Abstract

Vpu (viral protein U) is a 17-kDa human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) accessory protein that enhances the release of particles from the surfaces of infected cells. Vpu recruits β-transducin repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP) and mediates proteasomal degradation of CD4. By sequestering β-TrCP away from other cellular substrates, Vpu leads to the stabilization of β-TrCP substrates such as β-catenin, IκBα, ATF4, and Cdc25A, but not of other substrates such as Emi1. This study shows that in addition to stabilizing β-catenin, Vpu leads to the depression of both total and β-catenin-associated E-cadherin levels through β-TrCP-dependent stabilization of the transcriptional repressor Snail. We showed that both downregulation of overall E-cadherin levels and dissociation of E-cadherin from β-catenin result in enhanced viral release. By contrast, the overexpression of E-cadherin or the prevention of the dissociation of E-cadherin from β-catenin results in depressed levels of virus release. Since E-cadherin is expressed only in dendritic cells and macrophages, and not in T cells, our data suggest that the HIV-1 vpu gene may have evolved to counteract different restrictions to assembly in different cells.

Vpu (viral protein U) is an 81-amino-acid type I integral membrane protein expressed by human deficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and several simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs), including SIVcpz, SIVgsn, SIVmus, and SIVmon, but not expressed by HIV-2 or other SIVs. Vpu is not incorporated into HIV-1 virions (13-16, 22, 55). Although dispensable for HIV replication in vitro, the Vpu open reading frame is conserved in infected patients, and it is required for efficient replication of chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses in macaques, indicating that it has a critical role in pathogenesis (54, 66).

One of the best-defined functions of Vpu is the enhancement of viral particle release from the surfaces of infected cells in a cell-type-dependent manner that occurs only in human T-lymphocyte, macrophage, HeLa, and 293T cells (17, 21, 24, 47). In African green monkey kidney COS cells, viral budding occurs independently of Vpu (45, 59). The primary domain of Vpu associated with this function is the N-terminal 27-amino-acid transmembrane region that inserts into intracellular and plasma membranes (4, 43, 60). Randomization of the amino acid sequence of the N-terminal domain of Vpu diminishes the ability of Vpu to enhance virus release (46). While the N-terminal domain is the principal region responsible for enhanced particle release, viruses expressing only the N-terminal region of Vpu are unable to achieve wild-type levels of particle release, indicating that other Vpu domains may also contribute to this activity (35, 47, 49). The mechanism of action through which Vpu mediates particle release remains unclear and is suspected to be due to the ability of Vpu to counteract a host cell factor specific to human cells (59). It may also depend on the ability of Vpu to interact with the potassium ion channel protein TASK (30). In addition, recent studies have shown that Vpu redirects nascent viral particles from internal membrane vesicles to the plasma membrane (27, 38).

The other well-defined function of Vpu is the degradation of CD4 complexed with gp160 in the endoplasmic reticulum, which is mediated by the C-terminal 54-amino-acid region of the protein (35, 49). This function is carried out by the binding and recruitment of the β-transducin repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP), the receptor component of the multisubunit Skp1-cullin-F box protein complex E3 ubiquitin ligase (7, 36). β-TrCP binds to Vpu after casein kinase II-mediated phosphorylation of Vpu residues 52 and 56 (48). Vpu has been shown to stabilize several β-TrCP substrates, including the adherens junction protein β-catenin, NF-κB inhibitor IκBα (nuclear factor κB), ATF4 (activating transcription factor 4), and cdc25A (cell division cycle protein 25A) (5, 20). However, other β-TrCP substrates, such as Emi-1 (early mitotic inhibitor-1), remain unaffected by Vpu (20). Of note, Vpu binding to β-TrCP does not promote its own degradation, and in fact, Vpu is degraded through a β-TrCP-independent mechanism that depends on the phosphorylation of residue 61 (20).

β-catenin has two distinct functions. It binds the transcription factors LEF (lymphoid enhancer factor) and TCF (T-cell factor) to enhance the expression of genes, including those involved in T-cell activation (42). β-catenin also links the cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin to the underlying microfilament network of the cytoskeleton, most prominently at cell confluence (18, 40). E-cadherin expression is regulated at the transcriptional level by the β-TrCP substrate Snail (9, 64). Since our previous work showed that Vpu-enhanced particle release depends on cell confluence (17), we examined whether Vpu-mediated virus release results from the modulation of β-catenin and E-cadherin levels and their interaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, transfection, and antibodies.

HeLa and 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and antibiotics (penicillin-streptomycin). Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotics (penicillin-streptomycin). Plasmid transfections were carried out using TransIT-LT1 (Mirus), and silent interfering RNA (siRNA) transfections were carried out using GeneEraser (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the single TransIT transfection experiments, the cells were transfected with 2 μg of plasmid. For the cotransfection experiments, the cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of a proviral clone and 1.5 μg of a second plasmid. The antibodies used were β-catenin (BD Transduction), E-cadherin (BD Transduction), phospho-β-catenin Ser33/Ser37/Thr41 (Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-β-catenin Thr41/Ser45 (Cell Signaling Technology), actin (Santa Cruz), HA (Sigma), FLAG (Sigma), SNA-I (Santa Cruz), Vpu (34), and HIV-1 MA (52). Jurkat cells were electroporated at 250 V, 950 μF, R10, using a BTX 600 electroporator.

Plasmids and siRNA.

Vphu, NLUdel, NLU35, and NLRd plasmids were provided by K. Strebel and S. Bour (39, 46). Wild-type β-catenin and S33Y plasmids were donated by E. R. Fearon (8). An E-cadherin expression plasmid was obtained from S. M. Troyanovsky (57). Vpu-HA was derived by attaching a single HA epitope tag to the C-terminal end of HIV-1-derived Vpu in pcDNA3.1, using PCR primers 5′-ATGCAACCTATAATAGTAGCAATAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCGAGATCTCTAAGCGTAATCTGGTACGTCGTATGGGTAGATATCCAGATCATCAATATCCC-3′ (reverse). The Vpsa plasmid was derived from Vphu by mutating the serines at 52 and 56 to alanine, using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). β-catenin siRNA was designed as described previously (61). A QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit was used to generate plasmids Y654E and Y654F from the wild-type β-catenin plasmid, using primers 5′-GAAGGTGTGGCGACAGAAGCAGCTGCTGTTTTGTTCCG-3′ (forward), 5′-CGGAACAAAACAGCAGCTGCTTCTGTCGCCACACCTTC-3′ (reverse), 5′-GAAGGTGTGGCGACATTTGCAGCTGCTGTTTTGTTCCG-3′ (forward), and 5′-CGGAACAAAACAGCAGCTGCAAATGTCGCCACACCTTC-3′ (reverse), respectively. The siRNA-resistant plasmids bcatr, Y654Er, and Y654Fr were generated using primers 5′-CAAGAACAAGTAGCTGACATAGATGGACAGTATGCAATGACTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGTCATTGCATACTGTCCATCTATGTCAGCTACTTGTTCTTG-3′ (reverse). E-cadherin siRNA was purchased from Dharmacon (On-Target plus smart pool). All plasmids were confirmed by nucleotide sequence analyses.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation.

For immunoblotting experiments, cells were seeded at a density of 0.5 × 106 per well in 6-well plates and transfected with an expression plasmid, using TransIT-LT-1. After being transfected and incubated, cells were dispersed in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate). The nuclei were pelleted, and the lysates were resuspended in 2× sample buffer (125 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 50% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and bromophenol blue), boiled for 5 min, and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and immunoblotting. For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates prepared in lysis buffer were incubated on a rotator with mouse anti-β-catenin immunoglobulin G and protein G-agarose beads (Sigma) for 1 h at 4°C. Immune complexes were collected and washed three times by centrifugation with lysis buffer. The immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Imaging and densitometry analyses were performed using Alpha Innotech's AlphaImager and the AlphaEaseFC version 4.0 program.

Virus release assays.

The levels of virus released were determined by centrifugating the cell cultured, conditioned media through a 20% sucrose cushion at 45,000 rpm for 45 min in an SW55Ti rotor (Beckman), resuspending the pellets in sample buffer. The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, using anti-MA antibody.

RESULTS

Vpu expression results in β-catenin stabilization and alters HIV-1 release.

It is now well established that Vpu mediates stabilization of β-catenin in HeLa and 293T cells (3, 20). In this study, we examined the effects of Vpu on β-catenin in Jurkat 25 T cells electroporated with an HA-tagged Vpu expression plasmid (Fig. 1A). The level of β-catenin, as measured by immunoblotting and densitometric band analysis, was elevated by 2.3-fold (standard error, ±0.3; P < 0.01, as determined by 2-tailed t testing of the paired samples) in both Jurkat and HeLa cells in the presence of Vpu compared to that in the absence of Vpu.

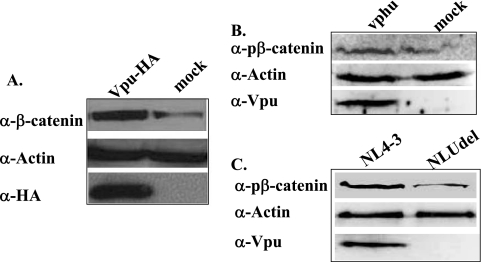

FIG. 1.

Vpu expression results in β-catenin stabilization. (A) Jurkat cells were electroporated with 10 μg of a Vpu-HA expression plasmid or an empty pcDNA vector (mock). At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested, subjected to electrophoresis, and immunoblotted with anti-β-catenin (upper panel), anti-actin (middle panel), or anti-HA antibodies (lower panel). The experiment was repeated twice in Jurkat cells and once in 293T cells, with similar results (data not shown). (B) 293T cells were transfected with pcDNA or an optimized Vpu expression plasmid (vphu), and after 24 h, immunoblotting was performed with an anti-phospho-β-catenin (α-pβ-catenin) antibody that recognizes the phosphorylation of residues 41 and 45 (top panel). Vpu expression was measured by immunoblotting with an antibody against Vpu (lower panel). The experiment was performed twice with similar results. (C) 293T cells were transfected with NL4-3 or NLUdel, and immunoblotting was performed as for panel B. α, anti.

In the absence of Wnt signaling, β-catenin is constitutively phosphorylated at serines 33, 37, 45 and at threonine 41 by glycogen synthase kinase 3β, resulting in β-TrCP-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation (1, 41, 44, 56). Immunoblot analysis was carried out on lysates of 293T cells transfected with a codon-optimized Vpu construct (Vphu) with NL4-3, an infectious molecular HIV-1 clone which expresses full-length Vpu, or with NLUdel, a proviral clone with a Vpu deletion in the NL4-3 background (39, 46). The levels of phospho-β-catenin were measured with an antibody that specifically recognizes phosphorylation at the Ser45 and Thr41 sites. The levels of phospho-β-catenin were elevated in the presence, but not in the absence, of Vpu (Fig. 1B and C). Similar results were found in Jurkat 25 cells, with an antibody to β-catenin phosphorylated at sites 33, 37, and 41 (data not shown). Since β-TrCP mediates specific degradation of phosphorylated β-catenin (28), this result is consistent with the decreased turnover of β-catenin. Furthermore, this result is in line with the previous demonstration that Vpu sequesters β-TrCP away from its natural substrates (3, 5). Thus, similar effects of Vpu on β-catenin stability were seen in three different cell lines, with antibodies to all four N-terminal phosphorylation sites of β-catenin, with three different Vpu expression plasmids, with or without epitope tags, and with or without the expression of other HIV-1 proteins.

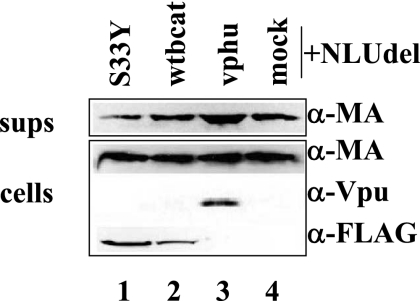

To examine the effects of β-catenin on virus release, NLUdel was cotransfected into HeLa cells with expression plasmids for FLAG-tagged β-catenin or a stable β-catenin mutant, S33Y, which is resistant to degradation (Fig. 2) (44). As a control, Vphu was also cotransfected with NLUdel (39). At 48 h posttransfection, viral protein expression was measured by immunoblotting cell lysates with antibodies to Gag MA and Vpu. The levels of virus release were assessed by immunoblotting culture supernatants with the antibody to MA. Vpu expression resulted in a 2.1-fold-enhanced level of virus release (standard error, ±0.3; P < 0.05) (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4). This result is in agreement with the previously reported effects of Vpu on the levels of particle release, as several studies have found Vpu effects to be variable depending on the cell type, with as low as a twofold-enhanced level of virus release (2, 47, 49). The expression of exogenous wild-type β-catenin had no significant effect on virus release (1.06-fold ± 0.3) (Fig. 2, lanes 2 and 4). However, the level of exogenously expressed wild-type β-catenin was found not to be significantly higher than endogenous levels. In contrast, expression of the stable form of β-catenin, the S33Y β-catenin mutant, reduced virus release by 3.6-fold (±0.02; P < 0.01) (Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 4). Note that overall β-catenin levels were found to be increased by 1.5-fold in S33Y-transfected cells compared to that in mock-transfected cells. The levels of Gag in the cell lysates were not affected (0.97-fold ± 0.1). Similar results were seen when NL4-3 was cotransfected with wild-type β-catenin and with S33Y, indicating that the effect of stabilized β-catenin is dominant over that of Vpu (data not shown). In addition, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to determine p24 antigen levels and was found to give similar results to that of the immunoblot analysis (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

HIV-1 budding is regulated by β-catenin. NLUdel was cotransfected into HeLa cells with empty pcDNA vector (mock), with optimized Vpu (vphu), or with a wild-type or S33Y FLAG-tagged β-catenin expression plasmid (wtbcat and S33Y, respectively). After 24 h, equivalent amounts of the supernatants (sups) and cell extracts (cells) were analyzed by immunoblotting, using an anti-MA polyclonal antibody (α-MA; top two panels) or an anti-Vpu polyclonal antibody (α-Vpu; panel 3) or anti-FLAG (α-FLAG; panel 4) monoclonal antibody. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Thus, stabilized β-catenin leads to decreased virus particle release. However, Vpu stabilizes β-catenin and increases virus particle release. To explain this apparent conflict, the effects of Vpu on β-catenin-interactive proteins were also examined.

Vpu reduces the β-catenin interaction with E-cadherin.

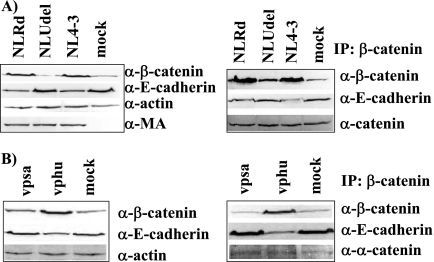

HeLa cells were transfected with NL4-3 and NLUdel (Fig. 3). At 24 h posttransfection, immunoblotting for β-catenin, E-cadherin, MA, and actin was performed on the total cell lysates (Fig. 3A, left panel). As expected, in the presence of NL4-3, we found increased levels of β-catenin. Furthermore, we observed that in the presence of NL4-3, E-cadherin levels were decreased by 3.7-fold (±0.7). Immunoprecipitation with a β-catenin antibody was carried out on cell lysates to determine the specific effects of Vpu on the β-catenin interaction with E-cadherin (Fig. 3A, right panel). In the presence of NL4-3, the levels of E-cadherin associated with β-catenin were also decreased by 3.6-fold (±1.03). The levels of α-catenin were not affected, indicating that there is a specific dissociation of β-catenin from E-cadherin and not an overall disruption of the adherens complex.

FIG. 3.

Expression of the Vpu C-terminal domain results in reduced association of E-cadherin with β-catenin. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with NL4-3, NLUdel, NLRd, or an empty vector (mock). The left panel shows immunoblots of the cell extracts, and the right panel shows cell extracts immunoprecipitated with an anti-β-catenin antibody prior to immunoblotting. The experiment was repeated four times. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with Vphu (vphu), mutant vpsa, with Ser residues 52 and 56 mutated to alanine, or an empty vector. The left and right panels show immunoblots of the cell extracts and anti-β-catenin antibody immunoprecipitates, respectively. The experiment was repeated three times. α, anti; IP, immunoprecipitates.

Transfection of NLRd, which expresses a mutant Vpu with a randomized transmembrane domain, but which contains an intact C-terminal domain (46), also resulted in a decrease in E-cadherin levels by 5.1-fold (±1.5) (Fig. 3A). In contrast, cells transfected with NLU35, which expresses a mutant Vpu truncated after residue 35, exhibited no effects on E-cadherin or β-catenin-associated E-cadherin levels (data not shown) (46).

We further confirmed these results by transfecting cells with the Vphu expression plasmid and found that both total and β-catenin-associated E-cadherin levels were reduced, by 2.7-fold (±0.8) and 4.0-fold (±0.8), respectively (Fig. 3B). The cytoplasmic DSGXXS phosphorylation motif of Vpu has been shown to mediate interactions with β-TrCP (36, 46). We found that cells transfected with Vpsa, a plasmid expressing codon-optimized Vpu with the serines of the phosphorylation motif mutated to alanines, demonstrated no alteration of total or β-catenin-associated E-cadherin levels. This indicates that the C-terminal domain of Vpu, and specifically the β-TrCP-interacting motif of Vpu, is responsible for reduced E-cadherin levels.

Snail is a zinc finger transcriptional factor known to be regulated by β-TrCP and to repress E-cadherin expression (9, 64). We examined Snail levels in Vpu-transfected HeLa cells (Fig. 4A, 4B). Snail levels were found to be upregulated in both Vphu- and NL4-3-transfected cells. NLUdel-transfected cells did not show an upregulation of Snail levels, indicating that other HIV-1 proteins are not involved in this process. We also performed real time reverse transcription-PCR analysis and found a 5.7-fold decrease in E-cadherin mRNA levels in Vphu-transfected HeLa cells compared to that in mock-transfected cells, confirming that the depression of E-cadherin levels was due to Snail-mediated transcriptional repression.

FIG. 4.

Vpu expression results in increased Snail levels. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with either an empty vector (mock) or Vphu (vphu). At 24 h posttransfection, the cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with either an empty vector, NLUdel, or NL4-3. At 24 h posttransfection, the cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. α, anti.

The dissociation of β-catenin and E-cadherin complexes results in enhanced particle release.

In order to examine the functional consequences of the downregulation of E-cadherin, we first determined the effects of downregulating the overall levels of E-cadherin on virus particle release. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA against E-cadherin or with luciferase siRNA as a control (Fig. 5A). At 24 h posttransfection with siRNA, the cells were transfected with NLUdel, and after an additional 24 h, the cell lysates and supernatants were harvested and subjected to immunoblot analysis. In the presence of siRNA against E-cadherin, the level of E-cadherin was found to be downregulated by 4-fold and virus release upregulated by 2.1-fold, as determined by densitometric analysis of the bands (Fig. 5A). The levels of β-catenin and actin were not affected. Thus, a specific reduction in the total levels of E-cadherin leads to an increase in virus particle release.

FIG. 5.

Effect of E-cadherin on HIV-1 particle release. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with 20 nM of siRNA against E-cadherin or with luciferase siRNA as a control. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were transfected with NLUdel. After an additional 24 h, the supernatants (sups) and cells were collected and analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody to MA (first and fifth panels), E-cadherin (second panel), β-catenin (third panel), or actin (fourth panel). (B) 293T cells were cotransfected with a proviral clone, either NL4-3 or NLUdel, and with an empty vector (mock) or E-cadherin expression plasmid. At 48 h posttransfection, the cell lysates and supernatants were harvested and analyzed by immunoblotting. α, anti.

When NL4-3 was transfected into cells expressing reduced levels of E-cadherin, the effect on particle release was less marked than that seen with NLUdel (data not shown). Thus, Vpu-mediated downregulation of E-cadherin is sufficient to increase particle release, and further downregulation of E-cadherin levels with siRNA did not result in additive effects on virus release.

We also determined the effect of the overexpression of E-cadherin on virus release. Vpu was found to have effects on E-cadherin downregulation in 293T cells similar to those described above for HeLa cells (Fig. 5B). 293T cells were cotransfected with a proviral vector, either NL4-3 or NLUdel, and either an empty cytomegalovirus promoter expression vector or a cytomegalovirus-E-cadherin expression vector (53). At 48 h posttransfection, the cells and supernatants were analyzed for Gag expression. In the presence of overexpressed E-cadherin, reduced levels of the virus were released into the supernatant from both NL4-3- and NLUdel-transfected cells (Fig. 5B).

Vpu has been shown to overcome a dominant restriction to assembly in human cells (59). COS cells do not have this restriction to assembly. Varthakavi and colleagues showed that while human-African green monkey cell heterokaryons show reduced levels of Gag release, the expression of Vpu in these heterokaryons can overcome the defect (59). We found that in COS cells, E-cadherin could not be detected with the human α-E-cadherin antibody. Therefore, we tested whether E-cadherin could be the dominant restriction factor to virus assembly by overexpressing human E-cadherin with or without Vpu in COS cells. We found that overexpression of human E-cadherin in COS cells did not have an effect on either NL4-3 or NLUdel release, indicating that E-cadherin is not the restriction factor that is overcome by Vpu (data not shown).

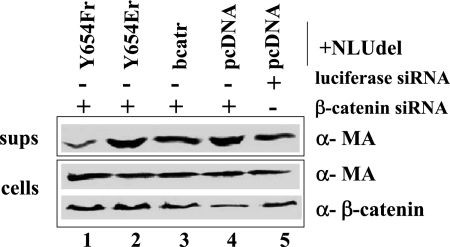

In order to specifically examine the functional effect on particle release of the β-catenin interaction with E-cadherin, we first reduced endogenous β-catenin levels in HeLa cells by using siRNA. The level of β-catenin was found to be reduced by 2.8-fold with siRNA against β-catenin compared to the control siRNA against luciferase (±0.5) (Fig. 6, lanes 4 and 5). At 24 h posttransfection with siRNA, the cells were transfected with NLUdel and an empty vector. This resulted in an 1.8-fold (±0.4; P < 0.03)-increased level of virus release, as measured by densitometry after an additional 24 h, compared to that for cells transfected with control siRNA against luciferase (Fig. 6, lanes 4 and 5). Plasmids were cotransfected with NLUdel into siRNA-expressing HeLa cells to express siRNA-resistant forms of β-catenin or β-catenin mutated at residue Y654. Y654Er is an siRNA-resistant β-catenin mutant unable to associate with E-cadherin (Fig. 6, lane 2), whereas Y654Fr is an siRNA-resistant β-catenin that remains constitutively associated with E-cadherin (Fig. 6, lane 1) (31). Y654Er had little effect on virus release compared to that in pcDNA-transfected cells (1.2-fold) (Fig. 6, lanes 2 and 4), whereas Y654Fr resulted in a 3.8-fold decrease in virus release (±0.7; P < 0.03) (Fig. 6, lanes 1 and 4). Thus, when β-catenin could not dissociate from E-cadherin, we found a decrease in the levels of virus release. However, in the presence of a β-catenin mutant that cannot associate with E-cadherin, the levels of virus release were comparable to that seen with siRNA against β-catenin; i.e., we found an increase in virus release compared to that for cells expressing control siRNA.

FIG. 6.

Dissociation of E-cadherin and β-catenin leads to increased HIV-1 particle release. HeLa cells were transfected with 50 nM of siRNA against β-catenin or luciferase. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were transfected with NLUdel and either pcDNA or an expression plasmid for an siRNA-resistant form of wild-type β-catenin (bcatr) or mutant β-catenin (Y654Er or Y654Fr). After an additional 24 h, the supernatants (sups) and cells were collected and analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-MA (top two panels) or anti-β-catenin antibody (bottom panel). The experiment was repeated three times. α, anti.

DISCUSSION

There appear to be two distinct effects of Vpu on β-catenin and E-cadherin. While the C-terminal region of Vpu stabilizes β-catenin, this domain also results in downregulation of E-cadherin. Our current work on β-catenin stabilization extends previous work, demonstrating similar effects in T-cells (3). In addition, our work highlights the functional consequences of β-catenin stabilization by showing that in the presence of stabilized β-catenin, there is a reduced level of virus particle release.

We observed that HeLa cells transfected with NL4-3 show a sevenfold increase in the level of virus release compared to that for cells transfected with NLUdel as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (data not shown). NLRd-transfected cells have levels of virus release comparable to those of NLUdel. However, NLU35-transfected cells show a 30% reduction in the levels of virus release compared to that for the wild type, indicating that the C-terminal domain also plays a role in virus release, albeit a smaller one. This finding is consistent with previous reports that show similar results with Vpu C-terminal mutants (46, 47).

One point of interest is that we found increased levels of N-terminally phosphorylated β-catenin in the presence of Vpu, which is consistent with a reduced turnover of β-catenin. Previous studies have shown that β-catenin-mediated coactivation of LEF/TCF transcription factors cannot be mediated by β-catenin phosphorylated at the N terminus (44, 53). However, the Besnard-Guerin study showed that Vpu-mediated stabilization of β-catenin results in enhanced TCF activity (3). Therefore, further investigation is required to determine how phosphorylated β-catenin generated by Vpu can mediate this function. It may be explained by differences in the cell types used in each study. In addition, our study shows that cotransfection of a proviral clone with the stabilized S33Y mutant of β-catenin leads to depressed levels of particle release. One hypothesis to explain this result is that there may be greater numbers of complexes of E-cadherin associated with β-catenin in the presence of S33Y. This is consistent with the finding of Sadot and coworkers, who showed that phosphorylated β-catenin is present in newly formed β-catenin/E-cadherin complexes (44).

We also showed that Vpu mediates the downregulation of both the total levels of E-cadherin and the levels of E-cadherin associated with β-catenin. This effect is caused by Vpu-mediated sequestration of β-TrCP, resulting in upregulation of the transcriptional repressor Snail. We have previously shown that the effects of Vpu on particle release depend on cell confluence (17). Since complexes of β-catenin associated with E-cadherin are more apparent at higher levels of cell confluence, we determined the effect of Vpu on the β-catenin interaction with E-cadherin at different cell densities. We found that while Vpu-mediated dissociation of E-cadherin from β-catenin was not apparent at a 25% confluence, there was dissociation at a 75% confluence in Vpu-expressing 293T cells (data not shown). Thus, the effect of Vpu appears to be larger at higher levels of cell confluence, where there are a larger number of mature E-cadherin/β-catenin complexes.

Cell-to-cell transmission of HIV requires a functional host cell cytoskeleton and the polarization of both host and viral components with the cytoskeletal machinery (32). The interaction of viral proteins with cell junction components has been shown to facilitate the transmission of herpes simplex virus between adjacent cells, and disruption of the adherens junctions has been shown to liberate the receptor for various viruses, including herpes simplex virus and pseudorabies virus, and contribute to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and hepatitis B virus tumorigenesis (10, 19, 29, 65). E-cadherin is anchored to the actin cytoskeleton via the complex it forms with β-catenin (63). Since the disruption of β-catenin and E-cadherin complexes results in enhanced particle release, we hypothesize that disruption of the underlying cytoskeletal α-catenin-actin complex is responsible for the β-TrCP-dependent effects of Vpu in enhancing virus release (12). Furthermore, both the gp41 transmembrane envelope domain and HIV-1 coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 interact with α-catenin, though their relative contributions to virus budding require further investigation (11, 33, 51).

It is interesting that β-catenin is also stabilized by other viral proteins, including EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1), LMP2A, and hepatitis B virus X protein (10, 29). Several viral proteins also downregulate E-cadherin expression, including EBV LMP1 (58).

Since T cells have little E-cadherin, Vpu can promote assembly independently of the β-catenin interaction with E-cadherin (26). However, there are high levels of E-cadherin in macrophages and dendritic cells, in which these effects of Vpu are likely to be important for pathogenesis (6, 23, 25, 37, 62). It has been reported that Vpu can mediate up to a 1,000-fold enhancement of particle release levels in macrophages (2, 17). Langerhans cells (LC) express high levels of E-cadherin, which is important for mediating the adhesion of LC to keratinocytes. It is hypothesized that the downregulation of E-cadherin in LC is essential for their mobilization from the epidermis to lymph nodes, where they can then interact with T cells (50). Thus, Vpu-mediated downregulation of E-cadherin may have pathological consequences via the mobilization of infected LC in the periphery. Therefore, Vpu may have evolved to overcome different restrictions and carry out different functions in different cells. It is necessary to investigate the contributions mediated by the N- and C-terminal domains of Vpu on E-cadherin levels and virus release in each of these cell types.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

After the present paper was accepted, Kumar et al. reported that β-catenin signaling inhibits HIV replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (A. Kumar, A. Zloza, R. T. Moon, J. Watts, A. R. Tenorio, and L. Al-Harthi, J. Virol. 82:2813-2820, 2008), and Neil et al. reported that tetherin inhibits retrovirus release and is antagonized by Vpu (S. J. Neil, T. Zang, and P. D. Bieniasz, Nature 451:425-430, 2008).

Acknowledgments

We thank E. R. Fearon, S. M. Troyanovsky, K. Strebel, and S. Bour for generous provisions of plasmids and N. Campbell, D. Rauch, H. W. Virgin, A. Pekosz, W. A. Swat, and G. D. Longmore for critical reviews of the manuscript.

This study was supported by PHS grant AI24745.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 February 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amit, S., A. Hatzubai, Y. Birman, J. S. Andersen, E. Ben-Shushan, M. Mann, Y. Ben-Neriah, and I. Alkalay. 2002. Axin-mediated CKI phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser 45: a molecular switch for the Wnt pathway. Genes Dev. 161066-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balliet, J. W., D. L. Kolson, G. Eiger, F. M. Kim, K. A. McGann, A. Srinivasan, and R. Collman. 1994. Distinct effects in primary macrophages and lymphocytes of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 accessory genes vpr, vpu, and nef: mutational analysis of a primary HIV-1 isolate. Virology 200623-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besnard-Guerin, C., N. Balaïdouni, I. Lassot, E. Segeeral, A. Jobart, C. Marchal, and R. Benarous. 2004. HIV-1 Vpu sequesters β-transducin repeat-containing protein (βTrCP) in the cytoplasm and provokes the accumulation of β-catenin and other SCFβTrCP substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 279788-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binette, J., M. Dube, J. Mercier, and E. A. Cohen. 2007. Requirements for the selective degradation of CD4 receptor molecules by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein in the endoplasmic reticulum. Retrovirology 475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bour, S., C. Perrin, H. Akari, and K. Strebel. 2001. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein inhibits NF-κB activation by interfering with βTrCP-mediated degradation of IκB. J. Biol. Chem. 27615920-15928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burleigh, L., P.-Y. Lozach, C. Schiffer, I. Staropoli, V. Pezo, F. Porrot, B. Cangque, J.-L. Virelizier, F. Arenzana-Seisdedos, and A. Amara. 2006. Infection of dendritic cells (DCs), not DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of human immunodeficiency virus, is required for long-term transfer of virus to T cells. J. Virol. 802949-2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butticaz, C., O. Michielin, J. Wyniger, A. Telenti, and S. Rothenberger. 2007. Silencing of both β-TrCP1 and HOS (β-TrCP2) is required to suppress human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu-mediated CD4 down-modulation. J. Virol. 811502-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caca, K., F. T. Kolligs, X. Ji, M. Hayes, J.-M. Qian, A. Yahanda, D. L. Rimm, J. Costa, and E. R. Fearon. 1999. β- and γ-catenin mutations, but not E-cadherin inactivation, underlie T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor transcriptional deregulation in gastric and pancreatic cancer. Cell Growth Differ. 10369-376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cano, A., M. A. Pérez-Moreno, I. Rodrigo, A. Locascio, M. J. Blanco, M. G. del Barrio, F. Portillo, and M. A. Nieto. 2000. The transcription factor Snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 276-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cha, M. Y., C. M. Kim, Y. M. Park, and W. S. Ryu. 2004. Hepatitis B virus X protein is essential for the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in hepatoma cells. Hepatology 391683-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan, W.-E., and S.-L. Chen. 2006. Downregulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag expression by a gp41 cytoplasmic domain fusion protein. Virology 348418-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, C., O. A. Weisz, D. B. Stolz, S. C. Watkins, and R. C. Montelaro. 2004. Differential effects of actin cytoskeleton dynamics on equine infectious anemia virus particle production. J. Virol. 78882-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen, E. A., R. A. Subbramanian, and H. G. Gottlinger. 1996. Role of auxiliary proteins in retroviral morphogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 214219-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Courgnaud, V., B. Abela, X. Pourrut, E. Mpoudi-Ngole, S. Loul, E. Delaporte, and M. Peeters. 2003. Identification of a new simian immunodeficiency virus lineage with a vpu gene present among different Cercopithecus monkeys (C. mona, C. cephus, and C. nictitans) from Cameroon. J. Virol. 7712523-12534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Courgnaud, V., M. Salemi, X. Pourrut, E. Mpoudi-Ngole, B. Abela, P. Auzel, F. Bibollet-Ruche, B. Hahn, A.-M. Vandamme, E. Delaporte, and M. Peeters. 2002. Characterization of a novel simian immunodeficiency virus with a vpu gene from greater spot-nosed monkeys (Cercopithecus nictitans) provides new insights into simian/human immunodeficiency virus phylogeny. J. Virol. 768298-8309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dazza, M. C., M. Ekwalanga, M. Nende, K. B. Shamamba, P. Bitshi, D. Parskevis, and S. Saragosti. 2005. Characterization of a novel vpu-harboring simian immunodeficiency virus from a Dent's Mona monkey (Cercopithecus mona denti). J. Virol. 798560-8571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deora, A., and L. Ratner. 2001. Viral protein U (Vpu)-mediated enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particle release depends on the rate of cellular proliferation. J. Virol. 756714-6718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietrich, C., J. Scherwat, D. Faust, and F. Oesch. 2002. Subcellular localization of β-catenin is regulated by cell density. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292195-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dingwell, K. S., and D. C. Johnson. 1998. The herpes simplex virus gE-gI complex facilitates cell-to-cell spread and binds to components of cell junctions. J. Virol. 728933-8942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estrabaud, E., E. LeRouzic, S. Lopez-Vergès, M. Morel, N. Belaïdouni, R. Benarous, C. Transy, C. Berlioz-Torrent, and F. Margottin-Goguet. 2007. Regulated degradation of the HIV-1 Vpu protein through a βTrCP-independent pathway limits the release of viral particles. PLOS Pathog. 27e104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geraghty, R. J., K. J. Talbot, M. Callahan, W. Haper, and A. T. Panganiban. 1994. Cell type-dependence for Vpu function. J. Med. Primatol. 23146-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomez, L. M., E. Pacyniak, M. Flick, D. R. Hout, M. L. Gomez, E. Nerrienet, A. Ayouba, M. L. Santiago, B. H. Hahn, and E. B. Stephens. 2005. Vpu-mediated CD4 down-regulation and degradation is conserved among highly divergent SIVcpz strains. Virology 33546-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorry, P. R., M. Churchill, S. M. Crowe, A. L. Cunningham, and D. Gabuzda. 2005. Pathogenesis of macrophage-tropic HIV. Curr. HIV Res. 353-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gottlinger, H. G., T. Dorfman, E. A. Cohen, and W. A. Haseltine. 1993. Vpu protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enhances the release of capsid produced by the Gag gene constructs of widely divergent retroviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 907381-7385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guironnet, G., C. Dezutter-Dambuyant, C. Vincent, N. Bechetoille, D. Schmitt, and J. Péguet-Navarro. 2002. Antagonistic effects of IL-4 and TGF-β1 on Langerhans cell-related antigen expression by human monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71845-853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gumbiner, B. M. 1996. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell 84345-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hairla, K., A. Salminen, I. Prior, J. Hinkula, and M. Soumalainen. 2007. The Vpu-regulated endocytosis of HIV-1 Gag is clathrin-independent. Virology 369299-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hart, M., J.-P. Concordet, I. Lassot, I. Albert, R. del los Santos, H. Durand, C. Perret, B. Rubinfeld, F. Margottin, R. Benarous, and P. Polakis. 1999. The F-box protein β-TrCP associates with phosphorylated β-catenin and regulates its activity in the cell. Curr. Biol. 9207-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayward, S. D., J. Liu, and M. Fujimuro. 2006. Notch and Wnt signaling: mimicry and manipulation by gamma herpesviruses. Sci. STKE 335re4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Hsu, K., J. Seharaseyon, P. Dong, S. Bour, and E. Marbán. 2004. Mutual functional destruction of HIV-1 Vpu and host TASK-1 channel. Mol. Cell 14259-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu, P., E. J. O'Keefe, and D. S. Rubenstein. 2001. Tyrosine phosphorylation of human keratinocyte β-catenin and plakoglobin reversibly regulates their binding to E-cadherin and α-catenin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1171059-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jolly, C., K. Kashefi, M. Hollinshead, and Q. J. Sattentau. 2004. HIV-1 cell-to-cell transfer across an Env-induced, actin-dependent synapse. J. Exp. Med. 199283-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, E. M., K. H. Lee, and J. W. Kim. 1999. The cytoplasmic domain of HIV-1 gp41 interacts with the carboxyl-terminal region of alpha-catenin. Mol. Cell 9281-285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maldarelli, F., M. Y. Chen, R. L. Willey, and K. Strebel. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein is an oligomeric type 1 integral membrane protein. J. Virol. 675056-5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marassi, F. M., C. Ma, H. Gratkowski, S. K. Straus, K. Strebel, M. Oblatt-Montal, M. Montal, and S. J. Opella. 1999. Correlation of the structural and functional domains in the membrane protein Vpu from HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9614336-14441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Margottin, F., S. P. Bour, H. Durand, L. Selig, S. Benichou, V. Richard, D. Thomas, K. Strebel, and R. Benarous. 1998. A novel human WD protein, h-βTrCp, that interacts with HIV-1 Vpu connects CD4 to the ER degradation pathway through an F-box motif. Mol. Cell 1565-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menges, M., T. Baumeister, S. Rossner, P. Stoitzner, N. Romani, A. Gessnere, and M. B. Lutz. 2005. IL-4 supports the generation of a dendritic cell subset from murine bone marrow with altered endocytosis capacity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77535-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neil, S. J. D., S. W. Eastman, N. Jouvenet, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2006. HIV-1 Vpu promotes release and prevents endocytosis of nascent retrovirus particles from the plasma membrane. PLOS Pathog. 2354-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen, K. L., M. Ilano, H. Akari, E. Miyagi, E. M. Poeschla, K. Strebel, and S. Bour. 2004. Codon optimization of the HIV-1 vpu and vif genes stabilizes their mRNA and allows for highly efficient Rev-independent expression. Virology 319163-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozawa, H., H. Baribault, and R. Kemler. 1989. The cytoplasmic domain of the cell adhesion molecule uvomorulin associates with three independent proteins structurally related in different species. EMBO J. 81711-1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park, C. L., I. M. Kim, M. S. Lee, C.-y. Youn, D. J. Kim, E.-h. Jho, and W. K. Song. 2004. Modulation of β-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by cyclin-dependent kinase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 27919592-19599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiang, Y. W., and S. Rudikoff. 2004. Wnt signaling in B and T lymphocytes. Frontiers Biosci. 91000-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raja, N. U., and M. A. Jabbar. 1996. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein tethered to the CD4 extracellular domain is localized to the plasma membrane and is biologically active in the secretory pathway of mammalian cells: implications for the mechanisms of Vpu function. Virology 220141-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadot, E., M. Canacci-Sorrell, J. Zhurinsky, D. Shnizere, Z. Lando, D. Zharhary, Z. Kam, A. Ben-ze'ev, and B. Geiger. 2002. Regulation of S33/S37 phosphorylated β-catenin in normal and transformed cells. J. Cell Sci. 1152771-2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakai, H., K. Tokunaga, M. Kawamura, and A. Adachi. 1995. Function of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein in various cell types. J. Gen. Virol. 762717-2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schubert, U., S. Bour, A. V. Ferrer-Montiel, M. Montal, F. Maldarelli, and K. Strebel. 1996. The two biological activities of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein involve two separable structural domains. J. Virol. 70809-819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schubert, U., K. A. Clouse, and K. Strebel. 1995. Augmentation of virus secretion by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein is cell type independent and occurs in cultured human primary macrophages and lymphocytes. J. Virol. 697699-7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schubert, U., P. Henklein, B. Boldyreff, E. Wingender, K. Strebel, and T. Porstmann. 1994. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 encoded Vpu protein is phosphorylated by casein kinase-2 (CK-2) at positions Ser52 and Ser56 within a predicted α-helix-turn-α-helix-motif. J. Mol. Biol. 23616-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schubert, U., and K. Strebel. 1994. Differential activities of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1-encoded Vpu protein are regulated by phosphorylation and occur in different cellular compartments. J. Virol. 682260-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwarzenberger, K., and M. C. Udey. 1996. Contact allergens and epidermal proinflammatory cytokines modulate Langerhans cell E-cadherin expression in situ. J. Investig. Dermatol. 106553-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schweneker, M., A. S. Bachmann, and K. Moelling. 2004. The HIV-1 co-receptor CCR5 binds to α-catenin, a component of the cellular cytoskeleton. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325751-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spearman, P., J.-J. Wang, N. VanderHeyden, and L. Ratner. 1994. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein domains essential to membrane binding and particle assembly. J. Virol. 683232-3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Staal, F. J. T., M. van Noort, G. J. Strous, and H. C. Clevers. 2002. Wnt signals are transmitted through N-terminally dephosphorylated β-catenin. EMBO Rep. 363-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stephens, E. B., C. McCormick, E. Pacyniak, D. Griffin, D. M. Pinson, F. Sun, W. Notnick, S. W. Wong, R. Gunderson, N. E. Berman, and D. K. Singh. 2002. Deletion of the Vpu sequences prior to the Env in a simian-human immunodeficiency virus results in enhanced Env precursor synthesis but is less pathogenic for pig-tailed macaques. Virology 293252-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strebel, K., T. Klimkait, and M. A. Martin. 1988. A novel gene of HIV-1, vpu, and its 16-kilodalton product. Science 2411221-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taurin, S., N. Sandbo, Y. Qin, D. Browning, and N. O. Dulin. 2006. Phosphorylation of β-catenin by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2819971-9976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Troyanovsky, R. B., E. Sokolov, and S. M. Troyanovsky. 2003. Adhesive and lateral E-cadherin dimers are mediated by the same interface. Mol. Cell. Biol. 237965-7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsai, C. N., C. L. Tsai, K. P. Tse, H. Y. Chang, and Y. S. Chang. 2002. The Epstein-Barr virus oncogene product, latent membrane protein 1, induces the downregulation of E-cadherin gene expression via activation of DNA methyltransferases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9910084-10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Varthakavi, V., R. M. Smith, S. P. Bour, K. Strebel, and P. Spearman. 2003. Viral protein U counteracts a human host cell restriction that inhibits HIV-1 particle production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10015154-15159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Varthakavi, V., R. M. Smith, K. L. Martin, D. Deredowski, A. Lapierre, R. R. Goldenring, and P. Spearman. 2006. The pericentriolar recycling endosome plays a key role in Vpu-mediated enhancement of HIV-1 particle release. Traffic 7298-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Verma, U. N., R. M. Surabhi, A. Schmaltieg, C. Becerra, and R. B. Gaynor. 2003. Small interfering RNAs directed against β-catenin inhibit the in vitro and in vivo growth of colon cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 91291-1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Westervelt, P., T. Henkel, D. B. Trowbridge, J. Orenstein, J. Heuser, H. E. Gendelman, and L. Ratner. 1992. Dual regulation of silent and productive infection in monocytes by distinct HIV-1 determinants. J. Virol. 663925-3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wheelock, J. M., K. A. Knudsen, and K. R. Johnson. 1996. Membrane-cytoskeletal interactions with cadherin and cell adhesion proteins: role of catenins as linker proteins. Curr. Topics Microbiol. Immunol. 43169-185. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yook, J. I., X. Y. Li, I. Ota, E. R. Fearon, and S. J. Weiss. 2005. Wnt-dependent regulation of the E-cadherin repressor snail. J. Biol. Chem. 28011740-11748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoon, M., and P. G. Spear. 2002. Disruption of adherens junctions liberates nectin-1 to serve as receptor for herpes simplex virus and pseudorabies virus entry. J. Virol. 767203-7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang, L., Y. Huang, H. Yuan, S. Tuttleton, and D. D. Ho. 1997. Genetic characterization of vif, vpr, and vpu sequences from long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Virology 228340-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]