Abstract

The prevalence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-hepatitis E virus (anti-HEV) antibodies was studied with a representative sample of 1,249 healthy children aged between 6 and 15 years. IgG anti-HEV antibodies were detected in 57 (4.6%) of the 1,249 samples analyzed, suggesting that some children are exposed to HEV in early childhood.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection is endemic in parts of the developing world, and large outbreaks occur in areas with poor water sanitation. It is rare in developed countries, although increasing numbers of autochthonous cases have been reported in recent years (3, 11, 13, 16, 19).

The objective of this study was to analyze the seroprevalence of HEV infection in a representative sample of healthy Spanish children and determine the sociodemographic and medical factors associated with HEV infection.

A sample of schoolchildren aged 6 to 15 years was obtained from 30 randomly selected schools in Catalonia, a region in the northeast of Spain, between January and May 2001. The sample size, calculated taking into account a prevalence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-HEV antibodies of 3% in young adults (4), an α error of 5%, and a precision of ±0.0087, was 1,477. Informed consent to obtain blood samples and study variables was obtained from parents.

The sociodemographic variables assessed were age, sex, place of birth, habitat (urban or rural), and social class, classifying children into three groups according to the parent's profession and the English classification of social classes (14).

The medical variables were history of accidents causing bleeding wounds, surgical interventions, dental extractions, and history of acute viral hepatitis.

IgG anti-HEV antibodies were detected using a commercial immunoenzymatic method (Bioelisa HEV IgG; BIOKIT, Barcelona, Spain). Samples with IgG anti-HEV antibodies were tested for IgM anti-HEV antibodies by an immunoenzymatic method (Bioelisa HEV IgM; BIOKIT, Barcelona, Spain). IgG anti-hepatitis A virus (anti-HAV) antibodies and anti-surface hepatitis B virus antigen were detected by automatic chemiluminescent immunoassay methods (Vitros ECi; Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, High Wycombe, United Kingdom).

The prevalences of anti-HEV antibodies and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were determined by the binomial exact method for different socioeconomic groups. The prevalences of antibodies in different groups were compared using the chi-square test. Statistical significance was established at P values of <0.05.

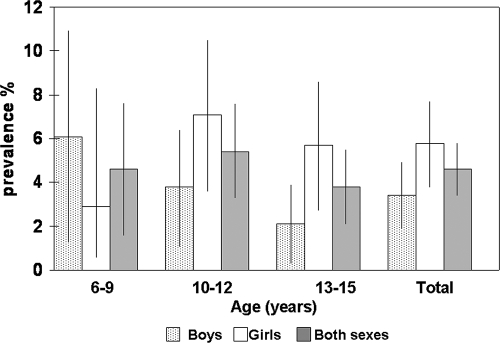

IgG anti-HEV antibodies were detected in 57 (4.6%; 95% CI, 3.4 to 5.8) of the 1,249 samples studied. The prevalence of anti-HEV antibodies was higher in girls (5.8%; 95% CI, 4.0 to 7.7) than in boys (3.4%; 95% CI, 2.2 to 5.1) (P = 0.6).

Figure 1 shows the distribution according to age and sex. The prevalence of IgG anti-HEV antibodies slightly and nonsignificantly decreased with age, from 4.6% (95% CI, 2.2 to 8.3) in children aged 6 to 9 years to 3.8% (95% CI, 2.4 to 5.7) in children aged 13 to 15 years (P = 0.4).

FIG. 1.

Prevalences (and 95% CI) of IgG anti-HEV in children in Catalonia in 2001 by age and sex.

The prevalence was higher in children living in urban areas (5.0%; 95% CI, 3.7 to 6.4), those not born in Spain (12.5%; 95% CI, 2.7 to 32.4), and those in social classes IV and V (5.8%; 95% CI, 3.8 to 8.0) compared with children living in rural areas (3.1%; 95% CI, 1.4 to 5.8), those born in Spain (4.4%; 95% CI, 3.3 to 5.6), and those in social classes I to III (4.4%; 95% CI, 2.8 to 6.5), although the differences were not statistically significant. The prevalence of anti-HEV was not associated with any of the medical variables studied (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of anti-HEV antibodies in schoolchildren aged 6 to 15 years in Catalonia in 2001 by sociodemographic and medical variables

| Variable | No. (% [95% CI]) of patients positive for anti-HEV antibodies | No. of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 22 (3.4 [2.2-5.1]) | 642 |

| Female | 35 (5.8 [4.0-7.7]) | 607 |

| Habitat | ||

| Urban | 48 (5.0 [3.7-6.4]) | 960 |

| Rural | 9 (3.1 [1.4-5.8]) | 289 |

| Place of birth | ||

| Spain | 54 (4.4 [3.3-5.6]) | 1,225 |

| Europe | 1 (16.7 [0.4-64.1]) | 6 |

| Asia, Africa, or America | 2 (11.1 [1.4-34.7]) | 18 |

| Social class | ||

| I to III | 23 (4.4 [2.8-6.5]) | 524 |

| IV or V | 27 (5.8 [3.8-8.0]) | 467 |

| VI | 7 (9.2 [3.8-18.1]) | 76 |

| Place of birth of parents | ||

| Spain (either or both parents) | 53 (4.4 [3.3-5.6]) | 1,200 |

| Other country(ies) (both parents) | 4 (8.2 [2.3-19.6]) | 49 |

| Accidents causing bleeding wounds | ||

| Yes | 10 (3.2 [1.6-5.8]) | 311 |

| No | 47 (5.1 [3.7-6.5]) | 928 |

| Dental extractions | ||

| Yes | 14 (4.8 [2.6-7.9]) | 294 |

| No | 43 (4.5 [3.3-5.9]) | 955 |

| Surgical interventions | ||

| Yes | 11 (2.9 [1.5-5.2]) | 375 |

| No | 46 (5.3 [3.8-6.8]) | 874 |

| History of acute viral hepatitis | ||

| Yes | 1 (25.0 [0.6-80.6]) | 4 |

| No | 56 (4.5 [3.4-5.7]) | 1,245 |

IgM anti-HEV antibodies, suggesting recent HEV infection, were detected in two (3.5%) of the children with IgG anti-HEV antibodies. Both were aged 12 years, were asymptomatic, had no past history of acute viral hepatitis, were born in Spain, and had IgG anti-HAV and anti-hepatitis B virus antibodies. HEV RNA determination could not be performed, due to the lack of sufficient serum samples.

Four of the children studied had histories of acute hepatitis; one had IgG anti-HEV antibodies, and three had only IgG anti-HAV antibodies, without IgM anti-HAV antibodies, indicating past HAV infection.

This is the first large study analyzing the prevalence of IgG anti-HEV antibodies in healthy children in Spain. The overall prevalence of anti-HEV antibodies was 4.6%, slightly lower than the prevalence detected in adults (7.3%) (4), suggesting that HEV can also be acquired during early childhood. Most studies of the seroprevalence of HEV infection have been performed in developing countries in Asia and Mexico, with widely various results, ranging from a very low prevalence of 0.7 to 2.6% in children and young people aged 0 to 20 years to more than 67.7% in rural Egypt (1, 5, 7, 9, 21). There are few large studies of developed counties. A Taiwanese study of 2,538 preschool children found prevalences of 3.9% in aboriginal children and 1.7% in children living in urban areas, and as in our study, females had a higher prevalence than males and the rates of IgG anti-HEV tended to decline with age (10). A Japanese study also found a low prevalence of IgG anti-HEV (<5%) (18).

The slight decrease in the prevalence of IgG HEV antibodies with age might be related to the durability of detection of these antibodies, which has not been well established after acute infection (8). Our group found a significant reduction of 64% in IgG anti-HEV a few years after HEV infection (3). The decrease could also be related to improved hygienic conditions (10), although this seems improbable due to the short study period. The possibility of a lack of detectable antibody response should also be considered (8). Most immunological anti-HEV antibody testing methods use HEV peptides from open reading frames 2 and 3 from at least two geographically distinct HEV strains representative of those from countries of endemicity (1, 6, 12, 15, 21). These strains show some differences in the amino acid sequences of the major epitopes compared with the most recently identified strains (17), justifying the lower sensitivity and the differing results obtained by serological testing using the same panel of sera with or without anti-HEV (12). The low prevalence of IgM anti-HEV antibodies found is related to the fact that the study population was healthy children and probably indicates that positivity for these antibodies is related to asymptomatic cases of acute hepatitis E occurring during the study.

This cross-sectional study found no association between any study variable and HEV infection and therefore cannot explain the mechanisms of HEV transmission in children. Hygienic and health conditions are probably important factors in the reduced prevalence of HEV infection, but a prospective study would be necessary to determine their true importance.

In conclusion, this study found a prevalence of anti-HEV antibodies of 4.6% in Spanish children, suggesting that some children are exposed to HEV in early childhood.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Directorate of Public Health, Generalitat of Catalonia.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 March 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arankalle, V. A., M. S. Chadha, S. D. Chitambar, A. M. Walimbe, L. P. Chobe, and S. S. Gandhe. 2001. Changing epidemiology of hepatitis A and hepatitis E in urban and rural India (1982-98). J. Viral Hepat. 8:293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reference deleted.

- 3.Buti, M., P. Clemente, R. Jardi, M. Formiga-Cruz, M. Schaper, A. Valdes, F. Rodriguez-Frias, R. Esteban, and R. Girones. 2004. Sporadic cases of acute autochthonous hepatitis E in Spain. J. Hepatol. 41:126-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buti, M., A. Dominguez, P. Plans, R. Jardi, M. Schaper, J. Espunes, N. Cardenosa, F. Rodriguez-Frias, R. Esteban, A. Plasencia, and L. Salleras. 2006. Community-based seroepidemiological survey of hepatitis E virus infection in Catalonia, Spain. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13:1328-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding, X., T. C. Li, S. Hayashi, N. Masaki, T. H. Tran, M. Hirano, M. Yamaguchi, M. Usui, N. Takeda, and K. Abe. 2003. Present state of hepatitis E virus epidemiology in Tokyo, Japan. Hepatol. Res. 27:169-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erker, J. C., S. M. Desai, and I. K. Mushahwar. 1999. Rapid detection of hepatitis E virus RNA by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction using universal oligonucleotide primers. J. Virol. Methods 81:109-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fix, A. D., M. Abdel-Hamid, R. H. Purcell, M. H. Shehata, F. Abdel-Aziz, N. Mikhail, H. el Sebai, M. Nafeh, M. Habib, R. R. Arthur, S. U. Emerson, and G. T. Strickland. 2000. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E in two rural Egyptian communities. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62:519-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khuroo, M. S., S. Kamili, M. Y. Dar, R. Moecklii, and S. Jameel. 1993. Hepatitis E and long-term antibody status. Lancet 341:1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin, C. H., J. C. H. Wu, T. T. Chang, W. Y. Chang, M. L. Yu, A. W. Tam, S. C. H. Wang, Y. H. Huang, F. Y. Chang, and S. D. Lee. 2000. Diagnostic value of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM anti-hepatitis E virus (HEV) tests based on HEV RNA in an area where hepatitis E is not endemic. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3915-3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin, D. B., J. B. Lin, S. C. Chen, C. C. Yang, W. K. Chen, and C. J. Chen. 2004. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis E virus infection among preschool children in Taiwan. J. Med. Virol. 74:414-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mansuy, J. M., J. M. Peron, F. Abravanel, H. Poirson, M. Dubois, M. Miedouge, F. Vischi, L. Alric, J. P. Vinel, and J. Izopet. 2004. Hepatitis E in the south west of France in individuals who have never visited an endemic area. J. Med. Virol. 74:419-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mast, E. E., M. J. Alter, P. V. Holland, and R. H. Purcell. 1998. Evaluation of assays for antibody to hepatitis E virus by a serum panel. Hepatology 27:857-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizuo, H., Y. Yazaki, K. Sugawara, F. Tsuda, M. Takahashi, T. Nishizawa, and H. Okamoto. 2005. Possible risk factors for the transmission of hepatitis E virus and for the severe form of hepatitis E acquired locally in Hokkaido, Japan. J. Med. Virol. 7:341-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. 1980. Classification of occupations. HMSO, London, United Kingdom.

- 15.Paul, D. A., M. F. Knigge, A. Ritter, R. Gutierrez, T. Pilot-Matias, K. H. Chau, and G. J. Dawson. 1994. Determination of hepatitis E virus seroprevalence by using recombinant fusion proteins and synthetic peptides. J. Infect. Dis. 169:801-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadler, G. J., G. F. Mells, N. H. Shah, I. M. Chesner, and R. P. Walt. 2006. UK acquired hepatitis E—an emerging problem? J. Med. Virol. 78:473-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlauder, G. G., and I. K. Mushahwar. 2001. Genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis E virus. J. Med. Virol. 65:282-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka, E., A. Matsumoto, N. Takeda, T. C. Li, T. Umemura, K. Yoshizawa, Y. Miyakawa, T. Miyamura, and K. Kiyosawa. 2005. Age-specific antibody to hepatitis E virus has remained constant during the past 20 years in Japan. J. Viral Hepat. 12:439-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waar, K., M. M. Herremans, H. Vennema, M. P. Koopmans, and C. A. Benne. 2005. Hepatitis E is a cause of unexplained hepatitis in The Netherlands. J. Clin. Virol. 33:145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reference deleted.

- 21.Zakaria, S., R. Fouad, O. Shaker, S. Zaki, A. Hashem, S. S. El-Kamary, G. Esmat, and S. Zakaria. 2007. Changing patterns of acute viral hepatitis at a major urban referral center in Egypt. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:30-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]