SUMMARY

The Escherichia coli protein Fis is remarkable for its ability to interact specifically with DNA sites of highly variable sequences. The mechanism of this sequence-flexible DNA recognition is not well understood. In a previous study, we examined the contributions of Fis residues to high-affinity binding at different DNA sequences using alanine-scanning mutagenesis and identified several key residues for Fis-DNA recognition. In this work, we investigated the contributions of the 15 bp core Fis binding sequence and its flanking regions to the Fis-DNA interactions. Systematic base pair replacements made in both half sites of a palindromic Fis binding sequence were examined for their effects on the relative Fis binding affinity. Missing contact assays were also used to examine the effects of base removal within the core binding site and its flanking regions on the Fis-DNA binding affinity. The results revealed that 1) the -7G and +3Y bases in both DNA strands (relative to the central position of the core binding site) are major determinants for high-affinity binding, 2) the C5 methyl group of thymine, when present at the +4 position, strongly hinders Fis binding, and 3) an AT-rich sequence in the central and flanking DNA regions facilitate Fis-DNA interactions by altering the DNA structure and increasing local DNA flexibility. We infer that the degeneracy of specific Fis binding sites results from the numerous base pair combinations that are possible at the non-critical DNA positions from -6 to -4, -2 to +2, and +4 to +6 with only moderate penalties on the binding affinity, the roughly similar contributions of -3A or G and +3T or C to the binding affinity, and the minimal requirement of three of the four critical base pairs to achieve considerably high binding affinities.

Keywords: Fis, nucleoid associated protein, DNA binding, DNA bending, missing contact

INTRODUCTION

Fis is a nucleoid-associated protein found in the γ and β subdivisions of proteobacteria, which include the Enterobacteriales, Pasteurellaceae, Pseudomonaceae, Vibrionaceae, Xanthomonadaceae, Burkholderiaceae, and Neisseriaceae.1; 2; 3; 4 Fis participates in a wide array of cellular activities such as modulating DNA topology during growth,5; 6 regulating certain site specific DNA recombination events,7; 8; 9; 10; 11; 12 and regulating the transcription of a large number of genes during different stages of growth,13; 14; 15; 16 including rRNA and tRNA genes and genes involved in virulence and biofilm formation.17; 18; 19; 20; 21; 22; 23 Most of these functions depend on the ability of Fis to interact with DNA at specific sites. Nevertheless, specific Fis-DNA binding occurs at a number of poorly-related DNA sequences7 and this is reflected in the degeneracy of several consensus sequences proposed.7; 24; 25 For instance, Fis shows similarly strong DNA binding affinities (Kd ∼ 2 nM) to DNA sequences involved in Hin-mediated DNA inversion (GGTCACAATTTGCAC), phage λ DNA excision (GCATAAAAAACAGAC), and fis promoter autoregulation (GGCCAAACTTTGACC),26; 27 yet there are only 4 positions (underlined) having common nucleotides in all three sequences. It is not well understood how such tight binding affinity occurs at poorly conserved sequences.

There are currently no co-crystal or NMR structures of Fis-DNA complexes in the literature that demonstrate how Fis interacts with a specific DNA sequence. There have been various X-ray crystallographic studies showing that Fis forms a homodimer.28; 29; 30; 31 Each subunit consisting of 98 residues forms a disordered or flexible N-terminal region followed by four α-helices (α-A, α-B, α-C, and α-D) that are separated by short turns (Fig. 1). The C-terminal region forms a helix-turn helix DNA binding motif (HTH) that is replete with basic residues and required for DNA binding and bending 27; 32; 33. This HTH region is strongly conserved, suggesting that the DNA binding properties of Fis are also conserved.2; 32; 33 Several residues located in the α-D helix (R85, T87, and K90) are commonly required for specific DNA recognition of different sequences, while several other residues in the HTH region (e.g. N73, T75, R76, N84, R89, K91, and K93) make variable contributions to the binding affinity at different sequences.27 Hence, a minimal set of common Fis-DNA interactions occur at different DNA binding sites whereas other interactions are essential only in a subset of Fis-binding sequences. Thus, knowledge of the structures of Fis-DNA complexes at different DNA sequences will be required for a good understanding of the plasticity of Fis-DNA interactions.

Figure 1.

The Fis protein structure. (a) Ribbon model representation of the homodimer crystal structure from residues 26 to 98 (Protein Data Bank accession 3FIS). Residues 1-25 are largely unresolved in this structure. The four α-helices (α-A, α-B, α-C, and α-D) of one Fis subunit are labeled in order from the N-terminal to the C-terminal region. (b) Enlarged view of the region containing helices α-B, α-C and α-D in one Fis subunit. The HTH DNA binding motif consists of helices α-C and α-D. The side chains of the five most important Fis residues involved in DNA binding are shown. Residues R85, T87, and K90 (labeled in magenta) are absolutely required for Fis binding to different Fis binding sites, whereas residues R89 and K91 (labeled in green) make variable contributions to the binding affinity at different binding sites.27 Images were generated using Swiss-PDB viewer v. 3.9b2.

In this work, we investigated the DNA sequence contributions to the Fis binding affinity using two general kinds of approaches: a systematic base substitution analysis and a random base removal analysis (missing contact assay). These approaches yielded complementary results, which together, provided a more complete picture of the various DNA determinants comprising a functional Fis binding site.

RESULTS

DNA base pair contributions to the Fis binding affinity

A preliminary analysis of the relative Fis binding affinities to nine naturally-occurring binding sites, using the gel electrophoretic mobility shift assay (GEMSA), gave us a range of Kd values from about 2 to 55 nM (not shown). By aligning the half-esites of the five best binding sites in our collection (having Kd values below 5 nM) we obtained the symmetrical consensus sequence GNTYAAAWTTTRANC (Y = pyrimidine, R = purine, W = A or T, and N = any nucleotide). Guided by this sequence for high affinity binding sites, we generated a 43 bp DNA fragment with the 15 bp central sequence GCTCAAATTTTGAGC (Sequence 1) and found that the apparent Kd for Fis binding to this sequence was about 0.9 nM (Table 1). We then asked how the nucleotides at each position of this sequence contributed to the high Fis binding affinity. To address this, we generated another 27 DNA fragments varying from Sequence 1 at symmetrical positions in each half site and determined the effects of the nucleotide substitutions on the relative Fis binding affinities (Table 1). In order to facilitate referencing, these positions were numbered -7 to +7 in the 5′ to 3′ direction with the central position numbered 0. The GEMSA data from three representative DNA sequences and their corresponding DNA binding plots based on triplicate assays are shown as examples (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Relative Fis binding affinities to various related DNA sequences

|

The Fis-DNA binding sequences are shown from left to right in the 5′ to 3′ direction for one DNA strand. The core Fis binding sequences are underlined. The nucleotide positions are numbered relative to the central nucleotide in each Fis binding site. Bold letters represent the altered nucleotides relative to Sequence 1.

The Kd values are an average ± standard deviations from at least three gel electrophoretic mobility shift assays similar to those shown in Fig. 2.

Accurate determination of Kd values was not possible for these DNA fragments, but well over 2000 nM Fis was required to reach 50% binding.

The fold change in binding affinities are shown relative to that of Sequence 1, which was assigned a value of 1.

Figure 2.

Determination of relative Fis binding affinities. (a) Representative gel mobility shift assay results are shown for 32P-end labeled 43 bp DNA fragments containing Sequence 1, Sequence 7 (-6C→G / +6G→C) and Sequence 24 (-2 CCGGG +2). The positions of the free and bound DNA are indicated on the left of the gel image and the Fis concentrations are indicated beneath the lanes. (b) The results of triplicate binding assays for Sequence 1, 7, and 24 were fitted with Kaleidagraph v.3.5 using the equation Y = ([Fis]/([Fis] + Kd))*(M), where Y is the percent bound DNA and M is the maximal DNA binding defined by the curve fit (R2 > 0.95). The dissociation constant (Kd) was obtained as the Fis concentration required to achieve 50% of the maximal binding. Kd values from triplicate assays were similarly obtained for DNA fragments shown in Table 1 and expressed as an average ± standard deviation.

The results showed that the nucleotide combination -7G/+7C was critical for Fis binding (Table 1, Sequences 1-4). Any of the other three symmetrical substitutions at these positions elevated the Kd >2000-fold to within a μM range, which is characteristic of non-specific Fis-DNA binding in these assays.27 The -6T/+6A, -6A/+6T, and -6G/+6C nucleotide substitutions (Sequences 5, 6, and 7) resulted in a modest 3.4-, 5.6-, and 3.6-fold decrease in binding, respectively, compared to Sequence 1. The nucleotide substitution -5A/+5T (Sequence 9) resulted in a very small (1.9-fold) effect on binding while the substitutions -5G/+5C and -5C/+5G (Sequences 8 and 10) resulted in a modest 5.7-fold and 8.8-fold decrease in binding, respectively, indicating a small preference for AT base pairs at this position. These results suggest that specific base pairs at positions -6/+6 and -5/+5 are not imperative for a high Fis binding affinity.

The three symmetrical nucleotide combinations -4C/+4G, -4G/+4C, and -4T/+4A in Sequences 1, 11, and 13 were considerably well tolerated within a 6.4-fold difference in binding affinities. However, the combination -4A/+4T (Sequence 12) severely reduced Fis binding by over 2000-fold, suggesting that this particular nucleotide combination somehow interferes with binding. Since the -4A/+4T nucleotide combination in Sequence 12 created an A4-tract on one DNA strand and an A5-tract on the other strand, it was possible that the negative effect was related to an alteration in the local DNA structure created by the central A-tracts. To examine this possibility, we disrupted the A-tracts formed in Sequence 12 by introducing additional substitutions at positions -2/+2 in Sequences 14 and 15. Sequence 14 altered the AT-richness in the central region (with -2C/+2G) whereas Sequence 15 did not (with -2T/+2A). In both cases, the Fis binding affinity remained severely impaired, suggesting that the severe decrease in binding is not caused by the presence of A4 and A5-tracts in the central region. Since nucleotide substitutions at positions -2/+2 had minimal effects (within 2.7-fold) on DNA binding (e.g. Sequences 19, 20, and 21), the decrease in binding to Sequences 12, 14, and 15 was most likely caused by the presence of the nucleotides -4A/+4T.

Replacement of the sequence -3A/+3T in Sequence 1 with -3G/+3C in Sequence 18 had a small (2.9-fold) effect on Fis binding. However, replacements with either -3T/+3A (Sequence 16) or -3C/+3G (Sequence 17) caused about a 970-fold and >2000-fold reduction in the binding affinity, respectively. This suggested that the -3 purine/+3 pyrimidine combination is essential for a high specificity of binding.

Effects of the central DNA sequence

Fis-DNA docking models25; 34; 35 suggest that the three central nucleotides at positions -1 through +1 are too far to be contacted by any of the Fis residues known to be required for DNA binding.27; 32; 33 However, since many naturally occurring Fis binding sites contain a central AT-rich sequence, we examined the importance of the AT-richness in this region to the high-affinity binding by replacing the central AT base pairs with GC base pairs. The results showed that the GC replacement of the central three AT base pairs had <2-fold effects on the binding affinity (Sequences 22 and 23). However, when the GC-rich sequence was extended to span the central 5 positions from -2 to +2 (Sequence 24), there was over a 700-fold reduction in binding. Since nucleotide substitutions at -2 and +2 had minimal effects (e.g. Sequences 19-21), the severe reduction in binding to Sequence 24 was most likely attributed to a collective effect of the 5 central G and C nucleotides on the local DNA structure or flexibility.

To further examine the structural contributions of the central nucleotides, we performed GEMSA with larger DNA fragments that carried Sequences 1, 22, 23, and 24 near their centers in order to evaluate the relative Fis-induced DNA bending at these sites (Fig. 3). The presence of GC nucleotides in the central region of the Fis binding sites in Sequences 22, 23, and 24 caused a faster migration of the unbound DNA fragments relative to that of Sequence 1, suggesting that the central GC nucleotides decreased the intrinsic DNA curvature. The Fis-bound DNA fragments carrying Sequence 22 showed the same electrophoretic migration as that carrying Sequence 1, suggesting that similar Fis-induced DNA bending occurred in the two fragments. However, the Fis-bound complex with Sequence 23 migrated faster than that with Sequences 1 and 22, and the bound complex with Sequence 24 migrated faster than that with Sequence 23. This suggests that Fis-induced DNA bending decreased as the central GC content increased in Sequences 23 and 24. Since the binding affinity at Sequence 24 was substantially reduced relative to that at Sequence 1, the faster electrophoretic mobility of the Fis-bound complex at Sequence 24 may have been caused in part by the reduced binding affinity. However, since the binding affinity to Sequence 23 was similar to that at Sequences 1 and 22, the faster electrophoretic mobility of the bound complex at Sequence 23 can be largely attributed to a reduction in Fis-induced DNA bending. These results demonstrate that the central AT rich sequence is important for both the intrinsic DNA structure and the DNA flexibility of the Fis binding site.

Figure 3.

Effects of the central AT-richness on DNA binding and bending. (a) Fis-induced DNA bending. GEMSA was performed with 300 bp 32P end-labeled DNA fragments carrying either Sequence 1, 22, 23 or 24 near their centers. Bands representing free DNA and Fis-DNA complexes are indicated on the left. The DNA used is indicated beneath each lane. (b) The DNA sequences examined in panel (a) and their relative Fis binding affinities. The GC nucleotide substitutions near the central region are shown in bold letters.

Minimal number of critical base pairs required

Having identified -7G/+7C and -3R/+3Y as the most important nucleotides required for high Fis binding affinities, we explored the effects of single base pair replacements within these two pairs of positions (Table 1). The single nucleotide replacements +3T→G (Sequence 25) and +7C→G (Sequence 26) showed only about a 1.1-fold and 3.3-fold decrease in binding, respectively. This suggested that the presence of just three of the four critical nucleotides at the positions -7/+7 and -3/+3 is able to sustain a relatively high binding affinity. However, if only two of the four critical nucleotides were available at these positions in any combination, as was the case for Sequences 27 and 28 (and also Sequences 2-4, 16, and 17), then Fis-DNA binding was severely reduced (>2000-fold in most cases). Thus, within the context of an overall AT-rich central sequence (as in Sequence 1) a minimal of three of the four critical base pairs was required to sustain a considerably high Fis binding affinity.

Negative role of the +4 thymine C5 methyl group

Since the nucleotide sequence combination -4A/+4T was the only one at these positions that severely hindered Fis binding (Table 1, Sequence 12), we hypothesized that the 5-methyl group of the thymine at position +4 in both strands might be responsible for this effect. To test this idea, we constructed a binding site in which the thymines at positions +4 in both strands were replaced with deoxyuridine (dU), which is identical to deoxythymine (dT) except for the absence of the 5-methyl group in dU. We then compared the binding activity to this site with that to a site carrying dT at positions +4 in each strand (Fig. 4a and b). The results showed that the dU substitution of dT removed the negative effect on binding, demonstrating that the C5 methyl group on the +4T caused the severe binding hindrance. In order to verify that the restoration of Fis binding activity was not caused by the presence of dU itself, we completely removed the uracil bases by treatment with uracil-DNA-glycosylase and then tested the binding activity with the debased DNA. The results showed that removal of +4 uracil base on both DNA strands did not appreciably reduce Fis binding (Fig. 4c), demonstrating that a base at +4 is not essential for Fis binding.

Figure 4.

Effect of the +4 thymine C5-methyl group. Gel mobility shift assays were performed using various Fis concentrations with a 43 bp DNA fragment containing (a) Sequence 12, (b) a variant of Sequence 12 in which +4T was replaced with dU on both DNA strands, or (c) the sequence in panel B from which dU was specifically removed by treatment with uracil-DNA glycosylase. The DNA sequences of the Fis binding sites are shown above the gels and the base pairs at positions -4 and +4 in each half site are shown in bold. The positions of the unbound and bound DNA are indicated on the left of the gel image in panel A and the Fis concentrations used in the binding reactions are indicated beneath the lanes.

Effects of base removal on Fis binding

To further probe the role of the bases at all positions of a Fis binding sequence while using a different approach, we asked how the removal of bases affected binding. To this end, we generated random apurinic or apyrimidinic (AP) sites within the 32P-labeled DNA fragment containing Sequence 1 and conducted GEMSA to separate and purify the Fis-bound and -unbound DNA fractions. The DNA backbone was then cleaved at the AP sites and the DNA strands were separated by urea-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 5). The relative DNA band intensities are proportional to the relative abundance of corresponding AP sites in the bound and unbound DNA fractions. The results with depurinated DNA showed that removal of the bases -8A (in the flanking region), -7G, -2A, and -1A in either DNA strand considerably hindered Fis binding since their corresponding cleavage signals were substantially reduced in the bound compared to the unbound DNA fractions (Fig. 5a). A relatively smaller effect on Fis binding was observed with the removal of +9A (in the flanking region), +6G, +5A, +4G, and -3A (Fig. 5a and c). No other purines in the flanking region were found to influence Fis binding. The results with depyrimidinated DNA showed that removal of the bases +2T and +3T in either DNA strand also reduced Fis binding (Fig. 5b). Much smaller effects were observed by the removal of -6C, -5T, +1T, and +7C, and no effects were observed by the removal of pyrimidines in the flanking region (Fig. 5b and c).

Figure 5.

Identification of bases contributing to Fis binding. (a) Missing contact assay performed with depurinated 75 bp DNA fragments containing Sequence 1. Results using DNA labeled with 32P on the top or bottom strand (as they appear in panel c) are shown. The left lane in each set shows the Maxam-Gilbert G+A sequencing reactions; the center and right lanes show the piperidine cleavage results for the unbound and bound DNA fractions, respectively. The region spanning the 15 bp Fis core binding sequence is shown by a vertical line on the left of each gel image. Arrowheads point to bands that are significantly less intense in the Fis-bound DNA lane compared to the unbound DNA lane and are labeled according to the bases they represent. (b) Missing contact assay performed with depyrimidinated DNA fragments containing Sequence 1. The left lanes display the Maxam-Gilbert C+T sequencing reactions. All other labels are as in panel a. (c) Quantitative representation of the results from panels a and b. The relative loss of signal intensity at each position in the bound DNA fraction is represented by vertical lines with relative heights representing the ratio of unbound/bound DNA signals quantified by phosphorimaging and normalized by the ratio of band intensities for a commonly unaffected signal. Upper case letters represent the 15 bp core nucleotides in Sequence 1; lower case letters represent flanking sequence. Bold letters represent bases that, when removed, cause >3-fold decrease in band intensity in the bound compared to unbound DNA.

These results confirmed the importance of the -7/+7 and -3/+3 base pairs observed in the nucleotide substitution analysis, but also expanded this information to implicate important roles played by the bases -8A, -2A, -1A, and +2T. More specifically, the results suggested that the bases -7G and +3T were much more important for Fis binding than their complementary bases at the same positions (Fig. 5c). In order to verify this observation, we performed GEMSA using heteroduplex DNA fragments containing miss matched base pairs at -7/+7 or -3/+3 in Sequence 1 (Fig. 6). We found that the Fis binding sites containing the mismatched base pairs -7G•T/+7T•G or -3C•T/+3T•C were able to bind Fis reasonably well, requiring Fis concentrations between 5 to 11 nM to achieve ≥50% binding (Fig. 6a and c). However, the Fis binding sites containing the mismatched base pairs -7A•C/+7C•A or -3A•G/+3G•A were severely hindered in Fis binding, requiring >2 μM Fis to achieve 50% binding (Fig. 6b and d). Thus, we concluded that the bases -7G and +3T are the most critical ones for a high Fis binding affinity, while their complementary bases make substantially smaller contributions.

Figure 6.

Effect of single nucleotide replacement on Fis binding. GEMSA was conducted with 43 bp DNA fragments carrying one of four derivatives of Sequence 1 with the following base pair mismatches: (a) -7 G•T / +7 T•G, (b) -7 A•C / +7 C•A, (c) -3 C•T / +3 T•C, and (d) -3 A•G / +3 G•A. The replaced bases are shown in bold. The positions of the free and bound DNA are indicated on the left in panel (a) and the Fis concentrations are indicated beneath the lanes.

Effect of the flanking base pairs at positions -8/+8 and -9/+9

Despite the poor conservation of the flanking DNA sequences, the results of the missing contact assay showed that the -8 base, and to a lesser extent the +9 base, influenced Fis binding. To further explore the possible structural role of these bases, we performed DNase I footprinting on three Fis binding sites (Sequences 1, 29, and 30) differing only in the base pairs at the positions -8/+8 and -9/+9 (Fig. 7). The results showed that nearly full DNase I cleavage protection was achieved in Sequence 1 with 5 ng Fis and two strong DNase I hypersensitive cleavage sites occurred at positions -5 and +8 upon Fis binding (Fig. 7a and b). This suggested that Fis-induced DNA bending caused an opening of the minor groove regions containing these two positions to enhance DNase I cleavage. Sequences 29 (-8C/+8G) and 30 (-8C/+8G; -9G/+9C) required ≥10 ng Fis to achieve a nearly complete protection of DNase I cleavage, suggesting a reduction in the binding affinity to these sites relative to Sequence 1. The DNase I hypersensitive cleavage pattern also changed in these two sequences. In Sequence 29, one hypersensitive cleavage site shifted from position +8 to +7 and the cleavage activities at both -5 and +7 were reduced relative to Sequence 1. In Sequence 30, Fis-induced DNase I hypersensitive cleavage was not detected at -5, +7, or +8 positions. These results suggest that the G•C base pair substitutions of A•T base pairs at -8/+8 and -9/+9 reduce the local DNA flexibility, which hinders the Fis-induced DNA bending and moderately reduces the binding affinity.

Figure 7.

Effect of flanking DNA sequence on Fis binding and DNA flexibility. DNase I footprinting was performed using DNA fragments labeled with 32P on either (a) the top or (b) bottom strands (as shown in panel c) which contained Sequence 1, Sequence 29 (-8C/+8G), or Sequence 30 (-8C/+8G; -9G/+9C). The DNA fragments and amount of Fis used in each reaction are indicated above the lanes. Lanes labeled S contain Maxam-Gilbert sequencing reactions for G and A nucleotides in Sequences 1, 29 and 30. The gel regions containing the Fis core-binding site are indicated with vertical lines. Arrows denote the positions of Fis-induced DNase I hypersensitive cleavage sites. (c) DNA sequences of the three Fis binding sites examined in panel (a). The core DNA sequences numbered from -7 to +7 are shown in capital letters. Flanking sequences are shown in lower case letters. Substituted bases at -8/+8 and -9/+9 are shown in bold. Vertical arrows indicate the positions of Fis-induced DNase I hypersensitive cleavage; the relative size of the arrows qualitatively represents the relative DNase I cleavage activity.

DISCUSSION

DNA sequence requirements for Fis binding

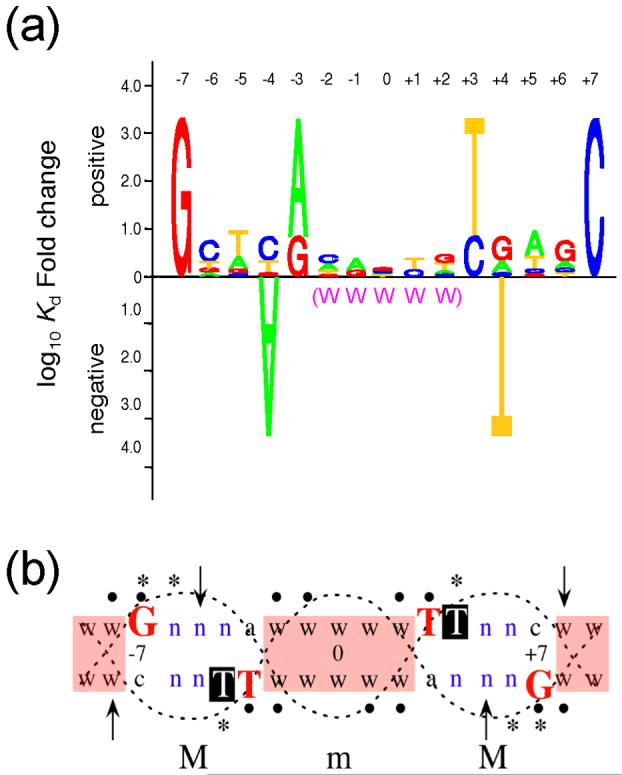

The results of our systematic base pair substitution study showed that specific base pairs at four positions (-7G, -3R, +3Y, +7C and their complements) are required for a relatively high Fis binding affinity, whereas the nucleotide combination -4A/+4T severely hinders binding. These results can be represented with a Fis-binding affinity-based sequence logo, which provides information about the relative nucleotide contributions at symmetrical positions in the Fis binding site to the in vitro binding affinity (Fig. 8a). Although each individual position in the central region from -2 to +2 is able to tolerate base pair substitutions without substantially affecting Fis binding, there is a preference for an overall AT-rich sequence in this central region, which is represented in the logo by Ws. Hence, the presence of -7G/+7C and -3R/+3Y combined with a central AT-rich sequence and the absence of -4A/+4T, specify the principal conditions for a high-affinity Fis binding site. Ethylation interference studies (Shao and Osuna, unpublished data) demonstrated that 14 phosphates in the region from -8 to +4 on each strand may be contacted during Fis binding, indicating that there is a strong indirect readout contribution to the stability of the Fis-DNA complex.

Figure 8.

Summary of features in a high-affinity Fis binding sequence. (a) Fis binding site logo. The logo displays the relative functional contribution of bases within the 15 bp core sequence of the Fis binding site. Bases are represented by A, T, C, and G. The height of the stack of letters represents the maximum effect on the Kd when altering bases at symmetrical positions of the binding site. The relative preference for different bases at each position is represented by their relative heights. The letter stacks at positions -1 and +1 do only consider the nucleotide combinations -1A/+1T and -1G/+1C. The -4A and +4T bases point downward to indicate their severe negative effects. A global preference for A or T in the central region of binding site from -2 to +2 is denoted by W’s in parenthesis. (b) DNA factors affecting Fis-DNA binding and bending. A double stranded DNA is used to represent the 15 bp core Fis binding site and two flanking bp at each side. The large red letters represent four critical bases shown to be required for a high Fis binding affinity. The white in black Ts represent the positions of the +4 thymines that interfere with Fis binding. n represents positions where substantial nucleotide preferences were not observed; w denotes positions (shaded in pink) where A or T bases are generally preferred and, when present, facilitate Fis-induced DNA bending. Filled dots indicate positions where the presence of a base was required for efficient Fis-DNA binding; asterisks indicate positions protected from methylation by Fis when the base is G;37; 38 arrows point to the Fis-induced DNase I hypersensitive sites. Major (M) and minor (m) groove regions of DNA are outlined with dotted lines.

A sequence logo of Fis binding sites presented by Hengen, et al.36 depicted the relative frequencies of bases among 60 experimentally defined Fis binding sites. Our Fis binding affinity-based logo (Fig. 8a) bears many similarities to the nucleotide frequency-based logo. Among these are the clear preferences for -7G/+7C, -3R/+3Y (preferably -3A/+3T) and for an overall AT-rich sequence in the central region from -2 to +2. However, while the nucleotide frequencies-based logo suggests little or no nucleotide preferences at positions -4/+4, our binding affinity-based logo depicts a strong negative effect by the -4A/+4T nucleotide combination. The overall good agreement between the two logos suggests that our analysis of nucleotide sequence preferences based on in vitro Fis binding affinities to linear DNA fragments properly reflect the nucleotide sequence preferences of naturally-occurring Fis binding sites with known functions in vivo. Thus, while DNA supercoiling levels may alter the stability of Fis-DNA interactions,5 we suggest that the relative nucleotide sequence preferences for specific Fis binding are essentially the same in relaxed or supercoiled DNA.

The role of -7G and +3Y bases

Our results from the Fis binding experiments to DNA fragments containing random AP sites (“missing contact assay”) and to heteroduplex DNA fragments more precisely indicated that the guanines in the -7G•C and +7C•G base pairs and the thymines in the -3A•T and +3T•A base pairs in Sequence 1 are the bases primarily responsible for the very high Fis binding affinity (Fig. 8b). Several Fis-DNA docking models26; 34; 35 place the essential Fis R85 residue of the recognition helix (Fig. 1) facing -7G via the major groove and is therefore a good candidate for establishing hydrogen bonds with N7 and O6 of -7G. Adenine, which also contains N7 but not O6, cannot replace guanine at position -7. We therefore infer that a Fis contact with O6 or both O6 and N7 of -7G may be required for the sequence recognition. Consistent with this idea is the finding that Fis protects -7G from N7 methylation.37; 38 In sequences where the 3′ neighboring base at -6 was also a guanine, it was also protected from methylation (Fig. 8b). However, since our results showed that -6G itself is not required for Fis binding (Table 1 and Fig. 5), methylation protection of -6G most likely results from occlusion caused by one or more Fis side chains (e.g. R85 or R89) as they extend over -6G to contact -7G or a neighboring phosphate.

DNA docking models also place the essential T87 and K90 Fis residues near the +3T base of either DNA strand and thus can potentially form direct or water-mediated hydrogen bonds with these thymine bases via the major groove (e.g. with thymine O4). However, since replacements of -3A•T and +3T•A base pairs with G•C and C•G base pairs, respectively, result in a similarly high Fis binding affinity, it is possible that other contacts are made with G•C base pairs at these positions. In a missing contact assay using a DNA sequence carrying the -3G•C and +3C•G base pairs we observed that the +3C base was not required for high binding affinity while the -3 guanine was required (data not shown). Thus, it is possible that the +3 guanine in these base pairs serves as a contacting site via the major groove (e.g. with guanine O6).

The negative effect of the -4A/+4T combination

The severe negative effect of -4A/+4T on Fis binding is consistent with the complete absence of this nucleotide combination among 60 known Fis binding sites.36 We showed that this negative effect is caused primarily by the C5 methyl group on the +4 thymine base. This methyl group may obstruct the path of a Fis residue side chain (e.g. K90) attempting to contact a nearby base or phosphate. The appearance of two prominent Fis-induced DNase I hypersensitive sites at -5 and +8 indicate that Fis binding results in a widening of the minor groove in the regions from about -9 to -4 and from +4 to +9 with a corresponding compression of the opposite major grooves. Thus, it is also possible that the +4T C5 methyl group located in this major groove impedes this compression, which may be required for stable Fis-DNA interactions. A related observation is that Fis protects a +4G base from N7 methylation.37; 39 Since +4G is not essential for Fis binding (Fig. 8b, Table 1), it is unlikely to serve as a contact site. We infer that the same structural factors causing the +4T C5 methyl group to interfere with Fis binding may also cause interference of N7 methylation at +4G upon Fis binding.

Role of AT-rich sequences

The distance between the two recognition helices in the Fis crystal structure is about 25 Å,28; 29; 30; 31 while the average distance between two adjacent major grooves in B-form DNA is about 34 Å. Thus, some amount of DNA bending and twisting appears to be required to accommodate this difference and thus maximize the Fis-DNA interactions at each half site. This is consistent with the findings that Fis is able to bend DNA by about 40 to 90°.7; 40; 41 A central AT rich sequence in the region from -2 to +2 was found to affect both the intrinsic DNA curvature and the extent of Fis-induced DNA bending (Fig. 3). The severity of these structural effects varied with the extent of AT-richness. Since the base pairs at positions -2 and +2 or in the region from -1 to +1 had minimal effects on Fis binding, the bases in this central region are unlikely targets of Fis contact. Thus, the substantial (767-fold) drop in binding to a sequence carrying GC base pairs in the entire region from -2 to +2 is most likely attributed to a local decrease in DNA flexibility and Fis-induced DNA bending, which may impair stable Fis-DNA interactions on both halves of the binding site.

No sequence conservation is observed in the flanking region, suggesting that the flanking bases do not serve as contact sites. However, AT base pairs at positions -8/+8 and -9/+9 resulted in greater DNA flexibility and a moderate increase in the binding affinity than GC base pairs. These observations are consistent with interpretations from previous flanking sequence swapping experiments, which resulted in relatively small differences in the binding affinity but noticeable differences in Fis-induced DNA bending.26 In those experiments, it was also noticed that flanking sequences generally rich in A•T bp had a greater tendency to facilitate DNA bending. Similar observations have been made for other DNA binding and bending proteins such as IHF (integration host factor) and the yeast GC box-binding protein MIG1.42; 43

It was previously shown that the presence of the 2-amino group of guanine, which lies in the minor grove, decreases the DNA intrinsic curvature and flexibility in the tyrT promoter region, which contains four Fis binding sites.44 Replacements of guanines for inosines (which lack the 2-amino group) increased the intrinsic DNA curvature as well as the Fis-induced DNA bends, and resulted in a measurable increase in the Fis binding affinity. Conversely, replacements of adenines with 2, 6-diaminopurines (which contain a 2-amino group) decreased the intrinsic DNA curvature as well as the Fis-induced DNA bends and caused a decrease in the binding affinity. The absence of the 2-amino group in adenine bases may allow the conformational freedom of AT-rich sequences to increase the anisotropic flexibility and to adopt a high propeller twist that is often associated with a narrow minor groove.

The favorable effects of AT-rich sequences on Fis binding in vitro predict that Fis binding sites abound in AT-rich chromosomal regions such as are many intergenic regions. Indeed, in recent work employing chromatin immunoprecipitation combined with high density microarrays (ChIP-chip) to study the binding of three nucleoid-associated proteins across the E. coli genome in vivo, a large number of DNA binding positions was identified for Fis (>20,000) within AT-rich sequences and ∼50% of them were located in non-coding DNA.45 Since non-coding DNA accounts for <10% of the genome, this represents a substantial bias toward intergenic regions. Many of the identified Fis-DNA binding targets were also associated with H-NS, which is also known to have a preference for AT-rich sequences. Additionally, ∼50% of the non-coding targets for Fis were also associated with RNA polymerase. DNA microarray analysis performed in E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium demonstrated a role for Fis in coordinately regulating several hundred genes involved in diverse cellular functions such as virulence, flagella biosynthesis and motility, energy and intermediate metabolism, nutrient transport, translation, stress response, amino acid and nucleotide metabolism, among others.13; 14

Degeneracy of Fis binding sites

An understanding of how Fis is able to exhibit strong binding affinities to DNA sites of poorly related sequences has been largely elusive. We have seen that a great deal of sequence degeneracy results from the non-critical nucleotide positions -6/+6, -5/+5, -4/+4 and -2 through +2, where most base pair combinations (except -4A/+4T) can be relatively well tolerated with modest effects on Fis binding (Fig. 8a). A degree of sequence flexibility also occurs because of the similar contributions to Fis binding by -3A or G and +3T or C (within about a 2.9-fold difference in binding). Additional sequence degeneracy arises from the ability of Fis to bind DNA sites containing only three of the four critical base pairs at -7, -3, +3, and +7 within about a 3.3-fold reduction in binding. Such tolerance for the loss of an important Fis-DNA contact may be strongly dependent on DNA sequence contexts (e.g. with central and flanking AT-rich bases) exhibiting structural features that facilitate DNA bending and maximize Fis-DNA backbone interactions. For instance, we previously showed that an alanine replacement of arginine 89 in the Fis recognition helix (Fig. 1) causes a 12-fold reduction in binding to the λ attR Fis site (involved in the Fis-dependent stimulation of λ phage DNA excision from the chromosome) when AT-rich flanking sequences are present to facilitate DNA bending, but results in over a 400-fold reduction in binding when GC-rich flanking sequences are present to limit DNA bending.27 Thus, potentially adverse effects resulting from the absence of a critical DNA contact can sometimes be mitigated by the presence of DNA structural features that maximize backbone interactions. This compensatory interplay between direct and indirect readout effects is also a potential contributor to the variability of Fis binding sequences. An enormous number of combinations of non-symmetrical base pairs are of course also possible and, indeed, observed among Fis binding sites and their effects have not yet been tested. It is possible that certain non-symmetrical combinations may have severe effects on the Fis binding affinity just as it is possible that some may have compensatory effects.

The sequence degeneracy of Fis binding sites is an asset to the role of Fis in modulating DNA topology5 since DNA binding sites of varying binding affinities can be accommodated within a wide range of genomic DNA sequences. In addition, it provides a way to fine-tune the specific DNA binding affinities within about a 10-fold range. This creates an opportunity for cells to regulate Fis-mediated processes as a function of the intracellular Fis concentration, which changes dramatically with the growth phase, the growth rate, and the nutritional state.46; 47; 48 Whereas, sites of high Fis binding affinities may be occupied under a range of intracellular Fis concentrations (provided other factors do not interfere with binding), relatively weaker binding sites may tend to rely on very high intracellular Fis concentrations for stable occupancy. Hence, Fis-mediated processes involving relatively weaker specific binding sites may be regulated by large changes in the intracellular Fis concentrations. Indeed, we have observed that placement of a high-affinity Fis binding site within the spacer region of a promoter confers considerable Fis-dependent repression during both early and late logarithmic growth phases, whereas lower affinity Fis binding sites limit the regulatory effects to the early logarithmic growth phase when Fis levels are very high (Y. Shao and R. Osuna, unpublished results).

Since the composition of central and flanking sequences affects the Fis-induced DNA bending with modest effects on the binding affinity, specific binding sites can be outfitted to function in processes requiring various degrees of DNA bending. The stimulation of λ phage DNA excision from the chromosome and of the ribosomal rrnB P1 promoter transcription are examples of Fis-mediated processes that appear to require a measure of Fis-induced DNA bending.32; 49 Moreover, binding studies based on DNA cleavage activity by a collection of Fis conjugates to 1,10-phenanthroline-copper suggested that each of the flanking sequences can differentially affect the degree of DNA bending on each side of the binding site, sometimes resulting in asymmetry of bending.26 Thus, a variety of nucleoprotein structures are possible with Fis to satisfy a large range of DNA bending requirements in different processes, including its role in altering the DNA topology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Enzymes

General chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Fisher Scientific, Life Technologies (GIBCO-BRL), or VWR Scientific. Formic acid (88%) was from J. T. Baker. Enzymes used in this study were from New England BioLabs, Inc., Promega Corp., or Roche Molecular Biochemicals. Radioisotopes [α-32P] dATP and [γ-P32] ATP were from Amersham Biosciences. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by the Comparative Center for Functional Genomics, University at Albany, NY or by Integrated DNA Technology, Co. Purified Fis (>99% pure) was made according to described procedures.27; 32

Fis binding sites

Two complementary oligonucleotides (20 and 28 nucleotides long) were synthesized such that they would carry one of the 30 Fis binding sites used in this work flanked by sequences that anneal to the protruding DNA strands of cleaved BglII or SacI sites. The 5′ ends were phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase and ATP.50 The complementary oligonucleotides were then annealed and cloned into pCY4 vector51 between the unique BglII and SacI sites. All of the cloned Fis sites were verified by dideoxy DNA sequencing using DNA Sequenase 2.0 and dideoxynucleotides, as described by the supplier (USB Corp.).

Gel electrophoretic mobility shift assay (GEMSA)

Plasmids containing the cloned Fis binding sites were digested with BamHI and EcoRI, which released 43 bp fragments harboring a Fis site at their center. These fragments were end-labeled using Klenow enzyme, 5μCi [α-32P] dATP, and 0.2 mM each of dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP50, and then purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in TBE buffer (89 mM Tris-base, 89 mM boric acid, pH 8.3, 2.5 mM EDTA) using the crush and soak method.50 About 0.05 nM end-labeled DNA (1 fmol) was mixed with various concentrations of purified Fis in 20 μl binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 80 mM NaCl, 50 ng/μl bovine serum albumin), incubated at room temperature for 10 min, and combined with loading buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 80 mM NaCl, 50 ng/μl bovine serum albumin, 100 μg/ml sonicated salmon sperm DNA, 7.5% Ficoll, 0.1% bromophenol blue). Samples were then loaded onto 8% polyacrylamide bis-acrylamide (60:1) gels in TBE with a 15 mA conducting current. The relative DNA signal intensities in the bound and unbound states were quantified by phosphorimaging. The percentage of bound DNA fragments was plotted against the molar Fis concentration and used to obtain the dissociation constant (Kd) defined as the concentration of Fis required to achieve 50% maximal binding. For each DNA fragment analyzed, the results from three separate binding assays were fitted with Kaleidagraph v.3.5 using the equation Y = ([Fis]/([Fis] + Kd))*(M), where Y is the percent bound DNA and M is the maximal DNA binding extrapolated by the curve fit (R2 > 0.95). Due to the presence of a variable portion of the 32P-labeled DNA that remained inactive for Fis binding or cleavage by restriction enzyme, the saturation value (M) typically varied between 75 and 100% depending on the DNA fragment. Kd values are given as an average ± standard deviations of three binding assays.

In the GEMSA used to monitor Fis-induced DNA bending, 375 bp DNA fragments carrying Sequences 1, 22, 23, or 24 were obtained by cleavage of appropriate pCY4-based plasmids with NheI and end-labeled with [α-32P]dATP using the Klenow end-filling reaction.50 The labeled DNA fragments carrying the Fis binding sites were purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. GEMSA was then performed as described above using the labeled DNA and an appropriate concentration of Fis to partially bind DNA.

Construction of bp mismatches and abasic sites

To create Fis binding sites with mismatched base pairs at desired positions, imperfect sets of complementary 43-base oligonucleotides were custom synthesized. One oligonucleotide strand was 5′-end labeled with 32P using T4 polynucleotide Kinase and [γ-32P] ATP, annealed with its imperfect complementary strand, and purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as described.50 To create an abasic site at positions -4 and +4 within the Fis binding sequence 1, deoxyuracil was introduced into these positions during oligonucleotide synthesis. The resulting 43-base oligonucleotide was 5′-end labeled with 32P, annealed with its complementary strand, and purified as described above. The double-stranded DNA was then treated with 1 unit of uracil-DNA-glycosylase (UDG, NEB Inc.) for 30 minutes at 37°C to completely remove deoxyuracil. The UDG was removed by tandem phenol-chloroform and chloroform extractions, and the DNA was precipitated at -20°C in the presence of 83 mM sodium acetate and 70% ethanol. Complete removal of deoxyuracil from the DNA was verified by subsequent cleavage with 10% piperidine at 90°C for 30 min followed by urea-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the resulting cleavage products.

Fis sequence logo

A Fis binding sequence logo was created on the basis of the experimentally observed contributions of each bp within the 15 bp core Fis binding sequences to the relative binding affinity. The maximal effects on binding affinities caused by base substitutions at each position along the Fis binding site are represented by the total height (Htotal) of the stack of letters at each position, which was determined as follows: Htotal = log10 (Kd max / Kd min), where Kd max and Kd min are the Kd values observed with the least and most preferred base substitutions, respectively. In cases where the Kd is greater than 2000 nM, a Kd max of 2000 nM was used for calculation, and the Htotal is an understimate. The relative base preference at each position is represented by the relative height of each single letter within a stack (Hbase), which is determined as follows: Hbase = Htotal (1/Kd base) / (1/Kd A + 1/Kd C + 1/Kd G + 1/Kd T), where Kd base is the Kd value observed when the position carries the base of interest and Kd A, Kd C, Kd G, and Kd T are the Kd values observed when the corresponding A, C, G, and T bases are present. To represent the large negative effect on binding by the -4A/+4T combination, -4A and +4T are shown in a downward orientation and the relative heights of these letters are calculated as log10 (Kd max / Kd min). Htotal and Hbase for the other three base pair combinations at this position (-4G/+4C, -4T/+4A and -4C/+4G) showing relatively small effects were calculated as above using only the Kd values for the -4C/+4G, -4G/+4C and -4T/+4A combinations.

Missing contact assay

A 75 bp BamHI-HindIII DNA fragment carrying Sequence 1 was end-labeled with [α-32P]dATP using the Klenow-based fill-in reaction at the BamHI or HindIII site, and electrophoretically purified as described.50 The 32P-labeled DNA was randomly debased to create apurinic or apyrimidinic (AP) sites as described.52 To generate apurinic sites, about 5 × 105 cpm of 32P-end labeled DNA was mixed with 3 μg sonicated salmon sperm DNA in a 15 μl volume. The DNA was incubated at 37°C for 10 min in the presence of 0.4% (v/v) formic acid, precipitated twice in the presence of 83 mM sodium acetate and 70% ethanol, rinsed with 70 % ethanol, vacuum dried, and resuspended in 20 μl H2O. To generate apyrimidinic (AP) sites, the 32P-end labeled DNA was mixed with 3 μg sonicated salmon sperm DNA in a 25 μl volume. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min in the presence of 37% (v/v) hydrazine anhydrous. DNA was then precipitated by addition of 1 ml butanol, resuspended in 100 μl H2O and then precipitated twice in the presence of 83 mM sodium acetate and 70% ethanol, rinsed with 70% ethanol, vacuum dried, and resuspended in 20 μl dH2O. DNA carrying random AP sites was used in GEMSA in the presence of sufficient Fis to achieve about 40-50% binding. The bound and unbound DNA was excised from the gel and recovered using QIAEX®II Gel Extraction kit (QIAGEN Inc.) and subjected to DNA backbone cleavage in the presence of 10% piperidine at 90°C for 30 min. The DNA was dried under vacuum, resuspended in 90% formamide and 0.01% bromophenol blue, heated to 90 °C for 2 min, and electrophoretically separated in a 12% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel. The gels were subjected to autoradiography and phosphorimaging for measurement of relative band intensities.

DNase I footprint

DNase I protection by Fis was performed essentially as described previously.46 A 75 bp BamHI-HindIII DNA fragment carrying Sequence 1, 29, or 30 was labeled with [α-32P]dATP at either the BamHI or HindIII sites using Klenow fragment as described,50 and then purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using the crush-and-soak-method to elute the fragments.50 The binding reactions were performed with 10,000 cpm of 32P-labeled DNA fragments and the indicated amounts of purified E. coli Fis in 45 μL of buffer (20 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.5], 80 mM NaCl), and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. DNase I cleavage was performed with 5 μL of 150 ng/mL DNase I for 30 sec. Chemical cleavage reactions specific for G and A53 were also performed with the same DNA fragments and used as sequence reference. DNA products were separated on 8% polyacrylamide sequencing gels containing 8 M urea.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Kristi A. Minassian for her analysis of the relative binding affinities to naturally occurring Fis sites, Sara Seepo for constructing one of the plasmids used in this work, and Dr. Wilfredo Colón (Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, NY) for useful discussions. This work was supported in part through NIH grant GM52051 to R.O., a Faculty Research Award to R.O. from the University at Albany, a College of Arts and Sciences Research Develoment Award to R.O. from the University at Albany, and funds from the Office of the Vice President for Research at the University at Albany.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azam TA, Ishihama A. Twelve species of the nucleoid-associated protein from Escherichia coli. Sequence recognition specificity and DNA binding affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33105–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.33105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boswell S, Mathew J, Beach M, Osuna R, Colon W. Variable contributions of tyrosine residues to the structural and spectroscopic properties of the factor for inversion stimulation. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2964–77. doi: 10.1021/bi035441k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beach MB, Osuna R. Identification and characterization of the fis operon in enteric bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:5932–46. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5932-5946.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osuna R, Lienau D, Hughes KT, Johnson RC. Sequence, regulation, and functions of Fis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:2021–32. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2021-2032.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider R, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G. FIS modulates growth phase-dependent topological transitions of DNA in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;26:519–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5951971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider R, Travers A, Kutateladze T, Muskhelishvili G. A DNA architectural protein couples cellular physiology and DNA topology in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;34:953–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkel SE, Johnson RC. The Fis protein: it’s not just for DNA inversion anymore. Mol. Microbiol. 1992;6:3257–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinreich MD, Reznikoff WS. Fis plays a role in Tn5 and IS50 transposition. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:4530–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4530-4537.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson RC, Bruist MF, Simon MI. Host protein requirements for in vitro site-specific DNA inversion. Cell. 1986;46:531–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90878-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahmann R, Rudt F, Koch C, Mertens G. G inversion in bacteriophage Mu DNA is stimulated by a site within the invertase gene and a host factor. Cell. 1985;41:771–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betermier M, Lefrere V, Koch C, Alazard R, Chandler M. The Escherichia coli protein, Fis: specific binding to the ends of phage Mu DNA and modulation of phage growth. Mol. Microbiol. 1989;3:459–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorgai L, Oberto J, Weisberg RA. Xis and Fis proteins prevent site-specific DNA inversion in lysogens of phage HK022. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:693–700. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.693-700.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradley MD, Beach MB, Jason de Koning AP, Pratt TS, Osuna R. Global Effects of Fis on Escherichia coli Gene Expression During Different Stages of Growth. Microbiology. 2007 doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/008565-0. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly A, Goldberg MD, Carroll RK, Danino V, Hinton JC, Dorman CJ. A global role for Fis in the transcriptional control of metabolism and type III secretion in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microbiology. 2004;150:2037–53. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, Johnson RC. Identification of genes negatively regulated by Fis: Fis and RpoS comodulate growth-phase-dependent gene expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:938–47. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.938-947.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Gil G, Bringmann P, Kahmann R. FIS is a regulator of metabolism in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;22:21–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosch L, Nilsson L, Vijgenboom E, Verbeek H. FIS-dependent transactivation of tRNA and rRNA operons of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1050:293–301. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross W, Thompson JF, Newlands JT, Gourse RL. E. coli Fis protein activates ribosomal RNA transcription in vitro and in vivo. EMBO J. 1990;9:3733–42. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falconi M, Prosseda G, Giangrossi M, Beghetto E, Colonna B. Involvement of FIS in the H-NS-mediated regulation of virF gene of Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;42:439–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prosseda G, Falconi M, Giangrossi M, Gualerzi CO, Micheli G, Colonna B. The virF promoter in Shigella: more than just a curved DNA stretch. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:523–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg MD, Johnson M, Hinton JC, Williams PH. Role of the nucleoid-associated protein Fis in the regulation of virulence properties of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;41:549–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheikh J, Hicks S, Dall’Agnol M, Phillips AD, Nataro JP. Roles for Fis and YafK in biofilm formation by enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;41:983–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson RL, Libby SJ, Freet AM, Boddicker JD, Fahlen TF, Jones BD. Fis, a DNA nucleoid-associated protein, is involved in Salmonella typhimurium SPI-1 invasion gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;39:79–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubner P, Arber W. Mutational analysis of a prokaryotic recombinational enhancer element with two functions. EMBO J. 1989;8:577–85. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng JA, Yuan HA, Finkel SE, Johnson RC, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Dickerson RE. In: The interaction of Fis protein with its DNA binding sequences. Sarma R. H. S. a. M. H., editor. Vol. 2. Adenine Press; Schenectady: 1992. structure & function. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan CQ, Finkel SE, Cramton SE, Feng JA, Sigman DS, Johnson RC. Variable structures of Fis-DNA complexes determined by flanking DNA-protein contacts. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;264:675–95. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman LS, Shao YP, Meinhold D, Miller C, Colon W, Osuna R. Common and Variable Contributions of Fis Residues to High-Affinity Binding at Different DNA Sequences. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:2081–2095. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.6.2081-2095.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kostrewa D, Granzin J, Koch C, Choe HW, Raghunathan S, Wolf W, Labahn J, Kahmann R, Saenger W. Three-dimensional structure of the E. coli DNA-binding protein FIS. Nature. 1991;349:178–80. doi: 10.1038/349178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kostrewa D, Granzin J, Stock D, Choe HW, Labahn J, Saenger W. Crystal structure of the factor for inversion stimulation FIS at 2.0 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;226:209–26. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safo MK, Yang WZ, Corselli L, Cramton SE, Yuan HS, Johnson RC. The transactivation region of the Fis protein that controls site-specific DNA inversion contains extended mobile beta-hairpin arms. EMBO J. 1997;16:6860–73. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.22.6860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan HS, Finkel SE, Feng JA, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Johnson RC, Dickerson RE. The molecular structure of wild-type and a mutant Fis protein: relationship between mutational changes and recombinational enhancer function or DNA binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1991;88:9558–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osuna R, Finkel SE, Johnson RC. Identification of two functional regions in Fis: the N-terminus is required to promote Hin-mediated DNA inversion but not lambda excision. EMBO J. 1991;10:1593–603. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koch C, Ninnemann O, Fuss H, Kahmann R. The N-terminal part of the E.coli DNA binding protein FIS is essential for stimulating site-specific DNA inversion but is not required for specific DNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5915–22. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.21.5915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandmann C, Cordes F, Saenger W. Structure model of a complex between the factor for inversion stimulation (FIS) and DNA: modeling protein-DNA complexes with dyad symmetry and known protein structures. Proteins. 1996;25:486–500. doi: 10.1002/prot.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tzou WS, Hwang MJ. Modeling helix-turn-helix protein-induced DNA bending with knowledge-based distance restraints. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1191–205. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76971-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hengen PN, Bartram SL, Stewart LE, Schneider TD. Information analysis of Fis binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4994–5002. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruist MF, Glasgow AC, Johnson RC, Simon MI. Fis binding to the recombinational enhancer of the Hin DNA inversion system. Genes. Dev. 1987;1:762–72. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.8.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bokal AJ, Ross W, Gaal T, Johnson RC, Gourse RL. Molecular anatomy of a transcription activation patch: FIS-RNA polymerase interactions at the Escherichia coli rrnB P1 promoter. EMBO J. 1997;16:154–62. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bokal A. J. t., Ross W, Gourse RL. The transcriptional activator protein FIS: DNA interactions and cooperative interactions with RNA polymerase at the Escherichia coli rrnB P1 promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;245:197–207. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gille H, Egan JB, Roth A, Messer W. The FIS protein binds and bends the origin of chromosomal DNA replication, oriC, of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4167–72. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson JF, Landy A. Empirical estimation of protein-induced DNA bending angles: applications to lambda site-specific recombination complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9687–705. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hales LM, Gumport RI, Gardner JF. Examining the contribution of a dA+dT element to the conformation of Escherichia coli integration host factor-DNA complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1780–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.9.1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lundin M, Nehlin JO, Ronne H. Importance of a flanking AT-rich region in target site recognition by the GC box-binding zinc finger protein MIG1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:1979–85. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailly C, Waring MJ, Travers AA. Effects of base substitutions on the binding of a DNA-bending protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;253:1–7. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grainger DC, Hurd D, Goldberg MD, Busby SJ. Association of nucleoid proteins with coding and non-coding segments of the Escherichia coli genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4642–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ball CA, Osuna R, Ferguson KC, Johnson RC. Dramatic changes in Fis levels upon nutrient upshift in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:8043–56. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8043-8056.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ninnemann O, Koch C, Kahmann R. The E. coli fis promoter is subject to stringent control and autoregulation. EMBO J. 1992;11:1075–83. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mallik P, Paul BJ, Rutherford ST, Gourse RL, Osuna R. DksA is required for growth phase-dependent regulation, growth rate-dependent control, and stringent control of fis expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:5775–82. doi: 10.1128/JB.00276-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gosink KK, Ross W, Leirmo S, Osuna R, Finkel SE, Johnson RC, Gourse RL. DNA binding and bending are necessary but not sufficient for Fis-dependent activation of rrnB P1. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:1580–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1580-1589.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prentki P, Pham MH, Galas DJ. Plasmid permutation vectors to monitor DNA bending. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:10060. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.23.10060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brunelle A, Schleif RF. Missing contact probing of DNA-protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1987;84:6673–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maxam AM, Gilbert W. A new method for sequencing DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:560–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]