Abstract

Neutrophils undergo rapid constitutive apoptosis that is delayed by a range of pathogen and host derived inflammatory mediators. We have investigated the ability of the nucleotide ATP, to which neutrophils are exposed both in the circulation and at sites of inflammation, to modulate the lifespan of human neutrophils. We found physiologically relevant concentrations of ATP cause a concentration-dependent delay of neutrophil apoptosis (assessed by morphology, Annexin V/To-Pro3 staining and mitochondrial membrane permeabilisation). We found even brief exposure to ATP (10 mins) was sufficient to cause a long-lasting delay of apoptosis and showed the effects were not mediated by ATP breakdown to adenosine. The P2 receptor mediating the anti-apoptotic actions of ATP was identified using a combination of more selective ATP analogues, receptor expression studies and study of downstream signalling pathways. Neutrophils were shown to express the P2Y11 receptor and inhibition of P2Y11 signalling using the antagonist NF157 abrogated the ATP-mediated delay of neutrophil apoptosis, as did inhibition of type-I cAMP-dependent protein kinases activated downstream of P2Y11, without effects upon constitutive apoptosis. Specific targeting of P2Y11 could retain key immune functions of neutrophils but reduce the injurious effects of increased neutrophil longevity during inflammation.

Keywords: Neutrophil, Apoptosis, ATP

Introduction

Apoptosis (programmed cell death) of neutrophils is an important control point in the physiological resolution of innate immune responses. In this context, neutrophil apoptosis must be delayed until essential host functions such as pathogen clearance are completed but then proceed promptly to abrogate inflammation and avoid tissue damage (1). Neutrophils are typically short-lived cells that can engage a constitutive programme of apoptosis (2), leading to down-regulation of neutrophil pro-inflammatory functions and clearance by phagocytes (2, 3). There is abundant evidence the balance between neutrophil survival and death by apoptosis is exquisitely regulated by a range of extracellular factors, including host-derived cytokines and pathogen-derived molecules to which neutrophils are exposed in the circulation and in tissues (4, 5). The potential for extracellular nucleotides, particularly adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), to modulate neutrophil survival has not been investigated.

Neutrophils are exposed to ATP in a variety of in vivo situations and its role as a signalling molecule in pathophysiological situations is increasingly recognised (6). ATP is released into the circulation following activation of platelets and endothelial cells (7, 8), for example in acute coronary syndromes (7), potentially exposing circulating neutrophils to high local concentrations. Within 3 minutes following vessel wall injury, ATP concentrations of 20μM can be detected (9) and 1 × 107 platelets can release > 55μM ATP (8). ATP is also released from dying cells (10), notably in chronic inflammatory conditions such as cystic fibrosis (11, 12). The effects of ATP are mediated via P2 receptors (13), which are further divided into P2X and P2Y subfamilies (14). Both are widely expressed in tissues and implicated in diverse cellular functions. ATP has been shown to modulate neutrophil pro-inflammatory functions, including chemotaxis (15), NADPH oxidase-dependent superoxide anion generation (16), and secretion of granule contents (17, 18).

We hypothesised that extracellular ATP may be a critical regulator of neutrophil apoptosis. We found that even short exposures to ATP delay neutrophil apoptosis, an effect that is independent of increases in [Ca2+]i but dependent upon type-I cAMP-dependent protein kinases. Studies of receptor expression and use of P2 subtype inhibitors and agonists identified P2Y11 as the purinergic receptor mediating the anti-apoptotic effect. These studies identify a novel potential therapeutic target for the amelioration of neutrophilic inflammation in a wide range of inflammatory diseases.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK) unless otherwise stated. The phospholipase C inhibitor U73122 and its inactive analogue U73343, Rp-8-Br-cAMPS and pluronic acid were purchased from Calbiochem (Beeston, UK). Fluo-4 AM was obtained from Molecular Probes (Oregon, USA). The P2Y11 and P2X7 (APR-008) receptor antibodies for western blotting were from Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel). The P2X7 antibody for flow cytometry was a kind gift from GlaxoSmithKline (19) and the IgG2b isotype control was from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK). The P2Y11 antagonist NF157 was synthesised as previously described (20).

Neutrophil isolation and culture

Human neutrophils were isolated by dextran sedimentation and plasma-Percoll gradient centrifugation from whole blood of normal volunteers (21) with written informed consent and the approval of the South Sheffield Research Ethics Committee. Purity (>94%) was assessed by counting >300 cells on duplicate cytospins, with contaminating cells being mostly eosinophils. In some experiments neutrophils were further purified by negative magnetic selection, increasing neutrophil purity to >99.9% by removal of the low level of contaminating cells, especially PBMCs, that can affect the responses of neutrophils (22). These neutrophils are referred to in text as highly-purified neutrophils. Neutrophils were suspended at 2.5 × 106/ml in RPMI with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% FCS (all Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and cultured in 96 well Falcon “Flexiwell” plates (Becton Dickinson). Freshly isolated neutrophils were designated as time 0.

ATP and ATP analogues were added at time 0 and incubated for 5 hours unless otherwise stated. Neutrophils treated with Rp-8-Br-cAMPS or NF157 were pre-incubated for 30 mins before addition of ATP or ATP analogues.

Assessment of Cell Viability and Apoptosis

Nuclear morphology was assessed on Giemsa-stained cytospins, with blinded observers counting >300 cells per slide on duplicate cytospins. Hemocytometer counts were performed at all time points, both to assess cell retrieval and for trypan blue exclusion. No significant differences in cell retrieval were noted with different treatments and necrosis was <2% throughout. In some experiments, neutrophils were washed in PBS and stained with PE-labelled Annexin V (BD Biosciences) and To-Pro®-3 iodide (Molecular Probes) to identify apoptotic (Annexin V+) and necrotic (To-Pro3+) cells (23). Controls included EDTA treatment (to determine Annexin V-population), freeze-thawed, necrotic cells (To-Pro3+ cells) and constitutively aged neutrophils (Annexin V+), to set appropriate gating. To detect loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), neutrophils were incubated with 10μM JC-1 (Molecular Probes) at 37°C and loss of ΔΨm was assayed by gain in FL-1 fluorescence (24). Samples were analysed by FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), with 10,000 events recorded and analysed by CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Measurement of Neutrophil [Ca2+]i

Ca2+ transients were measured in populations of human neutrophils loaded with the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 AM using the magnetically stirred Cairn Integra fluorimeter (Cairn Research, Kent, UK) and a previously described method (25). Briefly, neutrophils were incubated with 2μM Fluo-4 AM and 0.1% pluronic acid for 30 min at 37°C in buffer containing 136mM NaCl, 1.8mM KCl, 1.2mM KH2PO4, 1.2mM MgSO4, 5mM NaHCO3, 1.2mM CaCl2, 5.5mM glucose, 20mM HEPES and 5mM EGTA. Cells were washed once in the same buffer with or without EGTA, and then 5×106 cells/ml were placed in a 1ml cuvette for calcium measurements using the Cairn Integra fluorimeter (Cairn Research, Kent, UK). Cumulative agonist concentration-response curves were obtained and results normalised to maximum fluorescence induced by digitonin (2mM) applied at the end of the experiment. Digitonin-induced fluorescence varied by <10% in a single set of experiments (six cuvettes/experiment, data not shown). Curves shown are representative of the whole cell population.

Analysis of mRNA Expression

Total RNA was extracted from highly-pure populations of neutrophils using TRI-reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To obtain cDNA, 1μg of total RNA was primed with oligo-dT primers and reverse transcribed with AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Southampton, UK). Primers for human P2X receptors were designed based on published sequence data. The primers used (forward, reverse) were as follows: P2X1: TTTCATCGTGACCCCGAAGCAG, TCAAAGCGAATCCCAAACACC; P2X2: ACCTGCCCCGAGAGCATAAG, AATGACCCCGATGACACCACCC; P2X3: CACCTCGGTCTTTGTCATCATCAC, TGTTGAACTTGCCAGCATTCC; P2X4: ACAGCAACGGAGTCTCAACAGG, CCTTCCCAAACACAATGATGTCG; P2X5: TCCTGGCGTACCTGGTCGTATGG, CAGTCGCTGTCCTTGGAGCACG; P2X6: GGTGACCAACTTCCTTGTGACG, CCCAGTGAACTCTGATGCCTACAG; P2X7: TGCGATGGACTTCACAGATTTG, TGCCCTTCACTCTTCGGAAAC. PCR settings were 94°C for 1 minute, 55°C for 2 minutes, followed by extension at 72°C for 3 minutes. Each PCR reaction was performed with 35 cycles and the PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Western Blotting

Highly-pure populations of neutrophils were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed with 2x SDS lysis buffer (100mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 100mM dithiothreitol, 20% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 0.2% bromophenol blue, made up in water) containing EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, at 90°C for 10 minutes. The protein was subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE then electrophoretically transferred from the gel onto a 0.45μM polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) microporous membrane (Biorad, Hercules, CA). The membrane was probed with a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the human P2Y11 or P2X7 receptor, with or without the control peptide antigen (at 1μg peptide per 1μg antibody), overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (DAKO, Denmark), and visualised using the ECL system (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) followed by autoradiography.

Flow Cytometry for P2X7 expression

Highly-purified neutrophils, HEK-293 cells (negative control) and HEK-293 cells transfected with human P2X7 (positive control) (26), were used to detect the presence of P2X7. Extracellular expression was detected using fixed cells and total P2X7, both extracellular and intracellular, using cells that were fixed then permeabilised. Fixation and permeabilisation buffers were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Cells were then incubated with the P2X7 receptor antibody (1.25μg/μl) or control IgG2b antibody (1.5ng/ml) for 30 minutes, followed by an anti-mouse IgG FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (10μl/100μl) (Sigma). Analysis of P2X7 receptor expression was by flow cytometry, using a dual-laser FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences), with appropriate single-stained samples for setting of compensation. We confirmed we were able to detect increased expression of CD11b, a protein present intracellularly, following permeabilisation (data not shown).

Measurement of Neutrophil [cAMP]i

Neutrophils have low concentrations of cAMP and so were cultured at 3 × 106/ml, as previously described (27), and pre-incubated with 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) (1mM) for 20 minutes to inhibit breakdown of cAMP, prior to stimulation with ATP, ATP-γ-S or BzATP (all at 100 μM) for 8 minutes. Cells were lysed with 0.1M HCl then spun at 850g for 10 minutes. Supernatants were acetylated to detect intracellular cAMP, using a direct immunoassay kit (Sigma, measuring sensitivity 0.039 pmol/ml) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data are expressed as fold increase in intracellular cAMP compared with unstimulated cells.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean±SEM. Data were analysed as appropriate by students t-test or ANOVA with either Dunnett’s or Bonferroni’s (selected pairs) post-test using the Prism 4.0 program (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Results were considered to be statistically significant where p < 0.05. Statistically significant differences from controls are indicated by *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001. Differences between treated populations are indicated by #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 and ###p<0.001.

Results

ATP delays neutrophil apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner

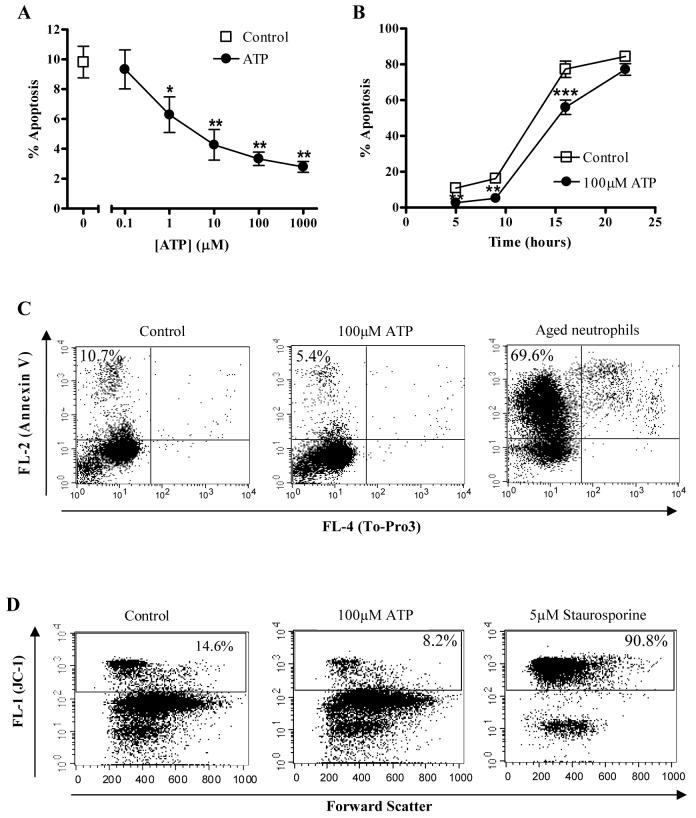

Incubation of neutrophils with ATP resulted in concentration-dependent reductions in neutrophil apoptosis at 5 hours that were significant at ATP concentrations of 1μM and above (Fig. 1A). Such concentrations are physiological and readily achieved in vivo (8, 9). This delay of apoptosis was maintained over a prolonged time course (Fig. 1B). Inhibition of apoptosis was assessed by light microscopy using morphological features (2) and, in further experiments, these changes were correlated with evidence that ATP also delayed cell membrane changes of apoptosis (Annexin V binding, Fig. 1C) and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1 staining, Fig. 1D). There was no evidence of necrotic cell death on trypan blue exclusion or To-Pro3 staining (data not shown), nor of differences in cell retrieval on hemocytometer counts with ATP treatment compared with controls. We have previously shown that the anti-apoptotic effects of a prototypic proinflammatory mediator, LPS, are principally dependent upon the small numbers of mononuclear cells present in neutrophil populations prepared by gradient centrifugation (22). We therefore compared the anti-apoptotic effects of ATP upon neutrophils prepared by the standard method or with an additional purification step based on immunomagnetic bead purification to achieve >98% purity (22). There were no differences in the anti-apoptotic effects of ATP over a range of concentrations (Table 1).

Figure 1. ATP inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis is concentration and time-dependent.

Neutrophils were cultured for varying periods of time in the presence or absence of various concentrations of ATP. Apoptosis was assessed by morphologic criteria and data are expressed as mean±SEM % apoptosis from at least 3 independent experiments, each from a separate donor. (A) Neutrophils were cultured either alone (squares) or with various concentrations of ATP [0.1-1000μM] for 5 hours. (B) Neutrophils were incubated in the presence (circles) or absence (squares) of ATP (100μM) for 5, 9, 16, and 22 hours prior to assessment of apoptosis. (C) Neutrophils were cultured in the presence or absence of ATP (100μM) for 5 hours and apoptosis and necrosis were assessed by staining with Annexin V/To-Pro3 and flow cytometry. Representative dot plots show Annexin V and To-Pro3 staining in untreated cells (negative control), following ATP treatment or constitutively aged, 24 hour neutrophils (positive control). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments in which ATP delayed the onset of apoptosis compared to untreated cells (mean±SEM 5.2±0.8% compared with 9.1±0.8% in control cells, p < 0.05). (D) Neutrophils were cultured for 4 hours with ATP (100μM) or staurosporine (5μM) then stained with the mitochondrial dye, JC-1 and assessed by flow cytometry. Representative dot plots show JC-1 fluorescence in untreated cells (negative control) and following ATP or staurosporine (positive control) treatment. An increase in FL-1 (green) fluorescence indicates loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in neutrophils. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments in which ATP significantly maintained membrane potential compared to untreated cells (10.0±1.1% apoptosis in ATP-treated cells compared with 21.4±2.5% in control cells, p < 0.05).

Table I. Presence of Contaminating Cells Does Not Influence Inhibition of Neutrophil Apoptosis by ATP.

Neutrophils were isolated by plasma/Percoll gradients and further purified by immunomagnetic selection to remove contaminating eosinophils and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Mean±SEM neutrophil purity from each isolation method is given in brackets *. Neutrophils were treated with ATP [0.1-1000μM] for 5 hours. Apoptosis was assessed by morphologic criteria and data is expressed as mean±SEM % apoptosis from 3 independent experiments, each from a separate donor. For both isolation methods ATP significantly inhibited apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner († p = < 0.01, # p = < 0.001) and there was no significant difference between the two isolation methods (p = 0.6614)

| [ATP] (μM) | % Apoptosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Percoll Purified (94.2±1.6%)* | Highly Purified (98.8±0.8%)* | |

| 0 | 12.9 ( ± 0.8) | 15.2 ( ± 1.6) |

| 0.1 | 11.1 ( ± 0.4) | 10.7 ( ± 1.3) † |

| 1 | 7.8 ( ± 0.7) # | 5.8 ( ± 1.1) # |

| 10 | 4.6 ( ± 0.4) # | 5.1 ( ± 0.7) # |

| 100 | 4.7 ( ± 1.0) # | 4.1 ( ± 0.6) # |

| 1000 | 4.3 ( ± 0.5) # | 3.7 ( ± 0.6) # |

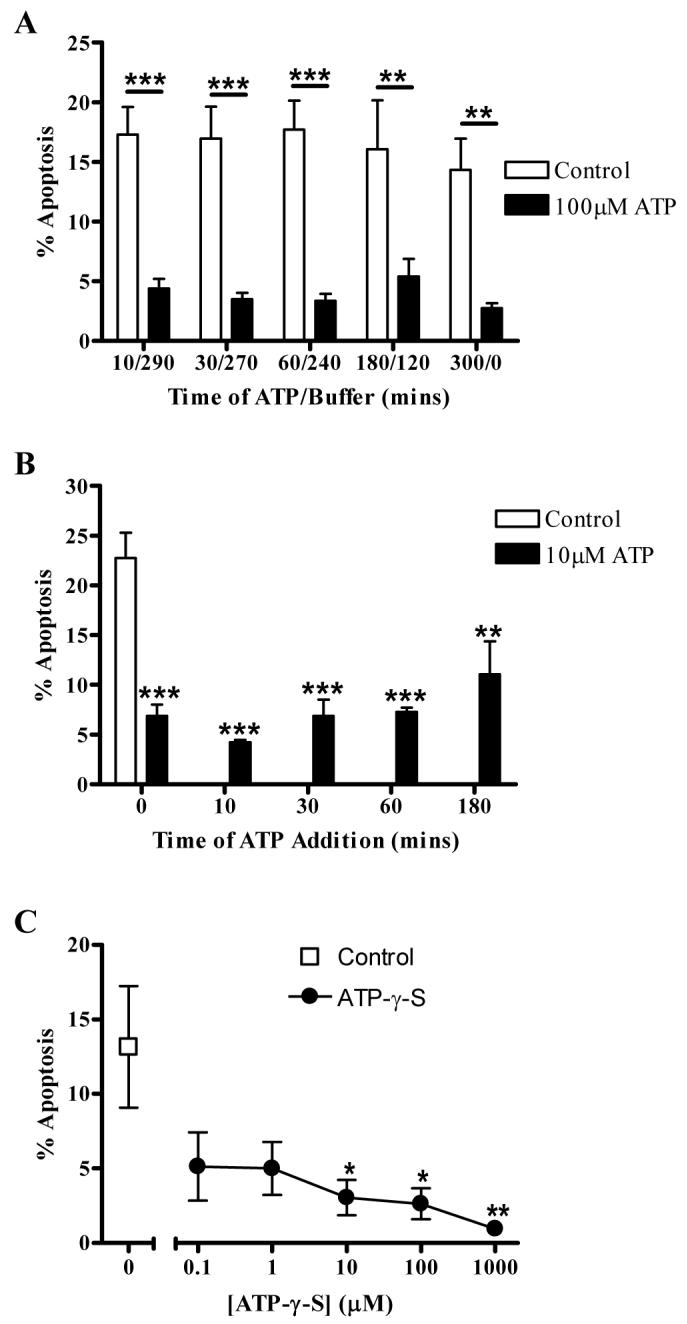

The exposure of neutrophils to significant concentrations of ATP may be of relatively short duration in vivo, since ATP is readily broken down (28), yet the survival effect of ATP treatment of neutrophils was long-lasting. We therefore determined whether prolonged neutrophil survival could be initiated by short exposures to ATP. In Figure 2A, neutrophils were cultured for 5 hours and apoptosis measured. For the first 10, 30, 60 or 180 minutes of this period neutrophils were treated with ATP (or media only as a control), after which time they were washed and returned to fresh media. Other neutrophils were cultured with media alone or ATP throughout the time course, without additional washing. These data show that a 10 minute exposure to ATP (100 μM) at the beginning of the experiment induced similar levels of neutrophil survival as when cells were exposed to ATP throughout the time course, demonstrating rapid engagement of an extremely effective survival mechanism. We also determined whether neutrophils exposed to ATP after they had “aged” in culture could still have a measurable increase in survival following ATP exposure. We found that ATP had a significant survival effect upon neutrophils when added up to 180 minutes after culture (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Delay of neutrophil apoptosis is mediated by short exposures to ATP.

Neutrophils were cultured in the presence (filled bars) or absence (open bars) of ATP. Data are expressed as mean±SEM % apoptosis, assessed by morphologic criteria, from at least 3 independent experiments, each from a separate donor. (A) Neutrophils were cultured with or without ATP (100μM) for varying lengths of time as indicated, after which cells were washed and resuspended in fresh media to remove any remaining extracellular ATP. Cells were cultured for a total of 5 hours prior to assessment of apoptosis. (B) Neutrophils were cultured with or without ATP (10μM) for 5 hours, with ATP added at the time points indicated. Apoptosis was then assessed at 5 hours. ATP significantly delayed apoptosis to similar levels at each time point. (C) Neutrophils were incubated in the presence (circles) or absence (square) of varying concentrations of the stable ATP analogue, ATP-γ-S, for 5 hours and apoptosis assessed.

The “lifespan” of ATP in the tissues and circulation is tightly regulated by the actions of ecto-nucleotidases that hydrolyse ATP to adenosine, which can itself delay neutrophil apoptosis (29). To confirm the effects of ATP on neutrophil apoptosis were not due to breakdown to adenosine, we employed a stable ATP analogue, ATP-γ-S, that is resistant to hydrolysis by ecto-ATPases or phosphatases (30). ATP-γ-S also effectively inhibited neutrophil apoptosis as shown in Figure 2C.

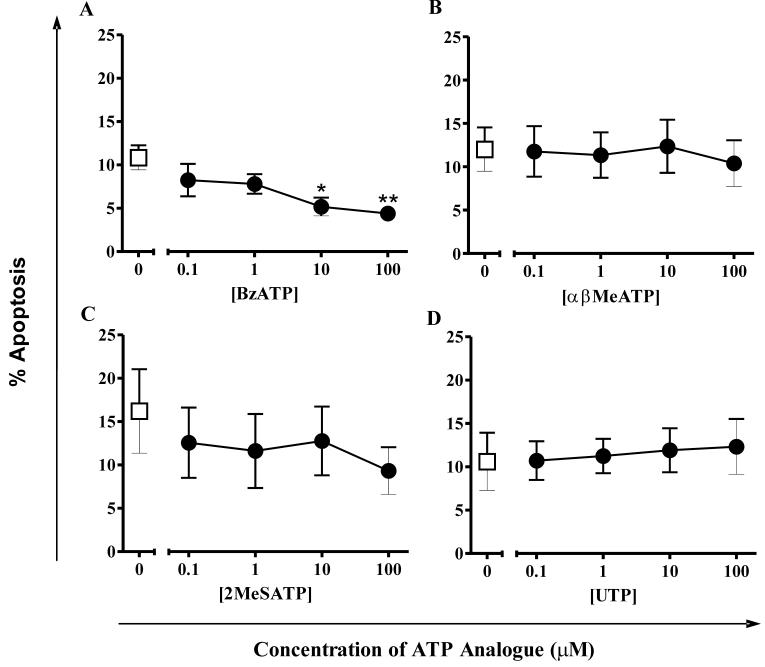

Effect of different ATP analogues upon neutrophil apoptosis

To determine the P2 receptor subtypes responsible for ATP-mediated delay of apoptosis, a variety of approaches were needed because of the lack of a comprehensive battery of specific agonists and antagonists. Initially, ATP analogues with differing preferences for P2 receptor subtypes were studied for their effect upon neutrophil apoptosis (Fig. 3). BzATP, a typical P2X7 agonist, delayed neutrophil apoptosis at concentrations of 1μM and above. In contrast, αβMeATP (which preferentially activates P2X1 and P2X3 receptors), 2MeSATP (a P2Y1, P2X1 and P2X5 agonist) and UTP (a P2Y2 and P2Y4 agonist) did not alter the rate of neutrophil apoptosis at any tested concentration.

Figure 3. Effects of ATP analogues on neutrophil apoptosis.

Neutrophils were cultured in the presence (circles) or absence (squares) of varying concentrations of ATP analogues for 5 hours and apoptosis assessed by morphologic criteria. Data are expressed as mean±SEM % apoptosis from at least 3 independent experiments, each from a separate donor. (A) BzATP, (B) αβMeATP, (C) 2MeSATP and (D) UTP.

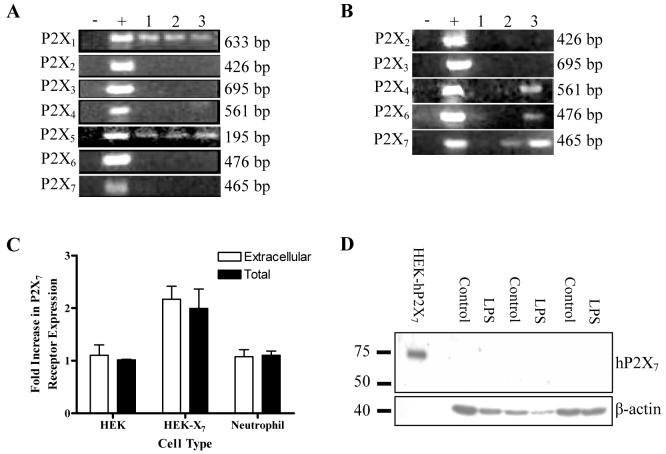

P2X7 receptor subtype is not expressed by human neutrophils

ATP-γ-S and BzATP are the only agonists, other than ATP, which are known to activate P2X7, the purine receptor most often associated with apoptosis in immune cells (31, 32). Therefore we initially examined the possibility that P2X7 receptors may mediate the anti-apoptotic effects of ATP on neutrophils. However, it is unclear whether human neutrophils do (16) or do not (33) express P2X7 receptors, We therefore sought evidence of mRNA expression in highly-purified neutrophil populations. As shown in Figure 4A, only mRNAs for P2X1 and P2X5 were detected in these highly pure populations. If the samples were “spiked” with 5% PBMCs, however, transcripts for P2X4, P2X6 and P2X7 were also intermittently detected (Fig. 4B). Since P2X4 and P2X7 are known to be highly expressed in monocytes (34), it is possible that their detection in previous studies was due to the presence of contaminating cells. There are, however, clear precedents for human neutrophils to express proteins but for the corresponding mRNA to be undetectable. Examples include lactoferrin and myeloperoxidase, major constituents of neutrophil granules (35). Since P2X7 has been thought to mediate functional effects in neutrophils in a number of recent studies, we wanted to exclude its possible expression as rigorously as possible. We found that P2X7 protein could not be detected by flow cytometry either intra or extracellularly in neutrophils, although the protein was readily detected in HEK-293 cells transfected with hP2X7 (Fig. 4C). P2X7 was also not detected by western blotting, and LPS treatment, which up-regulates P2X7 expression in other cell types (36), did not induce its expression in neutrophils (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Expression of P2 receptors by human neutrophils.

(A) PCRs were performed for each of the P2X receptors according to the protocols described in Methods and bands of the appropriate sizes identified as indicated. Three samples of cDNA from highly-purified human neutrophils, each from a different donor (Lanes 3 - 5), were tested for the presence of each P2X receptor mRNA. Lanes 1 and 2 represent negative and positive controls, respectively. Positive controls are vectors containing the receptor subtype cDNA. (B) The studies were repeated using samples of cDNA from highly-purified human neutrophils “spiked” with 5% PBMCs, each from a different donor (Lanes 3-5). Lanes 1 and 2 represent negative and positive controls respectively. P2X4, P2X6 and P2X7 mRNAs were detected in these populations but not in the samples from highly-purified neutrophils. (C) Cells were fixed and/or permeabilised and P2X7 receptor expression was detected by flow cytometry. Fold-increase in P2X7 receptor expression (mean±SEM of 3 independent experiments) is plotted against cell type. HEK-X7 cells showed significant expression of P2X7 both extracellularly and intracellularly (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 respectively) compared with both untransfected HEK cells and neutrophils. Neutrophils do not express P2X7 receptors either intra-(black bars) or extra-cellularly (open bars). (D) Highly-purified neutrophils were cultured with or without 10ng/ml LPS for 16 hours, then western blotted to detect P2X7 receptor protein. Neither untreated nor LPS-stimulated neutrophils expressed detectable P2X7 receptor protein (n = 3). In parallel samples, LPS inhibited apoptosis of neutrophils isolated from each donor population used for western blotting (mean apoptosis in control cells was 74.4±5.7% and in LPS-treated cells was 35.9±4.0%, p < 0.01).

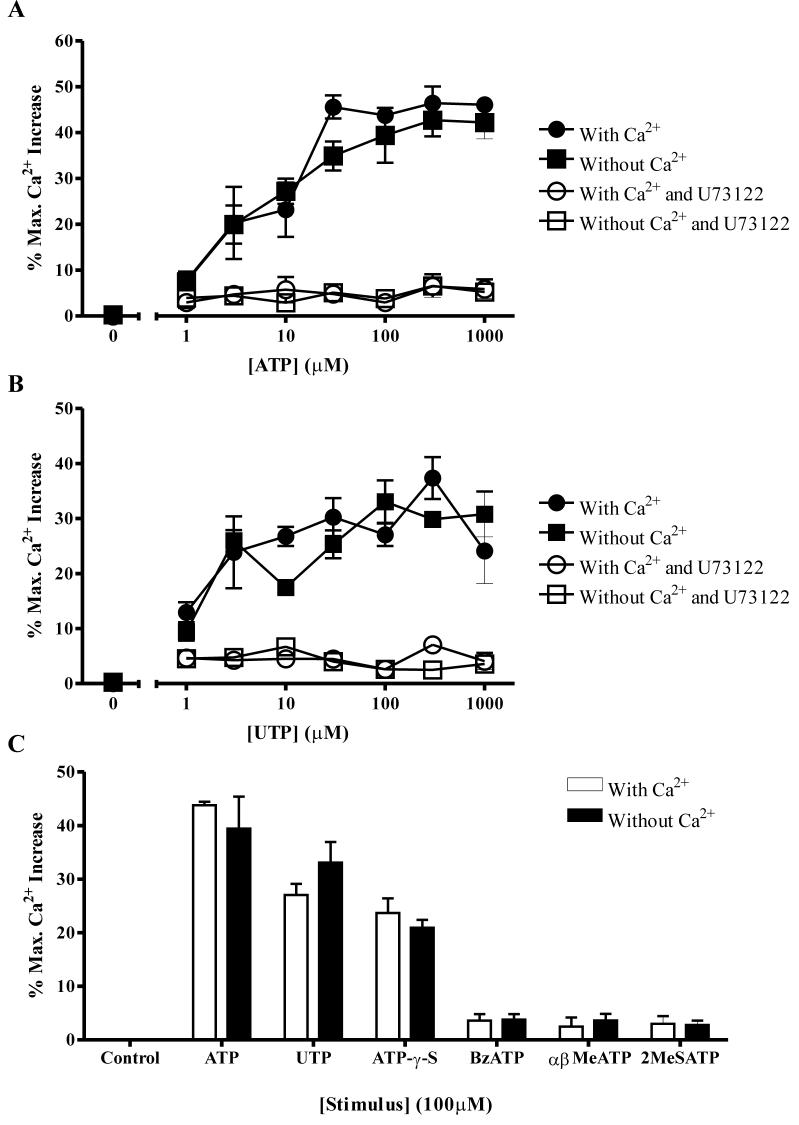

ATP causes elevations of intracellular calcium levels ([Ca2+]i) in neutrophils independently of the delay of apoptosis

To explore further the possibility that the effects of ATP were mediated via a P2Y receptor we measured intracellular calcium levels, since the G protein-coupled seven transmembrane P2Y receptors are known to cause elevations of cytosolic calcium levels via phospholipase C activation and inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate-(IP3-) mediated release of calcium from intracellular stores. Moreover, we have previously shown elevations of [Ca2+]i delay neutrophil apoptosis (37) and thus speculated this might be the mechanism of ATP-mediated delay of apoptosis. We found ATP increased neutrophil [Ca2+]i in a concentration-dependent manner, in the presence or absence of extracellular calcium, implying the increase in [Ca2+]i is mediated from intracellular stores. Addition of a PLC inhibitor, U73122, completely abolished the ATP-mediated [Ca2+]i effect (Fig. 5A). The P2Y agonist UTP increased [Ca2+]i to similar levels to ATP, again a PLC dependent effect (Fig. 5B). Use of the different structural analogues of ATP showed that only the stable analogue, ATP-γ-S, also mediated a calcium response (Fig. 5C). These data suggest the ATP-mediated inhibition of apoptosis and elevation of [Ca2+]i are separate events. UTP increases [Ca2+]i but has no effect upon apoptosis, whereas ATP analogues that increase neutrophil survival, such as BzATP, do not increase [Ca2+]i. This data contrasts with our previous studies linking increases in [Ca2+]i with delay of neutrophil apoptosis (37), but in those studies delay of apoptosis was mediated by influx of extracellular calcium rather than release of calcium from intracellular stores mediated by ATP.

Figure 5. ATP and some analogues increase intracellular Ca2+ via activation of phospholipase C.

Neutrophils were incubated with Fluo-4 AM for 30 mins, then washed and resuspended in buffer in the presence (circles) or absence (squares) of calcium. Cells were then treated with ATP or an ATP analogue as indicated, in the absence (filled symbols) or presence (open symbols) of a PLC inhibitor U73122 (10μM). Increases in intracellular [Ca2+] were measured as a percentage of the maximum Ca2+ released by addition of 2mM digitonin. All data shown are mean±SEM % maximum Ca2+ increase from at least 3 independent experiments, each from a separate donor. Neutrophils were treated with increasing concentrations of (A) ATP (1-1000μM) and (B) UTP (1-1000μM). Both ATP and UTP increase intracellular [Ca2+] from intracellular stores via a PLC dependent mechanism. (C) 100μM concentrations of ATP, UTP, ATP-γ-S, BzATP, αβMeATP and 2MeSATP were added to neutrophils in Ca2+ containing (open bars) or EGTA containing buffer (filled bars). Of these analogues, only ATP-γ-S caused an increase in intracellular [Ca2+] similar to the changes observed with ATP and UTP.

Combining the data from the effects of ATP analogues, expression data and calcium studies allowed us to narrow the range of possible receptors mediating the delay of neutrophil apoptosis by ATP. Since two P2Y agonists (2MeSATP and UTP) did not delay neutrophil apoptosis and the delay of apoptosis was independent of [Ca2+]i, the anti-apoptotic effect of ATP was not typical for a P2Y receptor-mediated effect. Of the P2X receptors identified in neutrophils, P2X1 was an unlikely candidate, since two recognised P2X1 agonists, αβMeATP and 2MeSATP (38), did not inhibit neutrophil apoptosis. There is evidence human P2X5 may not be a functional receptor (38) and 2MeSATP, which is also an agonist at this receptor, was without effect on neutrophil apoptosis. Involvement of P2X7 was effectively excluded by its lack of expression in neutrophils. We also found that a P2X7 antagonist, 1-[N,O-bis(5-isoquinolinesulfonyl)-N-methyl-L-yrosyl]-4-phenylpiperazine (KN62), did not inhibit BzATP-mediated delay of apoptosis, further evidence this effect was independent of P2X7 (data not shown). BzATP is, however, also a potent agonist of the P2Y11 receptor, which is coupled to both phosphoinositide and cyclic AMP signalling pathways (39). BzATP exerts effects upon both phosphoinositide and cAMP signalling pathways with EC50’s in the low micromolar range (39, 40). This is in keeping with a significant effect of BzATP on neutrophil apoptosis at a concentration of 10μM, and contrasts with an EC50 of >50μM for BzATP at the P2X7 receptor (41). Moreover, the rank order of agonist potency at the P2Y11 receptor reveals that ATP-γ-S is at least equivalently potent to BzATP (40), again in keeping with our data and suggesting P2Y11 as the receptor mediating anti-apoptotic signalling.

ATP mediated delay of neutrophil apoptosis is P2Y11 dependent

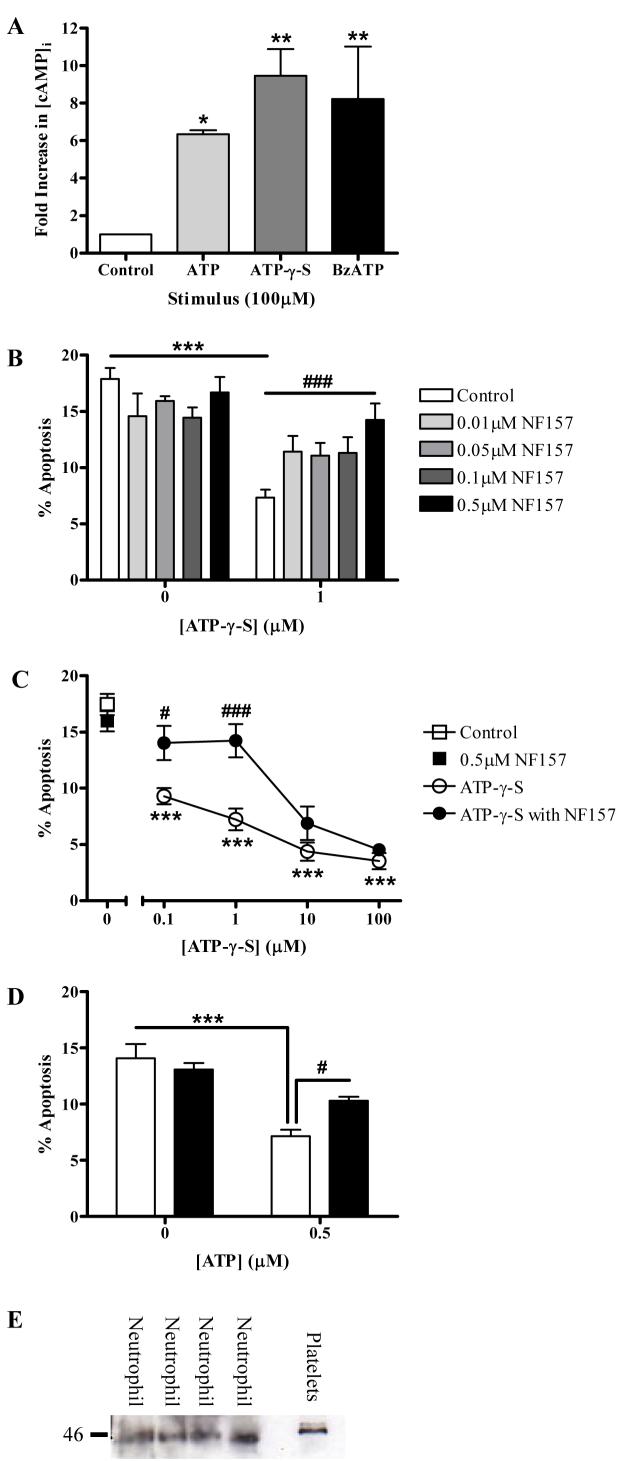

If ATP and its analogues were exerting their anti-apoptotic effects via the P2Y11 receptor, they would be predicted to cause increases in intracellular cAMP. We showed ATP, ATP-γ-S and BzATP all increased [cAMP]i compared with untreated control cells (Fig. 6A). A recent study showed NAD+ exerted its pro-inflammatory effects upon human neutrophils via the P2Y11 receptor (42) and we found NAD+ also caused a concentration-dependent delay of apoptosis that was significant at concentrations of 1μM and above (e.g. mean±SEM apoptosis 4.2±0.5% following 1μM NAD+ compared with 7.9±0.5% in control cells, n = 3, p < 0.01 at 5 hours). During these studies, a potent antagonist at the P2Y11 receptor, NF157, became available, which is derived from suramin, a compound with antagonist activity at most P2 receptors. NF157 was shown to have an IC50 of approximately 0.5μM at the P2Y11 receptor and high selectivity for P2Y11 over all P2X and P2Y receptors tested other than P2X1 (20). We found NF157 blocked ATP-γ-S – mediated delay of neutrophil apoptosis (Fig. 6B) but was without effect upon constitutive neutrophil apoptosis. The inhibitory effect of NF157 was overcome at higher concentrations of ATP-γ-S, confirming the competitive nature of its P2Y11 antagonism (Fig. 6C). The anti-apoptotic effect of ATP was also abrogated by NF157 (Fig. 6D). Moreover, we were able to detect P2Y11 protein in highly-purified neutrophils (Fig. 6E), with a band detected at 45kDa, slightly smaller than the band detected in platelets but within the expected size range for P2Y11 (43).

Figure 6. P2Y11 receptors mediate ATP-induced delay of neutrophil apoptosis.

(A) Neutrophils were pre-treated with IBMX (1mM) then with ATP, ATP-γ-S or BzATP (100μM) or buffer control for 8 minutes prior to lysis and detection of intracellular cAMP. Data is from 3 independent experiments, each assessed in duplicate, and is expressed as fold increase in [cAMP]i compared to buffer control. All 3 compounds caused a significant increase in [cAMP]i. In further experiments, neutrophils were pre-treated for 30 minutes with the P2Y11 receptor antagonist, NF157, at varying concentrations or buffer control, then treated with ATP-γ-S, ATP or buffer for a total incubation time of 5 hours. Apoptosis was then assessed by morphologic criteria and data are expressed as mean±SEM % apoptosis from a minimum of 3 independent experiments, each from a separate donor. (B) Neutrophils were pre-treated with NF157 (0.01-0.5μM) prior to stimulation with ATP-γ-S (1μM). The survival effect of ATP-γ-S was significantly reduced by 0.5μM NF157 (### p <0.001). (C) Neutrophils were pre-treated with NF157 (0.5μM) prior to stimulation with increasing concentrations of ATP-γ-S (0.1-100μM). ATP-γ-S significantly inhibited neutrophil apoptosis at all concentrations compared to control cells (*** p < 0.001). NF157 abrogated the inhibition of apoptosis by ATP-γ-S (# p <0.05, ### p <0.001). (D) Neutrophils were pre-incubated with buffer (open bars) or NF157 (0.5μM) (filled bars) followed by stimulation with ATP (0.5μM) or buffer control. ATP reduced neutrophil apoptosis (*) and this effect was significantly abrogated by NF157 (#). (E) Detection of P2Y11 protein expression by highly-purified neutrophils, with human platelets used as a positive control. In all four donors, P2Y11 is detected as an approximately 45kDa protein.

ATP mediated delay of neutrophil apoptosis is dependent upon cAMP-dependent kinases

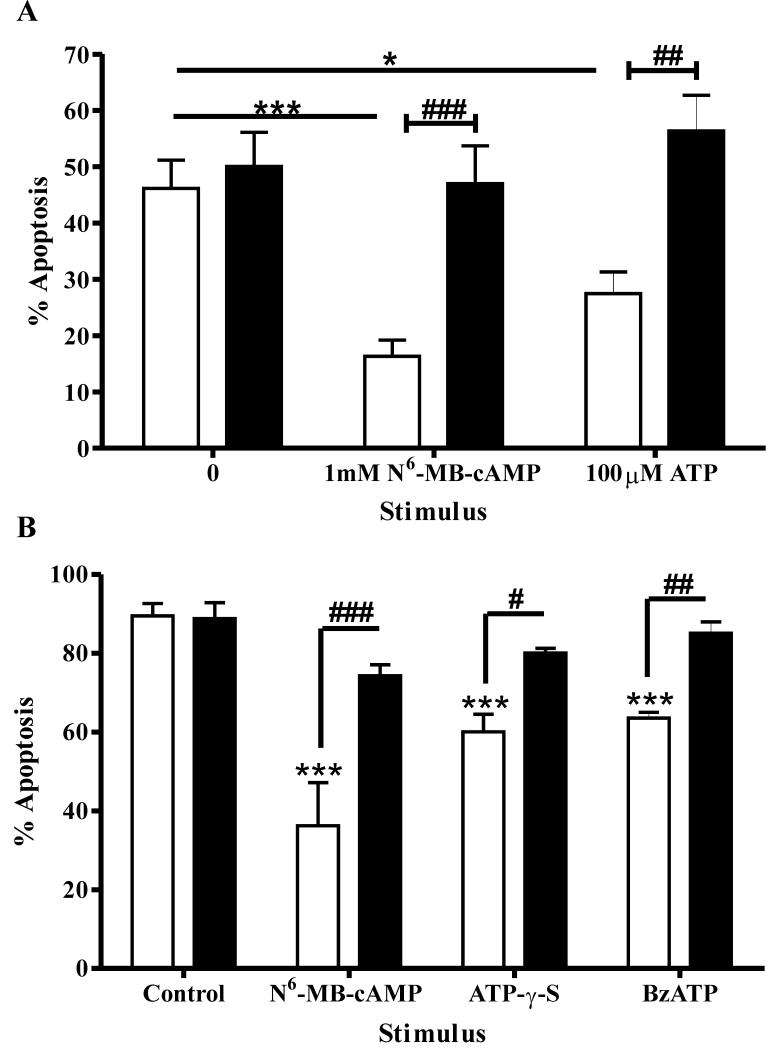

To further confirm a role for P2Y11 in delay of neutrophil apoptosis, we determined the effects of modulating cyclic AMP signalling pathways downstream of P2Y11. Reagents that mediate increases in intracellular cAMP ([cAMP]i) delay neutrophil apoptosis (44). Krakstad et al. (45) have shown the anti-apoptotic effects of cAMP upon neutrophils are mediated by activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinases (cA-PKs), as opposed to the recently discovered cAMP regulated guanosine 5′-triphosphate exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP (Epac). ATP has also been shown to increase [cAMP]i in neutrophils (46). We confirmed the results of Krakstad et al. (45), showing the ability of a cA-PK type I agonist (N6-MB-cAMP) but not an Epac activator (8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP) to cause delay of neutrophil apoptosis equivalent to that seen with the stable cAMP analogue, dibutyryl cAMP (data not shown). We then showed that a specific inhibitor of cA-PK type I (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS) was able to completely abrogate the ATP-mediated survival of neutrophils (Fig. 7A). Moreover, the anti-apoptotic effects of all ATP analogues found to delay neutrophil apoptosis were abolished by the inhibitor, whilst the compound was without effect upon constitutive neutrophil apoptosis (Fig. 7B). We used a 16 hour time point for these experiments, where there would be a sufficiently large inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by ATP (Fig. 1B) for abrogation of these anti-apoptotic effects to be clearly demonstrated. These data confirm that P2Y11-mediated delay of apoptosis is dependent upon activation of cAMP signalling pathways, an effect that is unique to P2Y11 amongst P2 receptors (47).

Figure 7. ATP inhibits neutrophil apoptosis via activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase.

(A) Neutrophils were cultured in the presence or absence of the cA-PK type I agonist N6-MB-cAMP (1mM) or ATP (100μM), alone (open bars) or in combination with a specific cA-PK type I inhibitor, Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (0.7mM) (filled bars), for 16 hours. Apoptosis was assessed by morphologic criteria and data are expressed as mean±SEM % apoptosis from at least 3 independent experiments, each from a separate donor. Rp-8-Br-cAMPS abrogated the enhanced neutrophil survival caused by these treatments (## p <0.01 and ### p <0.001). (B) Similar experiments were performed for two ATP analogues shown to delay neutrophil apoptosis, ATP-γ-S and BzATP (both at 100μM), again using N6-MB-cAMP (1mM) as a positive control. Data are from at least 3 independent experiments, each from a separate donor. The ATP analogues significantly inhibited neutrophil apoptosis and these effects were blocked by Rp-8-Br-cAMPS.

Discussion

Extracellular ATP is a crucial mediator of the inflammatory response, in part through its non-redundant role in activation of P2X7 and thus IL-1 release from macrophages (6, 48). Here, we show that ATP regulates the lifespan of the inflammatory response by a further mechanism: preservation of neutrophil survival. Together with previous work that has shown that ATP can enhance neutrophil functions including degranulation (18) and superoxide production (16), these data place ATP as a multifunctional central regulator of inflammation, whose effects can considerably outlast the period of time for which it is present in the extracellular environment.

We showed that ATP mediates effects upon neutrophil apoptosis at concentrations readily achieved when platelets are activated, or cells are damaged (8). Significant effects were achieved at 1μM ATP and ATP concentrations of up to 250μM have been detected on lytic release from cells (49). Our findings are supported by a previous study showing delay of neutrophil apoptosis by a single concentration of ATP at a single time-point (50). Since ATP is rapidly metabolised by ectonucleases (CD39 and CD73) to adenosine, which is also anti-apoptotic to neutrophils via actions on A2A receptors (29), we confirmed the effects were seen with a non-hydrolysable ATP analogue, ATP-γ-S. Neutrophils themselves have been shown to release ATP, particularly under conditions of hypoxia (51) or hypertonic stress (52), suggesting that ATP may act as an autocrine or paracrine survival factor, prolonging neutrophil lifespan at sites of inflammation.

To determine which receptor mediates the anti-apoptotic effects of ATP, we used a combination of more selective ATP analogues, receptor expression studies and examination of downstream signalling pathways. Of the known P2X receptors, we found neutrophils expressed mRNA for P2X1 and P2X5 but agonist studies, combined with evidence P2X5 may not be functional in humans (38), again made them unlikely candidates. The combination of agonist studies and the lack of requirement for calcium signalling to delay apoptosis made classical P2Y receptors unlikely candidates to mediate the delay of apoptosis. We therefore considered the possibility the anti-apoptotic effect was mediated via P2Y11, which is the only P2 receptor known to mediate cAMP dependent signalling (47). We showed ATP and other analogues causing delay of neutrophil apoptosis also caused increases in intracellular cAMP levels. Moreover, a recently synthesised selective P2Y11 inhibitor, NF157, abrogated the anti-apoptotic effect of ATP and the effects of ATP were also abolished by inhibition of signalling via cAMP-dependent protein kinases, further implicating P2Y11. The delay of apoptosis by ATP analogues was achieved at concentrations in keeping with the described EC50′s for BzATP and ATP-γ-S as agonists of cAMP production in P2Y11 transfected cells (7.2 and 3.4 μM respectively) in complete media (40), although a ten-fold lower EC50 for BzATP has been reported in divalent free media (53). We did not detect a significant rise in intracellular calcium following BzATP treatment of neutrophils. Previous studies have shown increases in HL-60 cells (16) but there are no reports of a calcium rise in neutrophils in response to BzATP. We were able to detect a rise in intracellular calcium in response to ATP, ATP-γ-S and UTP, which will activate P2Y2 receptors at the concentrations used, but did not detect a calcium rise in response to BzATP nor to 2MeSATP which, as a P2Y1 agonist, would also be expected to cause an increase in intracellular calcium via activation of phospholipase C. This suggests the calcium response we detected was predominantly P2Y2 mediated and there is evidence BzATP is only a weak partial agonist at human P2Y2 receptors (54). We have not been able to further demonstrate the role of P2Y11 by study of P2Y11 deficient neutrophils, since, to our knowledge, a P2Y11 deficient mouse has not been developed and because genetic manipulation of primary human neutrophils is notoriously difficult.

P2Y11 is unique as a P2 receptor coupling both to phospholipase C and to adenylate cyclase (39). P2Y11 is expressed on several leukocyte populations, including neutrophils (52), lymphocytes (55), monocytes (34) and monocyte-derived dendritic cells (56), and is associated with maturation of bone marrow precursor populations (57). More recently, P2Y11 was found to be abundantly expressed in the endothelium (58).

In the course of our experiments we found that neutrophils express a limited repertoire of P2X receptors and, in particular, do not express P2X7 at mRNA or protein level in resting or LPS-stimulated cells, in agreement with Chen et al. (15), who also failed to detect P2X7 mRNA. This contrasts with previous studies showing P2X7 expression in human neutrophils at the mRNA level (16, 52) In both these studies, neutrophils were purified using dextran sedimentation and gradient centrifugation, with neutrophil purities of approximately 97%. As shown in Figure 4B, neutrophil populations contaminated with PBMCs can have detectable mRNA for P2X7 as well as P2X4 and P2X6 and this may explain the discrepant results. Gu et al. (59) detected intracellular P2X7 protein expression in human neutrophils. We were unable to detect P2X7 in neutrophils by flow cytometry or by western blotting under conditions where the protein was detected in other cell types. Thus, P2X7 expression may be present at low levels in neutrophils, but it is likely that contamination of neutrophils with PBMC has contributed to a confused picture in which the role of P2X7 may have become overstated. Our data are supported by the finding of Labasi et al. (60) that granulocytes from P2X7 deficient mice showed no lack of shape change or L-selectin shedding in response to ATP, in contrast to monocytes and lymphocytes, which the authors speculated reflected lack of surface expression of P2X7 on neutrophils.

In a number of studies, functional effects of BzATP upon neutrophils have been attributed to P2X7-mediated actions (16, 61). BzATP, however, is also an agonist at other receptors, notably P2Y11 but also P2X1 (38), and the potency of BzATP in delay of neutrophil apoptosis is more in keeping with effects at the P2Y11 receptor (40). We also considered the possibility that ATP may exert its effects on neutrophil apoptosis indirectly, by activation of P2X7 receptors expressed upon mononuclear cells. We have previously shown using highly-purified LPS, a TLR4 agonist, that the anti-apoptotic effect of LPS on human neutrophils is principally mediated via indirect effects upon the small numbers of monocytes present in the cell preparations, inducing release of neutrophil survival factors (22, 62). Importantly, in our studies, the anti-apoptotic effects of ATP were the same in gradient-purified and highly-purified neutrophil populations, supporting the view that ATP and ATP analogues were mediating their anti-apoptotic effects directly upon neutrophils but via a receptor other than P2X7.

Extracellular ATP can cause induction of cell death, either apoptotic or cytolytic, in many cell types e.g. endothelial cells (32), lymphocytes (31), hepatocytes (63). In neutrophils, in contrast, ATP mediates a significant delay of apoptosis. Thus, an environment associated with cell damage and death mediates prolongation of effect of an important cell of the innate immune system, potentially facilitating resolution of tissue injury. The effects of ATP upon neutrophils are, however, dependent upon activation of cA-PK via elevation of intracellular cAMP. cAMP also induces apoptosis in many cell types, including thymocytes (64) and B lymphocytes (65), yet is anti-apoptotic to both neutrophils (44) and eosinophils (66). Krakstad et al. (45) showed cAMP inhibited neutrophil apoptosis by activation of cA-PK type I, the dominant isoform in neutrophils (67). Elevation of cAMP stabilises the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein, Mcl-1, and phosphorylates Bad, providing potential downstream mechanisms of its anti-apoptotic actions (68).

P2X7 has profoundly pro-inflammatory effects upon monocyte-macrophage populations and we now propose that enhancement of neutrophil lifespan, and thus proinflammatory functions since these are regulated by onset of apoptosis (3), is separately regulated via P2Y11. The lack of effect of P2Y11 antagonism on constitutive apoptosis suggests specific targeting of P2Y11 could provide a mechanism that retains key immune functions of neutrophils but reduces the injurious effects of neutrophil longevity at inflamed sites. Further experiments are underway to determine the full consequences of early P2Y11 antagonism on neutrophil phenotypes generated by proinflammatory stimuli. Strategies to selectively “drive” neutrophil apoptosis using cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors (69) have recently shown the potential of this strategy to reduce inflammation in a range of animal models. Importantly, our data suggest that encounters of the neutrophil with ATP in the microvasculature at sites of inflammation, clotting, and tissue damage may induce a prolonged survival phenotype that can be rapidly initiated and subsequently carried into tissues. These data further suggest that P2Y11 antagonists will be most efficacious when administered systemically, and may conceivably deprive the neutrophil of a mechanism important in the generation of a fully-activated tissue neutrophil.

Abbreviations Used in this Paper

- αβMeATP

αβ-methylene-adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- ATP

adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- ATP-γ-S

adenosine 5′-[γ-thio]-triphosphate

- BzATP

2′-3′-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- Ca2+i

intracellular calcium

- cAMPi

intracellular cyclic adenosine-3′,5′-monophosphate

- cA-PK

cAMP-dependent protein kinases

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- JC-1

5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolyl-carbocyanine iodide

- 2MeSATP

2-(methylthio)adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- N6-MB-cAMP

N6-monobutyryladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- NAD

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP

8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- PLC

phospholipase C

- Rp-8-Br-cAMP

Rp-isomer, 8-Bromo-adenosine-3′,5′-cyclicmonophosphorothioate

- U73122

1-(6-((17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,4(10)-trien-17-yl)amino)hexyl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione

- U73343

1-(6-((17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl)amino)hexyl)-2,5-pyrrolidinedione

- UTP

uridine 5′-triphosphate.

Footnotes

This work was funded by a British Heart Foundation PhD Studentship to KRV (Ref. FS/03/125/16306). IS holds a Medical Research Council Senior Clinical Fellowship (G116/170) and AMS is supported by Programme funding from the Wellcome Trust.

References

- 1.Haslett C. Granulocyte apoptosis and inflammatory disease. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:669–683. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savill JS, Wyllie AH, Henson JE, Walport MJ, Henson PM, Haslett C. Macrophage phagocytosis of aging neutrophils in inflammation. Programmed cell death in the neutrophil leads to its recognition by macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:865–875. doi: 10.1172/JCI113970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whyte MK, Meagher LC, MacDermot J, Haslett C. Impairment of function in aging neutrophils is associated with apoptosis. J Immunol. 1993;150:5124–5134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colotta F, Re F, Polentarutti N, Sozzani S, Mantovani A. Modulation of granulocyte survival and programmed cell death by cytokines and bacterial products. Blood. 1992;80:2012–2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee A, Whyte MK, Haslett C. Inhibition of apoptosis and prolongation of neutrophil functional longevity by inflammatory mediators. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;54:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khakh BS, North RA. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature. 2006;442:527–532. doi: 10.1038/nature04886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearson JD, Gordon JL. Vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells in culture selectively release adenine nucleotides. Nature. 1979;281:384–386. doi: 10.1038/281384a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naum CC, Kaplan SS, Basford RE. Platelets and ATP prime neutrophils for enhanced O2- generation at low concentrations but inhibit O2- generation at high concentrations. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;49:83–89. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Born GV, Kratzer MA. Source and concentration of extracellular adenosine triphosphate during haemostasis in rats, rabbits and man. J Physiol. 1984;354:419–429. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubyak GR, El-Moatassim C. Signal transduction via P2-purinergic receptors for extracellular ATP and other nucleotides. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C577–606. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.3.C577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lader AS, Prat AG, Jackson GR, Jr., Chervinsky KL, Lapey A, Kinane TB, Cantiello HF. Increased circulating levels of plasma ATP in cystic fibrosis patients. Clin Physiol. 2000;20:348–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.2000.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donaldson SH, Lazarowski ER, Picher M, Knowles MR, Stutts MJ, Boucher RC. Basal nucleotide levels, release, and metabolism in normal and cystic fibrosis airways. Mol Med. 2000;6:969–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burnstock G. A basis for distinguishing two types of purinergic receptors. In: Straub RW, Bolis L, editors. Cell membrane receptors for drugs and hormones, a multidisciplinary approach. New York: Raven Press; 1978. pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burnstock G, Kennedy C. Is there a basis for distinguishing two types of P2-purinoceptor? Gen Pharmacol. 1985;16:433–440. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(85)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, Nizet V, Insel PA, Junger WG. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suh BC, Kim JS, Namgung U, Ha H, Kim KT. P2X7 nucleotide receptor mediation of membrane pore formation and superoxide generation in human promyelocytes and neutrophils. J Immunol. 2001;166:6754–6763. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cockcroft S, Stutchfield J. ATP stimulates secretion in human neutrophils and HL60 cells via a pertussis toxin-sensitive guanine nucleotide-binding protein coupled to phospholipase C. FEBS Lett. 1989;245:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meshki J, Tuluc F, Bredetean O, Ding Z, Kunapuli SP. Molecular mechanism of nucleotide-induced primary granule release in human neutrophils: role for the P2Y2 receptor. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C264–271. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buell G, Chessell IP, Michel AD, Collo G, Salazzo M, Herren S, Gretener D, Grahames C, Kaur R, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Humphrey PP. Blockade of human P2X7 receptor function with a monoclonal antibody. Blood. 1998;92:3521–3528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ullmann H, Meis S, Hongwiset D, Marzian C, Wiese M, Nickel P, Communi D, Boeynaems JM, Wolf C, Hausmann R, Schmalzing G, Kassack MU. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of suramin-derived P2Y11 receptor antagonists with nanomolar potency. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7040–7048. doi: 10.1021/jm050301p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haslett C, Guthrie LA, Kopaniak MM, Johnston RB, Jr., Henson PM. Modulation of multiple neutrophil functions by preparative methods or trace concentrations of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Am J Pathol. 1985;119:101–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabroe I, Prince LR, Jones EC, Horsburgh MJ, Foster SJ, Vogel SN, Dower SK, Whyte MK. Selective roles for Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 in the regulation of neutrophil activation and life span. J Immunol. 2003;170:5268–5275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Homburg CH, de Haas M, von dem Borne AE, Verhoeven AJ, Reutelingsperger CP, Roos D. Human neutrophils lose their surface FcγRIII and acquire Annexin V binding sites during apoptosis in vitro. Blood. 1995;85:532–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fossati G, Moulding DA, Spiller DG, Moots RJ, White MR, Edwards SW. The mitochondrial network of human neutrophils: role in chemotaxis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst activation, and commitment to apoptosis. J Immunol. 2003;170:1964–1972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowler JW, Bailey RJ, North RA, Surprenant A. P2X4, P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptors on rat alveolar macrophages. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:567–575. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphreys BD, Virginio C, Surprenant A, Rice J, Dubyak GR. Isoquinolines as antagonists of the P2X7 nucleotide receptor: high selectivity for the human versus rat receptor homologues. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:22–32. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ernens I, Rouy D, Velot E, Devaux Y, Wagner DR. Adenosine inhibits matrix metalloproteinase-9 secretion by neutrophils: implication of A2a receptor and cAMP/PKA/Ca2+ pathway. Circ Res. 2006;99:590–597. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000241428.82502.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coade SB, Pearson JD. Metabolism of adenine nucleotides in human blood. Circ Res. 1989;65:531–537. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker BA, Rocchini C, Boone RH, Ip S, Jacobson MA. Adenosine A2a receptor activation delays apoptosis in human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1997;158:2926–2931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cusack NJ, Pearson JD, Gordon JL. Stereoselectivity of ectonucleotidases on vascular endothelial cells. Biochem J. 1983;214:975–981. doi: 10.1042/bj2140975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Virgilio F, Bronte V, Collavo D, Zanovello P. Responses of mouse lymphocytes to extracellular adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP). Lymphocytes with cytotoxic activity are resistant to the permeabilizing effects of ATP. J Immunol. 1989;143:1955–1960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Albertini M, Palmetshofer A, Kaczmarek E, Koziak K, Stroka D, Grey ST, Stuhlmeier KM, Robson SC. Extracellular ATP and ADP activate transcription factor NF-κB and induce endothelial cell apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:822–829. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohanty JG, Raible DG, McDermott LJ, Pelleg A, Schulman ES. Effects of purine and pyrimidine nucleotides on intracellular Ca2+ in human eosinophils: activation of purinergic P2Y receptors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:849–855. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L, Jacobsen SE, Bengtsson A, Erlinge D. P2 receptor mRNA expression profiles in human lymphocytes, monocytes and CD34+ stem and progenitor cells. BMC Immunol. 2004;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theilgaard-Mönch K, Jacobsen LC, Borup R, Rasmussen T, Bjerregaard MD, Nielsen FC, Cowland JB, Borregaard N. The transcriptional program of terminal granulocytic differentiation. Blood. 2005;105:1785–1796. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphreys BD, Dubyak GR. Induction of the P2z/P2X7 nucleotide receptor and associated phospholipase D activity by lipopolysaccharide and IFN-gamma in the human THP-1 monocytic cell line. J Immunol. 1996;157:5627–5637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whyte MK, Hardwick SJ, Meagher LC, Savill JS, Haslett C. Transient elevations of cytosolic free calcium retard subsequent apoptosis in neutrophils in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:446–455. doi: 10.1172/JCI116587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.North RA, Surprenant A. Pharmacology of cloned P2X receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:563–580. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Communi D, Govaerts C, Parmentier M, Boeynaems JM. Cloning of a human purinergic P2Y receptor coupled to phospholipase C and adenylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31969–31973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.31969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Communi D, Robaye B, Boeynaems JM. Pharmacological characterization of the human P2Y11 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chessell IP, Michel AD, Humphrey PP. Effects of antagonists at the human recombinant P2X7 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:1314–1320. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moreschi I, Bruzzone S, Nicholas RA, Fruscione F, Sturla L, Benvenuto F, Usai C, Meis S, Kassack MU, Zocchi E, De Flora A. Extracellular NAD+ is an agonist of the human P2Y11 purinergic receptor in human granulocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31419–31429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Communi D, Suarez-Huerta N, Dussossoy D, Savi P, Boeynaems JM. Cotranscription and intergenic splicing of human P2Y11 and SSF1 genes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16561–16566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossi AG, Cousin JM, Dransfield I, Lawson MF, Chilvers ER, Haslett C. Agents that elevate cAMP inhibit human neutrophil apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;217:892–899. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krakstad C, Christensen AE, Døskeland SO. cAMP protects neutrophils against TNF-α-induced apoptosis by activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, independently of exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:641–647. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0104005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stolc V. Mechanism of regulation of adenylate cyclase activity in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes by calcium, guanosyl nucleotides, and positive effectors. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:1901–1907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qi AD, Kennedy C, Harden TK, Nicholas RA. Differential coupling of the human P2Y11 receptor to phospholipase C and adenylyl cyclase. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:318–326. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di Virgilio F, Chiozzi P, Ferrari D, Falzoni S, Sanz JM, Morelli A, Torboli M, Bolognesi G, Baricordi OR. Nucleotide receptors: an emerging family of regulatory molecules in blood cells. Blood. 2001;97:587–600. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pellegatti P, Falzoni S, Pinton P, Rizzuto R, Di Virgilio F. A novel recombinant plasma membrane-targeted luciferase reveals a new pathway for ATP secretion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3659–3665. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gasmi L, McLennan AG, Edwards SW. The diadenosine polyphosphates Ap3A and Ap4A and adenosine triphosphate interact with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to delay neutrophil apoptosis: implications for neutrophil: platelet interactions during inflammation. Blood. 1996;87:3442–3449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eltzschig HK, Abdulla P, Hoffman E, Hamilton KE, Daniels D, Schönfeld C, Löffler M, Reyes G, Duszenko M, Karhausen J, Robinson A, Westerman KA, Coe IR, Colgan SP. HIF-1-dependent repression of equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT) in hypoxia. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1493–1505. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y, Shukla A, Namiki S, Insel PA, Junger WG. A putative osmoreceptor system that controls neutrophil function through the release of ATP, its conversion to adenosine, and activation of A2 adenosine and P2 receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:245–253. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chessell IP, Simon J, Hibell AD, Michel AD, Barnard EA, Humphrey PP. Cloning and functional characterisation of the mouse P2X7 receptor. FEBS Lett. 1998;439:26–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts VH, Greenwood SL, Elliott AC, Sibley CP, Waters LH. Purinergic receptors in human placenta: evidence for functionally active P2X4, P2X7, P2Y2, and P2Y6. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1374–1386. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00612.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Conigrave AD, Fernando KC, Gu B, Tasevski V, Zhang W, Luttrell BM, Wiley JS. P2Y11 receptor expression by human lymphocytes: evidence for two cAMP-linked purinoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;426:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berchtold S, Ogilvie AL, Bogdan C, Mühl-Zürbes P, Ogilvie A, Schuler G, Steinkasserer A. Human monocyte derived dendritic cells express functional P2X and P2Y receptors as well as ecto-nucleotidases. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:424–428. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Weyden L, Rakyan V, Luttrell BM, Morris MB, Conigrave AD. Extracellular ATP couples to cAMP generation and granulocytic differentiation in human NB4 promyelocytic leukaemia cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:467–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2000.t01-4-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang L, Karlsson L, Moses S, Hultgårdh-Nilsson A, Andersson M, Borna C, Gudbjartsson T, Jern S, Erlinge D. P2 receptor expression profiles in human vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2002;40:841–853. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gu BJ, Zhang WY, Bendall LJ, Chessell IP, Buell GN, Wiley JS. Expression of P2X7 purinoceptors on human lymphocytes and monocytes: evidence for nonfunctional P2X7 receptors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1189–1197. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.4.C1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Labasi JM, Petrushova N, Donovan C, McCurdy S, Lira P, Payette MM, Brissette W, Wicks JR, Audoly L, Gabel CA. Absence of the P2X7 receptor alters leukocyte function and attenuates an inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2002;168:6436–6445. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nagaoka I, Tamura H, Hirata M. An antimicrobial cathelicidin peptide, human CAP18/LL-37, suppresses neutrophil apoptosis via the activation of formyl-peptide receptor-like 1 and P2X7. J Immunol. 2006;176:3044–3052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sabroe I, Jones EC, Usher LR, Whyte MK, Dower SK. Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 in human peripheral blood granulocytes: a critical role for monocytes in leukocyte lipopolysaccharide responses. J Immunol. 2002;168:4701–4710. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nicotera P, Hartzell P, Davis G, Orrenius S. The formation of plasma membrane blebs in hepatocytes exposed to agents that increase cytosolic Ca2+ is mediated by the activation of a non-lysosomal proteolytic system. FEBS Lett. 1986;209:139–144. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anderson KL, Anderson G, Michell RH, Jenkinson EJ, Owen JJ. Intracellular signaling pathways involved in the induction of apoptosis in immature thymic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1996;156:4083–4091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lømo J, Blomhoff HK, Beiske K, Stokke T, Smeland EB. TGF-β1 and cyclic AMP promote apoptosis in resting human B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1995;154:1634–1643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hallsworth MP, Giembycz MA, Barnes PJ, Lee TH. Cyclic AMP-elevating agents prolong or inhibit eosinophil survival depending on prior exposure to GM-CSF. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:79–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parvathenani LK, Buescher ES, Chacon-Cruz E, Beebe SJ. Type I cAMP-dependent protein kinase delays apoptosis in human neutrophils at a site upstream of caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6736–6743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kato T, Kutsuna H, Oshitani N, Kitagawa S. Cyclic AMP delays neutrophil apoptosis via stabilization of Mcl-1. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4582–4586. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rossi AG, Sawatzky DA, Walker A, Ward C, Sheldrake TA, Riley NA, Caldicott A, Martinez-Losa M, Walker TR, Duffin R, Gray M, Crescenzi E, Martin MC, Brady HJ, Savill JS, Dransfield I, Haslett C. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors enhance the resolution of inflammation by promoting inflammatory cell apoptosis. Nat Med. 2006;12:1056–1064. doi: 10.1038/nm1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]