Abstract

AIM

To investigate the pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy of intravenous (i.v.) and intramuscular (i.m.) lorazepam (LZP) in children with severe malaria and convulsions.

METHODS

Twenty-six children with severe malaria and convulsions lasting ≥5 min were studied. Fifteen children were given a single dose (0.1 mg kg−1) of i.v. LZP and 11 received a similar i.m. dose. Blood samples were collected over 72 h for determination of plasma LZP concentrations. Plasma LZP concentration–time data were fitted using compartmental models.

RESULTS

Median [95% confidence interval (CI)] LZP concentrations of 65.1 ng ml−1 (50.2, 107.0) and 41.4 ng ml−1 (22.0, 103.0) were attained within median (95% CI) times of 30 min (10, 40) and 25 min (20, 60) following i.v. and i.m. administration, respectively. Concentrations were maintained above the reported therapeutic concentration (30 ng ml−1) for at least 8 h after dosing via either route. The relative bioavailability of i.m. LZP was 89%. A single dose of LZP was effective for rapid termination of convulsions in all children and prevention of seizure recurrence for >72 h in 11 of 15 children (73%, i.v.) and 10 of 11 children (91%, i.m), without any clinically apparent respiratory depression or hypotension. Three children (12%) died.

CONCLUSION

Administration of LZP (0.1 mg kg−1) resulted in rapid achievement of plasma LZP concentrations within the reported effective therapeutic range without significant cardiorespiratory effects. I.m administration of LZP may be more practical in rural healthcare facilities in Africa, where venous access may not be feasible.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Lorazepam (LZP) may be a more useful anticonvulsant to stop convulsions in children with severe malaria (SM) than diazepam, since it has a longer duration of action and can be given by other routes, such as intramuscular (i.m.).

There are no studies describing both the pharmacoknetics and clinical efficacy of LZP in African children, particularly those with SM.

We have undertaken a study with LZP, administered either intravenously (i.v.) or i.m., to children with SM and convulsions in order to describe and compare the pharmacokinetic profiles of LZP following administration via both routes and determine whether the currently recommended dose of LZP (0.1 mg kg−1) is effective in terminating convulsions in this group.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Administration of LZP (i.v. or i.m.) at the currently recommended dose (0.1 mg kg−1) resulted in rapid achievement of plasma LZP concentrations within the reported effective therapeutic range without clinically significant cardiorespiratory effects.

A single dose of LZP was effective in the rapid termination of convulsions in all children, and prevention of seizure recurrence for >72 h in 11 of 15 (73%) children and 10 of 11 (91%) children after i.v. and i.m. administration, respectively.

Keywords: children, convulsions, lorazepam, malaria, pharmacokinetics

Introduction

Acute seizures are a frequent clinical feature of severe malaria (SM) and other infections in children [1]. Over 80% of children presenting to hospital with cerebral malaria have a history of seizures [2] and about 60% have clinical seizures after admission [1, 3]. Protracted and multiple convulsions are often refractory to treatment and are associated with an increased risk of death [4] and/or neurological and cognitive deficits among survivors [5, 6]. Therefore, early, prompt and effective termination and prevention of convulsions may improve outcome in children with SM. Furthermore, rapid and sustained seizure control may avert the need for multiple anticonvulsant administration and prolonged hospitalization.

The ideal drug for treating acute seizures and status epilepticus (SE) should: (i) enter the brain rapidly; (ii) have an immediate onset of anticonvulsant action; (iii) have minimal depression of consciousness or cardiorespiratory function; (iv) have a sustained duration of anticonvulsant action to prevent seizure recurrence; and (v) be easily and safely administered at peripheral healthcare facilities [7]. Benzodiazepines are considered the drugs of choice for rapid termination of acute seizures and SE [8]. In resource-poor countries, diazepam (DZ) is frequently used as the standard first-line treatment for acute convulsions and SE, as it is widely available, cheap and rapidly acting. However, it has several disadvantages. Gaining intravenous (i.v.) access is often technically difficult in most peripheral healthcare settings (with limited resources and healthcare personnel), particularly in young children who are having generalized tonic-clonic convulsions. Following i.v. administration, DZ is rapidly redistributed to lipoid tissues, and consequently, plasma concentrations rapidly decline with breakthrough seizures occurring when the concentrations fall below threshold levels [9]. Accordingly, repeated injections or continuous infusions are often required for sustained control of seizures. However, administration of multiple doses of DZ is undesirable, especially in children with SM, due to accumulation and increased risk of fatal respiratory depression [2, 10]. Moreover, rectal administration of DZ (which has been suggested as a practical alternative to i.v. administration under such settings) generally results in variable absorption, leading to rapid recurrence of seizures [9]. The intramuscular (i.m.) route, which is frequently used in such settings, is not suitable for administration of DZ for termination of acute seizures and SE, since it results in incomplete and erratic absorption [11].

Lorazepam (LZP) has several advantages over DZ. Lorazepam is less lipid-soluble than DZ and, following i.v. administration, it has a longer duration of anticonvulsant action (12–24 h) than predicted from its elimination half-life [12]. It prevents seizure recurrence for between 2 and 72 h [13] and can be used for both acute treatment and prophylaxis of seizures. It has potent anticonvulsant activity and is effective in management of SE in both adults [14–16] and children [17], including SE refractory to phenobarbital and phenytoin [18]. I.v. and intranasal LZP has been successfully used in acute seizures and SE in the emergency room for children [19, 20] and has been shown to be more effective than DZ for out-of-hospital treatment of SE in adults [21]. LZP may be associated with less respiratory depression than DZ [14, 17, 22–24].

To date, no studies have been reported describing both the pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy of LZP in African children, particularly those with SM. The pharmacokinetics of LZP may be altered in children, and a few concentration-dependent side-effects such as respiratory depression have been reported in infants and children [25, 26]. Children with SM may have compromised respiratory function and hypotension due to associated metabolic acidosis [27] and intracranial hypertension [28], which may be aggravated by LZP.

We have undertaken a study on LZP administered by either the i.v. or i.m. route to children with SM and convulsions in order to: (i) describe and compare the pharmacokinetic profiles of LZP following administration via both routes; (ii) determine whether the currently recommended dose of LZP (0.1 mg kg−1) is effective in terminating convulsions in this group; (iii) correlate LZP plasma concentrations with termination and recurrence of convulsions, and respiratory and cardiovascular parameters; and (iv) determine whether the i.m. route would provide a comparable bioavailability and pharmacokinetic profile with respect to the i.v. route.

Methods

Study site and study design

This was an open-label, nonrandomized, uncontrolled study. The Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Scientific Steering Committee, KEMRI/National Ethical Review Committee and the Research Ethics Committee (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool, UK) approved the study, which was conducted at the paediatric ward of the New Nyanza Provincial General Hospital (NNPGH), Kisumu (a town with a population of approximately 320 000 people) located on the shores of Lake Victoria in Western Kenya. The NNPGH, the main government tertiary referral hospital (400 beds), serves the entire western Kenya region. The hospital includes a 44-bed paediatric inpatient ward, which admits an average of 8000 children annually, of whom about 40% have falciparum malaria (B. R. Ogutu, personal communication). Government-employed and medically qualified clinical and nursing personnel provide inpatient paediatric medical care to children admitted to the paediatric unit, including the study participants. In addition, a qualified and experienced research nurse (trained in intensive care unit skills and with broad experience in paediatric care in a research setting) was primarily responsible for blood sample collection and close monitoring of the study participants.

Study participants

All children admitted to the NNPGH paediatric unit were eligible for the study if: (i) they were aged between 6 months and 13 years; (ii) they had signs of SM (prostration: unable to sit, drink or breast-feed, but conscious; respiratory distress, or deep (acidotic) breathing) [29, 30]; (iii) they had a convulsion lasting ≥5 min; and (iv) the child's parent(s)/guardian(s) gave written informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from the parents/guardians in a language of their choice, and children were recruited with intent to treat. Children were excluded if: (i) they had received DZ prior to admission to NNPGH (documented in referral case notes, or from the history of the current illness); (ii) informed consent could not be obtained from parents/guardians; and (iii) they had compromised cardiorespiratory function (which, in the opinion of the clinician attending to the child, could be exacerbated by a benzodiazepine). Children exited the study if informed consent was withdrawn or were excluded at the data analysis stage if LZP was detected in the baseline (predose) plasma sample.

Clinical care

All children admitted to the ward were assessed by a medically qualified member of the paediatric team. A clinical history was taken and complete physical examination performed on all children on admission. Venous access was obtained by fixing F.E.P. polymer cannulae (Ven-O-Lit®; MIGADA, Kiryat Shmona, Israel), one for i.v. fluids and drug administration and another (in the opposite arm) for blood sampling. A single blood sample (4 ml) was drawn for quantitative parasite count, blood culture and full haemogram. A portion of the blood (0.5 ml) was centrifuged (1500 g; 5 min) and the plasma stored at −20°C until assayed for baseline LZP concentrations.

All children received antimalarial treatment with quinine dihydrochloride (Lincoln Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Gandhinagar, India) as a loading dose (15 mg kg−1 diluted with 10 ml kg−1 of 5% dextrose saline) infused over 4 h, followed by a maintenance dose (10 mg kg−1 in 10 ml kg−1 5% dextrose saline) infused over 4 h every 8 hours [31], until the child could take oral drugs when antimalarial treatment was completed with first line antimalarial drugs. Other antimalarial drugs including artemisinin derivatives (dihydroartemisin) and amodiaquine were prescribed as required (at the discretion of the clinician attending the child). Severe anaemia (Hb ≤50 g l−1) was corrected with a blood transfusion (20 ml kg−1) infused over 4 h [32, 33]. All children were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics (chloramphenicol, 25 mg kg−1 6-hourly; and benzyl penicillin) as presumptive treatment for bacteraemia or meningitis [34, 35] until cerebrospinal fluid and blood culture results were available. Children with fever (temperature >38.5°C) were treated with paracetamol (15 mg kg−1) administered orally, exposure, and tepid sponging. Hypoxia was corrected with 100% oxygen administered by nasal prongs.

Children with convulsions lasting ≥5 min were treated with a single dose (0.1 mg kg−1) of LZP (Ativan™; 4 mg LZP BP ml−1; Wyeth Laboratories, Maidenhead, UK) administered either intravenously as a slow bolus over 1–2 min (to avoid inducing respiratory depression) or as a deep i.m. injection into the anterior aspect of the thigh. If the convulsion did not stop within 10–15 min after LZP administration, i.v. DZ (0.3 mg kg−1) was administered as a slow bolus over 1–2 min. Convulsions that were refractory to treatment with both LZP and DZ, or those that recurred within the 72-h study period following administration of LZP, were treated with a single dose (15 mg kg−1) of i.m. phenobarbital (100 mg ml−1; Lab Renaudin, St Claud, France). The child was closely monitored for any signs of adverse effects, such as respiratory depression.

Other second- or third-line anticonvulsants, including paraldehyde, phenytoin and sodium valproate, were not available as part of the hospital's routine seizure treatment protocol. Ideally, phenytoin should only be given intravenously together with cardiac monitoring (which is lacking in most health facilities where SM malaria is treated in sub-Saharan Africa, including the present study site).

Blood sampling

Venous blood samples (0.75 ml) for the determination of plasma unconjugated LZP concentrations were collected predose and at 10, 20, 30, 40, 60 min and 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60 and 72 h after LZP administration. The cannula was flushed with sterile heparinized normal saline solution (1.0 ml; 20 IU ml−1). The blood was mixed in lithium-heparinized tubes and centrifuged immediately (1500 g; 5 min) at room temperature. The plasma was separated into polypropylene tubes and stored at −20°C until analysis for unconjugated LZP and paracetamol.

Clinical measurements

All children had respiratory and pulse rates, blood pressure and level of consciousness (Blantyre coma score) [36, 37] recorded at every blood sampling point. In addition, the presence, duration and pattern of convulsions were recorded. Respiratory depression was defined as requiring oxygen by bag and mask, or a poor respiratory effort and reduced respiratory rate following cessation of convulsions (this definition was primarily subjective and did not include routine blood-gas analysis, because facilities for this service were unavailable). Efficacy was assessed using the following measures: (i) the number of children whose convulsions were controlled by a single dose of LZP; (ii) latency (time from initial LZP injection to termination of the seizure); (iii) the use of additional anticonvulsants to control the initial convulsion; (iv) the number of seizures recurring within 72 h after LZP administration; and (v) the duration of seizure control. In a few cases, patients received a second or third anticonvulsant (DZ and/or phenobarbital) after the single dose of LZP. Therefore, the outcome of seizure control was reported descriptively, such as ‘complete control’ or ‘no recurrence’. A successful treatment was defined as one in which the seizure clinically ceased within 15 min after drug administration requiring no further treatment.

Determination of lorazepam and paracetamol concentrations in plasma

The plasma concentrations of unconjugated LZP were measured using sensitive and selective reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection [38]. In brief, LZP and the internal standard (oxazepam) were extracted from alkalinized plasma (pH 9.5) into an organic solvent (n-hexane–dichloromethane; 70 : 30%, v/v). After evaporation of the solvent under white spot nitrogen gas, the residue was reconstituted in mobile phase (100 µl) and a 50-µl aliquot was injected. Chromatographic separation was performed on a C18 reversed-phase analytical column (Synergi™ Max RP; 150 × 4.6 mm i.d.; 4 µm particle size; Phenomenex®, Macclesfield, UK) using an aqueous mobile phase [10 mm KH2PO4 buffer (pH 2.4)–acetonitrile; 65 : 35%, v/v] delivered at a flow rate of 2.5 ml min−1. The limit of quantification of LZP was 10 ng ml−1. Calibration curves were linear over the range 10–300 ng (r2 = 0.99). Lorazepam quality control (QC) samples corresponding to low (LQC), medium (MQC) and high (HQC) concentrations on the calibration curve were 20, 150 and 270 ng ml−1, respectively. The intra-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) at 20, 150 and 270 ng ml−1 of LZP were 7.8%, 9.8% (n = 7 in both cases) and 6.6% (n = 8), respectively. The interassay CVs at the above concentrations were 15.9%, 7.7% and 8.4% (n = 7 in all cases), respectively. The method is selective for LZP, with no interference from other commonly coadministered anticonvulsant, antimicrobial, antipyretic or antimalarial drugs.

Both LZP and paracetamol are eliminated via conjugation with glucuronic acid. Some patients administered LZP were also given paracetamol as an antipyretic. Plasma paracetamol concentrations were measured using an Abbott TDx FLx® fluorescence polarization immunoassay analyser (Abbott Laboratories, Diagnostics Division, Abbott Park, IL, USA). The target (range) concentrations for low (L), medium (M) and high (H) QC samples were 15.0 (12.70–17.30), 35.0 (31.5–38.5) and 150.0 µg ml−1 (135.0–165.0), respectively. The nominal concentrations for the paracetamol calibrators were 0, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 µg ml−1. The manufacturer supplied the samples for calibration and QC samples. The method is reported to have a sensitivity of 1.0 µg ml−1.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Following i.v. administration, the LZP plasma concentration–time data were fitted to a two-compartmental model with elimination from the central compartment, according to the following equation:

where Cp is the plasma LZP concentration at time (t) and the subscripts 1 and 2 refer to the first and second exponential terms, and C1 and C2 refer to the corresponding zero-time intercepts or coefficients [39]. In the present case, λ2 = λz = terminal elimination rate constant.

The plasma LZP concentration–time data were fitted to the above model using the pharmacokinetic data-fitting program TopFit [40]. Reciprocal weighting was used for the concentration data. The area under the plasma LZP concentration–time curve from time zero to infinity (AUC0–∞) was estimated using the linear trapezoidal method [41]. The model of best fit was selected on the basis of Akaike information criterion [42]. Estimates of the elimination half-life (t1/2,λz), apparent volume of distribution of the central compartment (Vc), steady-state volume of distribution (Vss) and clearance (CL) for i.v. administration were obtained using standard pharmacokinetic equations.

A one-compartment model with an absorption phase and an elimination phase was used to fit the concentration–time data following i.m. administration of LZP according to the following equation:

|

where F = fraction of administered dose which is bioavailable, D = dose administered, V = apparent volume of distribution, ka = first order absorption rate constant, K = first order elimination rate constant, and tlag = lag time before commencement of absorption.

The concentration–time data were fitted into the model using TopFit [40]. Values for the maximum plasma LZP concentration (Cmax) and the corresponding time to Cmax (tmax) were determined directly by visual inspection of the concentration vs. time data for each participant. The relative bioavailability of LZP following i.m. administration (Fi.m.) was calculated using the formula:

Statistical analysis

All pharmacokinetic parameters were summarized using descriptive statistics. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the differences between the means of the pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using the commercially available computer program Confidence Interval Analysis [43]. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare demographic and pharmacokinetic parameters between the i.v. and i.m. treatment groups, using the Stata™ (version 8.2) statistical/data analysis program (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

Twenty-six children, median age 30 months (range 6–76) were recruited into the study: 15 (M/F, 6/9) in the i.v. and 11 (M/F, 5/6) in the i.m. LZP group. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the patients in each group. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and biochemical parameters of children administered a single dose (0.1 mg kg−1) of lorazepam either intravenously (i.v.) or intramuscularly (i.m.)

| I.v. lorazepam | I.m. lorazepam | 95% CI for the difference between the means or median | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of children | 15 | 11 | |||

| Demography | |||||

| Sex (M/F) | 15 | 6 : 9 | 11 | 6 : 5 | – |

| Age (months) | 15 | 32.0 (8–91) | 11 | 28.0 (6–78) | −16.0, 16.0 |

| Weight (kg) | 15 | 10.8 (9.2, 12.4) | 11 | 11.1 (8.5, 13.7) | −3.07, 2.44 |

| Axillary temperature (°C) | 12 | 37.6 (37.1, 38.1) | 9 | 37.9 (37.1, 38.8) | −1.25, 0.54 |

| Laboratory parameters | |||||

| Haemoglobin (g dl−1) | 14 | 6.9 (5.2, 8.6) | 7 | 8.4 (6.5, 10.5) | −4.21, 1.03 |

| RBC (×106) µl−1 | 11 | 3.14 (2.34, 3.93) | 6 | 3.87 (3.12, 4.63) | −1.87, 0.40 |

| WBC (×106) l−1 | 11 | 10.3 (6.9, 13.6) | 6 | 9.7 (4.5, 14.8) | −4.77, 5.99 |

Values are expressed as mean [95% confidence interval (CI)], except age, which is expressed as median (range). RBC, Red blood cells; WBC, white blood cells.

Seizure control

Administration of a single dose of LZP (i.v. or i.m.) resulted in complete cessation of seizures in all the children in both groups (Table 2). The median time to seizure cessation was 8 min (range 3–16 min) and 9 min (range 6–27 min) following i.v. and i.m. administration, respectively. Seizures recurred in four of 15 (27%) children following i.v. administration, while none of the children in the i.m. group experienced recurrence of seizures. The median time for recurrence of seizures was 67.5 min (range 40–120). Of the four children whose convulsions recurred after a single i.v. dose of LZP, two were administered i.v. DZ but seizures were not controlled. Thus, in all the four children, convulsions were terminated with a single dose of i.m. phenobarbital (15 mg kg−1). One child whose seizures had been effectively terminated with i.v. LZP absconded after 12 h; the patient was excluded in the assessment of prophylaxis against seizure over the 72-h study period. A 72-h seizure-free interval was observed in 11 of 15 (73%) and 10 of 11 (91%) children after i.v. and i.m. administration of LZP, respectively.

Table 2.

Clinical progress and outcome

| I.v. lorazepam | I.m. lorazepam | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of children | 15 | 11 |

| Blantyre coma score at time 0 | 0 (0–1)* | 0 (0–1)* |

| Blood transfusion | 4 (27%) | 1 (9%) |

| Clinical outcome | ||

| Patients with convulsions controlled with single dose of LZP within: | ||

| 15 min | 14 (93%) | 7 (64%) |

| 27 min | 15 (100%) | 11 (100%) |

| Latency (time from initial LZP injection to seizure control), min | 8 (3–16)* | 9 (6–27)* |

| Patients with recurrence of convulsions | 4 (27%) | 0 (0%) |

| Time to seizure recurrence, min; n = 4 | 67.5 (40–120) | – |

| Patients requiring additional anticonvulsants | ||

| Diazepam | 2 (13%) | 0 (0%) |

| Phenobarbital | 4 (27%) | 0 (0%) |

| Duration of seizure control of LZP, h | ≥72 h; n = 11 | ≥72 h; n = 10 |

| Patients with respiratory depression | 0 | 0 |

| Deaths | 2 (13%) | 1 (9%) |

Values are presented as number (percentage), mean (95% CI) † or median (range)*.

Pharmacokinetics

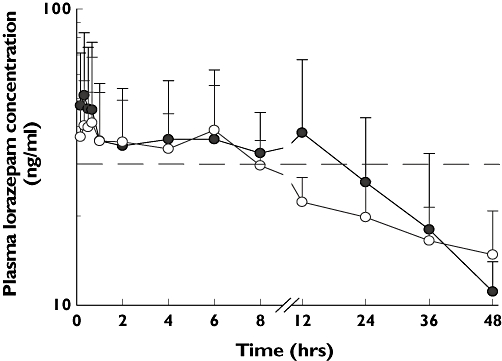

The mean (SD) plasma unconjugated LZP concentration–time curves following i.v. and i.m. administration are shown in Figure 1. Eleven patients (six i.v. and five i.m.) were excluded from the pharmacokinetic analysis for the following reasons: three patients died within 7–14 h, whereas eight patients had fewer blood samples after 24 h to describe fully the elimination phase of LZP (Figure 1 and Table 3). Estimated pharmacokinetic parameters are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Mean (SD) plasma concentration vs. time profile of lorazepam (LZP) following administration of a single dose (0.1 mg kg−1) of LZP either intravenously (i.v.; •, n = 9) or intramuscularly (i.m.; ○, n = 6) to children with severe malaria and convulsions. The dotted line depicts the reported minimal effective concentration (30 ng ml−1) needed for seizure control

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of lorazepam (LZP) following administration of a single dose (0.1 mg kg−1) either intravenously (i.v.) or intramuscularly (i.m.) in children with severe malaria and convulsions

| Parameter | n | I.v. LZP | n | I.m. LZP | 95% CI for the difference between the means or medians |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 11 | 65.1 (47.5, 86) | 10 | 45.3 (29.6, 66.3) | −43.5, 5.0 |

| tmax (h)* | 11 | 0. 5 (0.167–0.67) | 10 | 0.42 (0.167–1.0) | −0.33, 0.17 |

| t1/2 (elimination), h | 9 | 23.7 (9.8, 37.6) | 5 | 36.9 (−1.5, 75.5) | −41.3, 14.9 |

| AUC0–∞ (ng ml−1 h−1) | 9 | 2062.5 (600.6, 3771.4) | 5 | 1843.6 (296.7, 3390.5) | −1267.8, 1883.0 |

| ka (h−1)* | – | 6 | 9.8 (0.033, 22.8) | – | |

| t1/2 (absorption), h* | – | 6 | 0.035 (0.01, 0.071) | – | |

| CL (l h−1) | 9 | 0.64 (0.36, 0.92) | – | – | |

| VC (l kg−1) | 9 | 1.67 (1.25, 2.10) | – | – | |

| Vss (l kg−1) | 9 | 2.59 (1.56, 3.62) | – | – | |

| Bioavailability (F) | 9 | Assume 100% | 6 | 89.4% | – |

Values are presented as mean (95% CI) or median (range) *.

Plasma concentrations of paracetamol were determined in 15 of 26 children (58%) (eight and seven children in the i.v. and i.m. groups, respectively; there was insufficient plasma volume in the remaining 11 children). Seven children (three in the i.v. and four in the i.m. group) had detectable plasma paracetamol concentrations at various times over the 72-h study period (range 1–18.6 µg ml−1 and 1–33 µg ml−1, respectively). The pharmacokinetics of LZP are not affected, i.e. the values for AUC0–∞ and t1/2 for children who had detectable paracetamol concentrations were within the 95% CI for the mean for the group.

Safety

No significant adverse events occurred in any child during the study period. No local adverse reactions were detected in the i.m. injection site and no clinically significant changes in vital signs were observed during the entire study course. Two deaths occurred in the i.v. group, whereas one death occurred in the i.m. group. These children had cerebral malaria and convulsions, and remained in deep coma, and died after 7, 8 and 14 h after drug administration. Cardiorespiratory arrest not considered to be related to LZP was identified as the immediate cause of death in all these cases.

Discussion

This study has shown that LZP when administered intravenously or intramuscularly is a potent, effective and safe agent in terminating acute seizures in children with SM. No published study has evaluated the relationship between plasma LZP concentrations and clinical efficacy in children with SM and convulsions. Given its favourable pharmacokinetics and potential practical advantages, we assessed the pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy and safety of i.v. and i.m. LZP in the treatment of acute seizures in children with SM.

A single dose of LZP controlled the seizures in all the children studied. Of more significant clinical relevance besides its effectiveness is the fact that at the dose (0.1 mg kg−1), it appears to be safe and no significant cardiorespiratory depressant effects were noted in any of the patients. The duration of prophylaxis of seizures following LZP was at least 72 h in about 81% (21/26) of the children treated, which is in agreement with previous reports [17]. This prolonged duration of action of LZP may prevent frequent or continuous drug administration.

The clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of LZP in African children with SM and convulsions are unknown. Plasma LZP concentrations were maintained above the reported minimal effective concentrations for seizure control (30 ng ml−1) for at least 8 h following both i.v. and i.m. administration. These observations are in accord with previous studies [12, 44, 45]. In clinical practice, this implies that in most patients administered LZP, it would not be necessary to give repeated injections or continuous infusions to maintain prolonged seizure control. LZP may be preferable to DZ or MDZ because it produces more sustained seizure control and has a lower incidence of respiratory depression. The mean clearance, volume of distribution and elimination half-life values estimated in the present study after i.v. administration are comparable with values previously reported in children [22, 46, 47]. The pharmacokinetic parameters of LZP are reported to exhibit a considerable degree of interindividual variability, which is expected in critically ill patients with large differences in patient characteristics, pathophysiology and duration of therapy [48].

Regimen

The recommended i.v. dose of LZP for SE is 0.1 mg kg−1 (maximum dose 4 mg) administered at a rate of 2 mg min−1; the dose can be repeated after 10–15 min if seizures do not stop or recur [17, 22–24]. In a retrospective study comparing i.v. LZP with i.v. DZ in the treatment of SE in children (age 2 weeks to 18 years), an initial dose of LZP (0.05 mg kg−1) controlled only 23% of SE, but a mean dose of 0.11 mg kg−1 (range 0.03–0.22) was effective in controlling SE [49]. A dose of 0.05–0.1 mg kg−1 (repeated once) effectively controlled acute epileptic seizures and SE in 76% of children [23]. The dose used in the present study (0.1 mg kg−1) is within the suggested range and is in agreement with the suggestion that an initial dose of LZP of 0.1 mg kg−1 (instead of 0.05 mg kg−1) should be administered to control SE [22].

Efficacy

The overall success rate of 81% (21 of 26) of the children treated with LZP in this study is comparable to previously reported rates (65–100%) [12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 22, 23, 49]. In children and adolescents aged 8.7 years (range 2–18), a median cumulative dose of 2 mg of LZP effectively terminated seizures in 25 of 31 patients (81%) within a median time of 10 min; the seizures stopped within 10 and 20 min in 60% and 84% of the patients, respectively [17]. Moreover, LZP was more effective in terminating generalized convulsive SE; 92% of the patients had their seizures controlled within a median time of 6 min [17].

The median latency period of LZP in the present study (10 min) was longer than that reported in previous studies (<3 min) in children [22, 23] or adults [14] with SE who were successfully treated with LZP. With the use of a median dose of 0.1 mg kg−1 in children <1 year old, and successively lower doses per body weight in older children, other investigators found that LZP stopped seizures in 75% of the patients within 10 min [22]. It is possible that the latency period of LZP in this study was longer than some reported in the literature because of the underlying malaria pathology. Severe malaria in children is a complex syndrome, and the cause of seizures in children with falciparum malaria is not clear, but may be due to fever or some specific effect of Plasmodium falciparum to the brain [50]. This group might be considered to be more difficult to control, but the success of i.v. or i.m. LZP in our study was satisfactory. In five children (one in i.v. group and four in i.m. group), seizures continued beyond 15 min (range 16–27); in such situations, the dose of LZP can be repeated [23, 24].

Safety

In the present study, none of the children had any episode of respiratory depression or arrest. Previous studies have reported respiratory depression rates ranging from 0% to 25% in both children [15, 22, 23, 49] and adults [14] treated with LZP. Children aged <2 years [49] and older patients [14] are significantly more likely to experience respiratory depression or arrest than older children. Transient respiratory arrest has been reported in a single adult patient following administration of a single i.v. dose (4 mg) of LZP [12]. No clinical signs of respiratory depression were noted, but detailed measurements were not performed and only a small number of subjects was studied.

Three deaths occurred among the children who were enrolled in the present study. However, none died immediately after LZP was administered; they died at least 7 h following LZP administration. These children had cerebral malaria and convulsions and remained in deep coma throughout the study period. In addition, one child had hypoglycaemia in addition, while another had anaemia and was given blood transfusion. The LZP Cmax (range 27–59 ng ml−1) and tmax (range 0.167–1.0 h) values in these three subjects were within the 95% CIs for the group. Although cardiorespiratory arrest was identified as the immediate cause of death in all these cases, it is unlikely that LZP could have played a major role, since the results from the present study have shown that LZP is not associated with any significant respiratory depressant effects. It is possible that these children were more severely ill than the survivors.

Potential drug interactions

The major route of LZP elimination is direct conjugation to its glucuronide conjugate, which has little intrinsic pharmacological activity [51]. An important and clinically relevant issue in treatment of children with acute seizures and severe disease is the potential drug interaction with commonly concurrently administered drugs. Of relevance in this study are paracetamol and chloramphenicol, which share the same conjugation pathway with LZP. At therapeutic doses, paracetamol is primarily metabolized via glucuronidation and sulphation by UDP glucuronosyl-transferases and sulpho-transferases, respectively [52]. Few clinically significant drug interactions involving paracetamol have been documented. At present, no published data on the interaction between paracetamol and LZP in humans are available. The results of the present study suggest that there was no interaction between LZP and paracetamol.

Chloramphenicol undergoes a wide variety of metabolic biotransformations in the liver, including conjugation, acetylation, hydrolysis and oxidation. In the present study, plasma concentrations of chloramphenicol were not determined due to the volume-limited samples that could be taken from these patients. Thus, it is difficult to assess whether concurrent administration of chloramphenicol had any clinically significant effects on the pharmacokinetics of LZP in this group.

In the emergency setting, it is often important to administer LZP via the i.v. route for rapid onset of action and assured dose bioavailability. The need to treat acute convulsions promptly when i.v. access is unavailable requires consideration of administration of anticonvulsants by alternative routes. Pharmacokinetic data and a long duration of action (2–72 h) of LZP indicate that it is a suitable alternative [12]. The results from the present study show that i.m. LZP is at least as effective as i.v. LZP and may therefore be useful for acute treatment and prevention of recurrence of convulsions in children in less well equipped and staffed areas, especially in most rural parts in Africa. LZP has been administered rectally in humans when i.v. access was limited or difficult [23], but it has a slow absorption rate in humans [53]. Midazolam (MDZ) has also been used for the emergency treatment of acute seizures in children. Buccal MDZ is at least as effective as rectal DZ in terminating seizures, and it might also be easier to use and more socially acceptable to the caregivers than the rectal route [54, 55].

Limitations of the study

There were some methodological difficulties and, consequently, potential weaknesses and inherent limitations associated with this study. First, the study was open and nonrandomized, and patients were allocated sequentially to the treatment groups. The selection of patients could have been subject to bias. It is possible that some patients' seizures stopped spontaneously and not because of treatment with LZP. We attempted to minimize this possibility by requiring ongoing seizures to last for at least 5 min before administering LZP. In clinical practice, most physicians would initiate anticonvulsant therapy after 5–10 min of continuous motor seizures. However, this is a possible confounding factor in any clinical study assessing the efficacy of anticonvulsants. Second, recurrence of convulsions was noted only in the i.v. group. This could have been due to the fact that children in the i.v. group had convulsions that were more prolonged and thus more difficult to treat. Third, this study was conducted in a pragmatic way within a clinical setting in a typical referral hospital in a resource-poor country, with limited healthcare facilities. Thus, it was not possible to collect additional data (e.g. blood gases, oxygen saturation, blood glucose), which would have been useful in the interpretation of the results on outcome. However, this reflects the reality of what could be expected in such settings, where the drug is likely to be used. Diazepam is routinely used in this setting under similar conditions; it can be assumed (although cautiously) that LZP (which is less likely to cause respiratory depression) would not cause major problems. Finally, sample size calculations were not performed, and the number of patients included in each group was small. Thus, it is difficult to assess whether the study was sufficiently powered to detect any true differences in rates of efficacy and respiratory depression between the two routes of administration.

Conclusion

The results of this study have shown that LZP is effective in termination of acute seizures in children with SM. LZP appears to be well absorbed following i.m. administration, which has an elimination profile comparable to i.v. administration. No significant adverse effects were noted with either of the two administration routes. I.m LZP may be particularly useful as a first-line agent in management of acute convulsions in children in whom i.v. access may be difficult. A randomized study comparing the clinical efficacy of LZP with DZ or MDZ in terminating convulsions associated with SM in children is warranted to substantiate these preliminary results.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the clinical, nursing and laboratory personnel and fieldworkers at the paediatric ward of the New Nyanza Provincial General Hospital, Kisumu, for their valuable support. We are equally grateful to all the children and their parents/guardians who participated. We thank Professor Kevin Marsh and Dr Norbert Peshu [both of the KEMRI/Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Centre for Geographic Medicine Research (Coast), Kilifi], for their support. G.O.K. was supported by a Research Capability Strengthening Grant from WHO (TDR/MIM grant no. 980074 and A50071). S.N.M. was a PhD student in clinical pharmacology supported by The Wellcome Trust of Great Britain. C.R.J.C.N. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Clinical Research Fellow (grant no. 070114/Z/02/Z). This paper is published with permission of the Director of the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI).

References

- 1.Crawley J, Smith S, Kirkham F, Muthinji P, Waruiru C, Marsh K. Seizures and status epilepticus in childhood cerebral malaria. Q J Med. 1996;89:591–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.8.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawley J, Waruiru C, Mithwani S, Mwangi I, Watkins W, Ouma D, Winstanley P, Peto T, Marsh K. Effect of phenobarbital on seizure frequency and mortality in childhood cerebral malaria: a randomised, controlled intervention study. Lancet. 2000;355:701–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waruiru CM, Newton CR, Forster D, New L, Winstanley P, Mwangi I, Marsh V, Winstanley M, Snow RW, Marsh K. Epileptic seizures and malaria in Kenyan children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:152–5. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waller D, Krishna S, Crawley J, Miller K, Nosten F, Chapman D, ter Kuile FO, Craddock C, Berry C, Holloway PA, Brewster D, Greenwood BM, White NJ. Clinical features and outcome of severe malaria in Gambian children. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:577–87. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.3.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holding PA, Stevenson J, Peshu N, Marsh K. Cognitive sequelae of severe malaria with impaired consciousness. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:529–34. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(99)90368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton CR, Krishna S. Severe falciparum malaria in children: current understanding of pathophysiology and supportive treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;79:1–53. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowenstein DH, Alldredge BK. Status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:970–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804023381407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shorvon S. Status Epilepticus: Its Clinical Features and Treatment in Childhood and Adults. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogutu BR, Newton CR, Crawley J, Muchohi SN, Otieno GO, Edwards G, Marsh K, Kokwaro GO. Pharmacokinetics and anticonvulsant effects of diazepam in children with severe falciparum malaria and convulsions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:49–57. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norris E, Marzouk O, Nunn A, McIntyre J, Choonara I. Respiratory depression in children receiving diazepam for acute seizures: a prospective study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:340–3. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299000742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dundee JW, Gamble JA, Assaf RA. Plasma-diazepam levels following intramuscular injection by nurses and doctors (Letter) Lancet. 1974;2:1461. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker JE, Homan RW, Vasko MR, Crawford IL, Bell RD, Tasker WG. Lorazepam in status epilepticus. Ann Neurol. 1979;6:207–13. doi: 10.1002/ana.410060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Homan R, Walker J. Clinical studies of lorazepam in status epilepticus. In: Delgado-Escueta A, Wastterlain CG, Treiman D, editors. Advances in Neurology: Status Epilepticus. New York: Raven Press; 1993. pp. 493–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leppik IE, Derivan AT, Homan RW, Walker J, Ramsay RE, Patrick B. Double-blind study of lorazepam and diazepam in status epilepticus. JAMA. 1983;249:1452–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy RJ, Krall RL. Treatment of status epilepticus with lorazepam. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:605–11. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04210080013006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker JE, Homan RW, Crawford IL. Lorazepam: a controlled trial in patients with intractable partial complex seizures. Epilepsia. 1984;25:464–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1984.tb03444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacey DJ, Singer WD, Horwitz SJ, Gilmore H. Lorazepam therapy of status epilepticus in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 1986;108:771–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)81065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deshmukh A, Wittert W, Schnitzler E, Mangurten HH. Lorazepam in the treatment of refractory neonatal seizures. A pilot study. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:1042–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140240088032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad S, Ellis JC, Kamwendo H, Molyneux E. Efficacy and safety of intranasal lorazepam versus intramuscular paraldehyde for protracted convulsions in children: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1591–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qureshi A, Wassmer E, Davies P, Berry K, Whitehouse WP. Comparative audit of intravenous lorazepam and diazepam in the emergency treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children. Seizure. 2002;11:141–4. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2001.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Isaacs SM, Corry MD, Allen F, Ulrich S, Gottwald MD, O'Neil N, Neuhaus JM, Segal MR, Lowenstein DH. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:631–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crawford TO, Mitchell WG, Snodgrass SR. Lorazepam in childhood status epilepticus and serial seizures: effectiveness and tachyphylaxis. Neurology. 1987;37:190–5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Appleton R, Sweeney A, Choonara I, Robson J, Molyneux E. Lorazepam versus diazepam in the acute treatment of epileptic seizures and status epilepticus. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1995;37:682–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1995.tb15014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treiman DM, Meyers PD, Walton NY, Collins JF, Colling C, Rowan AJ, Handforth A, Faught E, Calabrese VP, Uthman BM, Ramsay RE, Mamdani MB. A comparison of four treatments for generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Veterans Affairs Status Epilepticus Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:792–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cronin CM. Neurotoxicity of lorazepam in a premature infant. Pediatrics. 1992;89:1129–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vlachos P, Kentarchou P, Aloupogiannis G. Lorazepam poisoning. Toxicol Lett. 1978;2:109–10. [Google Scholar]

- 27.English M, Sauerwein R, Waruiru C, Mosobo M, Obiero J, Lowe B, Marsh K. Acidosis in severe childhood malaria. Q J Med. 1997;90:263–70. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/90.4.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton CR, Kirkham FJ, Winstanley PA, Pasvol G, Peshu N, Warrell DA, Marsh K. Intracranial pressure in African children with cerebral malaria. Lancet. 1991;337:573–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91638-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization Communicable Diseases Cluster. Severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94(Suppl. 1):S1–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsh K, Forster D, Waruiru C, Mwangi I, Winstanley M, Marsh V, Newton C, Winstanley P, Warn P, Peshu N, Pasvol G, Snow RW. Indicators of life-threatening malaria in African children. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1399–404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winstanley PA, Mberu EK, Watkins WM, Murphy SA, Lowe B, Marsh K. Towards optimal regimens of parenteral quinine for young African children with cerebral malaria: unbound quinine concentrations following a simple loading dose regimen. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:577–80. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.English M, Waruiru C, Marsh K. Transfusion for respiratory distress in life-threatening childhood malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:525–30. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newton CR, Marsh K, Peshu N, Mwangi I. Blood transfusions for severe anaemia in African children. Lancet. 1992;340:917–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kokwaro GO, Muchohi SN, Ogutu BR, Newton CR. Chloramphenicol pharmacokinetics in African children with severe malaria. J Trop Pediatr. 2006;52:239–43. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmi082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berkley J, Mwarumba S, Bramham K, Lowe B, Marsh K. Bacteraemia complicating severe malaria in children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:283–6. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(99)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molyneux ME, Taylor TE, Wirima JJ, Borgstein A. Clinical features and prognostic indicators in paediatric cerebral malaria: a study of 131 comatose Malawian children. Q J Med. 1989;71:441–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newton CR, Chokwe T, Schellenberg JA, Winstanley PA, Forster D, Peshu N, Kirkham FJ, Marsh K. Coma scales for children with severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:161–5. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muchohi SN, Obiero K, Kokwaro GO, Ogutu BR, Githiga IM, Edwards G, Newton CR. Determination of lorazepam in plasma from children by high-performance liquid chromatography with UV detection. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;824:333–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowland M, Tozer T. Clinical Pharmacokinetics: Concepts and Applications. 2. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1989. pp. 347–75. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heinzel G, Woloszczak R, Thomann P. TopFit Version 2.0: Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Data Analysis System for the PC. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer, Schering AG; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibaldi M, Perrier DG. Pharmacokinetics. 2. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamaoka K, Nakagawa T, Uno T. Application of Akaike's information criterion (AIC) in the evaluation of linear pharmacokinetic equations. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1978;6:165–75. doi: 10.1007/BF01117450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Altman DG, Machin D, Bryant TN, Gardner MJ. Statistics with Confidence. 2. London: BMJ Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenblatt DJ, Comer WH, Elliott HW, Shader RI, Knowles JA, Ruelius HW. Clinical pharmacokinetics of lorazepam. III. Intravenous injection. Preliminary results. J Clin Pharmacol. 1977;17:490–4. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1977.tb05641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenblatt DJ, Joyce TH, Comer WH, Knowles JA, Shader RI, Kyriakopoulos AA, MacLaughlin DS, Ruelius HW. Clinical pharmacokinetics of lorazepam. II. Intramuscular injection. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1977;21:222–30. doi: 10.1002/cpt1977212222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDermott CA, Kowalczyk AL, Schnitzler ER, Mangurten HH, Rodvold KA, Metrick S. Pharmacokinetics of lorazepam in critically ill neonates with seizures. J Pediatr. 1992;120:479–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80925-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Relling MV, Mulhern RK, Dodge RK, Johnson D, Pieper JA, Rivera GK, Evans WE. Lorazepam pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics in children. J Pediatr. 1989;114:641–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80713-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swart EL, Zuideveld KP, de Jongh J, Danhof M, Thijs LG, Strack van Schijndel RM. Comparative population pharmacokinetics of lorazepam and midazolam during long-term continuous infusion in critically ill patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:135–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giang DW, McBride MC. Lorazepam versus diazepam for the treatment of status epilepticus. Pediatr Neurol. 1988;4:358–61. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(88)90083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Idro R, Jenkins NE, Newton CR. Pathogenesis, clinical features, and neurological outcome of cerebral malaria. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:827–40. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verbeeck RK, Branch RA, Wilkinson GR. Drug metabolites in renal failure: pharmacokinetic and clinical implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1981;6:329–45. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198106050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cummings AJ, King ML, Martin BK. A kinetic study of drug elimination: the excretion of paracetamol and its metabolites in man. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1967;29:150–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1967.tb01948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Graves NM, Kriel RL, Jones-Saete C. Bioavailability of rectally administered lorazepam. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1987;10:555–9. doi: 10.1097/00002826-198712000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott RC, Besag FM, Neville BG. Buccal midazolam and rectal diazepam for treatment of prolonged seizures in childhood and adolescence: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:623–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06425-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McIntyre J, Robertson S, Norris E, Appleton R, Whitehouse WP, Phillips B, Martland T, Berry K, Collier J, Smith S, Choonara I. Safety and efficacy of buccal midazolam versus rectal diazepam for emergency treatment of seizures in children: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:205–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]