Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to determine whether there is a relationship between grip strength and features of the metabolic syndrome.

Methods

A cross-sectional study within a cohort design was used and data were collected on grip strength, fasting glucose, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol, blood pressure, waist circumference and 2 hour glucose after an oral glucose tolerance test in a population based sample of 2677 men and women aged 59 – 73 years.

Results

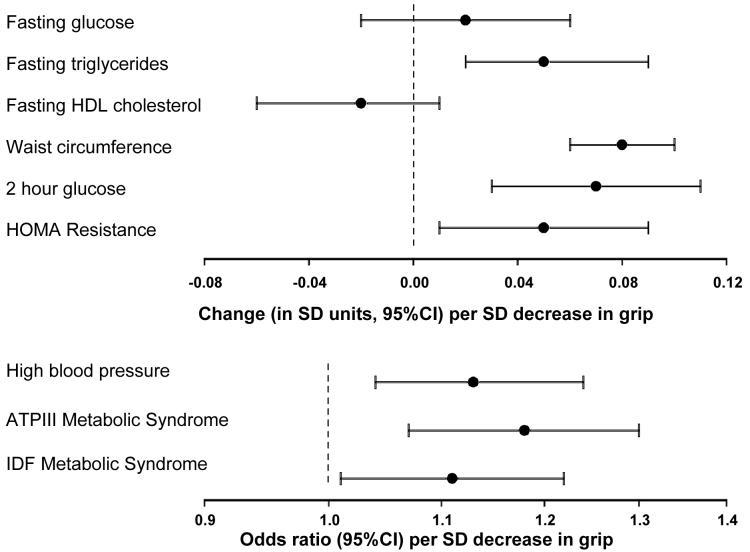

In men and women combined, a standard deviation (SD) decrease in grip strength was significantly associated with higher: fasting triglycerides (0.05 SD unit increase [95%CI 0.02, 0.09], p=0.006); blood pressure (odds ratio [OR] 1.13 [95%CI 1.04, 1.24], p=0.004); waist circumference (0.08 SD unit increase [95%CI 0.06, 0.10], p<0.001); 2 hour glucose (0.07 SD unit increase [95%CI 0.03, 0.11], p=0.001) and HOMA resistance (0.05 SD unit increase [95%CI 0.01, 0.09], p=0.008) after adjustment for gender, weight, age, walking speed, social class, smoking habit and alcohol intake. Furthermore lower grip was significantly associated with increased odds of having the metabolic syndrome according to the ATPIII (OR 1.18 [95%CI 1.07, 1.30], p<0.001) and IDF definitions (OR 1.11 [95%CI 1.01, 1.22], p=0.03).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that impaired grip strength is associated with the individual features as well as with the overall summary definitions of metabolic syndrome. The potential for grip strength to be used in the clinical setting needs to be explored.

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome, human, epidemiology

Introduction

Recent work has shown that sarcopenia, the loss of muscle mass and strength with age, is significantly associated with type 2 diabetes in older people1;2 in addition to the well documented relationships with falls, fractures, disability and mortality3-6. Furthermore the findings suggested a graded association between increased glucose level and weaker muscle strength in those with impaired glucose tolerance and normal levels of blood glucose. This is important because it suggests that there may be a link between the mechanical and metabolic functions of ageing muscle. The mechanism is unclear but sarcopenia and insulin resistant states share common cellular and molecular changes. For example both are associated with the accumulation of myofibre lipids7;8 which may affect the insulin-signalling pathway9. In addition, an impaired synthesis rate of key structural muscle proteins such as the myosin heavy chain10, for example in response to anabolic post-prandial stimuli11, is seen with both ageing and insulin resistance.

The link between impaired mechanical and metabolic function may extend to other important insulin resistant glucose intolerant states such as central obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is defined as a clustering of inter-related metabolic risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes and it has an estimated world-wide prevalence of 16% in adults over the age of 20 years12. The objective of this study was to determine whether there is a relationship between sarcopenia as characterised by grip strength13 and the constellation of risk factors of metabolic origin that constitute the metabolic syndrome.

Methods

In 1998, 3822 men and 3284 women born in Hertfordshire United Kingdom between 1931 and 1939 were traced with the aid of the National Health Service central registry in Southport and confirmed as currently registered with a family doctor in Hertfordshire. Permission to contact 3126 (82%) men and 2973 (91%) women was obtained from their General Practitioners. 1684 (54%) men and 1541 (52%) women agreed to take part in a home interview and provided information on medical and social history, including self-reported customary walking speed (unable to walk, very slow, stroll at an easy pace, normal speed, fairly brisk, fast) as a marker of physical activity14, smoking habit, alcohol consumption and current use of prescribed medications.

1579 (94%) of the men and 1418 (92%) of the women interviewed at home subsequently attended a clinic. Those who were not previously known to be diabetic (1471 men and 1344 women) attended after an overnight fast. Fasting plasma samples were taken for triglyceride, HDLc, total cholesterol, calculated LDLc, glucose and insulin concentrations. Plasma lipids and glucose were measured by standard methods on an Advia 1650 autoanalyser (Bayer Diagnostics, Newbury, UK). Intact insulin was measured by an in-house immunofluorimetric two-site assay (‘DELFIA’ system) based on published methods15. An index of insulin resistance was derived using the HOMA formula16. An oral glucose tolerance test was performed using the equivalent of 75g anhydrous glucose, with blood samples for plasma glucose and insulin obtained at 30 and 120 minutes. Diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance were classified on 1454 men and 1317 women using WHO criteria i.e. 2 hour glucose concentration of ≥11.1mmol/l and 7.0-11.0mmol/l respectively (17 men and 27 women were unclassified due to missing data).17

Height was measured to the nearest 0.1cm using a Harpenden pocket stadiometer, and weight to the nearest 0.1kg on a SECA floor scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by height2 (kg/m2). Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. Skinfold thickness (SFT) was measured with Harpenden skinfold calipers in triplicate at the triceps, biceps, sub-scapular and supra-iliac sites on the non-dominant side18. Average measures were used to derive body fat percentage19. Fat mass was derived by multiplying body weight by body fat percentage, and non-fat mass by subtracting fat mass from body weight. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured three times in the right arm using an automated Dinamap recorder with the participant in a seated position after having rested for five minutes. The average of the three readings was taken and high blood pressure was defined as average systolic pressure ≥160mmHg and/or diastolic pressure ≥90mmHg, or current use of prescribed anti-hypertensives. Presence or absence of the metabolic syndrome was identified for each individual on the basis of the International Diabetes Foundation (IDF) and Adult Treatment Panel III (ATPIII) definitions of the metabolic syndrome. These definitions require differing cut-offs and combinations of increased body weight, increased triglyceride and decreased HDL-cholesterol levels, raised blood pressure and increased glucose levels12. Grip strength was measured three times on each side using a Jamar handgrip dynamometer20. The best of the six grip measurements was used to characterise maximum muscle strength. 1438 men and 1239 women had data available for grip strength and all of the data items required to code HOMA resistance and the IDF and ATPIII definitions of the metabolic syndrome; these 2,677 men and women comprised the sample for this study. The study had ethical approval from the North and East Hertfordshire Local Research Ethics Committee and all subjects gave written informed consent.

Statistical methods

Normality of variables was assessed and weight, BMI, fat mass, fasting glucose, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, 2 hour glucose, and HOMA resistance were loge transformed for statistical analyses. Variables were summarised for men and women separately using means and standard deviations or frequency and percentage distributions. Means and standard deviations for loge-transformed variables were back transformed to geometric means and standard deviations on the original scale of measurement. All subsequent analyses were conducted for men and women combined with adjustment for gender.

Relationships between anthropometry (weight, height, BMI and fat mass) and components of the metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and grip strength were analysed using partial correlation coefficients and analysis of variance (ANOVA). These analyses enabled an assessment of the potential confounding influence of anthropometric status on the relationships between grip strength and components of the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance.

Sex-specific standard-deviation (SD) scores were calculated for grip strength and fasting glucose, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, waist circumference, 2 hour glucose and HOMA resistance. The relationships between an SD decrease in grip strength and each of these SD scores were explored using multiple linear regression. These regression models yielded estimated changes (and 95% confidence intervals) in SD units for each component of the metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance per SD decrease in grip strength. The relationships between an SD decrease in grip strength and the binary variables representing high blood pressure and the ATPIII and IDF definitions of the metabolic syndrome, were analysed using multiple logistic regression. These logistic regression models yielded odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) for high blood pressure, or each definition of the metabolic syndrome, per SD decrease in grip strength. We tested for homogeneity of the association between grip strength and each component of the metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance in men and women, by including an interaction term for gender and grip strength SD score in each linear or logistic regression model.

All statistical analyses were carried out using Stata, release 8 (StataCorp, 2003).

Results

The characteristics of the study group are displayed in Table 1. Average grip strength was 44.3kg for men and 26.7kg for women. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome was 31.1% for men and 33.6% for women according to the ATPIII definition, and was 50.3% for men and 49.6% for women according to the IDF definition.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of study participants

|

Characteristic Mean (SD) unless stated otherwise |

Men (n=1438) |

Women (n=1239) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.7 (2.9) | 66.6 (2.7) |

| Grip strength (kg) | 44.3 (7.4) | 26.7 (5.7) |

| N (%) Non-manual social classa | 567 (39.4) | 523 (42.2) |

| N (%) Moderate/high alcohol consumptionb | 631 (43.9) | 204 (16.5) |

| N (%) Current smoker | 223 (15.5) | 116 (9.4) |

| Walking speed N (%) | ||

| Slow | 58 (4.0) | 75 (6.1) |

| Average | 905 (63.0) | 802 (64.7) |

| Fast | 474 (33.0) | 362 (29.2) |

| Weight (kg)c | 81.1 (1.2) | 69.7 (1.2) |

| Height (cm) | 174.2 (6.5) | 160.8 (5.9) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)c | 26.8 (1.1) | 27.0 (1.2) |

| Body-fat percentage | 28.6 (5.3) | 39.7 (4.8) |

| Fat mass (kg)c | 22.8 (1.4) | 27.5 (1.3) |

| Non-fat mass (kg) | 58.1 (6.7) | 42.3 (5.9) |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l)c | 6.0 (1.2) | 5.8 (1.1) |

| Fasting triglycerides (mmol/l)c | 1.45 (1.62) | 1.46 (1.56) |

| Fasting HDL cholesterol (mmol/l)c | 1.32 (1.27) | 1.66 (1.28) |

| N(%) high blood pressured | 540 (37.6) | 488 (39.4) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 100.2 (10.4) | 91.6 (12.3) |

| 2 hour glucose (mmol/l)c | 6.8 (1.4) | 7.4 (1.4) |

| HOMA Resistancec | 2.79 (2.07) | 2.56 (1.92) |

| N(%) ATPIII Metabolic Syndrome | 447 (31.1) | 416 (33.6) |

| N(%) IDF Metabolic Syndrome | 723 (50.3) | 614 (49.6) |

Classes IIIM, IV and V of the 1990 OPCS Standard Occupational Classification scheme for occupation and social class.

11 units or more per week for men, and 8 units or more per week for women.

Geometric means and SDs.

Defined as high measured blood pressure (systolic pressure ≥160mmHg or diastolic ≥100mmHg) or use of antihypertensive therapy

The associations between anthropometric status (weight, height, BMI and fat mass) and components of the metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and grip strength are shown in Table 2. Weight was positively associated with grip strength and components of the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance; it therefore had the potential to negatively confound (i.e. to mask) any relationship between lower grip strength and the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. Fat mass showed a similar pattern of associations and of the two closely related anthropometric measures, weight was used in the final multiple regression analysis as it was more strongly related to grip strength. Height was strongly and positively associated with grip strength but not consistently with components of the metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance. Conversely, BMI was strongly associated with components of the metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance but not with grip strength. Therefore, neither height nor BMI were likely to act as confounders of the relationship between grip strength and the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance and were not included in the final multiple regression analysis.

Table 2.

Relationships between grip strength, components of the metabolic syndrome and anthropometric characteristics of study participants

| Partial correlation coefficienta or average differenceb (95%CI) in anthropometric characteristic |

Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | BMI (kg/m2) | Fat mass (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grip strength (kg) | 0.19 p<0.001 |

0.35 p<0.001 |

0.03 p=0.12 |

0.13 p<0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 0.24 p<0.001 |

−0.00 p=0.84 |

0.27 p<0.001 |

0.25 p<0.001 |

| Fasting triglycerides (mmol/l) | 0.30 p<0.001 |

−0.01 p=0.53 |

0.33 p<0.001 |

0.33 p<0.001 |

| Fasting HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | −0.32 p<0.001 |

−0.03 p=0.14 |

−0.34 p<0.001 |

−0.34 p<0.001 |

| High blood pressure (yes vs no) | 5.8 (4.4,7.1)+ p<0.001 |

−0.6 (−1.1,−0.1) p=0.02 |

6.5 (5.3, 7.7)+ p<0.001 |

11.6 (9.0, 14.2)+ p<0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.87 p<0.001 |

0.12 p<0.001 |

0.89 p<0.001 |

0.85 p<0.001 |

| 2 hour glucose (mmol/l) | 0.22 p<0.001 |

−0.10 p<0.001 |

0.29 p<0.001 |

0.27 p<0.001 |

| HOMA Resistance | 0.42 p<0.001 |

0.01 p=0.73 |

0.45 p<0.001 |

0.46 p<0.001 |

| ATPIII Metabolic Syndrome (yes vs no) |

17.4 (16.0,18.8)+ p<0.001 |

0.4 (−0.1, 0.9) p=0.15 |

16.9 (15.7, 18.2) + p<0.001 |

34.0 (31.1, 36.9)+ p<0.001 |

| IDF Metabolic Syndrome (yes vs no) |

16.0 (14.7,17.3)+ p<0.001 |

0.1 (−0.3, 0.6) p=0.54 |

15.8 (14.6, 17.0)+ p<0.001 |

32.3 (29.6, 35.1)+ p<0.001 |

Partial correlations adjusted for gender

Average differences and 95% confidence intervals adjusted for gender

Weight, BMI and fat mass were loge transformed for analyses. Percentage differences are therefore presented for these variables according to high blood pressure, ATPIII, and IDF metabolic syndrome

The associations between grip strength and components of the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance are presented in Table 3. The table presents results from two sets of linear and logistic regression models: firstly, models adjusted for gender only (Model 1) and secondly, models adjusted for the potential confounding influences of gender, weight, age, walking speed as a marker of physical activity, social class, smoking habit and alcohol intake (Model 2). We tested for homogeneity of the association between grip strength and each component of the metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance in men and women, by including an interaction term for gender and grip strength in the first set of models (Model 1). In general, the associations were homogenous in men and women and it was therefore appropriate to have pooled men and women (p-values for homogeneity: p=0.02 for fasting glucose; p=0.36 for triglycerides; p=0.36 for HDL; p=0.35 for high blood pressure; p=0.04 for waist circumference; p=0.96 for 2 hour glucose; p=0.88 for HOMA resistance; p=0.75 for ATPIII metabolic syndrome and p=0.71 for IDF metabolic syndrome).

Table 3.

Relationships between grip strength and components of the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance

| Change in Met S or IR component (in SD units, 95%CI) per SD decrease in grip strength |

Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting glucose (SDS) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) p=0.63 |

0.02 (−0.02, 0.06) p=0.38 |

| Fasting triglycerides (SDS) | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) p=0.49 |

0.05 (0.02, 0.09) p=0.006 |

| Fasting HDL cholesterol (SDS) | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.06) p=0.37 |

−0.02 (−0.06, 0.01) p=0.20 |

| High blood pressure (yes vs no)* | 1.15 (1.07, 1.25) p<0.001 |

1.13 (1.04, 1.24) p=0.004 |

| Waist circumference (SDS) | −0.05 (−0.09, −0.01) p=0.01 |

0.08 (0.06, 0.10) p<0.001 |

| 2 hour glucose (SDS) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.11) p=0.001 |

0.07 (0.03, 0.11) p=0.001 |

| HOMA Resistance (SDS) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) p=0.58 |

0.05 (0.01, 0.09) p=0.008 |

| ATPIII Metabolic Syndrome* (yes vs no) |

1.00 (0.92, 1.09) p=0.97 |

1.18 (1.07, 1.30) p<0.001 |

| IDF Metabolic Syndrome* (yes vs no) |

0.96 (0.89, 1.04) p=0.32 |

1.11 (1.01, 1.22) p=0.03 |

SDS = standard deviation score; Met S = metabolic syndrome; IR = insulin resistance; 95%CI = 95% confidence interval

Values are odds ratios (95%CI) for high blood pressure, or metabolic syndrome, per kg decrease in grip strength

Model 1: adjusted for gender

Model 2: adjusted for gender, weight, age, walking speed, social class, smoking habit and alcohol intake

Only high blood pressure, waist circumference and 2 hour glucose were related to grip strength in gender-adjusted analyses (Model 1). However, also adjusting for weight (which was expected to act as a negative confounder as described above), age, walking speed, social class, smoking habit and alcohol intake (Model 2) revealed associations between lower grip strength and a wide range of components of the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance (Figure 1). Specifically, a standard deviation (SD) decrease in grip strength was significantly associated with higher: fasting triglycerides (0.05 SD unit increase [95%CI 0.02, 0.09], p=0.006); blood pressure (odds ratio [OR] 1.13 [95%CI 1.04, 1.24], p=0.004); waist circumference (0.08 SD unit increase [95%CI 0.06, 0.10], p<0.001); 2 hour glucose (0.07 SD unit increase [95%CI 0.03, 0.11], p=0.001); HOMA resistance (0.05 SD unit increase [95%CI 0.01, 0.09], p=0.008) and with increased odds of having the metabolic syndrome according to the ATPIII (OR 1.18 [95%CI 1.07, 1.30], p<0.001) and IDF definitions (OR 1.11 [95%CI 1.01, 1.22], p=0.03).

Figure 1. Relationships between grip strength and components of the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance.

All estimates adjusted for gender, weight, age, walking speed, social class, smoking habit and alcohol intake. SD=standard deviation; 95%CI=95% confidence interval.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that lower grip strength as a marker of sarcopenia is associated with individual features of the metabolic syndrome including higher fasting triglycerides, blood pressure and waist circumference as well as with the overall ATPIII and IDP summary definitions. Furthermore lower grip strength was associated with insulin resistance in terms of higher 2 hour glucose levels and HOMA resistance. These findings were independent of weight, level of physical activity and age within the narrow age range studied.

Few studies to date have examined loss of muscle mass and strength with insulin resistance, although a large number of studies have described the loss of muscle mass and strength with age. At the cellular level, this is explained by a reduction in both the number and size of myocytes. This has potential for adverse metabolic consequences in terms of reduced glucose uptake and hyperglycaemia because the transporter protein GLUT4 expression at the plasma membrane is related to fibre volume in human skeletal muscle fibres21. It has been proposed that hyperglycaemia has a direct adverse effect on muscle contractile function and force generation22;23. For example it has been proposed that a hyperglycaemia-driven increase in flux through the polyol pathway with increased production of sugar alcohols results in slowing of muscle fibre contraction and relaxation24.

Furthermore prolonged hyperglycaemia can result in non-enzymatic glycosylation of intracellular and extracellular proteins. Glycation of myosin, the molecular motor protein in skeletal muscle that converts chemical energy into mechanical work, has been associated with altered structural and functional properties of the protein25. Our study is cross-sectional therefore it is not possible to ascertain the direction of the association between muscle strength and metabolic function but it is possible that influences in both directions are important. Longitudinal and interventional studies are required to investigate this further.

Age-related processes such as impaired mitochondrial function may also be important. Mitochondrial dysfunction has recently been related to the development of insulin resistance26, type 2 diabetes and obesity27. A key master regulator of metabolism is PGC-1 that is a co-activator of the insulin sensitising nuclear factor PPARg. PGC-1 also regulates mitochondrial biogenesis by directly associating with the orphan nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor-alpha (ERR-alpha). PGC-1alpha and ERR-alpha are both present at high levels in skeletal muscle28. PGC 1a is not only key to mitochondrial biogenesis and function but also enhances slow twitch oxidative muscle fibres in rodents by cooperating with transcription factors Mef2 and FKHR to enhance calcineurin signalling and terminal muscle differentiation29;30.Thus insulin resistant states are closely linked with key regulators of mitochondrial function and muscle structure.

We have considered potential caveats to the interpretation of our findings. Losses to follow up occurred and response bias may have been introduced. However we were able to characterise those who did not take part in the study in a number of ways and demonstrate that with the exception of smoking participants and non-participants were similar. Also comparisons were internal, therefore unless the relationship between glucose concentration and adult grip strength differed between those who did and did not come to clinic, no bias should have been introduced. The relationships were more consistent between grip strength and metabolic syndrome defined by the ATPIII than the IDF criteria. The reasons are unclear but may reflect the narrower inclusion criteria for the ATPIII definition as evidenced by the lower prevalence for metabolic syndrome defined this way.

In conclusion, grip strength is significantly associated with major features of the metabolic syndrome as well as insulin resistance in this population-based study of older men and women. The underlying mechanisms require investigation and our results need to be verified in younger populations and different ethnic groups. Our study provides evidence that impaired grip strength is associated with an adverse metabolic profile in addition to loss of physical function and the potential for grip strength to be used in the clinical setting needs to be explored. Furthermore these data suggest that interventions should be tested that are designed to improve muscle strength per se . These interventions may have wider advantages than previously appreciated to attenuate the impact of metabolic syndrome.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Medical Research Council UK and the University of Southampton UK.

References

- 1.Sayer AA, Dennison EM, Syddall HE, Gilbody HJ, Phillips DI, Cooper C. Type 2 diabetes, muscle strength, and impaired physical function: the tip of the iceberg? Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2541–2. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cetinus E, Buyukbese MA, Uzel M, Ekerbicer H, Karaoguz A. Hand grip strength in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;70:278–86. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wickham C, Cooper C, Margetts BM, Barker DJ. Muscle strength, activity, housing and the risk of falls in elderly people. Age Ageing. 1989;18:47–51. doi: 10.1093/ageing/18.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper C, Barker DJ, Wickham C. Physical activity, muscle strength, and calcium intake in fracture of the proximal femur in Britain. BMJ. 1988;297:1443–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6661.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sayer AA, Syddall HE, Martin HJ, Dennison EM, Roberts HC, Cooper C. Is grip strength associated with health-related quality of life? Findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age Ageing. 2006;35:409–15. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gale CR, Martyn CN, Cooper C, Sayer AA. Grip strength, body composition, and mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:228–35. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen I, Ross R. Linking age-related changes in skeletal muscle mass and composition with metabolism and disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9:408–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furler SM, Poynten AM, Kriketos AD, Lowy AJ, Ellis BA, Maclean EL, et al. Independent influences of central fat and skeletal muscle lipids on insulin sensitivity. Obes.Res. 2001;9:535–43. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shulman GI. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:171–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair KS. Aging muscle. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:953–63. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasmussen BB, Fujita S, Wolfe RR, Mittendorfer B, Roy M, Rowe VL, et al. Insulin resistance of muscle protein metabolism in aging. FASEB J. 2006;20:768–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4607fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lauretani F, Russo CR, Bandinelli S, Bartali B, Cavazzini C, Di Iorio A, et al. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility: an operational diagnosis of sarcopenia. J Appl.Physiol. 2003;95:1851–60. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00246.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dallosso HM, Morgan K, Bassey EJ, Ebrahim SB, Fentem PH, Arie TH. Levels of customary physical activity among the old and the very old living at home. J Epidemiol.Community Health. 1988;42:121–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.42.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobey WJ, Beer SF, Carrington CA, Clark PM, Frank BH, Gray IP, et al. Sensitive and specific two-site immunoradiometric assays for human insulin, proinsulin, 65-66 split and 32-33 split proinsulins. Biochem.J. 1989;260:535–41. doi: 10.1042/bj2600535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1487–95. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Report of a WHO consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. Part I: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fidanza F. Anthropometric methodology. In: Fidanza F, editor. Nutritional status assessment. London: Chapman Hall; 1991. pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durnin JV, Womersley J. Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: measurements on 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years. Br J Nutr. 1974;32:77–97. doi: 10.1079/bjn19740060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathiowetz V, Kashman N, Volland G, Weber K, Dowe M, Rogers S. Grip and pinch strength: normative data for adults. Arch.Phys.Med Rehabil. 1985;66:69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaster M, Vach W, Beck-Nielsen H, Schroder HD. GLUT4 expression at the plasma membrane is related to fibre volume in human skeletal muscle fibres. APMIS. 2002;110:611–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2002.1100903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helander I, Westerblad H, Katz A. Effects of glucose on contractile function, [Ca2+]i, and glycogen in isolated mouse skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C1306–C1312. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00490.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lesniewski LA, Miller TA, Armstrong RB. Mechanisms of force loss in diabetic mouse skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:493–500. doi: 10.1002/mus.10468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cotter MA, Cameron NE. Metabolic, neural and vascular influences on muscle function in experimental models of diabetes mellitus and related pathologica states. Basic & Applied Myology. 1994;4:293–307. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramamurthy B, Jones AD, Larsson L. Glutathione reverses early effects of glycation on myosin function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C419–C424. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00502.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen KF, Befroy D, Dufour S, Dziura J, Ariyan C, Rothman DL, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the elderly: possible role in insulin resistance. Science. 2003;300:1140–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1082889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelley DE, He J, Menshikova EV, Ritov VB. Dysfunction of mitochondria in human skeletal muscle in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:2944–50. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichida M, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Identification of a specific molecular repressor of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma Coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1alpha) J Biol.Chem. 2002;277:50991–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang JH, Lin KH, Shih CH, Chang YJ, Chi HC, Chen SL. Myogenic bHLH proteins regulate the expression of PPAR{gamma} coactivator -1{alpha} Endocrinology. 2006 doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin J, Wu H, Tarr PT, Zhang CY, Wu Z, Boss O, et al. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature. 2002;418:797–801. doi: 10.1038/nature00904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]