Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic lung infections are the major cause of morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. The P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and PA14 were compared with the Liverpool epidemic strain LESB58 to assess in vivo growth, infection kinetics, and bacterial persistence and localization within tissues in a rat model of chronic lung infection. The three P. aeruginosa strains demonstrated similar growth curves in vivo but differences in tissue distribution. The LESB58 strain persisted in the bronchial lumen, while the PAO1 and PA14 strains were found localized in the alveolar regions and grew as macrocolonies after day 7 postinfection. Bacterial strains were compared for swimming and twitching motility and for the production of biofilm. The P. aeruginosa LESB58 strain produced more biofilm than PAO1 and PA14. Competitive index (CI) analysis of PAO1, PA14, and LESB58 in vivo indicated CI values of 0.002, 0.0002, and 0.14 between PAO1-PA14, PAO1-LESB58, and LESB58-PA14, respectively. CI analysis comparing the in vivo growth of the PAO1 ΔPA5441 mutant and four PA14 surface attachment-defective (sad) mutants gave CI values 10 to 1,000 times lower in competitions with their respective wild-type strains PAO1 and PA14. P. aeruginosa strains studied in the rat model of chronic lung infection demonstrated similar in vivo growth but differences in virulence as shown with a competitive in vivo assay. These differences were further confirmed with biofilm and motility in vitro assays, where strain LESB58 produced more biofilm but had less capacity for motility than PAO1 and PA14.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a versatile and ubiquitous opportunistic pathogen infecting humans, animals, insects, and plants. It is considered a leading cause of nosocomial infections in hospital-acquired pneumonia, in immunocompromised individuals, and in individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF). It produces a variety of both cell-associated and extracellular virulence factors coordinately regulated by density-dependent cell-cell communication known as quorum sensing (15, 20). In addition, its motility by swimming, swarming, and twitching and its capacity of forming a biofilm are recognized as playing vital roles in the ability of the bacterium to adapt to and colonize various ecological niches, including the human lung.

Most laboratories have been using a limited number of P. aeruginosa prototype strains for various studies. The P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain is a prototype used in many laboratories for many years, and PA14 was a human isolate that is now used as a reference strain because it has a wide host spectrum for studies of virulence. LESB58 is a hypervirulent human CF isolate. The specific features for each of these three strains are summarized in Table 1. The PAO1 strain is the standard laboratory and genetic reference strain, with a completely sequenced 6.3-Mb genome containing 5,570 annotated open reading frame (ORFs) (52). A highly virulent clinical isolate, UCBPP-PA14 (PA14) was identified as a “multihost” pathogen capable of infecting animals (in a burned mouse model), plants, insects, and nematodes (34, 44). Genetic and genomic analysis of the PA14 genome (6.5 Mb) identified pathogenicity islands and an extensive degree of conservation of virulence genes, suggesting a capability of infecting various hosts. Two pathogenicity islands of 108 and 11 kb, called PAPI-1 and PAPI-2, respectively, were identified as being unique to PA14 and absent in the PAO1 genome (23). Most of the genes within these islands are homologous to known genes found in other human and plant bacterial pathogens. For example, PAPI-1 carries a complete gene cluster predicted to encode a type IV group B pilus, a well-known adhesin absent in PAO1. In PA14, 19 PAPI-1 ORFs were found to be necessary for virulence in plants or in animals; 11 ORFs are required for both (Table 1). The large set of “extra” virulence factors encoded by both pathogenicity islands may contribute to the increased promiscuity of the highly virulent PA14 strain. The genome of PA14 has been sequenced, and a draft version of the PA14 annotation is available at http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/Parabiosys/and has been deposited in GenBank (accession no. CP000438) (33).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the three P. aeruginosa strains used in this studya

| Strain | Approx genome size (Mb) | Pili | Flagella | Genetic elementsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAO1 (52) | 6.264 | Type IVa class (31) | Highly conserved b-type | GI (4 ORFs between flgL and fliC) (54) |

| PA14 (33, 44) | 6.537 | Type IVb class (11, 23) | Highly conserved b-type (54) | PAPI-1, PAPI-2 (23); GI identical to PAO1 (54) |

| LESB58 (9) | 6.599 | NDc | Highly conserved b-type (46) | PAGI-1, homologous O6 serotype, exoS and type III pyoverdine receptor, quorum sensing overexpression (40); PAGI-2 (50) |

Reference numbers are in parentheses.

GI, glycosylation island; PAGI-1 and -2, P. aeruginosa genomic islands 1 and 2; PAPI-1 and -2, P. aeruginosa pathogenicity islands 1 and 2.

ND, not determined.

A highly virulent epidemic strain (LES) was first identified in the Liverpool CF clinic center (9) and was further recognized for its epidemic nature by transfer between CF patients and from CF patients to non-CF relatives, causing significant morbidity (35). Furthermore, there is greater morbidity among CF patients colonized with the LES clone than among those carrying nonepidemic strains of P. aeruginosa (1). Compared with the PAO1 strain, the highly transmissible and aggressive LES strain displays enhanced virulence, a wider spectrum of antibiotic resistance, and presumably a better adaptation to the CF lung (46). The success of LES isolates in lung colonization may be due to the prior acquisition of genes or pathogenicity islands (40), to transcriptional variations in the level of gene expression, or to a combination of both. Such changes contribute to greater colonization and/or transmissibility of the LES strains, enhancing their ability to cause chronic infections in CF patients, and to enhanced virulence, manifesting itself in infections of non-CF parents.

The genome of P. aeruginosa displays a mosaic structure, with all strains possessing a highly conserved backbone referred to as the core genome, including recognized virulence factors (46). Variations between strains include the presence or absence of genomic islands, which can partially explain differences in virulence.

In this study, we examined the capacities of three different P. aeruginosa strains to initiate and maintain a chronic infection in the rat lung model by following in vivo growth up to 14 days. Bacteria were localized and their distribution in lung tissues determined using histological and immunofluorescence methods. We also examined bacterial motility and the capacity for the production of biofilm. The competitive indexes (CIs) between wild-type strains and several mutant strains, including PAO1ΔPA5441 and four PA14 surface attachment-defective (sad) mutants, were also determined. Previously, the PAO1Δ PA5441 mutant was identified as being attenuated in vivo by signature-tagged mutagenesis screening (42), and PA14 sad mutants have been shown to produce reduced biofilm levels (38). We used these mutants as negative controls in order to validate in vivo CI analysis and for measurement of the expression of virulence factors in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. Unless otherwise indicated, P. aeruginosa and Escherichia coli strains were grown in tryptic soy broth or Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco, BD, Sparks, MD). When needed, these media were supplemented with 1.5% Bacto agar and the following antibiotics at the indicated concentrations: gentamicin (Gm), ampicillin (Ap), kanamycin (Km), tetracycline (Tc) (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario, Canada), or carbenicillin (Cb) (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Burlington, Ontario, Canada). Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, T4 DNA polymerase, and T4 polynucleotide kinase were purchased from New England Biolabs (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and used in standard procedures (47). HotStart Taq DNA polymerase was from Qiagen (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), and PCRs were performed in an iCycler thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada).

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) or genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| ElectroMaxDH10B | Electrocompetent cells, F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80 lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK λ−rpsL nupG | Invitrogen |

| One Shot MAX Efficiency DH5α-T1R= | F− φ80 lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 tonA | Invitrogen |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAO1 | PAO1293, Cms, E79 tv-2, wild type, derivative of prototrophic PAO1 | 28 |

| PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr | PAO1293ΔPA5441::Gmr, Gmr, 934-bp replacement of PA5441 gene with Gmr cassette | This study |

| PA14 | Wild type, UCBPP-PA14, human isolate | 33,44 |

| PA14sad-160 | PA14 sadRS::Gmr, Gmr, biofilm mutant, Tn5 insertion between rocA and rocR (sadA and sadR) | 29 |

| PA14sad-168 | PA14sad-168 (PA0267)::Tn5B21, Tcr, biofilm mutant | 38 |

| PA14sad-199 | PA14sadB-199 (PAO5346)::Tn5B21, Tcr, biofilm mutant | 7 |

| PA14sad-210 | PA14sad-210 (PAO4953, motB)::Tn5B21, Tcr, biofilm mutant | 38 |

| LESB58 | CF isolate, β-lactam resistant, Gmr Azr Imr (Imipenem) | 9,50 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUCP19 | Cbr, cloning vector | 56 |

| pPS856 | Apr Gmr | 26 |

| pDONR221 | Kmr Cmr; Gateway pDONR vector with pUC origin, T7 promoter/priming site, M13 forward (−20) and reverse priming sites; rrnB T1 and T2 transcription terminators, attP1 and attP2 sites, ccdB gene | Invitrogen |

| pEX18ApGW | Apr Cmr; derived by cloning a Gateway conversion fragment into the multiple cloning site of pEX18Ap; attR1 and attR2 sites; ccdB and sacB genes; GenBank accession no. AY928469 | 13 |

Construction of mutants (i) Construction of P. aeruginosa PAO1 knockout mutant PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr.

For construction of the deletion mutant P. aeruginosa PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr, a previously described strategy was used (13). Briefly, in the first round of PCR, the Gm resistance gene cassette was amplified using the Gm-F and Gm-R primers (Table 3). The 5′ and 3′ fragments of the PA5441 gene were amplified in two PCRs. The first reaction was done with the PA5441-UpF-GWL and PA5441-UpR-Gm primers for the constructed deletion of PA5441 and the second reaction with the PA5441-DnF-Gm and PA5441-DnR-GWR primers (Table 3). In the second round of PCR, PCR mixture contained the same components as for 5′ and 3′ fragment PCR amplifications, 50 ng of each PA5441 in 5′ and 3′ purified template DNAs, and 50 ng of FRT-Gm-FRT template DNA prepared during the first-round PCR. The BP and LR clonase reactions for recombinational transfer of the PCR product into pDONR221 and pEX18ApGW, respectively, were performed as described in Invitrogen's Gateway cloning manual but with only half of the recommended amounts of BP and LR clonase mixes and E. coli One Shot Max Efficiency DH5α-T1. Transfer of the plasmid (pEX18ApGW)-borne deletion mutations to the P. aeruginosa chromosome was done by electroporation (12). A few colonies were patched on LB-Gm30 plates and LB-Cb200 plates to differentiate single- from double-crossover events. To ascertain resolution of merodiploids, Gmr colonies were struck for single colonies on LB-Gm30 plates containing 5% sucrose. Gmr colonies from the LB-Gm-sucrose plates were patched onto LB-Gm30 plus 5% sucrose, as well as LB-Cb200. Colonies growing on the LB-Gm30-sucrose plates but not on the LB-Cb plates were considered putative deletion mutants. The presence of the correct mutations was verified by colony PCR with the PA5441-UpF-GWL and PA5441-DnR-GWR primers (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this work

| Primer | Relevant sequencea |

|---|---|

| Gm-F | CGAATTAGCTTCAAAAGCGCTCTGA |

| Gm-R | CGAATTGGGGATCTTGAAGTTCCT |

| GW-attB1 | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCT |

| GW-attB2 | GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGT |

| PA5441-UpF-GWL | TACAAAAAAGCAGGCTgagaagctcgaaggctacgg |

| PA5441-UpR-Gm | TCAGAGCGCTTTTGAAGCTAATTCGgcgaccgctgtagaagttgg |

| PA5441-DnF-Gm | AGGAACTTCAAGATCCCCAATTCGgcgctgttcactctcctttac |

| PA5441-DnR-GWR | TACAAGAAAGCTGGGTatgaccaggcgatagccatc |

Sequences in uppercase letters are common for all genes to be replaced and overlap with the Gm or attB primer sequence. Lowercase letters indicate PA5441-specific sequences.

(ii) Construction of PA14 sad mutants.

From the collection of random transposon mutants of P. aeruginosa PA14 generated with the transposon Tn5-B21 or Tn5-B30 (Tcr) (38, 48), four sad mutants were used for the CI experiments in a rat lung infection model: the PA14sad-160, PA14sad-168, PA14sad-199, and PA14sad-210 mutants. A ΔsadRS::Gmr (sad-160) double-knockout mutation of the sadR (PA3947) and sadS (PA3946) genes was generated, where the sensor histidine kinases and upstream response regulators were deleted and replaced by a Gmr cassette by using allele replacement (29). The original PA14sad-168, PA14sadB-199, and PA14sad-210 mutant strains were reconstructed into the wild-type PA14 strain by phage-mediated transduction (6).

Preparation of bacteria for in vivo experiments. (i) Preparation of agarose-embedded bacteria for determination of individual kinetics and CIs.

Preparation of the individual P. aeruginosa strains or wild-type-mutant mixtures in agarose beads was modified from a previously described method (53). All P. aeruginosa strains (PAO1, PAO1 containing plasmid pUCP19, PA14, LESB58, the PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr mutant, and the PA14 mutants PA14sad-160 [with a Tn5 insertion between rocA and rocR {sadA and sadR} that overexpresses sadR/rocR], PA14sad-168 [PA0267], PA14sad-199 [sadB, PA5346], and PA14sad-210 [motB, PA4953]) listed in Table 2 were grown separately in 50 ml of brain heart infusion in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks. After overnight incubation in a shaking incubator at 37°C, the optical density at 600 nm of each culture was noted. A 200- to 500-μl aliquot of overnight cultures of single strains or equal ratios of wild-type-mutant mixtures were completed to 5 ml with fresh brain heart infusion to give a final concentration of approximately ∼1 × 108 CFU/100 μl (injection volume). At the end of the preparation, we can expect an approximate bacterial loss of 2 logs. A 250-ml flask containing a magnetic bar and 200 ml of sterile mineral oil was prepared, equilibrated at 48°C, placed on a magnetic stirrer in a water bath (setting of 800 rpm on a Hotplate Stirrer, model M13 [Staufen, Germany]). Twenty milliliters of 2% low-melting-temperature agarose (NuSieve; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, ME) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) was also prewarmed at 48°C and rapidly mixed with a 5-ml final volume of individual or mixture cultures and added to the mineral oil. The mixture was cooled gradually with ice chips to 0°C over 5 min. The agarose beads were washed once with 200 ml of 0.5% deoxycholic acid sodium salt (SDC; Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS, once with 0.25% SDC-PBS, and three times with PBS in a 500-ml Squibb-type separator funnel. The bead slurry was allowed to settle for a few minutes at 4°C, and the remaining PBS was removed. The agarose beads were then homogenized for 30 seconds with a polytron homogenizer (Kinematica, model PTA 20S; Dispergier und Mischtechnik, Littau/Luzern, Switzerland) and serially diluted. Dilutions were plated in duplicates on Pseudomonas isolation agar (PIA) for single strains and on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA)-Cb200 for wild-type PAO1/pUCP19 selection, MHA-Gm50 for PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr and PA14sad-160 mutant strain selection, and MHA-Tc50 for PA14sad-36, PA14sad-168, PA14sad-199, and PA14sad-210 mutant strain selection.

(ii) Agar bead preparation for CI experiments with PAO1, PA14, and LESB58.

Agar beads were prepared according to a modification of a previously described method (8). Each P. aeruginosa strain, i.e., PAO1, PA14, and LESB58, cultured separately overnight, was regrown to an optical density at 600 nm of 1, and 5 × 109 bacteria were sedimented by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, resuspended in 1 ml PBS (pH 7.4), and added to 9 ml of 1.5% Trypticase soy agar that had been prewarmed to 50°C. The mixture (equal bacterial ratio) of each pair (PAO1-PA14, PAO1-LESB58, and LESB58-PA14) was pipetted forcefully into 150 ml heavy mineral oil (Sigma-Aldrich) at 50°C and stirred rapidly with a magnetic stirring bar for 6 min at room temperature, followed by cooling at 4°C with continuous stirring for 20 min. The oil-agar mixture was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 20 min to sediment the beads and washed six times in PBS, pH 7.4. The preparations, with beads of 100 μm to 200 μm in diameter, were used as inocula for animal experiments. The number of bacteria in the beads was determined by homogenizing the bacterium-bead suspension and plating 10-fold serial dilutions on blood agar plates. The inoculum for infection was prepared by diluting the bead suspension with PBS (pH 7.4) to 5 × 106 CFU/ml.

Rat model of chronic lung infection.

We used a rat chronic lung infection model for all in vivo experiments. Male Sprague-Dawley rats of approximately 500 g in weight were used according to the guidelines of the ethics committee for animal treatment. The animals were anesthetized using Isofluorane (2% of respiratory volume) and inoculated by intubation using an 18-gauge venous catheter and syringe (1-ml tuberculin) with 120 μl of a suspension of agarose/agar bead-embedded bacteria containing approximately 1 × 106 to 5 × 106 CFU/injection. At the indicated time intervals, the lungs were removed from sacrificed rats, and homogenized tissues were plated in triplicates on appropriate media.

(i) Infection kinetics of P. aeruginosa PAO1, PA14, and LESB58 strains in the rat lung and formaldehyde lung fixation.

Thirty-two rats were infected with 120 μl of each agarose-embedded bacterial strain, and eight rats from each group were sacrificed at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days postinfection. From these eight rats, five were sacrificed using an excessive dose of Isofluorane (Baxter) and were used for CFU counts. The three remaining rats were anesthetized using 40 mg ketamine (Bioniche)/kg of body weight and 5 mg/kg xylazine (Novopharm) and were processed for formaldehyde lung fixation. After the thorax was opened, a perfusion needle (no. 22) was used to penetrate the right ventricle of the heart toward the pulmonary artery and was fixed with hemostatic clamps. The left atrium was opened to allow fluids to escape from the system during perfusion. Using a peristaltic pump, approximately 40 ml of 1× PBS solution was administered for 2 min, and then 180 ml of 4% formaldehyde solution in PBS was used for 10 min to fix the rat lung at flow rate of 18 ml/min. The lung was removed very gently to avoid tissue damage and was fixed in the same solution of formaldehyde for at least 24 h. Finally, the lung tissue was embedded in paraffin. Longitudinal sections of 5 μm, collected at regular intervals, were obtained with a microtome from the proximal, medial, and distal lung regions. Sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) or with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) and used for immunofluorescence (see “Immunolocalization of P. aeruginosa in the rat lung” below).

(ii) In vivo CIs.

The in vivo CIs were determined for the PAO1/pUCP19-PA14, PAO1/pUCP19-LESB58, and PA14-LESB58 pairs and for the PAO1/ pUCP19-PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr, PA14-PA14sad-160, PA14-PA14sad-168, PA14- PA14sad-199, and PA14-PA14sad-210 wild-type-mutant strain pairs. Injections of approximately 120 μl of each bacterial mixture were administrated to ∼10 animals. After 7 days of infection, the bacterial counts were performed on infected rat lungs, using PIA for total bacterial number of P. aeruginosa; MHA-Cb200 for PAO1/pUCP19 wild-type strain selection; MHA-Gm15 for LESB58, PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr, or PA14sad-160 mutant selection; and MHA-Tc50 for PA14sad-168, PA14sad-199, or PA14sad-210 mutant strain selection. In preliminary experiments and to confirm that the plasmid is not cured during the in vivo passage, we determined that there were similar numbers of CFU in animals harboring the PAO1 strain with pUCP19 using MHA without and with Cb200 (data not shown). The CI is defined as the CFU output (in vivo) ratio of the mutant in comparison to wild-type strain divided by the CFU input ratio of mutant to wild-type (2, 22). The final CIs were calculated as the geometric mean for animals in the same group.

Immunolocalization of P. aeruginosa in the rat lung.

Deparaffinized sections of rat lung tissue were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence using a rabbit antiserum specific for P. aeruginosa (kindly provided by J. Pier, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). The secondary antibody was Texas Red-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Molecular Probes). The slides were examined using an Axioplan fluorescence microscope (Zeiss), and images were taken with a KS 300 imaging system (Kontron).

Phenotypic characterization of P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and PA14, clinical isolate LESB58, and PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr and PA14 sad mutants (PA14sad-160, PA14sad-168, PA14sad-199, and PA14sad-210). (i) Biofilm formation assay.

To assess the formation and quantification of biofilm, a 96-well plate rapid biofilm formation assay was performed as described previously (38).

(ii) Motility assays.

Swimming and twitching motility assays were based on a previously published method (45).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis were performed with GraphPad Prism 5 software using the Mann-Whitney t test.

RESULTS

In vivo growth of P. aeruginosa strains in the rat lung.

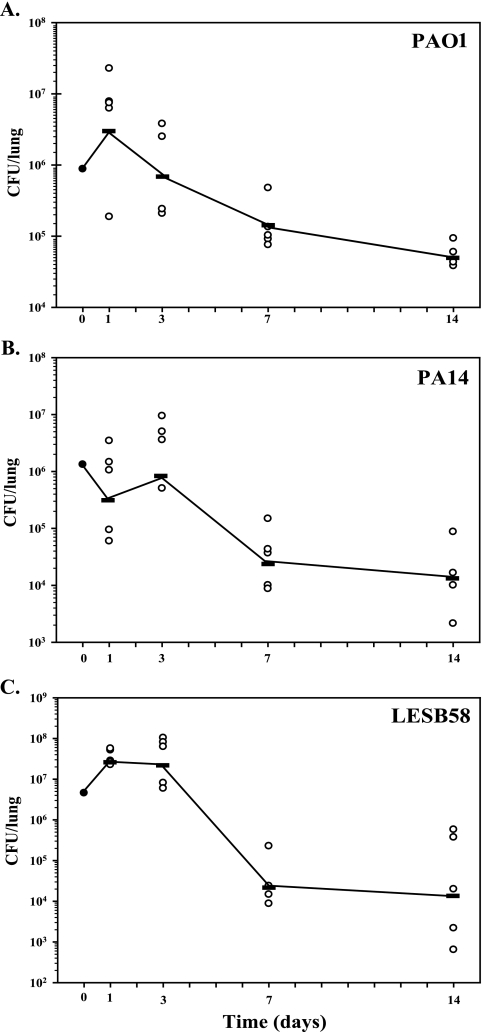

To compare the capacities of the strains to initiate and establish a chronic lung infection in vivo, bacterial growth was monitored by determining CFU from lung tissues at specific time points from day 1 up to day 14 postinfection. As depicted in Fig. 1, the overall growth curves were similar for the three strains tested, with a peak of CFU at day 1 and a reduction in CFU from day 3 to day 7. A plateau was reached at day 7, and there were fewer variations in CFU from day 7 up to day 14. For PAO1 (Fig. 1A) and LESB58 (Fig. 1C), similar numbers of CFU were obtained, where the number of bacteria increased from 1 × 106 CFU/lung at injection to 1 × 107 CFU/lung at day 1 post infection. At day 7, we noted a decrease to 8 × 104 CFU/lung. This average of CFU was maintained up to day 14. For PA14 (Fig. 1B), the peak of infection appeared at day 3 with 3 × 106 CFU/lung, and bacterial counts decreased to the same level as for the two other strains at day 14. In general, we observed significantly lower bacterial counts for PA14, except at day 3. For LESB58, CFU were higher at day 3 but lower at 7 and 14 days postinfection. These results showed that different P. aeruginosa strains were able to initiate and maintain an infection in the rat lung.

FIG. 1.

In vivo growth curves for P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 (A), PA14 (B), and LESB58 (C) in the rat model of chronic lung infection for 14 days. Rats were infected with agarose-embedded bacteria at 1 × 106 CFU for each strain. At different time points (1, 3, 7, and 14 days postinfection), five animals were used from each group and CFU were determined from infected lungs.

Localization of P. aeruginosa in the rat lung.

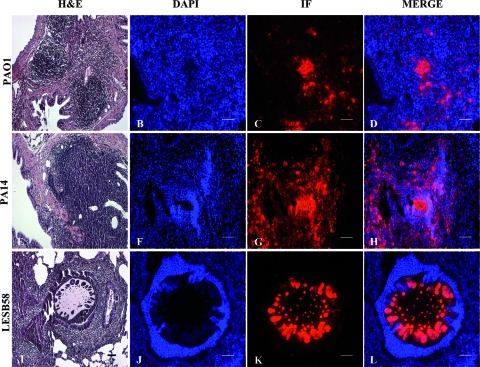

The localization of bacterial cells and the lung inflammatory response to infection were characterized from the initial challenge at day 1 up to day 14. At days 1 and 3, HE staining and indirect immunofluorescence showed that PAO1, PA14, and LESB58 bacteria were present within beads in the bronchial lumen where they were deposited and induced an intense inflammatory response (data not shown). Analysis at day 7 showed PAO1 and PA14 cells in the alveolar region, where they can form biofilm/macrocolonies with extensive inflammation in submucosa and alveoli (Fig. 2D). In contrast, LESB58 bacterial cells were still present in the bronchial lumen (Fig. 2L). Although the chronic lung infection was established using equal CFU, bacterial cells from these three strains were not found with the same localization when the chronic infection was established.

FIG. 2.

Localization and persistence of PAO1, PA14, and LESB58 in the rat lung at 7 days postinfection. Rats were infected with P. aeruginosa strains embedded in agarose beads, the lungs were fixed and investigated histologically, and bacteria were localized by indirect immunofluorescence. (A, E, and I) HE-stained rat lung histology at 7 days after infection with agarose-embedded PAO1 (A), PA14 (E), and LESB58 (I). Inflammatory cell infiltrations are evident in the thickened alveolar septa of rat lung for the PAO1 and PA14 strains, while for the lungs infected with LESB58, the recruitment of neutrophils is predominantly in the bronchial lumen, where the beads are still localized. (C, G, and K) At day 7, P. aeruginosa bacterial macrocolonies were detected by indirect immunofluorescence (IF) (red) in the thickened alveolar septa of rat lungs infected with strains PAO1 (C) and PA14 (G), while for LESB58, (K) bacterial colonies were still present in the agar beads. (B, F, and J) DAPI (blue) staining of the same tissue sections. (D, H, and L) Merge of the DAPI-stained slides (blue) and bacteria localized by IF (red). Bars, 50 μm.

In vivo competitive analysis of the PAO1, PA14, and LESB58 strains.

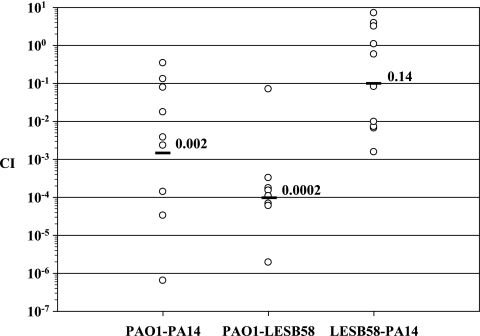

To assess the virulence of the three P. aeruginosa strains in the rat model of chronic lung infection, we decided to analyze the in vivo competitive growth between strains PAO1-PA14, PAO1-LESB58, and LESB58-PA14. Equal ratios of each strain were mixed in agar beads, the mixture was inoculated into the rat lung, and bacteria were enumerated from the lungs at day 7 postinfection. The CI was calculated, and results are shown in Fig. 3. The competitive analysis between PAO1 and PA14 showed a large variation in lung CFU between each animal and a mean CI value of 0.002. This result indicated a 1,000-fold reduction of PA14 in vivo when in competition with PAO1. A mean CI value of 0.0002 was obtained for the CI analysis between PAO1 and LESB58, suggesting a 10,000-fold attenuation of LESB58 in competition with PAO1. The CI analysis between LESB58 and PA14 gave a mean CI of 0.14, suggesting a 10-fold attenuation of PA14 by LESB58.

FIG. 3.

CI analysis of P. aeruginosa wild-type strains PAO1, PA14, and LESB58. Each circle represents the CI for a single animal in each group. A CI of less then 1 indicates a virulence defect. The geometric mean of the CIs for all rats is shown as a solid line. CIs for PAO1-PA14 and PAO1-LESB58 were significantly different (P < 0.01).

Validation of the P. aeruginosa chronic lung infection model using PAO1 and PA14 mutants. (i) Construction of the PAO1Δ PA5441::Gmr knockout mutant.

The P. aeruginosa STM5441 mutation, inactivating the PA5441 gene, which is part of the two-gene operon PA5441 and PA5442, was identified as attenuated in vivo in the 72 mutant pools by using signature-tagged mutagenesis (42). The PA5441 ORF encodes a putative outer membrane hypothetical protein of 80 kDa. A comprehensive analysis of P. aeruginosa genes encoding the enzymes of cyclic-di-GMP metabolism (diguanylate cyclase [DGC]- and phosphodiesterase [PDE]-encoding genes) was carried out to analyze the function of cyclic-di-GMP in two disease-related phenomena, cytotoxicity and biofilm formation (30). Analysis of the phenotypes of DGC and PDE mutants, including PA5442 mutants and overexpressing clones, revealed that certain virulence-associated traits such as CHO cytotoxicity and biofilm formation are controlled by multiple DGCs and PDEs through alterations in cyclic-di-GMP levels (30). Thus, the intracellular signaling molecule cyclic-di-GMP encoded by PA5442 has been shown to influence bacterial behaviors, including motility, biofilm formation, and cell toxicity. Since the PA5441-PA5442 operon is potentially important and since it had been already selected as attenuated in vivo in the previous study, we decided to use it as a control for our CI experiments in vivo.

To obtain a clean genetic background, the PAO1ΔPA5441:: Gmr deletion mutant strain was constructed (13). The 934-bp ΔPA5441 deletion was confirmed by PCR (data not shown). The P. aeruginosa knockout mutant PAO1ΔPA5441 was used for in vivo CI experiments in competition with the wild-type bacteria and was tested for swimming and twitching motility and biofilm formation.

(ii) Identification and characterization of PA14 sad mutants.

Four PA14 mutants defective in biofilm production were designated as surface attachment defective (sad mutants). Since biofilm formation is considered an important virulence factor in vivo, the PA14 sad mutants were chosen as controls with the PAO1ΔPA5441 mutant to validate in vivo and in vitro assays.

The DNA sequences flanking the Tn5 insertions in sad mutants were determined using the arbitrary PCR method, and the sequences obtained were compared to the GenBank and P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome sequence (www.pseudomonas.com) databases using BLASTX (38).

The genomic DNA flanking the sad-160::Tn5 transposon insertion indicated that the transposon is located into an intergenic region between two divergently transcribed genes (PA3947 [sadR] and PA3948 [sadA]) and adjacent to the PA3946 (sadS) regulator gene. PA3947 and PA3948 encode proteins homologous to response regulators involved in two-component regulatory systems, and the PA3946 ORF is homologous to sensor histidine kinases. Thus, this locus was referred as a three-component system. Nonpolar mutations in any of the sadARS genes resulted in biofilms with an altered mature structure but did not confer significant defects in growth or early biofilm formation, swimming, or twitching motility. This suggested that the sadARS three-component system is required for later events in biofilm formation on an abiotic surface (29).

PA14sad-168 is a strain that was reconstructed via phage-mediated transduction. The insertion in PA14sad-168 is in the PA0267 gene. This is a gene of unknown function with homology to cheY.

The transposon insertion carried by the PA14sadB-199 mutant was mapped into to PA5346, and the ORF encodes a protein of unknown function associated with the biofilm-defective phenotype. Examination of flow cell-grown biofilms showed that the PA14sadB-199 mutant could initiate surface attachment but failed to form microcolonies, despite being proficient in both twitching and swimming motility (7).

The transposon insertion carried by the PA14sad-210 mutant was mapped to the chemotaxis protein MotB homolog of P. aeruginosa. PA4953 (motB) encodes MotB, a flagellar motor protein involved in cell motility and secretion, and is expressed with motA. RpmA is one of two MotA paralogs in P. aeruginosa, and RpmA and RpmB have been shown to be required for the efficient ingestion of P. aeruginosa by macrophages (49).

(iii) Attenuation of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 mutants in vivo.

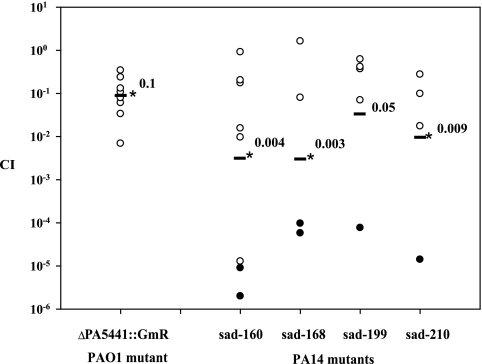

To determine the capacity of strains to cause chronic lung infection, one PAO1 mutant strain and four PA14 mutant strains were analyzed using the CI. As depicted in Fig. 4, the mutation in PA5441 caused a defect in in vivo maintenance. After 7 days postinfection, the PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr mutant had a 10-fold decrease of CFU in the rat lung in comparison with the wild-type PAO1, giving an average CI of 0.1, compared to 1.0 for the wild-type PAO1. All four PA14 sad mutants were severely attenuated after 7 days postinfection (from 10-fold down to 1,000-fold), giving average CI values of 0.004, 0.003, 0.05, and 0.009 for PA14sad-160, PA14sad-168, PA14sad-199, and PA14sad-210, respectively.

FIG. 4.

CI analysis of the P. aeruginosa PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr and PA14sad-160, PA14sad-168, PA14sad-199, and PA14sad-210 mutant strains in a rat model of lung infection. Equal ratios of each wild-type strain and their respective mutants were embedded in agarose beads, and rat lungs were infected by intubation with approximately 5 × 106 CFU/lung. After 7 days postinfection, the lungs were recovered for CFU determinations. Each circle represents the CI for a single animal in each group. A CI of less then 1 indicates a virulence defect. Black circles indicate that no mutant was recovered from the animal, and 1 was substituted in the numerator when calculating the CI. The geometric mean of the CIs for all rats is shown as a solid line. *, P values for mutants are significantly different from the wild type (P < 0.01).

Phenotypic characterization of the strains. (i) P. aeruginosa strain LESB58 demonstrates differences in biofilm formation.

Since differences in in vivo virulence and bacterial localization were identified between PAO1, PA14, and LEB58, we tested these strains for biofilm production in microtiter plates of polyvinylchloride (PVC). In this in vitro system, the PAO1 and PA14 strains produced similar biofilm levels (Fig. 5A). Even though LESB58 showed a lower growth rate in minimal medium after 6 h (data not shown), significantly greater amounts of biofilm were produced (Fig. 5A). Compared with the two other strains, the crystal violet-stained ring formed on the walls of PVC wells at the liquid-air interface was thicker for LESB58, and a kind of deposit was observed at the bottom of the well with LESB58 only.

FIG. 5.

Phenotypic characterization of P. aeruginosa strains PAO1, PA14, LESB58, PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr, PA14sad-160, PA14sad-168, PA14sad-199, and PA14sad-210. Biofilm was quantified after 6 h of growth using the microtiter dish assay (A). Significantly greater biofilm formation was observed for LESB58. All PAO1 and PA14 mutants produced significantly lower levels of biofilm (P ≤ 0.01). Swimming motility (B) and twitching motility (C) are also shown.

(ii) Reduced biofilm formation for P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 mutants.

The P. aeruginosa PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr and PA14sad-160, PA14sad-168, PA14sad-199, and PA14sad-210 mutant strains were tested for their ability to form a biofilm. The surface-attachment defective (sad) PA14 mutants were used as negative controls. The PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr mutant was also defective in biofilm formation; the crystal violet-stained ring formed on walls of PVC wells was smaller than that with the wild-type strain (data not shown). As depicted in Fig. 5A, the quantity of biofilm production indicated less biofilm biomass for the PAO1ΔPA5441::Gmr mutant. The four PA14 sad mutants were defective in biofilm production compared with the wild-type strain PA14.

(iii) Analysis of bacterial motility.

Since variations in biofilm production may be caused by changes in flagellum and type IV pilus production (38), we measured the swimming and twitching motilities of the studied strains. Swimming depends upon flagella, whereas twitching depends on type IV pili (25). As shown in Fig. 5B, differences in swimming ability were apparent for the LESB58 wild-type strain, for the ΔPA5441::Gmr deletion mutant, and for the PA14sad-210 mutant. We also assayed the type IV pilus-mediated twitching motility for all strains (Fig. 4C). Twitching motility was reduced in strain LESB58 only. No correlation between the motility phenotypes and the ability to produce biofilm was apparent in any of the strains tested.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the kinetics and growth rate in the rat lung infection model for three widely used P. aeruginosa strains, PAO1, PA14, and LESB58, using low-melting-point agarose. Although there is some evidence that bacteria can escape the agarose beads in vitro, there was no clear evidence that this occurs in vivo. The three P. aeruginosa strains studied have similar lung colonization abilities with similar in vivo growth rates in the rat model of chronic lung infection. As shown here, the bacterial release from agarose beads was similar for two prototype strains, whereas bacterial cells of LESB58 remained in agarose beads even after 14 days. Swimming and twitching motilities were reduced in LESB58 in vitro, which could explain maintenance in agar beads.

Using a rat model of chronic lung infection with bacteria embedded in agarose beads, similar infection patterns were clearly displayed for all three strains. At days 1 and 3 some differences were observed between strains. At days 7 and 14 postinfection, chronic lung infection was well established with the three P. aeruginosa strains. However, HE-stained lung tissue and indirect immunofluorescence of P. aeruginosa revealed different localization of the persisting bacterial cells (Fig. 2). The LESB58 cells were found in the bronchial lumen from the day of challenge up to 14 days of persistence, and bacterial cells were alive. Future studies will be necessary to determine if LESB58 is protected by agar beads or simply cannot migrate because of reduced mobility. In contrast, PAO1 and PA14 cells were initially deposited in the bronchial lumen, but after 7 days the bacterial cells were localized in the alveolar region, where they grew as macrocolonies. It is likely that the persisting bacterial cells were protected from the respiratory defense system by alginate, extracellular polysaccharides, and possibly by the beads (5, 41).

Several phenotypes, such as biofilm formation, have been associated with chronic P. aeruginosa pulmonary infections in CF (14). Standard laboratory strains such as PAO1 and PA14, although originally clinical isolates (27, 44), have reduced biofilm formation compared with more recent clinical isolates such as LESB58 (Fig. 5A). This is perhaps related to attenuation of these two strains after decades of passages in vitro. These findings suggest that PAO1 may be equipped with endogenous biofilm suppression mechanisms, because they are not necessary in laboratory conditions, or, conversely, that the more recently isolated LESB58 possesses mechanisms to promote biofilm formation. We showed that LESB58 produced increased amounts of biofilm despite slower bacterial growth in minimal medium, which is in agreement with studies demonstrating that the specific planktonic growth rates of CF isolates were significantly lower than those of non-CF strains (46). Association into a biofilm offers the advantage of allowing the bacterial community to operate as a unit protected from the external environment and increases resistance to antibiotics and host defenses (18). Bacterial cells in a biofilm may cooperate metabolically and evolve as a community by horizontal gene transfer (21). Furthermore, the CF isolates may constantly adapt themselves to changes in the CF lung environment over the course of chronic colonization. Yu and Head (57) demonstrated that strains isolated sequentially from the same patient over a period of 4 years expressed different levels of biofilm formation.

The role of flagella and type IV pili in biofilm formation and in attachment to host cells has been extensively studied (31, 43). In the present study, LESB58 showed reduced swimming and twitching motility and significantly increased capacity for biofilm formation compared with PAO1 and PA14. The PA14sad-210 mutant had reduced swimming motility and reduced biofilm formation capacity. It was demonstrated that the flagellar activity of some CF isolates is not the predominant factor relating to the progressive development of biofilms in vitro (24). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that twitching mediated by type IV pili was not found in all CF strains. However, several of these strains produced more biofilm than PAO1, reminiscent of strain LESB58. Our results agree with these observations and suggest the presence of another adhesion mechanism in CF isolates. The lack of correlation between the activities of flagella and type IV pili and the amount of biofilm produced has been explained by the qualitative role of these structural appendages as biofilm adhesins. In addition, the increased initial biofilm formation was linked with isogenic variants deficient in flagellum and type IV pilus activities (10, 17). Also, an additional surface structure called curli has been implicated in increased biofilm formation in an E. coli K-12 mutant but has not yet been identified in P. aeruginosa (55). Recently, it has been shown that swarming is a more complex type of motility, since it is influenced by a large number of different genes in P. aeruginosa. Conversely, many of the swarming-negative mutants also showed impairment in biofilm formation, indicating a strong relationship between these types of growth states (39).

Some of the differences between P. aeruginosa strains PAO1, PA14, and LESB58 are summarized in Table 1. Some CF isolates of P. aeruginosa were found to often display a high frequency of mutation after long-term colonization in CF (37), possibly due to single-nucleotide polymorphisms. One example of CF-related single-nucleotide polymorphisms involved mutations in mucA, giving rise to overproduction of alginate (3, 4). Also, it is known that PAO1 carries transposons and a bacteriophage (52). The large set of supplementary virulence functions encoded by pathogenicity islands may contribute to the increased promiscuity of highly virulent P. aeruginosa strains. The genomic island PAGI-1 was shown to be present in 85% of strains originating from clinical sources (9, 40, 50). Multiresistant Liverpool CF epidemic strains were also found to carry a genomic island associated with pathogenic strains (PAGI-1) (40). This strain was also found to be serotype O6 and to carry the exoS gene, was not hypermutable, and contained a type III pyoverdine receptor, in contrast to type I and type II pyoverdine producers (16). In addition, two P. aeruginosa pathogenicity islands (PAPI-1 and PAPI-2) were identified in the genome of PA14, a highly virulent clinical isolate (23). The 108-kb PAPI-1 and the 11-kb PAPI-2, which are absent from the reference strain PAO1, exhibit highly modular structures.

Analysis of 20 P. aeruginosa strains by using the PAO1 DNA microarray revealed a conserved pattern of a core genome assembled as a mosaic in many strains. Even if the subsets of 38 gene islands were absent or divergent, no specific pattern was associated with strains isolated from the airways of CF patients (19).

Additional evidence of horizontal gene transfer is the increase in genome size. It was shown that many CF isolates had genomes much larger than the typical 6.3 Mb for PAO1 (24). The genome sizes of some CF isolates ranged from 0.4 to 18.9% larger than that of PAO1 (24). However, it has been shown recently that although extensive novel sequences are present in the genomes of CF isolates, the backbone of the PAO1 genome is still preserved (32, 51).

The in vivo CFU and infection kinetics data presented here suggest that all three strains remain excellent for studying virulence, even though their genome size varies and is not strictly representative of most CF isolates. There is evidence that bacteria in biofilms have an increased incidence of horizontal gene transfer, analogous to the situation observed in hypervirulent LES (46). CI analysis has revealed interesting features of PAO1, PA14, and LESB58. Much research on CF has focused on how chronic infection affects the patient because inflammation from infecting bacteria causes persistent respiratory symptoms and an inexorable decline in lung function. However, the onset of chronic infection is also transformative for the bacteria, because an environmental P. aeruginosa strain (which may have been living in, for example, a water pipe) must adjust to the alien conditions of the lung and live long-term within the host (36). Hope for developing new treatments rests in part on understanding how bacteria adapt to the airway and resist host defenses and antibiotics. This report extends information on the in vivo behavior of the three P. aeruginosa strains PAO1, PA14, and LESB58 and on their phenotypic variability in biofilm formation. P. aeruginosa LESB58 has unique features for in vivo maintenance, which merits further investigation and could give insight into P. aeruginosa virulence in CF lung disease.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to D. Woods from the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, for his assistance with and comments on using the rat model of chronic lung infection; to R. De La Durantaye from Laval University, Québec, Canada, for excellent technical assistance with animal manipulations; and to R. Janvier and S. Roy from Laval University, Québec, Canada, for assistance in preparation of microscopic samples and skillful advice.

R. C. Levesque is funded by the Canadian Institute for Health Research as part of the CIHR Genomics Program as a Research Scholar of Exceptional Merit, and I. Kukavica-Ibrulj obtained a studentship from Le Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ). G. A. O'Toole is supported by research grant NIH HL074175.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Aloul, M., J. Crawley, C. Winstanley, C. A. Hart, M. J. Ledson, and M. J. Walshaw. 2004. Increased morbidity associated with chronic infection by an epidemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain in CF patients. Thorax 59334-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beuzon, C. R., and D. W. Holden. 2001. Use of mixed infections with Salmonella strains to study virulence genes and their interactions in vivo. Microbes Infect. 31345-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher, J. C., H. Yu, M. H. Mudd, and V. Deretic. 1997. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: characterization of muc mutations in clinical isolates and analysis of clearance in a mouse model of respiratory infection. Infect. Immun. 653838-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bragonzi, A., L. Wiehlmann, J. Klockgether, N. Cramer, D. Worlitzsch, G. Doring, and B. Tummler. 2006. Sequence diversity of the mucABD locus in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. Microbiology 1523261-3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bragonzi, A., D. Worlitzsch, G. B. Pier, P. Timpert, M. Ulrich, M. Hentzer, J. B. Andersen, M. Givskov, M. Conese, and G. Doring. 2005. Nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa expresses alginate in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis and in a mouse model. J. Infect. Dis. 192410-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budzik, J. M., W. A. Rosche, A. Rietsch, and G. A. O'Toole. 2004. Isolation and characterization of a generalized transducing phage for Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains PAO1 and PA14. J. Bacteriol. 1863270-3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caiazza, N. C., and G. A. O'Toole. 2004. SadB is required for the transition from reversible to irreversible attachment during biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 1864476-4485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cash, H. A., D. E. Woods, B. McCullough, W. G. Johanson, Jr., and J. A. Bass. 1979. A rat model of chronic respiratory infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 119453-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng, K., R. L. Smyth, J. R. Govan, C. Doherty, C. Winstanley, N. Denning, D. P. Heaf, H. van Saene, and C. A. Hart. 1996. Spread of beta-lactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a cystic fibrosis clinic. Lancet 348639-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiang, P., and L. L. Burrows. 2003. Biofilm formation by hyperpiliated mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1852374-2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi, J. Y., C. D. Sifri, B. C. Goumnerov, L. G. Rahme, F. M. Ausubel, and S. B. Calderwood. 2002. Identification of virulence genes in a pathogenic strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by representational difference analysis. J. Bacteriol. 184952-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi, K. H., A. Kumar, and H. P. Schweizer. 2006. A 10-min method for preparation of highly electrocompetent Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells: application for DNA fragment transfer between chromosomes and plasmid transformation. J. Microbiol. Methods 64391-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi, K. H., and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. An improved method for rapid generation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa deletion mutants. BMC Microbiol. 530-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costerton, J. W., P. S. Stewart, and E. P. Greenberg. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 2841318-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Kievit, T. R., Y. Kakai, J. K. Register, E. C. Pesci, and B. H. Iglewski. 2002. Role of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa las and rhl quorum-sensing systems in rhlI regulation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 212101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Vos, D., M. De Chial, C. Cochez, S. Jansen, B. Tummler, J. M. Meyer, and P. Cornelis. 2001. Study of pyoverdine type and production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients: prevalence of type II pyoverdine isolates and accumulation of pyoverdine-negative mutations. Arch. Microbiol. 175384-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deziel, E., Y. Comeau, and R. Villemur. 2001. Initiation of biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 57RP correlates with emergence of hyperpiliated and highly adherent phenotypic variants deficient in swimming, swarming, and twitching motilities. J. Bacteriol. 1831195-1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drenkard, E., and F. M. Ausubel. 2002. Pseudomonas biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to phenotypic variation. Nature 416740-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst, R. K., D. A. D'Argenio, J. K. Ichikawa, M. G. Bangera, S. Selgrade, J. L. Burns, P. Hiatt, K. McCoy, M. Brittnacher, A. Kas, D. H. Spencer, M. V. Olson, B. W. Ramsey, S. Lory, and S. I. Miller. 2003. Genome mosaicism is conserved but not unique in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the airways of young children with cystic fibrosis. Environ. Microbiol. 51341-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuqua, C., M. R. Parsek, and E. P. Greenberg. 2001. Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35439-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghigo, J. M. 2001. Natural conjugative plasmids induce bacterial biofilm development. Nature 412442-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hava, D. L., and A. Camilli. 2002. Large-scale identification of serotype 4 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors. Mol. Microbiol. 451389-1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He, J., R. L. Baldini, E. Deziel, M. Saucier, Q. Zhang, N. T. Liberati, D. Lee, J. Urbach, H. M. Goodman, and L. G. Rahme. 2004. The broad host range pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 carries two pathogenicity islands harboring plant and animal virulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1012530-2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Head, N. E., and H. Yu. 2004. Cross-sectional analysis of clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: biofilm formation, virulence, and genome diversity. Infect. Immun. 72133-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henrichsen, J. 1972. Bacterial surface translocation: a survey and a classification. Bacteriol. Rev. 36478-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 21277-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holloway, B. W. 1955. Genetic recombination in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Gen. Microbiol. 13572-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holloway, B. W., V. Krishnapillai, and A. F. Morgan. 1979. Chromosomal genetics of Pseudomonas. Microbiol. Rev. 4373-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuchma, S. L., J. P. Connolly, and G. A. O'Toole. 2005. A three-component regulatory system regulates biofilm maturation and type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1871441-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulasakara, H., V. Lee, A. Brencic, N. Liberati, J. Urbach, S. Miyata, D. G. Lee, A. N. Neely, M. Hyodo, Y. Hayakawa, F. M. Ausubel, and S. Lory. 2006. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases reveals a role for bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-GMP in virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1032839-2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kus, J. V., E. Tullis, D. G. Cvitkovitch, and L. L. Burrows. 2004. Significant differences in type IV pilin allele distribution among Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis (CF) versus non-CF patients. Microbiology 1501315-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larbig, K., C. Kiewitz, and B. Tummler. 2002. Pathogenicity islands and PAI-like structures in Pseudomonas species. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 264201-211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, D. G., J. M. Urbach, G. Wu, N. T. Liberati, R. L. Feinbaum, S. Miyata, L. T. Diggins, J. He, M. Saucier, E. Deziel, L. Friedman, L. Li, G. Grills, K. Montgomery, R. Kucherlapati, L. G. Rahme, and F. M. Ausubel. 2006. Genomic analysis reveals that Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence is combinatorial. Genome Biol. 7R90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahajan-Miklos, S., L. G. Rahme, and F. M. Ausubel. 2000. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence using non-mammalian hosts. Mol. Microbiol. 37981-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCallum, S. J., M. J. Gallagher, J. E. Corkill, C. A. Hart, M. J. Ledson, and M. J. Walshaw. 2002. Spread of an epidemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain from a patient with cystic fibrosis (CF) to non-CF relatives. Thorax 57559-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen, D., and P. K. Singh. 2006. Evolving stealth: genetic adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during cystic fibrosis infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1038305-8306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliver, A., R. Canton, P. Campo, F. Baquero, and J. Blazquez. 2000. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 2881251-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 30295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Overhage, J., S. Lewenza, A. K. Marr, and R. E. Hancock. 2007. Identification of genes involved in swarming motility using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 mini-Tn5-lux mutant library. J. Bacteriol. 1892164-2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parsons, Y. N., S. Panagea, C. H. Smart, M. J. Walshaw, C. A. Hart, and C. Winstanley. 2002. Use of subtractive hybridization to identify a diagnostic probe for a cystic fibrosis epidemic strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 404607-4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pier, G. B., D. Boyer, M. Preston, F. T. Coleman, N. Llosa, S. Mueschenborn-Koglin, C. Theilacker, H. Goldenberg, J. Uchin, G. P. Priebe, M. Grout, M. Posner, and L. Cavacini. 2004. Human monoclonal antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate that protect against infection by both mucoid and nonmucoid strains. J. Immunol. 1735671-5678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Potvin, E., D. E. Lehoux, I. Kukavica-Ibrulj, K. L. Richard, F. Sanschagrin, G. W. Lau, and R. C. Levesque. 2003. In vivo functional genomics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for high-throughput screening of new virulence factors and antibacterial targets. Environ. Microbiol. 51294-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pratt, L. A., and R. Kolter. 1999. Genetic analyses of bacterial biofilm formation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2598-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahme, L. G., E. J. Stevens, S. F. Wolfort, J. Shao, R. G. Tompkins, and F. M. Ausubel. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 2681899-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rashid, M. H., and A. Kornberg. 2000. Inorganic polyphosphate is needed for swimming, swarming, and twitching motilities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 974885-4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salunkhe, P., C. H. Smart, J. A. Morgan, S. Panagea, M. J. Walshaw, C. A. Hart, R. Geffers, B. Tummler, and C. Winstanley. 2005. A cystic fibrosis epidemic strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa displays enhanced virulence and antimicrobial resistance. J. Bacteriol. 1874908-4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 48.Simon, R., J. Quandt, and W. Klipp. 1989. New derivatives of transposon Tn5 suitable for mobilization of replicons, generation of operon fusions and induction of genes in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 80161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simpson, D. A., and D. P. Speert. 2000. RpmA is required for nonopsonic phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 682493-2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smart, C. H., M. J. Walshaw, C. A. Hart, and C. Winstanley. 2006. Use of suppression subtractive hybridization to examine the accessory genome of the Liverpool cystic fibrosis epidemic strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Med. Microbiol. 55677-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spencer, D. H., A. Kas, E. E. Smith, C. K. Raymond, E. H. Sims, M. Hastings, J. L. Burns, R. Kaul, and M. V. Olson. 2003. Whole-genome sequence variation among multiple isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1851316-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, I. T. Paulsen, J. Reizer, M. H. Saier, R. E. Hancock, S. Lory, and M. V. Olson. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Heeckeren, A. M., and M. D. Schluchter. 2002. Murine models of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection. Lab. Anim. 36291-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verma, A., M. Schirm, S. K. Arora, P. Thibault, S. M. Logan, and R. Ramphal. 2006. Glycosylation of b-type flagellin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: structural and genetic basis. J. Bacteriol. 1884395-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vidal, O., R. Longin, C. Prigent-Combaret, C. Dorel, M. Hooreman, and P. Lejeune. 1998. Isolation of an Escherichia coli K-12 mutant strain able to form biofilms on inert surfaces: involvement of a new ompR allele that increases curli expression. J. Bacteriol. 1802442-2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.West, S. E., H. P. Schweizer, C. Dall, A. K. Sample, and L. J. Runyen-Janecky. 1994. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 14881-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu, H., and N. E. Head. 2002. Persistent infections and immunity in cystic fibrosis. Front. Biosci. 7d442-d457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]