Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous environmental bacterium whose major catalase (KatA) is highly stable, extracellularly present, and required for full virulence as well as for peroxide resistance in planktonic and biofilm states. Here, we dismantled the function of P. aeruginosa KatA (KatAPa) by comparing its properties with those of two evolutionarily related (clade 3 monofunctional) catalases from Bacillus subtilis (KatABs) and Streptomyces coelicolor (CatASc). We switched the coding region for KatAPa with those for KatABs and CatASc, expressed the catalases under the potential katA-regulatory elements in a P. aeruginosa PA14 katA mutant, and verified their comparable protein levels by Western blot analysis. The activities of KatABs and CatASc, however, were less than 40% of the KatAPa activity, suggestive of the difference in intrinsic catalatic activity or efficiency for posttranslational activity modulation in P. aeruginosa. Furthermore, KatABs and CatASc were relatively susceptible to proteinase K, whereas KatAPa was highly stable upon proteinase K treatment. As well, KatABs and CatASc were undetectable in the extracellular milieu. Nevertheless, katABs and catASc fully rescued the peroxide sensitivity and osmosensitivity of the katA mutant, respectively. Both catalase genes rescued the attenuated virulence of the katA mutant in mouse acute infection and Drosophila melanogaster models. However, the peroxide susceptibility of the katA mutant in a biofilm growth state was rescued by neither katABs nor catASc. Based on these results, we propose that the P. aeruginosa KatA is highly stable compared to the two major catalases from gram-positive bacteria and that its unique properties involving metastability and extracellular presence may contribute to the peroxide resistance of P. aeruginosa biofilm and presumably to chronic infections.

Virtually all aerobic and facultatively aerobic organisms come into contact with reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical, which can be produced by aerobic respiration and extracellular/environmental interaction. To cope with the destructive nature of ROS, such organisms have evolved an arsenal of antioxidant enzymes against the harmful effects of ROS. Among antioxidant enzymes, catalases are one of the central components of the detoxification pathways that prevent the formation of highly reactive hydroxyl radical by catalyzing the decomposition of H2O2 into water and dioxygen by two-electron transfer. Most of the catalases characterized so far can be classified into one of three types based on enzymological properties (18): heme-containing monofunctional catalases, heme-containing bifunctional catalase-peroxidases, and non-heme-containing pseudocatalases (1, 23, 33). Multiple catalases have been found in almost all bacterial species, including Escherichia coli (9, 10), Bacillus subtilis (27), and Streptomyces coelicolor (7, 19). The role of each enzyme in different stages of growth has not been comprehensively understood, whereas a distinct physiological role for each isotype has been reported for Streptomyces coelicolor (6).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic human pathogen causing fatal infections primarily in immunocompromised individuals such as hospitalized patients and those suffering from severe burns or other traumatic skin damage or from cystic fibrosis. P. aeruginosa also can form biofilms on a number of surfaces, including the tissues of the cystic fibrosis lung and on abiotic surfaces such as contact lenses and catheter lines (13, 31). Since the biofilm of P. aeruginosa is highly resistant to various antibiotics and other stressful conditions, it is relatively hard to eliminate this pathogen in its persistent infection status. Furthermore, peroxides are implicated in a variety of stressful environments, including mammalian phagosomal vacuoles that generate millimolar concentrations of H2O2 and related ROS, as antimicrobial substances (14) and thus more attention needs to be paid in order to decipher the role of multiple catalases in P. aeruginosa mechanisms.

P. aeruginosa has three differentially evolved monofunctional catalase genes, katA, katB, and katE (katC), and some strains of P. aeruginosa have the additional catalase gene katM, which encodes a pseudocatalase similar to the manganese-containing nonheme pseudocatalases (20). KatA is the major catalase which is highly expressed in all phases of growth but increased upon stationary growth phase. KatB is detectable only when the cells are exposed to peroxide or paraquat (5) and is involved partially in peroxide resistance (26). Recently, it was reported that KatE was induced by high temperature and requires the disulfide bond formation system for its activity, revealing a new role for this catalase (29). We reported the role of KatA in peroxide resistance and osmoprotection, which is also critical for the adaptive response to H2O2 and full virulence in mouse and Drosophila melanogaster (26). Interestingly, KatA is detectable in stationary-phase culture supernatant (15), which restored the osmosensitivity of the katA mutant (26) as well as the serial dilution defect of the oxyR mutant (15). Although much has been uncovered about the physiological roles of KatA as the major H2O2-scavenging enzyme in peroxide resistance and virulence, little has been known about whether or not the unusual properties of KatA, such as extracellular presence and osmoprotective function, are associated with its known physiological roles.

As an initial step to elucidate the precise roles that the unusual properties of KatA have, in this present study, we introduced heterologous catalase genes into the katA mutant of P. aeruginosa PA14. Included are two phylogenetically related clade 3 monofunctional catalase genes from gram-positive bacteria, S. coelicolor catA (encoding CatASc) and B. subtilis katA (encoding KatABs) (20), the products of which are apparently present exclusively in cytoplasm and not associated with osmoprotection either. We found that the extracellular presence is unique to P. aeruginosa KatA and thus is likely involved in peroxide resistance in the biofilm state of P. aeruginosa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Escherichia coli DH5α, BL21(DE3), and S17-1 and the katA deletion mutant of P. aeruginosa strain PA14 (26) and its derivatives were grown at 37°C using LB broth or on 2% Bacto agar (Difco)-LB or Cetrimide agar (Fluka) plates as previously described (17). Stationary-phase cultures were inoculated into fresh LB broth with an inoculum of 1.6 × 107 CFU/ml and then grown and used for experiments. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: for P. aeruginosa, rifampin (100 μg/ml), tetracycline (100 μg/ml), and carbenicillin (200 μg/ml); and for E. coli, chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), tetracycline (25 μg/ml), and ampicillin (50 μg/ml).

Expression of catalase genes in P. aeruginosa.

For catalase expression in the P. aeruginosa katA mutant, pUCP-body was created by inverse PCR using katA-N-up (5′-CTT CTC TTC CAT ATG CTC TCT CC-3′; underlining denotes the NdeI site) and katA-C-down (5′-ACT GAT GGA TCC TGA TGA GGC CC-3′; underlining denotes the BamHI site) primers and the pUCP18 plasmid containing the full-length katA fragment as the template (26). pUCP-body contains the potential upstream and downstream katA regulatory elements as well as the two engineered enzyme sites (NdeI and BamHI) to facilitate the cloning of the amplified coding regions (Fig. 1). Catalase genes from P. aeruginosa (katAPa), B. subtilis (katABs), and S. coelicolor (catASc) were amplified using the following primer pairs: for katAPa, katA-N0 (5′-AGA GAG CAT ATG GAA GAG AAG ACC-3′, with the NdeI site underlined) and katA-C0 (5′-AGG ATC CAT CAG TCC AGC TTC AG-3′, with the BamHI site underlined and the stop codon italicized); for katABs, BsuKatA-N0 (5′-GAT CAT ATG AGT TCA AAT AAA CTG-3′, with the NdeI site underlined) and BsuKatA-C0 (5′-TTT TGC AGA TCT CCA TTA AGA ATC-3′, with the BglII site underlined and the stop codon italicized); and for katASc, ScoCatA-N0 (5′-GCA ACA TAT GCC TGA GA ACA ACC-3′, with the NdeI site underlined) and ScoCatA-C0 (5′-CGG ATC CGG ATC AGA GGT TGC CG-3′, with the BamHI site underlined and the stop codon italicized). The PCR products of about 1.5 kb were cloned into pUCP-body using NdeI and BamHI (for katAPa and catASc) or NdeI and BglII (for katABs). The resultant plasmids containing each catalase-coding region were introduced into the katA mutant cells by electroporation (8).

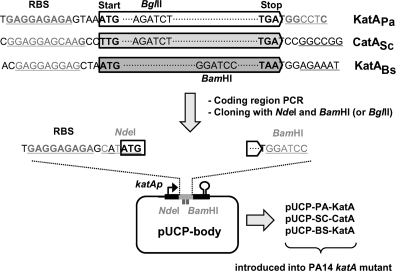

FIG. 1.

Experimental strategy for heterologous expression of clade 3 monofunctional catalases from gram-positive bacteria. Catalase coding regions from Bacillus subtilis (encoding KatABs) and Streptomyces coelicolor (encoding CatASc) as well as P. aeruginosa (KatAPa) were amplified and cloned in pUCP-body, a pUCP18 derivate that contains the potential katA regulatory elements including the katA promoter (bent arrow), the potential 5′-untranslated region (UTR) with the ribosome binding sequence (RBS), and the potential 3′-UTR with the intrinsic transcription termination signal (open circle). Then, each construct was introduced into the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 katA mutant. Mutated nucleotides for enzyme site engineering are indicated in pUCP-body. Underlined hexanucleotides of the coding regions indicate the target sites for enzyme site engineering. BglII and BamHI sites in the coding regions are also indicated.

Antibody preparation and Western blot analysis.

Anti-CatASc antibody was prepared as described previously (7). To generate the antibodies against KatAPa, KatABs, or RpoA, pET15b was used for recombinant protein overexpression. For RpoA, the 1,072-bp fragment encompassing the P. aeruginosa rpoA coding region was amplified using rpoA-N0 (5′-GGT GCA CAT ATG CAG AGT TCG G-3′, with the NdeI site underlined) and rpoA-C1 (5′-ACT TTT ACG ATG GCG CAT GG-3′) and then cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega). The respective coding regions were cloned into pET15b using NdeI and BamHI, and these constructs were introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS). E. coli cells were grown at 37°C for 2 to 3 h with agitation to the early log phase and induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Recombinant His-tagged RpoA, KatAPa, and KatABs proteins were recovered from the inclusion bodies and then gel purified from a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel. An emulsion of 100 μg RpoA or catalase proteins in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.0) was injected peritoneally into five mice (ICR females) at an interval of 2 weeks. After 5 weeks, antisera were prepared from the sacrificed mice. For Western blot analysis, a 10% SDS gel was applied for electrotransfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham) by use of the Trans-Blot system (Bio-Rad) at 160 mA for 1 h. The membrane were washed three times, blocked in Tris-buffered saline-Triton-X 100 (TBS-T; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100) containing either 0.5% bovine serum albumin or 2% skim milk, and incubated for 1 h with anticatalase antibodies (10−4 dilution). Excess antibodies were removed by repeated washing with TBS-T. After 15 min of incubation in TBS-T containing the secondary antibody (10−4 dilution of goat immunoglobulin G against mouse immunoglobulins; Santa Cruz) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, membranes were washed twice with TBS-T. The immunodetection was performed using the ECL detection system according to the manufacturer's instruction (Amersham).

Enzyme activity assay and staining.

Harvested cells were suspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate (KP) buffer (pH 6.8) and then disrupted by sonication (Sonics and Materials, Inc.). The suspension was clarified by centrifugation at 4°C. The amount of total protein in cell extracts was quantified using a protein assay (Bio-Rad). The total catalase activity levels in cell extracts were measured spectrophotometrically as described by Beers and Sizer (3) with 20 μg of total protein. The catalase activity unit is defined as the enzyme activity that decomposes 1 μmol of H2O2 per min at room temperature. For catalase activity staining, aliquots of cell extracts containing 20 to 200 μg of proteins were electrophoresed on a 7% native polyacrylamide gel and stained for catalase activity as described elsewhere (11, 32). Superoxide dismutase activity staining was performed according to the method of Beauchamp and Fridovich (2). Briefly, the cell extracts (20 μg) were electrophoresed on a 12% native polyacrylamide gel, after which the gel was incubated in a solution containing 2.5 mM nitroblue tetrazolium for 25 min and then in 50 mM KP buffer (pH 7.8) containing 28 μM riboflavin and 28 mM tetramethyl ethylene diamine for 20 min in the dark. The gel was placed in distilled water and exposed on a light box for 15 min until the dark blue background color appeared.

Stress treatments.

A spotting assay was performed for stress treatments as described elsewhere (26). Briefly, cells were grown in LB broth at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 (logarithmic growth phase) or to an OD600 of 3.0 (stationary growth phase). Serial dilutions were performed in LB to adjust the CFU of the cell spots (3 μl), which were spotted onto an LB agar medium containing either 200 μM H2O2 or 0.9 M potassium chloride (KCl). For H2O2 treatment in the biofilm state, polystyrene tubes containing LB medium were inoculated with overnight-grown cells and then incubated at 37°C without agitation. After a certain period of time, the cultures were treated with H2O2 for 30 min at different final concentrations (20 mM at 12 h, 30 mM at 24 h, and 40 mM at 48 h). The surviving cells were subjected to viable count determination at appropriate dilutions to give 100 to 500 CFU per plate. The survival rates were calculated as the percentages relative to the survival for the corresponding water treatment control.

Virulence measurement.

For murine peritonitis infection, 4-week-old mice (ICR females) were injected by syringe containing bacterial suspensions from the stationary growth-phase cultures (OD600 = 3.0) diluted in PBS containing 1% mucin. The amount of bacterial cells infected was approximately 2 × 106 CFU per mouse. Mouse mortality was monitored for 54 h postinfection. Mortality experiments were repeated at least three times. Similar results were obtained each time, and the percentage of mortality was calculated from a total of three independent experiments. For fly mortality, the wild-type 3- to 6-day-old adult flies (Drosophila melanogaster Oregon R) were infected by pricking at the dorsal thorax with a 10-μm needle (Ernest F. Fullam, Inc.) dipped halfway into bacterial suspensions diluted in 10 mM MgSO4 and containing approximately 3× 107 CFU from the stationary growth phase (OD600 = 3.0). Our infection conditions enabled us to introduce 10 to 100 P. aeruginosa cells per fly (25). Fly mortality was monitored for 54 h postinfection. Mortality experiments were repeated at least five times. Similar results were obtained each time, and the percentage of mortality was calculated from a total of five independent experiments.

RESULTS

Expression of clade 3 monofunctional catalases of gram-positive bacteria in P. aeruginosa.

In order to understand the relationship between the unusual properties of KatA and its physiological functions in P. aeruginosa, we performed a heterologous expression of catalase gene products from different origins, which are phylogenetically similar but have been thought so far to lack such properties associated with P. aeruginosa KatA. We selected two clade 3 gene products, Streptomyces coelicolor CatA (CatASc, 487 aa) and Bacillus subtilis KatA (KatABs, 483 aa), based on their phylogenetic relatedness as gram-positive bacterial catalases (20). As well, CatASc is actively expressed in E. coli (7) and is suggested to represent horizontal gene transfer based on its anomalous grouping with proteobacterial catalases (22), with 82.8% amino acid similarity and 74.1% nucleotide identity to P. aeruginosa KatA (KatAPa). Furthermore, the CatASc gene displays slightly lower GC content (67.9%) than the high GC content (72.0%) of the S. coelicolor A3(2) genome (4), which fits better with the overall GC content of the P. aeruginosa PA14 genome (66.3%) as well as the KatAPa coding region (62.3%) (24). KatABs was included as another gram-positive catalase which exhibits average similarities (75.9% amino acid similarity and 57.8% nucleotide similarity) to KatAPa in the same clade of monofunctional catalases, with a lower GC content of the corresponding coding region (45.8%).

We amplified each coding region of the catalase genes and cloned into pUCP-body, a pUCP18-derivative, which allows the expression of the cloned coding regions mostly under the potential regulatory regions of the katA gene. The whole procedure is outlined in Fig. 1. The potential katA regulatory regions were verified based on basal expression, H2O2 inducibility, and stationary-phase inducibility, while the basal expression is approximately threefold higher than in its genome copy state (data not shown). The katA gene was also amplified to contain NdeI and BamHI sites in order to rule out the potential effects of site-directed mutagenesis for enzyme site engineering. The downstream primer for KatABs was designed to contain BglII, since it contains a BamHI site within the coding region (Fig. 1).

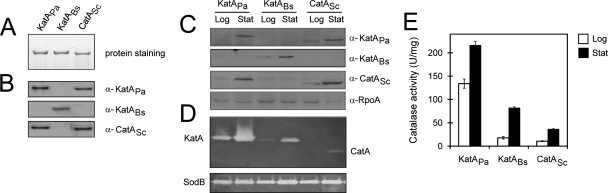

Three catalase-expressing constructs (pUCP-PA-KatA, pUCP-BS-KatA, and pUCP-SC-CatA) were introduced into the PA14 katA mutant, which has no detectable catalase activity during normal growth (reference 5 and data not shown), and the catalase expression was verified by measuring the transcript and protein amounts. The steady-state levels of the transcripts were exactly the same, as assessed by S1 nuclease protection assay (data not shown). As well, the amounts of catalase proteins did not differ, as shown in Fig. 2C. Interestingly, the cross-reactivity was observed for anti-KatAPa antiserum and anti-CatASc antiserum used in this study, whereas anti-KatABs was highly specific to the cognate protein, indicating some structural similarity between the KatAPa and CatASc proteins (Fig. 2B). We had tested for the capabilities of the three antisera to detect the cognate proteins by serially diluting the purified proteins and concluded that the sensitivities for the antisera did not differ in our experimental conditions (Fig. 2A and B and data not shown). These results suggest that the KatABs and CatASc proteins were well expressed in P. aeruginosa, at a level comparable to that seen for KatAPa.

FIG. 2.

Expression and activity of heterologous catalases in P. aeruginosa. (A and B) Antibody preparation and comparison. (A) Approximately 150 ng of purified catalase proteins that were used to generate catalase antibodies were separated and stained. (B) About 10 ng of the same proteins were separated and subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies (α) indicated at the left. (C to E) Measurement of protein amount and enzyme activity of heterologously expressed catalases in P. aeruginosa. Cells were grown at 37°C in LB broth to an OD600 of 0.5 (logarithmic growth phase [Log]) and to an OD600 of 3.0 (stationary growth phase [Stat]). Cell extracts of each strain were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies indicated at the left (α-RpoA for the RNA polymerase α subunit of P. aeruginosa) (C), activity staining for catalase (top) and superoxide dismutase (bottom) as the control (D), and total catalase activity assay (E) as described in Materials and Methods. The error bars in panel E represent the standard deviations from the five independent experiments.

KatABs and CatASc were not fully active in P. aeruginosa.

Because the protein amounts of the three catalases did not differ, we next examined the catalase activity by measuring the total catalase activity and visualizing catalase activity in a native polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 2D and E). The activity of the major catalase, KatA, accounts for almost all of the total catalase activity in P. aeruginosa during normal growth, since KatB and KatE are not expressed during normal growth conditions (5, 29). Thus, the total catalase activity in cell extracts most likely represented the activity of the introduced catalases. The intensity of the newly appeared bands in the catalase activity staining was apparently proportional to the total catalase activity as well. As a result, the KatABs and CatASc activities were 13.3% and 7.9%, respectively, of the KatAPa activity at logarithmic growth phase and 37.9% and 16.9%, respectively, of the KatAPa activity at stationary growth phase (Fig. 2D). The CatASc activity was lower than that of KatABs, even with the closer protein and nucleotide similarities to KatAPa as well as the closer similarities seen for the corresponding genes in GC content and codon composition (data not shown). Since KatAPa requires BrfA, a ferritin-like bacterial protein, for its optimal activity and subsequent peroxide resistance (28), we assumed potential posttranslational regulations, for example, exerted at the level of cofactor (heme and/or iron) acquisition, which might be inefficiently working toward KatABs and CatASc proteins expressed in P. aeruginosa. However, we cannot completely rule out the possibility of a difference in the intrinsic specific activities among the clade 3 catalases.

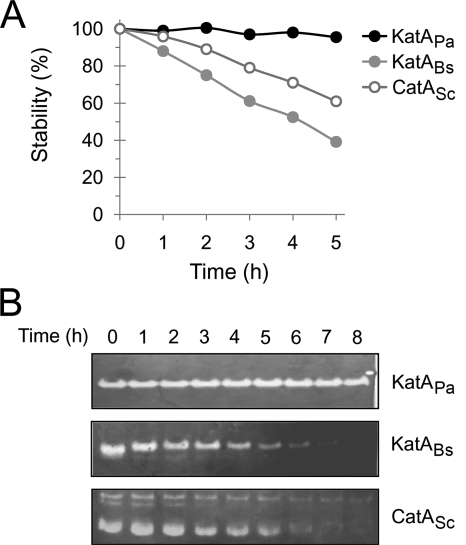

KatABs and CatASc were unstable in the presence of proteolytic activity.

Although the protein levels for KatABs and CatASc were comparable to that for KatAPa during growth, we wondered about the protein stability for the three catalases after the cessation of growth, which might be more relevant to growth characteristics in natural habitats. Since KatAPa is unusually stable, with extreme resistance to chemicals and proteases, including proteinase K and neutrophil protease cathepsin G (15), the stability of the other two catalase proteins expressed in P. aeruginosa needed to be examined in the P. aeruginosa cell extracts. We observed no detectable catalase activity for both KatABs and CatASc extracts after incubation at 37°C for 24 h, whereas no activity decrease for KatAPa extract was observed (data not shown). Furthermore, we measured catalase stability in the presence of protease K over a certain period of time up to 8 h. As shown in Fig. 3, the total catalase activity for both KatABs and CatASc was gradually decreased and the activity bands were undetectable after 7 h for KatABs, even at the higher starting amount (40 μg). In contrast, KatAPa was highly stable even in the presence of proteinase K treatment, and no activity decrease was observed even after the 48-h incubation in the presence of proteinase K (data not shown). KatABs was slightly but significantly less stable than CatASc, although the catalase activity during growth was higher in the KatABs-expressing cells than in the CatASc-expressing cells. These results and the observation that the purified CatASc protein from S. coelicolor was as sensitive to protease K as CatASc from P. aeruginosa (data not shown) verified that the metastability of KatAPa in P. aeruginosa involved an intrinsic property unique to KatAPa and is not a property for a clade 3 monofunctional catalase expressed in P. aeruginosa cells.

FIG. 3.

Stability of heterologous catalases upon protease treatment. Extracts from stationary growth-phase cells were mixed with proteinase K (1 mg/ml) and incubated at 25°C. At the designated time points, samples were removed and subjected to total catalase activity assay (A) and catalase activity staining (B). Catalase stability in panel A represents the percentage of the remaining activity relative to the corresponding time zero activity as 100% for each sample. The results are the average from three independent experiments. For catalase staining, the following amounts of cell extracts were used: for KatAPa, 20 μg; for KatABs, 40 μg; and for CatASc, 60 μg.

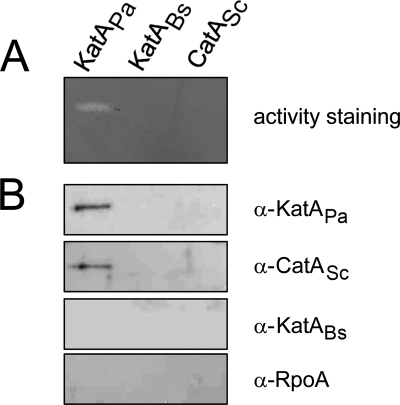

KatABs and CatASc were undetectable in the extracellular milieu.

Based on the report that the KatA activity is present in spent culture supernatants of P. aeruginosa cells and rescues the serial dilution defect of the oxyR mutant (15), we hypothesized that this extracellular presence should be unique to KatAPa and presumably associated with the life cycles of P. aeruginosa, which involves cell lysis in both planktonic and biofilm modes of growth. Thus, the extracellular presence of the heterologously expressed catalases was investigated by catalase activity staining (Fig. 4A), because it is more sensitive than Western blot analysis and does not require protein concentration steps. Whereas KatAPa activity was present in the spent culture supernatant after 36 h of incubation at 37°C, no catalase activity was detected for either KatABs or CatASc. To obviate the possibility of an inability to detect lower catalase activity for KatABs and CatASc, Western blotting using concentrated culture supernatants was performed. The concentration of supernatant proteins for each sample was verified by total protein staining (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 4B, we were unable to detect any band from KatABs or CatASc. Failure to detect RpoA proteins substantiates the metastability and/or extracellular presence of KatAPa, which is most likely unique to this particular catalase protein in P. aeruginosa.

FIG. 4.

Extracellular presence of heterologous catalases. (A) Culture suspensions (30 ml) were centrifuged for 10 min at 8,000 rpm. The remaining supernatants were filtrated by syringe filter (0.22-μm pore size) and electrophoresed on 8% native polyacrylamide for catalase activity staining. (B) For Western blotting, supernatant samples were precipitated by the addition of cold 13% trichloroacetic acid at 4°C. Dissolved pellets were electrophoresed on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and subjected to Western blotting using antibodies as for Fig. 2C (designated at the right).

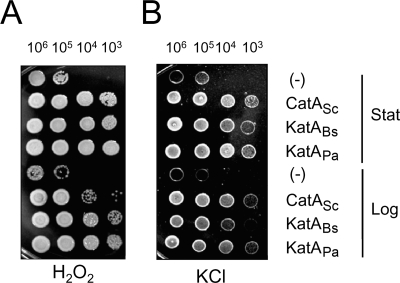

KatABs and CatASc fully rescued the sensitivities of the katA mutant to peroxide and osmotic stresses, respectively.

The expression characteristics of KatABs and CatASc in P. aeruginosa cells tell us about two unique properties implicated in KatAPa: unusual protein stability and high catalatic activity compared to what was seen for the two gram-positive catalases expressed in P. aeruginosa. To test whether these properties of KatAPa are associated with its physiological functions, we investigated the in vitro and in vivo phenotypes of P. aeruginosa katA mutant cells expressing the heterologous catalases. First, we examined the stress resistance phenotypes as described in Materials and Methods. We spotted cells taken at two different growth phases for comparison (Fig. 5). Interestingly, cells from stationary growth phase were generally resistant to both H2O2 and KCl compared to the cells from logarithmic growth phase. There was no clear difference in susceptibilities for the three catalase-expressing bacteria at the stationary growth phase. Nevertheless, the expression of any catalase is critical for full peroxide resistance as well as full osmoprotection. In contrast to the stationary-phase cells, log-phase cells displayed marked difference between cells expressing different catalases: KatABs fully complements the peroxide sensitivity of the katA mutant, whereas CatASc fully complements the osmosensitivity of the katA mutant. KatABs partially complements the osmosensitivity, while CatASc partially complements the peroxide sensitivity. We are as of yet unsure that the catalase activity (KatABs > CatASc) and protein stability (KatABs < CatASc) are related to peroxide resistance and osmotic resistance, respectively, for KatAPa functions in P. aeruginosa. It needs to be further verified that there might exist differential molecular mechanisms that dissect peroxide resistance and osmotic resistance, in which KatAPa is involved with differential characteristics.

FIG. 5.

Rescue of katA mutant stress resistance phenotypes by heterologous catalases. Cells were grown in LB broth to an OD600 of 0.5 (logarithmic growth phase [Log]) or to an OD600 of 3.0 (stationary growth phase [Stat]). Tenfold serial dilutions of the catalase-expressing cells and the control cells containing pUCP-body in fresh LB broth were spotted onto an LB agar plate containing either 200 μM H2O2 (A) or 0.9 M KCl (B). The numbers indicate the CFUs from the cell spots.

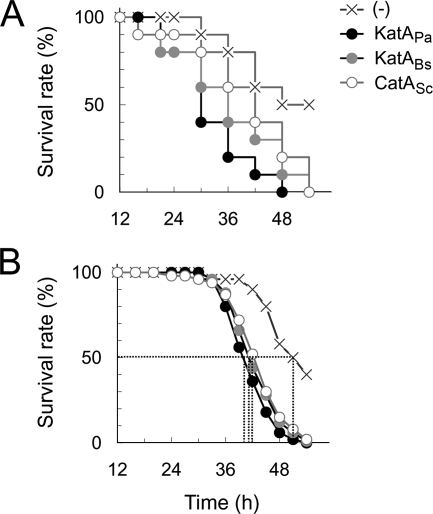

KatABs and CatASc rescued the virulence attenuation of the katA mutant in acute infection models.

Next, we measured the virulence characteristics of the catalase-expressing bacteria, since the katA mutant of P. aeruginosa PA14 is attenuated in virulence in mouse peritonitis and Drosophila melanogaster infection models (26). As might be expected from the in vitro complementation phenotypes, both KatABs and CatASc appeared to rescue the virulence defect of the katA mutant (Fig. 6). It was evident that there was a gradual degree of the virulence rescue in mouse infections (KatAPa > KatABs > CatASc) (Fig. 6A), whereas there was no statistically significant difference in D. melanogaster infection (Fig. 6B). As a result, KatABs and CatASc were able to rescue the virulence attenuation of the katA mutant, at least in these acute infection models. These results suggest that the unusual properties of KatAPa, such as metastability, higher specific activity, and extracellular presence, may be dispensable for stress resistance as well as virulence in acute infections with P. aeruginosa.

FIG. 6.

Rescue of katA mutant virulence phenotypes by heterologous catalases. Virulence was scored for mouse peritonitis (A) and Drosophila melanogaster (B) infections using LB broth-grown cells (OD600 of 3.0). For peritonitis-derived mouse infection, bacteria were diluted to reach 2 × 106 CFU in PBS containing 1% mucin. Ten anesthetized ICR mice were infected intraperitoneally with the bacterial suspensions. Percentages of survivors over the indicated time points are shown. The results are the averages of the three independent experiments. For fly mortality determination, 30 flies were infected with 50 to 200 CFU of bacteria. The infected flies were incubated at 25°C, and dead flies were counted up to 54 h. Dotted lines in panel B indicate the time required to reach 50% mortality. (-), pUCP-body control.

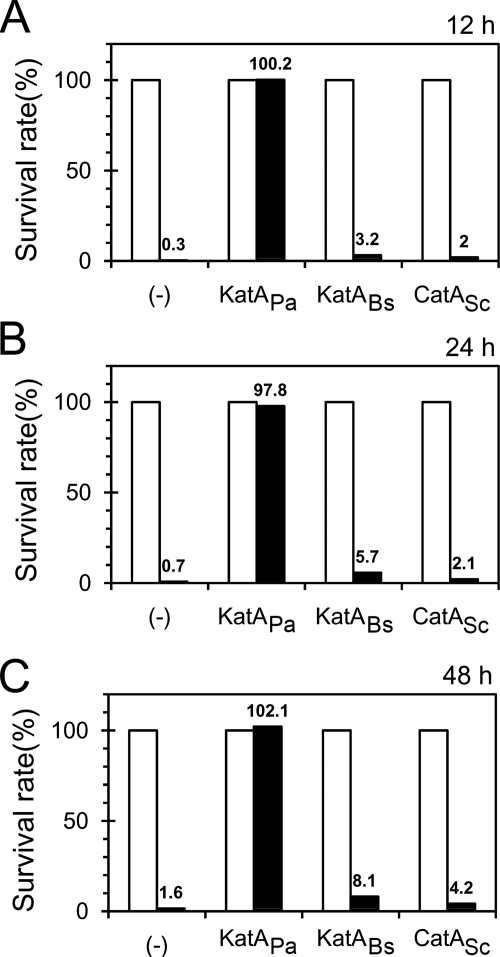

KatABs and CatASc were unable to rescue the peroxide sensitivity of the katA mutant in the biofilm state.

The most drastic difference between KatAPa and the other two catalases may be in extracellular presence, which may be associated with one or two of its unusual properties, posttranslational activity modulation and metastability. Based on this and on the fact that KatA is known to be critical for the H2O2 resistance of P. aeruginosa biofilm via its effect on the concentration of the H2O2 that penetrates into the biofilm matrix (12, 30), we investigated whether the H2O2 sensitivity of the P. aeruginosa katA mutant cells in static biofilm was rescued or not by introducing KatABs and CatASc. We tried with three different biofilm stages of P. aeruginosa cells during static biofilm cultures at 37°C, which were subjected to H2O2 treatment for 1 h, with the surviving cells enumerated by determination of viable count. As shown in Fig. 7, at all stages that we investigated (12 h, 24 h, and 48 h), CatASc could not complement the biofilm susceptibility of the katA mutant to H2O2 at all, whereas KatABs could complement it very little (less than 5%), which is in a clear contrast to KatAPa. This result and the observation that the KatAPa exhibits unusual or unique properties ascribed to its metastability, high specific activity, and/or extracellular presence compared to the other two catalases may lead to the conclusion that at least one of those properties of KatAPa is implicated in its resistance to oxidative stresses in the biofilm state of P. aeruginosa.

FIG. 7.

Failure to rescue the peroxide resistance of katA mutant biofilm. For biofilm H2O2 resistance, bacteria were 1% subcultured from overnight cells in a 5-ml polystyrene test tube and incubated at 37°C without agitation. After the designated time points (12 h [A], 24 h [B], 48 h [C]), cells were treated with either H2O2 (filled bars) or water (empty bars) for 30 min as described in Materials and Methods. The treated bacteria were subjected to viable count determination at appropriate dilutions. The survival rate is the percentage of the CFU relative to the CFU from the corresponding water-treated control as 100%. The results are the averages from five independent experiments, and the numbers for the filled bars indicate the average survival rates.

DISCUSSION

The strictly nonfermentative nature of P. aeruginosa physiology can lead to the intracellular generation of oxidative or nitrosative stresses during its respiration on molecular oxygen and nitrate. As a pathogenic microorganism, it encounters a great deal of oxidative stress during the infection process as well. To combat the accumulation of ROS generated during aerobic respiration or the infection process, P. aeruginosa should employ versatile antioxidant defense enzymes, among which the major catalase, KatA, is critical for full virulence as well as peroxide resistance and osmoprotection (26). KatB has an auxiliary function to assist the KatA function in response to oxidative stress conditions (5, 26), whereas KatE might have a role in heat shock conditions, based on its inducibility upon heat shock (29). The physiological roles that the catalase proteins play in various bacterial microorganisms are usually associated with adaptive functions such as stress responses, differentiation, and virulence. Whereas the primary physiological roles of KatB and KatE have not been clearly delineated, KatA appears to have most of the known catalase-associated functions in P. aeruginosa: oxidative stress response, osmotic stress response, and virulence (26). In these respects, P. aeruginosa KatA warrants further characterization of its enzymatic properties among the known bacterial monofunctional catalases in that it fortuitously gains all the physiological functions that should have otherwise been assigned to more than two catalases. Moreover, P. aeruginosa KatA displays several specialized characteristics that are missing in other similar catalases: extracellular and periplasmic presence (15); requirement of an auxiliary protein, BrfA, for full activity (28); and extreme resistance to proteases and SDS (15). In this study, we hoped to dismantle the physiological functions of KatA, each of which could be ascribed to each of those unique properties of KatA.

For this purpose, we substituted the coding region of KatA (katAPa) with those of the other catalases with no such properties. We selected the major catalases from two gram-positive bacteria, S. coelicolor (CatASc) and B. subtilis (KatABs) based on the phylogenetic relatedness (20) as well as on the structures of the corresponding genes such as codon usage and GC content. CatASc has been known to diverge from the expected 16S rRNA phylogeny with exceptional protein sequence similarity to proteobacterial catalases (20, 22). By using the antibodies against each catalase protein, we verified their proper expression at the levels of transcription and translation in P. aeruginosa cells (data not shown). However, the activity was markedly less than that of KatAPa, indicating the intrinsic efficiency of catalatic functions and/or the presence of posttranslational modulation for catalase activity, which is specific to KatAPa in P. aeruginosa cells. Since there have been no extensive studies on the different enzymatic activities of clade 3 monofunctional catalases and KatAPa has been known to require a ferritin-like protein (BrfA) for full activity, we postulated that BrfA might be active only toward KatAPa. Alternatively, there might exist other posttranslational mechanisms efficiently discriminating in favor of KatAPa over other catalases even with phylogenic (i.e., overall) similarity. We are currently measuring the specific activity of the three catalases purified from the native hosts as well as investigating the involvement of BrfA on the enzymatic activity of the three catalases in vitro as well as in vivo. Furthermore, we are examining whether or not the higher enzymatic activity of KatAPa is related to the extracellular presence of KatAPa, although the metastability characteristics of KatAPa might preponderantly account for the extracellular presence upon cell lysis during the stationary growth phase and presumably from biofilm-induced cell death.

Based on the present study, we could dismantle the functions for full activity and protein stability only. The activity of KatABs is higher than that of CatASc, whereas the protein stability of CatASc is slightly but significantly higher than that of KatABs upon protease treatment. We carefully suggest that some modular similarities rather than the overall similarity may account for the protein domains of KatAPa involved in posttranslational modification for full activity (domains more similar to KatABs) and in protein stability (domains more similar to CatASc). This interpretation could be extrapolated to the explanation of the stress phenotypes in the presence of H2O2 and KCl. KatABs fully rescues the H2O2 sensitivity of the katA mutant, indicating that catalase activity or its related phenotypes, such as cofactor (i.e., iron) availability rather than protein stability, are important in H2O2 stress conditions. Considering the activity of catalase to efficiently decompose H2O2 and the availability of free iron, which is reactive with H2O2, the higher specific activity involving posttranslational activity maturation of KatAPa is very likely critical for H2O2 resistance. Since the activity, not the protein amount, of KatABs is less than 40% of the KatAPa activity during normal growth, we explained the full complementation of the katA mutant by KatABs in two ways: first, a certain level of catalase activity is required for full resistance, at least under our experimental conditions, and the activity level of KatABs is sufficient for full resistance; second, the specific activity KatABs might be changed under stress treatment conditions, since we were unable to quantitatively measure catalase activity in those particular conditions. More-elaborate and -quantitative approaches need to be used to elucidate the precise mechanism of KatAPa in full peroxide resistance in vitro, which is shared by KatABs but not by CatASc. We have been generating a series of the hybrid catalase chimera of KatAPa and CatASc to uncover the modular structures for activity modulation and have found so far that the C-terminal part of KatAPa is critical for the activity modulation of KatAPa (data not shown). Likewise, we assumed that some common properties of KatAPa shared by CatASc but not by KatABs might be important for osmoprotection, one of which is protein stability, since KatAPa and CatASc are more stable than KatABs upon protease treatment. Based on the fact that KatAPa is even more stable than CatASc in the presence of protease, the possible existence of other shared properties awaits further investigation.

Stationary-phase cells are relatively resistant to stressful conditions in general, through a mechanism called “general stress response” (16). It is noteworthy that cell spots from stationary growth phase could form colonies better even upon stress treatments. Furthermore, the inability for complete rescue of peroxide sensitivity by CatASc and for osmosensitivity by KatABs was not observed for the cells from stationary growth phase. Because bacteria are considered generally to be at the growth-arrested state in natural habitats, including host tissues, cells might be at a similar growth state during the infection process. Therefore, the restoration of stress resistance for stationary-phase cells by KatABs and CatASc may be in agreement with their complementation of the virulence phenotypes of the katA mutant in acute infections.

In summary, all of the phenotypes of katA mutants except for biofilm susceptibility to H2O2 were partially or completely rescued by introducing either KatABs or CatASc, neither of which were detectable extracellularly. Therefore, the roles that KatAPa plays in stress resistance during normal growth and virulence in acute infections probably have nothing to do with the extracellular nature of KatAPa, although extracellular presence is a feature unique to KatAPa. This feature, however, is most likely critical for peroxide resistance of biofilm cultures and presumably chronic infections. The extracellular presence of KatAPa may be associated most likely with its metastability and also possibly with its posttranslational activity modulation. Furthermore, the extracellular presence of KatAPa might result from inevitable cell lysis during the stationary growth phase or biofilm maturation. Even though KatAPa appears to lack any predicted signal sequence (data not shown) and was known to be passively released upon cell lysis (15), we do not completely rule out the possibility of the active secretion of KatAPa, based on the observation that KatAPa is also present in the periplasm (5), which might act as the actual barrier in gram-negative bacteria, and the known examples of secreted catalases, such as a minor catalase from S. coelicolor (6) and a periplasmic catalase from P. syringae (21), as well. All these speculations will be more directly addressed by further studies, especially in terms of the primary and tertiary structures of KatAPa in comparison with those of other clade 3 monofunctional catalases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the 21C Frontier Microbial Genomics and Applications Center (MG05-0104-05-0) and the Korea Research Foundation (2006-311-C00145) to Y.-H.C. Y.-S.C. and D.-H.S. were supported by the BK21 program from the Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allgood, G. S., and J. J. Perry. 1986. Characterization of a manganese-containing catalase from the obligate thermophile Thermophilum album. J. Bacteriol. 168563-567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beauchamp, C., and I. Fridovich. 1971. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 44276-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beers, R. F., Jr., and I. W. Sizer. 1952. A spectrophotometric method for measuring breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195276-287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley, S. D., K. F. Chater, A.-M. Cerdeño-Tárraga, G. L. Challis, N. R. Thomson, K. D. James, D. E. Harris, M. A. Quail, H. Kieser, D. Harper, A. Bateman, S. Brown, G. Chandra, C. W. Chen, M. Collins, A. Cronin, A. Fraser, A. Goble, J. Hidalgo, T. Hornsby, S. Howarth, C.-H. Huang, T. Kieser, L. Larke, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, S. O'Neil, E. Rabbinowitsch, M.-A. Rajandream, K. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, D. Saunders, S. Sharp, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Taylor, T. Warren, A. Wietzorrek, J. Woodward, B. G. Barrell, J. Parkhill, and D. A. Hopwood. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, S. M., M. L. Howell, M. L. Vasil, A. J. Anderson, and D. J. Hassett. 1995. Cloning and characterization of the katB gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encoding a hydrogen peroxide-inducible catalase: purification of KatB, cellular localization, and demonstration that it is essential for optimal resistance to hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 1776536-6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho, Y.-H., E.-J. Lee, and J.-H. Roe. 2000. A developmentally regulated catalase required for proper differentiation and osmoprotection of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 35150-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho, Y.-H., and J.-H. Roe. 1997. Isolation and expression of the catA gene encoding the major vegetative catalase in Streptomyces coelicolor Müller. J. Bacteriol. 1794049-4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi, K. H., A. Kumar, and H. P. Schweizer. 2006. A 10-min method for preparation of highly electrocompetent Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells: application for DNA fragment transfer between chromosomes and plasmid transformation. J. Microbiol. Methods 64391-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claiborne, A., and I. Fridovich. 1979. Purification of the o-dianisidine peroxidase from Escherichia coli B. J. Biol. Chem. 2544245-4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claiborne, A., D. P. Malinowski, and I. Fridovich. 1979. Purification and characterization of hydroperoxidase II of Escherichia coli B. J. Biol. Chem. 25411664-11668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clare, D. A., M. N. Duong, D. Darr, F. Archibald, and I. Fridovich. 1984. Effects of molecular oxygen on detection of superoxide radical with nitroblue tetrazolium and on activity stains for catalase. Anal. Biochem. 140532-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elkins, J. G., D. J. Hassett, P. S. Stewart, H. P. Schweizer, and T. R. McDermott. 1999. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm resistance to hydrogen peroxide: protective role of catalase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 654594-4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gavin, J., N. F. Button, I. A. Watson-Craik, and N. A. Logan. 2000. Observation of soft contact lens disinfection with fluorescent metabolic stains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66874-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassett, D. J., and M. S. Cohen. 1989. Bacterial adaptation to oxidative stress: implications for pathogenesis and interaction with phagocytic cells. FASEB J. 32574-2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassett, D. J., E. Alsabbagh, K. Parvatiyar, M. L. Howell, R. W. Wilmott, and U. A. Ochsner. 2000. A protease-resistant catalase, KatA, released upon cell lysis during stationary phase is essential for aerobic survival of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa oxyR mutant at low cell densities. J. Bacteriol. 1824557-4563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hengge-Aronis, R. 1999. Interplay of global regulators and cell physiology in the general stress response of Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2148-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heo, Y.-J., I.-Y. Chung, B.-K. Choi, G. W. Lau, and Y.-H. Cho. 2007. Genome sequence comparison and superinfection between two related Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages, D3112 and MP22. Microbiology 1532558-2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones, P., and I. Wilson. 1978. Catalases and iron complexes with catalase-like properties, vol. 7. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY.

- 19.Kim, H.-P., J.-S. Lee, Y.-C. Hah, and J.-H. Roe. 1994. Characterization of the major catalase from Streptomyces coelicolor ATCC 10147. Microbiology 1403391-3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klotz, M. G., and P. C. Loewen. 2003. The molecular evolution of catalatic hydroperoxidases: evidence for multiple lateral transfer of genes between Prokaryota and from Bacteria into Eukaryota. Mol. Biol. Evol. 201098-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klotz, M. G., and S. W. Hutcheson. 1992. Multiple periplasmic catalases in phytopathogenic strains of Pseudomonas syringae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 582468-2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klotz, M. G., G. R. Klassen, and P. C. Loewen. 1997. Phylogenetic relationships among prokaryotic and eukaryotic catalases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14951-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kono, Y., and I. Fridovich. 1983. Isolation and characterization of the pseudocatalase of Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Biol. Chem. 2586015-6019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, D. G., J. M. Urbach, G. Wu, N. T. Liberati, R. L. Feinbaum, S. Miyata, L. T. Diggins, J. He, M. Saucier, E. Deziel, L. Friedman, L. Li, G. Grills, K. Montgomery, R. Kucherlapati, L. G. Rahme, and F. M. Ausubel. 2006. Genomic analysis reveals that Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence is combinatorial. Genome Biol. 7R90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, J.-S., S.-H. Kim, and Y.-H. Cho. 2004. Dithiothreitol attenuates the pathogenic interaction between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Drosophila melanogaster. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 14367-372. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, J.-S., Y.-J. Heo, J.-K. Lee, and Y.-H. Cho. 2005. KatA, the major catalase, is critical for osmoprotection and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. Infect. Immun. 734399-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loewen, P. C., and J. Switala. 1987. Multiple catalases in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1693601-3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma, J. F., U. A. Ochsner, M. G. Klotz, V. K. Nanayakkara, M. L. Howell, Z. Johnson, J. E. Posey, M. L. Vasil, J. J. Monaco, and D. J. Hassett. 1999. Bacterioferritin A modulates catalase A (KatA) activity and resistance to hydrogen peroxide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1813730-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mossialos, D., G. R. Travankar, J. E. Zlosnik, and H. D. Williams. 2006. Defects in a quinol oxidase lead to loss of KatC catalase activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: KatC activity is temperature dependent and it requires an intact disulphide bond formation system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 341697-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart, P. S., F. Roe, J. Rayner, J. G. Elkins, Z. Lewandowski, U. A. Ochsner, and D. J. Hassett. 2000. Effect of catalase on hydrogen peroxide penetration into Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66836-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stickler, D. J., N. S. Morris, R. J. Mclean, and C. Fuqua. 1998. Biofilms on indwelling urethral catheters produce quorum-sensing signal molecules in situ and in vitro. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 643486-3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wayne, L. G., and G. A. Diaz. 1986. A double staining method for differentiating between two classes of mycobacterial catalase in polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels. Anal. Biochem. 15789-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whittaker, M. M., V. V. Barynin, S. V. Antonyuk, and J. W. Whittaker. 1999. The oxidized (3,3) state of manganese catalase: comparison of enzymes from Thermus thermophilus and Lactobacillus plantarum. Biochemistry 389126-9136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]