Abstract

Chromosomal amplifications and deletions are critical components of tumorigenesis and DNA copy-number variations also correlate with changes in mRNA expression levels. Genome-wide microarray comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) has become an important method for detecting and mapping chromosomal changes in tumors. Thus, the ability to detect twofold differences in fluorescent intensity between samples on microarrays depends on the generation of high-quality labeled probes. To enhance array-based CGH analysis, a random prime genomic DNA labeling method optimized for improved sensitivity, signal-to-noise ratios, and reproducibility has been developed. The labeling system comprises formulated random primers, nucleotide mixtures, and notably a high concentration of the double mutant exo-large fragment of DNA polymerase I (exo-Klenow). Microarray analyses indicate that the genomic DNA-labeled templates yield hybridization signals with higher fluorescent intensities and greater signal-to-noise ratios and detect more positive features than the standard random prime and conventional nick translation methods. Also, templates generated by this system have detected twofold differences in gene copy number between male and female genomic DNA and identified amplification and deletions from the BT474 breast cancer cell line in microarray hybridizations. Moreover, alterations in gene copy number were routinely detected with 0.5 μg of genomic DNA starting sample. The method is flexible and performs efficiently with different fluorescently labeled nucleotides. Application of the optimized CGH labeling system may enhance the resolution and sensitivity of array-based CGH analysis in cancer and medical genetic studies.

Keywords: CGH, array-based CGH, chromosome imbalances, DNA labeling system, random prime labeling, genomic DNA labeling, labeling, DNA copy number

Alterations in chromosomes, which lead to deletions and amplifications, are being identified as critical components of tumorigenesis.1,2 Moreover, DNA copy-number variations have also been directly correlated with changes in mRNA levels, indicating that underlying genetic imbalances may significantly impact the development and progression of many tumor-specific expression profiles.1–3 Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) has become a common method of whole genome analysis used to detect and map widespread amplifications and deletions of DNA sequences.4,5 Recent advances of microarray methods including the use of large insert genomic bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) vector clones,6,7 cDNA clones,8–10 and oligonucleotides have circumvented some of the limitations of conventional CGH. These array-based methods allow researchers to perform the high-resolution genome scans in tumor samples with higher throughput. Thus, genome-wide array-based CGH offers the potential for improved resolution and sensitivity and has become an important method in detecting chromosomal imbalances in cancer and medical genetic studies.1–10

The standard array-based CGH utilizes two genomic DNA samples: a test sample, usually from a tumor; and a reference sample, usually normal genomic DNA. The test and reference DNA are differentially labeled with fluorescent nucleotides and simultaneously hybridized to a microarray, where hybridization of repetitive sequences are blocked by the addition of Cot-1 DNA. The relative fluorescent intensities between the two samples represent the ratios of the copy number of sequences in DNA samples and thereby identify amplifications or deletions at specific loci along the genome.2,8

The two primary methods employed to label genomic DNA for CGH analysis are the nick translation4 and the random prime methods.3,8 The nick translation method utilizes a limited DNAse I treatment to nick the doubled-stranded DNA allowing Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (holoenzyme) to use the nicks as a starting point from which one strand of a duplex DNA is degraded by the 5′−3′ exonuclease activity of the holoenzyme and replaced by the resynthesis and incorporation of labeled nucleotides during synthesis of new material. In this method, the nick moves along the site of new synthesis but is not accompanied by DNA amplification. Alternatively, the random prime labeling method utilizes a high concentration of Klenow enzyme whereby genomic DNA is digested with restriction enzymes and hybridized with random primers. The primers are extended by the 5′−3′ polymerase activity of Klenow resulting in a strand displacement activity with the direct incorporation of labeled nucleotides accompanying a DNA amplification of at least fourfold over starting amounts.

In some aspects, array CGH may be more technically challenging than expression profiling. For example, genomic DNA is more complex and often it is required to detect small ratio deviations reflecting a single-copy loss of a tumor suppressor gene from a mixed cell population.1 Thus the ability to detect twofold differences in fluorescent intensity between samples on microarrays depends on high-quality fluorescent-labeled probes to meet the very stringent demands for reliable and sensitive performance. To enhance array-based CGH analysis, a random prime genomic DNA labeling system utilizing the double mutant exo-large fragment of DNA polymerase I (exo-Klenow) was developed and validated for improved sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility. Exo-Klenow is unique in that it lacks both the 5′−3′ endonuclease activity of standard Klenow and the 3′–5′ exonuclease activity of the intact DNA polymerase I, but does exhibit 5′−3′ DNA polymerase activity. In this study, the newly developed Exo-Klenow labeling method (BioPrime CGH, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was validated against other published and available methods for greater signal-to-noise ratios, an increased number of positive features, accuracy in the detection of differential copy number, and other performance parameters in array CGH analysis.

METHODS

Labeling Reactions

The BioPrime Array CGH Genomic Labeling System (Invitrogen) comprises formulated random primers, nucleotide mixtures, and a high concentration of highly concentrated exo-Klenow, which were optimized for use with standard fluorescent-labeled nucleotides. Briefly, the labeling reactions were initiated with 0.5–2.0 μg of human genomic DNA (aneuploid nontrisomic chromosome DNA, Coriell Cell Repositories, Camden NJ, NA01416; BT-747 tumor DNA, ATCC, Manassas, VA) for BAC arrays and typically 4 μg of genomic DNA for cDNA arrays. The genomic DNA was digested (2 h, 37°C) with the common cutting DpnII restriction endonuclease (or by shearing) and phenol/chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, and resuspended in 21 μL of water. Twenty microliters of 2.5X random primer mix was added and the sample heated at 95°C (5 min), cooled on ice, and 5 μL of 10X dCTP or dUTP nucleotide labeling mix was added followed by addition of 3 μL of Cy3- or Cy5-dCTP or dUTP (1 mM stocks, Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). One microliter of concentrated (40 U/μL) exo-Klenow was added and incubated for 2 h at 37°C according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedures (Invitrogen).

The labeled templates were purified by the addition of 45 μL of 10 mN Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, followed by the addition of buffer A (400 μL) and placed in a nucleospin column and microfuged at 11,000 × g for 1 min at room temperature. The flowthrough was discarded and columns were washed with the purification buffer B (600 μL) and microfuged at 11,000 × g for 1 min at room temperature. The flowthrough was discarded and the columns were washed a second time with buffer B (200 μL). The labeled genomic DNA was eluted with 50 μL of water and recovered by microfugation at 11,000 × g for 1 min according to the manufacturer’s procedures (Invitrogen).

The labeling efficiency, as determined by the picomol incorporation and base-to-dye ratio of Cy3-dCTP and Cy5-dCTP in newly synthesized DNA, was quantified by UV spectroscopic scanning at λ = 240–800 nm with the maximum absorbance for Cy3 and Cy5 at λ = 550 and 650 nm, respectively. Standard labeling reactions, starting with 2 μg of genomic DNA, yielded greater than 2.8 μg of DNA ([OD260–OD320] * 50 * 0.05 [elution volume]) and more than 100 pmol of incorporation of both Cy3 ([OD550–OD650] / 0.15 * 50 [elution volume]) and Cy5 ([OD650–OD750] / 0.25 * 50 [elution volume]). Base-to-dye ratios were calculated accordingly (base dye = [OD260 × ɛ dye] / [ODdye × ɛ base]; ɛ dye = Cy3 = 150,000; Cy5 = 250,000 [cm−1M−1]; ɛ base = dsDNA = 6600).

The labeled templates were suitable for hybridizations onto BAC and cDNA microarrays according to the individual hybridization protocols (see Microarray Hybridization below). Most protocols recommend that labeled probes be precipitated with Cot-1 DNA (Invitrogen), yeast tRNA, and poly(dA-dT), or concentrated with microcon-YM30 filters (Millepore, Billerica, MA) before hybridization.3–8 For competitive audits, the Vysis nick translation genomic labeling kit (Downers Grove, IL) as well as the Spectral Genomics Klenow random prime methods (Houston, TX) were tested. The reactions were conducted according to each manufacturer’s recommended procedures.

MICROARRAY HYBRIDIZATIONS

For development and validation of the exo-Klenow system, labeled templates were hybridized to genomic arrays consisting of BAC clone (KTH3–1400, Spectral Genomics). The BAC arrays contained 1400 non-overlapping BAC clones, consisting of large DNA fragments approximately 200 kb in length. Each clone was spotted in duplicate, with a total of 3000 elements on each array. Microarrays containing 12,814 cDNA clones (G4100A, Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) were also evaluated and hybridizations were performed according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedures. Slides were scanned using a 4000B Axon scanner (Union City, CA) at PMT settings of 750–850 and raw hybridization signals were corrected by subtracting local background signals with all clones included in the analysis. Global median signals were obtained for each Cy3 and Cy5 labeling reaction and signal-to-noise ratios were obtained by dividing median signals over the median signals of the background. Gene copy numbers were expressed by the ratio of the Cy3 signals divided by the normalized Cy5 signals at each locus.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To meet the stringent demands for a reliable and sensitive CGH labeling method, key criteria were established which required the new method to (1) generate greater fluorescent picomol incorporation into genomic DNA than comparable nick translation and random primed protocols; (2) yield higher mean fluorescent intensity and signal-to-noise ratios, with detection of a greater number of positive features than comparable methods; and (3) reliably detect twofold differentials in gene copy number following hybridization to microarrays.

Labeling Comparison with Exo-Klenow

Several studies and protocols have demonstrated the effectiveness of random priming by high concentration Klenow for array-based CGH.2,3,5,8 However, preliminary experimentation indicated that extended incubation with Klenow fragment may be slightly less optimal, perhaps due to the 3′–5′ exonuclease activity of the fragment. Thus, to explore ways to improve upon the labeling procedure, a series of experiments were conducted with the standard single mutant Klenow fragment which lacks the 5′−3′ exonuclease activity but still retains 3′–5′ exonuclease activity and the double mutant exo-Klenow fragment which lacks both 3′–5′ and 5′−3′ exonuclease activities.11

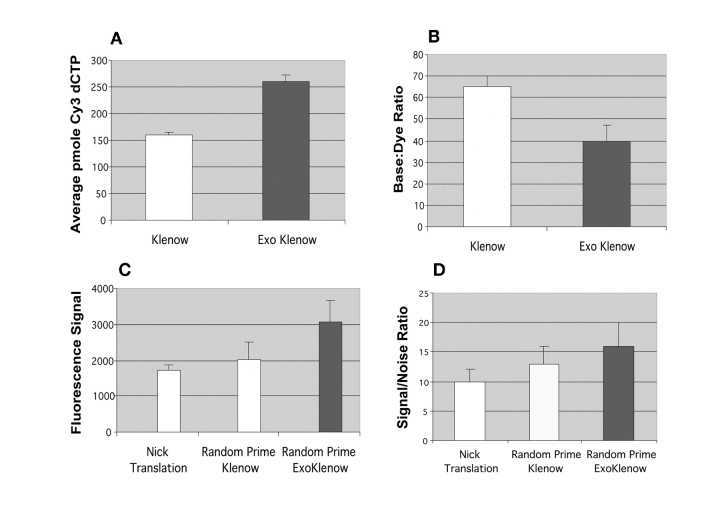

As shown in Figure 1, a comparison between the labeling efficiency of the standard single mutant Klenow and the double mutant exo-Klenow demonstrated that the exo-Klenow generated an increased yield of labeled template, as determined by the total picomol incorporation of Cy3-dCTP into newly synthesized DNA (Fig. 1A). The exo-Klenow-based method also mediated more efficient labeling, as indicated by a lower base-to-dye ratio, than the Klenow-based method (Fig. 1B). Moreover, equivalent levels of incorporation and base-to-dye ratios (~90%) were routinely observed with Cy5-dCTP.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of exo-Klenow, Klenow, and nick translation labeled templates. A: Spectrophotemetric quantifications of dye-dCTP incorporation starting from 100 ng of genomic DNA labeled with 40 units of Klenow or exo-Klenow at 37°C for 4 h (n = 3). B: Calculated Cy3 base-to-dye ratios from Klenow and exo-Klenow labeled templates. C: Normalized median fluorescence signal quantifications from scanned images of 3000-element BAC arrays hybridized to 2 μg of genomic DNA Cy3 labeled with the exo-Klenow, standard Klenow, and nick translation methods (n = 3). D: Cy3-labeled signal-to-noise ratios calculated from the scanned images of BAC arrays hybridized with the exo-Klenow, Klenow, and nick translation labeled templates. Data shown are from a representative experiment replicated a minimum of three independent times.

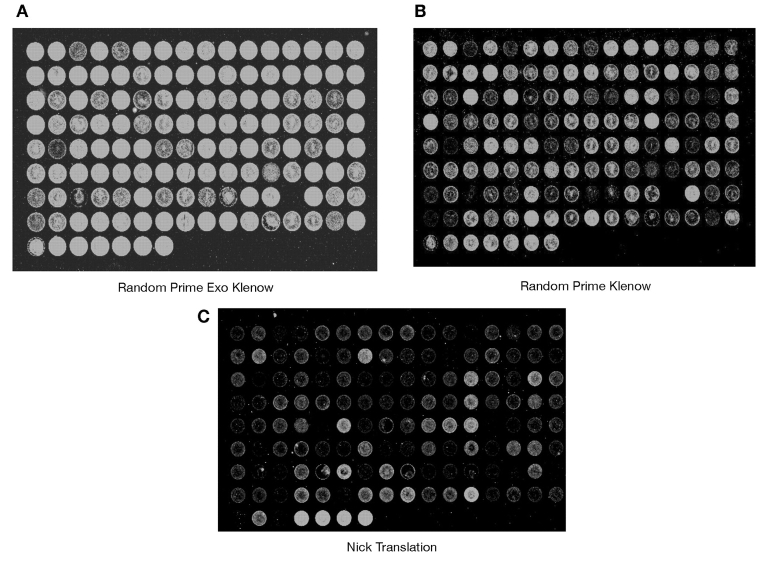

As a comprehensive audit of the experimental exo-Klenow labeling procedure, hybridization experiments with genomic DNAs labeled with conventional nick translation reagents (see Methods), a standard random prime method (see Methods), and the exo-Klenow system (BioPrime CGH, Invitrogen) were assessed on BAC arrays. Of significance, the newly synthesized templates with greater dye incorporation, as determined by spectrophotometric scanning, (Fig. 1A and B) also yielded greater fluorescent signals in microarrays hybridizations. Quantifications of the scanned images demonstrated that DNA templates labeled with the new exo-Klenow formulation yielded higher normalized Cy3 and Cy5 median signals than the standard nick translation and Klenow-based random labeling methods (Fig. 1C), and the exo-Klenow labeled templates yielded greater signal-to-noise ratios than the other two conventional methods (Fig. 1D). Equivalent hybridization signals (~90%) were routinely observed with exo-Klenow labeled Cy3 and Cy5 labeled templates, though raw signal-to-noise ratios from Cy5 labeled templates were proportionately less than Cy3 ratios for all three labeling methods. Moreover, visualization of the scanned images of the comparative hybridizations show the exo-Klenow labeled templates hybridizing with brighter fluorescent intensity (Fig. 2A) than the competing random prime labeled (Fig. 2B) and conventional nick translation labeled templates (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of scanned images from microarray hybridizations with exo-Klenow, Klenow, and nick translation labeled templates. A. Microarray image of exo-Klenow labeled (Cy3) genomic DNA (2 μg) hybridized to a 3000-element BAC array. B. Microarray image generated under standard conditions from random primed Klenow labeled templates hybridized to a 3000-element BAC array. C. Microarray image generated from nick translation labeled genomic DNA (2 μg) hybridized to a BAC array. Data shown are from a representative experiment replicated a minimum of three independent times.

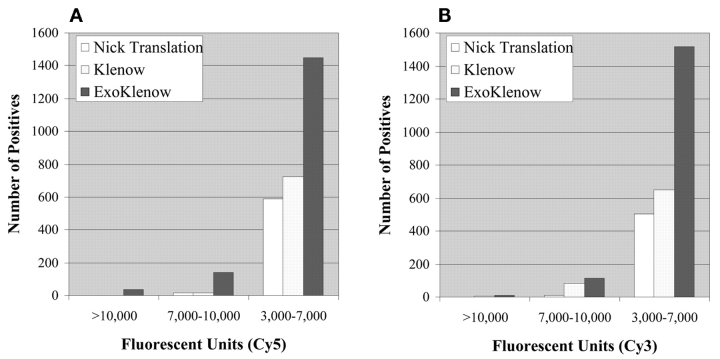

Importantly, determination of the total number of positive features or clones on the BAC arrays with fluorescent signals ranging from 3000 to 10,000 relative mean fluorescent units (MFI) demonstrates that exo-Klenow labeled templates yielded the highest number of positive features in three different intensity categories with both Cy5 (Fig. 3A) and Cy3 (Fig. 3B) templates. Thus the greater dye-nucleotide incorporation efficiency of exo-Klenow based DNA synthesis translates into greater sensitivity and detection of more positive features in microarray CGH analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of the total number of positive signals. A: Total number of positive features (background corrected) above 3000 mean fluorescent units from Cy5-labeled template hybridized to a 5K-feature BAC array. B: Total number of Cy3-labeled positive features (background corrected) from a 5K-feature BAC array. Data shown are from a representative experiment conducted a minimum of three independent times. Median Cy3 and Cy5 background signals were routinely ~100 and ~400 fluorescent units, respectively. All images were scanned at the 700 PMT setting.

Gene Copy Number

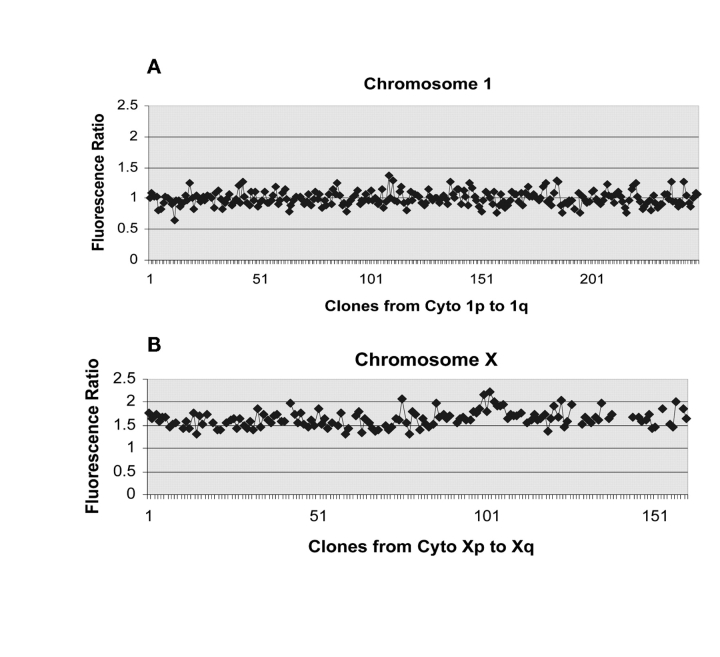

To assess the gene copy number accuracy of the exo-Klenow based labeling method, 500 ng of genomic DNA starting sample was labeled and hybridized to BAC arrays and the ratio of the fluorescent signal between Cy5-labeled female genomic DNA and Cy3-labeled male genomic DNA was determined by examination of the features of the microarrays representing the autosomal chromosome 1 and the sex chromosome X. As shown in Figure 4, the ratio of Cy5/Cy3 templates hybridized to features representing chromosome 1 were close to 1.0 (Fig. 4A), indicating an equal copy number between male and female genomic DNA. Conversely, the female-to-male hybridization ratio to features of chromosome X, as expected, was greater than 1.5 (Fig. 4B). These results clearly demonstrate the delineation between two copies of chromosome X in the female diploid genomic DNA relative to the one copy per genome present in the male DNA. Also, the exo-Klenow labeling system routinely detected twofold differences more closely aligned with the predicted ratios than the corresponding nick translation and Klenow labeled templates in array CGH analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Representation of array-CGH data demonstrating detection of differential gene copy number between 500 ng of male and female genomic DNA. A: Analysis of exo-Klenow Cy5-labeled female genomic DNA and Cy3-labeled male genomic DNA yielded a ratio of 1.0 from chromosome 1 features on a BAC array. B: The average ratio from co-hybridized female/male samples yielded a ratio greater than 1.5 from X chromosome specific features on BAC arrays. The p values for pair-wise student t-tests for differential ratio of the X chromosome are significant (1.6 × 1016). Data shown are from a representative experiment conducted a minimum of three times.

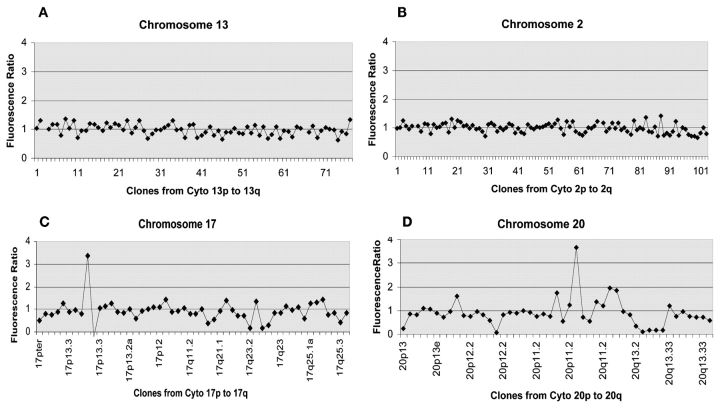

Further validation of the accuracy and sensitivity of the exo-Klenow labeling method was based on the detection of differential copy number from normal female genomic DNA and DNA from the breast cancer cell line BT474,4,8,10 which were labeled and hybridized to BAC arrays. As expected, analysis of labeled templates demonstrated an equivalent gene copy number, with a ratio of 1.0 between normal DNA templates and the BT474 tumor DNA templates hybridized to features representing chromosome 2 and chromosome 13 (Fig. 5A and B). However, examination of regions in the p and q arm of chromosome 17 (Fig. 5C) and chromosome 20 (Fig. 5D) reveal ratios that deviate from 1.0, indicating subregions of chromosomal deletions and amplifications. These observations were consistent with previously reported studies that have identified these subregions of chromosome 20 and 17 to contain amplifications and deletions in the BT474 breast cancer cell line.4,8,10 Furthermore, preliminary examination of exo-Klenow templates labeled with different fluorphores (Alexa, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and hybridizations to microarrays containing 12,814 cDNA clones (Agilent, G4100A) were also evaluated with satisfactory results (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Detection of copy number imbalances between normal and cancer cell line DNA. A: Analysis of the hybridization ratio between exo-Klenow labeled normal female genomic DNA and breast cancer cell line BT474 DNA hybridized to features representing chromosome 2 demonstrating a normal ratio balance of approximately 1.0. B: Ratiometric analysis of features representing chromosome 13 on BAC arrays demonstrating a normal ratio balance of approximately 1.0. C: Note ratiometric determinations of hybridized features representing regions of chromosome 17 which deviate from 1.0, indicating regions with amplifications and deletions, which have been previously noted in independent studies.4–6 D: Ratiometric evaluation from array features representing chromosome 20 show regions of copy number amplification and deletion imbalances, which also have been previously noted in independent studies.4–6 Data shown are from a representative experiment.

CONCLUSIONS

Genome-wide microarray CGH has become an important method in detecting chromosomal imbalances and elucidating the mechanisms of tumorigenesis.1–2 Thus, the ability to detect twofold differences in fluorescent intensity between samples is of critical importance for array CGH analysis and depends on the use of high-quality labeled probes. To enhance array-based CGH analysis, an exo-Klenow based random prime genomic DNA labeling system (BioPrime CGH, Invitrogen) that was optimized for improved sensitivity, signal-to-noise ratios, and reproducibility has been developed. Microarray analyses indicate that the genomic DNA labeling method produces hybridization signals with higher fluorescent intensities and greater signal-to-noise ratios than other published and commercially available methods. The labeled templates generated by the exo-Klenow method have been validated to differentially detect twofold differences in gene copy number between male and female samples, routinely from 0.5 μg of starting genomic DNA sample. The enhanced sensitivity obtained with the exo-Klenow labeling method may also facilitate the use of oligonucleotide arrays for gene copy number analysis.1 The optimized BioPrime CGH labeling system was found to meet the stringent demands for reliable and sensitive detection of twofold differences in copy number, and application of the system should enhance the resolution and sensitivity of array-based CGH analysis in cancer and medical genetic studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. John Carrino and A. J. Bokal for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pollack RP, Vishwanath RI. Characterizing the physical genome. Nat Genet Suppl 2002;32:515–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albertson D, Pinkel D. Genomic microarrays in human genetic disease and cancer. Hum Mol Genet 2003;12 Spec No.2:R145–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollack JR, Sorlie T, Perou C, et al. Microarray analysis reveals a major direct role of DNA copy number alteration in the transcriptional program of human breast tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:12963–12968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinkel D, Segraves R, Sudar D, et al. High-resolution analysis of DNA copy number variation using comparative genomic hybridization to microarrays. Nat Genet 1998;20:207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snijders AM, Nowak N, Segraves R, et al. Assembly of microarrays for genome-wide measurement of DNA copy number. Nat Genet 2001;29:263–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodgson G, et al. Genome scanning with array CGH delineates regional alterations in mouse islet carcinomas. Nat Genet 2001;29:459–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai W, et al. Genome-wide detection of chromosomal imbalances in tumors using BAC microarrays. Nat Biotechnol 2002;20:393–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollack JR, Perou T, Alizadeh AA, et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy-number changes using cDNA microarrays. Nat Genet 1999;23:41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beheshti B, et al. Chromosomal localization of DNA amplifications in neuroblastoma tumors using cDNA microarray comparative genomic hybridization. Neoplasia 2003;5:53–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lage JM, Leamon JH, Pejovic T, et al. Whole genome analysis of genetic alterations in small DNA samples using hyperbranched strand displacement amplification array-CGH. Genome Res 2003;13:294–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derbyshire V, et al. Genetic and crystallographic studies of the 3′–5′-exonucleolytic segment of DNA polymerase I. Science 1988;240:199–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]