Abstract

Telomerase is a multi-subunit ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex that adds telomere repeats to the ends of linear chromosomes. Three essential telomerase components have been identified thus far: the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), the telomerase RNA component (TERC), and the TERC-binding protein dyskerin. Few other proteins are known to be required for human telomerase function, significantly limiting our understanding of both telomerase regulation and mechanisms of telomerase action. Here, we identify the ATPases pontin and reptin as telomerase components through affinity purification of TERT from human cells. Pontin interacts with both TERT and dyskerin, and the amount of TERT bound to pontin and reptin peaks in S phase, evidence for dynamic cell cycle-dependent regulation of TERT. Depletion of pontin and reptin markedly impairs accumulation of the telomerase RNP, indicating an essential role in telomerase assembly. These findings reveal an unanticipated requirement for additional enzymes in telomerase RNP biogenesis and suggest new approaches for inhibiting telomerase in human cancer.

Introduction

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) enzyme that adds DNA repeats to telomeres, nucleoprotein structures that cap the ends of chromosomes (Blackburn, 2001). Telomerase comprises a protein subunit, TERT, and an RNA subunit, TERC, which act together to copy the template sequence within TERC to the chromosome end. By synthesizing telomere repeats, telomerase offsets the end replication problem, the inability of DNA polymerase to fully replicate chromosome ends, thus keeping telomeres sufficiently long and stable. In settings of insufficient telomerase, telomeres progressively shorten ultimately compromising telomere end protection at a subset of chromosome ends. These dysfunctional telomeres impair stem cell self-renewal, leading to profound defects in proliferating tissues of telomerase knockout mice (Lee et al., 1998; Allsopp et al., 2003). In human cancer, telomerase is upregulated where it serves to promote tumor proliferation and survival by supporting the maintenance of functional telomeres. These crucial roles for telomerase in tissue progenitor cells and in developing cancers highlight the need to understand mechanisms of human telomerase regulation and telomerase action.

One means by which telomerase is regulated involves the protein subunits of the telomere itself. Each telomere is bound by a six-member protein complex, shelterin, which remodels the chromosome end into a t-loop conformation, prevents the telomere from being recognized as a double strand break and protects it from recombination (de Lange, 2005). In addition to these structural roles at the telomere, components of the shelterin complex control the action of telomerase at the 3′ chromosome end. Experiments examining the function of the shelterin components TRF1 and TRF2 through over-expression indicate that these proteins can inhibit the action of telomerase, leading to telomere shortening (Smogorzewska et al., 2000). POT1, a shelterin protein that binds the single stranded telomere overhang, can both inhibit telomerase at telomere ends (Loayza and De Lange, 2003), and can serve as a processivity factor for telomerase, enhancing telomerase-mediated telomere lengthening in vitro (Wang et al., 2007; Xin et al., 2007). Thus, telomere-binding proteins can control the activity of telomerase at chromosome ends, which is important for telomere length homeostasis.

Given the complexity of other polymerases and of other RNPs, it is likely that human telomerase requires multiple associated proteins for proper assembly, regulation, and enzymatic action on its substrate (Collins, 2006). Although few essential telomerase-associated proteins have thus far been identified, several observations suggest the existence of other telomerase components. Biochemical analyses of human telomerase by glycerol gradient sedimentation and gel filtration have shown that telomerase resides in a large complex of approximately 1-2MDa, with known components accounting for only a fraction of this mass (Schnapp et al., 1998; Xin et al., 2007). Although recombinant TERT and TERC can produce telomerase activity in vitro, telomerase reconstitution is facilitated by the presence of a eukaryotic lysate and ATP (Weinrich et al., 1997; Holt et al., 1999; Wenz et al., 2001). Thus, other cellular factors may aid in the assembly of telomerase or assist in its catalytic function.

Analysis of TERC structure and the human disease dyskeratosis congenita led to identification of the third telomerase component discovered thus far, the RNA binding protein dyskerin (Mitchell et al., 1999a; Mitchell et al., 1999b). Dyskerin binds the H/ACA motif, a sequence in TERC required for its accumulation, and a sequence present in a subset of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) involved in RNA modification (Meier, 2005). In patients with the X-linked form of dyskeratosis congenita, mutations in dyskerin cause a significant reduction in TERC levels, diminished telomerase activity and very short telomeres. Telomere dysfunction presumably underlies the dyskeratosis congenita phenotype, which includes severe defects in multiple self-renewing tissues including blood, skin, lung and oral mucosa (Marrone et al., 2005). Consistent with a central role for impaired telomerase function in this disease, autosomal dominant forms of dyskeratosis congenita are linked to mutations in TERT and TERC (Vulliamy et al., 2001; Armanios et al., 2005). Although dyskerin is associated with catalytically active telomerase (Cohen et al., 2007) and is clearly required for TERC accumulation, its precise function in the telomerase RNP remains to be determined (Mitchell et al., 1999b).

The low abundance of telomerase in human cancer cell lines and in mammalian tissues has presented significant challenges in studying telomerase in biochemical terms. As a consequence, our understanding of how human telomerase is assembled and regulated and how it interacts with telomeres remains limited. To identify new components of the human telomerase complex and to advance our understanding of telomerase regulation and function, we purified TERT complexes from human cells using a dual affinity chromatography strategy coupled with mass spectrometry. Here, we report the identification of the related ATPases pontin and reptin as components of a telomerase complex. We find that these new telomerase components interact with both TERT and dyskerin at the endogenous level and are essential for telomerase holoenzyme assembly.

Results

Purification and mass spectrometric identification of human TERT complex components

To characterize the size of the telomerase holoenzyme complex, we performed glycerol gradient sedimentation analyses using extracts from HeLa cells and extracts from HeLa cells stably expressing Flag-TERT from a retroviral promoter. Endogenous telomerase activity, measured by telomerase repeat amplification protocol (TRAP), and endogenous TERC, assayed by northern blot, co-sedimented in a size range consistent with previous estimates of 1-2MDa (Figure 1A) (Schnapp et al., 1998; Xin et al., 2007). Flag-TERT similarly sedimented as a large complex, suggesting that retrovirally expressed TERT associates stably with other factors that have potential relevance for telomerase function. To identify novel protein components of the telomerase complex, we purified TERT protein complexes using a modified TAP tag approach. TERT was fused at its N terminus with a dual affinity tag consisting of a protein A moiety and three HA epitopes separated by a TEV protease cleavage site (AH3). To determine whether our tagged TERT protein was functional, we expressed AH3-TERT by retroviral transduction in primary human fibroblasts that lack TERT expression and senesce after many population doublings due to progressive telomere shortening. Tagged TERT reconstituted telomerase activity, lengthened telomeres, and immortalized human fibroblasts, indicating that AH3-TERT is fully active at telomere (Figure S1).

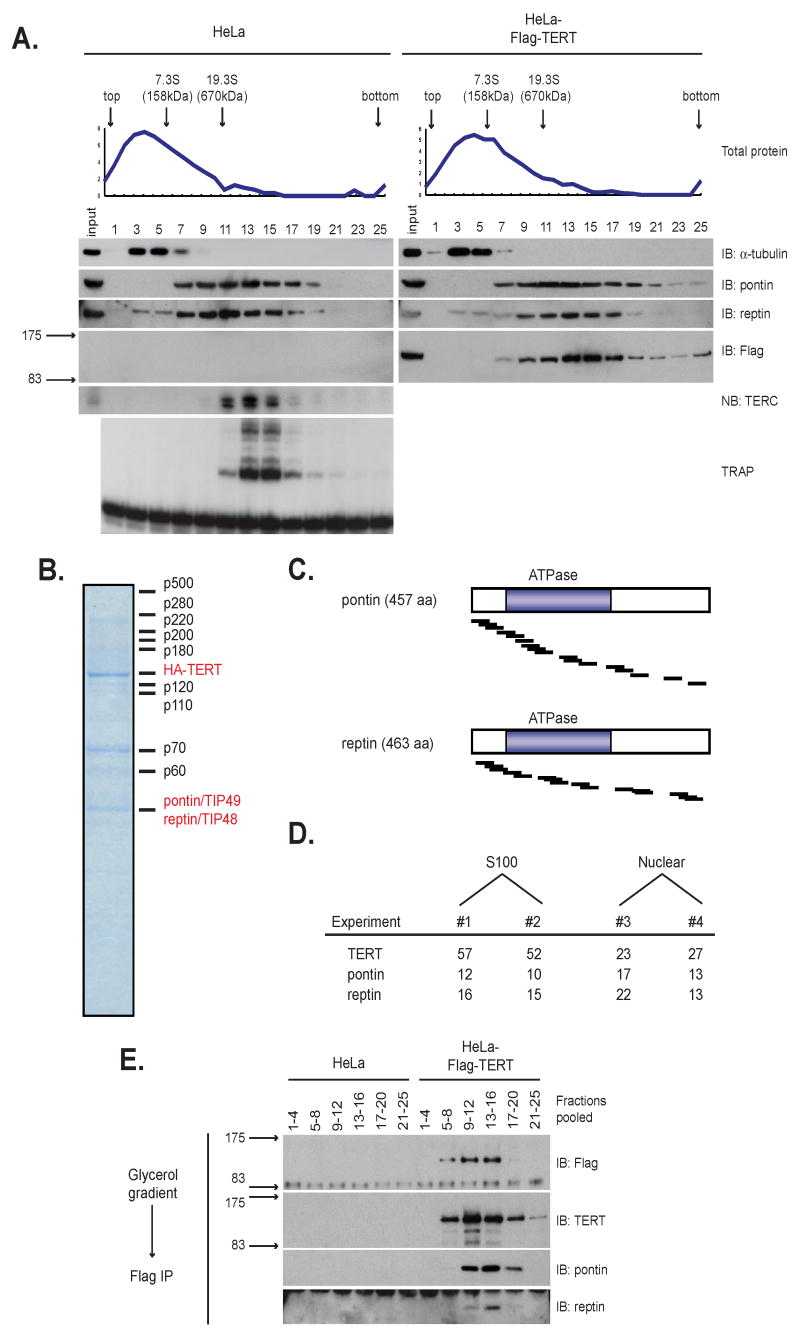

Figure 1. Pontin and reptin co-purify with TERT through dual affinity purification and are components of a large TERT complex.

(A) Sedimentation of endogenous telomerase and Flag-TERT complexes. Extracts from HeLa cells (left) and HeLa-Flag-TERT cells (right) were fractionated through 10-30% glycerol gradients. Total protein across the gradient was measured by Bradford assay (top). IB, immunoblot; NB, northern blot.

(B) Coomassie stain of affinity-purified TERT complexes fractionated by SDS-PAGE.

(C) Diagram of pontin and reptin proteins shows location of unique peptides identified by MS (black bars). Blue boxes denote ATPase domains.

(D) Number of unique peptides obtained by mass spectrometry from four independent TERT purifications.

(E) Immunoprecipitation of Flag-TERT complexes after sedimentation in 1A. Adjacent fractions were pooled and immunoprecipitated. Pontin and reptin association with TERT peaked in fractions 13-16.

For telomerase complex purifications, HeLa S3 cells expressing AH3-TERT were grown in suspension cultures. In optimizing conditions for extracting TERT protein, we found that a detergent-based lysis procedure solubilized approximately 75% of AH3-TERT (referred to here as “S100” extract) and salt extraction of the nuclear pellet liberated the remaining 25% of AH3-TERT (data not shown). To ensure a thorough analysis of TERT-associated proteins, TERT complexes were purified from both S100 extracts (n=2) and nuclear extracts (n=2). AH3-TERT was purified on rabbit IgG resin, eluted specifically with TEV protease, captured again with anti-HA resin, then eluted and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Figure S1E,F). After staining with Coomassie blue, protein bands were excised, digested and analyzed by nanoflow reversed-phase LC-MS/MS (see Materials and Methods). Mass spectrometric analysis of the 127kDa band identified between 23 and 57 unique peptides matching the TERT open reading frame (Figure 1B, D). In addition, at least six co-purifying polypeptides were enriched in each TERT purification compared to negative controls (Figure 1B).

Mass spectrometric analysis of the 50kDa band, one of the most prominent TERT-associated proteins by SDS-PAGE, revealed that it comprised two independent proteins, the related ATPases pontin and reptin. Pontin and reptin peptides were recovered in each of four independent experiments, spanning more than 50% of the pontin and reptin open reading frames (Figure 1B,C,D). To study their role in the telomerase complex, we generated highly specific polyclonal antibodies to pontin and reptin. We found that pontin and reptin participate in large complexes, which overlap the size distributions of both endogenous telomerase and Flag-TERT by glycerol gradient sedimentation (Figure 1A). Analysis of extracts from Flag-TERT cells fractionated by glycerol gradient sedimentation revealed that endogenous pontin and reptin were stably associated with Flag-TERT (Figure 1E). These results show that endogenous pontin and reptin interact with Flag-TERT in a large molecular weight complex. Based on these data, we investigated a potential role for pontin and reptin in telomerase function using biochemical and genetic approaches.

Pontin and reptin interact with endogenous TERT protein

Pontin and reptin are well conserved AAA+ ATPases (for ATPases associated with various cellular activities) and have been identified in chromatin remodeling complexes, as co-factors for the transcriptional regulators c-myc and β-catenin and as proteins that interact with small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) complexes (Newman et al., 2000; Gallant, 2007). Pontin and reptin physically interact and are thought to function together, although there is some evidence that pontin and reptin can act independently or in an opposing fashion (Rottbauer et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2005). Pontin-specific shRNA sequences not only depleted pontin, but also co-depleted reptin (Figure 2A). Similarly, shRNA sequences directed against reptin co-depleted pontin, indicating that these proteins mutually depend on their interaction for stability. We also found that pontin and reptin biochemically co-depleted one another in co-transfection assays (Fig. S2A). Furthermore, HA-TERT interacted with Flag-pontin, but not with Flag-reptin in co-transfection experiments (Fig. S2B, S2C). Interestingly, the addition of pontin facilitated interaction between Flag-reptin and HA-TERT by co-immunoprecipitation, indicating that reptin is recruited into a TERT complex through bridging pontin molecules (Fig. S2B). Association of endogenous pontin and reptin with Flag-TERT stably expressed in HeLa cells was resistant to treatment with DNase I, ethidium bromide, and RNase A, indicating that these interactions are not mediated by co-purifying nucleic acids (Figure S2D). Together, these data show that pontin and reptin are interdependent and are recruited into TERT complexes through an association between TERT and pontin.

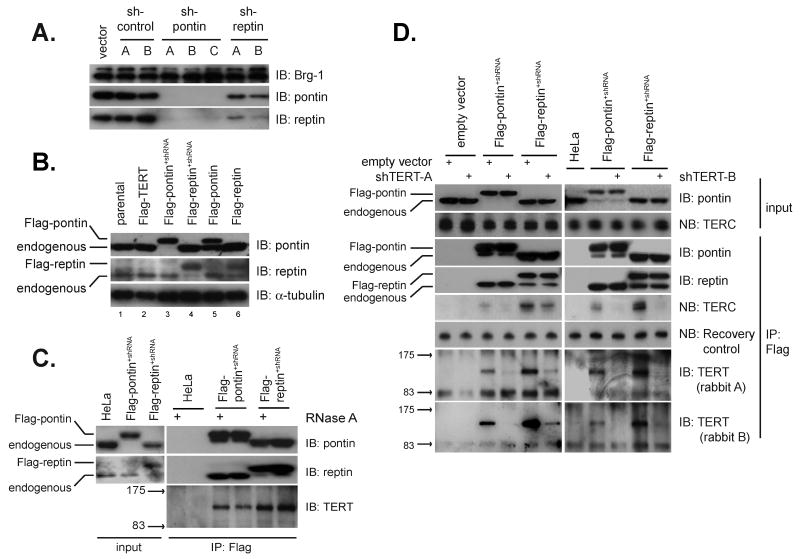

Figure 2. Pontin and reptin interact with endogenous TERT and TERC.

(A) Western blot showing genetic co-depletion of endogenous pontin and reptin with shRNA specifically targeting either protein. Control shRNA had no effect on pontin or reptin levels. Western for Brg-1 was used as a loading control. Independent shRNAs are denoted: A,B,C.

(B) Flag-pontin expressed by retroviral transduction under-accumulates relative to endogenous levels (lane 5). Serial transduction with shRNA-resistant Flag-pontin followed by shRNA against endogenous pontin, results in depletion of endogenous pontin and accumulation of Flag-pontin to endogenous levels by pontin western blot (compare lanes 1, 3). Cells treated in this manner are referred to as Flag-pontin+shRNA cells. A similar strategy was used to generate Flag-reptin+shRNA cells.

(C) Endogenous TERT is detected in pontin and reptin complexes purified from Flag-pontin+shRNA and Flag-reptin+shRNA cells. Flag immunoprecipitation was followed by western blot with anti-TERT antibodies. RNase A treatment during immunoprecipitation did not reduce TERT association.

(D) Pontin and reptin interact with endogenous TERT and with endogenous TERC in a largely TERT-dependent manner. Flag-pontin+shRNA and Flag-reptin+shRNA cells treated with independent shRNA vectors targeting TERT (A and B) resulted in decreased association of pontin and reptin with TERT and TERC. A recovery control RNA was spiked into each IP-northern blot sample to control for differential nucleic acid extraction.

We reasoned that endogenous TERT should be detectable in purified complexes of pontin and reptin. However, reliable detection of the endogenous TERT protein by western blot has proven difficult due to both the low abundance of TERT and a dearth of antibodies that recognize TERT protein (Wu et al., 2006). We sought to address these significant technical hurdles by developing quantitative methods for immunoprecipitating pontin and reptin and by enhancing our ability to detect TERT through generation of high affinity polyclonal antibodies. In attempting to overexpress pontin, we noticed that Flag-pontin under-accumulated relative to the endogenous protein (Figure 2B, compare lanes 1 and 5). However, expression of an shRNA-resistant form of Flag-pontin followed by transduction of an shRNA retrovirus targeting the endogenous pontin protein resulted in accumulation of Flag-pontin to endogenous levels (Figure 2B, compare lanes 1 and 3). Reptin was substituted with Flag-reptin by an analogous strategy. (Figure 2B). We refer to these cell lines as Flag-pontin+shRNA and Flag-reptin+shRNA, respectively. Substituting pontin and reptin with tagged versions allows for quantitative immunoprecipitation using well-characterized monoclonal antibodies directed against the tag, a strategy routinely employed in yeast.

To study the endogenous TERT protein, we generated rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against a bacterially expressed TERT polypeptide, followed by affinity purification of anti-TERT antibodies on the cognate antigen (see Materials and Methods). In extensive testing, these anti-TERT antibodies readily recognized stably expressed TERT by western blot and immunofluorescence, and specifically immunoprecipitated both TERC by northern blot and telomerase activity by TRAP assay (Figure S4). To determine if endogenous TERT associates with endogenous levels of pontin and reptin, extracts from Flag-pontin+shRNA and Flag-reptin+shRNA cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag resin and assayed by western blot with anti-TERT antibodies. Anti-TERT antibodies reproducibly detected a polypeptide consistent with TERT's molecular mass of 127 kDa in pontin and reptin immunoprecipitates, but not in negative controls (Figure 2C). Anti-TERT immunoreactive bands were significantly diminished by two TERT-specific shRNAs and were recognized by affinity purified antibodies from two independent rabbits (Figure 2D). As an independent measure of the association of endogenous telomerase with pontin and reptin, we found that TERC was specifically associated with pontin and reptin by immunoprecipitation-northern blot and this interaction was largely TERT-dependent (Figure 2D). Together, these data show that pontin and reptin interact with endogenous TERT and TERC, the catalytic core of telomerase.

Essential role for pontin and reptin in TERC accumulation

Based on these data showing that TERT associates with pontin and reptin at the endogenous level, we investigated how loss of pontin and reptin affected telomerase activity using pontin shRNA that depletes both pontin and reptin. Whole cell lysates prepared from HeLa cells transduced with shRNA vectors targeting pontin were analyzed for telomerase activity by TRAP assay. Treatment with pontin shRNA severely diminished telomerase activity to 10-20% of wild-type levels (Figure 3A, B). To understand why telomerase activity was so significantly reduced following pontin and reptin depletion, we assessed TERC levels by northern blot. Strikingly, three different pontin shRNA sequences markedly reduced TERC RNA to approximately 25% the level in negative controls (Figure 3C). Pontin and reptin were previously shown to be required for accumulation of the human U3 small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) (Watkins et al., 2004). As a control, we confirmed that pontin and reptin depletion reduced U3 snoRNA levels, but did not affect the amount of U1, a small nuclear RNA involved in mRNA splicing (Figure 3C).

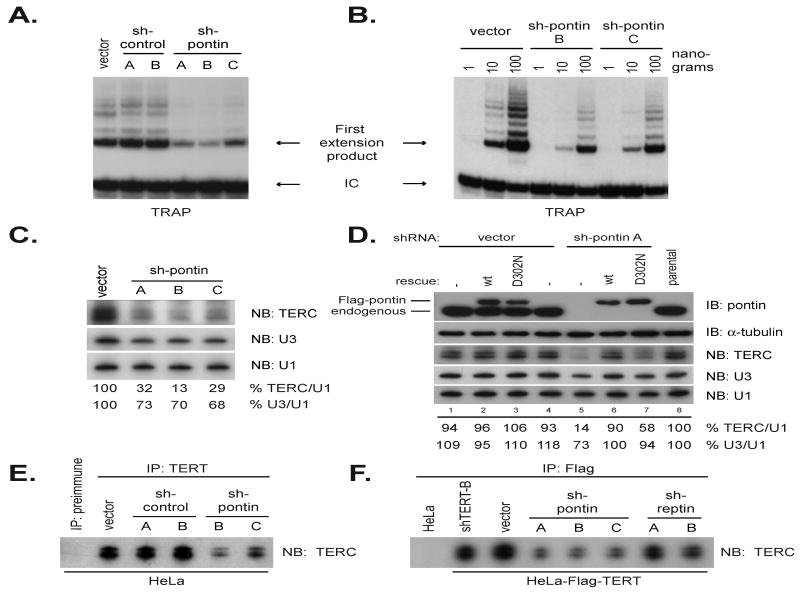

Figure 3. Pontin and reptin are required for telomerase activity and for TERC accumulation.

(A) Diminished telomerase activity by pontin shRNA in HeLa cells.

(B) Titration of protein extracts from (A). Telomerase activity is reduced to 10-20% of wild-type levels by pontin shRNA B or C sequences.

(C) TERC depends on pontin and reptin for accumulation to wild-type levels. Pontin shRNA reduced TERC to approximately 25% of wild-type levels. Band intensities for TERC and U3 snoRNA were quantified and presented as a fraction of the loading control U1 snRNA.

(D) ATPase activity of pontin is required for maintenance of TERC levels. HeLa cells depleted of pontin using shRNA are rescued by expression of a wild-type Flag-pontin construct, but not the ATPase-mutant Flag-pontinD302N. Note that both pontin cDNAs contained silent mutations rendering them insensitive to the pontin A shRNA. Band intensities were quantified as in 5C.

(E) Endogenous TERT-TERC association is compromised following pontin and reptin depletion. Immunoprecipitation using anti-TERT antibodies in HeLa cells treated with shRNA to pontin reveal decreased TERT-TERC association relative to control shRNA vectors.

(F) Experiment in 3E was repeated in HeLa-Flag-TERT cells using anti-Flag resin to immunoprecipitate Flag-TERT.

To further address the specificity of the pontin knockdown effect on TERC, we asked if TERC levels were rescued by retroviral transduction with an shRNA-resistant Flag-pontin. Pontin knockdown had no effect on TERC levels in HeLa cells expressing shRNA-resistant Flag-pontin (Figure 3D, lane 6), demonstrating that loss of TERC in cells treated with pontin shRNA is not due to off-target effects. Correspondingly, we found that U3 levels were also restored. The ability to rescue the defect in TERC levels allowed us to ask if pontin's ATPase activity is required for TERC accumulation. TERC levels were significantly reduced in HeLa cells expressing shRNA-resistant Flag-pontinD302N following treatment with pontin shRNA, indicating that pontin ATPase activity is required to maintain wild-type levels of TERC (Figure 3D, lane 7). To understand if pontin depletion affects only a pool of TERC molecules that are free of TERT or if the TERC associated with TERT is also reduced, we measured the amount of TERC bound by TERT in cells treated with pontin shRNA. Immunoprecipitates of endogenous TERT in HeLa cells or ectopically expressed TERT in HeLa-Flag-TERT cells contained significantly less TERC in cells treated with pontin shRNA compared to negative controls (Figure 3E, F). Together, these results show that pontin and reptin are essential for telomerase activity and for TERC accumulation through a mechanism that requires ATPase function.

Pontin and reptin interact with dyskerin, forming a complex required for telomerase RNP assembly

The loss of TERC that occurs with depletion of pontin and reptin was particularly striking because it is reminiscent of the reduction in TERC levels seen in those dyskeratosis congenita patients with mutations in dyskerin. Dyskerin binds TERC at its 3′ H/ACA motif, a structural element required for TERC stability. With mutation or inactivation of dyskerin, TERC levels diminish, resulting in decreased telomerase activity (Mitchell et al., 1999b). The similar requirements for pontin, reptin and dyskerin in maintenance of TERC levels suggested a functional relationship among these proteins. To determine whether dyskerin interacts with pontin or reptin, we first performed co-transfection assays. HA-dyskerin bound both Flag-pontin and Flag-reptin, but not the negative control Flag-BAF57 in co-transfection assays (Figure 4A). Furthermore, when transfected alone, Flag-dyskerin efficiently complexed with endogenous pontin and reptin (Figure 4B). To understand the interaction between dyskerin and telomerase, TERC and/or TERT were co-expressed with Flag-dyskerin. Neither exogenous TERT nor exogenous TERC altered the amount of pontin or reptin associated with Flag-dyskerin. Co-expression of HA-TERT with Flag-dyskerin resulted in a minor amount of HA-TERT in Flag-dyskerin immunoprecipitates. However, co-expression of TERC and TERT dramatically enhanced the amount of TERT associated with dyskerin, consistent with recruitment of TERT into dyskerin complexes through their common interaction with TERC (Figure 4B) (Mitchell et al., 1999b). Consistent with these findings, immunoprecipitation of stably expressed Flag-TERT pulled down endogenous dyskerin in an RNase A-sensitive manner (Figure 4C, lanes 11, 12).

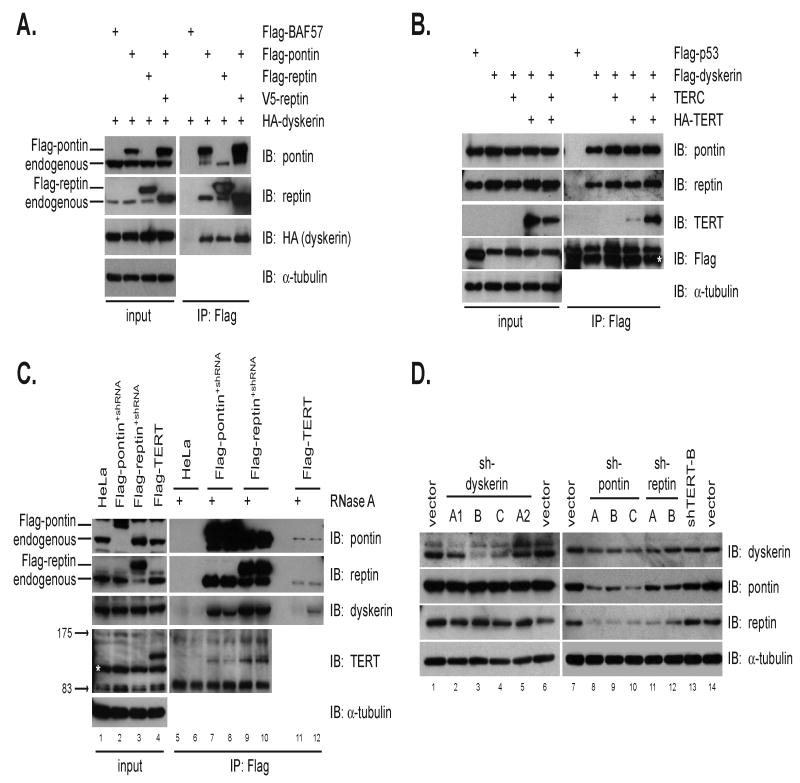

Figure 4. Pontin and reptin interact with dyskerin and are required for dyskerin accumulation.

(A) HA-dyskerin associates with either Flag-pontin or Flag-reptin by anti-Flag immunoprecipitation from co-transfected cells. Flag-BAF57 was used as a negative control.

(B) Flag-dyskerin co-immunoprecipitates endogenous pontin and reptin in transfected 293T cells. HA-TERT interacts weakly with Flag-dyskerin, but shows enhanced binding by co-expression of TERC. Flag-p53 serves as a negative control. The white asterisk indicates mouse IgG heavy chain.

(C) Dyskerin, pontin, and reptin interact at the endogenous level in an RNase A-insensitive manner. Anti-Flag immunoprecipitation in Flag-pontin+shRNA and Flag-reptin+shRNA cells readily recovers endogenous dyskerin and TERT. Extracts from HeLa cells stably expressing Flag-TERT were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag resin in parallel. RNase A treatment significantly reduced the amount of dyskerin associated with Flag-TERT, but did not alter the amount of dyskerin bound to pontin or reptin. Asterisk indicates a non-specific band detected by western of whole cell lysate with anti-TERT antibodies.

(D) Suppression of pontin or reptin with shRNA impairs dyskerin accumulation (right panels), but shRNA vectors targeting dyskerin affect steady state levels of neither pontin nor reptin (left panels).

To understand the nature of this complex at the endogenous level, we used Flag-pontin+shRNA cells and Flag-reptin+shRNA cells to immunoprecipitate pontin and reptin complexes (Figure 4C). Endogenous dyskerin was readily detected in pontin and reptin complexes, indicating that dyskerin interacts with both pontin and reptin at the endogenous level. We further noted that the pontin-reptin-dyskerin association was not sensitive to RNase A treatment, indicating that these contacts are not mediated by co-purifying TERC. Thus, TERC connects TERT to dyskerin, while pontin and reptin bind both TERT and dyskerin through protein-protein contacts.

To study the potential interdependence of dyskerin with pontin and reptin, we depleted each protein using RNA interference and assessed protein levels by western blot. Dyskerin was depleted to varying degrees with three independent shRNA sequences, but no reciprocal effect on levels of either pontin or reptin was detected (Figure 4D, lanes 3, 4). In contrast, knockdown of pontin and reptin led to a significant reduction in steady-state dyskerin levels (Figure 4D, lanes 8-10). Thus, dyskerin depends in part on pontin and reptin for expression at wild-type levels, highlighting the critical importance of pontin and reptin in dyskerin function.

Pontin interacts directly with dyskerin and TERT

Our data show that pontin and reptin associate with both known protein constituents of telomerase, TERT and dyskerin. To better characterize the nature of these interactions, we mapped the domain of TERT that mediates the interaction with pontin and reptin. We assessed binding of endogenous pontin and reptin by immunoprecipitating a series of Flag-tagged amino terminal or carboxy terminal deletion fragments of TERT in 293T cells (Figure 5A, B). Although fragments containing the C-terminal domains of TERT did not co-immunoprecipitate pontin and reptin, extending these fragments into the RT domain conferred pontin and reptin binding ability (Figure 5B, IP lanes 6-11). Similarly, extending the N-terminal fragment into the RT domain enabled a more efficient interaction with pontin and reptin (Figure 5B, IP lanes 2-4). Together, these results implicate the central RT domain in binding pontin and reptin.

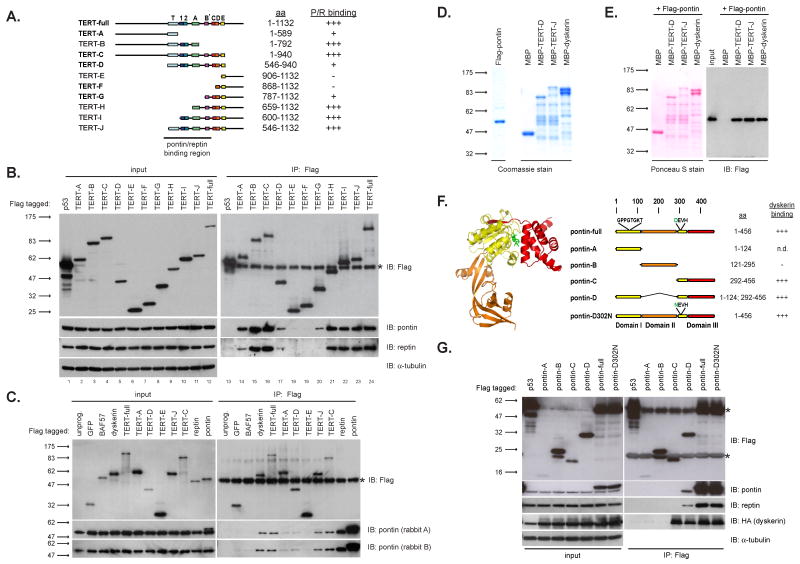

Figure 5. Pontin interacts directly with dyskerin and TERT.

(A) Illustration of TERT fragments used for binding assays. Results from 5B are scored in the right column as “P/R binding.”

(B) Transfection assays in 293T show that Flag-tagged fragments of TERT incorporating the central reverse transcriptase domains efficiently co-immunoprecipitate endogenous pontin and reptin. Flag-p53 was used as a negative control.

(C) Rabbit reticulocyte lysate transcription-translation of Flag-tagged dyskerin, TERT, and TERT fragments co-immunoprecipitate rabbit pontin intrinsic to the lysate.

(D) Coomassie stained gels of bacterially expressed and purified Flag-pontin, MBP-TERT fragments, and MBP-dyskerin purified for direct binding assay in 5E.

(E) Direct binding assay between Flag-pontin and MBP-tagged proteins. MBP-tagged proteins were immobilized with amylose resin and incubated with Flag-pontin, washed, and analyzed by western blot with anti-Flag antibodies. Ponceau S stain shows relative amount of MBP-tagged proteins.

(F) Illustration of pontin fragments used for binding assays. Ribbon diagram for a pontin monomer (PDB 2C9O; (Matias et al., 2006)) guided the design for our pontin fragments. Results from 5G are scored in the right column as “dyskerin binding”.

(G) Co-transfection of HA-dyskerin with Flag-pontin fragments in 293T cells show that the C-terminal fragment of pontin (pontin-C) is sufficient to co-immunoprecipitate HA-dyskerin. Flag-p53 was used as a negative control.

Recombinant TERT has been extensively studied using rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRL) as an expression system. Remarkably, we found that Flag-TERT as well as Flag-dyskerin expressed in RRL co-immunoprecipitated rabbit pontin intrinsic to the lysate, whereas negative controls Flag-GFP and Flag-BAF57 did not (Figure 5C). Expression of a subset of the deletion mutants of TERT in RRL showed the same requirement for the RT domain in binding pontin seen in transfected cells (Figure 5B,C).

To study interactions in the absence of other eukaryotic proteins, we expressed MBP-dyskerin, two MBP-TERT fragments and Flag-(His)6-pontin in bacteria (Figure 5D). Purified Flag-(His)6-pontin was incubated with immobilized MBP-dyskerin or MBP-TERT in a pull-down assay and bound pontin was assayed by Flag western blot. Recombinant pontin bound recombinant MBP-dyskerin and both MBP-TERT proteins, indicating that pontin interacts directly with both dyskerin and TERT (Figure 5E). Furthermore, the fact that pontin bound MBP-TERT-D provides additional evidence that the RT domain of TERT mediates the interaction with pontin.

To understand which region of pontin mediates interaction with dyskerin, we expressed pontin domains based on the X-ray crystal structure of pontin (Matias et al., 2006). Domains I and III interact to form the hexamer ring, whereas domain II projects downward from the plane of the ring. Expression of Flag-tagged pontin fragments (Figure 6F) with HA-dyskerin in 293T cells revealed that pontin-C and pontin-D fragments bound HA-dyskerin like full-length pontin. In contrast, pontin-B comprising domain II did not bind HA-dyskerin (Figure 5G). Together, these data show that pontin directly interacts with dyskerin and with TERT's RT domain, and suggest that the interaction surface of pontin required for binding dyskerin resides in its C-terminal domain, the region containing domain III and the Walker B motif.

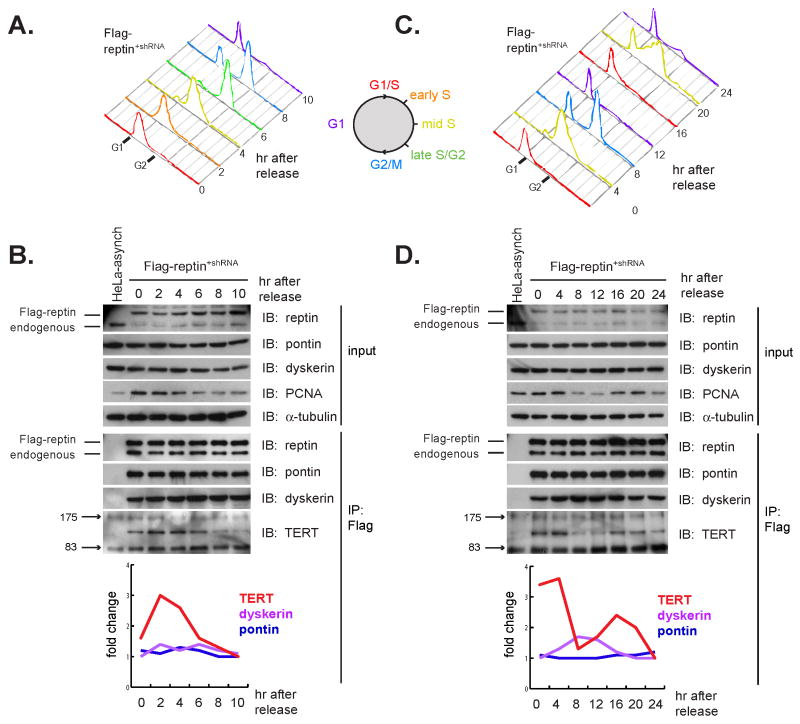

Figure 6. Pontin and reptin interact with TERT in S phase.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of DNA content in HeLa-Flag-reptin+shRNA cells released from double thymidine blockade over a ten hour time course. Cells were released from the second block and harvested at two hour intervals, and a portion of cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide to monitor synchrony. The zero hour time point corresponds to unreleased cells.

(B) Co-immunoprecipitation of reptin with TERT and dyskerin over a ten hour timecourse. The association of reptin with pontin and dyskerin is constant across the cell cycle, whereas associated TERT peaks in S phase. Band intensities were quantified and displayed as fold change in the accompanying graph. Western blot for PCNA was used as an independent marker of S phase.

(C) Flow cytometry analysis of DNA content in HeLa-Flag-reptin+shRNA cells synchronized using double thymidine blockade as in 6A, except cells were harvested at four hour intervals over a 24 hour time course.

(D) Co-immunoprecipitation of reptin with pontin, dyskerin, and TERT though a 24 hour timecourse following synchronization shown in 6C. Band intensities were analyzed as in 6B. Note that the amount of TERT in the reptin complex increases during the second S phase with kinetics similar to PCNA.

Dynamic regulation of TERT during the cell cycle: the TERT-pontin-reptin complex peaks in S phase

Although telomerase lengthens short telomeres preferentially during S phase of the cell cycle in yeast (Marcand et al., 2000), and human telomerase localizes to telomeres during S phase (Jady et al., 2006; Tomlinson et al., 2006), it is unclear what mechanisms ensure that human telomerase acts on telomere ends in S phase. To determine whether pontin and reptin contribute to cell cycle control of endogenous telomerase, we synchronized Flag-reptin+shRNA cells at the G1/S transition using double thymidine blockade. Cells were released and harvested at two hour intervals, and synchrony was monitored by measuring DNA content by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry (Figure 6A).

Immunoprecipitation of Flag-reptin showed that neither the total reptin pool nor the amount of pontin or dyskerin bound to reptin varied through the cell cycle. In marked contrast, the amount of TERT associated with reptin peaked in S phase. The amount of TERT bound to reptin was three fold higher in S phase than in G2, M or G1 (Figure 6B). To control for potential confounding effects from thymidine blockade, we repeated the synchronization experiment and carried the HeLa-Flag-reptin+shRNA cells through two cell cycles. We found that the association of reptin with endogenous TERT peaked in consecutive S phases, closely matching the pattern of expression of the S-phase marker PCNA (Figure 6C,D). Endogenous TERT also preferentially associated with pontin in Flag-pontin+shRNA cells and the S-phase specific interaction among TERT, pontin and reptin was also seen in experiments employing a thymidine-aphidicolin protocol for synchronization (Figure S5). These data provide evidence for dynamic regulation of telomerase during the cell cycle and indicate that TERT's association with pontin and reptin peaks in S phase, which may reflect cell cycle regulation of total TERT protein and/or assembly of telomerase in the phase of the cell cycle during which it must act on telomeres.

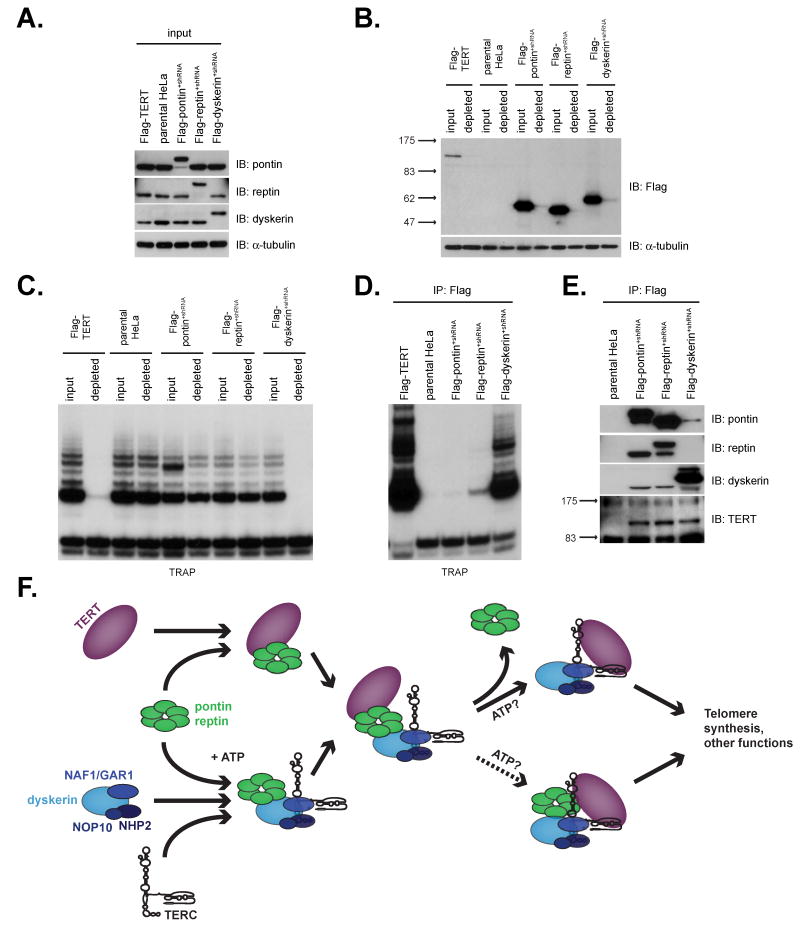

TERT exists in at least two complexes

Our observations that 1) pontin and reptin are required for telomerase biogenesis and 2) the pontin-reptin-TERT complex peaks during each S phase led us to hypothesize that TERT complexes are dynamic in nature and that pontin and reptin may be involved in cyclical telomerase assembly. We asked to what extent pontin and reptin associate with “active” telomerase particles as measured using the TRAP assay. Flag antibody immunoprecipitation of lysates from Flag-pontin+shRNA, Flag-reptin+shRNA or Flag-dyskerin+shRNA cells, in which pontin, reptin, or dyskerin was replaced by a Flag-tagged version at the endogenous level, quantitatively depleted each Flag-tagged protein from the lysate (Figure 7A,B). TRAP assays performed on lysates pre- and post-immunodepletion demonstrated that, whereas immunoprecipitation of dyskerin or over-expressed Flag-TERT depleted TRAP activity from the lysate, immunoprecipitation of pontin and reptin did not reduce the overall level of TRAP activity in the extract (Figure 7C). Accordingly, TRAP assays performed on the anti-Flag immunoprecipitates showed that dyskerin and Flag-TERT brought down robust TRAP activity, whereas pontin and reptin were associated with a small, but reproducible amount of activity (Figure 7D). Remarkably, however, analysis of the immunoprecipitates by western blot for endogenous TERT showed that pontin and reptin were associated with at least as much TERT protein as that bound by dyskerin (Figure 7E). Therefore, our data indicate that pontin and reptin associate with a significant population of TERT molecules that do not yield high level TRAP activity. This marked discordance between TERT protein and catalytic activity in vitro suggests specific models for understanding how telomerase is assembled in human cancer cells (see Discussion). Together, these data establish pontin and reptin as both TERT-interacting proteins and dyskerin-interacting proteins and show that pontin and reptin are required for assembly of a core telomerase complex, including TERT, TERC and dyskerin.

Figure 7. TERT exists in multiple telomerase complexes.

(A) Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates prepared from “replacement” cell lines for pontin, reptin, and dyskerin. Retrovirally introduced Flag-tagged pontin, reptin, or dyskerin accumulates to endogenous levels upon depletion of the respective endogenous proteins with shRNA. Note that Flag-pontin, -reptin, and -dyskerin coding sequences contain silent mutations rendering them insensitive to the shRNA vectors.

(B) Whole cell lysates in 7A were depleted of the Flag-tagged protein using anti-Flag resin. Depletion was assessed by western blot with anti-Flag antibodies.

(C) TRAP assay of extracts in 7B shows that immunoprecipitation of Flag-TERT and Flag-dyskerin, but not Flag-pontin or Flag-reptin, depletes telomerase activity.

(D) TRAP assay on immunoprecipitates from 7C. Reptin co-immunoprecipates a small but reproducible amount of telomerase activity.

(E) TERT associates similarly with pontin/reptin and dyskerin by immunoprecipitation-western blot. Isolated pontin and reptin complexes have low TRAP activity but substantial TERT protein (shown in 7D).

(F) Model for telomerase assembly facilitated by pontin and reptin. Pontin and reptin are required for accumulation of a TERC- and dyskerin-containing RNP through steps which require ATPase function (bottom). Pontin and reptin also bind TERT (top) and may help to bring together or remodel a nascent TERT/TERC/dyskerin complex through a stepwise process. Other factors and/or ATP hydrolysis may convert the complex into the enzymatically active, TRAP-positive telomerase complex. At this point, pontin and reptin may dissociate from telomerase or remain associated with a telomerase complex that has low activity in vitro. See discussion for further details.

Discussion

Through biochemical purification of human TERT complexes, we have identified the ATPases pontin and reptin as essential telomerase components. Pontin interacts with both known protein constituents of telomerase, dyskerin and TERT. Importantly, the association of pontin and reptin with dyskerin and TERT occurs at the endogenous level in human cells. Furthermore, the pontin-reptin-TERT complex is cell cycle regulated and peaks during each S phase. In loss-of-function experiments, we find that pontin and reptin are critical for telomerase activity and for accumulation of TERC and dyskerin. Finally, pontin and reptin co-immunoprecipitate a substantial pool of TERT protein that yields only low enzymatic activity as detected by standard TRAP assay. Together, these data identify two new enzymes required for telomerase assembly and reveal a previously unappreciated complexity in telomerase biogenesis.

Multiple TERT protein complexes in human cancer cells: a model for telomerase assembly

Our data indicate that pontin and reptin serve two related roles in telomerase RNP assembly. Through their direct interaction with dyskerin, pontin and reptin are required for assembling a TERC-containing RNP (Figure 7F, bottom). Together with its associated proteins GAR1, NOP10 and NHP2, dyskerin directly binds TERC at its 3′ H/ACA motif (Mitchell et al., 1999b; Dragon et al., 2000; Pogacic et al., 2000; Fu and Collins, 2007). Deletion of the H/ACA sequence or mutation of dyskerin leads to reduced TERC levels. Diminished levels of TERC in patients with dyskerin mutations accounts for the reduced telomerase activity and markedly shorter telomeres seen in the X-linked form of dyskeratosis congenita (Mitchell et al., 1999b). Our data showing that pontin and reptin interact with dyskerin indicate that these proteins work together to assemble and stabilize the TERC RNP and this step requires pontin's ATPase activity. The loss of TERC seen with depletion of pontin, reptin or dyskerin strongly supports our biochemical experiments showing interactions among these proteins and indicate that intact function of a pontin/reptin/dyskerin module is required for assembly of a TERC-dyskerin RNP.

In addition to this function, pontin and reptin interact with TERT, suggesting that pontin and reptin also serve to assemble or remodel a telomerase complex containing TERT (Figure 7F, top). This process may occur in a stepwise fashion in which pontin and reptin facilitate assembly of TERT with a TERC-dyskerin RNP, or remodel this maturing telomerase complex. The low catalytic activity of purified pontin/reptin/TERT complexes suggest that they may represent a pre-telomerase complex that requires additional factors or remodeling for conversion to a mature telomerase complex. After assembly, pontin and reptin may dissociate from a mature TERT-TERC-dyskerin complex, which appears to comprise the majority of in vitro telomerase activity because dyskerin immunoprecipitation depleted TRAP activity from extracts. Alternatively, pontin and reptin may remain associated with a telomerase holoenzyme capable of acting on telomeres in vivo, but unable to generate high level catalytic activity on simple oligonucleotide subtrates in vitro (Figure 7).

The low catalytic activity of pontin/reptin complexes likely explains why they were not identified in a recent telomerase purification strategy that exploited the ability of telomerase to bind and extend an oligonucleotide substrate as a purification step (Cohen et al., 2007). Our data indicate that TERT protein exists in at least two different complexes. The TERT/TERC/dyskerin complex has high telomerase catalytic activity, whereas the pontin/reptin/TERT complex exhibits much lower enzymatic activity. Although direct comparison is limited by potential variables such as efficiency of extraction, it is striking that the amounts of endogenous TERT associated with pontin and dyskerin are comparable, indicating that the TERT/pontin/reptin complex is not a rare, transient intermediate. Its abundance relative to the TERT/TERC/dyskerin complex may reflect the fact that the pontin/reptin/TERT complex requires significant time for assembly or is a target for regulation. Consistent with this idea, the association of TERT with pontin and reptin is remarkably cell cycle dependent, appearing in S phase and diminishing in G2, M and G1 phases. The S phase-dependence of the association between TERT and pontin/reptin suggests that the telomerase complex may be assembled de novo during each S phase. Alternatively, or in addition, pontin and reptin may direct TERT into complexes with other molecules that could explain how TERT activates quiescent epidermal stem cells (Sarin et al., 2005; Flores et al., 2005).

A critical role for assembly in dynamic macromolecular complexes

Pontin and reptin are associated with diverse nuclear multi-subunit complexes, including chromatin remodeling complexes, transcription factors and small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins (snoRNPs). In yeast, pontin/reptin orthologues Rvb1p/Rvb2p are members of the 12-subunit Ino80 chromatin remodeling complex (Shen et al., 2000). When Rvb2p is depleted, Ino80 complexes lack not only Rvb1p and Rvb2p but also another core subunit Arp5p, and these “incomplete” complexes can no longer remodel nucleosomes in vitro (Jonsson et al., 2004). In mammals, pontin and reptin were identified as components of the box C/D class of snoRNPs, which catalyze ribose methylation of target ribosomal and spliceosomal RNAs. Pontin and reptin have affinity for box C/D scaffolds (Newman et al., 2000), associate with “maturing” U3 snoRNPs, and are required for U3 snoRNA accumulation, as we confirmed here (Watkins et al., 2004). Thus, pontin and reptin may serve to assemble diverse complexes by interacting with components specific to each complex, as it does with dyskerin and TERT in the telomerase RNP.

A role for pontin and reptin in telomerase RNP assembly is consistent with the function of other AAA+ ATPases in dynamic nuclear complexes. For example, the complex that forms at replication origins comprises 14 proteins, ten of which are AAA+ ATPases. During each G1 phase, these proteins assemble the “pre-replication complex” through sequential ATP binding and hydrolysis events, resulting in a licensed origin prepared for DNA replication in S phase (Bell and Dutta, 2002). Stepwise assembly is particularly relevant for RNP complexes, as illustrated by the example of small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), which require the heptameric Sm proteins for efficient assembly (Yong et al., 2004). Similarly, the telomerase RNA component also requires Sm proteins for assembly in yeast and in humans (Seto et al., 1999; Fu and Collins, 2006). Interestingly, complex assembly has emerged as an important theme in the regulation of telomerase in the ciliate Tetrahymena, which requires a La-related protein that binds the telomerase RNA component for efficient assembly and activity (Witkin and Collins, 2004; Prathapam et al., 2005). Thus, the need for an ordered, stepwise assembly of telomerase is likely conserved across species, although the specific proteins that mediate this dynamic process may differ when comparing species separated by large evolutionary distances.

Telomerase and disease: a new enzyme activity required for telomerase

Telomerase is intimately associated with human cancer and therefore has been considered a potential target for anti-cancer therapy. However, few high affinity inhibitors of telomerase have thus far been identified, perhaps reflecting difficulty in targeting the enzyme's reverse transcriptase function. Our data suggest that the development of pontin or reptin inhibitors may serve as highly effective therapeutic drugs targeting telomerase. Inhibiting pontin or reptin catalytic function would mimic the effects of shRNA in imparing telomerase RNP biogenesis, thereby circumventing the empiric difficulties in targeting the active site of the telomerase reverse transcriptase. Although dyskeratosis congenita has been linked to mutations in dyskerin, TERC or TERT, the causal mutation has yet to be identified in many families (Vulliamy et al., 2006). Our data suggest that mutations in pontin or reptin may also be found in patients with dyskeratosis congenita, aplastic anemia or pulmonary fibrosis. The essential roles for pontin and reptin in telomerase assembly suggest important future studies for these ATPases in human health and disease.

Experimental Procedures

TERT complex purification and mass spectrometry

A detailed description of the purification procedure is included in the supplementary information. In brief, lysates from HeLa S3 cells expressing AH3-TERT were bound to rabbit IgG resin (Sigma), washed extensively, and eluted overnight with TEV protease. The next day, eluants were precleared with mouse IgG resin and then bound again to 12CA5 anti-HA conjugated resin. After extensive washing, the anti-HA resin was eluted and precipitated for mass spectrometry. All steps were performed at 4°C. Protein identification using mass spectrometry is detailed in the supplementary information.

Small scale cell culture, transfections, and transductions

Asynchronous adherent HeLa S3 cultures were grown in DMEM/5% newborn calf serum/1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS); 293T and U2OS cells were grown in DMEM/10% bovine growth serum/1% PS. Details for cell synchronization and for all constructs are provided in the supplementary information. Retroviruses were generated by cotransfecting plasmids encoding RSV(Gag+Pol), VSV-G, and the retroviral expression or shRNA plasmids (Dickins et al., 2005) into 293T cells using calcium phosphate precipitation. To generate Flag-pontin+shRNA and Flag-reptin+shRNA cell lines, HeLa S3 cells were first transduced with shRNA-resistant Flag-pontin or Flag-reptin in the pMGIB vector, selected with blasticidin S, transduced with the LMP shRNA vector, and finally selected with puromycin. Transient transfections into 293T cells were done using standard calcium phosphate precipitation, which were harvested after 60-72 hr for co-immunoprecipitation analysis.

Co-immunoprecipitations, western blots, and northern blots

Cells were lysed in NP40 buffer (25mM HEPES-KOH, 150mM KCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP40, 5mM 2ME, pH 7.5 supplemented with protease inhibitors) for 15-30 min on ice. Extracts clarified by centrifugation for 16,000g for 10 min were quantified by Bradford assay and immunoprecipitated with 10-15uL M2 anti-Flag resin (Sigma) for 1-2 hr at 4°C. Where indicated, RNase A, ethidium bromide, or DNase I was included during the incubation at 0.1mg/mL. Resins were then washed 5 times for 10 min each with 1mL NP40 buffer, boiled in Laemmli sample buffer, and fractionated by SDS-PAGE. Primary antibody concentrations for western blots and details of polyclonal antibody generation are given in the supplementary information. For northern blots, one-half the resin (into which a recovery control RNA was spiked to control for differential recovery in subsequent steps) was extracted with phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol and precipitated with glycogen carrier. RNA pellets were boiled in formamide loading buffer, loaded onto 5% polyacrylamide-8M urea gels, transferred to Hybond N+ (Amersham), and hybridized with 32P-α-dCTP labeled full-length hTR, U3, or U1 probe in Ultrahyb (Ambion). For total RNA analysis, 1ug of Trizol (Invitrogen) extracted RNA was used. Methods for glycerol gradient sedimentation, TRAP assays, immunofluorescence, and telomere length analysis are detailed in the supplementary information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Kornberg, Y. Takagi, P. Jackson, G. Crabtree, M. Nachury, R. Verdun, J. Karlseder, T. Wang, G. Attardi, L. Attardi, J. Sage, A. Brunet, and K. McCann for helpful discussions and insights. We thank R. Dickins and S. Lowe for providing shRNA plasmids. A.S.V. was supported by Medical Scientist Training Program Grant GM07365. P.J.M. was supported by R01 CA106995. This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the NCI, NIH, under Contract NO1-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organization imply endorsement by the United States Government. This work was supported by grants CA111691 and CA125453 from the NCI and by a grant from the American Federation of Aging Research/Pfizer to S.E.A.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allsopp RC, Morin GB, DePinho R, Harley CB, Weissman IL. Telomerase is required to slow telomere shortening and extend replicative lifespan of HSCs during serial transplantation. Blood. 2003;102:517–520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armanios M, Chen JL, Chang YP, Brodsky RA, Hawkins A, Griffin CA, Eshleman JR, Cohen AR, Chakravarti A, Hamosh A, Greider CW. Haploinsufficiency of telomerase reverse transcriptase leads to anticipation in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15960–15964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508124102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SP, Dutta A. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:333–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell. 2001;106:661–673. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SB, Graham ME, Lovrecz GO, Bache N, Robinson PJ, Reddel RR. Protein composition of catalytically active human telomerase from immortal cells. Science. 2007;315:1850–1853. doi: 10.1126/science.1138596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins K. The biogenesis and regulation of telomerase holoenzymes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:484–494. doi: 10.1038/nrm1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2100–2110. doi: 10.1101/gad.1346005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickins RA, Hemann MT, Zilfou JT, Simpson DR, Ibarra I, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Probing tumor phenotypes using stable and regulated synthetic microRNA precursors. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1289–1295. doi: 10.1038/ng1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragon F, Pogacic V, Filipowicz W. In vitro assembly of human H/ACA small nucleolar RNPs reveals unique features of U17 and telomerase RNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3037–3048. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3037-3048.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores I, Cayuela ML, Blasco MA. Effects of telomerase and telomere length on epidermal stem cell behavior. Science. 2005;309:1253–1256. doi: 10.1126/science.1115025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D, Collins K. Human telomerase and Cajal body ribonucleoproteins share a unique specificity of Sm protein association. Genes Dev. 2006;20:531–536. doi: 10.1101/gad.1390306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D, Collins K. Purification of human telomerase complexes identifies factors involved in telomerase biogenesis and telomere length regulation. Mol Cell. 2007;28:773–785. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant P. Control of transcription by Pontin and Reptin. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt SE, Aisner DL, Baur J, Tesmer VM, Dy M, Ouellette M, Trager JB, Morin GB, Toft DO, Shay JW, et al. Functional requirement of p23 and Hsp90 in telomerase complexes. Genes Dev. 1999;13:817–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jady BE, Richard P, Bertrand E, Kiss T. Cell cycle-dependent recruitment of telomerase RNA and Cajal bodies to human telomeres. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:944–954. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson ZO, Jha S, Wohlschlegel JA, Dutta A. Rvb1p/Rvb2p recruit Arp5p and assemble a functional Ino80 chromatin remodeling complex. Mol Cell. 2004;16:465–477. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Kim B, Cai L, Choi HJ, Ohgi KA, Tran C, Chen C, Chung CH, Huber O, Rose DW, et al. Transcriptional regulation of a metastasis suppressor gene by Tip60 and beta-catenin complexes. Nature. 2005;434:921–926. doi: 10.1038/nature03452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Blasco MA, Gottlieb GJ, Horner JW, 2nd, Greider CW, DePinho RA. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature. 1998;392:569–574. doi: 10.1038/33345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loayza D, De Lange T. POT1 as a terminal transducer of TRF1 telomere length control. Nature. 2003;423:1013–1018. doi: 10.1038/nature01688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcand S, Brevet V, Mann C, Gilson E. Cell cycle restriction of telomere elongation. Curr Biol. 2000;10:487–490. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone A, Walne A, Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita: telomerase, telomeres and anticipation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias PM, Gorynia S, Donner P, Carrondo MA. Crystal structure of the human AAA+ protein RuvBL1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38918–38929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier UT. The many facets of H/ACA ribonucleoproteins. Chromosoma. 2005;114:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00412-005-0333-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JR, Cheng J, Collins K. A box H/ACA small nucleolar RNA-like domain at the human telomerase RNA 3′ end. Mol Cell Biol. 1999a;19:567–576. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JR, Wood E, Collins K. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 1999b;402:551–555. doi: 10.1038/990141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman DR, Kuhn JF, Shanab GM, Maxwell ES. Box C/D snoRNA-associated proteins: two pairs of evolutionarily ancient proteins and possible links to replication and transcription. Rna. 2000;6:861–879. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200992446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogacic V, Dragon F, Filipowicz W. Human H/ACA small nucleolar RNPs and telomerase share evolutionarily conserved proteins NHP2 and NOP10. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9028–9040. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.9028-9040.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prathapam R, Witkin KL, O'Connor CM, Collins K. A telomerase holoenzyme protein enhances telomerase RNA assembly with telomerase reverse transcriptase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:252–257. doi: 10.1038/nsmb900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottbauer W, Saurin AJ, Lickert H, Shen X, Burns CG, Wo ZG, Kemler R, Kingston R, Wu C, Fishman M. Reptin and pontin antagonistically regulate heart growth in zebrafish embryos. Cell. 2002;111:661–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin KY, Cheung P, Gilison D, Lee E, Tennen RI, Wang E, Artandi MK, Oro AE, Artandi SE. Conditional telomerase induction causes proliferation of hair follicle stem cells. Nature. 2005;436:1048–1052. doi: 10.1038/nature03836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnapp G, Rodi HP, Rettig WJ, Schnapp A, Damm K. One-step affinity purification protocol for human telomerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3311–3313. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.13.3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto AG, Zaug AJ, Sobel SG, Wolin SL, Cech TR. Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase is an Sm small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle. Nature. 1999;401:177–180. doi: 10.1038/43694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Mizuguchi G, Hamiche A, Wu C. A chromatin remodelling complex involved in transcription and DNA processing. Nature. 2000;406:541–544. doi: 10.1038/35020123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smogorzewska A, van Steensel B, Bianchi A, Oelmann S, Schaefer MR, Schnapp G, de Lange T. Control of human telomere length by TRF1 and TRF2. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1659–1668. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1659-1668.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson RL, Ziegler TD, Supakorndej T, Terns RM, Terns MP. Cell cycle-regulated trafficking of human telomerase to telomeres. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:955–965. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Goldman F, Dearlove A, Bessler M, Mason PJ, Dokal I. The RNA component of telomerase is mutated in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 2001;413:432–435. doi: 10.1038/35096585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy TJ, Marrone A, Knight SW, Walne A, Mason PJ, Dokal I. Mutations in dyskeratosis congenita: their impact on telomere length and the diversity of clinical presentation. Blood. 2006;107:2680–2685. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Podell ER, Zaug AJ, Yang Y, Baciu P, Cech TR, Lei M. The POT1-TPP1 telomere complex is a telomerase processivity factor. Nature. 2007;445:506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature05454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins NJ, Lemm I, Ingelfinger D, Schneider C, Hossbach M, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R. Assembly and maturation of the U3 snoRNP in the nucleoplasm in a large dynamic multiprotein complex. Mol Cell. 2004;16:789–798. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrich SL, Pruzan R, Ma L, Ouellette M, Tesmer VM, Holt SE, Bodnar AG, Lichtsteiner S, Kim NW, Trager JB, et al. Reconstitution of human telomerase with the template RNA component hTR and the catalytic protein subunit hTRT. Nat Genet. 1997;17:498–502. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenz C, Enenkel B, Amacker M, Kelleher C, Damm K, Lingner J. Human telomerase contains two cooperating telomerase RNA molecules. Embo J. 2001;20:3526–3534. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkin KL, Collins K. Holoenzyme proteins required for the physiological assembly and activity of telomerase. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1107–1118. doi: 10.1101/gad.1201704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YL, Dudognon C, Nguyen E, Hillion J, Pendino F, Tarkanyi I, Aradi J, Lanotte M, Tong JH, Chen GQ, Segal-Bendirdjian E. Immunodetection of human telomerase reverse-transcriptase (hTERT) re-appraised: nucleolin and telomerase cross paths. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2797–2806. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H, Liu D, Wan M, Safari A, Kim H, Sun W, O'Connor MS, Songyang Z. TPP1 is a homologue of ciliate TEBP-beta and interacts with POT1 to recruit telomerase. Nature. 2007;445:559–562. doi: 10.1038/nature05469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong J, Wan L, Dreyfuss G. Why do cells need an assembly machine for RNA-protein complexes? Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.