Abstract

Fifty-six Newcastle disease virus strains collected from 2000 to 2006 could be grouped into subgenotype VIId. However, they displayed cumulative mutations in and around the linear epitope of hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (residues 345 to 353) with time. The antigenicities of the variants that became predominant in Korea differ from each other and from the wild type.

Newcastle disease virus (NDV) is a single-stranded negative-sense RNA virus that belongs to the genus Avulavirus of the family Paramyxoviridae (18, 19). NDV strains comprise 10 genetic groups (I to X) and are subdivided into subgenotypes (VIa to VIh and VIIa to VIIe) (3, 7, 12-15, 29-31). Serologically, NDVs comprise a single serogroup, avian paramyxovirus 1 (25), but they represent distinct antigenic subtypes (1, 2, 24). Studies employing monoclonal antibodies have revealed several conformational epitopes of fusion (F) and hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN) proteins, and one linear epitope composed of 345 to 353 amino acid residues of the HN protein has been defined (5, 7-9, 22, 28). Among the HN proteins, mutations in and around the linear epitope of field NDVs are not rare, and some Korean field strains (4, 11) and foreign NDVs registered in the GenBank database harbor the same (E347K) or somewhat different mutations around the linear epitope (4). In Korea, an intensive vaccination policy has been implemented, and annual use of NDV vaccines has increased. Despite this, ND outbreaks at farms with well-vaccinated flocks and economic losses caused mainly by depressed egg production have raised questions concerning antigenic variations of NDVs (4, 11) and the efficacies of conventional vaccines against reduced egg production. Therefore, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis with a partial F gene to understand the genetic relationship of 56 NDV strains obtained during 2000 to 2006, investigated chronologically the variations of the linear epitope by HN gene analyses, and then compared the complete amino acid sequences of F and HN proteins of several NDVs. Furthermore, we compared the antigenicities of synthetic peptide analogues representing the linear epitope mutants, which were presently revealed by use of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) employing synthetic peptides and chicken antiserum.

The primer sets used are listed in Table 1. Numbering of each primer was based on the first nucleotide of the start codon of each gene. RNA isolation and reverse transcription-PCR were conducted as previously described (11). Sequencing and sequence analysis were performed as previously described (10). The computational conformation modeling was performed using SWISS-MODEL, an automated protein-homology modeling server, following the guidelines of the website (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/), and the modeled HN protein of KBNP-4152 was visualized with Deepview/swiss-pdbViewer, version 3.7 (6, 27). Chicken polyclonal antiserum against a vaccine strain (La Sota) and a representative field strain (KBNP-4152) with mutations in (E347K) and near (M354K) the linear epitope of HN (4) were produced in five 6-week-old specific-pathogen-free chickens by inoculation of 500 μl of oil emulsion vaccine that had been emulsified with equal volumes of formalin-inactivated infectious allantoic fluid and incomplete Freund's adjuvant (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). On the basis of the amino acid mutations at positions 347 and 354 of the HN protein, three synthetic oligopeptides containing amino acids 345 to 358 were synthesized as analogues of the wild-type (ORI), E347K (KM-VARI), and E347K-M354K (VARI) mutant linear epitopes. The amino acid sequences of oligopeptides are as follows: ORI, PDEQDYQIRMAKSS; KM-VARI, PDKQDYQIRMAKSS; and VARI, PDKQDYQIRKAKSS (Peptron, Daejon, Korea). The C terminus of each synthetic peptide was modified with four aminocaproic acids (23). For ELISA, 500 ng of peptide in acetate buffer (pH 4.4 for ORI) and in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6 for VARI and pH 9.2 for KM-VARI) and anti-La Sota and anti-KBNP-4152 antisera were used. Statistical analyses were conducted with a chi-square and Fisher's exact tests (95% confidence interval) using SPSS for Windows, version 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in the present study

| Name | Location (residue)a | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Function (protein) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDPt-F | −46 to −25 | ACGGGTAGAAGAGTCTGGATCC | Phylogenetic analysis and sequencing (F) |

| NDPt-R | 534-515 | TGCCACTGMTAGTTGYGATA | |

| Sf 6991 | 574-593 | ATACTATCCGGTTGCAGAGA | Linear epitope analysis (HN) |

| Sf 7575R | 1178-1158 | TTAGGTGGAATAGTCAGCACC | |

| ND4295F | −205 to −236 | CARCGTGCTGTCGCAGTGAC | RT-PCR and sequencing (F) |

| S4-R | −67 to −40 | CGGTAGAACGGATGTTGTGAAGCCTAA | |

| ND-5463R | 234-214 | GACTATGATTGACCCTGTCTG | Sequencing (F) |

| S5-F | −27-3 | CCGCGGCACCGACAACAAGAGTCAATCATG | RT-PCR and sequencing (HN) |

| ND-8425R | 292-272 | GATCTGGTGCTCTGCCCTTTC | |

| ND-6927 | 510-529 | GGTTGCACTCGGATACCCTC | Sequencing (H) |

The minus represents sequence downstream from the start codon.

Partial nucleotide sequences of the F genes (nucleotides 47 to 420) were determined, and all NDVs were grouped into virulent strains on the basis of amino acid sequences of the F protein cleavage site. According to the phylogenetic analysis, all NDVs could be classified into subgenotype VIId (data not shown), the only genotype isolated since 2000 in Korea (13). Genotype VIId viruses were first isolated from fowl in Japan and Taiwan in 1996 and 1998, respectively, and fowl and geese in China in 1997. During 1999 to 2001, this genotype became dominant in these countries (14, 17). The early presence and recent high prevalence of VIId viruses in these countries may support the possibility of NDV transmission from other Asian countries to Korea, but the exact route of transmission remains to be defined (4, 12, 13). Besides epizootiological findings, the genetic and immunological backgrounds supporting the predominance of the VIId genotype among other genotypes in these countries and Korea also require further investigation.

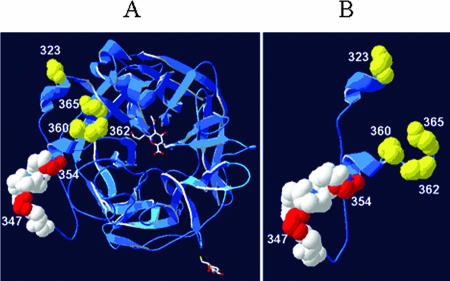

Amino acid sequences of the linear epitope and its flanking regions (amino acids 199 to 385) were compared by multiple alignments. Six mutation groups were defined on the basis of nonsynonymous mutations resulting in changes of amino acid charges (Table 2). Each of the amino acid changes, N323D, E347K, E354K, K360E, G362R, and G365D, was shared by 37.5% (21/56), 41.1% (23/56), 30.4% (17/56), 1.8% (1/56), 5.4% (3/56), and 8.9% (5/56) of recent NDVs, respectively. N323D-E347K-E354K (19.6%, or 11/56), N323D-E347K-E354K-G365D (8.9%, or 5/56), and N323D-E347K (7.1%, or 4/56) were common among recently isolated NDVs. In particular, mutations containing N323D-E347K-M354K were highly prevalent in 2005 (87.5%, or 14/16) (Table 3). The multiple amino acid changes reflect the accumulation of mutations in and around the linear epitope. Mutation groups I and II acquired the E347K and M354K mutations to become mutation groups III and IV, respectively, and mutation group IV acquired the additional K360E and G365D mutations to become mutation groups V and VI, respectively (Table 2). Computational conformation modeling of the HN protein has revealed the linear epitope to be composed of an alpha-helix and a loop, with 354K located more proximally to the receptor-binding pocket than the linear epitope (4). The variable residues 323, 360, 362, and 365 were located on the three-dimensional structure of the HN protein (Fig. 1). More specifically, residues 323 and 365 were located at a junction of the beta-sheet and the alpha-helix (323) and the loop (365), and all of the variable residues were located on the surface around the receptor-binding pocket (Fig. 1). To date, the linear epitope of HN protein has been reported to occur individually, but sheep antiserum against a peptide consisting of amino acids from position 355 to 375 reacted strongly with all of the NDVs tested (26). Therefore, the peptide is likely to be another continuous epitope, and the amino acid changes at residues 360, 362, and 365 may be involved in antigenic variation to some extent. Although the high frequency of N323D (37.5%) in Korean NDVs may support its biological importance, its role in antigenicity or protein function remains unknown. G362R [GenBank accession numbers CAA50868 (Edit) and ABL89192 (JAU04/Go)] and the variability of residues 360 [GenBank accession no. AAB05882 (K360N)] and 365 [GenBank accession nos. AAQ54634 (Cockatoo/Indonesia/14698/90, G365R) and AAQ54634 (Ck/Kenya/139/90, G365S)] were found in other NDVs in the GenBank database.

TABLE 2.

Variation of amino acids in the linear epitope and its flanking regions

| Mutation group | Amino acid change(s) | NDV strain(s) | No. of strains |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | G362R | SNU0164 | 1 |

| II | N323D, E347K | SNU2026, SNU2028, SNU3058, SNU6052 | 4 |

| III | E347K, G362R | SNU5070, SNU6014 | 2 |

| IV | N323D, E347K, M354K | SNU2124, KBNP-4152, SNU5005, SNU5009, SNU5062, SNU5063, SNU5064, SNU5065, SNU5074, SNU5076, SNU5081 | 11 |

| V | N323D, E347K, M354K, K360E | SNU2108 | 1 |

| VI | N323D, E347K, M354K, G365D | SNU5079, SNU5082, SNU5084, SNU5085, SNU5100 | 5 |

TABLE 3.

Frequency of variant NDVs in different hosts at different periods

| Period (yr) | Frequency of variant NDVs (% [no. of positive isolates/no. of isolates tested])a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broiler | Layer/breeder | Others | Total for period | |

| 2000-2001 | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/7) | 0 (0/1) | 0 (0/16) |

| 2002 | 8.3 (1/12) A | 75.0 (3/4) A | 0.0 (0/3) | 21.1 (4/19) B |

| 2003-2006 | 83.3 (5/6) | 81.8 (9/11) | 100 (4/4) | 85.7 (18/21) B |

| Total | 23.0 (6/26) | 54.5 (12/22) | 50.0 (4/8) | 39.3 (22/56) |

A variant type must possess at least the E347K mutation. The same letter is placed next to values to indicate that the frequencies between two groups are different significantly (P < 0.05).

FIG. 1.

Three-dimensional locations of variable amino acids in the linear epitope and its flanking regions in HN. (A) Top view of HN. (B) Variable region flanking the linear epitope (residues 345 to 353). The linear epitope is represented in white, except 347K and 354K, which are shown in red. The variable residues at positions 323, 360, 362, and 365 are shown in yellow.

The causes of vaccine breakdown can be explained by vaccine quality (mainly antigen content), immune suppression of the host, and/or antigenic variation of NDV (16, 21, 31). Out of the 54 ND cases for which information on vaccination was available, 90.7% had a history of vaccination, and 44.4% of ND cases were diagnosed from the flocks that had been vaccinated more than two times against NDV (data not shown). Layers and breeders are usually vaccinated more intensively than broilers; therefore, the frequencies of variant NDVs possessing the E347K mutation in different types of chickens (broilers versus layers/breeders) and at different periods were compared. The frequency of variant NDVs in layers/breeders (75.0%) was significantly higher than that of broilers (8.3%) in 2002 (P < 0.05), and the frequency of variant NDVs in 2002 (21.1%) increased significantly from 2003 to 2006 (85.7%; P < 0.05) without a difference between types of chickens (Table 3). The predominance of the linear epitope mutant with time is not restricted to the subgenotype VIId. For Korean genotype VI NDVs, the E347K mutation was first identified in 1993, but all five genotype VI NDVs (GenBank accession nos. EF544061, EF544062, and EF544063) isolated from 1994 to 1999 harbored the E347K mutation (11). Therefore, antigenic selection under intensive vaccine immunity is the likely scenario. Although commercial vaccines have been considered to be protective against mortality due to genotypes III, VIb, VIg, VIId, and IX, genotype VIIc was reported to be an antigenic variant that escapes the immune response of the vaccine (30). The complete nucleotide sequences of the F and HN genes of SNU0202, KBNP-4152, SNU5070, and SNU5074 were determined, and their amino acid sequences were compared to investigate other amino acid changes relevant to antigenic variations of F and HN proteins. The ranges of amino acid similarities of F and HN proteins were 98.9% to 99.6% and 97.2% to 99.8%, respectively, but there are no known amino acid changes related to antigenic variation of conformational epitopes in F and HN proteins (5, 7-9, 22, 28). Interestingly, the frequency of synonymous amino acid changes in the F protein (4.2%, or 23/553) was similar to that of HN protein (4.4%, or 25/571), but there were significantly fewer nonsynonymous amino acid changes in the F protein (1.7%, or 9/553) than in the HN protein (3.5%, or 20/571) among the viruses compared (P < 0.05). Therefore, the increased variability of HN protein relative to F protein has also been inherited in subgenotype VIId viruses (20). The high antigenic variability of HN protein compared to F protein may reflect the immunologic pressure and resulting selection of the variant HN protein and less structure-function restriction (4, 20).

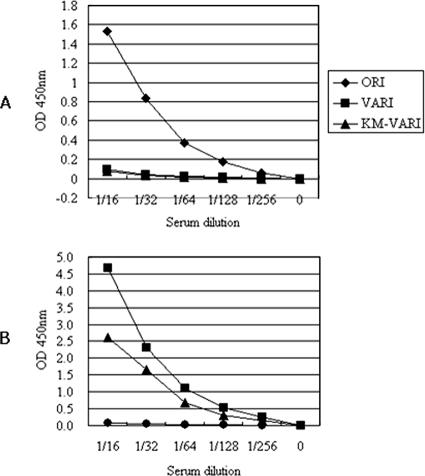

Our ELISA results demonstrate that anti-La Sota chicken antiserum reacts less strongly to synthetic oligopeptide analogues of linear epitopes of the M347K-M354K (VARI) and M347K (KM-VARI) mutants than to ORI, an analogue of the wild-type linear epitope. Anti-KBNP-4152 chicken antiserum reacted more strongly to VARI and KM-VARI than to ORI, but it was more reactive to VARI than KM-VARI (Fig. 2). The ELISA study also revealed that the linear epitope (ORI) previously identified by monoclonal antibody can also be naturally recognized by the humoral immunity of the chicken host. Therefore, it is noteworthy that some epitopes found in pathogenic microorganisms may be recognized commonly by different species of hosts as a result of long-lasting pathogen-host interaction, and evolutionary conservation of certain B-cell repertoires allows recognition of the same epitope in different hosts. The ELISA study also reveals the following: (i) the importance of E347K in antigenic variation of the wild-type linear epitope; (ii) recognition of the mutated linear epitope by humoral immunity of chickens; and (iii) antigenic difference of the E347K-M354K mutant from the E347K linear epitope mutant.

FIG. 2.

Antigenicities of the synthetic peptides. The antigenicities of the wild-type (ORI), E347K mutant (KM-VARI), and E347K-M354K mutant (VARI) peptides were assessed by ELISA employing polyclonal antibodies, anti-La Sota (A) and anti-KBNP-4152 (B) chicken antisera. OD, optical density.

In conclusion, the appearance and the increasing prevalence of the linear epitope mutants may reflect antigenic selection of field NDVs in vaccinated flocks, and the E347K mutation represents a potentially useful marker of antigenic variation of field NDVs.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of F and HN genes were deposited in the GenBank under the accession numbers EF543760 to EF543794, EF647971 to EF647995, EF544060 to EF544118, and EU140947 to EU140954.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Regional Industrial Technology Development Program of the Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Energy, and a Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2006-005-J02901).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 February 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander, D. J., J. S. Mackenzie, and P. H. Russell. 1986. Two types of Newcastle disease viruses isolated from feral birds in western Australia detected by monoclonal antibodies. Aust. Vet. J. 63365-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander, D. J., R. J. Manvell, J. P. Lowings, K. M. Frost, M. S. Collins, P. H. Russell, and J. E. Smith. 1997. Antigenic diversity and similarities detected in avian paramyxovirus type 1 (Newcastle disease virus) isolates using monoclonal antibodies. Avian Pathol. 26399-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballagi-Pordány, A., E. Wehmann, J. Herczeg, S. Belak, and B. Lomniczi. 1996. Identification and grouping of Newcastle disease virus strains by restriction site analysis of a region from the F gene. Arch. Virol. 141243-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho, S. H., S. J. Kim, and H. J. Kwon. 2007. Genomic sequence of an antigenic variant Newcastle disease virus isolated in Korea. Virus Genes. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0078-z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Gotoh, B., T. Sakaguchi, K. Nishikawa, N. M. Inocencio, M. Hamaguchi, T. Toyoda, and Y. Nagai. 1988. Structural features unique to each of the three antigenic sites on the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein of Newcastle disease virus. Virology 163174-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guex, N., and M. C. Peitsch. 1997. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 182714-2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herczeg, J., E. Wehmann, R. R. Bragg, P. M. Travassos Dias, G. Hadjiev, O. Werner, and B. Lomniczi. 1999. Two novel genetic groups (VIIb and VIII) responsible for recent Newcastle disease outbreaks in Southern Africa, one (VIIb) of which reached Southern Europe. Arch. Virol. 1442087-2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iorio, R. M., J. B. Borgman, R. L. Glickman, and M. A. Bratt. 1986. Genetic variation within a neutralizing domain on the haemagglutinin-neuraminidase glycoprotein of Newcastle disease virus. J. Gen. Virol. 671393-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iorio, R. M., R. L. Glickman, A. M. Riel, J. P. Sheehan, and M. A. Bratt. 1989. Functional and neutralization profile of seven overlapping antigenic sites on the HN glycoprotein of Newcastle disease virus: monoclonal antibodies to some sites prevent viral attachment. Virus Res. 13245-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and N. Masatoshi. 2004. MEGA3: Integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon, H. J. 2000. Molecular characterization of fusion and hemagglutinin-neuraminidase genes of Newcastle disease virus. Ph.D. thesis. Seoul National University, Seoul, South Korea.

- 12.Kwon, H. J., S. H. Cho, Y. J. Ahn, S. H. Seo, K. S. Choi, and S. J. Kim. 2003. Molecular epidemiology of Newcastle disease in Republic of Korea. Vet. Microbiol. 9539-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee, Y. J., H. W. Sung, J. G. Choi, J. H. Kim, and C. S. Song. 2004. Molecular epidemiology of Newcastle disease viruses isolated in South Korea using sequencing of the fusion protein cleavage site region and phylogenetic relationships. Avian Pathol. 33482-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, X. F., H. Q. Wan, X. X. Ni, Y. T. Wu, and W. B. Liu. 2003. Pathotypical and genotypical characterization of strains of Newcastle disease virus isolated from outbreaks in chicken and goose flocks in some regions of China during 1985-2001. Arch. Virol. 1481387-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lomniczi, B., E. Wehmann, J. Herczeg, A. Ballagi-Pordány, E. F. Kaleta, O. Werner, G. Meulemans, P. H. Jorgensen, A. P. Mante, A. L. J. Gielkens, I. Capua, and J. Damoser. 1998. Newcastle disease outbreaks in recent years in Western Europe were caused by an old (VI) and a novel genotype (VII). Arch. Virol. 14349-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maas, R. A., M. Komen, M. van Diepen, H. L. Oei, and I. J. T. M. Claassen. 2003. Correlation of haemagglutinin-neuraminidase and fusion protein content with protective antibody response after immunisation with inactivated Newcastle disease vaccines. Vaccine 213137-3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mase, M., K. Imai, Y. Sanada, N. Sanada, N. Yuasa, T. Imada, K. Tsukamoto, and S. Yamaguchi. 2002. Phylogenetic analysis of Newcastle disease virus genotypes isolated in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 403826-3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayo, M. A. 2002. Virus taxonomy—Houston 2002. Arch. Virol. 1471071-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayo, M. A. 2002b. A summary of taxonomic changes recently approved by ICTV. Arch. Virol. 1471655-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison, T., and A. Portner. 1991. Structure, function, and intracellular processing of the glycoproteins of Paramyxoviridae, p. 347-482. In D. W. Kingsbury (ed.), The paramyxoviruses. Plenum Press, New York, NY.

- 21.Nakamura, T., Y. Otaki, and T. Nunoya. 1992. Immunosuppressive effect of a highly virulent infectious bursal disease virus isolated in Japan. Avian Dis. 36891-896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neyt, C., J. Geliebter, M. Slaoui, D. Morales, G. Meulemans, and A. Burny. 1989. Mutations located on both F1 and F2 subunits of the Newcastle disease virus fusion protein confer resistance to neutralization with monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 63952-954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pyun, J. C., M. Y. Cheong, S. H. Park, H. Y. Kim, and J. S. Park. 1997. Modification of short peptides using epsilon-aminocaproic acid for improved coating efficiency in indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). J. Immunol. Methods 208141-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roy, P., A. T. Venugopalan, and A. Koteeswaran. 2000. Antigenetically unusual Newcastle disease virus from racing pigeons in India. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 32183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell, P. H., and D. J. Alexander. 1983. Antigenic variation of Newcastle disease virus strains detected by monoclonal antibodies. Arch. Virol. 75243-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scanlon, D. B., G. L. Corino, B. J. Shiell, A. J. Ellla-Porta, R. J. Manvell, D. J. Alexander, A. N. Hodder, and J. J. Gorman. 1999. Pathotyping isolates of Newcastle disease virus using antipeptide antibodies to pathotype-specific regions of their fusion and hemagglutinin-neuraminidase proteins. Arch. Virol. 14455-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwede, T., J. Kopp, N. Guex, and M. C. Peitsch. 2003. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 313381-3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toyoda, T., B. Gotoh, T. Sakaguchi, H. Kida, and Y. Nagai. 1988. Identification of amino acids relevant to three antigenic determinants on the fusion protein of Newcastle disease virus that are involved infusion inhibition and neutralization. J. Virol. 624427-4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang, C. Y., H. K. Shieh, Y. L. Lin, and P. C. Chang. 1999. Newcastle disease virus isolated from recent outbreaks in Taiwan phylogenetically related to viruses (genotype VII) from recent outbreaks in Western Europe. Avian Dis. 43125-130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu, L., Z. Wang, Y. Jiang, L. Chang, and J. Kwang. 2001. Characterization of newly emerging Newcastle disease virus isolates from the People's Republic of China and Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 393512-3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yusoff, K., M. Nesbit, H. McCartney, G. Meulemans, D. J. Alexander, M. S. Collins, P. T. Emmerson, and A. C. Samson. 1989. Location of neutralizing epitopes on the fusion protein of Newcastle disease virus strain Beaudette C. J. Gen. Virol. 703105-3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]