Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) strains from the highly HLA-A11-positive Chinese population are predominantly type 1 and show a variety of sequence changes (relative to the contemporary Caucasian prototype strain B95.8) in the nuclear antigen EBNA3B sequences encoding two immunodominant HLA-A11 epitopes, here called IVT and AVF. This has been interpreted by some as evidence of immune selection and by others as random genetic drift. To study epitope variation in a broader genomic context, we sequenced the whole of EBNA3B and parts of the EBNA2, 3A, and 3C genes from each of 31 Chinese EBV isolates. At each locus, type 1 viruses showed <2% nucleotide divergence from the B95.8 prototype while type 2 sequences remained even closer to the contemporary African prototype Ag876. However, type 1 isolates could clearly be divided into families based on linked patterns of sequence divergence from B95.8 across all four EBNA loci. Different patterns of IVT and AVF variation were associated with the different type 1 families, and there was additional epitope diversity within families. When the EBNA3 gene sequences of type 1 Chinese strains were subject to computer-based analysis, particular codons within the A11-epitope-coding region were among the few identified as being under positive or diversifying selection pressure. From these results, and the observation that mutant epitopes are consistently nonimmunogenic in vivo, we conclude that the immune selection hypothesis remains viable and worthy of further investigation.

Herpesviruses are genetically stable agents which are considered to have slowly evolved with their host species over long periods of evolutionary time (19, 20). As a result, virus and host have typically reached a balance that allows widespread infection of host populations and life-long persistence within the individual host without threatening host survival. In contrast, these same agents can be life-threatening in T-cell-immunocompromised individuals (25, 27), indicating that cellular immune responses play an important role in maintaining the virus-host balance. A still obscure aspect of herpesvirus-host relationships is the extent to which these T-cell responses, which are so crucial at the level of the individual host, might have shaped the long-term evolution of the virus within its host species. This is a difficult issue to address, not only because the process is too slow to study prospectively but also because of the nature of T-cell recognition itself. Thus, T cells detect peptides that are derived from viral proteins and presented at the cell surface in a complex with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules (31). Because the MHC locus is highly polymorphic in most human populations and different MHC alleles present different viral peptides (40), it is only in rare circumstances that pressure from population immunity against an individual peptide epitope might be sufficient to have detectable effects.

One possible example of such circumstances emerged during the study of CD8+-cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a gammaherpesvirus widespread in human populations. In HLA-A11-positive Caucasians, the memory CTL response to EBV latent cycle antigens is frequently dominated by T cells restricted through this allele and recognizing one of two peptide epitopes derived from the virus-encoded nuclear antigen EBNA3B; these are the immunodominant IVTDFSVIK epitope (EBNA3B codons 416 to 424, called IVT) and the next-most-dominant AVFDRKSDAK epitope (EBNA3B codons 399 to 408, called AVF) (7, 9). These same responses are also prominent during primary infection (32), at a time when successful EBV transmission to the naive host appears critically dependent upon the proliferation of latently infected B cells expressing the immunodominant EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C antigens (28). We found that the IVT and AVF epitope sequences were very frequently altered (relative to the Caucasian type 1 prototype strain, B95.8) in EBV strains isolated from highly HLA-A11-positive populations in lowland Papua New Guinea (6) and southern China (7). Furthermore, most nucleotide changes caused amino acid replacement in the key anchor positions (amino acids 2 or 9/10 in the epitope sequence) that are the major determinants of epitope affinity for HLA-A11 molecules. Accordingly, the variant epitopes formed less stable complexes with HLA-A11 and/or were not well-recognized by Caucasian donor CTLs specific for the wild-type (i.e., B95.8) IVT and AVF sequences (2, 6, 7, 17, 21). In a paper accompanying the present report, our group went on to describe more accurately the range of IVT and AVF variants found in Chinese EBV strains and provided evidence that these variants were indeed nonimmunogenic in vivo (21).

Such evidence is consistent with the view that, under pressure from the HLA-A11-restricted CTL response in a population where >50% of individuals carry this allele, EBV strains with epitope-loss sequence variants have enjoyed a selective advantage. However a number of other observations have cast doubt upon the significance of such HLA-A11 epitope changes (13). Thus, one of the combinations of IVT and AVF variants seen among EBV isolates from China was very common not just in lowland Papua New Guinea but also in highland people, in whom HLA-A11 is rare. Furthermore, the same Papua New Guinea viruses also showed coincidental changes, affecting anchor residues, in two epitopes within EBNA3A that were restricted through HLA alleles (B8 and B35) not found at all in these populations (2). A broader study comparing Caucasian, African, Chinese, and Papua New Guinea virus strains across several other known epitope regions, mainly in EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C, again found no correlation between sequence variation within the epitope and representation of the restricting HLA allele in the host population. That study also found no evidence for positive selection in these regions from an analysis of replacement/silent mutation ratios (14).

These various studies highlight the debate as to whether the loss of HLA-A11 epitopes seen among Chinese EBV strains really reflects immune selection or is simply a product of random evolutionary drift. Certainly other sequence polymorphisms have been described that distinguish Chinese from Caucasian and African EBV strains (1, 4, 11, 18, 22, 23, 33), consistent with slow evolutionary divergence of the virus through random drift in geographically separate host populations. Here, we have carried out extensive sequencing of both type 1 and type 2 Chinese EBV isolates across several latent genes in order to analyze HLA-A11 epitope polymorphism in a broader genomic context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus isolates.

The panel of 31 virus isolates studied is the same as that described in the accompanying paper (21); all were rescued as spontaneous lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) from the cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells of 17 healthy unrelated Chinese donors and 14 unrelated Chinese nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) patients residing in Hong Kong or Canton, China. Most of these isolates had been typed at the EBNA2, 3A, 3B, and 3C loci in an earlier study (22). One of the isolates not included in that earlier study, NPC15, was selected as the prototype 1 Chinese strain because this had been successfully rescued from the NPC15 spontaneous LCL into a marmoset B cell, thereby generating a cell line producing high titers of a transformation-competent Chinese virus strain (A. B. Rickinson, unpublished data). The Caucasian prototype 1 strain B95.8 and the African prototype 2 strain Ag876 were included in all sequencing studies as reference isolates.

Sequencing of EBV latent genes.

Total genomic DNA was prepared from LCL pellets by standard methods, and the relevant regions of the EBV genome were amplified by PCR to generate suitable templates for DNA sequence analysis. For each isolate, sequences corresponding to EBNA1 (codons 475 to 535, or in selected cases codons 460 to 641), EBNA2 (codons 109 to 259), EBNA3A (codons 114 to 320), EBNA3B (entire gene), EBNA3C (codons 121 to 293), and LMP1 (codons 318 to 386) were amplified by using the primer combinations described in Table 1; note that in the case of EBNA3B, the entire coding region was initially amplified as a series of short fragments with primer pairs which contiguously spanned the open reading frame and the intervening intron sequence. PCR amplifications were done under the following conditions: EBNA1, 35 cycles of 94°C for 60 s, 62°C for 90 s, and 72°C for 240 s; EBNA2, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 45°C for 90 s, and 72°C for 120 s; EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C, 40 cycles of 94°C for 60 s, 45°C for 90 s, and 72°C for 120 s; LMP1, 40 cycles of 94°C for 60 s, 62°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 120 s. For the Chinese prototype 1 virus strain NPC15, the entire coding regions of EBNA3A and EBNA3C were also amplified with the primers listed in Table 1, together with the complete coding sequence of EBNA2 as previously described (39). PCR products were gel purified with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Crawley, West Sussex, United Kingdom) and directly sequenced by using a BigDye, version 3.0, PCR sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom) with a suitable primer. All samples were analyzed with an Applied Biosystems 3700 automated sequencer (Functional Genomics Laboratory, School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used to amplify EBV sequences

| Gene (codons) | Forward primer | B95.8 coordinates | Reverse primer | B95.8 coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBNA1 (475-535) | GTTTGGAAAGCATCGTGGTC | 109340-109360 | ATTCCAAAGGGGAGACGACT | 109577-109558 |

| (460-642) | GTTTGGAAAGCATCGTGGTC | 109340-109360 | AACAGCACGCATGATGTCTACTGGGGATTT | 109969-109940 |

| EBNA2 (109-259) | AGGGATGCCTGGACACAAGA | 48810-48829 | GTAATGGCATAGGTGGAATG | 49374-49355 |

| EBNA3A | ATGGACAAGAACAGGCCGGG | 92243-92262 | CATGGCATACATTATGTACATC | 92747-92726 |

| CGCATCGACACACGAGCCATA | 92670-92690 | TACAATGTTACCCACGGAGCT | 93050-93030 | |

| GCCGGCACCTTTAAGCTGCCG | 92970-92990 | AGCCGGCATTCCAAGCCTGTGC | 93303-93282 | |

| GCCCTGGGCACCACTAGTATC | 93222-93242 | CGACCCGTGACTGGTAGCTGTC | 93650-93629 | |

| GAAACCAAGACAGAGGTCC | 93596-93615 | TCAGCACGCAAACGAGCCAG | 94150-94131 | |

| CGGGAGCGTTGGAGGCCCGCAC | 94056-94077 | CTGTGTTGCCGGTACCGGAGGT | 94424-94403 | |

| GCCCCGTTGAGGGCTAGTATG | 94374-94394 | AGACACGGGAACCCCGGGATGGT | 94799-94777 | |

| GACGTGGTCCAACATCAGCTGGA | 94725-94747 | GGCCTCATCTGGAGGATCTTGT | 95162-95141 | |

| TCAGCTGTTGTTCACATGTGT | 95096-95117 | AGAGAGTTCAAAGGGGCCAAT | 95502-95482 | |

| EBNA3B | CTGAATAATGAAGAAAGCGTG | 95346-95366 | TTGCTCAAGGAATAAACTGCC | 95829-95809 |

| CAGGCTCCAGTGATCCAACTA | 95662-95682 | ATCTTTTGGTTTTGGTCTGA | 96134-96115 | |

| CTTGTGACTGCTACGCTAGGAT | 96031-96052 | TCGTCATCCTCAACAATTAT | 96509-96489 | |

| CGCCAGTGCACCGGGAGACCC | 96331-96351 | CAAAGGTTGCCATGGCTCCAG | 96873-96853 | |

| AAGAAGGACCACACTCATATACG | 96298-96320 | TTTTCAAGAAGGTCTAGCAT | 96962-96943 | |

| CTCCAGCGACCACCCACGCAG | 96790-96810 | GGACGTTAGTGGTTGGATTTC | 97167-97147 | |

| ACCGGTGACCTAGGCATAGAG | 97057-97077 | GGCTGATAGGAATGTGCCC | 97457-97438 | |

| CCCTTGCGGATGCAGCCAAT | 97333-97352 | AGCGGCTTGACGCTCAAGGGC | 97824-97804 | |

| GGGAGACCATCACTTAAGTT | 97777-97796 | AGCAGTTCCTCCGCACTCCAG | 98166-98146 | |

| TCGAGGCCTATACAGAGCCC | 98051-98070 | ATCATGCTCGCCGGTAGTCTG | 98457-98437 | |

| EBNA3C | ATGGAATCATTTGAAGGACAG | 98371-98391 | GTGTGTCTAACCCACTATCGAG | 98859-98838 |

| CAATCGCACCTGCAAGCGCTA | 98805-98825 | GACACCCATGAAACGCACGAAATC | 99323-99300 | |

| CACCACATCTGGCAAAACTTGCT | 99255-99276 | GCTCCACGGTCACTGATGATTG | 99834-99813 | |

| TCAATGTTAGCAACGGGAGGGT | 99448-99518 | GGCTCGTTTTTGACGTCGGC | 100090-100072 | |

| AGAAGGGGAGCGTGTGTTGT | 99939-99958 | TGCATTTGTGTAATTTCACGAC | 100429-100408 | |

| CAGTCCACCGGCCGTAAACCTC | 100362-100383 | AAGATGATTGGAGCCCGTGGGC | 100806-100785 | |

| GTTACATCCAGACGTTGCTGC | 100639-100660 | GAGATGACCATGATGTGTCAGA | 101082-101061 | |

| CTGCAATCGGAGACAGGCCCAC | 101001-101022 | CTAACAGGGGTCACCTTGGATC | 101448-101427 | |

| LMP1 (318-386) | GACATGGTAATGCCTAGAAG | 168130-168149 | GCGACTCTGCTGGAAATGAT | 168389-168370 |

Computational analysis of DNA sequences.

Manipulation, alignment, and presentation of DNA and protein sequences were carried out with the GCG package (Accelrys, Inc.). Construction of phylogenetic trees by the neighbor-joining method used programs from the PHYLIP package (8) obtained from http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html.

Evaluation of positively selected loci in the coding regions of the EBNA3 genes was performed by using the program Codeml in the PAML package (version 3.13) (24), obtained from http://abacus.gene.ucl.ac.uk. Codeml (using its option of codon-based analysis) is a program for probabilistic modeling of characteristics of evolutionary diversity in aligned sets of protein coding sequences. It calculates by maximum-likelihood methods the instantaneous rates of synonymous change (dS) and nonsynonymous change (dN) for an aligned set of protein coding sequences. The possible occurrence of positive selection in a data set is then detected as a situation in which the dN/dS ratio (called ω) is estimated to be greater than unity, i.e., mutations that cause amino acid changes are being fixed in the population represented by the data set at a higher rate than silent changes. Evaluation of specific sites in the alignment at which positive selection may have occurred is accomplished by Bayesian estimation of the probability of ω being greater than one for each such site. Note that the maximum-likelihood analysis does not assume that the contemporary prototypes (B95.8 and Ag876) predate the test isolates.

Codeml provides a number of models for fitting distributions of ω values to the input sequence data, and the following were employed in analyzing the EBNA3 gene sequences, with compatible results: model 1, neutral, 2 classes, namely ω = 0 and ω = 1; model 2, selection, 3 classes, ω = 0, ω = 1, and ω > 1; model 3, discrete, 2, 3 and 8 classes of ω values examined, with a value of ω for each class assigned by the program. Models 7 and 8, with more complex distributions of ω, were also investigated, but their outputs were judged unsatisfactory because in each case the set of ω classes computed contained several of identical ω value, presumably because the input sequence data were not sufficiently diverse to allow nontrivial fitting to the model. Lastly, model B as described by Yang and Nielsen (37) was applied to examine the combined site and lineage specificity of positive selection. This model provides two classes of ω values for the whole sequence set and an additional class with ω of >1 for application in foreground lineages that had been specified as of specific interest for evaluation of occurrence of positive selection. In all Codeml runs, equilibrium frequencies of codons were estimated as products of nucleotide frequencies at each codon position, the transition/transversion rate ratio was calculated in the program, and no molecular clock was imposed. In all appropriate cases, the program was run separately with high and low initial values of ω to check the validity of computational convergence.

RESULTS

Sequencing of a Chinese prototype 1 virus at the EBNA2, 3A, 3B, and 3C loci.

The IVT and AVF epitope-encoding sequences lie within the EBNA3B gene, one of four latent genes whose linked polymorphisms define the broad division of EBV strains into types 1 and 2. These are the EBNA2 gene, where the prototype 1 and 2 alleles share only 64% nucleotide identity (5), and the EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C genes (arranged in tandem 40 kb downstream in the virus genome), where the prototype 1 and 2 alleles share 90, 80, and 81% nucleotide identity, respectively (29). By comparison, little is yet known about sequence diversity at these loci among virus strains of the same type. As a starting point for the present study, therefore, we selected one Chinese type 1 isolate, NPC15, for complete sequencing across the four type-specific genes. For each of the four genes, the numbers of nucleotide and amino acid changes in the Chinese prototype 1 virus relative to the Caucasian prototype 1 (B95.8) sequence are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Sequence divergence of Chinese prototype 1 virus NPC15 from B95.8 prototype

| EBV gene | No. of nucleotide changes | % Nucleotide identity | No. of amino acid changes | % Amino acid identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBNA2 | 5 | 99.6 | 3 | 99.4 |

| EBNA3A | 35 | 98.8 | 19 | 98.0 |

| EBNA3B | 42 | 98.5 | 24 | 97.4 |

| EBNA3C | 23 | 99.2 | 9 | 99.1 |

NPC15 showed relatively low levels of nucleotide (<2%) and amino acid (<3%) divergence from the B95.8 prototype at EBNA2, 3A, 3B, and 3C. Note that each of the EBNA3 genes contains repeats in the B95.8 sequence (29) and that variations in repeat numbers have been ignored in the overall analysis. NPC15 retains the same repeat structure as B95.8 within EBNA3A, carries one fewer 60-bp repeat than B95.8 at EBNA3B, and carries eight fewer 15-bp repeats but has three more 39-bp repeats than B95.8 at EBNA3C. The high level of sequence relatedness between the Chinese and Caucasian prototype 1 viruses at these loci indicated that the previously reported sequence changes at the IVT and AVF epitopes in EBNA3B were occurring within relatively well-conserved latent cycle genes.

Sequencing of EBNA3B identifies families of sequence variation among type 1 viruses.

We went on to sequence the complete EBNA3B gene in a panel of 25 more type 1 Chinese virus isolates (derived both from healthy donors and from NPC patients). The panel was found to contain one virus with a wild-type (i.e., B95.8-like) sequence in the IVT and AVF epitopes and representatives of all but one of the nine combinations of IVT and AVF sequence variants identified among type 1 Chinese virus strains in the accompanying report; the one variant combination not available (AVF/SIL2, IVT/N9) was found in only 1 of 64 type 1 viruses analyzed in that study (21).

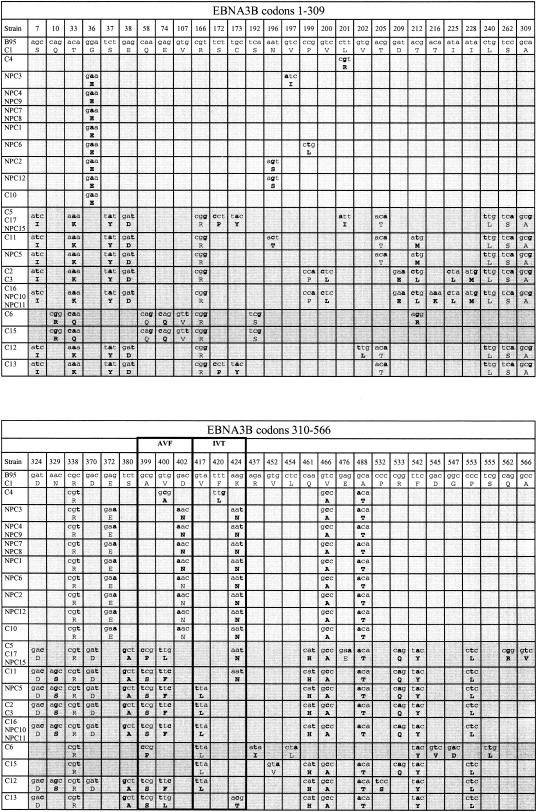

Figure 1 presents the results of this analysis for all 25 type 1 isolates as well as for NPC15; the figure shows only those codons where nucleotide changes occurred relative to the B95.8 prototype sequence and, in cases of amino acid replacement, identifies the amino acid change. Apart from one virus (C1) which was identical to B95.8 throughout EBNA3B, there were three main patterns of sequence change, identified in the figure by different degrees of shading. It is important to stress that these changes always occurred against a background of >98% nucleotide identity between Chinese strains and the B95.8 prototype. The Li family of viruses (C4 to C10) almost all showed the same 16 nucleotide and 11 amino acid changes relative to B95.8 EBNA3B, whereas the Wu family (C11 to NPC11) had 51 nucleotide and 31 amino acid changes in common; only 6 of these nucleotide changes and 3 of the amino acid changes were shared between the two families. The distinction between the Li and Wu families was also apparent at the 60-bp repeat locus lying between codons 758 and 797 on the figure, with Wu family viruses all having one extra repeat. Interestingly, there were three virus strains (the original prototype NPC15 plus C17 and C5) with identical sequences which followed the Wu family consensus throughout the 5′ half of EBNA3B but switched to the Li consensus in the 3′ half between indicator polymorphisms at codons 610 and 645. These Wu/Li interfamily recombinants are placed between the Wu and Li family groups in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Sequence changes in the entire EBNA3B gene of type 1 Chinese EBV strains relative to the Caucasian prototype 1 B95.8 EBNA3B gene. Strains are aligned vertically under the B95.8 prototype and are identified in the left-hand column of each block; strains within the same box in that column have identical sequences. All other columns represent individual EBNA3B codons (numbered at the top) where a nucleotide change relative to the B95.8 sequence was detected in one or more Chinese viruses. The nucleotide changes are shown in boldface type and resulting amino acid changes are also shown in boldface type; unchanged nucleotides and amino acids are not in boldface type. To illustrate the familialrelationships among the Chinese strains, blocks of the Li family sequence are shown in light shading, blocks of the Wu family sequence are shown in medium shading, and blocks of sporadic (Sp) sequence are shown in dark shading. One Chinese virus strain, C1, is entirely B95.8-like. Strains C4 to C10 constitute the Li family, strains C11 to NPC11 constitute the Wu family, strains C5, C17, and NPC15 are Wu/Li recombinants, and strains C6 to C13 represent various Wu/Sp recombinants. Codons lying within the AVF (399 to 408) and IVT (416 to 424) epitope regions are identified above the relevant columns. The 60-bp repeat locus with EBNA3B is also identified, and the number of repeats in each virus strain is shown.

A third, more diverse, family of viruses (C6 to C13) all showed sequences that accorded with the Wu consensus in some parts of EBNA3B but in other parts followed a different pattern of variance (here called sporadic); we refer to this family as the Wu/Sp recombinants. Thus, C6 follows a sporadic sequence through EBNA3B until marker codon 758 and then aligns with the Wu family sequence. Conversely, C12 and C13 are similar to each other and follow a Wu-like sequence (with a small number of additional changes) until codon 758, and then they switch to a sporadic sequence. The fourth member of this family, C15, combines blocks of sporadic sequence from codons 1 to 402 and from codons 645 to 758, which are very similar to sporadic sequences shown by C6 in these areas, with blocks of Wu-like sequence from codons 417 to 640 and beyond codon 758.

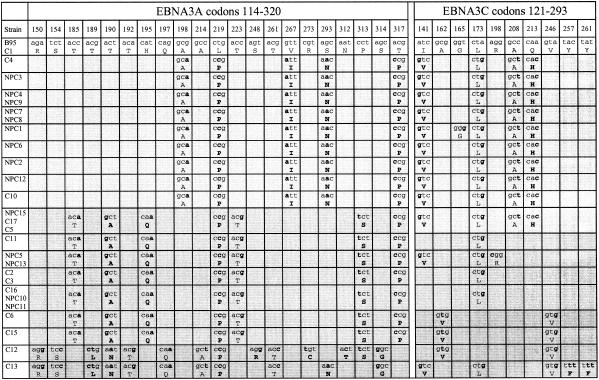

Familial sequence variation extends to the EBNA3A, 3C, and 2 loci.

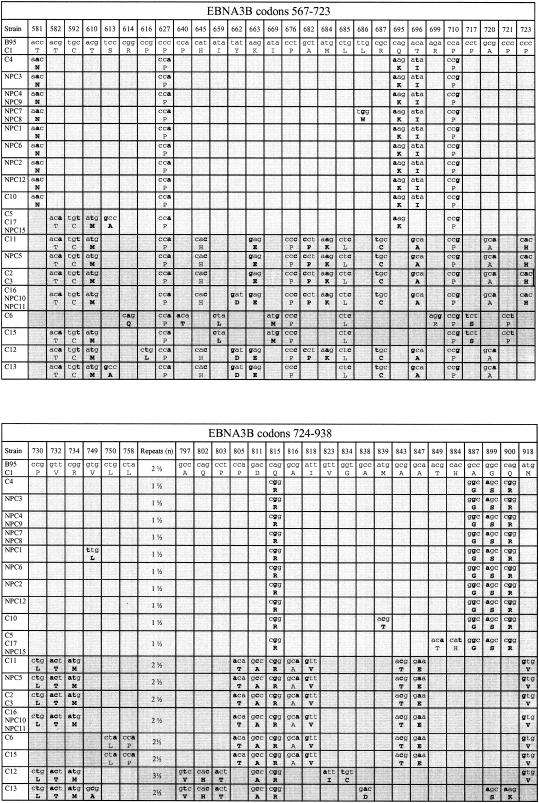

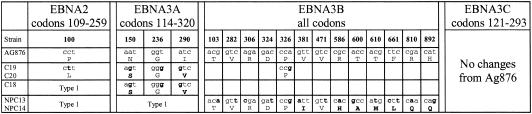

We next sequenced the same panel of 26 type 1 viruses across regions of the EBNA3A and 3C genes, i.e., genes situated immediately upstream and downstream of EBNA3B in the viral genome. The regions sequenced (EBNA3A codons 114 to 320 and EBNA3C codons 121 to 293) were chosen since they each contained a number of changes relative to B95.8 in the NPC15 prototype sequence. Figure 2 summarizes all of the sequence polymorphisms observed in both EBNA3A and 3C for all 26 viruses, with the isolates being grouped as in Fig. 1 into Li family, Wu/Li recombinants, Wu family, and Wu/Sp recombinants.

FIG. 2.

Sequence changes in parts of the EBNA3A (codons 114 to 320) and EBNA3C (codons 121 to 293) genes of type 1 Chinese EBV strains relative to the Caucasian prototype 1 B95.8 sequence. The different virus strains are aligned vertically under the B95.8 prototype by using the same format as adopted in Fig. 1, with the nucleotide and amino acid changes identified in boldface type and the different blocks of family sequences identified by different degrees of shading as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

It is clear that the familial patterns observed at the EBNA3B locus extend to both EBNA3A and 3C. Thus, the Li family viruses (C4 to C10) had five nucleotide and four amino acid changes in common relative to B95.8 EBNA3A, and the Wu family (C11 to NPC11) had seven nucleotide and five amino acid changes in common. Only two of these nucleotide and amino acid changes were shared between both families. Of the four Wu/Sp recombinants, C6 and C15 followed the Wu consensus at EBNA3A, whereas C12 and C13 had similar (but not identical) sporadic sequences. Likewise, at EBNA3C, the Li family had four nucleotide and two amino acid changes relative to B95.8, whereas the Wu family followed the B95.8 sequence except for showing one of the two silent nucleotide changes present in Li viruses. The Wu/Sp recombinants followed one of two patterns of sporadic sequence change at this locus. Finally, it was interesting that the three Wu/Li recombinants (C5, C17, and NPC15) with Wu sequences in the 5′ half and Li sequences in the 3′ half of EBNA 3B indeed followed the Wu consensus upstream at EBNA3A and the Li consensus downstream at EBNA3C.

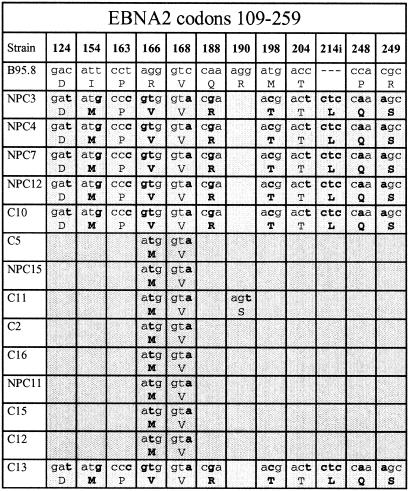

We then selected representative viruses from each of the above-described family groups for sequencing at the EBNA2 locus some 40 kb upstream of EBNA3A in the viral genome. Sequence divergence from B95.8 within the region analyzed (EBNA2 codons 109 to 259) is shown in Fig. 3. Familial patterns were again apparent at this locus, with five Li family viruses (NPC3 to C10) showing 11 nucleotide and 6 amino acid changes plus the addition of an extra codon (for a leucine residue) after codon 211 in the B95.8 sequence and four Wu family viruses (C2 to NPC11) showing only 2 nucleotide changes and a single amino acid change. The two representatives of viruses with Wu/Li recombination within EBNA3B (C5 and NPC 15) were Wu-like at EBNA2, as would have been predicted for a single crossover, whereas the three members of the more diverse Wu/Sp recombinant family were Wu-like in two cases (C15 and C12) and Li-like in one (C13).

FIG. 3.

Sequence changes in a part of the EBNA2 gene (codons 109 to 259) of type 1 Chinese EBV strains relative to the Caucasian prototype 1 B95.8 sequence. The data are derived from a subset of the full panel of Chinese strains including five members of the Li family (NPC3 to C10), two Wu/Li recombinants (C5 and NPC15), four members of the Wu family (CT1 to NPC11), and three Wu/Sp recombinants (C15 to C13). The different virus strains are aligned vertically under the B95.8 prototype, and the nucleotide and amino acid changes and different blocks of family sequences are identified as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

Limited sequence variation among type 2 viruses at the EBNA2 and EBNA3 loci.

In the context of type 2 virus sequences, we had only a limited number of Chinese virus strains available for analysis, namely two isolates (C19 and C20) which were type 2 at all four type-specific loci (EBNA2, 3A, 3B, and 3C), one intertypic recombinant (C18) which was type 2 at all the EBNA3 loci, and two intertypic recombinants (NPC13 and NPC14) which were type 2 only at EBNA3B and 3C. The fact that all five viruses had retained the wild-type Ag876 sequence in the IVT and AVF epitope regions of EBNA3B led us to ask whether this reflected a specifically local conservation or a more general pattern of conservation seen throughout the type 2 EBNA genes. The relevant data are summarized in Fig. 4 and show that the latter is indeed the case. The two available viruses with type 2 EBNA2 genes (C19 and C20) both showed only one (nonconservative) nucleotide change relative to Ag876. Within the sequenced fragment of EBNA3A, the available viruses (C18, C19, and C20) showed the same three nucleotide and two amino acid changes relative to Ag876. Throughout the whole of EBNA3B, the same group of viruses (C18, C19, and C20) showed only 1 silent nucleotide change, whereas the other group (NPC13, NPC14) showed 14 nucleotide and 7 amino acid changes. Within the sequenced fragment of EBNA3C, all five viruses retained the Ag876 sequence.

FIG. 4.

Sequence changes in the EBNA2 (codons 109 to 259), EBNA3A (codons 114 to 320), EBNA3B (entire gene), and EBNA3C (codons 121 to 293) genes of type 2 Chinese EBV strains relative to the African prototype 2 Ag876 sequence. Virus strains are aligned vertically under the Ag876 prototype, and strains in the same box have identical sequences. Nucleotide and amino acid changes are identified as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Note that only the C19 and C20 strains are type 2 at all four gene loci. The other three strains are type 1-type 2 recombinants with type 2 sequences only at the EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C loci (C18) or only at the EBNA3B and 3C loci (NPC13 and NPC14).

Summary of familial relationships among Chinese virus strains at six latent gene loci: the context of HLA-A11 epitope polymorphism.

Table 3 summarizes all of the data available from sequence analysis at the EBNA2, 3A, 3B, and 3C genes for type 1 viruses (26 strains), type 1/type 2 recombinants (3 strains), and type 2 viruses (2 strains). The type 1 viruses are arranged in the table into the Li family group, the Wu/Li recombinants, the Wu family group, and the Wu/Sp recombinants; all are quite distinct from the single isolate C1, with a B95.8-like sequence at all four loci. The patterns of IVT and AVF sequence change within EBNA3B are identified for each virus to show its relationship to the broader genomic context (see below).

TABLE 3.

Sequence patterns at latent gene loci and AVF/IVT epitope change

| Type | Virus group | Strain | Sequence at:

|

EBNA1 allele (585)a | LMP1 allele (335)b | Change pattern of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBNA2 | EBNA3A | EBNA3B | EBNA3C | AVF | IVT | |||||

| 1 | B95.8-like | C1 | B95.8 | B95.8 | B95.8 | B95.8 | B95.8 (t) | B95.8 (g) | wt1c | wt1 |

| Li family | C4 | Li | Li | Li | V | Ch" | A2 | L5 | ||

| C10 | Li | Li | Li | Li | V (t) | Ch′ (d) | N4 | N9 | ||

| NPC1 | Li | Li | Li | V | Ch′ (d) | N4 | N9 | |||

| NPC2 | Li | Li | Li | V | Ch′ (d) | N4 | N9 | |||

| NPC3 | Li | Li | Li | Li | V | Ch′ (d) | N4 | N9 | ||

| NPC4 | Li | Li | Li | Li | V | Ch′ (d) | N4 | N9 | ||

| NPC6 | Li | Li | Li | V | Ch′ | N4 | N9 | |||

| NPC7 | Li | Li | Li | Li | V (t) | Ch′ (d) | N4 | N9 | ||

| NPC8 | Li | Li | Li | V | Ch′ | N4 | N9 | |||

| NPC9 | Li | Li | Li | V | Ch′ | N4 | N9 | |||

| NPC12 | Li | Li | Li | Li | V (t) | Ch′ (d) | N4 | N9 | ||

| Wu/Li recombinant | C5 | Wu | Wu | Wu/Li | Li | V (t) | Ch′ (d) | P1L2 | N9 | |

| C17 | Wu | Wu/Li | Li | V | Ch′ (d) | P1L2 | N9 | |||

| NPC15 | Wu | Wu | Wu/Li | Li | V | Ch′ (d) | P1L2 | N9 | ||

| Wu family | C11 | Wu | Wu | Wu | Wu | V (i) | Ch′ (g) | S1F2 | N9 | |

| C2 | Wu | Wu | Wu | Wu | V (i) | Ch′ (g) | S1F2 | L2 | ||

| C3 | Wu | Wu | Wu | V | Ch′ | S1F2 | L2 | |||

| C16 | Wu | Wu | Wu | Wu | V | Ch′ (g) | S1F2 | L2 | ||

| NPC5 | Wu | Wu | Wu | V | Ch′ | S1F2 | L2 | |||

| NPC10 | Wu | Wu | Wu | V | Ch′ | S1F2 | L2 | |||

| NPC11 | Wu | Wu | Wu | Wu | V (i) | Ch′ (g) | S1F2 | L2 | ||

| Wu/Sp recombinant | C6 | Wu | Sp/Wu | Sp | V | Ch′ | P1 | L2 | ||

| C15 | Wu | Wu | Sp/Wu/Sp/w | Sp | V | Ch′ (g) | wt1 | L2 | ||

| C12 | Wu | Sp | Wu/Sp | Sp | V | Ch′ (g) | S1F2 | L2 | ||

| C13 | Li | Sp | Wu/Sp | Sp | V | Ch" | S1L2 | T9 | ||

| 1/2 | Intertypic recombinant | NPC13 | Li | Wu | 2 | 2 | V | Ch′ | wt2d | wt2d |

| NPC14 | Li | Wu | 2 | 2 | V | Ch" | wt2 | wt2 | ||

| C18 | Li | 2 | 2 | 2 | T | Ch‴ | wt2 | wt2 | ||

| 2 | Ag876-like | C19 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | T | Ch‴ | wt2 | wt2 |

| C20 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | T | Ch‴ | wt2 | wt2 | ||

The EBNA1 allele is defined as either B95.8-like or as allele V or T based on published patterns of sequence divergence from the B95.8 prototype including either a valine or a threonine residue, respectively, at signature position 487 (11, 22). Representatives of the different type 1 Chinese virus family groups (all of which had a V allelic sequence) were analyzed further and could be discriminated on the basis of a threonine (t) or isoleucine (i) residue at position 585.

The LMP1 allele is defined as either B95.8-like or as allele Ch′, Ch", or Ch‴based on published patterns of sequence divergence from the B95.8 prototype (22, 23). Representatives of the different type 1 Chinese virus family groups (all of which had a Ch′ allelic sequence) were analyzed further and could be discriminated on the basis of a glycine (g) or aspartate (d) residue at position 335.

wt1, Caucasian B95.8 prototype 1 epitope sequence.

wt2, African Ag876 prototype 2 epitope sequence.

Also shown in Table 3 are expanded versions of the allelic polymorphisms already reported for this same panel of isolates (22) at two other latent gene loci, EBNA1 (6.5 kb downstream of EBNA3C) and LMP1 (a further 58 kb downstream). This is interesting since at each locus most if not all of the type 1 viruses showed essentially identical patterns of sequence divergence from B95.8; these sequences are already published and have been shown by several groups to be characteristic of Chinese strains (4, 11, 22, 23, 33). However, by taking representative isolates and extending the area sequenced within each gene, we were able to identify a single amino acid change in both EBNA1 and LMP1 that discriminates between the Li and Wu families. Thus, within EBNA1 codons 460 to 641, all type 1 viruses (except C1) followed the V-allele consensus (11, 22), except at codon 585, where just the Wu family viruses showed an additional Thr→Ile amino acid change. Likewise, within LMP1 codons 318 to 386, the great majority of type 1 viruses carried a characteristically Chinese allele (4, 33), here called Ch′ (22), with several amino acid changes relative to B95.8 plus a 30-bp deletion removing codons 343 to 352; all Ch′ sequences were identical, except at codon 335, where just the Li family viruses and Wu/Li recombinants showed an additional Gly→Asp amino acid change. We also noted that the two type 1 viruses C4 and C13, which carried a different LMP1 allele (called Ch", lacking the deletion but with its own pattern of sequence divergence from B95.8) (22), were distinct from the rest in other ways; thus, C4 was an outlier within the Li family group with its own unique IVT/AVF epitope sequences and C13 had a unique intratypic recombinant structure at the EBNA2 and 3C loci and also unique IVT/AVF epitope variation. It is also worth noting that, while neither EBNA1 nor LMP1 is type specific in its sequence divergence among EBV isolates worldwide, the two Chinese type 2 virus strains studied here were distinct from type 1 in carrying a T allele at the EBNA1 locus and a unique Ch′′′ sequence at LMP1 (22).

Table 3 not only illustrates how familial relationships within type 1 viruses run throughout all six latent gene loci analyzed but also emphasizes how the different combinations of IVT and AVF epitope mutation within EBNA3B tend to align with these family groups. Thus, all of the viruses with the AVF/N4, IVT/N9 combination of epitope sequences (C10 to NPC12) fall within the Li family, as does the rarer AVF/A2, IVT/L5 virus (C4). Likewise, all of the AVF/S1F2, IVT/L2 viruses (C2 to NPC11) fall within the Wu family, as does the rarer AVF/S1F2, IVT/N9 virus (C11). Interestingly, the three Wu/Li recombinants (C5, C17, and NPC15) are the only ones to carry the AVF/P1L2, IVT/N9 epitope combination, whereas the four members of the more diverse Wu/Sp recombinant family (C6, C15, C12, and C13) show four different patterns of epitope change, three of which are not seen in any other virus on the panel.

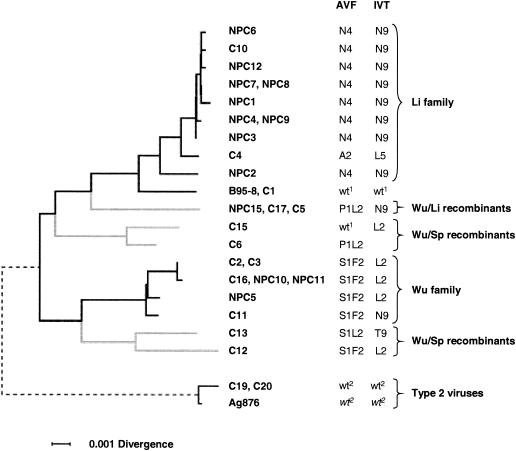

The relationship between A11 epitope polymorphism and broader patterns of sequence divergence is better appreciated in Fig. 5, which shows a phylogenetic tree of evolutionary distance (horizontal axis) between Chinese EBV strains based on available sequences at the EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C genes. Type 2 strains apparently derive from an early branch point in EBV evolution, which predates human migration out of Africa, since the Chinese type 2 viruses are clearly much closer to the contemporary African type 2 prototype Ag876 than to contemporary Chinese type 1 viruses. Indeed, from the limited data available, type 2 EBNA3 gene sequences appear not to have diversified with geographic isolation as much as type 1 sequences, and the conservation of A11 epitope loci in type 2 viruses reflects this more general trend. Among type 1 strains, the phylogenetic tree clearly identifies the separate Li family and Wu family groups, placing Li viruses closer to the B95.8 prototype. We have included in the tree the several type 1 sequences showing intratypic recombination. Strictly, recombinants cannot be accommodated accurately in a tree-based depiction of relationships, but the tree does serve to highlight that the intratypic recombinants fall into three separate groups; namely the Wu/Li recombinants and two groups of Wu/Sp recombinants. From Fig. 5, these different branches of type 1 EBV evolution in the Chinese population are clearly associated with distinct patterns of A11 epitope variation.

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic tree based on EBNA3 sequences. The tree shown was obtained by the neighbor-joining method (PHYLIP program Neighbor) by using maximum-likelihood distances between pairs of DNA sequences in the concatenated alignment of EBNA3A (part), EBNA3B (whole), and EBNA3C (part) sequences. The horizontal branches represent substitutions per nucleotide site, with the scale indicated at the foot of the tree. Branches for type 1 intratypic recombinants are drawn in grey (see text). The tree is rooted between types 1 and 2, with the branch joining types 1 and 2 (dashed line) compressed with respect to the rest of the figure. On the right, the AVF and IVT epitope sequences for each virus strain are indicated (using the same nomenclature as in Table 3), and viruses of the Li and Wu families, Wu/Li recombinants, Wu/Sp recombinants, and type 2 viruses are identified. wt, wild type; wt1, Caucasian B95.8 prototype 1 epitope sequence; wt2, African Ag876 prototype 2 epitope sequence.

Assessing the significance of A11 epitope change.

We used two approaches in an attempt to assess the significance of A11 epitope change in the context of overall EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C sequence divergence.

(i) Incidence of sequence changes affecting unrelated CD8+-T-cell epitopes.

Following the approach used by Khanna et al. (14), we investigated how frequently sequence changes in type 1 virus strains coincidentally affected any of the other known CD8+-T-cell epitopes with EBNA3A, 3B, or 3C. Table 4 lists all CD8+-T-cell epitopes currently known within the Caucasian prototype 1 EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C sequences (3, 24) and records whether or not these sequences are coincidentally altered in Chinese type 1 viruses. Note that a large majority of these epitopes are restricted through HLA alleles that are poorly represented in the Chinese population, and in any case, most of them elicit responses that are much weaker than those induced by IVT and AVF. We therefore assume that mutations occurring in these epitopes probably reflect the coincidental effects of random genetic drift during EBV evolution.

TABLE 4.

Conservation or variation of known CTL epitopes in Chinese EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C

| Gene | Codons | B95.8 epitope sequencea | Restricting HLA class I allele(s) | Conservation or variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBNA3A | 95-102 | RRFPLDLR | B27.05 | Conserved in NPC15 |

| 158-166 | QAKWRLQTL | B8 | Conserved in 26/26 isolates | |

| 176-184 | AYSSWMYSY | A30 | Conserved in 26/26 isolates | |

| 246-253 | RYSIFFDY | A24 | Variant in 1/26 isolates (S3→R3) | |

| 325-333 | FLRGRAYGL | B8 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 378-386 | KRPPIFIRR | B27.05 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 379-387 | RPPIFIRRL | B7 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 386-395 | RRLHRLLLMR | B27.05 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 450-458 | HLAAQGMAY | ? | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 458-466 | YPLHEQHGM | B35 | Variant in NPC15 (H7→R7) | |

| 491-499 | VSSDGRVAC | A29 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 502-510 | VPAPAGPIV | B7 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 596-604 | SVRDRLARL | A2 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 603-611 | RLRAEAQVK | A3 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 617-625 | VQPPQLTQV | ? B46 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| EBNA3B | 154-157 | HRCQAIRKK | B27.05 | Conserved in 26/26 isolates |

| 217-225 | TYSAGIVQI | A24 | Variant in 5/26 isolates (I9→L9) | |

| 244-254 | RRARSLSAERY | B27.02 | Conserved in 26/26 isolates | |

| 279-287 | VSFIEFVGW | B58 | Conserved in 26/26 isolates | |

| 399-408 | AVFDRKSDAK | A11 | Variant in 24/26 isolates (multiple) | |

| 416-424 | IVTDFSVIK | A11 | Variant in 25/26 isolates (multiple) | |

| 488-496 | AVLLHEESM | B35 | Variant in 25/26 isolates (A1→T1) | |

| 657-666 | VEITPYKPTW | B44 | Variant in 10/26 isolates (3 patterns) | |

| EBNA3C | 163-171 | EGGVGWRHW | B44 | Conserved in 26/26 isolates |

| 249-258 | LRGKWQRRYR | B27.05 | Variant in 1/26 isolates (Y9→F9) | |

| 258-266 | RRIYDLIEL | B27.02, 04.05 | Conserved in 26/26 isolates | |

| 281-290 | EENLLDFVRF | B44 | Conserved in 26/26 isolates | |

| 285-293 | LLDFVRFMGV | A2 | Conserved in 26/26 isolates | |

| 286-293 | LDFVRFMGV | B37 | Conserved in 26/26 isolates | |

| 335-343 | KEHVIQNAF | B44 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 343-351 | FRKAQIQGL | B27.05 | Conserved in NPC15 | |

| 881-891 | QPRAPIRDIPT | B7 | Conserved in NPC15 |

Epitopes were taken from references 3 and 24. Note that the FLRGRAYGL (EBNA3A codons 325 to 333) sequence shown is that found in all Caucasian type 1 strains with the single exception of B95.8. Boldface type identifies those epitopes sequenced in all 26 Chinese type 1 strains.

As shown in Table 4, the region of EBNA3A sequenced in all 26 viruses contains three known epitopes; two of these (QAK/B8 and AYS/A30) were conserved in every isolate and one (RYS/A24) was altered in a single isolate. Of another 12 epitopes situated elsewhere in EBNA3A, only one (YPL/B35) was altered in the Chinese prototype 1 virus NPC15 relative to Caucasian epitope sequences. Likewise, the region of EBNA3C sequenced in all 26 viruses contained six epitopes (three overlapping), of which five epitopes are conserved in all Chinese type 1 strains and one epitope is mutated in a single isolate; another three known epitopes situated elsewhere in EBNA3C were all conserved in the NPC15 sequence. The complete EBNA3B gene, which was sequenced in all 26 viruses, contains six known epitopes other than IVT and AVF. Of these six epitopes, three were conserved in every case, one (TYS/A24) showed a conservative Ile→Leu change in just a subset of Wu family viruses, another (VEI/B44) was altered in Wu family viruses and in Wu/Sp recombinants but not in anchor positions for HLA class I binding, and a third (AVL/B35) showed the same sequence change (Ala→Thr position 1) in essentially every isolate. This latter epitope change is an example of a geographic marker shared by virtually all Chinese and Papua New Guinea virus strains and is already known not to alter epitope antigenicity (14). Taken overall, these results stand in contrast to the situation at the IVT and AVF epitopes in EBNA3B, which are mutated in a large majority of type 1 Chinese strains, including the Li family, Wu family, and Wu/Sp recombinants, which exhibit a variety of different mutations, and where these mutations regularly affect immunogenicity (21).

(ii) Evaluation of positively selected sites by computer-based modeling.

We then used a computer-based modeling approach to look for evidence of sites within EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C with patterns of sequence change indicative of positive selection. A concatenated alignment of the EBNA3 gene coding sequences for 21 Chinese isolates was constructed for analysis with Codeml. These included 19 type 1 and 2 type 2 virus strains (duplicate entries of identical sequence and type 1/type 2 recombinants were excluded) that were each analyzed across 1,326 codons representing 207 codons of EBNA3A, all 946 codons of EBNA3B (inclusive of alignment gapping but omitting the stop codon), and 173 codons of EBNA3C. Maximum-likelihood distances were calculated for all pairs of sequences (with PHYLIP Dnadist) and used to derive a neighbor-joining tree (with PHYLIP Neighbor) whose topology (unrooted) was supplied as input to Codeml.

A number of runs of Codeml were made to evaluate the existence and identity of positively selected sites, under a range of models for distribution of ω values across the codon set of the input alignment. Under Codeml model 1, only neutral or silent changes are allowed, whereas model 2 also allows positively selected changes. Models 1 and 2 yielded log likelihood values (for the data, given the model) of −8,904.35 and −8,850.29, respectively. By the criterion of the likelihood ratio test, these figures indicate that model 2 gave a highly significantly improved fit over model 1 and thus that the sequence set contains positively selected elements. From the model 2 analysis, 12 codon sites were identified as exhibiting positive selection on the basis of having a probability of greater than 0.95 that ω is >1; the sites identified are listed in Table 5. In model 3, the number of classes for ω values is specified to the program, which then computes the ω value for each class. Model 3 identified expanded numbers of codon sites as showing positive selection, namely 34, 34, and 27 sites for runs with 2, 3, and 8 ω classes, respectively (data not shown). Finally Codeml model B was applied to examine combined site specificity and lineage specificity of positive selection, with the EBV type 1 branches of the input tree designated as the foreground locus of interest for analysis of lineage specificity. Model B gave a log likelihood figure of −8,834.34 compared with a value for the comparable analysis that lacked the foreground-specific ω class (i.e., model 3 [discrete] with 2 ω classes) of −8,851.50, and the likelihood ratio test then showed that the addition of the foreground class of ω value represented a highly significant improved fit to the data. As shown in Table 5, model B identified five sites showing positive selection (P > 0.95 that ω is >1) specific to EBV type 1, two of which corresponded to codons 399 and 400 encoding amino acids 1 and 2 of the AVF epitope and a further two codons, 417 and 424, encoding amino acids 2 and 9 of the IVT epitope. Two other sites were identified by model B as representing positive selection not specific to the EBV type 1 branches; both refer to codons where all three nucleotides differed between type 1 and 2 sequences rather than to codons showing substantial diversification within viruses of the same type.

TABLE 5.

Codon sites in EBNA3 genes showing positive selection

| Codem1 program | EBV gene | Codon(s) subject to positive selection with P value ofa:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| >0.99 | >0.95 | ||

| Model 2 | EBNA3A (part) | 189T, 190T | |

| EBNA3B (all) | 399A, 400V, 417V | 212T, 424K, 461Q, 533R, 899G | |

| EBNA3C (part) | 141I | 162A | |

| Model B, EBV type 1 specific | EBNA3A (part) | ||

| EBNA3B (all) | 400V | 399A, 417V, 424K, 900Q | |

| EBNA3C (part) | |||

| Model B, general | EBNA3A (part) | 164Q | |

| EBNA3B (all) | 659I | ||

| EBNA3C (part) | |||

Codon sites within the EBNA3 gene sequences (EBNA3A, codons 114 to 320; EBNA3B, entire gene; EBNA3C, codons 121 to 293) of Chinese virus strains identified by model 2 and model B of Codem1 as subject to positive selection (P > 0.99 and P > 0.95); all sites listed have ω > 1. Codon numbers and amino acid residues are based on the B95.8 EBNA3 sequences. Sites shown in boldface type lie within IVT and AVF epitopes.

DISCUSSION

This work was prompted by continuing debate over the significance of IVT and AVF epitope variation among EBV strains in two highly HLA-A11-positive host populations from China and lowland Papua New Guinea. In an accompanying paper, our group confirmed the high incidence of such variation in Chinese EBV strains and showed that several variant epitope sequences did indeed appear to be nonimmunogenic in the context of natural EBV infection in vivo (21). The point at issue is whether such variants have been selected as a specific consequence of CTL-mediated immune pressure or are simply the result of random genetic drift (13). Since we cannot follow EBV evolution prospectively, the only available evidence comes from the study of contemporary virus strains and, as such, will always be circumstantial rather than definitive. The immediate aim of the present work was to provide a more comprehensive body of evidence than that which has fueled the debate so far. The initial studies of A11-epitope polymorphism in Chinese and lowland Papua New Guinea virus isolates restricted their sequencing efforts to the immediate epitope region of EBNA3B (6, 7), whereas subsequent work on viruses from these and other human populations (including populations with low frequencies of the HLA-A11 allele) focused on several short tracts of EBNA3A, 3B, or 3C sequence encompassing some of the then-known CD8+-T-cell epitopes restricted through various HLA alleles (2, 14). Here, we have sequenced the complete (approximately 2.8 kb) EBNA3B gene and selected (0.5 to 0.6 kb) regions of the EBNA3A and 3C genes in each of 31 Chinese EBV strains, of which 26 were type 1 viruses, 2 were type 2 viruses, and 3 were type 1/2 intertypic recombinants; in addition, we sequenced selected regions of the EBNA1 and 2 and LMP1 genes in a number of representatives from the above-described panel. This provides a much wider view of the genomic context of HLA-A11 epitope change.

Irrespective of the situation at HLA-A11 epitope loci, there is clearly a process of EBV sequence diversification which has occurred through random mutation and is reflected in the presence of several contemporary polymorphisms that serve as geographic markers of EBV identity (1, 4, 11, 18, 22, 23, 33). Their existence accords with the view that EBV has been evolving for many thousands of years within host populations that have remained geographically separate. Among Chinese virus strains studied to date, almost all of which have been type 1, the most frequently described geographic markers include a characteristic LMP1 sequence (here called the Ch′ allele) with a 30-bp deletion and numerous other changes relative to B95.8 (4, 11, 22, 23, 33) and a characteristic EBNA1 sequence with several codon changes in the C-terminal half of the molecule and referred to as the V allele, after the signature amino acid found at position 487 (11, 22). This diversification of the EBNA1 sequence among different human populations is particularly informative since it affords an example of evolution that is presumably independent of CD8+-T-cell-mediated immune pressure. Thus, the EBNA1 protein is protected from CD8+-T-cell recognition by the presence of a glycine-alanine repeat domain that prevents peptides being generated from the endogenously expressed protein by proteasomal digestion (16, 30).

It is therefore very likely that the EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C genes will also have accumulated sequence changes via random mutation that, as in EBNA1 and LMP1, have become embedded in contemporary Chinese strains as a result of earlier founder effects. Indeed, such signature mutations, which may or may not be reflected as amino acid changes, are likely to be in the majority and may serve to mask local examples of positive or negative selection if the analysis of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide change is conducted only at the level of a whole gene sequence. An interesting, but still unexplained, feature of the present results is that the EBNA3A, 3B, 3C, and 2 genes (Fig. 1 to 3) appear to display greater polymorphism among Chinese type 1 viruses as a group than is seen for the same viruses at the EBNA1 and LMP1 loci. Moreover, these polymorphisms at the EBNA3A, 3B, 3C, and 2 loci are linked and serve to identify separate families of type 1 Chinese viruses with characteristic combinations of alleles at all four loci. These familial relationships even appear to be reflected at the EBNA1 and LMP1 loci but only as a single nucleotide polymorphism within the V-allelic and Ch′-allelic sequences, respectively (Table 3). Genetic linkage between the EBNA3 gene loci and the EBNA2 locus some 40 kb upstream in the viral genome was first recognized as a feature of the type 1/type 2 division of EBV strains (29), but the present data provide the first clear evidence that this is also the case among EBV strains of the same type. It is possible that the coevolution of these loci reflects the fact that their protein products interact functionally during the virus-driven growth transformation of latently infected B cells, with both EBNA3A and 3C serving as regulators of EBNA2-induced gene activation through competitive inhibition of EBNA2's interaction with the cellular transcriptional regulator RBP-JK (12, 41).

Changes at the IVT and AVF epitope regions therefore need to be assessed against this background of slow evolutionary drift at the EBNA2, 3A, 3B and 3C gene loci. Indeed, the IVT and AVF mutations clearly do align with type 1 family divergence on a phylogenetic tree of Chinese EBV strains (Fig. 5). Thus, the Li family and the Wu family of isolates each display two family-specific patterns of epitope change, the Wu/Li recombinants display another pattern, and the more disperse Wu/Sp family displays four other patterns, three of them unique to that family. Of itself, this concordance between IVT/AVF sequence variation and other markers of type 1 virus diversification can be accommodated with either interpretation of epitope change (immune selection or neutral mutation). The question again becomes whether epitope change is anything other than a fortuitous marker of general diversification at the EBNA2, 3A, 3B, and 3C loci.

We examined the available evidence in two ways. The first was to pursue the approach of Khanna et al. (14) and look at the incidence with which random sequence change in the EBNA3 genes of Chinese viruses has coincidentally affected known CD8+-CTL epitope sequences other than the observed examples of epitope loss in the two A11 epitopes within EBNA3B. This type of analysis can now be conducted more systematically since we have much more sequence information from Chinese viruses and an increasing number of defined CTL epitopes (3, 24) of varying strength and restricted through a variety of HLA alleles, most of which are relatively rare or absent in the Chinese population (Table 4). While conservation of an epitope sequence could in some instances reflect an absolute requirement for that sequence in order to maintain protein function, such constraints are unlikely to apply in every case. Thus, it was significant that of the 15 epitopes that lie within those EBNA3A, 3B, and 3C gene sequences available from all 26 Chinese type 1 isolates, only the AVL epitope in EBNA3B (restricted through an HLA allele, B35, not seen in Chinese populations) showed evidence of consistent divergence from the B95.8 prototype, and this reflects a single nucleotide change with all the hallmarks of a founder mutation, being present in virtually all Chinese and Papua New Guinea strains but absent from Caucasian or African viruses (14). Among the 15 other epitopes that lie in areas of EBNA3A and 3C for which only the Chinese prototype (NPC15) sequence was available, again only one (the YPL/B35 epitope in EBNA3A) was altered; coincidental mutations of this epitope have been observed before in Chinese virus strains (15), although their potential effects on antigenicity have not been fully investigated. Our data suggest that, within the limits of currently available sequence information and currently known epitopes in EBNA3 proteins, the focusing of multiple epitope-loss mutations as seen at the IVT and AVF epitopes in Chinese viruses is not replicated coincidentally at other epitope loci.

A second means of examining the significance of our results was to use computer-based modeling to analyze the available Chinese EBNA3 gene sequences for evidence of sites under positive selection. In a series of papers since 1994, Yang and colleagues have developed probabilistic methods for evaluating evolutionary change in sets of diverging protein coding sequences, building on a codon-based model of sequence evolution (10), with particular reference to detecting and analyzing instances of positive (or diversifying) selection. The strategy involves estimation of the overall rates of nonsynonymous change (dN) and synonymous change (dS) for the data and identifying situations where the dN/dS ratio (termed ω) is greater than 1. This is a general approach of superior power and resolution for evaluating the occurrence of positive selection compared to the commonly used device of counting synonymous and nonsynonymous differences between pairs of aligned sequences (35). The resulting program, Codeml, incorporates modeling capabilities that allow for multiple ω values across lineages (34, 36) or across sites in the alignment (26, 38) or in a specified subset of lineages (37).

Analysis of the EBNA3 gene diversity by Codeml under different models of ω distribution gave lists of sites identified as undergoing positive selection whose numbers ranged from a total of 7 with model B to 34 with model 3. This variability reflects the probabilistic nature of the modeling process and the limitations of each model, together with the arbitrary cutoff of a P value of >0.95 applied for inclusion in the lists. In regard to our major aim of investigating whether the HLA-A11 epitopes in EBNA3B have been subject to positive selection over the set of EBV type 1 sequences, we can summarize the findings as follows: (i) four variable sites in the two epitopes were scored as exhibiting positive selection in all analyses (with models 2, 3, and B); (ii) in the analysis with model 2, three of the epitope sites were in the high-scoring category of a P value of >0.99, while in the analyses with model 3, all four of these sites were in the P value of >0.99 class; and (iii) in the model B analysis, the epitope-associated sites comprised four of only five sites scored as exhibiting positive selection specifically in the EBV type 1 portion of the tree. Overall, these results indicate strongly that the epitope coding sites have been subject to positive selection.

Our study therefore sets the A11 epitope variants in their broader genomic context and shows that, while the epitope changes map coherently onto a phylogenetic tree of Chinese type 1 EBV strains, a number of their features are still difficult to explain as the result of mere chance. First, both epitopes show a number of different patterns of nonsynonymous coding change; second, all amino acid changes yet examined appear to render the epitopes nonimmunogenic; third, searching the Chinese virus sequences for other instances of coincidental epitope loss produced few parallels; and fourth, computer-based analysis identifies two codons within each of the two epitope coding regions as being subject to positive selection. These collective observations indeed strengthen the view that IVT and AVF epitope change in Chinese EBV strains could have arisen through immunological pressure. Perhaps the strongest additional support for an immune selection hypothesis would be now to find an independent example of just such a phenomenon. Efforts should therefore be made to find other situations, however rare, where the possibility of CTL-mediated immune pressure shaping herpesvirus evolution within a human population can be examined.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Cancer Research United Kingdom and by the award to R.S.M. of a Medical Research Council Clinical Research Fellowship.

We would like to thank the Functional Genomics Laboratory (supported by BBSRC grant 6/JIF13209) and the Glaxo Wellcome Biocomputing Laboratory (supported by MRC grant 4600017), School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, for help with DNA sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdel-Hamid, M., J. J. Chen, N. Constantine, M. Massoud, and N. Raab-Traub. 1992. EBV strain variation: geographical distribution and relation to disease state. Virology 190:168-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burrows, J. M., S. R. Burrows, L. M. Poulsen, T. B. Sculley, D. J. Moss, and R. Khanna. 1996. Unusually high frequency of Epstein-Barr virus genetic variants in Papua New Guinea that can escape cytotoxic T-cell recognition: implications for virus evolution. J. Virol. 70:2490-2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burrows, S. R., and A. D. Hislop. The immune response to Epstein-Barr virus. In A. C. Tselis and H. B. Jensen (ed.), The Epstein-Barr virus, in press. Marcell Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 4.Cheung, S.-T., S.-F. Leung, K.-W. Lo, K. W. Chiu, J. S. L. Tam, T. F. Fok, P. J. Johnson, J. C. K. Lee, and D. P. Huang. 1998. Specific latent membrane protein 1 gene sequences in type 1 and type 2 Epstein-Barr virus from nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Hong Kong. Int. J. Cancer 76:399-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dambaugh, T., K. Hennessy, L. Chamnankit, and E. Kieff. 1984. U2 region of Epstein-Barr virus DNA may encode Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7632-7636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Campos-Lima, P.-O., R. Gavioli, Q. J. Zhang, L. E. Wallace, R. Dolcetti, M. Rowe, A. B. Rickinson, and M. G. Masucci. 1993. HLA-A11 epitope loss isolates of Epstein-Barr virus from a highly A11+ population. Science 260:98-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Campos-Lima, P.-O., V. Levitsky, J. Brooks, S. P. Lee, L. F. Hu, A. B. Rickinson, and M. G. Masucci. 1994. T cell responses and virus evolution: loss of HLA A11-restricted CTL epitopes in Epstein-Barr virus isolates from high A11-positive populations by selective mutation of anchor residues. J. Exp. Med. 179:1297-1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felsenstein, J. 1989. PHYLIP-phylogeny inference package (version 3.2). Cladistics 5:164-166. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gavioli, R., M. G. Kurilla, P. O. de Campos-Lima, L. E. Wallace, R. Dolcetti, R. J. Murray, A. B. Rickinson, and M. G. Masucci. 1993. Multiple HLA A11-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes of different immunogenicities in the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen 4. J. Virol. 67:1572-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman, N., and Z. Yang. 1994. A codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 11:725-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutierrez, M. I., A. Raj, G. Spangler, A. Sharma, A. Hussain, J.-G. Judde, S. W. Tsao, P. W. Yuen, I. Joab, I. T. Magrath, and K. Bhatia. 1997. Sequence variations in EBNA1 may dictate restriction of tissue distribution of Epstein-Barr virus in normal and tumour cells. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1663-1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johannsen, E., C. L. Miller, S. R. Grossman, and E. Kieff. 1996. EBNA-2 and EBNA-3C extensively and mutually exclusively associate with RBPJκ in Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B lymphocytes. J. Virol. 70:4179-4183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna, R. 1998. Geographic (not immunological) constraints define long-term evolutionary dynamics of Epstein-Barr virus. EBV Rep. 5:127-131. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khanna, R., R. W. Slade, L. M. Poulsen, D. J. Moss, S. R. Burrows, J. Nicholls, and J. M. Burrows. 1997. Evolutionary dynamics of genetic variation in Epstein-Barr virus isolates of diverse geographical origins: evidence for immune pressure-independent genetic drift. J. Virol. 71:8340-8346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, S. P., S. Morgan, J. Skinner, W. A. Thomas, S. R. Jones, J. Sutton, R. Khanna, H. C. Whittle, and A. B. Rickinson. 1995. Epstein-Barr virus isolates with the major HLA B35.01-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope are prevalent in a highly B35.01-positive African population. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:102-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levitskaya, J., M. Coram, V. Levitsky, S. Imreh, P. M. Steigerwald-Mullen, G. Klein, M. G. Kurilla, and M. G. Masucci. 1995. Inhibition of antigen processing by the internal repeat region of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. Nature 375:685-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levitsky, V., Q. J. Zhang, J. Levitskaya, M. G. Kurilla, and M. G. Masucci. 1997. Natural variants of the immunodominant HLA A11-restricted CTL epitope of the EBV nuclear antigen-4 are nonimmunogenic due to intracellular dissociation from MHC class I:peptide complexes. J. Immunol. 159:5383-5390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lung, M. L., W. P. Lam, J. Sham, D. Chong, Y. S. Zong, H. Y. Guo, and M. H. Ng. 1991. Detection and prevalence of the “f” variant of Epstein-Barr virus in southern China. Virology 185:67-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGeoch, D. J., and A. J. Davison. 1999. The molecular evolutionary history of the herpesviruses, p. 441-465. In E. Domingo, R. Webster, and J. Holland (ed.), Origins and evolution of viruses. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 20.McGeoch, D. J., A. Dolan, and A. C. Ralph. 2000. Toward a comprehensive phylogeny for mammalian and avian herpesviruses. J. Virol. 74:10401-10406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Midgley, R. S., A. I. Bell, Q. Y. Yao, D. Croom-Carter, A. D. Hislop, B. M. Whitney, A. T. C. Chan, P. J. Johnson, and A. B. Rickinson. 2003. HLA-A11-restricted epitope polymorphism among Epstein-Barr virus strains in the highly HLA-A11-positive Chinese population: incidence and immunogenicity of variant epitope sequences. J. Virol. 77:11507-11516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Midgley, R. S., N. M. Blake, Q.-Y. Yao, D. S. G. Croom-Carter, S.-T. Cheung, S.-F. Leung, A. T. C. Chan, P. J. Johnson, D. Huang, A. B. Rickinson, and S. P. Lee. 2000. Novel intertypic recombinants of Epstein-Barr virus in the Chinese population. J. Virol. 74:1544-1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller, W. E., R. H. Edwards, D. M. Walling, and N. Raab-Traub. 1994. Sequence variation in the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. J. Gen. Virol. 75:2729-2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss, D. J., S. R. Burrows, S. L. Silins, I. Misko, and R. Khanna. 2001. The immunology of Epstein-Barr virus infection. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 356:475-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nalesnik, M. A. 1998. Clinical and pathological features of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD). Springer Sem. Immunopathol. 20:325-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen, R., and Z. Yang. 1998. Likelihood models for detecting positively selected amino acid sites and applications to the HIV-1 envelope gene. Genetics 148:929-936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pass, R. F. 2001. Cytomegalovirus, p. 2675-2705. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 28.Rickinson, A. B., and E. Kieff. 2001. Epstein-Barr virus, p. 2575-2627. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 29.Sample, J., L. Young, B. Martin, T. Chatman, E. Kieff, and A. Rickinson. 1990. Epstein-Barr virus types 1 and 2 differ in their EBNA-3A, EBNA-3B, and EBNA-3C genes. J. Virol. 64:4084-4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharipo, A., M. Imreh, A. Leonchiks, S. Imreh, and M. G. Masucci. 1998. A minimal glycine-alanine repeat prevents the interaction of ubiquitinated Iκβα with the proteasome: a new mechanism for selective inhibition of proteolysis. Nat. Med. 4:939-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shastri, N., S. Schwab, and T. Serwold. 2002. Producing nature's gene-chips: the generation of peptides for display by MHC class I molecules. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:463-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steven, N. M., A. M. Leese, N. Annels, S. Lee, and A. B. Rickinson. 1996. Epitope focusing in the primary cytotoxic T-cell response to Epstein-Barr virus and its relationship to T-cell memory. J. Exp. Med. 184:1801-1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sung, N. S., R. H. Edwards, F. Seillier-Moiseiwitsch, A. G. Perkins, Y. Zeng, and N. Raab-Traub. 1998. EBV strain variation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma from the endemic and non-endemic regions of China. Int. J. Cancer 76:207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang, Z. 1998. Likelihood ratio tests for detecting positive selection and application to primate lysozyme evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15:568-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang, Z., and J. P. Bielawski. 2000. Statistical methods for detecting molecular adaptation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15:496-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang, Z., and R. Nielsen. 1998. Synonymous and nonsynonymous rate variation in nuclear genes of mammals. J. Mol. Evol. 46:409-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang, Z., and R. Nielsen. 2002. Codon-substitution models for detecting molecular adaptation at individual sites along specific lineages. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19:908-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang, Z., R. Nielsen, N. Goldman, and A. M. Pedersen. 2000. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics 155:431-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao, Q. Y., R. J. Tierney, D. Croom-Carter, G. M. Cooper, C. J. Ellis, M. Rowe, and A. B. Rickinson. 1996. Isolation of intertypic recombinants of Epstein-Barr virus from T-cell-immunocompromised individuals. J. Virol. 70:4895-4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yewdell, J. W., and J. R. Bennink. 1999. Immunodominance in major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T lymphocyte responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:51-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao, B., D. R. Marshall, and C. E. Sample. 1995. A conserved domain of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigens 3A and 3C binds to a discrete domain of Jκ. J. Virol. 70:4228-4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]