Abstract

Saccharomyces cerevisiae squalene epoxidase contains two highly conserved motifs, 1 and 2, of unknown function. Amino acid substitutions in both regions reduce enzyme activity and/or alter allylamine sensitivity. In the homology model, these motifs flank the flavin adenine dinucleotide cofactor and form part of the interface between cofactor and substrate binding domains.

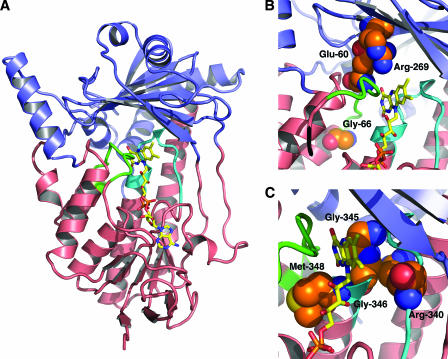

Squalene epoxidase (SE) is an essential flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent monooxygenase in sterol biosynthesis. The fungal enzyme is the target for the allylamines terbinafine and naftifine which inhibit SE in a noncompetitive manner (11). The homology model of SE (Erg1p) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (9) shows a two-domain structure typical for this class of flavin-dependent enzymes (12): the FAD binding domain (Fig. 1A, lower part, pink) with the characteristic nucleotide binding αβ-fold (1, 9, 13), and a second domain typically referred to asthe substrate binding domain (Fig. 1A, upper part, blue). The active site is at the interface of these domains.

FIG. 1.

Modeled structure of Erg1p from S. cerevisiae based on the crystal structure of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase. (A) Schematic representation of the three-dimensional model. The cofactor binding domain is shown in pink, the substrate binding domain in blue. The FAD cofactor is depicted as a yellow stick model. The two conserved regions are highlighted in green (motif-1) and cyan (motif-2). (B) Close-up view of motif-1. Amino acid side chains for which mutations are described in the text are displayed as CPK models (C, orange; N, blue; O, red). (C) Close-up view of motif-2. This figure was prepared using PyMol software (http://www.pymol.org).

We previously identified two interesting regions of SE, based on sequence conservation; the regions were denoted motif-1 and motif-2 (Fig. 1A, green and cyan) (10). To investigate the role of the motifs, scanning alanine mutagenesis was performed by two-step PCR. Subsequently, the respective erg1 alleles were cloned into the low-copy-number vector pRS315, and the recombinant plasmids were transformed into S. cerevisiae KLN1 (9). This mutant fails to express SE and consequently shows an aerobically lethal phenotype (5).

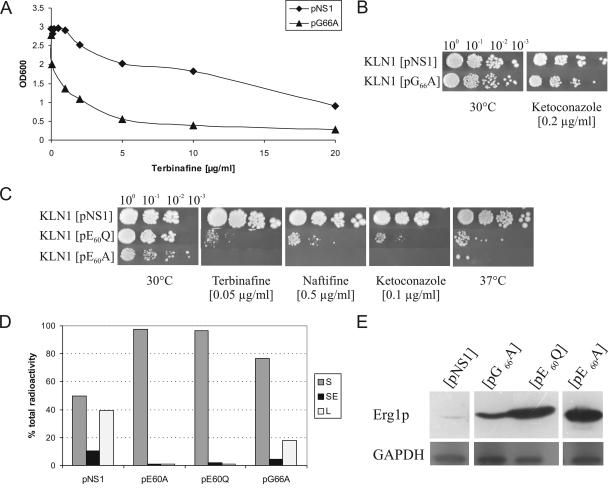

The amino acid sequence motif-1, 55DRIVGELMQPGG66, forms a loop at the interface between the FAD and the substrate binding domains (Fig. 1A, green). Alanine scanning of the eight conserved residues (in bold) gave rise to functional SEs. The most-pronounced alterations regarding sensitivity to antifungal compounds, enzyme activity, or protein levels were observed for SE with substitutions at residues E60 and G66.

The E60A variant poorly complemented growth of KLN1, drastically increased sensitivity to terbinafine and naftifine (>50-fold compared to that in the wild type) and ketoconazole (>5-fold), and conferred temperature-sensitive growth (Fig. 2C). Strongly reduced enzymatic activity was accompanied by increased Erg1p levels (Fig. 2D and E), as already demonstrated previously for other hypersensitive Erg1p variants (2, 9). E60 lies in a mechanistically sensitive region at the tip of the loop structure described above, near the cofactor and the putative active site (Fig. 1B). Therefore, we also generated an E60Q variant. This showed all the effects of the E60A variant, especially a reduced enzymatic activity which was accompanied by high Erg1p levels (Fig. 2C, D, and E). This indicates a potential role for the negatively charged E60 in the catalytic mechanism. In addition, the structural model indicates a possible electrostatic interaction with R269, an amino acid which is known to be specifically involved in allylamine sensitivity (9). This interaction could at least in part be complemented by hydrogen bonds to the glutamine in E60Q, accounting for the slight difference in drug sensitivity compared to E60A (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Properties of S. cerevisiae KLN1 expressing motif-1 Erg1p variants E60A and G66A in comparison to wild-type NS1. (A) Sensitivity to terbinafine in liquid medium. Optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured after 24 h at 30°C in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose medium supplemented with the indicated concentrations of terbinafine. (B and C) Spot assays. Serial dilutions of overnight cultures were spotted on yeast-peptone-dextrose agar plates containing the indicated inhibitor concentrations. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 30°C or 37°C. In each experiment, at least five concentrations of the respective inhibitor were tested; only one concentration is shown. (D) In vitro SE activity in cell extracts: sterol intermediate formation. Three milligrams of total protein in crude cell extracts was incubated with 14C-mevalonic acid and the cofactor-substrate mix. Lipid extracts were subjected to thin-layer chromatography analysis. Values of the lipid species (S, squalene; SE, squalene epoxide; L, lanosterol) represent the percentages of total radioactivity per lane. (E) Western blot analysis of Erg1p. Aliquots of whole-cell extracts were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-Erg1p antibodies and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibodies as a loading control, as described previously (8).

The G66A variant showed only slightly altered enzyme activity and protein levels (Fig. 2D and E) and an approximately 10-fold increase in sensitivity to terbinafine (Fig. 2A). However, this was not accompanied by a general sensitivity to other sterol biosynthesis inhibitors such as ketoconazole (Fig. 2B).

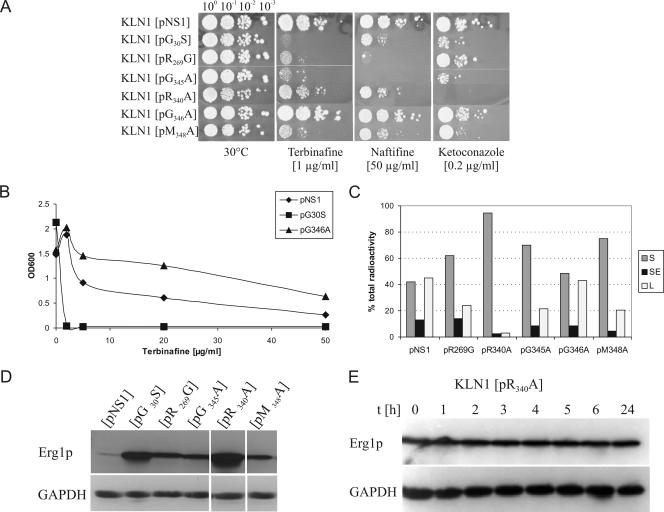

The conserved motif-2 (10), 338NMRHPLTGGGMTV350, is located close to the previously described FADII binding site (334GD335) (9) and the potential substrate binding residues identified in rat SE (7). This motif also forms a loop near the cofactor at the interface between the two domains of SE and is located opposite to motif-1 (Fig. 1A, cyan). Alanine scanning of all amino acids of motif-2 resulted in functional Erg1p variants. Only four amino acid substitutions (R340A, G345A, G346A, and M348A) lead to significantly altered phenotypes.

The variant R340A exhibited very low enzymatic activity (Fig. 3C). The steady-state protein levels were the highest of all mutants tested at present (Fig. 3D). This can in part be explained by the high stability of this SE variant, which shows no degradation within 24 h at 30°C compared to the 60-min half-life of wild-type Erg1p (9) (Fig. 3E). The homology model indicates that R340 may form a salt bridge with Glu432. This would tend to destabilize the protein, as typically observed for internal salt bridges (3). Therefore, a loss of the salt bridge might in part explain the increased protein stability. Low enzymatic activity of the R340A variant should lead to high sensitivity toward allylamines and ketoconazole, as already shown in other mutants, such as G30S (Fig. 3A) or L37P (8, 9). However, sensitivity of the R340A variant toward allylamines was increased only twofold (Fig. 3A). A likely explanation for these data is that a structural alteration in SE induced by this amino acid substitution interferes with allylamine binding.

FIG. 3.

Properties of S. cerevisiae KLN1 strains expressing Erg1p variants with alterations in motif-2 (R340A, G345A, G346A, and M348A) in comparison to the wild type (NS1) and the terbinafine-hypersensitive G30S and R269G variants. For details see the Fig. 2 legend. (A) Spot assay of the KLN1 strains expressing motif-2 variants in the presence of terbinafine, naftifine, and ketoconazole. (B) Growth of strain KLN1[G346A] in the presence of terbinafine after 24 h at 30°C. (C) In vitro SE activity in cell extracts: sterol intermediate formation. S, squalene; SE, squalene epoxide; L, lanosterol. (D) Western blot analysis of Erg1p variants. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as a loading control. (E) Stability of the Erg1p variant R340A. KLN1[R340A] was grown at 30°C in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose medium to early log phase. After addition of cycloheximide, 4 optical density at 600 nm (OD600) equivalents were removed at the indicated time points. Aliquots of whole-cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-Erg1p antibodies and anti-GAPDH antibodies as a loading control.

Substitution of G345 by alanine resulted in increased allylamine sensitivity without cross-sensitivity to ketoconazole, decreased enzyme activity, and induced Erg1p levels (Fig. 3A, C, and D). The G346A variant exhibited wild-type enzyme activity (Fig. 3C), steady-state protein levels (data not shown), and naftifine and ketoconazole sensitivity (Fig. 3A), but it was less sensitive toward terbinafine (Fig. 3B). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first mutation which confers terbinafine resistance without affecting an amino acid in the proposed terbinafine binding site on the surface of Erg1p (4, 6, 9).

The M348A variant was more sensitive toward terbinafine and naftifine and slightly more sensitive toward ketoconazole. Furthermore, enzyme activity was reduced and protein levels were induced (Fig. 3A, C, and D). In the model, the main chain amide group of M348 interacts with N1 of FAD, indicating that structural perturbations in this particular region are likely to affect enzyme activity.

Variants G66A (motif-1), G345A, and M348A (motif-2) confer increased allylamine sensitivity, similar to that observed with R269G (Fig. 3) (9). None of these amino acid residues lie in the presumed terbinafine binding site on the surface of Erg1p. This precludes direct interactions with the inhibitor. In the same way as R269G, we believe that these mutations facilitate conformational changes upon terbinafine binding which are required for noncompetitive inhibition. In order to prove this at the molecular level, the interaction of Erg1p and the inhibitor have to be measured directly. However, none of the enzyme variants is available in a purified form yet.

Together with our previous studies (8, 9), we have completed the characterization of all highly conserved motifs in fungal SEs. In the structural model, motif-1 and -2 (10) flank the FAD cofactor and form part of the interface between the cofactor and substrate binding domains (Fig. 1). The present data clearly show that specific mutations within these motifs do affect enzyme activity and sensitivity toward allylamines, thus underlining the structural and functional importance of the interface region.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Stütz, Novartis Forschungsinstitut, Vienna, Austria, for terbinafine and naftifine and T. Skern for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was financially supported by Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung, projects P14415 (to F.T.) and W901 (DK Molecular Enzymology to K.G.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 January 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eppink, M. H., H. A. Schreuder, and W. J. Van Berkel. 1997. Identification of a novel conserved sequence motif in flavoprotein hydroxylases with a putative dual function in FAD/NAD(P)H binding. Protein Sci. 6:2454-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Germann, M., C. Gallo, T. Donahue, R. Shirzadi, J. Stukey, S. Lang, C. Ruckenstuhl, S. Oliaro-Bosso, V. McDonough, F. Turnowsky, G. Balliano, and J. T. Nickels, Jr. 2005. Characterizing sterol defect suppressors uncovers a novel transcriptional signaling pathway regulating zymosterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 280:35904-35913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendsch, Z. S., and B. Tidor. 1994. Do salt bridges stabilize proteins? A continuum electrostatic analysis. Protein Sci. 3:211-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klobucnikova, V., P. Kohut, R. Leber, S. Fuchsbichler, N. Schweighofer, F. Turnowsky, and I. Hapala. 2003. Terbinafine resistance in a pleiotropic yeast mutant is caused by a single point mutation in the ERG1 gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 309:666-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landl, K. M., B. Klosch, and F. Turnowsky. 1996. ERG1, encoding squalene epoxidase, is located on the right arm of chromosome VII of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 12:609-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leber, R., S. Fuchsbichler, V. Klobucnikova, N. Schweighofer, E. Pitters, K. Wohlfarter, M. Lederer, K. Landl, C. Ruckenstuhl, I. Hapala, and F. Turnowsky. 2003. Molecular mechanism of terbinafine resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3890-3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee, H. K., Y. F. Zheng, X. Y. Xiao, M. Bai, J. Sakakibara, T. Ono, and G. D. Prestwich. 2004. Photoaffinity labeling identifies the substrate-binding site of mammalian squalene epoxidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 315:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruckenstuhl, C., A. Eidenberger, S. Lang, and F. Turnowsky. 2005. Single amino acid exchanges in FAD-binding domains of squalene epoxidase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae lead to either loss of functionality or terbinafine sensitivity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:1197-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruckenstuhl, C., S. Lang, A. Poschenel, A. Eidenberger, P. K. Baral, P. Kohut, I. Hapala, K. Gruber, and F. Turnowsky. 2007. Characterization of squalene epoxidase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by applying terbinafine-sensitive variants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:275-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruckenstuhl, C., R. Leber, and F. Turnowsky. 2005. Squalene epoxidase as drug target, p. 35-51. In R. M. Mohan (ed.), Research advances in antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, vol. 5. Global Research Network, Kerala, India. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryder, N. S., and M. C. Dupont. 1985. Inhibition of squalene epoxidase by allylamine antimycotic compounds. A comparative study of the fungal and mammalian enzymes. Biochem. J. 230:765-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schreuder, H. A., P. A. Prick, R. K. Wierenga, G. Vriend, K. S. Wilson, W. G. Hol, and J. Drenth. 1989. Crystal structure of the p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase-substrate complex refined at 1.9 A resolution. Analysis of the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-product complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 208:679-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wierenga, R. K., P. Terpstra, and W. G. Hol. 1986. Prediction of the occurrence of the ADP-binding beta alpha beta-fold in proteins, using an amino acid sequence fingerprint. J. Mol. Biol. 187:101-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]