Abstract

We evaluated infection of Aedes taeniorhynchus mosquitoes, vectors of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV), using radiolabeled virus and replicon particles expressing green (GFP) or cherry fluorescent protein (CFP). More epidemic VEEV bound to and infected mosquito midguts compared to an enzootic strain, and a small number of midgut cells was preferentially infected. Chimeric replicons infected midgut cells at rates comparable to those of the structural gene donor. The numbers of midgut cells infected averaged 28, and many infections were initiated in only 1-5 cells. Infection by a mixture of GFP- and CFP-expressing replicons indicated that only about 100 midgut cells were susceptible. Intrathoracic injections yielded similar patterns of replication with both VEEV strains, suggesting that midgut infection is the primary limitation to transmission. These results indicate that the structural proteins determine initial infection of a small number of midgut cells, and that VEEV undergoes population bottlenecks during vector infection.

Keywords: alphavirus, mosquito, evolution, pathogenesis, genetics

INTRODUCTION

Arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) infect vertebrate hosts through horizontal transmission by mosquito vectors following their oral infection via a viremic bloodmeal. The bloodmeal is directed to the posterior midgut of the mosquito, where the arbovirus must infect and replicate within the midgut epithelial cells. From the midgut, the virus must cross the basal lamina to enter the hemocoel, the open body cavity that contains important secondary amplification tissues such as the fat body, nervous system, and salivary glands. Following salivary gland infection and secretion of replicated virus into the saliva, the mosquito can transmit virus to a naïve vertebrate host when ingesting a subsequent bloodmeal.

Certain mosquito species are refractory to oral infection with some, but not other arboviruses. This variable susceptibility and ability to transmit virus depends on several “barriers” or abortive stages of infection. In the posterior midgut, the virus encounters its first potential barrier--the ability to productively infect midgut epithelial cells. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the species-specific refractoriness of midgut epithelial cells to infection, including: 1) diversion of the blood and virus into the ventral diverticulum, a chitin-lined sac used for carbohydrate nutrient storage; 2) filtration of virus by the peritrophic matrix, a chitinous sac secreted by the midgut epithelium during blood digestion; 3) inactivation of virions by midgut digestive enzymes; 4) virus-midgut cell charge interactions that preclude binding, and; 5) the absence of appropriate receptors on the apical surfaces of epithelial cells. Hypotheses 1-4 have not received experimental support (Hardy et al., 1983), whereas hypothesis 5 has been supported by the studies discussed below.

Houk et al. (Houk et al., 1990) provided evidence that specific receptors on the midgut epithelium may be responsible for differences in oral infection by western equine encephalitis virus, which binds isolated midgut brush border membrane fragments with higher affinity in susceptible rather than refractory mosquito strains (Houk et al., 1990). Further evidence of the importance of midgut epithelial receptors was provided by Mourya et al., who identified 2 proteins from brush border membranes of Aedes aegypti midguts that are linked to susceptibility to chikungunya virus infection (Mourya et al., 1998). The 38 and 60 kDa proteins were found to be in lower concentrations in refractory mosquitoes when compared to susceptible strains.

Viral determinants of mosquito midgut infection have been studied for alphaviruses, flaviviruses, bunyaviruses and orbiviruses (Ludwig et al., 1989; Ludwig et al., 1991; Mertens et al., 1996; Molina-Cruz et al., 2005; Myles et al., 2003; Pierro et al., 2003; Woodward et al., 1991; Xu et al., 1997). For alphaviruses, the only determinant of midgut infection identified to date is the E2 envelope glycoprotein, which forms spikes on the virion surface (Pletnev et al., 2001) and probably interacts with cellular receptors. The E2 protein was found to be a major determinant of Ae. aegypti midgut infection by Sindbis virus (Myles et al., 2003; Pierro et al., 2003). A monoclonal antibody-resistant mutant of the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV; Togaviridae: Alphavirus) TC-83 vaccine strain with a single amino acid substitution in the E2 protein gene exhibited reduced infection of and dissemination from the midgut of Ae. aegypti (Woodward et al., 1991). Brault et al. also demonstrated that other mutations in the E2 envelope glycoprotein enhanced the ability of enzootic VEEV strains to infect the epidemic mosquito vector, Ae. taeniorhynchus when the E2 mutations resembled the epizootic virus genotype (Brault et al., 2004; Brault et al., 2002).

Although these previous results suggest that mosquito infectivity is determined by specific midgut-alphavirus interactions, such associations have not been studied in detail using different VEEV subtypes and strains. VEEV also warrants further study because it is an important reemerging arbovirus that causes periodic explosive epidemics, such as the 1995 outbreak in Venezuela and Colombia that affected about 100,000 people (Rivas et al., 1997; Weaver et al., 1996). Ae. taeniorhynchus, a saltmarsh species implicated in major coastal VEE outbreaks ranging from northern South America to Texas, is probably the most important epidemic vector (Weaver et al., 2004). Because Ae. taeniorhynchus is more susceptible to most epidemic than to enzootic VEEV strains, it provides an important model vector for understanding the role of adaptation in VEE emergence as well as for studying alphavirus-mosquito interactions.

We hypothesized that interactions of VEEV with receptors on the midgut epithelial cells determine the ability of epidemic versus endemic strains of VEEV to infect Ae. taeniorhynchus and transmit virus. To test this hypothesis, we used purified VEEV labeled with [3H] uridine to assess virus binding to mosquito midguts, and replicon-containing virus-like particles expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) to identify sites of initial infection. We also assessed the role of the nonstructural versus structural protein genes of VEEV in initial midgut cell infection and subsequent replication. The susceptibility of midgut cell populations to VEEV was assessed by orally exposing mosquitoes to a mixture of replicon particles expressing either the cherry fluorescent protein (CFP) or GFP to determine if midgut epithelial cells could be co-infected with more than one replicon particle. Additionally, replicon particles were injected intrathoracically (IT) to determine whether midgut infection is the only major barrier to the transmissibility of epidemic versus enzootic VEEV strains. The results of this study reveal important insights of the virus-vector interactions that occur for successful transmission of epidemic VEEV.

RESULTS

VEEV Binding in Mosquito Midguts

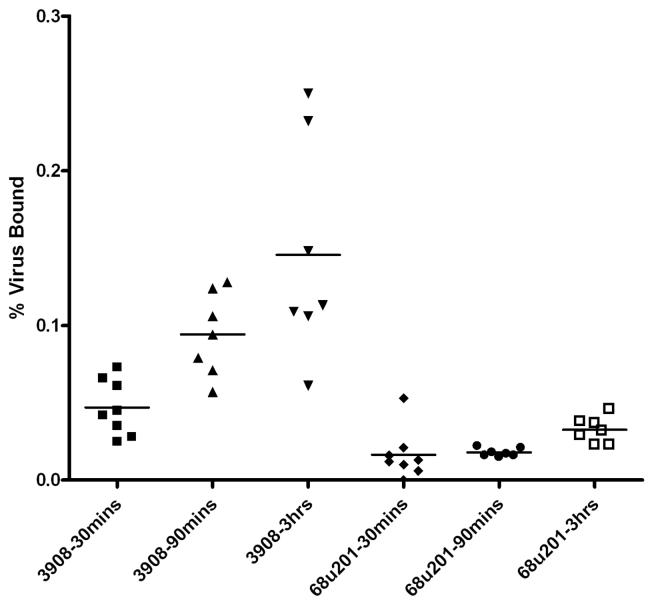

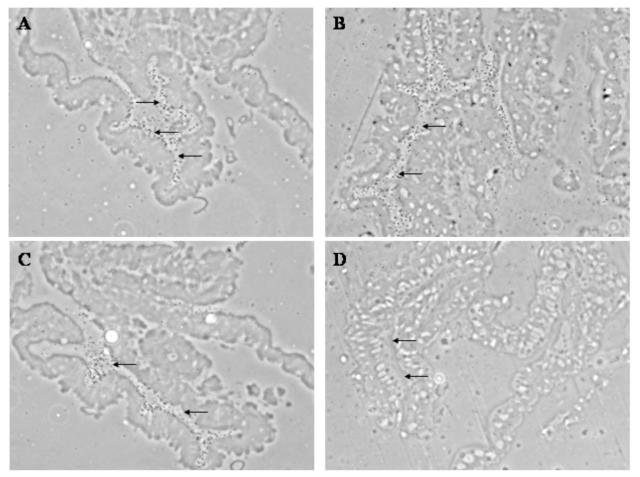

To determine whether the VEEV subtypes exhibit differential midgut binding, Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes were fed high titer bloodmeals containing radiolabeled epidemic or enzootic strain. At all time points measured after feeding, significantly more epidemic VEEV strain 3908 bound to midguts compared to enzootic strain 68U201 (30 min: p=0.0015; 90 min: p<0.0001, 3 h: p=0.0006; Fig. 1). The difference in binding between the epidemic and enzootic strains occurred in 2 independent experiments (data not shown). For both virus strains, the percentage of virus that bound to the midgut increased over time, and all scintillation counts for both virus strains were significantly above background counts (from uninfected, engorged mosquitoes) at all time points PI. Autoradiography qualitatively confirmed greater binding of VEEV strain 3908 to the midgut compared to strain 68U201 (Fig. 2). A large number of strain 3908 virus particles were concentrated along the luminal brush border of the midgut (Fig. 2A-C), but no concentration of strain 68U201 virus particles occurred in the midgut (Fig. 2D). The absence of virus binding to the basal (hemocoel) side of the midgut confirmed the lack of non-specific virus binding to the outer, basal surface of the midgut, a potential artifact of the dissection and processing of midguts.

Figure 1.

Percentage of [3H]-labeled virus bound to the midgut of Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes following oral infection with VEEV strains 3908 and 68U201. Each cohort represents VEEV strain and time PI. The horizontal line represents the geometric mean.

Figure 2.

Autoradiography of Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes infected orally with [3H]-labeled VEEV strain 3908 (A-C) and 68U201 (D) at 3 h PI. Arrows point to the lumen of the midgut.

To determine if virus stability in the midgut lumen could be responsible for differences in infection, the infectious titers of strain 3908 were compared to those of strain 68U201 after ingestion of bloodmeals containing 7.5 log10 PFU/mL. At 30 minutes, 90 minutes, and 3 h PI, there were no significant differences in infectious titers between strains 3908 and 68U201 (data not shown). These results suggest that differential binding of epidemic and endemic strains of VEEV to the midgut epithelium is not related to the stability of the virus in the midgut lumen.

Primary Sites of VEEV Replication in Orally Infected Mosquitoes

To identify primary sites of replication, Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes were orally exposed to either epidemic or enzootic VEEV replicon particles expressing GFP. The replicon particles, which are nearly identical structurally to wild-type virus, infect cells via natural receptor interactions. However, they replicate only in the initial cells they infect because they lack the structural protein genes required for spread.

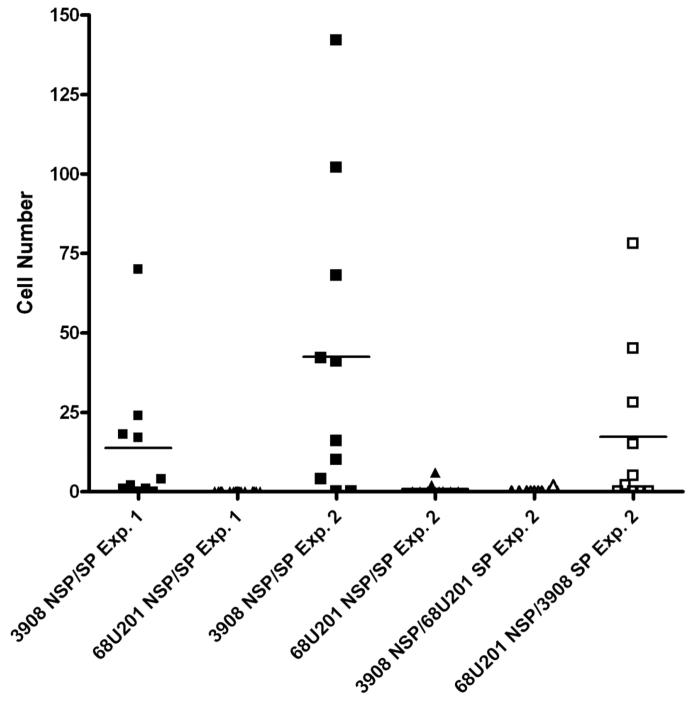

In two independent experiments, GFP fluorescence was detected in 80% (16/20) of midguts of mosquitoes fed epidemic strain 3908 replicon particles compared to significantly fewer [6.7% (2/30)] midguts of mosquitoes fed enzootic strain 68U201 [(p<0.0001), (Fig. 3)]. Mosquitoes infected in a second experiment were slightly more susceptible to infection compared to those in the first experiment, but the comparison of enzootic and epidemic strains were comparable. In the first experiment, even when mosquitoes ingested a strain 68U201 bloodmeal with a 10-fold higher titer than that of strain 3908 (9 versus 8 log10 FFU/ml), GFP was not detected. However, in the second experiment, GFP was detected in a few midgut cells of mosquitoes ingesting a strain 68U201 bloodmeal with a titer of 8 log10 FFU/ml. Similarly, mosquitoes fed epidemic strain 3908 replicon particles in the second experiment had a higher number of midgut epithelial cells infected when compared to the first experiment, but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.102).

Figure 3.

The number of GFP-expressing Ae. taeniorhynchus midgut epithelial cells following oral infection with VEEV strain 3908 or strain 68U201 replicon particles from 2 independent experiments. Horizontal line represents the geometric mean. NSP = nonstructural proteins; SP = structural proteins.

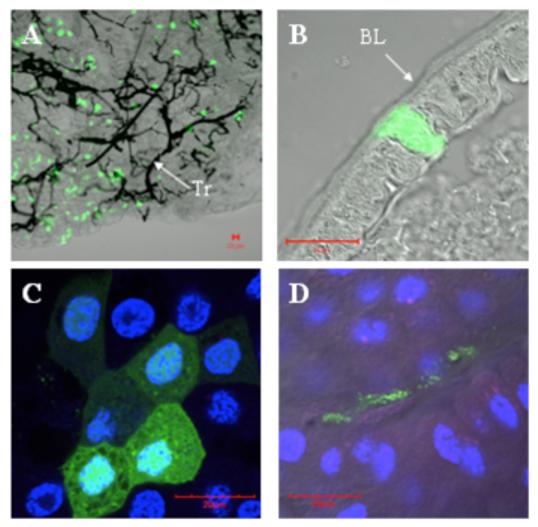

The number of infected midgut epithelial cells in mosquitoes that ingested epidemic strain 3908 replicon particles in both experiments was highly variable, ranging from 1 to 142 with a mean of 28 (n=20; Fig. 3). This high variability was similar to that observed for the percentage of virus bound to the midgut (Fig. 1). Confocal micrographs of the epithelial cells expressing GFP (Fig. 4) show the variation in the observed number of infected cells, which ranged from a large number of cells (Fig. 4A) or a single infected cell (Fig. 4B). Sometimes the infected cells were observed in clusters (Fig. 4C), suggesting preferential infection for a certain group of epithelial cells or anatomic location. Besides midgut epithelial cells, the only other cells observed to be expressing GFP were small, unidentified cells in the posterior midgut of a few samples (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Confocal micrographs of midguts from Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes orally infected with VEEV 3908 replicon particles. Transmitted image is overlayed with GFP fluorescent image (except for C). DAPI staining was added for images C and D. A) Dissected posterior midgut where numerous GFP-expressing epithelial cells were detected. Tr = treacheoles, which appear black in the transmitted image. B) Single infected posterior midgut epithelial cell from a whole mosquito section. BL = basal lamina. C) Cluster of posterior midgut epithelial cells expressing GFP at high magnification. D) Unidentified cells expressing GFP in the posterior midgut. Red bar in lower corners = 20μm.

To assess the role of nonstructural versus structural protein genes in initial midgut cell infection and replication, chimeric GFP-expressing replicons were made using nonstructural proteins from one strain and structural proteins from the other strain and vice versa. As expected, the source of the structural proteins appeared to determine the outcome of infection; no significant differences were found in the number of midgut cells expressing GFP in mosquitoes infected with replicon particles containing the same structural protein compliment (wild-type or chimeric): epidemic strain 3908 nonstructural/structural proteins vs. chimeric enzootic strain 68U201 nonstructural/epidemic strain 3908 structural proteins (p=0.164); enzootic strain 68U201 nonstructural/structural proteins vs. epidemic strain 3908 nonstructural/enzootic strain 68U201 structural proteins, (p=0.684; see Fig. 3).

Whole, orally infected mosquitoes were sectioned to determine if the primary site of replication may occur in sites outside of the midgut (i.e., hemocoel). As expected, no GFP was detected outside of the midgut (data not shown), suggesting that midgut epithelial cells are the primary sites of viral replication in orally infected mosquitoes.

Primary Sites of VEEV Replication in Intrathoracically Infected Mosquitoes

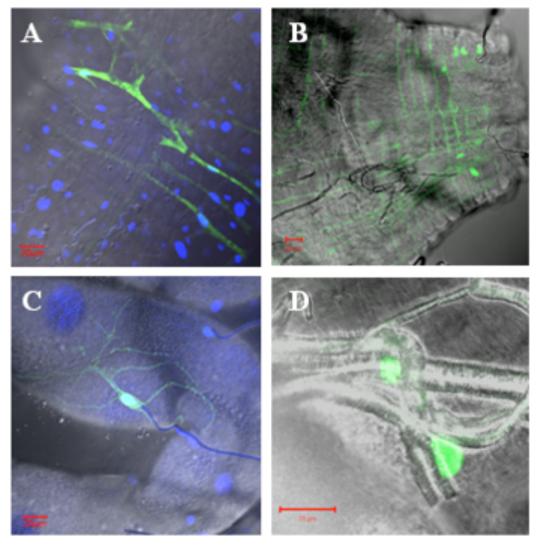

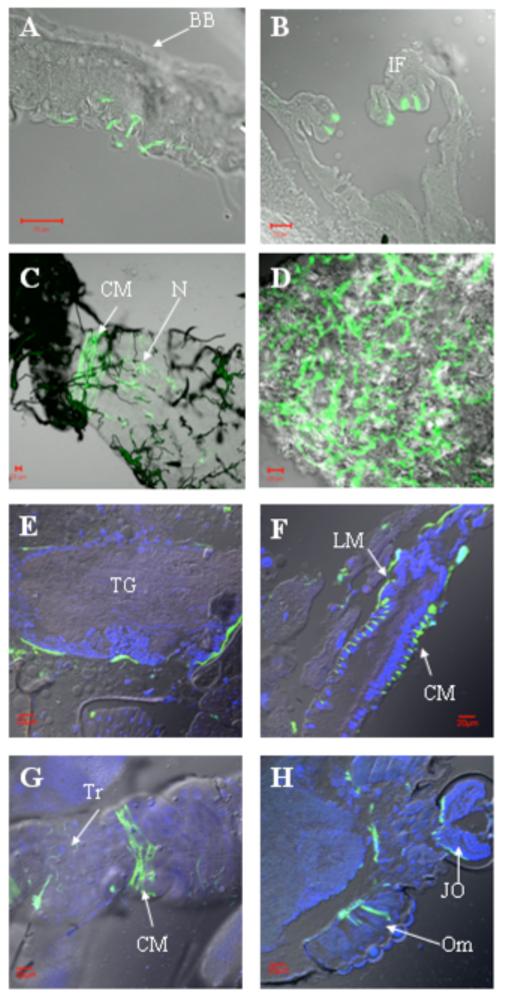

To identify primary sites of replication following virus dissemination from the midgut, mosquitoes were injected IT with either epidemic or enzootic VEEV replicon particles expressing GFP. Fluorescence was detected in 100% (20/20) of mosquitoes injected with epidemic strain 3908 and 80% (16/20) injected with enzootic strain 68U201, with no significant difference between strains (p=0.106, Fisher’s exact test). For both virus strains, anterior midgut muscles, fat body, tracheal and nerve cells associated with the midgut and malphigian tubules were most often infected (see examples in Fig. 5). More GFP-expressing cells were observed in mosquitoes injected with strain 3908 replicons compared to strain 68U201 (Table 1). However, the posterior midgut, hindgut, ventral diverticulum muscles, intussuscepted foregut, and nervous tissues were not infected by the enzootic strain 68U201 replicon particles. Additional organs infected by strain 3908 included muscles of the posterior midgut, hindgut and diverticulum, sense organs (Johnston’s organ and ommatidia of the compound eyes), ganglionic connectives such as in the thoracic ganglia, and epithelial cells of the intussuscepted foregut (Table 1, Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Confocal micrographs of dissected tissues from Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes IT infected with GFP-expressing VEEV strain 3908 (A and B) and strain 68U201 (C and D) replicon particles. Transmitted image is overlayed with GFP fluorescent image. DAPI staining was added for images A and C. A) Circular muscles of the anterior midgut expressed GFP. B) Circular and longitudinal muscles of the posterior midgut expressed GFP. C) Tracheoles associated with the Malpighian tubules expressed GFP. D) Cells associated with the tracheoles of the midgut expressed GFP. Red bar in lower corners = 20μm.

Table 1.

Percentage of Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquito tissues infected (based on the presence of GFP expression) by intrathoracic injection of VEEV strain 3908 or strain 68U201 replicon particles

| Virus strain |

||

|---|---|---|

| Mosquito tissue | Epidemic 3908 | Enzootic 68U201 |

| Anterior Midgut Muscles | 100% (20/20) | 80% (16/20) |

| Posterior Midgut Muscles | 100% (20/20) | 0% (0/20) |

| Hindgut Muscles | 100% (20/20) | 0% (0/20) |

| Ventral Diverticulum Muscles | 100% (20/20) | 0% (0/20) |

| Intussuscepted Foregut | 25% (5/20) | 0% (0/20) |

| Tracheal Cells Associated with Midgut | 45% (9/20) | 15% (3/20) |

| Tracheal Cells Associated with Malpighian Tubules | 100% (20/20) | 45% (9/20) |

| Tracheal Cells Associated with the Ovaries | 40% (8/20) | 30% (6/20) |

| Nerves Associated with the Midgut | 40% (8/20) | 15% (3/20) |

| Ganglionic Connectives* | 100% (10/10) | 0% (0/10) |

| Johnston’s Organ* | 100% (10/10) | 0% (0/10) |

| Ommatidia* | 100% (10/10) | 0% (0/10) |

| Fat Body* | 100% (10/10) | 80% (8/10) |

Tissues only observed in whole mosquito sections.

Figure 6.

Confocal micrographs of various tissues from Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes IT infected with GFP-expressing VEEV 3908 replicon particles. Transmitted image is overlayed with GFP fluorescent image. DAPI staining was added for images E-H. Whole mosquito sections (A, B, E-H); dissected tissue (C, D). A) Tracheoles associated with the posterior midgut. BB = brush border of the midgut epithelium. B) Epithelial cells of the intussuscepted foregut (IF). C) Circular muscles (CM) and nerves (N) of the posterior midgut. D) Ventral diverticulum muscles. E) Ganglionic connective tissue of the thoracic ganglia (TG). F) Longitudinal muscles (LM) and circular muscles (CM) of the posterior midgut. G) Circular muscles (CM) and tracheoles (Tr) of the hindgut. H) Johnston’s organ (JO) and ommatidia (Om). Red bars in lower corner = 20μm.

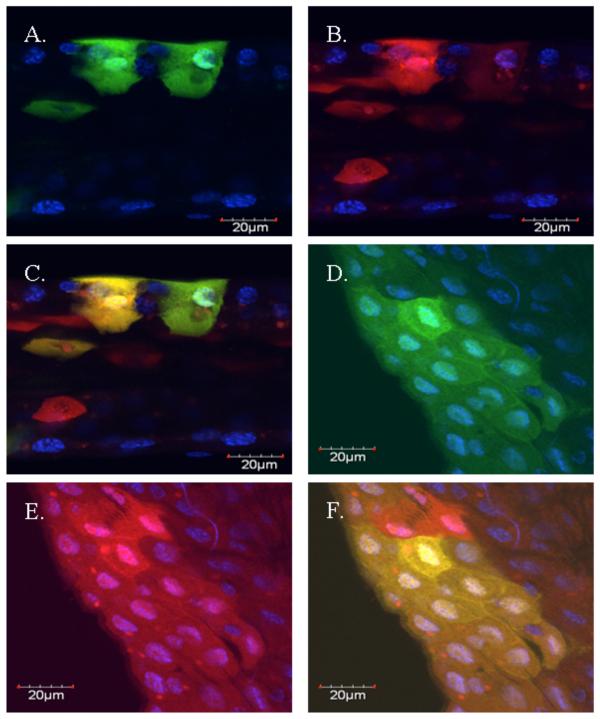

Susceptibility of Midgut Cell Populations to VEEV

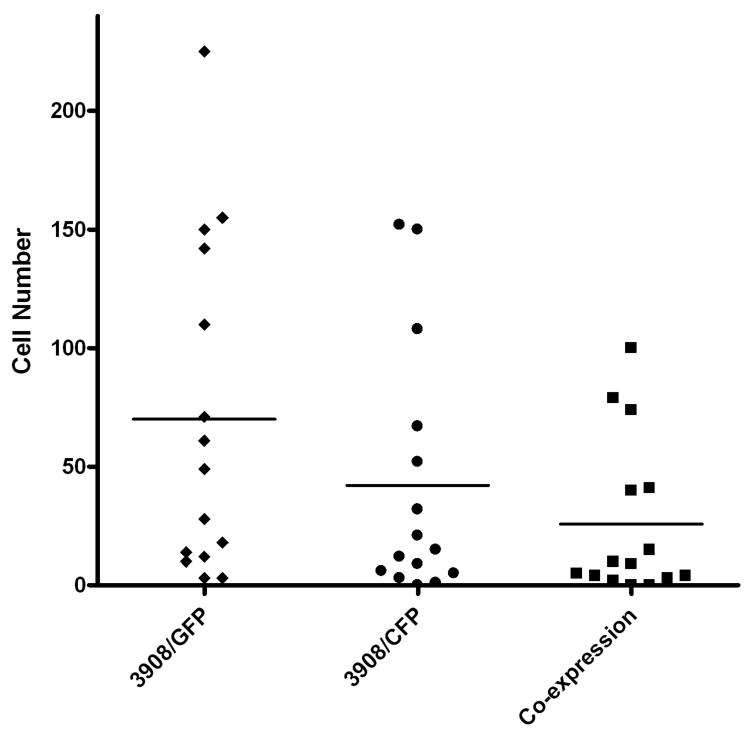

To determine if midgut cells are uniformly susceptible to VEEV infection, mosquitoes were fed an artificial bloodmeal with ca. equal amounts of VEEV strain 3908 replicon particles expressing either GFP or CFP. Midguts were dissected 24 h PI and the number of epithelial cells expressing either GFP, CFP, or both fluorescent proteins were counted. The re was a relatively high frequency of dually infected cells compared to singly infected cells (geometric mean expressing GFP=70, CFP=42, and co-expressing GFP and CFP=26; n=15; Fig. 7, Table 2). Assuming ca. 10,000 midgut epithelial cells (Houk et al., 1990) that are uniformly susceptible, the binomial distribution predicted a 22% probability of observing at least one dually infected cell per midgut based on single replicon particle infection data (Fig. 7) and the probability for observing just 5 dually infected cells per midgut was extremely low (0.001%). However, we observed a mean of 26 dually infected cells, which based on the probability distribution was significantly higher than the expected frequency. Extrapolation of these data yielded an estimate of only approximately 100 susceptible epithelial cells in the average Ae. taeniorhynchus midgut. Similar to the results described above, dual infection of midgut epithelial cells often occurred singly or in clusters, suggesting variability in susceptibility throughout the midgut (Fig. 8). A control experiment where the same bloodmeals were applied to monolayers of C6/36 cells, which are uniformly susceptible to VEEV replicon infection, yielded no more than the expected frequency of dual infections (Table 2). This result suggests that the high frequency of dual infections in mosquito midgut cells did not result from replicon particle aggregation or other artifacts of the artificial bloodmeals.

Figure 7.

The number of Ae. taeniorhynchus midgut epithelial cells expressing GFP, CFP, or co-expressing both fluorescent proteins following oral exposure to an equal mixture of VEEV strain 3908 replicon particles containing either GFP or CFP. Horizontal line represents the geometric mean.

Table 2.

Geometric mean number of cells expressing GFP, CFP, or co-expressing both fluorescent proteins in the mosquito midgut or in C6/36 cells following exposure to an equal mixture of VEEV strain 3908 replicon particles expressing either GFP or CFP

| Midgut | C6/36 Cells | |

|---|---|---|

| GFP | 70 | 1254 |

| CFP | 42 | 712 |

| Co-expression | 26 | 0 |

Figure 8.

Confocal micrographs of midguts from Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes after infection with VEEV 3908 replicon particles that express GFP or CFP. DAPI staining was added for all images. A) Singly infected mosquito midgut epithelial cells expressing GFP. B) Singly infected mosquito midgut epithelial cells expressing CFP. C) Overlayed image of A and B showing co-expression of both fluorescent proteins in a singly infected midgut epithelial cell. D) A cluster of infected mosquito midgut epithelial cells expressing GFP. E) A cluster of infected mosquito midgut epithelial cells expressing CFP. F) Overlayed image D and E showing co-expression of both fluorescent proteins in a cluster of infected midgut epithelial cells. Bar in lower corner = 20μm.

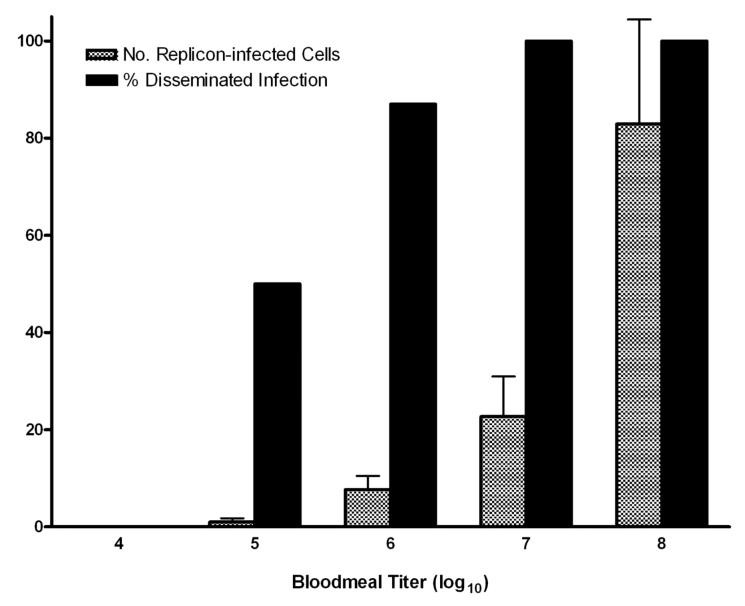

The number of susceptible midgut cells was also estimated using dose-response experiments with replicon particles and VEEV. Mosquitoes were orally exposed to increasing titers of infectious strain 3908 virus, as well as GFP-expressing strain 3908 replicon particles. The dissemination rate was determined for mosquitoes infected with VEEV by testing, 10 days after oral exposure, the legs and wings for virus content as a measure of disseminated infection. This was compared to the number of epithelial cells expressing GFP following oral infection with replicon particles. Mosquito disseminated infection rates reached 50% with a bloodmeal titer of ca. 5 log10 PFU/mL, and reached 100% by 7 log10 PFU/mL; the threshold titer (required to infect ca 1-5% of mosquitoes) was between 4 and 5 log10 PFU/mL (Fig. 9). At the same dose where the disseminated infection rate reached ca. 50%, the mean number of replicon-infected cells was 1; at the dose that saturated disseminated infection (7 log10 PFU/mL) the mean number of infected midgut cells was 23. These results suggest that a small number of initially infected midgut cells is sufficient to establish transmission-competent infection.

Figure 9.

Dose-response of VEEV strain 3908 infection of Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes with increasing titers of virus and replicon particles. Checkered bars represent the number of cells in the midgut expressing GFP, and solid bars represent the percentage of mosquitoes with a disseminated infection.

DISCUSSION

VEEV determinants of mosquito infection

Previous studies suggest that Ae. taeniorhynchus infection determinants lie within the VEEV E2 envelope glycoprotein (Brault et al., 2004; Brault et al., 2002) which forms a component of spikes on the alphavirion surface (Pletnev et al., 2001) that are involved in cell binding. We hypothesized that there are differential interactions of epidemic versus enzootic VEEV strains with receptors on midgut epithelial cells that limit infection in Ae. taeniorhynchus. Using [3H] uridine-labeled virus, we found that significantly more epidemic strain 3908 VEEV bound to Ae. taeniorhynchus midguts compared to endemic strain 68U201, and that binding increased for both strains up to 3 h after the bloodmeal. Additionally, both virus strains remained stable within Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes during the first 3 h after feeding. Autoradiography confirmed the differential binding results and showed epidemic VEEV binding along the luminal surface of the midgut with no detectable binding of enzootic VEEV. The autoradiography results also confirmed that virus binding occurred specifically on the luminal side of the midgut and not on the basal side that might reflect artificial, nonspecific binding during dissection or washing. Competitive binding studies are needed to determine if this binding is specific, as would be expected for a ligand-receptor interaction.

The primary sites of VEEV replication in orally infected Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes were determined using GFP-expressing replicon particles. Coincident with increased binding to midguts, more GFP-expressing cells were detected in mosquitoes fed epidemic strain 3908 compared to enzootic strain 68U201. Consistent with previous studies (Brault et al., 2002; Kramer and Scherer, 1976; Turell et al., 2003), our results suggest that epidemic subtype IC strains infect Ae. taeniorhynchus more efficiently than enzootic strains due to early interactions (probably with cellular receptors) on the apical surface of midgut epithelial cells. Infection with wild-type and chimeric replicon/helper combinations confirmed that the structural proteins are the main determinants of replicon particle infection in the midgut, and that once VEEV enters midgut epithelial cells, there were no major differences in viral replication that could be attributed to nonstructural proteins (Fig. 3).

Initial VEEV infection of the midgut

For epidemic VEEV strain 3908, both the number of midgut epithelial cells infected by replicon particles and the percentage of radiolabeled virus bound were variable among individual cohorts. This variability could reflect the use of F1 outbred mosquitoes, which are probably genetically less homogenous compared to colonized mosquitoes used in previous studies (Foy et al., 2004; Olson et al., 2000; Romoser et al., 2004; Scholle et al., 2004). The mean number of midgut cells infected with strain 3908 replicons from both experiments was 28. Other studies of mosquito infection by arboviruses report similar numbers of infected mosquito midgut cells, even with high titered bloodmeals. Scholle et al. (Scholle et al., 2004) observed that ≤15 midgut cells were infected when Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus mosquitoes ingested West Nile virus-like particles. Additionally, only a small number of infected cells was initially observed in the midgut of mosquitoes infected orally with Sindbis virus expressing GFP (Foy et al., 2004; Olson et al., 2000).

The midgut epithelium of mosquitoes is composed primarily of columnar epithelial cells whose function is secretory and absorptive during bloodmeal digestion (Hecker, 1977). Another midgut epithelium cell type is the endocrine cell, which is smaller than epithelial cells (Brown et al., 1985). In our study, GFP-expressing midgut cells occurred both singly and in clusters (Fig. 4). We also observed regions of clustered binding in the autoradiography results (Fig. 2). Therepeated occurrence of infected clusters suggested that certain cells are preferentially targeted by VEEV. Scholle et al. (2004) reported finding antigen positive clusters of cells in the midgut of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes infected with West Nile virus-like particles, possibly due to mitotic division. However, we did not observe mitotic figures, and because adult midgut cells are not believed to divide unless damaged (Day and Bennetts, 1953), we believe the clusters of GFP-expressing cells in the present study represent preferential infection. In addition, the high frequency of dual infection by GFP- and CFP-expressing replicon particles suggested that only a small fraction of epithelial cells is susceptible to oral infection at a given time.

The number of susceptible midgut cells was also estimated using dose-response experiments with replicon particles and infectious VEEV. Comparison of virus and replicon results suggest probabilistic events where virus concentrations that initially infect an average of ca. 23 midgut cells are needed to obtain 100% infection, and an average of ca. 1 infected cells comprise an ID50. These results suggest that a single infected epithelial cell may sometimes be sufficient to establish mosquito infection.

Infection of the hemocoel

Several reports of the rapid appearance of arboviruses in the hemocoel of mosquito vectors, prior to replication and dissemination within the midgut, suggest that midgut leaks occur following a bloodmeal (Boorman, 1960; Hardy et al., 1983; Miles et al., 1973; Weaver, 1986; Weaver and Scott, 1990; Weaver et al., 1991). We sectioned orally infected, whole mosquitoes to determine if primary sites of replication occur outside of the midgut, within the hemocoel. No GFP-expressing cells were detected in the hemocoel associated cells and tissues, suggesting that Ae. taeniorhynchus midgut leaks are rare. However, larger sample sizes are needed to determine if midgut leaks could result in rapid VEEV dissemination in this mosquito species.

GFP replicon particles were injected IT to test the hypothesis that midgut infection is the only barrier that determines the transmissibility of epidemic versus enzootic VEEV strains. GFP fluorescence was detected in 100% of mosquitoes injected IT with epidemic strain 3908 and in 80% of mosquitoes infected with enzootic strain 68U201. Our results agree with those of Romoser et al. (Romoser et al., 2004), except that we did not find infected tracheal cells associated with the salivary glands. This difference may be due to the use of different strains of VEEV and Ae. taeniorhynchus. However, in agreement with our results, Romoser et al. (Romoser et al., 2004) also reported consistent infection of tracheal cells in the alimentary tract, suggesting these cells may serve as conduits for VEEV dissemination from the midgut. Scholle et al. also reported consistent infection of tracheal cells associated with the midgut of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes infected with West Nile virus-like particles (Scholle et al., 2004). Our results add to growing evidence of the susceptibility of tracheal cells to oral infection by arboviruses, suggesting an important role in viral dissemination from the midgut.

More GFP expressing cells were detected in mosquitoes injected IT with the strain 3908 replicons when compared to the strain 68U201 replicons. However, when fully infectious VEEV is injected IT, strain 68U201 replicates to only slightly lower titers when compared to strain 3908 (DRS, unpublished data). We did not detect infection of salivary glands with the IT inoculated replicon particles, suggesting the need for amplification in the hemocoel prior to salivary gland infection. Additional studies with more quantitative methods for assessing differential patterns of viral replication are needed in the future.

VEEV population bottlenecks

Even with the high titer bloodmeals used in our studies, very few (often less than 10) cells in the midgut of an important VEEV vector became infected. Because the peak titers in infected equids or rodents rarely approach those used in our studies, natural mosquito infection may often involve even fewer midgut cells. This suggests that many VEEV transmission events involve genetic bottlenecks at the vector infection stage. In addition, transmission of VEEV in mosquito saliva frequently involves only a few PFU (Smith et al., 2006), which could represent another bottleneck during natural circulation. However, VEEV remains highly stable genetically and phenotypically even during epidemics involving large amounts of virus replication and circulation (Weaver et al., 2004). Understanding how these RNA viruses avoid fitness declines due to Muller’s ratchet, which has been demonstrated for arboviruses such as vesicular stomatitis virus (Duarte et al., 1992) and the alphavirus Eastern equine encephalitis virus (Weaver et al., 1999), represents an important topic for further research. One possibility is that the frequent dual infections of midgut cells we observed using mixtures of GFP- and CFP-expressing replicons could enhance the chances of recombination, which is efficient at repairing deleterious mutations that accompany bottlenecks. Although alphaviruses exhibit superinfection exclusion within a few hours of infection, midgut epithelial cell infections probably occur during this time window because the peritrophic matrix forms quickly to limit virus contact with the epithelium (Weaver, 1997).

In summary, epidemic VEEV strain 3908 bound to and infected significantly more midgut epithelial cells in Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes compared to enzootic strain 68U201, and it appeared that certain midgut cells were preferentially infected. When the midgut was bypassed and replicon particles were injected directly into the hemocoel, most of the same tissues were susceptible to infection with both epidemic and enzootic strains. Interactions of VEEV with midgut epithelial cells (possibly with their receptors) probably determine their ability to infect this important vector. Future studies with additional epidemic (subtype IAB) and enzootic (subtype ID) VEEV strains are needed to determine if comparable virus-vector interactions mediate the emergence of all epidemic VEEV strains via changes in epidemic vector infectivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses

VEEV was rescued from infectious cDNA clones derived from either epidemic strain 3908 (subtype IC) or enzootic strain 68U201 (subtype IE). Epidemic strain 3908 was derived from a 1995 human isolate from Zulia State, Venezuela during a major outbreak (Weaver et al., 1996), and enzootic strain 68U201 was isolated from a sylvatic Guatemalan focus in 1968 (Scherer et al., 1970). The overall amino acid sequence divergence between the subtype IC and IE strains strain is 11% (Brault et al., 2002). Strain 3908 was passaged once in C6/36 mosquito cells before undergoing RNA extraction and infectious cDNA clone production (Brault et al., 2002), and strain 68U201 was passaged once in suckling mice and twice in BHK-21 cells before cloning (Powers et al., 2000). To minimize confounding mutations that occur when VEEV is passaged in cell culture (Bernard et al., 2000), virus recovered from BHK-21 cells electroporated with transcribed RNA was used for all experiments without further passage.

Mosquitoes

First generation Ae. taeniorhynchus mosquitoes were reared from eggs laid by wild-caught females from Galveston, TX (29°13.128′ N; 94°56.063′ W). Mosquitoes were reared at 27°C with 80% relative humidity using a light:dark cycle of 12:12 h. Adult female mosquitoes were either presented with an infectious artificial bloodmeal or inoculated IT 6-8 days after emergence, and incubated at 27°C with 10% sucrose provided ad libitum.

Radiolabeled Virus

VEEV strains 3908 and 68U201 were radiolabeled with [3H] uridine in BHK-21 cells. Cell monolayers were infected at a multiplicity of ca. 10 PFU/cell and [3H] uridine (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) was added to the culture medium at a concentration of 12.5 μCi/ml. At 24 hours post-infection (PI), the culture medium was harvested, clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 x g for 10 minutes, and virus was precipitated at 4°C overnight in polyethylene glycol 8000 and sodium chloride at final concentrations of 7% and 2.3% (W/V), respectively. Following centrifugation at 6,000 x g for 30 minutes, the pellet was resuspended in 1X TEN [0.05M Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 0.1M NaCl, 0.001M EDTA] and purified on continuous 20-70% (W/V) sucrose gradients in TEN buffer at 270,000 x g for one h. Virus bands were harvested and pelleted at 270,000 x g for 3 h using a 30% sucrose/TEN cushion. Virus pellets were resuspended in Eagles minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and stored at -80°C.

Mosquito Infections with Radiolabeled Virus

Mosquitoes received an artificial bloodmeal containing 20% (V/V) FBS, 10% (V/V) MEM containing labeled virus, and 70% (V/V) defibrinated sheep red blood cells. Mosquitoes ingested an average of 8.7 log10 plaque forming units (PFU) that contained 50,250 counts per minute (CPM) of VEEV strain 3908 or 8.4 log10 PFU that contained 27,150 CPM of strain 68U201. Viral titers were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells. Similar virus titers (rather than CPM) were used for each strain to ensure that putative receptor-particle interactions were equivalent stoichiometrically. At 30 minutes, 90 minutes, and 3 h after feeding, mosquitoes were anesthetized by chilling and their midguts were dissected and cut in half longitudinally. Later time points were not measured because peritrophic matrix formation occurs within a few hours of bleed feeding and presumably precludes virus-epithelial cell interactions. Residual blood was removed by washing 3 times in Aedes physiological saline (Hayes, 1953). Radiolabeled virus was dissociated from the midgut in 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 0.5% Igepal (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in Aedes saline, and midgut and wash samples were counted for 10 minutes using a Tri-Carb 2800TR liquid scintillation analyzer (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA). The percentage of virus bound was determined by dividing the counts dissociated from the midgut by the combined counts of the 3 separate washes.

Additional cohorts of mosquito midguts were analyzed by autoradiography to ensure that scintillation counts reflected radiolabeled virus bound to the luminal side of midgut cells, and not artificial binding to the basal side during dissection and washing. Midguts were fixed in 10% formol saline and embedded in LR white resin (SPI supplies, West Chester, PA). One μm sections were cut and dried onto microscope slides, which were coated with liquid autoradiography emulsion (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) and exposed at 4°C for 30 days. The slides were then developed, fixed, and analyzed by brightfield and phase contrast microscopy.

The stability within the mosquito midgut of the 2 VEEV strains was compared by infecting cohorts with bloodmeals containing 7.5 log10 PFU/mL of strain 3908 or 68U201. At 30 minutes, 90 minutes, and 3 h after feeding, 10-13 mosquitoes were collected, triturated in 300 μL of 20% MEM using a Mixer Mill 300 (Retsch, Newton, PA), and titrated on Vero cells.

Replicon Particles

Alphavirus genome replication requires only the nonstructural proteins and cis-acting sequences, allowing for the generation of defective replicating genomes (replicons) by deletion of the structural protein genes (Bredenbeek et al., 1993; Geigenmuller-Gnirke et al., 1991; Pushko et al., 1997). To visualize primary cells in which VEEV initially replicates, virus-like particles containing replicons were created by replacing the structural genes within the cDNA clones of strains 3908 and 68U201 with the GFP gene or the CFP gene. The structural proteins were expressed from a separate, transcribed cDNA (helper) clone. Transcribed RNAs (4μg) from replicon and helper clones were co-electroporated into BHK-21 cells for replication and packaging of the replicon into virus-like particles.

Mosquito Infections with Replicon Particles

Mosquitoes were infected either orally or IT with either 3908 GFP- or 68U201 GFP-expressing replicon particles. Additional cohorts of mosquitoes received replicon particles containing strain 3908 structural proteins and strain 68U201 nonstructural protein genes or vice versa. Mosquitoes were allowed to feed for 1 h from an artificial bloodmeal (described above) containing replicon particles in MEM. Bloodmeal titers were 8 log10 focus forming units (FFU)/ml for both fluorescent-labeled VEEV strains. An additional cohort of mosquitoes received a bloodmeal of 9 log10 FFU/ml of VEEV strain 68U201 particles to increase chances for midgut infection. Additional cohorts were infected IT using a glass capillary pipette with approximately 1μL containing 4 log10 FFU of VEEV 3908 or 68U201 replicon particles. Twenty-four h PI, midguts and salivary glands (IT infections only), were dissected, washed once in Aedes saline, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Tissues were mounted on microscope slides and assessed for GFP or CFP expression using an Olympus FluoView-1000 scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY). An additional cohort of replicon-infected mosquitoes was fixed with 4% PFA by IT injection, embedded and frozen in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), and cryosectioned into 6 μM sagittal sections prior to mounting on microscope slides with ProLong Gold antifade reagent 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Sectioned mosquitoes were analyzed for GFP or CFP expression by confocal microscopy.

To determine the susceptibility of midgut cell populations, mosquitoes were allowed to feed for 1 hour from an artificial bloodmeal containing equal amounts of replicon particles expressing GFP or CFP. Twenty-four h PI, midguts were dissected and mounted on microscope slides as described above. Using a confocal microscope, the number of GFP- and CFP-expressing midgut epithelial cells was counted. Generally, GFP levels in infected cells were well above background levels of sham-infected mosquitoes, so there was no difficulty in determining numbers of infected cells.

A dose-response experiment was also used to estimate the number of susceptible midgut cells. Mosquitoes were allowed to feed for 1 h from an artificial bloodmeal containing either VEEV strain 3908 or GFP-expressing strain 3908 replicon particles at increasing titers (4 log10-8 log10 PFU or FFU/mL, respectively). To assess the viral dissemination rate, the legs and wings of mosquitoes infected with VEEV strain 3908 were collected 10 days PI, triturated in 300 μL of 20% MEM, and 75 μL of the supernatant was added to Vero cell monolayers to observe for cytopathic effects (CPE). A disseminated infection is defined as the percentage of all orally exposed mosquitoes that contain virus in their legs. For mosquitoes infected with GFP-expressing strain 3908 replicon particles, the midguts were dissected 24 h PI, washed once in Aedes saline, fixed in 4% PFA, then mounted and observed by confocal microscope to count the number of GFP-expressing cells.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The fraction of radiolabeled VEEV strains 3908 or 68U201 that bound to mosquito midguts, the number of cells expressing GFP in the midgut of mosquitoes infected with replicon particles, the number of midgut cells expressing GFP in mosquitoes infected with replicon particles containing various homologous and heterologous replicon/helper combinations, and the number of C6/36 cells expressing GFP vs. CFP were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t-tests. The proportion of GFP-expressing cells in mosquitoes infected with VEEV strains 3908 or 68U201 replicon particles were analyzed by a Fisher’s exact test. The number of midgut cells and C6/36 mosquito cells expressing GFP, CFP, or both fluorescent proteins was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Differences were considered significant when p< 0.05. The binomial probability distribution was used to determine the probability of observing dually infected cells.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jing Huang for rearing mosquitoes, Nikolaos Vasilakis, Vsevolod Popov, Julie Wen, and Michael Holbrook for technical advice. We also thank Lark Coffey for kindly reviewing this manuscript, and Michael Turell for help with statistics. DRS was supported by CDC training grant T01/CCT622892 and a fellowship from the Keck Center for Virus Imaging. This research was supported by NIH grants AI418807 and AI57156.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bernard KA, Klimstra WB, Johnston RE. Mutations in the E2 glycoprotein of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus confer heparan sulfate interaction, low morbidity, and rapid clearance from blood of mice. Virology. 2000;276(1):93–103. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boorman J. Observations on the amount of virus present in the haemolymph of Aedes aegypti infected with Uganda S, yellow fever and Semliki Forest viruses. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1960;54:362–5. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(60)90117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault AC, Powers AM, Ortiz D, Estrada-Franco JG, Navarro-Lopez R, Weaver SC. Venezuelan equine encephalitis emergence: Enhanced vector infection from a single amino acid substitution in the envelope glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101(31):11344–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402905101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault AC, Powers AM, Weaver SC. Vector infection determinants of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus reside within the E2 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 2002;76(12):6387–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.6387-6392.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredenbeek PJ, Frolov I, Rice CM, Schlesinger S. Sindbis virus expression vectors: packaging of RNA replicons by using defective helper RNAs. J Virol. 1993;67(11):6439–46. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6439-6446.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, Raikhel AS, Lea AO. Ultrastructure of midgut endocrine cells in the adult mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Tissue Cell. 1985;17(5):709–21. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(85)90006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day MF, Bennetts MJ. Healing of gut wounds in the mosquito Aedes aegypti (L.) and the leafhopper Orosius argentatus (EV.) Aust J Biol Sci. 1953;6(4):580–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte E, Clarke D, Moya A, Domingo E, Holland J. Rapid fitness losses in mammalian RNA virus clones due to Muller’s ratchet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(13):6015–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy BD, Myles KM, Pierro DJ, Sanchez-Vargas I, Uhlirova M, Jindra M, Beaty BJ, Olson KE. Development of a new Sindbis virus transducing system and its characterization in three Culicine mosquitoes and two Lepidopteran species. Insect Mol Biol. 2004;13(1):89–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2004.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigenmuller-Gnirke U, Weiss B, Wright R, Schlesinger S. Complementation between Sindbis viral RNAs produces infectious particles with a bipartite genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(8):3253–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JL, Houk EJ, Kramer LD, Reeves WC. Intrinsic factors affecting vector competence of mosquitoes for arboviruses. Annu Rev Entomol. 1983;28:229–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.28.010183.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes RO. Determination of a physiological saline solution for Aedes aegypti (L.) Journal of Econ Entomol. 1953;(46):624–627. [Google Scholar]

- Hecker H. Structure and function of midgut epithelial cells in culicidae mosquitoes (insecta, diptera) Cell Tissue Res. 1977;184(3):321–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00219894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houk EJ, Arcus YM, Hardy JL, Kramer LD. Binding of western equine encephalomyelitis virus to brush border fragments isolated from mesenteronal epithelial cells of mosquitoes. Virus Res. 1990;17(2):105–118. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(90)90072-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer LD, Scherer WF. Vector competence of mosquitoes as a marker to distinguish Central American and Mexican epizootic from enzootic strains of Venezuelan encephalitis virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1976;25(2):336–46. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1976.25.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig GV, Christensen BM, Yuill TM, Schultz KT. Enzyme processing of La Crosse virus glycoprotein G1: a bunyavirus-vector infection model. Virology. 1989;171(1):108–13. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90516-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig GV, Israel BA, Christensen BM, Yuill TM, Schultz KT. Role of La Crosse virus glycoproteins in attachment of virus to host cells. Virology. 1991;181(2):564–71. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90889-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens PP, Burroughs JN, Walton A, Wellby MP, Fu H, O’Hara RS, Brookes SM, Mellor PS. Enhanced infectivity of modified bluetongue virus particles for two insect cell lines and for two Culicoides vector species. Virology. 1996;217(2):582–93. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles JA, Pillai JS, Maguire T. Multiplication of Whataroa virus in mosquitoes. J Med Entomol. 1973;10(2):176–85. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/10.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Cruz A, Gupta L, Richardson J, Bennett K, Black W. t., Barillas-Mury C. Effect of mosquito midgut trypsin activity on dengue-2 virus infection and dissemination in Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72(5):631–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourya DT, Ranadive SN, Gokhale MD, Barde PV, Padbidri VS, Banerjee K. Putative chikungunya virus-specific receptor proteins on the midgut brush border membrane of Aedes aegypti mosquito. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 1998;107:10–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles KM, Pierro DJ, Olson KE. Deletions in the putative cell receptor-binding domain of Sindbis virus strain MRE16 E2 glycoprotein reduce midgut infectivity in Aedes aegypti. J Virol. 2003;77(16):8872–81. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8872-8881.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KE, Myles KM, Seabaugh RC, Higgs S, Carlson JO, Beaty BJ. Development of a Sindbis virus expression system that efficiently expresses green fluorescent protein in midguts of Aedes aegypti following per os infection. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9(1):57–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierro DJ, Myles KM, Foy BD, Beaty BJ, Olson KE. Development of an orally infectious Sindbis virus transducing system that efficiently disseminates and expresses green fluorescent protein in Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol Biol. 2003;12(2):107–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletnev SV, Zhang W, Mukhopadhyay S, Fisher BR, Hernandez R, Brown DT, Baker TS, Rossmann MG, Kuhn RJ. Locations of carbohydrate sites on alphavirus glycoproteins show that E1 forms an icosahedral scaffold. Cell. 2001;105(1):127–36. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00302-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers AM, Brault AC, Kinney RM, Weaver SC. The use of chimeric Venezuelan equine encephalitis viruses as an approach for the molecular identification of natural virulence determinants. J Virol. 2000;74(9):4258–63. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4258-4263.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushko P, Parker M, Ludwig GV, Davis NL, Johnston RE, Smith JF. Replicon-helper systems from attenuated Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus: expression of heterologous genes in vitro and immunization against heterologous pathogens in vivo. Virology. 1997;239(2):389–401. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas F, Diaz LA, Cardenas VM, Daza E, Bruzon L, Alcala A, De la Hoz O, Caceres FM, Aristizabal G, Martinez JW, Revelo D, De la Hoz F, Boshell J, Camacho T, Calderon L, Olano VA, Villarreal LI, Roselli D, Alvarez G, Ludwig G, Tsai T. Epidemic Venezuelan equine encephalitis in La Guajira, Colombia, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(4):828–32. doi: 10.1086/513978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romoser WS, Wasieloski LP, Jr., Pushko P, Kondig JP, Lerdthusnee K, Neira M, Ludwig GV. Evidence for arbovirus dissemination conduits from the mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) midgut. J Med Entomol. 2004;41(3):467–75. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.3.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer WF, Dickerman RW, Ordonez JV. Discovery and geographic distribution of Venezuelan encephalitis virus in Guatemala, Honduras, and British Honduras during 1965-68, and its possible movement to Central America and Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970;19(4):703–11. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholle F, Girard YA, Zhao Q, Higgs S, Mason PW. trans-Packaged West Nile virus-like particles: infectious properties in vitro and in infected mosquito vectors. J Virol. 2004;78(21):11605–14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11605-11614.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DR, Aguilar PV, Coffey LL, Gromowski GD, Wang E, Weaver SC. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus transmission and effect on pathogenesis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(8):1190–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1208.050841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turell MJ, O’Guinn ML, Navarro R, Romero G, Estrada-Franco JG. Vector competence of Mexican and Honduran mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) for enzootic (IE) and epizootic (IC) strains of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus. J Med Entomol. 2003;40(3):306–10. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-40.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC. Electron microscopic analysis of infection patterns for Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus in the vector mosquito, Culex (Melanoconion) taeniopus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;35(3):624–31. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC. Vector Biology in Viral Pathogenesis. In: Nathanson N, editor. Viral Pathogenesis. Lippincott-Raven; New York: 1997. pp. 329–352. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC, Brault AC, Kang W, Holland JJ. Genetic and fitness changes accompanying adaptation of an arbovirus to vertebrate and invertebrate cells. J Virol. 1999;73(5):4316–26. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4316-4326.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC, Ferro C, Barrera R, Boshell J, Navarro JC. Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2004;49:141–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC, Salas R, Rico-Hesse R, Ludwig GV, Oberste MS, Boshell J, Tesh RB, VEE Study Group Re-emergence of epidemic Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis in South America. Lancet. 1996;348(9025):436–40. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC, Scott TW. Ultrastructural changes in the abdominal midgut of the mosquito, Culiseta melanura, during the gonotrophic cycle. Tissue Cell. 1990;22(6):895–909. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(90)90051-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC, Scott TW, Lorenz LH, Repik PM. Detection of eastern equine encephalomyelitis virus deposition in Culiseta melanura following ingestion of radiolabeled virus in blood meals. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;44(3):250–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.44.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward TM, Miller BR, Beaty BJ, Trent DW, Roehrig JT. A single amino acid change in the E2 glycoprotein of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus affects replication and dissemination in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. J Gen Virol. 1991;72(Pt 10):2431–5. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-10-2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Wilson W, Mecham J, Murphy K, Zhou EM, Tabachnick W. VP7: an attachment protein of bluetongue virus for cellular receptors in Culicoides variipennis. J Gen Virol. 1997;78(Pt 7):1617–23. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-7-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]