Abstract

Genetic analysis of muscle specification, formation and function in model systems has provided valuable insight into human muscle physiology and disease. Studies in Drosophila have been particularly useful for discovering key genes involved in muscle specification, myoblast fusion, and sarcomere organization. The muscles of the Drosophila female reproductive system have received little attention despite extensive work on oogenesis. We have used newly available GFP protein trap lines to characterize of ovarian muscle morphology and sarcomere organization. The muscle cells surrounding the oviducts are multinuclear with highly organized sarcomeres typical of somatic muscles. In contrast, the two muscle layers of the ovary, which are derived from gonadal mesoderm, have a mesh-like morphology similar to gut visceral muscle. Protein traps in the Fasciclin 3 gene produced Fas3::GFP that localized in dots around the periphery of epithelial sheath cells, the muscle surrounding ovarioles. Surprisingly, the epithelial sheath cells each contain a single nucleus, indicating these cells do not undergo myoblast fusion during development. Consistent with this observation, we were able to use the Flp/FRT system to efficiently generate genetic mosaics in the epithelial sheath, suggesting these cells provide a new opportunity for clonal analysis of adult striated muscle.

Keywords: oogenesis, visceral muscle, Fasciclin 3, Zasp, Filamin

Introduction

One of the great advantages of Drosophila is the use of genetic mosaics for studying developmental mechanisms and cell function. By inducing heritable genetic changes in subsets of cells, the cellular phenotypes of mutations that are otherwise homozygous lethal can be examined in detail. This approach is particularly useful for studying the contribution of genes to later stages of development when loss of function is lethal during embryogenesis or larval development (Blair, 2003). However, genetic mosaic techniques rely on each cell having a single nucleus. Therefore, adult muscles that are multinuclear because of myoblast fusion cannot be studied using genetic mosaic approaches. Here we describe an adult muscle type in Drosophila made of mononuclear cells and its potential for mosaic analysis.

The distinctive cellular morphology of different muscle types contributes enormously to specialized muscle function. Vertebrate muscles have been classically divided into three morphological categories: skeletal, cardiac and smooth. Skeletal muscles consist of long striated, multinucleated myotubes formed by the fusion of a number of precursor cells. Skeletal muscle excitation and contraction are controlled by the peripheral nervous system. Cardiac muscle is located solely in the heart and consists of striated, binucleated cells that attach to each other at special junctions called intercalated discs. Adult cardiac myocytes have two nuclei as a result of incomplete cell division rather than cell fusion as in skeletal muscle (Engel et al., 2006). Although there is nervous system modulation of the contraction of cardiac muscle and a pacemaker that coordinates heart contraction, each cardiac muscle has an intrinsic contraction rate and will continue to beat when in isolation. The third type, smooth muscle, surrounds a number of tubes and organs including the gut, blood vessels, fallopian tubes, uterus and bladder. Smooth muscle cells are mononucleate and do not have an organized sarcomeric structure; instead, they have a matrix of actin fibers. The nervous system, hormone action and interspersed pacemaker cells known as Interstitial Cells of Cajal (ICC) regulate smooth muscle contraction and tone.

Studies in Drosophila continue to provide valuable insights into muscle specification, development and function (Beckett and Baylies, 2006; Chen and Olson, 2004; Sink, 2006). Drosophila somatic muscles, including body wall and indirect flight muscle, are analogous to vertebrate skeletal muscle. The Drosophila heart provides a simplified model system for studying cardiac cell specification and function. The visceral muscles surrounding the gut and gonads are functionally analogous to vertebrate smooth muscle, although unlike smooth muscle cells, they are striated. Genetic studies of mesoderm formation, myoblast fusion and cardiac development have led to the discovery of key genes, many with conserved functions in vertebrates. Studies of adult muscle organization and function in Drosophila have largely been limited to the indirect flight muscles (IFM) owing to the ease of isolating flightless mutants, many of which affect sarcomere components (Vigoreaux, 2001).

Oogenesis in Drosophila is a well-established and valuable system for studying the genetic regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (Hudson and Cooley, 2002); however, this system has not been exploited for the study of sarcomere organization or muscle function. There are three types of muscle cells derived from two different developmental lineages in the Drosophila reproductive system (Mahowald and Kambysellis, 1980) (Fig. 1A). The peritoneal sheath is an anastomosing muscle layer surrounding each of the two intact ovaries. The epithelial sheath is a layer of thin circular muscles surrounding each of the approximately 16 ovarioles, the ovarian “production lines”. Both of these visceral muscle types derive from mesodermal cells in the apical pole of pupal ovaries (Godt and Laski, 1995; King, 1970). Lateral oviducts that fuse into a common oviduct through which mature eggs pass to enter the uterus connect the two ovaries in each female. A circular layer of somatic muscles derived from the genital disc surrounds these oviducts. All three muscle type are striated (Middleton et al., 2006) and recent work has shown that although the oviducts and the posterior part of the peritoneal sheath are innervated, there are no nerves in contact with the epithelial sheath (Middleton et al., 2006; Rodriguez-Valentin et al., 2006). All three muscle types can continue contracting when dissected from the fly, indicating that nervous system control is modulatory rather than necessary for muscle contraction.

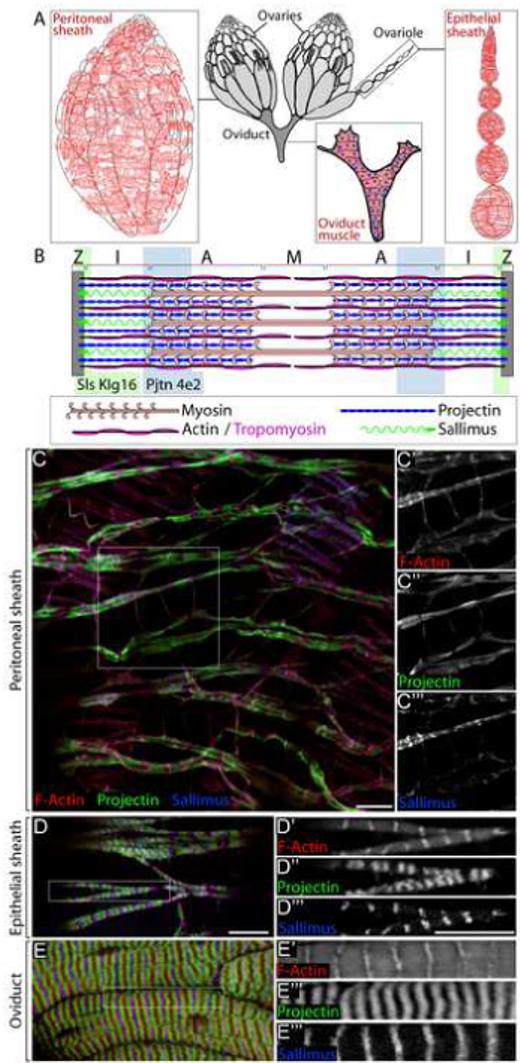

Figure 1.

Drosophila ovarian muscle types. (A) Drosophila ovaries have three types of muscle: the Peritoneal sheath, which surrounds each intact ovary, the Epithelial sheath, which surrounds each ovariole, and the muscle of the oviducts. (B) Sarcomeres contain Z-discs that anchor the F-actin thin filaments, and myosin thick filaments bound to F-actin. The registration and position of thick filaments gives a characteristic banding pattern with the I band containing thin filaments, A band containing thick and thin filaments and the M band containing only thick filaments. The model also shows approximate positions of Sallimus, Projectin and Tropomyosin. The shading represents the locations of the epitopes recognized by Sallimus and Projectin antibodies. (C) Peritoneal sheath muscle labeled with phalloidin (red) to reveal F-Actin distribution (C’), and antibodies to Projectin (green) (C”) and Sallimus (blue) (C’”). (D) Epithelial sheath muscle labeled as in C. (E) Oviduct muscle labeled as in C. Scale bars: 10 μ.

In this work we characterize ovarian muscle cell morphology, taking advantage of protein trap lines that express GFP-tagged proteins (Morin et al., 2001; Quiñones-Coello et al., 2007). We show that all three ovarian muscle types have a classical sarcomere structure as revealed by antibody staining and protein traps in previously identified sarcomeric components. We identify two new sarcomeric proteins that encode homologs to the vertebrate ZASP protein that localize to Z-discs in a wide array of muscle types. Detailed study of epithelial sheath muscles shows that they consist of mesh-like cells that are attached to each other by novel Fasciclin 3-containing cell-cell junctions. Surprisingly, each epithelial sheath cell contains a single nucleus, showing that they differentiate without first fusing into multinuclear myotubes. In addition, we show that mitotic clones of epithelial sheath cells can be generated using Flp/FRT-mediated mitotic recombination. Thus, epithelial sheath cells show great potential for genetic studies of adult striated muscle.

Materials and Methods

Genetics and fly strains

Drosophila cultures were maintained using standard procedures. The wild-type control was w1118. The following protein trap lines were used: G00035 (CG15926), G00189 (Zasp52), ZCL0663 (Zasp66), YD0783 (Mhc), YB0242 (meso18E), ZCL2154 (Fas3) YC0071 (Tm1), ZCL2144 (Sls), ZCL3111 (Ilk). These lines are available at flytrap.med.yale.edu (Kelso et al., 2004). The Gal4 driver line Mef2-Gal4 was from Eric Olson (Ranganayakulu et al., 1996). The following lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center: FRT42D (B2118), UAS-myr-mRFP (B7118), and hsFLP (B6416). For mosaic analysis, Zasp52::GFP was recombined with FRT42D to provide a uniformly expressed epithelial sheath marker for scoring mitotic recombination events. FRT42D, Zasp52::GFP flies were crossed to hsFlp; FRT42D and progeny were heat shocked for 1 hour at 38° on two consecutive days during larval development.

Immunofluorescence and image collection

Ovaries were dissected and fixed as described previously (Robinson and Cooley, 1997). Larval midgut and body wall muscle were dissected out of third instar larvae and fixed as described for ovaries above. Indirect flight muscle was dissected from adult thoraces in IMADS buffer (Singleton and Woodruff, 1994) and fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. To visualize actin, tissues were incubated with 2 U rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin in PBT. For antibody labeling, tissues were incubated either overnight at 4°C or 2 hours at room temperature with anti-GFP antibody at 1:750 (Molecular Probes A11122), CF.6G11 at 1:200 (Integrin beta PS, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), Sls antibody Klg16 (also known as MAC155) at 1:5 (Lakey et al., 1990) (obtained at the Burnham Institute, La Jolla, CA), Projectin antibody 4e2 at 1:5 (Saide et al., 1989), α-Actinin antibody at 1:5 (Saide et al., 1989) or C-Filamin antibody at 1:500 (Sokol and Cooley, 1999). Secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexafluor 488, 568 or 633 (Molecular Probes) were used at 1:500 and were incubated with tissues for 2 hours at room temperature. Tissues were stored in Antifade (0.23% DABCO in 0.1 M Tris-HCL 90% glycerol) overnight at 4°C and then mounted. All images were taken on either a ZEISS LSM-510 or a ZEISS LSM-510 META microscope (Center for Cell and Molecular Imaging, Yale University School of Medicine) or on a ZEISS Axiovert 200 equipped with a CARV II confocal imager (BD Bioscience) and CoolSnap HQ2 camera (Roper Scientific). Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 7 and figures were assembled using Adobe Illustrator CS.

3D image analysis

Confocal Z-stacks through entire ovarioles were taken of Fas3::GFP; Mes18::GFP expressing ovaries. In order to increase the contrast and count individual nuclei and Fas3 domains, we either 1) processed the GFP black and white image stacks using unsharp mask followed by a low pass filter, or 2) used Adobe Photoshop 7.0 to draw dots covering each Fas3 dot in each image of the stack. In order to make counting easier, the dots in images in each half of the stack were assigned a different color. Additionally, each nucleus was drawn once per total stack. Projection image stacks were created with the 3D construction module in Meta Morph (Universal Imaging), and exported as either still images or movies for analysis.

Results

The three ovarian muscle types are striated with a typical sarcomeric organization

The sarcomeres of ovarian muscles have a typical organization (Fig. 1B). We examined the distribution of the Projectin and Sallimus proteins, which are large extended proteins that connect Z-discs to thick filaments. Sallimus and Projectin proteins are functionally the same as Titin in vertebrate sarcomeres (Burkart et al., 2007). The sallimus (sls) gene is very large with many verified splice forms that encode Sls proteins, Zormin and Kettin (Burkart et al., 2007). We used the KIg16 monoclonal antibody (also known as MAC155) that recognizes an epitope near the amino-terminus of Sls and Kettin and labels the Z-discs in sarcomeres (Lakey et al., 1990) (Fig. 1B). We found that KIg16 antibody also labeled Z-discs in ovarian muscle cells (Fig. 1C, D and E). To examine Projectin localization, we used monoclonal antibody 4e2, which labels Z-discs in indirect flight muscle and the A band in larval gut muscle (Saide et al., 1989). In ovarian muscle cells, there were two domains of 4e2 staining between each Z-disc (Fig. 1C, D and E). This pattern was easiest to see in oviduct muscle (Fig. 1E), and likely represents A band labeling (see Fig. 1B).

Sarcomere staining revealed that the three ovarian muscle types have distinct overall morphologies. The peritoneal sheath muscle is comprised of relatively thick bundles of muscle fiber circling the ovary perpendicular to its anterior-posterior axis, and thinner single fibers that travel parallel to the A/P axis of the ovary connecting the thick muscle bundles to one another (Fig. 1C). Clear periodic Z-bands were present in the thick muscle fiber bundles that labeled strongly with phalloidin and KIg16 antibody, although the Z-discs were not all in register in neighboring fibers. Projectin antibody labeling was in a somewhat diffuse band between Z-bands. The thin longitudinal bundles also exhibited evidence of sarcomeric organization: a clear enrichment of Projectin was observed between Z-bands containing actin and Sls, though Sls labeling was weaker (Fig. 1C’, C”, C’”). The sarcomeres of the epithelial sheath surrounding ovarioles were more robust with Z-discs in register within each fiber (Fig. 1D). We will discuss the organization of epithelial sheath muscle in greater detail below.

Consistent with its distinct developmental lineage, the oviduct muscle was quite different in appearance from the epithelial and peritoneal sheath muscles. The large oviduct muscle cells contained highly ordered sarcomeres resembling those in IFM (Fig. 1E). Like IFM, oviduct muscle cells were multinucleate cells and thus presumably the products of myoblast fusion (see Supplemental Fig. S1).

GFP protein traps in known sarcomeric proteins localize to ovarian muscles

We and others have carried out extensive protein trap screening in which transposons carrying an artificial exon encoding GFP were mobilized and embryos or larvae were screened for GFP expression (Buszczak et al., 2007; Morin et al., 2001; Quiñones-Coello et al., 2007). A number of the resulting lines produced GFP-fusions to previously characterized sarcomeric components including Sallimus (Sls), Myosin heavy chain (Mhc), Integrin linked kinase (Ilk) and Tropomyosin 1 (Tm1). Analysis of GFP expression in ovarian muscles showed localization to the expected sarcomeric components for these proteins, confirming that the GFP-fusion proteins provide accurate information on protein localization.

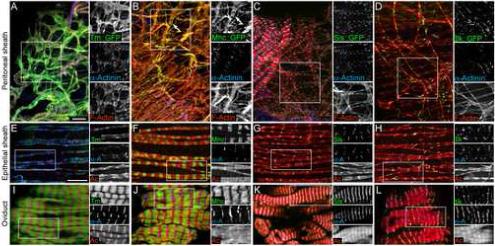

Tm1::GFP colocalized with sarcomeric F-actin in all three ovarian muscle types (Fig. 2A, E, I). In oviduct muscle, Tm1::GFP colocalized with F-actin in sarcomeres with the exception of the Z-bands (Fig. 2I). Tm1::GFP was also reduced at Z-bands in epithelial sheath, although this is more difficult to view (Fig. 2E). Mhc::GFP localized to the A-band (Fig. 2B, F, J). Very clear Mhc::GFP-positive A-bands were easily visible in the oviduct and epithelial sheath where sarcomeric structure was clear (Fig. 2 F and J). The A-band was harder to see in the more irregularly shaped peritoneal sheath, but was still apparent (Fig. 2B, arrow).

Figure 2.

Expression of GFP protein traps in known sarcomere proteins. (A-D) Peritoneal sheath labeled with antibodies to α-Actinin (blue) to view Z-discs and phalloidin (red) to reveal F-Actin. The peritoneal sheath is from flies expressing protein traps (green) in Tm1 (A), Mhc (B), Sls (C) and Ilk (D). (E-H) Epithelial sheath labeled as in A-D. (I-L) Oviduct labeled as in A-D. For all panels, the three individual color channels in the boxed regions are shown to the right. Scale bars: 10 μ.

GFP fusions to Sallimus and Integrin linked kinase revealed two types of Z-band staining. The GFP insertion in the sls gene in protein trap line ZCL2144 is in an intron between coding exons for Sls and Kettin, but not Zormin. Therefore, both Sls and Kettin can be tagged near their amino-termini with GFP. Similar to the KIg16 antibody, Sls::GFP localized specifically to Z-discs in oviduct, epithelial sheath and peritoneal sheath, as seen by costaining with α-Actinin antibody (Fig. 2C, G and K). Ilk::GFP also localized to Z-discs (Fig. 2D, H and L). However, 3D analysis of confocal stacks of oviducts showed that Ilk::GFP localized to a ring at the periphery of the Z-disc (Supplemental Fig. S2). It may be that Ilk::GFP also localizes to the periphery of the Z-disc in epithelial sheath and peritoneal sheath; however, the thinness of the tissue precluded this level of visualization. The peripheral localization of Ilk::GFP is consistent with localization to costameres that surround Z-discs and link sarcomeres to the cell membrane.

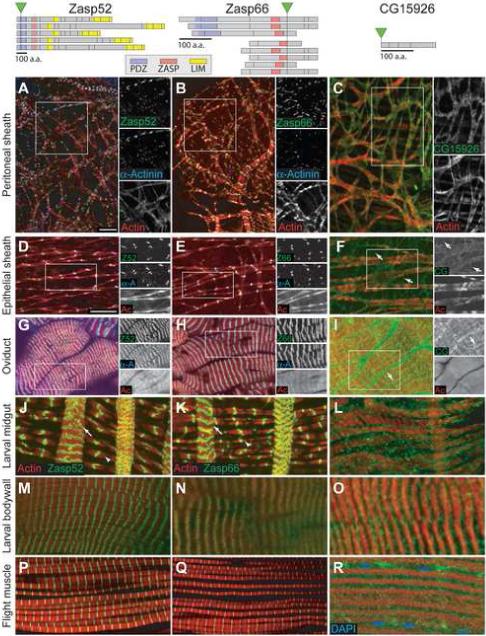

Two uncharacterized PDZ proteins localize to Z-discs

We found two protein trap lines that showed a striped pattern in ovarian muscle. The GFP transposon in these lines was inserted into the genes for two uncharacterized proteins, CG30084 and CG6416, both of which contain a PDZ domain (SMART SM00228) and a ZASP motif (ZM) (SMART SM00735). (Note: previous publications mislabeled CG30084 as the tungus gene. This has now been corrected; the tungus gene is CG8253. See FlyBase reference FBrf0188553 for explanation). CG30084 also contains four LIM domains (SMART SM00132) in its C-terminus. Both CG30084 and CG6416 proteins show homology to the human Z-disc Alternatively Spliced Protein (ZASP) that localizes to the Z-disc in skeletal muscle. Like the ZASP gene, both CG30084 and CG6416 encode a number of alternative splice forms, almost all of which could be tagged based on the locations of the protein trap insertions (Fig. 3). An additional isoform of CG30084 has been annotated that encodes only LIM domains and cannot be tagged (not shown). Due to the homology of these genes to ZASP, we designated CG30084 as Zasp52, and CG6416 as Zasp66 based on the cytological location of the genes.

Figure 3.

Ovarian muscle expression of GFP protein traps in uncharacterized proteins. Top: Schematic representations of isoforms predicted through differential splicing of Zasp52, Zasp66 and CG15926 from Flybase. The location of the GFP gene insertion with respect to each isoform is indicated with a green triangle and the locations of exon boundaries are indicated by black lines. Bottom: Expression patterns of GFP-tagged proteins (green) in peritoneal sheath (A-C), epithelial sheath (D-F), oviduct (G-I), larval midgut (J-L), larval body wall (M-O), and adult indirect flight muscle (P-R) stained with phalloidin (red) and α-Actinin antibodies (blue, A, B, D, E, G and H) or Dapi (blue, R). Zasp52::GFP (first column) and Zasp66::GFP (second column) colocalize with α-Actinin in Z-discs in peritoneal sheath (A,B) epithelial sheath (D,E) and oviduct (G,H). Z-discs in both the longitudinal (arrows) and circular (arrowheads) muscles of the larval midgut contain Zasp proteins (J, K), as do Z-discs in larval body wall (M, N) and adult flight muscles (P, Q). CG15926::GFP localizes to cell membranes in all muscle types. Additional localization to membranes on the interior of muscle cells can be seen in oviduct (I, arrow), larval midgut (L), larval bodywall (O) and flight muscle (R). This may be sarcoplasmic reticulum. Scale bars: 10 μ. Scale bar in D applies to D-R.

To determine if the striped pattern we saw for Zasp52::GFP and Zasp66::GFP was Z-discs, we co-stained ovaries with α-Actinin antibody. In all three ovarian muscle types, both Zasp52::GFP and Zasp66::GFP specifically co-localized with α-Actinin on Z-discs (Fig. 3A, B, D, E, G, H). In order to determine if these proteins were specific to ovarian muscles or more broadly expressed, we examined larval midgut visceral muscles, larval body-wall muscles and adult flight muscles. In all muscle types we saw localization of Zasp52::GFP and Zasp66::GFP to a striped pattern reminiscent of ovarian muscles (Fig. 3J, K, M, N, P, Q). Thus, Zasp52 and Zasp66 appear to be universal constituents of Z-discs in Drosophila striated muscle.

A protein trap in a novel membrane protein gives insight into muscle cell shape

To characterize the cellular organization of ovarian muscle cells, we tried a number of approaches to define cell boundaries by visualizing muscle cell membranes. Previous EM analysis had shown that the cells of the peritoneal sheath have a loose mesh-like structure (Mahowald and Kambysellis, 1980), but the shape of epithelial sheath cells has not been investigated in detail. We first used the lipophilc dye FM4−64, but the high signal-to-noise ratio and interference with signal from underlying follicle cells made interpretation of the labeling pattern difficult. We next attempted to drive UAS-myristoylated-RFP (UAS-myrRFP) with a number of GAL4 drivers reported to be muscle-specific. However, most Gal4 drivers gave no epithelial sheath or peritoneal sheath expression, although several did promote robust expression in oviduct muscle (Supplemental Fig. S1, data not shown). The only tested muscle driver that gave expression in all ovarian muscles was Mef2-Gal4 (Ranganayakulu et al., 1996). Thus, it appears that the epithelial sheath and peritoneal sheath muscles, which are derived from somatic cells of the gonad, have a different expression profile compared to other muscle types. Mef2-Gal4 driving UAS-myrRFP (Mef2>myrRFP) showed the clear outline of oviduct muscle cells (Supplemental Fig. S1). Mef2>myrRFP expression in the epithelial sheath was much fainter, but appeared to surround sarcomeric structures.

We were aided in our efforts to define muscle cell boundaries by a protein trap line that appeared to produce a ubiquitously expressed marker for cell membranes. Protein trap line G00035 produces a GFP fusion to the CG15926 protein, which is a small (17 kDa) non-conserved protein with no known protein motifs. CG15926::GFP was located specifically on plasma membranes in both follicle cells and germline cells in egg chambers (not shown), suggesting this protein trap is useful for marking plasma membranes in other cells. The pattern of CG15926::GFP expression in oviduct muscle was similar to Mef2>myrRFP, localizing brightly to cell membranes and also to intracellular bands that lie along sarcomeres that could be sarcoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 3I, arrow). CG15926::GFP also outlined the mesh-like shape of the peritoneal sheath (Fig. 3C), and revealed that epithelial sheath cells are similarly mesh-like in shape (Fig. 3F). Examination of CG15926::GFP in the epithelial sheath revealed that the cell membranes surround the sarcomeric structures, similar to the peritoneal sheath and circular visceral muscles. Interestingly, the gaps between the sarcomeres of the epithelial sheath were much larger than in circular visceral muscle (compare Fig. 3F and L). Further examination of epithelial sheath showed thin membrane projections between sarcomeres that appeared to connect to neighboring cells (Fig 3F, arrows). Due to the thinness of both the epithelial sheath and peritoneal sheath, it was very difficult to see any intracellular sarcoplasmic reticulum localization of CG15926::GFP. Expression of CG15926::GFP in other muscle types showed localization to both cell membranes and sarcoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 3L, O, and R). This was especially apparent in IFM where bright expression was seen along the borders of muscle fibers, indicated by the positions of the nuclei, and also surrounding the individual sarcomeres within the bundle (Fig. 3R).

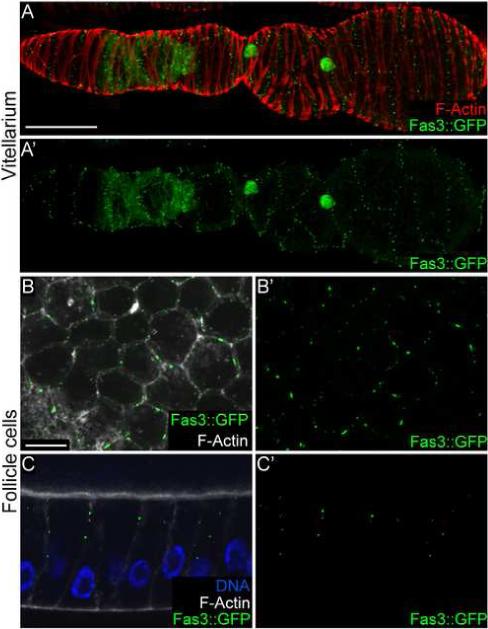

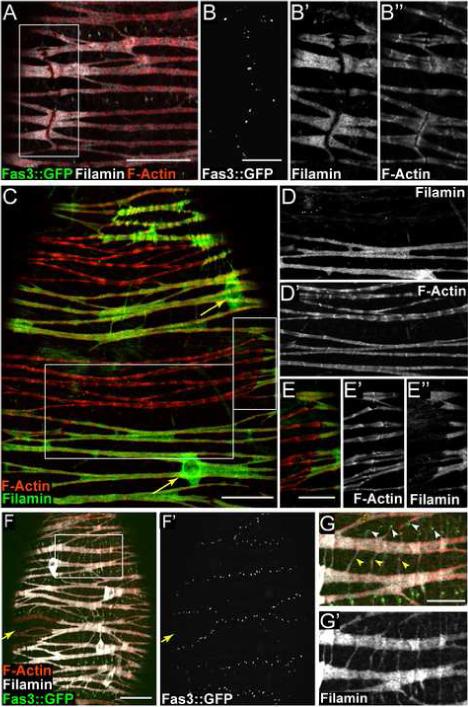

Fas3::GFP localization to novel cell-cell junctions

Fasciclin 3 (Fas3) is an immunoglobulin super-family member known to be involved in homophilic cell-cell adhesion (Snow et al., 1989). It has been shown to be necessary for the formation of some neuro-muscular junctions in larval body wall muscle (Chiba et al., 1995). A protein trap line in Fas3 provided key insight into the morphology of epithelial sheath muscle cells. As has been previously described using Fas3 antibodies, Fas3::GFP was expressed highly in follicle cells of germaria and early egg chambers, and then its expression became specific to polar follicle cells (Fig. 4A). However, we saw an additional localization pattern that has not been previously described. On the surface of egg chambers, Fas3::GFP localized in a series of dotted lines around the circumference of ovarioles, forming a garland pattern (Fig. 4A’). These dots were within the epithelial sheath muscle tissue. Closer inspection of underlying follicle cells showed that they also contained small Fas3::GFP dots on cell membranes (Fig. 4B and C). The follicle cell Fas3::GFP dots were in the apical lateral part of the cell membrane, an area associated with junctional complexes. Therefore, the dots in the garland pattern in epithelial sheath are also likely to be on the membrane, and perhaps in intercellular junctions.

Figure 4.

A GFP protein trap in Fasciclin 3 reveals novel cell-cell junctions. (A, A’) An ovariole expressing Fas3::GFP with (A) and without (A’) phalloidin in red. Fas3::GFP localizes to follicle cells in the germaria and then is restricted to polar follicle cells. Additionally a “garland” pattern of Fas3::GFP puncta can be seen in the overlying epithelial sheath. (B, B’) The surface view of follicle cells expressing Fas3::GFP with (B) and without (B’) phalloidin in white. Fas3::GFP puncta can be seen on the cell membrane. (C, C’) A lateral view of follicle cells expressing Fas3::GFP with (C) and without (C’) phalloidin in white and Dapi in blue. Fas3::GFP puncta localize to the apical lateral region of the membrane. Scale bars: A = 50 μ, B = 10 μ. Scale bar in B applies to C.

Fas3 and Filamin expression reveal the shape of epithelial sheath cells

To further characterize the cellular organization of epithelial sheath muscle, we examined more closely the distribution of the 90 kDa Filamin isoform (FLN12−20) produced by the cheerio locus (Sokol and Cooley, 1999). The FLN12−20 isoform is transcribed from an internal promoter, and consists of nine C-terminal Filamin repeats without the N-terminal F-Actin binding domain typical of Filamin proteins. In ovaries, FLN12−20 expression is restricted to muscle, as mutations that eliminate the larger FLN1−20 isoform but retain FLN12−20 expression show unchanged epithelial sheath localization (Sokol and Cooley, 1999). Consistent with the lack of an F-actin binding domain, FLN12−20 did not colocalize with F-actin, but instead was distributed homogeneously within muscle cells (Fig. 5A), and therefore is a useful marker for determining the shape of epithelial sheath muscle cells.

Figure 5.

FLN12−20 and Fas3::GFP expression reveal epithelial sheath cell shape. (A) Immunofluorescence of epithelial sheath expressing Fas3::GFP (green) with FLN12−20 labeled white and phalloidin red. (B-B”) Higher magnification and channel separation of boxed area shown in (A). (C) Immunofluorescence of epithelial sheath showing mosaic expression levels of FLN12−20 (green). Phalloidin-labeled F-Actin is red. FLN12−20 is present in cell bodies around nuclei (arrows). (D-D”) Higher magnification and channel separation of boxed area in panel C. Sarcomeric F-Actin exhibits a more pronounced periodicity in cell expressing a lower level of FLN12−20 (compare sarcomeric bundles in the upper part of D’ with those in the lower half). (E-E”) Higher magnification and channel separation of boxed area in panel C. F-Actin “joints” coincide with borders between regions of high and low FLN12−20 expression. (F-F”) Epithelial sheath muscle expressing Fas3::GFP (green) and also displaying FLN12−20 (white) mosaicism. F-Actin is red. Region expressing low levels of FLN12−20 (arrow) is outlined by Fas3::GFP dots. (G-G’) Higher magnification and channel separation of boxed area shown in (F). Two types of fine projections are evident extending from muscle cell bodies: those associated with Fas3 dots (G, white arrowheads), and those that extend from one portion of a cell body to another (G, yellow arrowheads). Scale bars: A, C and F = 20 μ, B, E and G = 10 μ. Scale bar in C applies to D.

FLN12−20 expression and the Fas3::GFP pattern together allowed us to identify epithelial sheath cell boundaries with confidence. Localization of FLN12−20 in the Fas3::GFP line revealed distinct discontinuities in FLN12−20 expression that coincided with rows of Fas3::GFP dots oriented parallel to the long axis of an ovariole (Fig. 5A, B and B’). Examination of F-Actin at these FLN12−20 gaps revealed discontinuities that looked like F-Actin “joints”, which were distinct from the otherwise periodic patterning (Fig. 5B”). The interruptions in both FLN12−20 and F-actin, coincident with Fas3 dots on the cell surface, mark the end-to-end cell junctions of adjacent muscle cells.

FLN12−20 expression sometimes exhibited a striking mosaic expression pattern in epithelial sheath (Fig. 5C), with regions of very high FLN12−20 expression adjacent to regions with very low levels. There was no evident pattern to the mosaicism that suggested a functional relevance; however, we did observe differences in F-Actin distribution in sarcomeres that contained differing levels of FLN12−20. Sarcomeres with lower levels of FLN12−20 had a more pronounced F-actin periodicity than sarcomeres expressing higher levels of FLN12−20 (Fig. 5D, D’). F-Actin “joints” were observed at some boundaries of mosaic expression (Fig. 5E-E”) and the domains of high and low expression were similar in size and shape to the regions demarcated by Fas3::GFP dots (Fig. 5F, F’, arrow). Taken together, the areas of differing FLN12−20 protein levels, which are bordered by a plasma membrane junctional protein (Fas3), along with the discontinuities in sarcomeric F-Actin, allow us to conclude that Fas3::GFP marks the borders of discrete cells in epithelial sheath.

FLN12−20 labeling also revealed the shape of lateral contacts between epithelial sheath cells. Fine extensions projected from cell bodies parallel to the long axis of the ovariole (Fig. 5F, and G-G”); these extensions were generally easier to observe in muscle surrounding younger egg chambers. The projections were associated with rows of Fas3::GFP dots running perpendicular to the long axis of the ovariole (Fig. 5F and G white arrowheads), and thus represent lateral contacts between adjacent cells along the ovariole. Additional fine projections were apparent traversing adjacent sarcomeric bundles within the same cell (Fig. 5F and 5G, yellow arrowheads).

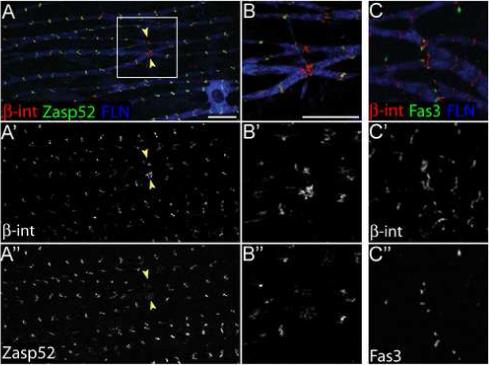

Epithelial sheath cell end junctions contain Integrin

End junctions of cardiac muscle cells, called intercalated discs, are characterized by the presence of adherens junction proteins such as α-catenin and ß-catenin. However, we were unable to detect these proteins in epithelial sheath (data not shown). Instead, the end junctions of epithelial sheath cells contained Integrin (Fig. 6) and Integrin linked kinase (data not shown). Integrin was also present at each Z-disc of the sarcomeres (Fig. 6A) where it is likely a component of costameres that link sarcomeres to the cell membrane. However, the level of Integrin at end junctions was higher than at Z-discs (Fig. 6A’, B’). Conversely, Zasp52 expression was lower at end junctions compared to Z-discs (Fig. 6A”, B”). The localization of Integrin at end junctions was distinctly different from the localization of Fas3 (Fig. 6C). Integrin was present in a continuous zone (Fig. 6C’) while Fas3 was in discrete dots (Fig. 6C”) that often corresponded to the position of F-actin in individual sarcomeres. Thus, the ends of epithelial sheath cells may be linked through structures resembling costameres, but that also contain Fas3.

Figure 6.

Epithelial sheath cell end junctions contain Integrin. (A-A”) Immunofluorescence of epithelial sheath expressing Zasp52::GFP (green) stained with antibodies to FLN12−20 (blue) and ß-Integrin (red). In A’, ß-Integrin expression is higher at end junctions between cells (yellow arrowheads) than at Z-discs, while Zasp52 expression is higher in Z-discs than at end junctions (A”). (B-B”). Higher magnification and channel separation of boxed area shown in (A). (C-C”) Immunofluorescence of epithelial sheath expressing Fas3::GFP (green) stained with antibodies to FLN12−20 (blue) and ß-Integrin (red). ß-Integrin is present in a continuous zone at end junctions (C’) while Fas3::GFP is in distinct dots (C”). Scale bars: 10 μ.

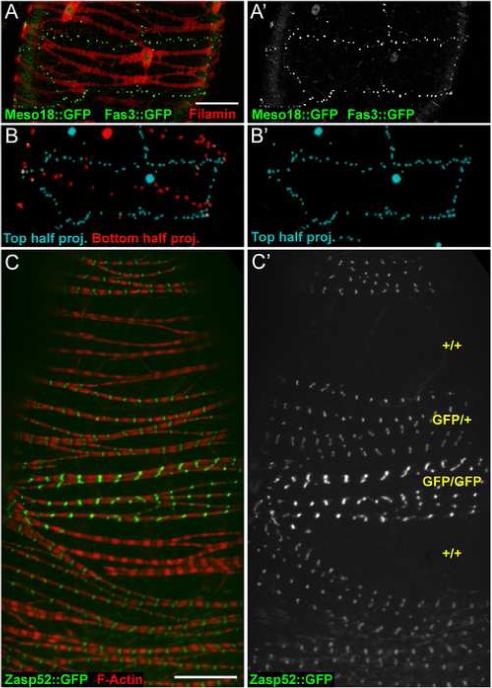

Epithelial sheath cells are mononuclear

With reliable markers for epithelial sheath cell shape and boundaries in hand, we determined the number of nuclei per cell. FLN12−20 localization revealed the cell bodies surrounding nuclei (Fig. 5C arrows, and F). We combined protein traps in Fas3 and the meso18E gene, which encodes a putative transcription factor involved in mesoderm specification (Taylor, 2000), along with FLN12−20 localization to simultaneously reveal epithelial sheath cell shape, nuclei and junctions (Fig. 7A, A’). This staining suggested that epithelial sheath cells contain one nucleus. However, because there were generally only two cells around the circumference of an ovariole, we rarely observed the entire border of a muscle cell on one side of an ovariole. Therefore, we collected confocal stacks through entire ovarioles and constructed three-dimensional renderings of Fas3::GFP and Meso18::GFP (Fig. 7B and B’). Rotation of these rendered stacks allowed us to unambiguously determine the number of nuclei in these cells (See supplementary material Movies M1 and M2). In each of 18 cells for which we could view the entire cell boundary in this manner, we observed a single nucleus. Thus, the muscle cells in the epithelial sheath are mononucleate and therefore not the product of myoblast fusion. Consistent with this observation, we were unable to detect expression of Sns or Duf, two proteins essential for myoblast fusion (Bour et al., 2000; Ruiz-Gomez et al., 2000), in larval, pupal or adult ovaries (LNP and LC, data not shown).

Figure 7.

Epithelial sheath cells are mononucleate. (A-A’) Confocal projection of top half of an ovariole expressing both Fas3::GFP (green dots) and Meso18::GFP (green nuclei) in epithelial sheath cells stained with antibodies to FLN12−20 (red). (A’) A single cell is clearly outlined by Fas3::GFP dots and contains only one nucleus, as seen with Meso18::GFP. (B-B’) Rendering of optical sections taken through the entire ovariole shown in A. Only green signal from Fas3::GFP and Meso18::GFP was rendered. The top half of the confocal stack is colored cyan, the bottom half red. B’ shows the top half only, and represents a rendering of the raw data shown in A’. See Supplemental movies for rotation of the raw data and rendered stacks. (C-C’) Confocal image of an ovariole with Flp/FRT-induced mitotic clones. F-Actin is in red and Zasp52::GFP is in green. C’ shows Zasp52::GFP only, with the inferred copy number of GFP genes indicated in yellow. Scale bars: 20 μ.

Muscle cells that differentiate without undergoing myoblast fusion should be amenable to standard Drosophila genetic mosaic techniques that use mitotic recombination to generate daughter cells of different genotypes. To determine if mitotic clones of epithelial sheath cells can be produced, we used the Flp/FRT system (Dang and Perrimon, 1992; Xu and Rubin, 1993). None of the commonly used markers were expressed well enough in epithelial sheath to be useful for these experiments. Therefore, we decided to use Zasp52::GFP as a marker for clonal analysis. Zasp52::GFP was expressed uniformly in epithelial sheath cells and not in the underlying egg chambers. After clone induction (see Materials and Methods), the ovaries of hsFlp; FRT42D, Zasp52::GFP/FRT42D adult females contained numerous epithelial sheath cells lacking Zasp52::GFP expression and nearby cells with brighter GFP expression (Fig. 7C and C’). The intensity of GFP expression indicated whether cells had zero, one or two copies of the GFP gene, with one copy present in cells that did not undergo mitotic recombination. 95% of ovarioles (n=132) had GFP-negative cells. In contrast, 0% (n=92) of control ovarioles (hsFlp; FRT42D, Zasp52::GFP/Balancer) had GFP-negative cells, confirming that there is no natural mosaicism of Zasp52 expression. These results indicate that epithelial sheath cells differentiate directly from mitotic cells without intervening myoblast fusion, and demonstrate that these cells provide a model for genetic analysis of individual muscle cells.

Discussion

Despite the well-documented value of Drosophila oogenesis as a model for studying numerous cellular mechanisms of development, the organization and function of muscle cells in the reproductive tract have received relatively little attention. We have used GFP protein trap lines and antibodies to characterize ovarian and oviduct sarcomere organization and muscle cell morphology. The availability of protein trap lines was especially useful for describing intercellular contacts (e.g., Fas3::GFP, Ilk::GFP) and for showing the location of “new” sarcomere components (e.g., Zasp52::GFP, Zasp66::GFP). The muscle cells of the oviducts, which are derived from genital disks, have highly organized sarcomeres and a myotube organization typical of somatic muscles in insects, and likely arise by myoblast fusion during development. In contrast, the visceral muscle layers surrounding ovarioles and ovaries have a mesh-like shape similar to the visceral muscles of the gut (Klapper et al., 2002). Surprisingly, we found that the epithelial sheath muscles contain one nucleus rather than two as in gut visceral muscles, making them the only known adult somatic or visceral muscle that does not arise by myoblast fusion. It remains to be determined whether the peritoneal sheath cells are mononuclear as well.

The nature of the epithelial sheath muscle makes it ideally suited for analysis of muscle function. The morphology of the cells can be viewed in great detail with an array of available sarcomere and cellular markers. Importantly, the ability to produce cells with a defined genotype by mitotic clone induction provides a new opportunity for studying the phenotypes in adult muscles caused by homozygous mutations in muscle genes, even if the mutations are lethal during early development. Finally, it is straightforward to do short-term in vitro culturing of ovarioles with the epithelial sheath intact and contracting; thus, the behavior of cells bearing mutations can be studied in live tissue under controlled conditions.

Protein traps identify novel muscle components

Protein trapping identified two previously uncharacterized Drosophila Z-disc components, Zasp52 and Zasp66, which are similar in organization to mammalian ZASP/Cypher/Oracle genes (Clark et al., 2002). In mammals, a single ZASP/Cypher/Oracle gene produces a number of protein products through alternative splicing, and the expression of some splice forms are restricted to either cardiac or skeletal striated muscle (Faulkner et al., 1999; Huang et al., 2003). These proteins associate with Z-discs via an interaction of their N-terminal PDZ domain with α-Actinin, and serve as Z-disc-associated scaffolding proteins. Deletion of the mouse gene causes congenital myopathy (Zhou et al., 2001), and mutations in human ZASP gene are associated with cardiac and distal myopathies (Griggs et al., 2007; Selcen and Engel, 2005; Vatta et al., 2003). In contrast to the single mammalian ZASP gene, Drosophila express alternatively spliced ZASP proteins from two distinct genes. We see no evidence of tissue-specific expression of Zasp52 and Zasp66; the protein traps express GFP fusion proteins in all muscle types examined. However, we may not have been able to detect all the splice variants since GFP is positioned near the N-terminus. Work on these genes may provide a model for understanding human myopathies associated with ZASP mutations.

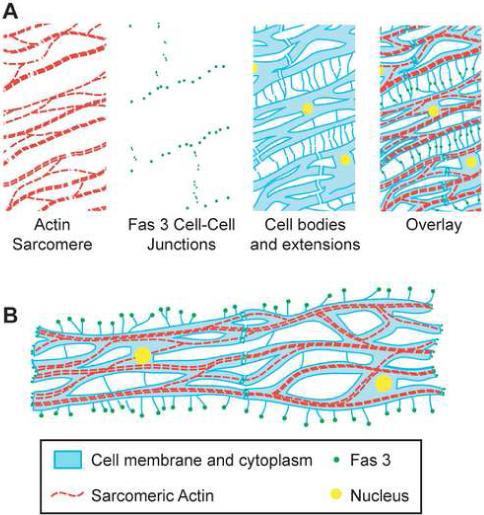

Epithelial sheath cell morphology revealed

The epithelial sheath cells have extensive intercellular contacts. Lateral contacts with neighboring cells are mediated by numerous thin cellular extensions, each tipped with a focus of Fas3 (Figs. 5G and 8A). The end-to-end junctions between cells also have foci of Fas3 (Figs. 5B and 8B) that are very often at the position where sarcomeric actin bundles contact the plasma membrane. These Fas3 foci constitute the dotted lines outlining cells that are visible in flies carrying the Fas3 protein trap. Interestingly, antibodies to Fas3 fail to label intercellular junctions in either epithelial sheath cells or follicle cells. The antibody may not recognize the cell surface Fas3 isoform tagged with GFP in the protein trap line. Despite the discrepancy between antibody staining and protein trap expression, our confidence that the GFP dotted pattern is Fas3::GFP is based on examining multiple insertions in the gene and analysis of cDNA sequence from the protein trap line. Therefore, Fas3 is likely to mediate cell adhesion of epithelial sheath cells through homotypic interactions, similar to its role in neuromuscular junctions (Chiba et al., 1995; Snow et al., 1989), and thus provide a means for coordinating peristaltic contraction of neighboring cells.

Figure 8.

Model of epithelial sheath cell structure. (A) Schematic of a section of epithelial sheath muscle showing one surface of an ovariole. Each muscle cell contains a single nucleus (yellow) and has a mesh like structure (blue). Thin cytoplasmic projections extend between cells in the anterior/posterior direction. Sarcomeric actin (red) forms branching structures within cells. Fas3 cell-cell contacts (green) are located at the both the end-to-end junctions between cells and at the intersection of lateral cytoplasmic extensions between adjacent cells. (B) Schematic of two epithelial sheath muscle cells filleted flat to emphasize that where two cells connect there is a continuation of the sarcomeric structure across cell membranes.

The end junctions of epithelial sheath cells contain Integrin and Ilk as well as low levels of Zasp proteins and other Z-disc components (Fig. 6). This is unlike intercalated discs at cardiac cell end junctions that contain adherens junction proteins. Integrin is a component of costameres, which are peripheral Z-disc structures that link sarcomeres to the plasma membrane and serve to transmit contractile force to the extracellular matrix (ECM) (Frank et al., 2006). We found that Integrin linked kinase has a similar peripheral localization around Z-discs, and is also present at end junctions. The presence of costamere-associated proteins at the end junctions suggests that communication between cells is also mediated by costameres.

Genetic studies of Integrin mutations in Drosophila have revealed dramatic defects in the attachment of somatic muscles to each other, revealing that muscle cells are attached via the ECM (Brown et al., 2000). Integrin linked kinase mutations also display muscle detachment, in this case because the actin cytoskeleton detaches from the ends of muscles (Zervas et al., 2001). In gut visceral muscles, Integrin mutations cause detachment of the muscle layers from underlying endoderm as well as detachment of sheets of circular visceral muscles; however, it is unclear whether these phenotypes are caused by defects in migration of primordial endodermal cells or in visceral muscle attachment (Brown et al., 2000; Martin-Bermudo et al., 1999). Genetic analysis in epithelial sheath cells can now be carried out to determine exactly how Integrin and Integrin linked kinase contribute to attachment of these muscle cells.

Labeling of epithelial sheath cells with antibodies to Filamin was very useful for viewing the highly mesh-like shape of the cells (Fig. 8). The cytoplasm of the cells closely surrounds each sarcomere with large gaps between sarcomeres connected by thin cytoplasmic bridges. This type of cellular structure appears typical of Drosophila visceral muscles, which carry out functions analogous to smooth muscle in higher animals. The Filamin isoform expressed in these cells, FLN12−20, does not contain an actin-binding domain (Sokol and Cooley, 1999) and is not specifically associated with F-actin (Fig. 5). Nonetheless, sarcomeric actin in cells that have low levels of FLN12−20 has a different appearance compared to sarcomeric actin in cells with high FLN12−20, suggesting an actin-related function for this Filamin isoform. In humans, the FLNC isoform is expressed in skeletal, smooth and cardiac muscles (Feng and Walsh, 2004; Small et al., 1986), although its role in these muscles is unknown. Mutations in other Filamin isoforms are associated with diseases. FLNA mutations cause periventricular heterotopia, a brain malformation with failure in neuron migration during development (Feng and Walsh, 2004), and mutations in FLNB cause skeletal dysplasias (Krakow et al., 2004). Genetic analysis of Filamin in epithelial sheath cells can now be carried out to determine the role of FLN12−20 in these muscle cells.

Mononucleate muscle

Determining the number of nuclei in muscle cells can be challenging. The highly organized somatic muscles of insects, analogous to vertebrate skeletal muscle, have multiple nuclei as a result of myoblast fusion during development. However, the number of nuclei per cell in visceral muscles is much less apparent morphologically, and was therefore harder to determine. Before 2001, the circular gut visceral muscles were reported to be mononuclear (Brown et al., 2000; Elder, 1975). In 2001, two assays for myoblast fusion were used to discover that circular visceral muscles of the gut are actually the product of cell fusion (Klapper et al., 2001; Martin et al., 2001). A cell transplantation technique was used to show that gut circular and longitudinal muscle cells have exactly two nuclei. Cells from embryos expressing UAS-GFP were transferred into recipients with ubiquitous expression of Gal4 (da-Gal4). GFP expression was produced exclusively in syncytia resulting from fusion of the transplanted cell with a cell in the recipient. GFP-positive visceral muscle cells were found that always had two nuclei (Klapper et al., 2001). Similar results were obtained using a dye-filling approach (Martin et al., 2001). In addition, the formation of gut visceral muscle syncytia depends on duf, sns and mbc, the same genes involved with somatic myoblast fusion (Klapper et al., 2002).

The mesh-like morphology of visceral muscles in the ovary is similar to gut muscles, and epithelial sheath cells have been reported to be multinucleate (Hartenstein, 2006; King, 1970), although this latter point was not investigated in detail. These similarities between gut muscle and epithelial sheath cells suggested that visceral cells have a common developmental program. However, our data provide convincing evidence that the epithelial sheath cells are mononucleate. Our evidence includes the ability to mark the cell bodies, nuclei and cell boundaries with a panel of antibodies and GFP-tagged proteins. We can now recognize the end junctions of cells by discontinuities in sarcomeric organization alone. The most reliable marker of cell outlines is the protein trap insertion in the Fas3 gene, which provides expression of Fas3 in dots at both lateral and end junctions of epithelial sheath cells. This attests to the remarkable utility of protein traps for identifying new and useful cellular markers. The final piece of evidence that epithelial sheath cells contain a single nucleus is the ability to generate marked mitotic clones at high frequency. Thus, our data show that epithelial sheath cells are actually mononuclear and therefore differentiate without first going through a myoblast fusion step. It remains to be determined whether peritoneal sheath cells are similarly mononuclear. The availability of mononuclear differentiated muscle cells provides an experimental model system for examining the effects on muscle function of mutations in individual cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Baylies for many helpful comments and several Gal4 driver lines, Dylan Burnette for help with Meta Morph rendering, Judith Saide for Projectin and α-Actinin antibodies, Katie Mellman for help with initial characterization of protein trap line expression, and members of the Cooley lab for comments on the manuscript. This project was supported by NIH research grant GM43301 to L.C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Material

Movie 1. Rotation view of a Z-series of confocal images through an ovariole stained with CFLN antibodies (red) and expressing Fas3::GFP and Meso18::GFP (green). 120 maximum intensity projection images of the Z-series were recorded at 3 degree intervals around the stack and imported into a Quicktime movie at 15 frames per second.

Movie 2. Rotation view of Z-series of rendered confocal images in which the expression of GFP from Fas3::GFP and Meso18::GFP was rendered in blue dots for one half the stack and red dots in the other half. 120 images of the Z-series projection were recorded at 3 degree intervals around the stack and imported into a Quicktime movie at 15 frames per second.

Supplemental Information

Figure S1. Cellular organization of oviduct muscle. Oviduct muscles expressing myrRFP under the control of the Mef2 Gal4 driver (green) were stained with phalloidin to view F-actin (red) and DAPI to view nuclei (blue). Mef2>myrRFP expression was high at the plasma membrane and also present on internal membranes. Several nuclei are visible in each cell.

Figure S2. Ilk::GFP is enriched at the membranes surrounding Z-discs. (A) Oviduct muscles are comprised of ∼ 4 μ thick sarcomeric bundles, and confocal projection images of Ilk::GFP localization often reveals rings encircling the Z-discs (yellow arrowheads). In addition, oviduct muscle cells form end-on-end attachments that show high levels of Ilk::GFP, much like epithelial sheath cell end-junctions. However, Fas3::GFP is not present at these junctions (data not shown). (B) Higher magnification confocal projection of Ilk::GFP at two Z-discs. (C-C”) 90 ° rotation of the Z-discs shown in B, revealing Ilk::GFP as a peripheral component of the Z-disc, presumably costameres. (D) Ilk::GFP localization in a confocal section of indirect flight muscle, showing dots associated with presumed costameres at the periphery of Z-discs. Scale bars in A and D: 10 μ; B and C: 2 μ.

References

- Beckett K, Baylies MK. The development of the Drosophila larval body wall muscles. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2006;75:55–70. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)75003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair SS. Genetic mosaic techniques for studying Drosophila development. Development. 2003;130:5065–72. doi: 10.1242/dev.00774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bour BA, Chakravarti M, West JM, Abmayr SM. Drosophila SNS, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that is essential for myoblast fusion. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1498–511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NH, Gregory SL, Martin-Bermudo MD. Integrins as mediators of morphogenesis in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2000;223:1–16. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkart C, Qiu F, Brendel S, Benes V, Haag P, Labeit S, Leonard K, Bullard B. Modular proteins from the Drosophila sallimus (sls) gene and their expression in muscles with different extensibility. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:953–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buszczak M, et al. The carnegie protein trap library: a versatile tool for Drosophila developmental studies. Genetics. 2007;175:1505–31. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.065961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen EH, Olson EN. Towards a molecular pathway for myoblast fusion in Drosophila. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:452–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba A, Snow P, Keshishian H, Hotta Y. Fasciclin III as a synaptic target recognition molecule in Drosophila. Nature. 1995;374:166–8. doi: 10.1038/374166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KA, McElhinny AS, Beckerle MC, Gregorio CC. Striated muscle cytoarchitecture: an intricate web of form and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:637–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.012502.105840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang DT, Perrimon N. Use of a yeast site-specific recombinase to generate embryonic mosaics in Drosophila. Dev Genet. 1992;13:367–75. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020130507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder HY. Muscle structure. In: Usherwood PNR, editor. Insect muscle. Academic Press; New York: 1975. pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Engel FB, Schebesta M, Keating MT. Anillin localization defect in cardiomyocyte binucleation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:601–12. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner G, et al. ZASP: a new Z-band alternatively spliced PDZ-motif protein. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:465–75. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Walsh CA. The many faces of filamin: a versatile molecular scaffold for cell motility and signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1034–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1104-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank D, Kuhn C, Katus HA, Frey N. The sarcomeric Z-disc: a nodal point in signalling and disease. J Mol Med. 2006;84:446–68. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godt D, Laski FA. Mechanisms of cell rearrangement and cell recruitment in Drosophila ovary morphogenesis and the requirement of bric a brac. Development. 1995;121:173–87. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griggs R, et al. Zaspopathy in a large classic late-onset distal myopathy family. Brain. 2007;130:1477–84. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein V. The muscle patern of Drosophila. In: Sink H, editor. Muscle Development in Drosophila. Landes Bioscience/Eurekah.com; Georgetown, TX: 2006. pp. 8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, et al. Characterization and in vivo functional analysis of splice variants of cypher. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7360–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211875200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson AM, Cooley L. Understanding the function of actin-binding proteins through genetic analysis of Drosophila oogenesis. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:455–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.052802.114101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso RJ, Buszczak M, Quinones AT, Castiblanco C, Mazzalupo S, Cooley L. Flytrap, a database documenting a GFP protein-trap insertion screen in Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D418–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RC. Ovarian development in Drosophila melanogaster. Academic Press; New York: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Klapper R, Heuser S, Strasser T, Janning W. A new approach reveals syncytia within the visceral musculature of Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 2001;128:2517–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.13.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapper R, Stute C, Schomaker O, Strasser T, Janning W, Renkawitz-Pohl R, Holz A. The formation of syncytia within the visceral musculature of the Drosophila midgut is dependent on duf, sns and mbc. Mech Dev. 2002;110:85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakow D, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding filamin B disrupt vertebral segmentation, joint formation and skeletogenesis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:405–10. doi: 10.1038/ng1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey A, Ferguson C, Labeit S, Reedy M, Larkins A, Butcher G, Leonard K, Bullard B. Identification and localization of high molecular weight proteins in insect flight and leg muscle. Embo J. 1990;9:3459–67. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahowald AP, Kambysellis MP. Oogenesis. In: Ashburner M, Wright TRF, editors. The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. 2D. Academic Press; London: 1980. pp. 141–224. [Google Scholar]

- Martin BS, Ruiz-Gomez M, Landgraf M, Bate M. A distinct set of founders and fusion-competent myoblasts make visceral muscles in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 2001;128:3331–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.17.3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Bermudo MD, Alvarez-Garcia I, Brown NH. Migration of the Drosophila primordial midgut cells requires coordination of diverse PS integrin functions. Development. 1999;126:5161–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton CA, Nongthomba U, Parry K, Sweeney ST, Sparrow JC, Elliott CJ. Neuromuscular organization and aminergic modulation of contractions in the Drosophila ovary. BMC Biol. 2006;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin X, Daneman R, Zavortink M, Chia W. A protein trap strategy to detect GFP-tagged proteins expressed from their endogenous loci in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15050–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261408198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiñones-Coello AT, et al. Exploring strategies for protein trapping in Drosophila. Genetics. 2007;175:1089–104. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.065995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganayakulu G, Schulz RA, Olson EN. Wingless signaling induces nautilus expression in the ventral mesoderm of the Drosophila embryo. Dev Biol. 1996;176:143–8. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.9987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Valentin R, Lopez-Gonzalez I, Jorquera R, Labarca P, Zurita M, Reynaud E. Oviduct contraction in Drosophila is modulated by a neural network that is both, octopaminergic and glutamatergic. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:183–98. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Gomez M, Coutts N, Price A, Taylor MV, Bate M. Drosophila dumbfounded: a myoblast attractant essential for fusion. Cell. 2000;102:189–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saide JD, Chin-Bow S, Hogan-Sheldon J, Busquets-Turner L, Vigoreaux JO, Valgeirsdottir K, Pardue ML. Characterization of components of Z-bands in the fibrillar flight muscle of Drosophila melanogaster. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2157–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selcen D, Engel AG. Mutations in ZASP define a novel form of muscular dystrophy in humans. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:269–76. doi: 10.1002/ana.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton K, Woodruff RI. The osmolarity of adult Drosophila hemolymph and its effect on oocyte-nurse cell electrical polarity. Dev Biol. 1994;161:154–67. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sink H. Muscle Development in Drosophila. Landes Bioscience / Eurekah.com; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Small JV, Furst DO, De Mey J. Localization of filamin in smooth muscle. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:210–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.1.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow PM, Bieber AJ, Goodman CS. Fasciclin III: a novel homophilic adhesion molecule in Drosophila. Cell. 1989;59:313–23. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol NS, Cooley L. Drosophila filamin encoded by the cheerio locus is a component of ovarian ring canals. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1221–30. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MV. A novel Drosophila, mef2-regulated muscle gene isolated in a subtractive hybridization-based molecular screen using small amounts of zygotic mutant RNA. Dev Biol. 2000;220:37–52. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatta M, et al. Mutations in Cypher/ZASP in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular non-compaction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:2014–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigoreaux JO. Genetics of the Drosophila flight muscle myofibril: a window into the biology of complex systems. Bioessays. 2001;23:1047–63. doi: 10.1002/bies.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Rubin GM. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas CG, Gregory SL, Brown NH. Drosophila integrin-linked kinase is required at sites of integrin adhesion to link the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1007–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Chu PH, Huang C, Cheng CF, Martone ME, Knoll G, Shelton GD, Evans S, Chen J. Ablation of Cypher, a PDZ-LIM domain Z-line protein, causes a severe form of congenital myopathy. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:605–12. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie 1. Rotation view of a Z-series of confocal images through an ovariole stained with CFLN antibodies (red) and expressing Fas3::GFP and Meso18::GFP (green). 120 maximum intensity projection images of the Z-series were recorded at 3 degree intervals around the stack and imported into a Quicktime movie at 15 frames per second.

Movie 2. Rotation view of Z-series of rendered confocal images in which the expression of GFP from Fas3::GFP and Meso18::GFP was rendered in blue dots for one half the stack and red dots in the other half. 120 images of the Z-series projection were recorded at 3 degree intervals around the stack and imported into a Quicktime movie at 15 frames per second.

Supplemental Information

Figure S1. Cellular organization of oviduct muscle. Oviduct muscles expressing myrRFP under the control of the Mef2 Gal4 driver (green) were stained with phalloidin to view F-actin (red) and DAPI to view nuclei (blue). Mef2>myrRFP expression was high at the plasma membrane and also present on internal membranes. Several nuclei are visible in each cell.

Figure S2. Ilk::GFP is enriched at the membranes surrounding Z-discs. (A) Oviduct muscles are comprised of ∼ 4 μ thick sarcomeric bundles, and confocal projection images of Ilk::GFP localization often reveals rings encircling the Z-discs (yellow arrowheads). In addition, oviduct muscle cells form end-on-end attachments that show high levels of Ilk::GFP, much like epithelial sheath cell end-junctions. However, Fas3::GFP is not present at these junctions (data not shown). (B) Higher magnification confocal projection of Ilk::GFP at two Z-discs. (C-C”) 90 ° rotation of the Z-discs shown in B, revealing Ilk::GFP as a peripheral component of the Z-disc, presumably costameres. (D) Ilk::GFP localization in a confocal section of indirect flight muscle, showing dots associated with presumed costameres at the periphery of Z-discs. Scale bars in A and D: 10 μ; B and C: 2 μ.