Abstract

The freshwater ciliate Tetrahymena sp. efficiently ingested, but poorly digested, virulent strains of the gram-negative intracellular pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Ciliates expelled live legionellae packaged in free spherical pellets. The ingested legionellae showed no ultrastructural indicators of cell division either within intracellular food vacuoles or in the expelled pellets, while the number of CFU consistently decreased as a function of time postinoculation, suggesting a lack of L. pneumophila replication inside Tetrahymena. Pulse-chase feeding experiments with fluorescent L. pneumophila and Escherichia coli indicated that actively feeding ciliates maintain a rapid and steady turnover of food vacuoles, so that the intravacuolar residence of the ingested bacteria was as short as 1 to 2 h. L. pneumophila mutants with a defective Dot/Icm virulence system were efficiently digested by Tetrahymena sp. In contrast to pellets of virulent L. pneumophila, the pellets produced by ciliates feeding on dot mutants contained very few bacterial cells but abundant membrane whorls. The whorls became labeled with a specific antibody against L. pneumophila OmpS, indicating that they were outer membrane remnants of digested legionellae. Ciliates that fed on genetically complemented dot mutants produced numerous pellets containing live legionellae, establishing the importance of the Dot/Icm system to resist digestion. We thus concluded that production of pellets containing live virulent L. pneumophila depends on bacterial survival (mediated by the Dot/Icm system) and occurs in the absence of bacterial replication. Pellets of virulent L. pneumophila may contribute to the transmission of Legionnaires’ disease, an issue currently under investigation.

Legionella pneumophila (the causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease in susceptible humans) is a gram-negative freshwater bacterium that has evolved as an intracellular pathogen of amoebae (17, 53). Rowbotham first recognized L. pneumophila to be an intracellular parasite of amoebae shortly after the isolation and identification of the “Legionnaires’ disease bacterium” from human patients by McDade et al. (reviewed in reference 45). Rowbotham (44) also described in detail the growth cycle of L. pneumophila in Acanthamoeba polyphaga, and his careful observations suggested that L. pneumophila is well adapted to infect amoebae. To grow inside amoebae L. pneumophila requires a functional Dot/Icm system (21, 48), a type IV secretion apparatus that allegedly delivers effector proteins required for phagocytosis-invasion, recruitment of phosphatidylinositol-4 phosphate, and initiation of intra-amoebal growth, as determined in Dictyostelium discoideum (27, 33, 52, 57).

In contrast to amoebae, the role that ciliates play as natural hosts of L. pneumophila is far from clear and remains controversial. On the one hand, it has been experimentally shown that the freshwater ciliate Tetrahymena pyriformis supports the multiplication of L. pneumophila at 35°C (3, 18, 19), and in fact the ability to grow in T pyriformis at 35°C was considered a marker of L. pneumophila virulence (18). On the other hand, L. pneumophila growth was restricted at 25°C in the same T. pyriformis strain (19) that was permissive at 30 to 35°C. Another study (54) showed that only Legionella longbeachae consistently grew in T. pyriformis at 30°C, whereas several strains of L. pneumophila (among several other Legionella species) showed inconsistent growth. In addition, L. pneumophila did not replicate in the ciliate Cyclidium in axenic culture (3). Finally, Tetrahymena vorax did not support the intracellular growth of L. pneumophila at 20 to 22°C (50). However, in all cases (even when no growth was observed) L. pneumophila ingested by ciliates survived within food vacuoles. For instance, whereas E. coli was digested in T. vorax, ingested L. pneumophila survived at 20 to 22°C, and food vacuoles containing live legionellae were retained for an extended period of several hours (50). In contrast, other Tetrahymena species readily expelled the live undigested legionellae into the extracellular milieu, generating a large number of free legionella-laden vesicles that accumulated as aggregates (38).

Rowbotham originally proposed the idea that legionella-laden vesicles produced by amoebae could constitute a large infectious unit that may be important for the transmission of Legionnaires’ disease (44). To date, legionella-laden vesicles, as well as legionella-infected amoebae, continue to be considered important epidemiological elements, either as infectious particles or as complex units that offer enhanced environmental survival (7, 8, 10). Given the apparent efficiency at which Tetrahymena sp. generates legionella-laden vesicles (38) and the potentially important role that these vesicles may play in the transmission of Legionnaires’ disease, the ciliate-mediated process of vesicle production was investigated in detail. We report here that the previously named vesicles are instead clusters of bacteria surrounded by bacterial debris and were thus renamed as pellets. The massive production of legionella-laden pellets by Tetrahymena sp. feeding on virulent L. pneumophila is a rapid process that occurs in the absence of bacterial replication and depends on a Dot/Icm system-mediated mechanism used by L. pneumophila to avoid digestion while in transit through the ciliate. Tetrahymena sp. is thus presented here as an efficient packager of virulent L. pneumophila in freshwater, and an experimental model to study the Dot/Icm-mediated mechanisms used by L. pneumophila to resist digestion in ciliates, in the absence of bacterial replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The L. pneumophila and E. coli strains used are listed in Table 1. All L. pneumophila strains were kept as frozen stocks at −80°C. In particular, frozen stocks of Lp02, Lp1-SVir, and JR-32 were made from crude lysates of infected HeLa cells after intracellular growth had taken place (24, 25). Strain ATCC 33216 was grown on buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar (BCYE [42]), whereas stocks of Lp1-SVir and JR-32 were grown on BCYE supplemented with 100 μg of streptomycin/ml. Strain Lp02 and its derivatives JV303, JV309, and JV918 were grown on BCYE containing streptomycin and thymidine (both at 100 μg per ml), and JV1133 and JV1170 were grown on BCYE containing streptomycin but no thymidine. All L. pneumophila strains and mutants from frozen stocks were grown on agar plates for 3 to 5 days at 37°C in a humid incubator. Bacteria from this primary growth on agar plates (mostly in stationary phase [24]) were used in feeding experiments. E. coli strain JM109, used in control feeding experiments, was grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates (46) at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Designation | Characteristics | Source (reference)a |

|---|---|---|

| L. pneumophila | ||

| Lp1-SVir | Philadelphia-1, virulent, streptomycin resistant | P. S. Hoffman (28) |

| JR-32 | Philadelphia-1, virulent derivative of the streptomycin-resistant strain AM511 | H. A. Shuman (37) |

| Lp02 | Philadelphia-1, virulent, thymidine auxotroph, streptomycin resistant | R. R. Isberg (4) |

| JV309 | Salt-tolerant, dotA mutant derivative of Lp02 | R. R. Isberg (5) |

| JV303 | Salt-tolerant, dotB mutant derivative of Lp02 | J. P. Vogel (56) |

| JV918 | ΔdotB derivative of Lp02 | J. P. Vogel (49) |

| JV1133 | JV918 carrying the empty plasmid vector pJB908 | J. P. Vogel (49) |

| JV1170 | JV918 carrying the complementing plasmid pJB1153 with a wild-type copy of dotB | J. P. Vogel (49) |

| 33216 | Dallas 1E, serogroup 5, subsp. fraseri | ATCC |

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | Rec− K-12 derivative, F′ [traD36 proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15] endA1 recA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi gyrA96 Δ(lac-proAB), shows the rK− phenotype | P. S. Hoffman (46) |

| DH5α | F− [φ80 lacZΔM15] ΔlacU169 supE44 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Clontech (46) |

Paul S. Hoffman is at the University of Virginia, Howard A. Shuman is at Columbia University, Ralph R. Isberg is at Tufts University Medical School, and Joseph P. Vogel is at the Washington University School of Medicine.

Bacterial transformation and complementation of the dotA mutant JV309.

A suspension of Lp02 (1011 bacteria/ml in distilled-deionized water [ddH2O]) was prepared from thin lawns grown overnight at 30°C on BCYE plates, washed twice in ddH2O, and resuspended to the same concentration in 15% (wt/wt) glycerol solution in ddH2O to produce electrocompetent cells. Plasmid pBH6119::htpAB (10 μg) was added to 400 μl of the Lp02 suspension in a 2-mm electroporation cuvette, and electroporated in a GenePulser II (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Plasmid pBH6119::htpAB is a variant of plasmid pflaG (26) in which the flaA promoter was replaced with the L. pneumophila htpAB promoter and was constructed by K. Brassinga (Dalhousie University) after the procedure reported by Hammer and Swanson (26) on the backbone plasmid pBH6119 (provided by M. S. Swanson, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor). The cuvette was placed on ice for 20 min before inoculating a series of BCYE agar plates containing 100 μg streptomycin/ml (but no thymidine), with 10, 100, and 200 μl of the electroporated suspension, to select for transformants expressing green fluorescent protein.

Calcium chloride-treated, competent E. coli DH5α cells (Table 1) were transformed with plasmid pDsRed2 (Clontech), and transformants constitutively expressing the red fluorescent protein were selected and grown at 37°C on LB agar containing 50 μg of ampicillin/ml.

Electrocompetent JV309 cells (prepared as described above for Lp02) were transformed by electroporation (as described above) with 10 μg of the complementing plasmid pKB9 (obtained from R. R. Isberg, Tufts University) carrying dotA (4, 5). The electroporated suspension was placed on ice for 20 min before inoculating 200 μl on a monolayer of L929 cells in a 10-cm-diameter tissue culture dish, to allow the formation of plaques (16). The bacterial inoculum was left overnight on the L929 cells (at 37°C in a humid CO2 incubator) before washing and overlaying the cell monolayer with 10 ml of agarose-solidified minimal essential medium. Three days after the first overlay, a second minimal essential medium overlay containing gentamicin (20 μg/ml) and neutral red (to a final concentration of 0.003%) was added. Two days after the second overlay, plugs of agarose containing bacteria from individual visible plaques were cut with glass Pasteur pipettes and then transferred to wells containing fresh HeLa cell monolayers to confirm the ability to grow intracellularly in the absence of thymidine. Colonies from BCYE plates inoculated with infected HeLa cells were confirmed to carry the pKB9 plasmid by the method of Kado and Liu (31).

Ciliate culture, maintenance, and identification.

Tetrahymena sp. was intentionally isolated from a cooling tower biofilm to test a nonamoebic protozoan model relevant to the ecology of L. pneumophila in man-made aquatic environments. The sampled biofilm was dispersed and cultured in a sterile petri dish containing cereal leaves medium, prepared by boiling 1 g of dehydrated cereal leaves (Sigma [St. Louis, MO] catalogue no. C7141) in 1 liter of distilled water for 15 min, followed by filtration through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane and autoclaving. All biofilm protozoa were then grown and maintained in 25-cm2 cell culture flasks (Falcon Plastics) containing 10 ml of cereal leaves medium from which individual cells were captured with fine-bore Pasteur pipettes with the aid of a microscope. Individual cells were successively transferred in depression slides until a single ciliate cell was observed per slide. A clonal isolate of Tetrahymena sp. was expanded and maintained in cereal leaf medium and subsequently made axenic by repeated subculture (three times a week for 2 weeks) in medium supplemented with 200 U of penicillin/ml, 200 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 25 μg of gentamicin/ml. Axenic Tetrahymena sp. was initially maintained in cereal leaves medium without antibiotics at 25°C before adopting the maintenance procedures outlined by Elliot (14) as follows. Line A was maintained at 18°C in tubes containing a biphasic medium consisting of 5 ml of a slanted solid phase (in g/liter: dextrin, 8; sodium acetate trihydrate, 0.6; Autolized Yeast [Difco], 5; liver concentrate [Sigma], 0.6; Bacto Casitone [Difco], 3; Casamino Acids [Difco], 2; agar, 16; pH 7.3) covered with ∼3 ml of sterile ddH2O. This line was subcultured every 2 to 3 months. Line B was maintained in the described biphasic medium, but was kept at room temperature (22 to 24°C) and subcultured every 2 to 3 weeks. Line C (the working culture) was kept in plate count broth (Difco) at 30°C and subcultured weekly. Every 4 to 6 months (depending on the robustness of its growth) line C was discarded and a new one started from line B. Line A served as a reserve culture of low manipulation and to start new line B cultures.

To confirm the identity of the ciliate as Tetrahymena sp., we opted to sequence the gene encoding the small ribosomal subunit RNA. Total Tetrahymena genomic DNA was purified by using the standard phenol-chloroform extraction method reported by Arroyo et al. for Trichomonas vaginalis (2). The final DNA pellet obtained after cold ethanol precipitation was resuspended in TAE buffer (46) and used as a template for amplification of the 18S rRNA gene by PCR in a Biometra T-Personal instrument using Medlin's universal eukaryotic forward primer 5′-ACCTGGTTGATCCTGCCAGT-3′ (39), and the reverse primer reported by Jerome et al., 5′-TTGGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACG-3′ (30). The amplification product was sequenced in-house in a Beckman-Coulter CEQ 8000 genetic analysis system (Dalgen; Dalhousie University), in both directions, using the above primers. The obtained sequence was then compared against the NCBI database using BLAST, and the most similar sequences were retrieved. Our isolate clustered in the T. tropicalis-T. mobilis clade, which is evolutionarily distanced from the T. pyriformis and T. vorax clade (the two Tetrahymena species used in previous studies with L. pneumophila [19, 50, 54]), as indicated by the phylogenetic tree constructed by Brandl et al. based on a subset of Tetrahymena 18S rRNA gene sequences (9).

Tetrahymena pyriformis ATCC 30202 was used as a reference ciliate in a few feeding experiments. T. pyriformis was cultured and maintained as described above for Tetrahymena sp.

Feeding experiments.

Before use in feeding experiments, Tetrahymena sp. cells were gradually transferred from their plate count broth growth medium into either raw cooling tower water filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size membrane (Millipore) or Tris-buffered Osterhout's solution (41, 51). That is, ciliates were sequentially pelleted at 700 × g for 10 min and resuspended in increasing concentrations (30, 60, and 100%) of filtered cooling tower water at room temperature or Osterhout's solution at 30°C. The use of raw cooling tower water was adopted to initially mimic the environment of isolation and was collected from the basin of the cooling tower from which the Tetrahymena sp. isolate was obtained, during the period of lowest biocide concentration. Due to confidentiality issues, the chemistry of the cooling tower water remained undefined; therefore, the adoption of Osterhout's solution facilitated the standardization of subsequent feeding experiments. Osterhout's solution contained (in mg/liter): NaCl, 420; KCl, 9.2; CaCl2, 4; MgSO4·7H2O, 16; MgCl2·6H2O, 34; and Tris base, 121 (pH 7.0). The solution was sterilized by filtration in a bottle-top filter of 0.45-μm pores (Nalgene). Based on the recorded in situ temperature range of cooling tower waters (6), our feeding experiments were initially set at 25°C in cooling tower water and later standardized to 30°C in Osterhout's solution. Bacteria were also washed and resuspended to an optical density at 620 nm of 1 unit, in either filter-sterilized cooling tower water or Osterhout's solution, before being used as inoculum for feeding experiments.

Plate-grown L. pneumophila strain 33216 and Tetrahymena sp. cells were washed and resuspended in cooling tower water to achieve various bacterium/ciliate ratios. The ciliate concentration (determined by direct microscopy of samples of known volume fixed with Lugol's iodine [1]) was kept constant at 104/ml, and different numbers of bacteria were added to achieve bacterium/ciliate ratios of 100, 1,000, and 10,000. After a 24-h incubation at 25°C, pellets produced were enumerated with a Brightline hemacytometer. Feeding experiments standardized at 30°C in Osterhout's solution were run for 48 h with various L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 strains in either six-well plates or 25-cm2 cell culture flasks. Samples were taken at different times to microscopically assess the numbers of live ciliates and free bacteria. Typically, the concentration of ciliates was 5 × 104/ml of Osterhout's solution, but feeding experiments with Lp02 dot mutants were done at a concentration of 104 Tetrahymena sp. cells per ml and a bacterium/ciliate ratio of 10,000.

Pulse-chase experiments with fluorescent bacteria.

L. pneumophila Lp02 carrying plasmid pBH6119::htpAB (displaying green fluorescence) and E. coli DH5α carrying plasmid pDsRed2 (displaying red fluorescence) were added to ciliate suspensions according to the following schemes: (i) a 1-h pulse of red fluorescent E. coli DH5α, followed by a chase with nonfluorescent E. coli DH5α; (ii) a 1-h pulse of red fluorescent E. coli, followed by a 3-h chase with green fluorescent L. pneumophila; and (iii) a 1-h pulse of green fluorescent L. pneumophila, followed by a chase with nonfluorescent L. pneumophila Lp02. The total bacterium/ciliate ratio for these experiments was kept at ∼10,000. The ciliates were separated from free bacteria (between pulse and chase changes) by centrifugation at a low speed (700 × g for 10 min), leaving most bacteria in the supernatant. These feeding experiments were set at 30°C in six-well plates (Falcon Plastics) with ∼0.5 million ciliates per well in 3 ml of Osterhout's solution.

Production of pellets for morphological characterization.

Tetrahymena cells (1.5 × 106) resuspended in 3 ml of Osterhout's solution were fed with ∼5 × 108 bacteria (bacterium/ciliate ratio of 333). These ciliate feeding experiments were set in six-well plates (Falcon Plastics) at 30°C. To obtain a sample enriched in pellets for microscopic observations, after an overnight incubation at room temperature (usually 16 to 18 h) the mixture of ciliates, free bacteria, and aggregated pellets was centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 min in 15-ml conical tubes (Falcon Plastics), and the live ciliates were allowed to swim back into suspension before removing the supernatant (containing live ciliates and free bacteria). The recovered pellets were resuspended in fresh Osterhout's solution. This operation was repeated three times before the pellet-enriched samples were prepared for various microscopy observations.

Enumeration of bacterial CFU in ciliate cultures.

A total of 106 ciliates in 25-cm2 cell culture flasks (Falcon) containing 30 ml of Osterhout's solution were fed with ∼3 × 1010 bacteria (obtained from 40 ml of either Lp1-SVir, Lp02, or JR-32 suspensions with an optical density at 620 nm of 1 unit) to provide a bacterium/ciliate ratio of 30,000. After 3 h at 30°C, the mixed suspension was treated with gentamicin (100 μg/ml) for 30 min, and then the ciliates were separated from the free bacteria and gentamicin by gentle filtration-washing (with Osterhout's solution) through Millipore membranes of 8.0-μm pores. The ciliates remaining on the filter (carrying ingested legionellae) were resuspended in 30 ml of Osterhout's solution by allowing them to freely swim for a few minutes at room temperature, followed by a very gentle agitation, and incubated at 30°C. Then, three 1-ml samples were taken at various times to perform CFU counts. Each 1-ml sample was placed in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min. The centrifugation pellet was resuspended with vigorous pipetting into 50 μl of 0.5% Triton X-100 in sterile ddH2O, and 450 μl of ddH2O was added, followed by vigorous vortexing for 1 min. The sample was then brought to 1 ml with ddH2O, before 10-fold serial dilutions were performed. Aliquots (100 μl) of the 102 to 106 dilutions were spotted onto BCYE plates and incubated at 37°C for 4 to 5 days before the colonies were counted.

Light microscopy.

Ciliate cultures were routinely monitored by using a CK2 Olympus inverted microscope. Wet mounts of ciliates with ingested legionellae and fluorescent bacteria were observed in an Olympus BX6 upright microscope equipped with differential interference contrast (DIC), epifluorescence, and an Evolution QEi Monochrome digital camera (Media Cibernetics, San Diego, CA). Image capture and analysis (TIFF files) was performed with ImagePro software v.5.0 (Media Cibernetics). Viability of the legionellae within pellets was assessed by the BacLight LIVE/DEAD stain (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) in a Leica TCS-SL confocal microscope with an excitation argon laser of 488 nm and a barrier emission filter for 520 nm. Direct microscopy counts of free bacteria were done by using an internal standard (a suspension of 0.8-μm latex beads at a concentration of 3 × 109 per ml), following the procedures of Mallette (35).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Samples of Tetrahymena cells and pellets (prepared as described above) were taken at different times postinoculation to be fixed in glutaraldehyde, postfixed in osmium tetroxide, and embedded in epoxy resin for thin sectioning, followed by standard staining in uranium and lead salts, as described previously (15). Stained thin sections were observed in a JEOL JEM-1230 transmission electron microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA-HR high-resolution (2K by 2K) digital camera, and images were captured as TIFF files.

Immunogold labeling.

Pellets produced by Tetrahymena sp. fed with the Lp02 strain, and its derivatives JV303 (dotB mutant) and JV309 (dotA mutant) were fixed in freshly depolymerized paraformaldehyde, and embedded in LR-White resin as previously reported (23). Thin sections mounted on nickel grids were then immunostained with rabbit polyclonal sera (see below) and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to 10-nm gold spheres (Sigma Immunochemicals), as follows. Grids were sequentially floated for 10 min on drops of sodium borohydride (1 mg/ml) freshly dissolved in ddH2O and then 10 mM glycine dissolved in 100 mM sodium borate (pH 9). Blocking was done for 1 h on drops of labeling buffer (100 mM Tris, 0.2 M NaCl [pH 8]) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 1% skimmed milk. The grids were then sequentially floated for 1 h on drops of rabbit hyperimmune sera diluted 1:400 in labeling buffer containing 0.2% BSA and on drops of gold-conjugate diluted 1:100 in labeling buffer containing 0.2% BSA. After each antibody incubation, grids were washed three times by floating and rocking them for 10 min on 1-ml aliquots of wash buffer (100 mM Tris, 0.3 M NaCl [pH 8]) in 24-well plates. Finally, the labeled sections were floated on 2.5% glutaraldehyde in wash buffer, thoroughly rinsed in ddH2O, and stained with uranium and lead salts (15). Rabbit sera raised against the major outer membrane protein of L. pneumophila, OmpS, which is highly resistant to proteases (11, 29) or against the Hsp60 chaperonin (28), were obtained from Paul Hoffman (Dalhousie University).

RESULTS

Ingestion of legionellae by Tetrahymena sp. and pellet production.

Ciliates began to form and accumulate food vacuoles immediately after the addition of legionellae (Fig. 1). In the 24-h feeding experiments performed in filtered cooling tower water at 25°C, Tetrahymena sp. efficiently packaged L. pneumophila 33216 into pellets that were expelled to the extracellular milieu, but no pellets were produced in unfed ciliates. The average numbers of pellets/ciliate/h calculated for the complete 24-h period were 1, 2, and 5 at bacterium/ciliate ratios of 100, 1,000, and 10,000, respectively. Pellet formation was not dependent on the use of cooling tower water, since Tetrahymena sp. also produced pellets in subsequent 48-h experiments performed in Osterhout's solution at 30°C. In these conditions, ciliates were stable and maintained their high motility. In Osterhout's solution at 30°C, L. pneumophila strain Lp02 was ingested at the average rates of 1.5, 17, and 389 bacteria/ciliate/h, at bacterium/ciliate ratios of 100, 1,000, and 10,000, respectively. However, all of the above rates of ingestion and pellet production may not have been uniform over the full 48- or 24-h periods. These rates were likely higher in the early stages of feeding than later when the ciliates were bacterium-laden and the concentration of free bacteria had decreased. The shortest interval between bacterial addition to ciliates and the appearance of the first free pellets was ∼50 min, as determined by light and fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1). We also determined that pellets were not exclusively produced by Tetrahymena sp., since T. pyriformis produced pellets in Osterhout's solution at 30°C in a manner similar to that described above for Tetrahymena sp. (data not shown).

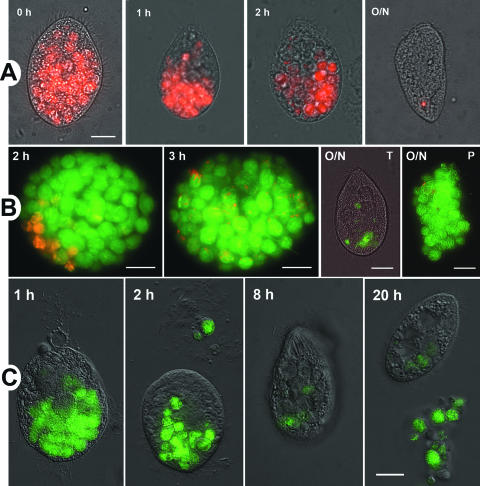

FIG. 1.

Early kinetics of L. pneumophila ingestion and pellet production. (A to D) Images of green fluorescent Lp02 overlaid on their corresponding DIC images of Tetrahymena cells. Samples were taken at the indicated times after addition of the bacterial inoculum to show the progressive formation and accumulation of food vacuoles. The arrowhead in panel A points to the clearly seen vestibulum of the cytopharynx, at the end of which a food vacuole seems to be forming. The arrowhead in panel D points to a pellet being expelled. The size bar in panel A represents 10 μm and applies to all panels.

After 30 to 50 min of feeding, ciliates assumed a round shape and maintained a relatively constant number of food vacuoles as they began to produce pellets, suggesting that the rates of food vacuole formation and discharge were balanced, as previously reported for other Tetrahymena species (12, 14). Bacterium/ciliate ratios of <100 were not studied, while legionellae concentrations of <106/ml were not conducive to pellet formation, regardless of the bacterium/ciliate ratio. It should be noted that pellet production at 35 to 37°C could not be tested because neither T. pyriformis ATCC 30202 nor our Tetrahymena isolate survived an overnight incubation at these elevated temperatures.

When ciliates were fed with E. coli strains JM109 or DH5α, no pellets were produced at bacterium/ciliate ratios of <1,000, but a few dispersed pellets were produced at ratios of >1,000, and no pellets were observed in unfed ciliates.

Morphological characterization of food vacuoles.

Tetrahymena sp. samples fixed 0.5, 1, 2.5, 4, 8, 13, or 24 h after inoculation with virulent Philadelphia-1 strains Lp1-Svir or Lp02 depicted similar ultrastructural features (Fig. 2). The number of food vacuoles per ciliate and the number of bacteria per vacuole were similar in all TEM samples, and all vacuoles contained membranous material (e.g., arrow in Fig. 2D). Although the appearance of food vacuoles varied (not all morphologies are shown), vacuoles with virtually identical features (like those shown in Fig. 2) were always found at all sampling times, and except for the 30-min sample, all other ciliate TEM samples depicted the different vacuole morphologies in similar proportions. Noticeably, ultrastructural features typical of bacterial cell division were absent in L. pneumophila cells contained in food vacuoles of different morphology and in samples taken at different feeding times. Collectively, these ultrastructural observations confirmed that a steady state of food vacuole formation and trafficking had been established as early as 0.5 to 1.0 h after inoculation. Unique structural features of the legionella-containing food vacuoles included the juxtaposition and/or warping of the vacuolar membrane to follow the outline of the contained bacteria (e.g., arrow in Fig. 2B) and the tight apposition of mitochondria (e.g., arrowhead in Fig. 2B), two features previously observed in L. pneumophila-infected mammalian cells (15) and in Tetrahymena vorax (50). Although present, these features were not obvious in the 0.5-h sample, confirming that their appearance was time dependent.

FIG. 2.

Examples of ultrastructural similarity between Tetrahymena sp. food vacuoles at different times postinoculation. Electron micrographs of single food vacuoles showing virtually identical features in ciliates fixed after 30 min (A), 4 h (B), 8 h (C), and 13 h (D) of feeding on L. pneumophila strain Lp1-SVir. The arrow in panel B points to a region with a marked warping of the vacuolar membrane (which follows the contour of the contained bacteria), and the arrowhead indicates a mitochondrion in tight apposition to the vacuolar membrane. The arrow in panel C points to a structurally degraded bacterial cell, and that in panel D points to the membranous material present in all food vacuoles. All size bars represent 0.5 μm.

Morphological characterization of expelled pellets.

The average pellet diameter, measured by light microscopy of 100 randomly selected pellets, was 4.2 ± 0.1 μm, with an estimated volume of 38.8 μm3. The smallest pellets had a diameter of ∼1 μm, and the largest had a diameter of ∼8 μm. Only 5% of the pellets were larger than 5 μm, 28% were 5 μm, 46% were 3 to 5 μm, and 21% were 1 to 3 μm in diameter, a size distribution that did not change significantly in pellets produced at different bacterium/ciliate ratios or with different L. pneumophila strains. Inferring a homogeneous width of 0.5 μm and a length of 2.0 μm (with an estimated bacterial cell volume of 0.36 μm3), the average pellet could theoretically accommodate ∼100 densely packed legionellae. Pellets depicted one of several ultrastructural morphologies (Fig. 3A). Some pellets consisted of tightly packed legionellae with an electron-translucent amorphous material and membrane fragments filling the spaces between bacterial cells (Fig. 3B), whereas other pellets contained fewer bacteria and a more abundant portion of interbacterial membranous material (Fig. 3C). It was observed that none of the pellets had a continuous membrane around them (to suggest that they were vesicles). Instead, pellets either lacked any defined boundary (Fig. 3D) or were bound by stacks of noncontinuous membrane fragments and/or an amorphous material (Fig. 3). The differences observed in pellet ultrastructure suggested that L. pneumophila had followed different intravacuolar fates, but regardless of their fate no TEM evidence of cell division of the legionellae found in the different pellets was forthcoming.

FIG. 3.

Expelled free pellets show one of several morphologies. (A) Low-magnification electron micrograph showing a group of sectioned pellets depicting different ultrastructural features. Features: 1, pellets containing tightly packed Lp02 cells held together by an amorphous material and membrane fragments; 2, pellets with membrane fragments between bacteria and wrapped around the pellet's surface; 3, pellet containing a few bacteria and abundant vesicular and membranous material; 4, pellet with no obvious peripheral or interbacterial binding material. Bar represents 2 μm. (B to D) High-magnification electron micrographs showing ultrastructural detail of a tightly packaged pellet (B), a pellet wrapped in membrane fragments (C), and a pellet lacking any apparent binding material (D). Bars represent 1.0 μm.

Food vacuole turnover in pulse-chase experiments.

To determine whether all food vacuoles followed a similar turnover rate, pulse-chase feeding experiments were performed with green fluorescent L. pneumophila and red fluorescent E. coli. When a 1-h pulse of red fluorescent E. coli was chased with nonfluorescent E. coli, a gradual polarization and decrease in the number of vacuoles containing red fluorescent bacteria was observed (Fig. 4A). After an overnight incubation, only a small number of ciliates (<10%) depicted a single spot of red fluorescence (Fig. 4A, panel O/N), and no expelled pellets containing red fluorescent bacteria were found, suggesting complete digestion. TEM confirmed the structural degradation of E. coli in food vacuoles and the presence of expelled membranous pellets (Fig. 5). When a 1-h pulse of red fluorescent E. coli was chased for 3 h with green fluorescent L. pneumophila, vacuoles containing red fluorescent E. coli were rapidly displaced by numerous vacuoles containing green fluorescent legionellae (Fig. 4B). After the 3-h chase with green fluorescent legionellae, all free bacteria were removed, and ciliates were incubated overnight in the absence of further feeding. Under these conditions most green fluorescent legionellae were expelled in pellets during the overnight incubation (Fig. 4B, panels O/N-T and O/N-P). Finally, when a 1-h pulse of green fluorescent Lp02 was chased with nonfluorescent Lp02, a rapid polarization and decrease in the number of fluorescent vacuoles was observed (Fig. 4C), as in the case of E. coli (Fig. 4A). However, in contrast to E. coli, a few intracellular vacuoles containing green-fluorescent legionellae remained after 20 h of feeding (Fig. 4C, 20 h). As previously suggested for Tetrahymena vorax (50), it is possible that Tetrahymena sp. retained L. pneumophila-laden food vacuoles longer than those containing E. coli, but the possibility of reingestion of free fluorescent legionellae (released from expelled pellets) cannot be ignored. These results suggest that feeding ciliates do not selectively retain vacuoles and that vacuole turnover remained steady.

FIG. 4.

Pulse-chase experiments suggest a steady and rapid turnover of food vacuoles in feeding ciliates. (A) Overlay images of red fluorescent E. coli DH5α and DIC images of Tetrahymena cells showing the chase phase of fluorescent E. coli with nonfluorescent E. coli at the times shown. Notice the polarized displacement of fluorescent vacuoles. The bar in the 0 h overlay represents 10 μm and applies to all images in panel A. (B) Overlay images of red fluorescent E. coli DH5α, chased by green fluorescent L. pneumophila Lp02. Only the chase phase is shown at the times indicated, where the O/N indicates an overnight incubation (∼16 h). T, Tetrahymena-associated fluorescence; P, pellet-associated fluorescence. DIC images of Tetrahymena cells or pellets were omitted (except for the O/N-T overlay) for visual clarity. Red fluorescent E. coli was not packaged into pellets, except for a few cells apparently copackaged with L. pneumophila (O/N-P). Size bars represent 10 μm. (C) Overlay images of green fluorescent L. pneumophila Lp02 and DIC images of Tetrahymena cells showing the chase phase of fluorescent L. pneumophila with nonfluorescent L. pneumophila at the times shown. The polarized displacement of vacuoles and the transfer of fluorescence to expelled pellets should be noted. The bar in the 20-h overlay represents 10 μm and applies to all images in panel C.

FIG. 5.

Tetrahymena efficiently digests E. coli cells. Transmission electron micrographs of intravacuolar E. coli JM109 showing signs of structural degradation (A) and a single dispersed pellet expelled by Tetrahymena feeding on E. coli DH5α showing no surviving bacterial cells and abundant membranous whorls (B). The size bars in panels A and B represent 500 nm.

Pellet formation is not associated with replication of L. pneumophila.

A lack of L. pneumophila replication in Tetrahymena sp. was strongly suggested by our TEM observations (Fig. 2) and previous reports indicating that Tetrahymena does not support the intracellular growth of L. pneumophila at temperatures of ≤30°C (19, 50). Therefore, the number of L. pneumophila CFU associated with ciliates that fed for 3 h on virulent legionellae was investigated. The initial number of CFU/ml (set after the 3-h feeding period followed by a 1-h gentamicin treatment to kill free extracellular bacteria) decreased ∼100-fold in 24 h for the SVir strain and ∼1,000-fold for the Lp02 strain (Fig. 6A and B). When this experiment was repeated with the L. pneumophila strain JR-32, we also observed a 100-fold reduction in total CFU/ml, and the graphs (not shown) followed a shape similar to that of Fig. 6A. Reductions in CFU counts were also observed for L. pneumophila ATCC 33216 in the presence of Tetrahymena sp. at 25°C (not shown). Because we estimated that the average-size pellet could contain up to a hundred L. pneumophila cells (see above), it is possible that the ∼100-fold decrease in CFU numbers observed for SVir and JR-32 simply reflected the effect of packaging. In fact, light microscopy indicated that most pellets (∼70%) were not disrupted by the Triton X-100 treatment incorporated into the CFU counts protocol. Other explanations for the low CFU counts (which surpassed a 100-fold decrease for Lp02) include the possibility that some of the ingested legionellae were killed and digested (as shown below) or entered a viable but nonculturable state (43, 55) (not tested).

FIG. 6.

The interaction of L. pneumophila with ciliates is associated with a loss in bacterial viability or culturability. Graphs of two independent feeding experiments, each sampled in triplicate, for strains Lp1-SVir (A) and Lp02 (B), show a decrease in total L. pneumophila CFU per milliliter of Tetrahymena culture. Control curves represent L. pneumophila alone suspended in Osterhout's solution. Means ± standard deviations (n = 3) for each experiment are shown. A group of pellets expelled during feeding experiments with L. pneumophila strain 33216 stained with the BacLight LIVE/DEAD kit, as observed in DIC (C) or confocal fluorescence microscopy to detect live green fluorescent bacteria (shown here in grayscale) (D).

It is important to note that 100% of the pellets examined contained viable L. pneumophila cells as indicated by the BacLight LIVE/DEAD staining kit (Fig. 6C and D). However, the viable/dead legionella ratio varied between pellets, as previously determined with a different vital stain (38). TEM confirmed that some cells of the two virulent L. pneumophila strains Lp02 and Lp1-Svir (TEM of strain JR-32 was not performed) were structurally degraded inside food vacuoles (e.g., Fig. 2C and see Fig. 8C). Nevertheless, regardless of the degree of bacterial killing (or survival) inside food vacuoles, or the mechanism by which legionellae may survive (see below), we concluded that virulent legionellae does not show a net growth in Tetrahymena sp.

FIG. 8.

Electron micrographs of sections labeled with OmpS-specific polyclonal antibodies and a secondary antibody conjugated to 10-nm gold particles, confirming the bacterial origin of the abundant membranous material present in pellets and food vacuoles. (A) Pellet of dotA mutants. (B) Portion of a food vacuole containing some apparently intact dotB mutants and a degraded mutant (arrow). (C) Small pellet of virulent Lp02 cells. Notice the specific labeling of the membrane fragments and the outer membrane of structurally preserved bacterial cells. All specimens were fixed 24 h postinoculation. Size bars represent 0.5 μm.

Formation of legionella-laden pellets depends on a Dot/Icm-mediated survival mechanism.

When ciliates were fed with the dot mutants JV303 (dotB) or JV309 (dotA), few dispersed pellets were expelled as determined by light microscopy, which was similar to the low number of dispersed pellets produced by ciliates feeding on E. coli. The pellets expelled by ciliates feeding on dot mutants (as those shown in Fig. 5B for E. coli) typically depicted abundant membranous material wrapped around a few bacterial cells (Fig. 7A and B). Within intracellular food vacuoles, the mutants often appeared structurally degraded and associated with abundant membranous and vesicular material (Fig. 7C and D). The membrane of food vacuoles containing ingested dot mutants neither had tightly apposed mitochondria, nor did it follow the outline of the contained mutants (Fig. 7C and D).

FIG. 7.

Electron micrographs showing expelled pellets (A and B) or food vacuoles (C and D) produced by Tetrahymena cells feeding on dotA mutant JV309 (A and C) or dotB mutant JV303 (B and D). Pellet samples were fixed at 24 h postinoculation, whereas food vacuole samples were fixed at 4 h postinoculation. The arrows in panels C and D point at structurally degraded bacteria. Notice the abundance of membranous whorls in pellets and membranous and vesicular material in food vacuoles. All size bars represent 0.5 μm.

Because membrane whorls have been traditionally regarded as the remains of digested bacteria (12, 14), it was surmised that dot mutants were being effectively digested by Tetrahymena sp. Using immunogold labeling with an OmpS-specific antibody, the membrane material of dot mutant pellets was clearly immunostained, strongly suggesting that this material consisted of undigested outer membranes from the dot mutants (Fig. 8). The anti-OmpS serum and colloidal gold conjugate also labeled membranous material present in Lp02 pellets (Fig. 8C). The anti-Hsp60 antibody and colloidal gold conjugate labeled the cytoplasm and envelope of intact bacterial cells (not shown) but not the membrane material of the expelled pellets, suggesting that, in contrast to OmpS that is resistant to proteases, the free or membrane-associated chaperonin had been digested.

Genetic complementation of the dot mutants restored their ability to remain morphologically intact inside food vacuoles (not shown), and numerous pellets containing viable bacteria (as determined by their ability to form colonies when spotted on BCYE agar plates) were produced by Tetrahymena sp. feeding on the complemented ΔdotB mutant (Fig. 9) and the complemented dotA mutant (not shown). Collectively, these results suggest that the Dot/Icm system is required for L. pneumophila to resist digestion in the ciliate Tetrahymena sp. and that resistance to digestion is, in turn, a requirement for the formation of numerous legionella-laden pellets.

FIG. 9.

The resistance to digestion and, consequently, production of numerous pellets containing live legionellae is Dot/Icm system dependent. (A to C) Electron micrographs of the pellets produced by ciliates feeding on the ΔdotB mutant JV918 (A), the genetically complemented ΔdotB mutant JV1170 (B), and the mock-complemented ΔdotB mutant JV1133 (C). (D to F) Low-magnification phase-contrast micrographs showing Tetrahymena sp. cells and pellets in a live culture fed with the ΔdotB mutant JV918 (D), the genetically complemented ΔdotB mutant JV1170 (E), and the mock-complemented ΔdotB mutant JV1133 (F). Only ciliates feeding on the genetically complemented ΔdotB mutant often acquired a round shape (arrowhead in panel E) and produced massive aggregative pellets (arrow in panel E) that contained numerous bacterial cells (B). Cytoplasmic inclusions that were not properly infiltrated with epoxy resin appear bubbled and enlarged (A and B). Ciliates feeding on Dot/Icm-defective L. pneumophila looked slender, swam very actively, and produced a few dispersed pellets (D and F). The size bars in panels A to C represent 0.5 μm. The length of the arrow in panel E represents 33 μm and applies to panels D and F.

DISCUSSION

Four different strains of L. pneumophila were unable to show net growth in Tetrahymena sp. at 25 and 30°C, signifying agreement with existing evidence (3, 18, 19, 50, 54) that ciliates do not consistently favor the replication of L. pneumophila. However, the four L. pneumophila strains survived inside food vacuoles during their short intracellular residence and were subsequently expelled by the host Tetrahymena sp. in what we previously referred to as legionella-laden vesicles (38). Because we have now demonstrated that a continuous single membrane does not surround the expelled legionellae and that the vesicle-associated membrane fragments are of bacterial origin, we have chosen to replace the previously used term “vesicle” with the term “pellet.” In contrast to L. pneumophila-infected amoebae that often release free legionellae after lysis (20, 44), Tetrahymena sp. appeared to exclusively release numerous legionella-laden pellets. Therefore, this ciliate could play an important role as an efficient packager of free legionellae in nature, but particularly in man-made aquatic environments (e.g., cooling towers), where the coexistence of ciliates and elevated L. pneumophila numbers is favored. Given the potential ecological and epidemiological importance of legionella-laden pellets (7, 8, 22), and the high efficiency at which Tetrahymena sp. apparently produced such pellets (38), we investigated the pellet production process in detail and determined that it both occurs in the absence of L. pneumophila replication and depends on the presence of a functional Dot/Icm virulence system in the packaged legionellae, which in turn mediates bacterial resistance to digestion by the ciliate.

The packaging of L. pneumophila into pellets appeared to correlate with a fractional loss of bacterial viability or culturability, as collectively suggested by a decrease in CFU, our vital fluorescent staining results, and TEM results that demonstrated in-vacuole degradation of L. pneumophila. While the absence of bacterial replication was experimentally addressed here, determination of the proportion of ingested legionellae actually killed by Tetrahymena sp. remained a difficult task. Further analysis should consider that some of the structurally degraded virulent L. pneumophila cells identified by TEM could have been already dead when ingested and that TEM is unable to distinguish live from dead morphologically intact bacteria. As indicated by the BacLight LIVE/DEAD stain, 5 to 10% of the bacterial inoculum typically used in feeding experiments consisted of dead bacterial cells, a likely source of the membranous material always found in food vacuoles and pellets of virulent legionellae. In addition, the distinction of culturable from nonculturable forms among the viable legionellae (showing a positive vital stain) remains to be determined. However, it is important to emphasize that regardless of how many legionellae lose their viability or culturability, or the mechanism by which this happens, any given pellet always contained viable L. pneumophila cells and could therefore act as a complex infectious particle as discussed below.

The ability of L. pneumophila to survive inside food vacuoles and resist intravacuolar digestion was shown to require a functional Dot/Icm system. This type IV secretion system is key in resisting digestion in amoeba and mammalian macrophages, where effectors translocated to the host cell cytoplasm by the Dot/Icm system mediate the establishment of a specialized membrane-bound compartment (known as the Legionella-containing vacuole) where L. pneumophila replicates (13, 27, 33, 34, 40, 48, 57). It seems logical that such effectors are also translocated by the Dot/Icm system of virulent L. pneumophila into the cytoplasm of Tetrahymena, across the membrane lining food vacuoles. It is tempting to speculate that the juxtaposition of the vacuolar membrane and L. pneumophila cells, as well as the close apposition of mitochondria, could be a host response to (or the result of) translocated L. pneumophila effectors. The fact that the dot mutants did not induce membrane warping and mitochondria apposition indeed suggested that these are Dot/Icm-mediated effects.

The presence of membranous remnants of digested legionellae in food vacuoles (e.g., Fig. 2) or in expelled pellets (Fig. 3 and 8) side by side with morphologically intact undigested bacteria implies that the Dot/Icm-dependent mechanism utilized to resist digestion did not protect all of the bacteria contained in a given food vacuole. Furthermore, the different amounts of bacterial outer membrane remnants present in food vacuoles and their resulting pellets (Fig. 3) suggested that the levels of resistance to digestion could vary between food vacuoles. For instance, a vacuole where most of the contained legionellae were digested would result in a membranous pellet with few apparently intact bacteria (e.g., Fig. 3A, pellet 3). Alternatively, it is possible that ciliates have the ability to sort particulate food into different vacuoles and thus were capable of forming vacuoles enriched in dead legionellae that upon digestion would give rise to membranous pellets. Notwithstanding, our results indicate that the production of pellets containing numerous live legionellae depends on the presence of a functional Dot/Icm system in the ingested L. pneumophila cells. Here we are not suggesting that packaging of L. pneumophila into pellets is a process actively driven by the Dot/Icm system. Instead, to get packaged the ingested legionellae must have a functional Dot/Icm system, which in turn mediates bacterial survival in the ciliate.

A related issue is whether the maintenance of pellet shape (as spheres) is defined by a ciliate-mediated process or requires the presence of bacteria. We conducted preliminary experiments with albumin-coated, 1-μm-diameter, fluorescent beads and observed that these beads trafficked undigested through the ciliate and were expelled as free particles (not in the form of pellets). Therefore, it seems that Tetrahymena sp. alone does not contribute to the maintenance of pellet shape in expelled undigested particles. Although it seems that this process requires the presence of bacteria, the mechanism by which shape is maintained, and the possible role that the Dot/Icm system (if any) may play in it, remains to be determined.

In contrast to amoebae and mammalian macrophages, where the early effects of the Dot/Icm system lead to intracellular replication of L. pneumophila, the Dot/Icm-mediated survival in Tetrahymena food vacuoles did not result in intracellular replication at 30°C. It is not clear why L. pneumophila grows in T. pyriformis at 30 to 35°C and not below 30°C (3, 18, 19), but the fact that Steele and McLennan (54) reported that their T. pyriformis strain did not survive at 35°C (as we observed for T. pyriformis 30202 and Tetrahymena sp.) and that Manasherob et al. (36) indicated that T. pyriformis was lysed at 35°C suggests the possibility that a heat-tolerant culture of altered physiology was used by Fields et al. (19). Because L. pneumophila grows in amoebae at temperatures below 30°C and even at 20°C as indicated by Lee and West (32), we propose that physiological and/or biochemical host factors and not simply temperature are responsible for restricting the intracellular growth of L. pneumophila in Tetrahymena sp. The fact that the ingested L. pneumophila cells did not show any ultrastructural indicators of cell division at any sampling time suggests that a growth restriction mechanism (which the Dot/Icm system was unable to overcome) was in effect very early after ingestion. It is possible that the rapid turnover of food vacuoles alone did not allow L. pneumophila enough time to initiate replication. However, the observations of Smith-Somerville et al. in Tetrahymena vorax (50), where L. pneumophila did not replicate in spite of food vacuoles being retained for several hours, argues against such a possibility. Alternatively, Tetrahymena sp. may fail to respond to some L. pneumophila effectors, or perhaps L. pneumophila is unable to translocate all of its effectors into the ciliate. Tetrahymena sp. may be able to selectively degrade some Dot/Icm effectors or rely on unique trafficking mechanisms (not present in amoebae or mammalian cells) to mobilize its food vacuoles. Finally, it is possible that the ingested legionellae may not receive a “germination” signal (47) to allow differentiation of L. pneumophila into replicative forms that can grow in the ciliate. Tetrahymena sp. may thus constitute a useful experimental model to investigate some of the molecular mechanisms used by host cells to restrict the intracellular growth of L. pneumophila.

In conclusion, we propose that the interaction of L. pneumophila with Tetrahymena species that efficiently package legionellae into pellets may have important epidemiological and ecological implications. One example would be the enhanced survival of pelleted legionellae (7, 8, 22), which is likely to promote a wide distribution of L. pneumophila in aquatic environments and thereby favor contact with humans and the transmission of Legionnaires’ disease. Our observation that only virulent legionellae that carry a functional Dot/Icm system and resist the intravacuolar digestive mechanisms of ciliates are selectively packaged (which may constitute the most infectious legionellae to humans [18]) adds relevance to the potential role that pellets may play as complex infectious units.

Acknowledgments

The technical support of Mary Ann Trevors in the preparation of samples for TEM is gratefully acknowledged, as is the technical assistance of Kim Jefferies and Poornima Gourabathini in conducting some of the experiments reported here. We thank Paul S. Hoffman (currently at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville) for the hyperimmune rabbit sera raised against L. pneumophila OmpS or Hsp60 and for bacterial strains and A. K. C. Brassinga (currently at the University of Virginia) for plasmid pBH6119::htpAB. We thank Howard A. Shuman and Joe Vogel for strains, Ralph Isberg for strains and plasmid pKB9, and Michele Swanson for plasmid pBH6119. We acknowledge Alistair Simpson (Dalhousie University) for his contribution to the analysis of the small ribosomal subunit rRNA gene sequence. Finally, we thank the anonymous reviewers who made excellent suggestions for the improvement of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research through both operating grant ROP-83334 and equipment maintenance grant PRG-80150 (R.A.G.); the Center for the Management, Utilization and Protection of Water Resources, Tennessee Technological University (S.G.B.); and by grant R825352-01 (S.G.B.) from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 February 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, and Water Environment Federation. 1992. Plankton (10200) sample collection, p. 10-14. In A. E. Greenberg, L. S. Clesceri, and A. D. Eaton (ed.), Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 18th ed. American Public Health Association, Washington, DC.

- 2.Arroyo, R., J. Engbring, J. Nguyen, O. Musatovova, O. Lopez, C. Lauriano, and J. F. Alderete. 1995. Characterization of cDNAs encoding adhesin proteins involved in Trichomonas vaginalis cytoadherence. Arch. Med. Res. 26:361-369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbaree, J. M., B. S. Fields, J. C. Feeley, G. W. Gorman, and W. T. Martin. 1986. Isolation of protozoa from water associated with a legionellosis outbreak and demonstration of intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:422-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger, K. H., and R. R. Isberg. 1993. Two distinct defects in intracellular growth complemented by a single genetic locus in Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 7:7-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger, K. H., J. J. Merriam, and R. R. Isberg. 1994. Altered intracellular targeting properties associated with mutations in the Legionella pneumophila dotA gene. Mol. Microbiol. 14:809-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berk, S. G., J. H. Gunderson, A. L. Newsome, A. L. Farone, B. J. Hayes, K. S. Redding, N. Uddin, E. L. Williams, R. A. Johnson, M. Farsian, A. Reid, J. Skimmyhorn, and M. B. Farone. 2006. Occurrence of infected amoebae in cooling towers compared with natural aquatic environments: implications for emerging pathogens. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40:7440-7444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berk, S. G., R. S. Ting, G. W. Turner, and R. J. Ashburn. 1998. Production of respirable vesicles containing live Legionella pneumophila cells by two Acanthamoeba spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:279-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouyer, S., C. Imbert, M.-H. Rodier, and Y. Héchard. 2007. Long-term survival of Legionella pneumophila associated with Acanthamoeba castellanii vesicles. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1341-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandl, M. T., B. M. Rosenthal, A. F. Haxo, and S. G. Berk. 2005. Enhanced survival of Salmonella enterica in vesicles released by a soilborne Tetrahymena species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1562-1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brieland, J. K., J. C. Fantone, D. G. Remick, M. LeGendre, M. McClain, and N. C. Engleberg. 1997. The role of Legionella pneumophila-infected Hartmanella vermiformis as an infectious particle in a murine model of Legionnaires’ disease. Infect. Immun. 65:5330-5333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler, C. A., and P. S. Hoffman. 1990. Characterization of a major 31-kilodalton peptidoglycan-bound protein of Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 172:2401-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman-Andresen, C., and J. R. Nilsson. 1968. On vacuole formation in Tetrahymena pyriformis GL. Compt. Rend. Trav. Lab. Carlsberg. 4:405-432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Felipe, K. S., S. Pampou, O. S. Jovanovic, C. D. Pericone, S. F. Ye, S. Kalachikov, and H. A. Shuman. 2005. Evidence for acquisition of Legionella type IV secretion substrates via interdomain horizontal gene transfer. J. Bacteriol. 187:7716-7726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliot, A. M. (ed.). 1973. Biology of Tetrahymena. Dowden, Hutchinson, & Ross, Inc., Stroudsburg, PA.

- 15.Faulkner, G., and R. A. Garduño. 2002. Ultrastructural analysis of differentiation in Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 184:7025-7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez, R. C., S. H. S. Lee, D. Haldane, R. Sumarah, and K. R. Rozee. 1989. Plaque assay for virulent Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:1961-1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fields, B. S. 1993. Legionella and protozoa: interaction of a pathogen and its natural host, p. 129-136. In J. M. Barbaree, R. F. Breiman, and A. P. Dufour (ed.), Legionella: current status and emerging perspectives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 18.Fields, B. S., J. M. Barbaree, E. B. Shotts, Jr., J. C. Feeley, W. E. Morrill, G. N. Sanden, and M. J. Dykstra. 1986. Comparison of guinea pig and protozoan models for determining virulence of Legionella species. Infect. Immun. 53:553-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fields, B. S., E. B. Shotts, Jr., J. C. Feeley, G. W. Gorman, and W. T. Martin. 1984. Proliferation of Legionella pneumophila as an intracellular parasite of the ciliated protozoan Tetrahymena pyriformis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47:467-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao, L.-Y., and Y. Abu Kwaik. 2000. The mechanism of killing and exiting the protozoan host Acanthamoeba polyphaga by Legionella pneumophila. Environ. Microbiol. 2:79-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao, L.-Y., O. S. Harb, and Y. Abu Kwaik. 1997. Utilization of similar mechanisms by Legionella pneumophila to parasitize two evolutionarily distant hosts, mammalian and protozoan cells. Infect. Immun. 65:4738-4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garduño, E., G. Faulkner, M. A. Ortiz-Jiménez, S. G. Berk, and R. A. Garduño. 2006. Interaction with the ciliate Tetrahymena may predispose Legionella pneumophila to infect human cells, p. 297-300. In N. P. Cianciotto, Y. Abu Kwaik, P. H. Edelstein, B. S. Fields, D. F. Geary, T. G. Harrison, C. Joseph, R. M. Ratcliff, J. E. Stout, and M. S. Swanson (ed.), Legionella: state of the art 30 years after its recognition. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 23.Garduño, R. A., G. Faulkner, M. A. Trevors, N. Vats, and P. S. Hoffman. 1998. Immunolocalization of Hsp60 in Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 180:505-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garduño, R. A., E. Garduño, M. Hiltz, and P. S. Hoffman. 2002. Intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila gives rise to a differentiated form dissimilar to stationary phase forms. Infect. Immun. 70:6273-6283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garduño, R. A., E. Garduño, and P. S. Hoffman. 1998. Surface-associated Hsp60 chaperonin of Legionella pneumophila mediates invasion in a HeLa cell model. Infect. Immun. 66:4602-4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammer, B. K., and M. S. Swanson. 1999. Coordination of Legionella pneumophila virulence with entry into stationary phase by ppGpp. Mol. Microbiol. 33:721-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hilbi, H., G. Segal, and H. A. Shuman. 2001. Icm/Dot-dependent upregulation of phagocytosis by Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 42:603-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman, P. S., C. A. Butler, and F. D. Quinn. 1989. Cloning and temperature-dependent expression in Escherichia coli of a Legionella pneumophila gene coding for a genus-common 60-kilodalton antigen. Infect. Immun. 58:1731-1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffman, P. S., J. H. Seyer, and C. A. Butler. 1992. Molecular characterization of the 28- and 31-kilodalton subunits of the Legionella pneumophila major outer membrane protein. J. Bacteriol. 174:908-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jerome, C. A., and D. H. Lynn. 1996. Identifying and distinguishing sibling species in the Tetrahymena pyriformis complex (Ciliophora, Oligohymenophorea) using PCR/RFLP analysis of nuclear ribosomal DNA. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 43:492-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kado, C. I., and S. T. Liu. 1981. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 145:1365-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, J. V., and A. A. West. 1991. Survival and growth of Legionella species in the environment. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 70(Symp. Suppl.):121S-129S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu, H., and M. Clarke. 2005. Dynamic properties of Legionella-containing phagosomes in Dictyostelium amoebae. Cell. Microbiol. 7:995-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo, Z.-Q., and R. R. Isberg. 2004. Multiple substrates of the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system identified by interbacterial protein transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:841-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mallette, M. F. 1969. Evaluation of growth by physical and chemical means, p. 521-566. In J. R. Norris and D. W. Ribbons (ed.), Methods in microbiology, vol. 1. Academic Press, Inc., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manasherob, R., E. Ben-Dov, A. Zaritsky, and Z. Barak. 1998. Germination, growth, and sporulation of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis in excreted food vacuoles of the protozoan Tetrahymena pyriformis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1750-1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marra, A., S. J. Blander, M. A. Horwitz, and H. A. Shuman. 1992. Identification of a Legionella pneumophila locus required for intracellular multiplication in human macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:9607-9611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNealy, T., A. L. Newsome, R. A. Johnson, and S. G. Berk. 2002. Impact of amoebae, bacteria, and Tetrahymena on Legionella pneumophila multiplication and distribution in an aquatic environment, p. 170-175. In R. Marre, Y. AbuKwaik, C. Bartlett, N. Cianciotto, B. S. Fields, M. Frosch, J. Hacker, and P. C. Lück (ed.), Legionella. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 39.Medlin, L., H. J. Elwood, S. Stickel, and M. L. Sogin. 1988. The characterization of enzymatically amplified eukaryotic 16S-like rRNA-coding regions. Gene 71:491-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagai, H., J. C. Kagan, X. Zhu, R. A. Kahn, and C. R. Roy. 2002. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science 295:679-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osterhout, W. J. V. 1906. On the importance of physiologically balanced solutions for plants. I. Marine plants. Bot. Gaz. 43:127-134. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pascule, A. W., J. C. Feeley, R. J. Gibson, L. G. Cordes, R. L. Meyerowitz, C. M. Patton, G. W. Gorman, C. L. Carmack, J. W. Ezzell, and J. N. Dowling. 1980. Pittsburgh pneumonia agent: direct isolation from human lung tissue. J. Infect. Dis. 141:727-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paszko-Kolva, C. M. Shahamat, and R. R. Colwell. 1992. Long term survival of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 under low-nutrient conditions and associated morphological changes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 102:45-55. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowbotham, T. J. 1983. Isolation of Legionella pneumophila from clinical specimens via amoebae, and the interaction of those and other isolates with amoebae. J. Clin. Pathol. 36:978-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowbotham, T. J. 1986. Current views on the relationships between amoebae, legionellae and man. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 22:678-689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 47.Sauer, J. D., M. A. Bachman, and M. S. Swanson. 2005. The phagosomal transporter A couples threonine acquisition to differentiation and replication of Legionella pneumophila in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:9924-9929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segal, G., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. Legionella pneumophila utilizes the same genes to multiply within Acanthamoeba castellanii and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 67:2117-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sexton, J. A., J. S. Pinkner, R. Roth, J. E. Heuser, S. J. Hultgren, and J. P. Vogel. 2004. The Legionella pneumophila PilT homologue DotB exhibits ATPase activity that is critical for intracellular growth. J. Bacteriol. 186:1658-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith-Somerville, H. E., V. B. Huryn, C. Walker, and A. L. Winters. 1991. Survival of Legionella pneumophila in the cold-water ciliate Tetrahymena vorax. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2742-2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Society of Protozoologists. 1958. A catalogue of laboratory strains of free-living and parasitic protozoa. J. Protozool. 5:1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Solomon, J. M., A. Rupper, J. A. Cardelli, and R. R. Isberg. 2000. Intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila in Dictyostelium discoideum, a system for genetic analysis of host-pathogen interactions. Infect. Immun. 68:2939-2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spriggs, D. R. 1987. Legionella, microbial ecology, and inconspicuous consumption. J. Infect. Dis. 155:1086-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steele, T. W., and A. M. McLennan. 1996. Infection of Tetrahymena pyriformis by Legionella longbeachae and other Legionella species found in potting mixes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1081-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steinert, M., L. Emödy, R. Amann, and J. Hacker. 1997. Resuscitation of viable but nonculturable Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia JR32 by Acanthamoeba castellani. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2047-2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vogel, J., C. Roy, and R. R. Isberg. 1996. Use of salt to isolate Legionella pneumophila mutants unable to replicate in macrophages. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 797:271-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weber, S. S., C. Ragaz, K. Reus, Y. Nyfeler, and H. Hilbi. 2006. Legionella pneumophila exploits PI(4)P to anchor secreted effector proteins to the replicative vacuole. PLoS Pathog. 2:e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]