Abstract

Objectives: The primary purpose of this study was to determine the level of agitation that psychiatric patients exhibit upon arrival to the emergency department. The secondary purpose was to determine whether the level of agitation changed over time depending upon whether the patient was restrained or unrestrained.

Method: An observational study enrolling a convenience sample of 100 patients presenting with a psychiatric complaint was planned, in order to obtain 50 chemically and/or physically restrained and 50 unrestrained patients. The study was performed in summer 2004 in a community, inner-city, level 1 emergency department with 45,000 visits per year. The level of patient agitation was measured using the Agitated Behavior Scale (ABS) and the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) upon arrival and every 30 minutes over a 3-hour period. The inclusion criteria allowed entry of any patient who presented to the emergency department with a psychiatric complaint thought to be unrelated to physical illness. Patients who were restrained for nonbehavioral reasons or were medically unstable were excluded.

Results: 101 patients were enrolled in the study. Of that total, 53 patients were not restrained, 47 patients were restrained, and 1 had incomplete data. There were no differences in gender, race, or age between the 2 groups. Upon arrival, 2 of the 47 restrained patients were rated severely agitated on the ABS, and 13 of 47 restrained patients were rated combative on the RASS. There was a statistical difference (p = .01) between the groups on both scales from time 0 to time 90 minutes. Scores on the agitation scales decreased over time in both groups. One patient in the unrestrained group became unarousable during treatment.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated that patients who were restrained were more agitated than those who were not, and that agitation levels in both groups decreased over time. Some restrained patients did not meet combativeness or severe agitation criteria, suggesting either that use of other criteria is needed or that restraints were used inappropriately. Further study of the level of agitation and the effects of restraints is needed.

Psychiatric patients frequently present to emergency departments (EDs) across the country.1 Many of these patients are agitated, necessitating treatment for their agitation in the ED. In an unselected ED sample, some patients who exhibit agitation are intoxicated, delirious, and/or otherwise impaired. This study focuses on patients with psychiatric complaints.

The treatment for these agitated patients frequently includes physical restraint, chemical treatment, and seclusion. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health-care Organizations, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and many states have regulated the use of restraints and seclusion.

There are few studies regarding the level of agitation of undifferentiated psychiatric patients presenting to EDs. There is little information in the medical literature concerning the relationship between the level of patient agitation and restraint and seclusion use. Information exists for the use of restraint and seclusion of these agitated patients outside the ED. In a review of 13 published studies in adult inpatient psychiatric settings, a range of 1.9% to 66% of patients had a need for seclusion and restraint.2 Another study found an average of 2 restraints on 17% of patients in an acute medical unit.3 In psychiatric emergency rooms, the percentage of patients restrained (20%–25%) was significantly higher than in an inpatient facility (7%–20%).4–7 In other EDs, Lavoie et al.8 found that 25.2% of teaching hospitals restrained at least 1 patient per day. An average of 3.7% of all ED patients needed restraint and seclusion, or restraint alone.9

The relationship between the use of restraints and the level of agitation of psychiatric patients in the ED is unclear. It is thought that highly agitated patients are restrained in the ED to prevent further escalation and resultant violence. However, the relationship between the level of agitation and restraint use needs further definition. In order to better understand the relationship between restraint use and the level of agitation, we proposed this study. The secondary purpose was to determine the change in the level of agitation of the psychiatric patients in the ED over time.

METHOD

Participants

In order to determine if there was a significant difference between the groups, we planned to enroll 50 patients who were restrained and 50 who were not. The inclusion criteria allowed entry of patients of any age who presented to the emergency department with a psychiatric complaint thought to be unrelated to physical illness. Patients who were restrained for nonbehavioral reasons or were medically unstable were excluded from the study. Basic demographic information was obtained on each patient.

Procedures

This observational study was performed in a community, inner-city, level 1 teaching hospital ED with 45,000 visits per year, located in Chicago, Ill. The city's police department has designated the hospital as the referral site for psychiatric patients in the southwest side of the city.

During the summer of 2004, a convenience sample of patients who presented with psychiatric complaints to the ED when a research fellow from the Department of Emergency Medicine was available in the ED were enrolled in the study. None of the patients were restrained prior to arrival because neither the police nor paramedics are capable of behaviorally restraining patients. The emergency physicians independently determined the need for physical and/or chemical restraint without input from any study personnel. Since patients did not receive a psychiatric therapeutic plan in the ED, the use of medication would be considered chemical restraint rather than behavior modulation in the context of this study.7 Research fellows were responsible for completing an agitation checklist for each patient enrolled in the study. The psychiatric diagnoses used for the study were provided by the emergency physicians and may not reflect the DSM-IV criteria. Seclusion was not used at this hospital. The study was institutional review board–approved as exempt from consent due to the observational nature of the study. Data were collected without patient identifying information.

The patients were evaluated for their level of agitation at arrival and every 30 minutes for 3 hours. We chose 2 validated tests of agitation to determine the patients' level of agitation in the ED: the Agitated Behavior Scale (ABS) and the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS).10–14

The ABS is a scale with 14 items rated 1 (no agitation) to 4 (highest level of agitation) and the individual scores added together. Only 13 of the 14 items were used since the patients were not allowed to wander from the treatment area (item 7). The RASS is a 10-level scale based on observation of the patient's level of agitation or sedation, ranging from combativeness (+4) to unarousability (−5). These scales were chosen because of their ease of use and variable measure of sedation and agitation.

The data were input into an SPSS program for analysis (Version 10; SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Ill.). To analyze the data, the investigators grouped the scores into broader categories. The ABS scale was divided into no (< 22), mild (22–28), moderate (29–35), and severe (≥ 36) agitation, and the RASS was divided into agitated (+4 to +1), alert and calm (0), and sedated (−1 to −5).13,14 The groups were compared using the χ2, analysis of variance, and Pearson tests.

RESULTS

One hundred one patients were enrolled in the study. Of those patients, 53 were not restrained, and 47 were restrained. Although various elements in the data set were not completed, only 1 patient had significant incomplete data and was eliminated from consideration. There were no differences between the 2 groups in gender (χ2 = 5.79, df = 2, p = .12), race (χ2 = 7.22, df = 2, p = .30), age (χ2 = 2.73, df = 2, p = .59), or ED diagnosis (χ2 = 31.4, df = 2, p = .06).

All restrained patients were restrained within 15 minutes of arrival to the ED. Of the restrained patients, 21 were only physically restrained, 13 were chemically and physically restrained, and 13 were only chemically restrained. Lorazepam was the most frequently used medication (12), followed by other agents (5), olanzapine (3), and haloperidol and lorazepam (2). Among restrained patients with follow-up information, 15 of 27 patients were admitted, and 12 of 27 went home. Mania was the most frequent diagnosis (27 of 46 patients), followed by psychosis (9 of 46 patients) and depression (5 of 46 patients) (total Ns less than 47 due to missing data). The reason for restraint was violent behavior in 28 of 44 patients and agitation in 13 of 44 patients.

In the unrestrained group with follow-up information, 19 of the 36 patients went home, and 17 patients were admitted. The leading diagnosis in this unrestrained group was manic-depressive illness (17 of 47 patients), followed by depression (13 of 47 patients) and psychotic illness (12 of 47 patients) (total Ns less than 53 due to missing data). There were no statistical differences found between the groups for admission rates or diagnoses.

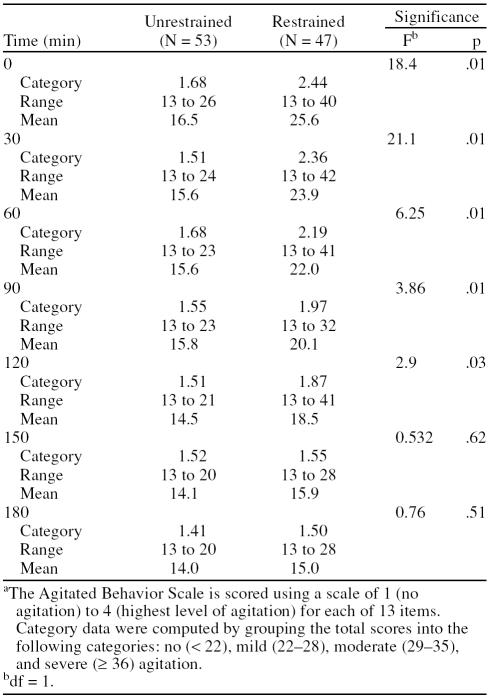

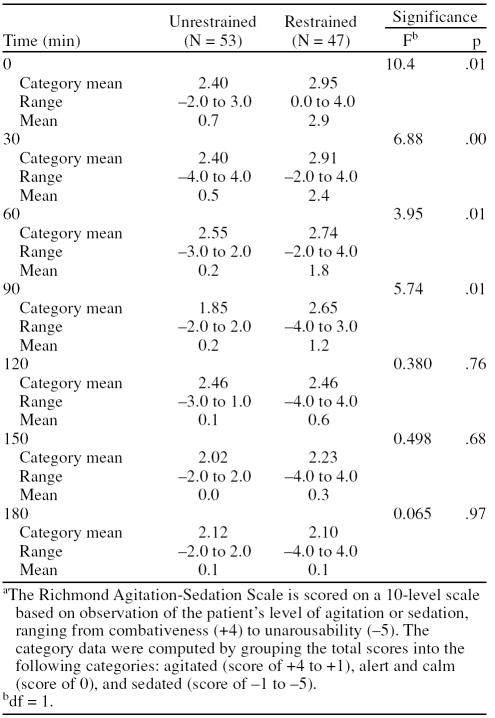

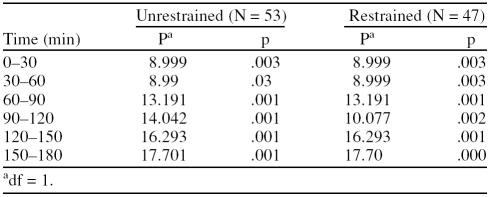

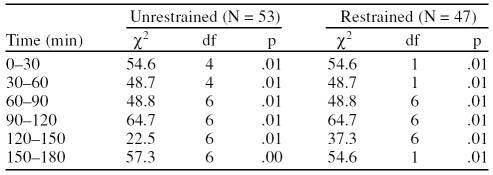

There was a statistical difference between the groups on both scales from time 0 to time 90 minutes (ABS: F = 18.4, df = 1, p = .01 [0 minutes] to F = 3.86, df = 1, p = .01 [90 minutes]; RASS: F = 10.4, df = 1, p = .01 [0 minutes] to F = 5.74, df = 1, p = .01 [90 minutes]) (Tables 1 and 2). The agitation scales decreased over time in both groups (ABS mean decreased from 16.5 to 14.0 in the unrestrained group and 26.5 to 15.0 in the restrained group, and RASS mean decreased from 0.7 to 0.1 in the unrestrained group and 2.9 to 0.1 in the restrained group) (Tables 1 and 2). Tables 3 and 4 show the statistical results for change over time in ABS and RASS scores.

Table 1.

Agitated Behavior Scale Scores Over Time for Unrestrained and Restrained Patientsa

Table 2.

Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale Scores Over Time for Unrestrained and Restrained Patientsa

Table 3.

Agitated Behavior Scale: Change Over Time

Table 4.

Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: Change Over Time

The RASS was used to assess patients who became unarousable, and only 1 patient in the unrestrained group became unarousable, at 30 minutes. No other patient in either group became unarousable throughout the period of observation. One unrestrained patient was judged as combative on the RASS at 30 minutes, but no other unrestrained patients were found to be combative during the evaluation period. Thirteen restrained patients were judged as combative upon presentation, 8 were judged as combative at 30 minutes, and 1 was judged as combative at 120, 150, and 180 minutes.

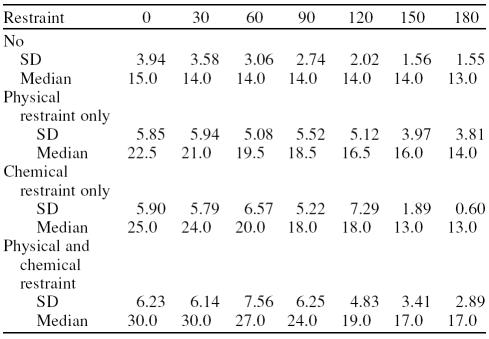

The ABS indicated that 2 patients in the restrained group and none in the unrestrained group reached the severely agitated category at time 0, and 0 or 1 restrained patient was in the severely agitated category during the rest of the observation period. On the other hand, the numbers of patients who were in the no agitation ABS category increased from time 0 to time 180 minutes, going from 15 to 45 in the restrained group and 39 to 50 in the unrestrained group. The standard deviation and median values for the ABS (Table 5) had less variation within each time period for unrestrained patients as compared with restrained patients. The same difference in variation was not seen using the RASS (Table 6). This finding indicates that the ABS would have placed in the restrained population some patients whom the RASS might have placed in the unrestrained population.

Table 5.

Agitated Behavior Scale Median and Standard Deviation Values in 30-Minute Increments

Table 6.

Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale Median and Standard Deviation Values in 30-Minute Increments

DISCUSSION

The agitation levels of unrestrained patients started low and remained low throughout the study on both scales. Restrained patients had higher agitation levels upon entering the ED.

Agitation levels remained significantly different between restrained and unrestrained patients at each time point during the first 2 of the 3-hour periods. The agitation levels of both groups decreased over time.

It is easy to understand the significance of the 15 patients who were restrained at presentation and had no agitation on the ABS scale. This finding was not sustained in the RASS, on which 13 of the restrained patients were found to be combative. Perhaps the patients were not properly assessed. The difference could be explained by the type of testing used. The RASS is a global rating with an anchor that includes combativeness, and the ABS is composed of 14 items, of which only 2 involve anger or threats. However, it is concerning that a number of restrained patients did not meet the criteria for combativeness or severe agitation on either scale.

Possible explanations for this finding include that inappropriate patients were restrained, or that the scales do not adequately reflect clinical decisions for restraints. The tools did not assess a patient's level of suicidal or homicidal potential. Perhaps the emergency staff was using other, unstudied criteria on which to base the decision to restrain a patient. As an example of such unstated criteria, an agitated patient brought to the emergency department by law enforcement in handcuffs for violent behavior would most likely be placed in restraints prior to assessment by the emergency physician.

Analogous to pain treatment, could the treatment of agitation using a measurement tool be more beneficial than the current “all-or-none” phenomenon, in which patients either need or do not need restraints? Few studies have measured the level of agitation a patient exhibits upon arrival to the emergency department. The natural history of an agitated patient without treatment has not been evaluated and would be an interesting topic for study.

Studies in the psychiatric literature found that restraint and seclusion use reduced the level of agitation.16 The medical literature offers limited information on the use of the agitation scales and testing in the emergency setting. We found no studies of the use of the RASS in emergency medicine. The uses of ABS in emergency medicine in a selected population were examined in 1 study,17 and the Overt Aggression Scale was used in a study in a para-medic system.18 Battaglia and others17 used the ABS to assess the differences seen with haloperidol, lorazepam, or both in the treatment of agitation. Patients had to score at least 5 on the 11 psychosis/anxiety items on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. The authors found that all treatment groups showed significant reduction in baseline scores over a 12-hour treatment phase. The scores began at a level of 40 for the patients to be enrolled in the study and were at a level of approximately 20 by 2 hours of therapy and continued at that level for 12 hours. The authors did not examine the effect of physical restraint, nor did they document how many patients received this intervention. In our study, few of the patients had an ABS score of 40 or greater.

The Overt Aggression Scale was used in a study by Mock et al.18 to measure the number of violence episodes encountered by emergency medical services personnel. In the Mock et al. study, the tools were used to determine a patient's risk of violence, rather than the patient's level of agitation.

On the basis of our conclusions, an argument could be made that a scale or assessment of the need for restraint or seclusion that better matches the indications for restraint and seclusion is needed. The chief indication for placing a patient in restraint or seclusion is prevention of harm to the patient or staff. Such a scale would take into account not only the level of agitation but also the probability of violence and elopement of patients with suicidal and homicidal potential.

Many procedures are performed in the acute care setting. For most of these procedures, we have some understanding of the effect of the procedure on the patient.19 This study demonstrated the level of agitation of patients evaluated in the acute care setting with and without restraints. In all procedures, one must understand the indications and contraindications. The procedural steps should be reviewed and technical aspects practiced. On the basis of the findings of this study, the procedural step to determine if a patient needs restraints is not well understood.

In retrospect, the study could be improved if a greater number of patients were enrolled in order to determine if there was a difference between patients restrained chemically, physically, and both chemically and physically. Stronger conclusions could be made if a protocol for the initiation of restraints were used instead of physician discretion.

Future study is needed in many areas on the basis of the findings of this study. The best, most humane means of modulating agitated behavior in not only psychiatric patients, but also demented or delirious patients, must be established. A multi-arm, randomized, prospective study to examine these topics would be valuable, albeit difficult to accomplish in the acute care setting. A better understanding of the rationale of treatment of the agitated patient is needed in order to determine whether these patients are being treated as part of a therapeutic plan or for staff convenience. It would be valuable to study regulatory compliance with requirements for restraints, such as determining the use of alternatives prior to restraints and the timely checking of vital signs.

Limitations

This study did not separate out chemical from physical restraint, somewhat limiting its usefulness. There is a difference of opinion between emergency physicians and psychiatrists concerning the use of the terminology of chemical restraints. Emergency physicians, who do not develop therapeutic plans, use the term in reference to medication that quickly induces calm behavior. Psychiatrists do not use this terminology; rather, medication is used as part of a therapeutic plan. A comparison of the level of agitation found with the different treatment modalities would provide better guidance to determine the best technique for reducing agitation.

The tools chosen to measure agitation also limited this study. Although the tools have been validated, their usefulness in the acute care setting has not. Modification of the ABS to 13 items may have biased the conclusions. Perhaps there are other tests that would have provided better information than those used in this study. The raters' agreement for each of the scales was not tested, and some of the variance may be attributable to lack of concordance among the raters. This study was limited by incomplete data collection for some of the patients on some of the inquiries. One serious potential bias of this study was observer bias, especially in the cases in which patients were immediately restrained upon presentation to the emergency department. Another limitation was that the emergency physicians did not utilize DSM-IV criteria in making their diagnoses. The groups were not homogeneous in terms of diagnoses or indications for restraints. The treating emergency physicians may have used other information, not identified in this study, to determine whether a patient needed to be restrained.

In summary, the obvious conclusions of the study were that patients who were restrained were more agitated and that the use of restraints decreased agitation over time. Unrestrained patients were less agitated and became less so over time. Dissecting the data further reveals that some patients who were restrained were not severely agitated, raising the question of the relationship of restraint use to agitation levels. Further study of the level of agitation and the effects of restraints, both chemical and physical, is needed.

Drug names: haloperidol (Haldol and others), lorazepam (Ativan and others), olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Footnotes

Dr. Zun has been a speakers/advisory board member for Eli Lilly. Dr. Downey reports no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

- Kunen S, Niederhauser R, and Smith PO. et al. Race disparities in psychiatric rates in emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005 73:116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PG, Gutheil TG, Wexler DB. Seclusion and restraint in 1985: a review and update. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1985;36:652–657. doi: 10.1176/ps.36.6.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins L, Boyko E, and Lane J. et al. Binding the elderly: a prospective study of the use of mechanical restraints in an acute care hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987 35:290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mion LC, Frengley JD, and Jakovcic SA. et al. A further exploration of the use of physical restraints in hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989 37:949–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frengley DM. Incidence of physical restraints on acute medical wards. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:565–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb05760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telintelo S, Kuhlman TL, Winger C. A study of the use of restraint in a psychiatric emergency room. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1983;34:164–165. doi: 10.1176/ps.34.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MH, Currier GW, and Hughes DH. et al. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: treatment of behavioral emergencies. Postgrad Med 2001 May:1–88; quiz 89–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie F, Carter GL, and Danzl DF. et al. Emergency department violence in United States teaching hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 1988 17:1227–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie FW. Consent, involuntary treatment, and the use of force in an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin WR. Evaluating and managing the violent patient. Ann Emerg Med. 1981;10:481–484. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(81)80282-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JD, Mysiw WJ. Agitation following traumatic head injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69:487–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JD. Development of a scale for assessment of agitation following traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1989;11:261–277. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogner JA, Corrigan JD, and Stange M. et al. Reliability of the Agitated Behavior Scale. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1999 14:91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogner JA, Corrigan JD, and Bode RK. et al. Rating scale analysis of the Agitated Behavior Scale. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2000 15:656–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, and Grap MJ. et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 166:1338–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WA. Restraint and seclusion: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1584–1591. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia J, Moss S, and Rush J. et al. Haloperidol, lorazepam, or both for psychotic agitation?: a multicenter, prospective, double blind, emergency department study. Am J Emerg Med. 1997 15:335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock EF, Wrenn KD, and Wright SW. et al. Prospective field study of violence in emergency medical services calls. Ann Emerg Med. 1998 32:33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao AK, Hedges JR. Competency and confidence: procedures in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:686–687. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.115530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]