From 2001 to 2003, the global number of children orphaned by AIDS increased from 11.5 million to 15 million (estimate range 13–18 million), and 12 million of these AIDS orphans were living in sub-Saharan Africa (UNICEF, 2004). It was estimated that, based on current trends, the number of AIDS orphans could reach 25 million by 2010 and 40 million by 2020 (Phiri & Webb, 2005; UNICEF, 2004). The age distribution of orphans was fairly consistent across countries, with approximately 12% of orphans being 0–5 years old, 33% being 6–11 years old, and 55% being 12–17 years old (UNICEF).

The death of a parent during childhood has a profound and lifelong impact on a child’s psychosocial well-being. Cross-cultural research on natural grieving processes suggests that most humans need to recognize their grief and be able to express it directly in order to resolve their loss (Fraley & Shaver, 1999; Parkes, Laungani, & Young, 1998). Children in particular are at increased risk for unresolved or complicated bereavement due to their developmental vulnerability (e.g., intellectual immaturity and emotional dependency). Children orphaned by AIDS may face additional psychological and social challenges, including stigmatization, the impending or actual death of the surviving parent, disruptions in subsequent care, and financial hardship; these challenges may further impede the grieving process, placing these children at heightened risk of prolonged mental and behavioral problems (Cluver & Gardner, 2006; Sachs & Sachs, 2004). However, limited attention has been paid to psychosocial and developmental needs of children orphaned by HIV/AIDS, particularly in resource-poor countries or regions (Atwine, Cantor-Graae, & Bajunirwe, 2005; Cluver & Gardner, 2007).

A developmental psychopathology approach strives to understand the complexity of human development as the dynamic transaction between the person and the environment. Cummings, Davies, and Campbell (2000) describe the principles of a developmental psychopathology framework. First, because development is multi-determined, its understanding must be interdisciplinary and cross domains from biology and genetics to social ecology and culture. Second, developmental psychopathology is interested in the range of outcomes from normal development to psychopathology and the range in between. The recognition that multiple outcomes are possible even in response to the horrific environmental stressors is paramount. Third, this approach seeks to understand the risk and protective factors that may account for this range of outcomes. Consistent with social ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), these factors may occur across multiple systems (e.g., individual, family, extra-familial). Fourth, a developmental psychopathology approach does not view adaptive and maladaptive behavior as static. Both the individual and the environment change over time; thus the transaction and associated outcomes are dynamic as well.

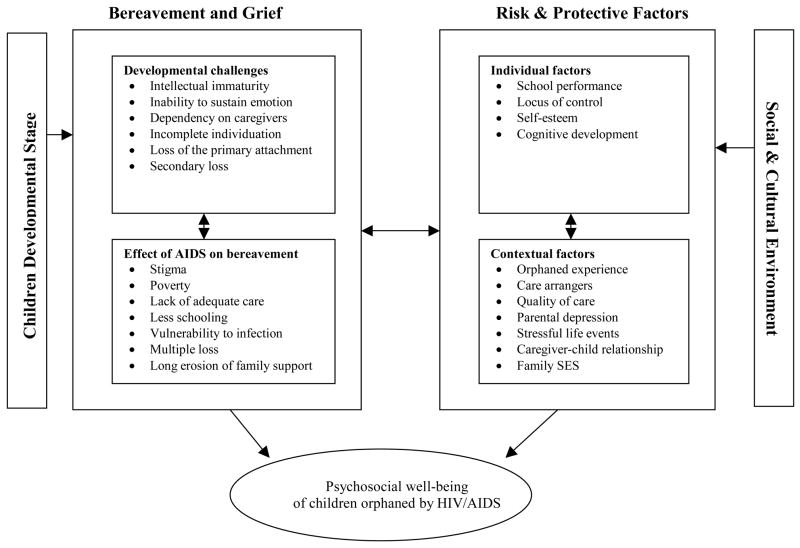

An illustration of a dynamic, multi-determinants developmental psychopathology framework of the psychosocial needs of children orphaned by HIV/AIDS is provided in Figure 1. A developmental psychopathology approach has shown significant ability to guide research, intervention, and policy around the psychosocial needs of children exposed to significant stressors, for example, in the areas of child maltreatment and orphans in institutionalized settings in Eastern Europe (O’Conner, 2003a; Rutter, 1998).

Figure 1.

Developmental psychopathology framework of psychosocial needs of children orphaned by HIV/AIDS

The purpose of the current article is to describe a developmental psychopathology model (see Figure 1) of the psychosocial needs of AIDS orphans, identify gaps in the literature, and provide suggestions for future research on AIDS orphans, particularly, those living in resource-poor countries and regions.

General Concepts of Bereavement and Grief

When the death of a beloved takes place (even when the death is expected), individuals may experience a wide range of emotions, commonly referred to as “bereavement and grief.” Psychologists and grief theorists describe bereavement as the state of having suffered a loss, grief as the normal reaction one experiences in that state, and mourning as both an intra-psychic process and cultural response to grief (Rando, 1984; Sanders, 1986). Bereavement is a distressing but natural and probably universal experience. Grief is understood as an incorporation of diverse psychological (affective, cognitive, social, behavioral) and physical (physiological, somatic) manifestations, the overt expression of which varies both between and within cultures. Affective manifestations include depression and despair, dejection, anxiety, guilt, anger, hostility, and loneliness. Cognitive manifestations include preoccupation with the deceased, low self-esteem, self-reproach, helplessness, hopelessness, a sense of unreality, and problems with memory and concentration. Behavioral and social manifestations include agitation, crying, fatigue, and social withdrawal (Stroebe, Stroebe, & Schut, 2000). Although research in general has concentrated on these negative components, there has been a trend to explore the positive aspects associated with grief, including personal growth and creativity (Stroebe et al.).

Much like the process of physical healing, the grieving process is a series of tasks that one must work through before fully adjusting to the loss (Parkes et al., 1998; Worden, 1996). Based on the attachment theory, Bowlby (1982) postulated that there were four phases in a grieving process: (a) shock, associated with symptoms of numbness and denial; (b) yearning and protest, as realization of the loss develops, (c) despair, accompanied by many of the manifestations described above over a longer period, and (d) recovery, marked by a general feeling of increasing well-being, acceptance of and adaptation to the loss. Research suggests that if these steps are not successfully completed, individuals will suffer “complicated” grief, which can be defined as the deviation from the cultural norm in the time course or intensity of specific or general symptoms of grief.

Developmental Challenges Faced by Bereaved Children

Numerous studies documenting general symptomatology of bereavement during childhood have suggested that children’s symptoms are similar to those experienced by adult mourners (Rando, 1984). However, children are generally disadvantaged in this process because of developmental vulnerabilities. A number of difficulties and risks may prevent children from going through the natural grieving process that is necessary to recover from the loss (Rando; Worden, 1996; Worden & Silverman, 1996). These risk and protective factors include: (a) Intellectual immaturity. Children have immature concepts related to death that can foster fear and fantasy. Incomplete understanding of death can be compounded by inaccurate information from adults; (b) Inability to sustain emotion. Children are limited in the capacity to tolerate pain intensely over time. Children’s sadness often occurs in bursts or while playing, which is easily misunderstood or missed entirely; (c) Dependency on caregivers. Children have little control over their lives and are dependent on the adults who care for them regardless of the adult’s skill and availability. Fulfillment of children’s needs is often reduced to the caregiver’s ability or willingness to give; (d) Incomplete individuation. Psychological autonomy occurs throughout childhood, and young children, in particular, are less able to separate personal identity and fate from those closest to them; (e) Loss of the primary attachment. When a child’s parent dies, the child loses his/her primary attachment in life; and (f) Secondary loss. The loss of a parent is often accompanied by additional stressors that may inhibit children’s abilities to mourn and also directly affect children’s mental health. These stressors include income loss, the stigma associated with the cause of death, and social changes in life, such as changes in home, community, education, and separation from siblings (Thompson, Kaslow, Price, Williams, & Kingree, 1998). All these changes following the death of a parent and children’s resources for adapting to change can affect the psychological well-being of a bereaved child over time (Felner, Terre, & Rowlinson, 1988).

Outcomes of Bereaved Children

Several studies in the United States have examined the link between childhood bereavement and mental health problems in later life (Dowdney, 2000; Lutzke, Ayers, Sandler, & Barr, 1997). The Harvard Child Bereavement (HCB) Study, for example, was a prospective study of children ages 6–17 years who had lost a parent to death. The HCB study involved a representative community sample, with a demographically-matched sample of non-bereaved children, and a longitudinal assessment of 2 years after a parent’s death. Compared to non-bereaved children, bereaved children scored significantly higher on anxiety/depression and withdrawal and lower on self-esteem at the 2-year follow-up assessment. However, 2 years after their parents’ deaths, bereaved children did not differ significantly from non-bereaved children with regard to somatic symptoms and externalizing symptomatology (Worden, 1996).

Systematic reviews of the published literature (Lutzke et al., 1997; Williams, Chaloner, Bean, & Tyler, 1998) concluded that while grief is a normal reaction to parental death, many orphaned children suffer from complicated forms of grief. A developmental psychopathology approach provides a framework for understanding the varying developmental trajectories of bereaved children (Cicchetti & Cohen, 1995; Pennington, 2002). The developmental psychopathology perspective emphasizes the need to examine (1) how adversity (e.g., loss of a parent) can challenge the successful negotiation of normal stage salient issues (e.g., formation of a secure attachment relationship and satisfying peer relations) that children face during childhood (Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005); (2) how major and minor stressors are often cumulative and contribute to cognitive and mental health problems in a dose-response manner (Baldwin et al., 1993; McCabe, Clark, & Barnett, 1999); (3) how protective factors within the child and social environment contribute to resilient outcomes in the majority of children facing adversity (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000); and (4) how the developmental timing of trauma and loss as well as the post-loss environment both contribute to outcomes (O’Connor, 2003a). However, most of the studies on developmental challenges and psychosocial outcomes of bereaved children were conducted in the United States, and there is a literature gap with regard to the issues in developing countries or resource-poor regions.

Risk and Protective Factors that May Contribute to Outcomes of Bereaved Children

Research on risk and resilience in the face of childhood adversity has emphasized that most children do not develop significant mental health problems as a reaction to a single stressor. Rather, the relative balance of risk and protective factors within children’s lives determines psychosocial health (Felner et al., 1988; Lin, Sandler, Ayers, Wolchik, & Luechen, 2004). The child bereavement literature has identified a number of individual and contextual factors predicting children’s long-term response to grief-related stressors (Lutzke et al., 1997).

Individual Factors

Individual factors include school performance, locus of control beliefs, self-esteem, and cognitive development. Previous studies have found that bereaved children had significantly poorer school performances than their non-bereaved peers (Lowton, Higginson, & Shipman, 2001; Van Eerdewegh, Bieri, Parrilla, & Clayton, 1982). Longitudinal studies in the United States (Silverman & Worden, 1992) also found a significant mediating effect of locus control and self-esteem on the relation between bereavement and psychological symptomatology among children, with an external locus of control and low self-esteem leading to higher symptomatology. The impact of bereavement on cognitive development and its relation to mental health status in later life have not been assessed among AIDS orphans, although previous studies of Romanian orphans found that IQ was associated with early social and emotional deprivation (O’Conner & Rutter, 2000), and IQ served as a protective factor between childhood risk and adolescent and adult antisocial behavior (Kim-Cohen, Moffitt, Caspi, & Taylor, 2004).

Contextual Factors

Previous studies have suggested a number of contextual factors that may potentially affect the mental health of children orphaned by AIDS (Cluver & Gardner, 2007; Foster, 2002; Makame, Ani, & Grantham-McGregor, 2002). These factors include varied orphanhood experiences (e.g., double orphans, paternal orphans, and maternal orphans), different care-arrangements (home care, kinship care, or institutional care), and quality of care (e.g., caregiver-child relationship). Other contextual factors include parental depression, stressful life events, parent-child relationship, family environment, and family socioeconomic status.

Most of the contextual factors concern the extent to which caregivers are available (both physically and emotionally) to protect, nurture, and care for the child during bereavement (e.g., attachment security) (Bowlby, 1982). Without empathic caregivers (attachment figures) to help children recognize and express grief, normal reactions to loss can go unrecognized and persist into emotional and behavioral problems. Children, therefore, are at risk of growing up with unrecognized and unaddressed grief and prolonged negative emotions that are often expressed with anger and depression. Failure by caregivers to recognize and address poor social adjustment and associated mental symptoms will aggravate the child’s psychological problems. In particular, impersonal and distant involvement of adults does not support the intimate attachment relationship thought necessary for healthy human development (Bowlby; Larose, Berneir, & Tarabulsy, 2005; Marsh, McFarland, Allen, McElhaney, & Land, 2003; Schneider, Atkinson, & Tardif, 2001).

Research based on attachment theory has underscored the importance of taking into consideration the quality of the child’s attachment relationships before and after the loss (Bowlby, 1982; Fraley & Shaver, 1999). Previous research has consistently shown that children and adolescents with secure attachments have an advantage on measures of language, academic, and social and emotional functioning (Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, Juffer, 2003; Waters, Weinfield, & Hamilton, 2000). Research around the world during the past 50 years has provided strong support for the idea that caregiver sensitivity and emotional availability are key in determining children’s attachment security (Chisholm, 1998; O’Connor, 2003b). Moreover, children’s attachment security changes in relation to changes in the caregiving environment (Provence & Lipton, 1962). Therefore, the quality of children’s attachment relationships before and after the loss of their parent(s) might likely be important in predicting concurrent and future social and emotional health.

Compounding the grief reaction among children who lose a parent are the effects of care arrangement (Lee & Fleming, 2003). There is limited understanding of the effect of the quality of care subsequent to loss on the outcomes of bereaved children. Prior research with children placed outside of their homes has devoted little or no attention to assessing the quality of out-of-home care. Childrearing environments found in orphanages, often referred to as institutionalized care, are universally assumed to be highly undesirable, if not pathogenic (Larose et al., 2005; Marsh et al., 2003; Schneider et al., 2001). Such experiences are referred to as conditions of “social deprivation” (O’Conner & Rutter, 2000; Rutter, 1998).

Studies of orphanage-reared Romanian children adopted into families in the United States during the early 1990s suggested severe developmental consequences of institutional care that affords neither stimulation nor consistent attachment relationships with caregivers and in which children are often confronted with physical adversities, including malnutrition, exposure to pathogens, and untreated chronic illness (Stroebe et al., 2000). There is little data available regarding the institutional care of AIDS orphans (Zhao et al., in press). Based on field experiences, representatives of 30 non-governmental organizations (NGOs) from eight eastern and southern African nations attending a workshop in Lusaka, Zambia, in February 1994 recommended that orphanages should be used only in emergency situations and on a temporary basis (Chevallier, 1994).

Objective observations have been used in previous studies to describe residences (orphanages or homes) for children in regard to the amount of stimulation, nurturance, and involvement afforded to the children. Moreover, research on children exposed to economic poverty has found that the linguistic, cognitive, social, and emotional stimulation in children’s living environments can be observed during a brief visit to the children’s living environment, and that such stimulation mediates the relation between economic impoverishment and growth in child intellectual, linguistic, academic, social, and emotional outcomes (Bradley, Corvyn, Burchinal, McAdoo, & Coll, 2001; Kim-Cohen et al., 2004).

Effect of AIDS on Bereaved Children in Developing Countries: Additional Risk Factors

Although the research regarding bereaved children has provided a general, formative conceptual framework for research on AIDS orphans, generalizing the conclusions reached by studies of children orphaned by other causes to children orphaned by AIDS must be done with caution because there are a number of unique characteristics associated with AIDS-caused death (e.g., preventable nature of the disease, higher level of stigmatization, recurrent losses in family). Although few published studies have examined the psychological well-being of children orphaned by AIDS in resource-poor countries, data from Africa suggest that AIDS orphans reported a higher level of depression than children orphaned by other causes or children in intact families (Atwine et al., 2005; Foster, 1997; Sengendo & Nambi, 1997). In addition to the obstacles faced by children orphaned by other causes, characteristics unique to AIDS may create additional cognitive and social barriers for grief resolution among AIDS orphans and place these children at an especially heightened risk for behavioral and emotional problems (Cluver & Gardner, 2007; Sachs & Sachs, 2004; Zhao et al., in press).

Additional Barriers

Stigma

An important distinction between AIDS orphans and other orphans is that AIDS orphans have lost parents to a preventable, but highly stigmatized, disease, which can cause additional distress and anger in these children. AIDS orphans may be affected by stigma in several ways. First, stigma may cause anxiety and fear related to the disclosure of their parents’ illnesses and consequently reduce children’s abilities to express grief (Siegel & Gorey, 1994; Wood, Chase, & Aggleton, 2006). Second, AIDS orphans are often the victims of discrimination (e.g., denied schooling), which results in a greater secondary loss for AIDS orphans than for other orphans. Third, stigma often precludes adequate family and community support (Notzi, 1997), including providing foster care for AIDS orphans (Hamra, Ross, Karuri, Orrs, & D’Agostina, 2005; Seeley et al., 1993). Orphanages and schools often are reluctant to admit children from families infected with AIDS. Some infected parents and orphans have withdrawn from contact with others, making it more difficult for AIDS orphans to obtain the help they need (Zhao et al., in press).

Poverty

A child’s basic needs (e.g., food, clothing, shelter, health) have to be met in order for the child’s psychosocial needs to be addressed. Globally, children whose parents die of AIDS are often doubly burdened, losing not only the attention, care, and love that a parent gives, but also losing access to basic resources, such as housing and land. Households impoverished through the long illness of a parent and the cost of medical care leave few assets for surviving children (Yang et al., 2006; Zhao et al., in press). After parents die, some children go to live with relatives, who are themselves often impoverished and without sufficient resources to take on these orphans. Many AIDS orphans suffer from a diminished standard of living due to AIDS morbidity long before their parents die. As a result, orphaned children are especially vulnerable and potentially at increased risk of poor health (Ayieko, 1998). Because of the lack of resources and supports for basic needs, concerns about poverty among AIDS orphans in developing countries often outweigh concerns about psychosocial needs (Foster, 2002). For example, almost all HIV-infected parents in Uganda were concerned about their children’s futures, but mainly in relation to economic factors; only 10% mentioned concern about their children’s emotional well-being (Giborn, Nyonyintono, Kabumbuli, & Jagwe-Wadda, 2001).

Lack of adequate care

In sub-Saharan Africa, 90% of orphaned children are cared for by the extended family (e.g., kinship care) (UNICEF, 2004). Because AIDS often disproportionately affects young and middle-age adults in families, AIDS orphans tend to be younger than other orphans, and the extended family members who take care of these orphans are generally older than those who foster other orphans (Lusk, Mararu, O’Gara, & Dastur, 2003). There has been growing concern that the extended family system is no longer capable of providing adequate care for AIDS orphans in Africa given the increase in the number of disadvantaged children and severe economic constraints (Abebe & Aase, 2007; Freeman & Nkomo, 2006; Madhavan, 2004; Nyambedha, Wabdibba, & Aagaard-Hansen, 2003).

A few published studies suggest that kinship care faces a number of challenges. First, a considerable number of orphaned children were placed in the care of the elderly in the extended family (Foster, 1997; Notzi, 1997). Elderly people face multiple challenges that include limited income, struggling to cope with the loss of loved ones, and poor adjustment to the role change from being provided for to being the provider (Hunter, 1990). Second, the capacity of the extended family to care for orphans may be limited in areas of high HIV/AIDS prevalence and poverty (Howard et al., 2006). The increasing morbidity and mortality rates among adults, migration, and economic devastation could strain the resources of the extended family system, thus leaving orphans vulnerable (Barnett & Blaikie, 1992; Nyambedha et al., 2003; Poonawala & Cantor, 1991). Many foster families in developing countries were experiencing significant financial hardship after they assumed responsibility for AIDS orphans (Miller, Gruskin, Subramanian, Rajaraman, & Heymann, 2006; Safman, 2004).

Some children remain in child-headed households after their parents died. Makame and colleagues (2002) suggested that children living in child-headed households or with grandparents have the most serious psychological problems because of the lack of necessary and adequate social and emotional support in these households.

Less schooling

Schooling is important for normal child development and even more important for bereaved children, as it affords children the opportunity to socialize with their peers and to overcome the negative feelings/emotions of grieving. However, many children orphaned by AIDS may have to drop out of school due to the need to care for a sick parent, to take care of other children in the family, or to go to work to support the family. They may also have been forced out of school due to financial hardship and/or the stigma and fear associated with HIV/AIDS. Studies in developing countries have found that AIDS orphans experience a greater degree of interruption in their education than children orphaned by other causes or children in intact families (Nyamukapa & Gregson, 2005; Yang et al., 2006; Yamano, Shimamura, & Sserunkuuma, 2006).

Vulnerability to HIV/STD infection

In addition to other risks, AIDS orphans’ own HIV infection or vulnerability to HIV/STD infection may serve as additional stressors for psychosocial adjustment. There are limited data from developing countries on the seroprevalence among AIDS orphans and its impact on their bereavement and psychosocial needs (Gregson et al., 2005). Existing literature from South Africa suggested that early onset of and frequent exposure to sexual risk experiences often put AIDS orphans at an increased risk of HIV/STD infection (Gregson et al.; Thurman, Brown, Richter, Maharaj, & Magnani, 2006). These sexual risks were often associated with poorer economic conditions in the households providing care for AIDS orphans and reduced educational and employment opportunities for young men and women orphaned by HIV/AIDS.

Multiple deaths in the family

Another characteristic of AIDS-related deaths is that multiple members of a family may be infected. Children may face uncertainty or actual recurrent losses, including the death of the surviving parent, relatives, guardians, and siblings, leading to a recurrent psychological impact. If children have had a previous painful loss or separation that has not been fully dealt with, this makes them even more vulnerable to the difficulties of a subsequent bereavement (Dyregrov, 1991). Also, multiple deaths in a family (or extended family) make it difficult for children to get the necessary emotional and social support from other (surviving) family members during bereavement.

Long duration of erosion of family support

AIDS-related orphanhood frequently occurs after a period of erosion in the family situation. The death of parents is neither the beginning nor the end of a series of AIDS-induced “family crisis” events experienced by children. The onset of illness of the parents marks the beginning of the deterioration of family units and trauma in the emotional, psychological, and material life of children. As the illness progresses, parents are less able to care for their children and themselves. Families’ socioeconomic status, children’s educational attainment, and other psychosocial statuses may have begun to deteriorate before children become orphans; thus AIDS orphans may have begun to experience the consequences of being orphans even before the death of their parents (Bicego, Rutstein, & Johnson, 2003; Case, Paxson, & Ableidinger, 2004). These findings suggest that high levels of difficulties existed in the families prior to the parents’ deaths.

Summary and Limitations of Existing studies

Although findings in the literature are relatively consistent regarding the relation between bereavement and internalizing problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, withdrawal), the number and scope of studies are limited (Lutzke et al., 1997). Furthermore, data from various studies are inconsistent regarding both the short-term and the long-term impact of bereavement on a number of important children outcome measures (e.g., somatic symptoms, externalizing problems, and developmental outcomes) (Kessler, Davis, & Kendler, 1997; Lutzke et al.). Researchers have attributed the inconsistency to methodological limitations inherent in the studies of bereaved children (Lutzke et al.; Worden, 1996). These limitations include small sample sizes (most with N < 50), potential sampling bias (unrepresentative samples, such as clinically referred samples), lack of demographically matched, non-bereaved control groups or other appropriate comparison groups, use of non-standardized assessment instruments, lack of data collected from the children (e.g., most with only parents’ or teachers’ reports of children’s outcomes), and lack of prospective study design. However, the inconsistency is also likely due to the varied outcomes in response to the loss of a parent. According to a developmental psychopathology approach, this variability is likely the result of risk and protective factors that affect response to stressors. Individual factors, such as locus of control, self-esteem, and IQ, and contextual factors, such as secure attachment, likely play a role in the outcome of bereavement. Furthermore, the type and quality of care environments subsequent to loss of a parent and the relationship to child outcomes has not been adequately studied.

Future Research Needs

Based on the review of both global experience and literature on the care of AIDS orphans, we highlight the following needs in future studies of psychosocial needs of AIDS orphans beyond their basic needs (food, clothing, shelter, and health).

First, future studies need to be guided by a developmental psychopathology framework integrating findings from normal and problematic responses to loss and other stressful life events. With the developmental psychopathology framework, future studies need to bring together an assessment model that integrates research findings from the literature on bereavement, attachment, and risk and resilience to delineate the psychosocial needs of children orphaned by AIDS.

Second, future studies need to assess the quality of children’s attachment relationships to lost parents as well as to post-loss attachment figures.

Third, future studies need to prospectively examine causal relations between bereavement and children’s psychological well-being in longitudinal investigations and identify both individual and social factors that mediate or moderate such relations among children orphaned by AIDS in resource-poor countries where psychosocial needs of these orphaned children have been largely neglected.

Fourth, future studies should include socio-demographically matched non-orphans (or non-AIDS orphans) as comparison children when it is feasible and compare relevant psychosocial attributes in these children with demographically matched comparison children who have no experience of parental loss or HIV/AIDS-related parental loss. The data from such comparisons will help researchers contextualize the grief reactions and mental health statuses of orphans within their communities and cultural contexts.

Fifth, well-designed qualitative or ethnographic studies are needed to explore the reality and the meaning (in a given cultural setting or a given development stage) of the life experience of children orphaned by HIV/AIDS. Qualitative or ethnographic data can be used to inform the development of culturally and developmentally appropriate assessment instruments and interventions. Finally, future studies should be constructed to obtain comprehensive assessments of child outcomes. Collection of emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and schooling outcome measures, using multiple informants (caregivers, children, and teachers) as well as observational data (e.g., living environment), is the first step toward understanding the psychosocial needs of children orphaned by HIV/AIDS. Data should be collected from children who experienced loss of different family members and from children who resided in different orphan care arrangements, so potentially ameliorable or amenable correlates of behavioral and emotional problems can be identified.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is an outcome of the implementation of a study funded by a NIMH grant R01MH076488-01. The authors wish to thank Ms. Joanne Zwemer for assistance in manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abebe T, Aase A. Children, AIDS and the politics of orphan care in Ethiopia: The extended family revisited. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:2058–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwine B, Cantor-Graae E, Bajunirwe F. Psychological distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayieko AK. From single parents to child-headed households: The case of children orphaned in Kisumu and Siaya District (Study Paper No 7) Rome, Italy: Food And Agriculture Organization of the United Nations HIV and Development Programme; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:195–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AL, Baldwin CP, Kasser T, Zax M, Sameroff A, Seifer R. Contextual risk and resiliency during late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:741–761. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett T, Blaikie P. AIDS in Africa: Its present and future impact. London: Belhaven Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bicego G, Rutstein S, Johnson K. Dimensions of the emerging orphan crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment. 2. New York: Basic; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corvyn RF, Burchinal M, McAdoo HP, Coll CP. The home environments of children in the United States Part II: Relations with behavioral development through age thirteen. Child Development. 2001;72:1868–1886. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Paxson C, Ableidinger J. Orphans in Africa: Parental death, poverty, and school enrollment. Demography. 2004;41(3):483–508. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier E. AIDS, children, families: How to respond? Global AIDS News. 1994;4:18–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm K. A three-year follow-up of attachment and indiscriminate friendliness in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Child Development. 1998;69:1092–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ. Perspectives on developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology. 1–2. New York: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L, Gardner F. The psychological well-being of children orphaned by AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2006;5(8) doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-5-8. Retrieved July 20, 2007, from http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1557503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cluver L, Gardner F. Risk and protective factors for psychological well-being of children orphaned by AIDS in Cape Town: A qualitative study of children and caregivers perspectives. AIDS Care. 2007;19(3):318–325. doi: 10.1080/09540120600986578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dowdney L. Childhood bereavement following parental death. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:819–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyregrov A. Grief in children: A handbook for adults. London: Jessica Kingsley; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Felner R, Terre L, Rowlinson R. A life transition framework for understanding marital dissolution and family reorganization. In: Wolchik SA, Karoly P, editors. Children of divorce: Empirical perspectives on adjustment. New York: Garder; 1988. pp. 35–65. [Google Scholar]

- Foster G. Perceptions of children and community members concerning the circumstances of orphans in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 1997;9(4):391–405. doi: 10.1080/713613166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster G. Beyond education and food: Psychosocial well-being of orphans in Africa. Acta Paediatrica. 2002;91:502. doi: 10.1080/080352502753711588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley C, Shaver PR. Loss and bereavement: Attachment theory and recent controversies concerning “grief work” and the nature of detachment. In: Cassidy J, Shaver JR, editors. Handbook of attachment theory and research. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 735–759. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M, Nkomo N. Guardianship of orphans and vulnerable children. A survey of current and perspective South African caregivers. AIDS Care. 2006;18(4):302–310. doi: 10.1080/09540120500359009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giborn LZ, Nyonyintono R, Kabumbuli R, Jagwe-Wadda G. Making a difference for children affected by AIDS: Baseline findings from operations research in Uganda. Washington DC: Population Council; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, Wambe M, Lewis JJC, Mason PR, et al. HIV infection and reproductive health in teenage women orphaned and made vulnerable by AIDS in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):785–794. doi: 10.1080/09540120500258029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamra M, Ross MW, Karuri K, Orrs M, D’Agostino A. The relationship between expressed HIV/AIDS-related stigma and beliefs and knowledge about care and support of people living with AIDS in families caring for HIV-infected children in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):911–922. doi: 10.1080/09540120500100593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard BH, Phillips CV, Matinhure N, Goodman KJ, McCurdy SA, Johnson CA. Barriers and incentives to orphan care in a time of AIDS and economic crisis: A cross-sectional survey of caregivers in rural Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(27) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-27. Retrieved July 20, 2007, from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/6/27/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hunter S. Orphans as a window on the AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa: Initial results and implications of a study in Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 1990;31(6):681–690. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90250-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS. Childhood adversity and adult psychiatry disorder in the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:1101–1119. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A. Genetic and environmental process in young children’s resilience and vulnerability to socioeconomic deprivation. Child Development. 2004;75:651–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larose S, Berneir A, Tarabulsy GM. Attachment state of mind, learning dispositions and academic performance during the college transition. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;41:281–289. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LM, Fleming PL. Estimated number of children left motherless by AIDS in the United States, 1978–1998. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;34(2):231–236. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200310010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KK, Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA, Luechen LJ. Resilience in parentally bereaved children and adolescents seeking preventive services. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(4):673–683. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowton K, Higginson I, Shipman C. Evaluation of an intervention to reduce the impact of childhood bereavement at school. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2001;15(4):397–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusk D, Mararu J, O’Gara C, Dastur S. Speak for the Child. Washington, DC: Academy for Educational Development; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;75:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzke JR, Ayers TS, Sandler IN, Barr A. Risks and interventions for the parental bereaved child. In: Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, editors. Handbook of children’s coping: Linking theory and intervention. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 215–243. [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan S. Fosterage patterns in the age of AIDS: Continuity and change. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:1443–1454. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makame V, Ani C, Grantham-McGregor S. Psychological well-being of orphans in Dar El Salaam, Tanzania. Acta Paediatrica. 2002;91:459–465. doi: 10.1080/080352502317371724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh P, McFarland FC, Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Land D. Attachment, autonomy, and multifinality in adolescent internalizing and risky behavioral symptoms. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:451–467. doi: 10.1017/S0954579403000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KM, Clark R, Barnett D. Family protective factors among urban African American youth. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:137–150. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CM, Gruskin S, Subramanian SV, Rajaraman D, Heymann SJ. Orphan care in Botswana’s working households: growing responsibilities in the absence of adequate support. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(8):1429–1435. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notzi JP. Effect of AIDS on children: The problem of orphans in Uganda. Health Transition Review. 1997;7(1):23–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha EO, Wabdibba S, Aagaard-Hansen J. “Retirement lost” - the new role of the elderly as caretakers for orphans in western Kenya. Journal of Cross Culture Gerontology. 2003;18:33–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1024826528476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamukapa C, Gregson S. Extended family’s and women’s roles in safeguarding orphans’ education in AIDS-afflicted rural Zimbabwe. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:2155–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG. Early experiences and psychological development: Conceptual questions, empirical illustrations, and implications for intervention. Development and Psychopathology. 2003a;15:671–690. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG. Natural experiments to study the effects of early experience: Progress and limitations. Development and Psychopathology. 2003b;15:837–852. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Conner TG, Rutter M. Attachment disorder behavior following early severe deprivation: Extension and longitudinal follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:703–712. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200006000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes CM, Laungani P, Young B, editors. Death and bereavement across cultures. New York: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington BF. The development of psychopathology. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Phiri S, Webb D. Cornia GA, editor. The impact of HIV/AIDS on orphans and programme and policy responses. AIDS, public policy and child well-being. Retrieved July 27, 2007, from http://hivaidsclearinghouse.unesco.org/ev.php?ID=1565_201&ID2=DO_TOPIC.

- Poonawala S, Cantor R. Children orphaned by AIDS: A call for action for NGOs and donors. Washington DC: National Council for International Health; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Provence S, Lipton RC. Infants in institutions: A comparison of their development with family-reared infants during the first year of life. New York: International Universities Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Rando TA. Grief, dying, and death: Clinical interventions for caregivers. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Developmental catch-up, the deficit, following adoption after severe global early deprivation. English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:465–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs SE, Sachs JD. Africa’s children orphaned by AIDS. Lancet. 2004;364:1404. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safman RM. Assessing the impact of orphanhood on Thai children affected by AIDS and their caregivers. AIDS Care. 2004;16(1):11–19. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001633930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders CM. Grief: The mourning after: Dealing with adult bereavement. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BH, Atkinson L, Tardif C. Child-parent attachment and children’s peer relations: A quantitative review. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:86–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley J, Kajura E, Bachengarul C, Okongo M, Wagner U, Mulder D. The extended family and support for people with AIDS in a rural population in South-West Uganda: A safety net with holes? AIDS Care. 1993;5:117–122. doi: 10.1080/09540129308258589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengendo J, Nambi J. The psychological effect of orphanhood: A study of orphans in Rakai district. Health Transition Review. 1997;7(1):105–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Gorey E. Childhood bereavement due to parental death from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1994;15(3):S66–S70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman P, Worden JW. Children’s reactions in the early months after the death of a parent. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1992;62:93–104. doi: 10.1037/h0079304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA, Collins WA. The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth through adulthood. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Stroebe W, Schut H. Grief and loss. In: Kazdin AE, editor. Encyclopedia of Psychology. Vol. 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Kaslow NJ, Price AW, Williams K, Kingree JB. Role of secondary stressors in the parental death-child distress relation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:357–366. doi: 10.1023/a:1021951806281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman TR, Brown L, Richter L, Maharaj P, Magnani R. Sexual risk behavior among South African adolescents: Is orphan status a factor? AIDS & Behavior. 2006;10:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Children on the brink 2004: A joint report of new orphan estimates and a framework for action. New York: Author; 2004. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Van Eerdewegh M, Bieri M, Parrilla R, Clayton P. The bereaved child. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1982;140:23–29. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Weinfield NS, Hamilton CE. The stability of attachment security from infancy to adolescence and early adulthood: General discussion. Child Development. 2000;71:703–706. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Chaloner J, Bean D, Tyler S. Coping with loss: The development and evaluation of a children’s bereavement project. Journal of Child Health Care. 1998;2(2):58–65. doi: 10.1177/136749359800200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood K, Chase E, Aggleton P. “Telling the truth is the best thing:” Teenage orphans’ experiences of parental AIDS-related illness and bereavement in Zimbabwe. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:1923–1933. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worden JW. Children and grief: When a parent dies. New York: Guilford; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Worden JW, Silverman PR. Parental death and the adjustment of school-age children. Omega Journal of Death and Dying. 1996;33:91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Shimamura Y, Sserunkuuma D. Living environment and schooling of orphaned children and adolescents in Uganda (Electronic version) Economic Development and Cultural Change. 2006;54:833–856. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Wu Z, Duan S, Li Z, Li X, Shen M, Mathur A, Stanton B. Living environment and schooling of children with HIV infected parent in southwest China. AIDS Care. 2006;18(7):647–655. doi: 10.1080/09540120500282896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Li X, Fang X, Zhao J, Yang H, Stanton B. Care arrangement, grief, and psychological problems among children orphaned by AIDS in China. AIDS Care. doi: 10.1080/09540120701335220. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]