Abstract

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) of isolated lignins from an Arabidopsis mutant deficient in ferulate 5-hydroxylase (F5H) and transgenic plants derived from the mutant by overexpressing the F5H gene has provided detailed insight into the compositional and structural differences between these lignins. Wild-type Arabidopsis has a guaiacyl-rich, syringyl-guaiacyl lignin typical of other dicots, with prominent β-aryl ether (β–O–4), phenylcoumaran (β–5), resinol (β–β), biphenyl/dibenzodioxocin (5–5), and cinnamyl alcohol end-group structures. The lignin isolated from the F5H-deficient fah1–2 mutant contained only traces of syringyl units and consequently enhanced phenylcoumaran and dibenzodioxocin levels. In fah1–2 transgenics in which the F5H gene was overexpressed under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, a guaiacyl-rich, syringyl/guaiacyl lignin similar to the wild type was produced. In contrast, the isolated lignin from the fah1–2 transgenics in which F5H expression was driven by the cinnamate 4-hydroxylase promoter was almost entirely syringyl in nature. This simple lignin contained predominantly β-aryl ether units, mainly with erythro-stereochemistry, with some resinol structures. No phenylcoumaran or dibenzodioxocin structures (which require guaiacyl units) were detectable. The overexpression of syringyl units in this transgenic resulted in a lignin with a higher syringyl content than that in any other plant we have seen reported.

Keywords: transgenic plants, mutant, syringyl lignin, heteronuclear single quantum coherenceHSQC, guaiacyl lignin

The biotechnological manipulation of lignin content and/or structure in plants is seen as a route to improving the use of plant cell wall polysaccharides in various agricultural and industrial processes. The aims of these efforts range from enhancing cell wall digestibility in ruminants to reducing the energy demand and negative environmental impacts of chemical pulping and bleaching required in the papermaking process. To achieve these goals, many researchers (1–3) have down-regulated the expression of genes of the monolignol biosynthetic pathway in attempts to decrease lignin deposition. This approach has sometimes had negative side effects, including the collapse of tracheary elements under the tension generated by transpiration. One of the most desirable strategies for modifying lignin is to produce a less crosslinked, syringyl-rich lignin. It is hoped that this modified lignin would have improved industrial and/or agricultural properties, yet remain fully functional in planta.

Through the identification of the fah1–2 mutant, it has been shown that ferulate 5-hydroxylase (F5H) activity is required for syringyl lignin deposition in Arabidopsis (4). The Arabidopsis F5H gene was subsequently cloned by T-DNA tagging (5). F5H expression was shown to be rate limiting for syringyl lignin accumulation by overexpression of the gene in the fah1–2 mutant background (6). The lignin in transgenic plants, in which the F5H gene was expressed under the control of cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter, had a syringyl lignin monomer content of 30 mol % compared with approximately 20 mol % in the wild type. In addition, the tissue specificity of syringyl lignin deposition was abolished, indicating that F5H is the enzyme that quantitatively and qualitatively regulates syringyl lignin content. Meyer et al. (6) used the cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H) promoter to overexpress the F5H gene. In contrast to the relatively modest results obtained with the CaMV 35S promoter, transgenic plants carrying C4H–F5H constructs deposited lignin in which syringyl monomers comprised over 90 mol % of the total subunits.

Despite its presumed random and heterogeneous nature, the complex lignin polymer discloses many of its intimate structural details to diagnostic NMR experiments (7, 8). 13C NMR was established early as a method for detailed structural characterization, aided by the almost exact agreement between chemical shifts of carbons in good low-molecular-mass model compounds and in the polymer (9, 10). Although this correspondence cannot generally be expected for proton NMR, good lignin model compounds and their counterpart units in the polymer also closely match proton NMR chemical shifts (11–13). Despite the broad featureless one-dimensional (1D) proton spectra, which have nevertheless allowed substantive interpretation (14), homo- and hetero-nuclear, two- and three-dimensional (2D and 3D) spectra are rich in information that is extremely useful in polymer characterization (7, 8). NMR has already proven invaluable in revealing structural aspects of other lignin-biosynthetic-pathway mutants and transgenics (15, 16).

To date, the characterization of lignin in wild-type Arabidopsis, the fah1–2 mutant, and the 35S–F5H and C4H–F5H transgenics (6) has employed only nitrobenzene oxidation and analysis by a relatively new derivatization-followed-by-reductive-cleavage (DFRC) method (17–19). These techniques permit the analysis of only the releasable units of the lignin polymer, and are thus not fully informative. In this study, we sought to identify more completely the nature and extent of the changes to lignin composition in these plants and in their structure by potent NMR methods.

Materials and Methods

General.

All reagents were purchased from Aldrich. The 1H, 13C, and 2D NMR spectra were taken on a Bruker DRX-360 instrument fitted with a 5-mm 1H/broadband gradient probe with inverse geometry (proton coils closest to the sample). The conditions for all samples were ≈40 mg of isolated lignin in 0.4 ml of acetone-d6, with the central solvent peak as internal reference (δH 2.04, δC 29.80). Experiments used were standard Bruker implementations of gradient-selected versions of inverse (1H-detected) heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC), HSQC-total correlation spectroscopy (HSQC-TOCSY), and heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) experiments. The TOCSY spin lock period was 100 ms; the HMBC experiments used a 100-ms long-range coupling delay. Carbon/proton designations are based on conventional lignin numbering [see structures in Fig. 1 (Lower) and Fig. 2 (Bottom)]. Lignin sub-structure numbering and colors are the same as those used in a recent book (7).

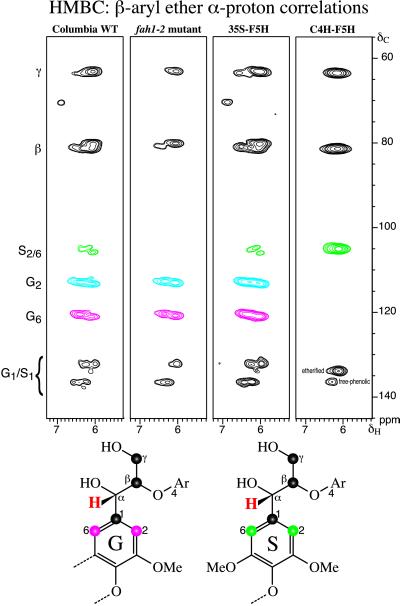

Figure 1.

Gradient-selected 2D HMBC sub-spectra showing α-proton correlations in β-aryl ether units A. The syringyl/guaiacyl compositional changes are readily apparent in these spectra. The Columbia wild-type and 35S–F5H lignins are guaiacyl-rich syringyl/guaiacyl copolymers. In the fah1–2 mutant, syringyl units are almost completely absent. When F5H is expressed under the control of the C4H promoter, the lignin that is deposited is composed almost exclusively of syringyl units. Structures (bottom) represent the five carbons that are within three bonds of proton H-α (red), showing the HMBC correlations and the lignin numbering conventions. G, Guaiacyl; S, syringyl.

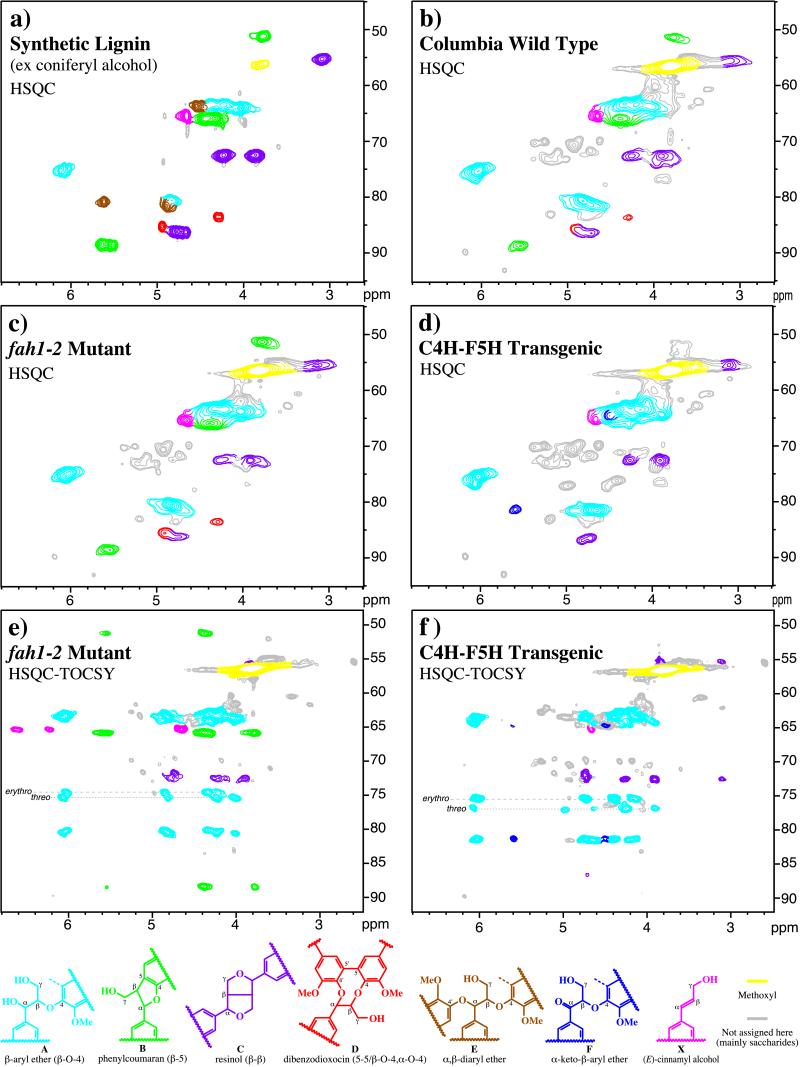

Figure 2.

(a–d) Gradient-selected 2D HSQC spectra of Arabidopsis lignins from coniferyl alcohol synthetic lignin (a); wild type (b); the fah1–2 mutant (c); and the C4H–F5H transgenics (d). (e and f) Gradient-selected 2D HSQC-TOCSY spectra from the fah1–2 mutant (e) and the C4H–F5H transgenic (f). Standard lignin numbering is shown (see structures in Fig. 1). The standardized color scheme is from ref. 7. (Bottom) Lignin structures are: A, β-aryl ether (β–O–4); B, phenylcoumaran (β–5); C, resinol (β–β); D, dibenzodioxocin (5–5 and β–O–4/α–O–4); E, α, β-diaryl ether (β–O–4/α–O–4); F, α-keto-β-aryl ethers; and X, cinnamyl alcohols. (For more detailed assignments, see ref. 7). Note: the NMR data for compound F will appear in the next release of our NMR database (available online at http://www.dfrc.ars.usda.gov/software.html).

Plant Materials and Lignin Isolation.

Plant growth conditions, the fah1–2 mutant, as well as the 35S–F5H and C4H–F5H fah1–2 transgenic lines were previously described (6). Stem sections of 8-week-old plants were separated, immediately lyophilized, and packed in vacuum-sealed bags. Plant tissue was allowed to rehydrate before being ground in liquid nitrogen by mortar and pestle. Lignin isolations were essentially as described previously (15, 20). Soluble phenolics, carbohydrates, and other components were removed by successive extractions with water, methanol, acetone, and chloroform. Most of the colored material was removed by the water and methanol extraction cycles. Klason lignin levels were measured as described previously on a sample of the extracted tissue (21). The ground stem material was then ball-milled, treated with crude cellulases, and extracted with 96:4 dioxane:water. The final yields of milled isolated lignin were (by weight) 17.4% of the lignin from the fah1–2 mutant, 27.5% of the lignin from the C4H–F5H transgenic, 29.7% of the lignin from the 35S–F5H transgenic, and 24.6% of the lignin from the wild type. After NMR of underivatized lignins (data not shown), the isolated lignins were acetylated overnight with acetic anhydride/pyridine, and the solvents were removed by co-evaporation with 95% ethanol. Traces of ethanol were removed by co-evaporation with acetone, followed by evaporation at reduced pressure [150 mtorr (approximately 20 Pa)] for several hours. The acetylated lignins were dissolved in acetone-d6 (0.4 ml) for NMR.

Results and Discussion

Syringyl/Guaiacyl Nature from HMBC Spectra.

The results of the previous chemical analysis (6) of normal, mutant, and transgenic lignins were readily verified by the NMR spectra. Perhaps most clearly revealing were sections of the long-range 13C–1H correlation (gradient-enhanced HMBC) experiments. Fig. 1 shows the correlations between the α-protons of the major β-aryl ether units in lignins from the wild type, the fah1–2 mutant, as well as the 35S–F5H and the C4H–F5H transgenics. As expected, the α-protons correlate with carbons β and γ of the side chain and carbons 1, 2, and 6 of the aromatic rings; all of these carbons are within three bonds of the α-proton. What makes these correlation spectra useful is that the equivalent syringyl C-2/C-6 carbons, resonating at ≈105 ppm, are well separated from their guaiacyl counterparts (for which C-2 and C-6 are different, at ≈113 and ≈120 ppm). Thus, it is immediately clear that the wild-type control contains guaiacyl and syringyl (β-ether) units, with guaiacyl units predominating. The fah1–2 mutant has almost no syringyl component; it is barely detectable at lower contour levels. These observations are consistent with data that indicate that F5H mRNA is below detectable limits in the fah1–2 mutant (5). As was previously shown by nitrobenzene oxidation and DFRC analysis (6), the lignin of the 35S–F5H line is a guaiacyl/syringyl copolymer. The HMBC spectra show no significant differences between the wild type and 35S–F5H transgenic lignins. In contrast, the HMBC spectrum of lignin from the C4H–F5H transgenic line deviates strongly from that of the wild type. The lignin is extremely syringyl-rich. Only weak guaiacyl peaks could be discerned at lower levels. The guaiacyl level in the isolated lignin is crudely estimated at <3%, certainly <5%.

A few natural lignins are syringyl-rich, with nitrobenzene syringaldehyde:vanillin ratios reaching about 6:1 in kenaf bast-fiber isolated lignins (22), up to 5.2:1 in some hardwoods (23, 24) and a thesis (25) describes an 8.4:1 ratio. The syringaldehyde:vanillin ratio in the best C4H–F5H transgenic line was previously reported as approximately 9:1 (6), higher than that in any other plant previously described. In fact, the GC peak co-eluting with, and therefore assumed to be, vanillin in this line was subsequently determined by GC-MS not to be vanillin. Consequently, the nitrobenzene results underestimated the syringyl:guaiacyl ratio. If, indeed, the guaiacyl level is of the order of 3%, implying a syringyl:guaiacyl ratio of over 30, it is substantially higher than any reported values.

More sensitive determinations of these values, in the whole cell wall material and in the lignin isolates, are needed. In comparing the isolated lignins from the C4H–F5H transgenic with that from kenaf (22), it is clear that this transgenic Arabidopsis has a significantly lower guaiacyl content. Considering that the wild-type lignin contains a large proportion of guaiacyl residues, the overexpression of F5H is therefore strikingly effective at diverting the monolignol pool almost entirely into sinapyl alcohol. The efficacy of this strategy has recently been partially explained by the finding that F5H is a multifunctional hydroxylase and is thus capable of redirecting several guaiacyl intermediates toward syringyl lignin biosynthesis (26, 27). Coniferaldehyde is the preferred substrate for “F5H,” suggesting that “coniferaldehyde 5-hydroxylase” may be a better descriptor (26, 27); ferulate is slower reacting (26, 27) and is not metabolized in the presence of the aldehyde (27).

There is also in vitro (26) and in vivo (28) evidence for the operation of a pathway that converts coniferyl alcohol to sinapyl alcohol (without regression to the aldehyde). It should be noted that the lignin content of the C4H–F5H line was lower (Klason lignins of approximately 11% vs. approximately 19% for the other transgenics and 17% for the wild type). It is difficult to produce high molecular mass lignins from only sinapyl alcohol in vitro, and these data may indicate that it is also difficult in planta. Syringyl units have fewer radical coupling sites available, are consequently involved in fewer structures, and have less branching. Syringyl-rich lignins are therefore more easily degraded and extracted. The fraction of the lignin that could be isolated from the C4H–F5H transgenic (27.5%) was higher than that from the wild type and the guaiacyl-only fah1–2 mutant, the latter of which was the lowest (17.4%). Solution-state NMR methods, although they provide an analysis of condensed structures not released by degraditive techniques, can only analyze the solvent-soluble component. The NMR-accessible component ranged from 17% to 30% of the total lignin in these samples.

HSQC and HSQC-TOCSY Spectra.

Further structural insights are available from 2D short-range 13C–1H correlation spectra [gradient-enhanced HSQC (29, 30)] and correlation spectra in which a carbon correlates with its attached proton and other protons coupled to that attached proton [gradient-enhanced HSQC-TOCSY (31)]. Although the HSQC-TOCSY spectra are easier to interpret because the extended correlations allow individual lignin subunits to be readily identified, the HSQC spectra are more quantitatively accurate. In HSQC spectra, a proton correlates with its directly attached carbon. For example, the structure C α-proton at ≈4.75 ppm correlates with the α-carbon at 86.2 ppm; the β-proton at 3.1 ppm correlates with the β-carbon at 55.2 ppm; and the γ-carbon at ≈72.4 ppm correlates with its two attached γ-protons at 3.90 and 4.27 ppm. In an HSQC-TOCSY spectrum, the structure C γ-carbon at 72.4 ppm correlates with all of the protons in the side chain of unit C (the α-proton at 4.75 ppm, the two γ-protons at 3.90 and 4.27 ppm, and the β-proton at 3.10 ppm; see Fig. 2f for the best example). The best combination of interpretability and accuracy comes from examining both types of spectra.

In general, the HSQC data shown in Fig. 2 b–d are typical of normal lignins from a variety of plants (7), but also include a few saccharide contaminants. There appear to be no significant abnormal components as have been seen with other mutants and transgenics (7, 15, 16), although, as described later, an α-keto component is observed in the syringyl-rich C4H–F5H lignin. In the wild-type lignin (Fig. 2b), phenylcoumaran (β–5, B) units are well represented and are indicative of the presence of guaiacyl components. Phenylcoumaran units arise during lignification from coupling at the 5-position of a guaiacyl oligomer/polymer bearing a free phenolic hydroxyl with coniferyl or sinapyl alcohol at its β-position. Dibenzodioxocins (D) are recently discovered structures resulting from reaction of 5–5-coupled guaiacyl units with a monolignol (32, 33). Their presence in the lignin of wild-type Arabidopsis is also consistent with the presence of guaiacyl components. Ether-linked units (β–O–4, A) predominate in all Arabidopsis lignins, and resinols (β–β, C) are also well represented. Essentially no α,β-diether E is detectable. All of these structures are seen more clearly in spectra from a synthetic lignin derived from coniferyl alcohol (Fig. 2a).

In the fah1–2 mutant, the lignin is composed almost solely of guaiacyl subunits. This is reflected in a more substantial β–5 (B) component, more dibenzodioxocins (D), and fewer resinols (C). Consistent with previous biochemical analysis that indicated that the 35S–F5H transgene complements the fah1–2 mutant phenotype, the lignin of the 35S–F5H line is similar to the wild type (data not shown).

The HSQC spectrum of the C4H–F5H lignin (Fig. 2d) indicates that it is almost purely derived from syringyl monomers. As such, the β–β (C) content is elevated, and there are essentially no β–5 (B) or dibenzodioxocin (D) units. The contour at 81.1/5.6 ppm was initially thought to be the α,β-diaryl ether E, because of its position relative to the synthetic lignin spectrum (Fig. 2a). This was surprising because syringyl units might not be expected readily to attack quinone methide intermediates to form α,β-diaryl ethers. Further analysis revealed that this peak represents instead a component occasionally seen in high-syringyl lignins. In its long-range 13C–1H correlation (HMBC) spectrum, the proton at δ 5.6 clearly correlated with carbons at 64.5 (Cγ) and 194.8 (a ketone carbonyl carbon). Comparison with model compounds, e.g., the (acetylated) syringyl-syringyl keto-model 3,4′-diacetoxy-3′,5′-dimethoxy-2-(2, 6-dimethoxy-4-methylphenoxy)propiophenone, which is compound #246 in the NMR Database of Lignin and Cell Wall Model Compounds,¶ indicated that the component was indeed the syringyl α-keto-β-aryl ether F. This structure has been noted previously in hardwood lignins and attributed to the lower oxidation potential of syringyl units (34); such ketones may be formed during lignin isolation, particularly in the ball-milling step (35). In our samples, the component was not readily observed except in the most syringyl-rich sample.

The HSQC-TOCSY data (Fig. 2 e and f) supplement the HSQC data and make it easier to authenticate assignments. In experiments of this type, a carbon correlates with directly attached protons and others within the same proton-coupling network. In general, all side-chain protons are within the same coupling network for any lignin structural unit; however, the intensities observed depend on proton–proton coupling constants as well as on other factors—so all correlations are not seen, and intensities vary. The major additional data revealed by the HSQC-TOCSY spectra relate to the stereochemistry of β-ether units A. Consistent with its syringyl-rich nature (22, 36), β-ether units A in the C4H–F5H lignin (Fig. 2f) are ≈80% of erythro-stereochemistry. Both threo- and erythro-units are approximately equally represented in guaiacyl lignins, such as softwoods and the fah1–2 mutant (Fig. 2e).

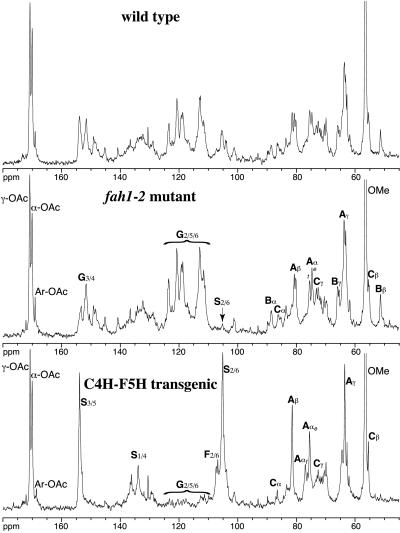

1D 13C NMR Spectra.

The syringyl–guaiacyl nature of lignins is also easily recognized in 1D 13C (Fig. 3) and even in 1H spectra (data not shown). As noted above, syringyl units have symmetry. Their protonated aromatic 2/6-carbons are at ≈105 ppm, and their quaternary 3/5 carbons are at ≈154 ppm. This symmetry separates them from their guaiacyl counterparts, in which protonated carbons 2, 5, and 6 range from ≈110 to 125 ppm, although some overlap is seen with quaternary carbons 3 and 4, which range from ≈145 to 154 ppm. The 1D spectra (see the labeled prominent peaks or regions in Fig. 3) show the differences between the lignins noted above. The syringyl-rich C4H–F5H spectrum is particularly simple, being composed almost entirely of β-aryl ether units A, mostly with erythro-stereochemistry, and resinols C. The α-keto structures F can most readily be seen from the shoulder peaks to the left (≈107 ppm) of the main S2/6 carbons (≈105 ppm). As noted from 2D spectra, the fah1–2 mutant spectrum has syringyl peaks that are at the limits of detection (denoted by arrow in Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

1D 13C NMR spectra of Arabidopsis lignins from: the wild type (Top); the fah1–2 mutant (Middle); and the C4H–F5H transgenic (Bottom). Major peaks are shown with their assignments; the letters A–F correspond to structures A–F as in Fig. 2. G represents a general guaiacyl unit and S represents a general syringyl unit. e, erythro-isomer; t, threo-isomer; oligosaccharides are present in these lignins.

Conclusions

The NMR data presented here are consistent with previous biochemical data that characterized F5H as a key regulatory point in the determination of lignin monomer composition (6). The near absence of syringyl unit resonances in the lignin of the fah1–2 mutant provides further evidence that F5H activity is required for syringyl lignin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Similarly, the domination of the NMR spectra by peaks attributable to sinapyl alcohol-derived subunits indicates that overexpression of the gene encoding F5H, under the control of the C4H promoter, leads to a lignin that is almost exclusively syringyl in nature.

Our results demonstrate that the manipulation of the monolignol supply for the purposes of changing lignin subunit composition has been extremely successful in Arabidopsis. Lignin syringyl-guaiacyl compositions range from almost 100% guaiacyl in the F5H-deficient fah1–2 mutant to nearly 100% syringyl in the best F5H-up-regulated transgenic, a significantly higher percentage than that seen in other plants. The strategy outlined here is a crucial step in the ongoing attempt to produce high syringyl lignins in hardwoods and, possibly, to introduce its deposition into softwoods.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Larry Landucci and John Obst for discussions regarding syringyl lignins and syringyl:guaiacyl ratios, and we thank Sally A. Ralph for the syringyl α-keto-β-ether model compound used for authentication of structures F. This research was supported by a grant (DE-FG02-94ER20138) to C.C. from the Division of Energy Biosciences, U.S. Department of Energy; and by grants (96-35304 and 99-02351) to J.R. from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)–National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program. The USDA-Agricultural Research Service funded the NMR instrumentation upgrades essential to this work.

Abbreviations

- 1D

one-dimensional

- 2D

two-dimensional

- DFRC

derivatization followed by reductive cleavage

- F5H

ferulate 5-hydroxylase

- HMBC

heteronuclear multiple bond correlation

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- TOCSY

total correlation spectroscopy

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Ralph, S. A., Ralph, J., Landucci, W. L. & Landucci, L. L. (1998) Data available online at: http://www.dfrc.ars.usda.gov/software.html.

References

- 1.Boudet A M, Grima-Pettenati J. Mol Breed. 1996;2:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whetten R W, MacKay J J, Sederoff R R. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998;49:585–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudet A-M. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapple C C S, Vogt T, Ellis B E, Sommerville C R. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1413–1424. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.11.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer K, Cusumano J C, Somerville C, Chapple C C S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6869–6874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer K, Shirley A M, Cusumano J C, Bell-Lelong D A, Chapple C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6619–6623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ralph J, Marita J M, Ralph S A, Hatfield R D, Lu F, Ede R M, Peng J, Quideau S, Helm R F, Grabber J H, et al. In: Progress in Lignocellulosics Characterization. Argyropoulos D S, Rials T, editors. Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry, Atlanta, GA: TAPPI; 1999. pp. 55–108. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert D, Ämmälahti E, Bardet M, Brunow G, Kilpeläinin I, Lundquist K, Neirinck V, Terashima N. In: Lignin and Lignan Biosynthesis. Lewis N G, Sarkanen S, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Chem. Soc.; 1998. pp. 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lüdemann H-D, Nimz H. Makromol Chem. 1974;175:2393–2407. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lüdemann H-D, Nimz H. Makromol Chem. 1974;175:2409–2422. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilpeläinen I, Sipilä J, Brunow G, Lundquist K, Ede R M. J Agric Food Chem. 1994;42:2790–2794. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ede R M, Ralph J. Magn Reson Chem. 1996;34:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ralph J. Magn Reson Chem. 1993;31:357–363. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundquist K, Paterson A, Ramsey L. Acta Chem Scand Ser B. 1983;37:734–736. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ralph J, MacKay J J, Hatfield R D, O’Malley D M, Whetten R W, Sederoff R R. Science. 1997;277:235–239. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ralph J, Hatfield R D, Piquemal J, Yahiaoui N, Pean M, Lapierre C, Boudet A-M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12803–12808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu F, Ralph J. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45:4655–4660. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu F, Ralph J. In: Lignin and Lignan Biosynthesis. Lewis N G, Sarkanen S, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Chem. Soc.; 1998. pp. 294–322. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu F, Ralph J. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45:2590–2592. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ralph J, Hatfield R D, Quideau S, Helm R F, Grabber J H, Jung H-J G. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:9448–9456. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatfield R D, Jung H G, Ralph J, Buxton D R, Weimer P J. J Sci Food Agric. 1994;65:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ralph J. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:341–342. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarkanen K V, Chang H-M, Allan G G. TAPPI. 1967;50:587–590. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musha Y, Goring D A I. Wood Sci Technol. 1975;9:45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casey J M. M.S. thesis. Seattle: University of Washington; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphreys J M, Hemm M R, Chapple C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10045–10050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osakabe K, Tsao C C, Li L, Popko J L, Umezawa T, Carraway D T, Smeltzer R H, Joshi C P, Chiang V L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8955–8960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen F, Yasuda S, Fukushima K. Planta. 1999;207:597–603. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kay L E, Keifer P, Saarinen T. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer A G, Cavanagh J, Wright P E, Rance M. J Magn Reson Ser A. 1991;93:151–170. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willker W, Leibfritz D, Kerssebaum R, Bermel W. Magn Reson Chem. 1992;31:287–292. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karhunen P, Rummakko P, Sipilä J, Brunow G, Kilpeläinen I. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:169–170. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karhunen P, Rummakko P, Sipilä J, Brunow G, Kilpeläinen I. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:4501–4504. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ämmälahti E, Brunow G, Bardet M, Robert D, Kilpeläinin I. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:5113–5117. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarkanen K V, Ludwig C H. Lignins: Occurrence, Formation, Structure, and Reactions. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunow G, Karlsson O, Lundquist K, Sipilä J. Wood Sci Technol. 1993;27:281–286. [Google Scholar]