Abstract

Patient choice is much talked about in the NHS and other health systems but action has been limited. Vidhya Alakeson argues that piloting individual healthcare budgets would signal real commitment to creating patient centred care

As the burden of disease shifts from acute to chronic care, governments are having to reshape health services. The UK health white paper, Our Health, Our Care, Our Say, published in January 2006, outlines four goals: greater prevention and early intervention, more choice and a louder voice for patients, more support for people with long term needs, and tackling inequalities. Other countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development have stated similar objectives. If governments are serious about these aims, they would do well to learn from recent innovation in social care. In the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, the United States, and Germany, the delivery of social care services is being transformed through the introduction of individualised funding mechanisms, such as direct payments and individual budgets. These mechanisms allow services to be more accurately tailored to individual needs and could particularly benefit patients needing long term health care.

UK social care experience

The UK introduced direct payments for social care in 1996 for disabled adults above the age of 16 years, elderly people, and carers of disabled children.1 The value of a direct payment can vary from a few thousand pounds to over one hundred thousand pounds depending on the severity of the person’s needs.2 Thirteen local authorities are piloting individual budgets, which go a step further towards integrating support for people needing long term care by combining six different funding streams into one budget, with the exception of NHS funding.3

Direct payments and individual budgets operate slightly differently, but the basic approach is the same: instead of receiving services organised and provided by a local authority, individuals receive the cash value of those services and organise and purchase their own care. They usually receive support in deciding how to spend their money from a local authority employed coordinator or from a user-led organisation, such as an independent living centre, which provides support and services to help disabled people live independently.

Direct payments and individual budgets hand control to service users and give them the flexibility to tailor care to meet their specific needs. Flexibility of this kind greatly improves satisfaction and outcomes for individual budget holders. For example, in early pilots of individual budgets with 60 people in six local authorities (Essex, Gateshead, Redcar, Cleveland, South Gloucestershire, West Sussex, and Wigan) beginning in 2003, satisfaction with services rose from 48% to 100% over two years. In the same two years, the 10 people who were in registered care at the beginning of the pilot moved into their own home.4 A randomised controlled trial of a similar programme in the US found that the health of participants with an individual budget was as good or better than those who continued to receive traditional services.5 Furthermore, services purchased directly by individuals to meet personal care or transportation needs, for example, have been found to cost 20-40% less than the equivalent services provided by local authorities.6

Although the evidence from social care is overwhelmingly positive and individual budgets are increasingly mainstream,7 scepticism remains that similar benefits are possible from expanding individualised funding into the NHS. There are doubts about the capacity of people without clinical training to make sound decisions when it comes to the more complex environment of healthcare. Many people are also concerned that this lack of capacity will unduly disadvantage less well educated and less well off patients, further exacerbating existing inequalities within the NHS.8 They worry that putting NHS resources into the hands of the average citizen will encourage, at worst, fraud and, at best, poor use of scarce public funds.

US individualised funding models for mental health

Early evidence from pilots in the US suggests that much of this scepticism is misplaced. Several US states, including Florida, Michigan, and Oregon, are piloting individual budgets for patients with serious mental illness.9 In some cases, these pilots allow participants to choose their own combination of clinical and non-clinical support services, with crisis and emergency services being provided as usual. The individual budgets are funded from state and federal resources and are calculated according to need. Personal income has no bearing on the size of the budget.

The table shows how participants in the Florida mental health programme, known as self directed care, chose to spend their budgets of $3700 (₤1800; €2300) a year. Self directed care began in 2002 and currently serves around 250 people who have a mental disorder.10 The largest spending categories continue to be traditional psychiatric services, such as psychiatrist visits and counselling. However, close to two thirds of overall spending requests are for services that would not traditionally be considered mental health treatment or even health care—for example, household items to improve an individual’s living environment and promote housing stability. This reflects the broad and highly individualised conception that patients have of their health needs and the services that best address them.

Number of purchases made by category by 90 participants in self directed care programme, Florida, January 2005-March 2007*

| Category | No (%) of requests for reimbursement (n=1259) |

|---|---|

| Medication | 206 (16) |

| Transport | 164 (13) |

| Psychiatrist visits | 147 (12) |

| Counselling | 96 (8) |

| Rent and utilities | 91 (7) |

| Dental services | 83 (7) |

| Personal appearance | 78 (6) |

| Information technology | 76 (6) |

| Other therapies | 58 (5) |

| Physical fitness | 53 (4) |

| Other hobbies | 41 (3) |

| Vision services | 40 (3) |

| Education | 40 (3) |

| Arts and crafts | 24 (2) |

| Food | 23 (2) |

| Household items | 17 (1) |

| Medical other | 17 (1) |

| Employment related | 5 (0.4) |

*Based on data from District 8 programme office.

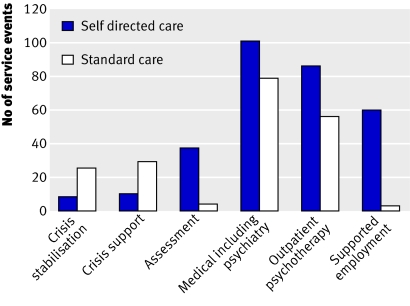

Initial findings indicate that giving patients greater control over their care improves satisfaction and reduces the use of crisis related services.11 Analysis of service use in 2005 shows self directed care participants used crisis support and crisis stabilisation services less often and made greater use of outpatient services than patients receiving services through the community mental health system (figure). This pattern of service use indicates greater mental health stability among the self directed care group. These improvements do not come at the expense of greater costs. There is little evidence of deliberate fraud in any existing programme and only a few cases of participants failing to adequately understand the budgeting rules.12

Fig 1 Rates of service use among 131 participants in Florida self directed care programme and matched sample receiving care through standard channels, 2005-6

These findings are particularly noteworthy because the programmes serve a very low income and poorly educated population. This is exactly the population that many fear will be disadvantaged by an extension of individual budgets into the NHS. In order to make these programmes inclusive and effective, participants are provided with one to one support, often from a trained peer rather than from a professional as endorsed by the US Institute of Medicine.13 In this way, the model does not simply replicate the care management approach in which person centred planning of care comes to be dominated by professional decision making.

Scope for individualised funding in NHS

Individualised funding builds on existing attempts to increase patient engagement in health care such as the successful NHS expert patient programme. It recognises that patients develop expertise about their health and puts them in charge of deciding which strategies will work best to improve the care they receive. Without control of a budget, the ability to choose can often be meaningless because individual choices can be denied. Individualised funding also responds to recent reports indicating that existing services for those with long term conditions fail to adequately support individual preferences. For example, a 2005 report on self management of long term conditions found that some people would like to be more involved in managing their condition but that services could not accommodate these demands.14

Individual budgets would not be appropriate for all areas of the NHS. Emergency treatment is a prime example because needs are unpredictable and people do not want to make decisions about their care in an emergency situation. Inpatient care would also not be appropriate because, once in hospital, patients are dependent on the services provided within that institution.

By contrast, at the boundary between health and social care, patients are strongly in favour of including NHS resources within individual budgets and ending the arbitrary divide between health and social care. A study of people using direct payments found that participants were already unofficially using their direct payments to purchase a range of services that would be defined as health care, including physiotherapy, injections, foot care, and pain management. Their primary reasons for doing so were to overcome capacity constraints in the NHS and to integrate healthcare tasks better into their daily routine.15 Four criteria have been proposed to determine eligibility for individual budgets16:

Needs are reasonably stable and predictable

Individuals have unique knowledge about their needs and how they can best be met

Genuine alternatives exist for meeting their needs

Alternative sources of supply exist or can be developed outside of local authority or NHS services.

Within these general criteria, the scope for individual budgets could be broad. The approach has been proposed as a way of increasing choices for people receiving palliative care or NHS continuing care; to improve the integration of health and other supportive services for cancer patients; to raise the self management capacity of people with long term conditions such as diabetes and serious mental illness; and to increase choice for episodic care, such as maternity services or physiotherapy.17 18 19 In all cases, the decision to take up an individual budget would remain that of the patient. Traditional services would always be available for people who preferred to leave control in the hands of a professional.

How individual NHS budgets might work

Calculating budget

The size of the budget would be based on the patient’s diagnosis by a doctor

For a simple case, such as the need for physiotherapy, the value of the budget would be equivalent to the national tariff for the cost of a course of physiotherapy.

-

For more complex, long term conditions, the budget could be calculated in two ways:

The cost of a year of care for predictable needs, where this has been determined

The value of the traditional services that the patient would otherwise receive

The cost of emergency treatment resulting from complications would not be included

Monitoring health outcomes

Individuals would develop a spending plan to show how they intend to meet the health goals associated with their diagnosis—for example, maintaining a healthy blood pressure, quitting smoking, or losing weight

Doctors would monitor whether patients meet their goals rather than what they purchase to meet those goals—for example, if double glazing can bring about a sustained improvement in a patient’s asthma, it should be a permissible expense

Monitoring spending

The individual spending plan would be the primary vehicle for ensuring oversight over how public money is spent

Large deviations from the spending plan would trigger intervention from the primary care trust or other body

Electronic systems could streamline the oversight process.

Providing support services

-

Individuals would require access to support services to help them:

Identify their goals, make informed decisions about how best to meet them, and develop a spending plan

Deal with the financial and administrative transactions associated with the budget

A percentage of the funding currently used for care management could be used to cover the costs of support services.

Choice of provider has been a central part of much of the policy discussion in the UK and internationally in recent years. Giving patients greater choice over who provides their care goes some way to meeting the objectives set out in Our Health, Our Care, Our Say. But provider choice is only one dimension of health care. Individual budgets extend patient control over the who, what, when, and where, and, critically for long term conditions, give patients greater say over the types of treatments and services they receive. The time has come for governments to match their rhetorical commitment to a patient centred healthcare system that delivers high quality, integrated care for long term conditions to a real commitment to pilot individual budgets in health care.

Summary points

Individualised funding mechanisms in social care have been shown to improve satisfaction and outcomes at lower costs

Expanding individual budgets to NHS care would allow people to more accurately tailor care to their needs

Individual budgets for health care have been shown to work among US patients with serious mental illness

NHS pilots would signal real commitment to patient centred care

Contributors and sources: This article arose from research for a Harkness fellowship in healthcare policy supported by the Commonwealth Fund of New York City. The article does not reflect the views of the Commonwealth Fund or that of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Glasby J, Littlechild R. An overview of the implementation and development of direct payments. In: Leece J, Bornat J. Developments in direct payments Bristol: Policy Press, 2006

- 2.Leadbeater C, Bartlett J, Gallagher N. Making it personal. London: Demos, 2008.

- 3.Care Services Improvement Programme. Individual budgets pilot programme. individualbudgets.csip.org.uk/dynamic/dohpage5.jsp.

- 4.Poll C, Duffy S, Hatton C, Sanderson H, Routledge M. A report on In Control’s first phase 2003-5 London: In Control, 2006

- 5.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Choosing independence: an overview of the cash and counseling model of self-directed personal assistance services Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2006

- 6.National Centre for Independent Living. Clarifying the evidence on direct payments into practice London: NCIL, 2003

- 7.HM Government. Putting people first. London: Stationery Office, 2007:3-4.

- 8.Lipsey D. A sceptic’s perspective. In. Le Grand J. The other invisible hand Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007:182.

- 9.Alakeson V. The contribution of self-direction to improving the quality of mental health services Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2007

- 10.Florida Self-Directed Care. About FLSDC http://flsdc.org/about.htm

- 11.Florida Department of Children and Families, Mental Health Program Office. Report on the effectiveness of the self-directed care community mental health treatment program as required by s.394.9084 Tallahasse, FL: Department of Children and Families, 2007

- 12.Phillips B, Mahoney K, Schneider B, Simon-Rusinowitz L, Schore J, Barrett S, et al. Lessons from the implementation of cash and counseling: Arkansas, Florida, and New Jersey AcademyHealth annual research meeting, 2005. www.cashandcounseling.org/resources/20060106-123501/AcademyHealthJune26.ppt

- 13.Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions: quality chasm series Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2005

- 14.Corben S, Rosen R. Self-management for long-term conditions: patients’ perspectives on the way ahead London: King’s Fund, 2005

- 15.Glendinning C, Halliwell S, Jacobs S, Rummery K, Tyrer J. Bridging the gap: using direct payments to purchase integrated care. Health Soc Care Community 2000;8:192-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alakeson V. Putting patients in control. The case for extending self-direction into the NHS London: Social Market Foundation, 2007

- 17.Le Grand J. The other invisible hand Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007:130-49.

- 18.Rankin J. A good choice for mental health London: Institute for Public Policy Research; 2005.

- 19.Glasby J, Hasler F. A healthy option? Direct payments and the implications for healthcare Birmingham: Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham; 2004. www.hsmc.bham.ac.uk/news/JG-report.pdf