Abstract

A key aspect of human behavior is cooperation1-7. We tend to help others even if costs are involved. We are more likely to help when the costs are small and the benefits for the other person significant. Cooperation leads to a tension between what is best for the individual and what is best for the group. A group does better if everyone cooperates, but each individual is tempted to defect. Recently, there has been much interest to explore the effect of costly punishment on human cooperation8-23. Costly punishment means paying a cost for another individual to incur a cost. It has been suggested that costly punishment promotes cooperation even in non-repeated games and without any possibility of reputation effects10. But most of our interactions are repeated and reputation is always at stake. Thus, if costly punishment plays an important role in promoting cooperation, it must do so in a repeated setting. We have performed experiments where in each round of a repeated game people choose between cooperation, defection and costly punishment. In control experiments, people can only cooperate or defect. We find that the option of costly punishment increases the amount of cooperation, but not the average payoff of the group. Furthermore, there is a strong negative correlation between total payoff and use of costly punishment. Those people who gain the highest total payoff tend not to use costly punishment: winners don’t punish. This suggests that costly punishment behavior is maladaptive in cooperation games and might have evolved for other reasons.

The essence of cooperation is described by the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Two players have a choice between cooperation, C, and defection, D. If both players cooperate they get more than if both defect, but defecting against a cooperator leads to the highest payoff, while cooperating with a defector leads to the lowest payoff. One way to construct a Prisoner’s Dilemma is by assuming that cooperation implies paying a cost for the other person to receive a benefit, while defection implies taking something away from the other person (Fig 1).

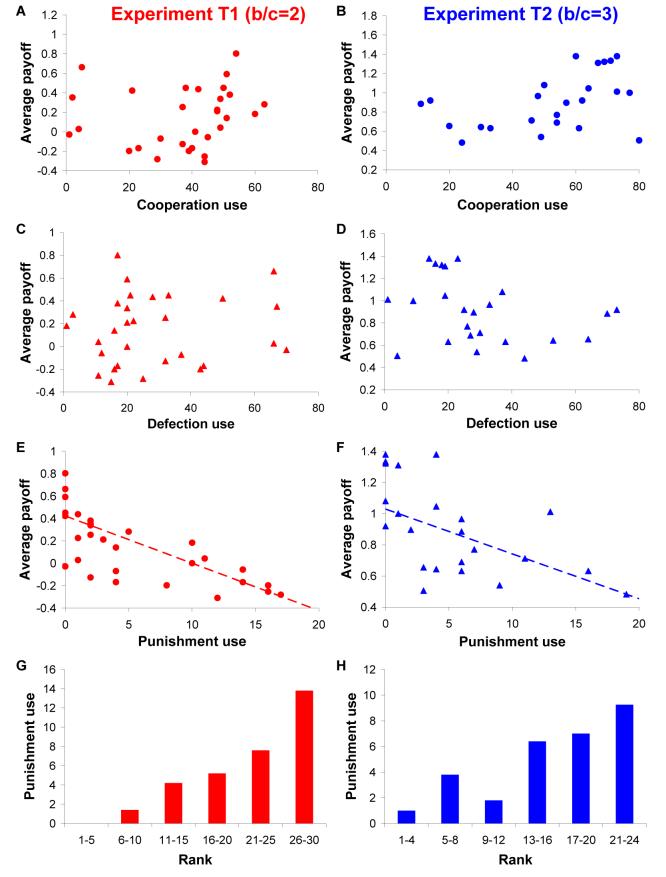

Figure 1. Payoff values.

A: The game is formulated in terms of unilateral moves. There is the choice between cooperation, C, defection, D, and costly punishment, P. Cooperation means paying a cost, c, for the other person to get a benefit, b. Defection means earning a payoff, d, at a cost, d, for the other person. Punishment means paying a cost, α, for the other person to incur a cost, β. B: The payoff matrix is constructed from these unilateral moves. C and D: The actual payoff matrices of our experiments.

Without any mechanism for the evolution of cooperation, natural selection favors defection. But a number of such mechanisms have been proposed, including direct and indirect reciprocity7. Direct reciprocity means there are repeated encounters between the same two individuals, and my behavior depends on what you have done to me 1-6. Indirect reciprocity means there are repeated encounters within a group; my behavior also depends on what you have done to others.

Costly (or altruistic) punishment, P, means that one person pays a cost for another person to incur a cost. People are willing to use costly punishment against others who have defected8-18. Costly punishment is not a mechanism for the evolution of cooperation7, but requires a mechanism for its evolution19-23. Like the idea of reputation effects24, costly punishment is a form of direct or indirect reciprocity. If I punish you because you have defected against me, direct reciprocity is used. If I punish you because you have defected with others, indirect reciprocity is at work. The concept of costly punishment suggests that the basic game should be extended from two possible behaviors (C and D) to three (C, D and P). Here we investigate the consequences of this extension for the repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma.

104 subjects participated in repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma experiments at the Harvard Business School Computer Lab for Experimental Research. Participants interacted anonymously in pair-wise encounters via computer screens. Subjects did not know how long each interaction would last, but knew that the probability of another round was 0.75 (as in Ref. 25). In any given round, the subjects chose simultaneously between all available options, which were presented in a neutral language. After each round, the subjects were shown the other person’s choice as well as both payoff scores. At the end of the interaction, the participants were presented with the final scores and then randomly re-matched for another interaction.

We have performed two control experiments (C1 and C2) and two treatments (T1 and T2). In the control experiments, people played a standard repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma. In each round they could either cooperate or defect. Cooperation meant paying 1 unit for the other person to receive 2 units (in C1 and T1) or 3 units (in C2 and T2). Defection meant gaining 1 unit at a cost of 1 for the other person. In the treatments, people had three options in every round: cooperate, defect or punish. Punishment meant paying 1 unit for the other person to lose 4. We used a 4:1 punishment technology because it has been shown to be more effective in promoting cooperation than other ratios13. The resulting payoff matrices are shown in Figure 1. See Supplementary Information for more details.

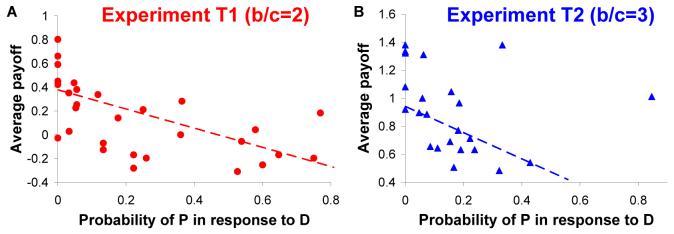

Figure 2 shows some examples of games that occurred in the treatments T1 and T2. A number of games were all-out cooperation. Sometimes cooperation could be maintained by forgiving an opponent’s defection. At other times, defection in response to defection was able to restore cooperation. Typically, costly punishment did not re-establish cooperation. In some cases, costly punishment provoked counter-punishment, thereby assuring mutual destruction. Giving people the option of costly punishment can also lead to unprovoked first strikes with disastrous consequences.

Figure 2. Games people played.

There were 1230 pair-wise, repeated interactions each lasting between 1 and 9 rounds. Here are some examples (B, E and G are from T1, the others from T2.) The two players’ moves, the cumulative payoff of that interaction and the final rank of each player (sorted from highest to lowest payoff) are shown. A: All-out cooperation between two top-ranked players. B: Punish and perish. C: Defection for defection can sometimes restore cooperation. D: Turning the other cheek can also restore cooperation. E: Mutual punishment is mutual destruction. F: Punishment does not restore cooperation. Player 1 punishes a defection, which leads to mutual defection. Then player 1 is unsatisfied and deals out more punishment. G: “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people”. (Punishment itself is not destructive, only the people who use it.) Here, an unprovoked first strike destroys cooperation. The option to punish allows irrational people to inflict harm on the undeserving.

Comparing the two control experiments, C1 and C2, we find that the frequency of cooperation increases as the benefit to cost ratio increases. In C1, 21.2% of decisions are cooperation, compared to 43.0% in C2. For both parameter choices, cooperation is a subgame perfect equilibrium. Comparing each control experiment with its corresponding treatment, we find that punishment increases the frequency of cooperation. In T1 and T2, 52.4% and 59.7% of all decisions are cooperation.

Punishment, however, does not increase the average payoff. In T1 and T2, we observe that 7.6% and 5.8% of decisions are punishment, P. We find no significant difference in the average payoff when comparing C1 with T1 and C2 with T2. Therefore, punishment has no benefit for the group, which makes it hard to argue that punishment might have evolved by group selection22.

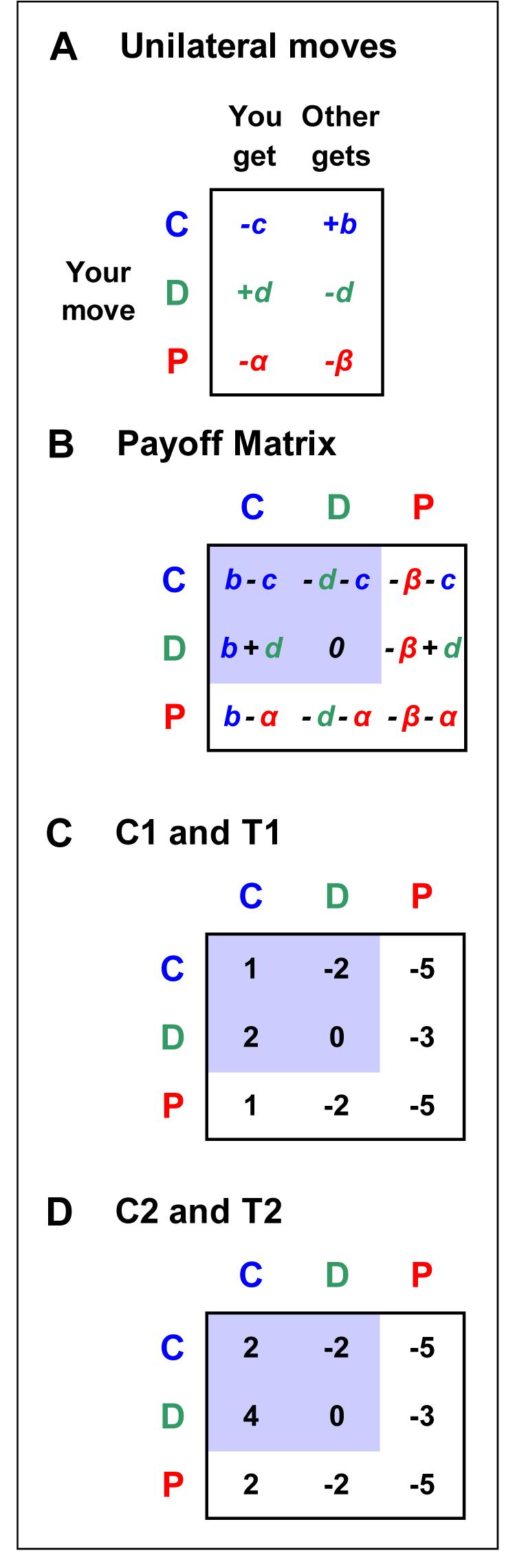

Examining the data of experiments T1 and T2 on the individual level, we find no correlation between the use of cooperation or defection and payoff, but a strong negative correlation between the use of punishment and payoff (Fig 3). In experiment T1, the five top ranked players, who earned the highest total payoff, have never used costly punishment. In both experiments, the players who end up with the lowest payoff tend to punish most often. Hence, for maximizing the overall income it is best never to punish: winners don’t punish (Fig 3).

Figure 3. Punish and perish.

In both treatments T1 (red) and T2 (blue), there is no correlation between average payoff per round and (i) cooperation use (Quantile regression; A, p = 0.33; B, p = 0.21) or (ii) defection use (C, p = 0.66; D, p = 0.36). However, there is a significant negative correlation between average payoff per round and punishment use in both treatments (E, slope = -0.042, p < 0.001; F, slope = -0.029, p = 0.015). Punishment use is the overriding determinant of payoff. G and H: Ranking players according to their total payoff shows a clear trend: players with lower rank (higher payoffs) punish less than players with higher rank (lower payoff).

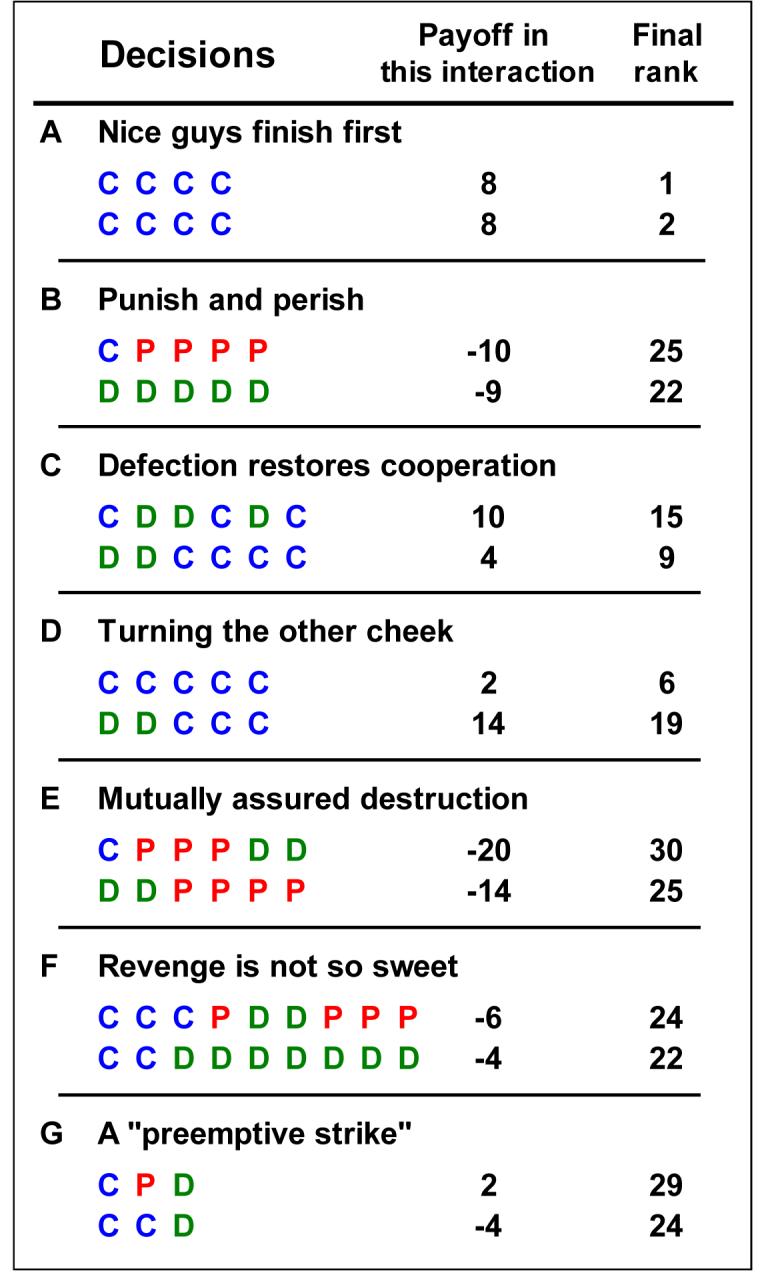

It could be the case that the winners of our experiment were merely lucky in that they were paired with people against whom punishment was not necessary. In order to test this hypothesis, we analyzed the correlation between payoff and the first order conditional strategies used by people. Figure 4 illustrates a strong negative correlation between payoff and the probability to use punishment, P, after the opponent has defected, D. Winners tend to respond by using D against D, while losers use P against D. The response to another person’s defection is the only strategic feature which is clearly correlated with winning or losing the game. Winners play a tit-for-tat like strategy2,4, while losers use costly punishment.

Figure 4. Tit-for-tat prevails over costly punishment.

Lower payoffs are correlated not only with punishment use, but specifically with choosing to punish after the opponent has defected. The probability of punishing immediately after a co-player’s defection is negatively correlated with the average payoff per round, both in T1 and T2 (Quantile regression; A, slope = -0.81, p < 0.001; B, slope = -0.94, p = 0.015). Thus, the lower payoffs of punishers were not caused by the bad luck of interacting with defectors. Winners use a tit-for-tat like approach (D for D), while losers use costly punishment (P for D).

It could be that using costly punishment becomes more beneficial as the game progresses. In order to test this possibility, we have separately analyzed the data from the last ¼ of all interactions. Again, it remains true that there is a strong negative correlation between an individual’s payoff and his use of costly punishment.

In previous experiments, punishment was usually offered as a separate option following one or several rounds of a public goods game. The public goods game is a multi-person Prisoner’s Dilemma, where each player can invest a certain sum into a common pool, which is then multiplied by a factor and equally divided among all players irrespective of whether they have invested or not26. After the public goods game, people are asked if they want to pay money for others to lose money. People are willing to use this option in order to punish those who have invested nothing or only very little, and the presence of this option has been found to increase contributions8,10.

Careful analysis, however, has revealed that in most cases, punishment does not increase the average payoff. In some experiments, punishment reduces the average payoff 9,10,12,27, while in others it does not lead to a significant change11,14,15. Only once has punishment been found to increase the average payoff 13. The higher frequency of cooperation is usually offset by the cost of punishment, which affects both the punisher and the punished. Our findings are in agreement with this observation: the option of costly punishment does not increase the average payoff of the group. It is possible, however, that in longer experiments and for particular parameter values punishment might increase the average payoff.

It is sometimes argued that costly punishment is a mechanism for stabilizing cooperation in anonymous, one-shot games. But whether or not this is the case seems to be of little importance, because most of our interactions occur in a context where repetition is possible and reputation matters. For millions of years of human evolution, our ancestors have lived in relatively small groups where people knew each other. Interactions in such groups are certainly repeated and open ended. Thus, our strategic instincts have been evolving in situations where it is likely that others either directly observe my actions or eventually find out about them. Also in modern life, most of our interactions occur with people whom we meet frequently. Typically, we can never rule out ‘subsequent rounds’. Therefore, if costly punishment is important for the evolution of human cooperation, then it must play a beneficial role in the setting of repeated games. Our findings do not support this claim.

We also believe that our current design has some additional advantages over previous ones. In our setting, costly punishment is always one of three options. Hence, there is an opportunity cost for using punishment, because the subject forfeits the opportunity to cooperate or to defect. Our design also minimizes the experimenter and participant demand effects28, because there are always several options 27. In many previous experiments retaliation for punishment is not possible 9-16,27, but it is a natural feature of our setting.

In summary, our data show that costly punishment strongly disfavors the individual who uses it and hence it is opposed by individual selection in cooperation games where direct reciprocity is possible. We conclude that costly punishment might have evolved for reasons other than promoting cooperation, such as coercing individuals into submission and establishing dominance hierarchies20,29. Punishment might enable a group to exert control over individual behavior. A stronger individual could use punishment to dominate weaker ones. People engage in conflicts and know that conflicts can carry costs. Costly punishment serves to escalate conflicts, not to moderate them. Costly punishment might force people to submit, but not to cooperate. It could be that costly punishment is beneficial in these other games, but the use of costly punishment in games of cooperation appears to be maladaptive. We have shown that in the framework of direct reciprocity, winners do not use costly punishment, while losers punish and perish.

Methods summary

A total of 104 subjects (45 women, 59 men, mean age 22.2) from Boston area colleges and universities participated voluntarily in a modified repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma game at the Harvard Business School Computer Lab for Experimental Research (CLER). The lab consists of 36 computers which are visually partitioned. The participants interacted anonymously via the software z-Tree30. The subjects were from a number of different schools and a wide range of fields of study, such that it was unlikely for any subject to know more than one other person in the room. No significant difference in cooperation use, punishment use or payoff was found between males and females, or between economics majors and non-economic majors (Mann-Whitney test: p > 0.05 for all sessions). Subjects were not allowed to participate in more than one session of the experiment. A total of 4 sessions were conducted in April and May 2007, with an average of 26 participants playing an average of 24 interactions, for an average of 79 total rounds per subject. At the start of each new interaction, subjects were unaware of the previous decisions of the other player. After each round, the subjects were shown the other person’s choice as well as both payoff scores. At the end of the interaction, the participants were presented with the final scores and then randomly re-matched for another interaction.

In each session, the subjects were paid a $15 show up fee. Each subject’s final score summed over all interactions was multiplied by $0.10 to determine additional earned income. To allow for negative incomes while maintaining the $15 show up fee, $5 was added to each subject’s earned income at the end of the session. Subjects were informed of this extra $5 at the beginning of the session. The average payment per subject was $26 and the average session length was 1.25 hours.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Support from the John Templeton Foundation, the NSF-NIH joint program in mathematical biology (NIH grant 1R01GM078986), the Jan Wallander Foundation (A.D) and NSF grant SES 0646816 (DF) is gratefully acknowledged. The Program for Evolutionary Dynamics is sponsored by J. Epstein.

References

- 1.Trivers R. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q. Rev. Biol. 1971;46:35–57. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Axelrod R, Hamilton WD. The evolution of cooperation. Science. 1981;211:1390–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.7466396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fudenberg D, Maskin E. Evolution and cooperation in noisy repeated games. Am. Econ. Rev. 1990;80:274–279. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Tit for tat in heterogeneous populations. Nature. 1992;355:250–253. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binmore K, Samuelson L. Evolutionary stability in repeated games played by finite automata. J. of Econ. Theory. 1992;57:278–305. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colman AM. Game Theory and its Applications in the Social and Biological Sciences. Routledge, New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nowak MA. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science. 2006;314:1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1133755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamagishi T. The provision of a sanctioning system as a public good. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986;51:110–116. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostrom E, Walker J, Gardner R. Covenants with and without a sword: self-governance is possible. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 1992;86:404–417. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fehr E, Gächter S. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature. 2002;415:137–140. doi: 10.1038/415137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botelho A, Harrison GW, Pinto LMC, Rutström EE. University of Central Florida Economics Working Paper No. 05-23. 2005. Social norms and social choice. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egas M, Riedl A. IZA Discussion Papers No. 1646. 2005. The economics of altruistic punishment and the demise of cooperation. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikiforakis N, Normann HT. Royal Holloway University of London Discussion Paper in Economics No. 05/07. 2005. A comparative statics analysis of punishment in public-good experiments. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page T, Putterman L, Unel B. Voluntary association in public goods experiments: reciprocity, mimicry and efficiency. Econ. J. 2005;115:1032–1053. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bochet O, Page T, Putterman L. Communication and punishment in voluntary contribution experiments. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2006;60:11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gürerk Ö, Irlenbusch B, Rockenbach B. The competitive advantage of sanctioning institutions. Science. 2006;312:108–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1123633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rockenbach B, Milinski M. The efficient interaction of indirect reciprocity and costly punishment. Nature. 2006;444:718–723. doi: 10.1038/nature05229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denant-Boemont L, Masclet D, Noussair CN. Punishment, counterpunishment and sanction enforcement in a social dilemma experiment. Econ. Theory. 2007;33:145–167. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. Punishment allows the evolution of cooperation (or anything else) in sizable groups. Ethology and Sociobiology. 1992;13:171–195. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clutton-Brock TH, Parker GA. Punishment in animal societies. Nature. 1995;373:209–216. doi: 10.1038/373209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sigmund K, Hauert C, Nowak MA. Reward and punishment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10757–10762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161155698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyd R, Gintis H, Bowles S, Richerson PJ. The evolution of altruistic punishment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:3531–3535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630443100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fowler JH. Altruistic punishment and the origin of cooperation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7047–7049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500938102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fudenberg D. In: Advances in Economic Theory: Sixth World Congress. Laffont JJ, editor. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1993. pp. 89–131. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dal Bó P. Cooperation under the shadow of the future: experimental evidence from infinitely repeated games. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005;95:1591–1604. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardin G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science. 1968;162:1243–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sefton M, Shupp R, Walker JM. Indiana University Bloomington Economics CAEPR Working Paper No. 2006-005. 2006. The Effect of Rewards and Sanctions in Provision of Public Goods. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carpenter J, Liati A, Vickery B. Middlebury College Economics Discussion Paper No. 06-02. 2006. They come to play: supply effects in an economic experiment. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samuelson L. Economic theory and experimental economics. J. of Econ. Lit. 2005;43:65–107. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischbacher U. z-Tree: Zurich Toolbox for Ready-made Economic Experiments. Experimental Economics. 2007;10:171–178. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.