Abstract

Most poxviruses, including variola, the causative agent of smallpox, express a secreted protein of 35 kDa, vCCI, which binds CC-chemokines with high affinity. This viral protein competes with the host cellular CC-chemokine receptors (CCRs), reducing inflammation and interfering with the host immune response. Such proteins or derivatives may have therapeutic uses as anti-inflammatory agents. We have determined the crystal structure to 1.85-Å resolution of vCCI from cowpox virus, the prototype of this poxvirus virulence factor. The molecule is a β-sandwich of topology not previously described. A patch of conserved residues on the exposed face of a β-sheet that is strongly negatively charged might have a role in binding of CC-chemokines, which are positively charged.

During both early and late stages of infection, viruses express soluble and membrane-bound proteins to attenuate the host immune response and increase viral virulence (1). Poxviruses, in particular, appear to encode homologs of a number of vertebrate genes active in the vertebrate immune response and as a consequence interfere with many aspects of host immune responses (2). Many of these virulence factors interfere with host cytokines that normally regulate lymphocyte trafficking and the localization of an immune response.

Chemokines (chemotactic cytokines) are small 8- to 12-kDa proteins with a characteristic dicysteine motif (3). Depending on the presence and spacing of the two N-terminal cysteines, they are classified into subfamilies CXC, CC, C, and CX3C. All of these proteins have a very similar tertiary fold consisting of a short N-terminal flexible segment, a loop region (the N-loop) that follows the CXC or CC motif, three antiparallel β-strands, and a C-terminal α-helix. In general CXC-chemokines attract neutrophils and CC-chemokines attract macrophages and T cell subpopulations, whereas lymphotactin (the only member of the C-chemokines) attracts T and natural killer (NK) cells (3–6). Their cellular receptors belong to the family of seven-transmembrane segment G-protein-coupled receptors (7). Many of these receptors bind several chemokines but are generally specific for members of the same subfamily.

Most poxviruses with appreciable virulence express a secreted ≈35-kDa protein, vCCI (viral CC-chemokine inhibitor) (8–10), that binds with subnanomolar dissociation constant to all the 15 CC-chemokines tested but not to the CXC- or C-chemokines (8). vCCI exhibits no sequence homology with known host chemokine receptors or any other known proteins. It competes with cellular receptors for chemokine binding to retard the activation and chemotaxis of monocytes in the early stages of the host inflammatory response to the viral infection.

Chemokines have also been shown to inhibit HIV-1 infection by competing with gp120 for binding to chemokine receptors on target cells (11). After binding to CD4, the glycoprotein on HIV-1 undergoes a conformational change which increases its affinity for chemokine receptors that act as obligatory coreceptors for HIV-1 infection (reviewed in ref. 12). The mechanism of HIV-1 inhibition appears to be competitive inhibition by chemokine binding to the cellular receptors. vCCI competitively inhibits chemokine binding to the HIV-1 coreceptors, suggesting that although structurally very different, vCCI and cellular receptors may bind overlapping surfaces on chemokines.

We have determined the crystal structure of vCCI from cowpox virus (CPV) and refined it at 1.85-Å resolution. The structure defines surfaces that are conserved in the vCCI family and are candidates for the chemokine-binding site.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Expression and Purification.

The mature cowpox virus vCCI sequence (224 amino acids), N-terminally tagged with the octapeptide FLAG epitope, was subcloned in the Asp-718 and BamHI sites of the yeast expression vector PIXY456 (13). Yeast transformation and protein production from yeast were performed as described (13). The yield of expression was ≈6 mg/liter. The protein was purified to homogeneity from culture supernatants by successive anion- and cation-exchange chromatography, followed by size-exclusion chromatography (Q-Sepharose, Mono S, HR 10/60; Pharmacia).

Labeling with Selenomethionine.

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (DXB-11) were adapted to grow in a DMEM/F12-based serum-free medium supplemented with peptone, lipids, insulin-like growth factor 1, hypoxanthine, and thymidine (14). A cDNA fragment encoding vCCI with an N-terminal FLAG (octapeptide) epitope was subcloned into the CHO cell expression vector 2A5ib (15). Approximately 10 μg of p35–2A5ib expression plasmid was used to transfect DXB-11 cells by using Lipofectamine (GIBCO/BRL). Selection of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR)-positive transfectants and methods to amplify expression have been described (14). Pools of transfectants were amplified in 150 nM methotrexate. vCCI was labeled with selenomethionine (Sigma) as described (16) with the following modifications. Cells were grown in medium supplemented with 150 nM methotrexate, and then the medium was replaced with DMEM/F12 serum-free medium described above lacking peptone and methionine and supplemented with 50 mg⋅ml−1 selenomethionine. The cells were incubated 12 hr, after which the medium was replaced with fresh selenomethionine-containing medium. After 4 days at 34°C, the cell supernatant was harvested. The yield of expression for the selenomethionine-labeled protein in CHO cells was 2 mg/liter. The selenomethionine-substituted vCCI protein was purified identically to the native protein.

Crystallization and Data Collection.

Crystals of native and selenomethionine-substituted proteins were grown at 12°C by vapor diffusion in hanging drops combining 2 μl of protein solution in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (4 mg⋅ml−1) and 2 μl of reservoir solution [20–22% (vol/vol) 8-kDa polyethylene glycol (PEG 8000)/10% (wt/vol) glycerol/25 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0]. Crystals are orthorhombic, space group C2221, with a = 62.4 Å, b = 64.5 Å, c = 245.3 Å, and two molecules per asymmetric unit. A Gd3+ derivative was obtained by soaking native or selenomethionine-substituted crystals in a solution containing 30% PEG 8000, 20% glycerol, 25 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer at pH 8.0, and 1 mM Gd(NO3)3 for 12 hr. For data collection, crystals were mounted in thin rayon loops and then flash-cooled in a stream of nitrogen gas (100 K).

Diffraction data were collected at 100 K with a 30-cm image plate scanner (MAR Research, Hamburg, Germany) mounted on an Elliott GX-13 rotating anode source (Elliot, London) with mirror optics. A 1.85-Å resolution data set was collected at the F1 beam line at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) on a Quantum-4 charge-coupled device detector. Oscillation images were processed with denzo (HKL Research) and data reduction was carried out with scalepack (17). The CCP4 suite (18) of programs was used for further data processing and analysis.

Structure Determination and Refinement.

The crystal structure was determined by multiple isomorphous replacement anomalous scattering (MIRAS) and iterative twofold noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging from crystals of native and selenomethionine-substituted proteins (Table 1). Initial heavy atom sites (one per molecule) were located for derivative I (Table 1) in isomorphous and anomalous difference Patterson maps. At this point 10 selenomethionine positions (5 for each molecule) in derivative II and III were located by difference Fourier techniques and together with the Gd3+ positions were refined in ml-phare (18). A 3.4-Å twofold real space averaged electron density map was then calculated with dm (18), using a monomer mask based on the local correlation of the electron density. Inspection of the map showed clearly protein secondary structure elements and the molecular boundaries. After map skeletonization with bones (19) a new monomer mask from the edited skeleton was computed and new cycles of twofold NCS averaging and phase extension to 2.8 Å were performed. The resulting averaged electron density map was of excellent quality and allowed the complete protein chain to be traced.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for cowpox vCCI

| I | II | III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Diffraction data | Native 1 | Native 2 | Gd3+ | SeMet | SeMet + Gd3+ |

| Space group | C2221 | C2221 | C2221 | C2221 | C2221 |

| Resolution, Å | 2.82 | 1.85 | 3.60 | 3.40 | 3.40 |

| Total observations | 54,518 | 176,998 | 23,305 | 31,592 | 53,803 |

| Unique reflections | 11,986 | 46,769 | 5,037 | 7,094 | 7,098 |

| Completeness, % | 97.7 (98.5) | 87.7 (66.6) | 80.9 (85.9) | 99.1 (95.4) | 99.0 (98.3) |

| Rsym, % | 9.2 (23.1) | 6.5 (15.0) | 6.2 (7.0) | 74 (11.1) | 7.6 (11.4) |

| Rderiv, % | 14.9 (14.8) | 11.7 (18.0) | 17.4 (20.2) | ||

| Phasing power | 1.48 (0.98) | 1.23 (0.78) | 1.57 (1.08) | ||

| Figure of merit | 0.62 (a) | 0.74 (c) | |||

| Refinement statistics | |||||

| Resolution range, Å | 20–1.85 | ||||

| No. reflections in working set | 45,823 | ||||

| Rcryst | 0.212 | ||||

| Rfree | 0.244 | ||||

| rms deviation from ideal geometry | |||||

| Bond length, Å | 0.007 | ||||

| Bond angles, ° | 1.43 | ||||

| Average B factors | |||||

| Protein atoms, Å2 | 26.7 | ||||

| Solvent molecules, Å2 | 39.2 | ||||

| Anisotropic B factor, Å2 | B11 = 2.291, B22 = −5.156, B33 = 2.86 | ||||

| Bulk solvent correction | B = −3.603 Å2 k = 0.38 e/Å3 | ||||

Rsym = ΣhΣi|Ii(h) − 〈I(h〉)|ΣhΣiIi(h), where Ii(h) is the ith measurement and 〈I(h)〉 is the weighted mean of all measurements of I(h). Rderiv = Σh| |Fderiv(h)| − |Fnative1(h)| |/Σh|Fnative1(h)|. Phasing power = 〈|FH|〉/E, where 〈|FH|〉 is the structure factor amplitude for the heavy atom and E is the estimated lack-of-closure error. Rcryst and Rfree = Σh| |F(h)obs| − |F(h)calc| |/Σh|F(h)obs| for reflections in the working and test sets, respectively. Numbers in parentheses are for final shell.

Five percent of the total reflections were used to define the free R factor at the beginning of refinement. The structure was initially refined at 2.8 Å with cns (20) by several cycles of torsion angle dynamics simulated annealing followed by positional refinement using a maximum likelihood target (ML). Strict NCS and an overall B factor of 20 Å2 were applied at this stage of the refinement. SigmaA-weighted (2 mFo − DFc) and (mFo − DFc) electron density maps were used for model correction and rebuilding. When the Rfree decreased below 0.30 the refinement was continued using the 1.85-Å data set. Toward the end the NCS was released, individual B factors were refined, and water molecules, located by using warp (18), were included in the model. Throughout the refinement, a bulk solvent correction and anisotropic B-factor tensor were also applied. The final model contains two vCCI molecules (residues 1–224) and 470 water molecules. No electron density was observed for the N-terminal FLAG octapeptides, which were disordered. The Rwork is 21.2% and Rfree is 24.4% for all reflections above 2σ between 20.0- and 1.85-Å resolution. The model has good stereochemistry, with an average bond length and bond angle deviation of 0.007 Å and 1.43°, respectively. Ninety-one % of the residues are in the most favored or allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot. Only Ser-189 in molecule A′ has φ, ψ angles (φ = −4.7°, ψ = −120.8°) in the nonallowed region. This residue is part of a loop that has different conformation in the two NCS-related molecules.

Results

Overall Structure of vCCI.

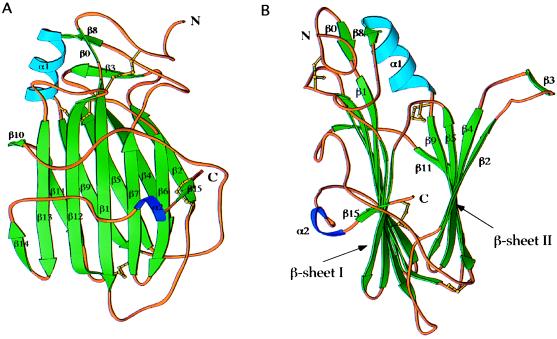

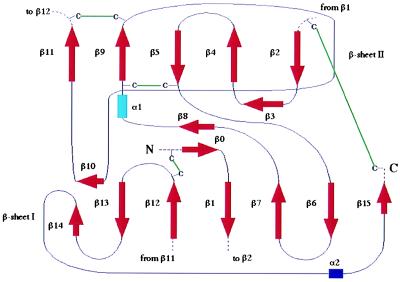

vCCI is a compact globular protein of approximately 55 Å × 35 Å × 30 Å (Fig. 1). The molecule is composed primarily of two β-sheets, parallel to each other, two short α-helices, and a few large loops connecting these secondary structure elements. The first β-sheet (sheet I) (Figs. 1 and 2), composed of seven antiparallel β-strands, (β15, β6, β7, β1, β12, β13, and β14), is surrounded by two long stretches of extended chain, one at the extreme C terminus and another between strands β9 and β10 (both loops in front in Fig. 1A). The second β-sheet (sheet II) is formed by five β-strands (β2, β4, β5, and β9 are antiparallel and β9 is parallel to β11) and has one side completely exposed to the solvent (right side in Fig. 1B). All the side chains, except two valines and one isoleucine, on this exposed surface are from charged or polar residues. Two additional β-strands (β0, β8) and a three-turn α-helix (α1) are present in the upper part of the molecule (Fig. 1). A single-turn α-helix (α2), in the middle of a loop connecting the last two C-terminal β-strands (β14 and β15), packs against β-sheet I. The core of the β-sandwich is mainly composed of nonpolar residues. Only one charged residue, Glu-87, is buried in the interior. Its carboxylate group makes hydrogen bonds with the backbone amide of Cys-38 and with an internally trapped solvent molecule. Glu-87 is strictly conserved in all the members of the vCCI family (Fig. 3). Eight cysteines are involved in four disulfide bridges [Cys-8–Cys-185, Cys-38–Cys-223, Cys-79–Cys-124, and Cys-132–Cys-171) (Figs. 1–3), which probably contribute to the high thermal stability of the molecule (unfolding temperature 86°C (R. Remmele and C.A.S., unpublished results)]. A very serine-rich sequence (SFSSSSC, residues 1–7) is part of a random coil at the N terminus of the molecule.

Figure 1.

Structure of cowpox vCCI: Ribbon diagrams. A and B are related by 90° rotation. Green arrows represent β-strands, blue ribbons, α helices. This figure was created with ribbons (30).

Figure 2.

Secondary structure elements of the cowpox virus vCCI: Topology diagram.

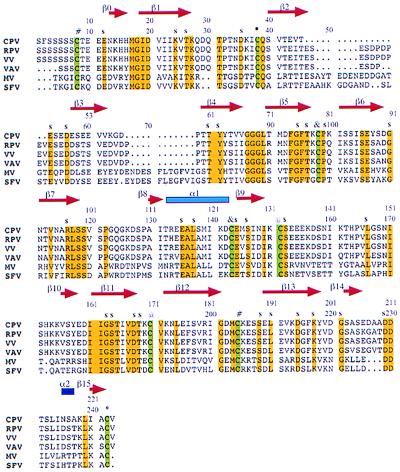

Figure 3.

Sequence alignment of six members of the poxvirus vCCI family (CPV, cowpox (31); RPV, rabbitpox virus (32); VV, vaccinia virus (33); VAV, variola virus (34); MV, myxomavirus (35); SFV, Shope fibromavirus). Strictly conserved residues (yellow) and the eight cysteines (green) are highlighted. The cysteines involved in disulfide bridges (*, #, @, &) and the exposed conserved residues (s) are also indicated. This figure was generated with Canvas 5.0.3 (Deneba Systems, Miami).

To our knowledge, the β-sandwich topology of vCCI has not been observed in protein structures before now. A search through known protein structures (21) indicates that the fold is reminiscent of the collagen-binding domain from a Staphylococcus aureus adhesin; however, the number of strands forming the β-sheets and their order are different in the two molecules.

Comparison Between the Two Molecules in the Asymmetric Unit.

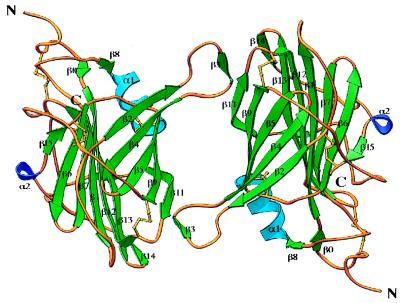

vCCI forms dimers in the crystal with the two molecules related by a proper twofold rotational NCS axis (Fig. 4). Dimerization is mediated by six residues (51–56), part of a large loop between β2 and β4, which adopts a β-strand conformation (β3) (Fig. 4). In the dimer, the β3 strand of one monomer forms hydrogen bonds with the β11 strand of the other monomer, effectively adding one more strand to β-sheet II. The two molecules are almost identical except at the loop connecting β12 with β13 (residues 185–190), which adopts a different conformation in the two molecules. If those residues are excluded, the root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) between the remaining 218 α-carbon atoms is 0.144 Å. However, gel filtration experiments of vCCI alone and in complex with the CC-chemokine MCP-1 showed no evidence of vCCI dimerization in solution (C.A.S., unpublished results).

Figure 4.

Ribbon diagram of the dimer formed by the NCS-related molecules in the crystal. This figure was created with ribbons (30).

Comparison with Other Proteins from the vCCI Family.

The sequences of mature vCCI from five different poxviruses are aligned in Fig. 3. The proteins have between approximately 40% and 95% sequence identity, and all have the same number and pattern of conserved cysteines. The largest difference is observed between the orthopoxvirus and leporopoxvirus vCCI proteins, which have 38% sequence identity. Two insertions totaling 18–28 residues are present between the β2 and β4 strands in the leporipoxviruses that are absent from the orthopoxviruses (Fig. 3). These insertions could be accommodated in the protruding loop of the cowpox vCCI structure where they would flank β3 in Fig. 1B. Quantitative chemokine binding experiments using recombinant vCCI proteins from five members of the two virus subfamilies (Orthopoxviridae, Leperipoxviridae) showed no significant difference in chemokine binding (8). Therefore, residues in those insertions are probably not important for chemokine binding.

Chemokine Binding.

It has previously been shown that vCCI binds virtually all CC-chemokines with subnanomolar dissociation constants (and IL-8, a CXC-chemokine, with micromolar affinity) and completely inhibits their biological activity (8). The mechanism of inhibition appears to be simple competitive inhibition of chemokine binding to cellular receptors, suggesting that although structurally very different, vCCI and cellular receptors may bind overlapping surfaces on chemokines.

Several studies have characterized the interaction between chemokines and cellular receptors (reviewed in ref. 22). Chemokines bind to negatively charged sequences at the N termini of the cellular chemokine receptors and also to charged residues on some of the external loops (23–26). Chemokine residues 1–8, preceding the first cysteine and the N-loop, 10 residues between the CC or CXC motif and the first chemokine β-strand, are important for receptor binding and activity (27).

An NMR study of the binding between the CXC-chemokine IL-8 and a modified peptide (MWDFDD(hexanoic acid)6PPADEDYSP) derived from the N terminus of the membrane-bound IL-8 CXCR receptor showed that the receptor peptide binds in an extended conformation in a hydrophobic cleft in IL-8 formed by the N loop (residues 11–21) and a β-hairpin (residues 40–49) (28). The majority of the contacts of the peptide are made by the tandem prolines and one tyrosine (underlined in the sequence above). These residues fill two hydrophobic pockets in the chemokine cleft and anchor the peptide to the chemokine. It has recently been shown that tyrosine residues at the N termini of cellular chemokine receptors are sulfated in vivo (26, 29). The hydroxyl group of the tyrosine in the bound CXCR peptide points outside the chemokine cleft and if it had been sulfated may have interacted with the positively charged residues (Lys-11 or -15 in figure 5b of ref. 28) in its proximity. [None of the five tyrosines in vCCI appear sulfated in the electron density maps and only one, Tyr-88, has a preceding acidic residue as found in the consensus sulfation motif, but Tyr-88 is not conserved in other vCCI family members (Fig. 3).] Three negatively charged residues (DED) between the tandem prolines and the tyrosine and three aspartic acid residues at the N terminus of the CXCR peptide (DFDD) are also close to basic residues of IL-8 (28).

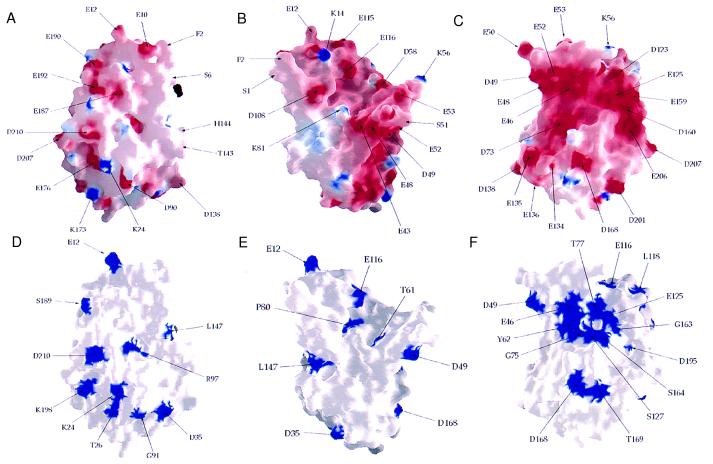

In the cowpox vCCI there are negatively charged surfaces (Fig. 5 A–C), especially on the exposed surface of β-sheet II (Fig. 5C). Most of the surface acidic residues are, however, not conserved (compare with Fig. 5 D–F). The prominent cleft at the top of the structure in Fig. 5 B and E, which looks like a ligand-binding groove, contains only three conserved residues and would have large insertions on its right side (Fig. 5E) in other vCCI family members, so it seems unlikely to be the chemokine binding site. The edge of β-sheet II (β11 in Fig. 4), where the crystallographic dimer forms by β-sheet extension, is the location of the longest sequence of conserved residues (161–186 in Fig. 3), but most are not on the surface (Fig. 5F). It forms a surface located approximately between the conserved acidic positions D168 and E206 on the surface in Fig. 5C and is one candidate for interacting with the N-loop of a chemokine. A patch of conserved residues on the exposed face of β-sheet II (Fig. 5F), containing both conserved acidic residues (Glu-46, Asp-49, Glu-125) and a conserved surface accessible tyrosine (Tyr-62), is a large surface of conserved residues with no apparent structural role which might, therefore, have been conserved as a ligand-binding site. These sites are candidates for mutational analysis to further define the mode of binding and the mechanism of chemokine inhibition. It will be interesting to see whether vCCI and cellular chemokine receptors such as the HIV-1 coreceptors share some of the same features of their interaction with chemokines.

Figure 5.

Surface representation of vCCI. (A–C) Electrostatic potential of vCCI. A and B are in the same orientations as in Fig. 1 A and B, respectively, and C is the exposed face of β-sheet II (the molecule is rotated 180° compared with Fig. 5A). (D–F) Exposed conserved residues viewed as in A–C. This figure was generated with grasp (36).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the Harrison/Wiley laboratories for useful discussions. A.C. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Association Française pour la Recherche Terapeutique. D.C.W. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations

- CPV

cowpox virus

- NCS

noncrystallographic symmetry

Footnotes

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID code 1cq3).

References

- 1.Ploegh H L. Science. 1998;280:248–253. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McFadden G, editor. Viroceptors, Virokines and Related Immune Modulators Encoded by DNA Viruses. Austin, TX: Landes; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggiolini M. Nature (London) 1998;392:565–568. doi: 10.1038/33340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward S G, Bacon K, Westwick J. Immunity. 1998;9:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80583-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Springer T A. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proost P, Wuyts A, van Damme J. Int J Clin Lab Res. 1996;26:211–223. doi: 10.1007/BF02602952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bockaert J, Pin J P. EMBO J. 1999;18:1723–1729. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith C A, Smith T D, Smolak P J, Friend D, Hagen H, Gerhart M, Park L, Pickup D J, Torrance D, Mohler K, et al. Virology. 1997;236:316–327. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lalani A S, McFadden G. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:570–576. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.5.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alcamí A, Symons J A, Collins P D, Williams T J, Smith G L. J Immunol. 1998;160:624–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cocchi F, DeVico A L, Garzino-Demo A, Arya S K, Gallo R C, Lusso P. Science. 1995;270:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger E, Murphy P, Farber J. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graddis T J, Brasel K, Friend D, Srinivasan S, Wee S, Lyman S D, March C Y, McGrew J T. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17626–17633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman R J. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:537–566. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85044-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris A E, Lee C, Hodges K, Aldrich T L, Krantdz C, Smidt P C, Thomas J N. In: Animal Cell Technology: From Vaccines to Genetic Medicine. Carrondo M J T, Griffiths B, Moreira J L P, editors. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1997. pp. 529–534. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lustbader J W, Wu H, Birken S, Pollak S, Gawinowicz Kolks M A, Pound A M, Austen D, Hendrickson W A, Canfield R E. Endocrinology. 1995;136:640–650. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.2.7835298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otwinowski Z. In: Proceedings of the CCP4 Study Weekend: Data Collection and Processing. Sawyer L, Isaac N, Bailey S, editors. Warrington, U.K.: SERC Danesbury Laboratory; 1993. pp. 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collaborative Computational Project 4. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones T A, Zou J-Y, Cowan S W, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brünger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, Delano W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:901–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holm L, Sander C. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:478–480. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rollins B J. Blood. 1997;90:909–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gayle R B, 3rd, Sleath P R, Srinivason S, Birks C W, Weerawarna K S, Cerretti D P, Kozlosky C J, Nelson N, Vanden Bos T, Beckmann M P. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:7283–7289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leong S R, Kabakoff R C, Hébert C A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19343–19348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monteclaro F S, Charo I F. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23186–23190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farzan M, Choe H, Vaca L, Martin K, Sun Y, Desjardins E, Ruffing N, Wu L, Wyatt R, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. J Virol. 1998;72:1160–1164. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1160-1164.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark-Lewis I, Kim K S, Rajarathnam K, Gong J H, Dewald B, Moser B, Baggiolini M, Sykes B D. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:703–711. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skelton N J, Quan C, Reilly D, Lowman H. Structure. 1999;7:157–168. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farzan M, Mirzabekov T, Kolchinsky P, Wyatt R, Cayabyab M, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J, Hyeryun C. Cell. 1999;96:667–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80577-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carson M. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:958–961. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu F Q, Smith C A, Pickup D J. Virology. 1994;204:343–356. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez-Pomares L, Thompson J P, Moyer R W. Virology. 1995;206:591–600. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel A H, Gaffney D F, Subak-Sharpe J H, Stow N D. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:2013–2021. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-9-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massung R F, Esposito J J, Liu L I, Qi J, Utterback T R, Knight J C, Aubin L, Yuran T E, Parsons J M, Loparev V N, et al. Nature (London) 1993. 748–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graham K A, Lalani A S, Macen J L, Ness T L, Barry M, Liu L Y, Lucas A, Clark-Lewis I, Moyer R W, McFadden G. Virology. 1997;229:12–24. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicholls A, Sharp K A, Honig B. Proteins. 1991;11:281–296. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]