Abstract

The in vitro bactericidal activities of vancomycin against Staphylococcus aureus hemB mutants displaying the small-colony-variant phenotype and their parental strains were evaluated. Vancomycin killing activities against hemB mutants were markedly attenuated, demonstrating approximately 50% less effect, a result which was well described by a Hill-type pharmacodynamic model.

Staphylococcus aureus has various strategies for resisting therapy that extend beyond classic mechanisms. One of these strategies is the formation of small-colony variants (SCVs), a naturally occurring, slow-growing subpopulation with distinctive phenotypical characteristics and pathogenic traits (12, 13). These fastidious variants characterized by decreased pigment formation, reduced hemolytic activity, and decreased coagulase activity have been associated with chronic, relapsing, and persistent infections (8, 17, 18). The pathogenicity of S. aureus SCVs may lie in their ability to persist intracellularly in nonprofessional phagocytes, thus evading surrounding host defenses and antimicrobial agents (4, 11, 23, 26).

In addition to the difficultly of identification in clinical microbiology laboratories, SCVs of S. aureus present a potential problem for eradication and microbiologic cure by antimicrobials. Infections caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) SCVs have displayed poor microbiologic responses to certain antimicrobials and are exceptionally difficult to treat (13, 17). Compared to isogenic strains which display the normal phenotype, SCVs have displayed decreased susceptibility to gentamicin, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, linezolid, and triclosan (1, 2, 5, 11, 25). There have been no investigations evaluating the pharmacodynamic activity of vancomycin against S. aureus SCVs. Therefore, we evaluated the in vitro activities of vancomycin against stable, genetically defined S. aureus mutants and a clinical S. aureus hemin-auxotrophic strain displaying the SCV phenotype and compared the pharmacodynamics to those for the parental isolates displaying the normal phenotype.

(A portion of these results was presented at the 46th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, CA, 27 to 30 September 2006.)

Bacterial isolates utilized in this study included S. aureus strains COL (methicillin resistant) and Newman (methicillin susceptible) and the respective mutants with the SCV phenotype Ia48 (COL hemB::ermB) and III33 (Newman hemB::ermB). The construction of both Ia48 and III33 by allelic replacement in S. aureus strains COL and Newman has been described previously (7, 22).

Additionally, clinically derived S. aureus strains obtained from a patient with a recurrent and persistent infection included A20780 I, displaying the normal phenotype, and the respective hemin-auxotrophic strain displaying the SCV phenotype, A20780 II. A20780 II was recognized as an SCV, clonally identical to the respective normal-phenotype strain, and was genotyped as described previously (23, 24).

Fresh working solutions of vancomycin (analytical-grade powder; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) were made prior to each experimental run. MICs were determined in quadruplicate using CLSI broth microdilution methods.

Brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) supplemented with calcium (25 mg/liter) and magnesium (12.5 mg/liter) was used for all broth microdilution susceptibility testing and time-kill experiments. Briefly, for time-kill experiments, fresh bacterial colonies from an overnight growth were added to normal saline and the turbidity was adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard to provide a standard suspension. This suspension was diluted with BHI and a standard antibiotic stock solution to achieve a starting inoculum of approximately 107 CFU/ml. Each 10-ml culture was incubated in a water bath at 35°C with constant shaking, and 0.1-ml samples were withdrawn for the determination of bacterial counts at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 24 h. Colony counts were determined by plating 50 μl of each diluted sample onto BHI agar (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with an automated spiral dispenser (WASP; Don Whitley Scientific Limited, West Yorkshire, England) and incubating the plates for 24 h at 35°C to confirm colony counts. Ia48 and III33 were incubated for 48 h. Growth control wells for each organism were prepared without antibiotic and run in parallel with the antibiotic test wells. All time-kill experiments were completed in duplicate to quadruplicate.

To accommodate all available data generated for each regimen tested and avoid conclusions based on CFU counts at a single time point, an integrated pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic area measure (the log ratio area) was applied to all CFU data. For each regimen tested, the area under the CFU-versus-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUCFU0-24) was calculated via the trapezoidal rule for both the growth control (AUCFUgrowth control) and the drug-containing regimens (AUCFUdrug). The AUCFU0-24 was normalized by using the AUCFU0-24 for the growth control, and the logarithm of this ratio was used to quantify the drug effect as shown in equation 1. Additionally, the traditional measure (the log ratio change) for comparing the changes in numbers of CFU per milliliter from 0 (CFU0h) to 24 (CFU24h) hours was calculated as shown in equation 2.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Using nonlinear regression, a four-parameter concentration-effect Hill-type model was fit to the effect parameter with a software program (version 11) from Systat (Richmond, VA) with the following equation:

|

(3) |

The dependent variable (E) is either the log ratio area or the log ratio change, E0 is the effect measured at a drug concentration of zero, Emax is the maximal effect, C is concentration of the drug, C/MIC is the concentration-to-MIC ratio, EC50 is the C/MIC ratio for which there is 50% maximal effect, and H is the Hill or sigmoidicity constant.

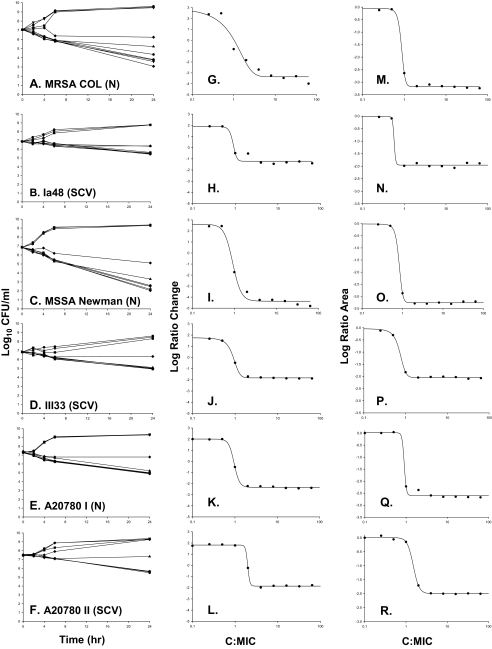

Vancomycin displayed a MIC for S. aureus strains COL, Newman, and A20780 I of 1.0 mg/liter and a MIC for hemB mutants Ia48, III33, and A20780 II of 2.0 mg/liter. The killing activities and pharmacodynamics of vancomycin against all isolates are depicted in Fig. 1. With increasing vancomycin concentrations, a concentration-dependent trend toward a greater level of killing of strains COL, Newman, and A20780 I was observed. Vancomycin achieved bactericidal activity against COL and Newman at all concentrations greater than four times the MIC. Killing activity at concentrations above this threshold was sustained until terminal end points at 24 h, with maximal reductions from the baseline of 3.99 and 4.81 log10 CFU/ml at 64 times the MIC for COL and Newman, respectively. Against the clinical isolate A20780 I, vancomycin approached the bactericidal threshold, as the maximal bacterial reduction was 2.39 log10 CFU/ml at 64 times the MIC.

FIG. 1.

Results from vancomycin time-kill experiments evaluating bactericidal activity toward S. aureus strains displaying the normal (N) and SCV phenotypes. The key to symbols for each regimen is as follows: control (•) and 0.25 (▾), 0.5 (▪), 1 (♦), 2 (▴), 4 ( ), 8 (•), 16 (▾), 32 (▪), and 64 (♦) times the MIC. MSSA, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus.

In contrast, against both hemB mutants displaying the SCV phenotype, vancomycin activity was markedly attenuated compared to that against the isogenic parental strains with the normal phenotype. Against Ia48 and III33, vancomycin did not achieve bactericidal activity over 24 h, as maximal bacterial reductions from the baseline were 1.40 and 1.88 log10 CFU/ml at 24 h. This trend was also observed against the A20780 II clinical isolate displaying the SCV phenotype, as the maximal bacterial reduction from the baseline was 1.78 CFU/ml at 24 h. Killing activity was less dependent on the concentration for all strains displaying the SCV phenotype, Ia48, III33, and A20780 II, than for strains displaying the normal phenotype, as the activities of vancomycin at 4 to 64 times the MIC for the SCV strains gave similar reductions in bacterial counts at 24 h.

Model-fitted parameter estimates for vancomycin against all strains are displayed in Table 1. An analysis of the pharmacodynamics revealed excellent model fits of the data to the Hill model. Among the two pharmacodynamic methods, the log ratio area approach, which accounted for all of the available data over 24 h, revealed better fits to the model, as R2 was greater than 0.99 for all isolates, and also resulted in lower standard errors for H and Emax among most isolates. The bactericidal activity of vancomycin against both those strains displaying the SCV phenotype and those strains displaying the normal phenotype occurred in a concentration-dependent manner. The results from pharmacodynamic comparisons of the strains which displayed the normal phenotype versus the SCVs differed. In particular, the maximal effect of vancomycin was consistently greater for strains which displayed the normal phenotype than for strains which displayed the SCV phenotype.

TABLE 1.

Model-fitted parameter estimatesa for vancomycin versus S. aureus strains displaying the normal and SCV phenotypes

| Parameter | Value for S. aureus strain: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL | Ia48 | Newman | III33 | A20780 I | A20780 II | |

| Log ratio area parameters | ||||||

| E0 | −0.060 (70.0) | 0.018 | −0.016 (>100) | −0.057 (57.8) | 0.014 (>100) | 0.00 (>100) |

| Emax | 3.12 (1.57) | 1.94 | 3.25 (1.05) | 1.99 (1.91) | 2.61 (3.36) | 2.00 (1.40) |

| H | 8.97 (39.8) | 15.0b | 8.29 (12.29) | 5.82 (8.52) | 17.2 (>100) | 6.08 (7.91) |

| EC50 | 0.840 (7.14) | 0.618 | 0.787 (3.12) | 0.699 (3.14) | 0.902 (>100) | 1.50 (>100) |

| R2 | 0.999 | 0.995 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Log ratio change parameters | ||||||

| E0 | 2.77 (15.87) | 1.93 (11.5) | 2.60 (10.5) | 1.75 (1.95) | 2.00 (2.62) | 1.81 (2.35) |

| Emax | 6.21 (8.83) | 3.14 (8.23) | 6.97 (4.73) | 3.59 (1.14) | 4.34 (1.49) | 3.67 (1.60) |

| H | 2.11 (28.91) | 6.16 (85.9) | 4.33 (30.45) | 4.29 (7.05) | 6.89 (34.4) | 17.56 (>100) |

| EC50 | 1.07 (16.1) | 0.839 (16.9) | 0.991 (5.65) | 0.895 (1.56) | 0.955 (2.02) | 1.97 (6.59) |

| R2 | 0.974 | 0.971 | 0.991 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.995 |

Data are reported as maximum-likelihood parameter estimates (percent standard errors are shown in parentheses). E0, effect at concentration-to-MIC ratio of 0; Emax, maximal effect (values expressed as log10 numbers of CFU per milliliter); H, Hill's constant; EC50, concentration-to-MIC ratio for which there is 50% maximal effect.

Hill's constant was fixed at 15.0, and the percent standard error is not shown.

Vancomycin has been the drug of choice for MRSA infections over the last three decades. However, this role is increasingly challenged by concerns over treatment efficacy. Slow clinical responses, vancomycin's slow bactericidal or bacteriostatic killing activity, and strains which display heterogeneous resistance to vancomycin severely limit its use for persistent infections (6, 9, 15). In the present study, we hypothesized that hemB mutants mimicking the SCV phenotype displayed different killing profiles from their isogenic parent strains. Vancomycin displayed reduced killing activities against the mutants, approaching near half the maximal effect, and altered pharmacodynamics compared to those for the parent strains. The findings were consistent when vancomycin was tested against an S. aureus SCV clinical strain for comparison to the clonally identical strain displaying the normal phenotype. Of note, the clinical SCV strain displayed some degree of reversion to large colonies on solid medium after 24 h in the absence of vancomycin and at vancomycin concentrations below and above the MIC; however, this reversion did not appear to significantly impact vancomycin pharmacodynamics, as similar trends were observed among stable hemB mutants.

The reduced activity of vancomycin against SCVs may be due in part to the expression patterns of global regulators σB and the accessory gene regulator (agr) in SCVs of S. aureus. SCVs of S. aureus isolated from cystic fibrosis patients and hemB mutants have been shown previously to be influenced by σB, a stress-induced transcription factor. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated previously that σB reduces the levels of RNA III, the effector molecule of the agr system, in a growth phase-dependent manner (3, 20). Additionally, other investigations have shown that SCVs consistently display low membrane potentials, reduced intracellular ATP concentrations, and reduced RNA III production, resulting in reduced cell wall biosynthesis (10, 16, 19). Furthermore, we tested both hemB SCV mutants for delta-hemolysin expression, a marker for the agr function, and both SCV isolates were delta-hemolysin negative (14, 21). Taken together with our recent findings that a down-regulated agr locus is associated with the development of vancomycin intermediate resistance at therapeutically relevant concentrations, this outcome may provide further explanation of our results which demonstrate attenuated vancomycin activity against hemB mutants (14, 21). Additionally, the lack of bactericidal activity over a wide range of concentrations and the altered pharmacodynamics among hemB mutants also highlight the lack of utility of the MIC alone to predict vancomycin efficacy. Coupled with the suboptimal penetration of vancomycin into some sites of infection, such as epithelial lining fluid in cases of MRSA pneumonia, and the ability of SCVs to persist intracellularly, these findings highlight the difficulty in eradicating S. aureus SCVs in serious, deep-seated infections by glycopeptide monotherapy. These findings also suggest that administering significantly higher doses of vancomycin to combat S. aureus SCV infections may not be beneficial, especially in the light of increased concerns for nephrotoxicity. With recent reports that suggest that SCVs may represent a natural component of the life cycle of staphylococci (13), our findings are of particular interest and may have implications for the optimal treatment of S. aureus infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anson Ho, Christina Hall, Michael Ma, and Dung Ngo for excellent technical assistance.

This study was funded by the University at Buffalo, State University of New York Interdisciplinary Research Fund and the Gustavus and Louise Pfeiffer Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 February 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baumert, N., C. von Eiff, F. Schaaff, G. Peters, R. A. Proctor, and H. G. Sahl. 2002. Physiology and antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants. Microb. Drug Resist. 8:253-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayston, R., W. Ashraf, and T. Smith. 2007. Triclosan resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus expressed as small colony variants: a novel mode of evasion of susceptibility to antiseptics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:176-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff, M., J. M. Entenza, and P. Giachino. 2001. Influence of a functional sigB operon on the global regulators sar and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:5171-5179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouillette, E., A. Martinez, B. J. Boyll, N. E. Allen, and F. Malouin. 2004. Persistence of a Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variant under antibiotic pressure in vivo. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 41:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuard, C., P. E. Vaudaux, R. A. Proctor, and D. P. Lew. 1997. Decreased susceptibility to antibiotic killing of a stable small colony variant of Staphylococcus aureus in fluid phase and on fibronectin-coated surfaces. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39:603-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiramatsu, K. 2001. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a new model of antibiotic resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 1:147-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jonsson, I. M., C. von Eiff, R. A. Proctor, G. Peters, C. Ryden, and A. Tarkowski. 2003. Virulence of a hemB mutant displaying the phenotype of a Staphylococcus aureus small colony variant in a murine model of septic arthritis. Microb. Pathog. 34:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahl, B., M. Herrmann, A. S. Everding, H. G. Koch, K. Becker, E. Harms, R. A. Proctor, and G. Peters. 1998. Persistent infection with small colony variant strains of Staphylococcus aureus in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1023-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine, D. P., B. S. Fromm, and B. R. Reddy. 1991. Slow response to vancomycin or vancomycin plus rifampin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Ann. Intern. Med. 115:674-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moisan, H., E. Brouillette, C. L. Jacob, P. Langlois-Begin, S. Michaud, and F. Malouin. 2006. Transcription of virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants isolated from cystic fibrosis patients is influenced by SigB. J. Bacteriol. 188:64-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proctor, R. A., B. Kahl, C. von Eiff, P. E. Vaudaux, D. P. Lew, and G. Peters. 1998. Staphylococcal small colony variants have novel mechanisms for antibiotic resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27(Suppl. 1):S68-S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proctor, R. A., and G. Peters. 1998. Small colony variants in staphylococcal infections: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:419-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proctor, R. A., C. von Eiff, B. C. Kahl, K. Becker, P. McNamara, M. Herrmann, and G. Peters. 2006. Small colony variants: a pathogenic form of bacteria that facilitates persistent and recurrent infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakoulas, G., G. M. Eliopoulos, R. C. Moellering, Jr., R. P. Novick, L. Venkataraman, C. Wennersten, P. C. DeGirolami, M. J. Schwaber, and H. S. Gold. 2003. Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator (agr) group II: is there a relationship to the development of intermediate-level glycopeptide resistance? J. Infect. Dis. 187:929-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakoulas, G., P. A. Moise-Broder, J. Schentag, A. Forrest, R. C. Moellering, Jr., and G. M. Eliopoulos. 2004. Relationship of MIC and bactericidal activity to efficacy of vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2398-2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seggewiss, J., K. Becker, O. Kotte, M. Eisenacher, M. R. Yazdi, A. Fischer, P. McNamara, N. Al Laham, R. Proctor, G. Peters, M. Heinemann, and C. von Eiff. 2006. Reporter metabolite analysis of transcriptional profiles of a Staphylococcus aureus strain with normal phenotype and its isogenic hemB mutant displaying the small-colony-variant phenotype. J. Bacteriol. 188:7765-7777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seifert, H., C. von Eiff, and G. Fatkenheuer. 1999. Fatal case due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants in an AIDS patient. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:450-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seifert, H., H. Wisplinghoff, P. Schnabel, and C. von Eiff. 2003. Small colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus and pacemaker-related infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:1316-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senn, M. M., M. Bischoff, C. von Eiff, and B. Berger-Bachi. 2005. σB activity in a Staphylococcus aureus hemB mutant. J. Bacteriol. 187:7397-7406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senn, M. M., P. Giachino, D. Homerova, A. Steinhuber, J. Strassner, J. Kormanec, U. Fluckiger, B. Berger-Bachi, and M. Bischoff. 2005. Molecular analysis and organization of the σB operon in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 187:8006-8019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuji, B. T., M. J. Rybak, K. L. Lau, and G. Sakoulas. 2007. Evaluation of accessory gene regulator (agr) group and function in the proclivity towards vancomycin intermediate resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1089-1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaudaux, P., P. Francois, C. Bisognano, W. L. Kelley, D. P. Lew, J. Schrenzel, R. A. Proctor, P. J. McNamara, G. Peters, and C. Von Eiff. 2002. Increased expression of clumping factor and fibronectin-binding proteins by hemB mutants of Staphylococcus aureus expressing small colony variant phenotypes. Infect. Immun. 70:5428-5437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Eiff, C., K. Becker, D. Metze, G. Lubritz, J. Hockmann, T. Schwarz, and G. Peters. 2001. Intracellular persistence of Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants within keratinocytes: a cause for antibiotic treatment failure in a patient with Darier's disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1643-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Eiff, C., D. Bettin, R. A. Proctor, B. Rolauffs, N. Lindner, W. Winkelmann, and G. Peters. 1997. Recovery of small colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus following gentamicin bead placement for osteomyelitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 25:1250-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Eiff, C., A. W. Friedrich, K. Becker, and G. Peters. 2005. Comparative in vitro activity of ceftobiprole against staphylococci displaying normal and small-colony variant phenotypes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4372-4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Eiff, C., C. Heilmann, R. A. Proctor, C. Woltz, G. Peters, and F. Gotz. 1997. A site-directed Staphylococcus aureus hemB mutant is a small-colony variant which persists intracellularly. J. Bacteriol. 179:4706-4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]