Abstract

Chromatin remodeling complexes such as the SWI/SNF complex make DNA accessible to transcription factors by disrupting nucleosomes. However, it is not known how such complexes are targeted to the promoter. For example, a SWI/SNF1-like chromatin remodeling complex erythroid Krüppel-like factor (EKLF) coactivator-remodeling complex 1 (E-RC1) disrupts the nucleosomes over the human β-globin promoter in an EKLF-dependent manner. However, it is not known whether E-RC1 is targeted specifically to the β-globin promoter or whether E-RC1 is randomly targeted, but its activity is evident only at the β-globin promoter. Because E-RC1 cannot remodel chromatin over the β-globin promoter without EKLF in vitro, it has been proposed that SWI/SNF1-like complexes such as E-RC1 are targeted specifically to the promoter by selectively interacting with promoter-associated transcription factors such as EKLF. In this report, we test this hypothesis in the cellular context by using the ProteIN POsition Identification with Nuclease Tail (PIN*POINT) assay. We find that the Brahma-related gene (BRG) 1 and BRG1-associated factor (BAF) 170 subunits of E-RC1 are both recruited near the transcription initiation site of the β-globin promoter. On transiently transfected templates, both the locus control region and the EKLF-binding site are important for their recruitment to the β-globin promoter in mouse erythroleukemia cells. When the β-globin promoter was linked to the cytomegalovirus enhancer, the E-RC1 complex was not recruited, suggesting that recruitment of the E-RC1 complex is not a general property of enhancers.

Nucleosomes suppress gene expression by preventing transcription initiation and RNA polymerase elongation (reviewed in refs. 1–3). The nucleosomes block the binding of transcription factors to DNA and are thought to act as a barrier to RNA polymerase elongation. Therefore, to initiate transcription, the nucleosome(s) blocking the promoter region needs to be disrupted. Eukaryotic cells use large complexes collectively called “chromatin remodeling complexes” to disrupt nucleosomes.

The best characterized chromatin remodeling complex is the yeast SWI/SNF complex, a 2-MDa complex composed of 9 to 12 subunits, including a catalytic subunit that utilizes ATP, SWI2 (reviewed in ref. 4). Purified yeast SWI/SNF complex and its human counterparts (5, 6) have been shown to remodel nucleosomes and help transcription factors gain access to DNA (7, 8). The ATP-utilizing subunit of the human SWI/SNF complexes is either BRG1 or BRM. If the chromatin remodeling complexes such as SWI/SNF disrupt chromatin over the promoter, it is not known whether they are targeted specifically to promoters in vivo. If targeted, recruitment is likely mediated through protein–protein interaction with transcription factors or components of the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) holoenzyme rather than through direct DNA sequence recognition, because the SWI/SNF complex does not appear to have sequence specificity in vitro (9).

There is evidence that the chromatin remodeling complexes interact either directly or indirectly with transcription factors. The glucocorticoid receptor interacts with the SWI/SNF2 complex, and chromatin remodeling by the glucocorticoid receptor requires the SWI/SNF complex (10). SWI/SNF-related erythroid Krüppel-like factor (EKLF) coactivator-remodeling complex 1 (E-RC1) was shown to disrupt chromatin over the β-globin promoter and enhance the β-globin promoter activity in an EKLF-dependent manner (11). Chromatin complexes such as ATP-utilizing chromatin assembly and remodeling factor (ACF) (12) and nucleosome remodeling factor (NURF) (13) also function in concert with a transcription factor.

In this report, we used the ProteIN POsition Identification with Nuclease Tail (PIN*POINT) assay (14) to determine whether transcription factors binding to the promoter region can recruit SWI/SNF-related complexes such as E-RC1 to the β-globin promoter in erythroid cells. We find that two subunits of the E-RC1 complex, BRG1 and BAF170 (15), are recruited to the β-globin promoter, and the recruitment requires the CACCC and TATA boxes of the β-globin promoter. Furthermore, we find that the locus control region (LCR) strongly enhances the EKLF coactivator-remodeling complex 1 (E-RC1) recruitment to the β-globin promoter, but the cytomegalovirus (CMV) enhancer does not enhance E-RC1 recruitment, suggesting that recruitment of the SWI/SNF-related complex is not a general property of enhancers. We discuss the implications of these findings in light of the recent observation that the LCR is not essential for chromatin opening of the β-globin locus.

Experimental Procedures

Construction of Plasmids.

The expression vector for the BRG1 pointer (BRG1-Fok) was made by linking human BRG1 cDNA to the nuclease domain of Fok I through a linker fragment (encoding amino acids SKISSRSAAGGGGGGGGGARL). To construct the ATPase-dead BRG1 pointer expression plasmid, a BsrG1-AscI fragment containing mutations at amino acids 783 and 784 (K to R and T to S, respectively) was inserted into the BsrG1-AscI site of the above BRG1-Fok. Pointer expression vectors for TATA-binding protein (TBP) and BAF170 were made by inserting human TBP cDNA from phTBP-ET11d and human BAF170 cDNA downstream of the FokI nuclease domain (codon optimized for expression in mammalian cells), respectively. All of the pointers used here were expressed with the CMV promoter. The target plasmids, λ-β, 5′HS234-β, 5′HS2-β, 5′HS3-β, 5′HS4-β, 5′HS23-β, 5′HS34-β, and 5′HS24-β, were previously described (14). CMV-β was constructed by amplifying the CMV enhancer region upstream of the TATA box by PCR and inserting into the XhoI-XbaI sites of pPN86. Site-directed mutagenesis of the promoter was performed with 5′HS234-β as a template, by using the Quick-Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The primers used are 5′-GCAATTTGTACTGAgctcATGGGGtCgAGAGATATATC-3′, 5′-GGTATGGGGCCAAGcttTATAcgTTAGAGGGAGG-3′, 5′-CCAACTCCTAA GtgcacGCCAGAAGA-3′ 5′-GCCAAGGGACAGGTACGGCTGTacgtACTTAGA CCTCACC-3′, 5′-CCTGTGGAGCCAaAgCtTAGGGTTGGCCAATC-3′, and 5′-CCAGGGCTGGGC gagctcGTCAGGGCAGAGC-3′ for NF-1, distal GATA-1, distal CAAT, proximal GATA-1-binding site, proximal CACCC and TATA box mutagenesis, respectively. The bases bearing the mutations are in lower-case letters. The series of 5′HS2 mutants were made by replacing the 5′HS2 region (SacI-BglII fragment) in 5′HS24-β with SacI-BglII fragments from a series of plasmids containing 5′HS2 mutations that was previously published (16).

Transfection and Isolation of DNA.

Transfection by using Effectene reagent (Qiagen) was performed as follows. Mouse erythroleukemia cells (MEL) cells (1 × 106) were washed in PBS, suspended in 1.6 ml of complete media, and added to one well of a 6-well plate. Pointer and target plasmids, 0.1 μg and 0.3 μg, respectively, were diluted in 100 μl of the DNA-condensation buffer, Buffer EC supplied by manufacturer (Qiagen). Then 8 μl of enhancer was added per μg of DNA. To the mixture, 10 μl of Effectene was added, vortexed, and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. After incubation, the mixture was supplemented with 0.6 ml complete medium and added to cells. In addition to using Effectene for transfection, we also used electroporation as described previously (14). After transfection, the MEL cells were grown in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The results shown in Fig. 3 A and D were obtained by using Effectene, and the results shown in the other figures were obtained by using electroporation. Transfected cells were harvested 24 hr after transfection, and low molecular weight DNA was isolated by a modified Hirt extraction technique as described previously (14). Briefly, the harvested cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) twice and resuspended in 500 μl of 10 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 7.4/10 mM EDTA. To this resuspension, 50 μl of 10% SDS was added, and the mixture was gently mixed. After 10 min at room temperature, 140 μl of 5 M NaCl was added and the mixture was gently mixed. The resulting mixture was then kept at 4°C overnight. After centrifugation at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min, the supernatant was collected, and 40 μg of proteinase K was added. After incubation at 50°C for 2 hr, the sample was extracted with phenol/chloroform and then with chloroform. After ethanol precipitation, the DNA was resuspended in 10 μl of distilled water.

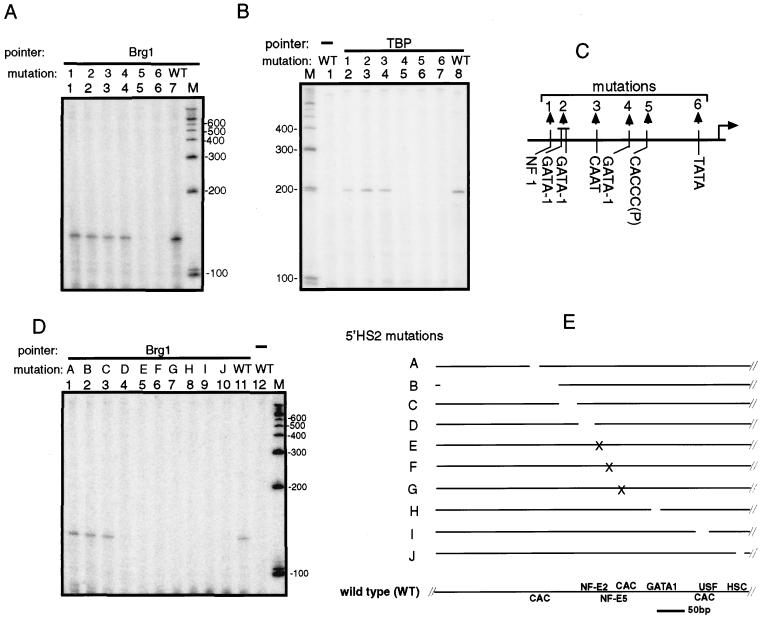

Figure 3.

An intact β-globin promoter is required for the recruitment of BRG1 pointer to the promoter. (A) A target plasmid 5′HS234-β with a site-directed mutation of different transcription factor binding sites in the β-globin promoter (see C) was cotransfected with the expression vector for the BRG1 pointer. The identity of the mutation is indicated above each lane (WT, wild type). Primer JS41 was used in primer extension for A and B. (B) The recruitment of the TBP pointer to target plasmids containing a mutation in the β-globin promoter. The lane number and the corresponding mutation number are also as described for A. (C) A diagram of the site-directed mutations in the β-globin promoter that were used in A and B. (D) Mutations shown in E were introduced into 5′HS2 of the target plasmid 5′HS24-β, and the effect of the mutation on the recruitment of BRG1 pointer to the β-globin promoter was analyzed as in A. Primer JS41 was used for primer extension. (E) A diagram of the 5′HS2 mutations used in D. Gaps indicate deletions and x indicates substitution with a random sequence. These mutations were previously published (16). The locations of the transcription factor-binding sites in 5′HS2 are shown below.

Primer Extension.

DNA (1 μl), isolated as described above, was denatured with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide in a volume of 5 μl by heating to 94°C for 3 min and quickly freezing on dry ice. Primer extensions were performed in 1x ThermoPol reaction buffer (NEB, Beverly, MA), 0.25 mM of each dNTP/6 mM MgSO4/25 μM 5′ end-labeled primer/0.4 units of Vent exonuclease-negative polymerase (NEB) at 72°C for 5 min after heating to 94°C for 5 min and annealing at 70°C for 5 min. Primers JS41 (5′-GGCATTTCAGTCAGTTGCTCAATGTACC-3′) or JS42 (5′-TACGATGCCATTGG GATATATCAACGGTGG-3′) were used for the promoter region. The extended products were electrophoresed on a 6% Sequagel (National Diagnostics) containing urea in 90 mM Tris/64.6 mM boric acid/2.5 mM EDTA, pH 8.3. The gel was dried and exposed to a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) screen, which was scanned by using a STORM PhosphorImager. The cleavage sites in the promoter were determined by running the primer extension samples next to a DNA sequencing ladder generated with the same primer.

Chloramphenicol Acetyltransferase (CAT) Assay.

CAT assays were performed as described previously (17).

Results and Discussion

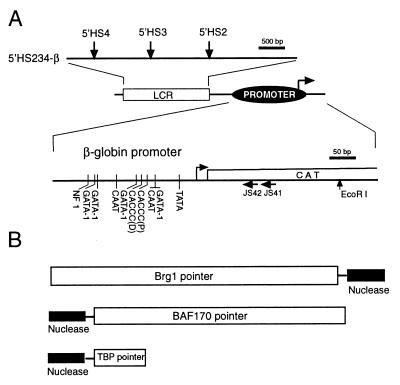

The composition of the E-RC1 complex is almost identical to that of SWI/SNF, but the E-RC1 activity cannot be substituted by the SWI/SNF complex, suggesting that they are distinct complexes (11). They both contain BRG1, the human homologue of SWI2/SNF2, and BAF170, among other subunits. To detect the recruitment of the E-RC1 complex to the β-globin promoter, we used the PIN*POINT assay that was recently described (14). This assay begins by transiently transfecting two plasmids into MEL cells: the expression vector of BRG1 (or BAF170) pointer, a fusion protein consisting of BRG1 (or BAF170) protein attached to the nuclease domain of the restriction endonuclease FokI through a flexible linker (Fig. 1B) and the target plasmid containing the β-globin promoter linked to the β-globin LCR (Fig. 1A). Once the pointer protein is expressed in cells and recruited to DNA, the nuclease domain of the pointer (nuclease tail) marks its position on the target plasmid by cleaving the DNA. A useful feature of the PIN*POINT assay is that the nuclease tail of pointers that do not bind DNA directly but are recruited to DNA by interacting with DNA binding proteins can also cleave DNA. This is important for studying the recruitment of chromatin-remodeling complexes, because some of their subunits may not bind DNA directly. The position and intensity of cleavage is determined by primer extension with a radioactively labeled primer specific for the region of interest (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Diagram of the target plasmid 5′HS234-β. The positions of the 5′HS of the β-globin LCR (downward arrows), as well as the primers used for primer extensions (horizontal arrows), are shown. The positions of the characterized transcription factor-binding sites in the β-globin promoter are indicated with vertical lines. (B) Structures of BRG1, BAF170, and TBP pointers are shown. The nuclease domain of Fok I endonuclease (black rectangle) was fused to the C terminus of BRG1 or mutated BRG1 [K783 and T784 to R and S, respectively (5)], BRG1(M), or to the N terminus of BAF170 or TBP to generate the respective pointers.

Because it is not known how the E-RC1 complex differs from the SWI/SNF complex, we cannot distinguish the recruitment of the E-RC1 complex from the recruitment of SWI/SNF or other SWI/SNF-related complexes. But, because the E-RC1 complex but not the SWI/SNF complex, has already been demonstrated to remodel the chromatin over the β-globin promoter and activate β-globin expression (11), we will refer to the BRG1-containing complex as the E-RC1 complex.

Although transiently transfected DNA might not be assembled into chromatin, if transcription factors bound to the promoter region recruit E-RC1 to the endogenous β-globin locus, such recruitment is likely to take place on the transiently transfected DNA as well. Therefore, studying how chromatin-remodeling complexes are recruited to transiently transfected DNA should reveal valuable information on their recruitment to the endogenous locus.

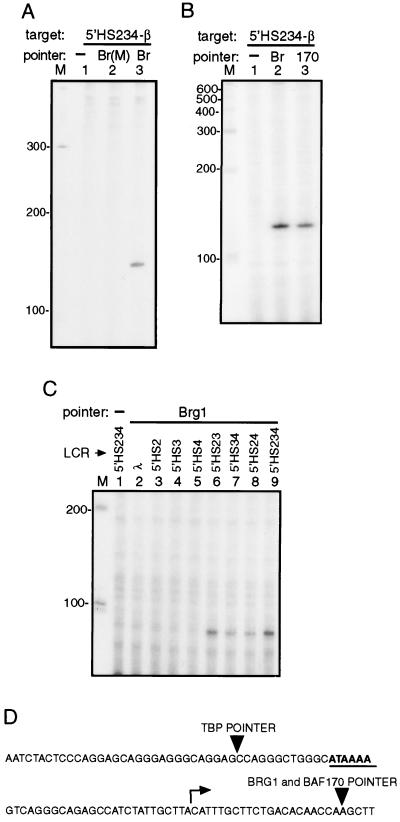

With the PIN*POINT assay, we found that the wild-type BRG1 pointer cleaved 22 bp 3′ of the transcription initiation site of the β-globin promoter (132-bp band in lane 3) (Fig. 2A, lane 3). The mutant BRG1 pointer, which is ATPase inactive, did not cleave the β-globin promoter (lane 2) even though it was expressed to a similar level as the wild-type BRG1 pointer (data not shown). At this point, we have no explanation for the role of the ATPase activity in its recruitment. Nevertheless, the result shown in Fig. 2A suggests that the BRG1 pointer is targeted to the β-globin promoter region.

Figure 2.

PIN*POINT assay of the recruitment of BRG1 and BAF170 pointers to the β-globin promoter. (A) The expression vectors for mutated BRG1 [Br(M), lane 2], and BRG1 (Br, lane 3) pointers were cotransfected with the target plasmid 5′HS234-β into MEL cells. After isolating the target plasmid 24 hr later, recruitment to the β-globin promoter was detected with primer extension by using primer JS41 (Fig. 1A). No expression vector for a pointer was used in lane 1 (−). The lane with radioactively labeled size marker (in base pairs) is indicated with M. (B) The recruitment of BRG1 (lane 2) and BAF170 (lane 3) pointers to the β-globin promoter was detected as described for A. (C) The recruitment of BRG1 pointer to the β-globin promoter requires two or more 5′HS. Target plasmids with different combinations of 5′HS (shown above each lane) placed upstream of the β-globin promoter were transfected with the expression vector for BRG1 pointer. λ indicates a λ-phage DNA fragment in place of the LCR. Cleavage by BRG1 pointer was detected by primer extension with primer JS42, which detects a 91-bp band, because it was derived from a sequence 41 bp upstream of the sequence from which JS41 was derived. (D) A schematic diagram showing the cleavage sites for BRG1, BAF170, and TBP (see Fig. 3C) pointers in the β-globin promoter as determined against a sequence ladder. The TATA box is underlined (and in bold), and the transcription initiation site is marked with a bent arrow.

BRG1 is one of at least eight subunits of the E-RC1 complex. If the BRG1 pointer is recruited to the β-globin promoter as part of the E-RC1 complex, other subunits of the complex such as BAF170 (15) should be recruited to the same site as the BRG1 pointer. The experiment shown in Fig. 2A was repeated with an expression vector for BAF170 pointer and, as shown in Fig. 2B, BRG1 (lane 2) and BAF170 pointers (lane 3) cleave the same site in the β-globin promoter. These findings suggest that the E-RC1 complex may be targeted to the β-globin promoter.

It is interesting that BRG1 and BAF170 pointers cleave the identical site. Like other nucleases without sequence specificity, such as DNase I (18) and micrococcal nuclease (19), the nuclease domain of Fok 1 endonuclease (20) is likely to cleave certain sites more efficiently than others. Such preference, combined with the constraints of the local DNA-protein architecture inside the short region that is within the reach of the nuclease domain of BRG1 and BAF170 pointers, may cause the two pointers to cleave the identical site.

The LCR, which consists of four DNase I-hypersensitive sites (5′HS1–4) located over 50 kilobases upstream of the β-globin gene, confers high and position-independent expression of the β-globin family of genes (21, 22). Because chromatin represses transcription by blocking access of DNA-binding factors and by blocking elongation by RNA polymerase II, the fact that the LCR confers high and position-independent expression implies that it is able to disrupt chromatin. Indeed, as a consequence of a naturally occurring deletion that removes the LCR in Hispanic thalassemia, the chromatin of the β-globin domain becomes condensed, the DNase I-hypersensitive site over the β-globin promoter disappears, and β-globin expression is suppressed (23). The activity of the 5′HSs is additive, and full expression of the β-globin gene cluster requires all 5′HSs (24–29). The individual DNase I-hypersensitive sites (5′HS) of the LCR may also synergize in activating β-globin expression in transgenic mice (30, 31). To determine the role of the individual 5′HS in BRG1 pointer recruitment to the β-globin promoter λ-phage DNA, 5′HS2 through 4, either individually or pairwise were linked to the β-globin promoter (Fig. 2C). We detected very little cleavage in the β-globin promoter linked to the λ-phage DNA or to the individual 5′HS2, 3, or 4, but detected significant cleavage in the β-globin promoter linked to at least two of the three 5′HS in any combination (compare lanes 6–8 with lane 9). This finding is consistent with the observation that one 5′HS is insufficient to confer position-independent expression of the β-globin gene in transgenic mice with a single copy insertion (32).

To identify the cis-acting element(s) that is important for the recruitment of the BRG1 pointer, we introduced site-directed mutations (see Fig. 3C) into the transcription factor-binding sites of the β-globin promoter. The PIN*POINT assay shows that the BRG1 pointer is not recruited to the target plasmid containing the CACCC box or the TATA box mutation (Fig. 3A). The CACCC box and the TATA box are also required for the recruitment of the EKLF pointer and the activity of the β-globin promoter (33). This finding is consistent with the in vitro observation that E-RC1 requires EKLF for remodeling the chromatin over the β-globin promoter (11).

We also analyzed the promoter elements required to recruit the TBP (reviewed in ref. 34) for comparison. The expression vector for the TBP pointer (see Fig. 1B) and the target plasmid containing the promoter mutations used above was cotransfected and the PIN*POINT assay performed. We find that the TBP pointer recruitment was significantly decreased only by mutations in the GATA-1 binding site and the proximal CACCC and TATA boxes of the β-globin promoter (Fig. 3B).

To determine which cis-acting elements in 5′HS2 are essential for BRG1 pointer recruitment to the β-globin promoter, a series of site-specific mutations (see Fig. 3E) of transcription factor-binding sites was introduced into 5′HS2 of the target plasmid 5′HS24-β, which contains 5′HS2 and HS4 linked to the β-globin promoter. The recruitment of the BRG1 pointer was not affected by mutations A-C, which abolish the recruitment of EKLF to the 5′-most CACCC box (data not shown) but was abolished by mutations D-J (Fig. 3D). All these mutations have been shown to decrease the β-globin expression to varying degrees but mutation E, which destroys the NF-E2 binding site, decreases the β-globin expression most severely (16).

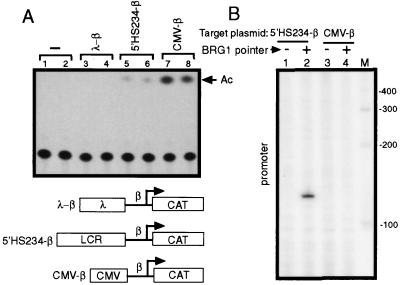

Because the BRG1 pointer cleavage site in the β-globin promoter is 22 bp 3′ of the transcription initiation site, it is possible that the BRG1 pointer is recruited through an interaction with Pol II. Indeed, it has been reported that the yeast SWI/SNF complex is a component of the Pol II holoenzyme (35). However, this remains controversial, as other groups have failed to detect this association (36, 37). One possible reason for the inconsistency may be that the SWI/SNF–Pol II holoenzyme interaction is unstable or transient, and the ability to detect it may depend on the method of purification used. If the E-RC1 complex is a general component of the Pol II holoenzyme in vivo, the BRG1 pointer should be recruited to other transcriptionally active promoters. To search for a strong enhancer that was able to activate the β-globin promoter, we tested a series of enhancers by placing them upstream of the β-globin promoter joined to the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene reporter construct and found that the CMV enhancer (38) produced the strongest reporter activity in MEL cells, stronger than the LCR (Fig. 4A). However, in the PIN*POINT assay, we could detect no BRG1 recruitment to the β-globin promoter when it was linked to the CMV enhancer (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the E-RC1 complex is not a general component of the Pol II holoenzyme. This conclusion is consistent with the observation that the bulk of Pol II and BRG1 generally do not colocalize in immunofluorescence studies (39).

Figure 4.

The CMV enhancer activates the β-globin promoter but does not recruit the BRG1 pointer. (A) Reporter constructs (10 μg) in which the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene was driven by the β-globin promoter linked to either a λ-phage DNA (λ-β) (lanes 3 and 4), 5′HS234 (5′HS234-β) (lanes 5 and 6), or the CMV enhancer (CMV-β) (lanes 7 and 8) were transfected into MEL cells, and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase assays were performed 48 hr later. Acetylated chloramphenicol is indicated as Ac. Mock transfection was performed in lanes 1 and 2. (B) BRG1 PIN*POINT analysis was performed with 5′HS234-β (lanes 1 and 2) and CMV-β (lanes 3 and 4) reporter constructs as target plasmids. Primer JS41 was used for primer extension. The BRG1 pointer was expressed in lanes 2 and 4 (+), but not in lanes 1 and 3 (−).

The finding that recruitment of the E-RC1 complex depends on promoter-bound transcription factors in our study appears to run contrary to the current thinking that transcription factors depend on the chromatin remodeling complex to gain access to DNA in a chromatinized template. However, it has been shown that in yeast, the binding of the yeast transcriptional activator GAL4 to a site in a positioned nucleosome is not appreciably affected in a SWI/SNF mutant, but the transcriptional activation step subsequent to transcriptional activator-promoter recognition was impaired (40). In a similar fashion, transcriptional activator(s) may gain access to the β-globin promoter in a chromatinized template without E-RC1, after which they may participate in the recruitment of E-RC1 for the subsequent transcriptional activation step.

Our report provides evidence that the SWI/SNF-related complex(es), possibly E-RC1, may be recruited to the promoter through protein–protein interactions involving the transcription factors bound to the promoter region and to the LCR. Because the pointer is overexpressed, and the target plasmid is not integrated into chromatin in this assay, it is possible that not all aspects of in vivo protein recruitment are accurately reflected by the PIN*POINT assay.

It has recently been shown that a deletion of the native β-globin LCR did not significantly affect the general DNase I sensitivity or developmentally regulated transcription of the mouse β-globin locus (41). Without the LCR, however, the level of transcription was reduced 4- to 20-fold. These findings indicate that the LCR is not the dominant chromatin opening element of the β-globin locus but functions more like an enhancer. This conclusion does not contradict our observation that the LCR recruits the chromatin remodeling complex such as E-RC1 to the β-globin promoter. The fact that E-RC1 is targeted to the promoter is consistent with its role in enhancing transcription by selectively remodeling the chromatin of the promoter region rather than in remodeling the chromatin of the β-globin locus globally. Efforts are under way to examine whether E-RC1 or another SWI/SNF-related complex is recruited to the endogenous β-globin promoter.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Paul Khavari, Gerald Crabtree, Weidong Wang, Robert Roeder, and Tim Townes for the plasmids. We also thank Dr. David Levens and the members of Dr. Jay Chung’s laboratory for helpful comments.

Abbreviations

- LCR

locus control region

- EKLF

erythroid Krüppel-like factor

- E-RC1

EKLF coactivator-remodeling complex 1

- PIN*POINT

ProteIN POsition Identification with Nuclease Tail

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- MEL

mouse erythroleukemia cells

- Pol II

RNA polymerase II

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Kornberg R D, Lorch Y. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:563–587. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felsenfeld G. Cell. 1996;86:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kingston R E, Bunker C A, Imbalzano A N. Genes Dev. 1996;10:905–920. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winston F, Carlson M. Trends Genet. 1992;8:387–391. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90300-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khavari P A, Peterson C L, Tamkun J W, Mendel D B, Crabtree G R. Nature (London) 1993;366:170–174. doi: 10.1038/366170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muchardt C, Yaniv M. EMBO J. 1993;12:4279–4290. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imbalzano A N, Kwon H, Green M R, Kingston R E. Nature (London) 1994;370:481–485. doi: 10.1038/370481a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon H, Imbalzano A N, Khavari P A, Kingston R E, Green M R. Nature (London) 1994;370:477–481. doi: 10.1038/370477a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinn J, Fyrberg A M, Ganster R W, Schmidt M C, Peterson C L. Nature (London) 1996;379:844–847. doi: 10.1038/379844a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fryer C J, Archer T K. Nature (London) 1998;393:88–91. doi: 10.1038/30032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong J A, Bieker J J, Emerson B M. Cell. 1998;95:93–104. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81785-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito T, Bulger M, Pazin M J, Kobayashi R, Kadonaga J T. Cell. 1997;90:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsukiyama T, Becker P B, Wu C. Nature (London) 1994;367:525–532. doi: 10.1038/367525a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J S, Lee C H, Chung J H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:969–974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang W, Xue Y, Zhou S, Kuo A, Cairns B R, Crabtree G R. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2117–2130. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.17.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caterina J J, Ciavatta D J, Donze D, Behringer R R, Townes T M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1006–1011. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorman C M, Moffat L F, Howard B H. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt G, Cashion P J, Suzuki S, Joseph J P, Demarco P, Cohen M B. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1972;149:513–527. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(72)90351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sollner-Webb B, Felsenfeld G. Biochemistry. 1975;14:2915–2920. doi: 10.1021/bi00684a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L, Wu L P, Chandrasegaran S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4275–4279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin D I, Fiering S, Groudine M. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:488–495. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orkin S H. Eur J Biochem. 1995;231:271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forrester W C, Epner E, Driscoll M C, Enver T, Brice M, Papayannopoulou T, Groudine M. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1637–1649. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navas P A, Peterson K R, Li Q, Skarpidi E, Rohde A, Shaw S E, Clegg C H, Asano H, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4188–4196. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li G, Lim K C, Engel J D, Bungert J. Genes Cells. 1998;3:415–429. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ley T J, Hug B, Fiering S, Epner E, Bender M A, Groudine M. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;850:45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson K R, Clegg C H, Navas P A, Norton E J, Kimbrough T G, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6605–6609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bungert J, Dave U, Lim K C, Lieuw K H, Shavit J A, Liu Q, Engel J D. Genes Dev. 1995;9:3083–3096. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.24.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiering S, Epner E, Robinson K, Zhuang Y, Telling A, Hu M, Martin D I, Enver T, Ley T J, Groudine M. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2203–2213. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser P, Pruzina S, Antoniou M, Grosveld F. Genes Dev. 1993;7:106–113. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milot E, Strouboulis J, Trimborn T, Wijgerde M, de Boer E, Langeveld A, Tan-Un K, Vergeer W, Yannoutsos N, Grosveld F, et al. Cell. 1996;87:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellis J, Talbot D, Dillon N, Grosveld F. EMBO J. 1993;12:127–134. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee J-S, Lee C-H, Chung J H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10051–10055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buratowski S. Cell. 1997;91:13–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson C J, Chao D M, Imbalzano A N, Schnitzler G R, Kingston R E, Young R A. Cell. 1996;84:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80978-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cairns B R, Kim Y J, Sayre M H, Laurent B C, Kornberg R D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1950–1954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cote J, Quinn J, Workman J L, Peterson C L. Science. 1994;265:53–60. doi: 10.1126/science.8016655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foecking M K, Hofstetter H. Gene. 1986;45:101–105. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reyes J C, Muchardt C, Yaniv M. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:263–274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan M P, Jones R, Morse R H. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1774–1782. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epner E, Reik A, Cimbora D, Telling A, Bender M A, Fiering S, Enver T, Martin D I, Kennedy M, Keller G, et al. Mol Cell. 1998;2:447–455. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]