Abstract

Sensory gating refers to the preattentional filtering of irrelevant sensory stimuli. This process may be impaired in schizotypy, which is a trait also associated with cigarette smoking. This association may in part stem from the positive effects of smoking on sensory gating and attention. The relationship among sensory gating, smoking, schizotypy and attention was examined in 39 undergraduates. Sensory gating was indexed by the P50 suppression paradigm, and attention was measured by the Attention Network Test (ANT) and a Stroop task. Results showed sensory gating to be positively correlated with performances on ANT and Stroop reflected in better alerting, less conflict between stimuli, faster reaction time, and greater accuracy. Smokers showed a pattern of a greater number of significant correlations between sensory gating and attention in comparison to non-smokers, although the relationship between sensory gating and attention was not affected by schizotypy. The majority of significant correlations were found in the region surrounding Cz. These findings are discussed relative to the potential modifying influence of smoking and schizotypy on sensory gating and attention.

Keywords: Sensory Gating, ANT, Stroop, Alerting, Orienting, Conflict

1. Introduction

Sensory gating refers to the brain’s filtering of irrelevant sensory stimuli, thereby promoting optimal information processing (Braff and Geyer, 1990). As such, sensory gating is an important neurocognitive function. Sensory gating deficits can lead to sensory overload and cognitive fragmentation (Croft et al., 2001), which have been associated with behavioral disorders, psychotic symptoms, schizophrenia, and schizotypy (McGhie and Chapman, 1961; Freedman et al., 1983; Cadenhead et al., 2000).

Sensory gating is commonly indexed with event-related potentials. The most widely used method is the conditioning-testing P50 paradigm (Freedman et al., 1983). This procedure assesses cortical response suppression to a second (S2 or test) stimulus following an identical first (S1 or conditioning) stimulus, presented in pairs. Controls can typically reduce S2 amplitude by 80–90% relative to S1, but individuals with schizophrenia only reduce this amplitude by 10–20% (Freedman et al., 1983).

Cigarette smoking is strongly associated with schizophrenia and schizotypy (Adler et al., 1998; Kolliakou and Joseph, 2000; Dinn et al., 2004). The “self-medication” model suggests that schizophrenic or schizotypal individuals smoke to reduce negative symptoms and enhance cognitive function (Dalack et al., 1998; Taiminen et al., 1998; Lyon, 1999). This model has also been applied to the relationship between smoking and executive function deficits (Dinn et al., 2004). Smoking may also improve cognitive function and attentional performance in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Coger et al., 1996; Conners et al., 1996; Pomerleau et al., 1995).

Smoking may exert positive effects on attention by enhancing sensory gating. Superior sensory gating has been found in chronic smokers (Crawford et al., 2002; Croft et al., 2004). This relationship appears to interact in complex ways with schizotypy (Wan et al., 2006). In the latter study, non-smoking high schizotypy individuals exhibited poorer sensory gating than did non-smoking low schizotypy individuals. In contrast, high schizotypy smokers showed better sensory gating than did low schizotypy smokers. In the low schizotypy group, smokers showed poorer sensory gating than non-smokers, whereas smoking status had no effect in the high schizotypy group.

Posner and Petersen’s (1990) attention model provides a context for the role of sensory gating in attention. In this model, attention is divided into three processes: ‘alerting’, ‘orienting’, and ‘conflict’, each implemented by distinct functional brain networks. In alerting, the brain achieves and maintains an attentive state, which is associated with right frontal and parietal activity (Coull et al., 1996). During orienting, a cue is selected from sensory input that indicates which stimulus should be attended to (Posner, 1980), activating the frontal and superior parietal lobes (Corbetta et al, 2000). Finally, conflict among responses is resolved, a process associated with anterior cingulate and lateral prefrontal activation (Bush et al., 2000; MacDonald et al., 2000).

Sensory gating occurs at an early stage of information processing, but its effects may manifest across the attentional process. However, few studies have directly examined the relationship between sensory gating and attention, which is the aim of the present study. A positive association between sensory gating ability and attentional performance was predicted. Performance on the attention network test (ANT; Fan et al., 2002), a test specifically designed to assess the three components of Posner and Petersen’s (1990) attention model, as well as a Stroop task (Lezak, 1995), served as indices of attention. Because of the inverse relationship between P50 sensory gating values and sensory gating ability, positive correlations indicate that the attention measure has a negative association with sensory gating, and negative correlations indicate the opposite. Hence, for both ANT and Stroop tasks, P50 sensory gating values were predicted to have (1) negative correlations with alerting, accuracy, and orienting effects, and (2) positive correlations with conflict effects and reaction time. Moreover, the effects of smoking and schizotypy on sensory gating and attention, which have shown mixed effects in previous research, were also appraised. Correlations among variables reflecting these constructs were calculated to explore the complexities of these interactions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Thirty-nine right-handed undergraduates were selected (age: M = 18.87 years; SD= 1.01; range = 17 – 21 years) from an online survey that included the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ; Raine, 1991), and smoking history and medical background questionnaires. Participants reported normal hearing and no history of neurological or psychiatric problems, and stated that they ingested no prescription or over-the-counter drugs (except for contraceptives), alcohol or illicit drugs for at least one day before the experiment.

The distribution of SPQ total scores for 613 online volunteers was normal, with mean value 20.56, SD 12.31, range from 0 to 58, and Skewness value was 0.52. The upper 10% of SPQ distributions is typically used as the cutoff for schizotypy. The 10% high-low cut-offs on the total SPQ score were 42 and 8 respectively in Raine’s study (1991), and 39 and 10 for English undergraduate in Hall and Habbits’ study (1996). The present study had 38 and 5 respectively as 10% high-low cut-offs. Among 613 online participants, 34 participants (20 men and 14 women) met Raine’s high cut-off criteria, 55 (28 men and 27 women) met Hall and Habbits’ high cut-off criteria, and 64 (31 men and 33 women) met our 10% high cut-off criteria. However, in these 64 participants, only 16 smokers were found and some of them had to be excluded because of medical or mental problems. Thus, the 1/3 high-low cut-offs were used in order to include more healthy smokers, with high-low cut-offs 25 and 13 respectively. There were 19 low schizotypy participants (SPQ: M = 3.53, SD = 3.08) and 20 high schizotypy participants (SPQ: M = 40.05, SD = 9.47). In the low schizotypy group, there were 9 smokers (4 women and 5 men) and 10 non-smokers (7 women and 3 men); in the high schizotypy group, there were 10 smokers (4 women and 6 men) and 10 non-smokers (6 women and 4 men).

Gender may interact with both smoking and schizotypy, and studies of schizophrenia clearly suggest gender differences in both symptomatology and prognosis (Miller et al., 1995). T-tests were conducted between men and women among smokers to assess the possible impact of these factors. No significant gender differences were found for exhaled carbon monoxide (CO; ppm) levels for both conditions, number of cigarettes per day, smoking time (years), SPQ scores, and scores on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (Fagerström, 1987) (see Table 1). Additionally, higher levels of nicotine consumption among schizotypy have been reported (Williams et al., 1996; Kolliakou et al., 2000), so smokers in the high and low schizotypy groups may have differed in smoking levels. Consequently, the differential effects of a four hour withdrawal and reintroduction of nicotine (see procedure) on schizotypal level might have been confounded with greater physiological disruption in the high schizotypy group. To examine this possibility, T-tests were conducted between high and low schizotypy groups among smokers. No significant differences were found between the two groups on CO levels for both conditions, number of cigarettes per day, and smoking time (years), There was a trend for the high schizotypy group to show higher Fagerström scores (p = 0.052). Therefore, overall, men and women smokers, and high and low schizotypy smokers appeared to have similar smoking characteristics in this study.

Table 1.

The influence of schizotypy level and gender on smoking variables among smokers

| High Schizotypy | Low Schizotypy | t (17) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO for Condition 1 | 3.00 | 2.88 | 0.10 | 0.92 |

| CO for Condition 2 | 9.40 | 9.25 | 0.06 | 0.95 |

| Cigarettes per Day | 6.15 | 1.72 | 1.71 | 0.11 |

| Smoking Time (years) | 2.85 | 1.94 | 1.20 | 0.25 |

| Fagerström Score | 1.80 | 0.33 | 2.09 | 0.05 |

|

| ||||

| Men | Women | t (17) | p | |

|

| ||||

| CO for Condition 1 | 3.00 | 2.85 | 0.12 | 0.91 |

| CO for Condition 2 | 9.73 | 8.71 | 0.40 | 0.69 |

| Cigarettes per Day | 2.64 | 6.00 | −1.24 | 0.23 |

| Smoking Time (years) | 1.95 | 3.06 | −1.48 | 0.16 |

| Fagerström Score | 0.64 | 1.75 | −1.49 | 0.16 |

2.2. Procedure

Virginia Tech’s Institutional Review Board approved the experiment and each participant gave informed consent. The CO test (see below) and a medical questionnaire were administered to verify that smoking criteria were met. The Fagerström Test (Fagerström, 1987) was given at the beginning of the experiment. Smokers abstained at least four hours before the experiment. In condition 1, smokers were tested while abstaining. After that, smokers smoked their usual brand of cigarette and within 3–5 minutes, condition 2 was performed. Smokers had their EEG recorded in the P50 paradigm. Non-smokers were tested in the same two conditions but without smoking. EEG acquisition required about 20 minutes.

Exhaled CO level was assessed twice with a Vitalograph Breath CO monitoring device (Vitalograph Inc, Lenexa, KS): before condition 1 and immediately after smoking before condition 2 EEG recording. All abstainers had a CO level below 10 before condition 1. As expected, smokers increased their CO level significantly from condition 1 to 2, t (17) = 7.21, p < .001 (Condition 1: M = 2.94, SD = 2.46; Condition 2: M = 9.33, SD = 5.05), whereas non-smokers did not (Condition 1: M = 1.40, SD = 0.60; Condition 2: M = 1.50, SD = 0.61), F (1, 34) = 51.87, p < .001.

2.3. EEG Data Collection

Forty identical pairs of 1 ms 1000 Hz sinusoidal tone pips (1ms rise/fall; 70dB), with a 512 ms inter-click interval and 10000 ms inter-pair interval, were delivered by the Neuroscan® stimulus generation system through speakers placed 35 cm from each ear. Participants were instructed to attend to a stationary cross on a computer monitor at eye level, 80 cm in front of them.

Continuous EEG (0.1 to 100 Hz, 500 Hz sampling rate; gain of 150) was recorded with an Electrocap® at 30 electrode sites (impedance < 5 kΩ), referenced to the nose, plus vertical (above and below left eye) and horizontal EOG electrodes. Recording, digitization, and processing were done with Neuroscan® SynAmps amplifier and Scan® version 4.2. Continuous EEG was epoched offline from −50 ms to 462 ms. Epochs were detrended and baselined to the pre-stimulus 50 ms period. To eliminate gross eye movement, muscle and movement artifact, epochs were submitted to semi-automatic artifact rejection ( ± 50 μV) for eye channels, FP1, FP2, F3 and F4. Artifact rejections were then visually confirmed and verified by two independent experimenters. The numbers of trials retained for each participant differed as a function of the artifact rejection protocol. Generally 60% to 100% of trials (24 to 40 trails) were kept per participant for further analysis. There were no significant differences in the number of rejected trials across the groups, and no participants had fewer than 24 trials. ERP data from participants who had small numbers of ERP trails (24–30) were reprocessed. Eye blink ERPs for those participants were averaged and transferred to a spatial singular value decomposition (SVD) file. The SVD file was then subtracted from the filtered continuous EEG. This process removed the effects of eye blinks on ERPs while simultaneously retaining a high number of trails. ERP waveforms generated before and after reprocessing were compared, and waveforms that showed greater consistency for all selected trials were used in subsequent analyses.

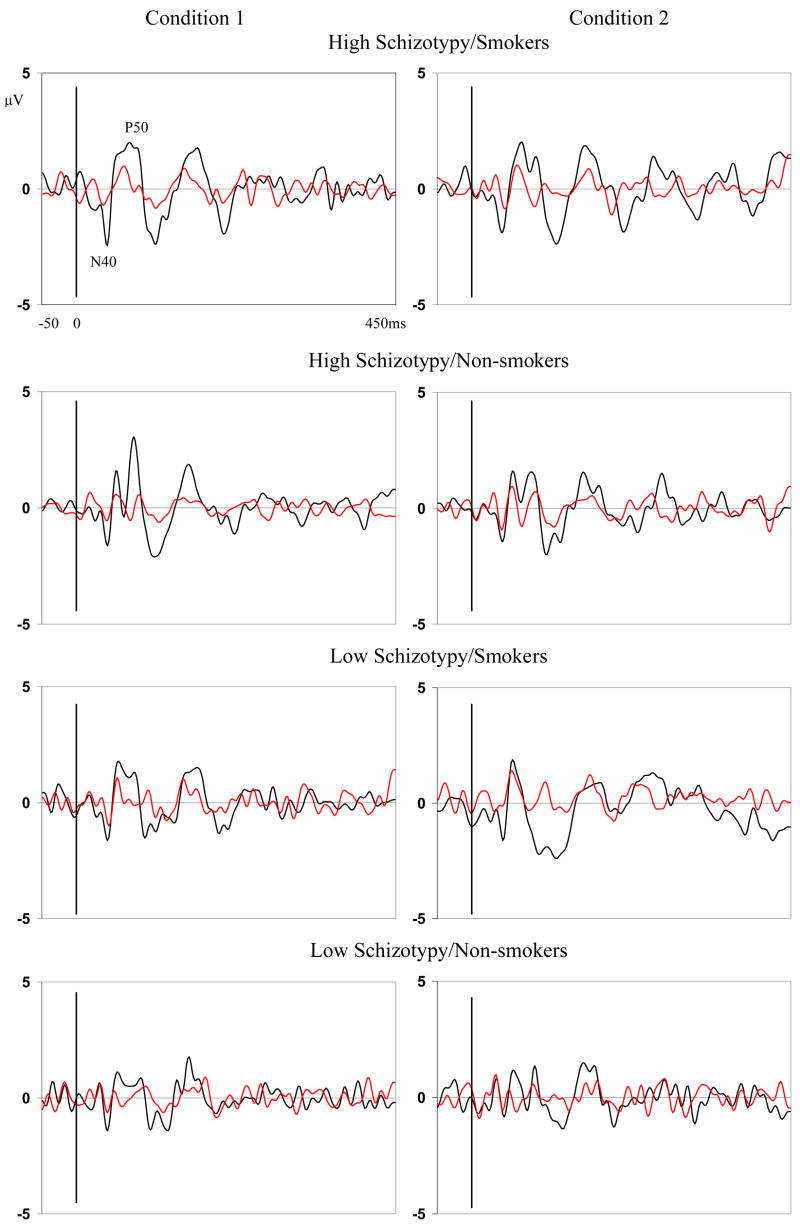

To better image early components, a two-pole Butterworth digital filter (band-pass 10–70 Hz, 24 dB per octave roll-off) was applied to the averaged EPs, which were exported and analyzed off-line with Brain Vision Analyzer®. A semi-automatic program identified the N40 (30–60 ms) and P50 (45–75 ms) peak amplitudes and latencies for the following regions: frontal (F3, Fz, F4), fronto-central (FC3, FCz, FC4), central (C3, Cz, C4), centro-parietal (CP3, CPz, CP4), and parietal (P3, Pz, P4). Peaks were verified by two experimenters separately and adjusted when necessary. Experimenters were blind to participant’s schizotypy and smoking status. As shown in Figure 1, separate averaged evoked potentials (EPs) were generated for click 1 and 2 (S1 and S2) for both conditions (condition 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Grand Averaged Evoked Potentials on C3 for Four Groups under Two Conditions (Black line is the response to S1; red line is the response to S2)

2.4. Attention Tests

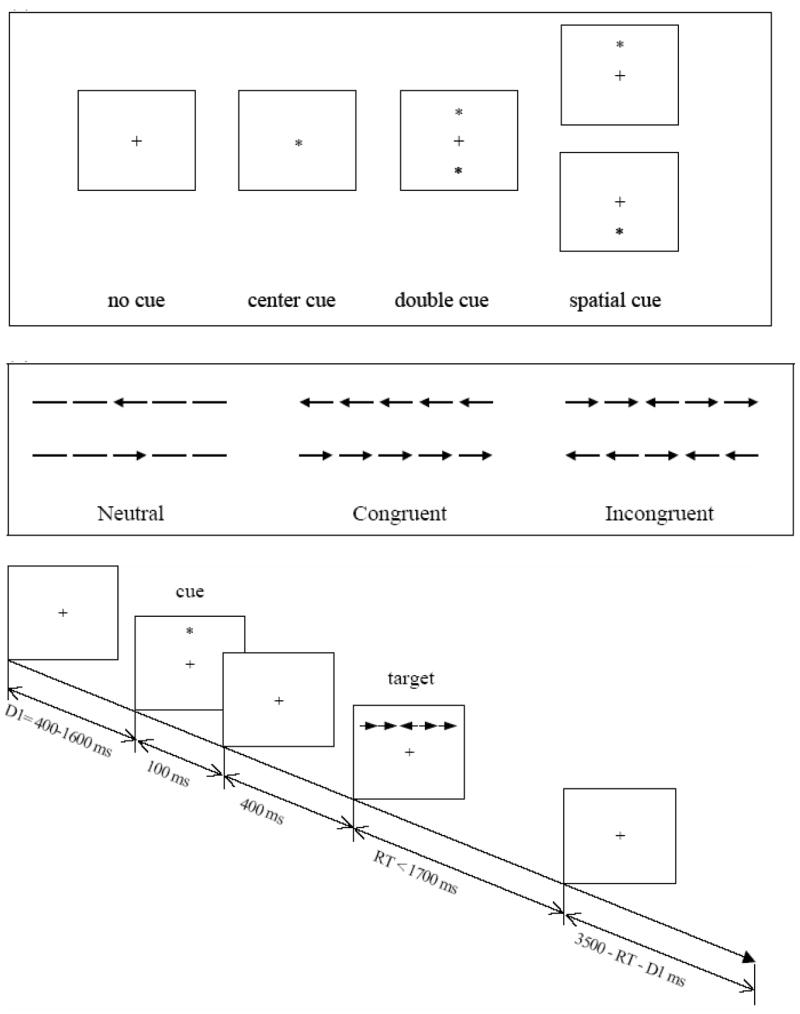

The ANT and Stroop tasks were completed after EEG acquisition. In the ANT, there were four cue conditions (see Figure 2): no cue, center cue (a little star was in the middle of the screen), double cue (two little stars were shown above and below the middle point of the screen), and spatial cue (one little star was shown above or below the middle point of the screen). Stimuli (an array of five arrows) were presented after each cue. Participants were asked to identify the direction (left or right) of the middle arrow of each stimulus by clicking the left or right keyboard key with the respective index finger. The reaction time (RT, in ms) of each trial was recorded by computer. The alerting effect was calculated by subtracting the mean RTs of the spatial cue conditions from the no cue conditions. The orienting effect was calculated by subtracting the mean RTs of the spatial cue from the central cue conditions. To measure conflict, the target arrow was presented with four same direction arrows (congruent flanker condition) or four different direction arrows (incongruent flanker condition). The conflict effect was calculated by subtracting the mean RTs of the congruent conditions from the incongruent conditions. Alerting, orienting and conflict effects, mean RTs, and accuracy were automatically displayed after task completion. A test session consisted of a 24-trial full-feedback practice block and three experimental blocks of trials with no feedback. Each experimental block consisted of 96 trials (4 cue conditions × 2 target locations × 2 target directions × 3 flanker conditions × 2 repetitions). Trial presentation was in random order. The total time for the test was about 30 minutes.

Figure 2.

Attention Network Test (Fan et al., 2002)

The Stroop task was used to measure the ability to focus attention and reduce conflict. The task requires resolution of the conflict between a word name and its ink color (MacLeod, 1991); performance depends on ignoring irrelevant information (Xu and Domino, 2000). Participants were asked to identify the color of the displayed symbol or word by clicking the corresponding key (z for red, x for green, blue for yellow) with the right and left index fingers. The first task section consisted of 60 trials of colorful symbols, such as ‘XXXX’. The second section included 80 trials of incongruent information of 12 types: the word ‘red’ written in three colors except red, the word ‘green’ written in three colors except green, and so on. In the third section, 80 trials of congruent information were presented, of four types: the word ‘blue’ written in blue, the word ‘yellow’ written in yellow, and so on. The total time for task completion was about 30 minutes. The mean and SD of RT and the number of correct trials per section were displayed after task completion.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Of all sites, Cz showed the greatest sensory gating, and only fronto-central and central lateral sites (FC3, FC4, C3, and C4) showed the interaction of schizotypal and smoking on sensory gating. For this reason, correlational analyses were limited to nine sites circling Cz: FC3, FCz, FC4, C3, Cz, C4, CP3, CPz, and CP4. Sensory gating was defined as the ratio of N40 – P50 of S2 and S1. The distribution of the data indicated that a non-parametric statistic would be most appropriate. Therefore, Spearman’s measure of association was calculated to assess the relationship at each site between sensory gating and each attention component, by condition. Two-tailed tests were conducted to determine the significance level of the correlations at each site.

3. Results

3.1. Group Comparisons

The previous analyses for group comparisons (smokers and non-smokers; high and low schizotypal groups) on P50 gating ratio and attentional performance were reported in Wan et al., (2005, 2006). P50 sensory gating was observed to be greater at midline than left/right hemispheric sites, and fronto-central and central sites. The interaction of schizotypal and smoking on sensory gating was observed only at fronto-central/central lateral sites (FC3, FC4, C3, and C4). At fronto-central/central lateral sites, the following effects were observed: (1) among non-smokers, better sensory gating occurred in the low than high schizotypy group; (2) among smokers, better sensory gating occurred in the high than low schizotypy group, and (3) among the low schizotypy group, smokers showed less sensory gating than non-smokers (Wan et al., 2006). No significant schizotypy effect, smoking effect and schizotypy and smoking interaction on ANT and Stroop components was found (Wan et al., 2005).

The present analyses found that no significant difference on P50 amplitudes and latencies existed between smokers and non-smokers or between high and low schizotypal groups. P50 amplitudes and latencies of condition 1 and 2 and of click 1 and 2 are shown in Table 2 for each group, as well as P50 gating ration of condition 1 and 2.

Table 2.

P50 amplitudes, P50 latencies, and gating ratios on Cz for condition 1 and 2 (Mean ± SD)

| Smoker | Non-smoker | High Schizotypy | Low Schizotypy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = | 19 | 20 | 19 | 20 |

| P50 Amplitude (μV): | ||||

| Condition 1 Click 1 | 4.16 ± 2.95 | 4.28 ± 2.69 | 4.40 ± 2.41 | 4.05 ± 3.16 |

| Condition 1 Click 2 | 1.85 ± 1.81 | 1.74 ± 0.85 | 1.81 ± 0.87 | 1.77 ± 1.76 |

| Condition 2 Click 1 | 4.02 ± 1.91 | 4.05 ± 2.35 | 4.28 ± 2.09 | 3.78 ± 2.17 |

| Condition 2 Click 2 | 2.02 ± 1.53 | 1.81 ± 1.50 | 1.93 ± 1.30 | 1.89 ± 1.72 |

| P50 Latency (ms): | ||||

| Condition 1 Click 1 | 63.16 ± 9.67 | 61.90 ± 6.44 | 63.60 ± 8.07 | 61.37 ± 8.17 |

| Condition 1 Click 2 | 62.32 ± 7.00 | 60.00 ± 6.84 | 61.90 ± 7.38 | 60.32 ± 6.51 |

| Condition 2 Click 1 | 62.63 ± 7.97 | 63.40 ± 6.96 | 65.20 ± 7.85 | 60.74 ± 6.26 |

| Condition 2 Click 2 | 63.79 ± 7.21 | 61.40 ± 6.29 | 63.00 ± 6.21 | 62.11 ± 7.47 |

| P50 Gating Ratio (%): | ||||

| Condition 1 | 0.50 ± 0.33 | 0.49 ± 0.27 | 0.43 ± 0.18 | 0.55 ± 0.37 |

| Condition 2 | 0.59 ± 0.27 | 0.53 ± 0.27 | 0.55 ± 0.28 | 0.57 ± 0.29 |

3.2. Correlational Analyses

Outliers for the P50 gating ratio and each component of ANT and Stroop were excluded by means of an iterative algorithmic process for the detection and removal of outliers (Arsham, n.d.). Gating ratios greater than 1.2 were excluded, as were ANT conflict scores greater than 220 ms, ANT mean RTs greater than 725 ms, ANT accuracies less than 0.81, STOOP conflict scores greater than 300, and Stroop mean RT greater than 825 ms. Performance of each group on ANT and Stroop are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Performances on ANT and Stroop of each group (Mean ± SD)

| Smoker | Non-smoker | High Schizotypy | Low Schizotypy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = | 19 | 20 | 19 | 20 |

| ANT: | ||||

| Alerting (ms) | 30.78 ± 20.16 | 25.50 ± 20.14 | 30.26 ± 20.15 | 25.74 ± 20.25 |

| Orienting (ms) | 35.50 ± 19.63 | 40.50 ± 22.75 | 34.16 ± 19.00 | 42.11 ± 23.00 |

| Conflict (ms) | 133.67 ± 51.40 | 132.85 ± 45.38 | 124.37 ± 34.59 | 142.11 ± 57.50 |

| Mean RT (ms) | 539.06 ± 58.96 | 559.50 ± 67.95 | 530.79 ± 51.24 | 568.84 ± 70.61 |

| Accuracy (%) | 94.32 ± 7.85 | 97.70 ± 2.16 | 95.30 ± 7.57 | 96.84 ± 3.30 |

| Stroop: | ||||

| Conflict (ms) | 73.90 ± 58.66 | 111.39 ± 106.92 | 85.60 ± 101.58 | 101.05 ± 72.51 |

| Mean RT (ms) | 671.66 ± 86.63 | 670.94 ± 72.70 | 661.71 ± 82.40 | 681.38 ± 75.55 |

| Accuracy (%) | 83.33 ± 4.00 | 84.25 ± 3.55 | 83.29 ± 3.58 | 84.34 ± 3.95 |

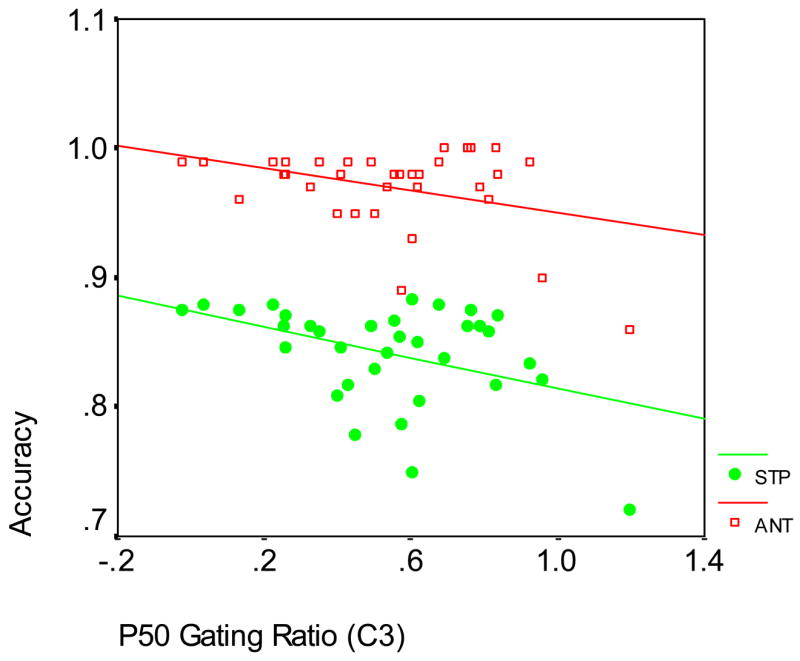

Correlations were initially performed among all participants (n = 39). Significant correlations are shown in Table 4; two sample scatterplots are shown in Figure 3. For example, P50 gating ratio (on CP3 and CP4 in condition 1) was positively correlated with the ANT conflict effect, and P50 gating ratio (on C3 in condition 1) was negatively correlated with ANT accuracy and Stroop accuracy.

Table 4.

Significant correlations between P50 gating ratio and performances on ANT and Stroop (STP) among all participants (r/p/n; α = 0.05)

| Condition 1 | Condition 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| ANT alerting | CPz −.354/.047/32 | |

| ANT conflict | CP3 .355/.039/34 | |

| CP4 .372/.030/34 | CP4 .450/.011/31 | |

| ANT accuracy | C3 −.364/.034/34 | |

| STP accuracy | C3 −.406/.015/35 |

r = correlation coefficient

p < 0.05 is considered as significant

n = the number of participants

Figure 3.

Correlations between P50 Gating Ratio and ANT Accuracy and Stroop Accuracy among all Participants at C3, condition 1 (ANT: r = −.364; p = .034; n = 34; Stroop: r = −.406; p = .015; n = 35)

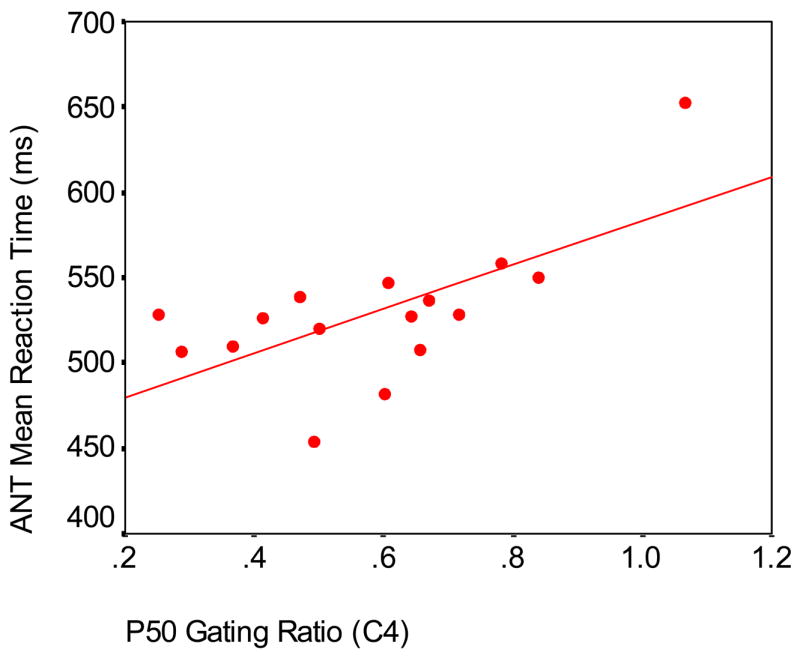

Since group differences on P50 gating ratio were shown at fronto-central and central lateral sites in the previous study (Wan et al., 2006), correlation analyses were then conducted among smokers, non-smokers, and low and high schizotypy groups separately. Significant correlations for each group are shown in Tables 5 and 6; a sample scatterplot is shown in Figure 4.

Table 5.

Significant correlations between P50 gating ratio and performances on ANT and Stroop (STP) among smokers and non-smokers (r/p/n; α = 0.05)

| Smokers | Non-smokers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition 1 (nicotine withdrawn) | Condition 2 (following smoking) | Condition 1 | Condition 2 | |

| ANT orienting | CP4 −.650/.012/14 | FC3 .588/.027/14 | ||

| FC4 .516/.049/15 | ||||

| C4 .541/.031/16 | ||||

| ANT conflict | FCz .515/.034/17 | C4 .662/.005/16 | ||

| CP4 .633/.008/16 | ||||

| ANT mean RT | C4 .655/.006/16 | CPz .545/.029/16 | ||

| ANT accuracy | C3 −.629/.012/15 | |||

| STP conflict | C3 .543/.045/14 | |||

| CP3 .572/.032/14 | ||||

| STP accuracy | C3 −.568/.022/16 | CP4 −.706/.002/16 | ||

r = correlation coefficient

p < 0.05 is considered as significant

n = the number of participants

Table 6.

Correlations between P50 gating ratio and performances on ANT and Stroop (STP) among high schizotypy group and low schizotypy group (r/p/n; α = 0.05)

| High Schizotypy | Low Schizotypy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition 1 (nicotine withdrawn) | Condition 2 (following smoking) | Condition 1 (nicotine withdrawn) | Condition 2 (following smoking) | |

| ANT alerting | Cz −.541/.020/18 | |||

| ANT orienting | CPz −.601/.011/17 | |||

| CP4 −.528/.029/17 | ||||

| ANT conflict | C4 .490/.033/19 | C3 .569/.027/15 | ||

| CP3 .536/.032/16 | ||||

| ANT accuracy | FC4 −.563/.045/13 | |||

| STP conflict | FC3 .518/.040/16 | C4 .618/.024/13 | ||

| STP mean RT | Cz −.498/.030/19 | CP4 .778/.000/16 | ||

| STP accuracy | C3 −.575/.020/16 | CP4 −.529/.029/17 | ||

r = correlation coefficient

p < 0.05 is considered as significant

n = the number of participants

Figure 4.

Correlation between P50 Gating Ratio and ANT Mean Reaction Time among Smokers at C4, condition 1 (r = .655; p = .006; n = 16)

Smokers had a larger number of relationships than non-smokers. As shown in Table 5, among smokers, P50 gating ratio positively correlated with ANT conflict, ANT mean RT, and Stroop conflict, and negatively correlated with ANT accuracy and Stroop accuracy. Interestingly, P50 gating ratio in condition 1 correlated negatively with ANT orienting, but this relationship was positive for condition 2. In addition, more sites showed significant relationships in condition 2 (following smoking) than in condition 1 (before smoking). Among non-smokers, P50 gating ratio only positively correlated with ANT conflict.

A greater number of significant relationships were found in the high schizotypy group than in the low schizotypy group (Table 6). In the high schizotypy group, P50 gating ratio positively correlated with ANT conflict and Stroop conflict, and negatively correlated with ANT alerting, ANT orienting, ANT accuracy and Stroop mean RT. Among the low schizotypy group, P50 gating ratio showed a positive relationship with ANT conflict and Stroop mean RT, and a negative relationship with Stroop accuracy. P50 gating ratio in condition 2 was negatively associated with Stroop mean RT in the high schizotypy group, but this relationship was positive in low schizotypy group.

4. Discussion

4.1. P50 Sensory Gating and Attention

Sensory gating, as assessed by P50 suppression, showed a moderate relationship to ANT performance and a weak relationship with Stroop performance across all participants (Table 4). These relationships were restricted to sites in the centro-parietal region; no significant correlations were observed in the fronto-central region. Four of the six centro-parietal sites used in the analyses yielded significant correlations between sensory gating and ANT performance with an average magnitude of r = 0.37. In contrast, only one significant correlation between Stroop scores and sensory gating values was obtained. The significant associations that were observed are consistent with the hypothesized positive relationship between P50 sensory gating and attentional performance. Examination of individual tasks components reveals that (a) ANT alerting and accuracy showed negative associations with sensory gating, (b) ANT conflict had a positive relationship with sensory gating, and (c) Stroop accuracy showed a negative correlation with sensory gating. Because low sensory gating values represent better sensory gating ability, positive correlations indicate that the attention measure has a negative association with sensory gating, and negative correlations indicate the opposite relationship. Hence, the data generally suggest that sensory gating ability is positively associated with attentional vigilance and precision, and the capacity to resolve attentional conflict.

Sensory gating is considered to reflect an automatic, preattentive component of information processing, in contrast to later, more controlled aspects of auditory attention (Jerger et al., 1992). ERP waveforms between 20 and 50 ms after auditory stimulus onset are distinct from subsequent waveforms observed during selective auditory attention, a phenomenon known as the ‘P20–50 attention effect’ (Woldorff and Hillyard, 1991). It takes auditory inputs about 20 ms to reach the human cortex, and the P20–50 effect is attributed to preliminary modulation of attention prior to more thorough perceptual analysis (Gazzaniga et al., 2002). In support of this model, instructions to attend to either the intensity or number of auditory stimuli have been shown to affect N100 amplitude and RT to S2, but not P50 suppression (White and Yee, 1997). The present findings highlight the important role of sensory gating on early information processing of auditory attention. Sensory gating was positively associated with performance on both the ANT and Stroop tasks. Moreover, a cross-modality effect was demonstrated in that P50 suppression was positively associated with visual attention performance on these tasks.

4.2. Modification by Smoking Status and Schizotypy

In general, the trends described above regarding sensory and attentional performance were replicated when assessed separately in smokers and non-smokers (Table 5). However, over three times as many significant correlations between sensory gating and attention were observed in the smokers than in the non-smokers. Additionally, both the magnitude of the correlations and the number of attention components showing significant associations increased when calculated separately by smoking status. Significant relationships between sensory gating and ANT orienting and RT, and Stroop conflict were found in the smoking group, but not in the non-smokers or in the analyses that included all participants. One possible interpretation of these findings is that chronic smoking enhances the relationship between sensory gating and attention. This notion is consistent with reports that smoking and nicotine improve attention and cognitive function in ADHD (Pomerleau et al., 1995; Coger et al., 1996; Conners et al., 1996). Chronic smoking can also enhance sensory gating, although acute effects have been less consistent (Crawford et al., 2002; Croft et al., 2004). This may explain why, consistent with predictions, ANT orienting was negatively correlated with sensory gating before smoking, but this relationship was reversed after smoking. Acute smoking may have enhanced ANT orienting to a greater degree than it did sensory gating, and so the direction of the relationship was reversed in the post-smoking condition. However, when the data are split by smokers and nonsmokers (Table 5), there are actually a greater number of significant correlations, albeit at different sites, in the post-smoking condition.

On the whole, both low and high schizotypy groups produced correlations consistent with the notion that sensory gating/P50 suppression is positively associated with attentional performance on the ANT and Stroop tasks (Table 6). However, unlike the smoking comparison, no clear differences in the pattern of correlations emerged based on schizotypy status. Schizotypy has been associated with poor sensory gating (Cadenhead et al., 2000). An anomalous negative association was observed between sensory gating and Stroop RT in the high schizotypy group in condition 2. The schizotypy groups had nearly identical distributions of smokers and non-smokers, but among smokers, high schizotypy individuals had higher Fagerström scores than low schizotypy individuals (Table 1). Again, the effects of acute smoking may have differentially affected sensory gating and RT, distorting the nature of their relationship. It is notable that it was only in the post-smoking condition that associations inconsistent with the predicted relationship between sensory gating and attention were observed, highlighting the important distinction between the acute and chronic effects of nicotine on sensory gating and attention. It also appears that chronic smoking exerted a greater mediating effect on the sensory gating-attention relationship than schizotypy status did. Although 70% of the high schizotypy sample met standard criteria for this designation, the correlations based on schizotypy may have been attenuated by the 30% that did not meet these criteria. In contrast, smoking status may have been more precisely assessed with the measures used in this study.

4.3. Limitations and Future work

One possible limitation in the current work is the lower cut-off (1/3) on SPQ total score for schizotypy, which may have led to spurious results. Some researchers argued that the lower cut-off may lead to inclusion of participants high in social anxiety but low in perceptual anomalies who maybe not true schizotypy (e.g., Claridge et al., 1996; Bergman et al., 1996). Moreover, anxiety may influence P50 suppression (e.g., Johnson and Adler, 1993; White and Yee, 1997). To test whether our high schizotypy group included some participants high in social anxiety but low in perceptual anomalies, we did an additional analysis on SPQ scores. In the high schizotypy group, 14 participants (70%; 5 men and 9 women) met the more stringent 10% cutpoint criteria (SPQ total score ≥ 38), 6 participants (30%; 4 men and 2 women) fall into the upper 1/3 to upper 10% SPQ total score distribution (SPQ total score from 25 to 37). Among all of them, SPQ social anxiety score was positively correlated with SPQ cognitive-perceptual score, SPQ interpersonal score, SPQ disorganized score, and SPQ total score (all ps < 0.05). Among the 14 participants in the upper 10%, SPQ social anxiety ranged from 3 to 8 and SPQ cognitive-perceptual score ranged from 11 to 25; among the 6 participants in the upper 1/3 to 10% range, SPQ social anxiety ranged from 1 to 6 and SPQ cognitive-perceptual score ranged from 4 to 20. In fact, only one participant had a relatively high society anxiety score (6) and low cognitive-perceptual score (4) in the study. Exclusion of this participant does not change the results on sensory gating and attention. Nonetheless, this issue should be considered in future work, possibly with an anxiety scale for screening schizotypal participants.

Conditions 1 and 2 tended to show different patterns of correlations that varied by group. In condition 1, smokers abstained for at least four hours; in condition 2, ERPs were acquired immediately after smoking, but ANT was conducted between 20 and 50, and the Stroop between 50 and 80 minutes after smoking. Hence, acute smoking effects may have been differentially manifested in sensory gating values and attentional performance, possibly accounting for inconsistencies between conditions 1 and 2. Moreover, counterbalancing the conditions was not feasible, so fatigue or practice effects in the second condition cannot be ruled out. Future research is needed to assess the relative contributions of fatigue and smoking in P50 suppression paradigms involving attention, particularly when comparing groups that differ on schizotypy.

Another problem is that both smoking and non-smoking groups included high and low schizotypy individuals, and likewise, groups divided by schizotypy scores had both smokers and non-smokers. Furthermore, all groups included both genders. Although analyses described above indicated that these variables were evenly distributed, subdividing the smoking and schizotypy groups by other variables led to small subject subsets, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn from these comparisons. Future research could focus on either smoking or schizotypy, and control the other factor, or include large enough samples so that both factors could be examined simultaneously.

Although there was no significant differences on CO levels for both conditions, number of cigarettes per day, smoking time (years), and Fegarström scores between low and high schizotypy smokers, nicotine withdrawal may interact with level of schizotypy symptoms as a third variable. Relationships between attention and P50 gating in the high schizotypy group may have been affected by the degree of nicotine withdrawal. The high schizotypy smokers reported smoking 6.15 cigarettes per day, which is an average of one cigarette about every two to three waking hours. In contrast, the low schizotypy smokers smoked only 1.75 cigarettes per day, or about one every nine hours. Since all smokers abstained from smoking for four hours before ERP data collection, high but not low schizotypy smokers may have been in a state of nicotine withdrawal when tested. As such, the stress levels resulting from nicotine withdrawal may not have been constant for high and low schizotypy smokers. Because stress has been shown to impair P50 suppression and may influence attention (White and Yee, 1997), future researchers should assess the stress level of abstained smokers before the P50 test. This confound appears to be inherent in studies that compare different levels of smokers and require a period of abstinence as part of the experimental protocol. Although it may be better to match the smoking status for low and high schizotypy smokers, from 613 online participants, we only identified nine low schizotypy smokers. Hence, although this group is of intrinsic scientific interest, their low numbers is a recruiting obstacle that should be anticipated in future research.

Another potential limitation concerns the impact of groups with a reduced range of P50 ratios (i.e., low schizotypals and non-smokers). This reduction in range may have attenuated associations between the ERP and attentional measures in such instances. Future work should include large enough samples to insure larger ranges of ERP indices.

The relationship between sensory gating and attention was found to vary by EEG site. Specifically, central lateral sites showed the most consistent relationships between sensory gating and attention. P50 source localization studies have yielded mixed results, with various reports placing the origin of the P50 in the auditory cortex (Wood and Wolpaw, 1982; Weisser et al., 2001), hippocampus (Goff et al., 1980), reticular structures (Erwin and Buchwald, 1986), and frontal cortex (Weisser et al., 2001). Magnetoencephalographic data showed that the M50, the magnetic analog of the P50, was localized in the superior temporal gyri (Edgar et al., 2003). Sensory gating may be a multi-step process, with an early phase subserved by the temporo-parietal and prefrontal cortices and a later phase mediated by the hippocampus (Grunwald et al., 2003). The present data also point toward a role for the midline region in sensory gating, with P50 suppression at CP4, C3, and C4 showing the largest overall number of significant correlations with attentional measures. However, observed associations tended not to be consistent by site across conditions, even within groups. Future work related to P50 source localization will help identify the brain mechanisms involved in sensory gating, as well as clarify the role of sensory gating in attention. Additionally, inclusion of N100 data may help illuminate how these sensory ERP waveforms contribute to the early stages of attention.

Acknowledgments

Financial support came from Virginia Tech and from the Virginia Youth Tobacco Project Coalition. This work also partially supported by NIH grant #ROI MH58784 (NNB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler LE, Olincy A, Waldo M, Harris JG, Griffith J, Stevens K, Flack K, Nagamoto H, Bickford P, Leonard S, Freedman R. Schizophrenia, sensory gating, and nicotinic receptors. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:189–202. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsham H. Determination of the outliers. nd Retreived on 6/27/07 from the University of Baltimore Web site: http://home.ubalt.edu/ntsbarsh/Business-stat/otherapplets/Outlier.htm.

- Bergman AJ, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, Aronson A, Marder D, Silverman J, Trestman R, Siever LJ. The factor structure of schizotypal symptoms in a clinical population. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:501–509. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.3.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Geyer MA. Sensorimotor gating and schizophrenia: Human and animal model studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;49:206–215. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810140081011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI. Cognitive and emotional influences in the anterior cingulated cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;4:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenhead KS, Light GA, Geyer MA, Braff DL. Sensory gating deficits assessed by the P50 event-related potential in subjects with schizotypal personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:55–59. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claridge C, McCreery C, Mason O, Bentall R, Boyle G, Slade P, Popplewell D. The factor structure of schizotypal traits: A large replication study. Br J Clin Psychol. 1996;35:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1996.tb01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coger RW, Moe KL, Serafetinides EA. Attention deficit disorder in adults and nicotine dependence: Psychobiological factors in resistance to recovery. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1996;28:229–240. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1996.10472484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Levin ED, Sparrow E, Hinton SC, Erhardt D, Meck WH, Rose E, March J. Nicotine and attention in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996;32:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Kincade JM, Ollinger JM, McAvoy MP, Shulman G. Voluntary orienting is dissociated from target detection in human posterior parietal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:292–297. doi: 10.1038/73009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull JT, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ, Grasby PM. A fronto-parietal network for rapid visual information processing: A PET study of sustained attention and working memory. Neuropsychologia. 1996;34:1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(96)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford HJ, Mcclain-Furmanski D, Castagnoli N, Castagnoli K. Enhancement of auditory sensory gating and stimulus-bound 40 Hz oscillations in heavy tobacco smokers. Neurosci Lett. 2002;317:151–155. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft RJ, Lee A, Bertolot J, Gruzelier JH. Associations of P50 suppression and desensitization with perceptual and cognitive features of “unreality” in schizotypy. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:441–446. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft RJ, Dimoska A, Gonsalvez CJ, Clarke AR. Suppression of P50 evoked potential component, schizotypal beliefs and smoking. Psychiatry Res. 2004;128:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalack GW, Healy DJ, Meador-Woodruff JH. Nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: Clinical phenomena and laboratory findings. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1490–1501. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinn WM, Aycicegi A, Harris CL. Cigarette smoking in a student sample: Neurocognitive and clinical correlates. Addict Behav. 2004;29:107–126. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar JC, Huang MX, Weisend MP, Sherwood A, Miller GA, Adler LE, et al. Interpreting abnormality: an EEG and MEG study of P50 and the auditory paired-stimulus paradigm. Biol Psychol. 2003;65:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(03)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin RJ, Buchwald JS. Midlatency auditory evoked responses: differential recovery cycle characteristics. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1986;64:417–423. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(86)90075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1987;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, McCandliss BD, Sommer T, Raz A, Posner MI. Testing the efficiency and independenceof attentional networks. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14:340–347. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman R, Adler LE, Waldo MC, Pachtman E, Franks RD. Neurophysiological evidence for a defect in inhibitory pathways in schizophrenia: Comparison of medicated and drug-free patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1983;18:537–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaniga MS, Ivry RB, Mangum GR. Cognitive neuroscience: The biology of the mind. 2. New York, London: W. W. Norton and Company; 2002. p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn SM, Sussman S. Why patients smoke letter. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990;41:1027–1028. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.9.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff WR, Williamson PD, Vangilder JC, Allison T, Fisher TC. Neural origins of long latency evoked potentials recorded from the depth and from the cortical surface of the brain in man. Prog Clin Neurophysiol. 1980;2:126–145. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald T, Boutros NN, Pezer N, Oertzen J, Fernandez G, Schaller C, Elger CE. Neuronal substrates of sensory gating within the human brain. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:511–519. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01673-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall G, Habbits P. Shadowing on the basis of contextual information in individuals with schizotypal personality. Br J Clin Psychol. 1996;35:595–604. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1996.tb01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerger K, Biggins C, Fein G. P50 suppression is not affected by attentional Manipulations. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;31:365–377. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90230-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MR, Adler LE. Transient impairment in P50 auditory sensory gating induced by a cold-pressor test. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;33:380–387. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90328-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollaikou A, Joseph S. Further evidence that tobacco smoking correlates with schizotypal and borderline personality traits. Pers Individ Dif. 2000;29:191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon ER. A review of the effects of nicotine on schizophrenia and antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:1346–1350. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.10.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AW, Cohen JD, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Dissociating the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex in cognitive control. Science. 2000;288:1835–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod CM. Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: an integrative review. Psychol Bull. 1991;109:163–203. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhie A, Chapman J. Disorders of attention and perception in early schizophrenia. Br J Med Psychol. 1961;34:103–116. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1961.tb00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LS, Burns SA. Gender differences in schizotypic features in a large sample of young adults. J Nerv Ment/Dis. 1995;183:657–661. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Downey KK, Stelson FW, Pomerleau CS. Cigarette smoking in adult patients diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Subst Abuse. 1995;7:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Q J Exp Psychol. 1980;41A:19–45. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Petersen SE. The attention systems of the human brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. The Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ): A measure of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:555–564. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taiminen TJ, Salokangas RKR, Saarijaervi S, Niemi H, Lehto H, Ahola V, Syvaelahti E. Smoking and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: A pilot study. Addict Behav. 1998;23:263–266. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L, Crawford HJ. The Moderation Influences of the Schizotypy Personality and the Smoking Status on the Attention Performances. Paper accepted at the 24th Annual Meeting of Cognitive Science Society (CogSci); Stresa, Italy. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wan L, Crawford HJ, Boutros N. P50 sensory gating: Impact of high vs. low schizotypal personality and smoking status. Int J Psychophysiol. 2006;60:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisser R, Weisbrod M, Roehrig M, Rupp A, Schroeder J, Scherg M. Is frontal lobe involved in the generation of auditory evoked P50? Neuroreport. 2001;12:3303–3307. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200110290-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PM, Yee CM. Effects of attentional and stressor manipulations on the P50 gating response. Psychophysiol. 1997;34:703–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH, Wellman NA, Allan LM, Taylor E, Tonin J, Feldon J, Rawlins JNP. Cannabis use correlates with schizotypy in healthy people. Addiction. 1996;91:869–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woldorff MG, Hillyard SA. Mogulation of early auditory processing during selective listening to rapidly presented tones. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1991;79:170–191. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(91)90136-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood C, Wolpaw J. Scalp distribution of human auditory evoked potentials: Evidence for overlapping sources and involvement of auditory cortex. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1982;54:25–38. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(82)90228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XJ, Domino EF. Effects of tobacco smoking on topographic EEG and Stroop test in smoking deprived smokers. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2000;24:535–546. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(00)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]