Abstract

The objective of this work was to study the effect of ecophysiological factors on fumonisin gene expression and growth in Fusarium verticillioides. The effects of ionic and nonionic solute water potentials, matric potential, and temperature on in vitro mycelial growth rates and on expression of the FUM1 gene, involved in fumonisin biosynthesis, were examined. FUM1 transcript levels were quantified using a specific real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) protocol. Low temperature and water stress reduced fungal growth. Water stress increased FUM1 transcript levels, especially in the case of stress caused by nonionic solute. The temporal kinetic assays showed that water stress had opposite effects on fungal growth versus FUM1 expression. These results indicate that water stress may be an important factor for fumonisin accumulation, particularly in the later phases of maize colonization when water availability decreases. The quantitative RT-PCR methods described here provide a valuable tool for investigating the ecophysiological basis for fumonisin gene expression and ultimately may lead to more effective control strategies for this important mycotoxigenic pathogen.

During the life cycle of Fusarium verticillioides in maize, the pathogen colonizes soil and survives effectively on crop residue and spores are dispersed predominantly via rain splash and sometimes by wind. The pathogen's life cycle is significantly influenced by environmental factors, especially water availability and temperature (14). In terrestrial ecosystems, water availability can be expressed by the total water potential (Ψt), a measure of the fraction of the total water content available for microbial growth in pascals (10). This is the sum of three factors: (i) osmotic or solute potential (Ψs) due to the presence of ions or other solutes, (ii) matric potential (Ψm) due directly to forces required to remove water bound to the matrix (e.g., soil), and (iii) turgor potential of microbial cells balancing their internal status with the external environment. The influences of both Ψs and Ψm were of interest in this study because growth on crop residue and in ripening silks is determined predominantly by tolerance to solute potential, while growth in soil is determined mainly by matric potential, except in saline soils. The effects of ionic and nonionic Ψs stress on germination, growth, and fumonisin production by strains of F. verticillioides and Fusarium proliferatum have been determined in vitro and in stored maize grain (13). However, no information is available on the effect of soil Ψm water stress and how F. verticillioides responds to such stress in terms of growth capability and production of fumonisins.

Fungi vary in their ability to tolerate Ψm stress. For example, basidiomycetes such as Rhizoctonia solani and the cultivated mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus ostreatus) are very sensitive to matric forces compared to ionic or nonionic Ψs stress (1, 11). Interestingly, xerotolerant mycotoxigenic species such as Aspergillus ochraceus were found to be as tolerant of Ψm as Ψs stress (18). In contrast, aflatoxigenic and nonaflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus strains were found to be much more sensitive (15). More recently, Ramirez et al. (17) showed that Fusarium graminearum strains were able to germinate and tolerate a wide range of Ψm stress conditions. Macroconidia of F. culmorum have also previously been shown to be more tolerant than many other soilborne fungi in being able to germinate and grow under Ψm stress (8). Although there is information on the relationship between environmental factors, growth, and quantified mycotoxin production for a number of species (19), there have been few attempts to relate these responses to expression of genes involved in mycotoxin production.

Fumonisin production has been shown to be positively related to the expression of the FUM1 gene, whose regulation occurs at the transcriptional level (16, 20). Recent reports indicate significant correlation between FUM1 transcripts, quantified by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), and phenotypic fumonisin production (6, 7). The quantitation of FUM1 transcripts by real-time RT-PCR permits a sensitive and specific approach to evaluate the effects of various treatments on fumonisin biosynthesis.

The objectives of this study were (i) to compare the effects of Ψs (ionic and nonionic) and Ψm stress and temperatures on growth and relative FUM1 gene expression and (ii) examine the temporal kinetics of the effect of ionic Ψs stress on growth and FUM1 gene expression. These relationships are important as they clarify the ecophysiological basis for the establishment and survival in crop residue and for subsequent spread and infection of maize.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal isolates.

Two F. verticillioides strains, FvMM7-3 (FvA) and FvMM1-2 (FvB), were used. Both strains were originally isolated from a maize field in Madrid, Spain, in September 2003. Analysis of the partial sequences of IGS (intergenic region of ribosomal DNA units) and the EF-1α gene (elongation factor 1α) and the mating-type allele present indicated that these two strains were different haplotypes (Jurado et al., unpublished data). Cultures were maintained on potato dextrose agar medium (Scharlau Chemie, Barcelona, Spain) at 4°C and stored as spore suspensions in 15% glycerol at −80°C.

Growth in relation to osmotic potential and Ψm.

The medium used in this study was a fumonisin-inducing solid agar medium previously used (7), which contained malt extract (0.5 g/liter), yeast extract (1 g/liter), peptone (1 g/liter), KH2PO4 (1 g/liter), MgSO4·7H2O (0.3 g/liter), KCl (0.3 g/liter), ZnSO4·7H2O (0.05 g/liter), CuSO4·5H2O (0.01 g/liter), fructose (20 g/liter), and bacteriological agar (15 g/liter).

The Ψs was modified with the ionic solute sodium chloride (NaCl) and the nonionic solute glycerol to −2.8, −7.0, and −9.8 MPa of Ψ = water activities (aw) of 0.98, 0.95, and 0.93, respectively. These solutes were not added to the control medium (−1.4 MPa = aw of 0.995). All treatments and replicate agar media were overlaid with sterile cellophane sheets (P400; Cannings, Ltd., Bristol, United Kingdom) before inoculation to facilitate removal of the fungal biomass for RNA extractions.

The media were modified to different Ψm with polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000) to obtain treatments of −3.0, −7.0 and −10 MPa (aw of 0.982, 0.955, and 0.937, respectively). PEG 8000 is known to act predominantly by matric forces (21). For matrically modified treatments, the agar was omitted and sterile circular discs of capillary matting (Nortene; 8.5 cm in diameter, 2 mm thick) and sterile polyester discs were used to provide support for fungal growth. The capillary matting and polyester discs were overlaid with the sterile cellophane sheets. The control medium was similarly prepared, except that the PEG 8000 was omitted.

Inoculation, incubation, and growth assessment.

A 3-mm-diameter agar disk from the margin of a 7-day-old growing colony of each isolate grown at 25°C was used to centrally inoculate each replicate and treatment. The plates were incubated at either 15 or 25°C for 10 days, and the experiment consisted of a fully replicated set of treatments with at least three replicates per treatment. Experiments were repeated once.

Assessment of growth was made daily during the 10-day incubation period. Two diameters of the growing colonies were measured at right angles to each other until the colony reached the edge of the plate. The radii of the colonies were plotted against time, and a linear regression was applied to obtain the growth rate as the slope of the line.

An additional temporal experiment was carried out with strain FvA. This was grown on the same fumonisin-inducing agar medium, in which the Ψs was modified ionically with NaCl to −3.0, −7.0, and −10 MPa and incubated at 25°C for 3, 6, 9 and 12 days. Three independent replicates were destructively sampled at each time point and analyzed.

RNA isolation and RT.

The biomass was removed from the cellophane at the end of the incubation period, and the total RNA was extracted using the “Total Quick RNA cells and tissues” kit (Talent, Italy), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and stored at −80°C. DNase I treatment was used to remove genomic DNA contamination from the samples using “DNase I, amplification grade” (Invitrogen; United Kingdom), following the manufacturer's instructions.

First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the “GeneAmp Gold RNA PCR reagent kit” (Applied Biosystems). Each 20-μl reaction mixture contained 500 ng of total RNA, 0.5 μl of oligo(dT)16 (50 μM), 10 μl of 5× RT-PCR buffer, 2 μl of MgCl2 (25 mM), 2 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) (10 mM), 2 μl of dithiothreitol (100 mM), 0.5 μl (10 U) of RNase inhibitor (20 U/μl), 0.3 μl (15 U) of MultiScribe reverse transcriptase (50 U/μl), and sterile diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water up to the final volume. Synthesis of cDNA was performed in a Mastercycler gradient thermal cycler (Eppendorf; Germany) according to the following procedure. After a hybridization step of 10 min at 25°C, RT was carried out for 12 min at 42°C. The cDNA samples were kept at −20°C. Samples incubated in the absence of reverse transcriptase were used as controls.

Real-time RT-PCR and quantitative analysis of the data.

Real-time RT-PCR was used to amplify FUM1 and β-tubulin (TUB2) genes in both strains of F. verticillioides using the primer pair PQF5-F (5′ GAGCCGAGTCAGCAAGGATT 3′) and PQF5-R (5′ AGGGTTCGTGAGCCAAGGA 3′) and the primer pair PQTUB-F2 (5′ ACATCCAGACAGCCCTTTGTG 3′) and PQTUB-R2 (5′ AGTTTCCGATGAAGGTCGAAGA 3′), as described previously (7). Real-time RT-PCRs were performed using an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The PCR thermal cycling conditions for both genes were as follows: an initial step at 95°C for 10 min and 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and at 60°C for 1 min. SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) was used as the reaction mixture, with the addition of 2.6 μl of sterile Milli-Q water, 1.2 μl of each primer (5 μM), and 5 μl of template cDNA, in a final volume of 20 μl. In all experiments, appropriate negative controls containing no template were subjected to the same procedure to exclude or detect any possible contamination or carryover. Each sample was amplified twice in every experiment.

The results were normalized using the TUB2 cDNA amplifications run on the same plate. The TUB2 gene is an endogenous control that was used to normalize quantitation of mRNA target for differences in the amount of total cDNA added to each reaction. In real-time RT-PCR analysis, quantification is based on the threshold cycle (CT), which is defined as the first amplification cycle at which the fluorescence signal is greater than the minimal detection level, indicating that PCR products become detectable. Relative quantitation is the analytic method of choice for this study (4). In this method, a comparison within a sample is made with the gene of interest (FUM1) to that of the endogenous control gene (TUB2). Quantitation is relative to the control gene by subtracting the CT of the control gene from the CT of the gene of interest (ΔCT). In graphic representations (Fig. 2 and 3), we have used the average ΔCT value of the three replicates performed in each experiment, and this was subtracted by the calibrator value to obtain the corresponding ΔΔCT values. ΔΔCT values were transformed to log2 (due to the doubling function of PCR) to generate the relative expression levels.

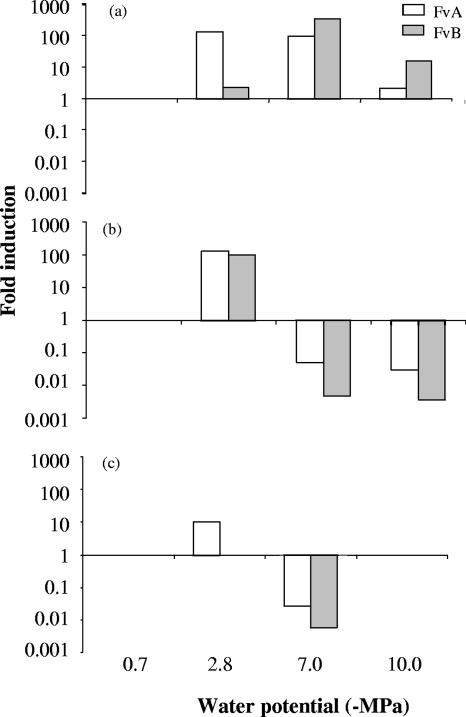

FIG. 2.

Comparison of induction of FUM1 expression in response to nonionic (glycerol) (a) and ionic (NaCl) (b) Ψs and Ψm (c) in Fusarium verticillioides strains FvA and FvB at 25°C in 10-day-old cultures. The measured quantity of the cDNA in each experiment was normalized using CT values obtained for TUB2 cDNA amplifications run on the same plate. The values represent the number of times FUM1 is expressed in each experiment compared to its respective control values (−0.7 MPa) for both FvA and FvB strains (set at 1.00). The results are averages of three independent repetitions.

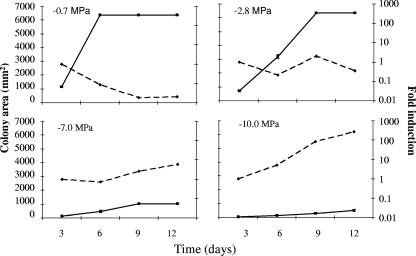

FIG. 3.

Temporal kinetic study of the effect of ionic (NaCl) Ψs on relative colony size (▪) and induction of FUM1 gene expression (♦) of strain FvA at 25°C at four different aw levels. The measured quantity of the cDNA in each of the experiments was normalized using the CT values obtained for the TUB2 cDNA amplifications run on the same plate. The values represent the number of times FUM1 is expressed in each experiment compared to its respective 3-day-old culture of the FvA strain (set at 1.00). The results are averages of the three independent repetitions.

Statistical analysis of results.

The linear regression of increase in radius against time (days) was used to obtain growth rates (mm day−1) as indicated above for each set of treatments. Statistical analysis of FUM1 gene expression included the data of the three replicates from each experiment. Both sets of results were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using StatsGraphics Plus V.5.1 (Statistical Graphics Corp., Herndon, VA).

RESULTS

Effects of temperature, Ψs, and Ψm on growth.

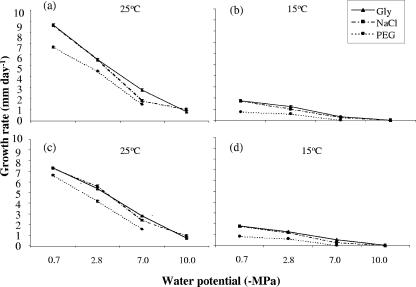

Figure 1 shows the relative growth rates of the two isolates of F. verticillioides on fumonisin-inducing agar medium in response to Ψs (ionic and nonionic) and Ψm stress at 25 and 15°C. The growth rate was markedly reduced at 15°C. At this temperature, no growth occurred in the Ψm treatments at −7.0 and −10.0 MPa. An ANOVA was separately performed at both temperatures to analyze the effect of the single factors considered in the study (isolate, water stress, and type of water stress) on growth rate, as well as two- and three-way interactions. All of these factors and their interactions showed significant effects at both temperatures, except the interaction among the strain, Ψ, and Ψ type at 25°C (Tables 1 and 2). Growth rates were comparable or slightly lower in response to ionic and nonionic Ψs stress. Ψm stress imposition caused a higher and significant reduction in growth rate regardless of temperature treatment or strain used compared to solute stress (data not shown). Both strains showed similar patterns of decrease in growth rate; however, the differences were statistically significant.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of growth rates of Fusarium verticillioides strains FvA (a and b) and FvB (c and d) in response to nonionic (glycerol) and ionic (NaCl) Ψs and Ψm (PEG 8000) at 25°C and 15°C.

TABLE 1.

ANOVA of the effects of strain, Ψt, and type of water potential and their interactions on growth rate at 25°Ca

| Source of variation | df | Mean square | Fb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | 1 | 0.730 | 56.153* |

| Ψt | 3 | 146.662 | 11,277.404* |

| Ψ type | 2 | 7.970 | 612.851* |

| Strain vs Ψt | 3 | 1.059 | 81.432* |

| Strain vs Ψ type | 2 | 0.156 | 11.976* |

| Ψt vs Ψ type | 5 | 0.372 | 28.595* |

| Strain vs Ψt vs Ψ type | 5 | 0.350 | 26.915 |

Shown are the ANOVA results for the effects of strain (FvA and FvB), Ψt (−0.7, −2.8, −7.0, and −10.0 MPa), type of water potential (nonionic and ionic Ψs and Ψm), and their interactions on growth rate at 25°C.

Snedecor's F test. *, significant at P < 0.05.

TABLE 2.

ANOVA of the effects of strain, Ψt, type of water potential, and their interactions on growth rate at 15°Ca

| Source of variation | df | Mean square | Fb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | 1 | 0.059 | 18.652* |

| Ψt | 3 | 7.877 | 2,476.430* |

| Ψ type | 2 | 2.225 | 699.582* |

| Strain vs Ψt | 3 | 0.010 | 3.113* |

| Strain vs Ψ type | 2 | 0.009 | 2.881* |

| Ψt vs Ψ type | 5 | 0.171 | 53.853* |

| Strain vs Ψt vs Ψ type aw | 5 | 0.010 | 3.260* |

Shown are the results of ANOVA of the effects of strain (FvA and FvB), Ψt (−0.7, −2.8, −7.0, and −10.0 MPa), type of water potential (nonionic and ionic Ψs and Ψm), and their interactions on growth rate at 15°C.

Snedecor's F test. *, significant at P < 0.05.

Effects of temperature, osmotic potential, and Ψm on FUM1 gene expression.

Figure 2 shows the relative FUM1 gene expression of the two F. verticillioides strains cultured on fumonisin-inducing media for 10 days at 25°C in response to both Ψs and Ψm water stress. The ANOVA showed statistically significant effects for all of the factors considered, except when considering the strain and interactions between strain and type of Ψ (Table 3). Therefore, both strains showed similar patterns of responses to the treatments, but the effects of nonionic Ψs treatment in comparison with the ionic Ψs and Ψm stress treatments showed remarkable differences in FUM1 gene expression. An increase of FUM1 gene expression was observed in response to all water potentials when a nonionic Ψs stress was imposed (Fig. 2a). However, when ionic Ψs or Ψm stress was imposed (Fig. 2b and c), high induction of FUM1 was observed in response to slight water stress of −2.8 MPa but FUM1 gene expression was markedly decreased at lower water stress levels.

TABLE 3.

ANOVA of the effects of strain, Ψt, type of water potential, and their interactions on induction of FUM1 gene expression at 25°Ca

| Source of variation | df | Mean square | Fb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | 1 | 35,188.610 | 0.916 |

| Ψt | 3 | 141,253.453 | 3.679* |

| Ψ type | 2 | 175,702.621 | 4.576* |

| Strain vs Ψt | 3 | 135,309.847 | 3.524* |

| Strain vs Ψ type | 2 | 94,435.582 | 2.459 |

| Ψt vs Ψ type | 5 | 180,926.662 | 4.712* |

| Strain vs Ψt vs Ψ type | 5 | 124,496.730 | 3.242* |

Shown are the results of ANOVA of the effects of strain (FvA and FvB), Ψt (−0.7, −2.8, −7.0, and −10.0 MPa), type of water potential (nonionic and ionic Ψs and Ψm), and their interactions on induction of FUM1 gene expression at 25°C.

Snedecor's F test. *, significant at P < 0.05.

The standard error of the mean values of the two amplifications performed for each sample were generally very low (about 0.12%) and never higher than 2%, indicating the high reproducibility of the real-time RT-PCR assay.

Effect of osmotic potential on temporal FUM1 gene expression.

Figure 3 shows the effect of ionic Ψs on growth rates, expressed as area of fungal growth, and induction of FUM1 expression of strain FvA at 25°C after 3, 6, 9, and 12 days. The results indicated increasing FUM1 mRNA synthesis over time in response to increasing ionic Ψs stress of −7.0 and −10 MPa, while a decrease was observed in the control medium. In the case of −2.8 MPa, FUM1 mRNA synthesis was maintained during the course of the experiment.

DISCUSSION

This study compared the effects of Ψs and Ψm stress on the growth of F. verticillioides. The results obtained have shown that this species is more tolerant of both ionic and nonionic Ψs stress than Ψm stress. These results are similar to those obtained for F. graminearum (17). In contrast, studies with F. culmorum suggest that germination and growth are affected to a similar degree by both types of water stress (8). This may be important when considering the life cycle of F. verticillioides in the maize pathosystem. Effective growth in soil and colonization of crop debris is a critical phase which determines the reservoir of inoculum for infection. It appears that colonization of soil may occur under a narrower range of water potentials than that on crop debris. Water stress and low temperature produced a drastic effect on fungal growth, in agreement with a previous report (12). The highest incidence of F. verticillioides in maize in southern European countries, in particular in central and south Spain where we have performed some studies (5, 6), might be related to the environmental conditions in these regions. The final stages of maize cultivation, prior to harvest, take place during August when temperature is high and humidity is extremely low. Although maize was not a traditional crop in central and south Spain, new varieties and new cultivation methods allow efficient cultivation of maize in these areas. The environmental conditions in these areas are clearly different from those of northern regions with lower temperatures and higher humidity.

The response of the two different strains analyzed showed a similar pattern in all cases. However, the differences were statistically significant, suggesting some intraspecific variability may exist in response to stress challenges. This could be related to the differences in aspects such as the ability to synthesize and accumulate compatible solutes which might reduce the negative effect of environmental stress (9) and, therefore, be of selective relevance under natural conditions.

There have been practically no attempts to relate environmental factors to quantitative gene expression in mycotoxigenic spoilage fungi. Our study has shown that there is a significant impact of interacting environmental factors on the FUM1 transcript levels. There was increased upregulation under certain stress conditions, while under others there was downregulation in relation to control treatments.

López-Errasquin et al. (7) demonstrated a very good linear regression between FUM1 transcript levels and fumonisin B1 production, using real-time RT-PCR. Recently, some elegant studies related the impact of environmental conditions on induction of ochratoxin A (OTA) biosynthesis genes in Penicillium nordicum (3). Real-time RT-PCR specific for the OTA polyketide synthase gene for P. nordicum (Pnotapks) demonstrated the induction of the transcription factor correlated with biosynthesis of OTA. The effects of temperature, pH, and ionic solute concentration all showed parallel expression of the Pnotapks gene and OTA production, although the temperature effects were relatively less pronounced. It was speculated that temperature has less effect on Pnotapks gene expression, even though it does have an impact on OTA production. However, the maximum amount of ionic Ψs stress imposed was 50 g/liter, which only equates to about −4.0 MPa. Penicillium species, especially P. nordicum and P. verrucosum, can grow and produce OTA also below this water potential (2, 19).

In the case of FUM1, transcript levels seemed to be influenced by water stress, although the effect seemed to depend on the type of water stress applied. Previous studies have suggested that a decrease of water availability to −2.8 MPa significantly reduces growth and induces the highest accumulation of fumonisins in vitro (12). Our results show that under such mild water stress conditions, the induction of FUM1 expression follows this pattern. In the case of nonionic Ψs stress treatment (glycerol), induction was maintained under even drier conditions. Previous reports demonstrated that mycelial growth was more sensitive to ionic than nonionic Ψs solute stress. This might be due to differential accumulation of certain polyols which enable biochemical and enzymatic (and gene expression) functions to continue inside the growing fungus (15, 17). In the case of P. nordicum, however, increasing concentrations of NaCl resulted in stimulation of mycelial growth and OTA synthesis (3).

The contribution of water stress to the induction of the fumonisin biosynthesis was more clearly suggested by the results of the temporal kinetic study where fungal growth and FUM1 gene expression were compared. The results indicated some level of independence of growth rate and FUM1 expression, since an increase in fungal biomass involved higher or lower FUM1 expression depending on the water stress imposed. At longer exposure times and higher water stress values (−0.7 and −10.0 MPa) an increase of FUM1 expression was observed, with maximum induction at 12 days. Interestingly, the FUM1 gene expression decreased progressively or was maintained under mild water stress levels (−0.7 and −2.8 MPa) and coincided with higher growth rates. This seems to suggest that conditions of mild water stress (−2.8 MPA) are expected to contribute to fumonisin accumulation. This could result in significant toxin accumulation over time without concomitant increases in fungal biomass. Under natural conditions, the water stress progressively increasing during kernel maturation might be a critical factor affecting fumonisin accumulation by F. verticillioides. Additionally, environmental conditions might affect the length of the water stress period, influencing the total fumonisin accumulation, and, therefore, fungal biomass would not be a reliable indicator of fumonisin contamination. More information about the relationship between FUM1 gene expression and fumonisin production is needed to predict fumonisin contamination of maize and develop effective control strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Spanish MCYT (AGL-2004-07549-C05-05). M.J. and P.M. were also supported by FPI fellowships of the Spanish MCYT.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 February 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beecher, T. M., N. Magan, and K. S. Burton. 2000. Osmotic/matric potential affects mycelial growth and endogenous reserves in Agaricus bisporus, p. 455-462. In L. J. L. D. Van Griensven (ed.), Science and cultivation of edible fungi. Balkema, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

- 2.Cairns-Fuller, V., D. Aldred, and N. Magan. 2005. Water, temperature and gas composition interactions affect growth and ochratoxin A production by isolates of Penicillium verrucosum on wheat grain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 99:1215-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geisen, R. 2004. Molecular monitoring of environmental conditions influencing the induction of ochratoxin A biosynthesis genes in Penicillium nordicum. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 48:532-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginzinger, D. G. 2002. Gene quantification using real-time quantitative PCR: an emerging technology hits the mainstream. Exp. Hematol. 30:503-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jurado, M., C. Vázquez, E. López-Errasquín, B. Patiño, and M. T. González-Jaén. 2004. Analysis of the occurrence of Fusarium species in Spanish cereals by PCR assays, p. 460-464. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium of Fusarium Head Blight incorporating the 8th European Fusarium Seminar 2004, Wagenigen, The Netherlands.

- 6.Jurado, M. 2006. “Análisis y diagnóstico de especies de Fusarium productoras de toxinas, y su presencia en cereales españoles.” Ph.D. thesis. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain.

- 7.López-Errasquín, E., C. Vázquez, M. Jiménez, and M. T. González-Jaén. 2007. Real-time RT-PCR assay to quantify the expression of FUM1 and FUM19 genes from the fumonisin-producing Fusarium verticillioides. J. Microbiol. Methods 68:312-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magan, N. 1988. Effect of water potential and temperature on spore germination and germ tube growth in vitro and on straw leaf sheaths. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 90:97-107. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magan, N. 2001. Physiological approaches to improving ecological fitness of fungal biocontrol agents, p. 239-252. In T. M. Butt, C. W. Jackson, and N. Magan (ed.), Fungi as biocontrol agents: progress, problems and potential. Cabi BioSciences, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom.

- 10.Magan, N. 2007. Fungi in extreme environments, p. 85-103. In C. P. Kubicek and I. S. Druzhinia (ed.), The Mycota. IV. Environmental and microbial relationships. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 11.Magan, N., M. P. Challen, and T. J. Elliot. 1995. Osmotic, matric potential and temperature effects on vitro growth of Agaricus bisporus and A. bitorquis strains, p. 773-780. In T. J. Elliot (ed.), Science and cultivation of edible fungi. Balkema, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

- 12.Marin, S., V. Sanchis, and N. Magan. 1995. Water activity, temperature and pH effects on growth of Fusarium moniliforme and F. proliferatum isolates from maize. Can. J. Microbiol. 41:1063-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marin, S., N. Magan, A. J. Ramos, and V. Sanchis. 2004. Fumonisin-producing strains of Fusarium: a review of their ecophysiology. J. Food Prot. 67:1792-1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munkvold, G. P. 2003. Cultural and genetic approaches to managing mycotoxins in maize. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41:99-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neschi, A., M. Etcheverry, and N. Magan. 2004. Osmotic and matric potential effects on growth and compatible solute accumulation in Aspergillus section Flavi strains from Argentina. J. Appl. Microbiol. 96:965-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proctor, R. H., A. E. Desjardins, R. D. Plattner, and T. M. Hohn. 1999. A polyketide synthase gene required for biosynthesis of fumonisin mycotoxins in Gibberella fujikuroi mating population A. Fungal Genet. Biol. 27:100-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramirez, M. L., S. N. Chulze, and N. Magan. 2004. Impact of osmotic and matric water stress on germination, growth, mycelial water potentials and endogenous accumulation of sugars and sugar alcohols in Fusarium graminearum. Mycologia 96:470-478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramos, A. J., N. Magan, and V. Sanchis. 1999. Osmotic and matric potencial effects on growth, sclerotia and partitioning of polyols and sugars in colonies and spores of Aspergillus ochraceus. Mycol. Res. 103:141-147. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchis, V., and N. Magan. 2004. Environmental profiles for growth and mycotoxin production, p. 174-189. In N. Magan and M. Olsen (ed.), Mycotoxins in food: detection and control. Woodhead Publishing, Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 20.Seo, J., R. H. Proctor, and R. D. Plattner. 2001. Characterization of four clustered corregulated genes associated with fumonisin biosynthesis in Fusarium verticillioides. Fungal Genet. Biol. 34:155-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steuter, A. A., A. Mozafar, and J. R. Goodin. 1981. Water potential of aqueous polyethylene glycol. Plant Physiol. 67:64-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]