Abstract

TrpY binds specifically to TRP box sequences upstream of trpB2, but the repression of trpB2 transcription requires additional TrpY assembly that is stimulated by but not dependent on the presence of tryptophan. Inhibitory complex formation is prevented by insertions within the regulatory region and by a G149R substitution in TrpY, even though TrpY(G149R) retains both TRP box DNA- and tryptophan-binding abilities.

Investigations of tryptophan gene (trp) expression have resulted in the discovery of many different regulatory systems in Bacteria and Eukarya (2, 3, 7, 14, 26, 29), and with these precedents, we have focused on determining how archaeal trp gene expression is regulated, specifically that in Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus. We have established that a tryptophan-sensing regulator, TrpY, represses the transcription of the tryptophan biosynthetic operon (trpEGCFBAD) in M. thermautotrophicus in the presence of tryptophan (28). The TrpY-encoding gene (trpY) is located immediately upstream and transcribed divergently from the trpEGCFBAD operon. TrpY binds to TRP box sequences (consensus, TGTACA) located between trpY and trpE, autorepressing trpY transcription in the absence of tryptophan and repressing both trpY and trpEGCFBAD transcription in the presence of tryptophan (8, 28). Constitutive trpEGCFBAD expression results in resistance to 5-methyltryptophan, and many 5-methyltryptophan-resistant mutants of M. thermautotrophicus have been isolated previously, almost all of which have mutations in trpY (8). Assays of the encoded TrpY variants have identified residue substitutions that eliminate DNA- or tryptophan-binding, consistent with the prediction that TrpY has an N-terminal helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain and a C-terminal tryptophan-binding ACT domain (1, 2, 9, 13). Generically, the archaeal repressors studied to date fall into two groups, those that bind to sequences that overlap the BRE-TATA box region of an archaeal promoter and so block binding by the basal transcription factors transcription factor B (TFB) and TATA-binding protein (TBP) and those that bind to the site of transcription initiation and so prevent RNA polymerase access (5, 12). In this regard, TrpY appears to repress trpY transcription by binding to a site that overlaps the site of trpY transcription initiation (28), but its regulation of trpEGCFBAD transcription is more complex. Repression requires TRP box binding, the presence of tryptophan, and an additional event, as some of the TrpY variants isolated based on their inability to repress trpEGCFBAD transcription still bind both DNA and tryptophan (8).

Efforts to further dissect the TrpY regulation of trpEGCFBAD transcription have been impeded by the presence of two overlapping and divergent TrpY-regulated promoters within the trpY-trpE intergenic region. Fortunately, M. thermautotrophicus has a second trpB gene (MTH1476, designated trpB2) (17, 22, 26) located remotely from the trpY-trpEGCFBAD region. TrpB2 is synthesized in vivo (10), and trpB2 transcription is regulated by TrpY and tryptophan (28), but the trpB2 promoter region lacks the complexity of a second, divergent TrpY-regulated promoter. Consistent with TrpY regulation, there are two canonical TRP box sequences separated by 4 bp upstream of trpB2, but this TrpY-binding site is located upstream of the BRE-TATA box region and also distant from the site of transcription initiation (Fig. 1A). The experiments reported herein were undertaken to determine how TrpY regulates trpB2 expression.

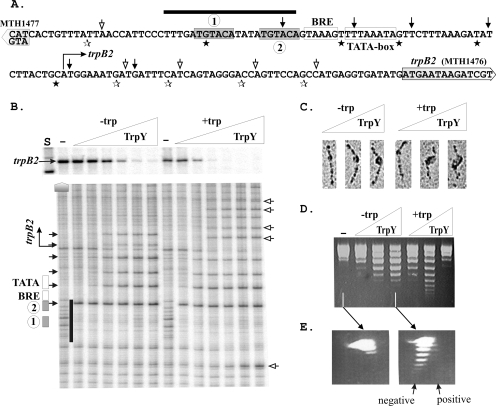

FIG. 1.

TrpY regulation of trpB2 transcription, DNase I protection, electron microscopy analyses, and topology of TrpY complexes. (A) Sequence of the intergenic region between trpB2 (MTH1476) (17, 26) and MTH1477 (22) with the TRP boxes 1 and 2 and trpB2 promoter regulatory elements boxed and identified. The locations of the DNase I-hypersensitive sites introduced by TrpY binding into the DNA strand shown (filled arrows) and into the complementary strand (filled stars) and the additional sites introduced by TrpY in the presence of tryptophan (open arrows and open stars) are indicated. The sequence protected from DNase I digestion by TrpY binding to the TRP box region is overlined. (B) 32P-labeled trpB2 transcripts synthesized in vitro in single-round runoff transcription reactions from the template T147, positioned above DNase I footprints. Transcription reaction mixtures containing 5 nM T147 were assembled as previously described (21) and incubated for 5 min at 60°C in the absence (−) or presence (triangles) of 5, 25, 50, 100, 250, or 500 nM TrpY, without (−trp) or with (+trp) 24 μM l-tryptophan present. The transcripts synthesized were purified, separated by denaturing gel electrophoresis, and visualized by phosphorimaging as previously described (21). Size standards were run in adjacent lanes (S). TrpY-T147 complexes assembled under the same transcription conditions, but using T147 DNA end labeled with 32P, were subjected to DNase I digestion, and the DNA fragments generated were separated by electrophoresis and visualized by phosphorimaging. In the figure, the gels are positioned so that the amount of transcript accumulated and the footprint obtained at each TrpY-to-T147 ratio are vertically aligned. As in panel A, the boxes, arrows, and lines identify the locations of the trpB2 transcription regulatory elements, DNase I-hypersensitive sites, and the TRP box region DNase I footprint. (C) EM visualization of complexes (16, 23) formed by TrpY binding to T147 DNA in transcription buffer at TrpY-to-DNA molar ratios of 10, 20, and 50, in the absence (−trp) or presence (+trp) of tryptophan. (D) Electrophoretic separation of topoisomers of pKS795 generated by TrpY binding to relaxed, circular pKS795 DNA in the absence or presence of tryptophan. Plasmid pKS795 was constructed by cloning the intergenic TRP box-containing DNA region into the multiple cloning site of pLITMUS28. Aliquots (0.5 μg) of relaxed circular plasmid DNA were incubated without TrpY (−) or with 0.4, 1.2, or 4 μg of TrpY (triangles) in the absence (−trp) or presence (+trp) of 50 μM tryptophan for 10 min at 37°C. The complexes formed were incubated with topoisomerase and deproteinated, and the resulting topoisomers were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis as previously described (18). (E) 2D agarose gel electrophoretic separation of relaxed (−) and supercoiled pKS795 molecules. Aliquots of the DNA preparations subjected to 1D electrophoresis, identified by the connecting arrows from panel D, were subjected to 2D gel electrophoresis. The presence of ethidium bromide during electrophoresis in the second dimension (rightward) results in faster migration of positively supercoiled relative to negatively supercoiled molecules with the same superhelical density (6, 18).

TrpY repression of trpB2 transcription and DNase I footprint analysis of the trpB2 promoter.

A DNA molecule, designated T147, that contained the MTH1477-trpB2 intergenic region (63 bp) plus 280 bp of trpB2 and 180 bp of MTH1477 was amplified from M. thermautotrophicus genomic DNA (22). It was cloned into plasmid pCR2.1 TOPO by using a TOPO cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), resulting in plasmid pLK147, from which T147 was obtained, either by plasmid amplification in Escherichia coli or directly in vitro by PCR amplification. The gene (MTH1477) upstream from trpB2 (MTH1476) is annotated as encoding a conserved protein, but when T147 and several other DNA molecules were used as the template DNA, transcription in vitro in the direction of MTH1477 was never observed. In contrast, transcription from the trpB2 promoter occurred robustly in vitro in reaction mixtures assembled as previously described that contained T147, M. thermautotrophicus RNA polymerase, and recombinant versions of M. thermautotrophicus TFB and TBP (21). Transcription in the presence of [32P]UTP resulted in the accumulation of radioactively labeled runoff transcripts that were purified, separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and then visualized and quantified by phosphorimaging as described previously (21). The addition of TrpY inhibited trpB2 transcription from T147 in both the absence and the presence of tryptophan, but inhibition occurred at a lower TrpY concentration with tryptophan present (Fig. 1B). TrpY is a dimer in solution (28), and trpB2 transcript accumulation was reduced ∼50% at (TrpY)2-to-T147 molar ratios of 7 and 20 in the presence and absence of tryptophan, respectively. DNase I footprint analysis of TrpY bound to T147 revealed that this did not result from a difference in initial TrpY binding, but difference from a difference in subsequent complex formation (Fig. 1B). At TrpY concentrations that did not reduce trpB2 transcription, TrpY bound and introduced DNase I-hypersensitive sites into the TRP box sequences and protected the TRP box region from DNase I digestion. At higher TrpY concentrations, TrpY binding introduced additional DNase I-hypersensitive sites and the DNase I footprint extended toward the site of transcription initiation. Inhibition of trpB2 transcription occurred when the TrpY footprint and hypersensitive sites extended to the site of transcription initiation (Fig. 1B), and this extension occurred at a lower TrpY-to-template DNA ratio when tryptophan was present. TrpY binding in the presence of tryptophan also changed the pattern of DNase I-hypersensitive sites at the site of transcription initiation and introduced additional hypersensitive sites, both upstream of the promoter and downstream from the site of transcription initiation. The locations of the DNase I-hypersensitive sites introduced by TrpY binding are identified in Fig. 1A. They are regularly spaced, at ∼10-bp intervals, and many occur at TA (or AT) dinucleotides, consistent with TrpY binding's resulting in a DNase I-accessible DNA distortion once per helical turn (15) and with TA's being the dinucleotide that most readily accepts distortion (11, 25).

EM analysis and topology of TrpY-trpB2 promoter complexes.

Complexes formed by TrpY binding to linear DNA molecules that contained the MTH1477-trpB2 intergenic region, in the presence or absence of tryptophan, were fixed in glutaraldehyde, spread onto mica, and visualized by electron microscopy (EM) as described previously (16, 23). TrpY binding occurred at one location, which DNA length measurements confirmed coincided with the location of the TRP box region. The complexes formed increased in size with increasing TrpY concentrations, and at the same TrpY-to-DNA ratios, the complexes formed in the presence of tryptophan were larger than those formed in the absence of tryptophan (Fig. 1C). Even with a large complex present, the length of the DNA was reduced by <20%, arguing against DNA wrapping or circularization, but TrpY binding to relaxed circular DNA molecules did introduce negative superhelicity. Complexes formed by TrpY binding to relaxed circular DNA molecules were incubated with topoisomerase and deproteinized, and the plasmid topoisomers generated were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized as described previously (18). Consistent with the assembly of larger complexes that involved more DNA, TrpY binding in the presence of tryptophan introduced more supercoils than TrpY binding in the absence of tryptophan (Fig. 1D). At the highest concentrations of TrpY assayed, the complexes formed with tryptophan present were apparently so compact that the topoisomerase could not gain access and so remove the plectonemic supercoils formed in the plasmid DNA (6). Two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoretic separation of the topoisomers formed (Fig. 1E) revealed that TrpY binding in either the absence or the presence of tryptophan introduced negative superhelicity into the plasmid DNA.

Sequence requirements for TrpY binding and trpB2 repression.

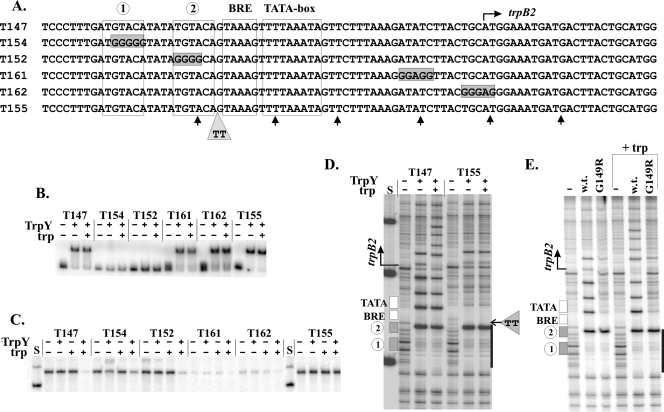

Oligonucleotide-directed site-specific mutagenesis was used to generate derivatives of plasmid pLK147 with mutations introduced into the trpB2 promoter region, and DNA molecules designated T152, T154, T155, T161, and T162 were generated by PCR amplification from these plasmids (Fig. 2A). Electrophoretic mobility gel shift assays (EMSA) of TrpY binding to these DNA molecules confirmed that both the TRP box 1 and 2 sequences were required for TrpY binding to form a complex sufficiently stable to give a gel shift and that the binding occurred with or without tryptophan present (Fig. 2B). When these DNA molecules were used as templates, trpB2 transcripts were transcribed from all of them, but transcription from T161 and T162 was very limited. T161 and T162 were designed to remove AT dinucleotides at which TrpY binding introduced hypersensitive sites (Fig. 2A), but this removal also changed the sequence of a region that contributes to TFB binding (4, 20, 24) and so to preinitiation complex assembly and stability. Under conditions in which TrpY binding in the presence of tryptophan completely inhibited trpB2 transcription from the wild-type template (T147), TrpY plus tryptophan only partially inhibited trpB2 transcription from templates T152 and T154, which had mutations in the TRP box 1 and 2 sequences, respectively (Fig. 2B). TrpY in the presence of tryptophan did, therefore, bind to these templates to form complexes with sufficient stability to reduce transcription but with insufficient stability to give a gel shift. Definitive results were obtained with templates with insertions between the known regulatory elements but within the regulatory region. As illustrated in Fig. 2 by T155, a template with just 2 bp inserted between the TRP box 2 and BRE sequences, EMSA confirmed that TrpY bound and formed a stable complex but that this binding had no inhibitory effect on trpB2 transcription in the absence or presence of tryptophan (Fig. 2B and C). DNase I protection experiments also confirmed that TrpY bound to the TRP box region but that there was no extension of the DNase I footprint and no introduction of additional downstream hypersensitive sites with increasing TrpY concentrations in the absence or presence of tryptophan (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

EMSA of TrpY binding, trpB2 transcription and DNase I footprint analysis of mutated DNA templates. (A) Sequences of the trpB2 regulatory region of the templates used, with the differences from the wild-type sequence (T147) identified. The locations of the DNase I-hypersensitive sites introduced into T147 by TrpY binding are indicated (↑). (B) EMSA of the complexes formed in reaction mixtures that contained 100 pM TrpY (+) and 1 fmol of 32P-labeled template DNA in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 24 μM tryptophan (trp). (C) trpB2 transcripts synthesized in single-round reaction mixtures, incubated for 5 min at 60°C, and assembled as previously described (21), in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 100 nM TrpY and the absence (−) or presence (+) of 24 μM tryptophan. Control lanes (S) contained size standards. (D) Electrophoretic separation of the DNase I digestion products of T147 and T155 generated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of TrpY at a 20:1 molar ratio of TrpY to DNA, with (+) or without (−) tryptophan (trp) present. The locations of the trpB2 regulatory elements and the 2-bp insertion in T155 are indicated. The heavy line identifies the TRP box region protected by TrpY binding, as shown in Fig. 1A. The control lane (S) contained size standards. (E) Electrophoretic separation of the DNase I digestion products of T147 generated in reaction mixtures lacking (−) or containing wild-type (w.t.) TrpY or TrpYG149R, at 20-to-1 molar ratios with the DNA, with (+trp) or without tryptophan present.

TrpYG149R binds to the TRP box sequences but does not inhibit trpB2 transcription.

TrpY with a G149R substitution (TrpYG149R) was isolated as a variant that allowed the constitutive expression of the trpEGCFBAD operon (8). Consistent with this finding, TrpYG149R lacks the ability to repress trpEGCFBAD transcription in vivo and in vitro but, surprisingly, still binds both TRP box DNA and tryptophan (8). The addition of TrpYG149R also had no inhibitory effect on trpB2 transcription in vitro from T147 in the presence or absence of tryptophan (result not shown). DNase I protection experiments confirmed that TrpYG149R bound to the TRP box region of the trpB2 promoter (Fig. 2E) but that, even at high concentrations, TrpYG149R binding to T147 did not generate a footprint that extended beyond this region and did not introduce additional downstream DNase I-hypersensitive sites (Fig. 2E). The DNase I footprints obtained from complexes formed by the binding of TrpYG149R to the wild-type sequence (T147) were essentially identical to those generated by the binding of wild-type TrpY to the T155 template (Fig. 2D and E).

Conclusions and discussion.

The results obtained demonstrate that TrpY binds to the TRP box sequences upstream of the BRE-TATA box region of the trpB2 promoter but that this binding alone does not inhibit trpB2 promoter activity. TrpY binding to the TRP boxes provides a nucleation point for the further assembly of TrpY molecules. When formed, the larger complex incorporates the BRE-TATA box region and the site of transcription initiation (Fig. 1A), and this incorporation does inhibit trpB2 transcription. The assembly of a larger complex occurs at a lower TrpY concentration in vitro in the presence than in the absence of tryptophan. As the assembly of this complex introduces DNase I-hypersensitive sites at ∼10-bp intervals, complex formation must cause a DNA distortion once per helical turn (15). Insertions within the regulatory region eliminate complex formation, arguing that the rotational positioning of sequences, most likely those containing TA dinucleotides, downstream from TRP box nucleation sites is also required for complex formation. Changes made to the transcribed sequence, beginning immediately downstream from the site of transcription initiation, had no effect on TrpY regulation of the trpB2 promoter, arguing that all of the essential TrpY binding and regulatory information is present within the intergenic region. Also consistent with this conclusion, TrpY bound tightly to the intergenic region in the presence of excess poly(dI:dC) but TrpY plus tryptophan binding did not introduce additional DNase I-hypersensitive sites downstream from the site of transcription initiation in the presence of this nonspecific competitor DNA (results not shown).

These TrpY results add to a growing number of observations in which an archaeal regulator binds initially in a sequence-specific manner and this binding provides the foundation for additional regulator assembly to form a larger transcription-regulating complex (19, 30). TrpY binding and larger-complex assembly do not require tryptophan, but the presence of the effector ligand stimulates assembly at a lower TrpY concentration. The overall architecture of the large complex formed remains to be determined, but its assembly requires a structure or activity that is lost in TrpYG149R. The use of higher-order complex assembly to repress archaeal promoter function, rather than a direct promoter-binding competition with the transcription machinery, likely reflects the eukaryotic features of the archaeal transcription initiation system, features not conserved in Bacteria (4, 5, 12, 20, 24). Archaeal TBP (27), and possibly also TFB, is likely to be always bound and assembled into preinitiation complexes at archaeal promoters in vivo, unless displaced by regulators. A regulator bound to a sequence adjacent to, but not overlapping, the BRE-TATA box region would not prevent and may even enhance TBP and TFB binding. It would not repress promoter function unless stimulated to assemble into a larger complex that distorted and incorporated the BRE-TATA and so displaced the basal transcription initiation factors. For TrpY, larger-complex assembly is stimulated by tryptophan but is dependent on the TrpY concentration, and in this regard, TrpY binds to the site of trpY transcription initiation and so does directly block trpY transcription (24). This autoregulation must limit TrpY accumulation to an intracellular concentration insufficient for larger-complex assembly, and so for the displacement of TFB and TBP from the trpB2 promoter in the absence of tryptophan, but sufficient for assembly, and so for the rapid imposition of repression if exogenous tryptophan becomes available. TrpY regulation of transcription of the trpEGCFBAD operon most likely also involves additional TrpY binding, but this must occur without conflicting with the divergent trpY transcription.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant DE-FG02-87ER13731 from the Department of Energy (to J.N.R.) and by NSF postdoctoral fellowship 0400072 awarded to E.A.K.

We thank T. J. Santangelo for advice and help with the in vitro transcription experiments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 February 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aravind, L., and E. V. Koonin. 1999. Gleaning non-trivial structural, functional and evolutionary information about proteins by iterative database searches. J. Mol. Biol. 2871023-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind, L., and E. V. Koonin. 1999. DNA-binding proteins and evolution of transcription regulation in archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 274658-4670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babitzke, P. 2004. Regulation of transcription attenuation and translation initiation by allosteric control of an RNA-binding protein: the Bacillus subtilis TRAP protein. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7132-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartlett, M. S. 2005. Determinants of transcription initiation by archaeal RNA polymerase. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8677-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell, S. D. 2005. Archaeal transcriptional regulation—variation on a bacterial theme? Trends Microbiol. 13262-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broyles, S. S., and D. E. Pettijohn. 1986. Interaction of the Escherichia coli HU protein with DNA. Evidence for formation of nucleosome-like structures with altered DNA helical pitch. J. Mol. Biol. 18747-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford, I. P. 1989. Evolution of a biosynthetic pathway: the tryptophan paradigm. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 43567-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cubonova, L., K. Sandman, E. A. Karr, A. J. Cochran, and J. N. Reeve. 2007. Spontaneous trpY mutants and mutational analysis of the TrpY archaeal transcription regulator. J. Bacteriol. 1894338-4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ettema, T. J. G., A. B. Brinkman, T. H. Tani, J. B. Rafferty, and J. van der Oost. 2002. A novel ligand-binding domain involved in regulation of amino acid metabolism in prokaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 27737464-37468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farhoud, M. H., H. J. C. T. Wessels, P. J. M. Steenbakkers, S. Mattijssen, R. A. Wevers, B. G. van Engelen, M. S. M. Jetten, J. A. Smeitink, L. P. van den Heuvel, and J. T. Keltjens. 2005. Protein complexes in the archaeon Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus analyzed by blue native/SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 41653-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald, D. J., and J. N. Anderson. 1999. DNA distortion as a factor in nucleosome positioning. J. Mol. Biol. 293477-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geiduschek, E. P., and M. Ouhammouch. 2005. Archaeal transcription and its regulators. Mol. Microbiol. 561397-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gelfand, M. S., E. V. Koonin, and A. A. Mironov. 2000. Prediction of transcription regulatory sites in Archaea by a comparative genomic approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 28695-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutter, R., P. Niederberger, and J. A. DeMoss. 1986. Tryptophan biosynthetic genes in eukaryotic microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 4055-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jafri, S., S. Evoy, K. Cho, H. G. Craighead, and S. C. Winans. 1999. An Lrp-type transcriptional regulator from Agrobacterium tumefaciens condenses more than 100 nucleotides of DNA into globular nucleoprotein complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 288811-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koller, T., J. M. Sogo, and H. Bujard. 1974. An electron microscopic method for studying nucleic acid-protein complexes. Visualization of RNA polymerase bound to DNA of bacteriophages T7 and T3. Biopolymers 13995-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merkl, R. 2007. Modelling the evolution of the archaeal tryptophan synthase. BMC Evol. Biol. 759-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musgrave, D. R., K. M. Sandman, and J. N. Reeve. 1991. DNA binding by the archaeal histone HMf results in positive supercoiling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 8810397-10401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peeters, E., R. Willaert, D. Maes, and D. Charlier. 2006. Ss-LrpB from Sulfolobus solfataricus condenses about 100 base pairs of its own operator DNA into globular nucleoprotein complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 28111721-11728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renfrow, M. B., N. Naryshkin, L. M. Lewis, H.-T. Chen, R. H. Ebright, and R. A. Scott. 2004. Transcription factor B contacts promoter DNA near the transcription start site of the archaeal transcription initiation complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2792825-2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santangelo, T. J., and J. N. Reeve. 2006. Archaeal RNA polymerase is sensitive to intrinsic termination directed by transcribed and remote sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 355196-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith, D. R., L. A. Doucette-Stamm, C. DeLoughery, H. Lee, J. Dubois, T. Aldredge, R. Bashirzadeh, D. Blakely, R. Cook, K. Gilbert, D. Harrison, L. Hoang, P. Keagle, W. Lumm, B. Pothier, D. Qiu, R. Spadafora, R. Vicaire, Y. Wang, J. Wierzbowski, R. Gibson, N. Jiwani, A. Caruso, D. Bush, H. Safer, D. Patwell, S. Prabhakar, S. McDougall, G. Shimer, A. Goyal, S. Pietrokovski, G. Church, C. J. Daniels, J. Mao, P. Rice, J. Nölling, and J. N. Reeve. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J. Bacteriol. 1797135-7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spiess, E., and R. Lurz. 1988. Electron microscopic analysis of nucleic acids and nucleic acid-protein complexes. Methods Microbiol. 20293-323. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitalny, P., and M. Thomm. 2003. Analysis of the open region and of DNA-protein contacts of archaeal RNA polymerase transcription complexes during transition from initiation to elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 27830497-30505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Widom, J. 1998. Structure, dynamics, and function of chromatin in vitro. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 27285-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie, G., N. O. Keyhani, C. A. Bonner, and R. A. Jensen. 2003. Ancient origin of the tryptophan operon and the dynamics of evolutionary change. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67303-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie, Y., and J. N. Reeve. 2004. Transcription by Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus RNA polymerase in vitro releases archaeal transcription factor B but not TATA-box binding protein from the template DNA. J. Bacteriol. 1866306-6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie, Y., and J. N. Reeve. 2005. Regulation of tryptophan operon expression in the archaeon Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus. J. Bacteriol. 1876419-6429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanofsky, C. 2003. Using studies of tryptophan metabolism to answer basic biology questions. J. Biol. Chem. 27810859-10878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokoyama, K., S. A. Ishijima, L. Clowney, H. Koike, H. Aramaki, C. Tanaka, K. Makino, and M. Suzuki. 2006. Feast/famine regulatory proteins (FFRPs): Escherichia coli Lrp, AsnC and related archaeal transcription factors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 3089-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]