Abstract

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements were performed on isolated core and intact Photosystem I (PS I) particles and stroma membranes from Arabidopsis thaliana to characterize the type of energy-trapping kinetics in higher plant PS I. Target analysis confirms the previously proposed “charge recombination” model. No bottleneck in the energy flow from the bulk antenna compartments to the reaction center has been found. For both particles a trap-limited kinetics is realized, with an apparent charge separation lifetime of ∼6 ps. No red chlorophylls (Chls) are found in the PS I-core complex from A. thaliana. Rather, the observed red-shifted fluorescence (700–710 nm range) originates from the reaction center. In contrast, two red Chl compartments, located in the peripheral light-harvesting complexes, are resolved in the intact PS I particles (decay lifetimes 33 and 95 ps, respectively). These two red states have been attributed to the two red states found in Lhca 3 and Lhca 4, respectively. The influence of the red Chls on the slowing of the overall trapping kinetics in the intact PS I complex is estimated to be approximately four times larger than the effect of the bulk antenna enlargement.

INTRODUCTION

The process of photosynthesis in its early stages occurs in highly specialized membrane-bound pigment-protein complexes. These complexes are divided into two families, depending on the terminal electron transfer cofactors: i), the type II reaction centers (RCs), like Photosystem (PS) II and some bacterial RCs; and ii), the family of the type I Fe-S RCs to which PS I belongs. Higher plant PS I consists of a core complex of ∼12 protein subunits and an outer antenna semiring of four units (1,2). The whole complex hosts ∼200 cofactors, among which six redox active chlorophyll (Chl) molecules located in the RC, 97 Chls in the core antenna, 56 in the outer antenna, and ∼9 Chls fill the gap between the two antennae (for a review, see Fromme and colleagues (3)). In addition, PS I carries the redox active cofactors on the acceptor side and a large number of carotenoid molecules further (2) (for a high-resolution structure of the cyanobacterial PS I, which is to a large extent conserved in the core of higher plant PS I; see Jordan and colleagues (4)).

The six Chl molecules in the RC are strongly excitonically coupled among each other, as predicted by theoretical calculations (5,6) and thermodynamic analyses (7) and confirmed by experimental studies, e.g., ultrafast transient absorption (TA) (8–10), mutant studies (11), and Raman scattering (12). This strong coupling of the RC Chls and the ensuing widening of the covered energy spectrum might be of great significance for the efficient and fast energy transfer (ET) from the surrounding core antenna Chls to the RC (13).

Owing to its structure, PS I possesses several specific properties distinguishing it from other photosynthetic complexes. This study is concerned with two of these features. First, the inseparability of the core antenna and the RC of PS I, which together with the high Chl density render specific time-resolved studies of the electron transfer processes in the RC very difficult. The second characteristic is the presence of Chl forms that have lower energy than the RC Chls (red Chls) (for a review, see Karapetyan and colleagues (14)). These Chls, apparently, are highly important for the overall function of PS I as they are conserved during evolution and even increased in higher plants with respect to algae. To reveal the function of these red Chls, their role in the light-trapping kinetics must be characterized.

During the past few years, great efforts have been made by several research groups to analyze the trapping kinetics in PS I, but no general agreement has been reached. The red Chls, supposedly located mainly at the periphery of the monomeric complex, play a decisive role in controlling the overall kinetics. In some of the recent ultrafast studies on cyanobacterial PS I, the kinetics was discussed as balanced between trap limited and transfer-to-trap limited (15). In contrast, other authors proposed purely transfer-to-trap-limited kinetics on the basis of a nonequilibrium trapping interpretation of the time-resolved fluorescence and TA data (16–20) and theoretical modeling (6). In some early minimal models, purely trap-limited kinetics was also proposed (21,22) for cyanobacterial PS I. However, these studies lacked either sufficient time resolution in the measurements (21) or did not attempt a detailed kinetic modeling (22). In addition some basic criticism may be applied to most of the above-mentioned studies since the analysis of the experimental data either did not account for some of the important features of the electron pathways, e.g., charge recombination (16–18,20), or used the highly questionable assumption of equality of the excited state quenching processes in open and closed PS I complexes (19). In fact, an increase of ∼12% in the fluorescence quantum yield after P700 oxidation was observed by Byrdin and co-workers (15), which implies a different trapping kinetics in PS I with closed RC.

Irrespective of the discrepancies between the models suggested by different groups, the underlying data themselves are often quite similar, with energy equilibration times ranging from a few picoseconds to a few tens of picoseconds and a main trapping lifetime of ∼20–25 ps (15–19,22,23) in PS I-cores and additional component(s) in intact higher plant PS I. However, the 20–25 ps component assigned to main trapping in many of these works is a complex component and most likely represents a mixture of more than one process. Recent TA and fluorescence decay studies on PS I-core particles from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii carried out in our laboratory (9,24) shed more light on the trapping kinetics of PS I-cores. One important conclusion of these studies was that a charge recombination step was required for the description of the energy and charge transfer events in PS I. Furthermore for the first time, to our knowledge, these studies resolved the excited equilibrated RC* (i.e., excited state of the group of the six RC Chls) of PS I as a separate compartment both spectrally and kinetically. According to these results, energy trapping in the PS I-core is limited by the charge separation (CS) rather than the ET, i.e., the kinetics in PS I-cores that are devoid of red Chls is purely trap limited. Additionally, these studies for the first time, to our knowledge provided evidence for the accessory Chl-ec2 as a primary donor in PS I RC (9).

Recently, Ihalainen and colleagues investigated the excited state dynamics in intact higher plant and algae PS I particles using time-resolved fluorescence with high resolution and suggested transfer-to-trap-limited kinetics (25). The authors used a model with two red Chl compartments for the description of their data. However, the conclusions drawn from that modeling are subject to criticism since the internal conversion rate to the ground state for the light-harvesting complex I (LHC I) bulk-red compartment is very high (6.81 ns−1), which—if correct—would lead to high quantum yield losses for CS. So far, there exists no convincing evidence that radiationless deactivation to the ground state from excited red Chls is efficient enough that such a high deactivation rate is justified. Interestingly, the red PS I-core compartment in their model has a high transition rate directly to the trap (i.e., the charge-separated state), which—if this compartment is interpreted as a red Chl located somewhere in the bulk antenna—implies that most of the energy reaching this red Chl compartment does not pass through the core antenna before CS. Such a scenario has been ruled out however by, e.g., Jennings and co-workers (26). We will show in this work that the compartment attributed by Ihalainen and colleagues to red PS I-core does in fact represent the RC itself. However in an alternative model, Melkozernov and colleagues suggest a diffusion-limited step in the trapping kinetics of intact Chlamydomonas PS I particles because of a bottleneck in the ET from the peripheral antenna (LHC I) to the PS I-core antenna due to the presence of regions of weak coupling (27). Additionally, the latter authors suggest slow energy equilibration among the LHC I complexes.

The functional and biological roles of the peculiar red Chls represent a feature of the PS I antenna that is still not well understood. Certainly, the presence of red Chls does not impair the quantum efficiency of PS I substantially, if at all, since the lifetime of the excited state of a Chl in a protein is on the timescale of several nanoseconds, whereas the longest excited state decays of red Chls in PS I are only up to ∼100 ps. Some authors proposed that the red Chl forms provide a physiological advantage for the plants in special light conditions (28–30). Others discussed their role in connection with the funnel model of ET to the RC (31) or suggested their participation in photoprotection (14,29,31–34).

Typically, the red Chls have very broad red-shifted spectra due to a high electron-phonon coupling (35–39). In cyanobacteria these red Chls are located in the core of PS I. Low temperature studies reveal the presence of two to three main absorption bands at 708 nm and 719 nm (C708 and C719) (35,38) and possibly also C715 (36) for Thermosynechoccocus sp. Two red Chl forms are found at low temperature also in Synechocystis at 708 nm and 714 nm (37). Unfortunately, the exact position of the Chls responsible for the red-shifted absorption and fluorescence in the structure is not known. According to Melkozernov and colleagues (40), they are located in the vicinity of the RC, contrary to the more distant position proposed by other authors (15,17,37,41). For cyanobacterial PS I, a highly likely position is in the monomer-monomer interaction region of the trimer (4).

In contrast to cyanobacteria, the red Chls in higher plants appear to be located almost exclusively in the peripheral LHC I complexes (42) although Ihalainen and colleagues (25) assign one red Chl state to the core antenna (vide supra). Several studies on preparations of PS I particles and LHC I complexes have demonstrated convincingly that the main part of the red-shifted fluorescence of intact PS I could be explained well by Chls situated in the peripheral LHC I complexes (26,43) and/or at the interface between the core complex and the peripheral antenna (27,44,45) possibly involving some of the so-called gap Chls (46). A very small contribution of red-shifted fluorescence from the PS I-core is supported by a site-selective and high-pressure spectroscopy study on PS I-200, PS I-core, and LHC I, which suggests the presence of three red Chl states in the intact PS I complex. Two of them (C706 and C714) were proposed to be located in the core with extremely small emission yield (F722 nm), and one in the LHC I absorbing around 710 nm (emission F730 nm) (39). The properties of the red Chls differ strongly among the different LHC I complexes. In Lhca 1 and Lhca 2, the pigments responsible for the red shift at low temperature emit at ∼686 nm and 701 nm, respectively (47), and thus cannot be responsible for the red Chl fluorescence observed in intact PS I. For Lhca 3 and Lhca 4 the red emission maxima are, however, located at 725 nm and 735 nm, respectively (48), and are likely to be responsible for the red emission in intact PS I. These spectral differences let us expect more than one red Chl component arising from the peripheral LHC I complexes in time-resolved studies.

The energy exchange of the different red Chls with the bulk antenna system (i.e., the isoenergetic Chls of the PS I-core complex, the gap Chls, and the LHC I complexes, excluding the red Chls) was found to take place in the range of a few to tens of picoseconds (15,17,25,49–53). Due to this relatively slow energy equilibration and the related slowing down of the overall trapping kinetics, it was concluded that the red Chls in PS I can hardly increase the trapping efficiency (17), as discussed earlier. Rather their role should be different. Very clearly they increase the absorption cross section in a part of the solar spectrum that is not used efficiently otherwise (28,54). In addition they may have a photoprotective role (14,29,32–34). The shift of the red Chls location in higher plant PS I toward the periphery of the complex might be attributed to differences in their function or/and to differences in the environmental conditions as compared to cyanobacteria.

Disagreement exists also about the influence of the bulk antenna enlargement and the presence of red Chls on the overall trapping kinetics. According to the work of Jennings and co-workers (26), these two factors have an equal influence on the kinetics. These authors suggested that the ∼30 ps and ∼80 ps components in the fluorescence kinetics of PS I-intact particles are due to the dynamics of the outer antenna red Chls. Alternatively, Ihalainen and colleagues proposed a dominant role for the red Chls (25).

It follows from the discussion above that most aspects of the kinetics of higher plant PS I are not well understood yet. By comparing the ultrafast fluorescence data from PS I-cores with those of intact PS I, this work aims at characterizing in detail the ET and CS kinetics in higher plant PS I. We focus in particular on precisely characterizing the influence of the outer antenna and of the red Chls on these processes and on resolving the RC* state kinetically and spectrally for higher plant PS I. The discussion will address in detail the question of possible bottlenecks in the energy flow between the various antenna compartments. A further point concerns the possible role of detergents for the functional coupling of the peripheral LHC I complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PSI-LHCI particles (PSI-intact particles) were isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana thylakoids by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation after solubilization with 1% β-DM (n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside), using the protocol described in Croce and colleagues (7). Antenna and core moieties were dissociated by treating with 1% β-DM and 0.5% zwittergent-16. PS I-core particles and LHC I were isolated by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation as in Croce and colleagues (7). Stroma membranes were purified by mechanical fractionation with a Yeda-press, followed by differential centrifugation according to previous reports (55).

For the time-resolved fluorescence measurements, the isolated core and intact PS I particles were diluted in 30 mM tricine buffer (pH 7.8), containing 500 mM sucrose and 0.009% α-DM (n-dodecyl-α-D-maltoside) to an optical density of ∼0.3 cm−1 at the Chl QY maximum. The medium also contained 40 mM sodium ascorbate and 60 μM phenazine methosulfate as redox agents to keep the RCs open during the measurements.

The single-photon timing technique was used to perform picosecond time-resolved fluorescence measurements. The setup consists of a synchronously pumped, cavity-dumped, mode-locked dye laser at 800 kHz repetition frequency with DCM (4-dicyanomethylene-2-methyl-6-p-dimethylaminostyryl-4H-pyran) as a laser dye (20,24). The pulse of the dye laser has a full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of 10 ps, and the whole response of the system is ∼30 ps FWHM, which after deconvolution results in a time resolution of 1–2 ps. The sample was placed in a rotating cuvette (10 cm diameter, path length of 1.5 mm) moving sideways at 66 rpm and rotating at 4200 rpm. The laser intensity at the sample was ∼0.05 mW, ∼0.8 mm spot diameter. Such experimental conditions ensure complete rereduction of the RC before the next excitation occurs. Under these conditions <1% of the particles receive a second laser excitation during the time they spend in the laser beam. The excitation wavelength was 663 nm to selectively excite the bulk antenna Chls. Measurements were carried out at ambient temperature (21°C ± 2°C).

Fluorescence decays were analyzed by means of global and target analyses (56,57). Global analysis is a combined mathematical fitting of the decay curves at different wavelengths done in a single fitting procedure. The analysis results in lifetimes and decay-associated spectrum (DAS), describing the whole set of original data. In the more elaborate target analysis, kinetic models are fitted to the data in a global fashion. Such an approach leads to a physically meaningful description (rate constants and spectra of the different compartments (species-associated emission spectrum; SAES)) and gives detailed information about rate constants of energy and electrons of the processes taking place in the investigated system. Several physically reasonable models are usually tested for their compatibility with the data.

RESULTS

Global analysis

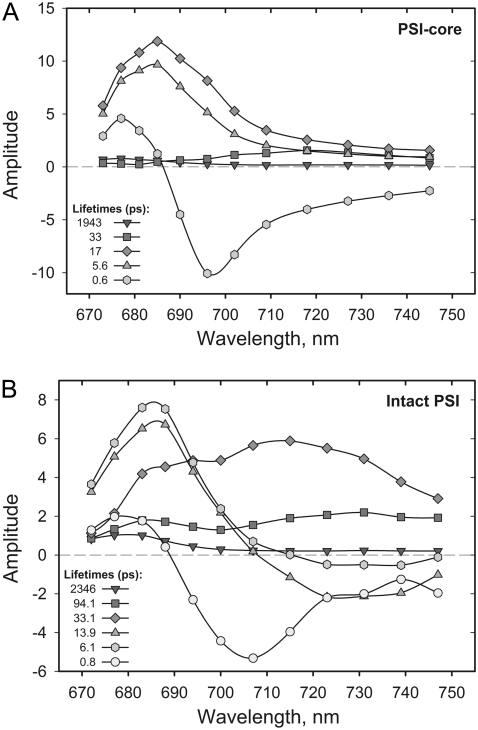

The fluorescence decay kinetics after 663 nm excitation of PS I-core and intact particles and of purified stroma membranes (containing dominantly intact PS I complexes) were recorded with 1–2 ps time resolution at different emission wavelengths. The excitation wavelength was chosen to avoid direct excitation of the red Chls and to ensure the start of the excited state dynamics to be in the bulk antenna. Global analysis was applied on the time-resolved data (Fig. 1).

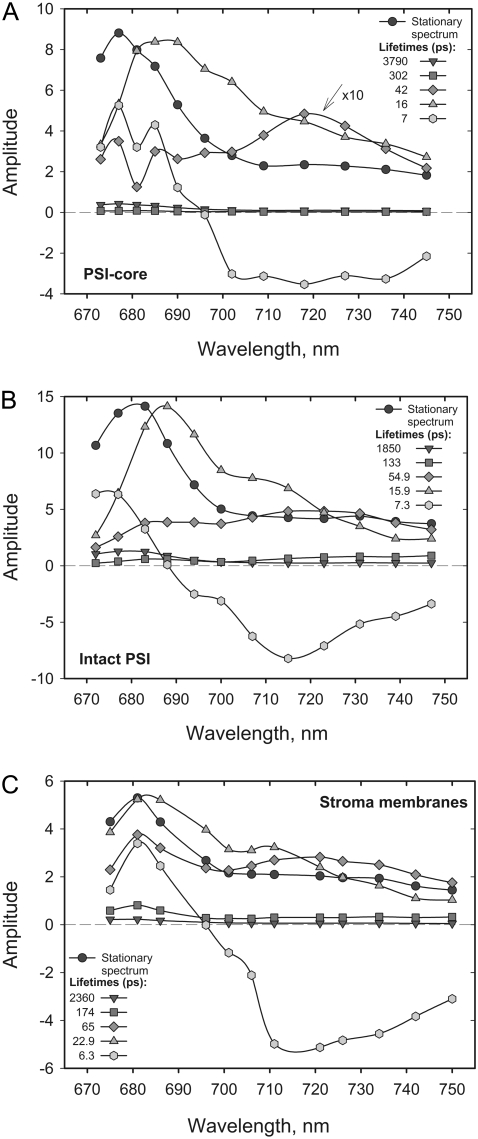

FIGURE 1.

Steady-state fluorescence spectra (black circles) and DAS and lifetimes of the fluorescence from A. thaliana PS I-core (A), PS I-intact (B), particles and stroma membranes (C) obtained through global analysis of the fluorescence decay data, λexc = 663 nm excitation. χ2 = 1.032, χ2 = 1.024, and χ2 = 1.04, respectively.

At first glance the sets of lifetimes describing the fluorescence decays in the PS I-cores and PS I-intact particles look similar, in particular for the lifetime range below 20 ps. Significant differences can be observed in the amplitude of the 40–55 ps lifetime, which has nearly zero amplitude in the core particles but has a large amplitude in the intact PS I and in the stroma membranes. Due to the broad and red-shifted spectrum of the 55 ps lifetime in the PS I-intact particles and in the stroma membranes, this component can be clearly attributed to the dynamics of a red Chl excited state. The lack of red-shifted DAS components for higher plant PS I-cores is in agreement with other studies (26,43,44) and questions the assignment of the compartments in the modeling performed by Ihalainen and colleagues (25).

The main fluorescence decay in both systems occurs with a lifetime of ∼16–17 ps. This component has a relatively broad spectrum peaking in the blue range (680–685 nm) and most likely reflects the energy-trapping processes from at least partially equilibrated antenna, also comprising RC* fluorescence. However, unambiguous assignment of the lifetimes to a particular process at this stage of the analysis is not possible. Quite generally, the observed lifetimes and their DAS represent a weighted mixture of all the kinetic processes occurring in the system. Nevertheless, similar lifetime components were found in most of the recent studies of PS I energy trapping kinetics (8,24–27). Nonetheless, not all of the short-lived components were resolved in some of these works. The shortest lifetime component (∼7 ps) possesses positive-negative amplitude with a zero crossing around 685 nm for intact PS I and 695 nm for PS I-core. This component thus represents the slowest part of the overall energy equilibration dynamics. For intact PS I, the data are thus very similar to our previous data on intact PS I from maize (20) except that the fastest lifetime component is now resolved into two components. Additionally, we find a nearly negligible long-lived component in the nanosecond time range, which can be assigned to a small amount of energetically decoupled Chls or antennae present in the sample. Our experience shows that the amplitude of this component is strongly dependent on the detergent concentration in the buffer used for the measurement. We observed that detergent concentrations right at the onset of the micelle formation (i.e., the critical micelle concentration) are the least disruptive for the complexes. A similar observation concerning the uncoupling of peripheral LHC I complex was made earlier (58).

The comparison between the DAS of the stroma membranes and the detergent-isolated intact PS I particles (Fig. 1, B and C) reveals some slight spectral differences in the blue part (∼680–690 nm) of the spectra of some of the decay components. These differences are presumably due to some lifetime overlap with a minor contamination by PS II in the stroma membranes, which is expected. Nevertheless, the set of lifetimes describing the fluorescence decay kinetics in stroma membranes is nearly identical to the one from detergent-isolated intact PS I. Importantly, the DAS in the red spectral part are highly preserved (Fig. 1, B and C), which means that during the isolation of the intact PS I particles the red Chl compartments were not disrupted by the detergent. For these reasons we will describe here in detail only the analysis on the purified intact PS I particles.

Target analysis

As mentioned above, global analysis is a pure mathematical fitting and does not provide much physical insight and information. Principally, after obtaining some qualitative information from the former approach, kinetic modeling by target analysis was performed on the data to fully characterize the underlying processes within compartment models, which represent models of reduced complexity of the system (59). This reduction of complexity is required since the time resolution and signal/noise ratio does not allow resolution of single ET steps. Thus for the purpose of kinetic modeling, the investigated system is separated into physical domains with similar properties, e.g., bulk antenna, red Chls, etc. For each sample PS I-core and PS I-intact particles, several different kinetic models were tested on the data. Figs. 2 and 3 show the final results of the target analysis.

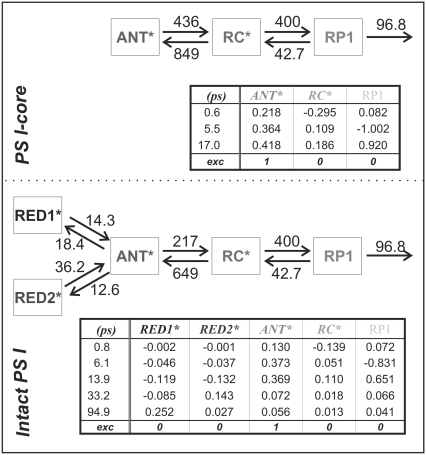

FIGURE 2.

Compartment models with rate constants (ns−1) (top), lifetimes and eigenvectors (bottom) for the PS I-core (top box) and PS I-intact (bottom box) particles. χ2 = 1.1 and χ2 = 1.01, respectively.

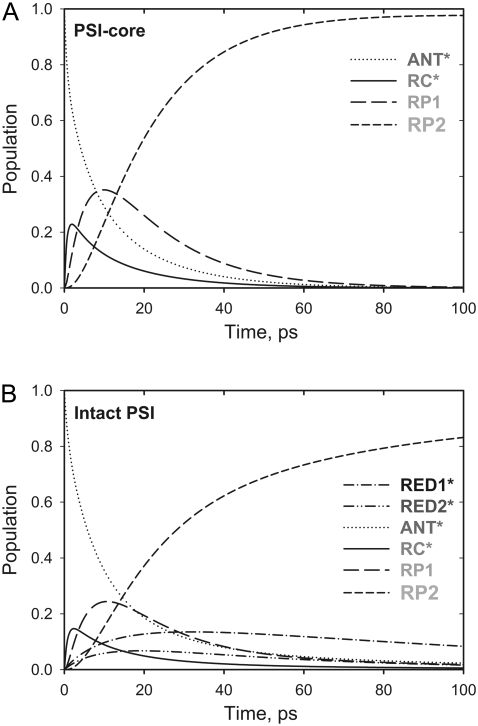

FIGURE 3.

Time dependence of the relative populations for the different model compartments in Fig. 2. (A) PS I-core particles; (B) PS I-intact particles.

The models yield the rate constants, the weighted eigenvector matrix, and the time course of the relative populations of the involved states. For a detailed description of these terms, see Müller and colleagues (9). Fig. 4 illustrates the corresponding SAES. The models describing the trapping kinetics in PS I-core and in intact PS I particles differ in the presence of red Chls. Since no significant red-shifted fluorescence compartment was observed in the global analysis of the core particles, red Chl compartments were not included in the model describing the kinetics of the core. In fact, such models were tested but did not lead to satisfactory results. After performing the kinetic modeling, we recalculated the DAS for the studied complexes (see Fig. 5). Besides the lifetime components directly associated with the model compartments, one (intact PS I) or two (PS I-core) additional components are present that are attributed to some minor content of detached LHC I and/or functionally decoupled Chls (vide supra).

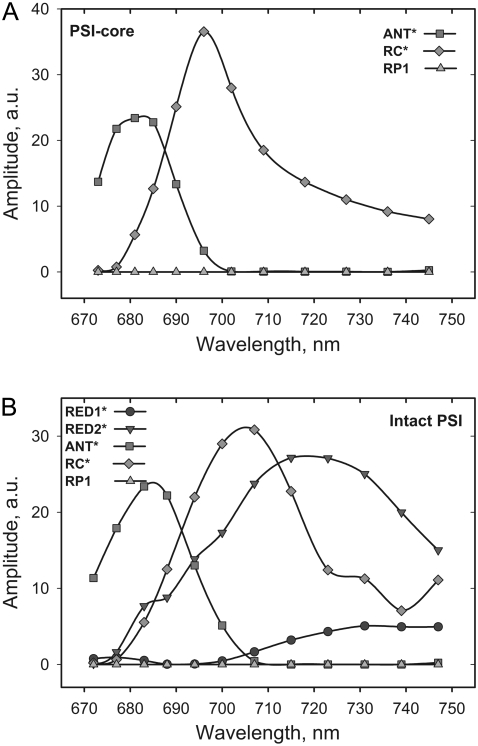

FIGURE 4.

SAES from the modeling of the time-resolved fluorescence data of core (A) and intact (B) PS I particles.

FIGURE 5.

DAS of PS I-core (A) and PS I intact (B) particles recalculated from the rates and SAES of the kinetic models. In PS I-core (A) the last two lifetimes (33 ps and ∼1.9 ns) and the last one (2.3 ns) in intact PS I (B) reflect the additional components.

DISCUSSION

Reaction center kinetics

A key feature of the presented models is the presence of a fluorescing compartment representing the excited RC Chls (Fig. 2). Such a compartment was already resolved in our previous studies on green algae PS I (9,24) and has a solid theoretical and experimental base (5,7–9,11,12). Due to the strong excitonic coupling among the six RC Chls the physical properties of this group of pigments are significantly modified in comparison with the antenna Chls (6). Another reason is their spectral role as electron transfer cofactors and their relatively large distance from the core antenna Chls (1,2,4). Therefore the RC* kinetics should be separable and be described by an individual model compartment. Furthermore the proper rates of the first electron transfer steps can only be extracted if the RC* is resolved as a separate compartment. It was indeed possible to resolve the RC* kinetics in our data (see Figs. 2 and 3). The transient population of the RC* compartment reaches ∼22% in the PS I-core and 15% in the intact PS I particles (Fig. 3). We also tested again whether a charge recombination step from the first radical pair (RP1) is required to describe our data (Fig. 2), following the recent studies of Holzwarth and colleagues (24). Clearly any models that did not include such a process gave no reasonable description of the kinetics, in agreement with our previous findings on green algae PS I-cores (9,24).

The electron transfer kinetics in the RC for both samples is the same within the error limits, which, on the one hand, is an expected result since this part of the PS I particle is not affected by the isolation procedures and should be independent of the antenna size. On the other hand, the fact that the kinetics in both particles is described by the same electron transfer rates, despite the largely different overall kinetics, provides very strong support for the validity of the presented models. The CS rate is ∼400 ns−1 and is in the same range as the one obtained for green algae PS I-cores (9,24). Additionally, we are also able to resolve the decay of RP1. In both of the studied complexes, this process occurs with a lifetime of ∼14–17 ps, again in agreement with the above-mentioned data on green algae cores (rate constant of 97 ns−1).

As can be deduced from the table of the weighted eigenvector matrix in Fig. 2, the apparent CS lifetime is 5–6 ps, in accordance with our previous data (9,24). This lifetime is several times shorter than the apparent CS proposed by other authors (25–27). The discrepancy cannot be attributed to major real differences in the experimental data but rather to the fact that we include and resolve the RC* compartment in our data analysis. As was discussed above, excluding some inherent system properties from the model assumptions can easily lead to inconsistent interpretations of the results. In the kinetic models of other groups the 20–25 ps lifetime component was attributed to the apparent lifetime of the primary CS. Such an interpretation is in disagreement with our data. However both our earlier data (9,24) as well as the data here demonstrate that this lifetime reflects the secondary electron transfer step.

Energy transfer dynamics

Our data analysis reveals that the main part of the energy equilibration between the bulk antenna (ANT*) and the RC (RC*) occurs on a sub-ps timescale (Fig. 2). The ratios of the corresponding forward and backward rates are ∼0.5 for the PS I-core complex and ∼0.3 for the intact PS I, in good agreement with the ones predicted from the detailed balance calculation

|

where kf and kb denote the forward and backward ET rates and NRC and NANT denote the degeneracy factors for the different compartments (NRC = 6, for intact PS I NANT = ∼160, for core PS I NANT = ∼97), and kBT is the Boltzmann factor). The increase of this ratio in the PS I-core complex correlates with the reduction of the bulk antenna size due to the removal of the LHC I complexes and possibly also some of the gap Chls. The ultrafast energy equilibration of the bulk antenna with the RC proves that there is no rate-limiting step in the kinetics due to the ET between the peripheral and the core antennae and rules out the diffusion-limited model proposed by Melkozernov and colleagues (27). This result not only suggests that the gap Chls are well coupled with the rest of the bulk antenna system, but it also shows that they serve as an efficient bridge for the ET from the peripheral LHCs of the intact PS I complex. We observe no evidence whatsoever for any bottleneck across the bulk Chls.

The ET kinetics of the red Chls can be directly examined with the help of the weighted eigenvector matrix (Fig. 2). The energy equilibration between the bulk antenna and the red compartments proceeds with a main equilibration time of ∼14 ps, in good agreement with studies on isolated LHC I complexes (52,53). In the latter study the main energy equilibration lifetime of the bulk antenna and the red Chls in LHC I is not longer than ∼8 ps. This lifetime is slightly shorter than the one detected here. However, an increase of the energy equilibration lifetime in the intact PS I complex is expected, given that there is a general enlargement of the bulk antenna moiety. Nevertheless, this lifetime is much longer than the lifetime reflecting the energy equilibration between bulk antenna and RC and slower than the apparent CS lifetime. In addition, some slower equilibration occurs for the RED1* compartment. It is evident from the eigenvector matrix that the two red Chl states decay with distinct lifetimes, i.e., RED1* decays with ∼95 ps and RED2* decays with ∼33 ps lifetime. This result rules out the conclusion made by Engelmann and colleagues for heterogeneity of the red Chls kinetics (26). Their conclusion is based on a proposed mixing of the dynamics of the two red Chl states, leading also to the mixing of the spectra (vide infra). However, our data do not support this hypothesis, and we believe rather that their finding of a mixed kinetics is a direct consequence of the noninclusion of an RC* compartment in their model, which also emits red fluorescence. Addition of such a compartment clearly leads to better separation of the red-shifted spectra. Another important observation is the relatively low transient populations of the two red Chl compartments. RED1* reaches a maximum transient population of ∼13.6% and RED2* ∼6%. The low population of the red states follows from the low ET rate constants and implies low efficiency of the ET from the bulk antenna to these compartments. A direct consequence of the slow red Chl ET rates is the fact that most of the excitation energy will be trapped from the bulk antenna before it ever reaches the red Chls. The slow energy exchange between bulk Chls and the red Chls in the peripheral LHC I complexes requires a special analysis. It must be caused either by poor spectral overlaps and/or by an unfavorable arrangement or distance of the red Chls relative to the surrounding Chls.

Fluorescence spectra of the model compartments

One essential part of the modeling is the extraction of physically reasonable spectra (SAES) for each compartment. These spectra play a critical and decisive role when judging the adequacy of a model, in addition to the rates and the χ2 fit quality criterion. The SAES reflect the fluorescence spectrum of each excited state compartment present in the model as if it were measured isolated from the whole entity (56). The corresponding SAES for PS I-core and intact PS I particles are presented in Fig. 4. Since the number of the cofactors and the kinetics in the RC (e.g., CS, charge recombination, and secondary electron transfer rates) for both samples are preserved, the spectrum of RC* should be the same in both samples. In contrast the bulk ANT* spectrum may change to some extent since additional Chls are comprised in the bulk ANT* for the intact PS I. The spectrum of RC* is slightly broader for intact PS I than for PS I-cores. This may hint at some incomplete resolution of the ANT* and RC* equilibration.

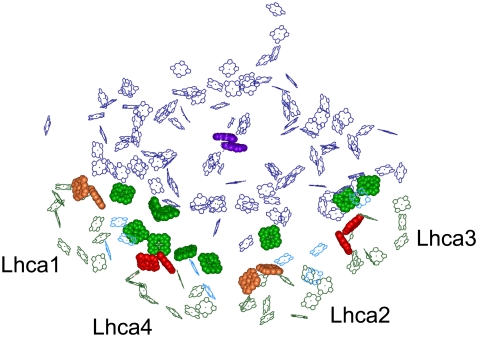

Additionally, for the PS I-intact complexes two red-shifted spectra accounting for the presence of red Chl forms are obtained. These spectra agree very well with our previous low temperature experiments on isolated LHC I complexes (48). In accordance with this study, the spectrum of the compartment with a main 33 ps decay lifetime (RED2*), which peaks at ∼721 nm, should account for the fluorescence observed in Lhca 3 complexes (725 nm emission at low temperature) (48). The other red compartment (RED1*) with a lifetime of ∼95 ps peaks at ∼733 nm and should represent the red Chl state in Lhca 4 (48). As a result, for the first time in this study we assigned the red kinetic components of intact PS I particles to the red Chls located in the different isolated LHC I complexes (Fig. 6). Both spectra are very broad and strongly red shifted versus the absorption, reflecting both exciton coupling and strong electron-phonon coupling as proposed by many authors (35–39,60), possibly caused by charge transfer states.

FIGURE 6.

Structural picture exemplifying the role of gap Chls in ET to the PS I RC. Chl molecules of the structure from Ben-Shem and colleagues (1), deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession number 1qzv, are shown. Gap and linker Chls are shown in light green and cyan, respectively, whereas the special pair P700 is in purple. Chls in sites A5 and B5 (603 and 609 according to Liu and colleagues (68) of antenna polypeptides are shown as well: they are in red in the case of Lhca 3 and Lhca 4, and in orange for Lhca 1 and Lhca 2, according to their fluorescence emission properties (48).

Provided that the SAES (Fig. 4) of the model compartments represent their fluorescence spectra (vide supra), one can calculate via the Kennard-Stepanov relation (61,62) the corresponding absorption spectra (see Supplementary Material for details of this calculation and analysis and for the absorption spectra of ANT*, RC*, RED1*, and RED2*). Similar bands were found by Ihalainen and colleagues in Gaussian decomposition of the LHC I absorption spectrum (63). However, the calculated absorption spectrum of RED2* clearly represents an equilibrated state between a red Chl compartment and a nearby pool of higher energy Chls rather than a pure red Chl form. In contrast RED1* has a typical red Chl absorption spectrum, peaking at ∼710 nm. The RC* spectrum is in agreement with the spectrum found in our TA studies of PS I-cores (9). The relatively low transient population (Fig. 3) of the RED1* compartment can be explained by the minor spectral overlap with ANT*. As a result of the kinetic modeling, the DAS can also be presented with higher accuracy due to the better separation of the lifetimes describing the excitation dynamics in the system (Fig. 5). The shortest lifetime in the global analysis DAS (Fig. 1), which is apparently a mixture of two lifetimes, now is split into a sub-ps and ∼6 ps lifetime. This leads to an additional slight adjustment of the other lifetimes. We should note that the sub-ps component resulting from the target analysis in principle is below the actual time resolution of our apparatus. Nevertheless, this component follows implicitly from the kinetic models and is a global property of the overall kinetics and spectral shapes. It is not uncommon in target analysis that more and shorter lifetimes can be resolved than in simple global analysis (56). However, if such an additionally resolved lifetime falls below the resolution limit, it follows that the related errors for its spectral shape (DAS) and the rate constants that essentially contribute to this lifetime (in our case mostly ANT* and RC* transfer rates) have substantially larger errors than the other DAS and rates. This must be kept in mind when interpreting the data.

Error analysis reveals that the ANT* and RC* ET rates could be off by up to 30%. However it is important to note here that all our femtosecond TA data on PS I particles (9,64) clearly demonstrate the presence of this sub-ps component. In fact, unpublished femtosecond TA data on the intact PS I complex also show this ultrashort ET component with large amplitude. This component reflects to a large part the core antenna/RC equilibration. The spectral shapes of the DAS of the shortest lifetimes seem to indicate that part of the energy is still not completely equilibrated on the timescale of CS, because they are not conservative. This finding is in agreement with the results of other authors (25,27) who, however, used it as an argument to infer a transfer-to-trap or diffusion-limited type of trapping kinetics in PS I. Such an argument could well be misleading, since the decay of the fluorescence is a mixture of the decays due to all the processes occurring in the system, e.g., ET and CS, and additional analysis is in fact necessary to assign the actual limiting factor in the kinetics.

Trap-limited kinetics in higher plant PS I

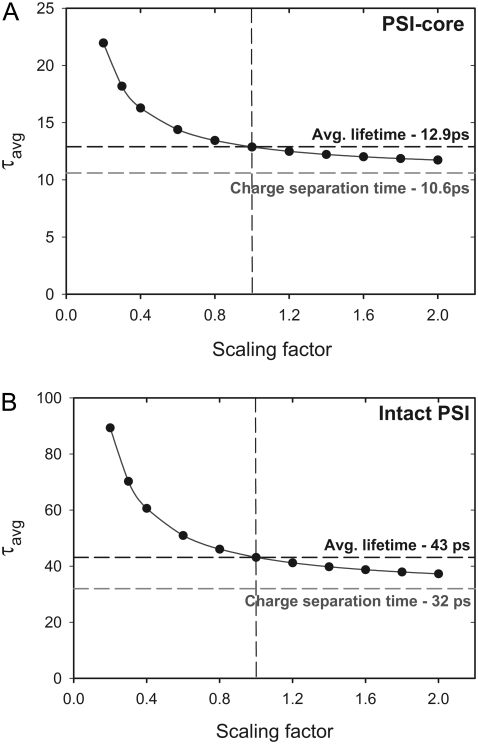

According to theory, the average lifetime for excited state decay in photosystems can be presented as a sum of two lifetimes: τavg = τET + τCS (65,66). The first one is the ET or migration lifetime (τET) that represents the average lifetime for the energy migration through the antenna to the RC. In PS I-core particles τET is equivalent to the average lifetime of the energy equilibration between the bulk antenna (ANT*) and the RC*. However in intact PS I particles, τET has a significant or even dominant contribution from the equilibration with the red Chls. The second one is the CS lifetime (CS) representing the average trapping (CS) lifetime of excitations that are already located on the RC. This lifetime reveals the contribution of the CS to the total excited state decay and should not be confused with the apparent CS lifetime, which is the lifetime component describing the apparent rise of the primary RP. Both terms, i.e., τET and τCS, depend, inter alia, on the antenna size.

The trap-limited case is realized if τavg is determined mainly by τCS, i.e., τCS/τET > 1. The contributions of τET and τCS can be calculated simply by scaling the ET rates (either ANT*-RC*, if the excitation is placed on the ANT* compartment, or RED*-ANT*, if the excitation is in the red) in the kinetic models (Fig. 2) to infinity (i.e., to ensure τET ≪ τCS). In this way the overall decay of the fluorescence will be entirely due to CS, and consequently the average lifetime will reflect exactly τCS. The same information can be obtained if in the kinetic model all excitations are created directly on the RC. The results are shown in Fig. 7 and Table 1. According to this scaling analysis, the ratio between the CS lifetime (τCS) and the ET lifetime (τET) in PS I-cores is ∼4.6, implying a fully trap-limited kinetics. In the intact PS I particles, this ratio is somewhat smaller (∼2.7) but still substantially higher than 1, and the kinetics is still well on the trap-limited side. It is interesting to note that our results disagree with the theoretical modeling of Sener and colleagues (67). In that work the calculated so-called first usage lifetime (which corresponds to τET in our description) is approximately three times larger than the one we observe (Table 1). Thus the authors were led to suggest a diffusion-limited trapping kinetics in intact higher plant PS I.

FIGURE 7.

Dependence of the average fluorescence lifetime (τavg) on the scaling of the ET rates (ANT*-RC*) in the kinetic models (Fig. 2). Scaling factor 1 (vertical dashed line) corresponds to the experimental situation.

TABLE 1.

Scaling analysis of the energy transfer rates (ANT*-RC* and RED*-ANT*) in the models (Fig. 2) depending on the excitation of different compartments in the core and intact (Int) PS I particles

| Excited compartment

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| τavg (ps) | 12.9 | 43.1 | 110 | 70 | 90 |

| τET (ps) | 2.3 | 11.8 | 67 | 27 | 47 |

| τCS (ps) | 10.6 | 31.3 | 43 | 43 | 43 |

| τCS/τET | 4.6 | 2.65 | 0.64 | 1.6 | 0.9 |

For details of the meaning of the parameters, see text.

The decrease of the τCS/τET ratio in intact PS I complexes in comparison to PS I-cores is caused primarily by the presence of the red Chls and their relatively slow ET with the other pigments and to a much smaller extent only by the larger bulk antenna system. The effect can be explained with the dependence of τCS not only on the CS rate but also on the equilibrium excited state population of the compartments. The RC population is lower in intact PS I particles than in PS I-cores, as can be seen from the population dynamics in Fig. 3. Nevertheless, these substantial effects of the red Chls do not suffice to change the type of the kinetics, which also remains fully trap-limited for the intact PS I complex.

Nature of the red Chl energy transfer

To gain more insight into the properties of the system, it is useful to perform further scaling analyses separately for the ET rates of the red Chl compartments to evaluate the type of their kinetics. The results of such analyses are summarized in Table 1. Interestingly, the two red Chl states differ largely in their kinetics. RED1*, which has a longer lifetime and the reddest spectrum, shows diffusion-limited kinetics if all the initial excitation is created on this red Chl. In contrast, the ET dynamics of the other red compartment (RED2*), whose ET kinetics is much faster than RED1*, is not diffusion limited. These results correlate with the results from Kennard-Stepanov calculations for the spectral overlap between ANT* fluorescence and red compartments absorption (see Supplementary Material). If the scaling analysis is done for equal excitation of both red Chl compartments (Table 1, RED1/2) and zero bulk antenna excitation, the overall kinetics turns out to be balanced between the two limiting cases. Such a difference in the kinetic properties between the red Chls can be attributed to some differences in their function.

Influence of red Chls on the energy-trapping process

The extension of the PS I-core antenna with the peripheral LHC I complexes which contain the red Chls substantially influences the overall trapping kinetics. This effect is not due merely to the presence of red Chls but also to the extension of the bulk antenna moiety. To quantify this effect, additional data analysis has to be carried out. Since the average decay of the excited state is a sum of two terms (τET and τCS, vide supra), the contributions from the increased bulk antenna and the presence of red Chls should be estimated separately, which is possible on the basis of the rate constants provided in Fig. 2. We have thus performed the scaling analysis of the model describing the trapping kinetics for intact PS I particles without including the red Chl compartments and keeping all other rates the same as in the model of Fig. 2 (i.e., ET rates between the bulk antenna and the RC* and the electron transfer rates). This allows us to evaluate the contribution of the bulk antenna enlargement alone on the increase of τET, τCS, and τavg. The results of this analysis are shown in Table 2. The extension of the bulk antenna of the PS I-core particles by the LHC I (∼50 Chls, not including the red Chls) and the gap Chls (∼10) contributes only ∼24% (2.3 ps) to the total increase (9.5 ps) of the τET, whereas the rest of the observed increase is due to the presence of the red Chls. Likewise the bulk antenna enlargement in the intact PS I contributes only 3.7 ps to the total increase of 20.7 ps in τCS. Our results thus argue against the conclusion of Engelmann and colleagues (26) proposing an equal influence of the bulk antenna enlargement and of the presence of red Chls on the total trapping. Our findings are, however, in relatively good agreement with the respective conclusion of Ihalainen and colleagues (25), suggesting a dominant effect of the red Chls on the increased trapping, despite the fact that we disagree with their proposed overall transfer-to-trap-limited type of kinetics (vide supra). In conclusion, the presence of the red Chls indeed substantially slows down the trapping kinetics in PS I. In this sense the red Chls might well function as centers for a photoprotective mechanism. However, a photoprotective function of the singlet states has not been demonstrated yet to our knowledge. The red Chls exert, however, a photoprotective function on the triplet states (33,34). On the other hand, the processes in the RC are slower than the total energy equilibration and rule the overall trap-limited kinetics. This allows the red Chls to also easily perform the function of a spectral extension of the antenna system. Apparently, both functions can coexist and can be modulated by the environmental conditions. The redox state of P700 may be the switch between these two functions.

TABLE 2.

Contribution of the bulk antenna enlargement and the presence of red Chls in PS I-intact particles in the slowing down of the overall trapping kinetics

| Excited compartment

|

Differences

|

Contributions (%)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(no REDs) (no REDs) |

|

(no REDs)- (no REDs)-

|

- -

|

Antenna enlargement | red Chls | |

| τavg (ps) | 12.9 | 18.9 | 43.1 | 6 | 30.2 | 20 | 80 |

| τET (ps) | 2.3 | 4.6 | 11.8 | 2.3 | 9.5 | 24 | 76 |

| τCS (ps) | 10.6 | 14.3 | 31.3 | 3.7 | 20.7 | 18 | 82 |

Scaling was performed as described in Table 1 and in the text. For the  (no REDs), case the calculation was performed without including the red Chl compartments (for more details, see text).

(no REDs), case the calculation was performed without including the red Chl compartments (for more details, see text).

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we have described the trapping kinetics in higher plant PS I-core and PS I-intact particles, determined the rate constants and the lifetimes of the energy and electron transfer processes, and resolved the spectra and kinetics of RC*, ANT*, and the red Chl compartments. In addition for the first time, to our knowledge, we have quantified the influence of the red Chls and the effects of the enlargement of the bulk antenna in intact PS I on the overall trapping kinetics and described the effect separately for the ET and CS lifetimes.

Our results show that no red Chls are present in the PS I-core particles from A. thaliana. The red-shifted fluorescence (∼700 nm) observed in the PS I-core preparations originates from the RC* itself. The trapping kinetics both in the core and in the intact particles from higher plant PS I falls into the trap-limited category, similarly to the one previously observed in algae PS I-cores (9,24). Due to the presence of red Chls and the larger antenna system in the intact PS I complex, the total trapping kinetics is slowed down approximately three times more than the core alone. Nevertheless, this effect is not large enough to switch the type of trapping to a diffusion- or transfer-to-trap-limited case. More than 80% of the slowing down of the trapping kinetics is caused by the red Chls. The two red Chl compartments differ in the type of their ET kinetics. Such a difference may be linked to differences in the function(s) these Chls perform in PS I.

In this study for the first time, to our knowledge, the two kinetically resolved red states in the intact PS I complexes have been attributed to the red states found in Lhca 3 and Lhca 4 (48). It is important here to comment on the general approach to describe and analyze the kinetics of such a complex system as the intact PS I particle by a compartment model with a small number of compartments. Clearly these compartment models are minimal in the sense that they provide only a description for the main components while leaving some details of the kinetics (and the associated spectra of the intermediate states) unexplained. However in the absence of a precise and detailed x-ray structure, there simply exists no better a priori possibility for resolving and describing the kinetics of such a complex system of ∼200 pigments. Thus the question is not whether these compartment models are minimal (they certainly are) but only whether they describe the actual situation well enough that i), they allow us to resolve and assign the main components correctly, and that ii), the results of the analysis allow us to draw major conclusions as to the type and properties of the kinetics.

Although we are aware that such compartment models cannot provide a fully precise description of the kinetics (including the associated spectra), we do claim that these models and the resulting lifetimes describe the actual situation astonishingly well. Thus we claim—and this claim is supported both by the results here and their excellent general agreement with our previous published studies on the simpler PS I-core particles—that the simple compartment models not only do an excellent job in describing the overall kinetics but also allow us to get important insights into the type of kinetics (diffusion- versus trap-limit, resolution of the kinetics and spectra of the RC* etc.).

Finally, the studies of the light energy utilization kinetics in natural photosynthetic complexes and in particular the properties of the red Chls, which both extend the spectral range and may also play a special role in photoprotection, provide valuable knowledge for the design and the development of artificial light-harvesting systems and systems for solar energy conversion.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marc G. Müller and Malwina Szczepaniak in our group for fruitful discussions.

The work was supported in part by the DFG Sonderforschungsbereich 663, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf and Max-Planck-Institut Mülheim a.d. Ruhr. The work was also supported in part by the Project “Samba per 2”, Regional Development Fund, Trento Region, Italy.

Editor: Janos K. Lanyi.

References

- 1.Ben-Shem, A., F. Frolow, and N. Nelson. 2003. Crystal structure of plant photosystem I. Nature. 426:630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amunts, A., O. Drory, and N. Nelson. 2007. The structure of a plant photosystem I supercomplex at 3.4 Å resolution. Nature. 447:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fromme, P., E. Schlodder, and S. Jansson. 2003. Structure and function of the antenna system in photosystem I. In Light-Harvesting Antennas in Photosynthesis. B. R. Green and W. W. Parson, editors. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 253–279.

- 4.Jordan, P., P. Fromme, H. T. Witt, O. Klukas, W. Saenger, and N. Krauss. 2001. Three-dimensional structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature. 411:909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beddard, G. S. 1998. Excitations and excitons in photosystem I. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A. 356:421–448. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang, M., A. Damjanovic, H. M. Vaswani, and G. R. Fleming. 2003. Energy transfer in photosystem I of cyanobacteria Synechococcus elongatus: model study with structure-based semi-empirical Hamiltonian and experimental spectral density. Biophys. J. 85:140–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croce, R., G. Zucchelli, F. M. Garlaschi, R. Bassi, and R. C. Jennings. 1996. Excited state equilibration in the photosystem I-light-harvesting I complex: P700 is almost isoenergetic with its antenna. Biochemistry. 35:8572–8579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibasiewicz, K., V. M. Ramesh, A. N. Melkozernov, S. Lin, N. W. Woodbury, R. E. Blankenship, and A. N. Webber. 2001. Excitation dynamics in the core antenna of PS I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii CC 2696 at room temperature. J. Phys. Chem. B. 105:11498–11506. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller, M. G., J. Niklas, W. Lubitz, and A. R. Holzwarth. 2003. Ultrafast transient absorption studies on photosystem I reaction centers from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. 1. A new interpretation of the energy trapping and early electron transfer steps in photosystem I. Biophys. J. 85:3899–3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holzwarth, A. R., M. G. Müller, J. Niklas, and W. Lubitz. 2006. Ultrafast transient absorption studies on photosystem I reaction centers from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. 2. Mutations around the P700 reaction center chlorophylls provide new insight into the nature of the primary electron donor. Biophys. J. 90:552–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibasiewicz, K., V. M. Ramesh, S. Lin, K. Redding, N. W. Woodbury, and A. N. Webber. 2003. Excitonic interactions in wild-type and mutant PSI reaction centers. Biophys. J. 85:2547–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart, D. H., A. Cua, D. F. Bocian, and G. W. Brudvig. 1999. Selective Raman scattering from the core chlorophylls in photosystem I via preresonant near-infrared excitation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 103:3758–3764. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibasiewicz, K., V. M. Ramesh, S. Lin, N. W. Woodbury, and A. N. Webber. 2002. Excitation dynamics in Eukaryotic PS I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii CC 2696 at 10 K. Direct detection of the reaction center exciton states. J. Phys. Chem. B. 106:6322–6330. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karapetyan, N. V., E. Schlodder, R. van Grondelle, and J. P. Dekker. 2006. The long-wavelength chlorophylls of photosystem I. In Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration: The Light-Driven, Plastocyanin:Ferredoxin Oxydoreductase. J. H. Golbeck, editor. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 177–192, CP9.

- 15.Byrdin, M., I. Rimke, E. Schlodder, D. Stehlik, and T. A. Roelofs. 2000. Decay kinetics and quantum yields of fluorescence in photosystem I from Synechococcus elongatus with P700 in the reduced and oxidized state: are the kinetics of excited state decay trap-limited or transfer-limited? Biophys. J. 79:992–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gobets, B., and R. van Grondelle. 2001. Energy transfer and trapping in photosystem I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1507:80–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gobets, B., I. H. M. van Stokkum, M. Rögner, J. Kruip, E. Schlodder, N. V. Karapetyan, J. P. Dekker, and R. van Grondelle. 2001. Time-resolved fluorescence emission measurements of photosystem I particles of various cyanobacteria: a unified compartmental model. Biophys. J. 81:407–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gobets, B., I. H. M. van Stokkum, F. van Mourik, J. P. Dekker, and R. van Grondelle. 2003. Excitation wavelength dependence of the fluorescence kinetics in photosystem I particles from Synechocystis PCC 6803 and Synechococcus elongatus. Biophys. J. 85:3883–3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

19.Savikhin, S., W. Xu, P. Martinsson, P. R. Chitnis, and W. S. Struve. 2001. Kinetics of charge separation and

electron transfer in photosystem I reaction centers. Biochemistry. 40:9282–9290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

electron transfer in photosystem I reaction centers. Biochemistry. 40:9282–9290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - 20.Croce, R., D. Dorra, A. R. Holzwarth, and R. C. Jennings. 2000. Fluorescence decay and spectral evolution in intact photosystem I of higher plants. Biochemistry. 39:6341–6348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holzwarth, A. R., G. H. Schatz, H. Brock, and E. Bittersmann. 1993. Energy transfer and charge separation kinetics in photosystem I: 1. Picosecond transient absorption and fluorescence study of cyanobacterial photosystem I particles. Biophys. J. 64:1813–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melkozernov, A. N., S. Lin, and R. E. Blankenship. 2000. Excitation dynamics and heterogeneity of energy equilibration in the core antenna of photosystem I from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochemistry. 39:1489–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savikhin, S., W. Xu, V. Soukoulis, P. R. Chitnis, and W. S. Struve. 1999. Ultrafast primary processes in photosystem I of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. Biophys. J. 76:3278–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holzwarth, A. R., M. G. Müller, J. Niklas, and W. Lubitz. 2005. Charge recombination fluorescence in photosystem I reaction centers from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Phys. Chem. B. 109:5903–5911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ihalainen, J. A., I. H. M. van Stokkum, K. Gibasiewicz, M. Germano, R. van Grondelle, and J. P. Dekker. 2005. Kinetics of excitation trapping in intact photosystem I of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1706:267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engelmann, E., G. Zucchelli, A. P. Casazza, D. Brogioli, F. M. Garlaschi, and R. C. Jennings. 2006. Influence of the photosystem I–light harvesting complex I antenna domains on fluorescence decay. Biochemistry. 45:6947–6955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melkozernov, A. N., J. Kargul, S. Lin, J. Barber, and R. E. Blankenship. 2004. Energy coupling in the PSI-LHCI supercomplex from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Phys. Chem. B. 108:10547–10555. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trissl, H.-W. 1993. Long-wavelength absorbing antenna pigments and heterogeneous absorption bands concentrate excitons and increase absorption cross section. Photosynth. Res. 35:247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karapetyan, N. V., A. R. Holzwarth, and M. Rögner. 1999. The photosystem I trimer of cyanobacteria: molecular organisation, excitation dynamics and physiological significance. FEBS Lett. 460:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rivadossi, A., G. Zucchelli, F. M. Garlaschi, and R. C. Jennings. 1999. The importance of PSI chlorophyll red forms in light-harvesting by leaves. Photosynth. Res. 60:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melkozernov, A. N., and R. E. Blankenship. 2005. Structural and functional organization of the peripheral light-harvesting system in photosystem I. Photosynth. Res. 85:33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karapetyan, N. V. 2004. The dynamics of excitation energy in photosystem I of cyanobacteria: transfer in the antenna, capture by the reaction site, and dissipation. Biophysics. 49:196–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carbonera, D., G. Agostini, T. Morosinotto, and R. Bassi. 2005. Quenching of chlorophyll triplet states by carotenoids in reconstituted Lhca4 subunit of peripheral light-harvesting complex of photosystem I. Biochemistry. 44:8337–8346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Croce, R., M. Mozzo, T. Morosinotto, A. Romeo, R. Hienerwadel, and R. Bassi. 2007. Singlet and triplet state transitions of carotenoids in the antenna complexes of higher-plant photosystem I. Biochemistry. 46:3846–3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palsson, L.-O., J. P. Dekker, E. Schlodder, R. Monshouwer, and R. van Grondelle. 1996. Polarized site-selective fluorescence spectroscopy of the long- wavelength emitting chlorophylls in isolated photosystem I particles of Synechococcus elongatus. Photosynth. Res. 48:239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zazubovich, V., S. Matsuzaki, T. W. Johnson, J. M. Hayes, P. R. Chitnis, and G. J. Small. 2002. Red antenna states of photosystem I from cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus: a spectral hole burning study. Chem. Phys. 275:47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rätsep, M., T. W. Johnson, P. R. Chitnis, and G. J. Small. 2000. The red-absorbing chlorophyll a antenna states of photosystem. I: A hole-burning study of Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 and its mutants. J. Phys. Chem. B. 104:836–847. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jelezko, F., C. Tietz, U. Gerken, J. Wrachtrup, and R. Bittl. 2000. Single-molecule spectroscopy on photosystem I pigment-protein complexes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 104:8093–8096. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ihalainen, J. A., M. Rätsep, P. E. Jensen, H. V. Scheller, R. Croce, R. Bassi, J. E. I. Korppi-Tommola, and A. Freiberg. 2003. Red spectral forms of chlorophylls in green plant PSI—a site-selective and high-pressure spectroscopy study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 107:9086–9093. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melkozernov, A. N., S. Lin, and R. E. Blankenship. 2000. Femtosecond transient spectroscopy and excitonic interactions in photosystem I. J. Phys. Chem. B. 104:1651–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palsson, L.-O., C. Flemming, B. Gobets, R. van Grondelle, J. P. Dekker, and E. Schlodder. 1998. Energy transfer and charge separation in photosystem I P700 oxidation upon selective excitation of the long-wavelength antenna chlorophylls of Synechococcus elongatus. Biophys. J. 74:2611–2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mullet, J. E., J. J. Burke, and C. J. Arntzen. 1980. Chlorophyll proteins of photosystem I. Plant Physiol. 65:814–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Croce, R., G. Zucchelli, F. M. Garlaschi, and R. C. Jennings. 1998. A thermal broadening study of the antenna chlorophylls in PSI- 200, LHCI, and PSI core. Biochemistry. 37:17355–17360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jennings, R. C., G. Zucchelli, E. Engelmann, and F. M. Garlaschi. 2004. The long-wavelength chlorophyll states of plant LHCI at room temperature: a comparison with PSI-LHCI. Biophys. J. 87:488–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Melkozernov, A. N., J. Kargul, S. Lin, J. Barber, and R. E. Blankenship. 2005. Spectral and kinetic analysis of the energy coupling in the PSI-LHC I supercomplex from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii at 77 K. Photosynth. Res. 86:203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morosinotto, T., M. Ballottari, F. Klimmek, S. Jansson, and R. Bassi. 2005. The association of the antenna system to photosystem I in higher plants. J. Biol. Chem. 280:31050–31058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castelletti, S., T. Morosinotto, B. Robert, S. Caffarri, R. Bassi, and R. Croce. 2003. Recombinant Lhca2 and Lhca3 subunits of the photosystem I antenna system. Biochemistry. 42:4226–4234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morosinotto, T., J. Breton, R. Bassi, and R. Croce. 2003. The nature of a chlorophyll ligand in Lhca proteins determines the far red fluorescence emission typical of photosystem I. J. Biol. Chem. 278:49223–49229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hastings, G., F. A. M. Kleinherenbrink, S. Lin, and R. E. Blankenship. 1994. Time-resolved fluorescence and absorption spectroscopy of photosystem I. Biochemistry. 33:3185–3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turconi, S., J. Kruip, G. Schweitzer, M. Rögner, and A. R. Holzwarth. 1996. A comparative fluorescence kinetics study of photosystem I monomers and trimers from Synechocystis PCC 6803. Photosynth. Res. 49:263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karapetyan, N. V., D. Dorra, G. Schweitzer, I. N. Bezsmertnaya, and A. R. Holzwarth. 1997. Fluorescence spectroscopy of the longwave chlorophylls in trimeric and monomeric photosystem I core complexes from the cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis. Biochemistry. 36:13830–13837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gobets, B., J. T. M. Kennis, J. A. Ihalainen, M. Brazzoli, R. Croce, I. H. M. van Stokkum, R. Bassi, J. P. Dekker, H. van Amerongen, G. R. Fleming, and R. van Grondelle. 2001. Excitation energy transfer in dimeric light harvesting complex I: a combined streak-camera/fluorescence upconversion study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 105:10132–10139. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ihalainen, J. A., R. Croce, T. Morosinotto, I. H. M. van Stokkum, R. Bassi, J. P. Dekker, and R. van Grondelle. 2005. Excitation decay pathways of Lhca proteins: a time-resolved fluorescence study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 109:21150–21158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koehne, B., and H.-W. Trissl. 1998. The cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis contains a long wavelength absorbing pigment C738(F760/77K) at room temperature. Biochemistry. 37:5494–5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bassi, R., G. M. Giacometti, and D. J. Simpson. 1988. Changes in the organization of stroma membranes induced by in vivo state 1-state 2 transition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 935:152–165. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holzwarth, A. R. 1996. Data analysis of time-resolved measurements. In Biophysical Techniques in Photosynthesis. Advances in Photosynthesis Research. J. Amesz and A. J. Hoff, editors. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 75–92.

- 57.van Stokkum, I. H. M., D. S. Larsen, and R. van Grondelle. 2004. Global and target analysis of time-resolved spectra. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1657:82–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turconi, S., N. Weber, G. Schweitzer, H. Strotmann, and A. R. Holzwarth. 1994. Energy transfer and charge separation kinetics in photosystem I. 2. Picosecond fluorescence study of various PSI particles and light-harvesting complex isolated from higher plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1187:324–334. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holzwarth, A. R. 2004. Light absorption and harvesting. In Molecular to Global Photosynthesis. M. D. Archer and J. Barber, editors. Imperial College Press, London. 43–115.

- 60.Gobets, B., H. van Amerongen, R. Monshouwer, J. Kruip, M. Rögner, R. van Grondelle, and J. P. Dekker. 1994. Polarized site-selected fluorescence spectroscopy of isolated photosystem I particles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1188:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kennard, E. H. 1918. On the thermodynamics of fluorescence. Phys. Rev. 11:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stepanov, B. I. 1957. A universal relation between the absorption and luminescence spectra of complex molecules. Dokl. Akad. Nauk. SSSR. 112:839–841. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ihalainen, J. A., B. Gobets, K. Sznee, M. Brazzoli, R. Croce, R. Bassi, R. van Grondelle, J. E. I. Korppi-Tommola, and J. P. Dekker. 2000. Evidence for two spectroscopically different dimers of light-harvesting complex I from green plants. Biochemistry. 39:8625–8631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holzwarth, A. R., M. G. Müller, C. Slavov, R. Luthra, and K. Redding. 2007. Ultrafast energy and electron transfer in photosystem I. Direct evidence for two-branched electron transfer. In Ultrafast Phenomena XV. P. B. Corkum, D. Jonas, R. J. D. Miller, and A. M. Weiner, editors. 471–473.

- 65.van Grondelle, R., and B. Gobets. 2004. Transfer and trapping of excitations in plant photosystems. In Chlorophyll a Fluorescence: A Signature of Photosynthesis. G. C. Papageorgiou and Govindjee, editors. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 107–132.

- 66.Miloslavina, Y., M. Szczepaniak, M. G. Müller, J. Sander, M. Nowaczyk, M. Rögner, and A. R. Holzwarth. 2006. Charge separation kinetics in intact photosystem II core particles is trap-limited. A picosecond fluorescence study. Biochemistry. 45:2436–2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sener, M. K., C. Jolley, A. Ben-Shem, P. Fromme, N. Nelson, R. Croce, and K. Schulten. 2005. Comparison of the light-harvesting networks of plant and cyanobacterial photosystem I. Biophys. J. 89:1630–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu, Z., H. Yan, K. Wang, T. Kuang, J. Zhang, L. Gui, X. An, and W. Chang. 2004. Crystal structure of spinach major light-harvesting complex at 2.72 angstrom resolution. Nature. 428:287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]