Abstract

Phosphorylation of histone H1 is intimately related to the cell cycle progression in higher eukaryotes, reaching maximum levels during mitosis. We have previously shown that in the flagellated protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, which does not condense chromatin during mitosis, histone H1 is phosphorylated at a single cyclin-dependent kinase site. By using an antibody that recognizes specifically the phosphorylated T. cruzi histone H1 site, we have now confirmed that T. cruzi histone H1 is also phosphorylated in a cell cycle-dependent manner. Differently from core histones, the bulk of nonphosphorylated histone H1 in G1 and S phases of the cell cycle is concentrated in the central regions of the nucleus, which contains the nucleolus and less densely packed chromatin. When cells pass G2, histone H1 becomes phosphorylated and starts to diffuse. At the onset of mitosis, histone H1 phosphorylation is maximal and found in the entire nuclear space. As permeabilized parasites preferentially lose phosphorylated histone H1, we conclude that this modification promotes its release from less condensed and nucleolar chromatin after G2.

The nucleosome, the basic chromatin unit, is assembled by wrapping DNA around an octamer formed by two copies of histone H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 proteins. A fifth histone, called histone H1, packs the chromatin by contacting internucleosomal DNA and the nucleosome particle (50). Histone H1 is formed by a globular domain flanked by a long unstructured C-terminal portion, comprising almost half of the protein, and by a short and also nonstructured N-terminal domain. The C-terminal domain is enriched in basic amino acids that interact with the negative phosphodiester charges of DNA through S/TPKK motifs (26). The globular portion contacts the core histones and the nucleosomal DNA (3), favoring chromatin compaction, which prevents the access of chromatin remodeling factors and therefore restricts transcription and replication (10). Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments have shown that the chromatin residence time of histone H1 is much shorter than that of other histones, suggesting that histone H1 dynamically associates with the nucleosome particles, contributing to several nuclear processes involving chromatin condensation and decondensation (10, 31, 36). However, when histone H1 is absent, chromatin decondenses (20, 47).

Histone H1 is phosphorylated at the N- and C-terminal domains in a cell cycle-dependent manner (22). The number of phosphorylated residues is small in G1 phase and starts to increase when the cell progresses through S and G2, reaching a maximal level at mitosis (28). Histone H1 phosphorylation is required for DNA replication (24), and protein kinases that activate replication also promote histone H1 phosphorylation (1). Histone H1 phosphorylation affects the heterochromatin structure (23), DNA repair, chromatin remodeling, apoptosis, and cell aging (29, 49). Histone H1 phosphorylation is also involved in chromosome condensation during mitosis. In the absence of histone H1, chromosomes of Xenopus laevis eggs become elongated, and segregation is defective (33). The phosphorylation at the T/SPXK motifs in the C-terminal domain of histone H1 by the mitotic cyclin-dependent kinase (30) is responsible for its dissociation from chromatin (26).

The use of green fluorescence protein (GFP)-histone H1 fusions revealed that phosphorylation increases the dissociation of histone H1 from chromatin (8, 12, 16). However, it is still unclear why histone H1 phosphorylation is maximal at mitosis, when chromosomes are highly condensed. One possibility is that phosphorylation promotes histone H1 dissociation from chromatin, allowing the recruitment of factors involved in chromosome condensation (4, 5). It was proposed that chromatin-bound histone H1 prevents histone H3 phosphorylation, which would capture factors required for chromosome condensation (27).

We have found that in the flagellated protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, the agent of Chagas' disease, histone H1 is also phosphorylated and becomes weakly bound to the chromatin (34). About 20% of histone H1 is phosphorylated in exponentially growing cells. Interestingly, the histone H1 of trypanosomes lacks the globular domain, and their chromatin does not form 30-nm fibers or condense during mitosis (43). In addition, a single cyclin-dependent kinase site is phosphorylated (14). Moreover, it is unusual to find histone H1 phosphorylation associated with mitosis in protozoa. These features, coupled to a peculiar nuclear organization found in trypanosomes (17-19), prompted us to further investigate the distribution of histone H1 and its phosphorylation state in the nucleus of T. cruzi at different stages of the cell cycle. Herein, we generated antibodies that specifically recognize phosphorylated histone H1 and found that phosphorylation is increased after G2. More importantly, we observed an unusual localization of this protein in the nuclear space, which appears to be dependent on its phosphorylation state.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite growth and histone extraction.

T. cruzi epimastigote forms (strain Y) were cultivated in liver infusion tryptose medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 28°C, as previously described (9). Parasites transfected with the plasmid p33H2b-GFP (38) were grown under the same conditions in the presence of 0.5 mg per ml of Geneticin (G418). Histones were extracted as described previously from precipitates of 5 × 108 parasites kept at −70°C (13).

Gel electrophoresis and blots.

Separating gels (80 by 100 by 0.9 mm) composed of 15% acrylamide-bisacrylamide (ratio of 9:1) with an additional layer of 12% acrylamide-bisacrylamide (9:1), both containing 6 M urea, 0.9 M acetic acid, and 0.38% Triton DF16 (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO), were prepared as previously described (13). Histone samples were dissolved in a combination of 2.5 M urea, 0.01% pyronin Y, and 0.9 M acetic acid and then loaded after the second prerun. After electrophoresis (3 h) at 20 mA, the gels were removed from the glass plates and incubated for 40 min in 50 mM acetic acid-0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate and then in 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, buffer containing 2.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate for an additional period of 40 min. The gels were then electroblotted to nitrocellulose membranes using 25 mM N-cyclohexyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid, pH 10, containing 20% methanol at 20 V for 12 h. The membranes were stained with 0.1% Ponceau S in 3% trichloroacetic and destained in distilled water.

Antibodies.

Anti-phosphorylated histone H1 antibodies (anti-H1P) were obtained by immunizing Swiss mice with three intraperitoneal injections, at 3-week intervals, each with 30 μg of a synthetic peptide, NH2-CDAAVPPKKASphosphoPKKA-amide (H1P peptide) coupled to the same amount of mariculture keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Pierce), using the manufacturer's instructions. The first immunization was in complete Freund's adjuvant while the subsequent immunizations were in incomplete Freund's adjuvant. Monospecific antibodies were purified from pooled antisera by chromatography through SulfoLink Coupling Gel (Pierce) containing the H1P peptide, elution with 0.1 M triethylamine (pH 11), neutralization, and further adsorption with SulfoLink gel coupled to the nonphosphorylated peptide NH2-CDAAVPPKKASPKKA-amide (H1T peptide). The peptides were synthesized by Maria Aparecida Juliano (Department of Biophysics, UNIFESP, São Paulo, Brazil) using 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl in an automated, benchtop simultaneous multiple solid-phase peptide synthesizer (PSSM 8 system; Shimadzu, Japan) and purified as described previously (13). Peptides coupling to SulfoLink gel were made as suggested by the manufacturer after peptide reduction with 6 mg per ml of 2-mercaptoethanolamine for 1.5 h at 37°C and desalting. Resins with immobilized peptides were stored in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.02% sodium azide.

Anti-histone H1 (anti-H1T) antibodies were obtained from rabbits or guinea pigs immunized with T. cruzi recombinant histone H1 produced in Escherichia coli as previously described (34). Rabbit antibodies were further purified by adsorbing the protein A-purified antibodies on SulfoLink gel coupled to H1T peptide. After column wash, bound antibodies were eluted with 0.1 M triethylamine, (pH 11), neutralization, and further adsorption with SulfoLink gel coupled to the H1P peptide. Guinea pig antisera were purified by chromatography using protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). The preparation of rabbit antibodies to histone H4 acetylated at lysine 4 was described previously (13). Rabbit antibodies to T. cruzi amastigotes were provided by Mauro Javier Cortez Véliz (UNIFESP). Monoclonal antibody 2F6 was derived from BALB/c mice immunized with a T. cruzi cytoskeleton-enriched fraction. Spleen cells were fused to a myeloma P3U.1 cell line. Hybridoma and cloned cells were screened by immunofluorescence against T. cruzi epimastigotes (see below). Culture hybridoma supernatants were used in the experiments.

Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence labeling.

Nitrocellulose membranes were treated for 1 h with 7% nonfat dry milk in PBS and then incubated with the indicated antibodies at room temperature. After 2 h, the membranes were washed with PBS, and bound antibodies were detected with the respective anti-immunoglobulin (Ig) coupled to peroxidase (Santa Cruz) and chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce).

Indirect immunofluorescence experiments were performed by attaching 2 × 105 prewashed cells to glass slides, and fixation was carried out with 0.5 to 4% p-formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min. The slides were washed three times with PBS and treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. The slides were then incubated with the indicated antibodies diluted in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin. After 1 h, the slides were washed three times, and bound antibodies were detected with the indicated fluorescent conjugates in the presence of 0.01 mM 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) was used for mounting, and the slides were visualized with a 100× oil immersion objective (1.3 numerical aperture) in a Nikon E600 microscope coupled to a Nikon DXM1200F camera. Images were processed for color using Adobe Photoshop. When indicated, the images were observed in a Zeiss Laser Scanning Microscope 810 confocal microscope using a 100× immersion objective (1.3 numerical aperture), and images were processed using Lasersharp software.

Fluorescence quantification was done using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Nuclei were individually delimited, and the mean labeling intensity under subsaturating conditions was previously determined using a limiting amount of anti-H1T or anti-H1P antibodies. The pixels per area were normalized to absolute values for each antibody to compare the variations. A Student t test and one-way analysis of variance followed by a Bonferoni posttest were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 3.0, software.

RESULTS

Generation of antibodies specific for phosphorylated histone H1.

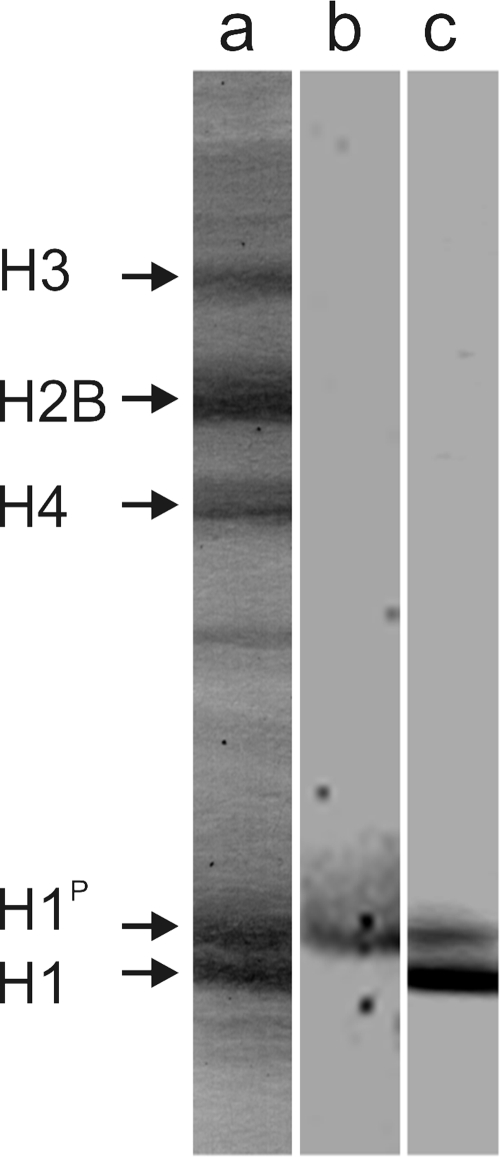

Several studies have shown that histone H1 phosphorylation increases as cells progress in the cell cycle, reaching maximal levels during mitosis, when dephosphorylation takes place (22, 37). To determine the moment in the T. cruzi cell cycle at which histone H1 is phosphorylated and to localize its phosphorylated form in the nucleus, specific antibodies were generated. For this, mice were immunized with a synthetic 15-mer peptide corresponding to the N terminus of T. cruzi histone H1 containing a phosphate group in the serine previously identified as the unique phosphorylation site (14). Specific anti-phosphorylated histone H1 antibodies (H1P) were purified after elution from a column containing the above peptide, followed by adsorption through a similar column containing the nonphosphorylated histone H1 peptide. As seen in Fig. 1, these antibodies recognize only the slow-migrating band in acid-urea-Triton electrophoresis that was previously shown to correspond to the phosphorylated histone H1 (34). Antibodies to the recombinant histone H1 recognized both forms of protein, although with higher affinity to the nonphosphorylated protein.

FIG. 1.

Antibodies specifically recognize phosphorylated histone H1. Total T. cruzi histones were extracted and subjected to electrophoresis in Triton acid urea gels, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and stained with Ponceau S (lane a). The membrane was then incubated with mouse antibodies raised against the histone H1 phosphorylated peptide (lane b) or with antibodies raised in rabbits against recombinant T. cruzi histone H1 (lane c). Both antibodies were purified as described in Materials and Methods. Bound antibodies were detected by chemiluminescence assays using specific anti-IgG peroxidase conjugates. The position of each histone is indicated on the left.

Anti-H1P labels predominantly nuclei of cells in G2 and M phases.

Exponentially growing cultures of T. cruzi presented heterogeneous nuclear labeling intensities when anti-H1P was used, suggesting that labeling varies according to the cell cycle. T. cruzi cell cycle stages can be recognized based on the number of flagella, nuclei, and kinetoplasts (the mitochondrial DNA of trypanosomes) (17). The G2 cells correspond to those with one kinetoplast, one nucleus, and a short additional flagellum (see black arrows in phase-contrast images). Mitotic cells contain one nucleus, two flagella, and two kinetoplasts, and postmitotic cells have two nuclei. Figure S1 in the supplemental material shows that cells in G2 and mitosis and those that had just finished mitosis were intensely labeled. In contrast, cells with one flagellum, which correspond to cells in G1 or early S, were weakly labeled. The specificity of these reactions was ensured by the fact that 1 μg per ml of H1P peptide inhibited the fluorescence of anti-H1P while more than 100 μg of the nonphosphorylated peptide was required to prevent labeling (not shown).

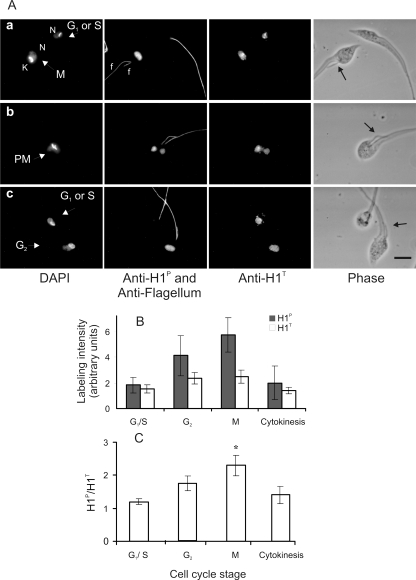

To verify whether the weak labeling was due to a lower expression of histone H1 or to a reduced level of phosphorylation, the cells were simultaneously labeled with anti-H1T, an antibody prepared against the recombinant H1 that recognizes both forms of histone H1, although with higher affinity for the nonphosphorylated histone H1. To better distinguish cells in G2 (two flagella) from G1/S (one flagellum), the preparations were also stained with antibodies against the flagellum (monoclonal antibody 2F6). As seen in Fig. 2, similar labeling intensity for anti-H1T was observed in G1/S, G2, and M cells. Cells with small nuclei, shown in panels a and c, were practically undetected by anti-H1P but were labeled by anti-H1T. Each of these cells had a single flagellum and was probably at G1 phase. It should be mentioned that histone H1 synthesis occurs throughout the entire T. cruzi cell cycle, with some significant increase in S phase (40).

FIG. 2.

Histone H1 phosphorylation is more intense in cells approaching mitosis. (A) Exponentially growing epimastigotes were stained with DAPI and with mouse anti-H1P and the monoclonal antibody 2F6 (simultaneously) or rabbit anti-H1T. Bound antibodies were detected with anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 488 and anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 555. The localization of each flagellum is indicated by f. The cell cycle stage is indicated in the DAPI images as G1 or S, M, and PM (postmitosis). N, nucleus; K, kinetoplast. Black arrows in phase-contrast images indicate the new flagellum. Bar, 5 μm. (B) The relative intensity of anti-H1P (black bars) and anti-H1T (white bars) in the nucleus area delimited by DAPI staining was quantified using ImageJ. In the graph, values are means ± standard deviations of the labeling intensity obtained for each antibody (n = 194). The cell cycle stage was defined based as follows: one flagellum, one nucleus, and one kinetoplast as G1/S; two flagella, one nucleus, and one kinetoplast as G2, two flagella, one nucleus, and two kinetoplasts as M, and two flagella, two nuclei, and two kinetoplasts as cytokinesis. The observed values did not allow us to compare the absolute labeling of H1P with H1T. (C) Ratio of anti-H1P and anti-H1T labeling through the cell cycle progression. The mean values were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance and a Bonferoni posttest with a P value of <0.001. Differences statistically significant were obtained between the G1/S and M groups (*).

The intensity of labeling per area for each antibody was independently quantified for a total 194 nuclei at different cell cycle stages. The labeling intensity was measured under subsaturating conditions for each antibody, and the values are expressed as arbitrary units. As shown in Fig. 2B the labeling increased more for anti-H1P than for anti-H1T in G2 and M cells. The ratio of phosphorylated versus total histone H1 was higher in mitosis (Fig. 2C), confirming that phosphorylation predominates in mitotic cells.

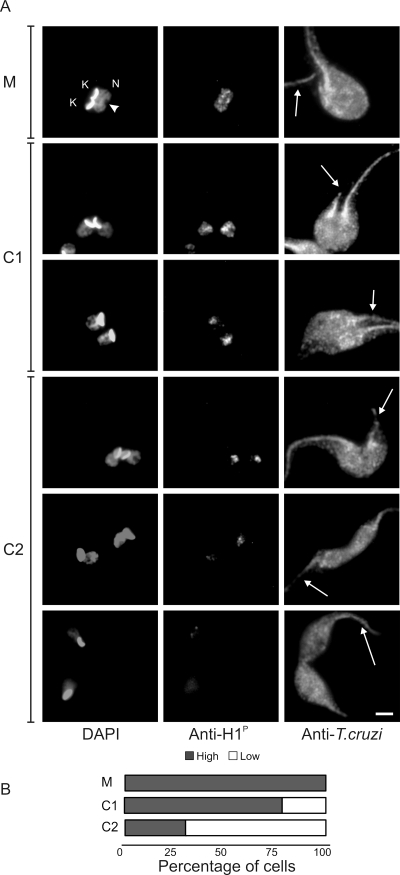

Histone H1 is dephosphorylated at cytokinesis.

The quantification analysis also suggested that histone H1 is dephosphorylated after mitosis. To better visualize and determine the moment of histone H1 dephosphorylation, an antibody that reveals the cell shape was used for counterstaining. In cells that have just undergone mitosis, nuclear labeling with anti-H1P remained high (Fig. 3A). However, it progressively decreased as two cell bodies were formed (Fig. 3B). This result indicates that histone H1 dephosphorylation starts after mitosis and progresses until the completion of cytokinesis. Interestingly, the localization of both forms of histone H1 did not match the DAPI staining. Histone H1 was found predominantly in chromatin-poor regions, which could be better observed with the progression of cytokinesis, when histone H1 staining becomes constricted to the central region of the nucleus.

FIG. 3.

Anti-H1P labeling decreases after mitosis. (A) Exponentially growing epimastigote cultures were processed for immunofluorescence assays with anti-H1P and with an anti-T. cruzi antiserum, which labels the entire parasite. Parasites in cytokinesis (C1 and C2) were visualized as cells with two flagella, two nuclei, and two kinetoplasts; cells with the two flagella in the same direction are identified as C1, and those with the flagella in the opposite directions are C2, which corresponds to a more advanced stage. Arrowhead, mitotic nucleus; arrow, a new flagellum; N, nucleus; K, kinetoplast. Bar, 2 μm. (B) Labeling intensity distribution for anti-H1P in mitosis and cytokinesis stages (C1 and C2). Highly labeled cells correspond to the mean labeling intensity found in mitotic cells, while low-intensity labeling corresponds to the labeling found in G1/S cells (Fig. 4). The cells in mitosis (M; n = 188), C1 (n = 242), and C2 (n = 84) stages were scored for high (dark bars) and low fluorescence (white bars) in three independent experiments. Standard deviations were as follows, M, 0; C1, 0.9; and C2, 5.4.

Histone H1 is concentrated in the nucleus interior in G1/S cells and spreads in G2 and mitosis.

As shown above, histone H1 in the late stages of cytokinesis and in G1 cells appeared centrally located in the parasite nucleus, a region known to contain the nucleolus (19). To explore this issue, anti-histone H1 antibodies were used to label T. cruzi cells expressing only a short portion of the N terminus of histone H2B in fusion with GFP, previously described to be targeted to the nucleolus (18, 38). As shown in Fig. 4, H1T was enriched in the central nuclear region not completely coincident with the nucleolus in G1/S cells, with a weaker labeling distributed throughout the nuclear space (panel a). In G2 cells, as defined by the presence of the second flagellum, H1T labeling was still observed in the nucleolar region. It is also apparent that the nucleolus decreases in size in G2 cells (panel b). In mitotic cells the H2B-GFP fusion dispersed, suggesting that the nucleolus disassembles. In this case, histone H1T, which also labels the phosphorylated histone H1, was found occupying the entire nuclear space (panel c). Figure 4d and f show the double labeling of H2B-GFP and anti-H1P. In G1/S cells, phosphorylated histone H1, detected upon high exposure, was visible only in the nucleolar region (panel d). In contrast to H1T, the labeling of H1P increased and spread within the entire nuclear space in G2 (panel e). Fig. 4f shows a cell in early cytokinesis, strongly labeled by H1P still in a dispersed pattern, with the nucleolus starting to be reassembled. These images suggest that most of histone H1 is concentrated in the nuclear interior and that when it becomes phosphorylated from G2 to M, it spreads to the nuclear space.

FIG. 4.

Histone H1 is preferentially found associated with the nucleolus in G1/S phase and spreads in G2 and mitosis when phosphorylated. Exponentially growing epimastigotes expressing the nucleolus tag (H2B-GFP) were processed for DAPI staining and for immunofluorescence labeling using rabbit anti-H1T (a to c) or mouse anti-H1P (d to f), followed by an anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 555. Merged images show the DAPI in blue, GFP in green, and anti-H1P or anti-H1T in red. Black arrows point to the new flagellum. Bars are 1 μm in the fluorescence images and 3 μm in phase-contrast images. N, nucleus; K, kinetoplast.

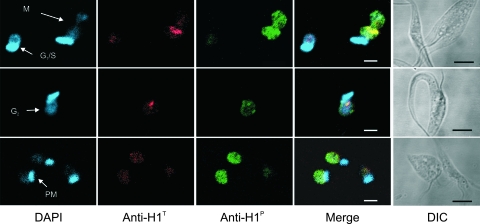

To confirm whether phosphorylation of histone H1 indeed changes its localization, confocal microscopy analysis was performed. As shown in Fig. 5, G 1/S cells show a high degree of colocalization for the H1P and H1T labeling in the central region of the nucleus. In contrast, cells in G2, which still have most of H1T associated with the nucleolus, have a significant dispersion of H1P. The difference between H1P and H1T labeling is observed in a mitotic cell. On early cytokinesis both markers disperse.

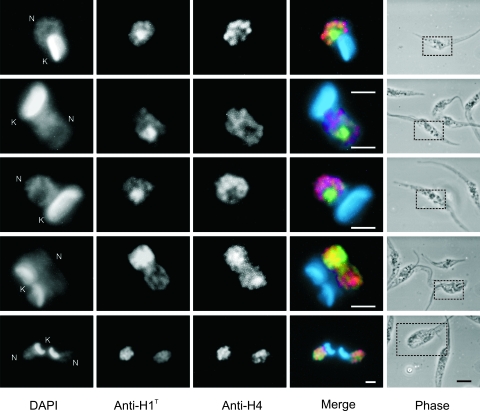

FIG. 5.

Phosphorylated histone H1 is homogenously distributed in the mitotic nucleus. Exponentially growing epimastigote cultures processed for DAPI (blue), anti-H1P (green), and anti-H1T (red) staining were visualized by confocal microscopy. The three images show single focal planes containing cells in G1/S, G2, and postmitosis (PM) stages. The bars are 2 μm in the fluorescence images and 5 μm in the differential interference contrast (DIC) images.

Histone H1 does not colocalize with bulk chromatin.

In high-magnification images it was possible to observe that the DAPI staining was different from the labeling of both forms of histone H1, suggesting that the majority of histone H1 is not associated with most of the chromatin. To verify whether histone H1 is enriched in less dense chromatin areas and to rule out the possibility that anti-histone H1 antibodies were just excluded from dense regions, the cells were stained concomitantly with anti-H1T and with an antibody specific for the T. cruzi histone H4 acetylated at lysine 4. This latter modification is found in the majority of the histone H4 of the parasite (13). As seen in Fig. 6, the localization of histone H1 differs significantly from the bulk of histone H4. In G1/S cells or in G2 cells, even the more dispersed histone H1 did not entirely colocalize with histone H4. In mitotic cells when histone H1 was found dispersed, histone H4 was concentrated in the nuclear interior. Only in postmitotic cells was some degree of colocalization noticed. This result confirms that most of histone H1 is not associated with the bulk of T. cruzi chromatin.

FIG. 6.

Histone H1 does not colocalize with bulk histones in the nucleus of T. cruzi. Exponentially growing epimastigote cultures were processed for DAPI staining and immunofluorescence with guinea pig anti-H1T and rabbit anti-histone acetyl-H4K4. Bound antibodies were detected using Alexa 488 for anti-H1T or fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated to anti-guinea pig IgG antibodies and Alexa 555 for the anti-rabbit IgG. Merged images show DAPI in blue, anti-H1T in green, and anti-histone H4 in red. Bar, 2 μm. The areas delimited by dotted lines in phase-contrast images correspond to the regions shown in the fluorescence images.

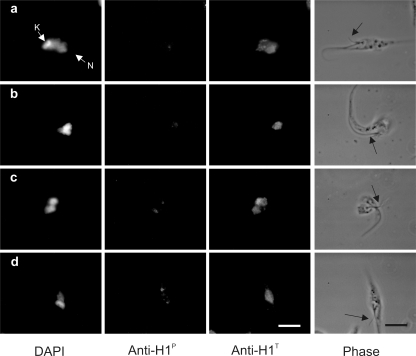

Phosphorylated histone H1 is not retained within permeable T. cruzi nuclei.

We reported earlier that phosphorylated histone H1 can be released from the chromatin with lower salt concentrations than the nonphosphorylated form of the protein (34). As the phosphorylated form of histone H1 seems to spread considerably after G2, we examined H1P labeling on cells permeabilized with detergent prior to fixation. As shown in Fig. 7, the kinetoplast and the nucleus spread, and flagella became devoid of membranes after detergent treatment. By observing cells with two flagella, which were in G2, we found that in contrast to what was found in nonpermeabilized cells, these detergent-treated cells showed much smaller nuclear labeling for anti-H1P than the labeling shown in Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material, which was visualized at similar exposures and antibody dilutions. Nevertheless, the cells still exhibited a strong anti-H1T labeling associated with the nucleus stained by DAPI, indicating that histone H1 is bound either to the dense nucleolar region or to the chromatin while the phosphorylated form is weakly associated with chromatin.

FIG. 7.

Phosphorylated histone H1 is weakly bound to chromatin. Exponentially growing epimastigote cultures were attached to glass slides and pretreated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 min before fixation with 4% p-formaldehyde in PBS. The cells were then stained for DAPI, and immunolabeled with mouse anti-H1P and rabbit anti-H1T. All images contain parasites in G2 or M as evidenced by the presence of two flagella (black arrow indicates the new flagellum). N, nucleus; K, kinetoplast. Bar, 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

In this work we investigated the distribution and the level of histone H1 phosphorylation in the nucleus of T. cruzi at different stages of the cell cycle. By using antibodies generated against its single phosphorylation site, we demonstrated that histone H1 is highly phosphorylated after G2, reaching maximal levels at mitosis, as most eukaryotic cells do. However, this observation is unexpected because T. cruzi has a closed division and does not condense the chromatin in 30-nm fibers due to the absence of the globular domain of histone H1 (48). Therefore, mitotic T. cruzi histone H1 phosphorylation is not related to chromosome condensation. Instead, our results showing the unique histone H1 localization, which is associated with less DAPI-stained chromatin areas, including the nucleolus, and the dispersion of H1 after phosphorylation indicate that this modification mainly modulates the dissociation of histone H1 from the less condensed chromatin in T. cruzi.

Limited histone H1 phosphorylation was observed in 91% of G1/S phase cells. Perhaps the 9% strongly labeled cells could be in the replicative stage, as it was not possible to distinguish morphologically G1 from S phase cells. This would require labeling with bromodeoxyuridine, which was not possible in the present study. Acid treatment, required to detect this labeling, totally inhibited the binding of anti-H1P. Nevertheless, these numbers are compatible with the fact that in exponentially growing cells a small percentage (<10%) of parasites are in S phase, which is much shorter than G1 (17), and could suggest that phosphorylation starts in the S phase. As the bulk of histone H1 synthesis occurs in S phase and an increase in the nuclear size was observable, the phosphorylation in S phase could not be confirmed. It is also possible that newly added histone H1 was in the phosphorylated state. In contrast, 91% and 100% of the cells in G2 and M, respectively, were intensely labeled with anti-H1P compared to anti-H1T, pointing out that histone H1 is clearly phosphorylated in these phases. It is unlikely that these differences are due to the differential expression of the three T. cruzi histone H1 isoforms, as they contain identical N termini and should be recognized similarly by both antibodies.

We have previously found that the cyclin-dependent kinase of T. cruzi (TzCRK3) can phosphorylate the T. cruzi histone H1 in vitro (14). As this enzyme is enriched in the G2 phase (41), the present findings reinforce the notion that it could be involved in histone H1 phosphorylation. We have also observed earlier that okadaic acid prevented histone H1 dephosphorylation and blocked the cell cycle cytokinesis (14). The present data showing that histone H1 dephosphorylation occurs during cytokinesis imply that such an okadaic-sensitive phosphatase, involved in cell cycle control, must be also involved in this dephosphorylation.

The role of phosphorylation is still controversial, mainly because there are several phosphorylation sites in most eukaryotic H1 histones. Early work suggested that histone H1 could be involved in chromosome condensation (6, 7). Other investigators proposed that it could generate chromatin decondensation by destabilizing the chromatin structure (39). Phosphorylation clearly weakens the interaction of histone H1 with DNA, allowing binding of factors involved in transcription, replication, and DNA repair (1, 12, 51). Similarly, release of histone H1 could promote the binding of condensing factors (11, 23).

In T. cruzi, histone H1 phosphorylation occurs at a single site and was shown to increase the susceptibility to micrococcus nuclease (34). Here, we provided additional evidence that the phosphorylated protein is less associated with insoluble chromatin. The fact that T. cruzi histone H1 distribution is not homogenous and differs from the distribution of other histones could suggest that, as a more motile histone (31), it could just be excluded from DNA-rich regions. However, its distribution is not always coincident with the DNA-poor regions, recognized by regions less labeled by DAPI and by anti-histone H4. Rather, it is partially associated with the nucleolus, suggesting that it is enriched in specific nuclear regions. Also, that H1 disperses upon phosphorylation and that nonphosphorylated histone H1 does not diffuse after cell permeabilization support the idea that it has a specific localization.

Based on the present results, it could also be speculated that T. cruzi histone H1 would have a role in nucleolus transcription and/or ribosome biogenesis. The phosphorylation could modulate nucleolus disassembly, seen as cells progress from G2 to mitosis. Interestingly, there are recent reports describing the specific localization of some histone H1 variants in the nucleolus of other organisms. For example, the histone H1FO is found dispersed through the entire nuclear space excluding the nucleolus in somatic cells, accumulating in heterochromatin-rich areas, while in oocytes it is located preferentially in the nucleolus and perinucleolar sites (2). Histone H1x, a subtype located in chromatin regions not affected by micrococcus nuclease (25), is also located in the nucleolus region at G1 phase (44). In plants a histone H1 variant called p35 is also enriched in the nucleolus (46). In yeast, it represses recombination at the ribosomal DNA locus (32).

The finding that T. cruzi histone H1 is present in less condensed chromatin could suggest that it is associated with the transcription machinery, mainly the domain located near the nucleolus and formed by transcription of spliced leader RNA (15), which is used as a trans-splicing donor for all mRNAs in trypanosomes (21, 45). However, histone H1 does not colocalize with RNA polymerase II in T. cruzi (data not shown), excluding this possibility. Recently, the superexpression of histone H1 in Leishmania major, another trypanosomatid, was shown to affect cell cycle progression and cellular differentiation (42), in agreement with its role in promoting chromatin condensation (35). The results presented herein raise a novel role for histone H1. It should be related to chromatin organization in the nucleolus, modulated in the cell cycle through phosphorylation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Beatriz A. Castilho and Rogerio Amino for reading the manuscript and for helpful discussions and suggestions. We also thank Bettina Malnic for the use of the confocal microscope and Maria Aparecida Juliano for the synthesis of peptides.

This work was supported by grants from FAPESP and CNPq (Brazil). J.P.C.C. and L.M.G. were FAPESP (Brazil) fellows.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 February 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexandrow, M. G., and J. L. Hamlin. 2005. Chromatin decondensation in S-phase involves recruitment of Cdk2 by Cdc45 and histone H1 phosphorylation. J. Cell Biol. 168875-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker, M., A. Becker, F. Miyara, Z. Han, M. Kihara, D. T. Brown, G. L. Hager, K. Latham, E. Y. Adashi, and T. Misteli. 2005. Differential in vivo binding dynamics of somatic and oocyte-specific linker histones in oocytes and during ES cell nuclear transfer. Mol. Biol. Cell 163887-3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belikov, S., and V. Karpov. 1998. Linker histones: paradigm lost but questions remain. FEBS Lett. 441161-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleher, R., and R. Martin. 1999. Nucleo-cytoplasmic translocation of histone H1 during the HeLa cell cycle. Chromosoma 108308-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boggs, B. A., C. D. Allis, and A. C. Chinault. 2000. Immunofluorescent studies of human chromosomes with antibodies against phosphorylated H1 histone. Chromosoma 108485-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradbury, E. M. 1992. Reversible histone modifications and the chromosome cell cycle. BioEssays 149-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradbury, E. M., R. J. Inglis, and H. R. Matthews. 1974. Control of cell division by very lysine rich histone (F1) phosphorylation. Nature 247257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bustin, M., F. Catez, and J. H. Lim. 2005. The Dynamics of histone H1 function in chromatin. Mol. Cell 17617-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camargo, E. P. 1964. Growth and differentiation in Trypanosoma cruzi: Origin of metacyclic trypomastigotes in liquid media. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 693-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catez, F., T. Ueda, and M. Bustin. 2006. Determinants of histone H1 mobility and chromatin binding in living cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13305-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chadee, D. N., W. R. Taylor, R. A. Hurta, C. D. Allis, J. A. Wright, and J. R. Davie. 1995. Increased phosphorylation of histone H1 in mouse fibroblasts transformed with oncogenes or constitutively active mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 27020098-20105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Contreras, A., T. K. Hale, D. L. Stenoien, J. M. Rosen, M. A. Mancini, and R. E. Herrera. 2003. The dynamic mobility of histone H1 is regulated by cyclin/CDK phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 238626-8636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.da Cunha, J. P., E. S. Nakayasu, I. C. de Almeida, and S. Schenkman. 2006. Post-translational modifications of Trypanosoma cruzi histone H4. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 150268-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.da Cunha, J. P. C., E. S. Nakayasu, M. C. Elias, D. C. Pimenta, M. T. Tellez-Inon, F. Rojas, M. Manuel, I. C. Almeida, and S. Schenkman. 2005. Trypanosoma cruzi histone H1 is phosphorylated in a typical cyclin dependent kinase site accordingly to the cell cycle. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 14075-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dossin, F. M., and S. Schenkman. 2005. Actively transcribing RNA polymerase II concentrates on spliced leader genes in the nucleus of Trypanosoma cruzi. Eukaryot. Cell 4960-970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dou, Y., J. Bowen, Y. Liu, and M. A. Gorovsky. 2002. Phosphorylation and an ATP-dependent process increase the dynamic exchange of H1 in chromatin. J. Cell Biol. 1581161-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elias, M. C., J. P. da Cunha, F. P. de Faria, R. A. Mortara, E. Freymuller, and S. Schenkman. 2007. Morphological events during the Trypanosoma cruzi cell cycle. Protist 158147-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elias, M. C., M. Faria, R. A. Mortara, M. C. M. Motta, W. de Souza, M. Thiry, and S. Schenkman. 2002. Chromosome localization changes in the Trypanosoma cruzi nucleus. Eukaryot. Cell 1944-953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elias, M. C., R. Marques-Porto, E. Freymuller, and S. Schenkman. 2001. Transcription rate modulation through the Trypanosoma cruzi life cycle occurs in parallel with changes in nuclear organisation. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 11279-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan, Y., T. Nikitina, J. Zhao, T. J. Fleury, R. Bhattacharyya, E. E. Bouhassira, A. Stein, C. L. Woodcock, and A. I. Skoultchi. 2005. Histone H1 depletion in mammals alters global chromatin structure but causes specific changes in gene regulation. Cell 1231199-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gull, K. 2001. The biology of kinetoplastid parasites: insights and challenges from genomics and post-genomics. Int. J. Parasitol. 31443-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurley, L. R., J. G. Valdez, and J. S. Buchanan. 1995. Characterization of the mitotic specific phosphorylation site of histone H1. Absence of a consensus sequence for the p34cdc2/cyclin B kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 27027653-27660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hale, T. K., A. Contreras, A. J. Morrison, and R. E. Herrera. 2006. Phosphorylation of the linker histone H1 by CDK regulates its binding to HP1α. Mol. Cell 22693-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halmer, L., and C. Gruss. 1996. Effects of cell cycle dependent histone H1 phosphorylation on chromatin structure and chromatin replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 241420-1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Happel, N., E. Schulze, and D. Doenecke. 2005. Characterisation of human histone H1x. Biol. Chem. 386541-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendzel, M. J., M. A. Lever, E. Crawford, and J. P. Th'ng. 2004. The C-terminal domain is the primary determinant of histone H1 binding to chromatin in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 27920028-20034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirano, T. 2000. Chromosome cohesion, condensation, and separation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69115-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hohmann, P. 1983. Phosphorylation of H1 histones. Mol. Cell Biochem. 5781-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konishi, A., S. Shimizu, J. Hirota, T. Takao, Y. Fan, Y. Matsuoka, L. Zhang, Y. Yoneda, Y. Fujii, A. I. Skoultchi, and Y. Tsujimoto. 2003. Involvement of histone H1.2 in apoptosis induced by DNA double-strand breaks. Cell 114673-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langan, T. A., J. Gautier, M. Lohka, R. Hollingsworth, S. Moreno, P. Nurse, J. Maller, and R. A. Sclafani. 1989. Mammalian growth-associated H1 histone kinase: a homolog of cdc2+/CDC28 protein kinases controlling mitotic entry in yeast and frog cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 93860-3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lever, M. A., J. P. H. Th'Ng, X. J. Sun, and M. J. Hendzel. 2000. Rapid exchange of histone H1.1 on chromatin in living human cells. Nature 408873-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, C., J. E. Mueller, M. Elfline, and M. Bryk. 2008. Linker histone H1 represses recombination at the ribosomal DNA locus in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 67906-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maresca, T. J., B. S. Freedman, and R. Heald. 2005. Histone H1 is essential for mitotic chromosome architecture and segregation in Xenopus laevis egg extracts. J. Cell Biol. 169859-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marques Porto, R., R. Amino, M. C. Elias, M. Faria, and S. Schenkman. 2002. Histone H1 is phosphorylated in non-replicating and infective forms of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 119265-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masina, S., H. Zangger, D. Rivier, and N. Fasel. 2007. Histone H1 regulates chromatin condensation in Leishmania parasites. Exp. Parasitol. 11683-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Misteli, T., A. Gunjan, R. Hock, M. Bustin, and D. T. Brown. 2000. Dynamic binding of histone H1 to chromatin in living cells. Nature 408877-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nurse, P. 1990. Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature 344503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramirez, M. I., L. M. Yamauchi, L. H. de Freitas, H. Uemura, and S. Schenkman. 2000. The use of the green fluorescent protein to monitor and improve transfection in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 111235-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roth, S. Y., and C. D. Allis. 1992. Chromatin condensation. Does H1 dephosphorylation play a role? Trends Biochem. Sci. 1793-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabaj, V., J. Diaz, G. C. Toro, and N. Galanti. 1997. Histone synthesis in Trypanosoma cruzi. Exp. Cell Res. 236446-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santori, M. I., S. Laria, E. B. Gomez, I. Espinosa, N. Galanti, and M. T. Tellez-Inon. 2002. Evidence for CRK3 participation in the cell division cycle of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 121225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smirlis, D., S. N. Bisti, E. Xingi, G. Konidou, M. Thiakaki, and K. P. Soteriadou. 2006. Leishmania histone H1 overexpression delays parasite cell-cycle progression, parasite differentiation and reduces Leishmania infectivity in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 601457-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solari, A. J. 1995. Mitosis and genome partition in trypanosomes. Biocell 1965-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoldt, S., D. Wenzel, E. Schulze, D. Doenecke, and N. Happel. 2007. G1 phase-dependent nucleolar accumulation of human histone H1x. Biol. Cell 99541-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sutton, R. E., and J. C. Boothroyd. 1986. Evidence for trans splicing in trypanosomes. Cell 47527-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka, I., Y. Akahori, K. Gomi, T. Suzuki, and K. Ueda. 1999. A novel histone variant localized in nucleoli of higher plant cells. Chromosoma 108190-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thoma, F., T. Koller, and A. Klug. 1979. Involvement of histone H1 in the organization of the nucleosome and of the salt-dependent superstructures of chromatin. J. Cell Biol. 83403-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toro, G. C., and N. Galanti. 1988. H1 histone and histone variants in Trypanosoma cruzi. Exp. Cell Res. 17416-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolffe, A. P., and J. C. Hansen. 2001. Nuclear visions: functional flexibility from structural instability. Cell 104631-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodcock, C. L., A. I. Skoultchi, and Y. Fan. 2006. Role of linker histone in chromatin structure and function: H1 stoichiometry and nucleosome repeat length. Chromosome Res. 1417-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yellajoshyula, D., and D. T. Brown. 2006. Global modulation of chromatin dynamics mediated by dephosphorylation of linker histone H1 is necessary for erythroid differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10318568-18573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.