Abstract

Previously, several studies have demonstrated changes in the levels of small heat shock proteins (sHSP) in the transgenic mouse models of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (fALS) linked to mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase. Here, we compared the expression of sHSPs in transgenic mouse models of fALS, Parkinson’s disease (PD), dentato-rubral pallido-luysian atrophy (DRPLA) and Huntington’s disease (HD); where the expression of mutant cDNA genes was under the transcriptional regulation of the mouse prion protein promoter. These models express G37R mutant Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1G37R; fALS), A53T mutant α-synuclein (α-SynA53T; PD), full-length mutant atrophin-1-65Q, and htt-N171-82Q (huntingtin N-terminal fragment; HD). We found that the levels and solubilities of two sHSPs, Hsp25 and αB-crystallin, were differentially regulated in these mice. Levels of both Hsp25 and αB-crystallin were markedly increased in subgroups of glias at the affected regions of symptomatic SODG37R and α-SynA53T transgenic mice; abnormal deposits or cells intensely positive for αB-crystallin were observed in SODG37R mice. By contrast, neither sHSP was induced in spinal cords of htt-N171-82Q or atrophin-1-65Q mice, which do not develop astrocytosis or major motor neuron abnormalities. Interestingly, the levels of insoluble αB-crystallin in spinal cords gradually increased as a function of age in nontransgenic animals. In vitro, αB-crystallin was capable of suppressing the aggregation of α-SynA53T, as previously described for a truncated mutant SOD1. The transgenes in these mice are expressed highly in astrocytes and thus our results suggest a role for small heat shock proteins in protecting activated glial cells such as astrocytes in neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: neurodegeneration, aging, Hsp25, αB-crystallin

1. Introduction

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) contribute to a repertoire of molecular chaperones that function to regulate the folding of cellular proteins. In certain physiologic settings, and under conditions of stress, the HSPs, which include HSP110, HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, HSP40, and the small HSP family, engage in a variety of functions to regulate protein folding. Small heat shock proteins (sHSPs) are a family of proteins with molecular mass ranging from 12 to 43 kDa, with the defining feature of the α-crystallin domain, which is highly conserved from prokaryotes to mammals [9]. Although implicated in diverse pathways, the physiological functions of sHSPs remain unclear. Unlike other catalytic chaperons, sHSPs lack ATPase domains but several members can stabilize unfolded proteins. Most sHSPs form multi-subunit oligomers in physiological conditions; the α-crystallin domain, a conserved β-sheet sandwich structure, can engage in an intersubunit composite β-sheet to form a dimer, a potential building block for higher-order structures [15].

Mammalian sHSPs comprise at least ten members; only Hsp25 (Hsp27 in human), αB-crystallin, and the recently identified HSPB8 are stress-inducible [38]. Hsp25 is induced during development and stressful conditions [7;31]; and has been reported to exhibit anti-apoptotic function through possible mechanisms including interfering with the caspase pathway [12;34], modulating oxidative stress [29], or regulating cytoskeleton [23]. αB-crystallin is a major structural protein in the vertebrate lens, but is also expressed in many other tissues, with suggested chaperon-like in vitro activities [16].

While the role of the sHSPs in the nervous tissue is not established, a variety of HSPs, including sHSPs, have been implicated in neurological disorders. Missense mutations in Hsp27 are linked to the sensory and motor neuropathies in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and distal hereditary motor neuropathies [10]. A mutation in αB-Crystallin is associated with desmin-related myopathy [40]. Induction of αB-Crystallin has been reported in Alexander’s disease [18], Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease [33], Alzheimer’s disease [26], and other neurological conditions [19]. Hsp25 and αB-crystallin have been reported to be induced in mouse models of SOD1-linked amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [41;43].

Transgenic mice expressing mutant SOD1, either in a human gene cassette with ubiquitous expression [6;14;43;47] or under the control of a more restrictive promoter, the mouse prion promoter (PrP) [45], recapitulate many features of motor neuron degeneration in human Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Transgenic mice expressing human α-synuclein (α-Syn) harboring the A53T mutation, under the control of the same prion promoter, recapitulate features of Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and other α-synucleinopathies [13;24]. Both the mutant SOD1 and α-Syn models develop motor deficits leading to paralysis, which are associated with motor neuron loss and ubiquitinated inclusions in the brain stem and the spinal cord. We have recently described up-regulation of two small heat shock proteins, Hsp25 and αB-crystallin, in the disease tissue of transgenic mice carrying the human genomic SOD1 gene (Gn.SOD1) [43], or the PrP.SOD1 cassette [45]. To explore the relationship between chaperone proteins and neurodegenerative diseases associated with abnormal protein aggregates, we have systematically investigated the regulation of a panel of chaperones in four transgenic mouse models of neurodegenerative disease that involve an accumulation of aggregated protein. The four models we study here, SOD1G37R [45], α-SynA53T [24], Atrophin-1-65Q [36] and htt-N171-82Q [35], express mutant genes via a vector derived from the mouse prion protein. Our study demonstrates that induction of Hsp25 and αB-Crystallin in spinal cords of PrP.SOD1-G37R and PrP.α-SynA53T mice correlates to the presence of astroglial responses and that both proteins are highly induced in glias rather than neurons. Neither of these sHSPs is induced in the spinal cords of either of the polyglutamine mouse models, which also lack evidence of astrocytic responses or degenerative changes in spinal cord. As previously demonstrated for mutant SOD1L126Z [44], αB-crystallin was found to inhibit the in vitro aggregation of α-SynA53T, suggesting that αB-crystallin may slow aggregation of mutant protein in glias. Robust increases in insoluble αB-crystallin were also noted as a function of age in non-transgenic animals, suggesting the aging process produces signals that modulate αB-crystallin. These findings provide evidence that the astroglial response and normal aging, in mice, is associated with the induction of inhibitors of protein aggregation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transgenic mice

Mice harboring fragments of the human genomic SOD1 gene encoding the G37R mutation, Gn.SOD1G37R (line 29) or the wild-type sequence (line 76) have been previously reported [47]. The SOD1 cDNA G37R transgenic mouse model (line 110) was recently reported [45], using the previously described PrP promoter vector [4]. PrP.α-synuclein (line G2-3 and O2), PrP.htt-N171-82Q (expressing a mutant N-terminal fragment of huntingtin; line 81) and PrP.AT65Q (expressing a full-length atrophin-1; line 150) mice were previously reported [24;35;36]. All the transgenic mice were generated by injecting DNA into mouse embryos [C3H/HeJ X C57BL/6J F2]. All lines were maintained by crossing transgenic males to non-transgenic [C57BL/6J X C3/HeJ F1] females, except for PrP.α-synuclein mice which have been successively backcrossed into the C57BL6/J strain. Non-transgenic mice [C57BL/6J X C3/HeJ F1] were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). The procedures involving animals were approved by the Animal care & Use Committee of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

2.2. Detergent extraction and gel electrophoresis

The methods used in detergent extraction of tissue homogenates have been previously described [43]. Briefly, tissue homogenates were extracted by sonicating in buffer A (10mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1mM EDTA pH 8.0, and 100mM NaCl; 1% Nonidet P40; proteinase inhibitor cocktail 1:100 dilution <P 8340, Sigma, St. Louis, MO>), and then centrifuged at >100,000 g for 10 minutes to separate supernatant S1 and pellet P1. The P1 pellet was extracted once more with buffer A, and centrifuged to produce the pellet P2, which was either suspended in buffer B (10mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1mM EDTA pH 8.0, and 100mM NaCl; 0.5% Nonidet P40; 0.5% deoxycholic acid; 2% SDS) for denaturing SDS-PAGE or in buffer C (10mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1mM EDTA pH 8.0, 9M urea, 2% Nonidet P40, 40mM DTT) for 2D gel electrophoresis. Samples were mixed with 4X Laemmli Buffer and boiled before denaturing SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Equal protein loading and transfer was routinely monitored by ponceau-S staining of the nitrocellulose membranes.

2.3. Immunoblotting and Immunohistochemistry

Antibodies against Hsp25 (SPA-801), αB-crystallin (SPA-222), Hsp40 (SPA-450), Hsp60 (SPA-806), Hsp70 (SPA-812), and Hsp90 (SPA-830) were purchased from Stressgen (Victoria, BC, Canada). A monoclonal antibody for α-Syn was purchased from BD transduction laboratories (San Diego, CA). The antibody against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) was purchased from Dako Corp (Carpenteria, CA). Luxol fast blue was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Immunoblotting and Immunocytochemical analysis was performed as previously described [24;43;45]. Luxol fast blue staining for myelin was done on paraffin sections (12 μm). The sections were treated with xylene and 95% alcohol and stained with 0.1% Luxol Fast Blue in 95% ethanol, 0.5% acetic acid and destained using 0.05% LiCO3.

2.4. Cell-free aggregation assay

Brains from young PrP.α-SynA53T transgenic mice were homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) with proteinase inhibitors. The homogenate was centrifuged at 150,000 g and 4 °C for 50 minutes, and the supernatant was adjusted to 2 mg/ml of proteins with PBS. To induce aggregation, 50 μl of samples were added to a 200 μl tube, and shaken on a titer plate shaker (750 rpm) at 37 °C for 12 hrs. To study the affects of αB-crystallin on α-synuclein aggregation, purified α-crystallin (predominantly αB-crystallin, SPP-225, Stressgen, Victoria, BC, Canada) was added at 0.4 ug/ul. In some reactions, both α-crystallin (0.4 ug/ul) and purified mouse monoclonal anti-αB-crystallin IgG (0.16 ug/ul) were present in the reaction. For the control reactions, equal amount of solvent alone were added. The resulting samples were centrifuged in a Beckman airfuge (>100,000 g) for 10 minutes, and the pellets were washed twice with PBS. The resulting pellets were considered aggregated proteins, and resuspended in PBS with 2% SDS for further analyses.

3. Results

3.1 Up-regulation of Hsp25 and αB-crystallin in murine models of ALS and an α-SynA53T model of PD, but not in models of polyglutamine diseases

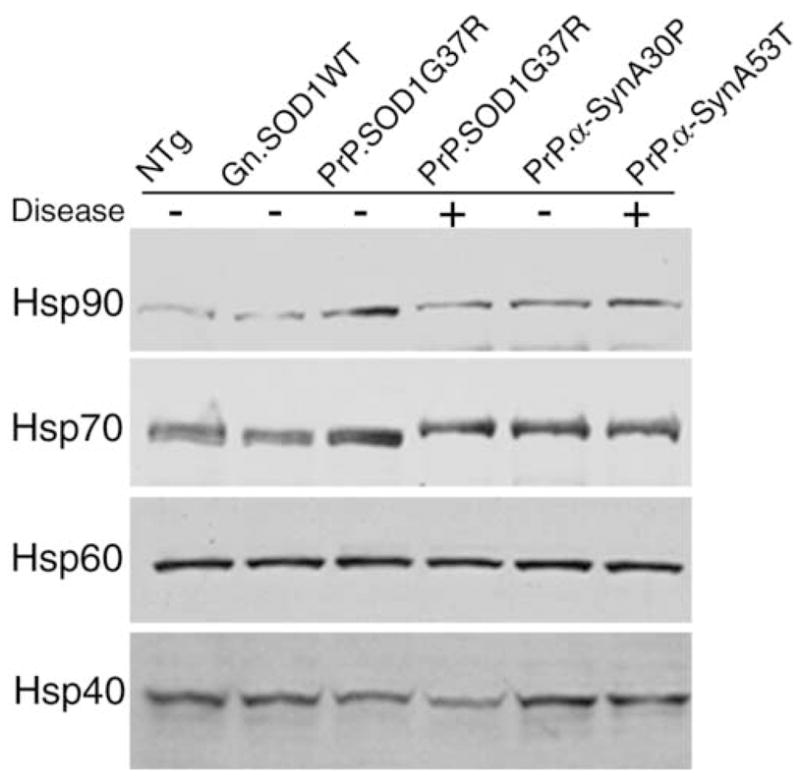

The SOD1G37R and α-SynA53T models have similar cellular pathology and behavioral phenotypes; both develop motor deficits leading to paralysis with associated cellular pathology in the brain stem and the spinal cord. To investigate the responses of molecular chaperones in these two models, levels of major chaperone proteins, in both their soluble and insoluble forms, were investigated. For Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp60, and Hsp40, no significant changes in expression levels were associated with the transgene expression or the presence of symptoms in either SOD1 or α-Syn mice (Fig. 1). We also examined how the levels of these chaperones are regulated by age. As with the study of adult mice, there was no evidence of changes in the levels of Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp60, and Hsp40, as function of age (not shown).

Fig. 1. The levels of catalytic chaperones (Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp60, and Hsp40) do not change in disease associated with mutant SOD1 and mutant α-Syn.

20 μg of protein from soluble fractions of the spinal cord homogenates were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with antibodies against Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp60, or Hsp40. Samples include symptomatic (+) mice homozygous for PrP.SOD1G37R or hemizygous fro PrP.α-SynA53T, and non-symptomatic (−) age-matched controls including non-transgenic (NTg), those carrying the human wild-type genomic gene (Gn.SOD1WT), hemizygous for PrP.SOD1G37R, or hemizygous for PrP.α-SynA30P.

To examine the sHSPs, several strains of SOD1 and α-Syn transgenic mice were used. The mutated human genomic SOD1 (Gn.SOD1G37R) gene expresses the protein ubiquitously in the mouse and these animals develop ALS-like motor neuron disease, whereas Gn.SOD1WT (line 76) expresses wild-type human SOD1 at comparable levels but does not cause disease [47]. The PrP promoter drives expression of transgenes in neurons and astrocytes of the CNS, and in other tissues including muscle [45]. A line of mice expressing SOD1G37R under the control of the PrP promoter (line 110) is free of disease as hemizygous transgenic mice, but develops motor neuron disease as early as 7 months of age when the transgene dose is increased by breeding to homozygosity [45]. The same PrP promoter vector was used to establish a PD mouse model by expressing the α-SynA53T; mice from line G2-3 exhibit brain stem and spinal cord pathology and motor deficit phenotypes. By contrast mice expressing α-SynA30P at a comparable level (line O2), via the same vector, do not develop disease symptoms or pathology [24;28]. Since both SOD1 and α-Syn models have spinal cord pathology, this tissue was harvested to study and compare the expression of sHSPs (Fig. 2).

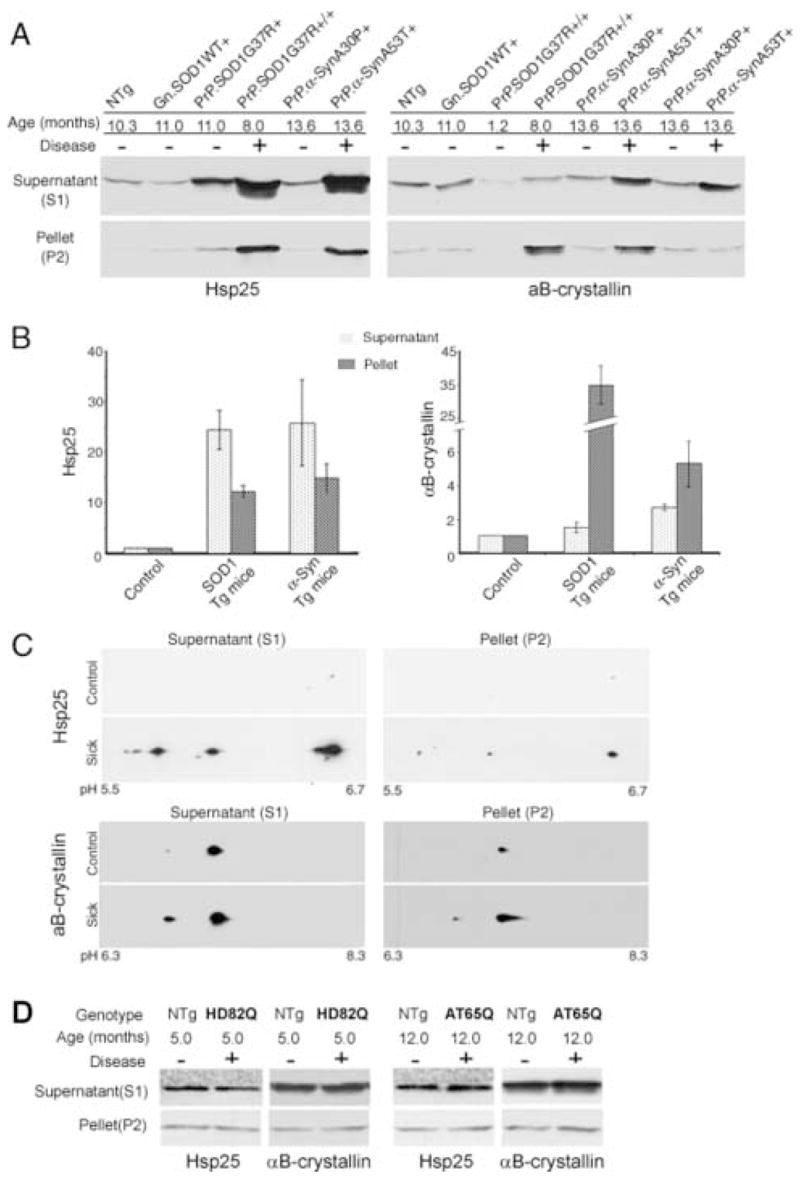

Fig. 2. Increased expression and altered solubility of Hsp25 and αB-crystallin associated with disease in mutant SOD1 and mutant α-Syn mouse models.

(A) Spinal cord homogenates were extracted into the soluble fraction S1 and the non-ionic detergent insoluble fraction P2. 20 μg of S1 protein and 12 μg of P2 proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with anti-Hsp25 or anti- αB-crystallin antibodies. For mouse genotype denotation, Gn denotes the genomic construct transgene, and PrP the mouse Prion promoter transgene; “+/+” denotes homozygous for the transgene, and “+” hemizygous. For disease phenotype, “+” denotes symptomatic or paralytic, and “−“ non-symptomatic. Note that PrP.α-Syn samples were duplicated in the anti-αB-crystallin blot to demonstrate the variability in P2 fractions. (B) Western analyses are summarized graphically. Controls were age-matched NTg, Gn.SOD1WT, or PrP.α-SynA30P mice, and their sHSP levels were normalized to 1. The relative levels of Hsp25 or αB-crystallin in symptomatic SOD1 mice (n = 6, three Gn.SOD1G37R and three PrP.SOD1G37R mice) or α-Syn mice (n = 6, PrP.α-SynA53T) were measured by comparing to controls on the same gel, and the fold increase from the control values were plotted (Means and standard errors of means). (C) 2D-PAGE analysis of Hsp25 and αB-crystallin. Soluble and insoluble spinal cord proteins from normal or sick Gn.SOD1G37R (line 29) mice were separated by 2D-PAGE (IEF/SDS-PAGE) and Western blotted for Hsp25 or αB-crystallin. Upper panels show the analyses of Hsp25. The three charged isoforms (likely representing different phosphorylation states) are proportionally increased in both the soluble and insoluble fractions from the affected tissues. Lower panels show the analyses of αB-crystallin. At least two isoelectric isoforms (likely representing phophorylation states) are proportionally increased in both the soluble and insoluble fractions. (D) Representative immunoblots of spinal cord tissues from symptomatic PrP.htt-N171-82Q (HD82Q) and PrP.AT65Q transgenic mice (40 μg of S1 protein and 20 μg of P2 proteins) with Hsp25 or αB-crystallin antibodies. “+” denotes disease phenotypes as characterized in previous studies [35;36].

In both mouse models, Hsp25 was significantly up-regulated, in both the supernatant and pellet fractions of non-ionic detergent extracts in spinal cords from all symptomatic SOD1 and α-Syn mice (Fig. 2A–B, left). The induction of Hsp25 was selectively associated with neurodegeneration since the Hsp25 levels were not elevated in transgenic mice expressing high levels of non-pathogenic SOD1 (SOD1WT) or α-Syn (A30P) protein (Fig. 2A, left). In symptomatic mice from both models, αB-crystallin was also induced but the solubility profiles of αB-crystallin and Hsp25 differ. In both models, the levels of Hsp25 are significantly increased in both the soluble and insoluble fractions, whereas the bulk of the induced αB-crystallin is associated with the detergent insoluble fraction (Fig. 2A–B). Further, while the levels of αB-crystallin in the insoluble fraction (P2), from both Gn.SOD1G37R and PrP.SOD1G37R, were significantly higher than controls in virtually all of the symptomatic SOD1 mice (>10 fold), the levels of insoluble αB-crystallin were highly variable in the mutant α-Syn transgenic mice. For example, in some symptomatic α-SynA53T mice, significant increases in the levels of detergent soluble αB-Crystallin were not accompanied by a corresponding increase in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 2A, right panels, last right lane). Thus, our results indicate that accumulation of insoluble αB-crystallin is a variable feature of the α-SynA53T disease model. In the course of our analysis, we also observed that normal aging has a noticeable effect on induction of αB-crystallin (see below), which may explain the low level in the 1.2 month old PrP.SOD1G37R mouse (Fig. 2A, right panels, third lane). The increases in the Hsp25 and αB-crystallin levels were clearly restricted to the pathologically affected regions (brain stem and spinal cord). Expression levels of both sHSPs in unaffected regions (e.g. cortex) were very low and not different from non-transgenic animals (not shown).

Because Hsp25 and αB-crystallin are known to be phosphorylated at several sites [3;30], we used 2D-PAGE to examine whether the induction of these sHSPs is associated with posttranslational modifications. For both proteins, immunoblot analysis of isoforms resolved by 2D-PAGE revealed several isoelectric variants in the soluble and insoluble fractions; these isoforms correspond to those reported to be generated by phosphorylation (Fig. 2C) [11;17]. However, because of very low level of Hsp25 level in control samples, we were not able to accurately detect the more acidic Hsp25 isoforms. Thus, we could not determine if the relative abundance of Hsp25 isoforms change with the disease. Overall, it appears that the the major isoforms are similarly represented in the both the soluble and insoluble fractions from the affected tissues.

Polyglutamine diseases such as Huntington’s Disease and Dentato-Rubral Pallido-Luysian Atrophy, have been modeled in mice by expressing a mutant N-terminal fragment of hungtingtin (htt-N171-82Q; line 81) or a full-length atrophin-1 (AT65Q; line 150), respectively, via the same PrP vector. Both polyglutamine proteins undergo protein aggregation, a process implicated in pathogenesis of both diseases. In both the htt-N171-82Q and AT65Q mice, all major regions of the brain and brain stem exhibit nuclear inclusion pathology [35;36]. Motor neurons of the spinal cord also exhibit nuclear inclusions, particularly in the large motor neurons (Jiou Wang, Gabriele Schilling, and David R Borchelt, unpublished observations). However, these models of polyglutamine toxicity are not associated with significant astrogliosis in any part of the CNS [35;36]. In contrast to the strong induction of sHSPs in the mutant SOD1 and α-Syn mice, there is little or no change in the levels of Hsp25 or αB-Crystallin in the spinal cords of either polyglutamine model (Fig. 2D). Thus the expression of mutant SOD1 and α-Syn is associated with a specific induction of sHSPs in the degenerating spinal cord.

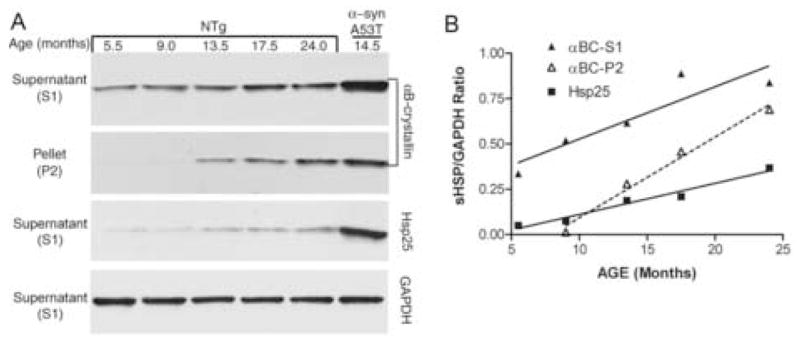

During the course of the present study, we noticed that multiple samples from older mice exhibited higher sHSP levels than younger mice, suggesting that aging may be a factor affecting the levels or solubility of sHSPs in CNS. To test this idea, mice of the same gender with the same genetic background (C57BL/6J X C3H/HeJ) were analyzed at multiple ages. Significant increases in the levels of soluble and insoluble αB-Crystallin were noted (Fig. 3). Less obvious, but significant, changes in Hsp25 were noted (Fig. 3). Gender did not have a detectable effect on the levels of either protein (not shown). It is notable that neurodegeneration has a much more remarkable effect on the up-regulation of both proteins, as demonstrated by a parallel sample from a symptomatic α-SynA53T mouse (Fig. 3A). We have not observed any obvious change in the distribution of either sHSP by immunohistochemistry in normal aging mice (not shown).

Fig. 3. Up-regulation of insoluble αB-crystallin in the CNS during normal aging.

(A) Normal male non-transgenic (NTg) mice with different ages from the same strain (C57BL/6L X C3H/HeJ) were used to collect their spinal cords, from which 20 μg of S1 protein and 12 μg of P2 protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with an anti-αB-crystallin antibody and an anti-Hsp25 antibody. Immunoblot analysis for GAPDH was used as loading control. A symptomatic PrP.α-SynA53T mouse was used as comparison. (B) The relative levels of sHSPs were determined by densitometry from the immunoblots shown in panel A. The linear regression analysis clearly shows aging is associated with significant increase (i.e. slope is significantly different from 0) in sHSP expression (R2 and p values are: 0.9670 and 0.0026 for Hsp25, 0.8379 and 0.029 for soluble αB-crystallin, and 0.9846 and 0.0078 for insoluble αB-crystallin).

3.2. Up-regulation of Hsp25 and αB-crystallin occur primarily in reactive astroglia and oligodendrocytes, respectively

The distribution of induced Hsp25 and αB-Crystallin in PrP.SOD1G37R and PrP.α-SynA53T transgenic mice was examined by immunohistochemical analyses of tissues from transgenic and non-transgenic mice. In normal adult mice, Hsp25 is expressed at very low levels in the forebrain, which is confirmed by Western analyses (not shown). In the cerebellum, Hsp25 distinctly marks a subset of Purkinje cells (Fig. 4B). In the brain stem and spinal cord, the Hsp25 antibody stains a subset of large well-defined neurons (not shown), largely in agreement with previous reports [2;44].

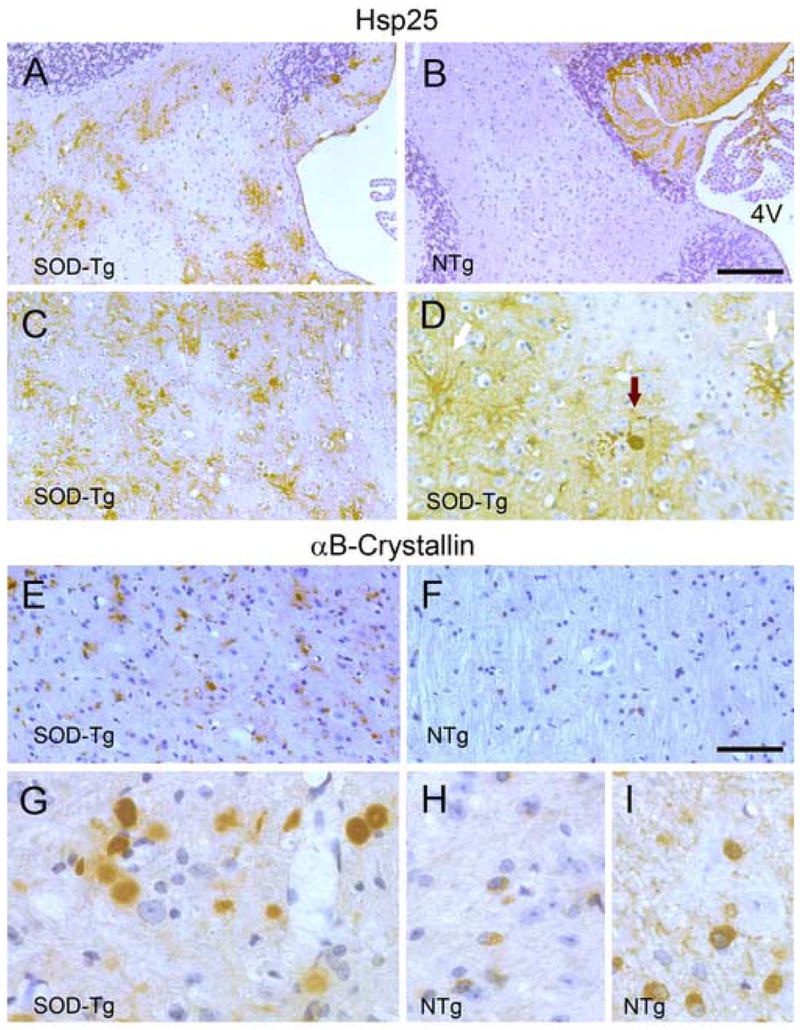

Fig. 4. Immunohistochemistry of Hsp25 and αB-crystallin in the PrP.SOD1G37R transgenic mice.

Representative images from symptomatic mice (SOD-Tg, A, C, D, E, and G) and age-matched NTg mice (B, F, H, and I) immunostained for Hsp25 (A–D) or αB-crystallin (E–I). The Hsp25 staining of the cerebellar white matter (A, B) and a sagittal section of spinal cord (C, D) shows increased astroglial Hsp25 staining in SOD-Tg mice. Higher magnification image of spinal cord section (D) shows typical astrocyte staining (white arrow) and an inclusion body of abnormal cell (black arrow). Representative αB-crystallin stained sections of spinal cords from symptomatic mice (E, G) and age-matched NTg mice (B, H, I) are shown. Higher magnification images (G–I) show irregular- or round-shaped cell remnants or inclusion bodies in SOD-Tg mice (G) where as αB-crystallin staining is limited to cell bodies of apparent oligodendrocytes in NTg mice (H, I). Even heavier staining of NTg spinal cord (I) do not show aberrant staining seen in SOD-Tg mice. Scale bar: 50 μm for A, B, E & F; 20 μm for C, D, G-I. 4V, the fourth ventricle.

In the symptomatic mutant PrP.SOD1G37R transgenic mice, the most obvious increase in Hsp25 immunoreactivity was associated with reactive astrocytes (Fig. 4). In addition to the occasional Hsp25 positively stained cells in the forebrain, clusters of heavily stained glial cells were present in the inferior colliculus, cerebellar white matter (Fig. 4A), and the neuropil throughout the brain stem and spinal cord (Fig. 4C, D). Overall, there was no obvious increase in neuronal Hsp25 staining, and most, if not all, of the cells that stain intensely for Hsp25 have cellular and nuclear morphology that is consistent with astrocytes (Fig. 4C,D). In some cells, intense Hsp25 staining suggests inclusion-like deposits (Fig. 4D). While further studies are needed to confirm the cellular identity of cells with Hsp25 “aggregates”, the cellular morphology (presence of processes) suggest that they are also astrocytes. Up-regulation of Hsp25 in astrocytes of PrP.SOD1G37R transgenic mice is consistent with previous studies showing similar induction of Hsp25 expression in the astrocytes of Gn.SOD1-G93A and Gn.SOD1-L126Z transgenic mice [41;44]. In symptomatic PrP.α-SynA53T mice, similar but less profound Hsp25 pathology is found (Fig. 5A–D). As in the mutant SOD1 transgenic mice, increased Hsp25 expression is largely localized to cells with astroglial morphology and is restricted to regions associated with robust α-synucleinopathy (Fig. 5A–D). Unlike the mutant SOD1 transgenic mice, heavily Hsp25-postive astroglial deposits were not observed in the disease-affected α-Syn transgenic mice.

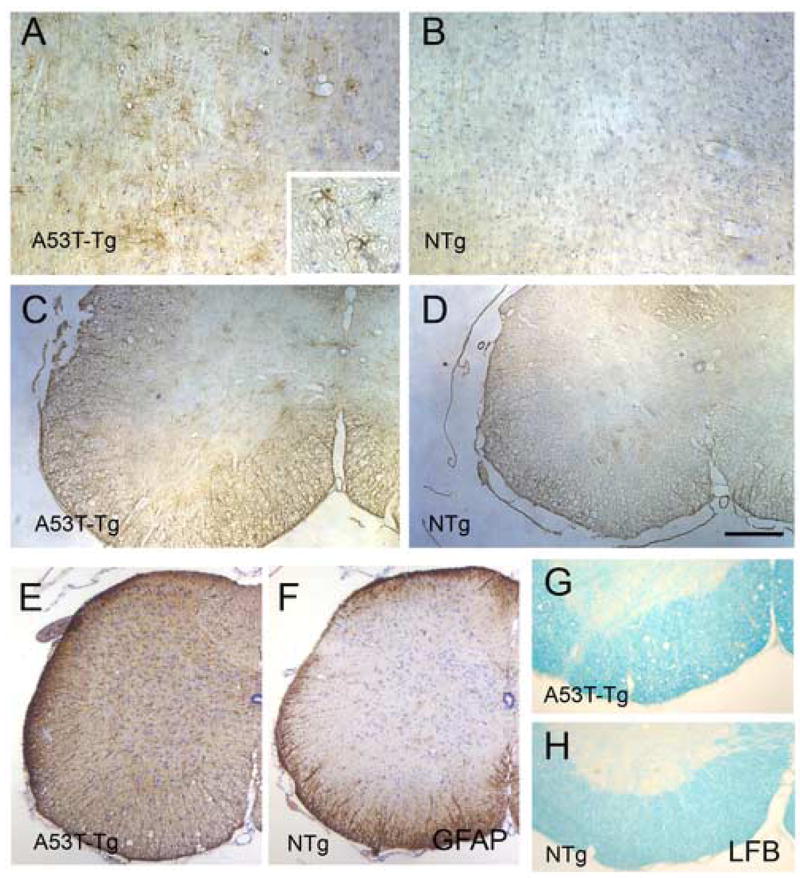

Fig. 5. Immunohistochemistry of Hsp25 in the PrP.α-SynA53T transgenic mice.

Representative Hsp25 stained images from disease-affected mice (A, C) and age-matched NTg mice (B, D) are shown. Up-regulation of Hsp25 is limited to astrocytes but less profound than with the mutant SOD1 mice. Shown are sagittal sections of brain stem (A, B) and horizontal sections of spinal cord (C, D). GFAP staining of the spinal cord sections (E, F) shows severe astrogliosis in A53T Tg mice. Luxol Fast Blue (LFB) staining of spinal cord (G, H) also shows distintegration of myelinated fiber tracts in A53T Tg mice. Scale bar: 50 μm for A, B; 200 μm for C, D, G, H; 250 μm for E, F.

In normal adult mice, the αB-crystallin positively stained cells are restricted in white matter of the brain, while evenly distributed in both the gray matter and the white matter of the spinal cord (Fig. 4F, H, I). Based on the nuclear morphology and scant cytoplasm of the immunoreactive cells, it is likely that the αB-crystallin expression is localized to the oligodendrocytes in spinal cords of normal mice (Fig. 4H, I) [44]. In the disease-affected PrP.SOD1G37R transgenic mice, αB-crystallin localization was highly abnormal as indicated by the presence of heavily stained “clumps” in the neuropil, with either irregular or round shapes, that are likely cellular inclusions or cell remnants (Fig. 4E, G). The cellular origin of these intensely stained clumps is unclear. While the induction of αB-Crystallin seems to occur in astroglial cells in the transgenic model expressing the truncated SOD1 mutant, Gn.SOD1-L126Z [44], the abnormal αB-crystallin “aggregates” here are not clearly associated with any cells of specific morphology. Given that the expression αB-Crystallin is limited to oligodendrocytes in nontransgenic and in young PrP.SOD1G37R mice, it is likely that the αB-Crystallin “aggregates” may be associated with oliogodendrocytes. Overall, the distribution of these αB-crystallin deposits in the CNS closely parallels the distribution of Hsp25-stained astrocytes and neuropathology (i.e., most abundant in the inferior colliculus, cerebellar white matter, brain stem, and spinal cord).

Consistent with variable levels of αB-crystallin expression in the PrP.α-SynA53T transgenic mice, there were no obvious abnormalities in αB-crystallin localization in the spinal cords of symptomatic α-Syn transgenic mice. However, overall αB-crystallin staining was increased throughout the neuropil (not shown). The lack of abnormal αB-crystallin localization in α-Syn transgenic mice is not because of the absence of astrogliosis (Fig. 5E) or myelinated axon degeneration in brain stem and spinal cord. Luxol fast blue staining of the brain stem and spinal cord from the disease-affected mutant α-Syn transgenic mice shows significant disintegration of myelinated fiber tracts (Fig. 5G).

Collectively, these results suggest that Hsp25 is induced in astrocytes as a general component of reactive astrocytic response in the mutant SOD1 and mutant α-Syn transgenic mouse models. However, despite the degeneration of myelinated axons and disintegration of CNS myelin in the α-SynA53T mice, accumulation of αB-crystallin into abnormal morphologies such as “clumps” appear to be specific to the mutant SOD1 mice.

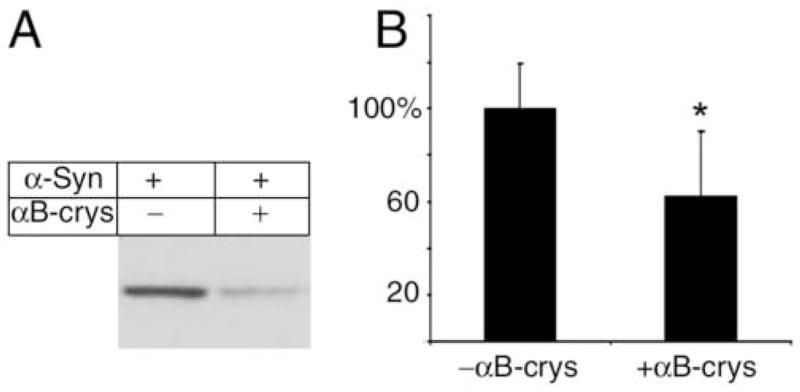

3.3 Suppression of α-SynA53T aggregation by αB-crystallin

In a previous study, we found that αB-crystallin can inhibit aggregation of the truncation mutant SOD1-L126Z in a cell-free aggregation assay [44]. To ask whether αB-Crystallin can exert such chaperone activity on α-SynA53T, we examined the affects of αB-crystallin on the aggregation of this protein from mouse tissues using the same cell-free assay. Incubation of high-speed supernatants from brain at 37°C leads to formation of insoluble α-SynA53T aggregates within few hours. But in the presence of αB-crystallin the formation of insoluble α-SynA53T aggregates is significantly reduced (Fig. 6). The activity of αB-crystallin was partially neutralized by an inhibitory monoclonal anti-αB-crystallin antibody, confirming that αB-crystallin is an inhibitor of α-SynA53T aggregation.

Fig. 6. αB-crystallin suppresses aggregation of α-Syn.

Brain supernatants from young α-SynA53T transgenic mice, containing 1 μg/μl total protein, with 0.4 μg/ul of BSA (A) or 0.4 μg/ul of purified α-crystallin (predominantly αB-crystallin) (B), were incubated at 37°C with shaking for 12 hrs and centrifuged to collect the pellet fraction containing aggregated proteins. The pellet fraction was analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-α-Syn antibody. Adding α-crystallin significantly suppresses the aggregation of α-Syn (B). Asterisk marks significance with one-tailed p < 0.01 in a Student’s t-test; n = 5; error bars represent standard deviations.

4. Discussion

The present study documents differences in the regulation of heat shock protein responses in mouse models of familial ALS, PD, HD, and DRPLA. The transgene expression in the models studied here is regulated by the mouse prion protein vector. Thus, while these mouse models express mutant genes that are specific for different diseases, they are completely comparable in terms of the expression patterns of genes. Remarkable increases in the levels of two sHSPs, Hsp25 and αB-crystallin, were associated with disease in mutant SOD1 and mutant α-Syn transgenic mouse models. In contrast, the expression of two distinct polyglutamine proteins, an N-terminal fragment of hungtingtin and a full-length atrophin-1, did not induce significant alterations in the levels of either of these sHSPs. We also show that changes in the levels of these sHSPs in both SOD1 and α-Syn models are associated with the presence of reactive astroglia. Most of the induced Hsp25 is found in cells with typical astroglia morphology, whereas the cellular distribution of αB-crystallin appears to be primarily oligodendrocytes with clumps of reactivity in neuropil. In a prior study of a model with a different mutant SOD1 L126Z, induction of αB-crystallin in astrocytes was demonstrated [44]. Thus, it is possible that part of the neuropil staining seen in the PrP.SOD1G37R mice originates from astroglial cells. Other studies have also shown induction of sHSP in glial cells with disease in mutant SOD1 transgenic mice [27;41]. The increase in glial Hsp25 expression contrasts with a decrease in Hsp25 expression in motor neurons of presymptomatic Gn.SOD1G93A mice [27] and in surviving motor neurons of mutant SOD1 L126Z transgenic mice [44]. While we have not focused on the neuronal expression of sHSPs in the current study, the surviving motor neurons in the SOD1 transgenic mice did show reduced Hsp25 staining (data not shown) and the ventral horn motor neurons in α-SynA53T transgenic mice seem to stain less intensely for Hsp25 than in control mice (see Fig. 5 C, D).

Between the SOD1 and α-Syn models, partitioning of sHSPs into detergent insoluble complexes was exhibited at a higher degree in the mutant SOD1 model. Furthermore, we noted that normal aging of mouse CNS is also associated with increased partitioning of αB-crystallin into the detergent insoluble phase. As was previously reported for mutant SOD1L126Z, αB-Crystallin was capable of inhibiting the aggregation of α-SynA53T. Collectively, our results indicate that a component of the glial response is to induce sHSPs, including αB-crystallin which is capable of preventing the aggregation of mutant SOD1 [44] and α-SynA53T in vitro.

Despite the dramatic induction of sHSPs in the SOD1 and α-Syn transgenic mice, we did not observe changes in the levels of Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp60, or Hsp40. Nonetheless, the induction of the sHSPs could still impact on the activity of the catalytic HSPs to modulate the folding and degradation of mutant proteins through facilitation or altering the overall balance in chaperone capacity. Several studies have implicated catalytic chaperones in several neurodegenerative diseases. For example, large inclusions in SOD1 mice/rats are immunoreactive for Hsp70 [46], and toxicity of SOD1G93A in primary motor neurons is attenuated by increased Hsp70 [5]. However, unlike the suppression of neuropathology by elevating Hsp70 in mouse models of polyglutamine disease [1;8], transgenic elevation of Hsp70 did not affect disease course or pathology in mutant SOD mouse models [25], suggesting differences in regulation and substrate specificity of chaperons in two disease settings. However, pharmacological induction of activated HSF-1 and a number of chaperones, including HSP70 and HSP 90, by arimoclomol, is associated with attenuation of disease in the mutant SOD1 mouse model [21]. We suggest that Hsp25 and αB-crystallin, the two major stress-inducible sHSPs in mammals, may serve to cooperate with other catalytic chaperones to alter the overall balance of chaperone function in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. It is unknown whether there are unidentified chaperons that are similarly regulated in response to stress in neurons. The lack of a significant increase in the levels of catalytic HSPs or tested sHSPs in neurons of affected tissues of these mouse models may reflect an inability of neurons to respond to an increased need for chaperone function.

The use of the prion promoter in driving transgene expression allowed us to compare the effects of different genes in mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases under a setting of comparable patterns of expression. Both PrP.SOD1G37R and PrP.α-SynA53T mice show increases Hsp25 and αB-crystallin expression. However, in the mutant SOD1 transgenic mice, most of the induced αB-crystallin is detergent insoluble; and in the α-Syn mice the cellular patterns of immunostaining were often unremarkable. It is unclear whether this difference is a consequence of differences in the cellular pathology or specific biochemistry between the misfolded proteins and sHSPs. By contrast, polyglutamine disease models, such as the PrP.htt-N171-82Q or PrP.AT65Q mice, lack any such significant up-regulation. The differences in the sHSP expression between different models is not likely due to simple variations in expression levels of transgene since mice that express high levels of wtSOD1 or α-SynA30P do not lead to neuropathology or sHSP induction. One of the key differences between the polyglutamine disease models and both SOD1 and α-Syn mouse models is that the latter exhibit significant astrogliosis in all affected regions of the CNS. Thus a component of glial cell activation appears to be the induction of sHSP expression. However, it is possible that differential sHSP induction could be related to mechanisms that are independent from glial response. For example, nuclear and cytoplasmic aggregates may differentially induce cellular protein quality control response, or the lack of sHSP induction in polyglutamine models could be a consequence of transcriptional dysfunction caused by the polyglutamine expansion [37]. Despite these caveats, our results indicate to disease-specific responses to the pathologic accumulation of misfolded proteins in these neurodegenerative disease models.

The fact that glial cells can respond to a variety of stressors by effectively increasing the levels of some sHSPs may indicate that glial cells are less vulnerable to accumulation of misfolded protein than neurons. Generally this seems to be true in the mouse models. However, there is at least one example of mutant SOD1 mice where inclusions are present in astrocytes; mice expressing SOD1-G85R via fragments of human genomic DNA [6]. There are also examples of human diseases where astroglia accumulate protein inclusions containing SOD1 or oligodendrocytes accumulate inclusions containing α-Syn [20] [39]. Thus, although the remarkable induction of Hsp25 and αB-crystallin selectively in glial cells provides an opportunity for sHSPs to modulate protein misfolding, it is clear that this response is either attenuated or insufficient in some disease settings.

The age-associated up-regulation of the sHSPs is consistent with the idea that both neurodegeneration and aging are associated with glial activation and the accumulation of misfolded or damaged proteins. The implication of these chaperones in protein folding related diseases is supported by studies showing that αB-crystallin can suppress the aggregation of α-Syn or SOD1 in cell-free assays, and the sHSP can suppress aggregation of purified α-Syn in vitro [32]. Furthermore, sHSPs have been recently implicated in normal aging process of simple organisms; up-regulation of sHSPs was observed in C. elegans or Drosophila mutants that exhibit extended life spans [22;42]. Therefore, neurodegeneration and age-related decline may share important cellular pathways that involve protein unfolding stress and chaperone responses. Further understanding of the activities of these sHSPs may lead to new therapeutic agents for neurodegenerative as well as other age-related diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Juan Troncoso and Lee Martin for their help with the sHSP pathology and cellular identification. We also thank Michael Coonfield and Yanqun Xu for the technical assistance with the transgenic mice. This study was supported by grants to DRB (NS044278) and MKL (NS38065, NS38377) from the National Institutes of Neurologic Disease and Stroke (R01 NS 044278), the Muscular Dystrophy Association (DRB), the ALS Association (DRB), and by the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at The Johns Hopkins University (DRB).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: No current conflicts of interest are present between this work and any of the coauthors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adachi H, Katsuno M, Minamiyama M, Sang C, Pagoulatos G, Angelidis C, Kusakabe M, Yoshiki A, Kobayashi Y, Doyu M, Sobue G. Heat shock protein 70 chaperone overexpression ameliorates phenotypes of the spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy transgenic mouse model by reducing nuclear-localized mutant androgen receptor protein. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2203–2211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02203.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong CL, Krueger-Naug AM, Currie RW, Hawkes R. Constitutive expression of heat shock protein HSP25 in the central nervous system of the developing and adult mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2001;434:262–274. doi: 10.1002/cne.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benndorf R, Kraft R, Otto A, Stahl J, Bohm H, Bielka H. Purification of the growth-related protein p25 of the Ehrlich ascites tumor and analysis of its isoforms. Biochem Int. 1988;17:225–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borchelt DR, Davis J, Fischer M, Lee MK, Slunt HH, Ratovitsky T, Regard J, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Sisodia SS, Price DL. A vector for expressing foreign genes in the brains and hearts of transgenic mice. Genet Anal (Biomed Eng ) 1996;13:159–163. doi: 10.1016/s1050-3862(96)00167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruening W, Roy J, Giasson B, Figlewicz DA, Mushynski WE, Durham HD. Up-regulation of protein chaperones preserves viability of cells expressing toxic Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase mutants associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem. 1999;72:693–699. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruijn LI, Becher MW, Lee MK, Anderson KL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Sisodia SS, Rothstein JD, Borchelt DR, Price DL, Cleveland DW. ALS-linked SOD1 mutant G85R mediates damage to astrocytes and promotes rapidly progressive disease with SOD1-containing inclusions. Neuron. 1997;18:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Concannon CG, Gorman AM, Samali A. On the role of Hsp27 in regulating apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2003;8:61–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1021601103096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings CJ, Sun Y, Opal P, Antalffy B, Mestril R, Orr HT, Dillmann WH, Zoghbi HY. Over-expression of inducible HSP70 chaperone suppresses neuropathology and improves motor function in SCA1 mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1511–1518. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jong WW, Caspers GJ, Leunissen JA. Genealogy of the alpha-crystallin--small heat-shock protein superfamily. Int J Biol Macromol. 1998;22:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(98)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evgrafov OV, Mersiyanova I, Irobi J, Van Den BL, Dierick I, Leung CL, Schagina O, Verpoorten N, Van Impe K, Fedotov V, Dadali E, Auer-Grumbach M, Windpassinger C, Wagner K, Mitrovic Z, Hilton-Jones D, Talbot K, Martin JJ, Vasserman N, Tverskaya S, Polyakov A, Liem RK, Gettemans J, Robberecht W, De Jonghe P, Timmerman V. Mutant small heat-shock protein 27 causes axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Nat Genet. 2004;36:602–606. doi: 10.1038/ng1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaestel M, Schroder W, Benndorf R, Lippmann C, Buchner K, Hucho F, Erdmann VA, Bielka H. Identification of the phosphorylation sites of the murine small heat shock protein hsp25. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14721–14724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrido C, Bruey JM, Fromentin A, Hammann A, Arrigo AP, Solary E. HSP27 inhibits cytochrome c-dependent activation of procaspase-9. FASEB J. 1999;13:2061–2070. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.14.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giasson BI, Duda JE, Quinn SM, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Neuronal α-synucleinopathy with severe movement disorder in mice expressing A53T human α-synuclein. Neuron. 2002;34:521–533. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, Caliendo J, Hentati A, Kwon YW, Deng H-X, Chen W, Zhai P, Sufit RL, Siddique T. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haslbeck M, Franzmann T, Weinfurtner D, Buchner J. Some like it hot: the structure and function of small heat-shock proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:842–846. doi: 10.1038/nsmb993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horwitz J. Alpha-crystallin. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00278-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito H, Okamoto K, Nakayama H, Isobe T, Kato K. Phosphorylation of alphaB-crystallin in response to various types of stress. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29934–29941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwaki T, Kume-Iwaki A, Liem RK, Goldman JE. Alpha B-crystallin is expressed in non-lenticular tissues and accumulates in Alexander’s disease brain. Cell. 1989;57:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwaki T, Wisniewski T, Iwaki A, Corbin E, Tomokane N, Tateishi J, Goldman JE. Accumulation of alpha B-crystallin in central nervous system glia and neurons in pathologic conditions. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:345–356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato S, Shimoda M, Watanabe Y, Nakashima K, Takahashi K, Ohama E. Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with a two base pair deletion in superoxide dismutase 1 gene: multisystem degeneration with intracytoplasmic hyaline inclusions in astrocytes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:1089–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kieran D, Kalmar B, Dick JR, Riddoch-Contreras J, Burnstock G, Greensmith L. Treatment with arimoclomol, a coinducer of heat shock proteins, delays disease progression in ALS mice. Nat Med. 2004;10:402–405. doi: 10.1038/nm1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurapati R, Passananti HB, Rose MR, Tower J. Increased hsp22 RNA levels in Drosophila lines genetically selected for increased longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:B552–B559. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.11.b552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavoie JN, Hickey E, Weber LA, Landry J. Modulation of actin microfilament dynamics and fluid phase pinocytosis by phosphorylation of heat shock protein 27. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24210–24214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee MK, Stirling W, Xu Y, Xu X, Qui D, Mandir AS, Dawson TM, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL. Human alpha-synuclein-harboring familial Parkinson’s disease-linked Ala-53 --> Thr mutation causes neurodegenerative disease with alpha-synuclein aggregation in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8968–8973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132197599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Shinobu LA, Ward CM, Young D, Cleveland DW. Elevation of the Hsp70 chaperone does not effect toxicity in mouse models of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem. 2005;93:875–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowe J, McDermott H, Pike I, Spendlove I, Landon M, Mayer RJ. alpha B crystallin expression in non-lenticular tissues and selective presence in ubiquitinated inclusion bodies in human disease. J Pathol. 1992;166:61–68. doi: 10.1002/path.1711660110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maatkamp A, Vlug A, Haasdijk E, Troost D, French PJ, Jaarsma D. Decrease of Hsp25 protein expression precedes degeneration of motoneurons in ALS-SOD1 mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:14–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin LJ, Pan Y, Price AC, Sterling W, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL, Lee MK. Parkinson’s disease alpha-synuclein transgenic mice develop neuronal mitochondrial degeneration and cell death. J Neurosci. 2006;26:41–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4308-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehlen P, Preville X, Chareyron P, Briolay J, Klemenz R, Arrigo AP. Constitutive expression of human hsp27, Drosophila hsp27, or human alpha B-crystallin confers resistance to TNF- and oxidative stress-induced cytotoxicity in stably transfected murine L929 fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1995;154:363–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miesbauer LR, Zhou X, Yang Z, Yang Z, Sun Y, Smith DL, Smith JB. Post-translational modifications of water-soluble human lens crystallins from young adults. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12494–12502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pauli D, Tonka CH, Tissieres A, Arrigo AP. Tissue-specific expression of the heat shock protein HSP27 during Drosophila melanogaster development. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:817–828. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rekas A, Adda CG, Andrew AJ, Barnham KJ, Sunde M, Galatis D, Williamson NA, Masters CL, Anders RF, Robinson CV, Cappai R, Carver JA. Interaction of the molecular chaperone alphaB-crystallin with alpha-synuclein: effects on amyloid fibril formation and chaperone activity. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:1167–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Renkawek K, de Jong WW, Merck KB, Frenken CW, van Workum FP, Bosman GJ. alpha B-crystallin is present in reactive glia in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1992;83:324–327. doi: 10.1007/BF00296796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samali A, Robertson JD, Peterson E, Manero F, van Zeijl L, Paul C, Cotgreave IA, Arrigo AP, Orrenius S. Hsp27 protects mitochondria of thermotolerant cells against apoptotic stimuli. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:49–58. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0049:hpmotc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schilling G, Becher MW, Sharp AH, Jinnah HA, Duan K, Kotzuk JA, Slunt HH, Ratovitski T, Cooper JK, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Price DL, Ross CA, Borchelt DR. Intranuclear inclusions and neuritic pathology in transgenic mice expressing a mutant N-terminal fragment of huntingtin. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:397–407. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schilling G, Wood JD, Duan K, Slunt HH, Gonzales V, Yamada M, Cooper JK, Margolis RL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Takahashi H, Tsuji S, Price DL, Borchelt DR, Ross CA. Nuclear accumulation of truncated atrophin-1 fragments in a transgenic mouse model of DRPLA. Neuron. 1999;24:275–286. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugars KL, Rubinsztein DC. Transcriptional abnormalities in Huntington disease. Trends Genet. 2003;19:233–238. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00074-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor RP, Benjamin IJ. Small heat shock proteins: a new classification scheme in mammals. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tu PH, Galvin JE, Baba M, Giasson B, Tomita T, Leight S, Nakajo S, Iwatsubo T, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Glial cytoplasmic inclusions in white matter oligodendrocytes of multiple system atrophy brains contain insoluble alpha-synuclein. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:415–422. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vicart P, Caron A, Guicheney P, Li Z, Prevost MC, Faure A, Chateau D, Chapon F, Tome F, Dupret JM, Paulin D, Fardeau M. A missense mutation in the alphaB-crystallin chaperone gene causes a desmin-related myopathy. Nat Genet. 1998;20:92–95. doi: 10.1038/1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vleminckx V, Van Damme P, Goffin K, Delye H, Van Den BL, Robberecht W. Upregulation of HSP27 in a transgenic model of ALS. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:968–974. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.11.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker GA, White TM, McColl G, Jenkins NL, Babich S, Candido EP, Johnson TE, Lithgow GJ. Heat shock protein accumulation is upregulated in a long-lived mutant of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:B281–B287. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.7.b281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Slunt H, Gonzales V, Fromholt D, Coonfield M, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Borchelt DR. Copper-binding-site-null SOD1 causes ALS in transgenic mice: aggregates of non-native SOD1 delineate a common feature. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2753–2764. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J, Xu G, Li H, Gonzales V, Fromholt D, Karch C, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Borchelt DR. Somatodendritic accumulation of misfolded SOD1-L126Z in motor neurons mediates degeneration: alphaB-crystallin modulates aggregation. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2335–2347. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Xu G, Slunt HH, Gonzales V, Coonfield M, Fromholt D, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Borchelt DR. Coincident thresholds of mutant protein for paralytic disease and protein aggregation caused by restrictively expressed superoxide dismutase cDNA. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:943–952. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe M, Dykes-Hoberg M, Culotta VC, Price DL, Wong PC, Rothstein JD. Histological evidence of protein aggregation in mutant SOD1 transgenic mice and in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis neural tissues. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:933–941. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong PC, Pardo CA, Borchelt DR, Lee MK, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Sisodia SS, Cleveland DW, Price DL. An adverse property of a familial ALS-linked SOD1 mutation causes motor neuron disease characterized by vacuolar degeneration of mitochondria. Neuron. 1995;14:1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]