Abstract

Biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus is usually associated with the production of the PNAG exopolysaccharide, synthesized by proteins encoded in the icaADBC operon. PNAG is a linear β-(1−6)-linked N-acetylglucosaminoglycan that has to be partially deacetylated and consequently positively charged, in order to be associated with bacterial cell surfaces. Here, we investigated whether attachment of PNAG to bacterial surface is mediated by ionic interactions with the negative charge of wall teichoic acids (WTAs), which represent the most abundant polyanions of the gram positive bacterial envelope. We generated WTAs deficient mutants by in frame deletion of the tagO gene in two genetically unrelated S. aureus strains. The ΔtagO mutants were more sensitive to high temperatures, showed a higher degree of cell aggregation, had reduced initial adherence to abiotic surfaces and also a reduced capacity to form biofilms in both steady state and flow conditions. However, the levels as well as the strength of the PNAG interaction with the bacterial cell surface were similar between ΔtagO mutants and their corresponding wild type strains. Furthermore, double ΔtagO-ΔicaADBC mutants displayed a similar aggregative phenotype as did single ΔtagO mutants, indicating that PNAG is not responsible for the aggregative behavior observed in ΔtagO mutants. Overall, the absence of WTAs in S. aureus had little effect on PNAG production or anchoring to the cell surface but did affect the biofilm forming capacity, cell aggregative behavior and the temperature sensitivity/stability of S. aureus.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, biofilm, tagO, teichoic acids, PNAG

Introduction

The gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus is a major worldwide cause of community acquired and nosocomial infections. S. aureus can cause a wide spectrum of diseases, ranging from superficial wound infections to life-threatening infections such as septicemia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis and toxic shock syndrome. In addition to acute diseases, S. aureus can also cause chronic infections, many of which are associated with the use of medical devices (Mack et al., 2004). This property is related to the capacity of S. aureus to adhere and form multilayered communities embedded in a self-produced matrix, termed biofilms, that survive on the surfaces of implanted devices (Gotz, 2002).

S. aureus biofilm formation is generally mediated by the production of the extracellular polysaccharide adhesin termed both polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) or poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG), whose synthesis depends on the expression of the biosynthetic enzymes encoded in the icaADBC operon (Cramton et al., 1999; Heilmann et al., 1996b; Mckenney et al., 1999). The exopolysaccharide PNAG is a linear β-(1−6)-linked N-acetylglucosaminoglycan with a high proportion of amino groups substituted with N-linked acetate, and a small amount of the hydroxyl groups esterified with acetate and succinate (Joyce et al., 2003; Mack et al., 1996; Maira-Litran et al., 2002). It has been recently shown that the IcaB protein is involved in the production of positive charge in the PNAG polymer by deacetylation of a proportion of the N-acetylglucosamines (GlcNAc). In the absence of IcaB, N-acetylated PNAG cannot be retained on the bacterial cell surface and is released to the liquid media, probably due to the loss of its cationic character (Cerca et al., 2007; Vuong et al., 2004). Accordingly, a S. epidermidis icaB mutant exhibits similar deficiencies in biofilm formation, immune evasion, adhesion to epithelial cells and virulence in an animal model of implant infection comparable to that of the PNAG deficient mutants (Vuong et al., 2004). Similar phenotypes in terms of biofilm formation and immune evasion, as well as a decreased ability to survive in the blood of infected mice, were found for an icaB-deletant of S. aureus (Cerca et al., 2007).

Among the cell wall associated components that could mediate ionic interactions with PNAG are the teichoic acids that represent the most abundant polyanions associated with the bacterial cell envelope. Teichoic acids (TAs) are composed of wall teichoic acids (WTAs) that are covalently linked to the peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acids (LTAs) that are membrane-anchored (for review see Neuhaus et al. (Neuhaus & Baddiley, 2003)). Both polymers are assembled via different pathways and have different chemical structures (Neuhaus & Baddiley, 2003; Ward, 1981). With the exception of some unusual strains, it is considered that WTAs in S. aureus are composed of ribitol phosphate repeating units while LTAs are polyglycerolphosphate chains (Endl et al., 1983; Vinogradov et al., 2006). Both polymers have a highly variable content of D-alanine ester substitutions that reduce the net negative charge of TAs by introduction of basic amino groups (Baddiley et al., 1961; Fischer, 1994; Neuhaus & Baddiley, 2003). The absence of D-alanine esters in dltA mutants of S. aureus causes a deficiency in the capacity to form biofilms on polystyrene or glass surfaces (Gross et al., 2001). This is likely due to the increased net negative charge on the bacterial surface causing electrostatic repulsions between the cell and the surfaces that consequently inhibit the initial steps of the biofilm formation process. Teichoic acids have been shown to facilitate adherence of S. aureus to host tissues. For example, Aly et al. (Aly et al., 1980) showed that treating human nasal epithelial cells with TAs extracted from S. aureus significantly decreased the binding of the bacteria to the epithelial cells. More recently, the importance of WTAs for the bacterial interaction with human nasal epithelial cells as well as endothelial cells was demonstrated using a rat nasal colonization and a rabbit endocarditis model, respectively (Weidenmaier et al., 2004; Weidenmaier et al., 2005). However, the precise function of TAs within the wall matrix remains speculative.

As the net charge of both WTAs and PNAG polymers seems to be important for their functionality, we hypothesized that attachment of PNAG to the bacterial cell surface could be mediated by ionic interactions between the positively-charged free amino groups on partially deacetylated PNAG and the negative charge of WTAs. In favor of this hypothesis, it has been shown that TAs can complex with different polysaccharides in a relatively non-specific way (Doyle et al., 1975). In addition, TAs are usually found as contaminants in PNAG purification processes, although no covalent linkage between them has been found (Joyce et al., 2003; Maira-Litran et al., 2002; McKenney et al., 1998).

In this study, we generated mutants deficient in WTA synthesis in two genetically independent S. aureus strains and studied the influence of the mutations on PNAG production, localization and biofilm formation. Our mutants showed an increased cell-to-cell aggregation and a defect in biofilm formation though the levels, location and strength of PNAG attachment were similar to that of the wild type strains. These findings indicate that WTAs are dispensable for the association of PNAG with the bacterial cell surface.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli XL1-Blue cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar (Pronadisa, Spain). Staphylococcal strains were cultured on Trypticase soy agar (TSA) or in Trypticase soy broth (TSB) supplemented with 0.25% glucose (TSB-gluc). Media were supplemented with appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations: erythromycin at 1.5 μg ml−1; ampicillin at 100 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol at 20 μg ml−1. In order to compare growth kinetics, overnight cultures of the test strains were diluted (1:200) in TSB-gluc and incubated with shaking at 37°C while optical density at 650 nm (OD650nm) was regularly monitored.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains and plasmids | Relevant characteristics. | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | ||

| 15981 | Clinical strain. Biofilm positive | (Valle et al., 2003) |

| 15981 ΔtagO | 15981 with deletion of the tagO gene | This study |

| 15981 ΔtagO-c | 15981 ΔtagO complemented with tagO gene | This study |

| 15981 ΔtagO pCU1 | 15981 ΔtagO carrying pCU1 plasmid | This study |

| 15981 ΔicaB | 15981 with deletion of the icaB gene | This study |

| 15981 Δica | 15981 with deletion of the icaADBC operon | (Toledo-Arana et al., 2005) |

| 10833 | Clumping factor-positive variant of Newman D2C | (Cramton et al., 1999) |

| 10833 ΔtagO | 10833 with deletion of the tagO gene | This study |

| 10833 ΔtagO-c | 10833 ΔtagO complemented with tagO gene | This study |

| 10833 ΔtagO pCU1 | 10833 ΔtagO carrying pCU1 plasmid | This study |

| 10833 Δica::tet | 10833 Δica::tet | (Jefferson et al., 2003) |

| 10833 Δica::tet ΔtagO | 10833 Δica::tet with deletion of the tagO gene | This study |

| 10833 Δica::tet ΔtagO-c | 10833 Δica::tet ΔtagO complemented with tagO gene | This study |

| 10833 Δica::tet ΔtagO pCU1 | 10833 Δica::tet ΔtagO carrying pCU1 plasmid | This study |

| RN4220 | A mutant of 8325−4 S. aureus strain that accepts foreign DNA | (Novick, 1990) |

| E. coli | ||

| XL1Blue | Used for cloning assays | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMAD | E. coli- S. aureus shuttle vector with a termosensitive origin of replication for Gram-positive bacteria | (Arnaud et al., 2004) |

| pCU1 | Vector for complementation experiments. | (Augustin et al., 1992) |

DNA manipulations

DNA plasmids were isolated from E. coli using the Bio-Rad plasmid miniprep kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Plasmids were transformed into staphylococci by electroporation, using a previously described protocol (Cucarella et al., 2001). Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs and used according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA polymerase was purchased from Biotools. Oligonucleotides were obtained from Thermo Electron Corporation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| icaB-A | GGCTGGACTCATATTTG |

| icaB-B | AAGCTTGATCAAGATACTCAACAC |

| icaB-C | AAGCTTAGTCACTCCGAACTCC |

| icaB-D | ACTGTTGAATAGGTTATAG |

| icaB-E | GAAGTATTACTACGAGAC |

| icaB-F | ACGTTCGTAGTTATAACC |

| tagO-A | GGATCCCAATTACTGTGGCAGATAATG |

| tagO-B | GTCGACTCACCTTCATCGATATTAATTG |

| tagO-C | GCGTCGACGTATCGCCACCATTAGGTG |

| tagO-D | CGATGTTCATAATGCGTGTG |

| tagO-E | GTTACTGCAGCAATAACAATC |

| tagO-F | GTTCTGCATATACTATTGGAC |

| tagO-1 | ACCACTAGCTATTGTAAGTG |

| tagO-2 | GGATCCCTATTCCTCTTTATGAGATGA |

Allelic exchange of chromosomal genes

To generate the deletion mutants ΔtagO and ΔicaB we amplified by PCR two fragments of 500 bp that flanked the left (primers A and B) and right sequences (primers C and D) of the two genes targeted for deletion (Table 2). The PCR products were purified and cloned separately in the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). Fragments were then fused by ligation into the shuttle plasmid pMAD and the resulting plasmids were transformed into S. aureus by electroporation. pMAD contains a temperature-sensitive origin of replication and an erythromycin resistance gene (Arnaud et al., 2004). Homologous recombination experiments were performed as previously described (Valle et al., 2003) but in the case of ΔtagO mutation, the final temperature of incubation of double cross-over mutants on agar plates was reduced from 44°C to 37°C. This change was introduced to avoid negative selection of mutants due to their susceptibility to high temperatures. Erythromycin-sensitive white colonies, which no longer contained the pMAD plasmid, were tested by PCR using primers E and F (Table 2).

The Δica deletion mutant was constructed as previously described (Toledo-Arana et al., 2005)

Complementation experiments

The tagO gene under the control of its own promoter was amplified by PCR from S. aureus 15981 and S. aureus 10833 with primers tagO-1 tagO-2 (Table 2). The PCR products were cloned into pCU1 (Augustin et al., 1992), and the resulting plasmid, pCU1tagO, was transformed by electroporation into ΔtagO mutants.

Biofilm formation and primary attachment assays

The biofilm formation assays in microtiter wells were performed as described previously (Heilmann et al., 1996a). Briefly, 5 μl of a culture of S. aureus grown overnight in TSB-glucose at 37°C were inoculated into the wells of microtiter plates containing 195 μl of TSB-gluc medium. Sterile 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates from the same manufacturer (Iwaki) were used throughout the study. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the plates were washed twice with 200 μl of H2O and stained with 200 μl of crystal violet for 5 min at room temperature. Then, the microtiter plates were rinsed again twice with H2O, dried in an inverted position, and photographed. At least three independent cultures were assayed for each experiment, and four replicates were used for each culture. In order to visualize the pellicle formed by ΔtagO mutants, biofilms were air-dried before staining.

For adherence assays in glass tubes, a single colony was transferred to 5 ml of TSB-gluc and incubated at 37°C in an orbital shaker (250 rpm) for 12 h.

To analyze the biofilm formation under flow conditions we used 60-ml microfermentors (Pasteur Institute's Laboratory of Fermentation) with a continuous flow of 40 ml h−1 of TSB-gluc and constant aeration with sterile compressed air (0.3 bar). Submerged Pyrex slides served as the growth substratum. 108 bacteria from an overnight culture grown in TSB-gluc of each strain were used to inoculate microfermentors that were then grown for 24 h at 37°C. Biofilm development was recorded with a Nikon Coolpix 950 digital camera. To quantify the biofilm formed, bacteria adherent to the Pyrex slides were resuspended in 20 ml of TSB-gluc medium. The optical density of the suspensions was then measured at 650 nm.

Biofilm inhibition and detachment assays with DNase I, Dispersin B and proteinase K were carried out as previously described (Kaplan et al., 2004b; Rice et al., 2007) except that, after treatments, biofilms were air-dried before staining.

Primary attachment assays were performed as follows: S. aureus strains were grown overnight in TSB-gluc, diluted 1:100 and incubated until mid-log exponential phase (OD650nm = 0.6). The cultures were then diluted to OD650nm = 0.1 and 200 μl were used to inoculate sterile 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates (Iwaki). After 1 h at 37°C the wells were gently rinsed at least five times with water, dried in an inverted position and stained with crystal violet. The wells were rinsed again, and the crystal violet solubilized in 200 μl of ethanol-acetone (80 : 20 v/v). The optical density at 595 nm (OD595nm) was determined using a microplate reader (Multiskan EX; Labsystems). Each assay was performed in triplicate and repeated three times.

Microscopy

Scanning Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy was performed on biofilms grown in microfermentors on thermanox slides (Nalgen Nunc International Co., Naperville, IL) fixed on the internal removable glass slides as described by Prigent-Combaret et al. (Prigent-Combaret et al., 2000) at the Laboratoire de Biologie Cellulaire et Microscopie Electronique, UFR Médecine, Tours, France.

Immunoelectron microscopy

The bacterial strains were grown overnight in TSB. A 1-ml volume of the cultures was centrifuged (15,000 × g for 5 min) and washed in sterile PBS. Electron microscopic grids (200-mesh, Formvar-carbon-coated copper grids; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Washington, Pa.) were placed on top of a 10 μl drop of the bacterial suspension for 10 min. The grids were removed and placed on top of a drop 10 μl of 1% BSA and 10% Guinea Pig serum in PBS (blocking buffer) for 30 min. After blocking, the grids were placed on a 10 μl drop of immune rabbit antiserum raised to deacetylated PNAG conjugated to diphtheria toxoid (diluted 1:25 in 1% BSA in PBS) for 45 min (Maira-Litran et al., 2005). Then, the grids were washed three times for 2 min with PBS. The secondary antibody was then applied for 30 min. For all the strains, the secondary antibody used was a 10 μl drop of 12 nm colloidal gold-labeled donkey-anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc., PA) at a 1:60 dilution in 1% BSA in PBS. Each grid was then washed three times for 2 min in PBS and then two times in deionized water. The grids were examined with a transmission electron microscope (Philips Tecnai 12 electron microscope) and photographs were taken at magnifications of 11,000 ×.

Autolysis assays

Bacteria were grown in TSB-gluc to an OD650nm of approximately 0.6. Then, cells were collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 4°C, 10 min), washed once with cold water and resuspended in the same volume of phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (pH 7.5) containing 0.05 % Triton X-100 (vol/vol) (USB corporation). Autolysis was measured during incubation with shaking at 37°C as a decrease in the OD650nm. The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Zymographic analysis

For the detection of cell-associated murein hydrolases, SDS-PAGE zymographic analysis was performed as previously described (Ingavale et al., 2003). In brief, equal numbers for each strain, grown to mid-log exponential phase, were centrifuged, washed and resuspended in SDS-gel loading buffer, heated for 3 min at 100°C and centrifuged to obtain supernatants. Supernatants were separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel containing Micrococcus luteus or S. aureus RN4220 cells (1 mg wet weight of heat-killed cells per ml of gel). After electrophoresis, gels were washed with water and incubated for 12−16 h in 25 mM Tris-HCL (pH 8.0) containing 1% Triton X-100 at 37°C. Gels were stained with 1% methylene blue, and clear zones of hydrolysis were observed against a dark background.

PNAG detection

Surface located PNAG was detected as described previously (Cramton et al., 1999). Cells were grown overnight in TSB-gluc, the optical density was determined and the same number of cells of each culture was resuspended in 50 μl of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0), H2O, NaCl 0.8 M, NaCl 1 M or urea 4 M when indicated. Then, cells were incubated for 5 min at 100°C unless indicated and centrifuged to pellet. 40 μl of each supernatant were incubated with 10 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml; Sigma) for 30 min at 37°C. After addition of 10 μl of Tris-buffered saline (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.4]) containing 0.01% bromophenol blue, 5 μl of 1/50, 1/75 and 1/100 dilutions were spotted on a nitrocellulose filter using a Bio-Dot Microfiltration Apparatus (Bio-Rad), blocked overnight with 5% skim milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated for two hours with rabbit antibodies raised to S. aureus deacetylated PNAG conjugated to diphtheria toxoid diluted 1:10,000 (Maira-Litran et al., 2005). Bound antibodies were detected with peroxidase-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., PA) diluted 1:10,000 and the Amersham ECL Western blotting system.

Far-Dot-blot analysis

Staphylococcal peptidoglycan (PG) was isolated as previously described by Herbert et al. (Herbert et al., 2007). Similar amounts of PG obtained from wild type strain 15981 and its ΔtagO mutant were resuspended in water and dilutions of the samples (1/5, 1/10, 1/50 and 1/100) were spotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Then, membranes were incubated with pure PNAG (5 μg/ml) extracted from S. aureus MN8m as previously described (Maira-Litran et al., 2005). PNAG association was detected with rabbit antiserum raised to deacetylated PNAG conjugated to diphtheria toxoid.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS program. A non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney U test) was used to assess significant differences in bacterial density between the wild-type and ΔtagO strains recovered from the glass spatula from the microfermentors. For analysis of primary attachment a one-way ANOVA test with Tukey's pairwise comparisons was used. Differences were considered statistically significant when P was < 0.05.

Results

Mutants in wall teichoic acids are sensitive to high temperatures and display increased autolysis rates

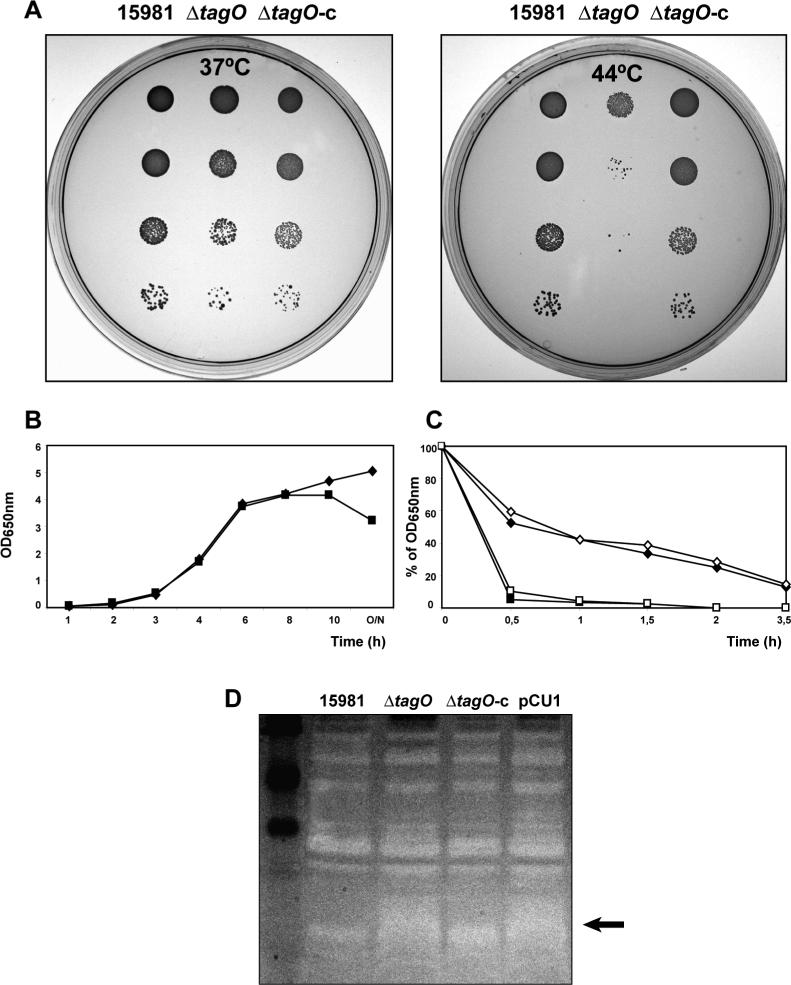

To investigate the role of wall teichoic acids in PNAG association with the cell surface, we constructed mutants in the tagO gene (ΔtagO), which encodes the first enzyme involved in the WTAs biosynthetic pathway, using markerless allelic exchange facilitated by the pMAD plasmid (Arnaud et al., 2004) in 15981 (strong biofilm former) and 10833 (weak biofilm former) S. aureus clinical isolates. To favor the selection of mutants that had lost the plasmid after the resolution of the second recombination event, we incubated the mutants at 44°C, a restrictive temperature, preventing plasmid replication. After several failed trials, in which we were unable to obtain ΔtagO mutants, we hypothesized that deletion of tagO gene might cause an increased sensitivity to high temperatures. To test this hypothesis, we repeated the double recombination process without the subsequent incubation step at 44°C. By this modified protocol many ΔtagO mutants were obtained in both strains, strongly suggesting that tagO deletion in S. aureus caused an inability to grow at 44°C. This observation was confirmed when we analyzed the growth of ΔtagO mutants on agar plates at 37°C and 44°C. The ΔtagO mutants had a seriously compromised capacity for growth at 44°C. The temperature sensitivity of ΔtagO mutants was lost when they were complemented with pCU1 plasmid carrying a PCR amplified 1349 bp fragment containing the tagO gene under the control of its own promoter (Fig. 1A). The absence of WTAs in ΔtagO mutants and its presence in the complemented mutants was confirmed by subjecting wall teichoic acid extracts to gel electrophoresis and combined alcian blue and silver staining (data not shown).

Figure 1. The absence of WTAs in S. aureus impairs growth under high temperatures and induces autolysis.

A) Effect of high temperatures on growth. S. aureus 15981, 15981 ΔtagO and complemented mutant 15981 ΔtagO-c, were grown exponentially in TSB-gluc at 37°C to an OD650nm of 0.2. The cultures were then serially diluted (10−1, 10−2, 10−3, and 10−4 fold) and 10 μl of each dilution were spotted onto TSA plates. The plates were then incubated at 37°C or 44°C overnight. B) Growth curve of the wild type strain 15981 (◆) and ΔtagO mutant (■). C) Triton X-100 induced autolysis assay. The autolysis of mid-exponential phase cultures of wild type strain 15981 (◆), 15981 ΔtagO mutant (■), complemented mutant 15981 ΔtagO-c (◇) and control strain 15981 ΔtagO carrying pCU1 plasmid (□) was determined at 37°C in the presence of 0.05 % Triton X-100, by measuring the decrease in the optical density at 650 nm upon exposure to the detergent. D) Zymogram analysis. Cell extracts were applied to a SDS polyacrylamide gel containing S. aureus RN4220 cells and stained with 1% methylene blue. Areas of murein hydrolase activity are indicated by clear zones. Lane 1, molecular size marker; lane 2, parental strain 15981; lane 3, ΔtagO mutant; lane 4, complemented mutant ΔtagO-c and lane 5, control ΔtagO strain carrying pCU1 plasmid. The arrow highlights the zone of major differences.

To study the effect of tagO deletion on bacterial growth, we compared the growth curves of ΔtagO and wild type strains at 37°C in rich media. The results showed that ΔtagO mutants exhibited growth rates similar to that of wild type strains. However, the turbidity of the cultures began to decrease in ΔtagO deletants during prolonged incubation in stationary phase (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the absence of WTAs could induce spontaneous autolysis. To test this hypothesis, we monitored bacterial cell lysis in the presence of triton X-100. As shown in Fig. 1C, the ΔtagO strains showed increased autolysis compared to wild type strains and complemented mutants. In order to study whether the increased autolysis rate of ΔtagO mutants was consequence of a higher content of cell wall murein hydrolases, we compared the autolysins pattern of wild type and ΔtagO strains in a zymogram gel. The zymograms revealed that the cell lysate of the ΔtagO mutant displayed zones of increasing clearance corresponding to areas of increased murein hydrolytic activity (Fig. 1D). Taking together, these results indicate that the absence of wall teichoic acids increases the sensitivity of S. aureus to high temperatures and the autolysis rate, which must be at least partially attributable to a higher murein hydrolase activity.

Multicellular behavior of Δ tagO strains

As bacterial surface components play an important role in cell-to-cell interactions and adherence to surfaces, we analyzed the effect of the absence of WTAs in forming multicellular structures by analyzing three different phenotypes: production of a ring of cells adherent to the glass wall at the air-liquid interface and biofilm formation in both static microtiter plates and under continuous flow conditions in microfermentors.

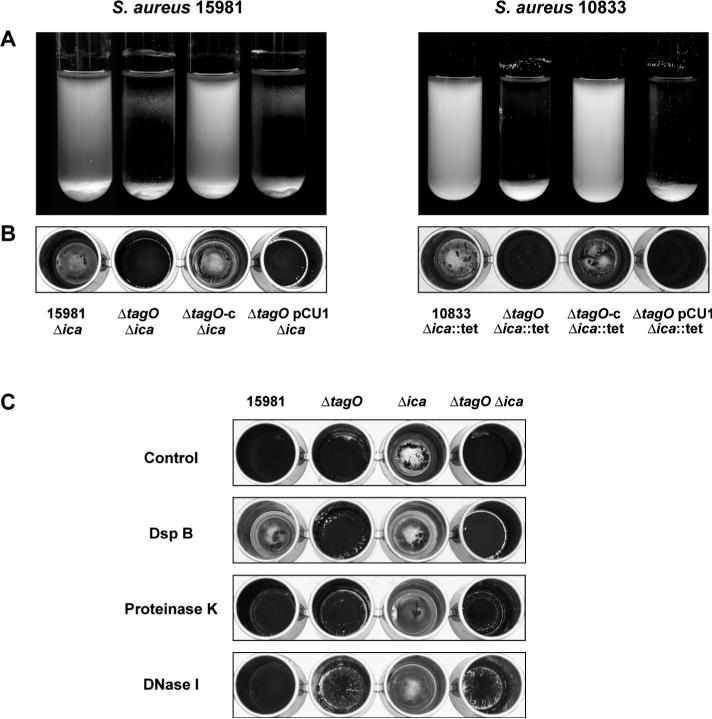

The ΔtagO strains retained the capacity to produce a ring of cells adherent to the glass wall when growing overnight in liquid medium under shaking conditions. However, the majority of the cells of ΔtagO mutants precipitated and settled at the bottom of the tubes (Fig. 2A). This phenotype was related to the absence of WTAs because the complemented strains exhibited a much greater turbidity throughout the culture tube. We also noted that when the parental strains were grown to stationary phase they also formed aggregates in the tubes (Fig. 2A) but these aggregates were very stable to vortexing as opposed to those formed by the ΔtagO strains, which were readily dispersed by mild vortexing.

Figure 2. Biofilm formation and aggregative phenotype of two genetically unrelated S. aureus strains and their respective ΔtagO mutants.

A) Biofilm forming capacity on glass surfaces of overnight cultures incubated in TSB-gluc medium, with shaking, at 37°C of S. aureus wild type strains 15981 (strong biofilm former) and 10833 (weak biofilm former), their isogenic ΔtagO mutants, the complemented ΔtagO mutants and the control ΔtagO strains carrying empty pCU1 plasmid. B) Biofilm forming capacity on microtiter plates after 24 h of static incubation at 37°C in TSB-gluc medium. C) Biofilm formation on microtiter plates after 24 h of static incubation at 37°C in TSB-gluc medium. The pellicle formed on the bottom of the plates were air-dried before staining. D) Comparison of the primary attachment ability of S. aureus 15981, its ΔtagO mutant, the complemented mutant and the control ΔtagO strain carrying pCU1 plasmid. Data represent the means of at least 9 counts from three independent experiments. The vertical line at the top of the each bar represents the standard deviation. Very significant differences were detected between wild-type strain and ΔtagO mutant (ns, not significant versus wild type; *** P < 0.001 versus wild type; one-way ANOVA test with Tukey's pairwise comparisons)

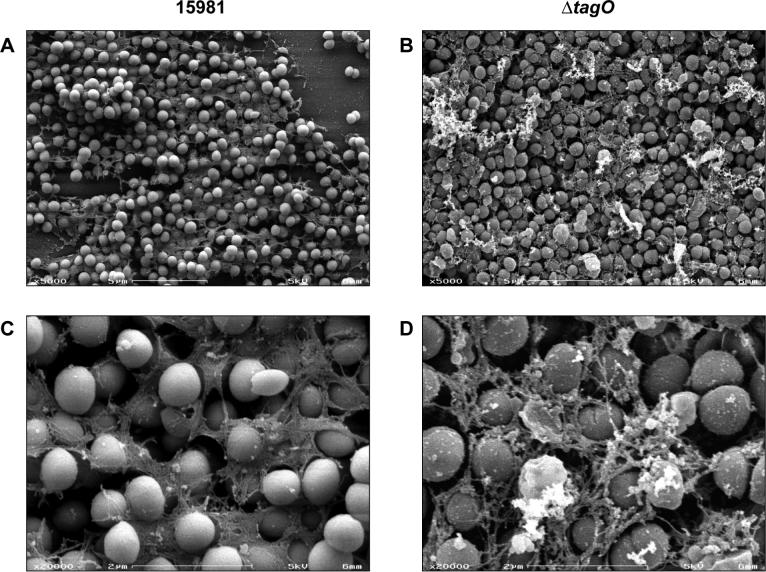

Analysis of the biofilm forming capacity of the bacterial strains in microtiter plate assays revealed that ΔtagO strains displayed a reduced capacity to produce biofilms compared to that of the parental strains (Fig. 2B). However, observation of the microtiter plates wells before washing revealed that ΔtagO strains were still able to form a pellicle loosely associated with the polystyrene surface that was easily removed when rinsed. The presence of this pellicle in ΔtagO strains was visualized both macroscopically after air-dry the microtiter plates before staining (Fig. 2C) and by observation of the biofilm with the scanning electron microscope (Fig. 3). The scanning electron micrographs revealed that wild type cells were interconnected by an extracellular matrix mesh (Fig. 3A, C). This mesh was more irregular containing numerous aggregates of material in the ΔtagO mutant. In agreement with the macroscopic aggregative phenotype of ΔtagO mutants in liquid media, scanning electron micrographs also revealed that ΔtagO mutant cells grew in highly dense bacterial aggregates with very little void spaces (Fig. 3B, D).

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscopy analysis of ΔtagO mutant.

Scanning electron microscopy images of S. aureus 15981 (A and C) and its ΔtagO mutant (B and D) at magnifications of × 5000 and × 20000.

The reduced ability of ΔtagO mutants to form polystyrene attached biofilms suggested that these strains could have a deficiency in the initial attachment to the polystyrene surface. To test this possibility, primary attachment experiments with static incubation periods of 60 min were carried out. The results indicated that ΔtagO mutants exhibit a reduced level of initial binding, indicating that the absence of WTAs affects the initial steps in the biofilm formation process (Fig. 2D).

Finally, analysis of the biofilm forming capacity of a ΔtagO mutant grown under continuous flow conditions in microfermentors showed that the biofilm biomass produced by the ΔtagO strain was significantly reduced in comparison to the parental strain and only a thin and weak layer of cells covered the surface of the slide (Fig. 4). Taking together, these results indicate that modifications in the physicochemical properties of the bacterial cell surface in the absence of WTAs provoke bacterial aggregation and reduce the capacity of bacteria to adhere to abiotic surfaces, thereby affecting the development of biofilms firmly attached to surfaces.

Figure 4. Biofilm formation of S. aureus 15981 and ΔtagO mutant under continuous flow conditions.

A) Biofilm development in microfermentors of wild type S. aureus strain 15981 and ΔtagO mutant grown under continuous-flow conditions with TSB-gluc after 24 h at 37°C. The microfermentors (upper panels) contain the glass slides where bacteria form the biofilm (lower panels). The results of a representative experiment are shown. B) Quantification of the biofilm mass adherent to the glass slides. The cells were removed from the glass slides into 20 ml of TSB-gluc by vortexing, and the OD of the resulting solutions was measured at 650 nm. Significant differences were detected between the wild-type and the ΔtagO mutant (n = 4; P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test)

Role of wall teichoic acids in PNAG localization

To investigate whether the reduced ability to form biofilms by ΔtagO mutants was due to an altered PNAG production, we monitored the levels of surface attached polysaccharide in overnight cultures of wild type and ΔtagO strains, by dot-blot analysis, using specific antibodies raised to deacetylated PNAG. The results showed that the levels of PNAG attached to the ΔtagO bacterial cell surface were only slightly reduced in comparison to those of the wild type strain. As internal control of the procedure, we used a Δica mutant that is unable to produce PNAG (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Dot-blot analysis of PNAG accumulation.

A) Dot-blot analysis of surface localized PNAG levels of S. aureus wild type strain 15981, its ΔtagO mutant, the complemented mutant and the control ΔtagO strain carrying the empty pCU1 plasmid. Cell surface extracts of overnight cultures were treated with proteinase K and dilutions of the samples (1/50, 1/75 and 1/100) were spotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. PNAG production was detected with rabbit antiserum raised to deacetylated PNAG conjugated to diphtheria toxoid. As negative controls, a Δica mutant unable to produce PNAG was used. B) Dot-blot analysis of PNAG cell surface levels of overnight cultures using different extraction conditions ranging from harsher to milder solvents (Urea 4M > NaCl 1M > NaCl 0.8M) and (EDTA, 100°C > EDTA, room temperature > water, 100°C > water, room temperature).

Next, we analyzed whether the absence of WTAs could affect the strength of PNAG interaction with the bacterial cell surface. To test this hypothesis, we compared the efficiency of different PNAG extraction conditions ranging from harsher to milder solvents (Urea 4M > NaCl 1M > NaCl 0.8M) and (EDTA, 100°C > EDTA, room temperature > water, 100°C > water, room temperature). No significant differences in the levels of extracted PNAG between the ΔtagO mutant and the wild type strain were detected with any of the extraction protocols (Fig. 5B). Quite the contrary, as we have observed before for overnight cultures, we continued detecting slightly reduced PNAG levels in ΔtagO mutant as compared to the parental strain. These results indicate that the strength of PNAG interaction with the bacterial cell surface in ΔtagO mutant is similar to that of the wild type strain, strongly suggesting that WTAs seem not to be implicated in the attachment of PNAG to bacterial cell surface.

We reasoned that the absence of WTAs could be compensated for by LTAs, the other type of teichoic acid, which also contribute to the negative charge of the bacterial cell surface. To investigate this possibility, we carried out a “Far-Dot-blot” experiment with purified peptidoglycan, partially deacetylated PNAG and anti-PNAG antibodies. The results revealed that purified PNAG binds with similar affinity to peptidoglycan of both wildtype or tagO mutant strains, suggesting that PNAG is able to interact with the bacterial cell wall in the absence of WTA and LTA (data not shown).

Finally, to confirm the presence of PNAG on the cell surface of the ΔtagO mutants, we studied by immunoelectron microscopy the localization of PNAG using specific polyclonal rabbit antiserum raised to deacetylated PNAG and gold labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG as secondary antibody. As shown in Fig. 6, PNAG was located on the bacterial cell surface in both wild type and ΔtagO strains, while it was absent from the surface of Δica mutant and mostly released to the supernatant in ΔicaB strain. In summary, these results indicate that PNAG interacts with the bacterial cell surface in the absence of wall teichoic acids.

Figure 6. Immunoelectron microscopy.

Immunoelectron microscopy images probed first with rabbit antiserum raised to deacetylated PNAG conjugated to diphtheria toxoid and then with gold-labeled donkey-anti-rabbit IgG. A-B) S. aureus 15981, C-D) S. aureus 15981 ΔtagO mutant, E) S. aureus 15981 Δica mutant and F) S. aureus 15981 ΔicaB mutant.

Aggregation phenotype of ΔtagO mutants is not dependent on PNAG

To investigate the possible role of PNAG in the aggregative phenotype observed in ΔtagO mutants, we constructed ΔtagO Δica double mutants. As shows Fig. 7A, B ΔtagO Δica double mutants displayed a similar aggregative phenotype as that of ΔtagO strains, indicating that this phenotype is independent of the presence of PNAG. In contrast to Δica strains, the double ΔtagO Δica mutants retained the capacity to produce both a ring of cells adherent to the glass wall (Fig.7A) and the loosely associated pellicle formed by ΔtagO mutants that was only visible when air-drying the microtiter plates before staining (Fig.7B). These results suggest that though PNAG is associated with the bacterial surface in ΔtagO mutants, the multicellular behavior of ΔtagO mutants seems to be not dependent on its presence.

Figure 7. Effect of ΔicaADBC deletion and biofilm detachment treatments.

A) Biofilm forming capacity on glass surfaces of overnight cultures incubated in TSB-gluc medium, with shaking, at 37°C of S. aureus Δica strains, their ΔtagO mutants and the double mutants carrying the plasmid pCU1 containing the tagO gene under the control of its own promoter or alone. B) Biofilm formation on microtiter plates after 24 h of static incubation at 37°C in TSB-gluc medium. The biofilms formed on the bottom of the plates were air-dried before staining. C) Susceptibility of ΔtagO biofilms to enzymatic treatments. Biofilms of 15981, ΔtagO, Δica and ΔtagO Δica strains were grown in TSB-gluc for 24 h and treated during 2 h at 37 °C with Dispersin B or proteinase K. DNase I was added at time of inoculation and biofilms were incubated in TSB-gluc for 24 h. The bacteria that remained attached to the surface were air-dried and stained with crystal violet.

In order to determine the nature of the matrix produced by ΔtagO mutants, pellicles produced on polystyrene microtiter plates were treated with proteinase K, Dispersin B, an enzyme of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (formerly Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans) that is able to hydrolyze β(1,6) glycosidic linkages (Kaplan et al., 2004a) and DNAse I. Neither treatment with proteinase K, nor Dispersin B produced any effect on the pellicles formed by ΔtagO and ΔtagO Δica mutants. Only incubation with DNase I slightly decreased pellicle formation. As expected, treatments with Dispersin B completely disrupted the PNAG dependent biofilm formed by wild type S. aureus strain 15981 (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that the aggregation observed in ΔtagO mutants seems to be independent of the production of PNAG, proteins or the relative amount of extracellular DNA present in the medium.

Discussion

Although multiple bacterial and external factors influence biofilm formation, production of an extracellular polysaccharide adhesin, termed here PNAG but also referred to as PIA, by biosynthetic enzymes encoded in the ica operon is currently the best understood molecular factor involved in biofilm formation by S. aureus. Many efforts have been made to understand how transcription of the ica locus and PNAG biosynthesis are regulated. In contrast, few studies have focused on how PNAG interacts with bacterial cell surfaces and remains in contact with them giving shape to the biofilm matrix.

In comparison to other known exopolysaccharides that are neutral, negatively charged or, on occasion, zwitterionic with both positive and negative charges (Cobb et al., 2004; Cobb & Kasper, 2005), PNAG represents a very unusual bacterial exopolysaccharide molecule, as some GlcNAc residues become deacetylated by the IcaB protein (Vuong et al., 2004), which provides a positive net charge to the polymer (Joyce et al., 2003). The deacetylation process, and therefore the cationic character of PNAG, has been shown to be crucial for the attachment of PNAG to the negatively charged bacterial surface and the biofilm formation process in both S. epidermidis (Vuong et al., 2004) and S. aureus (Cerca et al., 2007).

WTA polymers are major contributors to the negative charge of the bacterial cell wall and consequently, were good candidates for anchoring PNAG exopolysaccharide through ionic interactions. However, using WTA-deficient ΔtagO mutants we present evidence that WTAs are not the molecules implicated in the attachment of PNAG exopolysaccharide to the S. aureus cell surface. In the absence of WTAs, both the levels of PNAG on the bacterial surface and the strength of interaction between PNAG and the bacterial cell surface are similar to that of the wild type strain. The simplest explanation for these results is that WTAs are not required for anchoring PNAG. Alternatively, it is possible that the absence of WTAs could be compensated for by another cell surface compound, such as LTAs. Due to the impossibility of generating LTA deficient mutants because LTAs are essential for S. aureus viability (Grundling & Schneewind, 2007), we decided to evaluate this possibility by analyzing the capacity of purified PNAG to interact with purified peptidoglycan. The results showed that PNAG was able to bind to peptidoglycan of both wildtype and tagO mutant strains in vitro, suggesting that LTAs are either essential for the attachment of PNAG to the bacterial cell surface. Another alternative candidate for anchoring PNAG could be any of the numerous surface proteins linked to the peptidoglycan. Against this possibility, we have observed that sortase A mutants of S. aureus, which lack the family of LPXTG anchored proteins, contained identical levels of surface PNAG as did wild type S. aureus strains and retained the capacity to form biofilms on microtiter polystyrene plates, strongly suggesting that LPXTG proteins are also dispensable for PNAG binding to S. aureus cell surface (our unpublished results).

In this work we also have analyzed the impact that the ΔtagO mutation exerts on the biofilm formation process of S. aureus. Our data showed that depletion of WTAs significantly reduced the in vitro capacity of S. aureus to form biofilms under both steady state and flow conditions, while promoted cell to cell interactions making cells aggregate and sediment. The reduced biofilm forming capacity of ΔtagO mutants could be due to a decreased capacity of the mutants to establish initial interactions with the polystyrene or glass surfaces. In fact, primary attachment experiments showed that ΔtagO mutants exhibit a reduced capacity in the initial binding to polystyrene plates in comparison to wild type strains. This phenotype is in accordance with the less efficient capacity of adherence to human epithelial and endothelial cells observed in a ΔtagO mutant by Weidenmaier et al (Weidenmaier et al., 2004; Weidenmaier et al., 2005) and is consistent with that of dltA mutants lacking D-alanine esters in teichoic acids, which formed cell pellets unable to adhere to abiotic surfaces (Gross et al., 2001). The authors explained this phenotype by hypothesizing that the absence of D-alanine esters caused a stronger negative charge on the bacterial cell surface that led to a pronounced increase in the repulsive forces and therefore, in an inhibition of the interaction between bacteria and surfaces. However, a similar explanation can not be applied to ΔtagO mutants because WTA deficient bacteria should not display a strong negative charge on the cell surface, since cell wall phosphate content is vastly reduced in tagO mutants (D'Elia et al., 2006b; Weidenmaier et al., 2004).

The role of teichoic acids in cell aggregation had already been described for several bacterial isolates and had been related to the content of alanine ester groups as well as bound divalent metal cations, especially Ca2+ (Baddiley, 2000; Neuhaus & Baddiley, 2003). In fact, the increased tendency for cell aggregation of ΔtagO mutants has been reported in B. subtilis (D'Elia et al., 2006a; Soldo et al., 2002a) but not in S. aureus. The deficiencies in primary attachment to abiotic surfaces observed in the ΔtagO mutants could be a consequence of this aggregation, since ΔtagO mutant cells seem to prefer to interact between themselves rather than with artificial surfaces. Interestingly, this phenomenon of coaggregation seems to be independent of the presence of PNAG or proteins, since it also occurred in double ΔtagO Δica mutants and it is not affected by Dispersin B or proteinase K treatments. It seems that the alteration caused by the absence of WTAs in the bacterial cell wall enables new interactions between components of the cell wall that usually are not possible and in the absence of WTAs lead to the aggregative phenotype observed here.

The cell wall of gram-positive bacteria has been shown to be essential for the survival, shape and integrity of the cells. The lack of WTAs must have a strong impact on the structure of the bacterial cell envelope since WTAs make up a significant portion of the cell wall and it is likely, their absence results in a cell wall more sensitive to external conditions and environmental changes. This fact could explain the increased autolysis rate of the mutant as well as its inability to survive at temperatures of 44°C. The temperature sensitivity of teichoic acid deficient mutants had already been described for a mnaA mutant of B. subtilis, which lacks an enzyme involved in the synthesis of the linkage unit of TAs to the peptidoglycan, and consequently, had a reduced WTAs content (Soldo et al., 2002b). Increased autolysis due to tagO deficiency was also previously reported among tagO transposon insertion mutants of methicillin-resistant S. aureus clinical isolates (Maki et al., 1994). This higher degree of autolysis could be due to a lower content of D-alanyl esters. It is well known that the absence of D-alanyl esters from teichoic acids leads to increased sensitivity toward cationic antimicrobial peptides (Peschel et al., 1999) and, although the basis for this is not fully known, it is thought that the presence or absence of these esters within the cell wall matrix at specific locations might constitute a targeting mechanism for proteins, like autolysins, that require a specific ionic microenvironment for function (Neuhaus & Baddiley, 2003). Accordingly, zymographic analysis revealed enhanced murein hydrolase activity in the ΔtagO mutant as compared to the wild type strain. However, these results contradict those observed by Bera et al. (Bera et al., 2007) showing no increased endogenous autolysis activity in a S. aureus strain SA113 ΔtagO mutant, and suggest that a strain specific behavior might exist.

The presence of genes required for the synthesis of the PNAG-homologous exopolysaccharides in both gram positive and gram negative bacteria (Wang et al., 2004) suggests that the interaction between deacetylated PNAG and the negatively charge bacterial cell wall will be mediated by non-specific electrostatic interactions. WTAs and lipopolysaccharides are the two main contributors for the negative charge on bacterial cell surface. We have shown that WTAs are not required for PNAG anchoring but it remains to be determined whether LPS is also dispensable for PNAG localization on the bacterial surface.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Marta Vergara-Irigaray is a pre-doctoral fellow (FPU) from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Spain. Nekane Merino is a pre-doctoral fellow from the Basque Government, Spain. We express our gratitude to Dr. J. Kaplan for providing plasmid pRC3 for Dispersin B production. This work was supported by the BIO2005-08399 grant from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, LSHM-CT-2006-019064 and FP6-2003-LIFESCIHEALTH-I-512061 grants from the European Union and NIH grant AI-46706.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an author manuscript that has been accepted for publication in Microbiology, copyright Society for General Microbiology, but has not been copy-edited, formatted or proofed. Cite this article as appearing in Microbiology. This version of the manuscript may not be duplicated or reproduced, other than for personal use or within the rule of ‘Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials’ (section 17, Title 17, US Code), without permission from the copyright owner, Society for General Microbiology. The Society for General Microbiology disclaims any responsibility or liability for errors or omissions in this version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by any other parties. The final copy-edited, published article, which is the version of record, can be found at http://mic.sgmjournals.org, and is freely available without a subscription.

REFERENCES

- Aly R, Shinefield HR, Litz C, Maibach HI. Role of teichoic acid in the binding of Staphylococcus aureus to nasal epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1980;141:463–465. doi: 10.1093/infdis/141.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud M, Chastanet A, Débarbouillé M. A new vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally non transformable low GC% Gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6887–6891. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6887-6891.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin J, Rosenstein R, Wieland B, Schneider U, Schnell N, Engelke G, Entian KD, Gotz F. Genetic analysis of epidermin biosynthetic genes and epidermin-negative mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204:1149–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddiley J, Buchanan JG, Hardy FE, Martin RO, Rajbhandary UL, Sanderson AR. The structure of the ribitol teichoic acid of Staphylococcus aureus H. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1961;52:406–407. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)90699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddiley J. Teichoic acids in bacterial coaggregation. Microbiology. 2000;146(Pt 6):1257–1258. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-6-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera A, Biswas R, Herbert S, Kulauzovic E, Weidenmaier C, Peschel A, Gotz F. Influence of wall teichoic acid on lysozyme resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:280–283. doi: 10.1128/JB.01221-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerca N, Jefferson KK, Maira-Litran T, Pier DB, Kelly-Quintos C, Goldmann DA, Azeredo J, Pier GB. Molecular basis for preferential protective efficacy of antibodies directed to the poorly acetylated form of staphylococcal poly-N-acetyl-beta-(1−6)-glucosamine. Infect Immun. 2007;75:3406–3413. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00078-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb BA, Wang Q, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. Polysaccharide processing and presentation by the MHCII pathway. Cell. 2004;117:677–687. doi: 10.016/j.cell.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb BA, Kasper DL. Zwitterionic capsular polysaccharides: the new MHCII-dependent antigens. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1398–1403. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramton SE, Gerke C, Schnell NF, Nichols WW, Gotz F. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5427–5433. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5427-5433.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucarella C, Solano C, Valle J, Amorena B, Lasa II, Penades JR. Bap, a Staphylococcus aureus Surface Protein Involved in Biofilm Formation. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2888–2896. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.9.2888-2896.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Elia MA, Millar KE, Beveridge TJ, Brown ED. Wall teichoic acid polymers are dispensable for cell viability in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2006a;188:8313–8316. doi: 10.1128/JB.01336-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Elia MA, Pereira MP, Chung YS, Zhao W, Chau A, Kenney TJ, Sulavik MC, Black TA, Brown ED. Lesions in teichoic acid biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus lead to a lethal gain of function in the otherwise dispensable pathway. J Bacteriol. 2006b;188:4183–4189. doi: 10.1128/JB.00197-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle RJ, Chatterjee AN, Streips UN, Young FE. Soluble macromolecular complexes involving bacterial teichoic acids. J Bacteriol. 1975;124:341–347. doi: 10.1128/jb.124.1.341-347.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endl J, Seidl HP, Fiedler F, Schleifer KH. Chemical composition and structure of cell wall teichoic acids of staphylococci. Arch Microbiol. 1983;135:215–223. doi: 10.1007/BF00414483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W. Lipoteichoic acid and lipids in the membrane of Staphylococcus aureus. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1994;183:61–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00277157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz F. Staphylococcus and biofilms. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:1367–1378. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross M, Cramton SE, Gotz F, Peschel A. Key role of teichoic acid net charge in Staphylococcus aureus colonization of artificial surfaces. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3423–3426. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3423-3426.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundling A, Schneewind O. Synthesis of glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8478–8483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701821104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann C, Gerke C, Perdreau-Remington F, Gotz F. Characterization of Tn917 insertion mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis affected in biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 1996a;64:277–282. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.277-282.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann C, Schweitzer O, Gerke C, Vanittanakom N, Mack D, Gotz F. Molecular basis of intercellular adhesion in the biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis. Mol Microbiol. 1996b;20:1083–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert S, Bera A, Nerz C, Kraus D, Peschel A, Goerke C, Meehl M, Cheung A, Gotz F. Molecular basis of resistance to muramidase and cationic antimicrobial peptide activity of lysozyme in staphylococci. PLoS pathogens. 2007;3:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingavale SS, Van Wamel W, Cheung AL. Characterization of RAT, an autolysis regulator in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1451–1466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson KK, Cramton SE, Gö F, tz, Pier GB. Identification of a 5-nucleotide sequence that controls expression of the ica locus in Staphylococcus aureus and characterization of the DNA-binding properties of IcaR. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:889–899. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JG, Abeygunawardana C, Xu Q. Isolation, structural characterization, and immunological evaluation of a high-molecular-weight exopolysaccharide from Staphylococcus aureus. Carbohydr Res. 2003;338:903–922. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(03)00045-4. other authors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JB, Ragunath C, Velliyagounder K, Fine DH, Ramasubbu N. Enzymatic detachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004a;48:2633–2636. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2633-2636.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JB, Velliyagounder K, Ragunath C, Rohde H, Mack D, Knobloch JK, Ramasubbu N. Genes involved in the synthesis and degradation of matrix polysaccharide in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae biofilms. J Bacteriol. 2004b;186:8213–8220. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8213-8220.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack D, Fischer W, Krokotsch A, Leopold K, Hartmann R, Egge H, Laufs R. The intercellular adhesin involved in biofilm accumulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis is a linear beta-1,6-linked glucosaminoglycan: purification and structural analysis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:175–183. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.175-183.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack D, Becker P, Chatterjee I, Dobinsky S, Knobloch JK, Peters G, Rohde H, Herrmann M. Mechanisms of biofilm formation in Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus: functional molecules, regulatory circuits, and adaptive responses. Int J Med Microbiol. 2004;294:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maira-Litran T, Kropec A, Abeygunawardana C, Joyce J, Mark G, 3rd, Goldmann DA, Pier GB. Immunochemical properties of the staphylococcal poly-N-acetylglucosamine surface polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4433–4440. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4433-4440.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maira-Litran T, Kropec A, Goldmann DA, Pier GB. Comparative opsonic and protective activities of Staphylococcus aureus conjugate vaccines containing native or deacetylated Staphylococcal Poly-N-acetyl-beta-(1−6)-glucosamine. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6752–6762. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6752-6762.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki H, Yamaguchi T, Murakami K. Cloning and characterization of a gene affecting the methicillin resistance level and the autolysis rate in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4993–5000. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4993-5000.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenney D, Hubner J, Muller E, Wang Y, Goldmann DA, Pier GB. The ica locus of Staphylococcus epidermidis encodes production of the capsular polysaccharide/adhesin. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4711–4720. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4711-4720.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckenney D, Pouliot K, Wang V, Murthy V, Ulrich M, Döring G, Lee JC, Goldmann DA, Pier GB. Broadly protective vaccine for Staphylococcus aureus based on an in vivo-expressed antigen. Sciencie. 1999;284:1523–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus FC, Baddiley J. A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of D-alanyl-teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:686–723. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.686-723.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP. The Staphylococcus as a molecular genetic system. In: Novick RP, editor. Molecular biology of the Staphylococcus. VCH Publishers; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Peschel A, Otto M, Jack RW, Kalbacher H, Jung G, Gotz F. Inactivation of the dlt operon in Staphylococcus aureus confers sensitivity to defensins, protegrins, and other antimicrobial peptides. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8405–8410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigent-Combaret C, Prensier G, Le Thi TT, Vidal O, Lejeune P, Dorel C. Developmental pathway for biofilm formation in curli-producing Escherichia coli strains: role of flagella, curli and colanic acid. Environ Microbiol. 2000;2:450–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice KC, Mann EE, Endres JL, Weiss EC, Cassat JE, Smeltzer MS, Bayles KW. The cidA murein hydrolase regulator contributes to DNA release and biofilm development in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8113–8118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610226104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldo B, Lazarevic V, Karamata D. tagO is involved in the synthesis of all anionic cell-wall polymers in Bacillus subtilis 168. Microbiology. 2002a;148:2079–2087. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-7-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldo B, Lazarevic V, Pooley HM, Karamata D. Characterization of a Bacillus subtilis thermosensitive teichoic acid-deficient mutant: gene mnaA (yvyH) encodes the UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase. J Bacteriol. 2002b;184:4316–4320. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.15.4316-4320.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Arana A, Merino N, Vergara-Irigaray M, Debarbouille M, Penades JR, Lasa I. Staphylococcus aureus develops an alternative, ica-independent biofilm in the absence of the arlRS two-component system. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5318–5329. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5318-5329.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle J, Toledo-Arana A, Berasain C, Ghigo JM, Amorena B, Penades JR, Lasa I. SarA and not sigmaB is essential for biofilm development by Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1075–1087. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov E, Sadovskaya I, Li J, Jabbouri S. Structural elucidation of the extracellular and cell-wall teichoic acids of Staphylococcus aureus MN8m, a biofilm forming strain. Carbohydr Res. 2006;341:738–743. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong C, Kocianova S, Voyich JM, Yao Y, Fischer ER, DeLeo FR, Otto M. A crucial role for exopolysaccharide modification in bacterial biofilm formation, immune evasion, and virulence. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54881–54886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Preston JF, 3rd, Romeo T. The pgaABCD locus of Escherichia coli promotes the synthesis of a polysaccharide adhesin required for biofilm formation. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2724–2734. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2724-2734.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JB. Teichoic and teichuronic acids: biosynthesis, assembly, and location. Microbiol Rev. 1981;45:211–243. doi: 10.1128/mr.45.2.211-243.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidenmaier C, Kokai-Kun JF, Kristian SA. Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat Med. 2004;10:243–245. doi: 10.1038/nm991. other authors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidenmaier C, Peschel A, Xiong YQ, Kristian SA, Dietz K, Yeaman MR, Bayer AS. Lack of wall teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus leads to reduced interactions with endothelial cells and to attenuated virulence in a rabbit model of endocarditis. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1771–1777. doi: 10.1086/429692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]