An Introduction to Fibromyalgia and Its Related Disorders

Fibromyalgia, an illness characterized by chronic, widespread pain and tenderness,1 is estimated to affect about 5 million U.S. adults.2 Fibromyalgia was formerly classified as an inflammatory musculoskeletal disease but is now considered to be an illness that primarily affects the central nervous system.

Don L. Goldenberg, M.D., chaired the discussion and along with the faculty outlined the diagnosis, course, and current treatment of fibromyalgia and its related disorders. Laurence A. Bradley, Ph.D., reviewed factors that contribute to fibromyalgia and commonly cooccurring disorders. Lesley M. Arnold, M.D., focused on the relationship between chronic pain disorders like fibromyalgia and mood disorders. Jennifer M. Glass, Ph.D., discussed the effects of fibromyalgia on cognition. Specific pharmacologic treatment recommendations were given by Daniel J. Clauw, M.D., while Dr. Goldenberg concluded with a discussion of non-pharmacologic therapeutic options.

The spectrum of fibromyalgia ranges from mild symptomatology, requiring no medical attention, to severe, with disabling widespread pain and exhaustion. The progression from mild to severe symptoms is not well understood but does involve personal psychosocial factors. Therefore, primary care physicians should consider the psychosocial as well as the physiologic aspects of fibromyalgia and its related disorders to provide patients with a comprehensive treatment plan that includes pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment options.

Pathophysiologic Mechanisms of Fibromyalgia and Its Related Disorders

Understanding the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia and cooccurring disorders may help clinicians provide the most appropriate treatment to their patients, began Dr. Bradley. The pathophysiology of fibromyalgia involves family and genetic factors, environmental triggers, and abnormalities in the neuroendocrine and autonomic nervous systems. Many of these risk factors are similar to those for other illnesses characterized by recurrent or persistent pain and affective distress that are frequently comorbid with fibromyalgia, such as irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, tension or migraine headaches, temporomandibular disorder, and major depressive disorder (MDD).3 Fibromyalgia may also be comorbid with hypothyroidism4 and chronic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.5

Biological and Genetic Factors

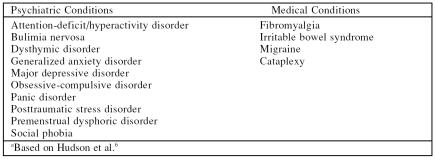

Dr. Bradley explained that fibromyalgia may be part of a group of affective spectrum disorders (ASD). The ASD hypothesis proposed by Hudson and colleagues6 suggests that this group includes, but is not limited to, 10 psychiatric and 4 medical disorders (Table 1) that share 1 or more physiologic abnormalities important to their etiology. These include inherited factors that may contribute to enhanced pain sensitivity, diminished pain inhibitory function, or mood disorders. Studies6,7 of patients, as well as their first-degree relatives, with fibromyalgia or rheumatoid arthritis have provided evidence to support the ASD hypothesis. For example, Arnold et al.7 reported that the first-degree relatives of patients with fibromyalgia, compared with those of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, more frequently met diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia or MDD and exhibited a greater number of sensitive tender points (i.e., enhanced pain sensitivity). Hudson et al.6 further examined data from this family study and found that fibromyalgia co-aggregated with 1 or more other forms of ASD whether mood disorders were included (p = .004) or not (p = .012). These findings suggest that, consistent with the ASD hypothesis, (1) heritable as well as environmental factors may contribute to family aggregation of pain sensitivity in fibromyalgia, (2) fibromyalgia co-aggregates with other affective spectrum disorders, and (3) these disorders may share heritable physiologic abnormalities.

Table 1.

Affective Spectrum Disorders Hypothesized to Share Common Physiologic Abnormalitiesa

One heritable factor that may be shared by several affective spectrum disorders is a single nucleotide polymorphism in the regulatory region of the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene.8 This polymorphism is found more frequently in patients with fibromyalgia9,10 and in patients with MDD11 compared with healthy controls. There is also some evidence that it is found more frequently among patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).12,13 This polymorphism, then, may represent a heritable risk factor for the development of these affective spectrum disorders. However, there currently are no data regarding the frequency of this polymorphism among first-degree relatives of patients with fibromyalgia or IBS or the extent to which it may be associated with enhanced pain sensitivity among patients and their family members.

Environmental Triggers

Dr. Bradley described environmental triggers that may also be involved in the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia, especially in combination with other risk factors. These triggers include mechanical or physical trauma or injury and psychosocial stressors.14–16

A number of variables involving manual work, such as heavy lifting, repetitive motions, or squatting for extended periods of time, have been significantly associated with the occurrence of several musculoskeletal pain conditions, including widespread pain.15 But workers' reports of dissatisfaction with the amount of psychosocial support they received at their job sites as well as descriptions of work as monotonous also were associated with a higher risk of onset of widespread pain. Several other environmental factors such as working in hot conditions also increased the risk, although not significantly, of developing widespread pain.

Exposure to brief psychosocial stressors also may affect individuals perceptions of pain associated with fibromyalgia. Dr. Bradley cited a study16 of women with fibromyalgia or osteoarthritis. Following exposure to a negative mood induction procedure (i.e., reading sad text) and a psychosocial stressor, (i.e., discussing a stressful life event), women with fibromyalgia reported greater increases in pain severity than did women with osteoarthritis. Even during the post-stressor recovery period, pain severity ratings remained elevated in the women with fibromyalgia. However, exposure to a neutral mood induction procedure (i.e., relaxation) prior to the psychosocial stressor did not alter the pain severity ratings of women with fibromyalgia or knee osteoarthritis. These findings suggest that, although repetitive exposure to psychosocial stressors in the work-place increases the risk of onset of widespread pain, both negative mood and exposure to psychosocial stressors are required to alter perceptions of pain severity among patients with fibromyalgia.

Neuroendocrine Abnormalities

Dr. Bradley stated that fibromyalgia is generally considered to be a stress-related disorder characterized by abnormal functioning in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, such as the inability to suppress cortisol, a neuroendocrine abnormality that has also been found in patients with psychiatric disorders. Patients with fibromyalgia tend to exhibit higher peak and trough levels of cortisol than patients with rheumatoid arthritis.17 These patients also display a diminished response to an ovine corticotropin-releasing hormone that typically evokes a substantial stress response in healthy individuals.18

Autonomic Nervous System Abnormalities

Abnormalities are also present in the function of the autonomic nervous system of patients with fibromyalgia. These abnormalities include decreased microcirculatory vasoconstriction,19 increased hypotension,20 variations in heart rate,21 and sleep disturbance.22,23 Dr. Bradley noted that heart rate variability in fibromyalgia patients may be different in men and women,22,24 and that diminished heart rate variability in patients with fibromyalgia may be due to an abnormal chronobiology that may also contribute to sleep disturbance and fatigue.21 Dr. Bradley explained that fibromyalgia is often associated with sleep disturbances, such as non-restorative sleep, insomnia, early morning awakening, and poor quality of sleep.23 Moreover, sleep disturbance may contribute to pain experienced by patients with fibromyalgia through reduced production of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor that are necessary for repairing muscle microtrauma.25

Enhanced Pain Perception

Patients with fibromyalgia show enhanced sensitivity to a wide array of stimuli. Carli et al.26 studied pain sensitivity to 5 sensory testing tasks and found that patients with fibromyalgia showed lower pain thresholds than healthy controls on all 5 tests. In contrast, patients with multiregional pain or widespread pain displayed enhanced pain sensitivity to 1 to 3 of the stimulation sources.26

Dr. Bradley stated that central sensitization may underlie the enhanced sensitivity to low-intensity stimuli that is exhibited by patients with fibromyalgia.27,28 However, in both animal and human models of central sensitization, the stimulus is identified (e.g., nerve injury), and pain sensitivity is reduced if the source of sensory input is eliminated. In contrast, among patients with fibromyalgia, the source of sensory input remains unknown. For this reason, most fibromyalgia researchers refer to central augmentation of sensory input rather than central sensitization when discussing the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia.

Recent documentation of stimulusevoked changes in brain activity using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has illustrated the phenomenon of central augmentation of sensory input among patients with fibromyalgia. For example, patients with fibromyalgia reported moderate levels of pain intensity (i.e., 11 on a 20-point scale) at about one-half the stimulus intensity required to evoke the same response in healthy persons. Nevertheless, both patients and healthy individuals show significant increases in functional brain activity in the same brain regions in response to these disparate stimulus intensities.29 The fMRI findings, then, strongly suggest that enhanced pain sensitivity among patients with fibromyalgia is due to central augmentation of sensory input to the brain rather than somatization or a similar tendency to report pain or other unpleasant perceptions in response to low intensity sensory input.

Neuroimaging procedures are also being used to document alterations in brain inhibitory function of patients with fibromyalgia. For example, Wood et al.30 used ligand positron emission tomography (PET) to compare dopamine receptor availability in healthy controls and patients with fibromyalgia. In response to stimulation that produced pain in the anterior tibialis muscle, the patients reported higher levels of pain intensity than the healthy controls. However, only the healthy controls exhibited significant reductions in binding potential at dopamine receptors in basal ganglia structures. In other words, only healthy persons showed evidence of endogenous opioid release in brain regions that are involved in pain processing and are highly innervated by dopamine receptors. These findings suggest that both central augmentation of sensory input and diminished function of central pain inhibitory functions contribute to the abnormal pain sensitivity and persistent pain experienced by patients with fibromyalgia.

Conclusion

Dr. Bradley concluded that factors that contribute to the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia include biologic and genetic influences, environmental triggers, and abnormal function of the neuroendocrine and autonomic nervous systems. These factors are frequently shared by persons with disorders that co-occur with fibromyalgia, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and MDD. Enhanced pain sensitivity occurs not only in patients with fibromyalgia but also more frequently in their first-degree relatives than in the relatives of both healthy people and persons with other painful illnesses. Both central augmentation of sensory input and deficits in central pain inhibitory mechanisms appear to contribute to enhanced pain sensitivity in persons with fibromyalgia.

Management of Fibromyalgia and Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders

Depressive and anxiety symptoms are common and frequently severe in patients with fibromyalgia.31 Because, as Dr. Bradley described, fibromyalgia may share underlying pathophysiologic links with mood and anxiety disorders, Dr. Arnold recommended that patients with fibromyalgia be routinely evaluated for the presence of psychiatric comorbidity.

Impact of Psychiatric Comorbidity on Fibromyalgia

The presence of psychiatric symptoms has a profound impact on the severity and the course of fibromyalgia. High levels of depression and anxiety in patients with fibromyalgia have been found to be associated with more physical symptoms and poorer functioning than low levels of depression and anxiety.31 In fact, the presence of psychological symptoms in these patients is a predictor of persistent pain.32 Therefore, in treating patients with fibromyalgia, identifying and addressing psychiatric comorbidity may improve the long-term outcome of patients.

Clinical Presentations

Although only widespread pain and tenderness are included in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria,1 Dr. Arnold noted that several other symptom domains commonly occur in patients with fibromyalgia, such as fatigue, sleep disturbance, morning stiffness, paresthesias, headache, and depressive and anxiety symptoms.33 Other clinical features of fibromyalgia include cognitive problems, such as trouble concentrating, forgetfulness, and disorganized thinking,33 addressed later by Dr. Glass.

A structured interview was designed by Pope and Hudson34 to help clinicians diagnose fibromyalgia. The interview requires widespread pain for 3 months or longer, like the ACR criteria.1 However, the interview allows the clinician to either conduct the ACR tender point exam or collect at least 4 other commonly reported symptoms (Table 2). The clinician must also rule out other systemic conditions that might be contributing to the patient's symptoms.

Table 2.

Criteria for Fibromyalgiaa

Treating Fibromyalgia in the Presence of Psychiatric Symptoms

The treatment of fibromyalgia commonly includes the use of antidepressant medications, addressed later by Dr. Clauw. The use of antidepressant medication, said Dr. Arnold, is especially useful in patients with comorbid mood and anxiety symptoms. The possibility of a common pathophysiologic link between mood disorders and fibromyalgia6 suggests why these agents may affect both mood and pain.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), such as amitriptyline, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as venlafaxine,35 milnacipran,36 or duloxetine,37,38 may have a therapeutic effect on pain that is independent of their effects on mood as a result of their serotonin- and nor-epinephrine-mediated effects on the descending pain-inhibitory pathways in the brain and spinal cord.39 Medications with both serotonin and norepinephrine activity may have more consistent benefits than other antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), in the relief of persistent pain associated with chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia.39

Comorbid MDD or anxiety

Dr. Arnold stated that, during evaluation of patients with fibromyalgia, determining whether they have a current comorbid mood disorder is important, as well as screening for a past mood disorder. If a patient has a history of MDD, an SNRI may be preferable to an SSRI because of the more consistent effect of SNRIs on pain reduction.

When using antidepressants to treat patients with fibromyalgia, an adequate therapeutic dosage should be tried for an adequate duration (about 4–6 weeks) to allow for a response. If the patient does not fully respond, the clinician should switch to a different antidepressant or add another agent to the antidepressant. One combination of medications that has been found effective is an SSRI and a TCA (fluoxetine and amitriptyline).40 However, Dr. Arnold cautioned that some SSRIs and SNRIs may elevate blood TCA levels, so adverse drug interactions should be carefully monitored. Another effective combination may be an antidepressant and an anticonvulsant medication such as gabapentin or pregabalin. Pregabalin is currently the only agent approved for the treatment of fibromyalgia by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). More study of the treatment of fibromyalgia and comorbid MDD is needed.

In patients with fibromyalgia and either current or lifetime anxiety disorders, antidepressants are potentially effective for both the painful symptoms of fibromyalgia and the anxiety symptoms. Dr. Arnold noted that pregabalin and gabapentin also have anxiolytic properties.41

Comorbid bipolar disorder

The options for treating fibromyalgia and comorbid bipolar disorder may be more limited because of the dearth of available studies on bipolar disorder in patients with fibromyalgia. If antidepressants are used to manage pain in patients with fibromyalgia and co-occurring bipolar disorder, Dr. Arnold warned that these agents should be used in combination with mood stabilizers to lessen the patients' risk of switching to a manic phase and to avoid the induction of rapid cycling. Patients with type II bipolar disorder may respond to low doses of antidepressant monotherapy, but they must be observed carefully for development of mood instability.3 Gabapentin or pregabalin are alternatives to antidepressants in the treatment of comorbid bipolar disorder and fibromyalgia but, like antidepressants, should also be used in combination with well-established mood stabilizers.

Comorbid sleep disorders

Sleep disorders are common in patients with fibromyalgia. One treatment option, Dr. Arnold suggested, is to use a sedating agent at bedtime. Studies42,43 of the short-term treatment of fibromyalgia with non-benzodiazepine sedatives, such as zolpidem and zopiclone, have shown benefits for sleep and daytime energy, but not for pain. Therefore, they have limited usefulness as monotherapy in patients with fibromyalgia, and there are no data on their long-term use in fibromyalgia.

An alternative to the sedating agents is prescribing TCAs, such as amitriptyline at a dose of between 10 mg and 25 mg at bedtime.44 This strategy can be used as monotherapy or as adjunctive treatment. Gabapentin and pregabalin also have sedative effects and have demonstrated an increase in sleep quality and enhanced slow-wave sleep.45–48

Nonpharmacologic Treatment Options

Dr. Arnold described nonpharmacologic treatments of fibromyalgia, which include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), education, and aerobic exercise, addressed later by Dr. Goldenberg. Cognitive-behavioral therapy has demonstrated positive effects on patients' ability to cope with pain associated with fibromyalgia and feelings of control over pain, although these effects were not superior to those produced by education,49 which suggests that education itself can be therapeutic. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is also an effective treatment for mood and anxiety disorders.50,51 Dr. Arnold stated that evidence also supports the use of aerobic exercise for the treatment of fibromyalgia52 and for the treatment of mild to moderate depression.53

Stepwise Treatment Plan

Comorbid mood and anxiety disorders in patients with fibromyalgia can present diagnostic dilemmas and can negatively impact the course of fibromyalgia. The presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders may require additional pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments. Therefore, Dr. Arnold reviewed a stepwise treatment plan (Figure 1).54 Once a diagnosis of fibromyalgia is confirmed and comorbid disorders have been identified, a clinician should educate the patient and begin treatment with evidence-based medications and appropriate nonpharmacologic treatments.

Figure 1.

Stepwise Treatment for Fibromyalgiaa

Conclusion

Dr. Arnold stressed the importance of obtaining a thorough patient and family history in patients with fibromyalgia, paying particular attention to reports of mood or anxiety disorders. Using medications to treat fibromyalgia as well as comorbid psychiatric disorders and incorporating appropriate nonpharmacologic therapies should optimize patients' overall outcomes.

Fibromyalgia and Cognition

Fibrofog is a term coined by patient support groups to describe cognitive complaints associated with fibromyalgia. Dr. Glass explained that patients with fibromyalgia experience a decrease in memory, loss of vocabulary, and a lack of concentration, which are exacerbated in stressful work environments. She reported that her patients have often complained that the cognitive symptoms of fibromyalgia were more disturbing than the physical symptoms.

Self-Reported Cognitive Problems

Clinical observations of cognitive problems in fibromyalgia patients were corroborated by a study55 of 100 women with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Of the women sampled, 95% reported concentration difficulties and 93% reported failing memory. In a survey of more than 2500 people with fibromyalgia,56 respondents reported that concentration and memory were the most common problems after pain, fatigue, muscle tension or stiffness, and sleep problems. Dr. Glass noted that fibromyalgia patients have more self-reported cognitive problems than patients with other rheumatic disorders.57 Additionally, fibromyalgia patients report lower memory capacity and more deterioration in memory over time compared with 2 healthy control groups (one of which was 20 years older than the patient group).58 Fibromyalgia patients also reported having less control over memory function (self-efficacy) and higher anxiety about memory performance than age-matched controls, although they were more motivated and reported using more strategies to boost their memory performance.58

Objective Measures of Cognitive Function

Objective measures of cognitive function have shown differences between fibromyalgia patients and controls, particularly with memory and attention.59,60

Memory

Short-term memory, episodic long-term memory, and semantic memory access are particularly troublesome for patients with fibromyalgia. Working memory combines short-term memory (memory of less than about 30 seconds) with other mental processes for tasks such as mental arithmetic. Episodic long-term memory is the ability to remember particular episodes, such as items on a grocery list or personal experiences. Semantic memory involves facts and knowledge about the world. Dr. Glass reported that objective tests have revealed that the level of impairment in working memory, episodic long-term memory (free recall), and semantic memory (verbal fluency) in fibromyalgia patients mimics about 20 years of aging.61

Attention

Dr. Glass explained that results of attention tests in patients with fibromyalgia are consistent with those of working memory tests because the attention tests require people to store some information for a short period of time and also process distracting information. Studies60,62 examining attentional functioning in patients with fibromyalgia reported that they scored substantially worse than pain-free controls in selective attention and auditory-verbal working memory. Dividing attention had costs for both controls and fibromyalgia patients, but the greatest cost incurred was among the fibromyalgia patients when attention was divided during both the learning and recall phases of testing. These results may explain why fibromyalgia patients report poor memory performance in real-world environments.63 Dr. Glass said that the cost in accuracy on attention tests was greatest when fibromyalgia patients had to switch between complex rules.64 These results confirm patients' accounts that they are most aware of their cognitive problems when tasks are difficult, multiple tasks are required, and there is a lot of distraction.

Factors That Contribute to Fibrofog

Several factors may contribute to cognitive problems in patients with fibromyalgia, said Dr. Glass. These factors include comorbid depression, sleep problems, neuroendocrine abnormalities, pain, and central augmentation of sensory input.

Psychiatric comorbidity

Dr. Glass noted that while other researchers65,66 have reported a correlation between depressive symptoms and cognitive function in patients with fibromyalgia, she and her colleagues61 did not find a correlation between psychiatric symptoms and results on cognitive tests. She said that although depression or anxiety could be related to cognitive function in some fibromyalgia patients, these symptoms do not explain all of their memory and attention problems.

Sleep disturbances

Fibromyalgia patients usually have sleep problems and, even in healthy subjects, insufficient sleep impairs learning and memory.67 However, Dr. Glass's research61 did not produce any correlation between sleep and cognitive performance. As is the case with depression, poor sleep undoubtedly contributes to some of the cognitive difficulties of fibromyalgia patients but is not a sole cause.

Neuroendocrine abnormalities

Dr. Glass stated that stress-level cortisol doses have been shown to decrease memory function in healthy adults,68 and elevated levels of cortisol were associated with lower performance on cognitive tests in those with Cushing's disease.69 Conversely, other research70 found that higher salivary cortisol levels correlated with better visual-spatial memory. Neuroendocrine function seems to have some effect on memory function, but exactly how this may affect fibromyalgia patients is still unclear.

Pain

Chronic pain has been associated with impairment in attention71 and may contribute to fibrofog. Cognitive function has been correlated with both self-reported and evoked pain in fibromyalgia,61,72 so pain likely contributes to the cognitive problems experienced by fibromyalgia patients, according to Dr. Glass.

Central augmentation of sensory input

Central processing abnormalities may interfere with the ability to maintain focus.29 Dr. Glass stated that enhanced processing of sensory signals may lead to increased distractibility.

Tests Versus Self-Report in Clinical Practice

Dr. Glass said that physicians often ask how cognitive function in fibromyalgia patients should be measured in clinical practice. Her answer was that, generally, neuropsychological and cognitive tests are extensive and time-consuming and may not be feasible in practice. Many of the tests that are sensitive to the problems that fibromyalgia patients experience are not standardized, and some of the standard neuropsychological tests may miss the attention difficulties of fibromyalgia patients. No quick and easy test of cognitive function in fibromyalgia patients exists yet. Dr. Glass suggested that, in the clinic, self-report may be the best and quickest measure of cognitive problems in fibromyalgia patients. Performance on an objective memory recall task correlated with fibromyalgia patients' perceived capacity, achievement motivation, and self-efficacy.58

Conclusion

Research using objective tests has verified fibromyalgia patients' self-report of cognitive difficulties. As no simple and quick test exists for evaluating cognitive problems in patients with fibromyalgia, patient self-report can be used in clinical practice. More research is needed to delineate the exact nature of cognitive difficulties. Uncovering causes of cognitive impairment in fibromyalgia patients may lead to treatments that will improve cognitive function.

Pharmacotherapy for Patients With Fibromyalgia

Pharmacotherapy plays an integral role in the management of fibromyalgia, but, Dr. Clauw stressed, the most effective treatment approach combines pharmacotherapy with adjunctive non-pharmacologic programs. Dr. Clauw stated that 3 classes of drugs have strong evidence supporting their efficacy in fibromyalgia: TCAs, SNRIs, and α2δ ligands. Other drugs that may be efficacious, although the evidence is less compelling, include tramadol, the older SSRIs, γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), and dopamine agonists. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids are probably not effective in the treatment of fibromyalgia, despite their routine use. Benzodiazepines, hypnotics, and sedatives also have not been shown to be efficacious in treating fibromyalgia.

Drugs With Strong Evidence of Efficacy

TCAs

TCAs have been found to be efficacious in the treatment of fibromyalgic pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances44 but are associated with some safety concerns. Adverse events include dry mouth, sedation, weight gain, urinary retention, constipation, and tachycardia.73 Patients with cardiac problems or narrow-angle glaucoma should not take TCAs. Elderly patients should not take amitriptyline due to the risk of anticholinergic side effects.

To minimize the incidence of side effects associated with TCAs, Dr. Clauw suggested that a low dose should be used at the beginning of therapy, and the dose should be titrated up slowly.74 For example, amitripty-line can be started at 10 mg/day taken several hours before bedtime and be titrated by about 10 to 25 mg per week to a maximum of 70 or 80 mg/day or the highest therapeutic dose that the patient will tolerate.73 Cyclobenzaprine should usually be started at 5 mg several hours before bedtime and escalated up to 20 mg/day or the maximally tolerated dose.75

SNRIs

SNRIs tend to increase nor-epinephrine and serotonin without producing the cardiac side effects associated with TCAs.74 Dr. Clauw reported that both duloxetine37 and milnacipran76 were shown to diminish fibromyalgic pain as well as fatigue, stiffness, and function. Like with TCAs, duloxetine and milnacipran can sometimes be effective for treating fibromyalgia at or below the doses recommended for depression when tested in patients with fibromyalgia (60–120 mg/day for duloxetine37 and 100–200 mg/day for milnacipran76), giving these dual reuptake inhibitors the added advantage of treating the comorbid depression that sometimes exists in individuals with fibromyalgia. Side effects associated with both drugs include constipation, nausea, palpitations, dizziness, insomnia, and dry mouth.73 Again, Dr. Clauw recommended slow dose titration because side effects are often most pronounced when the drug is first administered and with dose escalation. Taking this class of drugs with food will also aid gastrointestinal tolerability.

α2δ Ligands

The α2δ ligands gabapentin46 and pregabalin45 have similar, if not identical, mechanisms of action, and both drugs have demonstrated efficacy in fibromyalgia treatment. Gabapentin was effective when used with a dose range of 1200 to 2400 mg/day.46 Both 300 mg and 450 mg/day of pregabalin have been approved by the FDA for use in fibromyalgia. According to Dr. Clauw, these drugs are often better tolerated if a higher percentage of the daily dose is taken at bedtime, such as 600 mg of gabapentin in the morning and 1200 mg at night. Similarly, pregabalin could be divided into 100 mg in the morning and 200 mg at night or 150 mg in the morning and 300 mg at night. Adverse events may include fatigue, sedation, nausea, drowsiness, dizziness, and weight gain.73

Possibly Effective Treatment Options

Other drugs, such as the dualreuptake inhibitor/atypical opioid tramadol,77 the older SSRIs such as fluoxetine,40 GHB,78 and the dopamine agonist pramipexole79 appear to be beneficial in fibromyalgia despite less compelling evidence. Tramadol seems to be safe and effective for most patients as both monotherapy77 and in combination with acetaminophen.80 Dr. Clauw mentioned that the side effect profile for combined tramadol/acetaminophen includes nausea, dizziness, headache, pruritus, constipation, and somnolence, which is similar to that of tramadol as monotherapy.81 Older SSRIs such as fluoxetine40 and paroxetine74 have been found effective in some patients with fibromyalgia either as monotherapy82,83 or in combination with TCAs.40 Fluoxetine monotherapy84 and cyclobenzaprine monotherapy85 have been efficacious for certain outcome measures in fibromyalgia, but the combination of fluoxetine and cyclobenzaprine demonstrated the most effective results.85 Amitriptyline is also effective as monotherapy treatment for fibromyalgia, but the combination with fluoxetine was more effective than either medication on its own.40 Fluoxetine and paroxetine are often dosed at 10 to 20 mg/day when used for depression, but in fibromyalgia higher doses might be required, necessitating doses as high as 80 mg/day.73 In contrast to TCAs, higher doses of SSRIs are more useful as analgesics, again because of the enhanced noradrenergic properties at higher doses.39 The most common side effects for these SSRIs include nausea, sedation, headache, weight gain, decreased libido, and sexual dysfunction.73

Dr. Clauw described other agents with mixed reports of efficacy in treating fibromyalgia. The newer SSRI citalopram appears to be less effective in the fibromyalgic population,86 perhaps because the older drugs have noradrenergic activity, especially at higher doses.39 γ-Hydroxybutyrate may be efficacious in reducing pain and fatigue but is most effective in reducing sleep abnormalities associated with fibromyalgia78; however, GHB is a scheduled substance because of its abuse potential. Pramipexole has also been shown to be moderately effective in reducing pain and fatigue while improving function and global status for patients with fibromyalgia who were disabled and/or required narcotic analgesia.79 Dr. Clauw noted that pramipexole was associated with weight loss and transient anxiety.

Drugs to Avoid

Dr. Clauw has observed in routine clinical practice that NSAIDs and opioids are not particularly efficacious, unless the individual has a comorbid peripheral pain condition, but nevertheless these drugs are often used as treatment for fibromyalgia. These analgesics can be quite helpful in alleviating acute pain and so-called peripheral or nociceptive pain, such as that which occurs with osteoarthritis or tendonitis, but they are not nearly as efficacious for central or neuropathic pain, such as that which occurs in fibromyalgia.74 An additional risk with opioid therapy is the development of a substance use disorder.87 Likewise, benzodiazepines, hypnotics, and sedatives should be avoided, as they have not been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of fibromyalgia.

Integrated Treatment Approach

Dr. Clauw emphasized the importance of approaching the treatment of fibromyalgia and other chronic pain syndromes with a rehabilitation model rather than a classic biomedical model, integrating pharmacologic treatment with nonpharmacologic therapies. Pharmacologic therapies primarily address pain or pain processing, whereas nonpharmacologic therapies address the functional consequences of the pain, such as disability. Strong evidence supports education, aerobic exercise, and CBT as effective treatments for patients with fibromyalgia,88 addressed later by Dr. Goldenberg. Strength training89 and hypnotherapy90 may provide some benefit. Dr. Clauw mentioned that tender point injections, despite routine clinical use, have not been shown to be effective in the treatment of fibromyalgia.74

Conclusion

Tricyclic antidepressants often can lead to global improvements in pain, fatigue, sleep, and other symptoms of fibromyalgia. If tricyclic monotherapy is ineffective or intolerable, it should be augmented or replaced with SNRIs and/or α2δ ligands. Dr. Clauw stated that, in many cases, all 3 of these classes of drugs can be used together, with clear salutary effects from each. Some combination of the effective nonpharmacologic therapies should also be implemented. Effective use of an integrated treatment plan will have a significant, positive impact on the lives of patients with fibromyalgia.

Multidisciplinary Modalities in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia

Dr. Goldenberg asserted that a diagnosis of fibromyalgia should be enabling rather than disabling, although this is an area of controversy.91 Some people believe that fibromyalgia symptoms, such as widespread pain and fatigue, are a part of daily life, and pathologizing them may increase symptomatology, health care utilization, or anxiety. Dr. Goldenberg stated the diagnosis is only harmful when the patient does not receive appropriate information about the condition. With any chronic symptomatology, labeling the symptoms is reassuring, and patients typically stop undergoing multiple diagnostic tests with the fear that something is being missed.

Once the patient has been diagnosed, treatment can begin. Dr. Goldenberg echoed Dr. Clauw's assertion that the most effect treatment regimens integrate pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities that are appropriate to the patient. Dr. Goldenberg described nonpharmacologic treatments in greater detail.

Nonpharmacologic Treatments

Several types of nonpharmacologic strategies for treating fibromyalgia have been examined, but many studies tested more than 1 strategy at a time and/or were not controlled. However, patient education, exercise, and CBT have individually or in combination been found to improve mood, physical functioning, sleep, and self-efficacy and to lessen fatigue and pain.

Education

Education has been found to improve self-efficacy and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia.92 However, finding enough time to properly educate patients with fibromyalgia is challenging for clinicians. Dr. Goldenberg's time-saving method is to schedule several patients with fibromyalgia on the same day so that he and/or his staff can lead a group discussion that includes both patients and family members. The small-group format with a didactic lecture followed by questions and discussion is recommended.93 After the group meeting, the clinician should allow any patients who want one-on-one treatment advice to ask more questions. The group setting helps patients learn from their peers, and often they establish contacts and bond with other patients.

Common patient questions include the following:

What is wrong with me?

Why do I hurt all over?

Why am I so exhausted?

Why won't anyone believe me?

How did I get fibromyalgia?

How is fibromyalgia treated?

When will fibromyalgia go away?

Dr. Goldenberg recommended addressing these questions by discussing potential pathophysiologic mechanisms in fibromyalgia using a biopsychological model. The clinician must dispel the notion that absence of organic disease means the symptoms are psychogenic.

Dr. Goldenberg recommended avoiding structural or causation labels. Structural labels used for neck pain, such as torticollis and occipital neuralgia, or for back pain, such as sacroiliac dysfunction, do not have any credence in pathophysiologic models of fibromyalgia. Rather, the appropriate terms fibromyalgia or chronic widespread pain do not explain illness based on structure. Patients should know that they do not have structural abnormalities, nor is fibromyalgia typically a prodromal phase of another disease. Also, using labels linked to possible causes, such as posttraumatic fibromyalgia, postinfectious fibromyalgia, or environmental fibromyalgia, should be avoided unless a clear link exists between the symptoms and the cause, which typically is not the case.

Describing the prognosis and the clinical course is important. Dr. Goldenberg recommending telling patients that, although fibromyalgia is a chronic disorder, a waxing and waning course is typical. The condition can improve but only with hard work and self-management on the patient's part. A problem that clinicians face while advising patients with fibromyalgia is patient access to pervasive misinformation in commercial books and on the Internet. He recommended that clinicians provide patients with trustworthy literature and Web site addresses.

Exercise

Exercise has been shown to be an effective intervention in fibromyalgia. Patients demonstrated improvement not only in walking distances but also in Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire scores, anxiety and depression scale scores, and self-efficacy following an exercise regimen of three 30-minute exercise classes per week for 23 weeks, while patients who did not participate in the exercise regiment declined.94

Because many patients with fibromyalgia are sedentary, Dr. Goldenberg said that the word exercise should be replaced with activity in the early stages of treatment. Patients should be instructed to avoid inactivity and push for gradual cardiovascular fitness, stretching, and strengthening. Patients should be warned that their pain might initially worsen as physical exertion increases. A general goal is to achieve moderate exercise levels, such as 60% to 75% of their age-adjusted maximum heart rate at least 3 times weekly for at least 30 to 40 minutes.

CBT

Cognitive-behavioral therapy has been shown to be effective in the management of fibromyalgia.95 Cognitive-behavioral therapy not only improves mood and function but also decreases pain and fatigue.96 Group or individual CBT sessions may be used. Dr. Goldenberg explained that CBT can address bad habits that patients may have developed to manage their illness that actually worsen it, such as trying to do too much on a day they feel well and then paying the consequences for their overactivity the next day. Balancing their daily activity level can have a salutary effect on patients' overall symptomatology.

Other Nonpharmacologic Therapies

Some complementary and alternative therapies, including acupuncture,97 trigger point injections,98 manual treatment including chiropractic99 and massage100 therapies, hypnotherapy,90 biofeedback,101 taichi,102 and yoga,103 may be effective treatments for some patients with fibromyalgia. Dr. Goldenberg stressed that the evidence is tentative and more research is needed.

Conclusion

Dr. Goldenberg concluded that successfully managing the physical and mental symptoms of patients with fibromyalgia and related disorders requires integrated pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapy that is tailored to a patient's needs. While many treatments have some data showing efficacy when used alone, multidisciplinary strategies generally provide better outcomes than monotherapies.104 Deciding which clinician should take charge in the multi-disciplinary treatment of fibromyalgia is necessary for optimal patient care.

Drug names: acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet and others), citalopram (Celexa and others), cyclobenzaprine (Amrix, Flexeril, and others), duloxetine (Cymbalta), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), gabapentin (Neurontin and others), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, and others), pramipexole (Mirapex and others), pregabalin (Lyrica), tramadol (Ultram and others), venlafaxine (Effexor and others), zolpidem (Ambien and others), zopiclone (Lunesta),

Disclosure of off-label usage: The chair has determined that, to the best of his knowledge, citalopram, cyclobenzaprine, duloxetine, fluoxetine, gabapentin, paroxetine, pramipexole, tramadol, venlafaxine, amitriptyline, milnacipran, and γ-hydroxybutyrate are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of fibromyalgia.

Pretest and Objectives

Posttest

Registration Form

Footnotes

This Academic Highlights section of The Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry presents the highlights of the planning teleconference series “Understanding Fibromyalgia and Its Related Disorders,” which was held in October and November 2007. This report was prepared by the CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., and was supported by an educational grant from Eli Lilly and Company.

The planning teleconference was chaired by Don L. Goldenberg, M.D., Department of Medicine and the Department of Rheumatology, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Newton, Mass. The faculty were Laurence A. Bradley, Ph.D., Division of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, and the Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics of Musculoskeletal Disorders, University of Alabama, Birmingham; Lesley M. Arnold, M.D., Director of Women's Health Research Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio; Jennifer M. Glass, Ph.D., Substance Abuse Section, Department of Psychiatry, and the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor; and Daniel J. Clauw, M.D., Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor.

Financial disclosure: Dr. Goldenberg is a consultant for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, Cypress Bioscience, and Forest. Dr. Bradley is a consultant for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Forest; has received grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and the American Fibromyalgia Syndrome Association; has received honoraria from Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Forest, and the Society for Women's Health Research; is a member of the speakers/advisory board for Pfizer; and has received royalties from UpToDate Rheumatology. Dr. Arnold has received grant/research support from Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Cypress Bioscience, Wyeth, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Allergan, and Forest; is a consultant for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Cypress Bioscience, Wyeth, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sepracor, Forest, Allergan, Vivus, and Organon; and is a member of the speakers bureaus for Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Dr. Glass has received grant/research support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and the Department of Defense and has received honoraria from Pierre Fabre. Dr. Clauw is a consultant for and a member of the speakers/advisory boards for Cypress Bioscience, Forest, Wyeth, Pfizer, and Eli Lilly and has received grant/research support from Cypress Bioscience.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the faculty and do not necessarily reflect the views of the CME provider and publisher or the commercial supporter.

References

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, and Yunus MB. et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 33:160–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RC, Felson DT, and Helmick CG. et al. for the National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States, pt 2. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 58:26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM, Hudson JI, and Keck PE. et al. Comorbidity of fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 67:1219–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison RL, Breeding PC. A metabolic basis for fibromyalgia and its related disorders: the possible role of resistance to thyroid hormone. Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:182–189. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(02)00294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir PT, Harlan GA, and Nkoy FL. et al. The incidence of fibromyalgia and its associated comorbidities: a population-based retrospective cohort study based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes. J Clin Rheumatol. 2006 12:124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Arnold LM, and Keck PE. et al. Family study of fibromyalgia and affective spectrum disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2004 56:884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM, Hudson JI, and Hess EV. et al. Family study of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 50:944–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F, Russell IJ, and Vipraio G. et al. Serotonin levels, pain threshold, and fibromyalgia symptoms in the general population. J Rheumatol. 1997 24:555–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H, Buskila D, and Neumann L. et al. Confirmation of an association between fibromyalgia and serotonin transporter promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism, and relationship to anxiety-related personality traits. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 46:845–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offenbaecher M, Bondy B, and de Jonge S. et al. Possible association of fibromyalgia with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Arthritis Rheum. 1999 42:2482–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefgen B, Schulze TG, and Ohlraun S. et al. The power of sample size and homogenous sampling: association between the 5-HTTLPR serotonin transporter polymorphism and major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005 57:247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo A, Boyd P, and Lumsden S. et al. Association between functional polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene and diarrhoea predominant irritable bowl syndrome in women. Gut. 2004 53:1452–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M. Is there a SERT-ain association with IBS? Gut. 2004;53:1396–1399. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.039826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Allaf AW, Dunbar KL, and Hallum NS. et al. A case-control study examining the role of physical trauma in the onset of fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002 41:450–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness EF, Macfarlane GJ, and Nahit E. et al. Mechanical injury and psychosocial factors in the work place predict the onset of widespread body pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 50:1655–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MC, Zautra AJ, Reich JW. Vulnerability to stress among women in chronic pain from fibromyalgia and osteoarthritis. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:215–226. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2303_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCain GA, Tilbe KS. Diurnal hormone variation in fibromyalgia syndrome: a comparison with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1989;19:154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofford LJ, Pillemer SR, and Kalogeras KT. et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis perturbations in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1994 37:1583–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaerøy H, Qiao ZG, and Mørkrid L. et al. Altered sympathetic nervous system response in patients with fibromyalgia (fibrositis syndrome). J Rheumatol. 1998 16:1460–1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bou-Holaigah I, Calkins H, and Flynn JA. et al. Provocation of hypotension and pain during upright tilt table testing in adults with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1997 15:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Lavín M, Hermosillo AG, and Rosas M. et al. Circadian studies of autonomic nervous balance in patients with fibromyalgia: a heart rate variability analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998 41:1966–1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PK, Domitrovich PP, and Ambrose K. et al. Sex effects on heart rate variability in fibromyalgia and gulf war illness. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 51:700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roizenblatt S, Moldofsky H, and Benedito-Silva AA. et al. Alpha sleep characteristics in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 44:222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Lavín M, Hermosillo AG, and Mendoza C. et al. Orthostatic sympathetic derangement in subjects with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1997 24:714–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding SM. Sleep in fibromyalgia patients: subjective and objective findings. Am J Med Sci. 1998;315:367–376. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199806000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli G, Suman AL, and Biasi G. et al. Reactivity to superficial and deep stimuli in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 2002 100:259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledeboer A, Liu T, and Shumilla JA. et al. The glial modulatory drug AV411 attenuates mechanical allodynia in rat models of neuropathic pain. Neuron Glia Biol. 2007 2:279–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LR, Milligan ED, Maier SF. Glial proinflammatory cytokines mediate exaggerated pain states: implications for clinical pain. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;521:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracely RH, Petzke F, and Wold JM. et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 46:1333–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PB, Patterson JC II, and Sunderland JS. et al. Reduced presynaptic dopamine activity in fibromyalgia syndrome demonstrated with positron emission tomography: a pilot study. J Pain. 2007 8:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KP, Nielson WR, and Harth M. et al. Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain with or without fibromyalgia: psychological distress in a representative community adult sample. J Rheumatol. 2002 29:588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane GJ, Thomas E, and Papageorgiou AC. et al. The natural history of chronic pain in the community: a better prognosis than in the clinic? J Rheumatol. 1996 23:1617–1620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, and Arnold LM. et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2005 32:2270–2277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI. A supplemental interview for forms of “affective spectrum disorder.”. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1991;21:205–232. doi: 10.2190/1AF2-3C2R-TYLL-QAX3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayar K, Aksu G, and Ak I. et al. Venlafaxine treatment of fibromyalgia. Ann Pharmacother. 2003 37:1561–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendreau RM, Thorn MD, and Gendreau JF. et al. Efficacy of milnacipran in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2005 32:1975–1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM, Lu Y, and Crofford LJ. et al, for the Duloxetine Fibromyalgia Trial Group. A double-blind, multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients with or without major depressive disorder. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 50:2974–2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM, Rosen A, and Pritchett YL. et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia with or without major depressive disorder. Pain. 2005 119:5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbain D. Evidence-based data on pain relief with antidepressants. Ann Med. 2000;32:305–316. doi: 10.3109/07853890008995932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg D, Mayskiy M, and Mossey C. et al. A randomized, double-blind crossover trial of fluoxetine and amitriptyline in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1996 39:1852–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mula M, Pini S, Gassano GB. The role of anticonvulsant drugs in anxiety disorders: a critical review of the evidence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:263–272. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e318059361a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewes AM, Andreasen A, and Jennum P. et al. Zopiclone in the treatment of sleep abnormalities in fibromyalgia. Scand J Rheumatol. 1991 20:288–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldofsky H, Lue FA, and Mously C. et al. The effect of zolpidem in patients with fibromyalgia: a dose ranging, double blind, placebo controlled, modified crossover study. J Rheumatol. 1996 23:529–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM, Keck PE Jr, Welge JA. Anti-depressant treatment of fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis and review. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:104–113. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.41.2.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofford LJ, Rowbotham MC, and Mease PJ. et al. Pregabalin for the treatment of fibro-myalgia syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 52:1264–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM, Goldenberg DL, and Stanford SB. et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibro-myalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 56:1336–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindmarch I, Dawson J, Stanley N. A double-blind study in healthy volunteers to assess the effects on sleep of pregabalin compared with alprazolam and placebo. Sleep. 2005;28:187–193. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldvary-Schaefer N, De Leon Sanchez I, and Karafa M. et al. Gabapentin increases slow-wave sleep in normal adults. Epilepsia. 2002 43:1493–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicassio PM, Radojevic V, and Weisman MH. et al. A comparison of behavioral and educational interventions for fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1997 24:2000–2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloaguen V, Cottraux J, and Cucherat M. et al. A meta-analysis of the effects of cognitive therapy in depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 1998 49:59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RA, Otto MW, and Pollack MP. et al. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a preliminary meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1997 28:285–305. [Google Scholar]

- Busch AJ, Barber KA, and Overend TJ. et al. Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 4:CD003786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, and Kampert JB. et al. Exercise treatment for depression: efficacy and dose response. Am J Prev Med. 2005 28:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM. Biology and therapy of fibromyalgia: new therapies in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:212. doi: 10.1186/ar1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachrisson O, Regland B, and Jahreskog M. et al. A rating scale for fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome (the FibroFatigue scale). J Psychosom Res. 2002 52:501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RM, Jones J, and Turk DC. et al. An internet survey of 2596 people with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007 9:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-27. Available at http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-247/8/27. Accessed on Nov 2, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz RS, Heard AR, and Mills M. et al. The prevalence and clinical impact of reported cognitive difficulties (fibrofog) in patients with rheumatic disease with and without fibromyalgia. J Clin Rheumatol. 2004 10:53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JM, Park DC, and Minear M. et al. Memory beliefs and function in fibromyalgia patients. J Psychosom Res. 2005 58:263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JM, Park DC. Cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2001;3:123–127. doi: 10.1007/s11926-001-0007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick B, Eccleston C, Crombez G. Attentional functioning in fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and musculoskeletal pain patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:639–644. doi: 10.1002/art.10800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Glass JM, and Minear M. et al. Cognitive function in fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 44:2125–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JM, Park DC, and Minear M. Memory performance with divided attention in fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 50suppl 9. S489. [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt F, Katz RS. Distraction as a key determinant of impaired memory in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JM, Park DC, and Crofford LJ. et al. Fibromyalgia patients show reduced executive/cognitive control in a task-switching test. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 54suppl 9. S610. [Google Scholar]

- Suhr JA. Neuropsychological impairment in fibromyalgia: relation to depression, fatigue, and pain. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00628-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landro NI, Stiles TC, Sletvold H. Memory functioning in patients with primary fibromyalgia and major depression and healthy controls. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks S, Dinges DF. Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:519–528. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer JW, Selke G, and Melson AK. et al. Decreased memory performance in healthy humans induced by stress-level cortisol treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999 56:527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkman MN, Giordani B, and Berent S. et al. Elevated cortisol levels in Cushing's disease are associated with cognitive decrements. Psychosom Med. 2001 63:985–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sephton SE, Studts JL, and Hoover K. et al. Biological and psychological factors associated with memory function in fibromyalgia syndrome. Health Psychol. 2003 22:592–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart RP, Martelli MF, Zasler ND. Chronic pain and neuropsychological functioning. Neuropsychol Rev. 2000;10:131–149. doi: 10.1023/a:1009020914358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass J, Williams D, and Gracely R. et al. Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia relationship of self-reported pain, tender point count, and evoked pressure pain sensitivity to cognitive function in fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2004 5suppl 1. S38. [Google Scholar]

- Maizels M, McCarberg B. Antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs for chronic non-cancer pain. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:483–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadabhoy D, Clauw DJ. Therapy insight: fibromyalgia–a different type of pain needing a different type of treatment. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:364–372. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexeril (cyclobenzaprine) [package insert]. West Point, Pa: Merck. 2001 http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/label/2003/017821s045lbl.pdf. Accessed on Dec 18, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vitton O, Gendreau M, and Gendreau J. et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of milnacipran in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004 19suppl 1. S27–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell I, Kamin M, and Bennett RM. et al. Efficacy of tramadol in treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. J Clin Rheumatol. 2000 6:250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf MB, Baumann M, Berkowitz DV. The effects of sodium oxybate on clinical symptoms and sleep patterns in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1070–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman AJ, Myers RR. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, in patients with fibromyalgia receiving concomitant medications. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2495–2505. doi: 10.1002/art.21191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RM, Kamin M, and Karim R. et al. Tramadol and acetaminophen combination tablets in the treatment of fibromyalgia pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Med. 2003 114:537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RM, Schein J, and Kosinski MR. et al. Impact of fibromyalgia pain on health-related quality of life before and after treatment with tramadol/acetaminophen. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 53:519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM, Hess EV, and Hudson JI. et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, flexible-dose study of fluoxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2002 15:191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patkar AA, Masand PS, and Krulewicz S. et al. A randomized, controlled, trial of controlled release paroxetine in fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2007 120:448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F, Cathey MA, Hawley DJ. A double-blind placebo controlled trial of fluoxetine in fibromyalgia. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994;23:255–259. doi: 10.3109/03009749409103725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantini F, Bellandi F, and Niccoli L. et al. Fluoxetine combined with cyclobenzaprine in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Minerva Med. 1994 85:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderberg UM, Marteinsdottir I, von Knorring L. Citalopram in patients with fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur J Pain. 2000;4:27–35. doi: 10.1053/eujp.1999.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MF, Balousek SL, and Klessig CL. et al. Substance use disorders in a primary care sample receiving daily opioid therapy. J Pain. 2007 8:573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staud R. Treatment of fibromyalgia and its symptoms. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:1629–1642. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.11.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch A, Schachter CL, and Peloso PM. et al. Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome. Chochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002 3:CD003786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haanen HC, Hoenderdos HT, and van Romunde LK. et al. Controlled trial of hypnotherapy in the treatment of refractory fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1991 18:72–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KP, Nielson WR, and Harth M. et al. Does the label “fibromyalgia” alter health status, function, and health service utilization?: a prospective, within-group comparison in a community cohort of adults with chronic widespread pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 47:260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt CS, Mannerkorpi K, and Hedenberg L. et al. A randomized, controlled clinical trial of education and physical training for women with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1994 21:714–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannerkorpi K, Henriksson C. Non-pharmacological treatment of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Rheumatol. 2007;21:513–534. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowans SE, deHueck A, and Voss A. et al. Effect of a randomized, controlled trial of exercise on mood and physical function in individuals with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 45:519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA, Cary MA, and Groner KH. et al. Improving physical function status in patients with fibromyalgia: a brief cognitive behavioral intervention. J Rheumatol. 2002 29:1280–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg DL, Burckhardt C, Crofford L. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA. 2004;292:2388–2395. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan B, White A, Rahman A. Acupuncture in the treatment of fibromyalgia in tertiary care: a case series. Acupunct Med. 2007;25:137–147. doi: 10.1136/aim.25.4.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staud R. Are tender point injections beneficial: the role of tonic nociception in fibromyalgia. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains G, Hains F. A combined ischemic compression and spinal manipulation in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a preliminary estimate of dose and efficacy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Diego M, and Cullen C. et al. Fibromyalgia pain and substance P decrease and sleep improves after massage therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2002 8:72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu AS, Mathew E, and Danda D. et al. Management of patients with fibromyalgia using biofeedback: a randomized control trial. Indian J Med Sci. 2007 61:455–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart HM, Arslanian CL, and Bae S. et al. Effects of T'ai Chi exercise on fibromyalgia symptoms and health-related quality of life. Orthop Nurs. 2003 22:353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva GD, Lorenzi-Filho G, Lage LV. Effects of yoga and the addition of Tui Na in patients with fibromyalgia. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:1107–1114. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Buskila D, and Carrabba M. et al. Treatment strategy in fibromyalgia syndrome: where are we now? [published online ahead of print Oct 30, 2007]. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]