Abstract

Objective

CD1d-reactive invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells secrete multiple cytokines upon T cell receptor (TCR) engagement and modulate many immune-mediated conditions. The purpose of this study was to examine the role of these cells in the development of autoimmune disease in genetically lupus-prone (NZB × NZW)F1 (BWF1) mice.

Methods

The CD1d1-null genotype was crossed onto the NZB and NZW backgrounds to establish CD1d1-knockout (CD1d0) BWF1 mice. CD1d0 mice and their wild-type littermates were monitored for the development of nephritis and assessed for cytokine responses to CD1d-restricted glycolipid α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer), anti-CD3 antibody, and con-canavalin A (Con A). Thymus and spleen cells were stained with CD1d tetramers that had been loaded with αGalCer or its analog PBS-57 to detect iNKT cells, and the cells were compared between BWF1 mice and class II major histocompatibility complex–matched nonautoimmune strains, including BALB/c, (BALB/c × NZW)F1 (CWF1), and NZW.

Results

CD1d0 BWF1 mice had more severe nephritis than did their wild-type littermates. Although iNKT cells and iNKT cell responses were absent in CD1d0 BWF1 mice, the CD1d0 mice continued to have significant numbers of interferon-γ–producing NKT-like (CD1d-independent TCRβ+,NK1.1+ and/or DX5+) cells. CD1d deficiency also influenced cytokine responses by conventional T cells: upon in vitro stimulation of splenocytes with Con A or anti-CD3, type 2 cytokine levels were reduced, whereas type 1 cytokine levels were increased or unchanged in CD1d0 mice as compared with their wild-type littermates. Additionally, numbers of thymic iNKT cells were lower in young wild-type BWF1 mice than in nonautoimmune strains.

Conclusion

Germline deletion of CD1d exacerbates lupus in BWF1 mice. This finding, together with reduced thymic iNKT cells in young BWF1 mice as compared with nonautoimmune strains, implies a regulatory role of CD1d and iNKT cells during the development of lupus.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation of multiple organs and uncontrolled production of autoantibodies (1). In humans and animals with SLE, diverse sets of T helper cells can promote autoantibody production (2–4). The emergence of such autoreactive T helper cells in lupus is accompanied by either a loss or a defective induction of regulatory T cells (4–6). Elucidating such impairments in regulatory networks would facilitate our understanding of the pathogenesis of lupus.

Studies in the late 1980s identified cells that express cell surface markers characteristic of natural killer (NK) cells as well the CD3–T cell receptor (TCR) complex in the thymus, spleen, and bone marrow (7–10). Such natural killer T (NKT) cells rapidly produce interleukin-4 (IL-4) (11–13) and include 2 subsets, CD4+ T cells and double-negative (DN) T cells. These cells express intermediate levels of TCR, with a highly skewed TCR Vβ family (7,14) and an invariant TCR α-chain Vα14–Jα281 (now called Vα14–Jα18) (15,16), the expression of which was previously identified by use of a panel of suppressor T cell hybridomas (17). Simultaneous studies identified the counterpart of murine NKT cells in humans, Vα24–JαQ TCR (now called Vα24–Jα18), among DN peripheral blood T cells (18). Further studies showed that the development of NKT cells was independent of class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) expression, but required the class I MHC–like molecule CD1d (19). CD1d is an evolutionarily conserved β2-microglobulin (β2m)–associated protein (20), which is widely expressed on hematopoietic-derived cells (21). CD1d binds glycolipid antigens, such as α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer), and activates NKT cells (22).

Taken together, these studies suggest that NKT cells are a separate T cell lineage characterized by CD1d-restricted lipid antigen reactivity, an invariant TCR (Vα14–Jα18 paired with Vβ8.2/Vβ7/Vβ2 in mice and Vα24–Jα18 paired with Vβ11 in humans), expression of NK cell markers NK1.1/DX5, and rapid cytokine response (20,23–25). Subsequent studies, however, led to the realization that NKT cells are a diverse group of cells, which likely differ in their functions (26,27). For example, some CD1d-restricted T cells, such as immature and recently activated cells, do not express NK markers. Notably, CD1d-restricted T cells from MRL-lpr/lpr (MRL-lpr), (NZB × NZW)F1 (BWF1), and hydrocarbon oil–induced animal models of SLE are mostly negative for NK1.1 or DX5 (28–31). In addition, some CD1d-restricted T cells express diverse TCR α-chains instead of the invariant Vα14–Jα18 chain. Finally, some T cells that express NK markers NK1.1 and DX5 are not CD1d-restricted.

These observations led a panel of investigators to propose the following classification for NKT cells (26). Class I cells are invariant NKT (iNKT) cells, which are also called classic NKT cells or type I NKT cells. They can best be detected using CD1d tetramers loaded with glycolipids, such as αGalCer. Class II cells are variant NKT cells, which are also called type II or nonclassic NKT cells. They are CD1d-dependent but express diverse TCR α-chains. Class III cells are NKT-like cells. They are CD1d-independent NK1.1/DX5+ T cells.

Ample evidence supports a protective role of iNKT cells against a variety of immune-mediated inflammatory conditions (29,32–34). However, iNKT cells can also aggravate the same immune-mediated conditions, depending on the stage of disease when iNKT cells are manipulated or on the nature of the underlying immune perturbation (35–38). It is important to unearth the full spectrum of these protective and pathogenic roles of iNKT cells in immune-mediated diseases, given the nonpolymorphic nature of CD1d that makes it an attractive target of immune therapy on a mass scale.

To determine the role of iNKT cells in SLE, a few studies have investigated alterations in the frequency and functions of these cells in the peripheral blood of patients and healthy subjects. Two studies, one each from Japan and Europe, found a significant reduction in circulating TCR Vα24+,Vβ11+ DN T cells (composed of iNKT cells as well as other T cells) in patients with SLE as compared with healthy subjects (39,40). Simultaneously, another study found that whereas invariant Vα24–JαQ (Vα24–Jα18) TCR dominated DN Vα24+ T cells at a high frequency in healthy subjects, this invariant TCR was reduced to undetectable levels in DN Vα24+ T cells from patients with active SLE (41). The invariant Vα24+,Jα18+ T cells were restored to normal levels when patients were successfully treated with corticosteroids to achieve disease remission (41). Moreover, whereas Vα24+,Vβ11+ DN T cells from all healthy subjects proliferated in response to αGalCer, 5 of the 10 SLE patients tested exhibited no such response to αGalCer (39). These data clearly suggest that peripheral blood iNKT cells are impaired in patients with SLE.

To understand the implications of these findings in humans, we and other groups of investigators have used animal models of SLE, such as BWF1, MRL-lpr, and hydrocarbon oil–injected mice (28–31,42). BWF1 mice spontaneously develop a T cell–dependent, autoantibody-mediated lupus nephritis that mimics human SLE (43). One group of investigators has treated BWF1 mice with anti-CD1d antibody to suppress iNKT cells (42). This approach, however, may not achieve complete neutralization of CD1d and its effects. Furthermore, a recent study showed that CD1d ligation on human monocytes leads to NF-κB activation and IL-12 production (44). Thus, the anti-CD1d antibody that was used to neutralize CD1d might cause unintended consequences on various immune cells due to CD1d ligation, with ensuing effects on lupus. Hence, we introgressed a CD1d1-null (CD1d0) genotype into NZB and NZW strains to generate CD1d-deficient BWF1 mice that have no iNKT cells. We monitored disease development as well as responses of iNKT cells, NKT-like cells, and conventional T cells in these mice. In addition, we assessed iNKT cell frequency at different stages of disease development in wild-type BWF1 mice. We describe herein our findings and briefly review the current understanding of the role of iNKT cells in lupus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

BWF1, NZB, NZW, and BALB/c mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Some BALB/c × NZW and NZB × NZW mice were bred locally to generate (BALB/c × NZW)F1 (CWF1) and BWF1 mice, respectively. The CD1d0 129 × C57BL/6 mice (45) were crossed onto the NZB and NZW backgrounds for 10 and 12 generations, respectively. At each backcross, the heterozygous (CD1d+/−) mice were identified by polymerase chain reaction analysis, as reported elsewhere (28). The N10 CD1d+/− NZB mice were crossed with N12 CD1d+/− NZW mice to establish CD1d+/+ (CD1d+) and CD1d−/− (CD1d0) BWF1 mice. The CD1d0 phenotypes were further confirmed by demonstrating the absence of CD1d on peripheral blood lymphocytes by flow cytometry using anti-CD1d monoclonal antibody (mAb) 1B1 (PharMingen, San Diego, CA). To confirm that mice from the final backcross were indeed congenic, they were screened using a battery of simple sequence repeat markers (www.informatics.jax.org), all of which discriminated congenic strains from the 129/B6 donors.

Assessment of lupus disease

Survival and renal disease were assessed in the mice. Proteinuria was measured with a colorimetric assay strip for albumin (Albustix; Bayer, Elkhart, IN) and graded on a scale of 0–4+, where 0 = absent, 1+ = ≤30–99 mg/dl (mild), 2+ = 100–299 mg/dl (moderate), 3+ = 300–1,999 mg/dl (marked), and 4+ = ≥2,000 mg/dl (severe). Severe proteinuria was defined as a value ≥300 mg/dl on 2 consecutive examinations, as described previously (3). For renal histology, paraffin sections of kidneys were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Masson’s trichrome, and scored for various histologic features in a blinded manner, as described previously (46). Briefly, the mean scores for individual pathologic features were summed to obtain the 4 main scores: the glomerular activity score, the tubulointerstitial activity score, the chronic lesion score, and the vascular lesion score. These scores were converted into indices by dividing them by the number of individual features examined to obtain those scores. The indices thus obtained were then averaged and summed to determine a composite kidney biopsy index.

Measurement of anti-DNA antibody

IgG anti-DNA antibody was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as described previously (6). Briefly, Costar high-binding enzyme immunoassay/radioimmunoassay plates were coated with sonicated, nitrocellulose-filtered calf thymus double-stranded DNA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). After washing and blocking, plates were incubated overnight at 4°C with diluted test or control sera. After washing, alkaline-phosphatase–conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) was added to the plate and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Plates were developed with p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma) and read at 405 nm in a Multiscan ELISA reader (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). A positive reference standard of pooled serum from 1-year-old BWF1 mice was used to convert the anti-DNA antibody optical density values to units per milliliter.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared in PBS buffer with 3% FCS, EDTA, and sodium azide after red blood cell lysis (spleen only) with PharmLyse (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Spleen cells were incubated with anti-CD16/32 (2.4G2; PharMingen) to block Fc receptor γ II/III, followed by staining with conjugated anti-mouse mAb: anti-CD1d (1B1), anti-NK1.1, anti-CD4, and anti-B220; iNKT cells were detected using allophycocyanin-labeled anti-TCRβ (all antibodies obtained from PharMingen) and phycoerythrin–labeled CD1d tetramer loaded with either αGalCer (29) or the αGalCer analog PBS-57 (47). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis was performed using FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using CellQuest (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) or FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) software. Dead cells were excluded from the analysis by electronic gating, based on forward and side light-scatter patterns.

Enrichment for T and NKT-like (TCRβ+,DX5+) cells

Splenic T cells from CD1d0 and CD1d+ mice were enriched using mouse T cell enrichment columns (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). In some experiments, purified T cells were also incubated with anti-NK (DX5) microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) for 30 minutes on ice. After washing once, cells were applied to the column for positive selection of DX5+ T cells, and negative selection of TCRβ+,DX5− cells. The purity of TCRβ+,DX5+ cells and TCRβ+,DX5− cells ranged from 80–90% and 95–97%, respectively.

In vivo TCR cross-linking for iNKT cell activation

As described previously (13,45), mice were injected intravenously with a single 1-μg dose of anti-CD3 mAb (145-2C11; Phar-Mingen) and were euthanized after 90 minutes. Spleen cell suspensions (5 × 106/ml) from these animals were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium (supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 × 10−5M 2-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 100 μg/ml of gentamicin). Supernatants were collected after 2 hours for use in cytokine assays.

In vitro cytokine detection

Spleen cells (1.5 × 106/ml) were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium with 10–100 ng/ml of αGalCer or 2–10 μg/ml of concanavalin A (Con A; Sigma). Supernatants were collected at 24–48 hours and assayed for cytokines. In some experiments, purified T cells (TCRβ+,DX5−) were stimulated with plate-bound anti-mouse CD3 antibody, and supernatants were collected after overnight incubation.

Interferon-γ (IFNγ), IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, and transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) were assayed by sandwich ELISA using paired mAb of rat anti-mouse cytokines, as described previously (48). The following mAb pairs were obtained from PharMingen: R4 6A2 and XMG1.2 for IFNγ, JES6-1A12 and JES6-5H4 for IL-2, 11B11 and BVD6-24G2 for IL-4, JES5-2A5 and SXC-1 for IL-10, C15.6 and C17.8 for IL-12, and A75-2.1 and A75-3.1 for TGFβ1. Purified and biotinylated anti-mouse IL-13 mAb were obtained from R&D Systems. After incubation with the biotinylated mAb, plates were incubated with alkaline phosphatase–conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), developed with p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate, and read at 405 nm.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Purified cells (1.5 × 106/ml) were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (mAb 145-2C11) for 16 hours, followed by incubation with 3 μM monensin for 4 hours. Cells were then stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled anti-NK1.1 in the presence of 2.4G2 and washed twice, followed by fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. The fixed cells were then washed once and treated with FACS permeabilizing solution (Becton Dickinson) for 10 minutes at room temperature. After washing, cells were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, or IFNγ (PharMingen) for 30 minutes on ice, and washed twice before flow cytometry analysis.

Statistical analysis

Antibody and cytokine levels, lymphocyte percentages and numbers, and renal scores were compared using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Frequencies of antibodies and proteinuria were compared using Fisher’s exact test (2-sided). Survival analysis was performed using a log rank test.

RESULTS

Acceleration of lupus nephritis in Cd1d-deficient BWF1 mice

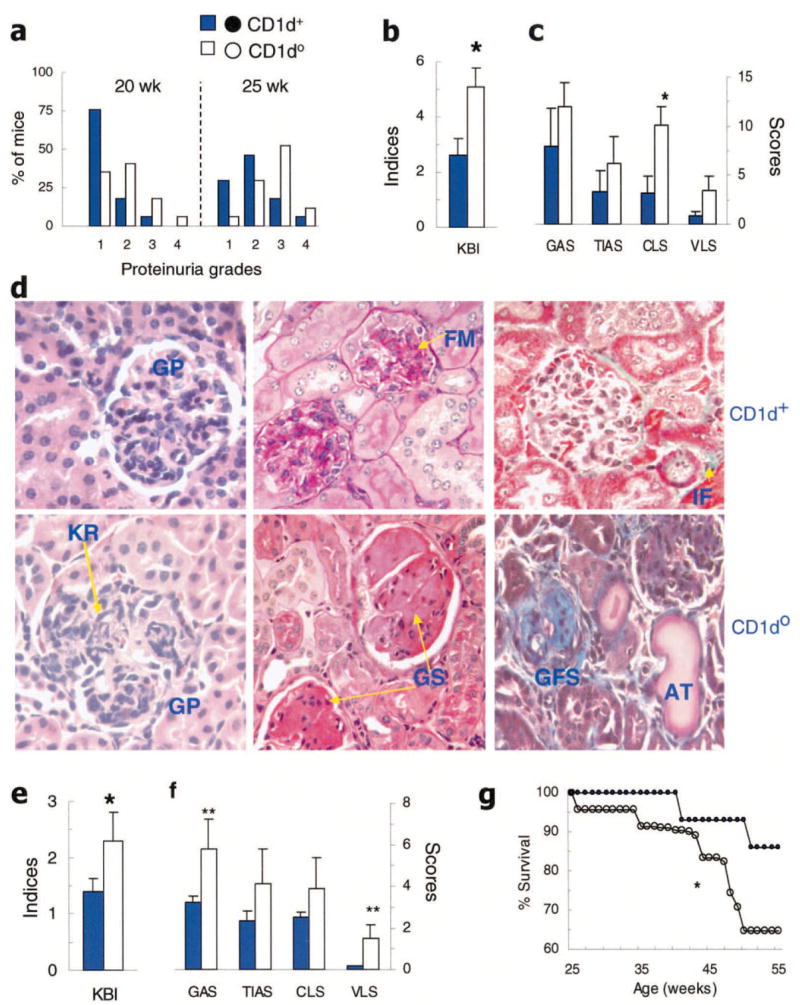

To investigate the effect of CD1d on spontaneous lupus disease, we crossed mice with the CD1d-null genotype onto mice with the NZB and NZW backgrounds and established CD1d0 BWF1 mice by intercrossing N10 CD1d+/− NZB mice with N12 CD1d+/− NZW mice. The CD1d0 and CD1d+ female BWF1 mice (n = 17 per group) were monitored for proteinuria and then euthanized at the age of 6 months to analyze renal histologic features (Figures 1a–d).

Figure 1.

Exacerbation of lupus nephritis in CD1d0 (NZB × NZW)F1 (BWF1) mice. BWF1 mice (CD1d0 and CD1d+ littermates; n = 17 per group) were monitored for proteinuria and then euthanized at 6 months of age to analyze renal histology (see Materials and Methods for details). a, Proteinuria grades (1+ to 4+) in 20-week-old and 25-week-old female mice. Results are shown as the percentage of mice. b and c, Composite kidney biopsy index (KBI) (b) and the individual components of the KBI (glomerular activity score [GAS], tubulointerstitial activity score [TIAS], chronic lesion score [CLS], and vascular lesion score [VLS]) (c) in female mice. Values are the mean and SEM. * = P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test. d, Representative kidney sections from female mice stained with hematoxylin and eosin (left), periodic acid–Schiff (middle), and Masson’s trichrome (right). Kidney sections from CD1d+ mice show glomerular proliferation (GP), focal mesangial proliferation (FM), and minimal interstitial fibrosis (IF; aniline blue staining), whereas sections from the CD1d0 mice show severe glomerular proliferation, infiltration and karyorrhexis (KR), severe glomerulosclerosis (GS), glomerular fibrosis with scarring (GFS), and dilated atrophic tubules (AT). e and f, Composite KBI (e) and the individual components of the KBI (f) in male mice at 8–9 months of age. Values are the mean and SEM of 10 CD1d0 and 8 CD1d+ mice. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.05–0.06, by Student’s t-test. g, Male BWF1 mice in another cohort were monitored for 13 months for survival. Results are shown as the cumulative percentage survival in 23 CD1d0 (○) and 17 CD1d+ (●) mice. * = P < 0.05 by log rank test.

The frequency of severe proteinuria (grade ≥3+) was increased at 25 weeks of age in CD1d0 mice compared with CD1d+ mice (P < 0.05 by Fisher’s exact test) (Figure 1a). The composite kidney biopsy index and its component chronic lesion score, in particular, were also increased in CD1d0 mice (P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test) (Figures 1b and c). The individual components of the chronic lesion score, including interstitial fibrosis (P < 0.05), glomerular scarring (P < 0.02), tubular atrophy (P < 0.05) and fibrous and cellular crescents (P < 0.05) were increased in the CD1d0 mice (data not shown). The glomerular activity score, tubulointerstitial activity score, and vascular lesion score were also increased in CD1d0 mice, although the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.06–0.08) (Figure 1c). Similar results were obtained in another cohort of BWF1 mice (46 CD1d0 mice and 36 CD1d+ mice) that were established by intercrossing N10 CD1d+/− NZW mice with N8 CD1d +/− NZB mice (data not shown).

Representative renal sections demonstrating more advanced kidney lesions in female CD1d0 mice are shown in Figure 1d. A similar increase in renal disease was also observed in male CD1d0 BWF1 mice (Figures 1e and f). In male BWF1 mice that were monitored for 13 months, survival was significantly reduced in CD1d0 mice as compared with their CD1d+ littermates (Figure 1g). The cumulative frequency of severe proteinuria in these mice showed a similar trend (data not shown). These observations suggest that CD1d0 BWF1 mice have accelerated lupus nephritis, with a relatively rapid progression to chronic disease.

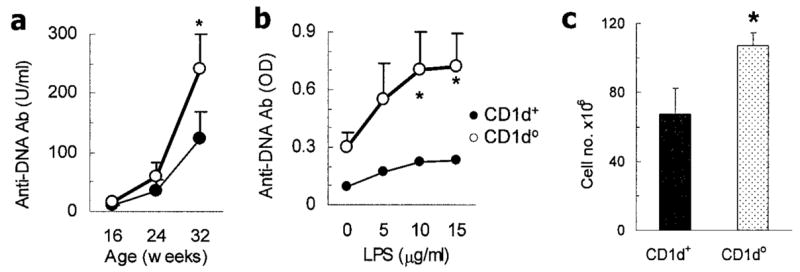

CD1d deficiency and increases in anti-DNA antibody production and lymphoid cellularity

Consistent with increased renal disease, CD1d0 BWF1 mice had a relatively rapid increase in serum IgG anti-DNA antibody levels as compared with their CD1d+ littermates (Figure 2a), and their spleen cells spontaneously produced higher levels of IgG anti-DNA antibody (Figure 2b). IgG anti-DNA antibody production was also increased in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated spleen cells (Figure 2b). Lymphoid organ hypercellularity, another feature of lupus, was also exacerbated in CD1d0 BWF1 mice (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Increased anti-DNA antibody production and enhanced lymphoid cellularity in CD1d0 (NZB × NZW)F1 (BWF1) mice. a, Serum IgG anti-DNA antibody (Ab) levels in 15 CD1d0 and 8 CD1d+ mice. Negative control values in 6 normal BALB/c mice were 3.5 ± 0.8 units/ml (mean ± SEM). b, IgG anti-DNA antibody in spleen cells from 12-week-old BWF1 mice (n = 7 CD1d0 and n = 4 CD1d+). Cells were cultured with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 5 days, supernatants were tested, and optical density (OD) values were determined. c, Enhanced lymphoid cellularity in CD1d0 BWF1 mice. Spleen cells were enumerated in 12-week-old female BWF1 mice (n = 9 CD1d0 and n = 5 CD1d+). Values are the mean ± SEM. Results are from a representative experiment of 2 independent experiments performed using female mice. * = P < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney U test in a and Student’s t-test in b and c.

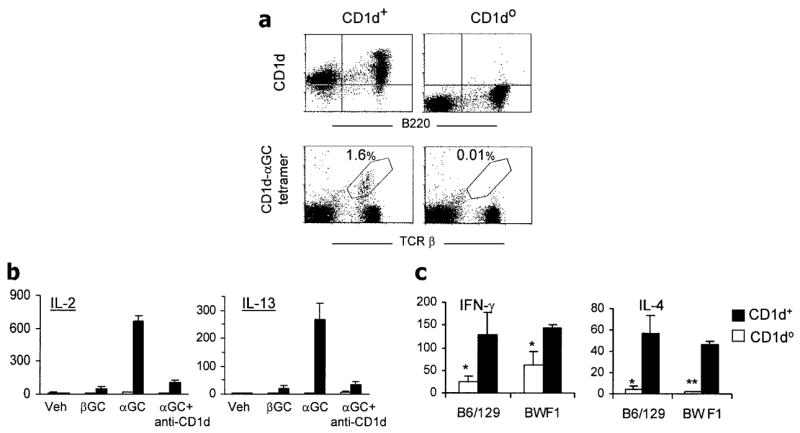

Effect of CD1d deficiency on iNKT cell responses in BWF1 mice

To ensure that CD1d-reactive iNKT cell responses are attenuated in CD1d0 BWF1 mice, as previously reported in normal strains (45), we determined iNKT cell numbers and functions in CD1d0 BWF1 mice (Figure 3). As expected, CD1d expression and αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer–positive T cells (i.e., iNKT cells) were absent in CD1d0 BWF1 mice (Figure 3a). The CD1d-specific iNKT cell responses, as measured by cytokine production in response to αGalCer, were also absent in CD1d0 lupus mice (Figure 3b). In CD1d+ BWF1 mouse spleen cells, αGalCer stimulated the release of large amounts of type 1 (IFNγ, IL-2) and type 2 (IL-4, IL-13) cytokines, whereas neither a control glycolipid (βGalCer) nor the vehicle in which αGalCer was dissolved induced significant cytokine responses. Levels of active TGFβ1, IL-10, and IL-12 were low to undetectable in αGalCer-stimulated spleen cell cultures in both wild-type and CD1d0 BWF1 mice. Addition of an anti-CD1d mAb to the cultures inhibited the αGalCer-stimulated cytokine responses in wild-type mice. Thus, αGalCer-induced cytokine responses are mediated entirely by CD1d1 molecules in BWF1 mice and such responses are absent in the CD1d10 lupus-prone mice, as reported in normal mouse strains (45).

Figure 3.

Reduced invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cell cytokine responses in CD1d0 (NZB × NZW)F1 (BWF1) mice. CD1d0 and CD1d+ BWF1 littermates (3–4 months old) were analyzed for iNKT cells and their cytokine responses. a, Spleen cells were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled anti-mouse CD1d and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled anti-mouse B220 monoclonal antibody (mAb) or with PE-labeled anti-mouse α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer)–loaded CD1d tetramer (CD1d-αGC tetramer) and FITC-labeled anti-mouse T cell receptor β (TCRβ) mAb in the presence of anti-CD16/32 (2.4G2). Results are representative of 3 experiments, each with 3 mice per group. b, Effect of in vitro stimulation of spleen cells with the CD1d ligand αGalCer on cytokine responses. Spleen cells (n = 5 mice per group) were cultured with the vehicle (Veh; 0.025% polysorbate-20 in phosphate buffered saline [PBS]) in which the glycolipids were dissolved or with 50 ng/ml of synthetic βGalCer (βGC) or αGalCer (αGC). Anti-CD1d mAb 1B1 (10 μg/ml) was added to some cultures containing αGalCer. Supernatants were collected at 48 hours and tested for interleukin-2 (IL-2) and IL-13. Addition of αGalCer, but not control glycolipid βGalCer or vehicle alone, induced strong cytokine responses in CD1d+ BWF1 mice; such responses were absent in cultures containing anti-CD1d mAb or spleen cells from CD1d0 BWF1 mice. Values are the mean and SEM pg/ml. c, Responses of iNKT cells, as determined by rapid cytokine production by spleen cells upon brief in vivo stimulation with anti-CD3. Mice (n = 3–5 per group) were injected intravenously with 1 μg of anti-CD3 mAb and were euthanized 90 minutes later. Suspensions of single spleen cells were cultured (5 × 106/ml) for 2 hours, and supernatants were tested for IL-4 and interferon-γ (IFNγ). Values are the mean and SEM pg/ml. No cytokines were detected in 2-hour culture supernatants from the control PBS-injected mice (data not shown). Results are from a representative experiment of 2–4 independent experiments performed. Values are the mean and SEM pg/ml. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01 versus CD1d+ littermates, by Student’s t-test.

Invariant NKT cells promptly produce cytokines in response to in vivo challenge with anti-CD3 (13). To examine the effect of CD1d deficiency on such iNKT cell responses in lupus-prone mice, CD1d0 and CD1d+ BWF1 mice were injected with an anti-CD3 mAb and, after 90 minutes, were euthanized. Their spleen cells were cultured for 2 hours (Figure 3c). CD1d0 and CD1d+ mice with the normal, non–lupus-prone background (B6/129) were used as controls. Consistent with previous reports of the findings in normal mouse strains (45), the rapid production of IL-4 was dramatically lower in CD1d0 BWF1 mice than in their wild-type littermates. Thus, the characteristic early IL-4 response by iNKT cells was decreased in CD1d0 BWF1 mice. The effect of CD1d deficiency on IFNγ production, however, was less profound in BWF1 mice than in normal B6/129 mice (Figure 3c).

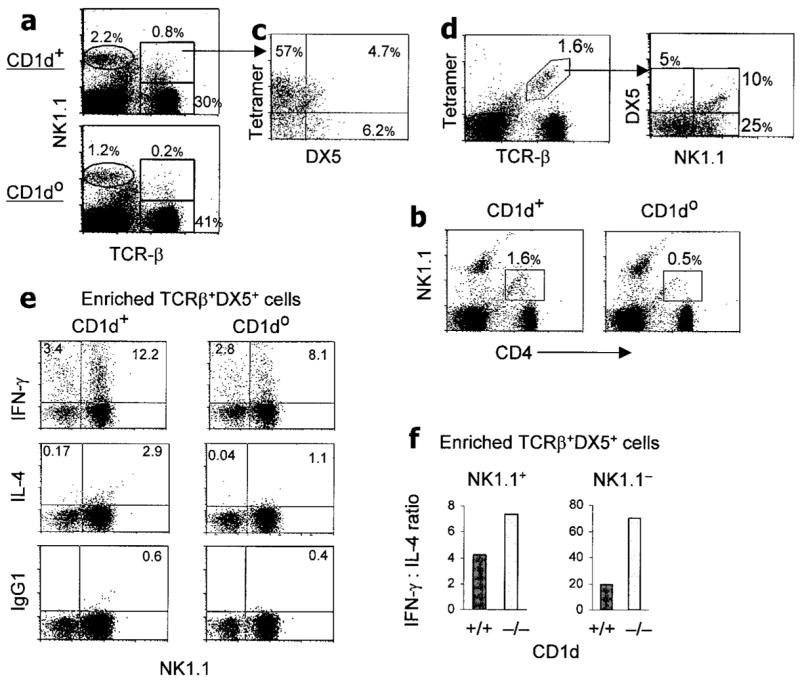

Retention of significant numbers of IFNγ-secreting NKT-like cells (CD1d-independent TCRβ+,NK1.1+ and/or DX5+ cells) in CD1d0 BWF1 mice

To begin to understand the mechanisms of disease exacerbation in CD1d0 mice, we first analyzed the phenotype of T cells in these mice (Figure 4). Although the levels were significantly reduced, CD1d0 mice had considerable numbers of TCRβ+,NK1.1+ cells (Figure 4a). The mean ± SEM percentages of CD4+,NK1.1+ cells were 0.99 ± 0.08% and 1.58 ± 0.22% in CD1d0 and CD1d+ BWF1 mice, respectively (n = 9 per group; P < 0.05) (Figure 4b). Only ~60% of TCRβ+,NK1.1+ cells in wild-type BWF1 mice were iNKT cells (αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer positive) (Figure 4c). Intriguingly, only ~10% of TCRβ+,NK1.1+ cells in wild-type mice expressed the pan-NK marker DX5 (Figure 4c), and <50% of TCRβ+,DX5+ cells expressed NK1.1 (data not shown). Further analysis showed that among all iNKT cells (TCRβ+, αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer positive) in BWF1 mice, only 40% expressed any NK marker (Figure 4d). In fact, only 15% of iNKT cells expressed the pan-NK marker DX5. Thus, the majority of TCRβ+,DX5+ cells (85%) in wild-type BWF1 mice will represent CD1d-restricted variant or type II NKT or CD1d-independent NKT-like cells. In CD1d0 mice, all TCRβ+,DX5+ cells will represent CD1d-independent NKT-like cells.

Figure 4.

Persistence of significant numbers of IFNγ-producing TCRβ+,DX5+ cells (i.e., CD1d-independent NKT cells) in CD1d0 BWF1 mice. Spleen cells were stained for the indicated markers, and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis was performed, gating on lymphocytes according to their forward and side light-scatter properties. Values shown in the plots are the percentages of cells in the respective gates. Representative FACS plots (n = 4–7 mice per group) are shown. a, Percentages of conventional T cells (TCRβ+,NK1.1− cells), NK cells (TCRβ −,NK1.1+ cells), and TCRβ+,NK1.1+ cells in 4-month-old CD1d0 and CD1d+ mice. b, Percentages of CD4+,NK1.1+ cells in 3-month-old CD1d0 and CD1d+ mice. c, The gated TCRβ+,NK1.1+ cells from CD1d+ BWF1 mice in a were further analyzed for cells positive for αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer and for DX5 expression. About 60% of TCRβ+,NK1.1+ cells were found to be iNKT cells. d, Splenic lymphocytes from 4-month-old CD1d+ BWF1 mice were analyzed for iNKT cells (TCRβ+, αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer positive), which were further analyzed for DX5 and NK1.1 expression. e and f, Spleen cells pooled from 3-month-old CD1d0 and CD1d+ BWF1 mice (n = 10 per group) were processed to enrich TCRα/β+,DX5+ cells. Isolated cells (1.5 × 106) were stimulated overnight with plate-bound anti-CD3 in 24-well plates, followed by incubation with monensin (3 μM) for an additional 4 hours. Cells were collected and stained for FITC-conjugated anti-mouse NK1.1, followed by intracellular cytokine staining. Percentages of IFNγ- and IL-4–producing cells were determined by flow cytometry (e). Cytokine responses in NK1.1+ and NK1.1− populations among the enriched DX5+,TCRα/β + cells are shown as the IFNγ:IL-4 ratio (f). Values are the mean. Results are from a representative experiment of 4 independent experiments performed. See Figure 3 for other definitions.

To examine the phenotype of such NKT-like cells in lupus-prone mice, we isolated TCRβ+,DX5+ cells from spleen cells pooled from CD1d0 or CD1d+ BWF1 mice (n = 10 per group). Approximately 2.5 × 105 or 1.5 × 105 TCRβ+,DX5+ cells that accounted for ~0.6% or ~0.3% of spleen cells were isolated from each CD1d+ or CD1d0 BWF1 mouse, respectively. These cells were stimulated overnight with plate-bound anti-CD3, and the numbers of cytokine-producing cells were enumerated by intracellular cytokine staining (Figure 4e). Among enriched TCRβ+,DX5+ cells, 15.6% and 10.9% cells produced IFNγ and 3.07% and 1.14% cells from CD1d+ and CD1d0 BWF1 mice, respectively, produced IL-4. The mean ratios of IFNγ-producing to IL-4–producing TCRβ+,NK1.1+ cells from 2 independent experiments were higher in CD1d0 BWF1 mice (8:1) than in their CD1d+ BWF1 littermates (4:1) (Figure 4f). This finding suggests that whereas IL-4–producing TCRβ+,NK1.1+ cells are mostly CD1d-restricted, TCRβ+,NK1.1+ cells that develop in the absence of CD1d may predominantly produce IFNγ. The latter (NKT-like) cells are relatively increased in CD1d0 mice as compared with their wild-type BWF1 littermates. Future studies will determine whether IL-4–secreting TCRβ+,NK1.1+ cells from wild-type BWF1 mice inhibit autoimmunity in CD1d0 BWF1 mice.

Reduced type 2, but enhanced type 1, cytokine responses of in vitro Con A–stimulated spleen cells from CD1d0 BWF1 mice

In humans and mice with SLE, development of autoimmunity is accompanied by aberrant secretion of multiple cytokines, including IFNγ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and TGFγ (1,43,46,49). Identifying the cell types and delineating the mechanisms that contribute to such cytokine abnormalities would facilitate understanding of the role of CD1d in the pathogenesis of SLE. We therefore investigated whether CD1d deficiency affects conventional T cell responses in BWF1 mice.

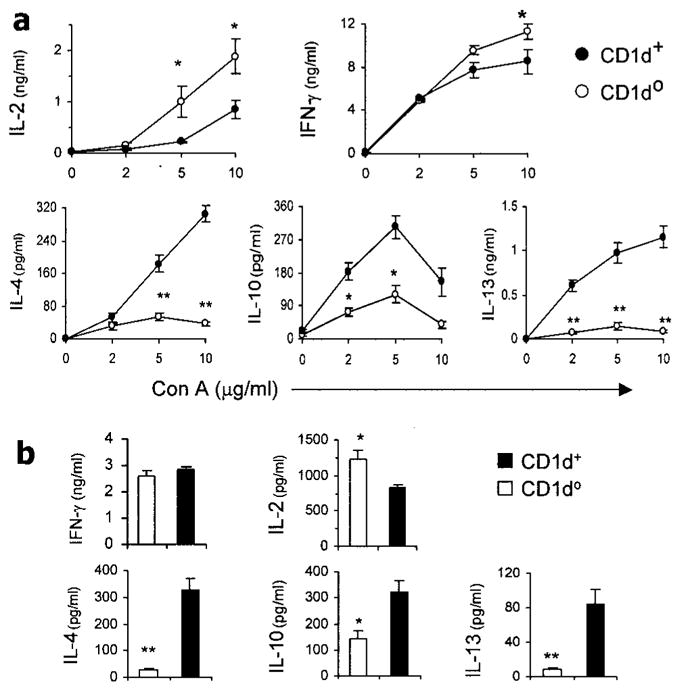

Spleen cells from 3-month-old CD1d0 and CD1d+ BWF1 littermates were cultured in the absence or presence of Con A (2–10 μg/ml) for 48 hours. Supernatants were tested for cytokines by ELISA (Figure 5a). All type 2 cytokines tested (IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13) were significantly decreased in Con A–stimulated cultures from CD1d0 mice as compared with wild-type mice. Among type 1 cytokines, IL-2 was significantly increased in CD1d0 mice, and IFNγ levels were similar in CD1d0 and CD1d+ mice at low concentrations of Con A (2–5 μg/ml). At high concentrations of Con A (10 μg/ml) however, IFNγ was increased in CD1d0 mice as compared with their CD1d+ littermates. Levels of active TGFβ1 and IL-12 were low to undetectable in all cultures (data not shown). Thus, T cell stimulation with Con A revealed that the potential for type 1 cytokine production is elevated in CD1d0 BWF1 mice.

Figure 5.

Conventional T cell cytokine responses in CD1d0 (NZB × NZW)F1 (BWF1) mice. Whole spleen cells or purified splenic T cells from 3-month-old BWF1 mice were assayed for Th1 and Th2 cytokines. a, Spleen cells (1.5 × 106 per ml) from CD1d0 or CD1d+ BWF1 mice (n = 5 per group) were cultured for 48 hours with or without concanavalin A (Con A), and supernatants were tested for interleukin-2 (IL-2), interferon-γ (IFNγ), IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13. b, Purified splenic T cells pooled from CD1d0 or CD1d+ BWF1 mice (n = 10 per group) were stimulated for 16 hours with plate-bound anti-mouse CD3 antibody, and supernatants were tested for IFNγ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13. Values are the mean and SEM. Results are from a representative experiment of 3 experiments performed. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01, by Student’s t-test.

Reduced type 2, but unchanged type 1, cytokine responses of in vitro anti-CD3–stimulated T cells from CD1d0 BWF1 mice

To further investigate cytokine responses of conventional T cells in CD1d0 BWF1 mice, we purified TCR+,NK1.1– cells from the spleens of CD1d0 and wild-type BWF1 mice and stimulated them with plate-bound anti-CD3 for 16 hours or longer. As shown in Figure 5b, levels of IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 were significantly reduced in CD1d0 mice as compared with their wild-type littermates. IFNγ levels were similar in the 2 groups, and IL-2 was increased in CD1d0 as compared with CD1d+ mice. These observations suggest that CD1d influences cytokine production by conventional T cells, resulting in a pattern of reduced production of type 2 cytokines in CD1d0 BWF1 mice.

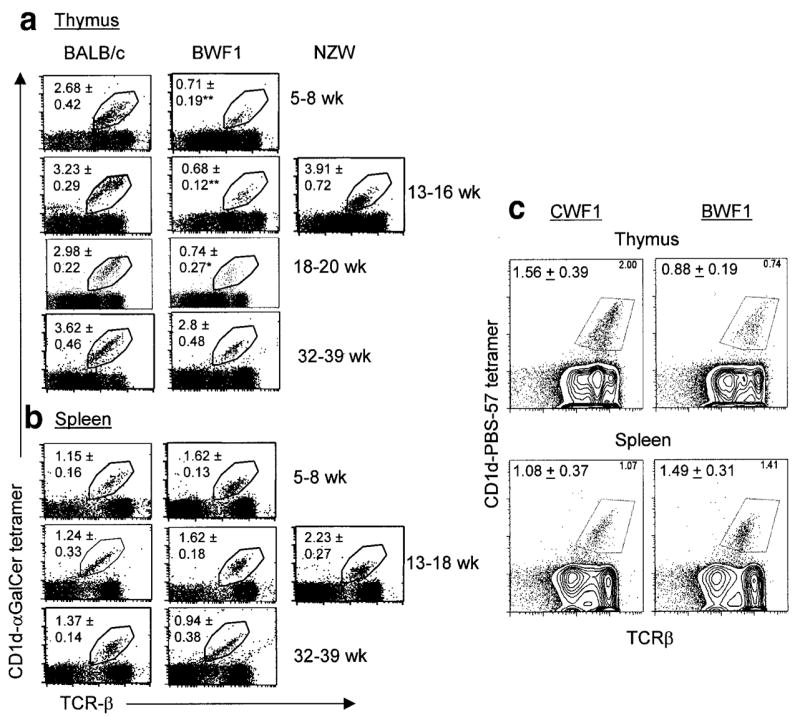

Percentages and total numbers of iNKT cells in the thymus and spleen of wild-type BWF1 mice

The above data suggest a protective role of CD1d in the development of lupus nephritis in the BWF1 mouse model. The Vα14–Jα18 TCR-expressing cells that dominate the CD1d-reactive T cell repertoire (50) can be recognized by staining with αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer (51). To monitor the frequency of these cells at different stages of lupus disease development, thymocytes from BWF1 mice before (5–8 weeks of age), during (13–18 weeks of age), and after (>25 weeks of age) the onset of disease and from age-matched healthy BALB/c or NZW mice were stained with αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer.

As shown in Figure 6a and Table 1, the percentages and total numbers of iNKT cells were significantly lower in the thymus of BWF1 mice at the preclinical stage (5–8 weeks old) than in age-matched BALB/c mice. Percentages, but not total numbers, of thymic iNKT cells were also reduced in BWF1 mice at the early disease development stages (13–20 weeks old) of lupus than in age-matched BALB/c or NZW mice. Thymic iNKT cell numbers were not significantly different, however, between diseased BWF1 mice (32–39 weeks old) and age-matched BALB/c mice. The percentages and total numbers of iNKT cells in the spleen were also not significantly different between BWF1 and BALB/c or NZW mice at all ages tested (Figure 6b and Table 1). Similar findings were obtained when iNKT cells were compared between BWF1 mice and class II MHC (H-2dz)–identical CWF1 mice (Figure 6c). Thus, iNKT cell numbers are reduced in the thymus of BWF1 mice at early stages of disease development.

Figure 6.

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells in the thymus and spleen of (NZB × NZW)F1 (BWF1) and control mice. a, Thymocytes and b, splenocytes were prepared from BWF1, BALB/c, and NZW mice of different ages (n = 5–12 per group) and then stained for iNKT cells by α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer)–loaded CD1d tetramer and T cell receptor β (TCRβ). Values shown in the plots are the mean ± SEM percentages. Results are representative of at least 5 independent experiments. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01 versus control mice, by Student’s t-test. See Table 1 for total numbers of thymic and splenic iNKT cells. c, Thymocytes and splenocytes from 8–14-week-old BWF1 mice or from the class II major histocompatibility complex–identical strain (BALB/c × NZW)F1 (CWF1) were stained with allophycocyanin-labeled anti-TCRβ and phycoerythrin-labeled CD1d tetramer loaded with PBS-57, an analog of αGalCer. Percentages of TCRβ+ tetramer (iNKT) cells are shown at the upper right of the plots; mean ± SEM percentages of iNKT cells from 2 experiments (n = 2–4 mice per group per experiment) at the upper left.

Table 1.

Total numbers of CD1d/α-galactosylceramide tetramer–positive cells in the thymus and spleen of BALB/c and (NZB × NZW)F1 mice of various age groups*

| Thymus | Spleen | |

|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | ||

| 5–8 weeks old | 124.6 ± 7.9 | 52.8 ± 6.4 |

| 13–16 weeks old | 58.5 ± 6.9 | 52.1 ± 7.6 |

| 32–39 weeks old | 32.9 ± 3.7 | 69.7 ± 8.2 |

| (NZB × NZW)F1 | ||

| 5–8 weeks old | 54.2 ± 7.3† | 81.3 ± 9.4 |

| 13–16 weeks old | 40.4 ± 8.6 | 121.4 ± 17.8 |

| 32–39 weeks old | 24.3 ± 18.2 | 118.4 ± 21.6 |

Cells were obtained from (NZB × NZW)F1 mice before (5–8 weeks of age), during (13–18 weeks of age), and after (>25 weeks of age) the onset of disease and from age-matched healthy BALB/c mice. Values are the mean ± SEM cell numbers ×104.

P < 0.01 versus BALB/c mice of the same age group, by Student’s t-test.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that the proportions and numbers of iNKT cells are reduced in the thymus of BWF1 mice at early stages of disease development. In addition, CD1d deficiency since birth exacerbates lupus nephritis in BWF1 mice, which is associated with an increase in IFNγ-producing CD1d-independent NKT-like (TCRβ+,NK1.1+ and/or DX5+) cells and a reduced production of type 2 cytokines upon polyclonal stimulation of T cells.

Several studies have enumerated iNKT cells, as defined by staining with αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer, in lymphoid organs of animal models of lupus (Table 2). Consistent with data in this article, showing reduced iNKT cells in the thymus of young BWF1 mice as compared with BALB/c and NZW mice, thymic iNKT cells have been found to be reduced in all lupus-prone strains examined thus far, including MRL-lpr, MRL-Fas, and pristane-injected BALB/c mice (28,29). The study by Forestier et al (30), which reported expansion of iNKT cells in various organs with increasing age in BWF1 mice, also showed a lower proportion of thymic iNKT cells in 4–6-week-old BWF1 mice than in control B6 mice (0.2% versus 0.5%, respectively).

Table 2.

Prevalence of iNKT (αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer–positive) cells in animal models of systemic lupus erythematosus*

| Organ analyzed | Animal strain

|

Author, year (ref.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | Prevalence of iNKT cells | ||

| Thymus | Pristane-injected BALB/c | PBS-injected BALB/c | Pristane-injected < PBS-injected (P < 0.01 for percentage; P < 0.05 for total number) | Yang et al, 2003 (28) |

| Thymus | MRL-lpr and MRL-Fas | C3H (MHCII-matched) and BALB/c | MRL-lpr = MRL-Fas < BALB/c or C3H (P < 0.05 to P < 0.001) | Yang et al, 2003 (29) |

| Thymus | BWF1 | B6 | BWF1 (0.2%) < B6 (0.5%) in 4–6-week-old mice; percentage increased with increasing age in BWF1 mice (0.6%, 1.5%, and 2.5% at ages 4, 14, and 34 weeks, respectively); for total number, BWF1 > B6 (P < 0.001) at age 30 weeks | Forestier et al, 2005 (30) |

| Thymus | BWF1 | BALB/c, NZW, and CWF1 (MHCII-matched) | BWF1 < BALB/c and NZW at preclinical and early clinical stages (ages 5–20 weeks); BWF1 = BALB/c at advanced clinical stage (ages >32 weeks) | Present study |

| Spleen | MRL-lpr | MRL-Fas+/+, C3H (MHCII-matched), and BALB/c | MRL-lpr < MRL-Fas < C3H or BALB/c (P < 0.05 to P < 0.001) | Yang et al, 2003 (29) |

| Spleen | Pristane-injected BALB/c | PBS-injected BALB/c | Pristane-injected = PBS-injected (percentage and total number) | Yang et al, 2003 (28) |

| Spleen | BWF1 | B6 | No difference (8–12-week-old mice): absolute number similar; percentage increased in BWF1 mice (statistical significance not provided) | Zeng et al, 2003 (31) |

| Spleen | BWF1 | B6 | BWF1 = B6 at ages 4–6 weeks (percentage and total number); BWF1 > B6 at ages 10–18 weeks (P < 0.05 for percentage and total number); at age 30 weeks, percentage reduced, but total number increased, in BWF1 versus B6 (P < 0.001 for total number) | Forestier et al, 2005 (30) |

| Spleen | BWF1 | BALB/c, NZW, and CWF1 (MHCII-matched) | No significant difference in percentage or total number at all ages tested (5–8 weeks, 13–16 weeks, and 32–39 weeks) | Present study |

| Liver | MRL-lpr and MRL-Fas | C3H (MHCII-matched) and BALB/c | MRL-lpr = MRL-Fas < C3H < BALB/c (P < 0.05 to P < 0.001) | Yang et al, 2003 (29) |

| Liver | BWF1 | B6 | BWF1 = B6 in 4-week-old and 14-week-old mice; BWF1 > B6 in 30-week-old mice | Forestier et al, 2005 (30) |

| Kidney | BWF1 | B6 | BWF1 = B6 in 4-week-old mice; BWF1 > B6 at ages 14 weeks and 30 weeks | Forestier et al, 2005 (30) |

| Blood | BWF1 | B6 | BWF1 > B6 in 4–6-week-old mice (P < 0.05) | Forestier et al, 2005 (30) |

| Lymphnode | MRL-lpr and MRL-Fas | C3H (MHCII-matched) and BALB/c | MRL-lpr = MRL-Fas = C3H < BALB/c | Yang et al, 2003 (29) |

iNKT = invariant natural killer T; αGalCer = α-galactosylceramide; PBS = phosphate buffered saline; MRL-lpr = MRL-Faslpr/lpr; MRL-Fas = MRL-Fas+/+; C3H = C3H.HeJ; MHCII = class II major histocompatibility complex; BWF1 = (NZB × NZW)F1; B6 = C57BL/6; CWF1 = (BALB/c × NZW)F1.

In the spleen, however, we did not find any change in the numbers of iNKT cells in BWF1 mice. Similar data on splenic iNKT cells have been reported by Zeng et al (31) in BWF1 mice and by our group (28) in the hydrocarbon oil–induced model of lupus. Zeng et al (31) found no significant differences in the percentages (mean 4.8 ± 0.9% versus 3.5 ± 0.5% of TCRβ + cells) or absolute numbers (mean 989 ± 88 × 103 versus 923 ± 72 × 103) of tetramer-positive cells in the spleen of BWF1 and B6 mice. In contrast to these 3 studies in BWF1 and hydrocarbon oil models, Forestier et al (30) found a significant increase in the percentages and absolute numbers of iNKT cells in the spleen of BWF1 mice at 10–18 weeks of age. At later ages (25–35 weeks), when BWF1 mice have splenomegaly and increased absolute numbers of iNKT cells, there was no proportionate increase in iNKT cells as compared with B6 mice. Thus, too few iNKT cells may be left to interact with too many other cells in the lymphoid organs of these mice. Nevertheless, the Forestier study reported an accumulation of iNKT cells in the liver and kidneys of aged BWF1 mice (30). In contrast, MRL-lpr and MRL-Fas+/+ mice have a marked reduction in iNKT cells in the thymus, spleen, liver, and lymph nodes as compared with MHC-matched C3H mice (29).

Overall, of the 5 studies that have investigated iNKT cells with the use of tetramers, 4 of them (refs. 28, 29, 31 and the current study) have found either a reduction or no significant difference in iNKT cells in the lymphoid organs of lupus-prone mice. The fifth study, however, found a significant accumulation of these cells with age in various lymphoid organs (30). The reason for this discrepancy remains unclear. Environmental factors, including diet, and the use of different control strains (an MHC-unrelated control strain B6 in the Forestier study [30] and the Zeng study [31] versus MHC-matched strains, including BALB/c, NZW, and CWF1 mice in the present study) might partly account for some of the differences. All studies to date on iNKT cells in lupus-prone mice are summarized in Table 2. In summary, a reduction in thymic iNKT cells appears to be a common feature of lupus-prone mice, at least during the first 6 weeks of life. A link between lupus susceptibility and reduced thymic iNKT cells is supported by a study showing that genetic control of thymic iNKT cell numbers maps strongly to the robust lupus susceptibility locus Bana3/Sle1/Nba2/Lbw7 region of chromosome 1 (52).

Such iNKT cell changes must be relevant to lupus disease development, since germline deletion of CD1d, which causes a marked deficiency of iNKT cells (45), also resulted in exacerbation of lupus nephritis in a genetically autoimmune–susceptible model (Figure 1) as well as in a hydrocarbon oil–induced model in otherwise normal BALB/c mice (28). Although we used N10–N12 backcrossed CD1d0 BWF1 mice that are expected to carry ≤0.1% genes from the 129/B6 CD1d0 founders, there remains the possibility that our results reflect the introduction or removal of a linked gene(s) during the backcross of the mutated CD1d 129 locus onto the NZB and NZW backgrounds. Genotype analyses of our congenic strains using simple sequence repeat markers, however, did not suggest a replacement with donor genes at any of the loci tested (data not shown). Moreover, similar data have been obtained using different lupus models, namely CD1d0 BWF1 (Figure 1) and CD1d0 pristane-injected BALB/c mice (28), which is evidence against the possibility that other lupus-susceptibility genes are responsible for our observations.

Consistent with our data, a previous study has shown that in vitro coculture with NK1.1+,CD3+ cells or their in vivo transfer also reduces anti-DNA antibody production in the B6-lpr/lpr model (53), which further supports the regulatory role of NKT cells in antibody-mediated autoimmunity. However, treatment of BWF1 mice with an anti-CD1d mAb has been reported to delay the onset of lupus (42). We and other investigators have also failed to detect a significant effect of CD1d deficiency on the development of lupus nephritis in MRL-lpr/lpr mice (54,55). Instead, lupus dermatitis is exacerbated by β2m (54) and CD1d deficiency (55) in MRL-lpr/lpr mice.

Thus, different regulatory mechanisms may account for the different outcomes of iNKT cell manipulations in different models or in different stages of disease. Indeed, treatment of BWF1 mice with αGalCer, which activates iNKT cells, delays the onset of renal disease if given in the early, preclinical stages of auto-immunity, but it has no effect on the disease course when given during the late stages of disease (Yang J-Q, et al: unpublished observations). Treatment with αGalCer during the late stages of disease can even exacerbate nephritis and enhance IgM anti-DNA antibody levels (31). Thus, iNKT cells may be unable to exert their regulatory effects in the presence of full-blown autoimmune disease, or a cytokine storm triggered by activated iNKT cells might even further stimulate the already activated autoreactive T cells in certain conditions. Additionally, iNKT cells may exert different effects during different manifestations of disease. For example, while iNKT cells may protect against lupus nephritis, they might exacerbate lupus-associated atherosclerosis (37). Further studies are required to clarify the mechanism of the disparate effects of iNKT cells during different stages or aspects of disease. Nevertheless, several lines of evidence indicate a potent suppressive role of CD1d-reactive iNKT cells in the early stages of autoimmune diseases.

The mechanisms by which CD1d-reactive T cells contribute to protection against the development of autoimmunity are unclear. We show that whereas IFNγ production was unaffected or was increased in the CD1d0 BWF1 mice, production of type 2 cytokines was decreased upon in vitro stimulation of spleen cells with Con A or stimulation of purified T cells with anti-CD3 antibody (Figure 5). Conversely, iNKT cell activation by treatment of lupus-prone MRL-lpr mice with αGalCer has been shown to increase serum levels of IgE (29), which is a hallmark of the Th2 response. Although which cytokines play vital roles in the development and progression of SLE remains largely unresolved, several lines of evidence suggest that increased or stable T cell IFNγ production, along with reduced IL-4 production during disease initiation, could contribute to disease exacerbation. For example, IL-4 deficiency or its in vivo neutralization increases antichromatin or anti-DNA antibody production in animal models of lupus (46,56), and transgenic overexpression of IL-4 can protect against the development of a lupus-like syndrome (57).

In addition to modulation of cytokine effects, CD1d deficiency and iNKT cells can modulate the functions of other immune cell types (24,25). We have also recently found that the addition of an iNKT cell ligand to spleen cells from the wild-type animals, but not to spleen cells from CD1d-deficient mice, can specifically suppress IgG autoantibody production, while activating other B cell functions (58,59). However, the effects of iNKT cells on anti-DNA antibody production can only partly explain the disease-exacerbating effects of CD1d deficiency, since CD1d0 BWF1 mice had a more profound increase in renal disease than in anti-DNA antibody levels. One possible explanation for this finding may be the development of other autoantibodies in CD1d0 mice, which might perpetuate organ damage. For example, we have found that CD1d deficiency results in the development of anti–ribosomal P and anti-OJ antibodies, which are generally not induced in pristane-injected wild-type BALB/c mice (28). Another possible explanation may be the activation of autoreactive T cells or other immune cells or increases in cytokines and chemokines, which may directly perpetuate organ damage. Studies are under way to investigate the relative contribution of cytokine or other immune alterations induced by CD1d deficiency or iNKT cell activation on the development and progression of lupus.

The mechanisms by which CD1d deficiency or iNKT cell activation may influence type 1 versus type 2 cytokine production remain unclear. In this regard, NK1.1+,TCRα/β + cells comprise a heterogeneous population of cells (29). Although most of these cells are CD1d-restricted, some NK1.1+,TCRα/β + cells are restricted by other MHC molecules (60,61). The restriction elements of these CD1d-nonrestricted NKT-like cells are not clearly defined; however, recent reports have implicated roles for the TCR α-chain connecting peptide domain or a fetal class I molecule in their positive selection or regulation, respectively (60,61). Expansions or phenotype alterations of such NKT-like cells might contribute to enhanced autoimmunity in CD1d0 autoimmune-prone mice. In fact, the ratio of IFNγ-producing cells to IL-4–producing cells was higher among NKT-like cells in CD1d0 BWF1 mice (8:1) as compared with CD1d+ BWF1 mice (4:1), which have both “classic” iNKT cells and NKT-like cells (Figure 4). Thus, CD1d-independent NKT-like cells may be responsible in part for the increased IFNγ production in CD1d0 BWF1 mice. Similar inferences were made from studies in β2m/MHC class II–double-knockout mice, which indicated a major role of CD1d-restricted CD4+ T cells in IL-4 production and of CD1d-independent T cells in IFNγ production upon anti-CD3 stimulation (62). Consistent with our findings, a recent study showed that TGFβ receptor II deficiency in T cells results in reduced iNKT cells, along with increased numbers of NKT-like cells that mediate fatal multisystem autoimmune disease (63).

In summary, we have generated several lines of evidence in this and other studies (28,29,38,55,59) suggesting a protective role of iNKT cells in lupus, at least during the early stages of development. However, iNKT cell activation can also aggravate lupus, such as during the late stages of disease (31). One might argue that such preventive therapy is not worth pursuing, since the patients do not present during the early preclinical stages. However, extrapolating our animal data to humans with SLE, αGalCer treatment given to patients when they have achieved remission from other therapies would prevent future relapses of disease. A clear understanding of these roles may have implications for the development of iNKT cell–based therapies for the treatment of complex lupus disease. Furthermore, ongoing investigations might find other glycolipid agents that confer protection at all stages of lupus disease. The idea that iNKT cells may suppress lupus disease is particularly appealing, because humans with SLE have reduced numbers of circulating invariant TCR Vα24–Jα18–positive T cells (41). In fact, treatments such as cortico-steroids that suppress disease activity in SLE patients restore the numbers of circulating Vα24–Jα18 iNKT cells (41). Clearly, a detailed analysis of the different roles of iNKT cells in different stages and manifestations of lupus in patients is warranted in order to utilize the full potential of these cells in therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Deijanira Albuquerque, Tam Bui, Seokmann Hong, and Jonathan Jacinto for technical assistance and Laurence Morel for suggestions on genotyping the congenic strains. Generation of the CD1d tetramer loaded with αGalCer that was used in this study was supported by NIH grant AI-042284 to Dr. Sebastian Joyce (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN). The αGalCer was kindly provided by Kirin Brewery, Ltd. (Gunma, Japan). The phycoerythrin-labeled CD1d tetramer loaded with PBS-57, an analog of αGalCer, was kindly provided by the NIH Tetramer Facility at Emory University (Atlanta, GA).

Dr. Van Kaer’s work was supported by NIH grant HL-68744. Dr. Singh’s work was supported by NIH grants AR-47322 and AR-50797.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Singh had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study design. Yang, Van Kaer, Singh.

Acquisition of data. Yang, Wen, Liu, Folayan, Dong, Zhou, Singh.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Yang, Wen, Van Kaer, Singh.

Manuscript preparation. Yang, Van Kaer, Singh.

Statistical analysis. Yang, Singh.

References

- 1.Singh RR. SLE: translating lessons from model systems to human disease. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:572–9. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shivakumar S, Tsokos GC, Datta SK. T cell receptor α/β expressing double-negative (CD4−/−) and CD4+ T helper cells in humans augment the production of pathogenic anti-DNA autoantibodies associated with lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 1989;143:103–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh RR, Kumar V, Ebling FM, Southwood S, Sette A, Sercarz EE, et al. T cell determinants from autoantibodies to DNA can upregulate autoimmunity in murine systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2017–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peng SL, Madaio MP, Hayday AC, Craft J. Propagation and regulation of systemic autoimmunity by γδ T cells. J Immunol. 1996;157:5689–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh RR, Ebling FM, Albuquerque DA, Saxena V, Kumar V, Giannini EH, et al. Induction of autoantibody production is limited in nonautoimmune mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:587–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan GC, Singh RR. Vaccination with minigenes encoding VH-derived major histocompatibility complex class I-binding epitopes activates cytotoxic T cells that ablate autoantibody-producing B cells and inhibit lupus. J Exp Med. 2002;196:731–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowlkes BJ, Kruisbeek AM, Ton-That H, Weston MA, Coligan JE, Schwartz RH, et al. A novel population of T-cell receptor αβ-bearing thymocytes which predominantly expresses a single Vβ gene family. Nature. 1987;329:251–4. doi: 10.1038/329251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yankelevich B, Knobloch C, Nowicki M, Dennert G. A novel cell type responsible for marrow graft rejection in mice: T cells with NK phenotype cause acute rejection of marrow grafts. J Immunol. 1989;142:3423–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sykes M. Unusual T cell populations in adult murine bone marrow: prevalence of CD3+CD4−CD8− and αβ TCR+NK1.1+ cells. J Immunol. 1990;145:3209–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballas ZK, Rasmussen W. NK1.1+ thymocytes: adult murine CD4−, CD8− thymocytes contain an NK1.1+, CD3+, CD5hi, CD44hi, TCR–Vβ8+ subset. J Immunol. 1990;145:1039–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bendelac A, Schwartz RH. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells acquire specific lymphokine secretion potentials during thymic maturation. Nature. 1991;353:68–71. doi: 10.1038/353068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arase H, Arase N, Nakagawa K, Good RA, Onoe K. NK1.1+ CD4+ CD8− thymocytes with specific lymphokine secretion. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:307–10. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimoto T, Paul WE. CD4pos, NK1.1pos T cells promptly produce interleukin 4 in response to in vivo challenge with anti-CD3. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1285–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arase H, Arase N, Ogasawara K, Good RA, Onoe K. An NK1.1+ CD4+8− single-positive thymocyte subpopulation that expresses a highly skewed T-cell antigen receptor Vβ family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:6506–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lantz O, Bendelac A. An invariant T cell receptor α chain is used by a unique subset of major histocompatibility complex class I–specific CD4+ and CD4−8− T cells in mice and humans. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1097–106. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makino Y, Kanno R, Ito T, Higashino K, Taniguchi M. Predominant expression of invariant Vα14+ TCR α chain in NK1.1+ T cell populations. Int Immunol. 1995;7:1157–61. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.7.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koseki H, Imai K, Ichikawa T, Hayata I, Taniguchi M. Predominant use of a particular α-chain in suppressor T cell hybridomas specific for keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Int Immunol. 1989;1:557–64. doi: 10.1093/intimm/1.6.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porcelli S, Yockey CE, Brenner MB, Balk SP. Analysis of T cell antigen receptor (TCR) expression by human peripheral blood CD4−8−α/β T cells demonstrates preferential use of several Vβ genes and an invariant TCR α chain. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bendelac A, Lantz O, Quimby ME, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR, Brutkiewicz RR. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+ T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;268:863–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porcelli SA, Modlin RL. The CD1 system: antigen-presenting molecules for T cell recognition of lipids and glycolipids. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:297–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brossay L, Jullien D, Cardell S, Sydora BC, Burdin N, Modlin RL, et al. Mouse CD1 is mainly expressed on hemopoietic-derived cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:1216–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of Vα14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–9. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bendelac A, Rivera MN, Park SH, Roark JH. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells: development, specificity, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:535–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taniguchi M, Harada M, Kojo S, Nakayama T, Wakao H. The regulatory role of Vα14 NKT cells in innate and acquired immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:483–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kronenberg M. Toward an understanding of NKT cell biology: progress and paradoxes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:877–900. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godfrey DI, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Van Kaer L. NKT cells: what’s in a name? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:231–7. doi: 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Behar SM, Cardell S. Diverse CD1d-restricted T cells: diverse phenotypes, and diverse functions. Semin Immunol. 2000;12:551–60. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang JQ, Singh AK, Wilson MT, Satoh M, Stanic AK, Park JJ, et al. Immunoregulatory role of CD1d in the hydrocarbon oil-induced model of lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 2003;171:2142–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang JQ, Saxena V, Xu H, Van Kaer L, Wang CR, Singh RR. Repeated α-galactosylceramide administration results in expansion of NK T cells and alleviates inflammatory dermatitis in MRL-lpr/lpr mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:4439–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forestier C, Molano A, Im JS, Dutronc Y, Diamond B, Davidson A, et al. Expansion and hyperactivity of CD1d-restricted NKT cells during the progression of systemic lupus erythematosus in (New Zealand Black × New Zealand White)F1 mice. J Immunol. 2005;175:763–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng D, Liu Y, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Strober S. Activation of natural killer T cells in NZB/W mice induces Th1-type immune responses exacerbating lupus. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1211–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI17165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong S, Wilson MT, Serizawa I, Wu L, Singh N, Naidenko OV, et al. The natural killer T-cell ligand α-galactosylceramide prevents autoimmune diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2001;7:1052–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang B, Geng YB, Wang CR. CD1-restricted NK T cells protect nonobese diabetic mice from developing diabetes. J Exp Med. 2001;194:313–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dombrowicz D. Exploiting the innate immune system to control allergic asthma. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2786–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morishima Y, Ishii Y, Kimura T, Shibuya A, Shibuya K, Hegab AE, et al. Suppression of eosinophilic airway inflammation by treatment with α-galactosylceramide. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2803–14. doi: 10.1002/eji.200525994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jahng AW, Maricic I, Pedersen B, Burdin N, Naidenko O, Kronenberg M, et al. Activation of natural killer T cells potentiates or prevents experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1789–99. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Major AS, Singh RR, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. The role of invariant natural killer T cells in lupus and atherogenesis. Immunol Res. 2006;34:49–66. doi: 10.1385/ir:34:1:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh AK, Yang JQ, Parekh VV, Wei J, Wang CR, Joyce S, et al. The natural killer T cell ligand α-galactosylceramide prevents or promotes pristane-induced lupus in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1143–54. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kojo S, Adachi Y, Keino H, Taniguchi M, Sumida T. Dysfunction of T cell receptor AV24AJ18+,BV11× double-negative regulatory natural killer T cells in autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1127–38. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1127::AID-ANR194>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van der Vliet HJ, von Blomberg BM, Nishi N, Reijm M, Voskuyl AE, van Bodegraven AA, et al. Circulating Vα24+ Vβ11+ NKT cell numbers are decreased in a wide variety of diseases that are characterized by autoreactive tissue damage. Clin Immunol. 2001;100:144–8. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oishi Y, Sumida T, Sakamoto A, Kita Y, Kurasawa K, Nawata Y, et al. Selective reduction and recovery of invariant Vα24JαQ T cell receptor T cells in correlation with disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:275–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng D, Lee MK, Tung J, Brendolan A, Strober S. Cutting edge: a role for CD1 in the pathogenesis of lupus in NZB/NZW mice. J Immunol. 2000;164:5000–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hahn BH, Singh RR. Animal models of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Wallace DJ, Hahn BH, editors. Dubois’ lupus erythematosus. 7. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 299–355. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yue SC, Shaulov A, Wang R, Balk SP, Exley MA. CD1d ligation on human monocytes directly signals rapid NF-κB activation and production of bioactive IL-12. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11811–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503366102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendiratta SK, Martin WD, Hong S, Boesteanu A, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. CD1d1 mutant mice are deficient in natural T cells that promptly produce IL-4. Immunity. 1997;6:469–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh RR, Saxena V, Zang S, Li L, Finkelman FD, Witte DP, et al. Differential contribution of IL-4 and STAT6 vs STAT4 to the development of lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 2003;170:4818–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y, Goff RD, Zhou D, Mattner J, Sullivan BA, Khurana A, et al. A modified α-galactosyl ceramide for staining and stimulating natural killer T cells. J Immunol Methods. 2006;312:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh RR, Hahn BH, Sercarz EE. Neonatal peptide exposure can prime T cells and, upon subsequent immunization, induce their immune deviation: implications for antibody vs. T cell-mediated autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1613–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smolen JS, Steiner G, Aringer M. Anti-cytokine therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2005;14:189–91. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2134oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park SH, Weiss A, Benlagha K, Kyin T, Teyton L, Bendelac A. The mouse CD1d-restricted repertoire is dominated by a few autoreactive T cell receptor families. J Exp Med. 2001;193:893–904. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsuda JL, Naidenko OV, Gapin L, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Wang CR, et al. Tracking the response of natural killer T cells to a glycolipid antigen using CD1d tetramers. J Exp Med. 2000;192:741–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Esteban LM, Tsoutsman T, Jordan MA, Roach D, Poulton LD, Brooks A, et al. Genetic control of NKT cell numbers maps to major diabetes and lupus loci. J Immunol. 2003;171:2873–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takeda K, Dennert G. The development of autoimmunity in C57BL/6 lpr mice correlates with the disappearance of natural killer type 1-positive cells: evidence for their suppressive action on bone marrow stem cell proliferation, B cell immunoglobulin secretion, and autoimmune symptoms. J Exp Med. 1993;177:155–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan OT, Paliwal V, McNiff JM, Park SH, Bendelac A, Shlomchik MJ. Deficiency in β2-microglobulin, but not CD1, accelerates spontaneous lupus skin disease while inhibiting nephritis in MRL-Faslpr mice: an example of disease regulation at the organ level. J Immunol. 2001;167:2985–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang JQ, Chun T, Liu H, Hong S, Bui H, Van Kaer L, et al. CD1d deficiency exacerbates inflammatory dermatitis in MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1723–32. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richards HB, Satoh M, Jennette JC, Croker BP, Yoshida H, Reeves WH. Interferon-γ required for lupus nephritis in mice treated with the hydrocarbon oil pristane. Kidney Int. 2001;60:2173–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Santiago ML, Fossati L, Jacquet C, Muller W, Izui S, Reininger L. Interleukin-4 protects against a genetically linked lupus-like auto-immune syndrome. J Exp Med. 1997;185:65–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh RR, Yang JQ. NKT cells suppress autoreactive B cells [abstract] J Immunol. 2006;176(Suppl):S151. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh RR, Wen X, Yang JQ. iNKT cells suppress autoreactive B cells in a contact-dependent manner. Submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Capone M, Troesch M, Eberl G, Hausmann B, Palmer E, Mac-Donald HR. A critical role for the T cell receptor α-chain connecting peptide domain in positive selection of CD1-independent NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1867–75. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1867::aid-immu1867>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dang Y, Heyborne KD. Cutting edge: regulation of uterine NKT cells by a fetal class I molecule other than CD1. J Immunol. 2001;166:3641–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maeda M, Shadeo A, MacFadyen AM, Takei F. CD1d-independent NKT cells in β2-microglobulin-deficient mice have hybrid phenotype and function of NK and T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:6115–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marie JC, Liggitt D, Rudensky AY. Cellular mechanisms of fatal early-onset autoimmunity in mice with the T cell-specific targeting of transforming growth factor-β receptor. Immunity. 2006;25:441–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]