inhibitors [7] and none with clinically relevant end-points. Furthermore, recent clinical trials have raised further questions regarding the concept of class effect after demonstrating conflicting results on the effect of ACE inhibitors among patients at high risk of complications from coronary artery disease but with no evidence of heart failure [8–10]. More studies are therefore needed to determine whether all ACE inhibitors are equally effective in treating patients with manifest atherosclerosis.

This study analysed the risk of death or recurrent MI among 16 068 patients treated with ACE inhibitors after first hospitalization for MI between 1995 and 2002 by individual-level linkage of nationwide administrative registries.

Methods

Population

All patients aged ≥30 years hospitalized with first-time MI [International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) code I21–I22] between 1995 and 2002 who were alive 30 days after discharge were identified using the National Patient Registry, a nationwide registry of all hospitalizations in Denmark since 1978. The first diagnosis of MI was defined as having no hospital admission for MI the previous 17 years in the National Patient Registry. We used 17 years because that was the maximum time patients admitted in 1995 could be traced back. The diagnosis of MI in the National Hospital Registry has been proved to be highly valid, with a sensitivity of 91% and positive predictive value of 93% [11]. The selection procedures and baseline characteristics of the study population have been described in detail [12]. All patients were identified who had claimed at least one prescription of an ACE inhibitor [ATC code C09, including angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARB)] from pharmacies within 30 days after discharge by linkage on the individual level with the Danish Registry of Medicinal Product Statistics. This Registry has been found to be highly accurate and has been described in detail [13, 14]. Information about the patient's vital status (dead or alive) at the end of December 2002 was obtained from the Civil Registration System through Statistics Denmark.

Comorbidity

Because comorbidity is a potential confounder for the decision to initiate secondary preventive medication and influences outcome, the Ontario AMI mortality prediction rule was used to define comorbidity [15]. Comorbidity diagnoses at the index admission were identified and the comorbidity index was further enhanced by identifying diagnoses from admissions up to 1 year before the index admission, as done by Rasmussen et al.[16]. The following comorbidity diagnoses were identified and included in the analysis: congestive heart failure, cardiogenic shock, pulmonary oedema, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, cardiac dysrhythmia, renal failure, malignancy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes mellitus with complications.

Exposure groups and dosages

Patients were categorized into exposure groups depending on the ACE inhibitor used at first prescription claim: trandolapril, ramipril, enalapril, captopril and perindopril, the most frequently prescribed agents. Other ACE inhibitors and ARBs were grouped as ACEi/ARB, while patients using only ARBs were compared with patients using ACE inhibitors in subsequently analysis. To avoid selection bias, patients switching agent were not excluded from the primary analysis, but patients who did not switch agent were compared in later sensitivity analysis. The average daily dosage was calculated as the median dosage used for each patient throughout the period of observation, which has been described previously [17].

End-points

The predefined end-points of interest were mortality due to all causes and readmission due to recurrent MI.

Statistical analysis

Unadjusted mortality for the exposure groups was summarized by Kaplan–Meier curves and compared using the log rank test. Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare the effect of different ACE inhibitors on end-points, using trandolapril as reference. The models were adjusted for time [calendar year of index MI (1995–96 as reference)], age (30–59 years as reference), gender (women as reference), comorbidity (no comorbidity as reference) and concomitant pharmaceutical treatment (none as reference). Model assumptions – linearity of continuous variables, the proportional hazard assumption and lack of interactions – were tested and found valid unless otherwise indicated. Patients were censored at the end of the study period (31 December 2002) and those with missing information or lost to follow-up (n = 16) were censored at the time of disappearance. All statistical calculations were performed using the SAS statistical software package, version 9.1 for UNIX servers (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics

The Danish Data Protection Agency approved this study, and data were made available to us in a form such that individuals could not be identified. Retrospective registry-based studies do not require ethical approval in Denmark.

Results

Between 1995 and 2002, 71 515 patients were hospitalized with first-time MI, of whom 55 315 (77.3%) were alive 30 days after discharge. The 16 068 patients (34.5%) who claimed at least one prescription of an ACE inhibitor from a pharmacy within 30 days from discharge were included. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study sample.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 16 068 patients surviving first-time hospitalization with acute myocardial infarction who claimed at least one prescription for an ACE inhibitor within 30 days after discharge

| Characteristic | Trandolapril | Ramipril | Enalapril | Captopril | Perindopril | ACEi/ARB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 4777 | 4771 | 2027 | 1895 | 1110 | 1488 |

| Mean age (±SD, years) | 68.7 (±12.2) | 67.1 (±11.9) | 68.9 (±11.7) | 68.4 (±11.8) | 68.4 (±12.9) | 68.5 (±11.7) |

| Women, n (%) | 1727 (36.2) | 1566 (32.8) | 755 (37.2) | 687 (36.3) | 410 (36.9) | 610 (41.0) |

| Median dosage (mg) | 2.00 | 5.00 | 10.00 | 37.50 | 4.00 | NA |

| % of total in 1995 | 11.3 | 20.7 | 24.0 | 32.7 | 2.2 | 9.1 |

| % of total in 2002 | 30.6 | 36.5 | 6.9 | 1.1 | 15.8 | 9.1 |

| Baseline comorbidity (%) | ||||||

| Congestive heart failure | 19.9 | 19.3 | 20.1 | 24.2 | 25.3 | 17.6 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4.1 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 4.1 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmia | 9.2 | 9.9 | 10.6 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 9.1 |

| Pulmonary oedema | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Acute kidney failure | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| Malignant condition | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4.9 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 4.9 | 8.1 | 6.3 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| Diabetes with complications | 4.1 | 4.4 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 5.4 |

| Concomitant treatment (%) | ||||||

| β-Blockers* | 62.2 | 71.3 | 50.5 | 45.7 | 71.9 | 59.0 |

| Statins† | 39.6 | 45.7 | 23.7 | 16.8 | 43.8 | 37.4 |

| Loop-diuretics‡ | 53.9 | 52.9 | 59.5 | 65.5 | 55.1 | 46.4 |

| Antidiabetics‡ | 12.7 | 13.3 | 18.7 | 16.7 | 13.7 | 15.9 |

SD, Standard deviation; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; NA, not applicable.

At least one prescription claimed within 90 days after discharge.

At least one prescription claimed within 180 days after discharge.

At least one prescription claimed between 90 days before admission and 90 days after discharge.

Trandolapril and ramipril were the agents most frequently used, each accounting for 30% of all ACE inhibitors, followed by enalapril (13%), captopril (12%), ACEi/ARB (9%) and perindopril (7%). During the study period, the prescription pattern changed, with the use of enalapril and captopril declining steadily and the use of trandolapril, ramipril and perindopril increasing. The average daily dosages for patients using trandolapril, ramipril, enalapril and perindopril, respectively, were 2, 5, 10 and 4 mg, whereas the average dosage for patients using captopril was only 37.5 mg. The mean follow-up was 2.8 years since discharge (±2.1 SD). Patients using ramipril were slightly younger and more frequently men. Those using perindopril had more baseline comorbidity (congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) in general, with no other major differences among the exposure groups. Patients using trandolapril, ramipril and perindopril had more concomitant use of β-blockers and statins, due to time-dependent trends in the use of these medications, and were using fewer loop-diuretics and antidiabetic agents than patients receiving enalapril and captopril.

All-cause mortality

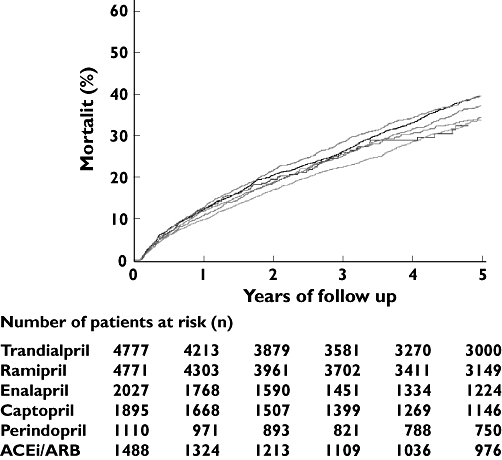

From 1995 to 2002, 4349 people in the cohort died from all causes. Figure 1 illustrates that unadjusted mortality curves across exposure groups differed (P < 0.001). However, after adjustment for confounders (gender, age, year of MI, comorbidity and concomitant pharmaceutical treatment), all-cause mortality did not differ significantly among the six exposure groups (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier curves for mortality according to different angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (exposure groups) among patients who claimed a prescription for an ACE inhibitor within 30 days from discharge after myocardial infarction

Table 2.

Hazard ratios using multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis, adjusted for calendar year of index MI, age, gender, comorbidity and concomitant pharmaceutical treatment and 95% confidence interval (CI) for all-cause mortality and recurrent MI

| Variable Exposure group | All-cause mortality Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Recurrent MI Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Trandolapril* | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Ramipril | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.08) |

| Enalapril | 1.04 (0.95, 1.15) | 1.04 (0.92, 1.17) |

| Captopril | 1.02 (0.93, 1.12) | 1.18 (1.05, 1.34) |

| Perindopril | 0.99 (0.84, 1.14) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.14) |

| ACEi/ARB | 1.05 (0.94, 1.18) | 0.99 (0.86, 1.14) |

Reference. MI, Myocardial infarction; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Recurrent MI

A total of 2932 patients were readmitted with recurrent MI during the study period. Table 2 illustrates that patients using captopril had significantly higher hazard ratios (HR) for readmission due to recurrent MI (1.18, 95% confidence interval 1.05, 1.34).

Clinical efficacy among patients using ACE inhibitors in comparable dosages and among those who did not switch agent

Patients using ACE inhibitors in comparable dosages [average dosage 50% of recommended dosage (n = 14 933)] were compared in additional Cox multivariable proportional hazard analysis. A total of 833 patients used captopril at an average daily dosage of 75 mg and were compared with patients from the other exposure groups who initially used ACE inhibitors at an average dosage of 50% of recommendations. With trandolapril as reference, the HRs across exposure groups did not differ significantly for all-cause mortality and recurrent MI (Table 3). After 3 years' follow-up, some cross-over between the ACE inhibitors used was observed, highest for patients using captopril (28%) and lowest for patients using trandolapril (13%). Among patients not switching agent, from 0 to 365 days (n = 14 214) and from 0 days until the end of the study period (n = 13 022), no differences in clinical outcomes between the different exposure groups were found (data not shown).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios using multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis, adjusted for calendar year of index MI, age, gender, comorbidity and concomitant pharmaceutical treatment and 95% confidence interval (CI), for all-cause mortality and recurrent MI among patients using ACE inhibitors in comparable dosages (50% of the recommended dosage)

| Variable Exposure group | All-cause mortality Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Recurrent MI Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Trandolapril* | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Ramipril | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.08) |

| Enalapril | 1.04 (0.95, 1.15) | 1.04 (0.92, 1.17) |

| Captopril | 0.95 (0.83, 1.08) | 1.05 (0.89, 1.25) |

| Perindopril | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.14) |

| ACEi/ARB | 1.06 (0.94, 1.19) | 0.99 (0.86, 1.14) |

Reference. MI, Myocardial infarction; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker. Comparison of patients using captopril at an average daily dosage of 75 mg with patients from the other exposure groups who initially used ACE inhibitors at an average dosage of 50% of recommended dosage.

Angiotensin-II receptor blockers

A total of 800 (5%) patients used ARBs, who were mainly from the last part of the observational period. Earlier in 1995 only 15 (0.9%) patients used ARBs, but the number of users increased considerably to 185 (6.9%) in 2002. In Cox multivariable proportional hazard analysis, the association between use of ARBs and clinical events was similar to ACE inhibitors, using trandolapril as reference: all-cause mortality HR 0.99 (0.84, 1.16) and recurrent MI HR 0.99 (0.83, 1.19).

Discussion

This study compared ACE inhibitors after first-time MI and has the following main findings: (i) when used in comparable dosages, all the ACE inhibitors tested have similar clinical efficacy in reducing mortality and recurrent MI rates; (ii) used dosages in healthcare are low compared with clinical trials, and in this study patients using captopril were the most underdosed; (iii) the dosage used appears to influence clinical efficacy, and using an appropriate dosage is thus important to achieve full benefits of treatment; (iv) the association between ARBs and clinical events was similar to ACE inhibitors. Given the lack of randomized comparisons of ACE inhibitors, this is the closest we can come to demonstrating a class effect of ACE inhibitors after MI.

Dosage and clinical efficacy

The dosages used were generally below those recommended (Table 1). For patients receiving trandolapril, ramipril, enalapril and perindopril the average dosages used after discharge were only 50% of those proven effective in randomized trials and recommended in international clinical guidelines [1, 5, 9, 18–20]. For patients using captopril, the average dosage was even lower, only 25% of that recommended [18, 21]. The study has demonstrated that the small differences in clinical efficacy were caused by more underdosing among patients using captopril and, consequently, that the different ACE inhibitors had similar clinical efficacy regarding all-cause mortality and reinfarction when used in comparable dosages. The results are consistent with previous data showing a small but significant difference in the efficacy of ACE inhibitors at a high dosage vs. low dosage among patients with heart failure [22]. In post-MI patients, these results emphasize that treatment at an appropriate dosage is also important, to obtain the full benefits of treatment when indicated for secondary prevention. Finally, we found that the association between use of ARBs and clinical events was similar to ACE inhibitors, a result consistent with general views [23–25]. Therefore, to add an economic benefit to patients and healthcare sectors, physicians could consider prescribing the cheapest ACE inhibitor or ARB after MI.

Compliance

We have previously demonstrated that long-term compliance with treatment with ACE inhibitors in our population is high [17]. We assume that the observed cross-over between the ACE inhibitors used during the study period represents time-dependent trends in treatment preferences, mainly with switching of agents used in the beginning of the study period.

Comparison with other studies

Whereas most studies have revealed that various ACE inhibitors significantly reduce mortality and morbidity, a discrepancy has recently been found in treatment of patients with or at high risk of ischaemic heart disease but without heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction. In the Heart Outcome Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study [8] and the European Trial on the Reduction of Cardiac Events with Perindopril in Stable Coronary Artery Disease (EUROPA) [9], patients receiving ramipril and perindopril, respectively, had lower mortality and morbidity rates than did patients treated with placebo. However, the Prevention of Events with Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibition (PEACE) trial did not find similar evidence in treatment with trandolapril [10]. These studies have raised many questions; one is whether the patient population in PEACE had a lower risk of cardiovascular complications. However, a substudy from EUROPA has recently demonstrated that the level of risk did not modify the treatment benefit with perindopril [26]. Another question still appears relevant; is trandolapril inferior to perindopril and ramipril? Our results make this very unlikely. Few trials have directly compared ACE inhibitors. In the PRACTICAL study, comparison of enalapril vs. captopril on left ventricular function and survival 3 months after MI demonstrated reduced 90-day and 1-year mortality among patients receiving enalapril [7]. In contrast, a prospective overview combining data from the TRAndolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE), acute infarction ramipril efficacy (AIRE) and Survival and Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) studies has demonstrated that ramipril, trandolapril and captopril have equal efficacy in reducing mortality [27]. Two studies in Canada comparing ACE inhibitors have also recently been published using methods comparable to this study. A study of older post-MI patients has associated ramipril with lower mortality compared with other ACE inhibitors [28], but patients with heart failure did not differ, suggesting a class effect [29]. Our study includes a far larger population, permitting exclusive division of exposure groups and further enabling a comparison of ACE inhibitors when used at comparable dosages.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this study are the large study cohort in an unselected patient population, the completeness of the data and the inclusion of nationwide data, including the prescription practice of all hospitals in Denmark. The MI diagnosis in the National Patient Registry has been validated before and has high sensitivity and specificity [11, 30], and the national prescription database has also been found to be highly accurate [31]. A comprehensive accumulation of nationwide admission data and linking to other registries is unique for Denmark. Although the system is based on registries from a single country, Denmark's health insurance system, which partly reimburses all patients for drug expenses, is typical of many affluent industrialized countries [32].

The main limitation is the nonrandomized nature of the study, but a trial comparing ACE inhibitors is very unlikely ever to be performed. Detailed information about important prognostic factors such as smoking and obesity cannot be obtained from administrative registries, and the control for comorbidity may be insufficient. Hidden biases, such as unidentified differences in risk among exposure groups, may influence the observations. One source of bias could be that certain ACE inhibitors may have been prescribed for a specific indication, probably illustrated by the slightly younger age of patients receiving ramipril, or that certain patients were admitted and later discharged from selected hospitals. The registries do not include information on contraindications for treatment, adverse reactions and allergies. Although patients claim prescriptions from a pharmacy, this may not measure exactly the intake of medicine: the period during which medicine is taken and the dosage used. Nevertheless, since the public health insurance system only partly reimburses drug expenses, we assume that patients claiming a prescription from a pharmacy intend to consume the medication as prescribed. Finally, this study did not analyse the efficacy of ACE inhibitors in the early treatment of MI, where different studies have demonstrated a small, but consistent, significant mortality benefit [2, 3, 6, 18, 33]. Even with these limitations, the study contributes to the general sense that ACE inhibitors have a class effect.

Conclusions

ACE inhibitors with varying pharmaceutical properties were associated with similar clinical outcome. For long-term benefits for MI patients who need treatment with an ACE inhibitor, a focus on initiating treatment and continuing treatment at the recommended dosage is therefore most important, and not which ACE inhibitor is used.

Acknowledgments

Competing interests: None declared.

Research grants from the Bispebjerg University Hospital Research Committee and the Research Council of Eastern Denmark supported this study. The study sponsors were not involved in the study design and analysis of the study, writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Authors contributions: all authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript. M.L.H.: Concept and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, responsible for writing the final version and decision on submission of manuscript. Acts as guarantor for the paper. G.H.G. and L.K.: Concept and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. T.K.S., F.F., P.B. and S.Z.A.: Interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. S.R. and M.M.: Statistical expertise, interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. C.T-P.: Concept and design of the study, interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content.

References

- 1.The Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators. Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. Lancet. 1993;342(8875):821–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'infarto Miocardico. GISSI-3: effects of lisinopril and transdermal glyceryl trinitrate singly and together on 6-week mortality and ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1994;343(8906):1115–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ISIS-4 (Fourth International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. ISIS-4: a randomised factorial trial assessing early oral captopril, oral mononitrate, and intravenous magnesium sulphate in 58,050 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1995;345(8951):669–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moye LA, Basta L, Brown EJ, Jr, Cuddy TE, Davis BR, Geltman EM, Goldman S, Flaker GC. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:669–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, Carlsen JE, Bagger H, Eliasen P, Lyngborg K, Videbaek J, Cole DS, Auclert L, Pauly NC. A clinical trial of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor trandolapril in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1670–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oral captopril versus placebo among 13 634 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction: interim report from the Chinese Cardiac Study (CCS-1) Lancet. 1995;345(8951):686–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foy SG, Crozier IG, Turner JG, Richards AM, Frampton CM, Nicholls MG, Ikram H. Comparison of enalapril versus captopril on left ventricular function and survival three months after acute myocardial infarction (the ‘PRACTICAL’ study) Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:1180–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:145–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox KM. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study) Lancet. 2003;362(9386):782–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braunwald E, Domanski MJ, Fowler SE, Geller NL, Gersh BJ, Hsia J, Pfeffer MA, Rice MM, Rosenberg YD, Rouleau JL. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition in stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2058–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madsen M, Davidsen M, Rasmussen S, Abildstrom SZ, Osler M. The validity of the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in routine statistics: a comparison of mortality and hospital discharge data with the Danish MONICA registry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:124–30. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gislason GH, Abildstrom SZ, Rasmussen JN, Rasmussen S, Buch P, Gustafsson I, Friberg J, Gadsboll N, Kober L, Stender S, Madsen M, Torp-Pedersen C. Nationwide trends in the prescription of beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors after myocardial infarction in Denmark, 1995–2002. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2005;39:42–9. doi: 10.1080/14017430510008989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaist D, Andersen M, Aarup AL, Hallas J, Gram LF. Use of sumatriptan in Denmark in 1994–5: an epidemiological analysis of nationwide prescription data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43:429–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaist D, Sorensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish prescription registries. Dan Med Bull. 1997;44:445–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackevicius CA, Anderson GM, Leiter L, Tu JV. Use of the statins in patients after acute myocardial infarction: does evidence change practice? Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:183–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen S, Zwisler AD, Abildstrom SZ, Madsen JK, Madsen M. Hospital variation in mortality after first acute myocardial infarction in Denmark from 1995 to 2002: lower short-term and 1-year mortality in high-volume and specialized hospitals. Med Care. 2005;43:970–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000178195.07110.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, Gadsboll N, Buch P, Friberg J, Rasmussen S, Kober L, Stender S, Madsen M, Torp-Pedersen C. Long-term compliance with beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1153–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez-Sendon J, Swedberg K, McMurray J, Tamargo J, Maggioni AP, Dargie H, Tendera M, Waagstein F, Kjekshus J, Lechat P, Torp-Pedersen C. Expert consensus document on angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. The Task Force on ACE-inhibitors of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1454–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohn JN, Johnson G, Ziesche S, Cobb F, Francis G, Tristani F, Smith R, Dunkman WB, Loeb H, Wong M. A comparison of enalapril with hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate in the treatment of chronic congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:303–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yusuf S, Kostis JB, Pitt B. ACE inhibitors for myocardial infarction and unstable angina. Lancet. 1993;341(8848):829. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90604-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Packer M, Poole-Wilson PA, Armstrong PW, Cleland JG, Horowitz JD, Massie BM, Ryden L, Thygesen K, Uretsky BF. Comparative effects of low and high doses of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, lisinopril, on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure. ATLAS Study Group. Circulation. 1999;100:2312–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.23.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickstein K, Kjekshus J. Effects of losartan and captopril on mortality and morbidity in high-risk patients after acute myocardial infarction: the OPTIMAAL randomised trial. Optimal Trial in Myocardial Infarction with Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan. Lancet. 2002;360(9335):752–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09895-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Segal R, Martinez FA, Dickstein K, Camm AJ, Konstam MA, Riegger G, Klinger GH, Neaton J, Sharma D, Thiyagarajan B. Effect of losartan compared with captopril on mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure: randomised trial – the Losartan Heart Failure Survival Study ELITE II. Lancet. 2000;355(9215):1582–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJV, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau J-L, Kober L, Maggioni AP, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Van de Werf F, White H, Leimberger JD, Henis M, Edwards S, Zelenkofske S, Sellers MA, Califf RM the Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial Investigators. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1893–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deckers JW, Goedhart DM, Boersma E, Briggs A, Bertrand M, Ferrari R, Remme WJ, Fox K, Simoons ML. Treatment benefit by perindopril in patients with stable coronary artery disease at different levels of risk. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:796–801. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flather MD, Yusuf S, Kober L, Pfeffer M, Hall A, Murray G, Torp-Pedersen C, Ball S, Pogue J, Moye L, Braunwald E. Long-term ACE-inhibitor therapy in patients with heart failure or left-ventricular dysfunction: a systematic overview of data from individual patients. ACE-Inhibitor Myocardial Infarction Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;355(9215):1575–81. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pilote L, Abrahamowicz M, Rodrigues E, Eisenberg MJ, Rahme E. Mortality rates in elderly patients who take different angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors after acute myocardial infarction: a class effect? Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:102–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-2-200407200-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu K, Mamdani M, Kopp A, Lee D. Comparison of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in the treatment of congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:283–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abildstrom SZ, Rasmussen S, Madsen M. Changes in hospitalization rate and mortality after acute myocardial infarction in Denmark after diagnostic criteria and methods changed. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:990–5. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:105–16. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ess SM, Schneeweiss S, Szucs TD. European healthcare policies for controlling drug expenditure. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21:89–103. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200321020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van de Werf F, Ardissino D, Betriu A, Cokkinos DV, Falk E, Fox KA, Julian D, Lengyel M, Neumann FJ, Ruzyllo W, Thygesen C, Underwood SR, Vahanian A, Verheugt FW, Wijns W. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. The Task Force on the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:28–66. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00618-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]