Abstract

Immunization with portions of a murine antibody to DNA induced Ig peptide-reactive peripheral CD8+ inhibitory T (Ti) cells in non-autoimmune (BALB/c × NZW) F1 (CWF1) mice. Those Ti suppressed in vitro production of IgG anti-DNA by lymphocytes from MHC-matched, lupus-prone (NZB × NZW) F1 (BWF1) mice, primarily via secretion of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). However, splenic CD8+ cells from immunized BWF1 mice failed to suppress anti-DNA. Therefore, BWF1 mice were studied for defects in peripheral CD8+ T cells. The potential to suppress autoimmunity mediated by activated CD4+ helper T and B cells in BWF1 mice was assessed. As BWF1 mice aged, peripheral CD8+ T cells expanded little; fewer than 10% displayed surface markers of activation and memory. In contrast, quantities of splenic CD4+ T and B cells increased; high proportions displayed activation/memory markers. In old compared to young BWF1 mice, splenic cell secretion of two cytokines required for generation of CD8+ T effectors, IL-2 and TGF-β, was decreased. Immunizing BWF1 mice activated peptide-reactive CD8+ T cells, but their number was decreased compared to young BWF1 or old normal mice. While peptide-reactive splenic CD8+ T cells from immunized BWF1 mice did not survive in short-term cultures, similar CD8+ T cell lines from immunized CWF1 mice expanded and on transfer into BWF1 mice delayed autoimmunity and prolonged survival. Therefore, CD8+ T cells in old BWF1 mice are impaired in expansion, acquisition of memory, secretion of cytokine, and suppression of autoimmunity. Understanding these defects might identify targets for therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus.

Keywords: Inhibitory CD8+ T cells, Lupus

1 Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is characterized by poorly controlled production of autoantibodies [1]. In human and murine lupus, emergence of autoreactive T helper (Th) cells that promote autoantibody production [2, 3] may be accompanied by loss or defective function of regulatory or suppressor/inhibitory T cells (Ti), some of which are CD8+ [4–6]. To understand the role of Ti in SLE, we used a model in which Ti suppress Th help for B cells producing IgG anti-DNA Ab in (NZB × NZW) F1 (BWF1) mice [3, 4, 6]. Th cells recognized peptides derived from the VH of BWF1 anti-DNA mAb. Similar Th epitopes occur in the VH of other murine and human antibodies to DNA [7–11]. Previous data have indicated that MHC class I-binding T cell epitopes within these peptides can activate suppressive CD8+ cells that inhibit autoantibody production [4, 12].

We have recently shown that non-autoimmune mice with MHC class I and II molecules [(BALB/c × NZW) F1 (CWF1) females, H-2d/z] matched to those of BWF1 mice (H-2d/z) do not spontaneously develop Th cells promoting autoantibody production [6]. After immunization with anti-DNA mAb or peptides from it, CWF1 mice develop Th cells that promote anti-DNA production and nephritis. Autoimmune disease in CWF1 mice is self-limiting. During recovery, they developed CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that inhibited in vitro autoantibody production. However, similar peptide-activated CD8+ T cells generated by identical immunizations in lupus-prone BWF1 mice failed to suppress anti-DNA production in vitro.

Here, we identify differences between CWF1 and BWF1 peripheral CD8+ T cells, and show that the vigorous CD4+ T cell-supported autoantibody production in BWF1 mice can be controlled in vivo by transfer of antigen-stimulated CD8+ T cells from normal mice, but not from BWF1 mice.

2 Results

2.1 Peptide-specific CD8+ T cells that inhibit/suppress autoantibody production in vitro can be induced by immunization in non-autoimmune mice but not in lupus mice

Immunizations of non-autoimmune CWF1 mice with whole anti-DNA mAb A6.1, its γ chain, or peptides from its VH caused breakdown in B cell tolerance and expansion of anti-VH Th cells [6]. These mice developed high titers of anti-DNA and ≥2+ proteinuria, which disappeared over time. Recovery was concurrent with emergence of CD8+ Ti cells that suppressed anti-DNA production when co-cultured with syngeneic B plus CD4+ T cells.

To further examine the contribution of CD8+ T cells reactive with an immunodominant peptide A6H31–45 from the immunizing anti-DNA Ab, we established additional T cell lines from CWF1 mice that were immunized five times with A6H31–45. The peptide A6H31–45 contains both MHC class II and I T cell epitopes [4, 12]. Half of CD8+ T cell lines from hyperimmunized CWF1 mice decreased anti-DNA production from BWF1 B plus T cells by 25–66% [6]. To address peptide specificity of several CD8+ Ti cell lines, they were cultured with BWF1 T plus B cells in the presence of T cell determinants (A6.1 31–45 or A6.1 41–54) or control (HYHEL 31–45 or HEL 106) peptides. HYHEL 31–45 is derived from the same VH region as A6H31–45, in another J558-encoded non-DNA-binding mAb, HYHEL.

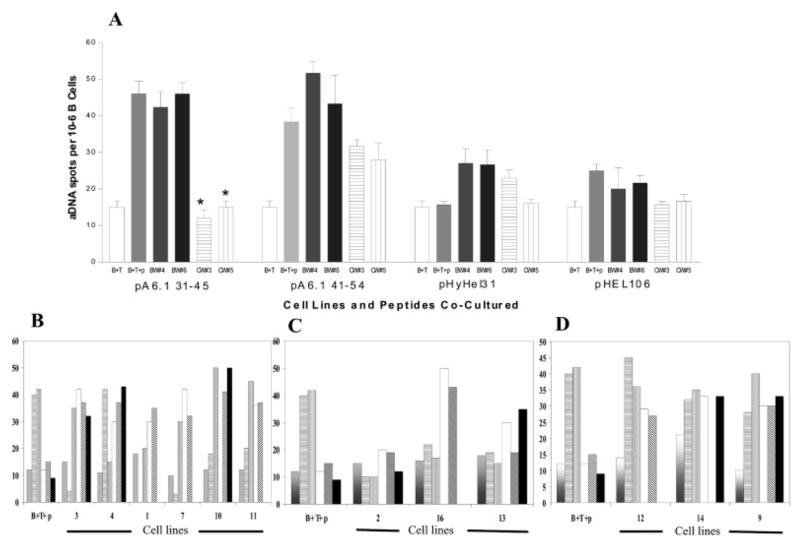

Fig. 1A shows in vitro suppression of anti-DNA production by two CWF1 CD8+ Ti cell lines co-cultured with BWF1 B cells. Two CD8+ T cell lines from BWF1 are also shown; they did not suppress anti-DNA production. While most Ti lines suppressed anti-DNA Ab-forming cells (AFC) only in the presence of A6H31–45 (Fig. 1A, B), three lines inhibited anti-DNA Ab production with or without several peptides (Fig. 1C). Some CWF1 CD8+ T cell lines were not suppressive (Fig. 1D), as well as control (short-term) CD8+ T cell lines derived from CWF1 mice immunized with HYHEL that did not suppress anti-DNA production (not shown). All of the CWF1 CD8+ lines with Ti activity secreted TGF-β1; their suppression of anti-DNA could be abrogated by blocking TGF-β [6].

Fig. 1.

Examples of CD8+ CWF1 T cell lines that were peptide-specific, nonspecific, and non-stimulatory. Each cell line was tested at least two times, each experiment in triplicate, with the two most suppression-stimulating peptides (A6.31 and A6.41) and with at least two non-stimulatory peptides (A6.114, HYHEL.31, or HELp106). CWF1 females were immunized with either A6.31 or A6.41, boosted once, and CD8+ T cells were isolated from spleens 10–14 days later. Lines were developed by repeated stimulation with Con A supernatant, BWF1 APC, and immunizing peptides. Each of these lines was developed after at least two 14-day cycles of stimulation (none of the CD8+ BWF1 lines survived beyond that time) and harvested 12 days after rest from stimulation. Lines (105 cells) were co-cultured with BWF1 B cells (1 × 105) and T cells (1 × 106) with or without 20 μM of peptides. In all figures, a result of zero means that peptide was not tested. (A) Examples of two BWF1 CD8+ T cell lines (not suppressive) and two CD8+ CWF1 T cell lines (suppressive) tested for their abilities, when activated by their immunizing peptide (A6.31), to suppress the numbers of BWF1 B cells producing IgG anti-dsDNA (on the x axis). Data are expressed as mean AFC per 105 B cells. Vertical lines indicate SEM. (B) Example of six additional cell lines that were suppressive and peptide-specific (white: no peptide added; horizontal lines: peptide A6.1 31–45 added; vertical lines: peptide A6.1 41–54 added; diagonal lines: peptide A6.1 114 added; gray: peptide HYHEL.31 added; black: peptide HEL106 added). * Significantly different from B+T+peptide controls in far left column, p<0.05 by Mann-Whitney U-test. Note that lines 3, 7, 10, and 11 are activated specifically by A6.31 and lines 4 and 1 are activated specifically by A6.41. (C) Examples of three lines that are suppressive, but not strictly peptide-specific. One line is activated to suppress by every peptide tested; it is autoreactive. (D) Examples of three cell lines that were not suppressive.

To exclude the possibility that the presence of minor allogeneic differences between CWF1 and BWF1 mice confounds these studies, we performed mixed lymphocyte reactions. Proliferation of BWF1 or CWF1 splenocytes in response to irradiated splenocytes from the opposite strain (mean cpm 2,100–2,500 ± 190–210 SEM) was not significantly elevated above background (1,400±200). In contrast, proliferation of BWF1 or CWF1 splenocytes to C57BL/6J irradiated cells (mean cpm 17,000±2,100 for BWF1 and 15,500±1,950 for CWF1) was brisk and highly significant (p<0.001 by ANOVA) compared to proliferation in unstimulated cultures.

Since CD8+ T cells that inhibit in vitro autoantibody production from autoreactive B cells can be induced in normal CWF1 mice, but not in lupus-prone BWF1 mice, it is possible that such Ti are absent, ineffective, inadequately generated, or prematurely lost in aging BWF1 mice. The following experiments were conducted to address these questions.

2.2 CD8+ cells in diseased BWF1 mice increase in numbers significantly less than CD4+ T and B cells

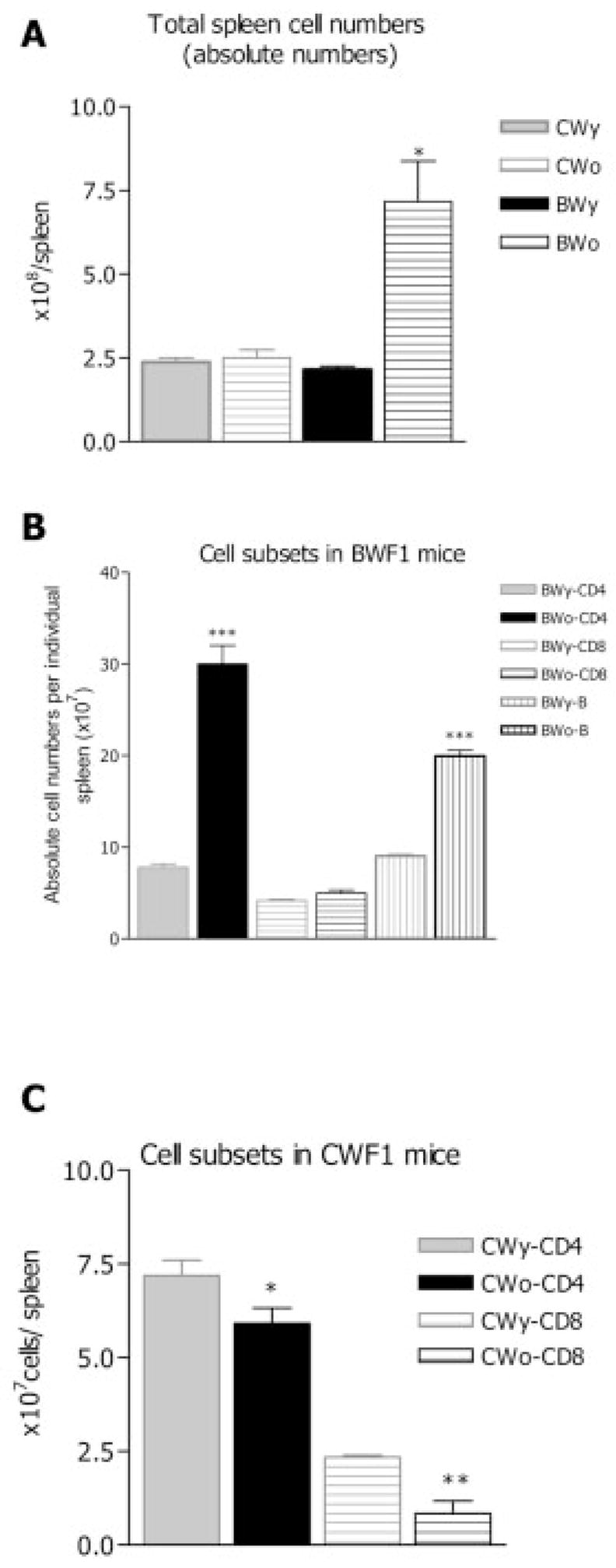

Total numbers of splenocytes, CD8+, CD4+, and B cells were enumerated in individual BWF1 and CWF1 mice at different ages. Groups contained 6–12 mice. Old BWF1 females (35–38 weeks old with ≥2+ proteinuria) showed statistically significant increases in total spleen cells, CD4+ T cells, and B cells compared to young (12-week-old) BWF1 mice (Fig. 2A, B). In contrast, CD8+ T cell numbers did not increase significantly in nephritic BWF1 compared to young mice. In CWF1 mice (age-matched with BWF1), significant reduction in numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells occurred with age (Fig. 2C). Similar decreases in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers in old compared to young mice were seen in another non-autoimmune mouse strain, BALB/c (data not shown). Therefore, as BWF1 mice age, CD4+ and B cells expand to large numbers; CD8+ T cell numbers are maintained but do not expand to the same extent.

Fig. 2.

Numbers of lymphocytes (total spleen mononuclear cells, CD4+, B, and CD8+) change over time in CWF1 and BWF1 mice. y: young mice aged 11–12 weeks; o: old mice aged 35–38 weeks (all BWF1 with proteinuria ≥2+). Spleen cells pooled from three to five mice in each group were analyzed by FACS after appropriate surface staining. Means ± SEM are shown for four experiments for each group. (A) In old BWF1 mice (BWo) compared to young (BWy) total mononuclear spleen cell numbers increased significantly (*p<0.01 by ANOVA). (B) In old BWF1, numbers of CD4+ T cells increased significantly (***p<0.001), as did B cells (***p<0.001) but not CD8+ T cells, as compared to 12-week-old mice. (C) As CWF1 mice aged, total numbers of CD4+ T cells declined significantly (*p=0.05), as did CD8+ T cells (**p<0.01), as compared to young CWF1.

To examine the possibility that anti-lymphocyte Ab influenced BWF1 CD8+ T cells, splenocytes from BWF1 and control mice obtained fresh ex vivo or cultured for 24 h were stained with anti-mouse IgM and anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2-biotin. Staining for IgM was trivial in all groups (2–5% of cells). Higher proportions of fresh CD4+ and CD8+ cells were coated with IgG in old BWF1 mice than in young ones (for CD4+: 23%; for CD8+: 10%). The IgG on BWF1 T cells was probably of low affinity since it was shed from the cell surface after 24 h in culture. Since all functional assays for Th or Ti were performed in cultures that were incubated overnight or longer, it is unlikely that the presence of these surface Ab accounted for the defects observed in the BWF1 CD8 cells.

2.3 IL-2 and TGF-β1 levels are lower in the culture supernatants of splenic cells in diseased BWF1 mice

Adequate quantities of IL-2 and TGF-β in the microenvironment are among the minimal requirements for generation of functional peripheral CD8+ Ti cells [13–15]. We measured IL-2 production in the supernatants of splenocytes from old and young CWF1 and BWF1 mice, activated by addition of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 and cultured for 48 h. IL-2 secretion was significantly lower in old BWF1 mice compared to old CWF1 mice (mean pg/ml 2,100±180 in old BWF1 vs. 9,900±120 in old CWF1; p<0.004 by χ2 analysis). TGF-β1 in supernatants of old and young BWF1 CD8+ T cells was measured as described in Sect. 4. Constitutive secretion of that cytokine was significantly lower in supernatants from cells of old BWF1 mice (mean pg/ml 1,200±125 SD in young vs. 425±150 in old; p<0.009 by Mann-Whitney U-test). Thus, we concluded that old BWF1 T cells produce less IL-2 than young cells, and that as BWF1 mice age, CD8+ cells have less constitutive production of TGF-β1, suggesting that some of the major cytokines required for generation of effector CD8+ Ti are less available. Defective production of TGF-β1 may be particularly important, since all the effective CD8+ Ti from CWF1 mice spontaneously secreted this cytokine, and their suppressive effect depended upon it [6].

2.4 Smaller proportions of CD8 than of CD4 T cells display surface markers of activation and memory phenotypes in diseased BWF1 mice

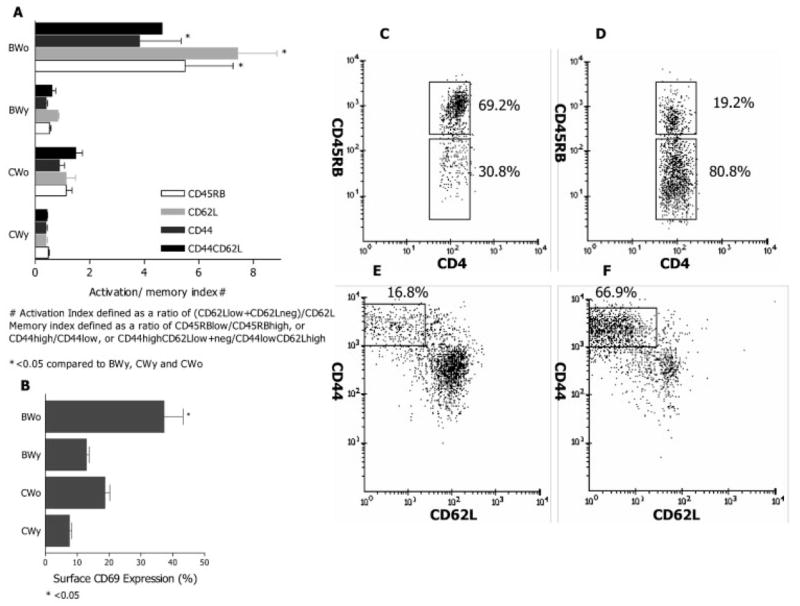

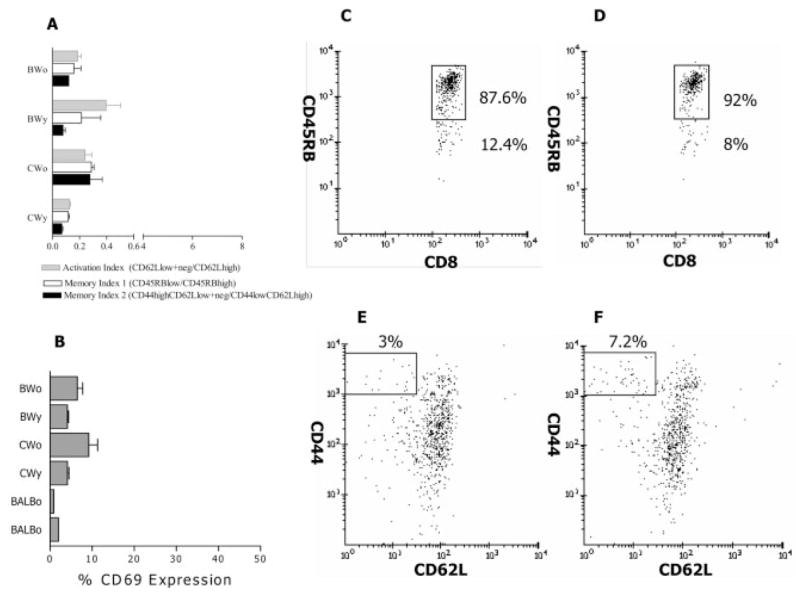

Since effector CD8+ Ti are likely to be activated and memory cells for self antigens should be present, we characterized appropriate surface phenotypes of freshly harvested CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, in BWF1 and control mice of different ages. Data in Fig. 3A, 4A are presented as activation and memory indices. Activation index is defined as the ratio of cells that are CD62Llow/neg over the CD62Lhigh cells. Memory index is the ratio of CD45RBlow over CD45RBhigh cells or of CD44highCD62low/neg over CD44lowCD62Lhigh cells. These indices describe distribution of cells within a particular subset and allow comparisons between groups. As CWF1 and BWF1 mice age, CD4+ T cells displaying markers of activation and memory expand (Fig. 3). This is particularly dramatic in BWF1 mice; numbers expand six- to eightfold. In CWF1 mice, numbers expand twofold. In contrast, CD8+ T cells bearing activation/memory markers increase with age twofold or less in both strains (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Surface phenotype of splenic CD4+ T cells. Spleen cells pooled from three to six mice, groups as described in Fig. 2, were analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are shown as the means ± SEM from four experiments. (A) Activation and memory indices in various groups. All indices were significantly higher in old BWF1 mice compared to all other groups (*p<0.05 by ANOVA). (B) Surface expression of CD69 occurred on a higher proportion of CD4+ T cells from old BWF1 compared to other groups (*p<0.05). (C, D) Expression of CD45RB on CD4+ T cells from young (C) vs. old (D) mice. Expression of CD45RB fell dramatically with age. (E, F) Expression of CD44 on surface of CD62L+ or CD62L− CD4+ T cells in young (E) vs. old (F) mice. Proportions of CD44highCD62Llow cells increased dramatically with age. Altogether, these data indicate that greatly increased numbers/proportions of CD4+ T cells express markers of activation and memory in old BWF1 mice compared to young.

Fig. 4.

Surface phenotype of splenic CD8+ T cells in young and old CWF1 and BWF1 mice. Panels are in same order as for Fig. 4. Note that in contrast to CD4+ T cells, activation/memory markers are not elevated in the CD8+ T cells of old BWF1 mice compared to other groups.

2.5 Measurement of activation, anergy, and apoptosis in BWF1 CD8+ T cells following activation

If peripheral CD8+ T cells from old BWF1 mice are less easily activated than normal, this might explain their low activation surface markers. Old BWF1 mice were immunized with the VH peptide A6H31–45, which contains an MHC class I-binding motif [4]. Spleen cells were harvested 1 week after a booster immunization. As shown in Fig. 5A, the proportion of CD8+ T cells with surface CD62Llow, CD69+ (i.e. activated cells) was significantly increased in the old BWF1 immunized group (14–19%) compared to cells from naive or immunized old CWF1 mice (2–6%). CD8+ T cells from old nephritic BWF1 mice can be activated by peptide immunization. To address potential impairment in expansion of activated peripheral CD8+ Ti, we asked whether BWF1 activated CD8+ T cells were anergic. We measured ability of IL-2 to increase proliferation of CD8+ T cells from young or old BWF1 mice after polyclonal activation by plate-bound anti-CD3. In old BWF1 mice, addition of IL-2 did not increase proliferative responses (data not shown).

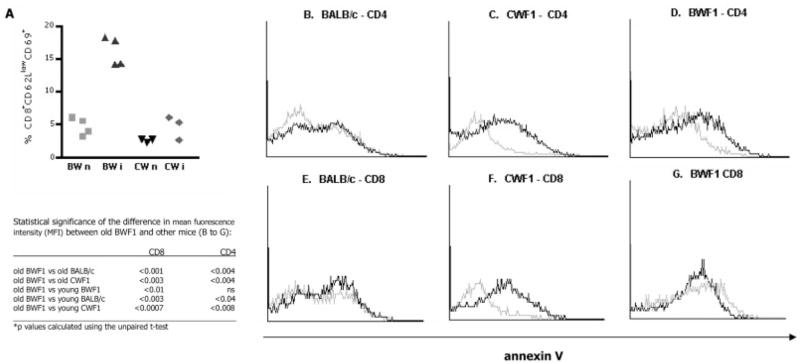

Fig. 5.

Characteristics of CD8+ T cells from old BWF1 and old CWF1 mice after activation in vivo or in vitro. (A) Higher proportion of splenic CD8+ T cells from immunized old BWF1 express activation markers 1 week after a single booster immunization with peptide A6.1 31–45. Each point represents a single mouse. n: naive; i: immunized. p<0.02 by ANOVA for old BWF1 immunized compared to all other groups. Apoptosis of T cells following activation with plate-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 after 12 h in culture was measured by annexin V staining in flow cytometry experiments on co-cultures of CD4+, CD8+, and B cells from splenocytes of mice immunized with A6.31. The table shows statistical analysis of comparison of means of mean fluorescence intensity for annexin V staining in three to five separate experiments in each mouse group. Results of representative individual experiments are shown in (B–G). Cells from young mice are shown in black, from old mice in gray. (B–D) Annexin V staining of CD4+-gated cells in lupus-prone (BWF1) mice, normal mice (BALB/c), and normal MHC-matched control mice (CWF1). (E–G) Comparison of annexin V staining among CD8+ T cells in a representative experiment of five on groups of three to five mice per group. Measurement of cell death by 7-AAD staining gave analogous results (not shown).

Since the CD8+ T cells in old BWF1 mice were not anergic, we studied survival of these cells via annexin V or 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) staining in young vs. old BWF1 mice after activation by anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 after 12 h of culture (Fig. 5B–G and Table in Fig. 5). Proportions of dying CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells after activation were similar in young and old BALB/c mice (Fig. 5B, E). In BWF1 mice and CWF1 mice, fewer activated CD4+ T cells died in old compared to young mice (Fig. 5C, D). CD8+ T cells from old BWF1 mice showed increased apoptosis (Fig. 5G) compared to old CWF1 mice (Fig. 5F), suggesting inappropriate cell death of CD8+ T cells in old BWF1 mice. 7-AAD staining experiments mirrored the above findings for all data sets (not shown). Failure of CD8+ T cells to survive after activation might partly explain their failure to exert effector functions and/or to survive in short-term cultures. Indeed, we could not maintain in culture peptide-specific CD8+ Ti cell lines from BWF1 mice hyperimmunized with A6H31–45 or with the A6.1 mAb: the cells proliferated to the peptide but did not survive in culture more than 30 days, and none exhibited Ti activity in vitro in enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays for anti-DNA (Fig. 1A).

2.6 CD8+ inhibitory T cells can control autoantibody production

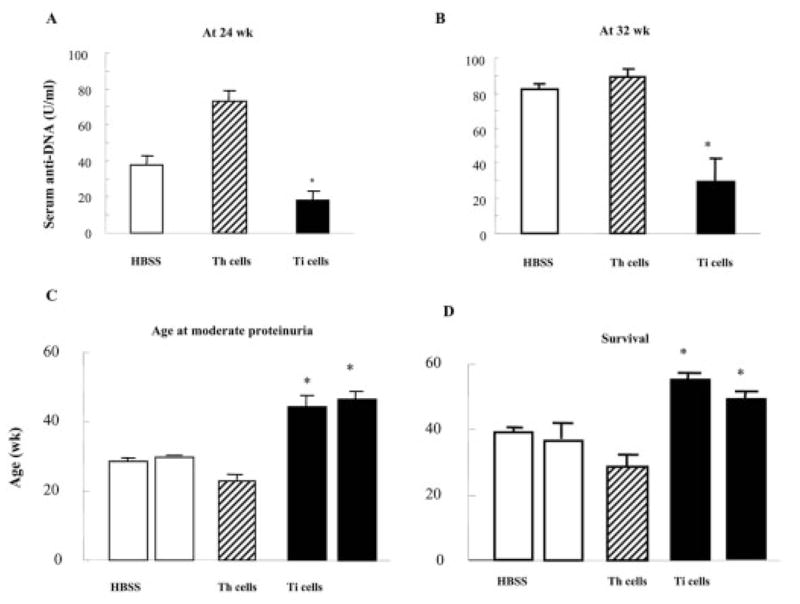

We wondered whether impairment of the CD8+ Ti function in old BWF1 mice was responsible for their inability to suppress or whether the environment in which suppression occurred had primary relevance. CWF1-derived Ti cell lines that expanded in sufficient numbers were injected into BWF1 mice. Transfer of 4×106 cells from a CD8+ Ti cell line (CWF1 #3) twice into BWF1 mice at 2-week intervals significantly decreased anti-DNA production at two time points, compared to mice receiving only medium, or a control CD4+ Th cell line (Fig. 6A, B).

Fig. 6.

In vivo transfer of CWF1 CD8+ Ti cell line #3 into young BWF1 mice (two injections 2 weeks apart of 4×106 cells activated with an A6.1 peptide and syngeneic APC), compared to injections of saline or of identical numbers of activated CWF1 CD4+ Th cells from another peptide-specific line, suppressed lupus-like disease. (A, B) Mean serum IgG anti-DNA (± SEM) was significantly decreased at 24 and 32 weeks of age in Ti-transferred recipients; *p<0.05 and p<0.001, respectively, by ANOVA. (C) Transfer of CD8+ Ti delayed the onset of proteinuria (≥2+) (p<0.01 compared to either saline or Th). (D) Transfer of CD8+ Ti prolonged survival compared to saline or Th cell transfer (*p=0.01 comparing group receiving Ti cells to both other groups by ANOVA). Numbers of mice were 5 receiving CD8+ Ti, 21 receiving saline, 16 receiving CD4+ Th.

Transfer experiments with CWF1 CD8+ Ti were repeated in young BWF1 recipients, with controls receiving medium only or the same number of cells from a BWF1 CD4+ Th cell line. Fig. 2C shows that mice inoculated with the Ti cell lines CWF1 #3 and CWF1 #4 developed proteinuria (≥2+) at a significantly later age than controls receiving medium or the CD4 Th cell line. Furthermore, survival was significantly improved in BWF1 mice injected with either of two Ti cell lines vs. controls (Fig. 2D).

3 Discussion

We report here that hyperimmunization with a BWF1 mouse-derived Ab induced functional peptide-reactive CD8+ Ti cells in normal CWF1 mice that suppressed autoantibody production in vitro. The peptide used (A6.1 31–45) – derived from the VH region of the A6.1 mouse anti-DNA mAb [6] – contains at least two epitopes: one binds an MHC class II molecule, I-Ed [12], and the other binds an MHC class I molecule, Kd [4]; both can be presented by either CWF1 or BWF1 APC.

Interestingly, BWF1 mice immunized the same way did not generate functional Ti cells, even though we could identify CD8+ T cells that proliferated in response to the immunogen. Furthermore, these CD8+ T cells did not survive in culture more than 30 days. Although total numbers of CD8+ T cells are maintained as BWF1 age (in contrast to normal mice where they decline in numbers over time), they expanded less (approximately 1.2-fold) than did CD4+ T cells (fourfold) and B cells (2.5-fold) in the same mice. These data are consistent with results reported by other groups that indicated expansion with age in BWF1 CD4+ T cells [16], and decrease of the numbers of CD8+ T cells [17]. Since the immunizing mAb and its peptides were derived from a BWF1 mouse, Ti epitopes must be abundant in that strain, and yet Ti do not expand well.

But why are CD8+ Ti impaired in mature BWF1 mice, despite the fact that autoantibodies containing multiple T cell epitopes are abundant? Our data suggest that several defects are important. In older BWF1 females, there is lower secretion of IL-2 and TGF-β1 by splenic T cells and CD8+ T cells, respectively, compared to CWF1 mice. These cytokines participate in evolution of effector Ti [13–15, 18, 19]. Peripheral blood cells from humans with SLE, like the BWF1 mice, produce abnormally low levels of active and total TGF-β, which may impair regulation of autoantibodies [20]. In fact, unmanipulated CD8+ peripheral blood T cells from patients with SLE enhanced, rather than suppressed, Ig production by B cells [21]. Exposure of such CD8+ cells to IL-2 plus TGF-β restored their suppressive capacity [18]. In some cases addition of IL-2 to cultures was sufficient to restore suppression, and addition of anti-TGF-β blocked the inhibitory activity in most cases. In our CWF1 Ti, blocking TGF-β also prevented suppression of anti-DNA production in vitro [6].

Other investigators have shown that the CTL/suppressor functions of CD8+ T cells are impaired in humans with lupus [5]. We also showed that the proportions of CD8+ cells that express surface markers of activation and memory are surprisingly low in aging BWF1 mice. Although 70–80% of peripheral CD4+ T cells from nephritic mice have such markers, they are present on fewer than 10% of CD8+ cells from the same mice. Our data show that these CD8+ T cells are not resistant to activation. In fact, following immunization with a VH peptide, 14–19% of splenic CD8+ cells displayed markers of activation, compared to 2–6% in age-matched immunized CWF1 mice. Furthermore, the cells were not anergic. A likely explanation for the relatively low numbers of activated/memory CD8+ T cells in older BWF1 mice is that high proportions undergo apoptosis following activation, compared to CD4+ T cells or to CD8+ T cells from non-autoimmune strains. An increased rate of apoptosis following the activation that must occur continually in CD8+ T cells when autoantibody titers are high and disease begins, may be quite important in accounting for the inability of those cells to control disease. The observation would also account for our inability to maintain these cells in culture.

Krakauer and Waldmann [22] were probably the first to show loss of suppressor T cell functions in adult female BWF1 mice. Their work predates identification of the CD8 surface marker. They showed that Con A-pulsed splenocytes from old BWF1 females, compared to those of young BWF1, failed to suppress PWM-driven IgM synthesis; this could have resulted from abnormalities in CD4+ and/or CD8+ regulatory/inhibitory T cells. Our findings are also consistent with prior reports that Ly2+ cells from old BWF1 mice fail to decrease IgG anti-DNA produced by co-cultures of B cells with L3T4+ cells, in contrast to cells from young mice [23].

To our knowledge, ours is the first report of differences in activation/memory markers in BWF1 CD8+ T cells compared to normal mice, and of decreased survival as an acquired defect. We suggest that these changes contribute to the dysregulation that allows continual production of pathogenic autoantibodies in this lupus-prone strain. Experiments are in progress to identify the molecular basis of these phenomena.

Overcoming the defects that prevent emergence of CD8+ suppressor/cytotoxic cells in BWF1 mice could be an effective strategy to suppress autoreactivity. CD8+ Ti have been shown to prevent or inhibit non-lupus autoimmune conditions in rodents, including myasthenia gravis induced by anti-AChR [24], EAE induced by adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells [25], and experimental autoimmune orchitis [26]. Susceptibility to EAE in different rat strains may depend on their differences in quantities of CD8+ T suppressor/inhibitor cells [27]. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide-specific CD8+CD28− T cells were suppressive in a mouse model of chronic EAE, and probably function via direct contact which prevents up-regulation of costimulatory molecules on APC, thus preventing expansion of disease-generating CD4+ T cells [28]. Regarding the role of CD8+ T cells in other models of murine lupus, CD8+ T cell depletion in (NZW × BXSB) F1 mice accelerated spontaneous lupus-like disease and decreased survival [29]. Treatment with anti-CD8 accelerated experimental SLE disease induced in BALB/c mice by immunization with the 16/6Id idiotype [30], and transfer of a CD8+ Ti line specific for 16/6Id prevented disease [31].

In our system, transfer of CWF1 CD8+ Ti induced by antigen immunization into BWF1 mice delayed autoimmunity. Those Ti were suppressive via secretion of TGF-β, and were not cytotoxic. Although we could not induce similar Ti in BWF1 mice using the same immunization protocols, we could induce CD8+ Ti in BWF1 by a tolerizing strategy with high doses of peptide (Hahn, B. H., manuscript in preparation). Previously, we also induced CD8+ Ti in BWF1 mice by vaccination with DNA encoding peptides that bind the MHC class I molecules [4]. For all the above reasons, it is possible to overcome the defects that occur in BWF1 CD8+ T lymphocytes that prevent them from evolving into effective suppressors of autoimmunity. Identifying the basis of these defects may lead to new therapeutic possibilities.

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Mice

C57BL/6, NZB/B1nj, NZW/Lacj, and BALB/c mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Strains were intercrossed to generate BWF1 and CWF1 mice in the University of Cincinnati or UCLA Vivaria. Female mice were used in all experiments. Studies were performed in accordance with the institutional animal research committee guidelines.

4.2 Peptides

The 15-mer peptides A6.1 31–45 and A6.1 41–54 derived from the VH region of an anti-DNA mAb (A6.1), and HYHEL-4 31–45 derived from the same VH region of a non-autoreactive mAb, and an I-Ed-binding peptide of hen egg lysozyme (HEL 106) were synthesized at Mimotopes Laboratories (Clayton, Australia). Each peptide chromatographed as a sharp single peak with the expected molecular mass.

4.3 Immunization of mice

CWF1 or BWF1 mice were immunized i.p. with 20 μg A6.1 (purified from ascites fluid as IgG), or 10 μg peptide, emulsified in CFA, and boosted with 10–20 μg A6.1 or peptide in IFA.

4.4 Purification of cells

Spleen cells from individual mice purified as mononuclear cells on Ficoll-Hypaque were enriched for CD4+, CD8+, and B cells by positive selection with the AutoMACS magnetic purification system using microbead-coated Ab (anti-L3T4, anti-CD8a, and anti-B220; all from Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA). Purity of the cell populations determined by FACS was 92–99%.

4.5 Determination of T cell help for anti-DNA Ab synthesis by ELISPOT

ELISPOT assay methods detecting individual lymphocytes secreting IgG anti-DNA have been described [6]. AFC were recorded as number of AFC per 106 B cells.

4.6 Determination of serum anti-DNA Ab by ELISA

4.7 Flow cytometry

Spleen cells were assayed for each individual mouse (five to six mice per experimental group). Total splenocytes or T cell-enriched fractions (anti-Thy1.2-selected) were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated mAb: anti-CD4-peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP) or anti-CD8-PerCP, anti-CD25-FITC, anti-CD44-PE, anti-CD45RB-FITC, anti-CD62L-FITC, anti-CD69-PE, anti-CTL-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4)-PE, anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2-biotin, and anti-IgM-PE. All reagents were from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA) and used according to manufacturer’s protocols. Cells were sorted using a FACS-Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with the FCS Express analysis software (De Novo Software, Thornhill, Canada).

4.8 Assessment of active TGF-β1 by luciferase chemiluminescence assay

Frozen mink cells transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter plasmid provided by Drs. Dixon Gray and David Horwitz (University of Southern California) were cultured at 7×104 cells/ml for 3 h in serum-free AIM V medium (Gibco Life Technologies). Supernatants of CD8+ cell cultures added to the cells were incubated at 37°C for 14–16 h. Total cell lysates were tested for luciferase according to guidelines provided with a kit from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI). Quantities of active TGF-β1 were measured immediately with a Berthold Orion Microplate Luminometer.

4.9 Establishing T cell lines

Splenic single-cell suspensions from mice immunized with A6.1 31–45 or A6.1 41–54 fractionated into CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were cultured and periodically stimulated with syngeneic APC, the immunizing peptide, and Con A supernatant [6].

4.10 Adoptive transfer of T cell lines

CD8+ Ti cell lines were stimulated in vitro with the immunizing peptide, syngeneic APC, and Con A supernatant. Live cells (4×106) were injected i.v. twice at 2-week intervals beginning in 12-week-old BWF1 mice. Control mice received the same numbers of a CWF1-derived CD4+ Th cell line, or saline.

4.11 Allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction

As a positive control, irradiated C57B6 (H-2b) splenocytes at 5 × 105/ml were co-cultured with BWF1 (H-2d/z) or CWF1 (H-2d/z) splenocytes at 105/ml at 37°C for 5 days. Similarly, irradiated BWF1 splenocytes were co-cultured with CWF1 cells, and irradiated CWF1 cells with BWF1 splenocytes. On day 5 of culture 1 μCi [3H]thymidine was added to cultures; proliferation was assayed 16 h later.

4.12 Assessment of anergy and apoptosis in CD8+ T cells

Anergy was measured as proliferation in the presence of IL-2. Magnetic-bead-purified CD8+ T cells (1×106) stimulated with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb (2 μg/ml) with irradiated syngeneic B cells (2×105) in a 24-well plate with or without irradiated CD4 T cells (2×106) and/or rIL-2 for 72 h were assayed for proliferation using [3H]thymidine incorporation during the last 12 h. CD8+ cell survival was assessed by exclusion of 7-ADD+ cells in four-color stain after 12 h of co-cultures of CD8+, CD4+, and B cells in 24-well plates; apoptosis was identified using annexin V. The reagents were from BD Biosciences. Lymphocyte subsets were sorted by flow cytometry and analyzed with FCS Express software.

4.13 Assessment of clinical disease

Proteinuria was measured using Albustix (range 0–4+) [3, 5, 6].

4.14 Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed with the Graph Pad Prism 3.0 software (San Diego, CA), using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test to compare two groups and ANOVA to compare more than two groups.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (AI/AR46776 to B.H.H., AR47322 and AR47363 to R.R.S.), Arthritis Foundation (Ohio Valley and Southern California Chapters), Lupus Foundation of America, Arthritis National Research Foundation, Dorough Foundation, Paxson Family, California Community Foundation, and Jeanne Rappaport.

Abbreviations

- AFC

Antibody-foming cells

- BWF1

(NZB × NZW) F1

- CWF1

(BALB/c × NZW) F1

- Ti

Inhibitory T (cell)

References

- 1.Hahn BH. Antibodies to DNA. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1359–1368. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shivakumar S, Tsokos GC, Datta SK. T cell receptor γ/δ expressing double-negative (CD4−/CD8−) and CD4+ T helper cells in humans augment the production of pathogenic anti-DNA autoantibodies associated with lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 1989;143:103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh RR, Hahn BH, Tsao BP, Ebling FM. Evidence for multiple mechanisms of polyclonal T cell activation in murine lupus. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1841–1849. doi: 10.1172/JCI3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan GC, Singh RR. Vaccination with minigenes encoding VH-derived major histocompatibility complex class I-binding epitopes activates cytotoxic T cells that ablate autoanti-body-producing B cells and inhibit lupus. J Exp Med. 2002;196:731–741. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filaci G, Bacilieri S, Fravega M, Monetti M, Contini P, Ghio M, et al. Impairment of CD8+ T suppressor cell function in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2001;166:6452–6457. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh RR, Ebling FM, Albuquerque DA, Saxena V, Kumar V, Giannini EH, Marion TN, Finkelman FD, Hahn BH. Induction of autoantibody production is limited in nonautoimmune mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:587–594. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh RR, Kumar V, Ebling FM, Southwood S, Sette A, Sercarz EE, Hahn BH. T cell determinants from autoantibodies to DNA can upregulate autoimmunity in murine systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2017–2027. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jouanne C, Avrameas S, Payelle-Brogard B. A peptide derived from a polyreactive monoclonal anti-DNA natural antibody can modulate lupus development in (NZB × NZW) F1 mice. Immunology. 1999;96:333–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, Smith DS, Guth A, Wysocki LJ. A receptor presentation hypothesis for T cell help that recruits autoreactive B cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:1562–1571. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams WW, Staines NA, Muller S, Isenberg DA. Human T cell responses to autoantibody variable region peptides. Lupus. 1995;4:464–471. doi: 10.1177/096120339500400608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dayan M, Segal R, Sthoeger Z, Waisman A, Brosh N, Elkayam O, et al. Immune response of SLE patients to peptides based on the complementarity determining regions of a pathogenic anti-DNA monoclonal antibody. J Clin Immunol. 2000;20:187–194. doi: 10.1023/a:1006685413157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh RR. Potential use of peptides and vaccination to treat systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:399–406. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200009000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwitz DA, Zheng SG, Gray JD. The role of the combination of IL-2 and TGF-β or IL-10 in the generation and function of CD4+CD25+ and CD8+ regulatory T cell subsets. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:471–478. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0503228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shedlock DJ, Shen H. Requirement for CD4 T cell help in generating functional CD8 T cell memory. Science. 2003;300:337–340. doi: 10.1126/science.1082305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerwenka A, Carter LL, Reome JB, Swain SL, Dutton RW. In vivo persistence of CD8 polarized T cell subsets producing type 1 or type 2 cytokines. J Immunol. 1998;161:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rozzo SJ, Drake CG, Chiang BL, Gershwin ME, Kotzin BL. Evidence for polyclonal T cell activation in murine models of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 1994;153:1340–1351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito S, Ueno M, Nishi S, Arakawa M, Fujiwara M. Suppression of spontaneous murine lupus by inducing graft-versus-host reaction with CD8+ cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:260–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb07939.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohtsuka K, Gray JD, Quismorio FP, Jr, Lee W, Horwitz DA. Cytokine-mediated down-regulation of B cell activity in SLE: effects of interleukin-2 and transforming growth factor-β. Lupus. 1999;8:95–102. doi: 10.1191/096120399678847498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray JD, Hirokawa M, Horwitz DA. The role of transforming growth factor-β in the generation of suppression: an interaction between CD8+ Tand NK cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1937–1942. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohtsuka K, Gray JD, Stimmler MM, Toro B, Horwitz DA. Decreased production of TGFβ by lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 1998;160:2539–2545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linker-Israeli M, Quismorio FP, Jr, Horwitz DA. CD8+ lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus sustain, rather than suppress, spontaneous polyclonal IgG production and synergize with CD4+ cells to support autoanti-body synthesis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1216–1225. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krakauer RS, Waldmann TA, Strober W. Loss of suppressor T cells in adult NZB/NZW mice. J Exp Med. 1976;144:663–673. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.3.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morimoto C, Reinherz EL, Schlossman SF, Schur PH, Mills JA, Steinberg AD. Alterations in immunoregulatory T cell subsets in active systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:1171–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI109948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pachner AR, Kantor FS. In vitro and in vivo actions of acetylcholine receptor educated suppressor T cell lines in murine experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1984;56:659–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellerman KE, Powers JM, Brostoff SW. A suppressor T-lymphocyte cell line for autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nature. 1988;331:265–267. doi: 10.1038/331265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukasa A, Hiramine C, Hojo K. Generation and characterization of a continuous line of CD8+ suppressive regulatory T lymphocytes which down-regulates experimental autoimmune orchitis (EAO) in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;96:138–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun D, Whitaker JN, Wilson DB. Regulatory T cells in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. III. Comparison of disease resistance in Lewis and Fischer 344 rats. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1101–1106. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199904)29:04<1101::AID-IMMU1101>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Najafian N, Chitnis TJ, Salama AD, Zhu B, Benou C, Yuan X, Clarkson MR, Sayeghj MH, Khoury SJ. Regulatory functions of CD8+CD28– T cells in an autoimmune disease model. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1037–1048. doi: 10.1172/JCI17935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adachi Y, Inaba M, Sugihara A, Koshiji M, Sugiura K, Amoh Y, Mori S, Kamiya T, Genba H, Ikehara S. Effects of administration of monoclonal antibodies (anti-CD4 or anti-CD8) on the development of autoimmune diseases in (NZW × BXSB) F1 mice. Immunobiology. 1998;198:451–464. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(98)80052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruiz PJ, Zinger H, Mozes E. Effect of injection of anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 monoclonal antibodies on the development of experimental systemic lupus erythematosus in mice. Cell Immunol. 1996;167:30–37. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blank M, Ben-Bassat M, Shoenfeld Y. Modulation of SLE induction in naive mice by specific T cells with suppressor activity to pathogenic anti-DNA idiotype. Cell Immunol. 1991;137:474–486. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90095-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]